Abstract

Lipocalin-type prostaglandin (PG) D2 synthase (L-PGDS) catalyzes the isomerization of PGH2, a common precursor of the two series of PGs, to produce PGD2. PGD2 stimulates three distinct types of G protein-coupled receptors: (1) D type of prostanoid (DP) receptors involved in the regulation of sleep, pain, food intake, and others; (2) chemoattractant receptor-homologous molecule expressed on T helper type 2 cells (CRTH2) receptors, in myelination of peripheral nervous system, adipocyte differentiation, inhibition of hair follicle neogenesis, and others; and (3) F type of prostanoid (FP) receptors, in dexamethasone-induced cardioprotection. L-PGDS is the same protein as β-trace, a major protein in human cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). L-PGDS exists in the central nervous system and male genital organs of various mammals, and human heart; and is secreted into the CSF, seminal plasma, and plasma, respectively. L-PGDS binds retinoic acids and retinal with high affinities (Kd < 100 nM) and diverse small lipophilic substances, such as thyroids, gangliosides, bilirubin and biliverdin, heme, NAD(P)H, and PGD2, acting as an extracellular carrier of these substances. L-PGDS also binds amyloid β peptides, prevents their fibril formation, and disaggregates amyloid β fibrils, acting as a major amyloid β chaperone in human CSF. Here, I summarize the recent progress of the research on PGD2 and L-PGDS, in terms of its “molecular properties,” “cell culture studies,” “animal experiments,” and “clinical studies,” all of which should help to understand the pathophysiological role of L-PGDS and inspire the future research of this multifunctional lipocalin.

Keywords: sleep, food intake, adipogenesis, innate immunity, inflammation, beta-trace protein, amyloid-beta chaperon, reproduction

Introduction

In 1985, I purified lipocalin-type prostaglandin (PG) D2 synthase (L-PGDS) from rat brain as a prostaglandin H2 (PGH2) D-isomerase (EC:5.3.99.2), that catalyzes the isomerization of a 9,11-endoperoxide group of PGH2, a common intermediate of the two series of prostanoids, to produce prostaglandin D2 (PGD2) with 9-hydroxy and 11-keto groups (Urade et al., 1985). The cDNA cloning of L-PGDS demonstrated that the amino acid sequence of L-PGDS has the homology with members of the lipocalin family which is composed of a variety of secretory proteins that bind and transport lipophilic small substances, such as β-lactoglobulin, α2-urinary globulin, placental protein 14, and α1-microglobulin (Urade and Hayaishi, 2000a). L-PGDS possesses a typical lipocalin fold of β-barrel with a central hydrophobic cavity, the retinoid-binding activity similar to other lipocalins, and the chromosomal gene structure with the same numbers and sizes of exons and phase of splicing of introns as those of other lipocalins (Urade and Hayaishi, 2000a).

Those studies open a new field of the lipocalin research, because that L-PGDS is the first lipocalin characterized as an enzyme among members of the lipocalin family and that L-PGDS produces an important bioactive lipid mediator PGD2. PGD2 plays important roles in the regulation of a variety of patho-physiological functions, such as sleep, pain, food intake in the central nervous system (CNS), inflammation and innate immunity, diabetes, cardiovascular functions and also in the reproduction systems.

I published several reviews of L-PGDS and PGD2 (Urade and Hayaishi, 2000a, b, 2011; Urade and Eguchi, 2002; Smith et al., 2011). In this article, I classify the reports concerning with L-PGDS mainly after publication of those reviews and summarize the new finding of each section as follows:

-

1)

Biological function of prostaglandin D2 produced by lipocalin-type prostaglandin D2 synthase,

-

2)

Ligand binding properties of lipocalin-type prostaglandin D2 synthase as an extracellular transporter,

-

3)

Structural characterization of lipocalin-type prostaglandin D2 synthase by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and X-ray crystallography,

-

4)

Cell culture studies of lipocalin-type prostaglandin D2 synthase,

-

5)

Mammalian experiments for the study of lipocalin-type prostaglandin D2 synthase,

-

6)

Pharmacokinetic analyses and functionalization with recombinant lipocalin-type prostaglandin D2 synthase,

-

7)

Studies of nonmammalian orthologs of lipocalin-type prostaglandin D2 synthase,

-

8)

Clinical studies of pathophysiological function of lipocalin-type prostaglandin D2 synthase,

-

9)

Future subjects.

Biological Function of Prostaglandin D2 Produced by Lipocalin-Type Prostaglandin D2 Synthase

Supplementary Table 1 summarizes the research history of L-PGDS and PGD2. PGD2 was originally discovered as a by-product of biosynthesis of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and prostaglandin F2α (PGF2α). Both PGE2 and PGF2α exhibit potent activities on the smooth muscle contraction, whereas PGD2 does not show the strong smooth muscle contractile activity. Therefore, the physiological function of PGD2 was not extensively investigated until the discovery of potent action of PGD2 on the regulation of inflammation and sleep.

In the early 1980s, PGD2 was found to be a major prostaglandin produced in the brain of various mammals (Narumiya et al., 1982) including humans (Ogorochi et al., 1984) and to induce sleep after administration into the brain of freely moving rats (Ueno et al., 1982) and monkeys (Onoe et al., 1988). From those findings, the biochemical and neurological studies of PGD2 in the CNS were accelerated. In 1979, other type of PGD2 synthase, hematopoietic PGD2 synthase (H-PGDS), was purified from rat spleen (Christ-Hazelhof and Nugteren, 1979). Comparisons of L-PGDS with H-PGDS revealed that these two enzymes are quite different proteins from each other (Urade et al., 1987), i.e., L-PGDS is a member of the lipocalin family (Nagata et al., 1991) and H-PGDS is the first identified invertebrate ortholog of sigma class of glutathione S-transferase (Kanaoka et al., 1997; Kanaoka and Urade, 2003). L-PGDS and H-PGDS have been evolved from different origins to acquire the same catalytic ability, being new examples of functional convergence (Urade and Eguchi, 2002; Smith et al., 2011).

Supplementary Table 2 summarizes the catalytic, molecular and genetic properties of human L-PGDS and H-PGDS. We isolated cDNAs and chromosomal genes of L-PGDS (L-Pgds or Ptgds; Urade et al., 1989; Igarashi et al., 1992) and H-PGDS (Hpgds; Kanaoka et al., 1997, 2000), and then determined X-ray crystallographic structures of the recombinant proteins of L-PGDS and H-PGDS expressed in E. coli (Kanaoka et al., 1997; Kumasaka et al., 2009), respectively. The inhibitors selective to L-PGDS, SeCl4 and AT56 (Irikura et al., 2009), and to H-PGDS, HQL79 (Aritake et al., 2006), TFC007 (Nabea et al., 2011) and TAS204 (Urade, 2016) were found. We also generated KO mice of L-Pgds and Hpgds genes (Eguchi et al., 1999; Park et al., 2007), respectively, human enzyme-overexpressing transgenic (TG) mice (Fujitani et al., 2002, 2010), respectively, and flox mice used for conditional KO mice (Kaneko et al., 2012; Nakamura et al., 2017), respectively. In double KO mice of L-Pgds and Hpgds genes, the production of PGD2 in the brain and other tissues is almost undetectable, indicating that these two enzymes are major components responsible for the biosynthesis of PGD2 in our body (Kaushik et al., 2014).

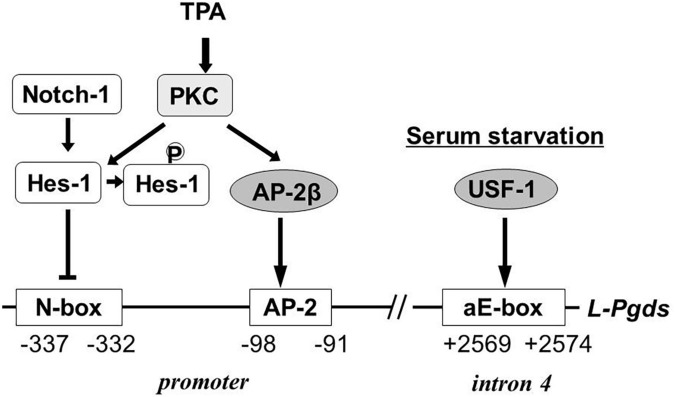

Figure 1 shows the biosynthesis of PGD2. PGD2 is produced from arachidonic acid (C20:4), a major polyunsaturated fatty acid in our body, integrated in C2 position of phospholipids. Once cells are stimulated by various hormones, cytokines, and other signals, arachidonic acid is released from phospholipids by the action of cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2) or group III phospholipase A2 (PLA2G3). A part of the released arachidonic acid is oxygenated by cyclooxygenase (Cox)-1 or 2 (PGH2 synthase-1 or -2, these genes are ptgs or ptgs2, respectively) to produce PGH2, a common intermediate of the two series of PGs, PGD2, PGE2, PGF2α, PGI2 (prostacyclin) and thromboxane (TX) A2, in which 2 indicates the number of unsaturated C=C bond. PGH2 is converted by L-PGDS or H-PGDS to PGD2, in the presence of exogenous sulfhydryl compounds, most likely a reduced form of glutathione within the cells. Both Cox-1 and -2 are microsomal membrane-binding enzymes and produce PGH2 within the cells. PGH2 is chemically unstable in aqueous solution with a t1/2 of several min to degrade a mixture of PGE2 and PGD2 at a ratio of 2:1. Therefore, it is unlikely that L-PGDS in the extracellular space interacts with PGH2 to produce PGD2 selectively. As L-PGDS binds a variety of hydrophobic substances, such as retinoids and thyroids, L-PGDS in the extracellular space may act as an extracellular transporter for these hydrophobic ligands.

FIGURE 1.

Biosynthesis pathway of PGD2.

Prostaglandin D2 stimulates three distinct types of G-protein coupled receptors (Supplementary Table 3). One is D type of prostanoid (DP) receptors (also abbreviated as DP1) coupled with Gs-protein to increase intracellular cAMP levels (Hirata et al., 1994). DP receptors are involved in the regulation of sleep (Qu et al., 2006), pain (Eguchi et al., 1999), food intake (Ohinata et al., 2008) and others. Two is chemoattractant receptor-homologous molecule expressed on T helper type 2 cells (CRTH2) receptors (also abbreviated as DP2, previously known as GPR44 of an orphan receptor, or CD294) coupled with Gi-protein to decrease intracellular cAMP levels (Nagata et al., 1999; Hirai et al., 2001). CRTH2 receptors are involved in myelination of peripheral nervous system (Trimarco et al., 2014), adipocyte differentiation (Wakai et al., 2017), inhibition of hair follicle neogenesis (Nelson et al., 2013) and others. Three is F type of prostanoid (FP) receptors (Abramovitz et al., 1994) coupled with Gq-protein to increase intracellular Ca2+ concentrations. FP receptors are activated by either PGD2 or PGF2α at almost the same binding affinities and involved in protection of the heart against ischemia-reperfusion injury by activating Nrf2 (Katsumata et al., 2014). Human genes, stable agonists and antagonists, and physiological functions mediated by DP, CRTH2, and FP receptors are also shown in Supplementary Table 3. The KO mice of Ptgdr (for DP, Matsuoka et al., 2000), Ptgdr2 (for CRTH2, Satoh et al., 2006) and Ptgfr (FP, Sugimoto et al., 1997) genes and the flox mice of Ptgdr (Kong et al., 2016) and Ptgfr (Wang et al., 2018) genes are already generated. The flox mice of Ptgdr2 gene are not yet available.

