Abstract

Self-stigma is associated with poor clinical and functional outcomes in Serious Mental Illness (SMI). There has been no review of self-stigma frequency and correlates in different cultural and geographic areas and SMI. The objectives of the present study were: (1) to review the frequency, correlates, and consequences of self-stigma in individuals with SMI; (2) to compare self-stigma in different geographical areas and to review its potential association with cultural factors; (3) to evaluate the strengths and limitations of the current body of evidence to guide future research. A systematic electronic database search (PubMed, Web of Science, PsycINFO, Scopus, and Ovid SP Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature [CINAHL]) following PRISMA guidelines, was conducted on the frequency, correlates, and consequences of self-stigma in SMI. Out of 272 articles, 80 (29.4%) reported on the frequency of self-stigma (n = 25 458), 241 (88.6%) on cross-sectional correlates of self-stigma and 41 (15.0%) on the longitudinal correlates and consequences of self-stigma. On average, 31.3% of SMI patients reported high self-stigma. The highest frequency was in South-East Asia (39.7%) and the Middle East (39%). Sociodemographic and illness-related predictors yielded mixed results. Perceived and experienced stigma—including from mental health providers—predicted self-stigma, which supports the need to develop anti-stigma campaigns and recovery-oriented practices. Increased transition to psychosis and poor clinical and functional outcomes are both associated with self-stigma. Psychiatric rehabilitation and recovery-oriented early interventions could reduce self-stigma and should be better integrated into public policy.

Keywords: self-stigma, serious mental illness, prevalence, correlates, psychiatric rehabilitation

Introduction

For a long time, research on stigma in psychiatric disorders focused on public stigma, or the endorsement of negative beliefs and discriminating attitudes towards individuals by the general population. Over the last two decades, attention has shifted towards the effects of stigma on individuals with Serious Mental Illness (SMI). According to Link and Phelan,1 stigma involves “elements of labeling, stereotyping, separation, status loss, and discrimination” that “co-occur in a power situation that allows the components of stigma to unfold.” The effects of stigma on individuals include perceived, experienced, anticipated, and self-stigma. Perceived stigma is defined as one’s beliefs about the attitudes of the general public towards people with SMI.2 Experienced stigma refers to people with SMI’s experience of discrimination.3 Anticipated stigma—or the expectation that a person will be discriminated against because of their SMI—can occur even if the person has no previous experience of discrimination and contributes to social withdrawal and self-stigma.3 Self-stigma—or internalized stigma—describes the transformation process wherein a person’s previous social identity (defined by social roles such as son, brother, sister, friend, employee, or potential partner) is progressively replaced by a devalued and stigmatized view of oneself, known as “illness identity.” 4 Self-stigma occurs when a person moves beyond mere awareness of public stigma and actually agrees with it and applies it to themself.2 Stigma resistance is defined as a person’s ability to deflect or challenge stigmatizing beliefs.5,6

There is a growing body of evidence—including meta-analyses—on the effects of self-stigma on people with SMI.7–12 In a meta-analysis of 127 articles, Livingston and Boyd7 reported that most studies were conducted in Europe or North America (77.5%), and that schizophrenia was the most common diagnosis (54.3%). Self-stigma is frequent in Europe (41.7% of 1229 participants with schizophrenia and 21.7% of 1182 participants with mood disorders9,10) and North America (36.1% of 144 people with SMI13). Less is known about self-stigma in other geographic areas. The level of self-stigma might vary according to cultural factors (eg, causal attributions of mental illness14) and sociopolitical ideology.15 According to Yang,14 stigma affects “what matters most” in a local social world, by threatening one’s capacity to meet social expectations (eg, the ability to engage in key life activities such as work or marriage14,16) and the whole family’s moral standing and socioeconomic status. Self-stigma might be more common in non-Western countries than in Western countries but this remains unproven.

Compared with those with nonpsychotic disorders, people at risk of psychosis face higher levels of public stigma that can lead to self-stigma.17,18 People with BPD are prone to self-criticism and feelings of shame that can make them more vulnerable to self-stigma.19 They face high levels of stigma, not only from the general public but also from mental health professionals.20 Gerlinger8 reported in a systematic review on stigma in schizophrenia the lack of studies comparing stigma at different stages of illness. It is still unclear whether self-stigma is greater in cases of prolonged psychosis compared with early psychosis, at-risk stages, or other SMI diagnoses.

To date, there have been no literature reviews comparing self-stigma frequency and correlates in different geographical and cultural areas (Europe, North America, South America, Middle East, South Asia, South-East Asia, and Oceania). Similarly, to our knowledge, no literature review has been conducted comparing internalized stigma in at-risk stages, schizophrenia, BD, MDD, BPD, and anxiety disorders. Self-stigma was negatively associated with self-esteem, self-efficacy, quality of life (QoL), and clinical and functional outcomes.7 However, it is difficult to disentangle the specific effects of self-stigma, as measures of perceived or experienced stigma are often used to assess the correlates of self-stigma (43.9% of the 127 studies7). Most studies were cross-sectional (86.7% of 127 studies7). The longitudinal effects of self-stigma remain largely unknown. Several interventions (combinations of psychoeducation and cognitive restructuring in most cases, making empowered decisions about disclosure in others) have been designed to reduce self-stigma and its impact on patients’ outcomes.21 Psychiatric rehabilitation brings together a wide range of recovery-oriented interventions.22 Psychiatric rehabilitation could indirectly reduce self-stigma (eg, through improved psychiatric symptoms, self-esteem, cognitive, social, and vocational functioning) although this remains to be investigated. However, the use of psychiatric rehabilitation services also carries the risk of increased labeling and self-stigma.23,24

In summary, three reviews have been conducted on self-stigma since 2010, in schizophrenia8 and BD.11,12 One meta-analysis investigated the correlates of stigma resistance in SMI.6 To our knowledge, there has been no review of self-stigma frequency and correlates in different cultural and geographic areas and for different SMI conditions; nor any specific reviews of self-stigma, excluding explicitly perceived or experienced stigma. The effects of nonspecific recovery-oriented practices on self-stigma remain unknown. Based on the literature, we would expect to find a higher frequency of self-stigma in Eastern countries compared with Western countries. We made the hypotheses that cultural factors would influence self-stigma and that self-stigma would be associated with poor recovery-related outcomes. The present review has three objectives: (1) to review the frequency, correlates, and consequences of self-stigma in individuals with SMI; (2) to compare self-stigma in different geographical areas and to review its potential association with cultural factors; (3) to evaluate the strengths and limitations of the current body of evidence to guide future research.

Methods

A stepwise systematic literature review (PRISMA guidelines)25 was conducted by searching PubMed, Medline, Web of Science, PsycINFO, the Scopus citation index, and Ovid SP Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) for published, peer-reviewed articles using the following keywords: “schizophrenia” / “bipolar disorder” / “borderline personality disorder” / “major depression” / “depression” / “anxiety disorder” / “serious mental illness” AND “stigma” / “self-stigma” / “internalized stigma”/ “internalised stigma.” No time restriction was set. Only published articles in English or French were included in the review. The reference list of three meta-analyses6,7,26 and three literature reviews8,11,12 on stigma and schizophrenia or BD were screened for additional relevant articles. To be included in this review articles had to meet all of the following criteria: (1) report explicitly on self-stigma (ie, articles on public stigma or using measures of perceived or experienced stigma were excluded); (2) concern a diagnosis of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, borderline personality disorder, major depression or anxiety disorders; (3) provide quantitative data on the prevalence, correlates, or consequences of internalized stigma or stigma resistance. The first author applied the eligibility criteria and screened the records to select the included studies. The last author reviewed each decision. Disputed items were solved through discussion and by reading the article in detail to reach a final decision. For each study, we extracted the following information: general information (author, year of publication, country, design, population considered, setting, total number of participants, mean age, or age range), outcome measure (scale/items used to measure self-stigma, reliability), the main findings, and variables relating to quality assessment (see supplementary table 2 for the detailed characteristics of the included studies). Quality assessment was performed using the Systematic Appraisal of Quality in Observational Research (SAQOR) tool. This tool comprises six domains (sample, control/comparison group, exposure/outcome measurements, follow-up, confounders, and reporting of data27) and has been adapted for cross-cultural psychiatric epidemiology studies.28 An overall quality score (high, moderate, or low) was determined based on adequacy in the six domains. Means and percentages were weighted for the number of cases per study to obtain prevalence data. Derived weighted means by geographical area and pooled standard deviations were calculated. One-way ANOVA was conducted from these summary data and post hoc pairwise test comparisons were computed using the Tukey–Kramer method. Weighted scores were calculated using proportions of rating scale scores. The frequency of self-stigma is often measured using the Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness Scale.29 A score above the midpoint indicates a moderate to high level of self-stigma.9,29 This choice was made for practical reasons (ie, facilitating comparisons between the studies) as there is no valid cutoff for measuring self-stigma. Stigma resistance is often measured using the ISMI stigma resistance subscale, which shows variable internal consistency (0.56 in Firmin et al meta-analysis6). Only the studies reporting internal consistency of above 0.50 were considered when extracting the correlates of stigma resistance. The study protocol was registered on the PROSPERO database on July 4, 2019 (ID 141282).

