Abstract

Background

Catastrophic natural disasters and epidemics claim thousands of lives and have severe and lasting consequences, accompanied by human suffering. The Ebola epidemic of 2014–2016 and the current COVID-19 pandemic have revealed some of the practical and ethical complexities relating to the management of dead bodies. While frontline staff are tasked with saving lives, managing the bodies of those who die remains an under-resourced and overlooked issue, with numerous ethical and practical problems globally.

Methods

This scoping review of literature examines the management of dead bodies during epidemics and natural disasters. 82 articles were reviewed, of which only a small number were empirical studies focusing on ethical or sociocultural issues that emerge in the management of dead bodies.

Results

We have identified a wide range of ethical and sociocultural challenges, such as ensuring dignity for the deceased while protecting the living, honouring the cultural and religious rituals surrounding death, alleviating the suffering that accompanies grieving for the survivors and mitigating inequalities of resource allocation. It was revealed that several ethical and sociocultural issues arise at all stages of body management: notification, retrieving, identification, storage and burial of dead bodies.

Conclusion

While practical issues with managing dead bodies have been discussed in the global health literature and the ethical and sociocultural facets of handling the dead have been recognised, they are nonetheless not given adequate attention. Further research is needed to ensure care for the dead in epidemics and that natural disasters are informed by ethical best practice.

Keywords: health policies and all other topics, COVID-19, public health, review

Key questions.

What is already known?

Catastrophic natural disasters and pandemics, including the COVID-19 pandemic, claim millions of lives and have severe and long-lasting consequences.

Dealing with the complexities of the management of dead bodies is an integral part of tackling pandemic outbreaks and natural disasters.

What are the new findings?

This literature review reveals that the management of dead bodies remains an unresolved challenge, with numerous ethical and practical issues occurring globally.

There is a very limited body of literature dedicated to the ethical and social issues that emerge in the management of dead bodies.

This study reveals the inequalities in the treatment of dead bodies in global health.

What do the new findings imply?

The ethical and social implications of managing dead bodies have significant consequences for survivors, communities and nations.

The significance of social and ethical issues emerging in managing dead bodies is under-researched.

Unless more attention is paid the socioethical issues of dead body management, there could be mismanagement of bodies from the perspectives of the individual families, cultures and communities involved.

Introduction

Catastrophic natural disasters and epidemics claim thousands of lives and have severe and lasting consequences, accompanied by human suffering. For example, the devastating Haitian earthquakes of 2010 and now in 2021, the Ebola epidemic of 2014–2016, the current COVID-19 pandemic has revealed some of the practical and ethical complexities related to the management of dead bodies. Recently, some of the most searing and distressing media images of the current pandemic or the Haitian earthquake of 2021 relate to the handling of the dead. There have been images of bodies recovered from the rubble of homes destroyed by the quake in Haiti,1 mass graves in Brazil2 and bodies cremated en masse3 or dumped in rivers in India.4

Epidemics and natural disasters exacerbate the practical difficulties connected with proper and respectful storage of dead bodies. In most settings, scarce burial spaces or overburdened crematoria are some of the challenges that need to be addressed at times of great urgency, so that hundreds of dead bodies can be dealt with in a short space of time. In the global South, resource constraints, inadequate or lack of capacity makes bad situations worse.

How the bodies of the deceased are handled can have significant health implications and raise sociocultural and ethical dilemmas.1 The Ebola epidemic particularly demonstrated the ethical tensions arising from questions such as how a contagion should be managed to ensure the safety of the living, while being mindful of and showing respect for persons and any social–cultural significance related to sacred obligations towards the dead.5 Outbreaks and natural disasters have shown that mismanagement of the dead can show distrust and undermine public health efforts to contain diseases and can also contribute to long-term trauma for survivors when the bodies of loved ones are not considered to have been treated with respect.6 7 Therefore, those/such significant ethical issues deem intertwined with practical challenges arising in the time of the crisis.