The pathophysiological function of PGD2 was extensively studied in the last two decades by pharmacological analyses with selective inhibitors for L-PGDS and H-PGDS, agonists and antagonists for DP, CRTH2 and FP receptors, as well as by in vivo analyses with various gene-manipulated mice of L-Pgds, HPgds, Ptgdr, Ptgdr2 and Ptgfr genes, as described in the later sections.

The cDNA and genome cloning of L-Pgds (Nagata et al., 1991; Igarashi et al., 1992) revealed that L-PGDS is a member of the lipocalin family, as judged by the homology of amino acid sequence and gene structure. The gene structure of L-Pgds (Igarashi et al., 1992) is remarkably analogous to those of other lipocalins, such as β-lactoglobulin, α2-urinary globulin, placental protein 14, and α1-microglobulin. All those proteins have the same numbers and sizes of exons and phase of splicing of introns. Positions of exon/intron junction of the L-Pgds gene are highly conserved and located around the same positions of those other lipocalins, in a multiple alignment of amino acid sequences despite a weak homology (Urade and Hayaishi, 2000a; Urade et al., 2006).

In 1993, the amino acid sequence of β-trace protein purified from human cerebrospinal fluid (CSF, Hoffmann et al., 1993) was found to be exactly identical to that of human L-PGDS (Nagata et al., 1991) after cleavage of its N-terminal hydrophobic signal sequence. β-Trace is a major protein of human CSF which was originally found in human CSF in 1961 (Clausen, 1961), but its molecular properties and physiological functions remained unidentified. In 1994, we purified L-PGDS from human CSF and confirmed that CSF L-PGDS is enzymatically and immunologically the same as β-trace (Watanabe et al., 1994).

Lipocalin-type prostaglandin D2 synthase is distributed in the CNS (Urade et al., 1989, 1993), male genital organs (Urade et al., 1989; Tokugawa et al., 1998) and human heart (Eguchi et al., 1997), and secreted into CSF (Hoffmann et al., 1993; Watanabe et al., 1994), seminal plasma (Tokugawa et al., 1998) and plasma during coronary circulation (Eguchi et al., 1997), respectively. L-PGDS maintains the binding activity of lipophilic ligands similar to other members of lipocalin superfamily (Urade et al., 2006), suggesting that L-PGDS acts as an extracellular transporter of lipophilic substances, as described below.

Ligand Binding Properties of Lipocalin-Type Prostaglandin D2 Synthase as an Extracellular Transporter

Supplementary Table 4 summarizes various types of ligands bound to L-PGDS and their binding affinities and kinetics. L-PGDS binds retinoids (Tanaka et al., 1997), thyroids (Beuckmann et al., 1999), and various types of lipophilic ligands. L-PGDS binds also amyloid β (Aβ) peptides (Kanekiyo et al., 2007), prevents the formation of amyloid fibrils (Kanekiyo et al., 2007; Kannaian et al., 2019) and disaggregates the fibrils (Kannaian et al., 2019), acting as a major Aβ chaperone in human CSF. L-PGDS binds PGD2 at a molar ratio of 1:2 with high and low affinities, suggesting that L-PGDS may function as an extracellular PGD2-transporter in the absence of substrate PGH2 (Shimamoto et al., 2021). All those ligands exhibit binding affinities to L-PGDS much higher than the Km value of PGH2 but do not potently inhibit the L-PGDS activity. L-PGDS has a large central hydrophobic cavity within a molecule, in which two to three molecules of those small ligands are captured. Docking analyses suggest that those ligands bind to the hydrophobic pocket at the bottom of a large central cavity of L-PGDS, which is different from the PGH2-binding catalytic pocket at the upper entrance of L-PGDS, as described later.

Binding of Lipophilic Hormones Including Retinoids and Thyroids

Lipocalin-type prostaglandin D2 synthase binds all-trans- and 9-cis-retinoic acids and all-trans- and 13-cis-retinal, but not retinol, with high affinities of Kd = 70–80 nM at a 1:1 molar ratio (Tanaka et al., 1997; Shimamoto et al., 2007; Inoue et al., 2009), similar to several other lipocalins. L-PGDS/β-trace is secreted into various body fluids, such as CSF of the brain (Hoffmann et al., 1993; Watanabe et al., 1994), interphotoreceptor matrix of the retina (Beuckmann et al., 1996), plasma (Eguchi et al., 1997), and seminal plasma (Tokugawa et al., 1998), suggesting that L-PGDS acts as an extracellular transporter of those retinoids within these compartments. Retinoid transporting function by L-PGDS is demonstrated in the study of glial migration (Lee et al., 2012) and the placode formation in Xenopus embryo (Jaurena et al., 2015) by using the Cys65Ala mutant without the PGD2 synthase activity (Urade et al., 1995).

Thyroid hormones, such as thyroxine (T4), 3-3′,5′-triiodo-L-thyronine (T3) and 3-3′,5-triiodo-L-thyronine (reverse T3), bind to L-PGDS with affinities of Kd = 0.7 to 3 μM (Beuckmann et al., 1999). L-PGDS expression is upregulated in rat brain through activation of a thyroid hormone/retinoic acid-responsive element in the promoter region of the rat L-Pgds gene (García-Fernández et al., 1998). Thyroid hormones upregulate L-Pgds gene expression in the male genital organs, the seminal vesicle and testis, of cat fish (Sreenivasulu et al., 2013). These results suggest that L-PGDS gene expression is controlled by its own ligands by an autonomic positive regulation mechanism. Fish L-PGDS ortholog does not contain an active thiol of Cys65 in mammalian L-PGDSs so that the fish L-PGDS does not show the PGD2 synthase activity but maintains the retinoid/thyroid-binding activity (Fujimori et al., 2006). Therefore, the fish L-PGDS is also predicted to function as a non-enzymic transporter of lipophilic hormones (Sreenivasulu et al., 2013).

Binding of Heme-Degradation Products and Heme

Lipocalin-type prostaglandin D2 synthase binds bilirubin and biliverdin (Beuckmann et al., 1999; Inoue et al., 2009; Miyamoto et al., 2009; Sreenivasulu et al., 2013), harmful degradation products of heme with high affinities (Kd of 20–40 nM) (Tanaka et al., 1997). This binding is also confirmed in the CSF of patients after subarachnoid hemorrhage, in which a part of biliverdin is covalently bound to the Cys65 residue, an active thiol of L-PGDS, as demonstrated by NMR (Inui et al., 2014). Therefore, L-PGDS scavenges those harmful heme-metabolites from CSF. L-PGDS also binds heme itself, as examined by NMR (Phillips et al., 2020). The heme-binding L-PGDS is associated with the pseudo-peroxidase activity, which is proposed to contribute to the anti-apoptotic activity of L-PGDS against the H2O2-induced cytotoxicity (Phillips et al., 2020).

Binding of Amyloid β Peptides

Lipocalin-type prostaglandin D2 synthase binds to Aβ peptides 1–40 and 1–42, and their fibrils with high affinities (Kd = 18–50 nM). The aggregation of Aβ peptides is crucial in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. L-PGDS recognizes a region of amino acid residues of 25–28 in Aβ peptides, the key region for conformational change to β-sheet structures (Kanekiyo et al., 2007). L-PGDS inhibits the spontaneous aggregation of Aβ (1–40) and Aβ (1–42) in a physiological concentration range from 1 to 5 μM in human CSF, and also prevents the seed-dependent aggregation of 50 μM Aβ (1–40) with Ki of 0.75 μM. When L-PGDS is removed from the human CSF by immunoaffinity chromatography with anti-(L-PGDS) IgG, the inhibitory activity toward Aβ (1–40) aggregation in human CSF decreases by 60%. Recombinant human L-PGDS disaggregates Aβ fibrils and dissolves many insoluble proteins existed in amyloid plaques in the brain of patients with Alzheimer’s disease (Kannaian et al., 2019). These results indicate that L-PGDS is a major endogenous Aβ-chaperone in the human brain.

Binding of Lipids, Gangliosides, and Lipophilic Drugs

Lipocalin-type prostaglandin D2 synthase also binds gangliosides, such as GM1 and GM2, with a high affinity with Kd = 65–210 nM (Mohri et al., 2006a). L-PGDS is upregulated in oligodendrocytes and a few neurons in the brain of murine models of various lysosomal storage diseases, such as Krabbe’s disease (Taniike et al., 1999; Mohri et al., 2006b), Tay–Sachs disease, Sandhoff disease, GM1 gangliosidosis and Niemann–Pick type C1 disease (Mohri et al., 2006a). These results suggest that L-PGDS plays a protective role on oligodendrocytes in scavenging harmful lipophilic substrates accumulated by malfunction of myelin metabolism in lysosomal storage diseases, as demonstrated by using double mutant mice with L-Pgds gene KO mice as shown later (Taniike et al., 2002).

Lipocalin-type prostaglandin D2 synthase also binds fatty acids (Zhou et al., 2010; Elmes et al., 2018) and various water insoluble drugs, including a sleeping pill Diazepam (Fukuhara et al., 2012a), a drug used for high blood pressure Telmisartan (Mizoguchi et al., 2015), anti-cancer drugs (Nakatsuji et al., 2015; Teraoka et al., 2017), cannabinoid receptor antagonists (Yeh et al., 2019), cannabinoid metabolites (Elmes et al., 2018), synthetic cannabinoids (Elmes et al., 2018), and anti-cholinergic drugs (Low et al., 2020), as listed in Supplementary Table 4. The binding affinities for those compounds are lower than those for retinoids, thyroids and Aβ. The drug-binding ability of L-PGDS is used for the drug delivery system and is recognize to induce off-target effects of anti-cholinergic drugs, such as Chlorpheniramine and Trazodone, to modulate the cytotoxicity of Aβ fibrils (Low et al., 2020).

Binding of Nicotinamide Coenzymes

Lipocalin-type prostaglandin D2 synthase binds NADPH, NADP+, and NADH, as examined by thermodynamic and NMR analyses. These hydrophilic ligands, especially NADPH, interact with the upper pocket of a ligand-binding cavity of L-PGDS with an unusual bifurcated shape (Qin et al., 2015). The binding affinity of L-PGDS for NADPH is comparable to that of NADPH oxidases. Therefore, L-PGDS may attenuate the NADPH oxidase activities through interaction with NADPH, being involved in anti-oxidative stress function of L-PGDS.