Results

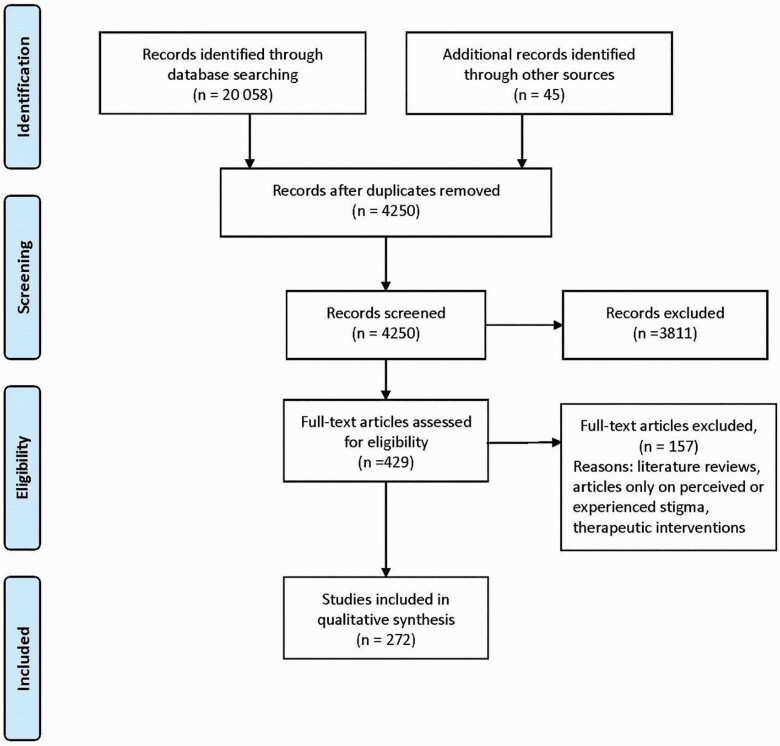

Our search on July 5, 2019 found 3215 articles on PubMed and 11 472 on Web of Science. It was completed by searching PsycINFO, the Scopus citation index, and Ovid SP CINAHL on March 25, 2020 then updated on April 16, 2020. The search was completed on August 22, 2020 using the additional terms “psychosis,” “depression,” “internalized stigma,” and “internalised stigma.” This resulted in 5371 supplementary articles. After manually removing all duplicates, there were 4250 remaining references. Based on their titles and abstracts, 3811 articles were excluded for lack of relevance. Most of these articles focused on public stigma, perceived or experienced stigma, or self-stigma in other discriminated populations. Our search strategy yielded 429 full-text articles. After conducting a full-text analysis of all these articles and excluding those which did not meet the inclusion criteria, we ended up with 272 relevant articles (figure 1). See supplementary table 5 for the list of the excluded studies.

Fig. 1.

Review process (Prisma flow diagram)

The 272 articles included were characterized by the heterogeneity of the samples, methods, scales, and reported outcomes. Most were published after 2010 (244 studies; 89.7%) and used cross-sectional designs (231 studies; 84.9%) with only 41 studies (15.1%) reporting longitudinal outcomes. A total of 89 (95 studies (34.9%) were conducted in Europe, 76 (27.9%) in North America, 44 in South-East Asia (16.2%), 24 (8.8%) in the Middle East, 13 (4.8%) in Africa, 10 in South Asia (3.7%), 4 in South America (1.5%), 4 in Oceania (1.5%), and 2 studies (0.7%) compared internalized stigma in different geographical areas (see supplementary table 1 for the geographical distribution of the included studies).30,31 Most studies included outpatients (211 studies, 77.6%). A total of 30 studies (11.3%) were conducted in a psychiatric rehabilitation context, 5 studies (1.8%) in consumer-operated service programs or advocacy groups and 6 studies (2.2%) in prison settings.

A total of 114 studies (41.9%) concerned schizophrenia, 14 (5.1%) BD, 13 (4.8%) MDD, and 13 (4.8%) at-risk stages or first episode psychosis, 2 (0.7%) anxiety disorders and 1 obsessive-compulsive disorder (0.4%). A total of 115 studies (42.3%) looked at SMI. There were large variations in the definition of SMI. Twenty-five studies (9.6%) defined SMI as schizophrenia, BD, or MDD. Fifty-four studies (20%) used a broad definition of SMI and included participants with anxiety disorders (AD, n = 25), obsessive-compulsive disorder (n = 11), and personality disorders (13 studies). Twelve studies (4.6%) investigated self-stigma in schizophrenia and BD (n = 6), schizophrenia and MDD (n = 1), mood disorders (n = 2), schizophrenia and AD (n = 1), AD and MDD (n = 1), and BPD and social phobia (n = 1). Twenty-four studies (8.1%) did not specify the different forms of SMI. Most studies included young (18–34 years old; 50 studies [18.4%]) or middle-aged participants (35–50 years old; 185 studies [68%]). See supplementary table 6 for the characteristics of studies that included people less than 18 years old. One hundred and ninety-two studies (70.6%) used the Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness29 scale to measure internalized stigma and 33 studies (12.1%) the Self-Stigma of Mental Illness Scale32 (SSMI). Forty-seven studies (17.3%) measured self-stigma with other scales. Most of the instruments used to measure self-stigma in non-Western countries were adaptations of scales designed in Europe or North America (n = 74; 80%). The quality ratings of the included studies obtained using SAQOR27 ranged from high to moderate (respectively, 57.7% and 42.3%). The results are shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Research Characteristics of the 272 Studies Included in the Review

| Characteristic | All studies (n = 272) % |

|---|---|

| Publication date | |

| Pre 2011 | 28 (10.3%) |

| 2011 or later | 244 (89.7%) |

| Study design | |

| Cross-sectional | 231 (84.9%) |

| Longitudinal | 41 (15.1%) |

| Region of study | |

| North America | 76 (27.9%) |

| Europa | 95 (34.9%) |

| South Asia | 10 (3.7%) |

| South East Asia | 44 (16.2%) |

| Middle East | 24 (8.8%) |

| South America | 4 (1.5%) |

| Africa | 13 (4.8%) |

| Australia | 4 (1.5%) |

| Others | 2 (0.7%) |

| Study sites | |

| Single site | 270 (99.3%) |

| Multiple countries/sites | 2 (0.7%) |

| Diagnosis | |

| Severe mental illness | 115 (42.3%) |

| Bipolar disorder | 14 (5.1%) |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | 1 (0.4%) |

| Major depressive disorder | 13 (4.8%) |

| Anxiety disorder | 2 (0.7%) |

| Schizophrenia | 114 (41.9%) |

| At risk stages/first episode psychosis | 13 (4.8%) |

| Mean age | |

| <18 years old | 3 (1.1%) |

| 18–34 years old | 50 (18.4%) |

| 35–50 years old | 185 (68%) |

| >50 years old | 13 (4.8%) |

| Mixed | 21 (7.7%) |

| % articles including people <18 | |

| Yes | 24 (8.8%) |

| No | 248 (91.2%) |

| Internalized stigma measures | |

| Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness (ISMI) | 192 (70.6%) |

| Self-Stigma of Mental Illness Scale (SSMIS) | 33 (12.1%) |

| Others | 47 (17.3%) |

| Patient status | |

| Inpatient | 28 (10.3%) |

| Outpatient | 211 (77.6%) |

| Mixed | 32 (11.8%) |

| Not reported | 1 (0.3%) |

| Psychiatric rehabilitation | |

| Yes | 47 (17.3%) |

| No | 225 (82.7%) |

| Quality rating | |

| High | 157 (57.7%) |

| Moderate | 115 (42.3%) |

Frequency of Self-stigma

Eighty articles (29.4%) reported data on self-stigma extent in SMI, or on the proportion of individuals with moderate to high self-stigma, or on both outcomes. Thirty-three studies were conducted in Europe, 20 studies in North America, 17 in South-East Asia, 9 in Africa, 12 in Middle East, 6 in South Asia, 1 in South America, 1 in Australia, and 1 in Austria and Japan. Nine studies compared the frequency of self-stigma in different countries,9,10,30,33,34 cities,35 or settings.13,36,37 The samples were mostly composed of individuals with schizophrenia (31 studies; 43.4%) or SMI (33 studies; 40.5%). The results are shown in table 2. Forty-seven articles reported on the proportion of moderate to high self-stigma (ISMI >2.5 or above the midpoint on other scales) in a total of 15 871 participants (7500 SMI, 5518 schizophrenia, 1582 BD, 1188 MDD, 64 BPD, 19 AD). Eighty-five articles documented self-stigma extent (ISMI mean total score and standard deviation) in 25 458 participants (11 028 with SMI, 9661 with schizophrenia, 2083 with BD, 2154 with MDD, 377 with AD, 155 with BPD).

Table 2.

Frequency of Internalized Stigma

| Area | Study | Country | N | Mean IS total score | SD | n | High IS (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Europe | SMI | Evans-Lacko51 | Multi-site | 1835 | 2.2 | 0.5 | - | - | |

| Grambal169 | Czech Republic | 184 | 2.19 | 0.5 | - | - | |||

| Rusch58 | Switzerland | 186 | 1.9 | 0.6 | - | - | |||

| Xu57 | Switzerland | 141 | 1.91 | 0.61 | - | - | |||

| Kamaradova170 | Czech Republic | 332 | 2.10 | 0.5 | - | - | |||

| Bradstreet45 | UK | 272 | 2.2 | 0.49 | - | - | |||

| Krajewski33 | Multi-site | 786 | 2.29 (1.96–2.71) | 0.5 | 786 | 33% (15.2%–57.4%) | |||

| Dubreucq93 | France | 738 | 2.20 | 0.51 | 738 | 31.2% | |||

| Oexle96 | Switzerland | 222 | 2.10 | 0.55 | - | - | |||

| Rusch107 | Switzerland | 116 | 2.15 | 0.54 | - | - | |||

| Szczesniak171 | Poland | 114 | 2.23 | 0.5 | - | - | |||

| Weighted total | 4926 | 2.18 | 0.26 | 1524 | 32% | ||||

| Schizophrenia | Brohan9 | Multi-site | 1129 | 2.40 (2.0–2.97) | 0.56 | 1129 | 41.7% | ||

| Vidovic126 | Croatia | 149 | 2.13 | 0.93 | 149 | 22.8% | |||

| Sibitz172 | Austria | 157 | 2.09 | 0.67 | - | - | |||

| Galderisi173 | Italia | 921 | 2.1 | 0.5 | - | - | |||

| Rossi174 | Italia | 910 | 2.2 | 0.44 | - | - | |||

| Aukst-Margetic81 | Croatia | 117 | 2.13 | 0.44 | - | - | |||

| Hofer30 | Austria | 52 | 2.01 | 0.51 | - | - | |||

| Bouvet175 | France | 62 | 2.23 | 0.46 | - | - | |||

| Vrbova176 | Czech Republic | 197 | 2.18 | 0.46 | - | - | |||

| Surmann177 | Germany | 80 | 2.12 | 0.47 | - | - | |||

| Dubreucq93 | France | 466 | 2.18 | 0.51 | 466 | 29.8% | |||

| Holubova178 | Czech Republic | 103 | 2.20 | 0.47 | - | - | |||

| Szczesniak171 | Poland | 51 | 2.19 | 0.5 | - | - | |||

| Uhlmann179 | Germany | 23 | 2.0 | 0.5 | - | - | |||

| Vrbova176 | Czech Republic | 197 | 2.18 | 0.47 | - | - | |||

| Switaj83 | Poland | 110 | 2.39 | 0.53 | - | - | |||

| Weighted total | 4724 | 2.21 | 0.27 | 1744 | 36.9% | ||||

| Bipolar disorders/MDD | Brohan10 | Multi-site | 577 | 1.94 BD | 1.97 | 0.87 | 1182 | 21.7% | |

