Abstract

Objectives

(1) To report maternal and newborn outcomes of pregnant women in areas of social deprivation in inner city London. (2) To compare the effect of caseload midwifery with standard care on maternal and newborn outcomes in this cohort of women.

Design

Retrospective observational cohort study.

Setting

Four council wards (electoral districts) in inner city London, where over 90% of residents are in the two most deprived quintiles of the English Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) (2019) and the population is ethnically diverse.

Participants

All women booked for antenatal care under Guys and St Thomas’ National Health Service Foundation Trust after 11 July 2018 (when the Lambeth Early Action Partnership (LEAP*) caseload midwifery team was implemented) until data collection 18 June 2020. This included 523 pregnancies in the LEAP area, of which 230 were allocated to caseload midwifery, and 8430 pregnancies from other areas.

Main outcome measures

To explore if targeted caseload midwifery (known to reduce preterm birth) will improve important measurable outcomes (preterm birth, mode of birth and newborn outcomes).

Results

There was a significant reduction in preterm birth rate in women allocated to caseload midwifery, when compared with those who received traditional midwifery care (5.1% vs 11.2%; risk ratio: 0.41; p=0.02; 95% CI 0.18 to 0.86; number needed to treat: 11.9). Caesarean section births were significantly reduced in women allocated to caseload midwifery care, when compared with traditional midwifery care (24.3% vs 38.0%; risk ratio: 0.64: p=0.01; 95% CI 0.47 to 0.90; number needed to treat: 7.4) including emergency caesarean deliveries (15.2% vs 22.5%; risk ratio: 0.59; p=0.03; 95% CI 0.38 to 0.94; number needed to treat: 10) without increase in neonatal unit admission or stillbirth.

Conclusion

This study shows that a model of caseload midwifery care implemented in an inner city deprived community improves outcome by significantly reducing preterm birth and birth by caesarean section when compared with traditional care. This data trend suggests that when applied to targeted groups (women in higher IMD quintile and women of diverse ethnicity) that the impact of intervention is greater.

Keywords: obstetrics, health policy, public health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study question addresses a clinically and economically important problem (preterm birth and mode of delivery) and first reports caseload midwifery effects in women disadvantaged due to social complexity.

This study pragmatically represents a clinical setting, including women of all medical risk, with intention-to-treat analysis, and thus, results reflect the reality of intervention in a non-study clinical practice.

Logistical regression analysis was performed using an established statistical method (inverse probability weighting) to correct for bias in case selection.

Confounders in caseload allocation and outcome may bias our results.

Numbers in less common outcomes are small (eg, stillbirth and neonatal death, NND), and NND may be underreported if they occurred outside the data collection period.

Introduction

Fetal outcome is affected by social deprivation and parental ethnicity.1 The English Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) comparatively ranks areas according to markers of socioeconomic deprivation using domains of income, employment, education, skills and training, health and disability, crime, barriers to housing services and living environment. In 2016, 25.9% of all stillbirths in the UK occurred in the most deprived IMD quintile compared with 14.9% in the least, with a similar distribution for neonatal death (NND) (25.7% and 15.9%, respectively).2 In 2017, the stillbirth rate for the UK was 3.74 per 1000, however, in black/black British and Asian/Asian British women, rates were 7.46 and 5.70 per 1000, respectively, with an increase in neonatal mortality (despite a downward trend in the white patient population).2 Preterm birth is more common in women affected by social deprivation,3 and the combination is associated with developmental problems in the early years.4 5 Preterm birth negatively impacts maternal mental health, relationships between child and caregiver, and interaction with support services.6

Maternal mortality doubles when comparing women in the least deprived IMD quintiles to women in the most deprived (5vs 12 per 100 000).7 Black women are five times more likely to die as a result of pregnancy than white women (38 compared with 7 per 100 000), women of mixed ethnicity three times, and women of Asian ethnicity two times more likely to die.7 Mortality is associated with suboptimal utilisation of antenatal services, including late/no booking and nonattendance, (most marked in black African, black Caribbean and Middle Eastern women).8 For each step up in deprivation quintile, women are more likely to receive no antenatal care (25% increase per quintile), to have an unplanned caesarean section (CS) (15% per quintile) and any (elective and emergency) CS (4% per quintile).9 Women with higher deprivation scores are less likely to be seen in the first trimester and more likely to report dissatisfaction with clarity of communication and respectful treatment by doctors and midwives.9

Considering that several causal determinants of adverse infant outcomes that are associated with low socioeconomic status are potentially avoidable, strategies that promise even modest improvements warrant serious consideration. Targeted interventions for vulnerable children in early childhood have been shown to work,10 11 to be economically effective,12 and have been incorporated into standard public health practice.13 Targeting early childhood alone misses the opportunity to address inequality in utero and the disparity already present at birth.

Caseload midwifery describes continuity of midwifery care from booking, to the postnatal period, with longer and more frequent antenatal appointments including in the home setting. Continuity of midwifery care has been shown to reduce preterm birth.14 If these findings are applicable in women whose infants are at greater risk of adverse outcomes, caseload midwifery as an intervention in a socially deprived and ethnically diverse inner city population, may begin to address this disparity. We aim to investigate caseload midwifery antenatal intervention and its potential for improving pregnancy outcomes in areas of social deprivation in inner city London.

Objectives

To report maternal and newborn outcomes of pregnant women in areas of social deprivation.

To compare maternal and newborn outcomes in this cohort of women when exposed to caseload midwifery intervention with standard care.

We hypothesise that in a deprived population cohort, outcomes will be poorer than in the general population. We propose that caseload midwifery will improve important measurable outcomes (in relation to gestational age and mode of birth) and bring them closer to the population mean.

Methods

Study design and data source

This was an observational, cohort study using retrospective data collected at Guys and St Thomas’ National Health Service (NHS) Foundation Trust, a tertiary level NHS facility in inner city London. Pregnant women who booked at Guys and St Thomas NHS foundation trust, between 11 July 2018 and 18 June 2020, were allocated to ‘traditional’ care or ‘caseload’ care by a screening administration team (following submission of a self or general practitioner (GP) referral form). In our main caseload midwifery comparator population, to meet the referral criteria caseload care, women were required to live in a Lambeth Early Action Partnership (LEAP*) area (defined by postcode, where more than 90% of women studied fall in the two most deprived IMD quintile,15 and meet the definition of ‘vulnerable’ (table 1). *The Lambeth Early Action Partnership (LEAP) programme is a 10-year programme that works with pregnant women and children aged 0–3 years and their families and aims to give them a better start. Part of this programme includes caseload midwifery care. The majority, of women allocated to caseload midwifery in this study were cared for by this team, and the postal code areas/wards are identified as areas of deprivation by the LEAP programme. However, some women received the same package of care under the umbrella of other caseload teams in Guys and St Thomas NHS Foundation trust. Other information on the referral form (see below), was not included in the defined allocation criteria. It was possible for a woman to be transferred from traditional care to caseload care due to an evolving issue later in pregnancy. Twin and triplet pregnancies, repeat pregnancies and patients with complex medical and obstetric histories were included. Ongoing pregnancies on 18 June 2020, and women marked ‘LEAP caseload’ with non-LEAP postal codes were excluded from the analysis and women with unknown midwifery care pathway.

