Abstract

Understanding of the importance of addressing trauma in health care is increasing rapidly. Health care providers may be actively seeking ways to address trauma sequelae affecting their patients with a trauma-informed continuum of care. Such a continuum includes a universal approach, targeted interventions (ie, practices and programs), and specialist treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), as well as responses to historic and intergenerational trauma. Client presentations and their needs are highly individualized. Therefore, an understanding of prominent theories of what causes PTSD may assist perinatal care professionals in adapting their practice to be trauma-informed and trauma-specific. The purpose of this article is to review 4 theories of PTSD relevant to perinatal practice and present an evidence-based practice framework that encourages collaborative choices consistent with client values and preferences. A brief summary of current evidence-based PTSD treatment guidelines is presented.

Keywords: trauma, posttraumatic stress disorder, perinatal mental health, antiracism and race equity, midwifery professional issues, trauma-informed care

INTRODUCTION

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is considered to be prolonged reactivity after trauma, an exposure to an event that was a threat to life or physical integrity.1 Responses that were adaptive during a traumatic event or series of events can become maladaptive when maintained in a context of safety. Perinatal care providers often observe PTSD symptoms in response to a trigger. Triggers are sensory, emotional, or relational occurrences that cause intrusive re-experiencing of the past trauma as memory, flashback, or nightmare. The physical or psychological reactions that are a response to triggers can be intense, as though the trauma were happening again in the present. A large body of PTSD research has demonstrated that reminders of trauma activate the amygdala and stimulate or trigger the person to respond with fear, activating the fight-or-flight response with faster respiration and heart rate, elevated blood pressure, and shifting blood flow from visceral to skeletal muscles. Common triggers in perinatal care include unwelcome touch or body positioning, feelings of fear or dread, dynamics of vulnerability, being disrespected, and not being in control. A diagnosis of PTSD includes intrusion symptoms, avoidance symptoms, negative alterations in cognitions and mood, and alterations in arousal and reactivity.1 Likely because of these symptoms and other latent effects of trauma, individuals who experience PTSD during pregnancy are at risk for poorer perinatal outcomes including low birth weight, antenatal depression, hormonal dysregulation, lower rates of breastfeeding, and poorer early parenting competence, as well as adolescent pregnancy and substance use during pregnancy.2–4

Rates and types of trauma exposure vary across settings.5 PTSD is the most prominent sequela of trauma, although depression and anxiety often are comorbid conditions.6 Complex PTSD, or the dissociative subtype in which out-of-body experiences or feeling that things are unreal or not really happening are evident,1 can be present when PTSD is related to severe, prolonged, or childhood trauma.7 Rates of PTSD among pregnant individuals range from approximately 4%, which is the rate in the general female population, to 14% to 30% in some low-resource, urban settings in which the population is predominantly Black.5,8 The dissociative subtype is less common, affecting 14% of individuals with a PTSD diagnosis.9,10 Trauma exposures especially salient to the perinatal period include childhood maltreatment or adverse childhood experiences, previous traumatic birth or loss, prior medical or sexual trauma, and likely also discriminatory or inequitable care. Addressing the unique needs of survivors of trauma in perinatal settings is key to preventing or mitigating PTSD responses.

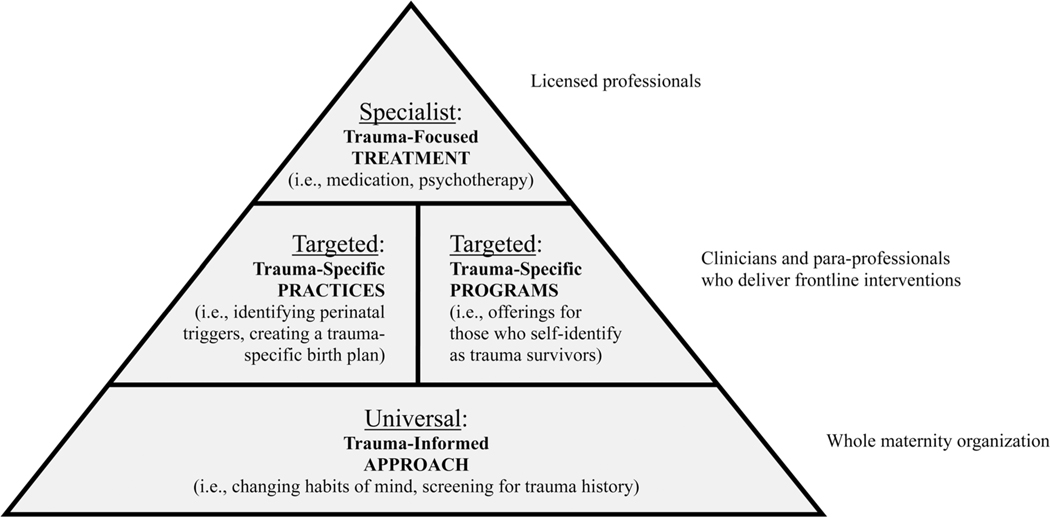

A trauma-informed approach is recommended for all providers of health care. Table 1 summarizes the National Center for Trauma-Informed Care’s framework and guiding principles.11 This approach is built into a system of care that has a 3-tier continuum that includes (1) universal trauma-informed care offered to all clients, (2) trauma-specific interventions which are targeted practices and programs, and (3) trauma-focused treatment provided by specialists (Figure 1). The third tier, specialist treatment, has received the greatest amount of attention and research, largely in the field of psychiatry. Perinatal care providers can use referrals for third-tier treatments, such as psychotherapy or medication. The first and second tiers require a combination of system-level support and individual action that is within the scope of practice of perinatal care providers.

Table 1.

National Center for Trauma-Informed Care Framework

| 3 E’3 | 4 R’s | 4 P’s |

|---|---|---|

| Trauma is defined by 3 elements: Event: the actual or extreme threat of physical or psychological harm (eg, natural disasters, violence) severe, life-threatening neglect for a child that imperils healthy development Experience: how the individual labels, assigns meaning to, and is disrupted physically and psychologically by an event contributes to whether or not it is experienced as traumatic Effect: difficulty coping with the normal stresses of daily life; trusting and benefiting from relationships; managing cognitive processes such as memory, attention, and thinking; regulating behavior; or controlling emotions |

A program or system that is trauma-informed: Realizes the widespread impact of trauma and understands potential paths for recovery Recognizes the signs and symptoms of trauma in clients, families, staff, and others involved with the system Responds by fully integrating knowledge about trauma into policies, procedures, and practices Seeks to actively resist re-traumatization. |

Six key principles of a trauma-informed approach: 1. Safety 2. Trustworthiness and transparency 3. Peer support 4. Collaboration and mutuality 5. Empowerment, voice, and choice 6. Attention to cultural, historic, andgender issues |

Source: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.11

Figure 1. A 3-Tiered System for Trauma-Informed Care in Perinatal Settings.