| 603 | 2.11 MDD | ||||||||

| Bipolar disorders | Post180 | Austria | 60 | 1.9 BD | 0.57 | - | - | ||

| Dubreucq93 | France | 117 | 2.2 | 0.53 | 117 | 29.9% | |||

| Quenneville181 | Switzerland | 69 | 2.27 | 0.5 | - | - | |||

| Szczesniak171 | Poland | 19 | 2.39 | 0.5 | - | - | |||

| MDD | Lanfredi182 | Multi-site | 516 | 2.2 | 0.5 | - | - | ||

| Dubreucq93 | France | 27 | 2.29 | 0.56 | 27 | 40.7% | |||

| Holubova178 | Czech Republic | 80 | 1.96 | 0.42 | - | - | |||

| Prasko95 | Czech Republic | 72 | 2.36 | 0.49 | - | - | |||

| Szczesniak171 | Poland | 42 | 2.46 | 0.6 | - | - | |||

| Weighted total | BD MDD |

842 | 2.01 | 0.60 | 1326 | 22.7% | |||

| 1340 | 2.16 | 0.47 | |||||||

| Anxiety disorders | Ociskova183 | Czech Republic | 109 | 2.24 | 0.49 | - | - | ||

| Grambal169 | Czech Republic | 37 | 1.98 | 0.54 | |||||

| Dubreucq93 | France | 19 | 2.35 | 0.56 | 19 | 42.1% | |||

| OCD | Moritz184 | Germany | 50 | 1.99 | 0.48 | - | - | ||

| Weighted total | - | 215 | 2.14 | - | 19 | 42.1% | |||

| BPD | Grambal169 | Czech Republic | 35 | 2.45 | 0.50 | - | - | ||

| Dubreucq93 | France | 64 | 2.36 | 0.47 | 64 | 43.8% | |||

| Quenneville181 | Switzerland | 39 | 2.56 | 0.66 | - | - | |||

| Personality disorder | Kamaradova170 | Czech Republic | 17 | 2.37 | 0.58 | - | - | ||

| Weighted total | - | 155 | 2.43 | - | 64 | 43.8% | |||

| North America | SMI | Livingston36 | Canada | 91 | 2.13 | 0.38 | 91 | 10% | |

| Livingston37 | Canada | 71 | 2.10 | 0.35 | 71 | 9% | |||

| Livingston43 | Canada | 94 | 2.22 | 0.49 | 94 | 23.4% | |||

| West13 | USA | 144 | 1.72 | 0.57 | 144 | 36.1% (31%–41%) | |||

| Ritscher-Boyd112 | USA | - | - | - | 82 | 28% | |||

| Ritscher-Boyd185 | USA | 149 | 2.19 | 0.52 | 149 | 24.8% | |||

| Drapalski186 | USA | 100 | 2.3 | 0.4 | 100 | 35% | |||

| Harris38 | USA | 235 | 2.31 | 0.47 | 235 | 37% | |||

| Chronister187 | USA | 101 | 2.2 | 0.45 | 101 | 25% | |||

| Kira188 | USA | 330 | 2.16 | 0.72 | 330 | 40.1% | |||

| Tomar189 | USA | 108 | 2.31 | 0.5 | 108 | 40.7% | |||

| Pearl105 | USA | 319 | 2.11 | 0.53 | - | - | |||

| Jahn190 | USA | 516 | 2.25 | 0.49 | - | - | |||

| Villotti191 | USA | 170 | 1.95 | 0.47 | - | - | |||

| Weighted total | - | 2428 | 2.16 | 1505 | 31.4% | ||||

| Schizophrenia | Firmin192 | USA | - | - | - | 111 | 36.5% (25%–45%) | ||

| O’Connor133 | USA | - | - | - | 353 | 50% | |||

| Link193 | USA | - | - | - | 65 | 26.2% | |||

| Lysaker101 | USA | 70 | 2.36 | 0.54 | |||||

| Weighted total | - | 70 | 2.36 | 0.29 | 529 | 44.2% | |||

| Bipolar disorders | Howland42 | USA | 115 | 2.22 | 0.48 | 115 | 26% | ||

| Bassirnia194 | USA | 112 | 1.94 | 0.47 | - | - | |||

| Weighted total | 227 | 2.08 | 0.22 | ||||||

| South America | Schizophrenia | Caqueo-Uritzar34 | Multi-site | 253 | 2.3 | 0.54 | 253 | 38.6% (28.6%–48.7%) | |

| Weighted total | 253 | 2.3 | 0.29 | ||||||

| Australia | Schizophrenia | Hill195 | Australia | 60 | 2.56 | 0.49 | - | - | |

| Weighted total | 60 | 2.56 | 0.24 | ||||||

| South Asia | SMI | Grover196 | India | 1,403 | 2.29 | 0.47 | 1403 | 29.4% | |

| Maharjan197 | Nepal | - | - | - | 180 | 52% | |||

| Weighted total | - | 1403 | 2.29 | 0.22 | 1583 | 28.6% | |||

| Schizophrenia | Grover196 | India | 707 | 2.37 | 0.51 | 707 | 37.9% | ||

| Singh198 | India | 100 | 2.3 | 0.40 | 100 | 29% | |||

| Pal199 | India | 32 | 2.74 | 0.40 | - | - | |||

| Weighted total | - | 839 | 2.37 | 0.24 | 807 | 36.8% | |||

| Bipolar disorders | Grover196 | India | 344 | 2.23 | 0.38 | 344 | 20.6% | ||

| Pal199 | India | 59 | 2.25 | 0.38 | - | - | |||

| Grover200 | India | 185 | 2.33 | 0.43 | 185 | 28% | |||

| Weighted total | - | 588 | 2.26 | 0.15 | 529 | 23.2% | |||

| MDD | Grover196 | India | 352 | 2.19 | 0.45 | 352 | 21% | ||

| Sahoo201 | India | 107 | 2.39 | 0.57 | 107 | 40.1% | |||

| Weighted total | - | 459 | 2.23 | 0.23 | 459 | 25.5% | |||

| Anxiety disorders | Pal199 | India | 30 | 1.97 | 0.37 | - | - | ||

| South-East Asia | SMI | Picco202 | Singapore | 280 | 2.37 | 0.54 | 280 | 43.6% | |

| Ho97 | China | 136 | 2.3 | 0.6 | 136 | 36.8% | |||

| Young35 | China | 474 | 2.42 (2.34–2.50) | 0.52 | 474 | 43.5% (38.3%–49.5%) | |||

| Kim39 | South Korea | 160 | 2.06 | 0.36 | 160 | 8.1% | |||

| Kao40 | Taiwan | 251 | 2.26 | 0.51 | 251 | 50% | |||

| Weighted total | - | 1301 | 2.32 | 0.26 | 1301 | 39.7% | |||

| Schizophrenia | Lv138 | China | 95 | 2.17 | 0.38 | 95 | 20% | ||

| Hsiao61 | Taiwan | 111 | 2.33 | 0.53 | 111 | 27% | |||

| Lien76 | Taiwan | 170 | 2.36 | 0.52 | 170 | 39.4% | |||

| Kao40 | Taiwan | 151 | 2.42 | 0.44 | 151 | 51% | |||

| Li139 | China | 384 | 2.30 | 0.39 | - | - | |||

| Hofer30 | Japan | 60 | 2.16 | 0.42 | - | - | |||

| Ran127 | China | 232 | 2.46 | 0.28 | - | - | |||

| Mak67 | China | 162 | 2.34 | 0.61 | - | - | |||

| Shin88 | South Korea | 70 | 2.11 | 0.53 | - | - | |||

| Pribadi203 | Indonesia | 300 | 2.5 | 0.94 | 300 | 34% | |||

| Picco202 | Singapore | 74 | 2.41 | 0.52 | |||||

| Kim204 | South Korea | 123 | 2.15 | 0.50 | - | - | |||

| Lu205 | China | 92 | 2.11 | 0.45 | - | - | |||

| Park206 | South Korea | 321 | 2.51 | 0.65 | - | - | |||

| Weighted total | - | 2345 | 2.36 | 0.32 | 827 | 32.4% | |||

| Bipolar disorder | Ran127 | China | 39 | 2.36 | 0.30 | - | - | ||

| Weighted total | 2.36 | 0.09 | |||||||

| MDD | Picco202 | Singapore | 74 | 2.44 | 0.55 | - | - | ||

| Woon207 | Malaysia | 99 | 2.0 | 0.6 | 99 | 23.2% | |||

| Ran127 | China | 182 | 2.43 | 0.28 | - | - | |||

| Weighed total | 355 | 2.31 | 0.20 | 99 | 23.2% | ||||

| Anxiety Disorders OCD |

Picco202 | Singapore | 71 | 2.23 | 0.56 | - | - | ||

| Picco202 | Singapore | 61 | 2.41 | 0.49 | - | - | |||

| Weighted total | - | 132 | 2.31 | ||||||

| Middle East | SMI | Ghanean208 | Iran | - | - | - | 138 | 39% | |

| Tanriverdi209 | Turkey | 217 | 2.59 | 0.33 | - | - | |||

| Hasson-Ohayon210 | Israel | 107 | 2.28 | 0.49 | - | - | |||

| Korkmaz211 | Turkey | 224 | 2.53 | 0.48 | - | - | |||

| Weighted total | 548 | 2.50 | 0.18 | ||||||

| Schizophrenia | Sarisoy41 | Turkey | 109 | 2.17 | 0.51 | 109 | 29.4% | ||

| Çapar212 | Turkey | 250 | 2.76 | 0.37 | - | - | |||

| Olçun213 | Turkey | 76 | 2.51 | 0.55 | - | - | |||

| Yilmaz214 | Turkey | 63 | 2.63 | 0.49 | - | - | |||

| Yildirim94 | Turkey | 200 | 2.74 | 0.46 | - | - | |||

| Tanriverdi209 | Turkey | 46 | 2.54 | 0.25 | |||||

| Weighted total | - | 744 | 2.61 | 0.32 | 109 | 29.4% | |||

| Bipolar disorders | Sarisoy41 | Turkey | 118 | 2.10 | 0.46 | 118 | 18.5% | ||

| Cerit215 | Turkey | 80 | 2.12 | 0.39 | - | - | |||

| Sadighi216 | Iran | 126 | 1.90 | 0.87 | 126 | 27.6% | |||

| Tanriverdi209 | Turkey | 63 | 2.52 | 0.32 | - | - | |||

| Weighted total | - | 387 | 2.10 | 0.35 | 244 | 19.2% | |||

| Africa | SMI | Adewuya217 | Nigeria | - | - | - | 340 | 21.6% | |

| Girma53 | Ethiopia | 422 | 2.32 | 0.30 | 422 | 25.1% | |||

| Ibrahim55 | Nigeria | - | - | - | 370 | 22.5% | |||

| Asrat218 | Ethiopia | - | - | - | 317 | 32.1% | |||

| Weighted total | 422 | 2.32 | 0.09 | 1449 | 25.1% | ||||

| Schizophrenia | Mosanya125 | Nigeria | 256 | 1.94 | 0.68 | 256 | 18.8% | ||

| Fadipe219 | Nigeria | 370 | 2.09 | 0.43 | 370 | 16.5% | |||

| Assefa220 | Ethiopia | - | - | - | 212 | 46.7% | |||

| Bifftu124 | Ethiopia | - | - | - | 411 | 48.6% | |||

| Weighted total | - | 626 | 2.03 | 0.29 | 1249 | 32.6% | |||

Note: MDD, Major Depressive Disorder; OCD, Obsessive Compulsive Disorder; BPD, Borderline Personality Disorder; SMI, Severe Mental Illness. Mean Internalized Stigma refers to ISMI mean total score. High Internalized Stigma refers to the proportion of patients with ISMI > 2.5 or above the midpoint on other scales. Bold faces represents the total sample and the weighted means and proportions.

