Abstract

Heterotrimeric G protein Gβ‐deficient mutants in rice and maize display constitutive immune responses, whereas Arabidopsis Gβ mutants show impaired defense, suggesting the existence of functional differences between monocots and dicots. Using CRISPR/Cas9, we produced one hemizygous tomato line with a mutated SlGB1 Gβ gene. Homozygous slgb1 knockout mutants exhibit all the hallmarks of autoimmune mutants, including development of necrotic lesions, constitutive expression of defense‐related genes, and high endogenous levels of salicylic acid (SA) and reactive oxygen species, resulting in early seedling lethality. Virus‐induced silencing of Gβ in cotton reproduced the symptoms observed in tomato mutants, confirming that the autoimmune phenotype is not limited to monocot species but is also shared by dicots. Even though multiple genes involved in SA and ethylene signaling are highly induced by Gβ silencing in tomato and cotton, co‐silencing of SA or ethylene signaling components in cotton failed to suppress the lethal phenotype, whereas co‐silencing of the oxidative burst oxidase RbohD can repress lethality. Despite the autoimmune response observed in slgb1 mutants, we show that SlGB1 is a positive regulator of the pathogen‐associated molecular pattern (PAMP)‐triggered immunity (PTI) response in tomato. We speculate that the phenotypic differences observed between Arabidopsis and tomato/cotton/rice/maize Gβ knockouts do not necessarily reflect divergences in G protein‐mediated defense mechanisms.

1. INTRODUCTION

Heterotrimeric G proteins (G proteins), composed of alpha (Gα), beta (Gβ), and gamma (Gγ) subunits, are signaling molecules that modulate multiple processes in most eukaryotic organisms. Extensive molecular, biochemical, and genetic studies have uncovered the G protein mechanism of action and their signaling pathways in animal systems (Neves et al., 2002; Oldham & Hamm, 2008). Plant G proteins share some similarities with their animal counterparts although they also show important differences (Trusov & Botella, 2016). In the animal‐based paradigm, perception of an agonist by a G protein‐coupled receptor (GPCR) leads to the replacement of GDP by GTP in Gα and activation of signaling by the two functional subunits, Gα and the Gβγ dimer, that ends after the hydrolysis of GTP to GDP by Gα. Plants do not possess GPCRs similar to those found in animal systems and instead mediate signaling from receptor molecules such as RGS1 and defense‐related receptor‐like kinases (RLKs) (Bommert et al., 2013; Chen et al., 2003; Liang et al., 2016). Most importantly, plant G proteins can signal in a nucleotide‐independent manner without the need to bind GTP or GDP (Temple & Jones, 2007; Willard & Siderovski, 2004). Compared with humans, with 23 Gα, six Gβ, and 12 Gγ subunits (McCudden et al., 2005; Wettschureck & Offermanns, 2005), the number of G protein subunits in plants is relatively low. The Arabidopsis thaliana (Arabidopsis, hereafter) genome encodes a single prototypical animal‐like Gα, three noncanonical extra‐large Gα (XLGs) (Ding et al., 2008; Lee & Assmann, 1999; Ma et al., 1990; Maruta et al., 2015), a single Gβ (Weiss et al., 1994), and three Gγ subunits (Chakravorty et al., 2011; Mason & Botella, 2000, 2001; Thung et al., 2012), whereas the tomato genome encodes one canonical Gα (Ma et al., 1991), four XLGs (Solyc08g005310, Solyc08g076160, Solyc03g097980, and Solyc02g09016) (Wu et al., 2018), one Gβ (Solyc01g109560), and four Gγ subunits (Subramaniam et al., 2016). Yet, plant G proteins are involved in the regulation of a diverse range of signaling pathways including cell division and proliferation, stomatal movement, meristem development, hormonal responses, seed germination, and seedling development and defense (Botella, 2012; Pandey, 2019; Trusov & Botella, 2012; Urano et al., 2016; Urano & Jones, 2013; Zhong et al., 2019).

With notable exceptions, the vast majority of G protein functional studies have been performed in Arabidopsis. Loss‐of‐function Gβ (AGB1) mutants in Arabidopsis show altered plant morphology such as short hypocotyls, rounded leaves, increased root mass, shortened floral bubs, short and wide siliques, and shortened overall plant height (Chen et al., 2006; Lease et al., 2001; Ullah et al., 2003). agb1 mutants also exhibit alterations in the response to several plant hormones including auxins, ABA, GA3, BR, and JA (Chen et al., 2004; Trusov et al., 2009; Tsugama et al., 2013; Ullah et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2018). Most importantly, AGB1 plays a significant role in the defense against bacterial, fungal, and viral pathogens (Brenya et al., 2016; Llorente et al., 2005; Maruta et al., 2015; Torres et al., 2013; Trusov et al., 2006, 2007, 2009). In contrast to Arabidopsis, it has been difficult to dissect Gβ functions in monocots such as rice due to the difficulty in silencing Gβ in this species using RNAi technology (Utsunomiya et al., 2011; Utsunomiya et al., 2012). Nonetheless, analyses of rice RNAi‐Gβ knockdown mutants revealed that downregulation of the rice Gβ gene (RGB1) causes phenotypes linked to immune defects such as browning of the lamina joint regions and internodes, ectopic cell death in roots, and elevated expression of several pathogenesis‐related genes (Urano et al., 2019, 2011). CRISPR/Cas9 technology has been recently used to produce Gβ knockout lines in maize and rice (Gao et al., 2019; Wu et al., 2020). Rice and maize Gβ null mutants are seedling lethal as the mutants exhibit developmental arrest and die at a very early seedling stage (Gao et al., 2019; Wu et al., 2020). The rice and maize Gβ mutants exhibit high levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and pathogenesis‐related (PR) gene expression as well as generalized cell death even when grown under sterile conditions, indicating that silencing of Gβ induces a constitutive defense response.

The seedling lethal phenotype of rice and maize Gβ knockout mutants is strikingly different from Arabidopsis, in which agb1 mutants display normal growth and fertility (Gao et al., 2019; Lease et al., 2001; Wu et al., 2020). These observations suggest that the G protein β subunit is essential for plant growth and development in rice and maize, but not in Arabidopsis, and raise questions of whether Gβ protein functions have undergone different evolutionary paths in monocot and dicot species (Choudhury et al., 2011). Because the only stable Gβ null mutations available in dicots have been produced in Arabidopsis, further studies with additional dicot plants are needed to address this hypothesis.

In this study, we used CRISPR/Cas9 to introduce mutations in the tomato Gβ subunit gene (SlGB1) to study the effect of silencing Gβ in a dicot species different from Arabidopsis. We found that knockout of SlGB1 is seedling lethal, with slgb1 mutants showing all the hallmarks of an autoimmune response including spontaneous expression of defense‐related genes, constitutive ROS production, extensive cell death, and elevated SA levels. The observations in stable CRISPR tomato lines were corroborated in cotton, where silencing of Gβ by virus‐induced gene silencing (VIGS) resulted in plant death, development of necrotic lesions, induction of defense‐related genes, and accumulation of ROS and SA. The phenotypes induced by Gβ silencing in tomato and cotton are very similar to those observed in rice and maize, providing proof that the extreme phenotypes observed in these two grasses are not confined to monocots but also extend to dicots and raise questions about whether some G protein functions/signaling have been lost in Arabidopsis during evolution.

2. RESULTS

2.1. Knockout of the heterotrimeric Gβ subunit gene causes seedling lethality in tomato

In order to study the effect of Gβ silencing in a eudicot species different from Arabidopsis, we used CRISPR/Cas9 to introduce mutations in tomato cv. “Moneymaker.” The tomato genome harbors a single Gβ subunit gene, SlGB1 (gene ID: Solyc01g109560.2.1), containing six exons, encoding for a protein with 81% identity to the Arabidopsis AGB1. A CRISPR construct targeting the second SlGB1 exon was designed with the aim to produce mutations early in the coding sequence, thus rendering a nonfunctional protein (Figures 1a and S1a). Agrobacterium‐mediated transformation produced multiple T0 transgenic lines, and the presence of mutations was determined in all lines by PCR amplification of the targeted genomic region followed by sequencing of the amplicons. Sequencing analysis identified one heterozygous line with a single base substitution (wt/s1) and two biallelic mutations with nucleotide deletions (d4/d6 and d3/d13) (Table S1). Unfortunately, only the slgb1_d3d13 line produced progeny, whereas the wt/s1 and d4/d6 failed to produce any fruits. Multiple transformation experiments failed to produce additional T0 plants with mutations; therefore, we proceeded to characterize the slgb1_d3d13 biallelic line. The CRISPR‐induced deletion of three bases resulted in the omission of a threonine amino acid in position 49 of the protein, whereas the deletion of 13 bases produced a frameshift that interrupted the canonical sequence of the protein at position 47 adding an unrelated peptide of 28 amino acids before encountering a translational stop codon (Figure S1a–c). Although the omission of the T49 was not expected to have any effect on the protein function as the amino acid is not conserved among Gβ subunits (Figure S1d), we decided to eliminate the mutation by outcrossing slgb1_d3d13 plants with wild type (WT) and identifying slgb1_d13wt individuals.

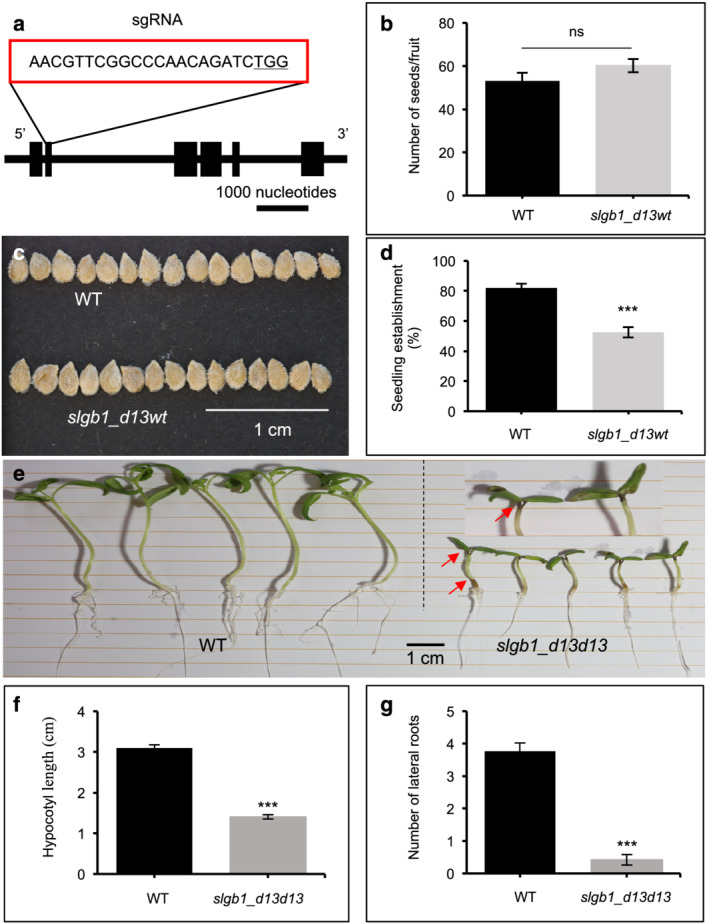

FIGURE 1.