Source: Adapted from trauma-informed continuum of care from World Health Organization.43

The symptoms of PTSD that a client can experience and the presentations a clinician can observe vary widely. The metaphor of observing an elephant from different perspectives is apt in relation to PTSD. An elephant can appear to be a rope (tail), hose (trunk), wall (side), or tree (leg), depending on standpoint and comprehensiveness of perspective. Although many triggers have been described in qualitative studies and can be anticipated,12 others may be nearly unique to the individual. Inquiring about triggers and mutually collaborating to avoid triggers or therapeutically cope with reactions are trauma-specific practices.

Given the wide variety of presentations and the array of potential triggers, there is no algorithm or single best practice to use with clients who experience PTSD reactions. Therefore, theory can inform practice when a high level of individualization is needed. Before perinatal care providers can take effective individual action to address trauma, a solid understanding of PTSD is needed. The goal of this article is to provide information midwives can use to strengthen their second-tier practices and to summarize current third-tier interventions that have an evidence base. Four prominent theories of PTSD that are especially salient to the perinatal period are summarized, and current treatment guidelines for PTSD published by the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies13 and the International Society for Studies of Trauma and Dissociation14 are reviewed.

FOUR THEORIES OF POSTTRAUMATIC STRESS

Posttraumatic stress manifests in a variety of presentations. From the affected person’s perspective, symptoms can be obvious or subtle. From a caregiver’s perspective, it is possible to observe some reactions to triggers and some coping strategies clients use. But the range and variations can be puzzling. Using theories of what causes PTSD as lenses to look through can provide coherence to the diverse manifestations that one may observe. Being able to make coherent sense of the triggers, reactions to triggers, and coping behaviors can lead to ideas of how the midwife can respond therapeutically. There are numerous theories to explain what causes PTSD. The following 4 theories have been chosen for their salience to childbearing and health care situations. They are (1) Janet’s and Porges’ evolutionary biology theories, (2) failure of extinction of the fear response, (3) betrayal trauma, and (4) posttraumatic dysregulation.

Theory 1: Action System for Danger Versus Action System for Daily Life

Pierre Janet, a French contemporary of Sigmund Freud, proposed understanding trauma psychopathology in relation to memory and dissociation.15 Janet’s theorizing parallels modern views of ecological and evolutionary biology and psychology. Janet described humans as social creatures with 2 action systems that are based in experience and become nearly automatic. The first is the action system for danger, which is the fight-or-flight mechanisms. This action system serves to preserve the individual when danger is recognized. The second is the action system for daily life, including play, work, exploring, sexual activity and caregiving, eating, sleeping, growing, and wound healing. This action system serves to preserve the species. Janet proposed that people exposed to danger early in life adapt to live in a dangerous environment, automatically deploying the action system for danger.

Janet’s action systems have a parallel in current understanding of the function of the hypothalamic-pituitaryadrenal (HPA) axis of the sympathetic nervous system and oxytocin functions of the parasympathetic nervous system. These biologic systems are mutually regulating.16 In adapting to a dangerous environment, the fight-or-flight reaction may become habitual or the default response, and the HPA axis may predominate. For people who have survived early or prolonged trauma, these behavioral and biological reactions may persist, even in the absence of danger, and often in response to triggers.

Another theory about PTSD based on evolutionary biology and ecology is Stephen Porges’ polyvagal theory. Polyvagal theory highlights connectedness as a biological imperative. Polyvagal theory focuses on the vagal nerves, especially the ventral (or social) vagus. When this is stimulated, we seek connection. Connection facilitates co-regulation in a double sense in that the process of connection facilitates co-regulation of both the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems and it facilitates partnership with another person who is not experiencing fight-or-flight reactions. Thus, both parts of the autonomic nervous system are affected: the sympathetic via the HPA and modulation of catecholamine release and the parasympathetic via release of oxytocin. In practical terms, people seek opportunities to co-regulate when stressed or triggered. The autonomic nervous system responds to soothing others and being soothed, talking and listening, offering and receiving help, and connection with others that can affect our well-being.17

The polyvagal theory is similar to the tend and befriend work of Taylor and colleagues.18 They focused on stress more broadly, as a normal condition, rather than on PTSD as a pathological form of stress. Taylor noted the tendency of females in particular, human or other species, to seek out others in the same social group when under stress. They studied the oxytocin system response and subsequent affiliation and support-seeking as a means to reduce stress. Polyvagal theory expands this view to consider trauma and focuses on connection to others as a survival and recovery imperative, with implications for healing from trauma.19

Janet’s action systems that respond to danger and daily life and Porges’ polyvagal theory can be applied in perinatal care. Anxiety about impending birth and parenthood can trigger fight-or-flight readiness and alter function in the HPA axis and catecholamine levels. Connection and co-regulation could be considered a therapeutic response for this reaction, harnessing the antistress properties of the oxytocin system. Examples include helping grow the client’s options for social support such as using doula services for prenatal, labor, or postpartum support, using the midwife’s own voice and presence to tend and calm, and teaching co-regulation to the client in relation to their infant.

Theory 2: Failure of Extinction of the Fear Response

People with PTSD can be reminded of trauma and re-experience it, thereby inducing a fear response, even if the person is in a context of safety.20 Fear and activation of the HPA axis continue to occur because the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex, which usually supply contextual information to counter fear when there is no actual danger, do not respond in the usual way. Neuroimaging studies show that the person’s response to a trauma-specific trigger is undermodulated if they have PTSD.21 For those who react to triggers with the severe self-anesthetizing PTSD reaction of dissociation, there is evidence of an overmodulated response akin to a freeze-or-faint reaction.

The theory of PTSD as failure of extinction of the fear response has provided the foundation for some evidence-based treatments for PTSD. All the current psychotherapies that have strong evidence of effectiveness are cognitive therapies. These therapies aim to decrease the impact of triggers, the reminders of trauma that evoke PTSD reactions, by focusing on trauma memories in a variety of different ways. All these therapies have the goal of transforming the memory from automatically provoking intense re-experiencing and hyper- or hypoarousal reactions20 to diminishing the provocation and permitting the person to engage cognitive processes to manage the trigger.

The theory explaining how therapies work used to be that repeated exposure to the trauma memory or trigger decreased distress through habituation, which would decrease the strength of PTSD reactions and symptoms.22 Current research suggests that therapeutic exposure works instead through inhibitory learning.23 That is, the person learns they can tolerate being triggered, which diminishes the old responses to reminders of the trauma such as fear or avoidance.