Table 1.

Agreed definition of vulnerability from LEAP service plan

| Women who find services hard to access | Women needing multiagency services |

| Socially isolated women Those living in poverty/deprivation/who are homeless Refugees/asylum seekers Non-native language speakers Victims of abuse Sex workers Young mothers Unsupported mothers Women within travelling communities |

Women who are subject of safeguarding concerns Women with substance and/or alcohol abuse issues Women with physical/emotional and/or learning disabilities Women who have been victims of female genital mutilation Women who are HIV positive |

LEAP, Lambeth Early Action Partnership.

In caseload care, teams of 6 midwives care for 18 pregnant women/month. Primigravid and parous women received ten 30 min appointments in the woman’s home or clinic setting as standard. Individualised care pathways allowed frequent and longer visits as required. Two midwives were involved from booking to postnatal care for each patient. Teams were on call for labour and provided extended post-natal care (up to 28 days). Early in antenatal care, a multiagency referral (for support services) form was completed entitled ‘Safeguarding risks to the unborn’, as necessary. The midwifery team have access to social work, health visitors, substance use services and mental health services.

There were two routes for traditional care: (1) Traditional midwifery led care and (2) Consultant led/shared care. The traditional midwifery led care was for low-risk women, managed using the standard National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guideline pathway (ten 15 min appointments, mostly in a clinic setting for primiparous and seven for parous).16 A variable number of midwives were involved antenatally, with a new midwife in labour and a new midwife postnatally. Consultant-led/shared care was for women at high medical obstetric risk. The number of appointments was individualised, and appointments were usually 10–20 min in duration in an antenatal clinic setting. Antenatal midwifery involvement could vary significantly, with a new midwife in labour and a new midwife postnatally.

Non-LEAP area women received a mix of the above three models of care. Outcomes are reported as a guide for antenatal outcome standards in a less deprived, less diverse population.

Data collection

Anonymised data were extracted from maternity records (BadgerNet) and collated on an Excel spreadsheet. Variables recorded were type of midwifery care provided, postal code, age, marital status, body mass index, ethnicity and smoking status at booking and time of birth. Data on newborn outcomes including stillbirths, NND, neonatal admission, gestation of birth, birth weight, breast feeding at time of birth and skin to skin contact were recorded. Maternal morbidity including pregnancy induced hypertension (>140/90), pre-eclampsia (hypertension plus proteinuria,17 gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM: Glucose tolerance test result showing fasting blood glucose of >5.6 and/or post prandial of >7.8 at 120 mins) hospital admission, postpartum haemorrhage (PPH >500 mL)18 and mode of birth were also recorded.

Data were gathered on variables available during decision to allocate the women to caseload or traditional care from self and GP referral forms submitted. This included maternal history of need for interpreter services, learning disability, hearing or sight problems, assisted conception, birth location preference, history of previous live children, preterm births, miscarriages, ectopic pregnancies, stillbirths and NND, previous caesarean or assisted birth, thalassaemia or sickle disease, respiratory, diabetic, cardiac, hypertension, renal, liver, neurological or infectious diseases, history of substance abuse, domestic violence, safeguarding issues and women with the status of refugee or asylum seeker. These questions were ‘yes/no’ on the self-referral form with an opportunity for free text included. On the GP referral if any information was not included, it was assumed to be negative (as this was the information available to the triaging midwife).

Data collection was confidential and adhered to the Kings College London Research Data Management Policy standards.

Analysis

Three separate groups were analysed:

LEAP area women allocated to caseload midwifery care.

LEAP area women allocated to traditional care.

Non-LEAP area women (mix of above care models).

Missing documentation was reported and included in statistical analysis. Neonatal outcomes outside the data collection period were not included.

IMD scores and quintiIes were derived from patient postcodes using the National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit tool.19 Data collection began in 2018, but 2019 IMD data were used in significance analysis20 (rather than 2015), as likely to be most accurately representative of patient circumstance. They are reported in quintiles (rather than deciles) to simplify interpretation.

In this paper, a large group of people are grouped under the umbrella term ‘black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME)’, to enable us to quantify and target outcome inequality, rather than ignorance of the diversity within that label. It should not imply uniformity of experience within these communities and does not include white minority communities that may also experience inequality in this instance.

A total of 164 women who had no referral form, for the purpose of analysis, were assumed to be triaged at their booking visit and were included in absolute numbers but excluded from significance analysis. Information in the questionnaire relevant to the decision to allocate to caseload midwifery care was analysed by logistic regression. Adjustment was made for these differences by the inverse probability weighting method21 to identify and correct the most important sources of bias (see table 2). The inverse probability weightings were based on the four strongest predictors in the questionnaire of a decision to caseload: unknown ethnicity, breathing problems, need for an interpreter, and previous delivery by Ventouse. Probabilities were first calculated using logistic regression, and the weighting calculated for each woman as 1/(probability of caseload care) in those allocated to caseload care; and 1/(probability of not caseload care) in the other participants. Subgroup analysis was preformed according to ethnicity and IMD score. Significance analysis was performed by a statistician using Stata version 17 statistical package. Significance analysis performed adjusting for those whose continuity was interrupted due to service disruption for example, staffing and COVID-19, did not affect our results, however, we report the whole dataset as intention to treat analysis.

Table 2.

Decision to caseload from booking survey

| Variable reported | Caseload midwifery | Traditional care | Unadjusted risk ratio (95% CI) | P value |

| Interpreter needed | 20/165 (12.1%) | 9/210 (4.3%) | 2.83 (1.32 to 6.05) | 0.005 |

| Unknown ethnicity | 29/165 (17.6%) | 57/210 (27.1%) | 0.65 (0.43 to 0.96) | 0.029 |

| Respiratory comorbidity | 10/165 (6.1%) | 26/210 (12.4%) | 0.49 (0.24 to 0.99) | 0.039 |

| Previous instrumental birth | 13/165 (7.9%) | 8/210 (3.8%) | 2.07 (0.88 to 4.87) | 0.089 |

Summary of significant and important factors that were corrected for by inverse probability weighting in statistical analysis. (Women who did not complete a booking survey excluded as interview allocation subject to bias).

Patient and public involvement engagement statement

No women were directly involved in the design, conduct, reporting or dissemination plans of this observational study. However, the research question was stimulated by the leading request of women in the Better Births22 report for continuity of care, and the increasing public consciousness and protest to inequality, including the black Lives Matter movement. LEAP Lambeth has parent representatives who feedback regarding early years services to local stakeholders.

Dissemination declaration

The study findings will be disseminated to local women through the hospital and university websites, seminars and participant engagement events, NIHR ARC South London patient and public involvement engagement group and conferences.