Despite the numerous ethical issues at stake such as respecting dignity of the dead or alleviating the suffering of the families who have lost a loved one, policymakers still put emphasis on handling dead bodies through the sequential process of notification, retrieval, storage and finally disposal8 9 in order to address public health benefits. Furthermore, the ethical issues arising in managing the dead have been under-researched by the global health researchers.

The dead body is often perceived as an ‘inconvenience with the potential to pose a practical risk to the living’.10 Therefore, these sequential steps help to dispose of the body, portraying the idea that the risk is eliminated. However, the gaps in addressing the ethical and social aspects of managing the dead create distress to the communities impacted by such deaths.

As such, this timely review seeks to engage with the ethical issues involved in the management of dead bodies during pandemics and natural disasters to provide a comprehensive understanding of the way dead bodies are treated and to highlight the various ethical and social implications of these practices in global health.

Methods

This study has sought to review published literature on ethical and sociocultural concerns in managing dead bodies during two emerging types of mass fatality events: natural disasters such as earthquakes, tsunamis, floods or hurricanes and infectious disease outbreaks such as Ebola, COVID-19 and others (epidemics/pandemics).

We recognise that natural disasters and infectious disease outbreaks might present different contexts in terms of temporality and the significance of the body (eg, health risks associated with infectious bodies). However, by their nature, natural disasters and infectious disease outbreaks present a particularly challenging environment for dead body management. They involve periods of uncertainty, disturbance and competing needs while resources and capacities are often limited; often there is a time pressure to respond quickly to minimise illness, death and alleviate human suffering. All these factors add to the fact that managing dead bodies conducted during mass fatality events raises particularly complex ethical challenges.

The aim of this review was to investigate health-related emergencies impacting global health concerns. Therefore, while we acknowledge there are other forms of mass death occur resulting from human-made disasters involving events such as conflicts, large-scale accidents, displacement of people, they fall beyond the scope of this review and have not been included.

A scoping review was identified as suitable to meet the objectives of this study. First, it allowed for a general exploration of the related literature and more flexibility than traditional systematic review11 12 Second, it was able to account for vast, diverse and complex literature, including research using quantitative or qualitative methodologies.11 13

The original search was conducted on 17 March 2020, and searches were repeated on 29 May 2020 and 2 June 2020 and 13 April 2021 to update the findings (NR). The following databases were searched (table 1).

Table 1.

Databases searched for literature review

| Database | Interface | Coverage |

| Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts, Sociological Abstracts International Bibliography of the Social Sciences (IBSS) | Proquest | 1987–present, 1951–present, 1952–present |

| Embase | OvidSP | 1974–present |

| Ovid MEDLINE(R) Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE(R) Daily and Ovid MEDLINE(R) | OvidSP | 1946–present |

| Philosophers Index | EBSCOHost | |

| PsycINFO | OvidSP | 1806–present |

| Science Citation Index, Social Science Citation Index & Arts & Humanities Citation Index | Thomson Reuters | 1945–present |