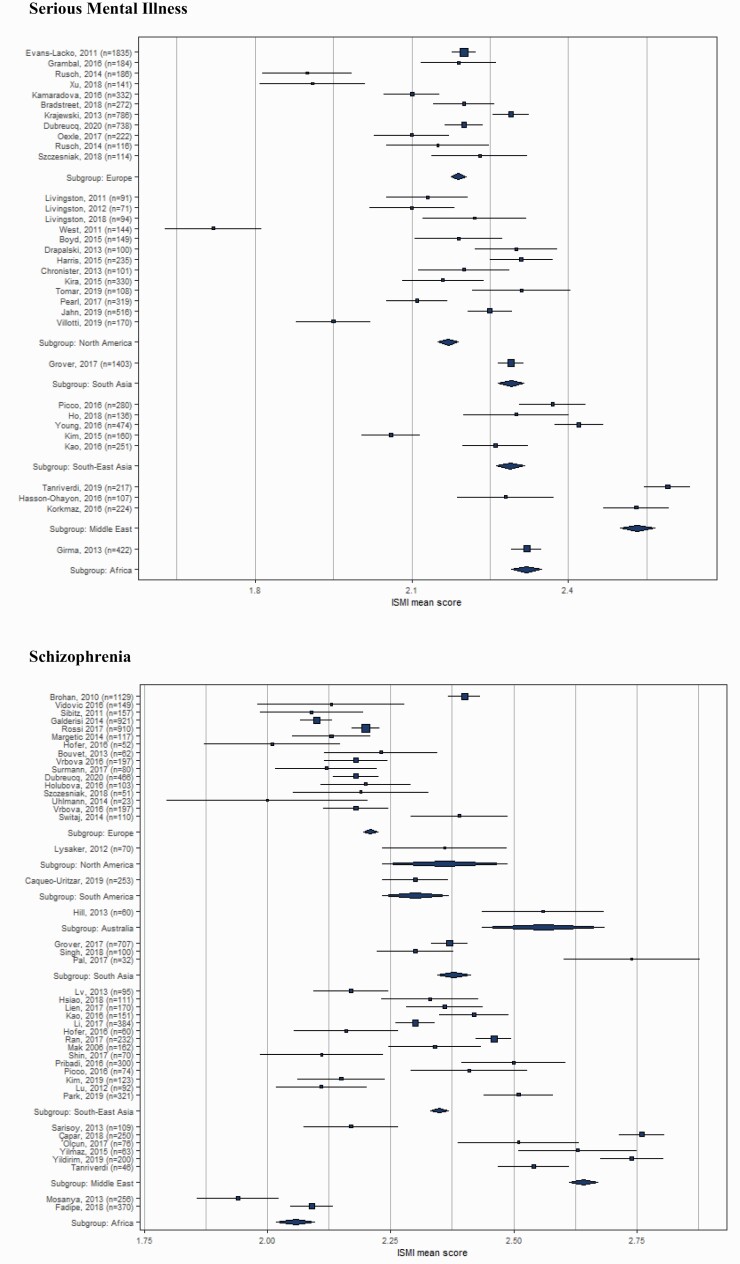

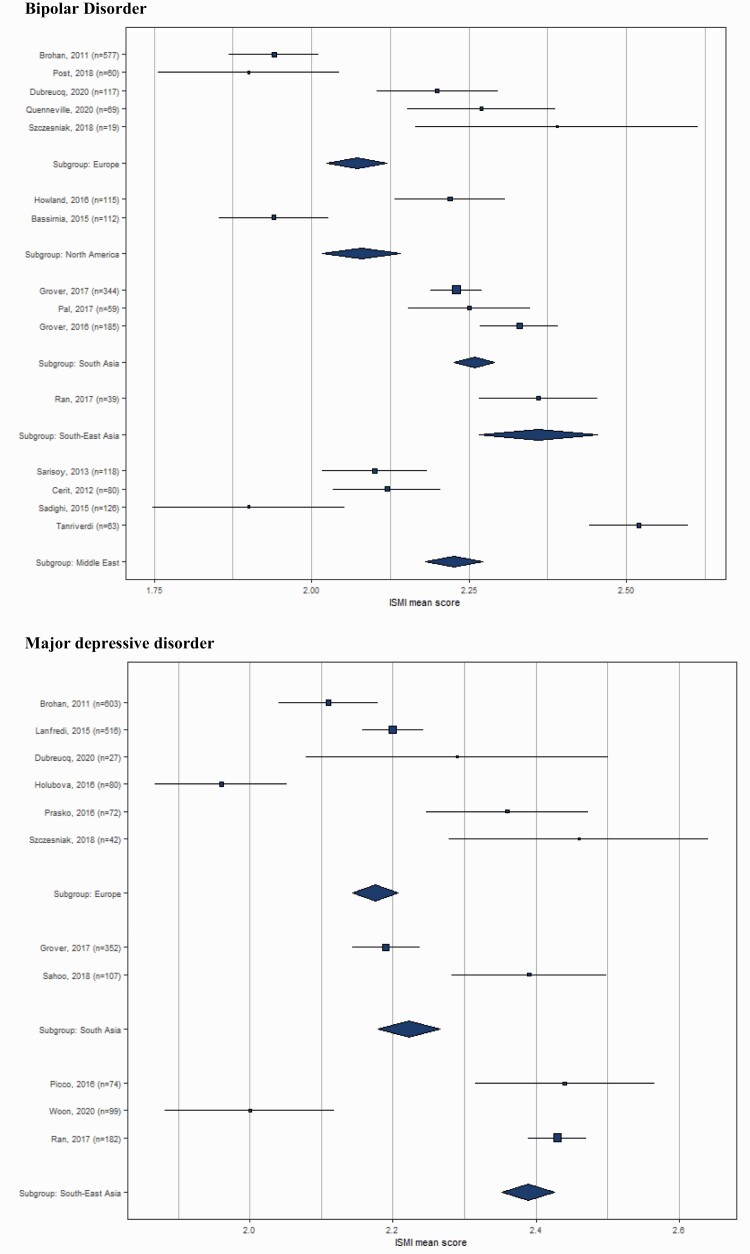

About one-third of people with SMI (31.3%) reported elevated self-stigma. The highest frequency was found in schizophrenia (35.8%). Higher frequency was found in South-East Asia and the Middle East for SMI, and in North America, Europe, and Africa for schizophrenia. Significant between-group differences in mean self-stigma scores were found between Europe and South Asia or South-East Asia for participants with SMI (P < 0.001; weighted mean difference = 0.150 and 0.140), schizophrenia (P < 0.001; 0.159 and 0.143), bipolar disorder (P < 0.001; 0.253 and 0.35), and MDD (P < 0.001; 0.148 and 0.07). Compared with Europe, self-stigma was higher in the Middle East and Africa for SMI (P < 0.001; 0.322 and 0.140) and in the Middle East and South America for schizophrenia (P < 0.001; 0.401 and 0.08). Box plots on the differences by geographical area are provided on table 3. Self-stigma did not differ between South-East Asia and Africa for SMI, South Asia and South-East Asia for schizophrenia, and North America and the Middle East for bipolar disorder. The results are shown in supplementary table S4. There were significant country-related differences in the proportion of people with SMI who reported high self-stigma in Europe (from 15.2% in Sweden9 to 57% in Croatia33), North America (from 9% in Canada37 to 37% in USA38) and in South-East Asia (from 8.1% in South Korea39 to 50% in Taiwan40). Setting-related differences were also found.13,35 Similar variations were found for schizophrenia, BD (18.5% Turkey,41 in remitted BD; 26% USA,42 in non-adherent BD), MDD, obsessive-compulsive disorder and anxiety disorders.

Table 3.

Between-groups Differences by Geographical Area

Means and percentages were weighted for the number of cases per study to obtain prevalence data. Derived weighted means by geographical area and pooled standard deviations were calculated. One-way ANOVA was conducted from these summary data and Post hoc pairwise test comparisons were computed with Tukey–Kramer method. Plots shows the ISMI mean score for each studies and each area with 95% confidence interval.

Cross-sectional Correlates of Self-stigma

Two hundred and forty-one studies (88.6%) reported on cross-sectional internalized stigma correlates. The most common diagnosis was schizophrenia (n = 106; 44%), followed by BD (n = 11; 4.6%) and at-risk states or early psychosis (n = 9; 3.7%). Ninety studies (37.3%) concerned SMI. The results are shown in table 4. See supplementary table 3 for the detailed list of correlates/consequences.

Table 4.