Results

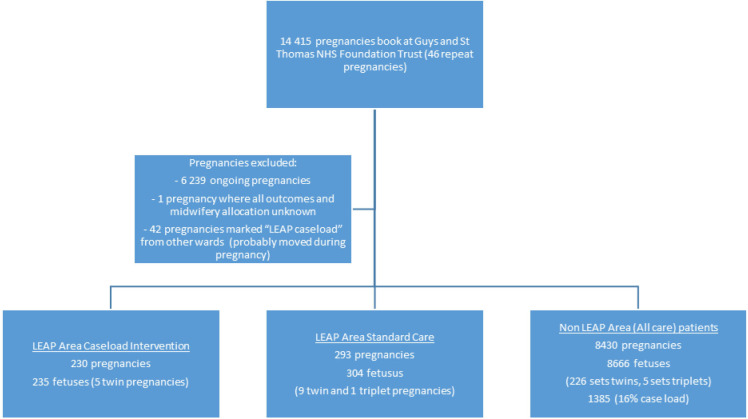

A total of 14 415 pregnancies booked at Guys and St Thomas’ foundation trust in the study period (11 July 2018 to 18 June 2020). We excluded 6239 ongoing pregnancies, 1 where no midwifery allocation or outcomes were known and 42 pregnancies recorded as LEAP caseload midwifery care, but from other geographical areas (possibly explained by women moving home during pregnancy) (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Allocation of women booking at Guys and St Thomas’ foundation trust to antenatal care groups for purposes of data analysis. LEAP, Lambeth Early Action Partnership; NHS, National Health Service.

There were a total of 523 pregnancies in women in the LEAP area. Of these, 230 pregnancies (44%) were allocated to caseload midwifery and resulted in 235 fetuses (5 twin pregnancies). A total of 293 pregnancies were allocated to traditional care and resulted in 304 fetuses (9 twin, 1 triplet pregnancy). There were a total of 8430 pregnancies from non-LEAP areas which resulted in 8666 fetuses (226 sets of twins, 5 sets of triplets). Of these, 1385 (16.4%) were allocated to caseload midwifery (non-LEAP team). Forty-six women had a second pregnancy during the study period, one of which was a twin pregnancy. All were included (figure 1).

Statistical analysis into decision for caseload midwifery was performed on information available at allocation, that is, data from referral forms. Significant factors that were identified from referral forms in the LEAP area women were women, who needed an interpreter, of unknown ethnicity, with respiratory comorbidity and previous instrumental birth (table 2) and adjusted for in significance analysis. Multifetal pregnancy was not a statistically significant factor in decision making.

Demographics and modifiable lifestyle related risk factors

The LEAP area had a higher representation of black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) women than in other postal code areas (eg, black ethnicity: 27.8% vs 17.2%) and higher levels of deprivation (IMD quintile 5: 55.6% vs 28.0%) (table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of ethnic diversity and IMD scores in LEAP area women allocated to caseload midwifery and traditional care, and women in other postal code areas (all care models)

| Other areas | LEAP area caseload midwifery | LEAP area traditional care | ||||

| Ethnicity | N 8430 |

(%) | N (230) |

(%) | N (293) |

(%) |

| White (British, Irish, other) | 4030 | 47.8 | 81 | 35.2 | 98 | 33.4 |

| Black (African, Caribbean, other) | 1452 | 17.2 | 66 | 28.7 | 79 | 27.0 |

| Asian (including Bangladeshi, Indian, Pakistani, Asian other) | 638 | 7.6 | 6 | 2.6 | 11 | 3.8 |

| Chinese | 200 | 2.4 | 3 | 1.3 | 2 | 0.7 |

| Mixed (including white-black, white-Asian, mixed other) | 357 | 4.2 | 14 | 6.1 | 16 | 5.5 |

| Other ethnic group | 536 | 6.4 | 21 | 9.1 | 17 | 5.8 |

| Not recorded | 1253 | 14.9 | 39 | 17.0 | 70 | 23.9 |

| IMD quintile | ||||||

| 1 (least deprived) | 241 | 2.9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 528 | 6.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 1151 | 13.7 | 3 | 1.3 | 4 | 1.4 |

| 4 | 3288 | 39.0 | 89 | 38.7 | 105 | 35.8 |

| 5 (most deprived) | 2361 | 28.0 | 121 | 52.6 | 170 | 58.0 |

| Unknown | 861 | 10.2 | 17 | 7.4 | 14 | 4.8 |

IMD, Index of Multiple Deprivation; LEAP, Lambeth Early Action Partnership.

The LEAP area also had a higher proportion of single women (35.2% vs 27.0%), teenage women (3.6% vs 1.3%), women who were smokers at time of birth (4.2% vs 2.8%) and obesity (19.5% vs 14.4%) than other areas (table 4).

Table 4.

Risk factors relating to pregnancy in women in the LEAP area allocated to case load midwifery and traditional care, and women in other postal code areas

| Other areas | LEAP area caseload midwifery | LEAP area traditional care | ||||

| N 8430 | % | N 230 | % | N 293 | % | |

| Smoker at booking | 324 | 3.8 | 14 | 6.0 | 10 | 3.4 |

| Non-smoker at booking | 7767 | 92.1 | 207 | 90.0 | 274 | 93.5 |

| Status not recorded at booking | 339 | 4.0 | 9 | 3.9 | 9 | 3.1 |

| Smoker at time of birth | 233 | 2.8 | 14 | 6.0 | 8 | 2.7 |

| Non smoker at time of birth | 7899 | 93.7 | 206 | 89.6 | 267 | 91.1 |

| Status not recorded at time of birth | 298 | 3.6 | 10 | 4.3 | 18 | 6.1 |

| Age </+19 | 112 | 1.3 | 13 | 5.7 | 6 | 2.0 |

| Age >/=40 | 738 | 8.8 | 14 | 6.1 | 19 | 6.5 |

| Age not recorded | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Single/separated/divorced/widowed | 2276 | 27.0 | 87 | 37.8 | 97 | 33.1 |

| Married/cohabiting/partner | 4863 | 57.7 | 114 | 49.6 | 146 | 49.8 |

| Relationship status not recorded | 1291 | 15.3 | 29 | 12.6 | 50 | 17.1 |

| BMI 30–39 (all ethnicities) | 1213 | 14.4 | 47 | 20.4 | 55 | 18.8 |

| BMI >40 (all ethnicities) | 145 | 1.7 | 1 | 0.4 | 10 | 3.4 |

| BMI not recorded | 624 | 7.4 | 30 | 13.0 | 22 | 7.5 |

| BMI 23–27.49 and BAME population | 985 | 11.6 | 29 | 12.6 | 33 | 11.3 |

| BMI >27.5 and BAME population | 1054 | 12.5 | 37 | 16.1 | 50 | 17.1 |

BAME, black, Asian and minority ethnic; BMI, body mass index; LEAP, Lambeth Early Action Partnership.

Maternal outcomes

Primary outcome (mode of birth) in the LEAP area

Both elective and emergency CS rates were higher in the LEAP area women who received traditional care (16.3% and 22.5%, respectively) compared with other areas. The LEAP area women allocated to caseload midwifery care, when compared with traditional care, had significantly reduced total CS (38.9 vs 24.3%; risk ratio: 0.65, p=0.01, 95% CI 0.47 to 0.90, number needed to treat: 7.4) and emergency CS (22.5 vs 15.2%; risk ratio: 0.59, p=0.03; 95% CI 0.38 to 0.94; number needed to treat: 10) (table 5).

Table 5.