Binding of Substrate Analog and Product

Most recently, we demonstrated by isothermal titration assay and NMR analyses that L-PGDS binds a stable PGH2 analog U-46619 at two binding sites of high and low affinities with Kd values of 0.53 and 7.91 μM, respectively, and also its product PGD2 with 0.3 and 44 μM, respectively, in the hydrophilic catalytic pocket at the upper entrance of L-PGDS molecule (Shimamoto et al., 2021). The high affinity binding is lost in the Cys65Ala mutant of L-PGDS, indicating that the thiol group of Cys65 is important for high affinity binding of the substrate PGH2 and the product PGD2 to L-PGDS. On the other hand, the low affinity binding site has a wide binding spectrum for other PGs including PGE2 and PGF2α with comparable affinities. These results indicate the substrate-induced catalytic mechanism for L-PGDS. The sleep-inducing activity by an intracerebroventricular infusion of PGD2 is significantly reduced in L-Pgds gene KO mice than wild-type mice, suggesting that L-PGDS binds and transport PGD2 in the brain to stimulate effectively DP receptors in the sleep-promoting system (Shimamoto et al., 2021).

Structural Characterization of Lipocalin-Type Prostaglandin D2 Synthase by Nuclear Magnetic Resonance and X-Ray Crystallography

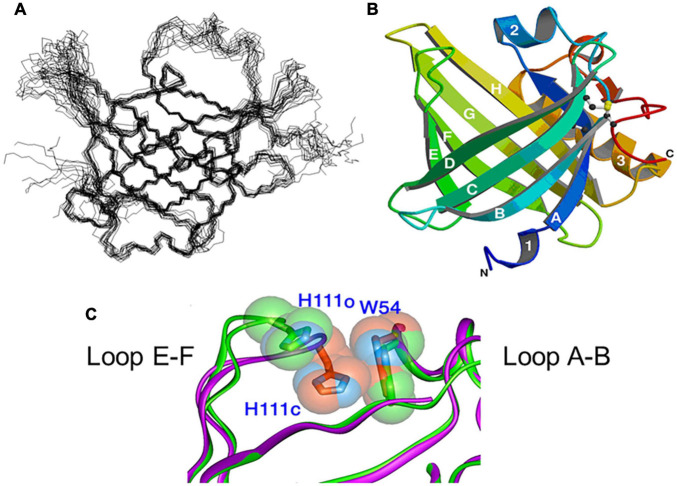

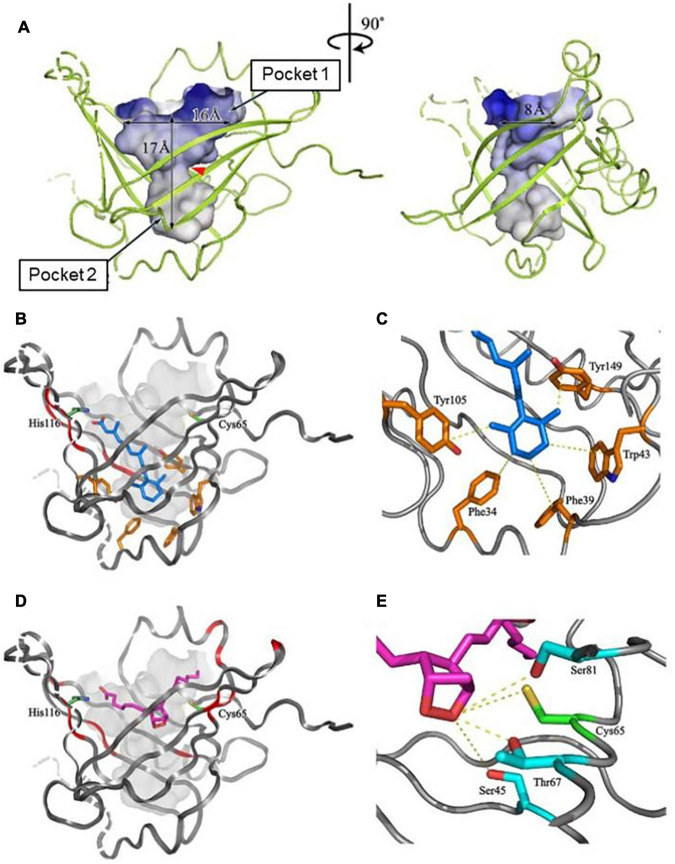

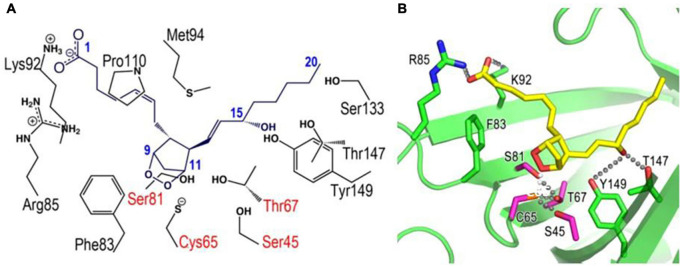

Figure 2 shows NMR (Figure 2A) and X-ray crystallographic structures (Figures 2B,C) of recombinant L-PGDS expressed in E. coli. We first determined in 2007 the solution structure of mouse L-PGDS by NMR (Shimamoto et al., 2007). L-PGDS possesses a typical lipocalin fold of β-barrel with two sets of β-sheet composed of each four strands of anti-parallel β-sheet and a 3-turn α-helix associated with the outer surface of the barrel. L-PGDS possesses a large central cavity with a flexible rid of a wide entrance opening to the upper end of the barrel. The central cavity of L-PGDS is larger than those of other lipocalins and contains two pockets (Figure 3A). NMR titration analyses demonstrate that all-trans-retinoic acid occupies the hydrophobic pocket 2 with amino acid residues important for the retinoid binding well conserved in other lipocalins (Figures 3B,C) and that PGH2 occupies the hydrophilic pocket 1 containing Cys65 and a hydrogen network of Ser45, Thr67, and Ser81 (Figures 3D,E).

FIGURE 2.

NMR (A) and X-ray crystallographic (B) structures of L-PGDS (Shimamoto et al., 2007; Kumasaka et al., 2009, respectively). (C) Overlapping views of the entrance of the catalytic pocket of the open (green) and closed (purple) conformers of L-PGDS (Kumasaka et al., 2009). Positions of EF-loop and H2-helix are indicated.

FIGURE 3.

The structure of a large central cavity of L-PGDS (A) and docking models of the complexes with all-trans-retinoic acid (B,C) or PGH2 (D,E) determined by NMR (Shimamoto et al., 2007). The molecule of all-trans-retinoic acid are shown in light blue (B,C). The carbon chain of PGH2 is shown in purple and a 9,11-endoperoxide group, in orange (D,E). Amino acid residues important for the ligand binding and the catalytic activity are shown in panels (C,E), respectively.

We determined in 2009 the crystal structures of mouse L-PGDS Cys65Ala mutant (Kumasaka et al., 2009) and revealed that L-PGDS exhibits two different conformers due to the movement of the flexible EF-loop (Figures 2A,C). One conformer of L-PGDS has an open cavity of the β-barrel and the other, a closed cavity (Figure 2C). The upper hydrophilic pocket 1 of the central cavity contains the catalytically essential Cys65 residue with a hydrogen bond network with Ser45, Thr67, and Ser81 (Figures 3E, 4). The SH titration analyses combined with site-directed mutagenesis (Kumasaka et al., 2009) demonstrate that Cys65 residue is activated by its interaction with Ser45 and Thr67. The crystal structure of L-PGDS confirmed that the lower compartment of the central cavity is composed of hydrophobic amino acid residues highly conserved among other lipocalins (Figure 3C).

FIGURE 4.

Docking models of L-PGDS complexes with PGH2 based on X-ray crystallography (Kumasaka et al., 2009). Amino acid residues important for interaction with PGH2 are shown in panel (A). R85, K92, F83, S82, C65, S45, T67, Y149, and T147 are shown in stick-model form in panel (B). Hydrogen bonding network around Cys65 and 15-hydroxy group of PGH2 are also indicated in panel (B).

X-ray crystallographic structures of human L-PGDS was also reported, in which fatty acids (Zhou et al., 2010) and polyethylene glycol used as precipitants (Perduca et al., 2014) are identified to be inserted into the central cavity of the molecule. The NMR structures of L-PGDS complexed with an L-PGDS-selective inhibitor AT56 (Irikura et al., 2009) or a variety of lipophilic (Qin et al., 2015) or hydrophobic (Shimamoto et al., 2007; Sreenivasulu et al., 2013; Inui et al., 2014; Kannaian et al., 2019; Low et al., 2020; Phillips et al., 2020) ligands were also already reported (Supplementary Table 4). Those structural information is useful for designing inhibitors specific for L-PGDS.

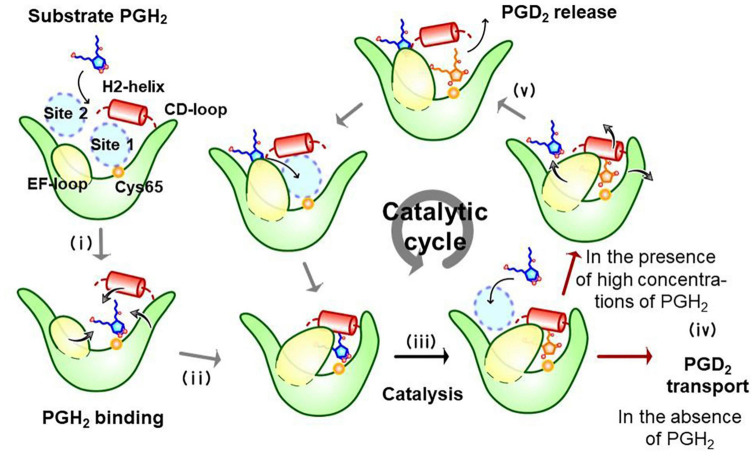

Figure 5 shows a substrate-induced product release mechanism for L-PGDS (Shimamoto et al., 2021). L-PGDS has two binding sites for the substrate PGH2 and the product PGD2 in the pocket 1 of the upper part of the cavity. Site 1 is the catalytic site containing Cys65 and site 2, the non-catalytic site. Apo-form of L-PGDS has a wide open entrance, through which PGH2 enters to the pocket 1. PGH2 binds to the site 1 at step (i). H2-helix, CD-loop, and EF-loop of L-PGDS interact with PGH2 so that the cavity is closed at step (ii). The closed conformation of L-PGDS holds the 9,11-endoperoxide group of PGH2 to interact with the thiol group of the catalytic Cys65. The catalytic reaction occurs to produce PGD2 at step (iii). After the catalytic reaction, PGD2 still binds to site 1 at the high affinity with Kd of 0.3 μM (Supplementary Table 4). In the absence of PGH2, L-PGDS acts as a carrier of PGD2 as shown at step (iv). In the presence of excess concentrations of PGH2, the next molecule of PGH2 binds to site 2, inducing movement of CD-loop to open site 1 and release PGD2 at step (v). PGH2 then move from site 2 to site 1 and the catalytic cycle starts again (Shimamoto et al., 2021).