Cross-sectional Correlates and Consequences of Self-stigma

| A | B | C | D | E | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of studies (n = 272) | Non-significant relationship (P > 0.05) | Significant relationship (P < 0.05) | Positive relationship (P < 0.05) | Negative relationship (P < 0.05) | ||||||

| Variables | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| Sociodemographic | ||||||||||

| Gender (1) | 62 | 22.8 | 50 | 80.7 | 12 | 19.3 | 3 | 25.0 | 9 | 75.0 |

| Age | 68 | 25.0 | 49 | 72.1 | 19 | 27.9 | 12 | 63.2 | 7 | 36.8 |

| Education | 60 | 22.1 | 37 | 61.7 | 23 | 38.3 | 10 | 43 | 13 | 57 |

| Employment(2) | 37 | 13.6 | 16 | 43.2 | 21 | 56.8 | 2 | 9.5 | 19 | 90.5 |

| Marital status(3) | 40 | 14.7 | 28 | 70 | 12 | 30 | 3 | 25.0 | 9 | 75.0 |

| Income | 16 | 5.9 | 5 | 31.2 | 11 | 68.8 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 100 |

| Source of income (4) | 11 | 4.0 | 6 | 54.5 | 5 | 45.5 | 3 | 60 | 2 | 40 |

| Immigrant status | 1 | 0.4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100 | 1 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| History of incarceration/homelessness | 2 | 0.7 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 100 | 2 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Experience of victimization | 2 | 0.7 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 100 | 2 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Parenting status (5) | 2 | 0.7 | 1 | 50 | 1 | 50 | 1 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Internalizing personality traits | 6 | 2.2 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 100 | 6 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Self-compassion/mindfulness | 2 | 0.7 | 1 | 50 | 1 | 50 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100 |

| Locality (urban/rural) (6) | 7 | 2.6 | 4 | 57.1 | 3 | 42.9 | 1 | 33.3 | 2 | 66.7 |

| Illness-related | ||||||||||

| Severity of psychiatric symptoms | 65 | 23 | 10 | 15.4 | 55 | 84.6 | 55 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Higher distress from sub-threshold psychotic symptoms/psychiatric symptoms | 2 | 0.7 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 100 | 2 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Age of onset | 26 | 9.6 | 19 | 73.0 | 7 | 27.0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 100 |

| Illness duration | 32 | 11.8 | 22 | 68.7 | 10 | 31.3 | 7 | 70.0 | 3 | 30.0 |

| Stage of illness | 1 | 0.4 | 1 | 100 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - |

| Diagnosis(7) | 38 | 14.0 | 20 | 52.6 | 18 | 47.4 | NA | - | NA | - |

| Insight | 32 | 11.8 | 0 | 0 | 32 | 100 | 32 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Parental insight | 1 | 0.4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100 | 1 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Subjective clinical severity | 3 | 1.1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 100 | 3 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Perceived cognitive dysfunction | 4 | 1.5 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 100 | 4 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Hospitalizations | 38 | 14.0 | 23 | 60.5 | 15 | 39.5 | 14 | 93.3 | 1 | 6.7 |

| Treatment setting (8) | 6 | 2.2 | 3 | 50 | 3 | 50 | 1 | 33.3 | 2 | 66.7 |

| Involuntary hospitalizations (IH) | 3 | 1.1 | 1 | 33.3 | 2 | 66.7 | 2 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Negative emotional reactions to IH | 2 | 0.7 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 100 | 2 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Forensic patient status | 3 | 1.1 | 2 | 66.7 | 1 | 33.3 | 1 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Compulsory community treatment | 1 | 0.4 | 1 | 100 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - |

| History of suicide attempt | 6 | 2.2 | 1 | 16.7 | 5 | 83.3 | 5 | 100 | 0 | 100 |

| Social anxiety | 3 | 1.1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 100 | 3 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Comorbid post-traumatic stress disorder | 2 | 0.7 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 100 | 2 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Comorbid personality disorder | 2 | 0.7 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 100 | 2 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Cormorbid substance use disorder | 3 | 1.1 | 1 | 33.3 | 2 | 66.7 | 2 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Drug extra-pyramidal side-effects | 4 | 1.5 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 100 | 4 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Cognitive functioning | 6 | 2.2 | 1 | 16.7 | 5 | 83.3 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 100 |

| Social cognition | 4 | 1.5 | 1 | 25 | 3 | 75 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 100 |

| Metacognitive abilities | 7 | 2.6 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 100 |

| Dysfunctional attitudes | 1 | 0.4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100 | 1 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Use of negative coping strategies | 8 | 2.9 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 100 | 8 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Environment-related | ||||||||||

| Country level of public stigma | 6 | 2.2 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 100 | 6 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Perceived stigma | 18 | 6.6 | 0 | 0 | 18 | 100 | 18 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Self-labelling | 3 | 1.1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 100 | 3 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Stigma stress | 4 | 1.5 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 100 | 4 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Group value | 3 | 1.1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 100 |

| Perceived legitimacy | 2 | 0.7 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 100 | 2 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Social network | 11 | 4.0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 100 |

| Sense of belonging | 2 | 0.7 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 100 |

| Perceived social support | 21 | 8.4 | 0 | 0 | 21 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 21 | 100 |

| Loneliness | 2 | 0.7 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 100 | 2 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Family sense of coherence | 1 | 0.4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100 |

| Experienced and anticipated stigma | 13 | 4.8 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 100 | 13 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Expressed emotion in families | 1 | 0.4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100 | 1 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Associative stigma in MHP | 1 | 0.4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100 | 1 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Cultural factors | ||||||||||

| Attributing mental illness to supernatural causes | 3 | 1.1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 100 | 3 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| History of traditional treatment | 2 | 0.7 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 100 | 2 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Loss of face in Eastern countries | 2 | 0.7 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 100 | 2 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Psychosocial | ||||||||||

| Self-efficacy | 13 | 4.8 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 100 |

| Empowerment | 11 | 4.0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 100 |

| Self-esteem | 44 | 16.2 | 0 | 0 | 44 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 44 | 100 |

| Hope | 19 | 7.0 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 100 |

| Depression | 41 | 15.1 | 0 | 0 | 41 | 100 | 41 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Suicide risk | 15 | 5.5 | 1 | 6.7 | 14 | 93.3 | 14 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Help-seeking/Therapeutic alliance | 5 | 1.8 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 100 |

| Treatment adherence | 15 | 5.5 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 100 |

| Subjective social status | 1 | 0.4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100 |

| Psychosocial function | 27 | 9.9 | 0 | 0 | 27 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 27 | 100 |

| Activity | 1 | 0.4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100 |

| Self-reported physical health | 2 | 0.7 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 100 |

| Capacity for intimacy/satisfaction in intimate relationships | 4 | 1.5 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 100 |

| Self-reported parenting experiences | 1 | 0.4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100 |

| Quality of life | 41 | 15.1 | 0 | 0 | 41 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 41 | 100 |

| Wellbeing | 9 | 3.3 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 100 |

| Satisfaction with life | 8 | 2.9 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 100 |

| “why try effect” | 2 | 0.7 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 100 | 2 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Coming out (CO)/CO assertiveness | 1 | 0.4 | 1 | 100 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - |

| Benefits from being out | 1 | 0.4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100 |

| Stigma resistance | 11 | 4.0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 100 |

| Resilience | 7 | 2.6 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 100 |

| Personal recovery | 22 | 8.1 | 0 | 0 | 22 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 22 | 100 |

1)Columns D + E; 1 = Men.

2) Columns D + E; 1 = Employed.

3) Columns D + E; 1 = Married.

4) Columns D + E; 1 = Income earner.

5) Columns D + E; 1 = Mothers.

6) Columns D + E; 1 = Urban.

7) Columns D+ E; not applicable (heterogeneity of the samples).

8) Columns D + E; 1= Inpatients.

Table 4 presents the relationships between sociodemographic, illness-related, environment-related, cultural and psychosocial variables with self-stigma (includes 272 studies).

Few sociodemographic characteristics correlated significantly with self-stigma. Immigrant status, history of incarceration or homelessness,36,43 parenting status (mothers > fathers44), shame proneness, and avoidant or self-defeating personality traits (n = 6 studies) were associated with higher self-stigma. The results were contrasted for all other sociodemographic variables (age, gender, education level, employment, marital status, income, and source of income). Other personal characteristics (attachment style, self-compassion) were not associated with self-stigma.45,46 Residual psychiatric symptomatology, positive and negative symptoms for schizophrenia, and depressive symptoms for BD were associated with higher self-stigma in most studies (84.6% significance; n = 65). Social anxiety (n = 3) and distress from sub-threshold psychotic symptoms47 were positively correlated with self-stigma. Self-stigma was equally severe in participants with ultra-high risk and established psychosis.48 Internalized shame about mental illness and fear accuracy in an emotion recognition task were negatively associated in people at risk of psychosis.49 Stigma stress, identified as a predictor of self-stigma in several studies (n = 4), was positively associated with transition to psychosis.50 Comorbid post-traumatic stress disorder (n = 2) and an increased number of drug side effects (n = 4) were positively associated with self-stigma.

Public stigma51 and other dimensions of stigma were associated with self-stigma (perceived stigma, n = 18 studies; perceived stigma from mental health providers,52n = 1; experienced stigma, n = 9; anticipated stigma, n = 3). Cultural factors such as attributing mental illness to supernatural causes,53–55 a history of traditional treatment,53,55 and loss of face in Eastern countries35,56 were associated with self-stigma. Concerns about losing face (or the fear of losing face because of being diagnosed with SMI) mediated the relationship between perceived stigma and self-stigma.56 Stigma stress (n = 4) and negative emotional reactions to involuntary psychiatric admission57,58 were significant correlates of self-stigma, in contrast with compulsory community treatment,37 forensic status,36 and the number of involuntary admissions.57–59 In-group value (ie, how people with SMI see their own group,60 social networks and support (n = 11; n = 21), membership of an advocacy group, and family support protected against self-stigma.61,62 Family expressed emotion and associative stigma in mental health professionals were associated with higher self-stigma.63,64 Self-stigma mediated the effects of family expressed emotion and in-group value on psychosocial function and personal recovery.64,65

Insight into illness (n = 32 studies), parental insight,66 self-perception of clinical severity (n = 3), perceived cognitive dysfunction (n = 4), and attributions of personal responsibility67 were associated with higher self-stigma. Impairments in cognitive and metacognitive function (n = 5; n = 7), dysfunctional attitudes68 and avoidant coping strategies (n = 8) were associated with higher self-stigma. Conversely preserved cognitive abilities,69–71 empowerment, self-efficacy, self-agency, and stigma resistance protected against self-stigma.9,10,62,72 Mixed results were found for other illness-related correlates (age of onset, psychiatric diagnosis, illness duration, history of suicide attempts, inpatient status, past psychiatric admission, and number of hospitalizations).

