Abstract

Synapses in the outer retina are the first information relay points in vision. Here, photoreceptors form synapses onto two types of interneurons, bipolar cells and horizontal cells. Because outer retina synapses are particularly large and highly ordered, they have been a useful system for the discovery of mechanisms underlying synapse specificity and maintenance. Understanding these processes is critical to efforts aimed at restoring visual function through repairing or replacing neurons and promoting their connectivity. We review outer retina neuron synapse architecture, neural migration modes, and the cellular and molecular pathways that play key roles in the development and maintenance of these connections. We further discuss how these mechanisms may impact connectivity in the retina.

Keywords: retina, synapse, outer plexiform layer, horizontal cell, photoreceptor, bipolar cell, ribbon

Overview

Each of the billions of neurons in the central nervous system (CNS) face the monumental challenge of guiding their axons and dendrites to the correct location and initiating proper synapse formation. The accuracy and robustness of these connections is essential for all human behavior. Circuit formation begins during development when neurons migrate to their final laminar position and first choose their synaptic partners. These connections are then modified through a process called synaptic refinement in which excess synapses are removed, ultimately leading to adult patterns of connectivity. In turn, adult synapses must be maintained in order to prevent CNS functional decline. In this review, we discuss the processes and pathways that underlie neuron migration and the formation and maintenance of vision’s first synapse. This connection occurs in the outer retina and consists of synapses between presynaptic photoreceptors and their postsynaptic partners, bipolar and horizontal cells. The outer retina has proven to be an invaluable region for studies of synapse modifying pathways for several reasons. First, all outer retina types have been identified and their organization and connectivity have largely been mapped (Sanes and Zipursky, 2010; Shekhar et al., 2016; Behrens et al., 2016). Second, outer retina synapses are relatively large, occur only at one distal location, and form between a limited number of neuron types. This greatly facilitates the identification of synapse defects in development and disease models. Finally, each contributing neuron type can be readily manipulated and identified in vivo allowing interrogation of the contribution of specific neuronal subsets to connectivity (Sarin et al., 2018; Matsuda and Cepko, 2004). In addition, many blinding diseases involve degeneration of outer retina neurons and their connections. Thus, if we are to meaningfully restore vision, we must understand how outer retina circuit assembly and specificity is determined. In this review, we outline the cellular and molecular features of outer retina synapses, highlight neuron-specific migration modes, discuss the molecular pathways that play key roles in forming and stabilizing these connections, and consider how these mechanisms may impact connectivity more broadly.

Outer retina neuron subtypes and connectivity

Outer retina neuron organization and function

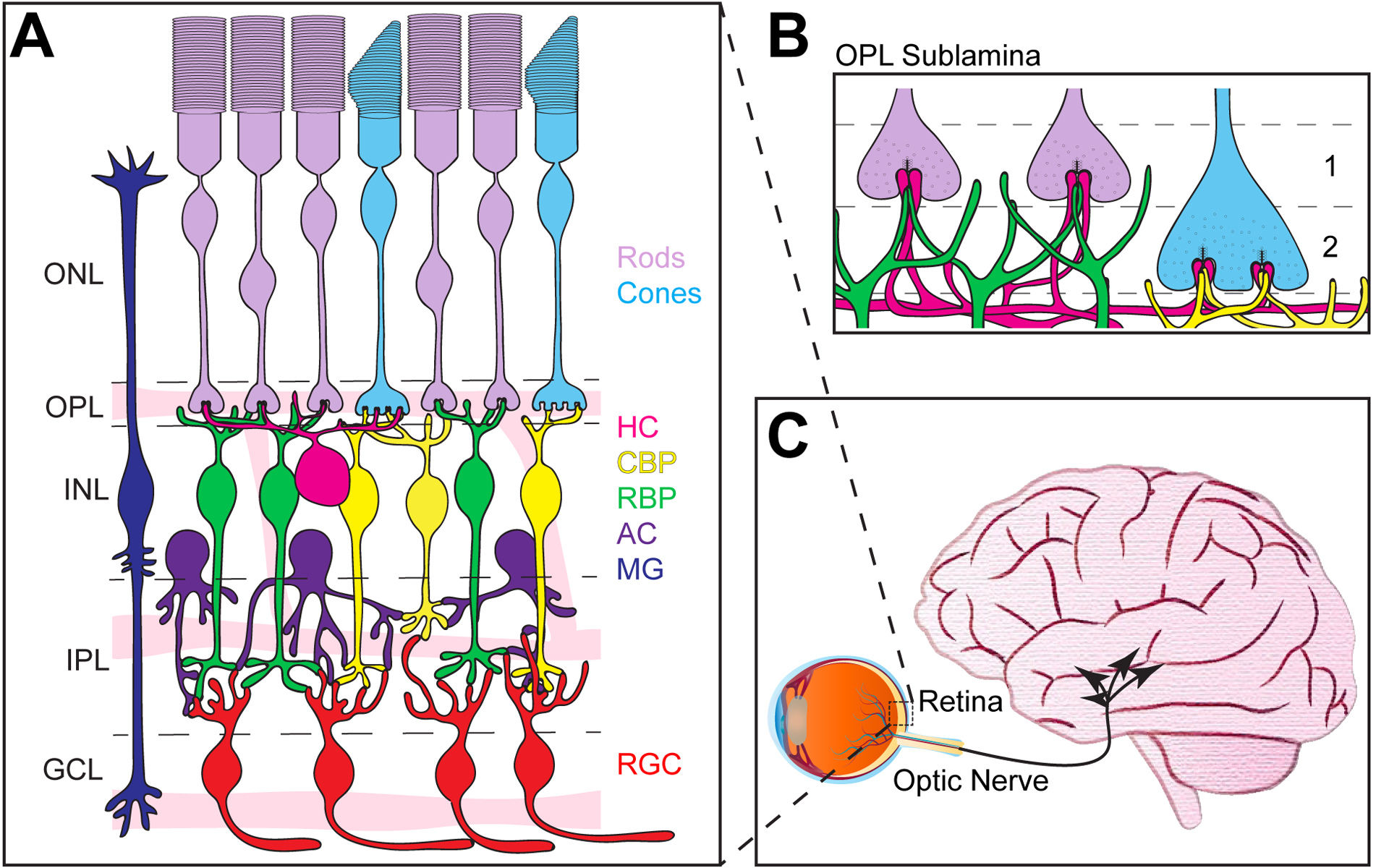

Synapses in the outer retina are formed by just four general neuron types: rods, cones, horizontal cells, and bipolar cells (Figure 1A). Rod and cone photoreceptors are found in the outer nuclear layer (ONL). These cells detect light and convert these photons into an electrical signal that is relayed to horizontal and bipolar cells found in the inner nuclear layer (INL). Synapses between these four cell types comprise a thin band termed the outer plexiform layer (OPL) which contains two synaptic sublamina, one for cone synapses and one for rod synapses (Figure 1B). Visual information is then propagated through the inner retina and sent via retinal ganglion cell axons to the brain (Figure 1C).

Figure 1. Structure of the retina.

A. Schematic of outer retina neuron organization in adults. The outer nuclear layer (ONL) contains rods (purple) and cones (blue) that form connections in the outer plexiform layer (OPL) with rod bipolar cells (RBP, green), cone bipolar cells (CBP, yellow), and horizontal cells (HC, magenta) found in the inner nuclear layer (INL). Also present in the INL are amacrine cells (AC, dark purple) that form connections in the inner plexiform layer (IPL) together with bipolar cell axons onto retinal ganglion cells (RGC, red) whose cell bodies reside in the ganglion cell layer (GCL). Müller glia (MG, dark blue) span the length of the outer retina. Three intraretina vascular layers also interdigitate the GCL, IPL, and OPL and are termed the superficial, intermediate, and deep vasculature layers, respectively. B. The OPL contains two sublamina. Rod spherules form the apical sublamina (1), while cone pedicles sit just beneath rod spherules and form the basal sublamina (2). C. Axons from ganglion cells form the optic nerve, which projects to multiple (~50) retinorecipient areas in the brain.

Each outer retina neuron population varies according to its function, subtype diversity, and species. Rods respond to dim light and are responsible for night vision, while cones respond to brighter light and are responsible for daylight vision and color detection (Ingram et al., 2016). While there appears to be only one type of rod photoreceptor in most organisms, different cone subtypes are present that detect distinct light wavelengths in various species. For example, humans have three cone subtypes (long-wave, OPN1LW; middle-wave, OPN1MW; and short-wave, OPN1SW) and mice have two (OPN1SW and OPN1MW), while species such as mantis shrimp have up to 33 opsin transcripts (N. oerstedii, Porter et al., 2020; Szét et al., 1992; Nathans et al., 1986). Notably, light activation of photoreceptors leads to hyperpolarization rather than depolarization, and the biochemical steps that underlie photoreceptor signaling have been well characterized. (Tsin et al., 2018; Choe et al., 2001; Siebert et al.,1995; Palczewski, 2014). The phototransduction cascade involves isomerization of retinal causing a conformational change in rhodopsin. This leads to the sequential activation of transducin and phosphodiesterase, resulting in the closure of cGMP-gated cation channels. This signaling culminates in reduced release of glutamate onto bipolar cells and horizontal cells. Horizontal cells provide inhibitory feedback to this circuit (Wu, 1992; Kaneko and Tachibana, 1986; Tatsukawa et al., 2005; Fahrenfort et al., 2005; Barnes et al., 1993; Liu et al., 2013a), while bipolar cells feed forward information to ganglion cells and segregate inputs into ON and OFF responses according to the type of glutamate receptors expressed on their dendrites (Figure 2A; Puller et al., 2013; DeVries, 2000; Lindstrom et al., 2014).

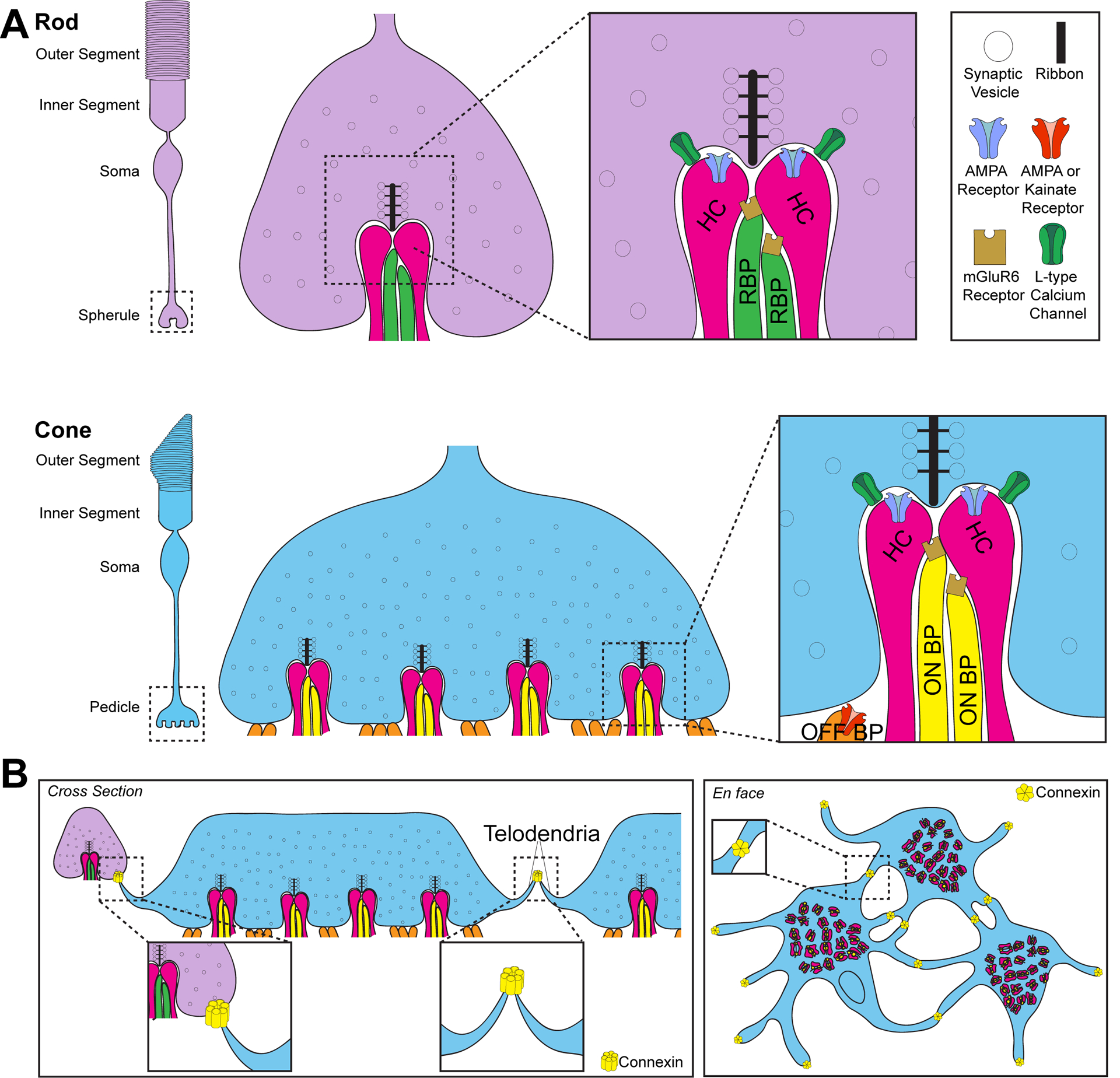

Figure 2. Axon terminal architecture of photoreceptors.