FIGURE 5.

Substrate-induced product-release mechanism for L-PGDS (Shimamoto et al., 2021).

Post transcriptional modification of L-PGDS/β-trace in human CSF is identified by a proteoform analysis (Zhang et al., 2014) to be N-glycans at Asn51 and Asn78 with different N-glycan compositional variants, a core-1 HexHexNAc-O-glycan at Ser29, acetylation at Lys38 and Lys160, sulfonation at Ser63 and Thr164, and dioxidation at Cys65 and Cys167 after cleavage of an N-terminal signal sequence to Ala22. Two N-truncated forms of L-PGDS from Gln31 and Phe34 exist in human urine (Nagata et al., 2009).

A loop structure of residues 55–63 between β-strand A and B of L-PGDS is proposed to be homologous to a sequence domain in apolipoprotein E responsible for binding to low-density lipoprotein (LDL) receptor (Portioli et al., 2017). Two potential GTPase Rab4-binding sites are proposed to locate residues 75–98 and 85–92 within β-strand B and C of human L-PGDS (Binda et al., 2019).

Cell Culture Studies of Lipocalin-Type Prostaglandin D2 Synthase

Lipocalin-type prostaglandin D2 synthase is constitutively expressed in several cell lines including human brain-derived TE671 cells, human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells, mouse adipocytic 3T3-L1 cells, and others. Several types of primary cultured cells, such as leptomeningeal cells, vascular endothelial cells, bone marrow-derived macrophages or mast cells are also used to study the regulation mechanism of L-Pgds gene and the functional analyses of L-PGDS, as summarized in Supplementary Table 5.

L-Pgds Gene Regulation in the Central Neuronal Cells

In mouse neuronal GT1-7 cells, L-PGDS is induced by dexamethasone (García-Fernández et al., 2000). The L-PGDS induction is suppressed by 12-O-tetradecanoyl phorbol 13-acetate (TPA), whereas TPA induces the synthesis of PGs in many tissues. The L-PGDS induction by glucocorticoids is also found in mouse adipocytic 3T3-L1 cells (Yeh et al., 2019). Dexamethasone and glucocorticoids are known to suppress inflammation by inhibition of PG production. However, PGD2 produced by L-PGDS may, in part, be also involved anti-inflammatory effects by those hormones.

In rat leptomeningeal cells, the Notch-Hes signal represses L-Pgds gene expression by interaction with an atypical E-box (aE-box) in the promoter region. IL-1β upregulates L-Pgds gene expression through the NF-kB pathway at two NF-kB sites of the L-Pgds gene (Fujimori et al., 2003) and by contact with astrocytes (Fujimori et al., 2007b).

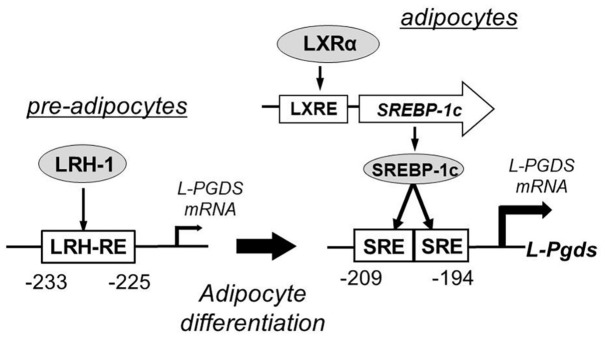

In human TE671 cells, the Notch-Hes signal represses L-Pgds gene expression by interaction with an N-box in the promoter region and the AP-2β binding to the AP-2 element in the promoter region is involved in maintenance of L-Pgds gene expression (Fujimori et al., 2005). TPA induces L-PGDS in TE671 cells. Protein kinase C phosphorylates Hes-1, inhibits DNA binding of Hes-1 to the N-box, and induce L-PGDS. Activation of the AP-2β function is involved in up-regulation of L-Pgds gene expression. The aE-box is critical for transactivation of the L-Pgds gene in TE671 cells. Upstream stimulatory factor (USF)-1 binds to the aE-box in intron 4 of the human L-Pgds gene and activates L-Pgds gene expression. Binding of AP-2β in the promoter also cooperatively contributes to the transactivation of L-Pgds gene (Fujimori and Urade, 2007). Serum starvation induces PGD2 production in TE671 cells through transcriptional activation of Pghs-2 and L-Pgds genes. The serum starvation up-regulates L-Pgds gene expression by binding of USF-1 to aE-box within intron 4. The USF1 expression is enhanced through activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in TE671 cells (Fujimori et al., 2008). Figure 6 summarizes the transcriptional regulation of the human L-Pgds gene in TE671 cells.

FIGURE 6.

Regulatory mechanism of human L-Pgds gene expression in brain-derived TE671 cells (Fujimori et al., 2005, 2008; Fujimori and Urade, 2007). L-Pgds gene expression is lowered by the Notch-Hes signal via an N-box, but enhanced by AP-2β through the AP-2 element. TPA activates PKC, followed by phosphorylation of Hes-1 to cancel the binding of Hes-1 to the N-box. Upstream stimulatory factor-1 (USF-1) activates L-Pgds gene expression through the atypical E-box (aE-box) in the intron 4. Serum starvation induces further L-Pgds gene expression.

In human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells, L-PGDS prevents neuronal cell death caused by oxidative stress (Fukuhara et al., 2012b). An NF-kB element in the proximal promoter region of L-Pgds gene mediates paraquat-induced apoptosis of these cells (Fujimori et al., 2012a).

In U251 glioma cell line expressing estrogen receptor (ER) α, estradiol (10–11 M) increases the promoter activity of L-Pgds gene. Conditioned media from estradiol-treated neurons increases the L-Pgds gene promoter activity in glial cells, suggesting that a paracrine factor released from the neighboring neurons after stimulation of estrogen induces L-PGDS in glial cells (Devidze et al., 2010).

In primary cultured astrocytes, microglial cells, and fibroblasts (Lee et al., 2012), L-PGDS accelerates the migration of these cells and changes the morphology to the characteristic phenotype in reactive gliosis. Activation of AKT, RhoA, and JNK pathways mediates L-PGDS-induced cell migration. L-PGDS interacts with myristoylated alanine-rich protein kinase C substrate (MARCKS) and promotes the cell migration in a PGD2-independent manner, because that the inactive Cys65Ala mutant without the PGD2 synthase activity shows the same effect.

L-Pgds Gene Regulation in Vascular Cells

Fluid shear stress induces L-PGDS in human vascular endothelial cells (Taba et al., 2000). c-Fos and c-Jun bind to the AP-1 binding site of the 5′-promoter region of the L-Pgds gene to induce L-PGDS. Shear stress elevates the c-Jun phosphorylation level in a time-dependent manner, similar to that of L-Pgds gene expression. A c-Jun N-terminal kinase inhibitor decreases the c-Jun phosphorylation, DNA binding of AP-1, and shear stress-induced L-Pgds gene expression (Miyagi et al., 2005). Homozygosity for the C variant of the T-786C single-nucleotide polymorphism of the human endothelial NO synthase gene exhibits a reduced endothelial cell capacity to generate NO and is less sensitive to fluid shear stress. In the CC-genotype of endothelial cells, fluid shear stress elicits a marked rise in Pghs-2 and L-Pgds gene expression (Urban et al., 2019). These results suggest that the increased production of PGD2 is the reason why CC-genotype endothelial cells maintain the robust anti-inflammatory characteristics, despite a reduced capacity to produce NO.

Exogenously added L-PGDS induces apoptosis of epithelial, neuronal and vascular smooth muscle cells. L-PGDS-induced apoptosis is inhibited by mutations in a glycosylation site Asn51, a putative protein kinase C phosphorylation site Ser106, and the enzymatic active site Cys65, although the action mechanism remains unclear (Ragolia et al., 2007).

L-Pgds Gene Regulation in Adipocytes

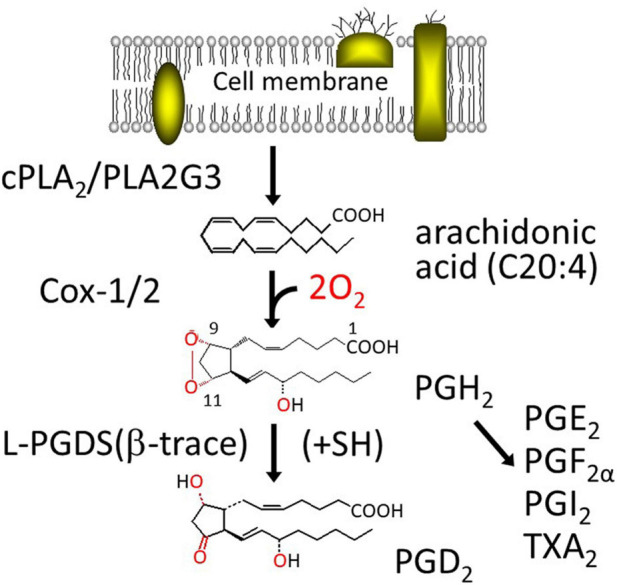

Lipocalin-type prostaglandin D2 synthase is involved in adipocyte differentiation of mouse 3T3-L1 cells (Fujimori et al., 2007a). A responsive element for liver receptor homolog-1 (LRH-1) in the promoter region of the L-Pgds gene plays a critical role in L-Pgds gene expression in pre-adipocytes of 3T3-L1 cells. Two sterol regulatory elements (SREs) in the promoter region act as cis-elements for activation of L-Pgds gene. Synthetic liver X receptor agonist T0901317 activates the expression of SRE-binding protein-1c (SREBP-1c) and upregulates L-Pgds gene expression in these cells. LRH-1 and SREBP-1c bind to their respective binding elements in the promoter of L-Pgds gene and increase L-Pgds gene expression in pre-adipocytes and adipocytes, respectively, of 3T3-L1 cells. Figure 7 summarizes the transcriptional regulation of the mouse L-Pgds gene in preadipocytes and adipocytes of mouse 3T3-L1 cells.

FIGURE 7.

Transcriptional regulation of mouse L-Pgds gene in adipocyte 3T3-L1 cells (Fujimori et al., 2007a). L-Pgds gene expression is activated by liver receptor homolog-1 (LRH-1), one of orphan nuclear receptors, through the LRH-responsive element (LRH-RE) in pre-adipocytes. In the differentiated adipocytes, activation of liver X receptor (LXR) elevates the expression of sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1 (SREBP-1c) through the LXR-responsive element (LXRE), and then SREBP-1c strongly enhances the L-Pgds gene expression via two sterol regulatory elements (SREs) in the promoter region of L-Pgds gene.

Gene knockdown of L-Pgds by antisense L-Pgds gene in pre-adipocytes stimulates fat storage during the maturation stage of these cells (Chowdhury et al., 2011). In these cells, Δ12- prostaglandin J2 (Δ12- PGJ2), a dehydrated product of PGD2 produced by L-PGDS, activates adipogenesis through both PPARγ-dependent and -independent pathways (Fujimori et al., 2012b), although the J series of PGD2 is not physiologically produced in vivo as described below.