Failure of extinction of the fear response could be an apt theoretical lens for midwives to understand expressed fears about birth and parenting and for understanding intense fight-or-flight or freeze-or-faint reactions.22 It would be theoretically sound to listen and acknowledge fear and encourage talking about any links with past trauma. Inhibitory learning theory suggests that when a person notices they are tolerating the fear reaction, that fear response is likely to diminish, especially if the intense reaction is expressed. Narrative theories suggest there may be additional benefit if the single focus on the fear reaction is enriched by making room in the person’s memory and understanding for additional feelings and responses that likely also were part of the experience but were overshadowed by the fear response.24

Theory 3: Betrayal Trauma

Childhood maltreatment is the prepregnancy trauma exposure that conveys one of the greatest risks for having PTSD during pregnancy.5 Childhood maltreatment is an interpersonal or relational trauma. Although obstetric emergencies are associated with PTSD following childbirth, the relational trauma of experiencing the labor care as incompetent or uncaring is also a prominent risk factor for childbirth-related PTSD.25,26

In 1992, Judith Herman compellingly explained how family members could do particularly complex harm via abuse or neglect of a child in their care.7 This was both because of the child’s vulnerability due to early developmental stage and because abuse or neglect is an injury to an attachment relationship that is vital to the child’s survival. In 1994 Jennifer Freyd added to this understanding, focusing on child abuse and neglect as betrayal trauma.27,28 More recently the concept of betrayal within a vital relationship has been expanded to include betrayal between institutions and those who depend upon those institutions.29 Examples include military sexual trauma and sexual misconduct in the workplace, as well as rape on college campuses. The concept of betrayal trauma can be applied to health care settings as well, including betrayal that occurs secondary to the systemic racism, othering, discrimination, and marginalization that those who are Black, Indigenous, or people of color (BIPOC) often experience in health care settings that reflect a white culture.30,31 Betrayals can take many forms, including lack of access, lack of acceptable services, not meeting expectations, and breaking promises. Betrayals may be compounded to the extent that they mirror betrayals that have occurred across generations.

When betrayal happens, reactions can include anger, loss of trust and increasing hypervigilance, ending the relationship, emotional numbing, dissociation, enduring, and/or avoidance. The subsequent weakening of provider-client and institution-client relationships are an immediate outcome. Additionally damaged is the long-term well-being that could be expected if a trusting, safe, satisfying relationship were in place at both health care provider and organizational levels.

Betrayals need not be related to individual behavior. Hospital practices or routines that address health care provider needs that are in conflict with client-expressed desires or soft refusals are forms of betrayal as well. The response to institutional betrayal is institutional courage.32 Institutional courage is described by Boulware et al as “an institution’s commitment to seek the truth and engage in moral action, despite unpleasantness, risk, and short-term cost. It is a pledge to protect and care for those who depend on the institution.”31 An example of institutional courage could include examining patterns of missed appointments and doing root cause analysis with clients who are not attending health care visits to understand their reasons, then working to address those reasons.

Theory 4: Posttraumatic Dysregulation: Allostatic Overload, Weathering, and Developmental Origins of Health and Disease

Another set of PTSD theories focus on dysregulation of one’s bio-psycho-social-spiritual self as the link between being exposed to a trauma and experiencing lasting, pervasive distress and impairments. Conceptually, the notions of homeostasis and allostasis can be helpful. In the face of normal stressors, the body responds and then recovers, returning via homeostasis to the usual physiology. In the face of traumatic or severe chronic stressors, however, an allostatic process occurs, revising the set points so the person can adapt physiologic function to live in the more demanding environment. For example, baseline adrenaline levels shift upward to facilitate fight or flight. This results in the hyperarousal symptoms of PTSD, including a hair-trigger for anger. The notion of this being visible as a type A personality with a link to heart disease is a common cultural trope. A more trauma-informed conceptualization would be to label this perception of type A personality as a person with hyperarousal symptoms of PTSD. This is an example of shifting from asking “What’s wrong with this person?” to a trauma-informed approach that asks, “What happened to this person?” The trauma-informed lens allows us to see hyperarousal reactions as body-based rather than purely behavioral and to understand these behaviors. The trauma-informed lens also helps health care providers change their behavior. For example, it makes the provider aware that saying “Just relax” is unlikely to be helpful. Instead, the provider could say, “What would help you feel safe?”

Weathering33 is another theory, similar to allostatic load but applied most often in relation to disparities in health status, disease, and early mortality experienced by those who are BIPOC. Weathering describes the gradual, inevitable, and premature aging that involves shortened telomeres and wearing down of physiologic systems that are the result of pervasive exposure to racism in all its forms. Writings on weathering put the emphasis on the body’s cost of allostatic overload when fight and flight are not feasible reactions.

The theory known as developmental origins of health and disease takes a similar but intergenerational view of physiologic adaptation. This theory notes that a fetus adapts to live in the in-utero environment that is affected by maternal physiologic responses that are, in turn, the result of the woman’s environment and exposures during pregnancy. High maternal stress during gestation results in overriding some placental protective mechanisms, such as the placental enzyme 11-β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 that usually would block excess cortisol,34 resulting in development optimized for survival in challenging circumstances. However, the cost is high because these adaptations can result in physiology that is prone to early onset of chronic pain, morbidity, and mortality. Weathering and allostatic load may also play an additional role in health disparities seen in parents and offspring who are BIPOC.

Although much of the dysregulation literature focuses on the sympathetic nervous system response to stress, in particular the HPA axis and effects associated with elevated cortisol levels,35 the parasympathetic system may be dysregulated as well. Oxytocin, for example, normally downregulates the cortisol response.36 Oxytocin may promote a tend-and-befriend affiliative stress recovery and improve cardiac recovery when caregiving is activated.37 Posttraumatic oxytocin dysregulation may also be associated with pain that is secondary to dysregulated smooth muscle peristalsis, such as occurs in persons with irritable bowel syndrome, pelvic pain, and painful bladder.38

An overarching theory known as cascade theory39 posits that childhood maltreatment leads to a cascade of adaptations in the function of oxytocin, catecholamines, and the HPA axis that can be permanent and maladaptive in the adult survivor. For people who have had chronic childhood trauma and chronic PTSD, awareness of these symptoms and reactions may be vague, and they may be unable to find words or names for their inner experience. They may have low body awareness or interoception of dysregulated physiology.40 But they may be aware that constant hyperarousal is noxious.