A. Rod (purple) and cone (blue) photoreceptors are comprised of four general regions: the outer segment, inner segment, soma, and axon terminal. The terminal region is termed the spherule in rods and pedicle in cones. Photoreceptors contain ribbon synapses which hold vesicles close to the active zone for rapid neurotransmitter release. The mature rod synapse contains one ribbon and a corresponding postsynaptic invagination by two lateral horizontal cell (HC; pink) neurites that are regulated by ionotropic AMPA receptors and two or more rod bipolar cells (RBP; green) that contain metabotropic mGluR6 receptors. OFF-cone bipolar cells can also form contacts on the rod spherule. Cone pedicles contain between 20 and 50 sites of invagination. Each invagination contains two lateral horizontal cell neurites that are regulated by ionotropic AMPA receptors and one or more central metabotropic mGluR6 ON-cone bipolar cell (ON BP; yellow) dendrites. Cones also receive flat contacts on the base of the pedicle made by OFF-cone bipolar cells (OFF BP; orange) that are regulated by ionotropic AMPA or Kainate glutamate receptors. Rod bipolar cells can also form contacts on the cone pedicle. B. Electrical signals can also propagate through photoreceptors via gap junctions formed by connexin 36 in mice. These contact sites occur on the tips of telondendria that connect cones to cones and cones to rods. The connexin that electrically couples rods to rods is unknown. Gap junction contacts are pictured in cross section (left panel) and en face (right panel).

Postsynaptic horizontal and bipolar cell neuron subtypes vary as well. One horizontal cell type is present in mice, monkeys have two subtypes, and humans have three (Kolb et al., 1992; Wässle et al., 2000; Hendrickson et al., 2007, Chan et al., 1997). Horizontal cells structurally segregate their connectivity, such that axons form connections with rods while dendrites synapse with cones (Kolb, 1970; Kolb, 1974; Boycott et al., 1987; Peichl and González-Soriano, 1994). Functionally, horizontal cells contribute to contrast enhancement and color opponency (Chapot et al., 2017; VanLeeuwen et al., 2009; Packer et al., 2010). They also provide inhibitory feedback and can impact retinal output as depletion of horizontal cells impairs ganglion cell ON/OFF direction selectivity and spatial frequency (Chaya et al., 2017; Wu, 1992; Kaneko and Tachibana, 1986; Tatsukawa et al., 2005). Fifteen bipolar cell subtypes have been identified in mice. These include a single rod bipolar cell subtype, which primarily connects to rods, and 14 cone bipolar cell subtypes, which primarily connect with cones (Shekhar et al., 2016; Ghosh et al., 2004; Wässle et al., 2009). Bipolar cell subtypes are classified based on their morphology and on their axon stratification in the inner plexiform layer (IPL; Ghosh et al., 2004). Outer IPL targeting bipolar cells include types 1a, 1b, 2, 3a, 3b, and 4b while inner IPL targeting bipolar cells include types 5a, 5b, 5c, 5d, 6, 7, 8, 9 and rod bipolar cells (Tsukamoto and Omi, 2017). This diverse morphology results in an array of bipolar cell functions. For example, rod-driven visual signaling is mediated by rod bipolar cells and type-3 and type-4 OFF cone bipolar cells (Mataruga et al., 2007; Haverkamp et al., 2008). Type-1 and type-9 bipolar cells contribute to dichromatic cone-driven color vision (Haverkamp et al., 2005; Breuninger et al., 2011). The distinct features and functions of these cell subtypes have been extensively reviewed elsewhere (Euler et al., 2014; Poché et al., 2009).

Features of outer retina synapses

Photoreceptor cells are elongated and consist of four general regions: the outer segment, the inner segment, the cell body, and the axon terminal. Each cell forms synapses only on the terminal, which is contacted by invaginating horizontal cell and bipolar cell processes. These contacts are termed spherules in rods and pedicles in cones (Figure 2). The mature rod synapse consists of two lateral AMPA receptor-positive horizontal cell axons and two or more mGluR6 receptor-positive rod bipolar cell dendrites (Sterling and Matthews, 2005; tom Dieck and Brandstatter, 2006). The mature cone synapse consists of two lateral AMPA-positive horizontal cell dendrites, one or more central mGluR6-positive ON bipolar cell dendrites, and flat OFF bipolar cell contacts (Figure 2A; Haverkamp et al., 2000; Vardi et al., 1998; Haverkamp et al., 2001). Each cone is contacted by at least 10 different bipolar cells (Wässle et al., 2009). Furthermore, cone pedicles contain between 20 and 50 sites of invagination, while rod spherules contain just one (Figure 2; Dowling and Boycott, 1966; Chun et al., 1996; Missoten, 1965). Non-conventional partnering between presynaptic photoreceptors and postsynaptic interneurons also occurs. Rod bipolar cell dendrites can form invaginating or superficial contacts with cones, while OFF cone bipolar cells can form flat contacts on rod spherules (Pang et al., 2018; Hack et al., 1999; Haverkamp et al., 2008; Tsukamoto and Omi, 2014). Not only can signals propagate across the retina between pre and postsynaptic partners, but electrical signals can also pass between rods and cones through gap junctions that form both heterologous and homologous electrical synapses (Figure 2B; Baylor et al., 1971; Raviola and Gilula, 1973; Custer, 1973; Copenhagen and Owen, 1976; DeVries et al., 2002; Hornstein et al., 2005; Hornstein et al., 2004; Li et al., 2012). Telodendria connect cones to cones and cones to rods through connexin36 (mouse) or connexin35 (zebrafish) positive gap junctions (Feigenspan et al., 2004; Kántor et al., 2016; O’Brien et al., 2012; Li et al., 2009; Zhang and Wu, 2004). Gap junctions also form between rod spherules but the connexin(s) involved are unknown (Lee et al., 2003; Asteriti et al., 2017; Asteriti et al., 2014; Jin et al., 2020).

Photoreceptor terminals form a specialized synapse structure termed the ribbon synapse (Figure 3, Carter-Dawson and LaVail, 1979; Sterling and Matthews, 2005). These specialized synapses begin as precursor spheres, followed by the appearance of floating, immature ribbons that then develop into anchored, mature ribbons (Regus-Leidig et al., 2009). Mature ribbon structures contain a synaptic ribbon that holds vesicles close to the active zone to allow for rapid neurotransmitter release. For example, a rod spherule contains one ribbon that provides a docking site for ~130 vesicles and a tethered pool of ~640 vesicles, while a single cone pedicle contains multiple ribbons that dock ~600 vesicles and tether ~3000 (Sterling and Matthews, 2005). These electron-dense regions of aligned synaptic vesicles are the ultrastructural hallmark of ribbon synapses (Rao-Mirotznik et al., 1995; Lenzi and von Gersdorff, 2001; Sterling and Matthews, 2005). It is likely that the docked vesicles are primed for rapid release, while the remaining vesicles tethered to the ribbon constitute a slower releasable pool.

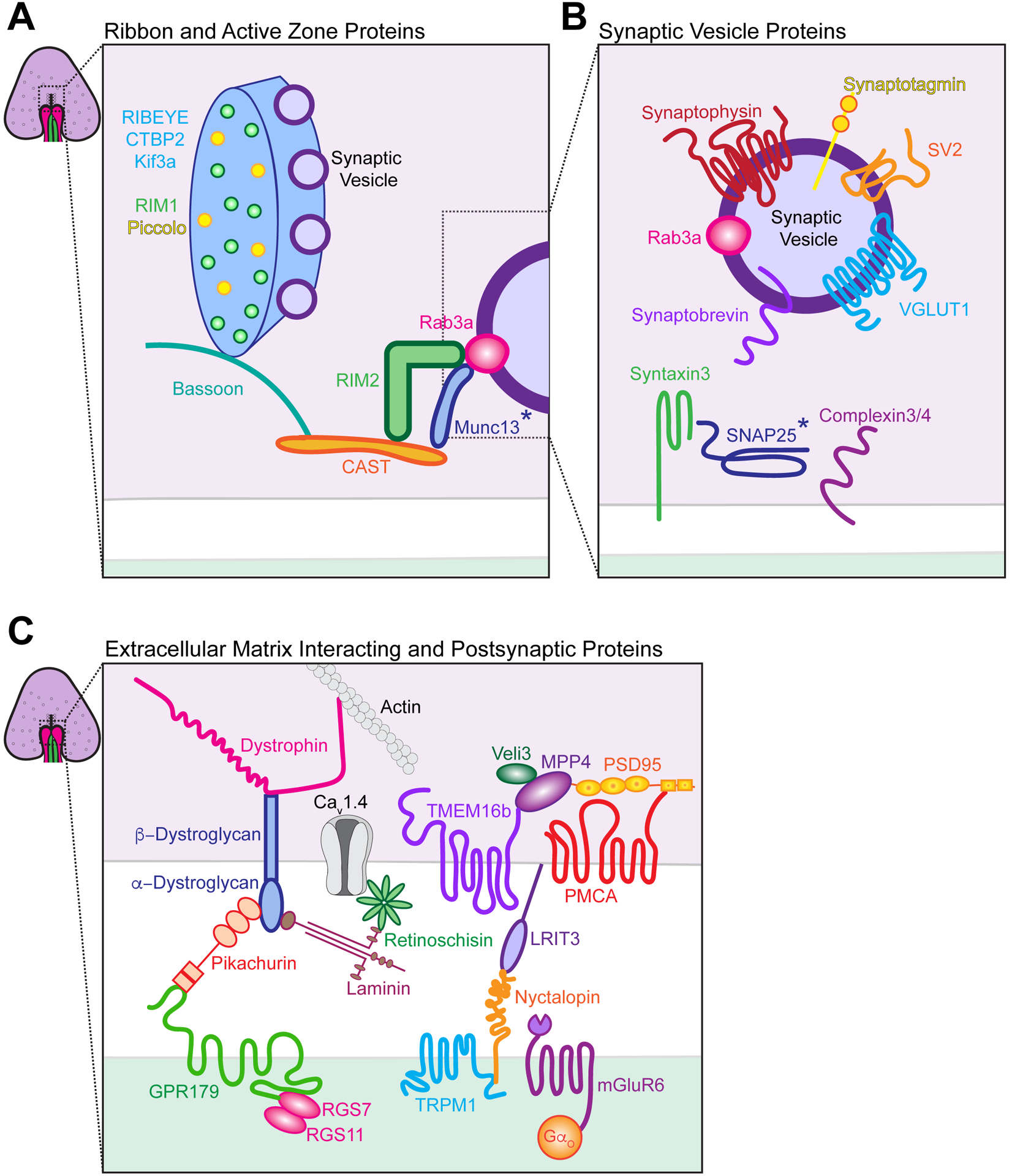

Figure 3. Proteins found at the photoreceptor synapse.