Prostaglandin D2 is relatively unstable in water, as compared with PGE2 and PGF2α, both of which are chemically very stable for several months to years. PGD2 is spontaneously dehydrated in water to prostaglandin J2 (PGJ2), Δ12-PGJ2 and 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-PGJ2 (15d-PGJ2). These cyclopentene PGs with a O=C-C=C- bond are chemically reactive with various SH and amino groups to make conjugates. As d15-PGJ2 acts as a ligand of PPARγ in vitro, several reports emphasize the importance of d15-PGD2 in vivo. However, those cyclopentene PGs are not produced physiologically in vivo and are artificially generated from PGD2 during extraction and purification for measurement. Those cyclopentene PGs are cytotoxic and induce apoptosis of cultured cells because of their massive reactivities. We have to be careful about the artificial cytotoxic effect of those dehydrated PGD2 products in the cell culture system. In cases that the target receptor of PGD2 is predicted, it is desirable to use chemically stable agonists, rather than PGD2 itself.

Adipocytes dominantly express CRTH2 receptors (Wakai et al., 2017). CRTH2 antagonist, but not DP antagonist, suppresses the PGD2-elevated intracellular triglyceride level. CRTH2 agonist 15R-15-methyl PGD2 increases the mRNA levels of the adipogenic and lipogenic genes, decreases the glycerol release level, and represses the forskolin-mediated increase of cAMP-dependent protein kinase A activity (PKA) and phosphorylation of hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL). The lipolysis is enhanced in the adipocytes differentiated from embryonic fibroblasts of CRTH2 KO mice. These results indicate that PGD2 produced by L-PGDS suppresses the lipolysis by repression of the cAMP-PKA-HSL axis through CRTH2 receptors in adipocytes in an autocrine manner.

Glucocorticoid induces L-Pgds gene expression and leptin production in differentiated primary preadipocytes (Yeh et al., 2019). L-Pgds siRNA and L-PGDS inhibitor AT56 suppress glucocorticoid-induced leptin production, whereas overexpression of L-Pgds gene enhances leptin production. The L-PGDS-leptin pathway may be involved in undesired effects of clinical used glucocorticoid including obesity. In human mesenchymal stroma cells used in cellular therapies, L-PGDS is involved in differentiation of adipocytes, suggesting that L-Pgds gene expression is a potential quality marker for these cells, as it might predict unwanted adipogenic differentiation after the transplantation (Lange et al., 2012).

Lipocalin-Type Prostaglandin D2 Synthase Studies in Skeletal Muscle Cells

Lipocalin-type prostaglandin D2 synthase stimulates glucose transport of the insulin-sensitive rat skeletal muscle cell line L6 at the basal level and after insulin-stimulation. L-PGDS increases translocation of glucose transporter 4 to the plasma membrane, suggesting that L-PGDS, via production of PGD2, is an important mediator of muscle and adipose glucose transport, which plays a significant role in the glucose intolerance associated with type 2 diabetes (Ragolia et al., 2008).

L-Pgds Gene Regulation in Peripheral Nervous Cells

L-Pgds gene is the most upregulated gene in the primary culture of rat dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons infected with the intracellular domain of neuregulin 1 type III, a member of the neuregulin family of growth factors. DRG neurons secrete L-PGDS and PGD2, the latter of which stimulates CRTH2 receptors and enhances myelination of Schwann cells (Trimarco et al., 2014).

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulation increases L-Pgds gene expression in intestinal neurons and glial cells in the primary culture of rat enteric nervous system. L-PGDS inhibitor AT56 inhibits PGD2 production in the primary culture treated with LPS. As Pghs-2 and L-Pgds gene expression increase in the inflamed colonic mucosa of patients with active Crohn’s disease, the L-PGDS pathway may be a new therapeutic target in this disease (Le Loupp et al., 2015).

L-Pgds Gene Regulation in Macrophages

Incubation with LPS or Pseudomonas upregulates L-Pgds gene expression in mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages and macrophage cell line RAW 264.7 cells, in which AP-1 and p53 regulate the L-Pgds gene expression positively and negatively, respectively (Joo et al., 2007). Binding of PU.1, a transcription factor essential for macrophage development and inflammatory gene expression, to the cognate site in the L-Pgds gene promoter mediates the L-PGDS induction. LPS stimulation triggers TLR4 signaling and activates casein kinase II (CKII). CKII phosphorylates PU.1 at Ser148. The activated phosphorylated PU.1 binds to its cognate site in the promoter. The TLR4 signaling also activates JNK and p38 kinase that phosphorylate and activate cJun. Activated phosphorylated cJun binds to both PU.1 and the AP-1 site of the promoter. PU.1 and cJun form a transcriptionally active complex in the L-Pgds gene promoter, leading to L-Pgds gene expression (Joo et al., 2009). Therefore, L-PGDS is also important for the innate immunity.

L-Pgds Gene Regulation in Chondrocytes

L-Pgds gene expression is upregulated in human primary cultured chondrocytes by treatment with IL-1β. Inhibitors of MAPK p38, c-jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), and the NF-κB/Notch signaling pathways suppress the L-Pgds gene upregulation (Zayed et al., 2008).

Lipocalin-Type Prostaglandin D2 Synthase Studies in Mast Cell Maturation

Lipocalin-type prostaglandin D2 synthase in fibroblasts is important for maturation of mouse and human mast cells (Taketomi et al., 2013). Mast cells secrete a group III phospholipase A2 (PLA2G3), a mammalian ortholog of anaphylactic bee venom phospholipase A2. The secreted PLA2G3 couples with L-PGDS in neighboring fibroblasts to provide PGD2. The PGD2 produced by fibroblasts stimulates DP receptors on mast cells to facilitate maturation of mast cells. Mast cells maturation and anaphylaxis are impaired in KO mice of PLA2G3, L-PGDS or DP, mast cell–deficient mice reconstituted with PLA2G3-null or DP-null mast cells, or mast cells cultured with L-Pgds gene–ablated fibroblasts. The PLA2G3-L-PGDS-DP paracrine axis is important for the innate immunity and inflammation by the mast cell-fibroblast interaction.

Lipocalin-Type Prostaglandin D2 Synthase Studies in Cells of the Skin

Follicular melanocytes in the mouse skin express L-PGDS. B16 mouse melanoma cells express L-PGDS under the control of microphthalmia-associated transcription factor (MITF) responsible for differentiation of melanocytes (Takeda et al., 2006). In human epidermal keratinocytes, antimycotics induce PGD2 release and suppress the expression of thymic stromal lymphopoietin, the NF-kB activity, and IkBα degradation induced by poly I:C plus IL-4. L-PGDS inhibitor AT-56 counteracts the antimycotic-induced suppression of thymic stromal lymphopoietin production and the NF-kB activity (Hau et al., 2013).

Lipocalin-Type Prostaglandin D2 Synthase Studies in Cancer Cells

Overexpression of Yes-associated protein 1 (YAP) suppresses L-Pgds and Ptgdr2 gene expression in gastric cancer cells. Overexpression of L-Pgds and Ptgdr2 genes decreases proliferation and self-renewal of gastric cancer cells by YAP. These results indicates that YAP inhibits L-Pgds and Ptgdr2 gene expression to promote self-renewal of gastric cancer cells (Bie et al., 2020). Chemotherapeutics induce Cox-2 and lead apoptosis of human cervical carcinoma cells. L-Pgds gene knockdown by siRNA prevents the chemotherapeutics-induced apoptosis, suggesting that the apoptosis occurs through PGD2 production by L-PGDS (Eichele et al., 2008).

Lipocalin-Type Prostaglandin D2 Synthase Studies in Cells of the Prostate Gland

Bisphenol A, a synthetic plasticizer widely used to package daily necessities, induces Pghs2 and L-Pgds gene expression in human prostate fibroblasts and epithelial cells. Cox-2 inhibitor NS398 and L-PGDS inhibitor AT56 suppress the cell proliferation enhanced by bisphenol A and increase apoptosis of those cells. Thus, Cox-2 and L-PGDS mediate low-dose bisphenol A-induced prostatic hyperplasia through pathways involved in cell proliferation and apoptosis (Wu et al., 2020).

Lipocalin-Type Prostaglandin D2 Synthase Studies in Seminal Plasma and Oviduct Fluid

The seminal plasma and oviduct fluid contain L-PGDS. Pretreatment of bovine sperm and/or oocytes with anti-L-PGDS antibody inhibits in vitro fertilization and increases sperm-oocyte binding (Gonçalves et al., 2008a). Anti-L-PGDS antibody reacts with cow oocytes incubated with oviduct fluid. Pretreatment of oocytes with anti-L-PGDS antibody inhibits sperm binding, fertilization and embryonic development in vitro (Gonçalves et al., 2008b).

Amphibian Ortholog of Lipocalin-Type Prostaglandin D2 Synthase and Its Function During Development of Xenopus Embryo

Amphibian ortholog of L-Pgds gene is identified and its protein is expressed in Xenopus A6 cells. Amphibian ortholog of L-PGDS is associated with both PGD2 synthase activity and all-trans-retinoic acid-binding activity (Irikura et al., 2007). During development of Xenopus embryo, amphibian L-Pgds gene expression is induced by zinc-finger transcription factor Zic 1 specifically at the anterior neural plate and allows for the localized production and transport of retinoic acid, which in turn activates a cranial placode developmental program in neighboring cells (Jaurena et al., 2015). This effect is reproduced by the Cys65Ala mutant of amphibian L-PGDS, indicating that amphibian L-PGDS functions independently of its enzymatic activity yet as an extracellular retinoic acid transporter.

Intracellular Interaction of Lipocalin-Type Prostaglandin D2 Synthase With D Type of Prostanoid Receptors in HEK293 or HeLa Cells

Lipocalin-type prostaglandin D2 synthase interacts intracellularly with DP receptors co-expressed in HEK293 or HeLa cells. L-PGDS or its Cys65Ala mutant promotes cell surface expression of DP receptors, but not of other G-protein coupled receptors including CRTH2 receptors. Interaction of L-PGDS with the C-terminal MEEVD residues of Hsp90 within cells is crucial for export of DP receptors to the cell surface. Co-expression of L-PGDS with DP receptors and Hsp90 promotes PGD2 synthesis. Depletion of L-Pgds gene decreases DP receptor-mediated ERK1/2 activation. L-PGDS inhibitor AT-56 or DP antagonist BWA868C inhibit L-PGDS-induced ERK1/2 activation. These results indicate that L-PGDS increases the DP receptor-ERK1/2 complex formation and increases DP receptor-mediated ERK1/2 signaling as an intracrine/autocrine signaling mechanism (Binda et al., 2014).

