Abstract

Objectives:

Gut-produced trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) is postulated as a possible link between red meat intake and poor cardiometabolic health. We investigated whether gut microbiome could modify associations of dietary precursors with TMAO concentrations and cardiometabolic risk markers among free-living individuals.

Design:

We collected up to 2 pairs of fecal samples (n=925) and 2 blood samples (n=473), 6 months apart, from 307 healthy men in the Men’s Lifestyle Validation Study. Diet was assessed repeatedly using food-frequency questionnaires and diet records. We profiled fecal metagenome and metatranscriptome using shotgun sequencing and identified microbial taxonomic and functional features.

Results:

TMAO concentrations were associated with the overall microbial compositions (PERMANOVA test P=0.001). Multivariable taxa-wide association analysis identified 10 bacterial species whose abundance was significantly associated with plasma TMAO concentrations (FDR<0.05). Higher habitual intake of red meat and choline was significantly associated with higher TMAO concentrations among participants who were microbial TMAO-producers (P<0.05), as characterized based on 4 abundant TMAO-predicting species, but not among other participants (for red meat, P-interaction=0.003; for choline, P-interaction=0.03). Among abundant TMAO-predicting species, Alistipes shahii significantly strengthened the positive association between red meat intake and HbA1c levels (P-interaction=0.01). Secondary analyses revealed that some functional features, including choline trimethylamine-lyase activating enzymes, were associated with TMAO concentrations.

Conclusion:

We identified microbial taxa that were associated with TMAO concentrations and modified the associations of red meat intake with TMAO concentrations and cardiometabolic risk markers. Our data underscore the interplay between diet and gut microbiome in producing potentially bioactive metabolites that may modulate cardiometabolic health.

Keywords: Diet, Gastrointestinal Microbiome, Red meat, Trimethylamine N-oxide, Cardiovascular Diseases

INTRODUCTION

The gut microbiota plays a vital role in the pathogenesis of cardiometabolic diseases,[1–3] and the underlying mechanisms involve, at least partially, metabolites produced by gut microorganisms.[1–3] In particular, trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) has shown atherogenic effects in animal studies,[2, 3] and its circulating levels were associated with a higher incidence of cardiovascular events[4, 5] and unfavorable metabolic traits (e.g., blood lipids and glycemic traits)[6] in some epidemiological studies. Prior evidence suggests that the consumption of foods high in choline/L-carnitine such as red meat could lead to the production of trimethylamine (TMA) by the gut microbiome, which is rapidly absorbed into circulation and converted to TMAO by hepatic flavin monooxygenases.[2, 7] As such, TMAO is postulated as a possible culprit linking the observed epidemiological associations between red meat intake and poor cardiometabolic health.[2, 3] Meanwhile, as a natural source of TMAO independent of microbial metabolism, fish intake is associated with higher TMAO levels[8, 9] but not increased cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk,[10] adding complexity to the relationship between diet, microbiome, circulating TMAO levels, and cardiovascular health in free-living populations.

Individuals with different gut microbial compositions may have different capacities for producing gut-related metabolites after consuming the same diet.[11, 12] However, little is known regarding which microbial taxa are responsible for TMA/TMAO production in free-living individuals. Prior experimental studies suggested that several microbial enzyme complexes are capable of metabolizing choline/L-carnitine into TMA.[2, 3] Several microbial taxa (at order to genus levels, such as Clostridium) were identified to predict circulating TMAO levels in animal studies[2, 3, 13, and 14] and small-scale human studies in which L-carnitine challenge tests were administered.[12, 14] Recent bioinformatic/biochemistry studies also proposed several potential TMA-producing bacterial species by screening microbial reference genomes for the sequence of candidate gene complexes.[15–17] However, this evidence may not be generalizable to free-living individuals, whose diets consist of complex combinations of various animal and plant foods at different intake levels (vs. L-carnitine challenge tests) and whose gut microbial activities may depend on both microbial compositions and long-term diet (vs. reference genome screening). In addition, it is unknown whether TMA-producing taxa could interact with dietary TMA precursors in association with circulating TMAO levels and cardiometabolic traits, in free-living populations.

We hereby addressed this important knowledge gap by leveraging a cohort of free-living men whose diet/lifestyle, microbiome, and plasma biomarkers were comprehensively assessed repeatedly over a period of one year (Figure 1A). We first conducted a feature-wide association analysis of microbial taxa to identify microbial species that were significantly associated with plasma TMAO concentrations. We then tested the hypothesis that TMAO-predicting microbial species modify the association of intakes of red meat or choline with plasma TMAO concentrations and cardiometabolic risk biomarkers. In a secondary analysis, we examined other TMA precursors, including intakes of egg, dairy, and fish, and plasma concentrations of choline and L-carnitine.

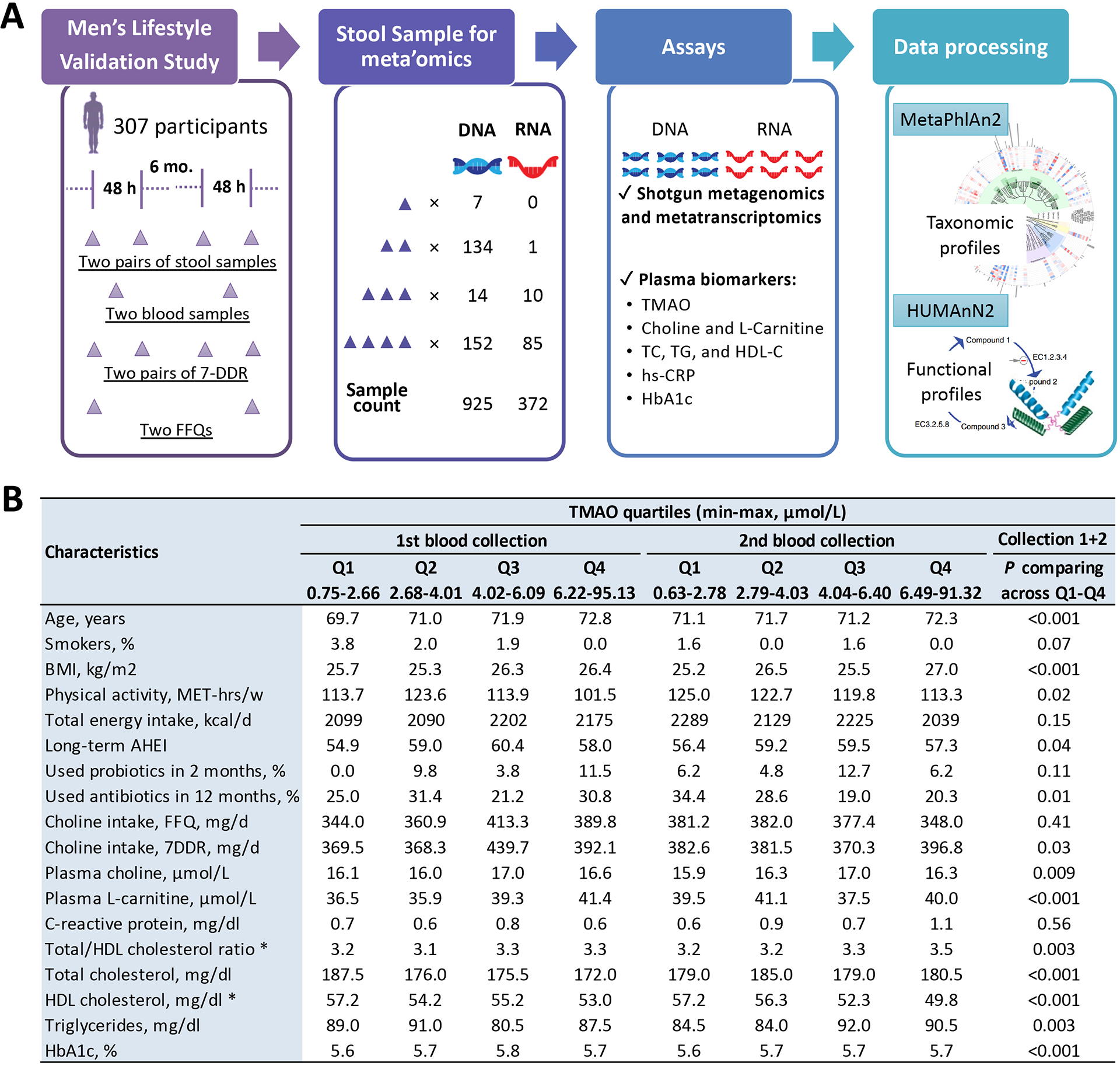

Figure 1. Study design and basic characteristics of the study participants.