A. Schematic of proteins associated with rod photoreceptor synaptic ribbons and the active zone. RIBEYE is the primary protein of the ribbon, and Kif3a, RIM1, and piccolo also associate with this structure. Bassoon and CAST are localized beneath the ribbon at the active zone and are scaffolding proteins that interact with RIM2, which enhances calcium channel activity. RIM weakly interacts with Rab3a, a vesicle-associated GTPase that regulates vesicle exocytosis, and Munc13. B. Schematic of proteins associated with synaptic vesicles. SNARE proteins are present, including synaptobrevin (V-Snare) and syntaxin3 (T-Snare), while SNAP25 has also been variously reported. Complexin 3 and 4 bind to SNARE complexes to promote vesicle docking. VGLUT1 is a vesicular glutamate transporter, SV2 regulates neurotransmitter release at terminals, and synaptotagmin1 is predicted to be a calcium sensor. C. Schematic of proteins that interact with the extracellular matrix (ECM) and those found at postsynaptic sites. Dystrophin is a cytoskeletal protein that interacts with actin and the dystroglycan beta subunit, while the dystroglycan alpha subunit binds laminin and the retina-specific protein pikachurin. Laminin is a glycoprotein found in the ECM that interacts with the retina specific protein retinoschisin, which in turn regulates calcium channels. Pikachurin is required to connect photoreceptors to ON-bipolar cells via binding to GPR179 on the postsynaptic membrane. GPR179 interacts with regulator of G-protein signaling (RGS) 7 and RGS9. MPP4 is also present in presynaptic photoreceptors and recruits PSD95 and Veli3 to the photoreceptor synapse. In turn, these proteins interact with the calcium-dependent chloride channel TMEM16b and plasma membrane calcium ATPase PMCA. mGluR6 is present on the postsynaptic membrane. Binding of glutamate to mGluR6 activates the G protein Go, which leads to closure of the constitutively active nonselective cation channel transient receptor potential melastatin 1 (TRPM1). Nyctalopin is required for TRPM1, mGluR6, and GPR179 localization by binding to LRIT3 on the presynaptic membrane. Asterisk (*) denotes protein localization at conventional ribbon synapses.

Distinct groups of pre and postsynaptic proteins participate in synapse function in the outer retina. On the presynaptic side, active zone cytomatrix proteins (CAZ), synaptic vesicle proteins, and extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins all play a role in the OPL (Figure 3 and Table 1). We detail each category of these proteins with regard to photoreceptor synapses in turn. CAZ proteins can be further categorized into ribbon-associated proteins or active zone proteins (Figure 3A). Among these, RIBEYE is the primary protein unique to ribbon synapses and is essential to ribbon formation (Maxeiner et al., 2016). RIBEYE interacts with other ribbon-related proteins, including bassoon, piccolo, CAST, Kif3A, Unc119, and Rab3-interacting molecules (RIM) proteins (Regus-Leidig et al., 2009, Muresan et al., 1999; Schmitz et al., 2000; Magupalli et al., 2008; tom Dieck et al., 2005; Alpadi et al., 2008). While the exact function of many of these ribbon-associated proteins is still unclear, some progress has been made. For example, Kif3a may aid in synaptic vesicle transport to the active zone (Marszalek et al., 2000; Jimeno et al., 2006). RIM proteins help regulate calcium channel activity but not vesicle priming and docking (Deguchi-Tawarda et al., 2006; Grabner et al., 2015; Grassmeyer et al., 2019; Hibino et al., 2002; Dembla et al., 2020). As expected, loss of ribbon and active zone organizers compromise neurotransmission from presynaptic terminals. Bassoon mutants have detached ribbons and impaired vesicle docking (Dick et al., 2003; tom Dieck et al., 2005), while mutants of the piccolo isoform piccolino display spherical instead of flat ribbons (Regus-Leidig et al., 2014).

Table 1:

Proteins found at the ribbon synapse.

| Protein Component | Function at Conventional Synapses | Function at Photoreceptor Ribbon Synapses | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ribbon-Associated Proteins | |||

| RIBEYE |

|

|

|

| KIF3a |

|

|

|

| RIM1 |

|

|

|

| Piccolino |

|

|

|

| Active Zone Proteins | |||

| Bassoon |

|

|

|

| RIM2 |

|

|

|

| Munc13 |

|

|

|

| ELKS |

|

|

|

| Unc119 |

|

|

|

| CAST |

|

|

|

| Synaptic Vesicle Proteins | |||

| VGLUT1 |

|

|

|

| VGLUT2 |

|

|

|

| Rab3a |

|

|

|

| SNAP25 |

|

|

|

| Synaptobrevin |

|

|

|

| Syntaxin3 |

|

|

|

| Complexin 3/4 |

|

|

|

| Synaptotagmin1 |

|

|

|

| SV2 |

|

|

|

| Synaptophysin |

|

|

|

| ECM Interacting proteins | |||

| Dystrophin |

|

|

|

| Dystroglycan |

|

|

|

| Pikachurin | N/A |

|

|

| PMCA |

|

|

|

| PSD95 |

|

|

|

| CRB |

|

|

|

| Retinoschisin | N/A |

|

|

| TMEM16B |

|

|

|

| Laminin |

|

|

|

| MPP4 | N/A |

|

|

Synaptic vesicle formation and release proteins also play important roles in outer retina synapses (Figure 3B). At chemical synapses, depolarization of neurons results in a calcium influx that causes vesicle fusion and neurotransmitter release though well-described synapse machinery that includes the SNARE complexes. The retina employs unique vesicle release machinery that includes Syntaxin 3 and SNARE complex assemblers complexin 3 and 4 (Ullrich and Südhof, 1994; Brandstätter et al., 1996; Morgans et al., 1996; Curtis et al., 2008; Reim et al., 2005; Zanazzi and Matthews, 2010). Vesicular glutamate transporters (VGLUT1) and synaptic vesicle proteins (SV) are also present on synaptic vesicles in the outer retina. VGLUTs load glutamate into synaptic vesicles, and among these VGLUT1 appears specific to photoreceptor terminals (Burger et al., 2020; Fremeau et al., 2002; Fremeau et al., 2001; Sherry et al., 2003; Johnson et al., 2007). SV2 is also present at photoreceptor synapses and plays an important role in calcium regulation of neurotransmitter release (Buckley and Kelly, 1985; Morgans et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2003). Finally, calcium sensor molecules also regulate exocytosis, and Synaptotagmin1 has been proposed to play this role in the OPL (Grassmeyer et al., 2019; Fox and Sanes, 2007; Greenlee et al., 1996; Bernston and Morgans, 2003; Heidelberger et al., 2003).

ECM interacting proteins (Figure 3C), such as dystrophin, also play documented roles in the OPL. (Pillers et al., 1993; Schmitz and Drenckhahn, 1997a). Dystrophin is part of the spectrin family and interacts with actin filaments, β-dystroglycan, and pikachurin, the latter of which is critical for the formation of contacts between photoreceptors and ON-bipolar cells (Schmitz and Drenckhahn, 1997b; Schmitz et al., 1993; Sato et al., 2008). Other ECM proteins important to OPL organization include laminins and Retinoschisin, a secreted OPL matrix protein known to interact with calcium channels (Molday et al., 2007; Shi et al., 2009; Shi et al., 2017). Postsynaptic density protein 95 (PSD95) is also found at the outer retina synapse. While PSD95 is postsynaptic in many (but not all) brain regions it is presynaptic in the OPL (Koulen et al., 1998; Kistner et al., 1993; Laube et al., 1996; Hunt et al., 1996). PSD95 contains PDZ domains that can interact with Crumbs-related protein (CRB) and TMEM16B, a calcium-activated chloride channel (Aartsen et al., 2006; Stöhr et al., 2009). CRB is a key regulator of cell polarity, and defects in Crumb genes can lead to retina diseases (e.g. Leber’s congenital amaurosis and retinitis pigmentosa, den Hollander et al., 1999; Lotery et al., 2001).

Less is known regarding postsynaptic protein distribution (Figure 3C). AMPA or kainate receptors are present on the dendrites of OFF bipolar cells while metabotropic glutamate receptor mGluR6 is present on rod and cone ON bipolar cells (Figure 2A, Nomura et al., 1994; Peng et al., 1995; Brandstätter et al., 1998; Koulen et al., 1996). Proteins associated with mGluR6 have been best defined. Binding of glutamate to mGluR6 activates the G protein Go, which leads to closure of the constitutively active nonselective cation channel transient receptor potential melastatin 1 (TRPM1). TRPM1−/−, mGluR6−/−, and Go−/− mice do not respond to light which is evidenced by loss of the electroretinogram (ERG) b-wave (Shen et al., 2009; Koike et al., 2010; Koyasu et al., 2008; Masu et al., 1995; Dhingra et al., 2000; Xu et al., 2012). Furthermore, binding of TRPM1 to ON bipolar cell dendrites requires mGluR6, the synaptic protein nyctalopin, and LRIT3 (Hasan et al., 2019; Hasan et al., 2020; Koike et al., 2010; Xu et al., 2012; Cao et al., 2011; Pearring et al., 2011). Finally, pikachurin is connected to the postsynaptic element GPR179, which is required for the expression of regulator of G protein signaling (RGS) 7 and RGS11 (Orlandi et al., 2018). These genes are part of the GTPase Activating Protein (GAP) complex that activates Go in ON bipolar cells (Sarria et al., 2016). While these and several other proteins have been identified at pre and postsynaptic OPL synapses, it is less certain how each contributes to neurotransmission. Ribbon shape can also vary widely across OPL synapses (Li et al., 2016), and the pathways that regulate this variation are unknown, as are those that regulate multi-vesicle binding, transport, and release at presynaptic sites.