SHARED INTERPROFESSIONAL DIAGNOSTIC AND TREATMENT FRAMEWORKS

Although the 4 theories described in this article can help make sense of how and why PTSD symptoms and reactions manifest, none is fully aligned with the current diagnostic framework.1 The symptom clusters in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition, provide the common language for categorizing PTSD and related disorders. In addition to exposure to a traumatic event and clinically significant distress and impairment, to meet diagnostic criteria for PTSD, a person needs to have 6 out of 20 symptoms that occur in the same period and last longer than one month. The symptoms must be distributed across each of 4 symptom clusters, including at least one intrusive re-experiencing symptom, one avoidance symptom, 2 alterations in cognition or mood, and 2 alterations in arousal. Intrusive re-experiencing symptoms are the hallmark of PTSD; these include flashbacks, nightmares, and unwanted memories of the trauma that bring psychological and physical reactions as though the trauma were happening again in the present. Avoidance includes avoiding thoughts, emotions, locations, or any actions that trigger memories and the reactions that go with them. Alternations in cognition and mood include manifestations such as self-blame, guilt, and depressed mood or hopelessness related to the past trauma. Alterations in arousal include hypervigilance for danger, anger and irritability, trouble concentrating and sleeping, and an exaggerated startle reflex. These symptoms tend to reinforce each other, and the condition becomes chronic, persisting or recurring in nearly half of people meeting the diagnosis.6

PTSD often co-occurs with additional conditions, most frequently including major depressive disorder. People with posttraumatic stress may self-medicate to reduce hyperarousal and its many discomforts. Smoking, drinking, substance use, overeating, overexercising, unsafe sexual activity, and overwork can be attempts to self-regulate and reduce symptoms of PTSD.41,42 These maladaptive behavioral strategies can have adverse physical as well as biological, psychospiritual, and social effects. Naming behaviors that induce risk to health as coping strategies and responding with supports for more adaptive, healthy ways to reduce the noxious effects of PTSD and its comorbidities could be a helpful practice. Referrals that are trauma-informed or trauma-sensitive and support behavior change may also be an excellent trauma-informed practice (eg, smoking cessation, nutrition counseling, yoga classes). Referral to evidence-based psychotherapy could help resolve PTSD. Prescribing or referring for psychopharmacologic agents used to treat PTSD could reduce the symptom burden as well.43 The evidence base for effective treatments for PTSD continues to evolve and expand, with new treatment guidelines produced in 2020 by the leading PTSD specialist organizations.13,14

THE TRAUMA-INFORMED CONTINUUM OF CARE

At its most basic, trauma-informed care involves altering habits of mind to take into account that many people in the population have been exposed to traumatic events, experienced them as traumatizing, and continue to experience negative effects long after the event (Table 1, 3 E’s). In health care settings, trauma-informed care also involves understanding that there are long-term effects of trauma on mental and physical health that have been taboo to talk about and so have gone unrecognized and untreated.41 These include changes in arousal and reactivity, dissociative reactions, re-experiencing, changes in affect, avoidance of idiosyncratic triggers,1 and even alterations in attachments and trust in health care providers.38 To practice trauma-informed care, clinicians must realize the importance of trauma, recognize the signs, respond to them therapeutically, and resist retraumatizing (Table 1, 4 R’s). Organizations that use a trauma-informed approach change over time to work with 6 key principles to guide their overall culture (Table 1, 6 P’s).11 Trauma-informed health care services are structured in parallel to the World Health Organization’s tiered system of public health services, which is divided into universal, targeted, and specialist categories.44 The 3 tiers of trauma-informed care (Figure 1) can also be described as a continuum of care (Figure 2) because no single tier will suffice for each affected individual, and the 3 tiers must articulate smoothly with each other.

Figure 2. The Trauma-Informed Continuum of Care.

Abbreviation: ACEs, adverse childhood experiences.

Source: Adapted from trauma-informed continuum of care from World Health Organization.43

Trauma-informed care is a broad term describing a general approach. Each arena of health care must conceptualize, develop, evaluate, and disseminate effective practices, programs, and systems. All clients likely benefit from universal trauma-informed care. Fewer clients, those who identify as survivors of trauma, may benefit most from trauma-specific programs and practices. Still fewer, those with diagnosed mental health conditions that significantly impair or distress them, may benefit most from trauma-focused treatments. Having a wide continuum of therapeutic practices based on how affected a client is by trauma is key to the success of a trauma-informed approach.

The 3 Tiers of Trauma-Informed Care

The first tier, a universal trauma-informed approach requires all staff to change habits of mind and routines to account for the significant proportion of clients who have a history of trauma that may affect their health status and their experience of health care services. The second tier involves trauma-specific targeted programs and practices that are provided when a client self-identifies as having a history of trauma. The third tier, specialist mental health treatment, includes psychotherapy or medication treatment that addresses needs based on diagnosis. This third tier is considered trauma-focused because most of the evidence-based treatments for PTSD involve narrating detailed sensory and emotional memories of the traumatic experience. This allows reduction of intrusive re-experiencing, physiologic reactivity, and behavioral avoidance and reframing of negative cognitions or established beliefs about the trauma such as shame or guilt.13

First Tier: Universal Trauma-Informed Approach

There is little research on the effectiveness of a universal trauma-informed approach in perinatal care. Nonetheless, perinatal care clients warrant a trauma-informed approach because of the high prevalence of traumatic experiences, their relevance to pregnancy, birth, and parenting, and risk behaviors associated with trauma and childbearing. Furthermore, subclinical posttraumatic stress has been associated with distress, impairment, and treatment seeking at levels similar to those seen in persons with fully diagnosable PTSD.1,12,45–47 Thus, even without a diagnosis, a trauma-informed approach facilitates care that addresses major perinatal concerns. Although universal trauma-informed approaches do not yet have a strong evidence base, this approach likely benefits all clients by opening conversations that can be tailored to the full scope of their particular needs.

Second Tier: Trauma-Specific Programs and Practices

The second or targeted intervention tier is divided into 2 types of interventions: practices and programs (Figure 1). These interventions can often best be provided by midwives and perinatal health care providers. Practices are therapeutic responses a clinician offers to a client that are tailored to an identified or expressed need. They are unique to each client or client-provider dyad (eg, a trauma-sensitive birth plan) and are strongly influenced by the midwife’s view of the situation. An example would be asking a client who had a positive result on the primary care PTSD screen48 what triggers they might have so the midwife can make efforts to avoid triggering PTSD reactions.

Programs are evidence-based resources the perinatal care team offers to clients who disclose a history of trauma and who have unmet needs. Examples of trauma-specific programs are offering doulas who have trauma training, trauma-specific birth planning meetings, labor rehearsals, or psychoeducation programs about PTSD during childbearing and early parenting.42,49,50 Several more formal programs have been developed, which can be offered to individuals or groups (eg, Seeking Safety, Survivor Moms’ Companion).42,51 To date, these programs have been the subject of pilot studies, evaluation, and implementation reports but have not been fully evaluated for effectiveness.52,53 Trauma-specific programs can be implemented at the practice, hospital, or community level. Trauma-specific programs can enact the principles of peer support; empowerment, voice, and choice; and attention to cultural and historic trauma via creating or adapting existing programs to address justice and health together (Table 1). These programs can also build capacity and empower clients to engage fruitfully to get their needs met if referral to specialist treatment is needed or wanted for trauma-focused treatment.