A. The overall study design, sample collections, and laboratory assays in the Men’s Lifestyle Validation Study. B. Basic characteristics of the study participants, by quartiles of plasma TMAO concentrations assessed in blood samples collected 6 months apart. In the combined dataset of all repeated collections, distribution of each characteristics was compared across TMAO quartiles (P was showed in the column#) and between the two collections (* indicates the characteristics with a P<0.05) using a univariate generalized linear mixed-effects regression (for continuous variables) or a Chi-square test (for binary variables). Abbreviation: FFQ, food frequency questionnaire; 7DDR, 7-day diet records; TMAO, trimethylamine N-oxide; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol; hs-CRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; MET, metabolic equivalent task; BMI, body mass index; AHEI, alternative healthy eating index; and Q1–Q4; 1st – 4th quartiles.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

The Health Professionals Follow-up Study (HPFS) is a prospective cohort that started in 1986, enrolling 51,529 male health professionals. Participants were followed biennially to assess lifestyle, medical history, and other health-related information. The Men’s Lifestyle Validation Study (MLVS) is a 1-year sub-study carried out during 2011–2012 aiming to validate self-reported diet/lifestyles. About 700 HPFS men (aged 52–81 years) who donated blood samples during 1994–1995, returned completed food frequency questionnaires (FFQ) in the 2010 follow-up survey, and were free of CVD, cancer, and major neurological diseases, consented to participate in the MLVS. Dietary, lifestyle, and health-related data were repeatedly collected.[18] A total of 308 MLVS participants provided up to two pairs of self-collected stool samples from consecutive bowel movements; each pair of samples were collected 24–72 hours apart, and the two pairs were collected approximately 6-month apart.[18] Two blood samples and 24-h urine samples were collected, 6-month apart, to coincide with the timing of the fecal sample collection (Figure 1A). Detailed information on MLVS has been published previously.[18, 19] The study protocol was approved by the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health Institutional Review Board. All participants provided written informed consent. Our study included 307 MLVS men with valid microbiome data.

Dietary assessments

At the first and last months of MLVS, two validated FFQs were administered, the first to assess habitual diets 1-year preceding MLVS, and the latter to assess diets during the MLVS period.[20] Two sets of 7-day diet records (7DDRs) were administered during the stool sample collection period, 6 months apart, to record detailed daily consumptions for 7 consecutive days[20] (Figure 1A). Thereby, we used the two FFQs to assess habitual diet in 1-year, and the 7DDRs to assess shorter-term diet in a few days, immediately preceding fecal sample collection. Nutrient intake (including total energy and choline) was calculated from FFQs based on the Harvard University Food Composition Database, and from 7DDRs based on the Nutrition Data System for Research at the University of Minnesota Nutrition Coordinating Center.[20] L-carnitine intake was not derived due to the lack of food composition data. In addition, HPFS participants completed FFQs in 1986 and every 4 years thereafter. We calculated the cumulative average of alternative healthy eating index (AHEI) [21] based on all FFQs during 1986–2010 to measure long-term diet quality.

Biomarker measurements

Plasma concentrations of TMAO, choline, and L-carnitine, were measured using electrospray ionization orbitrap liquid chromatography mass spectrometry.[22] Plasma concentrations of total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG), and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), were quantified by a Hitachi 911 analyzer using reagents from Roche Diagnostics (Indianapolis, IN). Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) was measured by turbidimetric immunoinhibition using packed erythrocytes (Roche Diagnostics). High-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) was measured on a Hitachi 911 system using a latex-enhanced immunoturbidimetric assay from Denka Seiken (Tokyo, Japan). Urinary excretion of creatinine (UCr) was measured with a modified Jaffe kinetic assay (Olympus) using 24-h urine samples. Relative plasma creatinine levels (PCr) were assessed using a high-throughput liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry at the Broad Institute of Harvard University and M.I.T. (Cambridge, MA). We randomly inserted 10% blinded quality control (QC) samples, and the coefficients of variation among these samples were 18.1% for TMAO and <7% for other biomarkers.

Shotgun sequencing, and taxonomic and functional profiling

Details on sample processing and sequencing have been provided previously.[18, 19] Briefly, fecal DNA was prepared by Nextera XT DNA Library Preparation Kit for whole-genome sequencing, and fecal RNA was prepared by RNAtag-Seq for RNA sequencing. We used Illumina HiSeq paired-end (2×101 nucleotides) shotgun sequencing to obtain 929 metagenomes and 372 metatranscriptomes (for 372 fecal RNA samples from a subset of 96 men). QC was performed according to HMP protocols with KneadData. The sequencing depth (mean ± standard deviation [SD]) for DNA was 3.8±1.6 giganucleotides (Gnt) before QC and 1.8±0.7 Gnt after, and for RNA was 2.8±2.4 Gnt before QC and 1.2±1.0 Gnt after.[18, 19]

We performed taxonomic profiling using MetaPhlAn2[23] and functional profiling using HUMAnN2.[24] For taxonomic features, we excluded those with a relative abundance <10−4 (0.01%) in over 10% of all observations; for functional features, we excluded those with a relative abundance <10−5 (0.001%) in over 10% of all observations. After QC filtering, no outlier was observed in multidimensional scaling analysis of taxonomic features.

Assessment of Covariates

Demographics, medical histories, and smoking status were collected at MLVS baseline. Lifestyles, physical activity, and anthropometrics were evaluated around the time of blood collection. Information on use of probiotics and antibiotics, surgical procedures, and the Bristol Stool Chart were collected through fecal sample collection questionnaires. We calculated a relative glomerular filtration rate (GFR) using formula GFR = (UCr × 24-h urine Volume) / relative PCr, which accounts for individual variation in renal function.[25] We defined individuals with 5.7%≤ HbA1c<6.5% as potentially prediabetic and those with HbA1c≥6.5% as potentially diabetic according to criteria from the American Diabetes Association.[26]

Statistical Analysis

Circulating biomarkers were corrected for batch effects,[27] natural-log transformed to a normal distribution, and winsorized at mean ±4SD. All biomarker and relative GFR were standardized so that each unit corresponded to 1-SD. We excluded extreme outliers of dietary intakes. We matched each of the microbiome measurements to the biomarkers, diet, and other variables collected at the time closest to the time of fecal sample collection. For example, the 1st and 2nd metagenomes/metatranscriptomes (i.e., the first pair of fecal samples) were each matched to biomarkers measured using the first blood collection, habitual diet assessed by the first FFQ, and recent diet assessed as average intakes from the 7DDRs within 5 constitutive days before fecal sample collection. The same strategy was used to match the second pair of fecal metagenomes/metatranscriptomes with the corresponding diet and biomarkers. For primary exposures and outcomes, we excluded missing values (average missing rate=0.7%) from analyses. For covariates, we replaced missing values of continuous variables (average missing rate=1.9%) with the mean value calculated among the rest of the participants. Given the low missing rate for the binary covariates (e.g., probiotic use and antibiotic use; average missing rate=1%), we assumed the missing values as zero (i.e., no).