CRISPR‐mediated knockout of Gβ in tomato is seedling lethal. (a) Schematic map of the CRISPR target in the tomato SlGB1 gene. Exons are represented as black boxes, and introns are shown as lines. The position and sequence of the single guide RNA (sgRNA) are shown in a red box with the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequences underlined. (b) Number of seeds from fruits of self‐pollinated wild‐type (WT) and heterozygous slgb1_d13wt mutants plants. Bars represent means ± SEM, n = 78 for WT and n = 90 for slgb1_d13wt samples. “ns” indicates no significant difference (P > .05) by Student's t‐test. (c) Seeds from fruits of self‐pollinated WT and heterozygous slgb1_d13wt mutants. (d) Seedling establishment is reduced in the progeny of heterozygous slgb1_d13wt mutants compared with WT plants. Bars represent averaged values from four replicates of 50 seeds with standard errors. Asterisk indicates statistically significant difference evaluated by Student's t‐test, *** P < .001. (e) Two‐week‐old homozygous slgb1_d13d13 seedlings grown on MS medium developed characteristic brown lesions at the top and the base of hypocotyls that are indicated by red arrows. (f) Hypocotyl length and (g) number of lateral roots of 2‐week‐old WT and homozygous slgb1_d13d13 seedlings grown on MS medium. Bars represent means ± SEM, n ≥ 20. Asterisks indicates significant difference evaluated by Student's t‐test, *** P < .001

Self‐pollination of slgb1_d13wt plants produced fruits with a similar number of seeds than WT controls (Figure 1b). Although seeds from self‐pollinated slgb1_d13wt plants did not show any visible phenotypic differences with WT (Figure 1c), they showed a lower than expected percentage of seed establishment compared with WT seeds when sown in soil (Figure 1d). Analysis of 95 established seedlings failed to identify homozygous slgb1_d13d13 individuals (Table 1), arising suspicions about the possible lethality of the slgb1_d13d13 mutation in tomato. Three potential explanations for the absence of established slgb1_d13d13 mutant seedlings are either (1) gametophyte lethality, (2) embryo lethality, or (3) early seedling lethality. To determine if the d13 mutation affected gametophyte viability, we performed reciprocal crosses between WT and slgb1_d3d13 lines followed by sequencing of the F1 progeny. When the slgb1_d3d13 line was used as pollen donor, we identified both heterozygous phenotypes including slgb1_d3wt and slgb1_d13wt in the F1 progeny (Table 2). Similarly, when we used slgb1_d3d13 line as pollen acceptor from WT plants, we found both slgb1_d3wt and slgb1_d13wt genotypes in the F1 progeny (Table 2). These results indicated that slgb1_d3 and slgb1_d13 pollen grains and ovules were viable. Additional analysis of pollen from self‐pollinated WT and biallelic slgb1_d3d13 plants showed a small reduction in the germination rates in pollen from slgb1_d3d13 plants but not the expected 50% reduction caused by a lethal allele, and no differences were observed in pollen tube growth (Figure S2).

TABLE 1.

Segregation of slgb1 alleles

| Self‐pollination of heterozygous slgb1_ d13wt, n = 95 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Genotype | Expected | Observed |

| Homozygous, slgb1_d13d13 | 23.75 (25%) | 0 |

| Heterozygous, slgb1_d13wt | 47.5 (50%) | 55 (61.1%) |

| Wild type | 23.75 (25%) | 40 (39.9%) |

| χ2 = 36.053***, P < .001 | ||

Notes: The analysis was performed by χ2 test against the H0 hypothesis that segregation follows Mendel's law. Asterisks indicate significant difference from the expected Mendelian segregation ratio.

TABLE 2.

Reciprocal crosses of slgb1_d3d13 with wild type plants

| Crosses | F1 genotypes, n = 12 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Heterozygous slgb1_d3wt | Heterozygous slgb1_d13wt |

| slgb1_d3d13 | Wild type | 7 | 5 |

| Wild type | slgb1_d3d13 | 4 | 8 |

We next studied whether the slgb1_d13d13 genotype was embryo lethal by sowing seeds from self‐pollinated slgb1_d13wt individuals in soil and determining the genotypes of individual seedlings soon after sowing, including non‐germinated seeds, seeds showing only protrusion of the radicle and seedlings in the very early stages of development. Sequence analysis showed the presence of slgb1_d13d13 homozygous plants at different stages after germination, from seeds with barely protruding radicles to germinated seedlings of approximately 10 mm in size (Figure S3a). We therefore deduced that the absence of fully established slgb1_d13d13 seedlings was due to early seedling lethality rather than embryo lethality.

To further analyze the cause of the seedling lethality observed in homozygous SlGB1 knockout plants, we germinated seeds from self‐pollinated heterozygous slgb1_d13wt plants on sterile Murashige–Skoog (MS) medium. All seedlings were genotyped by sequencing, and a Mendelian segregation ratio of 1:2:1 was observed. Homozygous slgb1_d13d13 seedlings were smaller than WT seedlings and had a distinct brown coloration at the top of the hypocotyl appearing approximately 8–10 d after germination (DAG), which progressively extended throughout the seedling into the cotyledons, hypocotyl, and roots (Figures 1e and S3b). slgb1_d13d13 seedlings had short hypocotyls and substantially reduced number of lateral roots compared with WT (Figure 1e,f,g). Additionally, whereas WT seedlings developed true leaves 10–15 DAG, slgb1_d13d13 mutants never developed true leaves even though some seedlings survived for 40 DAG (Figure S3b), indicating the possible existence of defects in the apical meristem as has been described in maize and rice (Gao et al., 2019; He et al., 2007; Wu et al., 2020). The typical phenotype observed in tissue culture grown homozygous slgb1_d13d13 mutants simplified the visual identification of homozygous individuals for subsequent experiments, although genotyping was always performed for all experiments.

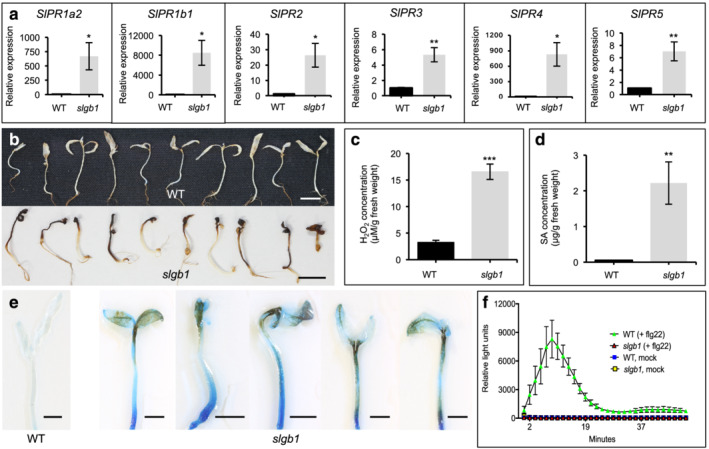

2.2. SlGB1 is a positive regulator of the PAMP (pathogen‐associated molecular pattern)‐triggered immunity (PTI) response in tomato but silencing of SlGB1 results in constitutive activation of defense responses

The observed phenotype of slgb1_d13d13 mutants was clearly reminiscent of several reported autoimmune mutants and resembled the symptoms described in maize and rice Gβ knockout mutants (Gao et al., 2009, 2019; He et al., 2007; Mackey et al., 2002; Wu et al., 2020). Therefore, we determined the expression levels of a number of defense‐related genes, including the SA‐dependent PR1b1, PR1a2, PR2, and PR5, as well as the jasmonic acid (JA)/ethylene (ET)‐dependent PR3 and PR4. High transcript levels were observed for all six PR genes in slgb1_d13d13 plants compared with control WT plants under non‐inducing conditions (Figure 2a). In addition, homozygous slgb1_d13d13 seedlings showed intense staining DAB, indicating the presence of high levels of ROS (Figure 2b). Quantification of endogenous H2O2 revealed that slgb1_d13d13 seedlings contained fivefold higher H2O2 levels than WT, confirming the DAB staining results (Figure 2c). As observed in several autoimmune mutants (Sun et al., 2015; van Wersch et al., 2016), slgb1_d13d13 mutants also accumulated high levels of endogenous SA with a 32‐fold increase compared with WT seedlings (Figure 2d). To test whether slgb1_d13d13 seedlings exhibit spontaneous cell death in the absence of pathogen infection, 2‐week‐old seedlings grown on sterile MS medium were stained with trypan blue, resulting in extensive blue staining indicating widespread cell death (Figure 2e). In contrast to the tomato slgb1_d13d13 mutants, Arabidopsis agb1 mutants do not show a constitutive immune response, but they are impaired in the ROS response to several PAMPs such as flg22, efl18, and chitin (Ishikawa, 2009; Jiang et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2013). In order to establish whether the tomato SlGB1 subunit is also required for the PAMP triggered ROS burst, we incubated cotyledons from WT and slgb1_d13d13 mutants with 30 nmol flg22. Interestingly, slgb1_d13d13 mutants were impaired in the ROS response to flg22 (Figure 2f), suggesting that SlGB1 is a positive regulator of the PTI response in tomato, similar to Arabidopsis.

FIGURE 2.

Silencing of Gβ in tomato induces constitutive activation of defense responses. These experiments were performed using 2‐week‐old wild‐type (WT) and homozygous slgb1_d13d13 seedlings grown on MS medium. The homozygous slgb1_d13d13 is abbreviated as slgb1 in the figure. (a) Transcript levels of pathogenesis‐related (SlPR) genes in WT and slgb1_d13d13 seedlings were quantified by qRT‐PCR. Gene expression was normalized to the tomato Ubiquitin 3 (SlUB3). (b) DAB staining for H2O2 accumulation in WT and slgb1_d13d13 seedlings. (c) Endogenous H2O2 and (d) salicylic acid (SA) levels in WT and slgb1_d13d13 seedlings. For (a), (c), and (d), bars represent means ± SEM, n = (a) 4, (c) 5, and (d) 7. Asterisks indicates significant difference evaluated by Student's t‐test, *P < .05, **P < .01, *** P < .001. (e) Trypan blue staining for the detection of cell death in WT and slgb1_d13d13 seedlings. For (b) and (e), bars = 1 cm. (f) ROS production induced by 30 nM flg22 on half‐cotyledons of WT and slgb1_d13d13 seedlings. Bars represent means ± SEM, n = 12. The experiment was repeated three times with similar results

2.3. Silencing of Gβ subunit genes in cotton causes activation of the immune response and consequent lethality

The results obtained in tomato Gβ knockout mutants were very similar to those reported in rice and maize (Gao et al., 2019; Wu et al., 2020), providing a strong indication that the phenotypes observed in these two grasses are not confined to monocot species. Tomato is a member of the asterid clade and relatively distant from Arabidopsis, who belongs to the rosid clade, prompting us to study a closer relative such as cotton (Gossypium spp.), which is an important crop for the food and fiber industries worldwide. Although cotton stable transformation is difficult and time consuming (Jin et al., 2006), VIGS in cotton is highly efficient and fast and produces reproducible and consistent phenotypes, providing a convenient tool for functional genomic studies (Gao et al., 2013).

