Abstract

The problem:

Over 187 definitions of rehabilitation exist, none widely agreed or used. Why?

The word:

Words represent a core concept, with a penumbra of associated meanings. A word means what is agreed among those who use it. The precise meaning will vary between different groups. Words evolve, the meaning changing with use. Other words may capture some of the concepts or meanings.

A definition:

A definition is used to control the unstable, nebulous meaning of a word. It delineates, creating a boundary. A non-binary spectrum of meaning is transformed into binary categories: rehabilitation, or not rehabilitation. In clinical terms, it is a diagnostic test to identify rehabilitation. There are many different reasons for categorising something as rehabilitation. Each will need its own definition.

Categorisation:

The ability of a definition to distinguish cases accurately must be validated by comparison with ‘the truth’. If there were an external ‘true’ test to identify rehabilitation, a definition would not be needed. As with most concepts, the only truth is agreement by people familiar with the required distinction. Any definition will generate misclassification. People familiar with the required distinction will also need to resolve mis-categorisation.

Description:

An alternative is a ‘descriptive definition’, listing features over several domains which must be present. This fails logically. Rehabilitation is an emergent concept, more than the sum of its parts.

Conclusion:

A useful definition cannot be achieved because no definition will cover all needs, and a specific definition for a purpose will misclassify some cases.

Keywords: Rehabilitation, definition, description

Introduction

A recent study found 187 definitions of rehabilitation, 1 which suggests rehabilitation may be difficult to define. In contrast, most people agree on what is rehabilitation. So, why is definition difficult? Does the failure to agree a definition suggest that we should stop trying to define rehabilitation?

This editorial explores the difficulty in defining rehabilitation. It was stimulated by the recent project by the Cochrane Rehabilitation group, who wrote: ‘Cochrane Rehabilitation found difficulties in defining inclusion and exclusion criteria for interventions in rehabilitation. This project aims to develop a new definition of rehabilitation to be used for these scientific purposes’. 2

This editorial considers the problem from three perspectives: linguistic, clinical and philosophical. The three different analyses lead to the same conclusion: we can describe rehabilitation, but we cannot define it in a way that is useful. An overview of the exploration is given in Supplemental Figure 1.

Definitions and words

The Oxford English Dictionary considers a definition to be ‘an exact statement or description of the nature, scope, or meaning of something’. This describes how the word is used. The nature of a definition is rather more subtle.

Definition is derived from the Latin verb, definire, which means ‘to set bounds to’ and this is a much more accurate explication of its meaning. Defining an object or concept involves drawing a boundary around it, such that there is an apparently clear distinction between what is included, and what is not.

A word is described as ‘a single distinct conceptual unit of language, comprising inflected and variant forms’ [OED]. The inflected and variant forms cover, for example, rehabilitate, rehabilitation and rehabilitative.

The meaning (conceptual unit) carried by a word is fluid. As Plato recognised, any concept encapsulated by a word has an ‘essential nature’. However, a single word can apply to a great variety of actual objects. For example, anything from a log to a throne might be correctly called a chair when used as ‘something to sit on’ at a table. The dictionary describes the use of a word, usually also recapitulating its evolution. Dictionaries do not define.