We performed principal coordinates analysis based on Bray-Curtis dissimilarity using taxonomic data at the species level. We used repeated-measures and multivariable-adjusted PERMANOVA test to assess associations between the overall microbial community and TMAO concentrations. Transcriptomic features were normalized to the corresponding DNA abundance.[19] Arc-sin square root transformation was applied to relative abundances of taxonomic/functional features before association analyses. Feature-wide associations of microbial taxa with TMAO concentrations and TMAO precursors were analyzed using generalized random-effects linear regressions implemented in MaAsLin2. Multivariable models were adjusted for age, body-mass index (BMI), calorie intake, physical activity, smoking status, cumulatively averaged AHEI scores, probiotic use, antibiotic use, colonoscopy, acid use, Bristol stool chart, and fish intake (for TMAO analyses). The circular phylogenetic tree was produced by GraPhlAn in Python v3.6.4. In secondary analyses, we analyzed associations between functional features within the identified microbial taxa with TMAO concentrations and TMAO precursors (see Supplementary Methods).

To ensure sufficient statistical power for interaction analyses between diet and the gut microbiome, we defined a microbial TMAO-producer phenotype based on TMAO-predicting species that had relative abundance >0.1% and were present in >50% of the participants if the species were positive predictors of TMAO or absent in >50% of the participant if negative predictors. Participants were categorized as gut microbial TMAO-producers if they carried the species that were positively associated with TMAO concentrations and did not carry the species that were inversely associated with TMAO concentrations. We assessed the associations between dietary precursors and TMAO levels using multivariable linear mixed-effect regressions (with generalized least squares estimator). We then stratified the analyses by the TMAO-producer phenotype and examined the interactions between the TMAO-producer phenotype and each dietary precursor by including an interaction term between the two variables in multivariable models. In secondary analyses, we assessed effect modifications by individual species.

We performed several sensitivity analyses. First, because renal function has been shown to influence plasma TMAO levels,[7, 28] we additionally adjusted for relative GFR levels to account for potential confounding in all analyses involving TMAO concentrations. Second, for feature-wide association analyses of TMAO and interaction analyses between diet and TMAO-producer phenotype, we additionally adjusted for dietary phosphorus intake, HbA1c levels or prediabetic/diabetic status, or excluded participants with HbA1c≥6.5% from analysis. For the interaction analyses between dietary precursors and TMAO-producer phenotype, we further controlled for other dietary precursors in separate models. Third, for recent diet prior to fecal sample collection, we compared 5-day average intakes to 2-day average intakes for their associations with TMAO with/without stratification by TMAO-producer phenotype.

Finally, we analyzed associations between TMAO and cardiometabolic risk biomarkers. We examined whether associations between red meat intake and cardiometabolic risk biomarkers were modified by TMAO-producer phenotype or individual species, with additional adjustment for refined carbohydrate and fiber intake. Associations or interactions with a false discovery rate (FDR)<0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using R v3.6.1.

RESULTS

A total of 925 metagenomes of fecal samples repeatedly collected from 307 men (average age =71.4 years) were included in the main analyses (Figure 1A). All participants reported regular consumption of a variety of animal and plant foods for over two decades (Table S1). At both blood draws, men with higher TMAO levels were older and less physically active, more likely to be non-smokers and have a higher BMI and lower levels of HDL-C. They were also more likely to consume more dietary choline and have higher plasma levels of choline and L-carnitine (Figure 1B, Table S2).

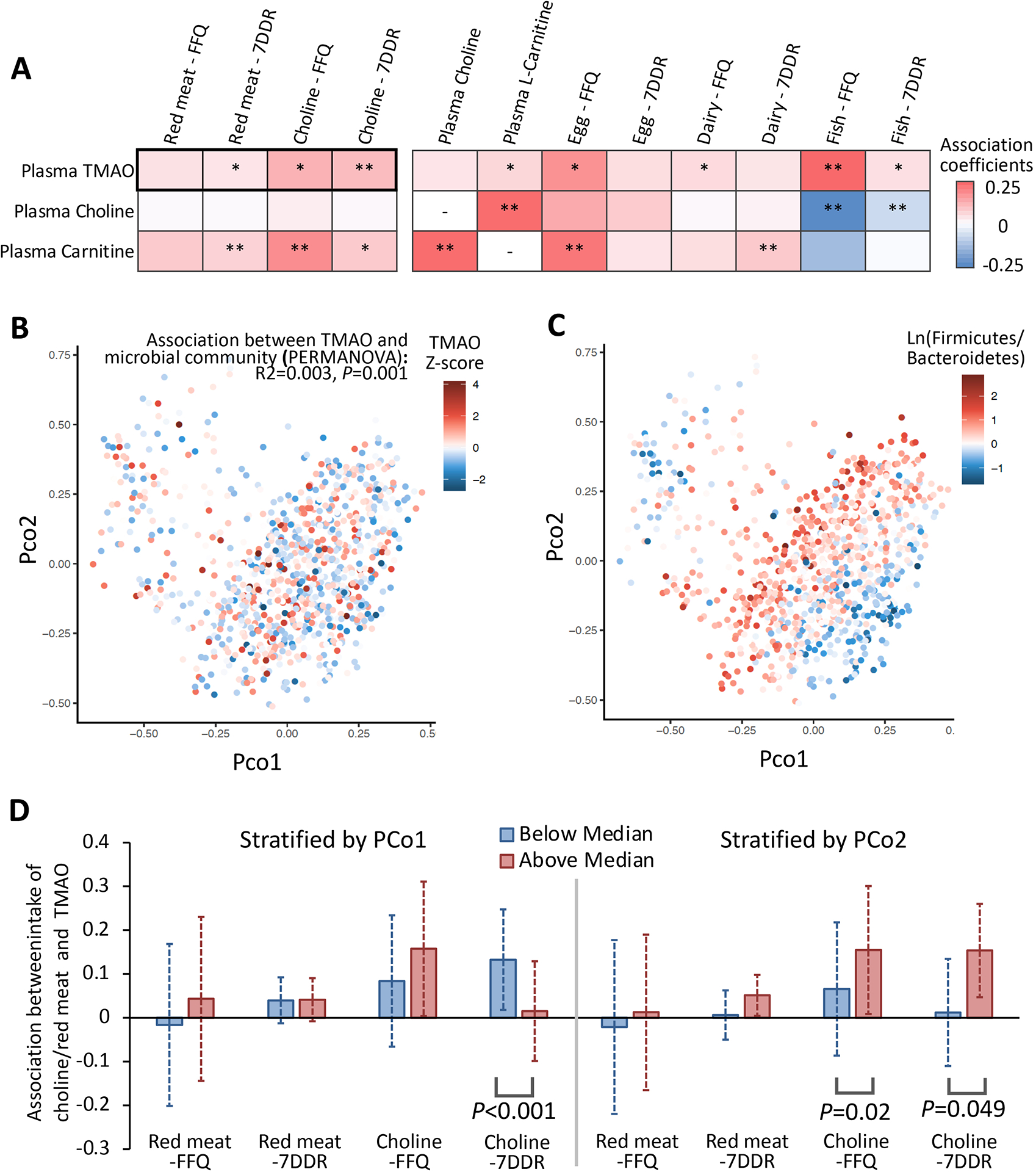

In multivariable analysis, higher habitual and recent intake of choline, and recent intake of red meat, were associated with increased plasma TMAO concentrations (P<0.05). In secondary analyses, habitual intake of egg and dairy was positively associated with TMAO concentrations. Consistent with prior evidence,[29] higher fish intake was significantly associated with increased plasma TMAO but lower choline, and was not associated with L-carnitine concentrations. (Figure 2A, Figure S1). These results did not change after further adjusting for relative GFR, which was inversely associated with TMAO concentrations (Figure S2–S3A).

Figure 2. Red meat and choline intake, microbial communities, and plasma TMAO levels.