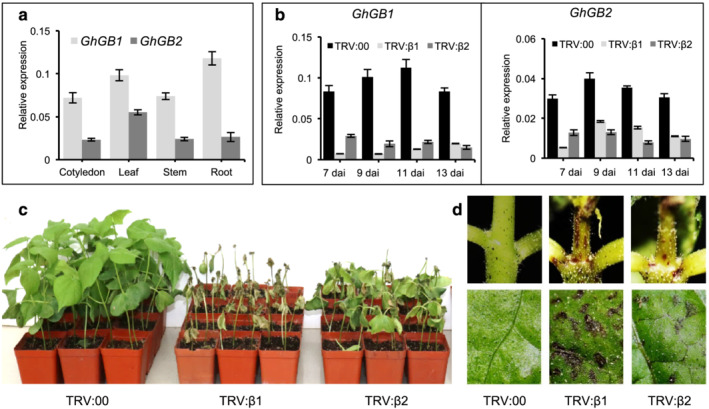

Upland cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) cultivars are allotetraploids (AADD genome). The genome of the “TM1” variety used in this study contains four Gβ subunit genes, namely, Ghir_A03G194000, Ghir_A13G0034700, Ghir_D02G215100, and Ghir_D13G033100, that can be grouped into two homeologous pairs. The coding regions for the homeologous genes located in chromosomes A03 and D02 are virtually identical (98% identity), named GhGB1 herewith, and this is also the case for the homeologs located in chromosomes A13 and D13 (98% identity), named GhGB2 herewith. Interestingly, one of the two GhGB2 homeologous genes, Ghir_D13G033100, contains a small deletion extending from intron #3 to exon #4 that results in the removal of the correct splicing site and the production of an aberrant mRNA coding for approximately half of the Gβ subunit protein before encountering a frameshift and an early stop codon (Figure S4a). The GhGB1 and GhGB2 coding regions share 87% nucleotide identity, whereas the GhGB1 and GhGB2 proteins are 93% identical. Expression analyses showed that both genes are expressed in all assayed tissues in the upland cotton “TM1” variety although GhGB1 transcript levels were consistently higher than GhGB2 (Figure 3a). In order to simultaneously silence both GhGB genes, we performed VIGS experiments using the tobacco rattle virus (TRV) system (Gao et al., 2013). Two different TRV constructs were prepared containing approximately 500 nt fragments (TRV:β1 and TRV:β2) (Figure S4b). Inoculation of “TM1” seedlings with either TRV:β1 or TRV:β2 resulted in silencing of both GhGB genes, with no statistically significant differences observed 13 days after infection (dai) (Figure 3b). Silencing of GhGB genes induced the development of necrotic regions in leaves and stems and culminated in plant death 20–25 dai (Figures 3c,d and S5a). In contrast, control plants inoculated with an empty TRV vector (TRV:00) showed normal development (Figures 3c,d and S5a). TRV:β1 reliably showed faster and stronger lesion development than TRV:β2, consistent with the observed silencing efficiency, and was used for all subsequent experiments. The effects of Gβ silencing were not restricted to a single cotton variety, with similar phenotypes observed in the “Coker201” upland variety as well as in the sea‐island cotton “Hai7124” variety (Figure S5b,c).

FIGURE 3.

Silencing of GhGB1 and GhGB2 in cotton seedlings triggers the appearance of necrotic lesions followed by plant death. (a) Transcript levels of GhGB1 and GhGB2 in different tissues of 3‐week‐old Gossypium hirsutum cv. “TM1” were quantified by qRT‐PCR. (b) qRT‐PCR analysis of GhGB1 and GhGB2 in empty vector control (TRV:00), GhGB1‐silenced (TRV:β1), or GhGB2‐silenced (TRV:β2) cotton plants. One‐week‐old cotton seedlings were infiltrated with Agrobacterium carrying virus‐induced gene silencing (VIGS) vector, TRV:00, TRV:β1 or TRV:β2. qRT‐PCR was performed at 7, 9, 11, and 13 days after infiltration (dai). For (a) and (b), gene expression was normalized to the cotton Ubiquitin 7 (GhUB7). Bars represent means ± SEM, n = (a) 4 and (b) 5. (c) Phenotypes of cotton plants 3 weeks after VIGS infiltration. (d) Representative stem (upper row) and leave (lower row) phenotypes of plants infiltrated with VIGS vector. Photos were taken at 13 dai

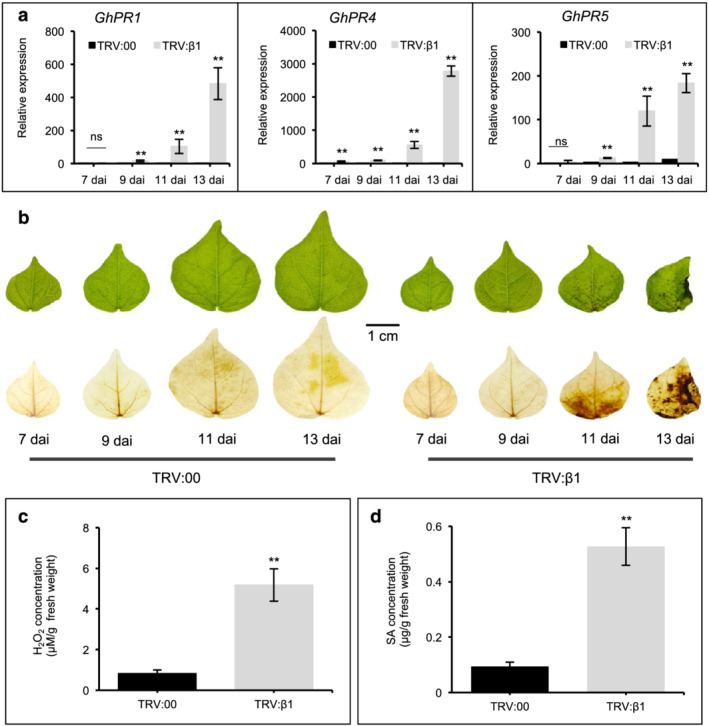

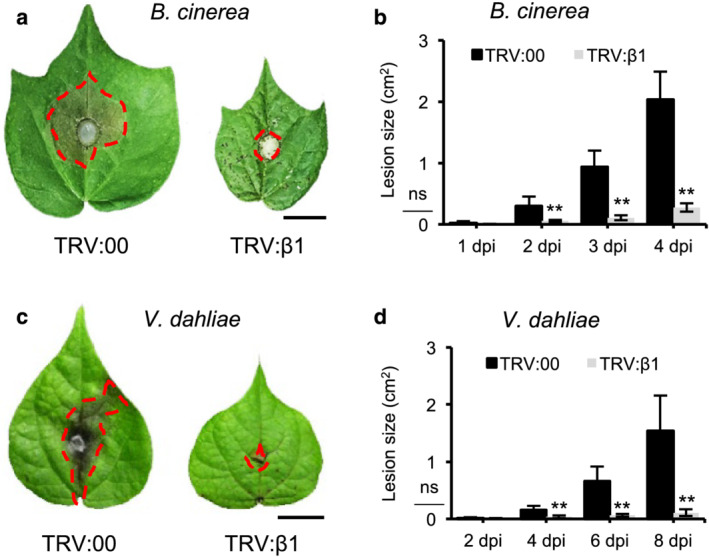

Similar to the observations in the tomato slgb1_d13d13 mutant line, silencing of Gβ in cotton showed all the hallmarks of an autoimmune response. Transcript levels of PR genes, including PR1, PR4, and PR5, were significantly induced 9 dai with TRV:β1 and continued to increase further 11 and 13 dai, whereas inoculation with empty vector (TRV:00) only produced very minor induction (Figure 4a). Onset of necrosis was visible 9–11 dai and increased in severity, progressively correlating with the observed increase in PR gene expression (Figure 4b). DAB staining revealed ROS accumulation appearing 9–11 dai (Figure 4b), whereas quantitative analysis showed that TRV:β1 silenced leaf tissues contained almost seven times higher endogenous H2O2 levels than control TRV:00 inoculated tissues (Figure 4c). Finally, GhGB silencing induced accumulation of the defense hormone SA with leaves of TRV:β1 inoculated plants containing almost six times higher levels of endogenous SA levels than control leaves (Figure 4d). Even though constitutive activation of the defense response reduces plant viability (Gao et al., 2009; He et al., 2007; Riehs‐Kearnan et al., 2012), autoimmune mutants typically show increased resistance to pathogens (Li et al., 2001; Zhang et al., 2003, 2007). We observed that GhGB silencing inhibited the spread of the fungal pathogens Botrytis cinerea and Verticillium dahliae in inoculated leaves (Figure 5).

FIGURE 4.

Silencing of GhGB1 and GhGB2 in cotton induces expression of defense‐related genes and accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and salicylic acid (SA). (a) Transcript levels of three pathogenesis‐related (GhPR) genes, GhPR1, GhPR4, and GhPR5, in leaves of empty vector control (TRV:00) and GhGB1‐silenced (TRV:β1) cotton plants. One‐week‐old Gossypium hirsutum cv. “TM1” were infiltrated with Agrobacterium carrying virus‐induced gene silencing (VIGS) vector, TRV:00, or TRV:β1. qRT‐PCR was performed at 7, 9, 11, and 13 days after infiltration (dai). Gene expression was normalized to the cotton Ubiquitin 7 (GhUB7). (b) Representative leaves of plants infiltrated with VIGS vectors at 7, 9, 11, and 13 dai before (upper row) and after (lower row) DAB staining. (c) Endogenous H2O2 and (d) SA levels in leaves of TRV:00 and TRV:β1 plants at 13 dai. For (a), (c), and (d), bars represent means ± SEM, n = 5. Asterisks indicates significant difference evaluated by Student's t‐test, **P < .01. “ns” indicates no significant difference

FIGURE 5.