Anatomical characterization of outer retina development

Outer retina neuron migration

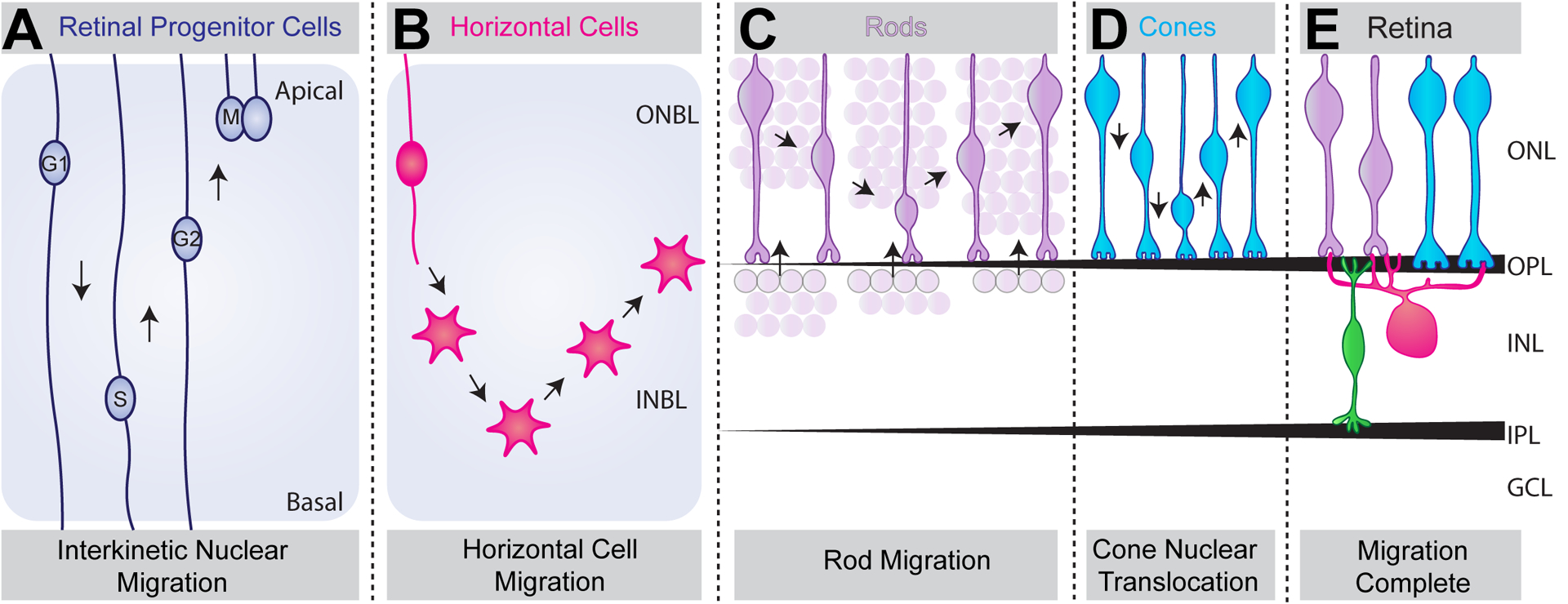

In order to correctly form the intricate synapse structures described above, both pre and postsynaptic outer retina neurons must arrive at the right location at the right time. All retina neurons are derived from retinal progenitor cells (RPC). In mice, cones and horizontal cells are born during embryogenesis (E12-E17; Carter-Dawson and LaVail, 1979; Young, 1984). Rod neurogenesis begins ~E14 but peaks shortly after birth, while bipolar cell birth peaks in the first week of postnatal development (Carter-Dawson and LaVail, 1979; Young, 1984). Mechanisms that enable diverse RPC fates have been nicely reviewed elsewhere so we do not detail them here (Cepko et al., 1996; Brzezinski and Reh, 2015; Cepko, 2014). The cellular and molecular pathways that control outer retina neuron location are less clear. Two types of neural movements contribute to the nuclear placement of outer retina neurons: interkinetic nuclear migration (INM) and postmitotic nuclear movements. INM describes the movement of progenitor cells, including those in retina, in phase with the cell cycle and is a conserved feature in multiple species and tissues (Spear and Erickson, 2012). Cells move in the basal direction during G1 and in the apical direction during G2, while M phase occurs at the apical surface and S phase occurs more basally (Figure 4A). Studies in zebrafish and mouse have found that apical INM movement is rapid and continuous, while basal movement is slow, stochastic, and discontinuous (Leung et al., 2011; Kosodo et al., 2011; Tsai et al., 2010; Barraso et al., 2018). Perhaps this difference in nuclear dynamics can be explained by the diverse motor proteins that enable this process. Apical nuclear movement is guided by dynein, while basal movement is directed by slower kinesins such as Kif1a (Hu et al., 2013; Tsai et al., 2010). Specific regulators of retinal INM have also been identified, including MyosinII and SUN/KASH proteins (Table 2; Norden et al., 2009; Schenk et al., 2009; Yu et al., 2011).

Figure 4. Migration of outer retina neurons.

A. Schematic of retinal progenitor cells show that they undergo interkinetic nuclear migration (INM). In this form of movement, nuclei move in apical and basal directions in phase with the cell cycle. B-E. Schematic of fate committed retina neuron subtypes show that retinal neurons exhibit unique migration modes to reach their final laminar position. Horizontal cells (magenta) undergo a bipolar migration phase beginning in the outer neuroblast layer (ONBL), bypassing their final position and descending further into the inner neuroblast layer (INBL), where they switch to a multipolar migration phase (B). They then migrate apically to reach the outer retina where they then fine-tune their final position at the apical side of the future INL. It is presumed that rods (purple) undergo two migration phases (C). From P5 to P8, rods are present at the apical surface of the INL and are thought to migrate apically. During this time, the ONL increases in thickness as the INL decreases in thickness. It is also likely that rods apically and basally migrate within the ONL, as knockout and overexpression studies of CasZ1 results in preferential bias of rods to the apical or basal surface of the ONL. However, when this migration occurs is unknown. Finally, cones (blue) undergo nuclear translocation and move in apical and basal directions from P4 to P12 (D). Together, these neuron subtype specific movements result in proper nuclear lamination in adult retina (E).

Table 2:

Genes involved in outer retina neuron migration.

| Gene | Gene Function | Cell Type | Migration Phenotype | Species | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Syne2 (Nesprin2) | Contains KASH domain and interacts with Sun proteins to form Linkers of the Nucleoskeleton to the Cytoskeleton (LINC) complexes. | Retinal progenitor cell (RPC) interkinetic nuclear migration |

|

|

|

| Rods |

|

|

|||

| Cones |

|

|

|||

| Mikre oko (mok) | Encodes dynactin1, a regulator of dynein. | RPC-interkinetic nuclear migration |

|

|

|

| Photoreceptors |

|

|

|||

| Myosin II | Actin-associated motor protein. | RPC-interkinetic nuclear migration |

|

|

|

| Perplexed | Encodes Cad, an enzyme involved in pyrimidine synthesis. | RPC-interkinetic nuclear migration |

|

|

|

| Disarrayed | N/A | RPC-interkinetic nuclear migration |

|

|

|

| aPKC | Regulates apical-basal cell polarity. | RPC-interkinetic nuclear migration |

|

|

|

| Casz1 | Zinc finger transcription factor. | Rods |

|

|

|

| Rnf2 | Polycomb repressor complex protein. | Rods |

|

|

|

| Lamin A | Intermediate filament protein. | Rods |

|

|

|

| Klarsicht | Protein that localizes to the nuclear membrane and contains N-terminal KASH domain. | Photoreceptors |

|

|

|

| Glued | Encodes dynactin, a regulator of dynein. | Photoreceptors |

|

|

|

| Lam Dm 0 | Encodes intermediate filament type B nuclear lamin. | Photoreceptors |

|

|

|

| Sun1 | Sun protein that interacts with Nesprin proteins to form Linkers of the Nucleoskeleton to the Cytoskeleton (LINC) complexes. | Rods |

|

|

|

| Cones |

|

|

|||

| LKB1 | Serine threonine kinase. | Rods |

|

|

|

| Cones |

|

|

|||

| AMPK | Energy sensing kinase downstream of LKB1. | Cones |

|

|

|

| Lim1 | LIM class homeodomain transcription factor. | Horizontal Cells |

|

|

Why might nuclei move in phase with the cell cycle? Three models have been proposed. In the first, INM is suggested to increase progenitor cell packing to allow more progenitor cells to attach to the apical surface (Miyata et al., 2007). In the second, INM has been proposed to regulate neurogenesis. Data support this idea, as premature cell cycle exit can disrupt neuron lamination and increase the number of early-born neurons at the expense of late-born neurons (Ohnuma et al., 2002; Calegari and Huttner, 2003). In addition, zebrafish disarrayed mutants display an extended cell cycle period that leads to a reduction in cell cycle exit and decreased neurogenesis (Baye and Link, 2007a). Finally, INM may be important for temporally exposing cells to Notch signaling, which is highly expressed in the apical neuroepithelium and has been shown to delay neurogenesis (Del Bene et al., 2008; Furukawa et al., 2000; Gaiano et al., 2000; Morrison et al., 2000; You et al., 2019). It is clear from these data that regardless of the mechanism involved, INM plays a critical role in producing the right number of cells of the correct type.

Once neuronal precursor cells exit the cell cycle, postmitotic nuclear movements lead them to their final cell position (Figure 4B–E). Each presynaptic and postsynaptic outer retina neuron type occupies spatially distinct retina regions. For example, rods are positioned throughout the ONL while cones are located only in the apical ONL. How might this difference arise? Recent advances in retinal cultures, single-cell labeling, and neuron tracking have allowed observation of outer retina neuron translocation (Kaewkhaw et al. 2015; Suzuki et al., 2013; Mattar et al., 2018). Rods appear to undergo two types of movement. The first appears to be postmitotic apical and basal movements within the ONL (Figure 4C) as revealed by phenotypes following manipulation of the transcription factor Casz1. Overexpression of Casz1 in rods resulted in rod bias towards the basal ONL, while Casz1 knockdown resulted in rod bias towards the apical surface (Mattar et al., 2018). The Drosophila protein kinase Misshapen (Msn) is also required to regulate apical photoreceptor nuclear migration (Houalla et al., 2005). The second form of rod movement impacts a curious rod subset (~30%, Sarin et al., 2018) that appears in the INL early in development (Figure 4C). From P5 to P8, it is presumed these rods migrate apically from the INL into the ONL, as there is in an increase in ONL thickness and a reduction in INL thickness (Sarin et al., 2018). While this phenomenon was observed decades ago, only a handful of genes have been identified that regulate it. Mutations in the SUN/KASH proteins Syne-2 and Sun-1 or the serine/threonine kinase LKB1 exhibit rod migration defects (Yu et al., 2011; Razafsky et al., 2012; Burger et al., 2020).

Cones also undergo postmitotic migration in order to achieve their final apical position in the retina (Figure 4D). These movements occur from P4 to P12 (Rich et al., 1997). Very few molecular regulators of cone postmitotic migration have been identified, and several of these appear to be conserved in rod movement. Loss of LKB1, Syne-2, or Sun-1 in different species results in cone nuclear placement in the basal retina (Yu et al., 2011; Tsujikawa et al., 2007; Kracklauer et al., 2007; Patterson et al., 2004; Razafsky et al., 2012; Burger et al., 2021). Though it is unknown why cones must be apically located, it is clear that this organization is important for their function (Burger et al., 2021). One theory is that cones require rapid transport of proteins to the outer segment in response to stimuli (Pearring et al., 2013; Slepak and Hurley, 2008). Another is that cone nuclei are apically positioned close to the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) for efficient recycling of chromophores (Wang et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2009). Alternatively, cone nuclei themselves could physically anchor certain cone-specific visual cycle enzymes (Xue et al., 2017). Further studies are needed to identify the molecular mechanisms involved in both rod and cone translocations and to understand why they occur.

Postsynaptic outer retina neurons also occupy distinct retina lamina: horizontal cells are in the INL and border the OPL, while bipolar cell bodies are located within the apical half of the INL. Each of these cell types undergo distinct migration patterns. For unknown reasons, precursor horizontal cells traverse the entire width of the retina before returning to their stereotypical location (Figure 4B; Huckfeldt et al., 2009; Prada et al., 1984; Liu et al., 2000; Wässle et al., 2000; Edqvist and Hallböök, 2004). A detailed analysis in zebrafish revealed that horizontal cells exhibit a bipolar morphology as they move from their apical birth site to the middle of the retina followed by a switch to a multipolar phase to continue their descent into the INL. Lastly, horizontal cells move apically back to their appropriate lamina in the INL, where they fine-tune their final position (Chow et al., 2015; Edqvist and Hallböök, 2004). While this is the stereotypic pattern of horizontal cell migration, light sheet imaging of zebrafish retina revealed highly stochastic patterns of migration of individual cells, including diverse timing of cell cycle exit and length of migration (Amini et al., 2019). To date, only one molecule, Lim1, has been implicated in horizontal cell migration (Poché et al., 2007). Loss of Lim1 results in failure of some, but not all, horizontal cells to migrate back up towards the outer retina. Interestingly, these misplaced horizontal cells adopt an amacrine cell morphology but do not adopt an amacrine cell fate, as they do not express any typical amacrine cell markers (Poché et al., 2007). Finally, amongst all outer retina neuron types, least is known about bipolar cell migration. Live imaging in zebrafish revealed an apical process attached to the cell soma of future bipolar cells, which was lost just before entry into their terminal division (Weber et al., 2014). It has been postulated that these cells undergo a similar migration pattern as retinal ganglion cells that involves bipolar translocation. Thus, mysteries remain as to how and when bipolar cells migrate and what the molecular mechanisms are that drive their movement. More broadly, additional research is needed to elucidate migration kinetics in mammalian models, determine whether outer retina neuron migration is driven by external or intrinsic cues, and assess the influence of other neuron types on outer retina neuron trajectories.