A presents association of intakes of red meat and choline, and secondarily, other TMAO precursors, with circulating TMAO concentrations. Generalized linear mixed-effects regressions were adjusted for BMI, smoking, physical activity, calorie intake, cumulatively averaged alternate healthy eating index and/or fish intake (for associations between dietary variables other than fish and TMAO). *, P<0.05 and **, FDR<0.05. In B and C, principal coordinates analysis based on Bray-Curtis dissimilarity were performed using taxonomic data at the species level; the first 2 principal coordinates (PCo) were plotted by plasma TMAO levels and Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes ratio. A PERMANOVA test was used to evaluate the association between the overall microbial compositions and TMAO concentrations. D presents associations between intakes of red meat and choline with TMAO levels, stratified by PCo 1 or 2. In B-D, multivariable models were further adjusted for probiotic use, antibiotic use, and the Bristol stool chart.

Of the 1,211 profiled taxonomic features, 386 at different phylogenetic levels were retained after quality filtering; these included 139 species from 7 phyla spanning 3 kingdoms (archaea, bacteria, and viruses). Based on the 139 species, the overall microbial communities showed a significant, albeit weak, association with TMAO concentrations in multivariable analyses even after adjusting for renal function (R2=0.003, P=0.001) (Figure 2B, Figure S3B). The first two principal coordinates (PCo) of gut species largely reflected compositions of Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes (Figure 2C). Notably, in multivariable analyses, the association between recent choline intake and TMAO levels was more prominent among men with a lower PCo1 (P-interaction<0.001), and associations of habitual and recent choline intake with TMAO levels were more pronounced among men with a higher PCo2 (P-interaction <0.05) (Figure 2D, Figure S3D–S4), suggesting that the overall microbial composition may play a role in TMAO production. We did not observe significant interactions between PCo and red meat intake on TMAO concentrations.

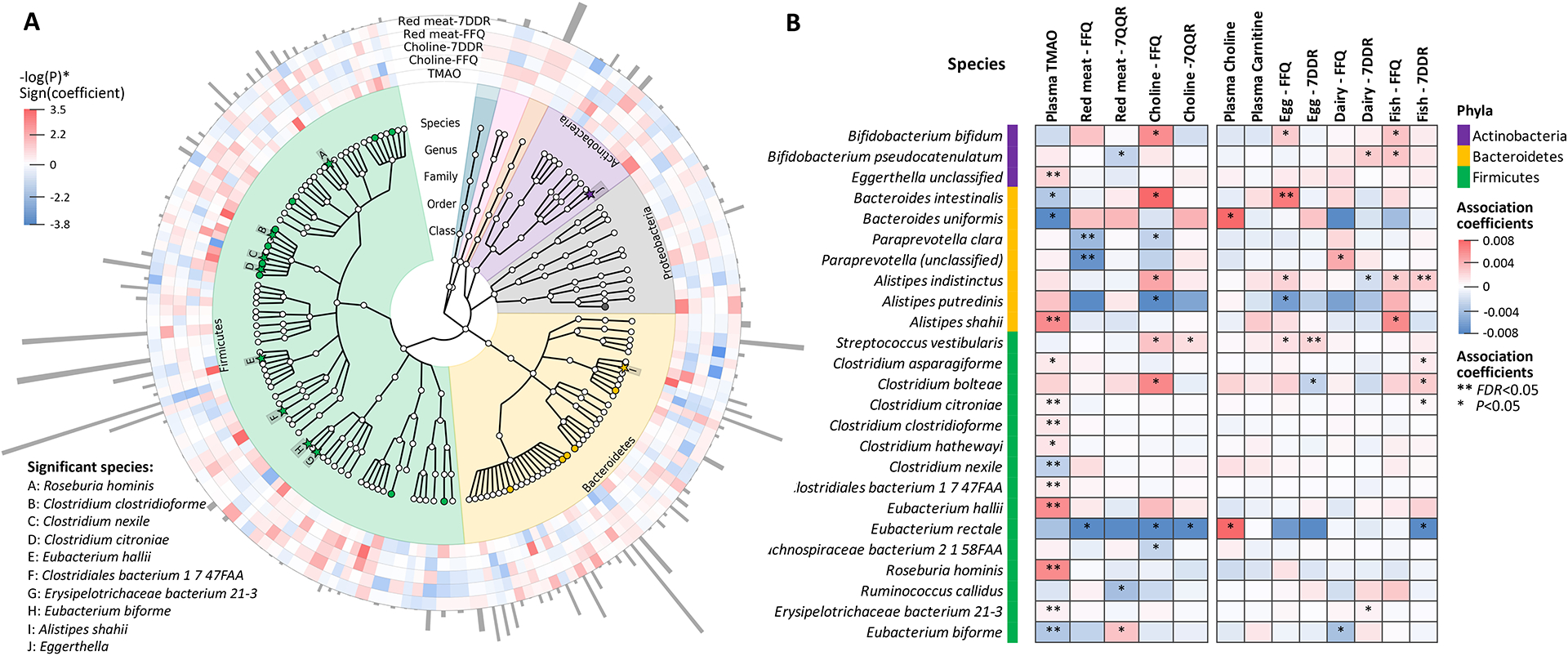

Of the 139 species, we identified 10 species whose abundance was significantly associated with plasma TMAO concentrations (FDR<0.05). These included 8 Firmicutes species (namely Clostridium citroniae, C. nexile, C. clostridioforme, Clostridiales bacterium 1 7 47FAA, Eubacterium hallii, E. biforme, Erysipelotrichaceae bacterium 21–3, and Roseburia hominis), one Bacteroidetes species (Alistipes shahii), and one Actinobacteria species (Eggerthella unclassified). The average abundance of 4 species was relatively higher (>0.1%) while the other 6 were less abundant (0.005–0.1%) (Figure 3A, Supplementary Data 1a). The 10 species showed zero to weak correlations between each other, except for those in the same genus (Figure S5). We identified another 14 species, including 9 in Firmicutes (e.g., C. hathewayi) and 5 in Bacteroidetes, showing nominal association with TMAO concentrations (P<0.05) (Figure 3A, Supplementary Data 1a). We did not find significant overlap between species associated with TMAO concentrations and those associated with its dietary precursors (P-enrichment >0.05) (Figure 3B, Table S3).

Figure 3. Taxonomic features associated with plasma TMAO concentrations.

A presents the phylogenetic tree for taxonomic features qualified for analysis, highlighting features significantly associated with plasma TMAO concentrations (solid stars with letter labels, FDR<0.05; solid circles, P<0.05). The outside rings denote associations of each species with TMAO levels and intakes of red meat and choline (red, positive associations; blue, inverse associations; color depth, statistical significance), and the abundance of each species are portrayed with grey bars. B compares the selected species for their associations with plasma TMAO concentrations, red meat and choline intake, and other potential TMAO precursors. Species associated with TMAO, or choline or red meat intake at P<0.01 were presented. Colors of cells indicate association coefficients, and asterisks denote association significance (** FDR<0.05, * P<0.05). Generalized linear mixed-effects regressions implemented in MaAsLin2 were adjusted for repeated measurements (participants ID as random intercept), age, BMI, smoking, physical activity, calorie intake, cumulatively averaged alternate healthy eating index, probiotic use, antibiotic use, colonoscopy or acid use in the past 2 months, Bristol stool chart, and/or fish intake (for analyses of TMAO).