Third Tier: Trauma-Focused Treatments

Most trauma research to date has evaluated trauma-focused psychotherapy or pharmacologic treatment. Thus, there is more evidence for effectiveness of these therapies than there is for effectiveness of universal trauma-informed approaches or trauma-specific practices. Table 2 summarizes evidence-based psychological treatments for PTSD. There are 2 major professional associations in the specialized field of trauma psychology, the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies and the International Society for the Study of Trauma and Dissociation. Both recently have produced psychotherapy and medication treatment guidelines.13,14 The main evidence-based treatments are nonpharmacologic and delivered by a psychotherapist (Table 2). Other complementary and adjunct interventions are used primarily to enhance the efficacy of treatments that have a strong evidence base.

Table 2. A Summary of Evidence-Based Psychological Treatments for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder.

| Treatment | Underlying Theory | Treatment Process | Evidence Base |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing | Guided by the adaptive information processing model and works with images, thoughts, emotions, sensations, and behaviors that are related to the traumatic memories. Used with a broad range of trauma exposures and has adaptations for use by persons with complex PTSD. | Uses a manualized 8-phase approach: client history, preparation, assessment, desensitization, installation, body scan, closure, and reevaluation. Desensitization involves bilateral stimulation (eye movements, tapping or auditory tones) until the memory becomes less vividly distressing. | More than 30 RCTs have demonstrated its efficacy, resulting in a strong recommendation from both ISTSS and ISSTD. EMDR is effective for survivors of complex childhood trauma in addition to more isolated traumatic events. |

| Prolonged exposure | Based in emotional processing theory and focuses on modifying the cognitive-memory structures surrounding negative emotions (ie, fear, horror, anger, guilt, shame) associated with traumatic stimuli. By activating the structures associated with the traumatic stimuli, the brain can form new conclusions about them. | Client retells the story of the trauma or is exposed to places, situations, or things that are associated with the trauma that may trigger a posttraumatic stress reaction. Psychoeducation and relaxed breathing are common components of prolonged exposure to help reprocess the traumatic stimuli, leading to desensitization. | A meta-analysis supports the efficacy of prolonged exposure. ISSTD endorses prolonged exposure with a strong recommendation. More research is needed to evaluate effectiveness in survivors of complex childhood trauma. |

| Cognitive processing therapy | Based on the theories of fear extinction and cognitive processing. After trauma, individuals may maladaptively accommodate their experiences and reactions into existing schemas. The goals are to develop realistic appraisals about the trauma and adapt schema to account for traumatic information. | Client and therapist collaborate to identify maladaptive thoughts and beliefs through dialogue and then modify them. This helps clients correct negative beliefs. | 20 RCTs supporting efficacy resulting in a strong recommendation from ISTSS and ISSTD. Cognitive processing therapy can be used effectively to target complex PTSD symptoms. |

| Cognitive therapy | Based on the cognitive model of PTSD and aims to update the distressing meanings taken from traumatic experiences, so that they become less threatening to one’s sense of self and perception of the world. | Reduce re-experiencing by discussing the trauma memories and learning to discriminate triggers. Modify negative meanings given to the trauma. Modify behaviors and adaptive psychological strategies that maintain feelings of threat. | Several prospective cohort and empirical studies support efficacy, resulting in a strong recommendation from both ISTSS and ISSTD. Study samples included a wide range of populations and trauma types. |

Abbreviations: EMDR, eye movement desensitization and reprocessing; ISSTD, International Society for the Study of Trauma and Dissociation; ISTSS, International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Psychological Treatments with Strong Evidence of Effectiveness

There are currently 4 psychological treatments with strong evidence of effectiveness that have been recommended by the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies: (1) eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR), (2) prolonged exposure, (3) cognitive processing therapy, and (4) cognitive therapy.13 Prolonged exposure, cognitive processing therapy, and cognitive therapy are all forms of cognitive behavioral therapy that has a trauma focus, whereas EMDR is a category on its own. All 4 are broadly used to aid persons from diverse populations who have many types of trauma exposures.

Psychological Treatments with Emerging Evidence of Effectiveness

Evidence that narrative exposure therapy is effective in treating PTSD is accumulating, which may be of particular interest to some midwives because it is possible for the therapist role to be filled by someone other than a licensed psychotherapist. Narrative exposure therapy is a short-term therapy that has an underlying goal of creating a coherent narrative of traumatic events and the help an individual has received, integrating sensory, physiologic, emotional, and cognitive experiences of the trauma. Narrative exposure therapy was originally designed for persons in humanitarian crisis settings. To practice narrative exposure therapy, counselors must simply be able to read and write, be compassionate, and undergo training in use of narrative exposure therapy.54 For this reason, narrative exposure therapy has potential to be provided by community health workers to compensate for the shortage of psychotherapists and lack of access to psychotherapists that is particularly acute for those who are BIPOC. This therapy also meets the key principle ideal of peer support. During narrative exposure therapy, clients construct a lifeline, which is a chronologic narrative of their life story, that has a focus on the traumatic experiences, with the goal of transforming fragmented reports of the traumatic experiences into a coherent narrative.

There are several other interventions that have emerging evidence of effectiveness, including present-centered therapy,55 sensorimotor psychotherapy,56 experiential approaches, and mindfulness approaches. Experiential approaches are used to confront dissociative alienation from one’s past experiences that have resulted in generalized depression, anxiety, shame, low self-esteem, loneliness, troubled relationships, or other sequelae. Experiential approaches use a parts perspective, interpreting emotional distress as communications from one or another of the person’s younger or traumatized parts of themselves.14 Mindfulness approaches are also being integrated into psychotherapy more frequently. Mindfulness involves “an openhearted, moment-to-moment, nonjudgmental awareness.”57(p.24) Current mindfulness approaches vary in their level of formality but generally aim to cultivate compassionate, present moment awareness.13,14

Modular and Personalized Interventions

Individualizing interventions is a proposed way to improve outcomes of PTSD treatment. Personalized interventions consider at least 3 factors: the individual, that person’s specific problems, and the circumstances in which the individual is treated. The most common way to personalize a PTSD intervention is to tailor the therapeutic techniques to a particular culture or subgroup of a population. For example, if a perinatal care organization implements a program for survivors of trauma, it could be tailored to attention to the triggers and particularities that are most likely to be stimulated by the process of pregnancy, labor, birth, and postpartum.