Silencing of Gβ in cotton inhibits pathogen growth. (a,c) Disease symptoms induced on leaves of empty vector control (TRV:00) and GhGB1‐silenced (TRV:β1) cotton plants after inoculation with (a) Botrytis cinerea and (c) Verticillium dahlia. One‐week‐old Gossypium hirsutum cv. “TM1” seedlings were infiltrated with Agrobacterium carrying virus‐induced gene silencing (VIGS) vector, TRV:00, or TRV:β1. 13–18 days after VIGS infiltration, detached leaves of infiltrated plants were subjected to B. cinerea and V. dahliae infection. Photos were taken at (a) 4 days post inoculation (dpi) and (c) 7 dpi. The red dashed area indicates the lesion caused by fungal infection. Bars = 1 cm. (b,d) Development of lesion area in the leaves of TRV:00 or TRV:β1 plants infected with (b) B. cinerea and (d) V. dahlia at the indicated time points post‐inoculation. Bars represent means ± SEM, n = 8. Asterisks indicates significant difference evaluated by Student's t‐test, **P < .01. “ns” indicates no significant difference

To gain a more comprehensive view of the gene expression changes induced by the silencing of GhGB, we performed transcriptome analysis in the leaves of plants inoculated with either TRV:β1 or TRV:00 at three different times, namely, 9, 11, and 13 dai. At each time point, RNA‐seq analysis was performed to compare TRV:00‐ with TRV:β1‐inoculated plants. A total of 13,500 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified with 1587 shared among all three time points (Figure S6a and Table S2). A vast majority of the 1587 DEGs (84.3%, 1,338 genes) were upregulated, whereas 249 genes (15.7%) were downregulated (Figure S6b and Table S2). To investigate the putative molecular functions of the DEGs, GO enrichment analysis was conducted at each sampled time comparing TRV:00‐ with TRV:β1‐inoculated plants. Notably, the Top 3 enrichment categories at all three time points were related to plant defense, including response to bacterial attack, response to fungal attack, response to chitin, response to SA, and defense‐related respiratory burst (Figure S6c). Overall, the transcriptome results show that silencing of GhGB1/2 induces expression of genes involved in multiple defense pathways including 17 wall‐associated RLKs, 24 leucine‐rich repeat receptor‐like kinases (LRR RLKs), and other RLKs with homology to previously characterized defense receptors. Pathogenesis‐related and basal immunity proteins are also overrepresented in the induced gene set with 12 chitinases, seven flavin‐dependent monooxygenases, 17 glutathione S‐transferases, thaumatins, lipid transfer proteins, berberine bridge‐like enzymes and 48 WRKY transcription factors, many of which showing homology to previously characterized defense‐related factors including WRKY3/4/7/11/17/18/61/70 and 72 (Figure S6d and Table S3). There was not such a clear trend among the downregulated DEGs although a number of development related genes were identified, including YUCCA and expansin, ABC transporter homologs, and auxin‐related genes (Table S4).

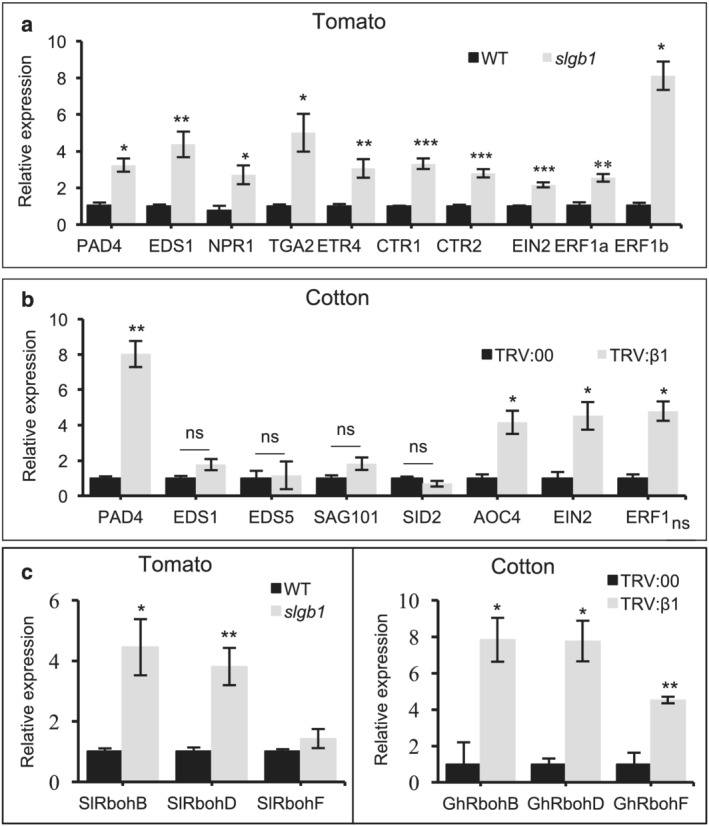

2.4. Silencing of Gβ subunits in tomato and cotton plants induce SA and ET pathway genes

The phytohormones SA, JA, and ET play essential roles in the defense against pathogens (Shigenaga & Argueso, 2016). In an attempt to identify the hormonal pathways involved in the Gβ silencing phenotype in tomato and cotton, we analyzed the expression of a number of genes involved in hormonal biosynthesis and signaling pathways. Expression levels of key genes involved in SA signaling such as Enhanced Disease Susceptibility 1 (EDS1) and its co‐regulator Phytoalexin Deficient 4 (PAD4), Nonexpressor of PR genes1 (NPR1), and TGA2 (Cui et al., 2017) were significantly increased in the tomato slgb1_d13d13 mutants compared with WT seedlings (Figure 6a). Ethylene signaling‐related genes including an ET receptor (SlETR4, a homolog of Arabidopsis ETR1) and downstream signaling components (CTR1, CTR2, EIN2, ERF1a, and ERF1b) were also highly expressed in the slgb1_d13d13 mutants (Figure 6a). Whereas some genes involved in JA biosynthesis such as LOXD and OPR3 showed enhanced levels of expression in the slgb1_d13d13 mutants, others such as AOS and AOC were expressed at WT levels (Figure S7a). Similarly, enhanced levels of expression were detected on some JA signaling components (JAR1) but not others (COI1) (Figure S7a). Two GH3 auxin‐responsive genes were constitutively expressed at high levels in the slgb1_d13d13 seedlings, whereas other auxin‐responsive genes from the IAA and SAUR families were expressed at WT levels (Figure S7b). In agreement with the results in tomato, VIGS‐mediated silencing of GhGB1 in cotton also induced expression of some SA (PAD4) and ET (EIN2, ERF1) signaling pathway genes (Figure 6b).

FIGURE 6.

Salicylic acid, ethylene pathway, and respiratory burst oxidase genes are induced in Gβ‐silenced plants. qRT‐PCR was performed to measure relative expression levels of target genes in (a,c) 2‐week‐old wild type (WT) and homozygous slgb1_d13d13 (abbreviated as slgb1 in the figure) seedlings grown on MS medium and (b,c) leaves of cotton plants 13 days after infiltration (dai) with Agrobacterium carrying virus‐induced gene silencing (VIGS) vector, TRV:00 or TRV:β1. Gene expression was normalized to the tomato Ubiquitin 3 (SlUB3) and cotton Ubiquitin 7 (GhUB7). Bars represent means ± SEM, n ≥ 3. Asterisks indicates significant difference evaluated by Student's t‐test, *P < .05, **P < .01, *** P < .001. “ns” indicates no significant difference

Analysis of respiratory burst oxidase homolog (Rboh) genes that encode ROS‐generating enzymes involved in defense showed strong upregulation of SlRbohB and SlRbohD in tomato slgb1_d13d13 mutant seedlings compared with WT (Figure 6c), whereas analysis of seven genes involved in ROS scavenging and ROS detoxifying in tomato showed only two of them induced in slgb1_d13d13 mutant seedlings (Figure S7c). VIGS‐mediated silencing of Gβ in cotton also resulted in strong upregulation of GhRbohB, GhRbohD, and GhRbohF transcript levels (Figure 6c).

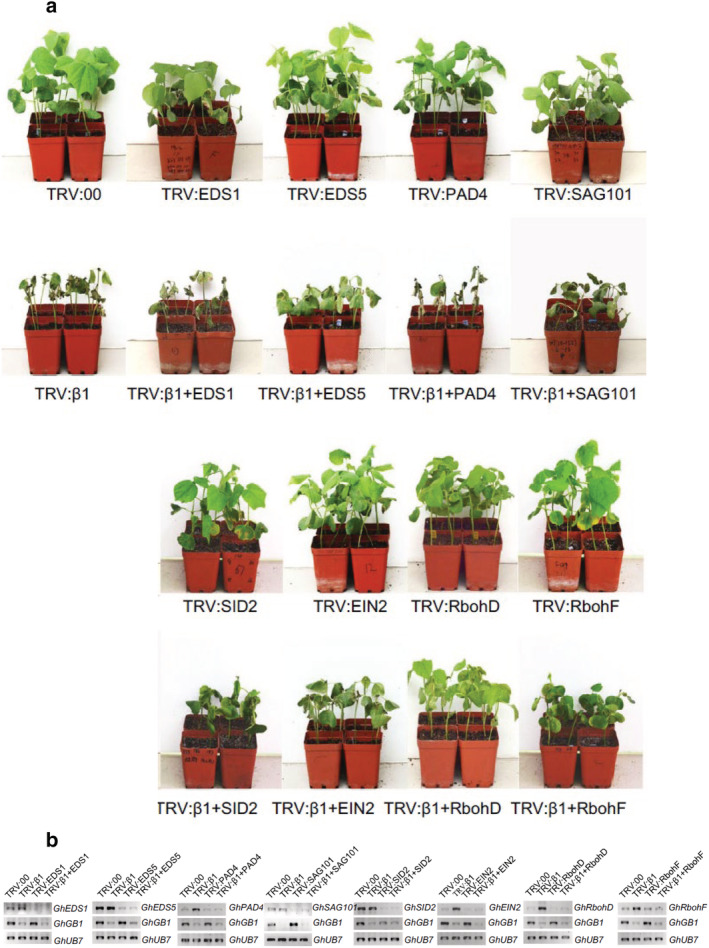

2.5. Lethality caused by Gβ silencing in cotton can be suppressed by silencing of the respiratory burst oxidase RbohD

Aside from silencing individual genes, the VIGS system can be used to silence multiple genes by co‐inoculation with two or more vectors simultaneously, although silencing efficiency can diminish (Wu et al., 2021). Taking advantage of this capability, we performed double silencing experiments in an attempt to suppress the lethal phenotype caused by Gβ silencing in cotton. The silencing efficiency for each of the targeted genes in all experiments was monitored by qRT‐PCR (Figure 7).

FIGURE 7.

The Gβ silencing induced lethal phenotype in cotton is dependent on RbohD. (a) Representative photos of empty control vector (TRV:00), GhGB1‐silenced (TRV:β1), target gene‐silenced (TRV/target), and GhGB1 + target gene‐co‐silenced (TRV:β1 + target) cotton plants. One‐week‐old Gossypium hirsutum cv. “TM1” seedlings were infiltrated with Agrobacterium carrying virus‐induced gene silencing (VIGS) vector to initiate the silencing of single‐ or double‐target genes. Photos were taken at 17 days after infiltration (dai). (b) qRT‐PCR analysis of the expression pattern of GhGB1 and target genes in VIGS‐infiltrated plants was performed at 11 dai. The cotton Ubiquitin 7 (GhUB7) was used as reference gene

Silencing of Gβ in tomato produced constitutive high levels of defense‐related genes in the slgb1_d13d13 mutants, especially genes related to SA and ET signaling, many of which were confirmed as being strongly induced upon silencing of GhGB1/2 in cotton (Figures 2, 4, 6, and S6). In addition, Gβ silencing in tomato and cotton resulted in strong ROS staining and high levels of endogenous H2O2 and SA (Figures 2 and 4). We therefore focused our attention on these two important defense‐related hormones as well as the respiratory burst oxidases. Surprisingly, silencing of several essential SA‐mediated defense signaling components such as PAD4, EDS1, SAG101, EDS5, and SID2 in cotton did not stop the lethality caused by Gβ silencing (Figure 7). Silencing of EIN2 also failed to suppress the lethality caused by Gβ silencing, even though very efficient downregulation was achieved in the co‐silenced plants (Figure 7). Incidentally, when seeds from self‐pollinated heterozygous tomato plants (slgb1_d13wt) were germinated and grown in media supplemented with inhibitors of ET biosynthesis (aminooxyacetic acid [AOA]) and signaling (AgNO3) (Beyer, 1976; Bradford et al., 1982), plants showed typical ET‐associated symptoms, but the lethal phenotype was not suppressed or delayed in slgb1_d13d13 homozygous seedlings (results not shown). Silencing of RbohF in cotton plants resulted in a slight delay in the appearance of symptoms but did not avoid lethality. Finally, we observed that silencing of RbohD suppressed some of the phenotypes caused by silencing of Gβ in cotton with a total absence of necrotic lesions and inhibition of lethality, although the growth of plants co‐inoculated with TRV:β1 and TRV:RbohD was very slow compared with TRV:00‐inoculated controls.