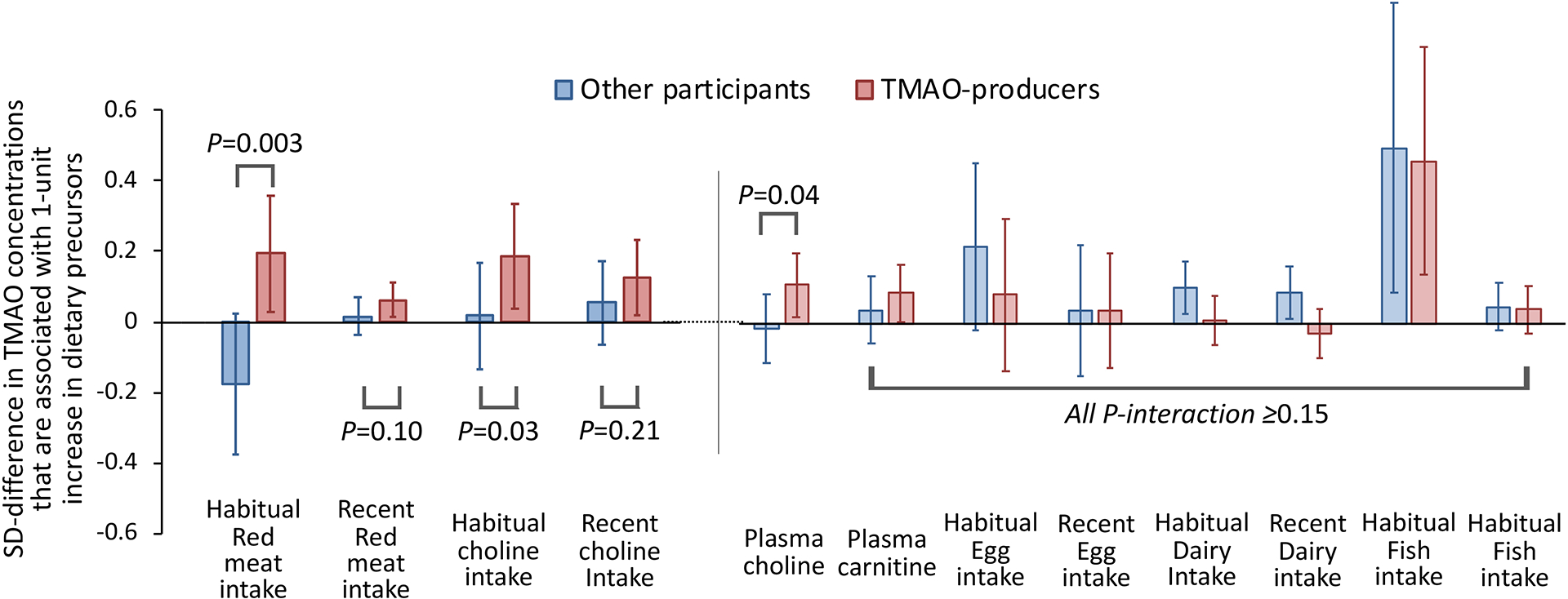

We then categorized our study samples as gut microbial TMAO-producers (i.e., carried E. hallii, R. hominis, and A. shahii, and did not carry E. biforme; 49% of all observations), or others, based on 4 TMAO-predicting species that met our pre-specified criteria. In multivariable analyses, higher habitual and recent intakes of red meat and choline were associated with increased TMAO concentrations only among microbial TMAO-producers (P<0.05), but not among other participants. The microbial TMAO-producer phenotype showed a significant interaction with habitual red meat intake (P-interaction =0.003, corresponding to an FDR of 0.03) and a marginally significant interaction with habitual choline intake (P-interaction=0.03), in association with TMAO concentrations. We did not find significant effect modification by the microbial TMAO-producer phenotype on intakes of secondary dietary precursors such as egg and dairy. Notably, higher habitual fish intake was significantly associated with higher TMAO levels regardless of the microbial TMAO-producer phenotype (Figure 4, Figure S7). Secondary analyses suggested that the significant effect modification on habitual red meat intake was primarily driven by A. shahii and E. biforme while other species also showed a consistent direction for effect modification (Supplementary Data 2a).

Figure 4. Associations between intakes of red meat or choline with plasma TMAO concentrations, among participants who were categorized as gut microbial TMAO- producers and others.

The microbial TMAO-producer phenotype was categorized based on 4 TMAO-predicting species, including E. hallii (presence), E. biforme (absence), R. hominis (presence), and A. shahii (presence). The y-axis and bars (and lines) indicate the SD-differences (and 95% confidence intervals) in TMAO concentrations that are associated with 1-serving increase in foods intake or 1-SD increase in choline intake or in biomarkers. Generalized linear mixed-effects models were adjusted for age, BMI, smoking, physical activity, calorie intake, cumulatively averaged alternate healthy eating index, probiotic use, antibiotic use, Bristol stool chart, and/or fish intake (for dietary variables other than fish).

Findings from taxa-wide assocation analysis of TMAO and diet-micorbiome interaction analyses did not materially change in sensiticity analyses in which we further adjusted for other potential confounding including renal function, phosphorus intake, HBA1c levels, prediabetic/diabetic status, or other dietary precursors or bacterial species (for interaction analyses), or excluded participants with HBA1c≥6.5% from analyses (Figures S6 and S8, Supplementary Data 1b and 2a–c). In another sensitivity analysis, 5-day average intakes of dietary precursors and 2-day average intakes (based on 7DDR assessments) were strongly correlated with each other (Figure S3C), and showed similar associations with TMAO concentrations (Figure S3A) and similar interactions with TMAO-producer phenotype in association with TMAO concentrations (Supplementary Data 2c).