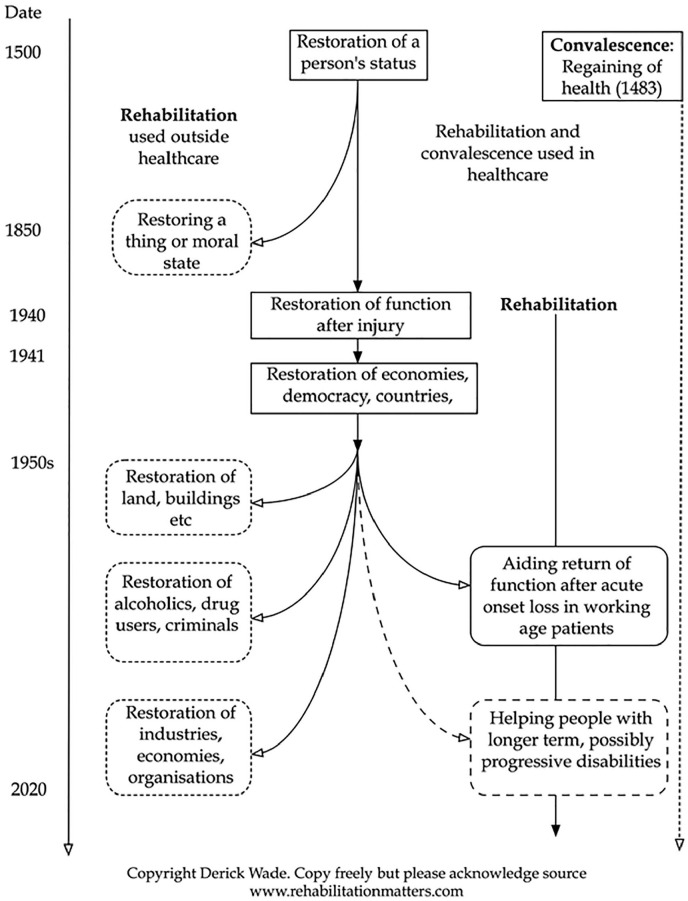

Rehabilitation now has many meanings, some shown in Supplemental Figure 2. For its first 440 years, the meaning scarcely changed; it referred to restoring the social status of a person who had lost social status, usually through some misdemeanour. It acquired a new meaning in 1940, when it was used in a report on helping war-wounded soldiers back to work. Within a few years the word, rehabilitation, was being used in relation to cities, economies, land, prisoners and countries.

The evolution of the concept of rehabilitation is shown in Figure 1. The figure also shows the long-neglected word, convalescence, which refers to ‘time spent recovering from an illness or medical treatment; recuperation’ [OED]. This term predated rehabilitation and covers the same phase of an illness, albeit as a passive process. Indeed, rehabilitation should encompass convalescence as an important process within rehabilitation. 3

Figure 1.

Development of meaning of rehabilitation.

The Oxford English dictionary considers rehabilitation to mean ‘the action of restoring someone to health or normal life through training and therapy after imprisonment, addiction, or illness’. All its uses referring to objects or to processes also incorporate the idea of restoration. Interestingly, given the current emphasis on function in rehabilitation, the Latin root is habilitare, to be made able.

The word, rehabilitation, has incorporated many concepts within its boundaries. Two reviews of its current meaning have been carried out, one focused on its meaning as used commonly 1 and one focused on the definitions used by experts. 4 Both reviews identified similar core concepts within the meaning of rehabilitation:

it is a process, which encompasses many actions as a bundle;

- it is also a strategy, with overall specific aims;

- its aims relate to optimising function, social integration, autonomy and quality of life

it is person-centred

Interestingly, the words ‘restore’, ‘improve’ and ‘reduce’ were all quite low in the hierarchy of meanings.

As the meanings associated with the word, rehabilitation, have expanded from simple restoration of social status to include, within health, the process and the goals of rehabilitation, so a number of other words have encroached upon the central core of its meaning. Words such as enablement, reablement, intermediate care, resettlement and restorative care have all been used to represent concepts that are indistinguishable from rehabilitation (see Supplemental Figure 2).

Words evolve. Their meaning changes, or sometimes takes on an additional meaning. Words may also take on different meanings in different contexts (cultures, countries, languages, organisation, etc.). Indeed, new or different meaning may separate out in groups of people, separated by geography, language, profession etc., forming new meaning ‘sub-species’. At the same time, other words may encroach upon some aspects, or all aspects of the essential nature of a word. In evolutionary terms, other words move into an area when opportunities arise.

The problem

This natural development and evolution of language poses a challenge to any person, process or organisation that wants strong control over some activity centred on the meaning of a word. Developing a definition is one way to impose order and stability upon this fluid, unpredictable situation.

In clinical work, the changing and fluid meaning of words is managed naturally. Speakers will add explanation, and listeners will seek clarification. People working closely together will usually share the meaning closely; when working with people from another context, more clarification may be needed. In the clinical context, discussions, not definitions, establish what is meant.

Research requires more consistency. The Cochrane group wished to identify which of the 9471 published Cochrane Systematic Reviews (in 2017) were ‘about rehabilitation’. 5 Twenty-five volunteers (12 physicians, 12 physiotherapists and 1 occupational therapist) from 13 countries looked through the reviews, and each review was classified twice.5,6 There were disagreements about classification in 894 of the 9471 cases. In 28 there were simple mistakes, leaving 866 where classification was not agreed.

Using an agreed set of criteria, which changed during the review process, 6 a committee decided that 90 (of 866) were not about rehabilitation. These disagreements were attributed to conflicts in the rationale (reasoning), whereby some studies on a specific treatment were classified as being about rehabilitation while other studies on the same intervention were classified as not being about rehabilitation. The committee resolved the disagreement by imposing consistency for an intervention.