3. DISCUSSION

G protein β subunits are highly conserved within plant species with rice, maize, and Arabidopsis proteins sharing 87% homology, suggesting that they have evolutionarily conserved functions, and this hypothesis is supported by the fact that the maize Gβ can successfully rescue the Arabidopsis agb1 mutant immune phenotypes (Wu et al., 2020). However, Gβ knockout mutants in rice and maize display autoimmunity, a substantial phenotypic difference with Arabidopsis agb1 mutants, suggesting that functional divergences occurred at the monocot/dicot split during the evolution of flowering plants (Gao et al., 2019; Wu et al., 2020). Typical phenotypes of autoimmune mutants include extreme dwarfism and/or seedling lethality, constitutive expression of PR genes, high levels of SA and ROS, increased pathogen resistance, and, in many cases, extended cell death (Bi et al., 2011; Gao et al., 2009; Kemmerling et al., 2007; Li et al., 2001; Shirano et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2012). All these autoimmune phenotypes were observed in our Gβ silencing experiments with tomato and cotton, which together with the autoimmune phenotypes previously described in rice and maize debunk the hypothesis that G proteins underwent functional divergence between monocots and dicots and suggest that Arabidopsis is an exemption rather than the rule.

G proteins have been firmly established as important positive regulators of the PTI defense response acting downstream of RLKs, although most of the available evidence has been gathered in Arabidopsis (Zhong et al., 2019). Although the constitutive immune response caused by Gβ silencing in tomato, cotton, rice, and maize might suggest that Gβ is a negative regulator of defense in these species, instead of a positive regulator as proven in Arabidopsis, we provide proof that the tomato SlGB1 is indeed a positive regulator of the PTI response and essential for the flg22‐triggered oxidative burst (Figure 2f); therefore, alternative scenarios need to be considered.

Important elements of the PTI signaling response are frequently targeted by bacterial virulence factors to facilitate infection, and in some cases, these elements are guarded by nucleotide‐binding domain leucine‐rich repeat (NB‐LRR) proteins (Dodds & Rathjen, 2010). As an important component of the PTI response, Gβ is a good potential target for pathogen effectors either by inducing degradation of the protein or by interfering with its defense‐related activity. It is therefore tempting to hypothesize that Gβ subunits in plants other than Arabidopsis could be guarded by one or more NB‐LRR proteins and that any disruption in protein levels and/or signaling activity could trigger a generalized ETI response explaining the observed phenotypes. Interestingly, mutations in components of the MEKK1‐MKK1/MKK2‐MPK4 cascade produce constitutive autoimmune responses very similar to those observed in tomato and cotton Gβ mutants and were mistakenly considered negative regulators of the defense response until the discovery of SUMM2 established that they are in fact positive regulators of the PTI response (Zhang et al., 2012).

NB‐LRR proteins are generally classified into two classes depending on the nature of their N‐terminal domains, with TIR‐NB‐LRRs containing a Toll‐like/interleukin 1‐like receptor (TIR) and CC‐NB‐LRRs containing a coiled‐coil (CC) domain. The ETI response triggered by all known TIR‐NB‐LRRs and some CC‐NB‐LRRs is mediated by the lipase‐like protein EDS1, which forms heterodimers with either PAD4 or SAG101 (Feys et al., 2001, 2005; Gao et al., 2009; Wagner et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2003). Our data show that tomato slgb1_d13d13 mutants display high PAD4 and EDS1 transcript levels, which could result in activation of the immune response as it has been proven that combined overexpression of PAD4 and EDS1 causes autoimmunity in Arabidopsis (Cui et al., 2017). On the other hand, silencing of GhGB genes in cotton induces PAD4 expression but not EDS1 or SAG101, and we show that silencing of the EDS1, PAD4, and SAG101 homologs in cotton does not prevent the autoimmune phenotypes caused by Gβ silencing, suggesting that the high PAD4 levels are not the cause of the constitutive defense response and that lethality is not caused by an ETI response triggered by TIR‐NB‐LRR receptors at least in cotton. Interestingly, our RNAseq data show that silencing of GhGB genes in cotton induces the expression of several CC‐NB‐LRRs including homologs of the Arabidopsis RPM1 and RPS2 resistance genes as well as several NDR1/HIN‐like genes (Table S3), hinting that the autoimmune phenotype observed in tomato and cotton could be an ETI response mediated by one or several CC‐NB‐LRR proteins.

Although the NB‐LRR guardee model can explain the observed phenotypes, there are other possible scenarios to consider. For example, alterations in Gβ levels could induce an autoimmune response by either repression of negative defense regulators or derepression of positive regulators. In fact, mutations in PTI components can cause autoimmune phenotypes not necessarily associated with the ETI response. Such is the case of BAK1, an essential PTI component and its homolog BAK1‐like1 (BKK1). Whereas the single bak1 and bkk1 mutants do not show obvious defense phenotypes, the double bak1bkk1 mutant shows a strong autoimmune response (He et al., 2007). In another example, mutations in CONSTITUTIVE EXPRESSER OF PR GENES 1 (CPR1) and SUPPRESSOR OF RPS4‐RLD 1 (SRFR1) produce a constitutive immune response caused by increased cellular levels of SUPPRESSOR OF NPR1‐1 CONSTITUTIVE 1 (SNC1), a TIR‐NB‐LRR (Cheng et al., 2011; Gou et al., 2012).

The question remains about the reasons for the profound differences observed between Gβ mutants in Arabidopsis and other species, including monocots such as rice and maize and eudicots such as tomato and cotton. It is highly unlikely that the cause is due to fundamental differences in defense mechanisms because most of the knowledge about plant immunity gained from Arabidopsis is widely applicable to other species. Interestingly, a notable exception seems to be associated with the roles of PAD4, EDS1, and SAG101. In Arabidopsis, EDS1/PAD4 heterodimers are essential for basal immunity and signaling downstream of TIR‐NB‐LRRs, with EDS1/SAG101 dimers having only a marginal role (Cui et al., 2017; Feys et al., 2001, 2005; Rietz et al., 2011). In contrast, in the solanaceous Nicotiana benthamiana, EDS1 mutants are not impaired in basal resistance; and signaling from TIR‐NB‐LRRs requires EDS1/SAG101 dimers but not EDS1/PAD4, with PAD4 not having any detectable immune functions (Gantner et al., 2019). The authors proposed that SAG101 might be required for TIR‐NB‐LRR‐mediated immune signaling in most plants, with the exception of the Brassicaceae. With respect to Gβ mutants, Arabidopsis also seems to be the exception to the norm; therefore, it is tempting to hypothesize that the lack of autoimmunity in Arabidopsis Gβ mutants is due to punctual differences that might have arisen late in evolution, and it will be interesting to find out whether it extends to other members of the Brassicaceae family.

The early seedling lethality caused by Gβ knockouts in rice, maize, and tomato makes it quite difficult to perform in‐depth studies of the underlying mechanisms. However, VIGS‐induced silencing in cotton provides an important resource to study the effects of Gβ silencing in established plants as the development of symptoms can be analyzed from the developmental point at which the silencing is artificially induced. Cotton plants start to show chlorosis and cell death immediately following the silencing of Gβ, demonstrating a causal relationship between reduced Gβ levels and symptom development. The co‐silencing experiments simultaneously targeting Gβ and important components of the SA and ET responses failed to suppress lethality, suggesting either independent or redundant signaling pathways but confirmed the importance of oxidative burst oxidases in the development of symptoms and lethality.

The functional differences between Arabidopsis Gβ and other eudicot and monocot species are not restricted to the defense response. Maize Gβ (ZmGB1) is involved in the control of meristem size in conjunction with the canonical Gα subunit, known as CT2, and zmgb1 knockout mutants are defective in meristem development (Bommert et al., 2013; Wu et al., 2020). We show that tomato slgb1_d13d13 seedlings fail to develop a main stem, suggesting that their meristem is also impaired. Interestingly, the Gβ‐mediated signaling pathways responsible for the defense and developmental phenotypes seem to be different because a maize Gβ allele has been described with weak autoimmune phenotypes, but strong developmental defects (Wu et al., 2020). The corollary to these observations is that Arabidopsis is probably missing several G protein‐dependent signaling pathways.

In summary, our work shows that the autoimmunity displayed by Gβ mutants in maize and rice is not limited to monocotyledonous species, but it also extends to eudicots, except for Arabidopsis and possibly other Brassicaceae. The autoimmune phenotype is independent of essential components of the ETI response mediated by TIR‐NB‐LRRs such as EDS1, PAD4, and SAG101, but is dependent on the oxidative burst oxidase RbohD. Nevertheless, and despite the apparently opposite phenotypes between Arabidopsis and tomato, cotton, rice, and maize, we believe that the G protein‐mediated defense mechanisms established in Arabidopsis are conserved in other plant species, as suggested by the deficient PAMP response shown by the slgb1_d13d13 mutants. Our results enhance rather than diminish the value of Arabidopsis mutants to study defense‐related roles for G proteins because the lack of lethality allows to perform comprehensive experimental approaches that would not be possible in other species. Future studies are needed to identify possible NB‐LRR proteins involved in the autoimmune response of Gβ mutants.

4. MATERIALS AND METHODS

4.1. Plant materials and growth conditions

Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum cv. “Moneymaker”) plants were grown in a glasshouse at 26–28°C during daytime and 22–24°C at night. For in vitro culture, tomato seeds were germinated on MS medium in darkness for 3 days and transferred to 16:8 h of light/dark at 26°C. Cotton plants, Gossypium barbadense cv. “Hai7124,” G. hirsutum cv. “TM1,” and G. hirsutum cv. “Coker201,” were grown in controlled growth chambers with a temperature: photoperiod of 25°C:16 h light and 23 C:8 h dark.

4.2. Cas9/gRNA vector construction and tomato transformation

The CRISPR/Cas9 vector was generated according to Liu et al. (2015). Tomato cv. “Moneymaker” transformation was performed as previously described (Dan et al., 2006). A genomic fragment containing the target site was amplified from transgenic plants and sequenced to verify the presence of mutations.

4.3. In vitro pollen germination assay

Tomato pollen grains were collected from flowers opened on the same day and incubated on germination medium as described previously (Karapanos et al., 2010). The number of germinated pollen grains was counted under a microscope after incubation at 26°C for 24 h. The pollen tube lengths were measured using ImageJ software.