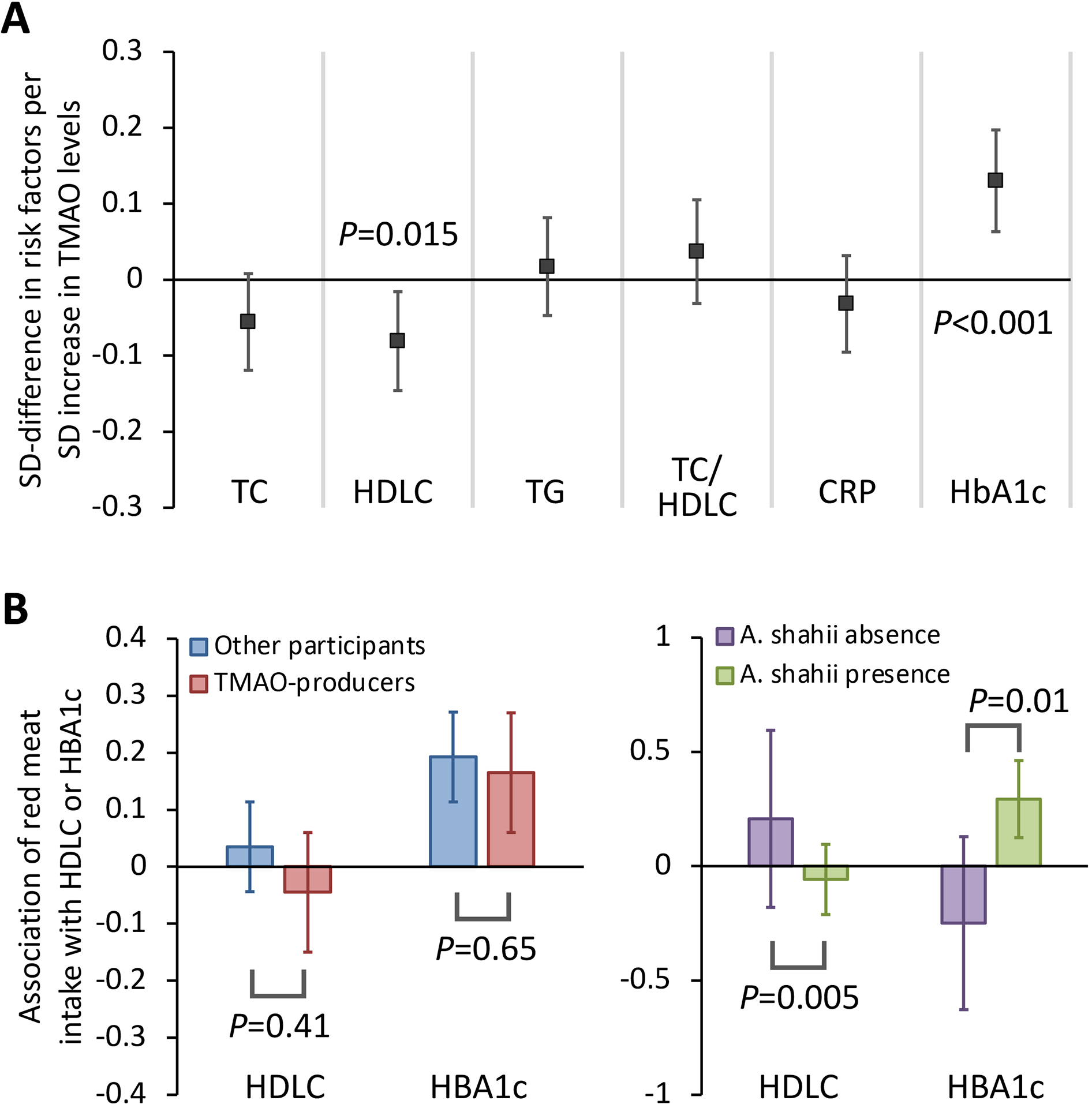

The microbial production of TMAO is postulated to partially mediate associations between red meat intake and cardiometabolic traits.[4, 14] In our study, habitual red meat intake was associated with an unfavorable profile of cardiometabolic risk biomarkers (Table S4). Each SD increment in plasma TMAO levels was associated with a 0.13 SD increment in HbA1c levels (R2=1.6%, P<0.001) and a 0.08 SD decrease in HDL-C levels (R2=0.6%, P=0.015) (Figure 5A). When examining whether the associations between habitual red meat intake and levels of HbA1c and HDL-C differed between microbial TMAO-producers and other participants, we found no evidence for significant effect modification (Figure 5B). Secondary analyses on individual species suggested that A. shahii significantly strengthened the positive associations between red meat intake and HbA1c levels (P-interaction=0.01), and also interacted with red meat intake in association with HDL-C levels (P-interaction=0.005) (Figure 5B, Supplementary Data 2d).

Figure 5. Red meat intake, TMAO levels, and cardiometabolic risk markers.

A presents the associations between plasma TMAO levels and cardiometabolic risk markers. Generalized linear mixed-effect regressions were adjusted for age, BMI, smoking, physical activity, calorie intake, cumulatively averaged alternate healthy eating index. B presented associations of red meat intake with levels of HDL-C and HbA1c, stratified by the microbial TMAO-producer phenotype and A. shahii. Multivariable models were further adjusted for fish intake, refined carbohydrate intake, fiber intake, probiotic use, antibiotic use, and the Bristol stool chart. TC, total cholesterol; HDLC, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; TG, triglycerides; TC/HDLC, ratio of total to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; CRP, C-reactive protein; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c.

In secondary analyses of functional features, we first examined previously reported TMAO-producing gene clusters, such as choline trimethylamine-lyase and activating enzyme (CutC/D) and carnitine monooxygenase oxygenase/reductase (CntA/B and YeaW/X). In our functional profiling, members in these clusters had low abundance and thus did not pass quality filtering (see Supplementary Methods). Nevertheless, participants with these genes had generally higher TMAO concentrations compared to those without (Figure S9). We then focused on the functional features within the 10 species predicting TMAO levels. We identified 14 characterized gene clusters and 38 named enzymes (within A. shahii, R. hominis, E. biforme, and/or E. hallii) and 43 pathways (within A. shahii, C. clostridioforme, C. nexile, Clostridiales bacterium 1 7 47FAA, E. biforme, E. hallii, and R. hominis) whose DNA abundance was significantly associated with TMAO concentrations (FDR<0.05) (Supplementary Data 3a, 4a, 5a). These enzymes/pathways are related to functions such as energy and cellular metabolism, homeostasis, and nucleotide functions. We barely identified any associations between microbial gene transcriptions (i.e., RNA/DNA ratio) and TMAO levels after multiple testing corrections (Supplementary Data 3b, 4b, 5b), possibly due to lack of statistical power.

DISCUSSION

Leveraging repeated measurements from a longitudinal study of healthy men, our study is the first to identify gut microbial species associated with plasma TMAO concentrations in free-living individuals. Habitual intake of red meat and choline was associated with higher TMAO levels only in participants identified as TMAO-producers, but not among the others. Of the TMAO-predicting species, A. shahii significantly strengthened the positive association between red meat intake and levels of HbA1c. These new data underscore that the interplay between diet and the gut microbiome plays an important role in producing potentially bioactive metabolites and possibly affecting cardiometabolic health.

We noted many consistencies between TMAO-predicting species identified by our study and those previously identified through experimental and/or bioinformatic/biochemical approaches,[12–17] supporting the biological plausibility of our results. For instance, Clostridium was correlated with higher TMAO levels after carnitine challenge tests in human experimental studies;[12, 14] consistently, we identified 6 Clostridium species significantly or nominally associated with higher TMAO concentrations. Of these, C. citroniae, C. asparagiforme, and C. hathewayi are reported by functional/bioinformatic studies to carry cutC/D genes that convert choline to TMA,[15, 17] which interestingly, coincided with our secondary findings on cutC/D gene clusters in these taxa. In addition, among the TMAO-producing bacterial families identified from animal studies,[2] we found 2 species in Erysipelotrichaceae (E. biform and Erysipelotrichaceae bacterium 21 3) and 3 in Lachnospiraceae (including R. hominis) that showed significant or nominal associations with TMAO. Eggerthella lenta is involved in converting L-carnitine to TMA in a functional study,[13] while we identified an unclassed Eggerthella species associated with TMAO levels. Of note, some of our identified species, such as A. shahii, E. biforme, and R. hominis, have not been specifically linked to TMAO in prior studies and therefore require further replications. Despite that our study participants were of old age, our findings on TMAO-predicting species and their interactions with diet in association with TMAO levels were independent of many risk factors including participants’ renal function, HbA1c levels, and obesity status. Taken together, our study verified some previous experimental/bioinformatic findings at the species level and identified novel bacterial species that may be potentially involved in TMAO production in free-living men.

Multiple food sources may contribute to the host’s circulating TMAO pool with or without the involvement of the gut microbiome. A prior feeding study found that chronic red meat intake could lead to a stable increase in plasma and urinary TMAO levels.[7] Our study provides the first evidence that in free-living men, higher intakes of red meat/choline – especially habitual intakes – were associated with increased plasma TMAO levels only among participants carrying abundant microbial species that jointly predict higher TMAO levels. Although dietary intakes of TMAO precursors were associated with multiple bacterial species, we did not find evident overlaps between these species and species associated with TMAO levels, which is likely because our study participants were free of major chronic diseases, and had relatively stable long-term dietary patterns and a relatively stable gut microbiome.[18] Our findings also coincide with prior evidence that omnivores had a more substantial increase in plasma TMAO levels than vegans in response to the carnitine challenge test; and that in both omnivores and vegans, the gut microbial compositions were substantially different between individuals with higher circulating TMAO levels after carnitine challenge tests and those with lower TMAO levels.[12] In contrast to red meat, fish naturally contains TMA/TMAO,[8] and its intake could increase TMAO levels rapidly without microbial metabolism of choline/L-carnitine.[9] Consistently in our study, higher fish intake – especially habitual intakes – was not associated with increased plasma choline/L-carnitine levels, but was significantly associated with increased TMAO levels regardless of the microbial TMAO-producer phenotype. Considering the complex nature of diet in free-living individuals, habitual intakes are more likely to capture long-term between-person variations in diet, thus partially explaining the stronger associations between habitual intakes and TMAO concentrations compared to those of recent intakes. Taken together, circulating TMAO concentrations are dynamically influenced by multiple factors, including complex interactions between intakes of various foods and the gut bacteria.