| Medrxivr | https://mcguinlu.shinyapps.io/medrxivr/ | |

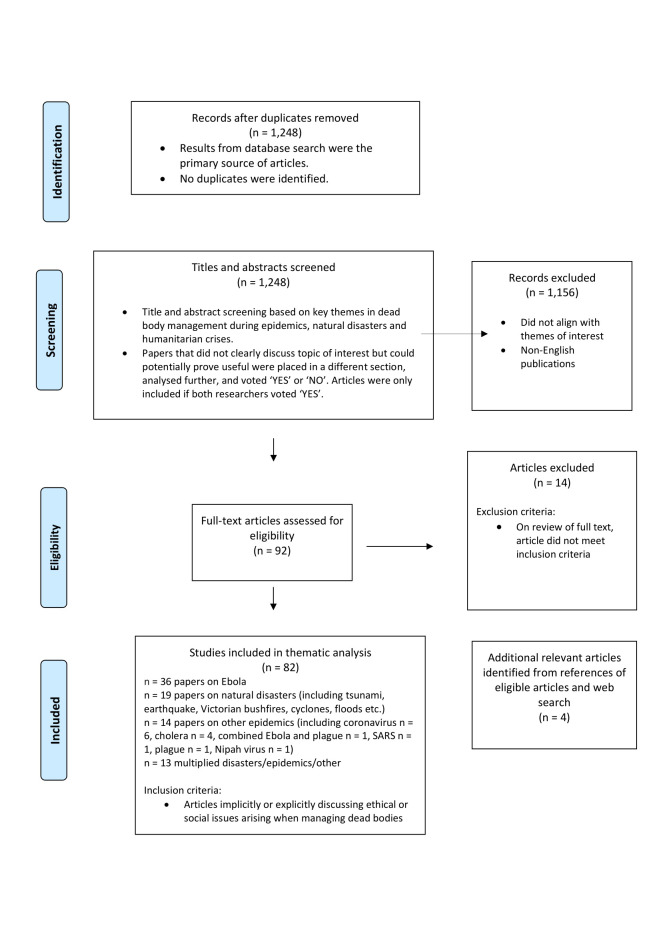

We searched using free test keywords and subject headings for the following concepts—(natural disasters OR humanitarian crises OR pandemics) AND (post-mortem procedures) AND (attitudes OR death rites OR ethics). The full-search strategy is available in online supplemental appendix 1. We did not limit our search by date, language or publication type, but animal studies were excluded where possible. However, non-English publications were excluded at the screening stage (see figure 1).

Figure 1.

Diagram of scoping review.

bmjgh-2021-006345supp001.pdf (1.1MB, pdf)

A total of 1248 abstracts identified by the strategy were screened by two researchers (HS and FA), 92 of which were flagged as being particularly relevant and assessed for eligibility (see figure 1). The relevance was determined by explicit or implicit mention of ethical or social challenges arising in the management of dead bodies. The list of abstracts was divided equally between two researchers (HS and FA). Each reviewer marked abstracts as either: relevant to the review, ‘potentially’ relevant and non-relevant. Abstracts categorised as ‘potentially relevant’ were then coreviewed, and a decision was made whether to include them. In addition, 20% of abstracts marked as relevant were cross reviewed. All abstracts were imported into an Excel spreadsheet, which was used to track decisions during the screening. After further screening, 82 full texts of articles were included for the review. The full text of the final 82 shortlisted papers was divided, read and analysed (HS and FA).

The analysis was conducted using thematic analysis to allow to map out the issues, descriptions and interpretations around the management of dead bodies in global health (HS, FA and PK). This approach enables the analysis of the data in an iterative process, allowing flexibility and revisiting the validity of the codes as the analysis progresses.14 Descriptive codes were developed to chart the ethical and practical issues emerging in the management of dead bodies and recommendations for best practices (HS, FA and PK). Coding of the full text of the articles was conducted in Excel by the research team. To assure consistency of coding for reliability of the results, a sample of 10% of articles was cross-checked.2

Findings

The findings of this review demonstrate that management of dead bodies in epidemics or natural disasters raises a wide range of ethical and sociocultural challenges. Those challenges include ensuring dignity for the deceased while protecting the living, honouring the cultural and religious rituals surrounding caring for the dead, respecting grieving families and mitigating inequalities of resource allocation. It is also apparent that there are different stakeholders involved in the management of dead bodies, including family members, communities, religious leaders and traditional healers, ‘last responders,’ for example, burial teams, pathologists, national authorities, Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) and global organisations. The findings show that while the perspectives of the stakeholders sometimes converge, in many cases their priorities differ, leading to tensions and open conflicts.