Another way to personalize treatments is to use a flexible modular approach.58 With a modular approach, recipients can collaborate to plan a combination of modules that are most relevant to them and the symptoms they experience. This can occur via sequencing choices, such as using psychoeducation before exposure therapy. Some treatments focus more on certain PTSD symptoms than others; for example, narrative therapies focus on memory and meaning making, whereas exposure therapies focus on hyperarousal reactions. Modular approaches can also occur via use of adjunctive methods, such as combining medication or yoga with psychotherapy.

Pharmacologic Treatments

Most effective psychotherapies involve trauma processing, which can temporarily increase symptoms. Thus, medication that reduces PTSD symptoms can be a very useful second-line or adjunctive treatment during psychotherapy.13,14 Medication choice is primarily based on PTSD diagnosis. Certified nurse-midwives and certified midwives who prescribe selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRIs) to treat depression and anxiety can also use them to treat PTSD. Midwives may wish to consult a psychiatrist or other health care provider who is accustomed to treating PTSD to help determine the best medication and plan to assess effectiveness.

Three SSRIs, fluoxetine (Prozac), paroxetine (Paxil), and sertraline (Zoloft), and one SNRI, venlafaxine (Effexor), are all recommended by International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies as medications that have a small but clinically significant effect on PTSD symptoms.13 Despite potential risks to the fetus or breastfeeding infant (eg, differential weight gain in woman and/or fetus, premature birth, some risk of birth defects) these medications may be used during pregnancy and breastfeeding in circumstances where the benefits outweigh the risks.59,60 A recent review of medications used to treat PTSD for persons who are pregnant recommends sertraline (Zoloft) because of its superior pregnancy and breastfeeding safety profile.43 Discontinuing medications because of pregnancy or failing to treat PTSD during pregnancy is not recommended because of the noxious effects of PTSD symptoms on both women and infants.5 In addition, PTSD symptoms are often more severe during the childbearing year than other stages of life because there may be many more triggers present.

Complementary Treatments and Adjunct Interventions

PTSD can be challenging to treat and so complex that a treatment done one time is unlikely to cure longstanding symptoms. Thus, complementary and adjunct modalities are often used alongside or instead of psychotherapies.13,14 These therapies have widely varying mechanisms and there are many types of complementary therapies, yet there is no universal system to classify them. The most prominent complementary and adjunct interventions used to treat PTSD include acutherapies such as acupuncture, acupressure, or electroacupuncture; tapping or emotional freedom techniques; energy-based approaches including energy psychology, disturbed bioenergy patterns, or chi/ki/prana; music interventions such as group music therapy and rapid eye movement desensitization; technology-assisted interventions such as neurofeedback and transcranial magnetic stimulation; physical therapies including yoga and exercise; cognitive interventions such as attentional bias modification, mantra repetition, and psychoeducation; and dietary supplementation such as saikokeishikankyoto.13,14 Other alternative or emerging interventions include hypnotherapy, relaxation training, nature adventure therapy, animal-assisted interventions, psychodynamic psychotherapy, and somatic experiencing.

In most cases, these interventions have not been sufficiently tested for efficacy enough to support their independent use as first-line treatments of PTSD. However, these interventions may still aid a person during the journey of posttraumatic recovery.13,14 Complementary modalities are often most helpful in mitigating complex and longstanding symptoms of PTSD when they are combined to form multicomponent or modular treatment programs, especially when used alongside psychologic or pharmacologic treatment for PTSD.13,14

DISCUSSION

Understanding theories of posttraumatic stress can help clinicians identify persons with PTSD and respond appropriately. Approaches to mitigating the noxious effects of PTSD fall within a 3-tiered continuum: (1) a universal trauma-informed approach, (2) trauma-specific programs and practices, and (3) trauma-focused treatments. Theories provide a useful basis for responding to clients’ trauma-related needs across all 3 tiers of intervention.

One key consideration when responding to unmet trauma-related needs in childbearing clients is where they are in their process of trauma recovery.45 Those who are far along on their recovery journey and have talked about their past with others may need their midwife to be an ally in avoiding triggers and may be able to advocate for their particular needs. Those who also have ongoing abuse or substance use problems may need survival-level needs met ahead of anything else. The 6 principles of a trauma-informed approach (Table 1) can guide the process of prioritizing and planning care.

When therapists work with trauma survivors, especially those who have long-term adverse effects from childhood maltreatment, they are mindful of 3 phases of work: (1) establishing safety (including in the therapeutic relationship), (2) remembering and mourning, and (3) reconnecting to ordinary life.7 Any survivor may cycle through these phases more than once if new challenges raise old issues. Prioritizing safety, developing trust, and supporting the life transitions associated with the childbearing year are timeless aspects of midwifery practice as well. Only the middle-phase work of welcoming the client to link current reactions to past trauma and co-creating trauma-specific practices to respond may be new within the midwife-client relationship.

When midwives are themselves survivors of trauma, they may need to assess their own level of resilience or recovery and consider if they are at risk for being triggered by vicarious reminders of their own history. Any professional who works with trauma survivors may develop secondary trauma.61 Consulting a psychotherapist, whether for personal treatment or reflective supervision, can be very helpful. Finally, health care providers usually work at a micro level, focusing on interpersonal practice. But delivering trauma-specific care requires attention to the macro level as well. Systems change may be needed to put in place policies, environmental modifications, and a different work culture to make trauma-specific practice sustainable.

Race- and Ethnicity-Based Health Disparities

Recent awareness of population-level trauma has begun the process of seeing trauma as a human rights issue. The evidence-based interventions reviewed in this article target individual mental health, which is a coherent paradigm when viewed via the lens of trauma experience being an event that happens to a person. This individual paradigm is now being expanded to recognize trauma as human rights violations that have been allowed to occur and directed toward specific populations such as BIPOC, women, children, prisoners, etc.62 Entirely different responses may emerge to address population trauma such as restorative justice, reparations, peaceful protest, institutional courage,32 restructuring, and policy change. Additional healing approaches may come into clear focus if a human rights perspective takes root in the health care system.