In the remaining 776 which were finally classified as being about rehabilitation, there were 54 instances where the committee disagreed with the two clinical reviewers. 5

This led the Cochrane group to investigate the consistency between three different methods for deciding if a review was about rehabilitation:

clinical judgement, by a clinician

the criteria used in the first study, 6

the use of the National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Heading (MESH) term, Rehabilitation, used to index studies in PubMed.

Using PubMed to find reviews with ‘rehabilitation’ in the title, 89 Cochrane systematic reviews were identified. 7 Of this 89, 5 were excluded using the criteria developed earlier 6 ; 4 were excluded by clinicians reading the reviews; but, using the MESH term, Rehabilitation, 44 were excluded. Obviously, the MESH index was not indexing as being about rehabilitation about half of the studies considered clinically and by the criteria used 6 to be studies of rehabilitation.

The problem encountered by the Cochrane group arises in many other guises in many other contexts. For example, decisions need to be made about whether something involves rehabilitation when:

allocating funds for research into rehabilitation;

being asked to pay for rehabilitation for an individual patient, or for a specific rehabilitation treatment;

when identifying studies to help develop evidence-based rehabilitation guidelines;

funding services providing rehabilitation;

selecting patients for admission to a rehabilitation service;

deciding whether a paper is suitable for a rehabilitation journal.

Each group needing to decide wants a definition to help them. A cynic would suggest that a definition reduces the need to think and removes the need to take responsibility for and to justify decisions. Others would argue that definitions lead to consistency and fairness.

Can definitions help?

Definitions delineate something for a specific purpose. As a corollary, a definition needs to be constructed to achieve the specific purpose, be it deciding on funding a service, or a patient’s rehabilitation, or a rehabilitation intervention. In other words, each context will have a different requirement of a definition, and so each group wanting a definition will need a different definition, one tailored to their purpose.

The reason for the definition – what is it trying to achieve – must be considered carefully. Often the purpose is too vague and imprecise to warrant a definition. Assuming that a clear purpose is identified, then the next step is to determine whether the definition achieves its purpose. This is sometimes referred to as identifying ‘the gold standard’ against which a definition is measured. Alternatively, one can ask, ‘is this definition valid?’

In almost all the examples given above, there is no way to validate a definition externally. This should not be a surprise, for if there were a way, a definition would not be needed.

The definition as a diagnostic test

A definition being used for a purpose is a diagnostic test, categorising someone or something. Assuming that a definition is developed, and a means of determining validity is agreed, then it is necessary to determine how accurate the definition is in achieving its purpose. In other words, a definition is simply an example of a prognostic or diagnostic test. It is taking a non-binary phenomenon, the meaning of a word and converting it into a binary classification. It is inevitable that there will be misclassifications.

Thus, any definition should be tested for its purpose and, if found valid, it should only be used for that purpose. Moreover, it should only be used on similar populations, because the rate of misclassification itself depends upon the proportion of the tested population who would be one class. A definition developed for one purpose in one population should not be used for some other purpose or in some other population with different characteristics.

Given that misclassification will occur, a system for handling misclassified examples will be needed. The system used, such as the committee used by the Cochrane group, will involve people using their judgement. The inevitable need for this fall-back rather defeats the point of developing a definition!

Attempts to develop a general-purpose definition are likely to develop an ever-increasing list of characteristics. A further problem will then emerge, analogous to Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle (the more accurately the speed of an object is known, the less accurately its position is known). The more closely one aspect of rehabilitation is characterised, the more difficult it will be to describe all possibilities for the other characteristics.

Philosophy and logic

Descriptions of rehabilitation giving features of different aspects of rehabilitation, such as a description involving the patient population, the structures, the processes and the intended outcomes (the goals), 8 might be used as a definition. Indeed, although published as a description, it has been classified as a definition. 4

This approach is an example of the mereological fallacy.9,10 This fallacy is often referred to when discussing the definition or nature of consciousness. 9 The fallacy is summarised thus: ‘ascribing to a part of a creature attributes which logically can be ascribed only to the creature as a whole’. One book explains it thus. 10 If you hit your thumb with a hammer, it is painful. But where do you feel that pain? In the thumb? In your periaqueductal grey matter? Elsewhere in your brain? The answer is ‘none of these’; you feel the pain as a person.