Maternal outcomes in LEAP area women allocated to caseload midwifery and traditional care and women in other postal code

| Other areas | LEAP area caseload midwifery | LEAP area traditional care | Comparison of caseload midwifery and traditional care in LEAP area* | ||||

| N 8430 (%) | N 230 (%) | N 293 (%) | Risk ratio (95% CI) | Interaction test P value |

Risk difference | No needed to treat† | |

| Mode of birth | |||||||

| Any caesarean section | 3061 (36.3) | 56 (24.3) | 114 (38.9) | 0.65 (0.47 to 0.90) | 0.01 | −0.14 | 7.4 |

| Elective caesarean | 1317 (15.6) | 21 (9.1) | 48 (16.3) | ||||

| Emergency caesarean | 1744 20.7) | 35 (15.2) | 66 (22.5) | 0.59 (0.38 to 0.94) | 0.03 | −0.11 | 10 |

| Assisted vaginal birth (forceps/ventouse) | 1205 (14.3) | 34 (14.8) | 31 (10.6) | ||||

| Normal vaginal birth | 4035 (47.9) | 138 (60) | 143 (48.8) | ||||

| Breech vaginal | 43 (0.5) | 2 (0.9) | 2 (0.7) | ||||

| Unknown | 86 (1.0) | 0 (0) | 3 (1.0) | ||||

| Gestational diabetes | 960 (11.4) | 22 (9.6) | 29 (9.9) | ||||

| Pregnancy induced hypertension | 141 (1.7) | 3 (1.3) | 8 (2.7) | ||||

| Pre-eclampsia | 205 (2.4) | 5 (2.2) | 7 (2.4) | ||||

| Postpartum haemorrhage (>501 mL) | 3289 (39.0) | 67 (29.1) | 111 (37.8) | 0.77 (0.57 to 1.04) | 0.10 | −0.09 | 11.6 |

| Inpatient admission | |||||||

| <24 hours | 1148 (13.6) | 27 (11.1) | 38 (13.0) | ||||

| >5 days (121 hours) | 1387 (16.5) | 32 (13.9) | 41 (14.0) | ||||

| Admission not documented | 120 (1.4) | 5 (2.2) | 5 (1.7) | ||||

*Comparisons carried out using inverse probability weighting to minimise potential bias.

†NNT: Number of women who need to be treated to prevent one bad outcome.

LEAP, Lambeth Early Action Partnership.

Subanalysis into vulnerability in the LEAP area

BAME population

There was a significant difference in the CS rate in those allocated to case load midwifery, compared with those allocated to traditional care. In BAME women, the total rate of CS was significantly reduced in those allocated to caseload midwifery compared with those allocated to traditional care (27.8% vs 43.1%; risk ratio: 0.68; p=0.04; 95% CI 0.47 to 0.99). The statistical significance was similar in white mothers (24.7% vs 39.8%; risk ratio: 0.63; p=0.04; 95% CI 0.40 to 0.99), but the caesarean rate was higher overall in BAME women. The trend reduction in women allocated to caseload midwifery compared with those allocated to traditional care on emergency caesarean was more marked in BAME women (15.7% vs 26.2%) than white women (16% vs 20.4%) but did not reach statistical significance in small numbers. (p=0.10; 95% CI 0.38 to 1.08 in BAME women) (table 6).

Table 6.

Comparison of primary maternal and newborn outcomes in the LEAP area following introduction of caseload midwifery in women of White and women of BAME ethnicity

| White ethnicity caseload midwifery | White ethnicity traditional care | Comparison of caseload midwifery and traditional care in LEAP area* | BAME ethnicity caseload midwifery | BAME ethnicity traditional care | Comparison of caseload midwifery and traditional care in LEAP area* | |||

| Risk ratio (95% CI) | P value | Risk ratio (95% CI) |

P value | |||||

| Maternal outcomes | ||||||||

| Any caesarean section | 24.7% | 39.8% | 0.63 (0.40 to 0.99) | 0.04 | 27.8% | 43.1% | 0.68 (0.47 to 0.99) | 0.04 |

| Emergency caesarean section | 16.0% | 20.4% | 0.76 (0.42 to 1.44) | 0.42 | 15.7% | 26.2% | 0.64 (0.38 to 1.08) | 0.10 |

| Neonatal outcomes | ||||||||

| Birth before 37 weeks | 2.5% | 5.1% | 0.45 (0.08 to 2.31) | 0.23 | 7.3% | 14.4% | 0.49 (0.21 to 1.09) | 0.08 |

| Birth before 34 weeks | 1.2% | 2.0% | 0.66 (0.07 to 7.2) | 0.7 | 1.8% | 7.2% | 0.24 (0.05 to 1.12) | 0.07 |

*Comparisons carried out using inverse probability weighting to minimise potential bias.

LEAP, Lambeth Early Action Partnership.

IMD quintile 5

The overall rate of CS was higher in women in IMD 5 compared with others (third and fourth quintiles combined) (30.3% vs 24.6%), and the rate of emergency CS was higher (21.2% vs 11.4%). The trend in emergency CS reduction in women allocated to caseload midwifery compared with traditional care in IMD 5 is more marked (24.1% vs 17.8%) than in IMD other (12.9% vs 9.8%) but did not reach statistical significance (risk ratio 0.75; p=0.47; 95% CI 0.34 to 1.65). This trend was not observed for reduction in total CS rate.

Women who needed an interpreter

There was a statistically significant decrease in emergency CS in women allocated to caseload midwifery compared with traditional care (5.0% (1/20) vs 50.0% (4/8)); risk ratio 0.10; p=0.03; 95% CI 0.01 to 0.75). There was a non-statistically significant reduction in total CS (30% vs 50%; risk ratio: 0.57; p=0.28; 95% CI 0.21 to 1.59).

Teenage women

In the LEAP area, none of the 13 teenage women allocated to caseload midwifery had a CS (0/13). Thirty-three per cent (2/6) of teenage women allocated to traditional midwifery had an emergency CS.

Multifetal pregnancy

In women allocated to caseload midwifery 4/10 (40%) of twin babies were born by elective CS, 1/10 (10%) by emergency caesarean and 5/10 (50%) vaginally. In women allocated to traditional care 11/21 (52.4%) babies were born by elective caesarean, 4/21 (19.0%) by emergency caesarean and 6/21 (28.6%) vaginally. Numbers of multifetal pregnancies were small and the impact of caseload midwifery in multifetal pregnancies was similar to singleton in total CS (multifetal risk ratio: 0.57 and singleton risk ratio: 0.65). This reduction remains significant when multifetal excluded (p=0.01; 95% CI 0.47 to 0.91). Reduction in emergency CS in those allocated to caseload midwifery compared with traditional care was also comparable in multifetal and singleton pregnancies (multifetal risk ratio: 0.39 and singleton risk ratio: 0.62). Reduction in emergency caesarean remains significant when multifetal excluded p=0.04; 95% CI 0.39 to 0.98).

Previous caesarean birth

In women allocated to traditional care, more had a history of previous caesarean birth than in women allocated caseload midwifery (20.1% vs 14.0%). When mode of delivery was analysed separately in women who had had a CS in a previous pregnancy, the rate of any caesarean birth in women receiving caseload midwifery compared with traditional care (66.7 vs 72.5%; risk ratio: 0.96; p=0.8; 95% CI 0.60 to 1.5; risk difference: −0.03; number needed to treat: 35.9), did not reach significant difference. Furthermore, the rate of emergency cs was higher in the caseload group (27.3% vs 25.0%). However, analysis of mode of delivery in women with no history of previous cs, found the rate of any cs birth was significantly less in the women allocated to caseload midwifery compared with traditional care (17.9% vs 32.1%; risk ratio: 0.54; p=0.004; 95% CI 0.35 to 0.82; risk difference: 0.16; number needed to treat: 6.2), as was the rate of emergency cs (12.9% vs 21.8%; risk ratio: 0.58; p=0.04; 95% CI 0.36 to 0.96; risk difference: 0.10; number needed to treat: 9.6), Interaction test suggests that while the effect of caseload midwifery on mode of delivery is strong in women without previous CS, there is no clear evidence for women with previous CS.