Limited evidence has linked some of our identified TMAO-predicting species to the host’s cardiometabolic health. For instance, E. hallii was associated with improved insulin sensitivity in animal and human studies.[30, 31] A. shahii and R. hominis were enriched in type 1 diabetes patients[32] but A. shahii was depleted among obese or coronary heart disease patients.[33, 34] However, these cross-sectional studies are prone to reverse causation bias because microbial compositions may change following treatments or diet/lifestyle shifts after diagnosis. In an intervention study, physical activity decreased the abundance of A. shahii in prediabetic men who responded to the intervention.[31] In addition, reduction in A. shahii was correlated with favorable changes in glycemic traits, LDL-C, and inflammation.[31] Of note, TMAO is associated with adverse profiles of glycemic traits[6] and reduced reverse cholesterol transportation.[3] Consistently in our study, A. shahii was significantly associated with higher TMAO levels independently of HbA1c, and its presence strengthened the associations of red meat intake with higher HbA1c and lower HDL-C levels. This evidence suggests that A. shahii may be involved in the metabolism of red meat and its adverse cardiometabolic effects. The lack of interactions between red meat intake and TMAO-producer phenotype on cardiometabolic risk biomarkers, is probably because other abundant TMAO-predicting species showed opposing or null interaction effects in associations with these risk biomarkers. Future studies are required to investigate functions of these TMAO-predicting species.

While the majority of prospective evidence links higher TMAO levels to increased CVD risk, findings from individual studies are conflicting,[4, 35, and 36] possibly because sources of TMAO are different across populations.[37] In addition, although red meat intake is consistently associated with increased CVD and diabetes risk,[38, 39] other foods, especially fish that substantially increases TMAO levels without microbial metabolism, have shown no risk or even benefits.[10, 38, and 40] Of note, in our study, while TMAO was significantly associated with HDL-C and HbA1c levels, it only explains <2% of the total variation of these two biomarkers. Although TMAO-producer phenotype significantly modified the association between red meat intake and TMAO levels, it did not modify associations with risk biomarkers. The interaction between A. shahii and red meat intake on HDL-C and HbA1c levels also showed only minor changes after further adjusting for TMAO levels. Furthermore, within the identified species, functional features associated with TMAO levels were mostly enriched in pathways related to bacteria’s nutrient metabolism and self-maintenance. Therefore, prior and our findings are compatible and collectively suggest the possibility that TMAO may merely serve as a biomarker reflecting the interplay between intakes of some animal foods and the gut microbiota, especially among individuals without regular fish intake. From this perspective, interpretations of associations between TMAO and disease risks require caution and may depend on the study population’s habitual dietary patterns.

The present study, to our knowledge, is the largest investigation that exclusively elucidated microbial species and their interactions with diet in association with circulating TMAO concentrations in free-living individuals. Our study is strengthened by the longitudinal design that comprehensively assessed habitual/recent diets, biomarkers, risk factors, and gut microbiome 2–4 times for each participant within a year. Such a design enabled the evaluation of within person variabilities over time, reduced measurement errors, and allowed the adjustment for many risk factors/confounders including renal function. In particular, repeated measurements are critical for accurately assessing plasma TMAO concentrations, which may substantially fluctuate over time. Despite old age, our participants were largely healthy, thus reducing concerns of reverse causation due to major diseases. The comprehensive shotgun metagenomic and metatranscriptomic data also enabled us to examine well-characterized profiles of taxa and functional features.

Several limitations warrant discussion. First, due to the observational nature, our study cannot conclude that the associations are causal. Despite the use of the longitudinal design, we cannot establish the temporal relationship between TMAO and microbial composition. Second, although we used repeated FFQ and 7DDR assessments to reduce random measurement error, measurement error in diet may still be a concern. Third, while we have adjusted for many confounders in analyses, residual and unmeasured confounding cannot be completely ruled out. Fourth, despite having a larger sample size compared to prior studies, we were still underpowered to detect diet-microbiome interactions for species with low abundance. To ensure sufficient statistical power in interaction analyses, we categorized the TMAO-producer phenotype based on 4 abundant TMAO-predicting species showing high frequencies. Future studies are warranted to examine interactions between diet and low-abundance species. Finally, our study participants are mostly white men at older ages and without any major chronic diseases and therefore, the generalization of our results to women, other racial/ethnic groups, or individuals with different health or demographic profiles is unclear and warrants further validations and investigations.

In conclusion, our study identified gut microbial species that were associated with plasma TMAO concentrations in free-living men. We further showed that a gut microbial TMAO-producer phenotype, as characterized by the identified species, modified the associations between habitual intakes of red meat/choline and plasma TMAO concentrations. In addition, specific species might also interact with red meat intake in associations with cardiometabolic risk factors. Our study underscored the potential role of complex interactions between diet and gut microbiome in producing potentially bioactive metabolites and possibly modulating cardiometabolic risk factors. Identifying functional gut microbiome responses to dietary interventions has the potential to facilitate the development of individualized strategies for more efficient prevention of cardiometabolic diseases.

Supplementary Material

Significance of the study.

What is already known on this subject?

Higher circulating levels of TMAO, a metabolite that can be produced by the gut microbiota from intake of foods rich in choline/L-carnitine (such as red meat), are associated with higher risk of incident cardiovascular events and adverse metabolic health.

Some microbial taxa are linked to TMA production in prior studies through experimental approaches or bioinformatic/biochemistry interrogations, but microbes associated with TMAO concentrations in free-living individuals are not yet elucidated.

A few previous studies have examined gut microbiome and TMAO production through carnitine challenge tests in small groups of human subjects. However, potential interactions between the human gut microbiome and intakes of foods rich in choline/L-carnitine on circulating TMAO concentrations and cardiometabolic risk factors have not been examined.

What are the new findings?

We performed taxonomic and functional profiling of the gut microbiome in a longitudinal study of free-living healthy men using high-throughput shotgun sequencing. We identified 10 microbial species that were significantly associated with plasma TMAO concentrations.

Higher habitual intake of red meat and choline was significantly associated with increased TMAO concentrations only among participants with a microbial profile consisting of abundant species that predicted TMAO concentrations.

The presence of Alistipes shahii significantly strengthened the positive associations of red meat intake with TMAO concentrations, as well as with HbA1c levels.

Secondary analyses identified metagenomic functional features (including gene clusters, enzymes, and functional pathways) that were associated with TMAO concentrations.

How might it impact clinical practice in the foreseeable future?

Our study identified candidate taxa that warrant further investigations in terms of their TMAO-producing capabilities and potential health effects.

Our data highlighted the role of interactions between diet and gut microbiome in producing potentially bioactive metabolites and modulating cardiometabolic risk factors.

The identification of a functional gut microbiome that is responsive to dietary intakes may aid the development of individualized strategies for a more effective prevention of cardiometabolic diseases.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants and staff of the HPFS and MLVS for their participation and work. This study is supported by research grant R01HL035464 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), and DK119268 and DK126698 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). The Men’s Lifestyle Validation Study was supported by U01CA152904 from the National Cancer Institute (NCI). The Health Professionals Follow-Up Study is supported by U01CA167552 from NCI and R01HL35464 from NHLBI. Studies of nutrition and diet in these cohorts are supported by DK120870 from NIDDK and HL060712 from NHLBI. Dr. Jun Li is supported by K99DK122128 from NIDDK and the NIDDK-funded (P30DK046200) Boston Nutrition Obesity Research Center. The funding source had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Abbreviations

- 7DDR

7-day diet record

- AHEI

Alternative healthy eating index

- BMI

Body mass index

- CVD

Cardiovascular disease

- FDR

False discovery rate

- GFR

Glomerular filtration rate

- HbA1c

Hemoglobin A1c

- HDL-C

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- HPFS

Health Professionals Follow-up Study

- hsCRP

High-sensitivity C-reactive protein

- MLVS

Men’s Lifestyle Validation Study

- Pco

Principal coordinate

- PCr

Plasma creatinine

- QC

Quality control

- SD

Standard deviation

- TC

Total cholesterol

- TG

Triglycerides

- TMA

Trimethylamine

- TMAO

Trimethylamine N-oxide

- Ucr

Urinary excretion of creatinine

Footnotes

Competing interests

None.