4.4. VIGS in cotton

pTRV1 and pTRV2 vectors described in Liu et al. (2002) were used to perform VIGS in cotton. Construction of TRV–target gene vectors was done according to Gao et al. (2013). All VIGS vectors including pTRV1, pTRV2, and TRV–target plasmids were introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101. Primers to generate VIGS vectors are listed in Table S5.

Agroinfiltration of VIGS vectors into 1‐week‐old cotton cotyledons was performed as previously described (Gao et al., 2013). Agrobacterium containing pTRV1 were mixed with Agrobacterium carrying either pTRV2 or TRV–target vectors at a 1:1 ratio, adjusted to OD600 = .8, and infiltrated into cotyledons to generate empty vector infiltrated plants or target gene‐silenced plants, designated as TRV:00 or TRV:target gene, respectively. In double silencing experiment, the Agrobacterium concentration of single silencing genes was halved with empty vector pTRV2. In pathogen infection experiments, the Agrobacterium concentration was reduced to OD600 = .3 to slow down leaf death.

4.5. Measurement of flg22‐induced ROS production in tomato

Flg22‐induced ROS production was conducted following the protocol previously described (Schwizer et al., 2017) with some modifications. Half‐cotyledons of 2‐week‐old tomato seedlings were placed into a 96‐well plate and incubated in 225 μl of sterile water for 15 h. The water was substituted by 225 μl of a reaction solution containing 34 μg/ml luminol, 20 μg/ml horseradish peroxidase, and 30 nM flg22. Luminescence was measured in a GloMax 96 Microplate Luminometer (Promega).

4.6. DAB staining

H2O2 was visually detected in tomato seedlings and cotton leaves using DAB staining as previously described (Daudi & O'Brien, 2012) with modifications. Samples were immersed in fresh DAB staining solution and infiltrated under vacuum for 20 min. After incubation for 5 h in dark with gentle shaking, the samples were cleared in a bleaching solution containing ethanol/acetic acid/glycerol (3:1:1), boiled for 15 min and further kept in glycerol/ethanol (1:4) solution.

4.7. Trypan blue staining

Trypan blue staining was performed as described (Thordal‐Christensen et al., 1997). Two‐week‐old tomato seedlings were boiled in lactophenol trypan blue solution containing10 mL lactic acid, 10 mL phenol, 10 mL glycerol, 10 ml distilled water, 20 mg trypan blue and 80 ml ethanol for 2 min and kept at room temperature overnight. Samples were cleared by chloral hydrate solution (2.5 g/ml) for 24 h.

4.8. Quantification of endogenous H2O2

Endogenous H2O2 levels of 2‐week‐old tomato seedlings and cotton leaves were quantified as described (Jack et al., 2019). The samples were homogenized with 1 ml of .1% (w/v) trichloroacetic acid (TCA) and centrifuged at 4°C for 15 min at 13,000 g. Subsequently, 50 μl of supernatant was mixed with 50 μl of 10 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 6.5) and 100 μl of 1 M potassium iodide (KI) and incubated for 20 min in the dark before measuring absorbance values at 390 nm. Absorbance values were obtained using a PowerWave XS Microplate Reader (Bio‐Tek) and standardized for fresh weight.

4.9. SA quantification

Endogenous SA levels were determined by high‐performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) as previously described (Gao et al., 2013). 100 mg fresh sample of tomato seedlings or cotton leaves was grounded to fine powder with liquid nitrogen. The sample was homogenized in extraction buffer (methanol/water/acetic acid = 80: 19: 1) and shaken overnight at 4°C in dark. The supernatant was vacuum‐dried and redissolved in a 5% TCA aqueous solution. The aqueous solution was added to twice the volume of organic solution (ethyl acetate/cyclopentane/isopropanol = 50:50:1) for extraction. 1 ml methanol was added to the organic phase containing SA after drying by vacuum and used for HPLC analysis.

4.10. RNA extraction and qRT‐PCR

Total RNA was extracted from 2‐week‐old tomato seedlings and cotton leaves using ISOLATE II RNA Plant Kit (Bioline) and RNA Prep Pure Kit (TIAGEN, China), respectively. cDNA was synthesized using iScript™ cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio‐Rad, USA) according to manufacturer's instructions. qRT‐PCR was performed on a CFX96Real‐Time system (Bio‐Rad) using SYBR Green MasterMix (Roche, USA) following the manufacturer's protocol. The relative expression levels of targeted genes were normalized using either tomato Ubiquitin 3 (SlUB3) or cotton Ubiquitin 7 (GhUB7) as the reference genes and calculated by the 2‐ΔΔCT method. qRT‐PCR primers are listed in Table S5.

4.11. RNA sequencing and analysis

Transcriptome analysis was conducted as previously described (Long et al., 2019). mRNA was isolated from 10 μg of total RNA, fragmented, reverse‐transcribed with random primers, ligated with adapter index, and sequenced using the Illumina HiSeqTM 2000. The sequencing data were filtered using SolexaQA2.2, and clean reads were mapped to the cotton genome (http://mascotton.njau.edu.cn/info/1054/1118.htm) and normalized. For DEG analysis, the expression levels of all transcripts were compared between TRV:00 and TRV:β1 using DESeq software (FDR < .01 and log2Ratio ≥ 1). GO enrichment analysis was conducted using Blast2GO. The FPKM (fragments per kilobase of exon model per million mapped fragments) values of DEGs were used for heat‐map analysis.

4.12. Pathogen inoculation

Pathogen inoculation was performed according to Gao et al. (2016). Spore of fungal pathogens (V. dahliae and B. cinerea) were incubated on Potato‐Dextrose Agar (PDA) medium for 3 days before transplanting 1 cm2 colonies to a new PDA medium for another 5 days for spore‐bearing. Detached leaves of cotton plants 13–18 days after VISG infiltration were subjected to V. dahliae and B. cinerea infection. Lesion areas were measured using ImageJ software.

4.13. Statistical analyses

Statistical analysis of the differences between two groups was performed by Student's unpaired t‐test set for two‐tail distribution. Statistically significant difference between groups was determined if P‐value less than .05.

5. CONCLUSIONS

We show that the autoimmune phenotype of G protein beta mutants in monocot species extends to eudicots too, leaving Arabidopsis as the only known species with non‐autoimmune phenotype.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The Authors did not report any conflict of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.R.B., T.T.N., Y.T., W.G., L.L., and C.P.S. designed the research. T.T.N., G.W., L.L., and J.R.Z. performed the experiments. J.R.B. wrote the manuscript. J.R.B. and C.P.S. agree to serve as the author responsible for contact and ensures communication.

Supporting information

Figure S1 Characterization of CRISPR/Cas9 slgb1 mutants in tomato. (A) Schematic diagram of the wild type (WT) and mutated SlGB1 proteins. Upper row, WT SlGB1 protein indicating the position of the mutation (red arrow) upstream of the coil‐coiled domain. Middle row, mutated SlGB1_d3 protein encoded by the three bp‐deletion mutation. The deletion of three bases results in the omission of a threonine amino acid (a.a) in position 49 indicated by the purple mark. Lower row, mutated SlGB1_d13 protein encoded by the 13 bp‐deletion mutation. The deletion of 13 bases produces a frameshift that interrupts the canonical sequence of the protein at position 47 adding an unrelated peptide of 28 a.a before encountering a translational stop codon. In SlGB1_d3 and SlGB1_d13, gray lines indicate native SlGB1 sequences, the red line indicates unrelated peptide. (B) Sanger sequencing of PCR amplicons from WT and two homozygous mutant lines slgb1_d3d3 and slgb1_d13d13 show three bases and 13 bases deletions, respectively. (C) Amino acid sequences of WT and mutated SlGB1 proteins. Eight residues important for interaction with Gγ are highlighted in red. WD‐40 repeat domains starts and ends are highlighted in green and yellow, respectively. (D) The threonine amino acid in position 49 of the SlGB1 protein indicated by a red arrow is not conserved among plant Gβ subunits.

Figure S2 In vitro pollen germination assay. Tomato pollen grains derived from (A) WT and (B) biallelic slgb1_d3d13 plants were germinated on a solid germination medium. Pictures were taken 24 h after incubation. Scale bars = 100 μm. (C) Pollen germination rate and (D) average pollen tube length from WT and slgb1_d3d13 plants were measured after incubation for 24 h. In C, bars represent averaged values from three independent experiments with standard errors. Asterisk indicates statistically significant difference evaluated by Student's t‐test, * P < .05. In D, bars represent means ± SEM, n ≥ 65. “ns” indicates no significant difference (P > .05) by Student's t‐test.

Figure S3 Homozygous slgb1_d13d13 mutants exhibit seedling lethality. (A) Non‐germinated seeds and defective germination and growth seedlings from self‐pollinated heterozygous slgb1_d13wt plants two weeks after sowing on soil. (B) Seedlings from self‐pollinated slgb1_d13wt plants were germinated on MS medium containing 1% (w/v) sucrose. White boxes show homozygous slgb1_d13d13 seeds/seedlings identified by Sanger sequencing of the targeted genomic region. DAG, days after germination.

Figure S4 Genomic structure of cotton GhGB genes and cDNA regions used for VIGS constructs. (A) Schematic diagram of the GhGB genes showing the position of the genomic deletion in Gohir.D13G033100. Exons are represented as boxes. (B) Sequence alignment of GhGB1 (Gohir.A03G194000 and Gohir.D02G215100) and GhGB2 (Gohir.A13G034700 and Gohir.D13G033100) sequences. The target regions of VIGS vectors TRV:β1 and TRV:β2 are indicated with red and blue boxes, respectively. The in frame stop codon in Gohir.D13G033100 is indicated with a red box.

Figure S5 Silencing of GhGB1 and GhGB2 causes plant death in the upland cotton cultivar (A) ‘TM1’, (B) ‘Coker201’ and (C) the sea‐island ( Gossypium barbadense ) cotton cultivar ‘Hai7124’. (A and B) Plants were infiltrated with Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 carrying TRV:00, TRV:β1, TRV:β2 or TRV:β1 + TRV:β2 vectors. Pictures were taken 14–32 days after infiltration. (C) Plants were infiltrated with A. tumefaciens strain GV3101 carrying TRV:00, TRV:β1 or TRV:β2 vectors. Pictures were taken 35 days after infiltration.

Figure S6 Transcriptome analysis of Gβ‐silenced cotton plants. (A) Venn diagram of differentially expressed gene (DEGs) in the leaves of cotton plants infiltrated with TRV:β1 compared with TRV:00, 9, 11 and 13 d after VIGS infiltration. (B) Heat‐map showing the expression changes of all DEGs in both three groups of samples (TRV:β1 and TRV:00; 9 d, 11 d and13 d). (C) The TOP3 enrichment GO groups of the DEGs (TRV:β1 vs TRV:00) in 9 d, 11 d or 13 d samples. The bottom (X‐axis) is the gene numbers enriched in each term, and next to the bar (right) is the significance. (D) Heat‐map of a part of the upregulated genes in both three groups of samples (TRV:β1 and TRV:00; 9 d, 11 d and 13 d). For (B) and (D), The FPKM value of DEGs are shown by a color gradient from low (green) to high (red). The scale bar stand for the log2 fold changes in transcription level.