In general, self-stigma was positively associated with depressive symptoms (n = 41) and suicidal ideation (n = 14) and negatively correlated with hope (n = 19), help seeking (n = 5), and treatment adherence (n = 15). Single studies found negative associations with therapeutic alliance73 and shared decision making.74 Insight into illness,70,75–80 avoidant personality traits,81 and coping strategies,82 loneliness,83 and resilience84 moderated the relationship with depression and self-esteem mediated the effects of self-stigma on hope.85 Self-stigma mediated the effects of perceived cognitive dysfunction and experienced stigma on suicidality86,87 and QoL.88 Self-stigma was negatively associated with QoL (n = 41), self-esteem (n = 44), self-efficacy (n = 13), well-being (n = 9), life satisfaction (n = 8), empowerment (n = 11), resilience (n = 7), stigma resistance (n = 11), and personal recovery (n = 22). Self-stigma positively correlated with the “why try effect” 89 and later stages of self-stigma with a higher impact on hope, self-esteem, psychosocial function, and personal recovery.89,90 Participants in the late stages of self-stigma reported more reasons for not disclosing their psychiatric diagnosis, in contrast with those in the early stages who reported greater benefits from being “out”.91

Self-stigma was negatively associated with global functioning (n = 27). Higher demoralization and decreased resilience mediated the relationship between self-stigma and psychosocial function.75,92 Self-stigma was negatively associated with relational satisfaction.41,93 Self-stigma positively correlated with sense of loneliness,83,94 fear of intimate relationships,41 and self-stigma on parenting abilities for mothers living without their children.44

Self-stigma and Longitudinal Outcomes

Forty-one studies reported longitudinal outcomes associated with internalized stigma. These studies mainly included participants with SMI (n = 15; 36.6%), schizophrenia (n = 16; 39%) or at-risk stages/early psychosis (n = 5; 12.2%). Twelve studies included young participants (<18, n = 1; 18–35, n = 11) and three individuals over 50 years old (10.7%). Fifteen were conducted in psychiatric rehabilitation settings (36.5%). The duration of follow-up ranged from 6 weeks95 to 2 years.96 The results are shown in table 5.

Table 5.

Longitudinal Correlates and Consequences of Self-stigma

| A. | B. | C. | D. | E. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of studies (n = 41) | Non-significant relationship (P > 0.05) | Significant relationship (P < 0.05) | Positive relationship (P < 0.05) | Negative relationship (P < 0.05) | ||||||

| Variables | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| Correlates of increased self-stigma at follow-up | ||||||||||

| Female sex | 5 | 12.2 | 4 | 80 | 1 | 20 | 1 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Hospitalizations | 1 | 2.4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100 | 1 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Duration of untreated psychosis | 1 | 2.4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100 | 1 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Baseline psychiatric symptoms | 5 | 12.2 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 100 | 5 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Shame, self-contempt about IH and stigma stress | 2 | 4.9 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 100 | 2 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Negative coping strategies | 1 | 2.4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100 | 1 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Correlates of reduced self-stigma at follow-up | ||||||||||

| Attending to recovery-oriented daycare/vocational rehabilitation/COSP | 5 | 12.2 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 100 | 5 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Work without experienced discrimination | 1 | 2.4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100 | 1 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Receiving no disability benefits during PR | 1 | 2.4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100 | 1 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Longitudinal consequences of self-stigma | ||||||||||

| Psychiatric symptoms | 5 | 12.2 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 100 | 5 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Social anxiety | 1 | 2.4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100 | 1 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Depression | 6 | 14.6 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 100 | 6 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Suicide risk | 4 | 9.8 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 100 | 4 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Risk of hospitalizations | 1 | 2.4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100 | 1 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Self-esteem | 3 | 7.3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 100 |

| Treatment adherence | 3 | 7.3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 100 |

| Psychosocial function | 9 | 21.9 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 100 |

| Quality of Life | 3 | 7.3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 100 |

| Life satisfaction | 1 | 2.4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100 |

| Personal recovery | 2 | 4.9 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 100 |

Note: COSP, consumer-operated service program; IH, involuntary hospitalization; PR, Psychiatric rehabilitation.

Table 5 presents the longitudinal relationships between sociodemographic, illness-related, environment-related, and psychosocial variables with self-stigma (includes 41 studies).

Fifteen studies reported on the baseline factors influencing the level of self-stigma at follow-up. Residual psychiatric symptoms,97–100 negative emotional reactions to involuntary hospitalization,57,99 and emotional distress98,101 were the most significant baseline factors associated with self-stigma at follow-up. Duration of untreated psychosis97 and baseline coping strategies102 were associated with higher self-stigma in single studies. Mixed results were found for self-stigma stability over time with no specific intervention.86,102–104 Attending psychiatric rehabilitation was associated with significant reductions in self-stigma extent (from a mean total ISMI score of 2.31 on admission to 1.96 at discharge; 38 2.36–2.20; 101 2.11–1.96; 105 2.1–2.04; 106 1.80–1.50 in participants having worked in the past year without being discriminated against107) and in the proportion of participants with high self-stigma (ISMI > 2.5 from 37% to 13.7%; 38 reduction in ISMI levels at follow up > 25% in 38% of the participants with mean self-stigma > 2103). Not receiving disability benefits during psychiatric rehabilitation was associated with a greater reduction in self-stigma.38 Attending consumer-operated service programs was associated with self-stigma reduction.108

Twenty-eight studies reported on the longitudinal consequences of self-stigma. Self-stigma at baseline was associated with increased positive symptoms,109 emotional discomfort,100 social anxiety,110 depression,111,112 suicidal ideation,96,113 and an increased risk of psychiatric hospitalization114 at follow-up. Participants with high self-stigma reported reduced self-esteem,112 decreased life satisfaction,115 lower personal recovery,116 less use of adaptive coping strategies,102 and lower treatment adherence117 at follow-up. Baseline self-stigma was associated with poorer social and vocational functioning109,118 at follow-up, and less benefits from vocational rehabilitation.119 A change in self-stigma during follow-up predicted depression. Increases in self-stigma were associated with more depressive symptoms109 and higher suicidality.99,120 Decreases in self-stigma were associated with less depression.104,105 Increased self-stigma was associated with more negative attitudes towards psychiatric medication,120,121 poorer social function,122 reduced self-esteem,99 and lower personal recovery.116 Reduced self-stigma was associated with decreased subjective clinical severity,105 higher self-esteem,101 and improved global functioning.105 Baseline self-stigma was not associated with QoL at follow-up.37 Decreased self-stigma during follow-up was, however, associated with improvements in QoL105 during psychiatric rehabilitation.

Self-stigma and Stigma Resistance

Thirty-one studies (11.9%) reported data on stigma resistance frequency in SMI. The results are shown in table 6. Stigma resistance was higher in mood disorders (59.7%10) than in schizophrenia (53.1%; n = 5). Stigma resistance in schizophrenia varied within Europe (from 49.2%9 to 63%123 and Africa (from 49.4% in Ethiopia124 to 72.7% in Nigeria125). Stigma resistance was negatively correlated with self-stigma in Austria,30,123 Croatia,126 Nigeria,125 and South Africa.62 In some countries, self-stigma and stigma resistance were both high (USA,42 Turkey, Ethiopia,124 India, Bolivia,34 Peru,34 Chile,34 and China127) and in Canada these were both low.36,37 Metacognitive abilities,128–130 social network,123,131 social power,132 self-compassion,131 psychological flexibility,131 fear of negative evaluation,128 perceived stigma,60,114 negative symptoms,130 and coping strategies129,133 were associated with high stigma resistance.

Table 6.

Prevalence of Stigma Resistance

| Area | Study | Country | n | Mean SR | SD | n | High SR (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Europe | SMI | Grambal169 | Czech Republic | 184 | 2.52 | 0.57 | - | - |

| Dubreucq93 | France | 738 | 2.54 | 0.51 | 693 | 54.1 | ||

| Weighted total | 922 | 2.53 | ||||||

| Schizophrenia | Brohan9 | Multi-site | 1129 | 2.47 (2.29–2.7) | 0.51 | 1129 | 49.2% | |

| Vidovic126 | Croatia | 149 | 2.37 | 0.99 | 149 | 54% | ||

| Sibitz123 | Austria | 157 | 2.73 | 0.76 | 157 | 63.3% | ||

| Hofer30 | Austria | 52 | 2.94 | 0.53 | - | - | ||

| Bouvet175 | France | 62 | 2.46 | 0.55 | - | - | ||

| Vrbova176 | Czech Republic | 197 | 2.56 | 0.48 | - | - | ||

| Surmann177 | Germany | 80 | 2.35 | 0.58 | - | - | ||

| Dubreucq93 | France | 466 | 2.56 | 0.51 | 466 | 55.4% | ||

| Weighted total | - | 2292 | 2.51 | 1435 | 51.2% | |||

| Bipolar Disorders/MDD | Brohan10 | Multi-site | 1182 | 2.81 | 0.98 | 1182 | 59.7% | |

| Dubreucq93 | France | 117 BD | 2.52 | 0.53 | 117 | 52.1% | ||

| 27 MDD | 2.58 | 0.53 | 27 | 59.3% | ||||

| Weighted total | 1326 | 2.77 | 1326 | 59.02% | ||||

| Anxiety disorders | Grambal169 | Czech Republic | 37 | 2.30 | 0.56 | - | - | |

| Dubreucq93 | France | 19 | 2.44 | 0.68 | 19 | 36.8% | ||

| Borderline Personality Disorder | Grambal169 | Czech Republic | 35 | 2.27 | 0.57 | - | - | |

| Dubreucq93 | France | 64 | 2.52 | 0.48 | 64 | 51.6% | ||

| North America | SMI | Livingston37 | Canada | 71 | 2.07 | 0.38 | - | - |

| Livingston43 | Canada | 94 | 2.10 | 0.50 | 94 | 15.9% | ||

| Ritsher-Boyd112 | USA | - | - | - | 82 | 29% | ||

| Weighted total | - | 165 | 2.08 | 176 | 22% | |||

| Bipolar Disorders | Howland42 | USA | 115 | 3.06 | 0.46 | - | - | |

| South America | Schizophrenia | Caqueo-Uritzar34 | Multi-site | 253 | 2.4 | 0.61 | - | – |