Depletion of endogenous L-Pgds gene in HeLa cells decreases recycling of endogenous DP receptors to the cell surface after agonist-induced internalization. L-Pgds gene overexpression increases the recycling of DP receptors. Depletion of endogenous GTPase Rab4 prevents L-PGDS-mediated recycling of DP receptors. L-Pgds gene depletion inhibits Rab4-dependent recycling of DP receptors. These results indicate that L-PGDS and Rab4 are involved in the recycling of DP receptors. DP receptor stimulation promotes interaction between the intracellular C terminus of DP receptors with Rab4 to form the L-PGDS/Rab4/DP complexes. L-PGDS interacts preferentially with the inactive, GDP-locked Rab4S22N variant rather than with wild-type Rab4 or with constitutively active Rab4Q67L proteins. L-PGDS is involved in Rab4 activation after DP stimulation by enhancing GDP-GTP exchange on Rab4. The region of amino acid residues between 85 and 92 in L-PGDS is proposed to be involved in the interaction with Rab4 and DP recycling, as assessed by deletion mutants and using synthetic peptides (Binda et al., 2019). These mechanisms may amplify the autocrine L-PGDS/PGD2/DP receptor function.

Mammalian Experiments for the Study of Lipocalin-Type Prostaglandin D2 Synthase

Lipocalin-type prostaglandin D2 synthase is enriched in the CNS, male genital organs, skin of various mammals, and the human heart; and involved in a variety of pathophysiological function. Recent studies using various gene-manipulated mice including systemic or cell/tissue-selective KO mice of L-Pgds and Ptgdr, Ptgdr2, Ptgfr genes explore the understanding of the function of L-PGDS, as summarized in Supplementary Table 6.

Lipocalin-Type Prostaglandin D2 Synthase-Mediated Functions in Central Nervous System

In the CNS, L-PGDS is predominantly localized in leptomeningeal cells (arachnoid trabecular cells, arachnoid barrier cells and arachnoid border cells), choroid plexus epithelial cells and oligodendrocytes (Urade et al., 1993; Beuckmann et al., 2000), and is secreted into the CSF to be β-trace (Hoffmann et al., 1993; Watanabe et al., 1994). PGD2 is the most potent endogenous sleep-inducing substance (Urade and Hayaishi, 2011) as well as a potent inflammatory mediator (Urade and Hayaishi, 2000b). L-Pgds gene KO and TG mice show normal sleep pattern, suggesting that sleep of these mice is normalized by unknown compensation mechanism against gene-manipulation. PGD2-induced sleep is mediated by both adenosine A2A receptor-dependent and independent systems (Zhang et al., 2017a). Several cytokines, such as IL-1β and TNFα induce sleep in a PGD2-independent manner (Zhang et al., 2017b), Therefore, adenosine and those cytokine systems may be involved in sleep maintenance by compensation for the L-Pgds gene deletion. RNA-Seq analyses of the brain of KO mice of L-Pgds and/or ptgdr genes will provide the information to understand the compensation mechanism.

However, a variety of abnormality was detected in L-Pgds gene-manipulated mice after any stimulation or pathological conditions. L-Pgds gene KO mice exhibit many abnormalities in the CNS function including regulation of sleep, pain, neural protection, food intake, and others as follows:

Pain Regulation

L-Pgds gene KO mice do not show allodynia (touch-evoked pain) after an intrathecal administration of PGE2- or bicuculline, a GABAA-antagonist (Eguchi et al., 1999). The PGE2- or bicuculline-induced allodynia is reproduced in L-Pgds gene KO mice by administration of subfemtomole amount of PGD2 (Eguchi et al., 1999). In a rat lumbar disk herniation model with thermomechanical allodynia and degeneration of DRG, overexpression and knockdown of L-Pgds gene, respectively, attenuates and worsens the allodynia and tissue degradation (Xu et al., 2021).

Sleep Regulation

Human L-Pgds gene-overexpressing TG mice show sleep attack with a transient increase in PGD2 content in the brain after pain stimulation for tail cutting (Pinzar et al., 2000). L-Pgds or Ptgdr gene KO mice do not show the rebound sleep after sleep deprivation (Hayaishi et al., 2004). Thus, the L-PGDS/DP system is crucial for the homeostatic regulation of sleep.

An intraperitoneal administration of an L-PGDS inhibitor SeCl4 decreases the PGD2 concentration in the brain without changing the PGE2 and PGF2α concentrations and induces complete insomnia during 1hr after the administration. L-Pgds, L-Pgds/Hpgds double or Ptgdr gene KO mice do not show the SeCl4-induced insomnia, whereas Hpgds or Ptgdr2 gene KO mice show the SeCl4-induced insomnia, indicating that the insomnia depends on PGD2 produced by L-PGDS and recognizes by DP receptors (Qu et al., 2006). Pentylenetetrazole induces seizure in wild-type mice with a remarkable increase in the PGD2 concentration in the brain and induces excess sleep after seizure. The postictal sleep is not induced in L-Pgds, L-Pgds/Hpgds double or Ptgdr KO mice but observed in Hpgds and Ptgdr2 KO mice, indicating that the sleep depends on the L-PGDS/PGD2/DP receptors system (Kaushik et al., 2014).

The SeCl4-induced insomnia is disappeared in leptomeninges-selective L-Pgds gene KO mice, which is generated by conditional gene depletion after injection of adeno-associated virus (AAV)-Cre vectors into the subarachnoidal space of newborn L-Pgds gene flox mice, but found in oligodendrocytes- or choroid plexus-specific conditional KO mice (Cherasse et al., 2018). These results indicate that the leptomeningeal L-PGDS is important for maintenance of physiological sleep.

Estradiol differentially regulates L-Pgds gene expression in the female mouse brain. Estradiol increases L-Pgds gene expression in the arcuate and ventromedial nucleus of the medial basal hypothalamus, a center of neuroendocrine secretions, and reduced in the ventrolateral preoptic area, a sleep center (Mong et al., 2003). Estradiol benzoate reduces L-Pgds gene expression in the sleep center and induces high motor activity in ovarectomized female mice (Ribeiro et al., 2009).

Protection of Neurons and Glial Cells

Lipocalin-type prostaglandin D2 synthase plays important roles for protection of neurons and glial cells under various pathological conditions. L-Pgds gene expression is upregulated in oligodendrocytes in twitcher mice as a model of human globoid cell leukodystrophy (Krabbe disease) caused by the mutation of galactosylceramidase (GALC). In double mutant of GALCtwi/twi L-Pgds gene KO mice, many neurons and oligodendrocytes exhibit apoptosis, indicating that L-PGDS protect neurons and glial cells against apoptotic loss cause by accumulation of cytotoxic glycosylsphingoid psychosine produced by the lack of GALC (Taniike et al., 2002). L-Pgds gene expression is upregulated in oligodendrocytes in mouse models of a variety of lysosomal storage disorders, such as Tay–Sachs disease, Sandhoff disease, GM1 gangliosidosis, and Niemann–Pick type C1 disease (Mohri et al., 2006a), suggesting that L-PGDS is involved in pathology of these diseases or may protect neurons and glial cells also in these diseases.

In a model of the hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy of neonates, L-PGDS is induced as an early stress protein and protects neurons in neonatal mice (Taniguchi et al., 2007). L-Pgds gene KO mice exhibit greater infarct volume and brain edema after cerebral ischemia than wild type mice (Saleem et al., 2009). In neonatal rats, dexamethasone upregulates L-Pgds gene expression in the brain and protects hypoxic-ischemic brain injury. L-PGDS inhibitor SeCl4 or DP antagonist MK-0524 suppress the neuroprotective effect (Gonzalez-Rodriguez et al., 2014). In chronic intermittent hypoxia of adult rats, L-Pgds gene expression is increased in the brain from the second week (Shan et al., 2017). L-Pgds gene expression is upregulated in COX-2-overexpressing APP/PS1 mice, which exhibit more severe amyloid fibril formation than APP/PS-1 mice (Guan et al., 2019). These results suggest that L-PGDS is involved in the neuroprotection against the stress condition or the recovery from brain damage.

Amyloid β Clearance

Lipocalin-type prostaglandin D2 synthase binds Aβ (1–40) and Aβ (1–42) peptides at high affinities (Supplementary Table 4) and prevents their fibril formation in vitro (Kanekiyo et al., 2007; Kannaian et al., 2019). L-PGDS is a major CSF component responsible for prevention of Aβ fibril formation in human CSF in vitro (Kanekiyo et al., 2007). Infusion of Aβ (1–42) peptide into the brain attenuates and worsens, respectively, the Aβ fibril precipitation in the brain in L-Pgds gene KO and human L-Pgds gene-overexpressing TG mice, as compared with each wild-type mice (Kanekiyo et al., 2007). These results indicate that L-PGDS prevents Aβ fibril formation in the brain in vivo.

Depression-Related Behavior

Chronic stress via corticosterone treatment increases mRNA levels of COX-2 and L-PGDS in the brain. Ptgdr2 gene-KO mice show antidepressant-like activity in a chronic corticosterone treatment-induced depression. The pharmacological inhibition of CRTH2 receptors in wild-type mice with a dual antagonist for CRTH2/TXA receptors, ramatroban, rescues depression-related behavior in chronic corticosterone-, LPS-, and tumor-induced pathologically relevant depression models. These results indicate that the L-PGDS/PGD2/CRTH2 axis is involved in progression of chronic stress-induced depression (Onaka et al., 2015).

Light-Induced Phase Advance

L-Pgds gene KO mice exhibit impaired light-induced phase advance, while they show normal phase delay and nonvisual light responses. Ptgdr2 gene KO mice or CRTH2 antagonist CAY10471-administered wild-type mice also show impaired light-induced phase advance. These results indicate that L-PGDS is involved in a mechanism of light-induced phase advance via CRTH2 signaling (Kawaguchi et al., 2020).

Food-Intake

Several reports demonstrate the involvement of L-PGDS in food intake. Fasting upregulates Ptgs2 and L-Pgds gene expression in the hypothalamus of mice, in which the orexigenic center exists. Intracerebroventricular administration of PGD2 or DP agonist stimulates food intake. DP antagonist, antisense oligonucleotide of DP receptors or an antagonist of neuropeptide Y (NPY) receptors suppress the orexigenic effects. Thus, the L-PGDS/DP/NPY axis regulates the food intake (Ohinata et al., 2008). Oral administration of a δ opioid peptide rubiscolin-6 stimulates food intake in wild-type and Hpgds gene KO mice, but not L-Pgds or Ptgdr gene KO mice. The orexigenic activity is found in L-Pgdsflox/Nes-Cre mice, which lack L-Pgds gene in neurons and glial cells within the brain parenchyma but maintain L-Pgds gene in leptomeninges, choroid plexus and cerebroventricular ependymal cells. Thus, PGD2 produced by L-PGDS in leptomeningeal cells or cerebroventricular ependymal cells mediates the orexigenic effect (Kaneko et al., 2012). The activation of central δ-opioid receptor stimulates normal diet intake mediated by the orexigenic L-PGDS/PGD2/DP system but conversely suppresses high-fat diet intake through α-MSH/CRF pathway in a PGD2-independent manner (Kaneko et al., 2014).