Figure S7 Expression of key genes involved in Jasmonic acid (JA)‐, auxin‐ and ROS detoxification‐ signaling pathways is altered in homozygous slgb1_d13d13 mutants. qRT‐PCR was performed to measure relative expression levels of (A) JA‐responsive genes, (B) auxin‐responsive genes and (C) genes related to ROS detoxification in two‐week‐old WT and slgb1_d13d13 tomato seedlings grown on MS medium. Gene expression was normalized to the tomato Ubiquitin 3 (SlUB3). Bars represent means ± SEM, n ≥ 3. Asterisks indicates significant difference evaluated by Student's t‐test, * P < .05, ** P < .01, *** P < .001. “ns” indicates no significant difference.

Table S1 Characterization of CRISPR/Cas9‐targeted mutations in the T0 generation

Table S5 List of primer sequences

Table S2 The differentially expressed genes in both three groups of samples (TRV:00 and TRV:β1; 9 d, 11 d and 13 d after VIGS infiltration)

Table S3 Part of the upregulated genes in both three groups of samples (TRV:00 and TRV:β1; 9 d, 11 d and 13 d after VIGS infiltration)

Table S4 Part of the upregulated genes in both three groups of samples (TRV:00 and TRV:β1; 9 d, 11 d and 13 d after VIGS infiltration)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Australian Research Council. T.T.N. received a PhD scholarship from Australia Award Scholarships.

Ninh, T. T. , Gao, W. , Trusov, Y. , Zhao, J.‐R. , Long, L. , Song, C.‐P. , & Botella, J. R. (2021). Tomato and cotton G protein beta subunit mutants display constitutive autoimmune responses. Plant Direct, 5(11), e359. 10.1002/pld3.359

Thi Thao Ninh and Gao Wei contributed equally to this work.