Secondary outcomes

Numbers reported for GDM and hypertensive disease were small, with no significant difference observed (table 5). PPH was lower by 8.7% in women allocated to caseload midwifery compared with traditional care, but this did not reach statistical significance (risk ratio: 0.77; p=0.10; 95% CI 0.57 to 1.04; number needed to treat: 11.6).

Newborn outcomes in LEAP area women

Primary outcomes (preterm birth)

Preterm birth rate was reduced in women allocated to caseload midwifery before 37 weeks, before 34 weeks and before 24 weeks gestation relative to traditional care. This was statistically significant in births before 37 weeks (5.1% vs 11.2%; risk ratio: 0.41, p=0.02; 95% CI 0.18 to 0.86, number needed to treat: 11.9). There was a trend towards reduction in preterm birth before 34 weeks (1.7% vs 4.3%) which did not reach statistical significance in our small cohort (risk ratio 0.35; p=0.11; 95% CI 0.97 to 1.28; number needed to treat: 27.7). There were no previable preterm births in the caseload midwifery group (table 7).

Table 7.

Newborn outcomes in LEAP and non-LEAP areas following the introduction of LEAP case-loading intervention

| Outcome | Other areas | LEAP area caseload midwifery | LEAP area traditional care | Comparison of caseload midwifery and traditional care in LEAP area* | |||

| N 8666 (%) |

N 235 (%) |

N 304 (%) |

Risk ratio (95% CI) | Interaction test P value |

Risk difference | NNT† | |

| Stillbirth | 37 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||||

| Neonatal death | 59 (0.7) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.3) | ||||

| Non-registerable birth | 106 (1.2) |

0 (0) | 3 (1.0) | ||||

| Not recorded | 1 (0.01) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||||

| Neonatal unit (NNU) admission | 889 (10.3) | 19 (8.1) | 34 (11.1) | ||||

| Not documented if NNU admission | 1 (0.01) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||||

| Apgar score <7 (1 min) | 15 (6.4%) | 27 (8.9%) | 0.68 (0.35 to 1.33) | 0.26 | −0.04 | ||

| Apgar <7 (5 min) | 6 (2.6%) | 3 (1.0%) | 3.9 (0.79 to 19.3) | 0.10 | 0.03 | ||

| Apgar not fully recorded | 5 (2.1%) | 8 (2.6%) | |||||

| All births <37 weeks | 912 (10.5) | 12 (5.1) | 34 (11.2) | 0.41 (0.18 to 0.86) | 0.02 | −0.07 | 11.9 |

| All births <34 weeks | 417 (4.8) | 4 (1.7) | 13 (4.3) | 0.35 (0.97 to 1.28) | 0.11 | −0.04 | 27.7 |

| Birth 12–23+6 weeks | 134 (1.5) | 0 (0) | 4 (1.3) | ||||

| Birth 24–33+6 weeks | 283 (3.3) | 4 (1.7) | 9 (3.0) | ||||

| Birth 34–36+6 weeks | 495 (5.7) | 8 (3.4) | 21 (6.9) | ||||

| Gestation of birth not recorded | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||||

| Birth weight <2.5 kg | 967 (11.1) | 17 (7.2) | 37 (12.2) | 0.77 (0.24 to 1.08) | 0.08 | −0.07 | 15.2 |

| Birth weight >4.5 kgs | 60 (0.7) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.3) | ||||

| Birth weight not recorded | 2 (0.02) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||||

| Breastfed (at all) | 7832 (90.4) | 221 (94.0) | 281 (92.4) | 1.04 (0.97 to 1.11) | 0.29 | 0.03 | 30.9 |

| Not recorded if breastfed | 214 (2.5) | 0 (0) | 4 (1.3) | ||||

| Skin to skin within 1 hour | 5827 (67.2) | 176 (74.9) | 203 (66.8) | 1.12 (0.98 to 1.30) | 0.09 | 0.09 | 11.7 |

*Comparisons carried out using inverse probability weighting to minimise potential bias.

†NNT: Number of women who need to be treated to prevent one bad outcome.

BAME, black, Asian and minority ethnic; LEAP, Lambeth Early Action Partnership.

Sub analysis into vulnerability in the LEAP area

BAME population

Preterm births were reduced by approximately half in BAME women (14.4%–7.3%) and white women (5.1%–2.5%) who were allocated to caseload midwifery compared with traditional care. This highlights higher absolute numbers of preterm births in BAME women. There was a more marked trend in reduction in births under 34 weeks in BAME women (7.2%–1.8%) compared with white women (2.0%–1.2%) in those allocated to caseload midwifery compared with traditional care. (table 6)

IMD quintile 5

When women in IMD quintile 5 were compared with other IMD quintiles (quintiles 3 and 4) there were higher rates of premature births overall (7.0% vs 4.2%). In IMD 5 mothers, births before 37 weeks were reduced by almost half in women allocated to midwifery compared with traditional care (4.4% vs 9.1%; risk ratio 0.48; p=0.37; 95% CI 0.10 to 2.39) compared with a smaller trend reduction in IMD 4 women (3.7% vs 4.7%).

Women who needed an interpreter

There was a statistically significant reduction in preterm birth rate (before 37 weeks) in those allocated to caseload midwifery compared with traditional care (5.3% vs 44.4%; risk ratio: 0.11; p=0.03; 95% CI 0.01 to 0.83). The impact was more marked than in those not needing an interpreter (5.6% vs 9.2%). There was a statistically significant reduction in preterm birth before 34 weeks in those exposed to caseload midwifery compared with traditional care (0% vs 22.2%; risk ratio: 0.25; p=0.03; 95% CI 0.07 to 0.87), which was more marked compared with those not needing an interpreter (2.1% vs 4.1%).

Teenage women

There was only one case of preterm birth in teenage women.

Mutifetal pregnancy

In women allocated to caseload midwifery 20% (2/10) twins were born before 37 weeks and none (0/10) before 34 weeks. In women allocated to traditional care 52.4% (11/21) babies were born before 37 weeks and none before 34 weeks (0/21). There were more multifetal pregnancies in the traditional care group, however, the trend reduction in those allocated to caseload midwifery was comparable in singleton (risk ratio 0.49) and multifetal pregnancies (risk ratio 0.21).

Secondary outcomes

In non-LEAP areas, pregnancy resulted in stillbirth in 0.4% of pregnancies, NND in 0.7%, and non-registerable death (pre-viable) in 1.2%. In the LEAP area there were no recorded stillbirths or NND in women allocated to caseload midwifery. There was one NND in women allocated to traditional care (table 7).