Lipocalin-Type Prostaglandin D2 Synthase in Peripheral Nervous System

Lipocalin-type prostaglandin D2 synthase and H-PGDS exist in neurons and glial cells, respectively, of chicken DRG (Vesin et al., 1995) and play an important role for maintenance of peripheral nervous system (PNS). L-Pgds gene KO mice exhibit hypomyelination of Schwann cells in PNS (Trimarco et al., 2014). In the primary culture, DRG neurons produce L-PGDS and PGD2, secrete these substances into the extracellular space, and stimulates myelination of Schwann cells. The L-PGDS inhibitor AT56 or gene knockdown of CRTH2 by shRNA suppresses the myelination of Schwann cells. Therefore, the L-PGDS/PGD2/CRTH2 axis plays important roles as a paracrine signal for development and maintenance of myelination of PNS (Trimarco et al., 2014). L-PGDS is necessary for macrophage activity and myelin debris clearance in a non-cell autonomous way during the resolution of PNS injury. In late phases of Wallerian degeneration, L-PGDS regulates the blood–nerve barrier permeability and SOX2 expression in Schwann cells, prevents macrophage accumulation, and exerts an anti-inflammatory role (Forese et al., 2020). Thus, L-PGDS has a different role during development and after injury in the PNS.

Lipocalin-Type Prostaglandin D2 Synthase in Lung Inflammation

Prostaglandin D2 is an important inflammatory mediator involved in allergic asthma and L-PGDS is involved in the pro- and anti-inflammatory functions. Eosinophilic lung inflammation and Th2 cytokine release in ovalbumin-induced asthma model are enhanced in human L-Pgds gene-overexpressing TG mice (Fujitani et al., 2010). LPS or Pseudomonas treatment upregulates L-Pgds gene expression in the lung and alveolar macrophages. Removal of Pseudomonas from the lung is accelerated in the TG mice, or by intratracheal instillation of PGD2 to wild type mice, but impaired in L-Pgds gene KO mice. Thus, L-PGDS plays a protective role against the bacterial infection (Joo et al., 2007). L-PGDS inhibitor AT56 suppresses accumulation of eosinophils and monocytes in the broncho-alveolar lavage fluid in an antigen-induced asthma model of Hpgds gene KO mice. PGD2-produced by L-PGDS is involved in inflammatory cell accumulation in the alveolar lavage fluid (Irikura et al., 2009). Intratracheal administration of HCl results in lung inflammation accompanies by tissue edema and neutrophil accumulation. The deficiency of both L-Pgds and Hpgds genes exacerbates HCl-induced lung dysfunction to a similar extent. In this model, inflamed endothelial/epithelial cells express L-PGDS, while macrophages and neutrophils express H-PGDS. Vascular hyperpermeability in the inflamed lung is accelerated in L-Pgds gene KO mice and is suppressed by DP agonist. Thus, PGD2 is produced locally by L-PGDS in inflamed endothelial and epithelial cells and enhances the endothelial barrier through DP receptors (Horikami et al., 2019).

Lipocalin-Type Prostaglandin D2 Synthase in Cardiovascular Function

L-Pgds gene is the most extensively expressed in the human heart (Eguchi et al., 1997) and L-PGDS plays cardioprotective function in several models. Estrogen induces L-Pgds gene expression in the heart of female mice by stimulating estrogen receptor (ER) β. An estrogen-responsive element in the L-Pgds gene promoter region is activated by ERβ, but not by ERα (Otsuki et al., 2003). Chronic hypoxia (10% O2) upregulates L-Pgds gene expression in the mouse heart. L-PGDS increases in the myocardium of auricles and ventricles and the pulmonary venous myocardium at 28 days of hypoxia. L-Pgds gene expression in the heart is two-fold more higher in heme oxygenase-2 KO mice, a model of chronic hypoxemia, than that of wild-type mice. Hypoxemia increases L-Pgds gene expression in the myocardium to adapt to the hemodynamic stress (Han et al., 2009).

Glucocorticoid stimulation with corticosterone or cortivazol induces calcium-dependent cPLA2, Cox-2 and L-PGDS in neonatal mouse cardiomyocytes. Glucocorticoids upregulate the expression of cPLA2, Ptgs2 and L-Pgds genes and stimulate PGD2 synthesis in adult mouse heart. In isolated Langendorff-perfused mouse hearts, dexamethasone protects ischemia/reperfusion injury. Cox-2 inhibitor or depletion of L-Pgds gene completely suppresses the cardioprotective effect of dexamethasone. Dexamethasone reduces the infarct size by in vivo ischemia/reperfusion experiments of wild-type mice. The cardioprotective effect is markedly reduced in L-Pgds gene KO mice (Tokudome et al., 2009). Dexamethasone upregulates the expression of target genes characteristic erythroid-derived 2–like 2 (Nrf2) in wild-type but not L-Pgds gene-KO mice. Dexamethasone increases Nrf2 expression in an L-PGDS-dependent manner. Nrf2 KO mice do not show L-PGDS-mediated, dexamethasone-induced cardioprotection. Dexamethasone induces FP receptors in the mouse, rat and human heart. Ptgfr gene KO mice do not show the dexamethasone-induced cardioprotection. FP receptors bind PGD2 and PGF2α with almost identical affinities. These results indicate that the dexamethasone-induced cardioprotective effect is mediated by the L-PGDS/PGD2/FP receptors axis through the Nrf2 pathway (Katsumata et al., 2014).

In perfused beating rat atria, hypoxia increases hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) 1α, stimulates atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) secretion, and upregulates Ptgs2 and L-Pgds gene expression. HIF-1α antagonist, 2-methoxyestradiol, downregulates HIF-1α, Ptgs2 and L-Pgds gene expression, and decreases hypoxia-induced ANP secretion. L-PGDS inhibitor AT-56 downregulates L-PGDS protein levels. The hypoxia-induced ANP secretion increases PPARγ protein levels and PPARγ antagonist GW9662 attenuates it. 2-Methoxyestradiol and AT-56 inhibit hypoxia-induced increase in atrial PPARγ protein. Thus, hypoxia activates the HIF-1α-L-PGDS-PPARγ signaling to promote ANP secretion in beating rat atria (Li et al., 2018). In the same model, acute hypoxia stimulates endothelin (ET)-1 release and expression of ETA and ETB receptors. ET-1 upregulates Ptgs2 and L-Pgds gene expression and increases PGD2 production through activation of ETA and ETB receptors. L-PGDS-derived PGD2 promotes hypoxia-induced ANP secretion and in turn regulates L-Pgds gene expression by an Nrf2-mediated feedback mechanism. ET-1 induced by hypoxia activates the Cox-2/L-PGDS/PGD2 signaling and promotes ANP secretion. The positive feedback loop between L-PGDS-derived PGD2 and hypoxia-induced L-Pgds gene expression is a part of the mechanism of hypoxia-induced ANP secretion by ET-1 (Li et al., 2019).

Lipocalin-Type Prostaglandin D2 Synthase in Obesity and Adipocyte Differentiation

A high-fat diet (HFD) upregulates L-Pgds gene expression in adipose tissues and differentiates adipocytes (Fujimori et al., 2007a, 2012b; Chowdhury et al., 2011) so that L-Pgds gene KO mice show several abnormalities in the regulation of energy homeostasis. L-Pgds gene KO mice exhibit glucose-intolerant and insulin-resistant at an accelerated rate as compared with wild-type mice. Adipocytes are larger in L-Pgds gene KO mice than those of control mice with the same diet. L-Pgds gene KO mice develop nephropathy and an aortic thickening reminiscent to the early stages of atherosclerosis when fed HFD (Ragolia et al., 2005). Adipocytes of L-Pgds gene KO mice are less sensitive to insulin-stimulated glucose transport than those of wild-type mice (Ragolia et al., 2008).

L-Pgds gene KO mice exhibit body weight gain more than WT mice when fed HFD, and increase subcutaneous and visceral fat tissues. HFD-fed L-Pgds gene KO mice exhibit increased fat deposition in the aortic wall, atherosclerotic plaque in the aortic root, macrophage cellularity and the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1. Thus, L-Pgds gene deficiency induces obesity and facilitates atherosclerosis through the regulation of inflammatory responses (Tanaka et al., 2008).

L-Pgds gene KO mice display features of the metabolic syndrome in the absence of HFD as well as with HFD feeding and this correlates with hyperactivity of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, i.e., increases in plasma ACTH and corticosterone concentrations, at 20-week-old. C57BL/6 mice exhibit age-related increases in HPA activity, whereas L-Pgds gene KO mice are resistant to changes in HPA activity with age and long-term HFD feeding. Thus, these events depend on L-Pgds gene expression (Evans et al., 2013).

Vertical sleeve gastrectomy (VSG) is used to improve metabolic complications in patients with obese and diabetes. VSG improves glycemic parameters 10 weeks after operation in WT and L-Pgds gene knock-in (KI) mice but not in L-Pgds gene KO mice, as compared with the sham-operated group. L-Pgds gene KO mice develop glucose intolerance and insulin resistance even after VSG similar to or greater than the sham group. L-Pgds gene KO mice exhibit post-VSG peptide YY levels slightly increased but significantly less than other groups and the leptin sensitivity in response to VSG less than KI mice. Total cholesterol level is unchanged in all groups irrespective of sham or VSG surgery. However, L-Pgds gene KO mice show higher cholesterol levels and increase the adipocyte size in post-VSG. Thus, L-PGDS plays an important role in the beneficial metabolic effects by VSG (Kumar et al., 2016).

L-Pgds gene KO mice show hypertension and acceleration of thrombogenesis but Hpgds gene KO mice do not change these functions (Song et al., 2018). Therefore, L-PGDS is also important for the control of blood pressure and thrombosis.

There are two distinct types of adipose-specific L-Pgds gene KO mice: one is fatty acid binding protein 4 (fabp4, aP2)-Cre/L-Pgds flox/flox mice and the other is adiponectin (AdipoQ)-Cre/L-Pgds flox/flox mice. The former strain lacks the L-Pgds gene in adipocytes even in the premature stage and the latter strain, only after maturation. The former strain decreases L-Pgds gene expression and PGD2 production levels in white adipose tissue under HFD conditions, whereas the latter strain does not change the L-PGDS and PGD2 levels. When fed an HFD, the former strain aP2-Cre/L-Pgds flox/flox mice reduce body weight gain, adipocyte size, and serum cholesterol and triglyceride levels. In white adipose tissue of HFD-fed aP2-Cre/L-Pgds flox/flox mice, the expression levels of adipogenic, lipogenic, and M1 macrophage marker genes are decreased, whereas the lipolytic and M2 macrophage marker genes are enhanced or unchanged. Insulin sensitivity is improved in HFD-fed aP2-Cre/L-Pgds flox/flox mice. Therefore, PGD2 produced by L-PGDS in premature adipocytes is involved in the regulation of body weight gain and insulin resistance under nutrient-dense conditions (Fujimori et al., 2019).