Defining rehabilitation by breaking it down into a finite, usually small number of parts is to miss the point. The concept of rehabilitation is an emergent property associated with its processes. Emergent properties are common, such as subjective experience which is probably an emergent property of an information-processing brain. 11 Just as with consciousness, defining rehabilitation by reference to its structures or processes cannot succeed, because there is more to the meaning than its structures and processes.

Conclusions

Attempting to define rehabilitation ‘for scientific purposes’, or indeed for any purpose, will fail for three reasons.

Linguistic

The word, rehabilitation, encapsulates a concept that slowly moves and changes over time. The concept will differ between different groups of people, separated geographically, or by language, or by profession, or by other factors. Finding a common meaning that will be accepted and used by all people in the same way is simply not possible. Even if a meaning could be agreed, the agreed meaning would immediately start to disintegrate.

Clinical

A definition that draws boundaries around a nebulous (and ever changing) concept will suffers all the problems of any method of categorising a non-binary spectrum into binary categories. Additionally, definitions will vary according to purpose, will always make incorrect categorisations, and cannot be validated. Judgement will always be required, to resolve difficult cases.

Logical

A definition that simply lists a series of criteria, or features will fail to capture the actual essence of rehabilitation, which is an emergent phenomenon; it is more than the sum of simple structures and processes.

The solution to the problems faced is not to develop a better definition. It is, first, to consider and set out in detail exactly what is wanted, and why. Once this has been fully explored, then a system should be devised, based on evidence where available, to allow classification for the specific purpose. The system must have built-in mechanisms using the judgement of a person, or a group of people, in difficult or high-stakes cases. It would be a better use of resources to solve the problem directly, rather than looking for a definition to do it.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-cre-10.1177_02692155211028018 for Defining rehabilitation: An exploration of why it is attempted, and why it will always fail by Derick T Wade in Clinical Rehabilitation

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-2-cre-10.1177_02692155211028018 for Defining rehabilitation: An exploration of why it is attempted, and why it will always fail by Derick T Wade in Clinical Rehabilitation

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: I am an advisor to the Cochrane Rehabilitation group.

Funding: The author received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Derick T Wade https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1188-8442

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Arienti C, Patrini M, Pollock A, et al. A comparison and synthesis of rehabilitation definitions used by consumers (Google), major Stakeholders (survey) and researchers (Cochrane Systematic Reviews): a terminological analysis. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2020; 56(5): 682–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cochrane Rehabilitation. Special projects, https://rehabilitation.cochrane.org/special-projects (accessed 18 June 2021).

- 3. Wade DT, Halligan PW. Social roles and long-term illness: is it time to rehabilitate convalescence? Clin Rehabil 2007; 21: 291–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Meyer T, Kiekens C, Selb M, Posthumus E, Negrini S. Toward a new definition of rehabilitation for research purposes: a comparative analysis of current definitions. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2020; 56(5): 672–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Levack WM, Rathore FA, Negrini S. Expert opinions leave space for uncertainty when defining rehabilitation interventions: analysis of difficult decisions regarding categorization of rehabilitation reviews in the Cochrane library. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2020: 56(5): 661–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Levack WMM, Rathore FA, Pollet J, et al. One in 11 Cochrane reviews are on rehabilitation interventions, according to pragmatic inclusion criteria developed by Cochrane rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2019; 100(8): 1492–1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Negrini S, Arienti C, Küçükdeveci A, et al. Current rehabilitation definitions do not allow correct classification of Cochrane systematic reviews: an overview of Cochrane reviews. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2020; 56(5): 667–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wade DT. What is rehabilitation? An empirical investigation leading to an evidence-based description. Clin Rehabil 2020; 34(5): 571–583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Glock H-J. Minds, brains, and capacities: situated cognition and neo-aristotelianism. Front Psychol 2020; 11: 566385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bennett M, Hacker PMS. Philosophical foundations of neuroscience. Oxford: Blackwell, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fesce R. Subjectivity as an emergent property of information processing by neuronal networks. Front Neurosci 2020; 14: 548071. DOI: 10.3389/fnins.2020.548071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-cre-10.1177_02692155211028018 for Defining rehabilitation: An exploration of why it is attempted, and why it will always fail by Derick T Wade in Clinical Rehabilitation

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-2-cre-10.1177_02692155211028018 for Defining rehabilitation: An exploration of why it is attempted, and why it will always fail by Derick T Wade in Clinical Rehabilitation