Low birth weight (<2.5 kg)

In LEAP area women allocated to caseload midwifery there was a trend reduction in low birth weight compared with those allocated to traditional care (7.2% vs 12.2%; risk ratio: 0.77; p=0.08; 95% CI 0.24 to 1.08; number needed to treat: 15.2) (table 7).

Neonatal unit admission

In LEAP area women allocated to caseload midwifery there was a trend reduction in neonatal unit (NNU) admission compared with those allocated to traditional care (8.1% vs 11.1%) (table 7).

APGAR scores

There was no significant difference APGAR scores at 1 min less than 7 or APGAR scores at 5 min less than 7 (table 7).

Breastfeeding rates

In LEAP area women allocated to caseload midwifery there was a trend increase in breast feeding compared with those allocated to traditional care (94.0% vs 92.4%; risk ratio: 1.04; p=0.29; 95% CI 0.97 to 1.1) (table 7).

Skin to skin

In LEAP area women allocated to caseload midwifery, there was a trend increase in skin to skin contact within 1 hour compared with traditional care (66.8% vs 74.9%; p=0.09: 95% CI 0.98 to 1.3; number needed to treat: 11.7) (table 7).

Discussion

Principal findings

This study shows that caseload midwifery implemented in a deprived inner city community improves outcomes by significantly reducing preterm births and birth by CS, without increasing NNU admission or stillbirth. The data also suggest that caseload midwifery had the greatest impact in the highest risk populations (mothers in higher IMD quintiles and from BAME backgrounds). In small numbers, our data are suggestive of reduction in low birthweight infants, PPH, pregnancy-induced hypertension and pre-eclampsia, birth before 34 weeks, previable birth, NNU admission and NND with improved breast feeding and skin-to-skin contact. No difference was observed in GDM and macrosomia.

This study is important due to the potential impact of reducing preterm birth and caesarean rates in vulnerable women and addressing inequality and inequity at birth. Historically, attempts at reducing preterm labour and caesarean birth have been extensive but with limited impact,23 24 and there are valid concerns regarding safety of reducing caesarean births.25 Caseload midwifery, already shown to be acceptable26 and beneficial,14 is not yet standard for all women in the UK (although targeted continuity of midwifery care to BAME and groups and women in living in deprived areas is an NHS Long Term Plan commitments).27 This may be due to the incomplete understanding of the mechanism of improvement, and the enormity of the task of restructuring a care pathway. By reporting in a targeted group, we can suggest a hopeful starting point for change.

Strengths

This was a pragmatic study that included twin and triplet pregnancies, repeat pregnancies and women with complex medical and obstetric histories, often excluded from other studies. It analysed a programme of care that has been shown to work in practice in a socially deprived area, rather than recruiting to a research study intervention. We used intention-to-treat analysis where continuity was affected by provider circumstantial limitations, thus, results reflect the reality of intervention in a non-study clinical practice.

Limitations

As a cohort study, and not a randomised controlled trial (RCT), it contains all the limitations of such a design. There may be potential confounders in caseload allocation and outcome which may bias our results. However, women allocated to the caseload midwifery care are anticipated to be at higher risk of adverse outcomes and hence allocated thus, making the improvements demonstrated in their outcomes potentially more significant. The small numbers in less common outcomes (eg, stillbirth and NND), allow trends to be only cautiously highlighted. NND outside the data collection period may have occurred in all groups, although numbers are likely to be small. We included multifetal pregnancies because we observed the same trend in main outcomes by caseload midwifery care as in singleton, but it must be considered as a potential confounder. Staffing and COVID-19 disrupted some aspects of continuity. We did not include economic analysis.

Comparison to other studies

To our knowledge, this study is the first to focus on targeting care for vulnerable women based on IMD score and ethnicity, and so is not directly comparable to other studies reporting outcomes of caseload midwifery. Unlike some studies, we did not exclude women with medical/obstetric complications. A Cochrane review of available evidence prior to 201614 showed continuity (including caseload midwifery), when compared with standard care, reduced preterm birth (average risk ratio (aRR)=0.7), but did not reduce caesarean birth, despite a higher vaginal birth rate (aRR=1.05).14 Our study showed significant reduction in birth before 37 weeks (risk ratio: 0.41) and all caesarean and emergency caesarean birth rate (risk ratio 0.65 and 0.59, respectively). The POPPIE (Pilot study Of midwifery Practice in Preterm birth Including women's Experiences) pilot RCT (2020) of women at high risk for preterm birth found midwifery continuity of care did not significantly impact gestation or mode of birth.28 A prospective cohort study comparing caseload midwifery to standard care in an aboriginal population in Australia, however, found the odds ratio (OR) of preterm birth to be 0.57.29 A retrospective cohort study of caseload midwifery in vulnerable women with complex social factors in London found a similar reduction in CS (relative risk total caesarean: 0.51 and emergency caesarean: 0.42) and enhanced multidisciplinary support.30 A previous descriptive analysis of caseload midwifery care in a London population (who were ethnically diversity with high levels of social deprivation), also found low caesarean birth rates of 16%.31

Meaning of the study: Due to these varied outcomes, previous study findings suggest a need to consider appropriate targeting and the mechanism of action of caseload care. We need to consider why our study found a reduction in caesarean birth (and so markedly so), why the impact in preterm birth before 37 weeks appears bigger (aRR=0.45) and why our high-risk group responded so differently from those in the POPPIE trial?

The intervention at the crux of caseload midwifery care is providing time, continuity and communication.32–34 Time with a women, to build trust and rapport,35 to observe a woman’s surroundings and assess what risks have not been verbalised, to establish solutions that tailor into a woman’s framework and community.36 37

In the POPPIE pilot trial, high risk was identified by history, but also by structural abnormalities and smoking.28 This is testament to the heterogenicity of preterm labour aetiology,23 and so the solution must also be multifaceted and patient centred. There was minimal change in smoking behaviour in our caseload group. A link between a continuity-based intervention and structural adaptation (ie, cervix and uterine abnormalities) is not known. Furthermore, continuity was often in a hospital, rather than a community-based setting (like in this study), the importance of which is currently under research.

Mechanisms of spontaneous preterm labour include the premature triggering of the hypothalamic–pituitary axis of the fetus, inflammation, matrix remodelling, abruption of the placenta and mechanical stretch.38 39 Stress response is incompletely realised, but can physiologically manifest as an endocrine and/or a proinflammatory response.40 41 Pregnancy is a state of relatively reduced systemic cortisol and inflammatory cytokines, however, acute and less acute psychosocial stressors in pregnancy can counteract this, and even modulate the development of the fetus’ hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis.40 Stress affects maternal health behaviours such as diet, sleep and exercise, it reduces the effectiveness of the maternal immune response, and it exacerbates mental illness such as anxiety and depression.40 These stimuli have been shown to have impact early in pregnancy41 and so must be tackled early.

If evidence exists that psychosocial stress and its associated effects, are linked to preterm labour and low birth weight,41 it is intuitive to imagine that early impact on these stressors (when the physiological adaptation to pregnancy is so marked and rapid structural and functional development of the fetus is taking place) could be integral to improving outcome. One aspect of caseload midwifery care, is time to identify need for, and access social support services relative to other traditional care.30 If a multiagency referral is completed early, from the first trimester, the potential burden of anxiety around visa status, housing, finances etc (that may be heightened by the impending addition of a new child) may be lightened. Intimate partner violence support, and potential freedom from financial abuse can impact both the stress response and the physical abruption risk associated with preterm labour. This information may come to light in person, rather than with questionnaire screening, which is why early identification of risk and flexible allocation to caseload midwifery may be important.