In PPARγ-KO mice, L-Pgds gene expression is increased in brown adipose tissue (BAT) and subcutaneous white adipose tissue but reduced in the liver and epididymal fat (Virtue et al., 2012b). Double KO mice of PPARγ and L-Pgds genes exhibit reduced expression of thermogenic genes, the de novo lipogenic program and the lipases in subcutaneous white adipose tissue but elevated expression of lipolysis genes in epididymal fat. These results indicate that PPARγ and L-PGDS coordinate to regulate carbohydrate and lipid metabolism (Virtue et al., 2012b). In BAT, L-Pgds gene expression increases after HFD feeding or cold exposure at 4C (Virtue et al., 2012a). The L-PGDS induction depends on PGC1α and 1β, positive regulators of BAT activation, and is reduced by RIP140, a negative regulator of BAT activation. Under cold–acclimated conditions, L-Pgds gene KO mice exhibit elevated reliance on carbohydrate used for thermogenesis and increase expression of genes regulating glycolysis and de novo lipogenesis in BAT.

In ob/ob mice, L-Pgds gene expression is decreased in white adipose tissue whereas Hpgds gene expression is markedly increased. In white adipose tissue, H-PGDS exists in macrophages and is involved in polarization of macrophages toward to M2, anti-inflammatory, state in both mice and human (Virtue et al., 2015).

Lipocalin-Type Prostaglandin D2 Synthase in Bone and Cartilage Metabolism

In the mouse model of collagen-induced arthritis (CIA), PGD2 is produced in the joint during the early phase. Serum PGD2 levels increase progressively throughout the arthritic process and reach to a maximum during the late stages. The expression of L-Pgds, Hpgds, Ptgdr, and Ptgdr2 genes increases in the articular tissues during arthritic process. DP antagonist MK0524 increases the incidence and severity of CIA, and the local levels of IL-1β, CXCL-1, and PGE2 but reduces the IL-10 levels. CRTH2 antagonist CAY10595 does not modify the severity of arthritis. The administration of PGD2 or a DP agonist BW245C reduces the incidence of CIA, the inflammatory response, and joint damage. In the articular tissue during development of CIA, PGD2 plays an anti-inflammatory role through DP receptors (Maicas et al., 2012). In the spontaneous Hartley guinea pig and experimental dog arthritis models, L-Pgds gene expression also increases over the course of osteoarthritis. In the guinea pig model, L-PGDS levels are correlated positively with the histological score of osteoarthritis (Nebbaki et al., 2013).

In an experimental osteoarthritis model induced by destabilization of the medial meniscus, L-Pgds gene KO mice exhibit exacerbated cartilage degradation and enhanced expression of matrix metalloproteinase 13 (MMP-13) and a disintegrin and metalloprotein-ase with thrombospondin motifs 5 (ADAMTS-5), and display increased synovitis and subchondral bone changes (Najar et al., 2020). Cartilage explants from L-Pgds gene KO mice show enhanced proteoglycan degradation after treatment with IL-1α. Intra-articular injection of AAV2/5 encoding L-Pgds gene attenuates the severity of osteoarthritis in wild-type mice, by an increase in L-PGDS level in the osteoarthritis tissue. L-Pgds gene KO mice show the accelerated development of naturally occurring age-related osteoarthritis (Ouhaddi et al., 2020). L-Pgds gene deletion promotes cartilage degradation during aging and enhances expression of extracellular matrix degrading enzymes, MMP-13 and ADAMTS-5, and their breakdown products. Moreover, L-Pgds gene deletion enhances subchondral bone changes without effect on its angiogenesis, increases mechanical sensitivity, and reduces spontaneous locomotor activity. L-Pgds gene expression increases in aged mice, suggesting that L-PGDS plays an important role to protect against naturally occurring age-related osteoarthritis. L-PGDS may be a new efficient therapeutic target in osteoarthritis.

Lipocalin-Type Prostaglandin D2 Synthase in Keratinocytes and Hair Follicle Neogenesis

In a wound-induced hair follicle neogenesis model, L-PGDS and PGD2 levels of the skin are negatively correlated with the hair follicle neogenesis among C57Bl/6J, FVB/N, and mixed strain mice (Nelson et al., 2013). The hair follicle regeneration increases in mice with an alternatively spliced transcript variant of L-Pgds gene without exon 3 and Ptgdr2 gene KO mice, but not in Ptgdr gene KO mice. Keratinocytes produce L-PGDS in the skin. PGD2 produced by L-PGDS in keratinocytes inhibits wound-induced hair follicle neogenesis through CRTH2 receptors.

Lipocalin-Type Prostaglandin D2 Synthase in Mast Cell Differentiation and Anaphylaxis

Mast cells play important roles in anaphylaxis. Phenotypes of mast cells are changed by microenvironment. Mast cells dominantly express H-PGDS (Urade et al., 1990) and release PGD2 after anti-IgE stimulation. For maturation of bone-marrow derived mast cells in vitro, it is necessary for immature mast cells to interact with fibroblasts, suggesting that fibroblasts release some mediators for maturation of mast cells. The mediator is PGD2 produced by L-PGDS in fibroblasts1. Mast cells secrete phospholipase A2 (PLA2G3), which couples to the Cox/L-PGDS system in fibroblasts to produce PGD2. PGD2 released from fibroblasts then stimulates DP receptors on immature mast cells to promote their maturation (Taketomi et al., 2013).

Lipocalin-Type Prostaglandin D2 Synthase in Colon

In experimental colitis model with dextran sodium sulfate in the drinking water, the disease activity reduces in L-Pgds gene KO mice than WT mice (Hokari et al., 2011). PGD2 derived from L-PGDS plays pro-inflammatory roles in the dextran-induced colitis.

Lipocalin-Type Prostaglandin D2 Synthase in Adenoma

In tumor generation in ApcMin/+ mice mated with various mutations of L-Pgds, Hpgds and Ptgdr genes, adenoma production is enhanced in KO mice of Hpgds or Ptgdr gene but slightly reduced in L-Pgds gene KO mice. ApcMin/+ mice overexpressing human Hpgds or L-Pgds gene suppress the tumor generation (Tippin et al., 2014).

Lipocalin-Type Prostaglandin D2 Synthase in Melanoma

Lipocalin-type prostaglandin D2 synthase is expressed in endothelial cells of human melanoma and oral squamous cell carcinoma (Omori et al., 2018). Human endothelial cells produce L-PGDS and PGD2 after stimulation with IL-1 and TNFα derived from tumor cells. Melanoma growth is accelerated in L-Pgds gene KO mice or endothelial cell-specific L-Pgds gene KO mice and is attenuated by administration of a DP agonist BW245C. L-Pgds gene deficiency in endothelial cells accelerates vascular hyperpermeability, angiogenesis, and endothelial-mesenchymal transition in tumors to reduce tumor cell apoptosis. Tumor cell-derived inflammatory cytokines increase L-Pgds gene expression and PGD2 production in tumor endothelial cells. PGD2 is a negative regulator of the tumorigenic changes in tumor endothelial cells.

Lipocalin-Type Prostaglandin D2 Synthase in Renal Function

In a mouse model of Adriamycin-induced nephropathy, L-PGDS is induced in tubules including proximal, Henle’s loop and distal compartments of the kidney (Tsuchida et al., 2004). Urinary L-PGDS excretion increases from day 1 onward, and apparently precedes the increase in urinary albumin excretions. Neither serum L-PGDS nor creatinine levels are changed by administration of Adriamycin. However, serum creatinine levels are inversely correlated to urinary L-PGDS excretions. The urinary L-PGDS is a useful marker of renal permeability dysfunction.

Otsuka Long-Evans Tokushima Fatty (OLETF) rats develop diabetes associated with hypertension and exhibit higher urinary L-PGDS excretion than non-diabetic Long-Evans Tokushima Otsuka rats (Ogawa et al., 2006). The urinary L-PGDS excretion in OLETF rats increases in an age-dependent manner and is due to increased glomerular permeability to L-PGDS. Renal tissue contains L-PGDS mRNA and immunoreactivity. However, glomerular filtration of L-PGDS contributes to urinary L-PGDS excretion much more than the de novo synthesis. Multiple regression analysis shows that urinary L-PGDS is determined by urinary protein excretions and not by high blood pressure per se. Conversely, the urinary L-PGDS excretion in the early stage of diabetes predicts the urinary proteinuria in the established diabetic nephropathy.

Crude extracts of monkey kidney and human urine contain L-PGDS isoforms with its original N-terminal sequence starting from Ala23 after the signal sequence, and from Gln31 and Phe34 with its N-terminal-truncation (Nagata et al., 2009). The mRNA and the intact form of L-PGDS exist in the cells of Henle’s loop and the glomeruli of the kidney, as examined by in situ hybridization and immunostaining with monoclonal antibody 5C11, which recognizes the amino-terminal loop from Ala23 to Val28 of L-PGDS. Those cells and tissues produce L-PGDS de novo within the kidney. Truncated forms of L-PGDS exist in the lysosomes of tubular cells, as visualized by immunostaining with monoclonal antibody 10A5, which recognizes the 3-turn α-helix between Arg156 and Thr173 of L-PGDS. Therefore, tubular cells uptake L-PGDS and degrade within lysosomes to produce the truncated form.

Lipocalin-type prostaglandin D2 synthase contributes to the progression of renal fibrosis via CRTH2-mediated activation of Th2 lymphocytes (Ito et al., 2012). In a mouse model of renal fibrosis caused by unilateral ureteral obstruction, the tubular epithelium produces L-PGDS de novo. L-Pgds or Ptgdr2 gene KO mice exhibit less renal fibrosis, reduce infiltration of Th2 lymphocytes to the cortex, and decrease production of Th2 cytokines IL-4 and IL-13. Administration of a CRTH2 antagonist Cay10471 at 3 days after the obstruction suppresses the progression of renal fibrosis. IL-4- or IL-13 KO mice also ameliorate the kidney fibrosis in the unilateral obstruction model. Blocking of CRTH2 receptors may be useful to slowdown the progression of renal fibrosis in chronic kidney diseases.

Lipocalin-Type Prostaglandin D2 Synthase in Preterm Birth

LPS-induced preterm birth occurs 89% and 100%, respectively, in C57BL/6 mice and L-Pgds gene-overexpressing TG mice and significantly reduced to 40% in L-Pgds gene KO mice (Kumar et al., 2015). Administration of DP or CRTH2 antagonists to C57BL/6 mice increases the number of viable pups 3.3-fold, indicating that PGD2-mediated inflammation is involved in the preterm birth and the dead birth.

Lipocalin-Type Prostaglandin D2 Synthase in Uterus

Double KO mice of both L-Pgds and Hpgds genes develop adenomyotic lesions in the uterus at 6-month-old (Philibert et al., 2021). The disease severity increases with age, suggesting that the PGD2 signaling has major roles in the uterus by protecting the endometrium against development of adenomyosis.