Recent research on trauma and race indicates that trauma may be a significant clinical pathway to prematurity and disparities in birth outcomes, maternal mental health, and population health across the life span for those who are BIPOC. Rates of PTSD are higher in perinatal care clients in predominantly Black settings and low-resource settings when compared with persons in predominantly white or high-resource settings.5,8,63,64 The additional toll of trauma from historic human rights violations, current discrimination, microaggressions, othering, and minority stress65–67 likely adds to the cumulative trauma burden experienced.62,65,68 Race-based structural inequities in access to care and safety mean that many clients who are BIPOC may also have fewer resources with which to address their trauma-related needs. In minority or marginalized populations, trauma-informed care thus requires attention to race-based or historic trauma in addition to person-specific trauma. As a document from the RYSE Center’s 2016 Racing ACEs meeting states, there is a race-trauma nexus such that “If it’s not racially just, it’s not trauma-informed.”68

CONCLUSION

Knowledge of current theories of posttraumatic stress can help health care providers who offer perinatal care realize the impact of trauma on the childbearing year; recognize the signs and symptoms of trauma in childbearing persons, families, staff, and others involved with the system; identify potential paths for recovery; and respond by integrating knowledge about trauma into policies, procedures, and practices.11 Theory meets ideals of the evidence-based practice paradigm at the individual level: to combine theory, preferences, values, and informed consent via a process of collaboration between client and health care provider. Using a theoretical understanding of posttraumatic stress, perinatal clinicians can then mitigate the widespread effects of trauma on individuals and populations by intervening through the 3 tiers of interventions reviewed in this article. Clinicians who are able to compassionately understand posttraumatic stress and respond using evidence-based programs, practices, treatments, and referrals can greatly increase the well-being of childbearing persons who are survivors of trauma and their families.

Quick Points.

A trauma-informed continuum of care includes universal, targeted, and specialist levels that articulate smoothly with each other.

A trauma-informed approach is universal. It is based on the assumption that a significant proportion of the client population has trauma history relevant to the health needs we meet—including historic trauma. As the RYSE Center put it, “If it’s not racially just, it’s not trauma-informed.”

Pregnancy, birth, breastfeeding, and early parenting are embodied and relational experiences that may have numerous triggers for trauma reactions. Referral to trauma-focused specialist treatment or medication is not sufficient as a response.

Midwives and other perinatal team members can implement trauma-specific programs for their clients, but ability to respond to recognition of triggered trauma reactions in the moment is a vital form of trauma-specific practice.