From a longer-term perspective, maternal stressors on the fetus in utero have been linked to neurodevelopmental disorders in children.42 Preterm birth is associated with anxiety and depression long beyond the perinatal period in caregivers and bonding difficulties in those admitted to NNU (greater at earlier gestations).43–45 A later gestation of birth may avoid a financial implication to the parents and the healthcare system in early years46 and in adult hood with reduced disability, chronic illness and increased educational attainment in children born closer to term.47

CS is a life-saving intervention. Targeting lower rates may be detrimental to women's care,25 but rates above 9%–16%48 have minimal proven benefit, with negative maternal and neonatal consequences.49 A systematic review has not reported lower caesarean rate to be associated with caseload midwifery.14 However, deprivation is associated with unplanned CS. Our cohort population, diverse and socioeconomically deprived, are vulnerable to lack of clear communication and failed engagement with services.50 The impact of communication is clearly illustrated by the risk ratio of 0.10 of CS in mothers who need an interpreter.

It could be anticipated that more and longer antenatal appointments, with continuity of the healthcare professional may have more impact. Opportunities to address fears regarding labour may reduce antenatal motivation for caesarean birth. Identification of a healthy support structure in labour, may be aided by enhanced knowledge of the family dynamics, through appointments in the family home and prolonged rapport with women. Discussion around women’s expectations of what is a normal labour, may impower women in their birth support and analgesia options. A known carer may enhance support to execute birth plans, thereby improving motivation in labour to pursue vaginal birth. Benefits of a vaginal birth extend from the women to health economics, reducing need for additional antenatal appointments, a lower-cost labour location and reduced CS in the next pregnancy.51 Our results may differ from the POPPIE trial, due to a higher representation of BAME women (in POPPIE trial 58.6% were white vs 34% in LEAP area women) and women affected by deprivation (over 93% of LEAP area women in the two most deprived IMD quintiles vs 70% in the POPPIE trial).

Future research

Further research is needed to determine whether the significant improvement seen, will translate to other inner city populations with similar demographics. Long-term follow-up of these women would determine whether there are long-term clinical and economic benefits of caseload midwifery in this population. Further research is needed into the effectiveness of continuity of care in a hospital-based setting for those with high medical obstetric risk.

Conclusion

Before the umbilical cord is cut, paths for inequality in health outcomes have begun and are marked in communities of high socioeconomic deprivation and ethnic diversity.

Justice and equality should be a priority in any healthcare setting, and caseload midwifery, may be a part of the solution. Recognising resource limitations, this study demonstrates for the first time how targeting disadvantaged inner city communities may have the most marked effect in reduction of preterm labour before 37 weeks, all caesarean birth (and emergency caesarean birth) and their subsequent impact.

Further research is needed into the generalisability of this approach in other populations and into its impact on health economics is required. Long-term follow-up of these patients is planned.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Clare White, Anne Kerrigan, Rachel Erskine and Emily Miller for their thoughtful comments on improving how we communicate to the reader and editing previous drafts. We thank the caseload midwives, in particular the LEAP team, for their ongoing care of women. Most importantly, we thank the women whose experience we have been able to learn from.

Footnotes

Contributors: EO-N conceived the presented study, organised outcome data extraction, methodology and verified the data analysis. He cowrote the manuscript, approved the final draft and is responsible for the overall content and guarantor for the study. RLH was lead in curation and analysis of the main data and was lead author of the original draft manuscript. Responsible for incorporating content from coauthors, and for the overall content of the manuscript. PS performed statistical analysis of main results. He guided methodology and performed statistical adjustment for data confounders. He supported review and editing of the manuscript. DE, KH, SM and SO curated data regarding women’s allocation to caseload midwifery. They reviewed and edited the manuscript. CFT, CS, MB and JS reviewed and edited the manuscript, providing expertise on interpretation of the data set, and clinical application to bettering women’s health. NK provided expertise in the study conception.

Funding: The Lambeth Early Action Partnership (LEAP) programme is a 10-year programme that works with pregnant women and children aged 0–3 years and their families and aims to give them a better start. LEAP received £36 million from the National Lottery Community Fund as part of the national ‘A Better Start programme.’ Part of this programme includes caseload midwifery. The majority, but not all women allocated to caseload midwifery were cared for by this team. No funding was received specifically for this study. Jane Sandall at King’s College is an NIHR Senior Investigator and with Cristina Fernandez Turienzo are supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Applied Research Collaboration South London (NIHR ARC South London) at King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust.

Disclaimer: The funders had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, writing of the report, or the decision to submit the paper for publication. The views expressed are those of the author[s] and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request. The complete deidentified patient data set and analytical/Statistical code will be available on request form the corresponding author ruth.hadebe@nhs.net from date of publication.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval was granted by the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine Ethics committee. The study was based on routinely collected hospital data. Individual patient consent was not obtained; all patient records were anonymised and deidentified prior to analysis.

References

- 1.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence . Pregnant women with complex social factors: a model for service provision. Available: www.nice.org.uk [PubMed]

- 2.MBRRACE-UK perinatal mortality surveillance report. UK perinatal deaths for births from January to December 2016, 2018. Available: https://www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/downloads/files/mbrrace-uk/reports/MBRRACE-UK

- 3.Taylor-Robinson D, Agarwal U, Diggle PJ, et al. Quantifying the impact of deprivation on preterm births: a retrospective cohort study. PLoS One 2011;6:e23163. 10.1371/journal.pone.0023163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ene D, Der G, Fletcher-Watson S, et al. Associations of socioeconomic deprivation and preterm birth with speech, language, and communication concerns among children aged 27 to 30 months. JAMA Netw Open 2019;2:e1911027. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.11027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beauregard JL, Drews-Botsch C, Sales JM, et al. Preterm birth, poverty, and cognitive development. Pediatrics 2018;141:e20170509. 10.1542/peds.2017-0509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henderson J, Carson C, Redshaw M. Impact of preterm birth on maternal well-being and women's perceptions of their baby: a population-based survey. BMJ Open 2016;6:e012676. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MBRRACE-UK . Saving lives, improving mothers’ care, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health . Saving mothers lives: reviewing maternal deaths to make motherhood safer, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lindquist A, Kurinczuk JJ, Redshaw M, et al. Experiences, utilisation and outcomes of maternity care in England among women from different socio-economic groups: findings from the 2010 national maternity survey. BJOG 2015;122:1610–7. 10.1111/1471-0528.13059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conti G, Heckman J, Pinto R. The effects of two influential early childhood interventions on health and healthy behaviour. Econ J 2016;126:F28–65. 10.1111/ecoj.12420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute . The Abecedarian project. Available: https://abc.fpg.unc.edu/abecedarian-project

- 12.Barnett WS, Masse LN. Comparative benefit–cost analysis of the Abecedarian program and its policy implications. Econ Educ Rev 2007;26:113–25. 10.1016/j.econedurev.2005.10.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Health Matters:giving every child the best start in life, 2016. Available: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/health-matters-giving-every-child-the-best-start-in-life/health-matters-giving-every-child-the-best-start-in-life