Ethic approval

The study protocol was approved by the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health Institutional Review Board. All participants provided written informed consent.

Patient and Public Involvement

It was not appropriate or possible to involve participants or the public in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of our research.

Reference

- 1.Valdes AM, Walter J, Segal E, et al. Role of the gut microbiota in nutrition and health. BMJ 2018;361:k2179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown JM, Hazen SL. Microbial modulation of cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Microbiol 2018;16:171–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tang WHW, Backhed F, Landmesser U, et al. Intestinal Microbiota in Cardiovascular Health and Disease: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;73:2089–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heianza Y, Ma W, Manson JE, et al. Gut Microbiota Metabolites and Risk of Major Adverse Cardiovascular Disease Events and Death: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies. J Am Heart Assoc 2017;6:e004947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heianza Y, Ma W, DiDonato JA, et al. Long-Term Changes in Gut Microbial Metabolite Trimethylamine N-Oxide and Coronary Heart Disease Risk. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020;75:763–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heianza Y, Sun D, Li X, et al. Gut microbiota metabolites, amino acid metabolites and improvements in insulin sensitivity and glucose metabolism: the POUNDS Lost trial. Gut 2019;68:263–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Z, Bergeron N, Levison BS, et al. Impact of chronic dietary red meat, white meat, or non-meat protein on trimethylamine N-oxide metabolism and renal excretion in healthy men and women. Eur Heart J 2019;40:583–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seibel BA, Walsh PJ. Trimethylamine oxide accumulation in marine animals: relationship to acylglycerol storagej. J Exp Biol 2002;205:297–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmedes M, Brejnrod AD, Aadland EK, et al. The Effect of Lean-Seafood and Non-Seafood Diets on Fecal Metabolites and Gut Microbiome: Results from a Randomized Crossover Intervention Study. Mol Nutr Food Res 2019;63:1700976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chowdhury R, Stevens S, Gorman D, et al. Association between fish consumption, long chain omega 3 fatty acids, and risk of cerebrovascular disease: systematic review and meta- analysis. BMJ 2012;345:e6698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morrison DJ, Preston T. Formation of short chain fatty acids by the gut microbiota and their impact on human metabolism. Gut Microbes 2016;7:189–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu WK, Chen CC, Liu PY, et al. Identification of TMAO-producer phenotype and host- diet-gut dysbiosis by carnitine challenge test in human and germ-free mice. Gut 2019;68:1439–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koeth RA, Levison BS, Culley MK, et al. gamma-Butyrobetaine is a proatherogenic intermediate in gut microbial metabolism of L-carnitine to TMAO. Cell Metab 2014;20:799–812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koeth RA, Wang Z, Levison BS, et al. Intestinal microbiota metabolism of L-carnitine, a nutrient in red meat, promotes atherosclerosis. Nat Med 2013;19:576–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Romano KA, Vivas EI, Amador-Noguez D, et al. Intestinal microbiota composition modulates choline bioavailability from diet and accumulation of the proatherogenic metabolite trimethylamine-N-oxide. mBio 2015;6:e02481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rath S, Heidrich B, Pieper DH, et al. Uncovering the trimethylamine-producing bacteria of the human gut microbiota. Microbiome 2017;5:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martinez-del Campo A, Bodea S, Hamer HA, et al. Characterization and detection of a widely distributed gene cluster that predicts anaerobic choline utilization by human gut bacteria. MBio 2015;6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mehta RS, Abu-Ali GS, Drew DA, et al. Stability of the human faecal microbiome in a cohort of adult men. Nat Microbiol 2018;3:347–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abu-Ali GS, Mehta RS, Lloyd-Price J, et al. Metatranscriptome of human faecal microbial communities in a cohort of adult men. Nat Microbiol 2018;3:356–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Al-Shaar L, Yuan C, Rosner B, et al. Reproducibility and Validity of a Semi-quantitative Food Frequency Questionnaire in Men Assessed by Multiple Methods. Am J Epidemiol 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chiuve SE, Fung TT, Rimm EB, et al. Alternative Dietary Indices Both Strongly Predict Risk of Chronic Disease. J Nutr 2012;142:1009–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Z, Levison BS, Hazen JE, et al. Measurement of trimethylamine-N-oxide by stable isotope dilution liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Biochem 2014;455:35–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Truong DT, Franzosa EA, Tickle TL, et al. MetaPhlAn2 for enhanced metagenomic taxonomic profiling. Nat Methods 2015;12:902–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abubucker S, Segata N, Goll J, et al. Metabolic Reconstruction for Metagenomic Data and Its Application to the Human Microbiome. PLoS Comput Biol 2012;8:e1002358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Acker BA, Koomen GC, Koopman MG, et al. Creatinine clearance during cimetidine administration for measurement of glomerular filtration rate. Lancet 1992;340:1326–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.2. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2018. Diabetes Care 2018;41:S13–S27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li J, Rice MS, Huang T, et al. Circulating prolactin concentrations and risk of type 2 diabetes in US women. Diabetologia 2018;61:2549–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stubbs JR, House JA, Ocque AJ, et al. Serum Trimethylamine-N-Oxide is Elevated in CKD and Correlates with Coronary Atherosclerosis Burden. J Am Soc Nephrol 2016;27:305–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cho CE, Taesuwan S, Malysheva OV, et al. Trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO) response to animal source foods varies among healthy young men and is influenced by their gut microbiota composition: A randomized controlled trial. Mol Nutr Food Res 2017;61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Udayappan S, Manneras-Holm L, Chaplin-Scott A, et al. Oral treatment with Eubacterium hallii improves insulin sensitivity in db/db mice. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2016;2:16009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu Y, Wang Y, Ni Y, et al. Gut Microbiome Fermentation Determines the Efficacy of Exercise for Diabetes Prevention. Cell Metab 2020;31:77–91.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Siljander H, Honkanen J, Knip M. Microbiome and type 1 diabetes. EBioMedicine 2019;46:512–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thingholm LB, Rühlemann MC, Koch M, et al. Obese Individuals with and without Type 2 Diabetes Show Different Gut Microbial Functional Capacity and Composition. Cell Host Microbe 2019;26:252–64.e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jie Z, Xia H, Zhong SL, et al. The gut microbiome in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Nat Commun 2017;8:845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Qi J, You T, Li J, et al. Circulating trimethylamine N-oxide and the risk of cardiovascular diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 11 prospective cohort studies. J Cell Mol Med 2018;22:185–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu G, Li J, Li Y, et al. Gut microbiota–derived metabolites and risk of coronary artery disease: a prospective study among US men and women. Am J Clin Nutr 2021; nqab053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Janeiro MH, Ramírez MJ, Milagro FI, et al. Implication of Trimethylamine N-Oxide (TMAO) in Disease: Potential Biomarker or New Therapeutic Target. Nutrients 2018;10:1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Key TJ, Appleby PN, Bradbury KE, et al. Consumption of Meat, Fish, Dairy Products, and Eggs and Risk of Ischemic Heart Disease. Circulation 2019;139:2835–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Micha R, Wallace SK, Mozaffarian D. Red and Processed Meat Consumption and Risk of Incident Coronary Heart Disease, Stroke, and Diabetes Mellitus. Circulation 2010;121:2271–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shin JY, Xun P, Nakamura Y, et al. Egg consumption in relation to risk of cardiovascular disease and diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr 2013;98:146–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.