Developmental features of outer retina synapse organization

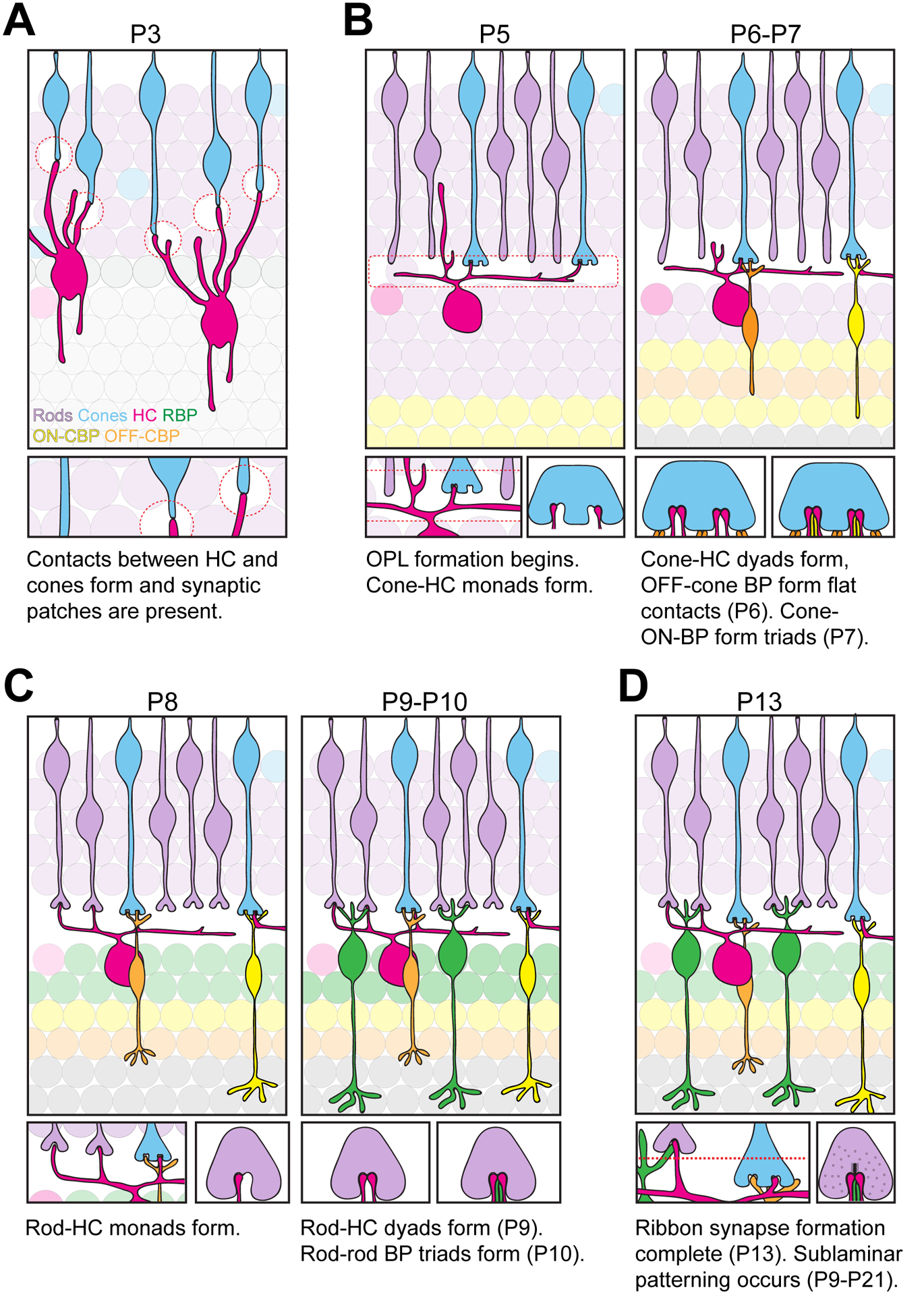

Synapse formation in the outer retina has been well described at the anatomical and ultrastructural level (Figure 5). However, the molecular and cellular regulators underlying these events are less understood (Olney, 1968; Blanks et al., 1974; Rich et al., 1997; Sherry et al., 2003). Horizontal cells and cones are the first cells to form contacts in the outer retina at ~P3 (Figure 5A, Huckfeldt et al., 2009; Sarin et al., 2018; Burger et al., 2020). Cones are present at the apical surface of the outer neuroblast layer (ONBL) and extend long, nascent axons that contact neurites of horizontal cells present in the middle of the ONBL. These contacts are the first evidence of the future OPL and drive the appearance of nuclear-free patches. These patches constitute the boundary between the future ONL and INL and converge by P5 to form the nascent OPL (Figure 5B, Burger et al., 2020). At this time, synaptogenesis between horizontal cells and cones commences with a monad horizontal cell contact at each nascent ribbon site. Beginning at P6, another horizontal cell neurite invaginates into the same cone pedicle, forming a dyad. From P7 to P10, ON cone bipolar cells invade the cone pedicle forming the classic ribbon synapse triad structure (Figure 5C). Both rod bipolar cells and OFF cone bipolar cells form flat contacts outside of this triad on cone pedicles (Sterling and Matthews, 2005; tom Dieck and Brandstatter, 2006; Mataruga et al., 2007; Fyk-Kolodziej et al.,2003; Haverkamp et al., 2008; Chen and Witkovsky, 1978; Haverkamp et al., 2003; Peng et al., 2018). Rod synaptogenesis and OPL sublamination follow cone synapse formation. Developing rod spherules connect with a horizontal cell axon to form a monad contact at P8 that is followed by a dyad contact at P9 (Figure 5C). Whether or not these contacts arise from the same or different horizontal cell axons has not been determined. At P10, rod bipolar cells begin to invaginate rod terminals. Finally, sublaminar patterning of rod and cone terminals occurs from P9 to P21 (Figure 5D). Through unknown mechanisms, rod spherules become located in the apical region of the OPL, while cone pedicles localize in the basal region directly beneath the rod spherules. These events result in highly ordered OPL consisting of non-overlapping cone and rod synapses.

Figure 5. Ultrastructural and anatomical events that underlie outer retina synaptogenesis.

A. Schematic of OPL development at P3. The outer retina contains developing cones (blue) whose axons form contacts with horizontal cell neurites (magenta) at P3 forming synaptic patches (red circles). B. Schematic of OPL development from P5 to P7. Synaptogenesis between cones and horizontal cells begins at P5 forming the nascent OPL (red box). At this time, horizontal cells form a monad connection with cones. At P6, horizontal cells form a dyad connection with cones, while cones and OFF-cone bipolar cells (orange) form flat contacts at the base of the pedicle. At P7, cones and ON-cone bipolar cells (yellow) form triad connections and mGluR6 expression becomes apparent (Sarin et al., 2018). C. Schematic of OPL development from P8 to P10. Rods (purple) undergo synaptogenesis with horizontal cells forming a monad contact. At P9, horizontal cells form a dyad connection with rods, followed by triad connections between rods and rod bipolar cells (green) at P10. mGluR6 is not observed in rod terminals until P13 (Sarin et al., 2018). D. Schematic of OPL development at P13 and beyond. Ribbon synapse formation is complete, and sublaminar patterning of the OPL continues until P21.

Molecular regulation of outer retina synapse emergence

The nascent OPL emerges prior to the formation of functional synapses. Thus, to achieve proper connectivity, outer retina neurons must: 1) correctly form initial cellular contacts that set up the nascent OPL; 2) properly elaborate their dendrites and axons; and 3) form specific connections with their downstream partners. We now discuss the molecular pathways that have been implicated in each of these events.

Coordinators of early OPL emergence

Only a few cellular and molecular regulators of nascent OPL emergence have been identified to date. In a recent study we showed that one of these appears to be the serine-threonine kinase LKB1 (Burger et al., 2020). The absence of retinal LKB1 caused a marked mislocalization and delay in OPL formation. In parallel, LKB1 mutants showed altered postsynaptic horizontal cell refinement and presynaptic photoreceptor axon growth. These defects coincided with altered synapse protein organization, and horizontal cell neurites were misdirected to ectopic synapse protein regions. Whether these alterations are a cause or consequence of altered synapse emergence is currently unclear. In addition, a screen for OPL regulators identified the non-canonical Wnt signaling pathway as an OPL organizer. Wnt5a/5b in bipolar cells is detected by Fzd4 and Fzd5 receptors in rods, and loss of this signaling pathway results in the formation of two OPL layers (Sarin et al., 2018). In both layers, photoreceptors appear to form proper connections with bipolar cells and horizontal cells, suggesting these genes are not required for neurite targeting but rather rod terminal localization and OPL presence.