| South Asia | Schizophrenia | Singh198 | India | 100 | 2.3 | 0.70 | 100 | 45% |

| Pal199 | India | 32 | 2.84 | 0.50 | - | |||

| Weighted total | - | 132 | 2.43 | 100 | 45% | |||

| Bipolar Disorders | Pal199 | India | 59 | 2.43 | 0.42 | - | - | |

| Grover200 | India | 185 | 2.21 | 0.51 | - | - | ||

| Weighted total | - | 244 | 2.26 | - | - | |||

| South-East Asia | SMI | Ran127 | China | 453 | 2.49 | 0.42 | - | - |

| Lau221 | Singapore | 280 | 2.87 | 0.47 | 280 | 82.9% | ||

| Weighted total | 733 | 2.63 | ||||||

| Schizophrenia | Li139 | China | 384 | 2.28 | 0.45 | - | - | |

| Hofer30 | Japan | 60 | 2.35 | 0.46 | - | - | ||

| Ran127 | China | 232 | 2.50 | 0.36 | - | - | ||

| Weighted total | - | 676 | 2.36 | - | - | |||

| Middle East | SMI | Ghanean208 | Iran | 138 | 2.46 | 0.39 | - | - |

| Schizophrenia | Sarisoy41 | Turkey | 109 | 2.56 | 0.62 | - | - | |

| Çapar212 | Turkey | 250 | 2.41 | 0.35 | - | - | ||

| Olçun213 | Turkey | 76 | 2.60 | 0.60 | - | - | ||

| Karakas222 | Turkey | 60 | 2.62 | 0.63 | - | - | ||

| Yilmaz214 | Turkey | 63 | 2.66 | 0.43 | - | - | ||

| Weighted total score | - | 558 | 2.51 | - | - | |||

| Bipolar Disorders | Sarisoy41 | Turkey | 118 | 2.38 | 0.54 | - | - | |

| Sadighi216 | Iran | 126 | 2.76 | 0.98 | 126 | 57.49% | ||

| Weighted total score | 246 | 2.55 | ||||||

| Africa | SMI | Girma53 | Ethiopia | 422 | 2.41 | 0.40 | - | - |

| Sorsdahl62 | South Africa | 142 | 2.90 | - | - | - | ||

| Weighted total | - | 564 | 2.53 | - | - | |||

| Schizophrenia | Mosanya125 | Nigeria | 256 | 2.79 | 0.53 | 256 | 72.7% | |

| Bifftu124 | Ethiopia | 411 | 2.52 | - | 411 | 49.4% | ||

| Weighted total | 667 | 2.62 | 667 | 58.34% | ||||

Note: MDD, Major Depressive Disorder; SMI, Severe Mental Illness. Mean stigma resistance refers to ISMI stigma resistance subscale mean score. High stigma resistance refers to the proportion of patients with ISMI stigma resistance subscale > 2.5. Bold faces represents the total sample and the weighted means and proportions.

Discussion

Research on self-stigma in SMI has considerably progressed over the past decade (244 articles since 2010 and 28 studies published prior to this).7 Self-stigma was present in all geographical areas with higher frequency in South-East Asia and the Middle East for SMI (>39%). Self-stigma in SMI was higher in the Middle East, South Asia, South-East Asia, and Africa than in Europe or North America. Schizophrenia was associated with high self-stigma in all geographical areas (32.6%–44.2%). Self-stigma in schizophrenia was higher in the Middle East, South-East Asia, South Asia, and South America than in Europe. Self-stigma differed according to the geographical area in mood disorders (higher self-stigma in South Asia and South-East Asia in comparison with Europe, North America, or the Middle East). Variations in patterns of stigma according to the cultural area might explain these differences. The greater public stigma relating to SMI in Eastern countries compared with Western countries could explain the higher levels of self-stigma in South Asia and South-East Asia.134 Other potential factors contributing to higher self-stigma include feelings of shame about not meeting the social expectations of “what matters most” in one’s social group,14,16 moral or supernatural causal attributions of mental illness, and social concerns about the spillover effects disclosing mental illness might have on the social and economic status of family members.53,55,134 The frequency of self-stigma is consistently high across the world. This concurs with several cross-national studies on perceived, experienced, or anticipated stigma.3,135–137 Lower rates of experienced stigma, but similar levels of self-stigma for people with schizophrenia were reported in China and India compared with Western countries.16,138,139 Cultural factors (eg, concerns about disclosure spillover on family members) leading to higher self-stigma and social withdrawal might explain these variations.14,16,138,139 Most of the instruments used for assessing self-stigma in non-Western countries were adapted from scales developed in Europe or North America and did not include culture-specific items. These scales might not reflect all the culture-specific forms of stigma.55,140 Anti-stigma campaigns and self-stigma reduction interventions should take into consideration cultural factors (eg, cost/benefits of strategic disclosure in a given cultural context35,54,141).

Cultural and socio-ideological factors might account for the large country-related variations that were found within geographical areas. Higher public stigma was found in Eastern/Southern Europe compared with Western Europe.142–144 Compared with Western Europe or Canada, higher levels of self-reported sociopolitical conservatism were found in Eastern Europe and the USA.145,146 Gonzales147 and De Luca148 found that self-reported political conservatism and right-wing authoritarianism were associated with increased public stigma. Cultural factors (eg, the endorsement of traditional cultural values, higher in China than in Taiwan or South Korea149) might contribute to the differences observed between Guangzhou and Hong Kong35 or between Taiwan and South Korea.39,40 These variations could be related to sample characteristics (eg, higher reliance on family support in Guangzhou compared with Hong Kong; 35 higher proportion of patients with BD in Korea than in Taiwan39,40).

Sociodemographic and illness-related correlates yielded mixed results in line with previous reviews.7,8 Self-stigma was high in BPD but this is based on a small number of studies with small sample sizes. Self-stigma was equally severe in the at-risk stages as in psychosis.111 Further research is needed to confirm this result. Self-stigma was closely associated with perceived and experienced stigma. These concepts are distinct and should be better differentiated between, as stereotype awareness and self-labeling do not necessarily imply stereotype agreement, self-application, and increased self-stigma.91,150 Self-support groups and recovery-oriented services promoting positive group identification60,106 should be further developed to prevent or reduce self-stigma. Reducing self-stigma implies targeting the explicitly negative views about the self that relate to being diagnosed with SMI. Making an empowered decision about disclosing an SMI diagnosis might be effective for adolescents or people in the early stages of self-stigma.91,151 People in the late stages of self-stigma may need to take part in group interventions combining psychoeducation and cognitive restructuring.21,57 Interventions should be proposed to each individual according to his/her personal needs and level of self-stigma.

The association between self-stigma with treatment setting varies (50% significance). Two studies reported higher self-stigma in outpatients compared with inpatients152,153 and one the opposite.83 Loneliness, low social support, perceived stigma, experienced stigma, and anticipated stigma might contribute to higher self-stigma in outpatients.152,153 Participating in community activities, good social support, and attending psychiatric rehabilitation services or consumer-operated service programs protect against self-stigma.9,62,105,108 Stigma stress, negative emotional reactions to involuntary hospitalization, and the use of avoidant coping strategies after discharge contribute to higher self-stigma.57,58,102 Improved inpatient care (ie, the implementation of recovery-oriented practices and interventions targeting stigma stress, therapeutic alliance and coping strategies) might result in better patient outcomes after discharge, although this remains to be investigated.

The development of recovery-oriented practices in mental health facilities should be encouraged as it could reduce perceived stigma, stigma stress,57–59 and negative emotional reactions to involuntary admissions.57–59 Peer-supported self-management interventions, Joint Crisis Plans, “No Force First” policies, and selective disclosure programs could improve self-stigma through reduced stigma stress and perceived coercion.151,154–156 Recovery-oriented training programs for mental health professionals improve personal recovery in people with SMI.157 They may also improve mental health professionals’ job satisfaction, burnout, and associative stigma of mental illness.15,63 Their effectiveness in reducing self-stigma in patients should be investigated.

Given the potential relationships with stigma stress,50 duration of untreated psychosis,97 distress from sub-threshold psychotic symptoms,47 and transition to psychosis,50 the effects of recovery-oriented early interventions on self-stigma and its consequences should be further investigated. Strategic disclosure programs result in people making empowered decisions about whether to disclose a diagnosis of SMI or not. They result in improved stigma stress and self-stigma in adolescents with SMI151 and should be integrated into recovery-oriented early intervention services.

As expected,7,8 self-stigma was negatively associated with recovery-related outcomes and positively associated with depression and suicidal ideation. Cognitive impairments, dysfunctional attitudes, and avoidant coping strategies were positively associated with self-stigma. Insight into illness was the most significant moderator of internalized stigma. Perceived cognitive dysfunction, perceived and experienced stigma all had indirect effects on clinical and functional outcomes via self-stigma. Baseline self-stigma was associated with poorer recovery-related outcomes and less benefit from vocational rehabilitation at follow-up.8,119 Reduction in self-stigma was associated with improved depression, suicidality, attitudes towards medication, self-esteem, QoL, and social function at follow-up.

Improved treatment (ie, recovery-oriented practices and nonspecific interventions targeting therapeutic alliance, dysfunctional attitudes, self-esteem, or coping strategies) could indirectly reduce self-stigma.158–160 Recovery-oriented psychoeducation improves treatment adherence and reduces the risk of hospitalization.161 Improved therapeutic alliance is associated with better recovery-related outcomes after attending to early interventions services.158 Other interventions such as cognitive behavioral therapy, cognitive remediation, or social skills training might reduce self-stigma through improved symptoms, dysfunctional attitudes, and functioning.22,159,160,162 Given the potential relationship between expressed emotion in the families of people with SMI and self-stigma and recovery-related outcomes,64,65 family psychoeducation could be effective for self-stigma.163 Family psychoeducation should be recovery-oriented and address both public stigma and self-stigma.164–167 The relationship between self-stigma in people with SMI and in their relatives is still unclear and should be further investigated.168

Stigma resistance and self-stigma were negatively associated with each other6 but with different patterns. Self-stigma and stigma resistance are distinct constructs and should be measured using more specific scales.6

Limitations

There are some limitations to this review due to the heterogeneity in the definition of SMI and in the samples, settings, methods, scales, and reported outcomes. Few articles reported longitudinal outcomes with a limited number of studies conducted in psychiatric rehabilitation settings. This review excluded studies where self-stigma was not the main focus, which means that stigma in all its forms (ie, perceived, experienced or anticipated stigma, and self-stigma) could actually have more wide-ranging effects on people with SMI. However, by focusing on self-stigma, this review provides a more accurate understanding of its effects on people with SMI. The heterogeneity of the samples, methods, scales, and reported outcomes in the included articles limited the possibilities for extracting comparable data. The large number of studies included in this review and the range of countries represented is however a considerable strength. The under-reporting of negative or nonsignificant results due to publication bias and the exclusion of unpublished studies from this review might have limited the accuracy of the synthesis. The present systematic review does not include a meta-analysis. This decision was made due to the large number of studies and the heterogeneity of the samples, methods, scales, and reported outcomes. Statistical analyses were used to compare self-stigma frequency in different geographical areas (the second objective of the present study). Future meta-analyses with a more limited focus (eg, on the impact of self-stigma on recovery-related outcomes) could be conducted to explore the present findings in more detail.