REFERENCES

- Beyer, E. M. (1976). A potent inhibitor of ethylene action in plants. Plant Physiology, 58, 268–271. 10.1104/pp.58.3.268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi, D. , Johnson, K. C. , Zhu, Z. , Huang, Y. , Chen, F. , Zhang, Y. , & Li, X. (2011). Mutations in an atypical TIR‐NB‐LRR‐LIM resistance protein confer autoimmunity. Frontiers in Plant Science, 2, 71. 10.3389/fpls.2011.00071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bommert, P. , Je, B. I. , Goldshmidt, A. , & Jackson, D. (2013). The maize Galpha gene COMPACT PLANT2 functions in CLAVATA signalling to control shoot meristem size. Nature, 502, 555–558. 10.1038/nature12583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botella, J. R. (2012). Can heterotrimeric G proteins help to feed the world? Trends in Plant Science, 17, 563–568. 10.1016/j.tplants.2012.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford, K. J. , Hsiao, T. C. , & Yang, S. F. (1982). Inhibition of ethylene synthesis in tomato plants subjected to anaerobic root stress. Plant Physiology, 70, 1503–1507. 10.1104/pp.70.5.1503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenya, E. , Trusov, Y. , Dietzgen, R. G. , & Botella, J. R. (2016). Heterotrimeric G‐proteins facilitate resistance to plant pathogenic viruses in Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh. Plant Signaling & Behavior, 11, e1212798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakravorty, D. , Trusov, Y. , Zhang, W. , Acharya, B. R. , Sheahan, M. B. , McCurdy, D. W. , Assmann, S. M. , & Botella, J. R. (2011). An atypical heterotrimeric G‐protein gamma‐subunit is involved in guard cell K(+)‐channel regulation and morphological development in Arabidopsis thaliana . The Plant Journal, 67, 840–851. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04638.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J. G. , Gao, Y. , & Jones, A. M. (2006). Differential roles of Arabidopsis heterotrimeric G‐protein subunits in modulating cell division in roots. Plant Physiology, 141, 887–897. 10.1104/pp.106.079202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J. G. , Pandey, S. , Huang, J. , Alonso, J. M. , Ecker, J. R. , Assmann, S. M. , & Jones, A. M. (2004). GCR1 can act independently of heterotrimeric G‐protein in response to brassinosteroids and gibberellins in Arabidopsis seed germination. Plant Physiology, 135, 907–915. 10.1104/pp.104.038992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J. G. , Willard, F. S. , Huang, J. , Liang, J. , Chasse, S. A. , Jones, A. M. , & Siderovski, D. P. (2003). A seven‐transmembrane RGS protein that modulates plant cell proliferation. Science, 301, 1728–1731. 10.1126/science.1087790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Y. T. , Li, Y. , Huang, S. , Huang, Y. , Dong, X. , Zhang, Y. , & Li, X. (2011). Stability of plant immune‐receptor resistance proteins is controlled by SKP1‐CULLIN1‐F‐box (SCF)‐mediated protein degradation. PNAS, 108, 14694–14699. 10.1073/pnas.1105685108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhury, S. R. , Bisht, N. C. , Thompson, R. , Todorov, O. , & Pandey, S. (2011). Conventional and novel Ggamma protein families constitute the heterotrimeric G‐protein signaling network in soybean. PLoS ONE, 6, e23361. 10.1371/journal.pone.0023361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui, H. , Gobbato, E. , Kracher, B. , Qiu, J. , Bautor, J. , & Parker, J. E. (2017). A core function of EDS1 with PAD4 is to protect the salicylic acid defense sector in Arabidopsis immunity. New Phytologist, 213, 1802–1817. 10.1111/nph.14302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dan, Y. , Yan, H. , Munyikwa, T. , Dong, J. , Zhang, Y. , & Armstrong, C. L. (2006). MicroTom‐‐a high‐throughput model transformation system for functional genomics. Plant Cell Reports, 25, 432–441. 10.1007/s00299-005-0084-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daudi, A. , & O'Brien, J. A. (2012). Detection of hydrogen peroxide by DAB staining in Arabidopsis leaves. Bio‐Protocol, 2, e263. 10.21769/BioProtoc.263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding, L. , Pandey, S. , & Assmann, S. M. (2008). Arabidopsis extra‐large G proteins (XLGs) regulate root morphogenesis. Plant Journal, 53, 248–263. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03335.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodds, P. N. , & Rathjen, J. P. (2010). Plant immunity: Towards an integrated view of plant‐pathogen interactions. Nature Reviews Genetics, 11, 539–548. 10.1038/nrg2812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feys, B. J. , Moisan, L. J. , Newman, M. A. , & Parker, J. E. (2001). Direct interaction between the Arabidopsis disease resistance signaling proteins, EDS1 and PAD4. The EMBO Journal, 20, 5400–5411. 10.1093/emboj/20.19.5400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feys, B. J. , Wiermer, M. , Bhat, R. A. , Moisan, L. J. , Medina‐Escobar, N. , Neu, C. , Cabral, A. , & Parker, J. E. (2005). Arabidopsis SENESCENCE‐ASSOCIATED GENE101 stabilizes and signals within an ENHANCED DISEASE SUSCEPTIBILITY1 complex in plant innate immunity. Plant Cell, 17, 2601–2613. 10.1105/tpc.105.033910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gantner, J. , Ordon, J. , Kretschmer, C. , Guerois, R. , & Stuttmann, J. (2019). An EDS1‐SAG101 complex is essential for TNL‐mediated immunity in Nicotiana benthamiana . Plant Cell, 31, 2456–2474. 10.1105/tpc.19.00099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao, M. , Wang, X. , Wang, D. , Xu, F. , Ding, X. , Zhang, Z. , Bi, D. , Cheng, Y. T. , Chen, S. , Li, X. , & Zhang, Y. (2009). Regulation of cell death and innate immunity by two receptor‐like kinases in Arabidopsis . Cell Host & Microbe, 6, 34–44. 10.1016/j.chom.2009.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao, W. , Long, L. , Xu, L. , Lindsey, K. , Zhang, X. , & Zhu, L. (2016). Suppression of the homeobox gene HDTF1 enhances resistance to Verticillium dahliae and Botrytis cinerea in cotton. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology, 58, 503–513. 10.1111/jipb.12432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao, W. , Long, L. , Zhu, L. F. , Xu, L. , Gao, W. H. , Sun, L. Q. , Liu, L. L. , & Zhang, X. L. (2013). Proteomic and virus‐induced gene silencing (VIGS) analyses reveal that gossypol, brassinosteroids, and jasmonic acid contribute to the resistance of cotton to Verticillium dahliae . Molecular & Cellular Proteomics, 12, 3690–3703. 10.1074/mcp.M113.031013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y. , Gu, H. , Leburu, M. , Li, X. , Wang, Y. , Sheng, J. , Fang, H. , Gu, M. , & Liang, G. (2019). The heterotrimeric G protein beta subunit RGB1 is required for seedling formation in rice. Rice, 12, 53. 10.1186/s12284-019-0313-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gou, M. , Shi, Z. , Zhu, Y. , Bao, Z. , Wang, G. , & Hua, J. (2012). The F‐box protein CPR1/CPR30 negatively regulates R protein SNC1 accumulation. The Plant Journal, 69, 411–420. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04799.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He, K. , Gou, X. , Yuan, T. , Lin, H. , Asami, T. , Yoshida, S. , Russell, S. D. , & Li, J. (2007). BAK1 and BKK1 regulate brassinosteroid‐dependent growth and brassinosteroid‐independent cell‐death pathways. Current Biology, 17, 1109–1115. 10.1016/j.cub.2007.05.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa, A. (2009). The Arabidopsis G‐protein beta‐subunit is required for defense response against Agrobacterium tumefaciens . Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry, 73, 47–52. 10.1271/bbb.80449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack, C. N. , Rowe, S. L. , Porter, S. S. , & Friesen, M. L. (2019). A high‐throughput method of analyzing multiple plant defensive compounds in minimized sample mass. Applications in Plant Sciences, 7, e01210. 10.1002/aps3.1210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, K. , Frick‐Cheng, A. , Trusov, Y. , Delgado‐Cerezo, M. , Rosenthal, D. M. , Lorek, J. , Panstruga, R. , Booker, F. L. , Botella, J. R. , Molina, A. , Ort, D. R. , & Jones, A. M. (2012). Dissecting Arabidopsis Gbeta signal transduction on the protein surface. Plant Physiology, 159, 975–983. 10.1104/pp.112.196337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin, S. , Zhang, X. , Nie, Y. , Guo, X. , Liang, S. , & Zhu, H. (2006). Identification of a novel elite genotype for in vitro culture and genetic transformation of cotton. Biologia Plantarum, 50, 519–524. 10.1007/s10535-006-0082-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karapanos, I. C. , Akoumianakis, K. A. , Olympios, C. M. , & Passam, H. C. (2010). Tomato pollen respiration in relation to in vitro germination and pollen tube growth under favourable and stress‐inducing temperatures. Sexual Plant Reproduction, 23, 219–224. 10.1007/s00497-009-0132-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemmerling, B. , Schwedt, A. , Rodriguez, P. , Mazzotta, S. , Frank, M. , Qamar, S. A. , Mengiste, T. , Betsuyaku, S. , Parker, J. E. , Müssig, C. , Thomma, B. P. H. J. , Albrecht, C. , de Vries, S. C. , Hirt, H. , & Nürnberger, T. (2007). The BRI1‐associated kinase 1, BAK1, has a brassinolide‐independent role in plant cell‐death control. Current Biology, 17, 1116–1122. 10.1016/j.cub.2007.05.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lease, K. A. , Wen, J. , Li, J. , Doke, J. T. , Liscum, E. , & Walker, J. C. (2001). A mutant Arabidopsis heterotrimeric G‐protein beta subunit affects leaf, flower, and fruit development. Plant Cell, 13, 2631–2641. 10.1105/tpc.010315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y. R. , & Assmann, S. M. (1999). Arabidopsis thaliana ‘extra‐large GTP‐binding protein’ (AtXLG1): A new class of G‐protein. Plant Molecular Biology, 40, 55–64. 10.1023/A:1026483823176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, X. , Clarke, J. D. , Zhang, Y. , & Dong, X. (2001). Activation of an EDS1‐mediated R‐gene pathway in the snc1 mutant leads to constitutive, NPR1‐independent pathogen resistance. Molecular Plant‐Microbe Interactions, 14, 1131–1139. 10.1094/MPMI.2001.14.10.1131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang, X. , Ding, P. , Lian, K. , Wang, J. , Ma, M. , Li, L. , Li, L. , Li, M. , Zhang, X. , Chen, S. , Zhang, Y. , & Zhou, J. M. (2016). Arabidopsis heterotrimeric G proteins regulate immunity by directly coupling to the FLS2 receptor. eLife, 5, e13568. 10.7554/eLife.13568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J. , Ding, P. , Sun, T. , Nitta, Y. , Dong, O. , Huang, X. , Yang, W. , Li, X. , Botella, J. R. , & Zhang, Y. (2013). Heterotrimeric G proteins serve as a converging point in plant defense signaling activated by multiple receptor‐like kinases. Plant Physiology, 161, 2146–2158. 10.1104/pp.112.212431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W. , Zhu, X. , Lei, M. , Xia, Q. , Botella, J. R. , Zhu, J.‐K. , & Mao, Y. (2015). A detailed procedure for CRISPR/Cas9‐mediated gene editing in Arabidopsis thaliana . Science Bulletin, 60, 1332–1347. 10.1007/s11434-015-0848-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y. , Schiff, M. , & Dinesh‐Kumar, S. P. (2002). Virus‐induced gene silencing in tomato. The Plant Journal, 31, 777–786. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2002.01394.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llorente, F. , Alonso‐Blanco, C. , Sanchez‐Rodriguez, C. , Jorda, L. , & Molina, A. (2005). ERECTA receptor‐like kinase and heterotrimeric G protein from Arabidopsis are required for resistance to the necrotrophic fungus Plectosphaerella cucumerina . The Plant Journal, 43, 165–180. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02440.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long, L. , Yang, W. W. , Liao, P. , Guo, Y. W. , Kumar, A. , & Gao, W. (2019). Transcriptome analysis reveals differentially expressed ERF transcription factors associated with salt response in cotton. Plant Science, 281, 72–81. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2019.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, H. , Yanofsky, M. F. , & Huang, H. (1991). Isolation and sequence analysis of TGA1 cDNAs encoding a tomato G protein alpha subunit. Gene, 107, 189–195. 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90318-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, H. , Yanofsky, M. F. , & Meyerowitz, E. M. (1990). Molecular cloning and characterization of GPA1, a G protein alpha subunit gene from Arabidopsis thaliana . PNAS, 87, 3821–3825. 10.1073/pnas.87.10.3821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackey, D. , Holt, B. F. III , Wiig, A. , & Dangl, J. L. (2002). RIN4 interacts with Pseudomonas syringae type III effector molecules and is required for RPM1‐mediated resistance in Arabidopsis . Cell, 108, 743–754. 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00661-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruta, N. , Trusov, Y. , Brenya, E. , Parekh, U. , & Botella, J. R. (2015). Membrane‐localized extra‐large G proteins and Gbg of the heterotrimeric G proteins form functional complexes engaged in plant immunity in Arabidopsis . Plant Physiology, 167, 1004–1016. 10.1104/pp.114.255703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason, M. G. , & Botella, J. R. (2000). Completing the heterotrimer: Isolation and characterization of an Arabidopsis thaliana G protein gamma‐subunit cDNA. PNAS, 97, 14784–14788. 10.1073/pnas.97.26.14784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason, M. G. , & Botella, J. R. (2001). Isolation of a novel G‐protein gamma‐subunit from Arabidopsis thaliana and its interaction with Gbeta. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta, 1520, 147–153. 10.1016/S0167-4781(01)00262-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCudden, C. R. , Hains, M. D. , Kimple, R. J. , Siderovski, D. P. , & Willard, F. S. (2005). G‐protein signaling: Back to the future. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, 62, 551–577. 10.1007/s00018-004-4462-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neves, S. R. , Ram, P. T. , & Iyengar, R. (2002). G protein pathways. Science, 296, 1636–1639. 10.1126/science.1071550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldham, W. M. , & Hamm, H. E. (2008). Heterotrimeric G protein activation by G‐protein‐coupled receptors. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 9, 60–71. 10.1038/nrm2299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, S. (2019). Heterotrimeric G‐protein signaling in plants: Conserved and novel mechanisms. Annual Review of Plant Biology, 70, 213–238. 10.1146/annurev-arplant-050718-100231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riehs‐Kearnan, N. , Gloggnitzer, J. , Dekrout, B. , Jonak, C. , & Riha, K. (2012). Aberrant growth and lethality of Arabidopsis deficient in nonsense‐mediated RNA decay factors is caused by autoimmune‐like response. Nucleic Acids Research, 40, 5615–5624. 10.1093/nar/gks195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rietz, S. , Stamm, A. , Malonek, S. , Wagner, S. , Becker, D. , Medina‐Escobar, N. , Vlot, A. C. , Feys, B. J. , Niefind, K. , & Parker, J. E. (2011). Different roles of Enhanced Disease Susceptibility1 (EDS1) bound to and dissociated from Phytoalexin Deficient4 (PAD4) in Arabidopsis immunity. New Phytologist, 191, 107–119. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.03675.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwizer, S. , Kraus, C. M. , Dunham, D. M. , Zheng, Y. , Fernandez‐Pozo, N. , Pombo, M. A. , Fei, Z. , Chakravarthy, S. , & Martin, G. B. (2017). The tomato kinase Pti1 contributes to production of reactive oxygen species in response to two flagellin‐derived peptides and promotes resistance to Pseudomonas syringae infection. Molecular Plant‐Microbe Interactions, 30, 725–738. 10.1094/MPMI-03-17-0056-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shigenaga, A. M. , & Argueso, C. T. (2016). No hormone to rule them all: Interactions of plant hormones during the responses of plants to pathogens. Seminars in Cell and Developmental Biology, 56, 174–189. 10.1016/j.semcdb.2016.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirano, Y. , Kachroo, P. , Shah, J. , & Klessig, D. F. (2002). A gain‐of‐function mutation in an Arabidopsis toll interleukin1 receptor‐nucleotide binding site‐leucine‐rich repeat type R gene triggers defense responses and results in enhanced disease resistance. Plant Cell, 14, 3149–3162. 10.1105/tpc.005348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramaniam, G. , Trusov, Y. , Lopez‐Encina, C. , Hayashi, S. , Batley, J. , & Botella, J. R. (2016). Type B heterotrimeric G protein gamma‐subunit regulates auxin and ABA signaling in tomato. Plant Physiology, 170, 1117–1134. 10.1104/pp.15.01675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun, T. , Zhang, Y. , Li, Y. , Zhang, Q. , Ding, Y. , & Zhang, Y. (2015). ChIP‐seq reveals broad roles of SARD1 and CBP60g in regulating plant immunity. Nature Communications, 6, 10159. 10.1038/ncomms10159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temple, B. R. , & Jones, A. M. (2007). The plant heterotrimeric G‐protein complex. Annual Review of Plant Biology, 58, 249–266. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.58.032806.103827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thordal‐Christensen, H. , Zhang, Z. , Wei, Y. , & Collinge, D. B. (1997). Subcellular localization of H2O2 in plants. H2O2 accumulation in papillae and hypersensitive response during the barley‐powdery mildew interaction. The Plant Journal, 11, 1187–1194. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1997.11061187.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thung, L. , Trusov, Y. , Chakravorty, D. , & Botella, J. R. (2012). Ggamma1+Ggamma2+Ggamma3=Gbeta: The search for heterotrimeric G‐protein gamma subunits in Arabidopsis is over. Plant Physiology, 169, 542–545. 10.1016/j.jplph.2011.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres, M. A. , Morales, J. , Sanchez‐Rodriguez, C. , Molina, A. , & Dangl, J. L. (2013). Functional interplay between Arabidopsis NADPH oxidases and heterotrimeric G protein. Molecular Plant‐Microbe Interactions, 26, 686–694. 10.1094/MPMI-10-12-0236-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trusov, Y. , & Botella, J. R. (2012). New faces in plant innate immunity: Heterotrimeric G proteins. Journal of Plant Biochemistry and Biotechnology, 21, 40–47. 10.1007/s13562-012-0140-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trusov, Y. , & Botella, J. R. (2016). Plant G‐proteins come of age: Breaking the bond with animal models. Frontiers in Chemistry, 4, 24. 10.3389/fchem.2016.00024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trusov, Y. , Rookes, J. E. , Chakravorty, D. , Armour, D. , Schenk, P. M. , & Botella, J. R. (2006). Heterotrimeric G proteins facilitate Arabidopsis resistance to necrotrophic pathogens and are involved in jasmonate signaling. Plant Physiology, 140, 210–220. 10.1104/pp.105.069625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trusov, Y. , Rookes, J. E. , Tilbrook, K. , Chakravorty, D. , Mason, M. G. , Anderson, D. , Chen, J. G. , Jones, A. M. , & Botella, J. R. (2007). Heterotrimeric G protein gamma subunits provide functional selectivity in Gbetagamma dimer signaling in Arabidopsis . Plant Cell, 19, 1235–1250. 10.1105/tpc.107.050096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trusov, Y. , Sewelam, N. , Rookes, J. E. , Kunkel, M. , Nowak, E. , Schenk, P. M. , & Botella, J. R. (2009). Heterotrimeric G proteins‐mediated resistance to necrotrophic pathogens includes mechanisms independent of salicylic acid‐, jasmonic acid/ethylene‐ and abscisic acid‐mediated defense signaling. The Plant Journal, 58, 69–81. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03755.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsugama, D. , Liu, S. , & Takano, T. (2013). Arabidopsis heterotrimeric G protein β subunit, AGB1, regulates brassinosteroid signalling independently of BZR1. Journal of Experimental Botany, 64, 3213–3223. 10.1093/jxb/ert159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullah, H. , Chen, J. G. , Temple, B. , Boyes, D. C. , Alonso, J. M. , Davis, K. R. , Ecker, J. R. , & Jones, A. M. (2003). The beta‐subunit of the Arabidopsis G protein negatively regulates auxin‐induced cell division and affects multiple developmental processes. Plant Cell, 15, 393–409. 10.1105/tpc.006148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urano, D. , & Jones, A. M. (2013). Heterotrimeric G protein‐coupled signaling in plants. Annual Review of Plant Biology, 65, 365–384. 10.1146/annurev-arplant-050213-040133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]