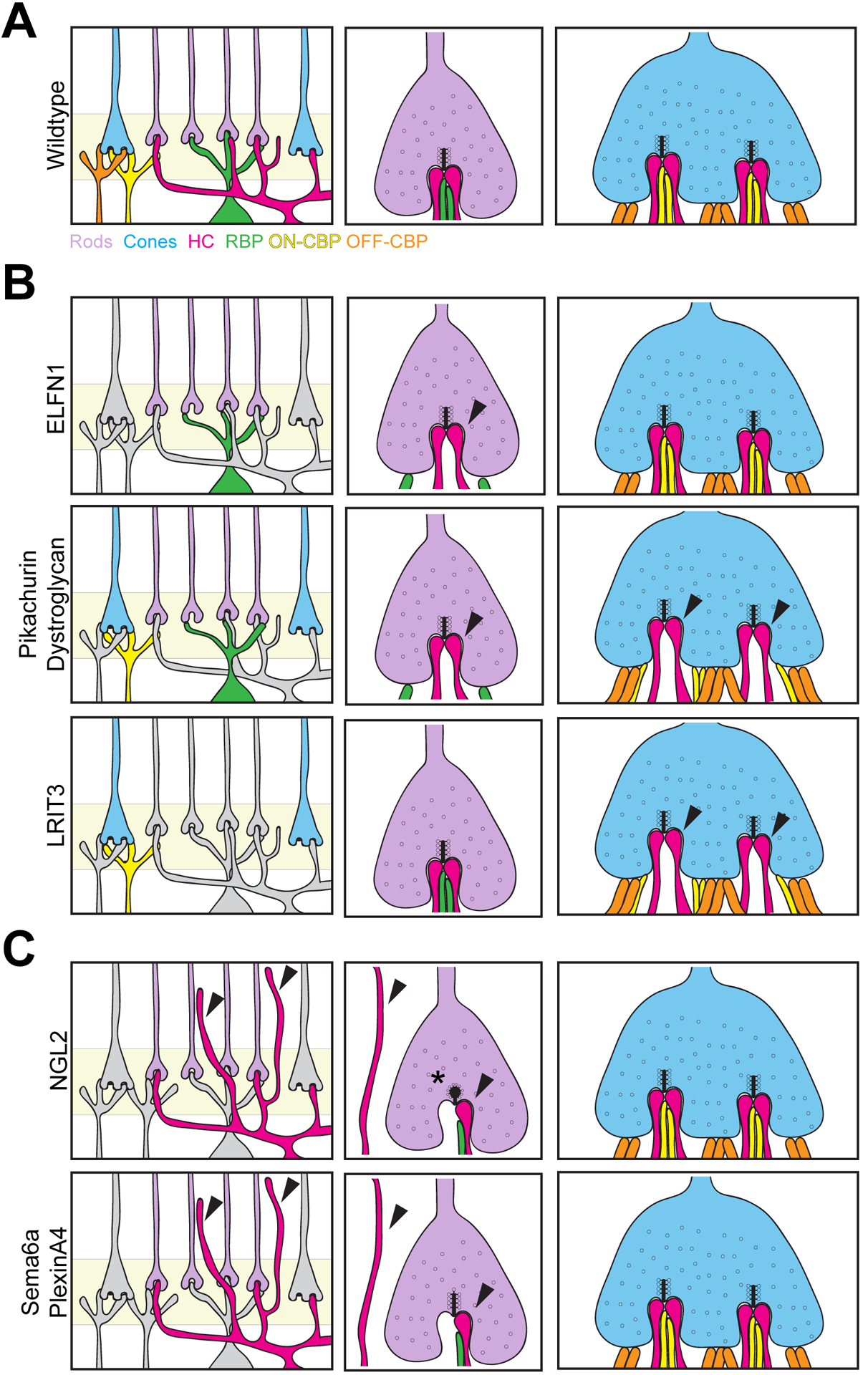

Mechanisms involved in neurite targeting

How might an outer retina neuron know how to send their neurites to the right location and array them in the correct shape? Evidence points to key roles played by growth factors, cell adhesion proteins, and synapse organizing molecules (Figure 6; Table 3). The list of cell adhesion molecules that impact OPL organization is most numerous. For example, extracellular ELFN1 (leucine-rich repeat fibronectin type III domain containing 1) is expressed on rod terminals and physically anchors mGluR6 on rod bipolar cells. Loss of this protein results in failure of rods to form connections with rod bipolar cells (Cao et al., 2015). Similarly, presynaptic dystroglycan appears to interact with the orphan receptor GPR179 at photoreceptor synapses with ON bipolar cells via the ECM protein pikachurin (Orlandi et al., 2018; Omori et al., 2012). Loss of dystroglycan or pikachurin results in abnormal apposition of ON-bipolar dendritic cell tips to photoreceptor ribbon synapses (Sato et al., 2008; Omori et al., 2012). Finally, LRIT3 (Leucine Rich Repeat, Ig-Like And Transmembrane Domains 3) was recently identified in photoreceptor synaptic terminals and is required for the recruitment of the synaptic protein nyctalopin and non-specific cation channel TRPM1 to the dendritic tips of ON bipolar cells. Interestingly, LRIT3 knockout animals show a decrease in invaginating ON cone bipolar cell dendrites but not rod bipolar cell dendrites, suggesting that LRIT3 is specifically required for cone but not rod ON bipolar cell neurite targeting (Hasan et al., 2019; Hasan et al., 2020; Neuillé et al., 2015; Neuillé et al., 2017). Molecules that anchor horizontal cell neurites to presynaptic terminals have also been uncovered. Netrin-G ligand 2 (NGL-2) is required for horizontal cell targeting to rods, and deletion of NGL-2 results in abnormal horizontal cell axon stratification with no observable changes to dendrites (Soto et al., 2013). The guidance cue Sema6a and its receptor PlexinA4 are also required for horizontal cell targeting to rod terminals. Loss of either gene results in aberrant horizontal cell dendritic arborization into the ONL (Matsuoka et al., 2012). Finally, sensory stimulation has been shown to be important for shaping neuron connectivity in the outer retina. Dark rearing reduces mGluR6 expression on ON-cone bipolar subtypes 6, 7, and 8 (Dunn et al., 2013). This was followed by a decrease in contacts made between cones and Type 8 ON-cone bipolar cells but not Type 6 bipolar cells (Dunn et al., 2013).

Figure 6. Genes involved in neurite targeting.

A. The OPL of wildtype retina is highly ordered, with neurites from pre and postsynaptic cells precisely targeted to the terminals of rods and cones. Rod spherules contain two lateral horizontal cell axons and two or more central bipolar cell dendrites. Each cone pedicle invagination contains two lateral horizontal cell dendrites, one or more centrally localized ON-cone bipolar cell contact, and flat contacts with OFF-cone bipolar cells. B. Genes involved in bipolar cell targeting to photoreceptors. ELFN1, pikachurin, and dystroglycan are required for rod bipolar cell invagination into rod terminals, while LRIT3, pikachurin, and dystroglycan are required for cone bipolar cell invagination into cone terminals. Defects are denoted by arrows, while cells reported to be normal in the mutant lines are shown in grey. C. Genes involved in horizontal cell neurite targeting. Loss of Sema6a, PlexinA4, or NGL2 results in horizontal cell neurite sprouting into the outer retina and reduced invagination into rod terminals (arrows). NGL2 mutants also exhibit an increase in spherical and club-shaped ribbons (asterisk). Cells reported to be normal in the mutant lines are shown in grey.

Table 3:

Mechanisms involved in murine outer retina neurite targeting.

| Gene | Function | Structural Changes in Mouse Mutants | Functional Changes in Mouse Mutants | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ELFN1 |

|

|

|

|

| Pikachurin |

|

|

|

|

| Dystroglycan |

|

|

|

|

| Dark Rearing |

|

|

|

|

| LRIT3 |

|

|

|

|

| NGL-2 |

|

|

|

|

| Sema6a |

|

|

N/A | |

| PlexinA4 |

|

|

N/A |

Maintenance of outer retina synapses

Outer retina synapses are prone to remodeling

Diseases that impact outer retina integrity often lead to photoreceptor degeneration and irreversible vision loss. Among the most common and impactful of these are age-related macular degeneration, diabetic retinopathy, and retinitis pigmentosa (Liu et al., 2016; Ting et al., 2016; Lee et al., 2015; Tsang and Sharma, 2018; Ferrari et al., 2011; Hernández-Zimbrón et al., 2018). Despite their diverse etiologies, many of these diseases share similar outer retina pathologies. These include a decreased number of synapses, alterations in neural function, changes in nuclear position, remodeling of horizontal and bipolar cell dendrites, and photoreceptor degeneration (Samuel et al., 2011; Gartner and Henkind, 1981; Pow and Sullivan, 2007). Efforts to repair vision in these and other blinding diseases have focused heavily on cellular transplant therapies (Wang et al., 2020; Harris et al., 2016; Struzyna et al., 2014; Struzyna et al., 2015; Cullen et al., 2012). However, these replacement neurons will have little ability to restore vision unless they can properly integrate and wire within the retinal circuit. Thus, elucidating both the cellular and molecular mechanisms that underlie synapse formation and integrity in the outer retina remains a key goal. We discuss outer retina synapse maturation and maintenance pathways below.

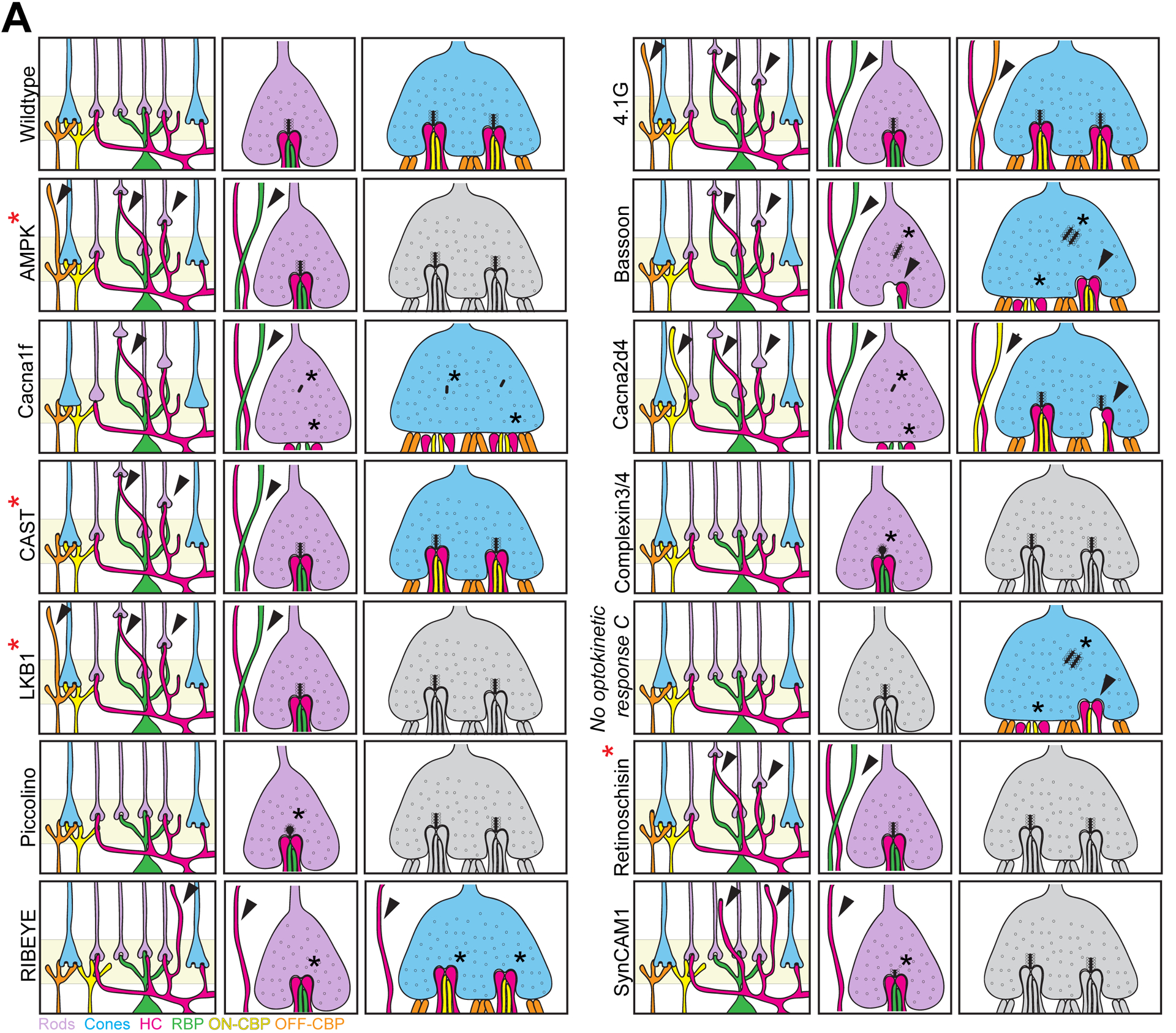

OPL maturation and maintenance requires synapse activity

Regulators of synapse activity and organization, particularly in rods, are important for OPL integrity in both late development and adulthood. While each synapse maintenance gene causes some unique OPL alterations, many share common structural defects within diseased retina. These include rod terminal retraction, misplaced and/or reduced OPL synapses, and ectopic neurite sprouting of both horizontal and bipolar cells into the ONL. For example, loss of the structural proteins and ribbon active zone organizers Bassoon, RIBEYE, 4.1G, CAST, Retinoschisin, or piccolino results in structural changes to ribbons, including retraction of rod terminals, remodeling of interneuron neurites, and reduced retinal function (Figure 7; Table 4, Dick et al., 2003; Sato et al., 2008; Omori et al., 2012; Mukherjee et al., 2010; Maxeiner et al., 2016; Sanuki et al., 2015; tom Dieck et al., 2012; Kjellstrom et al., 2007; Takada et al., 2008). It is likely that these defects are associated with decreased glutamate release, as altered ribbon structures result in decreased synaptic vesicle fusion and release. A similar set of defects is observed with loss of cell adhesion molecules that play essential roles in establishing and remodeling synapses (Ribic et al., 2014; Tanabe et al., 2006). These include the immunoglobulin-superfamily member SynCAM1 (Ribic et al., 2014). Calcium channels are also important for neurotransmitter release and synapse maintenance (Zenisek et al., 2003; Frank et al., 2010, Jing et al., 2013). For example, the Cav1.4 channel triggers vesicular release of glutamate from photoreceptors, and loss of this channel (Cacna1f, Cacna2d4) or regulators of it (CaBP4) results in immature synaptic ribbons that ultimately lead to OPL remodeling (Haeseleer et al., 2004; Liu et al., 2013b; Mansergh et al., 2005; Zabouri and Haverkamp, 2013; Chang et al., 2006; Wycisk et al., 2006). Interestingly, a mutation that prevents calcium influx from the Cav1.4 channel (G369i) did not alter the location of presynaptic proteins that were absent in Cav1.4 knockout animals. Rather, branching neurites in these mutants formed non-invaginating triadic contacts close to anchored ribbons. Thus, the Cav1.4 protein appears to modulate molecular assembly of the synapse, while calcium signaling through this channel may affect postsynaptic neurite organization (Maddox et al., 2020). Finally, mutations that affect signaling in postsynaptic neurons (mGluR6, GoA, Nyx, and Trpm1) have not been associated with OPL structural changes (Masu et al., 1995; Tagawa et al., 1999; Dhingra et al., 2000; Pinto et al., 2007). These data suggest that rod-specific activity is important for maintaining the organization of these connections.

Figure 7. Genes involved in OPL maturation and maintenance.