Several theories of what causes posttraumatic stress disorder can frame these moments and inform responses: (1) action system for danger versus action system for daily life, (2) failure of fear extinction, (3) betrayal trauma and injury to the attachment system, and (4) posttraumatic dysregulation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This review was funded in part by Predoctoral Fellowship Training Grant T32 NR016914 (Program Director: Titler) Complexity: Innovations in Promoting Health and Safety (September 1, 2018, to August 31, 2021) from the School of Nursing, University of Michigan.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Psychological Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yonkers KA, Smith MV, Forray A, et al. Pregnant women with post-traumatic stress disorder and risk of preterm birth. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(8):897–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seng JS, Low LK, Sperlich M, Ronis DL, Liberzon I. Post-traumatic stress disorder, child abuse history, birthweight and gestational age: a prospective cohort study. BJOG. 2011;118(11):1329–1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cook N, Ayers S, Horsch A. Maternal posttraumatic stress disorder during the perinatal period and child outcomes: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2018;225:18–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seng JS, Low LMK, Sperlich M, Ronis DL, Liberzon I. Prevalence, trauma history, and risk for posttraumatic stress disorder among nulliparous women in maternity care. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(4): 839–847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52(12):1048–1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herman JL. Trauma and Recovery. Basic Books; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Michopoulos V, Rothbaum AO, Corwin E, Bradley B, Ressler KJ, Jovanovic T. Psychophysiology and posttraumatic stress disorder symptom profile in pregnant African-American women with trauma exposure. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2015;18(4):639–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seng JS, Li Y, Yang JJ, et al. Gestational and postnatal cortisol profiles of women with posttraumatic stress disorder and the dissociative subtype. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2018;47(1):12–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stein DJ, Koenen KC, Friedman MJ, et al. Dissociation in posttraumatic stress disorder: evidence from the world mental health surveys. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73(4):302–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14–4884. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Montgomery E Feeling safe: a metasynthesis of the maternity care needs of women who were sexually abused in childhood. Birth. 2013;40(2):88–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Forbes D, Bisson JI, Monson CM, Berliner L. Effective Treatments for PTSD: Practice Guidelines from the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies. Guilford Publications; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ford JD, Courtois CA. Treating Complex Traumatic Stress Disorders in Adults: Scientific Foundations and Therapeutic Models. Guilford Publications; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 15.van der Hart O, Nijenhuis ER, Steele K. The Haunted Self: Structural Dissociation and the Treatment of Chronic Traumatization. WW Norton & Company; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Y, Hassett AL, Seng JS. Exploring the mutual regulation between oxytocin and cortisol as a marker of resilience. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2019;33(2):164–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dana DA. The Polyvagal Theory in Therapy: Engaging the Rhythm of Regulation. WW Norton & Company; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taylor SE, Klein LC, Lewis BP, Gruenewald TL, Gurung RA, Updegraff JA. Biobehavioral responses to stress in females: tend-and-befriend, not fight-or-flight. Psychol Rev. 2000;107(3):411–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Porges SW. Making the world safe for our children: down-regulating defence and up-regulating social engagement to ‘optimise’ the human experience. Children Australia. 2015;40(2):114–123. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lanius RA, Brand B, Vermetten E, Frewen PA, Spiegel D. The dissociative subtype of posttraumatic stress disorder: rationale, clinical and neurobiological evidence, and implications. Depress Anxiety. 2012;29(8):701–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lanius RA, Vermetten E, Loewenstein RJ, et al. Emotion modulation in PTSD: clinical and neurobiological evidence for a dissociative subtype. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(6):640–647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sloan DM, Marx BP. Written Exposure Therapy for PTSD: A Brief Treatment Approach for Mental Health Professionals. American Psychological Association; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Craske MG, Treanor M, Conway CC, Zbozinek T, Vervliet B. Maximizing exposure therapy: an inhibitory learning approach. Behav Res Ther. 2014;58:10–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosenwald GC, Ochberg RL. Storied Lives: The Cultural Politics of Self-Understanding. Yale University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Creedy DK, Shochet IM, Horsfall J. Childbirth and the development of acute trauma symptoms: incidence and contributing factors. Birth. 2000;27(2):104–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ford E, Ayers S. Support during birth interacts with prior trauma and birth intervention to predict postnatal post-traumatic stress symptoms. Psychol Health. 2011;26(12):1553–1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Freyd JJ. Betrayal Trauma: The Logic of Forgetting Childhood Abuse. Harvard University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Freyd JJ. Betrayal trauma: traumatic amnesia as an adaptive response to childhood abuse. Ethics Behav. 1994;4(4):307–329. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith CP, Freyd JJ. Institutional betrayal. Am Psychol. 2014;69(6): 575–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee C, Ayers SL, Kronenfeld JJ. The association between perceived provider discrimination, health care utilization, and health status in racial and ethnic minorities. Ethn Dis. 2009;19(3):330–337. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boulware LE, Cooper LA, Ratner LE, LaVeist TA, Powe NR. Race and trust in the health care system. Public Health Rep. 2003;118(4):358–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.The Call to Courage. Center for Institutional Courage. 2021. Accessed June 24, 2021. https://www.institutionalcourage.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 33.Demby G Making the case that discrimination is bad for your health. NPR, January 4, 2018. Accessed June 26, 2021. https://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2018/01/14/577664626/making-the-case-that-discrimination-is-bad-for-your-health [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blackburn S Maternal, Fetal, & Neonatal Physiology: A Clinical Perspective. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Epstein CM, Houfek JF, Rice MJ, Weiss SJ. Integrative review of early life adversity and cortisol regulation in pregnancy. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2021;50(3):242–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moberg KU. Oxytocin: The Biological Guide to Motherhood. Praeclarus Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Taylor SE. Tend and befriend: biobehavioral bases of affiliation under stress. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2006;15(6):273–277. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seng JS. Posttraumatic oxytocin dysregulation: is it a link among posttraumatic self disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder, and pelvic visceral dysregulation conditions in women? J Trauma Dissociation. 2010;11(4):387–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Teicher MH, Andersen SL, Polcari A, Anderson CM, Navalta CP, Kim DM. The neurobiological consequences of early stress and childhood maltreatment. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2003;27(1–2):33–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen WG, Schloesser D, Arensdorf AM, et al. The emerging science of interoception: sensing, integrating, interpreting, and regulating signals within the self. Trends Neurosci. 2021;44(1): 3–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schnurr PP, Green BL. Understanding relationships among trauma, posttraumatic stress disorder, and health outcomes. Adv Mind Body Med. 2004;20(1):18–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Seng JS, Sperlich M, Rowe H, et al. The survivor moms’ companion: open pilot of a posttraumatic stress specific psychoeducation program for pregnant survivors of childhood maltreatment and sexual trauma. Int J Childbirth. 2011;1(2):111–121. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thomson M, Sharma V. Pharmacotherapeutic considerations for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder during and after pregnancy. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2021;22(6):705–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2001: Mental Health: New Understanding, New Hope. World Health Organization; 2001. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42390 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Seng JS, Sparbel KJH, Low LK, Killion C. Abuse-related posttraumatic stress and desired maternity care practices: women’s perspectives. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2002;47(5):360–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sperlich M, Seng JS. Survivor Moms: Women’s Stories of Birthing, Mothering and Healing After Sexual Abuse. Motherbaby Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stein MB, McQuaid JR, Pedrelli P, Lenox R, McCahill ME. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the primary care medical setting. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2000;22(4):261–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Prins A, Ouimette P, Kimerling R, Camerond RP, Hugelshofer DS, Shaw-Hegwer J, Thrailkill A, Gusman FD, Sheikh JI. The primary care PTSD screen (PC–PTSD): development and operating characteristics. Primary Care Psychiatry. 2004;9:(1):9–14. 10.1185/135525703125002360 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weinreb L, Wenz-Gross M, Upshur C. Postpartum outcomes of a pilot prenatal care-based psychosocial intervention for PTSD during pregnancy. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2018;21(3):299–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Simkin P, Klaus P. When Survivors Give Birth: Understanding and Healing the Effects of Early Sexual Abuse on Childbearing Women. Classic Day; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Najavits LM, Weiss RD, Shaw SR, Muenz LR. “Seeking safety”: outcome of a new cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy for women with posttraumatic stress disorder and substance dependence. J Trauma Stress. 1998;11(3):437–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Baas MA, van Pampus MG, Braam L, Stramrood CA, de Jongh A. The effects of PTSD treatment during pregnancy: systematic review and case study. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2020;11(1):1762310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stevens NR, Miller ML, Puetz AK, Padin AC, Adams N, Meyer DJ. Psychological intervention and treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder during pregnancy: a systematic review and call to action. J Trauma Stress. 2020;34(3):575–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schauer M, Neuner F, Elbert T. Narrative Exposure Therapy: A Short-Term Intervention for Traumatic Stress Disorders After War Terror, or Torture. Hogrefe & Huber Publishers; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Frost ND, Laska KM, Wampold BE. The evidence for present-centered therapy as a treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder. J Trauma Stress. 2014;27(1):1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ogden P, Fisher J. Sensorimotor Psychotherapy: Interventions for Trauma and Attachment. WW Norton & Company; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kabat-Zinn J Coming to Our Senses: Healing Ourselves and the World Through Mindfulness. Hachette UK; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Karatzias T, Cloitre M. Treating adults with complex posttraumatic stress disorder using a modular approach to treatment: rationale, evidence, and directions for future research. J Trauma Stress. 2019;32(6):870–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hale TW. Hale’s Medications & Mothers’ Milk: A Manual of Lactational Pharmacology. Springer; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Food and Drug Administration. Content and format of labeling for human prescription drug and biological products; requirements for pregnancy and lactation labeling. Final rule. Fed Regist. 2014;79(233):72063–72103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Van Dernoot Lipsky L Trauma Stewardship: An Everyday Guide to Caring for Self While Caring for Others. Berrett-Koehler Publishers; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Butler LD, Critelli F, Carello J. Trauma and Human Rights. Springer; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Seng JS, Kohn-Wood LP, McPherson MD, Sperlich M. Disparity in posttraumatic stress disorder diagnosis among African American pregnant women. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2011;14(4):295–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cook CAL, Flick LH, Homan SM, Campbell C, McSweeney M, Gallagher ME. Posttraumatic stress disorder in pregnancy: prevalence, risk factors, and treatment. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103(4): 710–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Livingston NA, Berke DS, Ruben MA, Matza AR, Shipherd JC. Experiences of trauma, discrimination, microaggressions, and minority stress among trauma-exposed LGBT veterans: unexpected findings and unresolved service gaps. Psychol Trauma. 2019;11(7):695–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Resick PA, Monson CM, Chard KM. Cognitive Processing Therapy for PTSD: A Comprehensive Manual. Guilford Publications; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shapiro F EMDR, Adaptive Information Processing, and Case Conceptualization. J. EMDR Pract. Res 2007;1:(2):68–87. 10.1891/1933-3196.1.2.68 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dhaliwal K; RYSE Center. Reflected. Rejected. Altered: Racing ACEs Revisited. RYSE Center; 2016. http://www.bmsg.org/resources/publications/rejected-reflected-altered-racing-aces-revisited/ [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ehlers A, Clark DM. A cognitive model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Behav Res Ther. 2000;38(4):319–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Powers MB, Halpern JM, Ferenschak MP, Gillihan SJ, Foa EB. A meta-analytic review of prolonged exposure for posttraumatic stress disorder. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30(6):635–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]