- 14.Sandall J, Soltani H, Gates S, et al. Midwife-led continuity models versus other models of care for childbearing women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;4:CD004667. 10.1002/14651858.CD004667.pub5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Demography factsheet: Lambeth:- ‘a diverse and changing population’, 2017. Available: https://www.lambeth.gov.uk/sites/default/files/ssh-demography-factsheet-2017.pdf

- 16.NICE . Clinical guideline 62: antenatal care for uncomplicated pregnancies. Available: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg62

- 17.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence . NICE guideline 133: hypertension in pregnancy: diagnosis and management. Available: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng133/chapter/Recommendations#management-of-pre-eclampsia [PubMed]

- 18.Royal College of Obstericians and Gynaecologists . Green top guideline 52: postpartum Haemorhage, prevention and management, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 19.NPEU . IMD tool | NPEU tools. Available: http://tools.npeu.ox.ac.uk/imd/

- 20.English indices of deprivation 2019 . Available: http://imd-by-postcode.opendatacommunities.org/imd/2019

- 21.Cattaneo MD. Efficient semiparametric estimation of multi-valued treatment effects under ignorability. J Econom 2010;155:138–54. 10.1016/j.jeconom.2009.09.023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chantler C, Baum A, Cornwell J. Better births improving outcomes of maternity services in England. A five year view for maternity care. Natl Matern Rev 2015. www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/national-maternity-review-report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 23.Medley N, Vogel JP, Care A, et al. Interventions during pregnancy to prevent preterm birth: an overview of Cochrane systematic reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018;11:CD012505. 10.1002/14651858.CD012505.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organisation . Non-clinical interventions to reduce unnecessary caesarean sections, 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ockenden D. Ockenden report: emerging findings and Reccommendations form the independent review of maternity services at the Shrewsbury and Telford Hospital NHS Trust, 2020. Available: https://www.donnaockenden.com/downloads/news/2020/12/ockenden-report.pdf

- 26.Tracy SK, Hartz DL, Tracy MB, et al. Caseload midwifery care versus standard maternity care for women of any risk: M@NGO, a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2013;382:1723–32. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61406-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.The NHS long term plan, 2019. Available: https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/nhs-long-term-plan-june-2019.pdf

- 28.Fernandez Turienzo C, Bick D, Briley AL, et al. Midwifery continuity of care versus standard maternity care for women at increased risk of preterm birth: a hybrid implementation-effectiveness, randomised controlled pilot trial in the UK. PLoS Med 2020;17:e1003350. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kildea S, Gao Y, Hickey S, et al. Reducing preterm birth amongst Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander babies: a prospective cohort study, Brisbane, Australia. EClinicalMedicine 2019;12:43–51. 10.1016/j.eclinm.2019.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rayment-Jones H, Murrells T, Sandall J. An investigation of the relationship between the caseload model of midwifery for socially disadvantaged women and childbirth outcomes using routine data – A retrospective, observational study. Midwifery 2015;31:409–17. 10.1016/j.midw.2015.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Homer CS, Leap N, Edwards N, et al. Midwifery continuity of carer in an area of high socio-economic disadvantage in London: a retrospective analysis of Albany midwifery practice outcomes using routine data (1997-2009). Midwifery 2017;48:1–10. 10.1016/j.midw.2017.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kennedy HP. A model of exemplary midwifery practice: results of a Delphi study. J Midwifery Womens Health 2000;45:4–19. 10.1016/S1526-9523(99)00018-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davis JAP. Midwives and normalcy in childbirth: a phenomenologic concept development study. J Midwifery Womens Health 2010;55:206–15. 10.1016/j.jmwh.2009.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Phillippi JC, Avery MD. The 2012 American College of nurse-midwives core competencies for basic midwifery practice: history and revision. J Midwifery Womens Health 2014;59:82–90. 10.1111/jmwh.12148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rayment-Jones H, Silverio SA, Harris J, et al. Project 20: midwives' insight into continuity of care models for women with social risk factors: what works, for whom, in what circumstances, and how. Midwifery 2020;84:102654. 10.1016/j.midw.2020.102654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.ten Hoope-Bender P, de Bernis L, Campbell J, et al. Improvement of maternal and newborn health through midwifery. Lancet 2014;384:1226–35. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60930-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McRae DN, Muhajarine N, Stoll K, et al. Is model of care associated with infant birth outcomes among vulnerable women? A scoping review of midwifery-led versus physician-led care. SSM Popul Health 2016;2:182–93. 10.1016/j.ssmph.2016.01.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Robinson JN, Regan JA, Norwitz ER. The epidemiology of preterm labor. Semin Perinatol 2001;25:204–14. 10.1053/sper.2001.27548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Georgiou HM, Di Quinzio MKW, Permezel M, et al. Predicting preterm labour: current status and future prospects. Dis Markers 2015;2015:1–9. 10.1155/2015/435014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Coussons-Read ME. Effects of prenatal stress on pregnancy and human development: mechanisms and pathways. Obstet Med 2013;6:52–7. 10.1177/1753495x12473751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shapiro GD, Fraser WD, Frasch MG, et al. Psychosocial stress in pregnancy and preterm birth: associations and mechanisms. J Perinat Med 2013;41:631–45. 10.1515/jpm-2012-0295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kinsella MT, Monk C. Impact of maternal stress, depression and anxiety on fetal neurobehavioral development. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2009;52:425–40. 10.1097/GRF.0b013e3181b52df1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Trumello C, Candelori C, Cofini M, et al. Mothers’ depression, anxiety, and mental representations after preterm birth: a study during the infant’s hospitalization in a neonatal intensive care unit. Front. Public Health 2018;6. 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ionio C, Colombo C, Brazzoduro V, et al. Mothers and fathers in NICU: the impact of preterm birth on parental distress. Eur J Psychol 2016;12:604–21. 10.5964/ejop.v12i4.1093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pace CC, Spittle AJ, Molesworth CM-L, et al. Evolution of depression and anxiety symptoms in parents of very preterm infants during the newborn period. JAMA Pediatr 2016;170:863. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.0810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jacob J, Lehne M, Mischker A, et al. Cost effects of preterm birth: a comparison of health care costs associated with early preterm, late preterm, and full-term birth in the first 3 years after birth. Eur J Health Econ 2017;18:1041–6. 10.1007/s10198-016-0850-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lindström K, Winbladh B, Haglund B, et al. Preterm infants as young adults: a Swedish national cohort study. Pediatrics 2007;120:70–7. 10.1542/peds.2006-3260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Betran AP, Torloni MR, Zhang J, et al. What is the optimal rate of caesarean section at population level? A systematic review of ecologic studies. Reprod Health 2015;12:57. 10.1186/s12978-015-0043-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sandall J, Tribe RM, Avery L, et al. Short-term and long-term effects of caesarean section on the health of women and children. Lancet 2018;392:1349–57. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31930-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Modder J. CEMACH: perinatal mortality, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Royal College of Obstericians and Gynaecologists . Green top guideline no 45. Birth After Previous Caesarean Section 2015. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request. The complete deidentified patient data set and analytical/Statistical code will be available on request form the corresponding author ruth.hadebe@nhs.net from date of publication.