Conclusions

In short, self-stigma is a severe problem in all SMI conditions (including the at-risk stages) and all geographical areas and is associated with poor clinical and functional outcomes. Levels of public, perceived, and experienced stigma (including from mental health providers) are significant predictors of self-stigma, pleading for the reinforcement of anti-stigma campaigns and the development of recovery-oriented practices in mental health settings. The respective associations between the duration of untreated psychosis, self-stigma, and transition to psychosis support the development of recovery-oriented early intervention programs. Psychiatric rehabilitation could be an effective means of reducing self-stigma and should therefore be further developed in public policies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mrs Kim Barrett for proofreading the manuscript. They are also grateful to the reviewers of a previous version of the manuscript for their helpful comments.

Author contribution: The two authors had full access to the data in the study and take the responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Dr Julien Dubreucq drafted the article. Dr Julien Dubreucq and Prof Nicolas Franck carried out the literature review. M. Julien Plasse did the statistical analysis. Prof Nicolas Franck critically revised the article. Both authors were involved in the collection and analysis of the data. Both authors contributed to and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of interests: none.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grants from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1. Link BG, Phelan JC. Conceptualizing stigma. Annu Rev Sociol. 2001;27:363–385. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Corrigan PW, Larson JE, Rüsch N. Self-stigma and the “why try” effect: impact on life goals and evidence-based practices. World Psychiatry. 2009;8(2):75–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Thornicroft G, Brohan E, Rose D, Sartorius N, Leese M; INDIGO Study Group . Global pattern of experienced and anticipated discrimination against people with schizophrenia: a cross-sectional survey. Lancet. 2009;373(9661):408–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yanos PT, Roe D, Markus K, Lysaker PH. Pathways between internalized stigma and outcomes related to recovery in schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(12):1437–1442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Thoits PA. Resisting the stigma of mental illness. Soc Psychol Q. 2011;74(1):6–28. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Firmin RL, Luther L, Lysaker PH, Minor KS, Salyers MP. Stigma resistance is positively associated with psychiatric and psychosocial outcomes: a meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2016;175(1–3):118–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Livingston JD, Boyd JE. Correlates and consequences of internalized stigma for people living with mental illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(12):2150–2161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gerlinger G, Hauser M, De Hert M, Lacluyse K, Wampers M, Correll CU. Personal stigma in schizophrenia spectrum disorders: a systematic review of prevalence rates, correlates, impact and interventions. World Psychiatry. 2013;12(2):155–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brohan E, Elgie R, Sartorius N, Thornicroft G; GAMIAN-Europe Study Group . Self-stigma, empowerment and perceived discrimination among people with schizophrenia in 14 European countries: the GAMIAN-Europe study. Schizophr Res. 2010;122(1–3):232–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brohan E, Gauci D, Sartorius N, Thornicroft G; GAMIAN-Europe Study Group . Self-stigma, empowerment and perceived discrimination among people with bipolar disorder or depression in 13 European countries: the GAMIAN-Europe study. J Affect Disord. 2011;129(1–3):56–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ellison N, Mason O, Scior K. Bipolar disorder and stigma: a systematic review of the literature. J Affect Disord. 2013;151(3):805–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hawke LD, Parikh SV, Michalak EE. Stigma and bipolar disorder: a review of the literature. J Affect Disord. 2013;150(2):181–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. West ML, Yanos PT, Smith SM, Roe D, Lysaker PH. Prevalence of internalized stigma among persons with severe mental illness. Stigma Res Action. 2011;1(1):3–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yang LH, Chen FP, Sia KJ, et al. “What matters most:” a cultural mechanism moderating structural vulnerability and moral experience of mental illness stigma. Soc Sci Med. 2014;103:84–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yanos PT, DeLuca JS, Salyers MP, Fischer MW, Song J, Caro J. Cross-sectional and prospective correlates of associative stigma among mental health service providers. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2020;43(2):85–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Koschorke M, Padmavati R, Kumar S, et al. Experiences of stigma and discrimination of people with schizophrenia in India. Soc Sci Med. 2014;123:149–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yang LH, Wonpat-Borja AJ, Opler MG, Corcoran CM. Potential stigma associated with inclusion of the psychosis risk syndrome in the DSM-V: an empirical question. Schizophr Res. 2010;120(1–3):42–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yang LH, Anglin DM, Wonpat-Borja AJ, Opler MG, Greenspoon M, Corcoran CM. Public stigma associated with psychosis risk syndrome in a college population: implications for peer intervention. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(3):284–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rüsch N, Hölzer A, Hermann C, et al. Self-stigma in women with borderline personality disorder and women with social phobia. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2006;194(10):766–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gunderson JG, Herpertz SC, Skodol AE, Torgersen S, Zanarini MC. Borderline personality disorder. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4:18029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yanos PT, Lucksted A, Drapalski AL, Roe D, Lysaker P. Interventions targeting mental health self-stigma: a review and comparison. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2015;38(2):171–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Franck N, Bon L, Dekerle M, et al. Satisfaction and needs in serious mental illness and autism spectrum disorder: the REHABase psychosocial rehabilitation project. Psychiatr Serv. 2019;70(4):316–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Moritz S, Gawęda Ł, Heinz A, Gallinat J. Four reasons why early detection centers for psychosis should be renamed and their treatment targets reconsidered: we should not catastrophize a future we can neither reliably predict nor change. Psychol Med. 2019;49(13):2134–2140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yang LH, Lo G, WonPat-Borja AJ, Singla DR, Link BG, Phillips MR. Effects of labeling and interpersonal contact upon attitudes towards schizophrenia: implications for reducing mental illness stigma in urban China. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012;47(9):1459–1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wood L, Byrne R, Varese F, Morrison AP. Psychosocial interventions for internalised stigma in people with a schizophrenia-spectrum diagnosis: a systematic narrative synthesis and meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2016;176(2–3):291–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ross LE, Grigoriadis S, Mamisashvili L, et al. Quality assessment of observational studies in psychiatry: an example from perinatal psychiatric research. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2011;20(4):224–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kohrt BA, Rasmussen A, Kaiser BN, et al. Cultural concepts of distress and psychiatric disorders: literature review and research recommendations for global mental health epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(2):365–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ritsher JB, Otilingam PG, Grajales M. Internalized stigma of mental illness: psychometric properties of a new measure. Psychiatry Res. 2003;121(1):31–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hofer A, Mizuno Y, Frajo-Apor B, et al. Resilience, internalized stigma, self-esteem, and hopelessness among people with schizophrenia: cultural comparison in Austria and Japan. Schizophr Res. 2016;171(1–3):86–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mileva VR, Vázquez GH, Milev R. Effects, experiences, and impact of stigma on patients with bipolar disorder. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2013;9:31–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Corrigan P, Watson A, Barr L. The self-stigma of mental illness: implications for self-esteem and self-efficacy. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2006;25:875e884. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Krajewski C, Burazeri G, Brand H. Self-stigma, perceived discrimination and empowerment among people with a mental illness in six countries: Pan European stigma study. Psychiatry Res. 2013;210(3):1136–1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Caqueo-Urízar A, Boyer L, Urzúa A, Williams DR. Self-stigma in patients with schizophrenia: a multicentric study from three Latin-America countries. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2019;54(8):905–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Young DK, Ng PY. The prevalence and predictors of self-stigma of individuals with mental health illness in two Chinese cities. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2016;62(2):176–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Livingston JD, Rossiter KR, Verdun-Jones SN. ‘Forensic’ labelling: an empirical assessment of its effects on self-stigma for people with severe mental illness. Psychiatry Res. 2011;188(1):115–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Livingston J. Self-stigma and quality of life among people with mental illness who receive compulsory community treatment services. J Community Psychol. 2012;40:699–714. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Harris JI, Farchmin L, Stull L, Boyd J, Schumacher M, Drapalski AL. Prediction of changes in self-stigma among veterans participating in partial psychiatric hospitalization: the role of disability status and military cohort. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2015;38(2):179–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kim WJ, Song YJ, Ryu HS, et al. Internalized stigma and its psychosocial correlates in Korean patients with serious mental illness. Psychiatry Res. 2015;225(3):433–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kao YC, Lien YJ, Chang HA, Wang SC, Tzeng NS, Loh CH. Evidence for the indirect effects of perceived public stigma on psychosocial outcomes: the mediating role of self-stigma. Psychiatry Res. 2016;240:187–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sarısoy G, Kaçar ÖF, Pazvantoğlu O, et al. Internalized stigma and intimate relations in bipolar and schizophrenic patients: a comparative study. Compr Psychiatry. 2013;54(6):665–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Howland M, Levin J, Blixen C, Tatsuoka C, Sajatovic M. Mixed-methods analysis of internalized stigma correlates in poorly adherent individuals with bipolar disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 2016;70:174–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Livingston J, Patel N, Bryson S, et al. Stigma associated with mental illness among Asian men in Vancouver, Canada. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2018;64(7):679–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lacey M, Paolini S, Hanlon MC, Melville J, Galletly C, Campbell LE. Parents with serious mental illness: differences in internalised and externalised mental illness stigma and gender stigma between mothers and fathers. Psychiatry Res. 2015;225(3):723–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bradstreet S, Dodd A, Jones S. Internalised stigma in mental health: an investigation of the role of attachment style. Psychiatry Res. 2018;270:1001–1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Døssing M, Nilsson KK, Svejstrup SR, Sørensen VV, Straarup KN, Hansen TB. Low self-compassion in patients with bipolar disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 2015;60:53–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Denenny D, Thompson E, Pitts SC, Dixon LB, Schiffman J. Subthreshold psychotic symptom distress, self-stigma, and peer social support among college students with mental health concerns. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2015;38(2):164–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Pyle M, Morrison AP. Internalised stereotypes across ultra-high risk of psychosis and psychosis populations. Psychosis. 2017;9:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Larsen EM, Herrera S, Bilgrami ZR, et al. Self-stigma related feelings of shame and facial fear recognition in individuals at clinical high risk for psychosis: a brief report. Schizophr Res. 2019;208:483–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]