Schematic of genes involved in OPL maturation and maintenance. Wildtype outer retina synapses maintain their precise connectivity over time. Postsynaptic horizontal cell (magenta), rod bipolar cell (green) and cone bipolar cell (yellow) neurites remain confined to the OPL where they exactly oppose presynaptic cone (blue) and rod (purple) terminals in this region. Bassoon, Cacna1f, Cacna2d4, and RIBEYE are required for proper ribbon synaptic structure in both rod and cone terminals, and interneuron neurite sprouting and rod terminal retraction are observed in mutant lines. Complexin 3 and 4, piccolo isoform piccolino, and SynCAM1 are also required for proper rod ribbon structure, while the ultrastructure of cones was not reported (grey). No optokinetic response (nrc) mutants appear similar to Bassoon mutants but affects cone terminals. Rod terminals have not been examined in this line (grey). Deletion of 4.1G and CAST does not affect ribbon ultrastructure, but remodeling of pre and postsynaptic cells is observed. Similar remodeling of rod terminals occurs with the loss of LKB1, AMPK, or retinoschisin. Cone pedicles were not examined in these lines (grey). Neurite remodeling is denoted by arrowheads, while changes to the ribbon are denoted by a black asterisk. A red asterisk denotes perturbations that occur after P13.

Table 4:

Genes implicated in murine OPL maturation and maintenance.

| Gene | Function | Structural Changes | Functional Changes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bassoon |

|

|

|

|

| RIBEYE |

|

|

|

|

| 4.1 G |

|

|

|

|

| Piccolo |

|

|

N/A | |

| SynCAM1 |

|

|

|

|

| Cacna1f (nob2) |

|

|

|

|

| Cacna2d4 |

|

|

|

|

| CaBP4 |

|

|

|

|

| Complexin3 |

|

|

|

|

| Complexin4 |

|

|

|

|

| No optokinetic response C (NRC; zebrafish) |

|

|

|

|

| Retinoschisin |

|

|

|

|

| CAST |

|

|

|

|

| LKB1 |

|

|

|

Fewer genes have been implicated in the structural maintenance of cone synapses perhaps because cones form many ribbons with multiple postsynaptic partners or because measuring changes to cone synapse organization requires more precise methods. Instead, most regulators have been identified through defects in visual function as measured by optokinetic responses or electroretinography (ERG) followed by confirmatory electron microscopy (EM) experiments. For example, LRIT1 binds Frmpd2, a scaffolding protein present in cone terminals, and appears to regulate synaptic clustering and cone pedicle size (Ueno et al., 2018). Furthermore, zebrafish mutants of the endocytosis protein synaptojanin 1 are named for their lack of optokinetic response (nrc, no optokinetic response c). While cone pedicle ribbons could form in this mutant, they were floating, resulting in fewer vesicles being released and a failure to form synapses with bipolar cells (Allwardt et al., 2001; Van Epps et al., 2004).

Still other studies have asked whether postsynaptic neurons themselves are required for OPL organization and maintenance. Horizontal cells are key candidates since they are the first to establish contacts with both cones and rods and invaginate the nascent synapse. Indeed, developmental deletion of horizontal cells from the retina prevented rod bipolar cell dendrites from entering rod terminals (Nemitz et al., 2019). Furthermore, loss of horizontal cells resulted in shorter presynaptic ribbons, which coincided with reduced expression of the postsynaptic proteins GPR179 and mGluR6, suggesting that horizontal cells are required for proper neurotransmission (Nemitz et al., 2019). Similarly, loss of cones results in mislocalization and decreased expression of mGluR6 in ON-cone bipolar cells (Care et al., 2019; Dunn et al., 2019). In contrast, contacts between cones and cone bipolar cells are still made in the absence of horizontal cells, but these contacts are atrophic leading to altered cone pedicle spatial distribution (Keeley et al., 2013). Finally, horizontal cells are also required for OPL maintenance, as deletion of horizontal cells from adult retina results in photoreceptor degeneration (Sonntag et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2013). The effects of rod bipolar cells on outer retina formation have recently been analyzed using CRISPR/cas9 to delete the VSX2 core regulatory circuit super enhancer, which resulted in a complete loss of bipolar cells. Bipolar cell deletion disrupted the OPL, though electron microscopy revealed that horizontal cells could still invaginate rod and cone terminals (Norrie et al., 2019). It would be interesting to determine whether and how removing bipolar cell subsets impacts OPL development and maintenance.

Outer retina synapse maintenance requires balanced metabolism.

Phototransduction, protein transport, and neurotransmitter uptake and release are all energetically demanding, and the retina is one of the most metabolically active regions in the body (Wong-Riley, 2010). Perhaps it is not surprising then, that several regulators of metabolism have been implicated in OPL maintenance. For example, deletion of either ApoER2 or VLDLR, low density lipoprotein receptors that play key roles in cholesterol homeostasis, cause functional visual decline over time (Trotter et al., 2011). Similarly, deletion of the lipoprotein receptor binding molecules Reelin and Dab1 also cause defects in rod signaling through alterations to rod bipolar cells (Rice et al., 2001). These data suggest that cholesterol homeostasis is important for outer retina function. Intracellular metabolic sensors also play key roles in OPL maintenance. Normal aging in mice and humans is associated with defects in OPL organization including familiar changes to rod terminal location, synapse organization defects, and horizontal and bipolar cell neurite sprouting (Liets et al., 2006; Eliasieh et al., 2007; Samuel et al., 2011). These structural alterations are accompanied by marked reductions in the activation of AMPK, a crucial energy sensor (Samuel et al., 2014). We have shown that deletion of AMPK or its upstream kinase LKB1 specifically in rods results in age-related changes in young adult mice (Samuel et al., 2014). These results are in line with those that implicate AMPK in other neurodegenerative diseases (Domise et al., 2016; Ju et al., 2011; Vingtdeux et al., 2011; Thornton et al., 2011). Finally, we found that increasing active AMPK directly with a constitutively active form of the enzyme or indirectly through caloric restriction reduced the number of ectopic synapses in old animals (Samuel et. al., 2014). Thus it is possible that age-related structural defects in outer retina could be repaired by modulating cellular metabolism through AMPK or other pathways. While additional studies are needed to define the precise downstream pathways upon which these molecules impinge, these data suggest that metabolic signaling is crucial for maintaining outer retina integrity.

Concluding remarks

The outer retina has proven a useful system for understanding the cellular and molecular pathways that underlie formation and maintenance of neural circuits both in the CNS in general and in the retina specifically. While perhaps more is known about these synapses than any other in the CNS, surprisingly large gaps in knowledge remain. First, relatively few molecular regulators of outer retina formation, including migration and OPL emergence, have been documented, and almost nothing is known about what drives sublaminar organization. The advent of single-cell sequencing and retina-specific CRISPR-based screening technology (Sarin et al., 2018; Macosko et al., 2015) will allow for the identification of pathways that govern the formation of the OPL. Indeed, such studies have been completed or are underway (Shekhar et al., 2016; Sarin et al., 2018). Second, how do dynamic changes to retina neuron structure correspond with the static images of neuron development and synapse emergence we are most familiar with? Techniques involving live imaging or light sheet microscopy in whole retina or retina slices (Barasso et al., 2018; Amini et al., 2019) combined with genetic or viral-based neuron or synapse labeling (Mattar et al., 2018; Samuel et al., 2014) could allow us to see cell migration, neuron maturation, and synapse formation as it unfolds in real time. Third, what is the precise molecular composition and organization of cone and rod synapses? While we know a host of molecules are found at these synapses (See Figure 3), we know little about their arrangement relative to each other, their density, or how they change in development and disease. Answering these questions will require nanoscopic imaging methods compatible with native tissue and diverse molecular targets. Fourth, it will be important to fully resolve the role of activity and competition in synapse formation and maintenance if we are to restore visual function in those that have lost it. While we have some hints about the pathways involved we lack a unified understanding of the molecular and cellular events. Finally, several pieces of evidence indicate that outer retina synapses are particularly structurally plastic even into adulthood. They are often the first to remodel following a host of insults. Encouragingly, this may mean that they retain the capacity for repair (Samuel et al., 2014). Studies aimed at understanding the regulators of this adult plasticity may eventually prove useful in efforts aimed at restoring functional circuits in retinal and perhaps even other CNS disease.

Highlights.

Review photoreceptor synaptic architecture and proteins.

Delineate migration modes and pathways involved in the positioning of individual neuron types.

Analyze anatomical and ultrastructural events that underlie synapse formation.

Reveal mechanisms involved in neurite targeting and synapse maturation and maintenance.

Acknowledgements

We thank members of our laboratory for scientific discussions and advice. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH, DP2EY02798, 1R56AG061808, and R01EY030458 to M.A.S.), the Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas, the Brain Research Foundation, and the Ted Nash Long Life Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Competing Financial Interests. The authors declare no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- Aartsen WM, Arsanto JP, Chauvin JP, Vos RM, Versteeg I, Cardozo BN, Bivic AL, and Wijnholds J (2009). PSD95beta regulates plasma membrane calcium pump localization at the photoreceptor synapse. Mol. Cell. Neurosci 41, 156–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aartsen WM, Kantardzhieva A, Klooster J, van Rossum AGSH, can de Pavert SA, Versteeg I, Cardozo BN, Tonagel F, Beck SC, Tanimoto N, Seeliger MW, and Wijnholds J (2006). Mpp4 recruits PSD95 and Veli3 towards the photoreceptor synapse. Hum. Mol. Genet 15, 1291–1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ackermann F, Schink KO, Bruns C, Izsvák, Kent Hamra F, Rosenmund C, and Garner CC (2019). Critical role for piccolo in synaptic vesicle retrieval. eLife 8, e46629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allwardt BA, Lall AB, Brockerhoff SE, and Dowling JE (2001). Synapse formation is arrested in retinal photoreceptors of the zebrafish nrc mutant. J. Neurosci 21, 2330–2342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alpadi K, Magupalli VG, Käppel S, Köblitz L, Schwarz K, Seigel GM, Sung CH, and Schmitz F (2008). RIBEYE recruits Mnc119, a mammalian ortholog of the Caenorhabditis elegans protein unc 119, to synaptic ribbons of photoreceptor synapses. J. Biol. Chem 283, 26461–26467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amini R, Labudina AA, and Norden C (2019). Stochastic single cell migration leads to robust horizontal cell layer formation in the vertebrate retina. Development 146, dev173450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asteriti S, Gargini C, and Cangiano L (2014). Mouse rods signal through gap junctions with cones. eLife 3, e01386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astertiti S, Gargini C, and Cangiano L (2017). Connexin 36 expression is required for electrical coupling between mouse and rod cones. Vis. Neurosci 34, E006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrasso AP, Wang S, Tong X, Christiansen AW, Larina IV, and Pochè RA (2018). Live imaging of developing retinal slices. Neural Dev. 13, 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augustin I, Rosenmund C, Südhof TC, and Brose N (1999). Munc13–1 is essential for fusion competence of glutamatergic synaptic vesicles. Nature 400, 457–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes S, Merchant V, and Mahmud F (1993). Modulation of transmission gain by protons at the photoreceptor output synapse. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 90, 10081–10085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baye LM, and Link BA (2007a). The disarrayed mutation results in cell cycle and neurogenesis defects during retinal development in zebrafish. BMC Dev. Biol 7, 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baye LM, and Link BA (2007b). Interkinetic nuclear migration and the selection of neurogenic cell divisions during vertebrate retinogenesis. J. Neurosci 27, 10143–10152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayley PR, and Morgans CW (2007). Rod bipolar cells and horizontal cells form displaced synaptic contacts with rods in the outer nuclear layer of the nob2 retina. J. Comp. Neurol 500, 286–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baylor DA, Fuortes MG, and O’Bryan PM (1971). Receptive fields of cones in the retina of the turtle. J. Physiol 214, 265–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens C, Schubert T, Haverkamp S, Euller T, and Berens P (2016). Connectivity map of bipolar cells and photoreceptors in the mouse retina. Elife 5, pii:e20041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernston AK, and Morgans CW (2003). Distribution of the presynaptic calcium sensors, synaptotagmin I/II and synaptotagmin III, in the goldfish and rodent retinas. J. Vis 3, 274–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biehlmaier O, Makhankov Y, and Neuhauss SCF (2007). Impaired retinal differentiation and maintenance in zebrafish laminin mutants. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci 48, 2887–2894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanks JC, Adinolfi AM, and Lolley RN (1974). Synaptogenesis in the photoreceptor terminal of the mouse retina. J. Comp. Neurol 156, 81–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boycott BB, Hopkins JM, and Sperling HG (1987). Cone connections of the horizontal cells of the rhesus monkey’s retina. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci 229, 345–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandstätter JH, Koulen P, and Wässle H (1998). Diversity of glutamate receptors in the mammalian retina. Vision Res. 38, 1385–1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandstätter JH, Wässle H, Betz H, and Morgans CW (1996). The plasma membrane protein SNAP-25, but not syntaxin, is present at photoreceptor and bipolar cell synapses in the rat retina. Eur. J. Neurosci 8, 823–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breuninger T, Puller C, Haverkamp S, and Euler T (2011). Chromatic bipolar cell pathways in the mouse retina. J. Neurosci 17, 6504–6517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brose N, Petrenko AG, Südhof TC, and Jahn R (1992). Snaptotagmin: a calcium sensor on the synaptic vesicle surface. Science 256, 1021–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brzezinski JA, and Reh TA (2015). Photoreceptor cell fate specification in vertebrates. Development 142, 3263–3273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley K, and Kelly RB (1985). Identification of a transmembrane glycoprotein specific for secretory vesicles of neural and endocrine cells. J. Cell Biol 100, 1284–1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger CA, Alevy J, Casasent AK, Jiang D, Albrecht NE, Liang JH, Hirano AA, Brecha NC, and Samuel MA (2020). LKB1 coordinates neurite remodeling to drive synapse layer emergence in the outer retina. Elife, 9, e56931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger CA, Albrecht NE, Jiang D, Liang JH, Poché RA, and Samuel MA (2021). LKB1 and AMPK instruct cone nuclear position to modify visual function. Cell Rep. 34, 108698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calegari F, and Huttner WB (2003). An inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinases that lengthens, but does not arrest, neuroepithelial cell cycle induces premature neurogenesis. J. Cell Sci 116, 4947–4955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JR, Li H, Wang Y, Kozhemyakin M, Hunt AJ, Liu X, Janz R, and Heidelberger R (2020). Phosphorylation of the retinal ribbon synapse specific t-SNARE protein syntaxin3b is regulated by light via a calcium-dependent pathway. Front. Cell Neurosci 14, 587072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y, Posokhova E, and Martemyanov KA (2011). TRPM1 forms cmoplexes with nyctalopin in vivo and accumulates in postsynaptic compartment of ON-bipolar neurons in mGluR6-dependent manner. J. Neurosci 31, 11521–11526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y, Sarria I, Fehlhaber KE, Kamasawa N, Orlandi C, James KN, Hazen JL, Gardner MR, Farzan M, Lee A, Baker S, Baldwin K, Sampath AP, and Martemyanov KA (2015). Mechanism for selective synaptic wiring of rod photoreceptors into the retinal circuitry and its role in vision. Neuron 87, 1248–1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caputo A, Piano I, Demontis GC, Bacchi N, Casarosa S, Santina LD, and Gargini C (2015). TMEM16A is associated with voltage-gated calcium channels in mouse retina and its function is disrupted upon maturation of the auxiliary a2g4 subunit. Front. Cell Nuerosci 9, 422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Care RA, Kastner DB, De la Huerta I, Pan S, Khoche A, Santina LD, Gamlin C, Santo Thomas C, Ngo J, Chen A, Kuo Y, Ou Y, and Dunn FA (2019). Partial cone loss triggers synapse-specific remodeling and spatial receptive field rearrangements in a mature retinal circuit. Cell Rep. 27, 2171–2183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter-Dawson LD, and LaVail MM (1979). Rods and cones in the mouse retina. I. Structural analysis using light and electron microscopy. J. Comp. Neurol 2, 245–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cepko C (2014). Intrinsically different retinal progenitor cells produce specific types of progeny. Nat. Rev. Neurosci 15, 615–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cepko CL, Austin CP, Yang X, Alexiades M, and Esseddine D (1996). Cell fate determination in the vertebrate retina. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 93, 589–595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapot CA, Behrens C, Rogerson LE,, Baden T, Pop S, Berens P, Euler T, and Schubert T (2017). Local signals in mouse horizontal cell dendrites. Curr. Biol 23, 3603–3615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan TL, Goodchild AK, and Martin PR (1997). The morphology and distribution of horizontal cells in the retina of a New World monkey, the marmoset Callithrix jacchus: a comparison with macaque monkey. Vis. Neurosci 14, 125–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang B, Heckenlively JR, Bayley PR, Brecha NC, Davisson MT, Hawes NL, Hirano AA, Hurd RE, Ikeda A, Johnson BA, McCall MA, Morgans CW, Nusinowitz S, Peachey NS, Rice DS, Vessey KA, and Gregg RG (2006). The nob2 mouse, a null mutation in Cacna1f: anatomical and functional abnormalities in the outer retina and their consequences on ganglion cell visual responses. Vis. Neurosci 23, 11–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaya T, Matsumoto A, Sugita Y, Watanabe S, Kuwahara R, Tachibana M, and Furukawa T (2017). Versatile functional roles of horizontal cells in the retinal circuit. Sci. Rep 1, 5540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F, and Witkovsky P (1978). The formation of photoreceptor synapses in the retina of larval Xenopus. J. Neurocytol 7, 721–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe H, Park JH, Kim YJ, and Ernst OP (2011). Transmembrane signaling by GPCRs: insight from rhodopsin and opsin structures. Neuropharmacology 11, 52–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow RW, Almeida AD, Randlett O, Norden C, and Harris WA (2015). Inhibitory neuron migration and IPL formation in the developing zebrafish retina. Development 142, 2665–2677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun MH, Grünert U, and Wässle H (1996). The synaptic complex of cones in the fovea and in the periphery of the macaque monkey retina. Vision Res. 36, 3383–3395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cibis GW, Fitzgerald KM, Harris DJ, Rothberg PG, and Rupani M (1993). The effects of dystrophin gene mutations on the ERG in mice and humans. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci 34, 3646–3652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper B, Hemmerlein M, Ammermüller J, Imig C, Reim K, Lipstein N, Kalla S, Kawabe H, Brose N, Brandstätter JH, and Veroqueaux F (2012). Munc13-independent vesicle priming at mouse photoreceptor ribbon synapses. J. Neurosci 32, 8040–8052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copenhagen DR, and Owen WG (1976). Coupling between rod photoreceptors in a vertebrate retina. Nature 260, 57–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen DK, Tang-Schomer MD, Struzyna LA, Patel AR, Johnson VE, Wolf JA, and Smith DH (2012). Microtissue engineered constructs with living axons for targeted nervous system reconstruction. Tissue Eng. Part A 18, 2280–2289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis L, Datta P, Liu X, Bogdanova N, Heidelberger R, and Janz R (2010). Syntaxin 3b is essential for the exocytosis of synaptic vesicles in ribbon synapses of the retina. Neuroscience 166, 832–841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis LB, Doneske B, Liu X, Thaller C, McNew JA, and Janz R (2008). Syntaxin 3b is a t-SNARE specific for ribbon synapses of the retina. J. Comp. Neurol 510, 550–559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Custer NV (1973). Structurally specialized contacts between the photoreceptors of the retina of the axolotl. J. Comp. Neurol 151, 35–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daydova D, Marini C, King C, Klueva J, Bischof F, Romorini S, Montenegro-Venegas C, Heine M, Schneider R, Schröder MS, Altrock WD, Henneberger C, Rusakov DA, Gundelfinger ED>, and Fejtova A (2014). Bassoon specifically controls presynaptic P/Q-type calcium channels via RIM-binding protein. Neuron 82, 181–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deguchi-Tawarada M, Inoue E, Takao-Rikitsu, Inoue M, Kitajima I, Ohtsuka T, and Takai Y (2006). Active zone protein CAST is a component of conventional and ribbon synapses in mouse retina. J. Comp. Neurol 495, 480–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deguchi-Tawarda M, Inoue E, Takao-Rikitsu E, Inoue M, Ohtsuka T, and Takai Y (2004). CAST2: identification and characterization of a protein structurally related to the presynaptic cytomatrix protein CAST. Genes Cells 9, 15–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Bene F, Wehman AM, Link BA, and Baier H (2008). Regulation of neurogenesis by interkinetic nuclear migration through an apical-basal Notch gradient. Cell 134, 1055–1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dembla E, Debla M, Maxeiner S, and Schmitz F (2020). Synaptic ribbons foster active zone stability and illumination-dependent active zone enrichment of RIM2 and Cav1.4 in photoreceptor synapses. Sci. Rep 10, 5957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- den Hollander AI, ten Brink JB, de Kok YJ, van Soest S, van den Born LI, can Driel MA, van de Pol DJ, Payne AM, Bhattacharya SS, Kellner U, Hoyng CB, Westerveld A, Brunner HG, Bleeker-Wagemakers EM Deutman AF, Heckenlively JR, Cremers FP, and Bergen AA (1999). Mutations in a human homologue of Drosophila crumbs cause retinitis pigmentosa (RP12). Nat. Gen 23, 217–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVries SH (2000). Bipolar cells use kainite and AMPA receptors to filter visual information into separate channels. Neuron 28, 847–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVries SH, Qi X, Smith R, Makous W, and Sterling P (2002). Electrical coupling between Mammalian cones. Curr. Biol 12, 1900–1907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhingra A, Lyubarsky A, Jiang M, Pugh EN, Birnbaumer L, Sterling P, and Vardi N (2000). The light response of ON bipolar neurons requires Galpha. J. Neurosci 20, 9053–9058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhingra NK, Ramammohan Y>, and Raju TR (1997). Developmental expression of synaptophysin, synapsin I, and syntaxin in the rat retina. Brain Res. Dev. Brain Res 102, 267–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick O, Hack I, Altrock WD, Garner CC, Gundelfinger ED, and Brandstätter JH (2001). Localization of the presynaptic cytomatrix protein Piccolo at ribbon and conventional synapses in the rat retina: comparison with bassoon. J. Comp. Neurol 439, 224–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick O, tom Dieck S, Altrock WD, Ammermüller J, Weiler R, Garner CC, Gundelfinger ED, and Brandstätter JH (2003). The presynaptic active zone protein bassoon is essential for photoreceptor ribbon synapse formation in the retina. Neuron 37, 775–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domise M, Didier S, Marinangeli C, Zhao H, Chandakkar P, Búee L, Viollet B, Davies P, Marambaud P, and Vingtdeux V (2016). AMP-activated protein kinase modulates tau phosphorylation and tau physiology in vivo. Sci. Rep 27, 26758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolón JF, Paniagua AE, Valle V, Segurado A, Arévalo R, Velasco A, and Lillo C (2018). Expression and localization of the polarity protein CRB2 in adult mouse brain: a comparison with the CRB1 RD8 mutant mouse model. Sci. Rep 8, 11652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling JE, and Boycott BB (1966). Organization of the primate retina: electron microscopy. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci 166, 80–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drenckhahn D, Holbach M, Ness W, Schmitz F, and Anderson LV (1996). Dystrophin and the dystrophin-associated glycoprotein, beta-dystroglycan, co-localize in photoreceptor synaptic complexes of the human retina. Neuroscience. 73, 605–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn FA, Santina LD, Parker ED, Wong ROL (2013). Sensory experience shapes the development of the visual system’s first synapse. Neuron 80, 1159–1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan JL, Yang H, Doan T, Silverstein RS, Murphy GJ, Nune G, Liu X>, Copenhagen D, Tempel BL, Rieke F, and Krizaj D (2006). Scotopic visual signaling in the mouse retina is modulated by high affinity plasma membrane calcium extrusion. J. Neurosci 26, 7201–7211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edqvist PHD, and Hallböök F (2004). Newborn horizontal cells migrate bi-directinoally across the neuroepithelium during retinal development. Development 131, 1343–1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn FA (2015). Photoreceptor ablation initiates the immediate loss of glutamate receptors in postsynaptic bipolar cells in retina. J. Neurosci 35, 2423–2431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliasieh K, Liets LC, and Chalupa LM (2007). Cellular reorganization in the human retina during normal aging. Invest. Opthalmol. Vis. Sci 48, 2824–2830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Euler T, Haverkamp S, Schubert T, and Baden T (2014). Retinal bipolar cells: elementary building blocks of vision. Nat. Rev. Neurosci 15, 507–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]