The section below discusses how these ethical and social challenges manifest in the context of epidemics and natural disasters, as presented in the extant literature, and how different stakeholders navigate dead body management (see figure 2). The section is divided into five themes: (a) the relationship between respectful treatment of the dead and the well-being of the living, (b) the dilemmas arising in using mass burials and cremation for fear of infection or in managing a large number of fatalities, (c) the importance of identification of victims and ‘finding closure’ for grieving families, (d) the tension that arises between introducing public health measures to manage the crisis and following cultural and religious obligations towards the dead and (e) inequality in caring for the dead.

Figure 2.

Complex ethical concerns arise in managing dead bodies in times of crisis. Adequate dead body handling signifies respectful treatment of the dead and has significant consequences for the living. Credit Anna Suwalowska. Copyright ©Anna Suwalowska (2021).

Dignity for the dead or else trauma for the living

Disasters and epidemics exceed local coping capacity and put an enormous strain on survivors. The initial response after any disaster is to retrieve bodies to identify and bury the dead.6 8 9 15 16 Studies have reported that community members at the disaster site will often take it on themselves to recover their dead.6 16 17 However, many bodies and limited resources can overwhelm volunteers and rescue forces; sometimes, when deaths were reported, it would take days, weeks or even months after the disaster for the bodies to be retrieved.8 16 Such delays raise concerns about respectful treatment of the dead. For example, following the Haitian earthquake of 2010, some bodies were not removed ‘even over a year after the incident’.18 In some cases, the delay in reaching the dead bodies, paired with high temperatures, resulted in the retrieval of bodies in a highly decomposed state or ‘almost skeletonised’19 or dead bodies ‘emanating a strong smell’16; body decomposition diverts from societal norms how the dead should be treated with dignity. During the COVID-19 pandemic, there have been reported cases of serious mismanagement of the deceased across the globe. For example, in Ecuador, some families had to search through body bags in morgues to find and identify their deceased.20 The body collection process, even if professionalised, can be culturally insensitive. During the Ebola epidemic of 2014, a challenge discussed by the community was the way the body collection team handled dead bodies.5 21–23 The use of sprayers, body bags and full Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) during the Ebola epidemic was an unfamiliar process for many community members. Studies have highlighted community members’ dissatisfaction with the way the body collection team operated, that is, ‘disrespectfully’ ‘taking away’ the bodies.23 Such challenges have raised questions about respecting the dignity of the dead and psychological repercussions for the survivors,6 18 24 as well as for rescue forces,25 26 who may also suffer psychological trauma.

Furthermore, studies have reported that natural disasters and epidemics have exacerbated the problem with storage of dead bodies, thereby highlighting ethical issues relating to resource allocation and respect for dead people,27–29. While it is recommended that bodies should be kept away from public view, in a cool place to secure them from potential damage,29 dead bodies are not always treated with the dignity they would receive in non-disaster times.30 31 Entress et al have reported that deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic have overwhelmed the capacity of morgues worldwide.20 This situation is not different from earlier epidemics and natural disasters. The literature reports that, in many cases, dignified methods of storing the dead were not accessible due to the limited capacity and insufficient mortuary resources available even prior to the disaster or pandemic.18 26 27 32 Due to the vast number of bodies, morgue spaces fill up quickly, leading to the use of other less desirable alternatives; for instance, after the Indian Ocean tsunami of 2004, the courtyards of temples in Thailand were used for temporary storage of bodies,33 and local authorities used dry ice to preserve the deceased, even though it disfigured the body.34 COVID-19 victims were stored on ice rinks or in empty hospital rooms.20 Other instances of local authorities using alternative methods for short-term storage for bodies include, an example, from Indonesia after the Indian Ocean tsunami of 2004: 600 bodies were buried temporarily in shallow trench graves.8 A lack of preparedness in the death care sector is apparent in high-income and low-income settings alike. A study from the USA, published in 2011, warned that ‘a highly lethal pandemic could lead to large numbers of deaths’ and would overwhelm the responders.35

Body disposal during mass fatalities—fear of infectious bodies, use of mass burial and cremation

An array of literature report that communities or even local authorities rushing to bury their dead is influenced by the misconception that bodies of natural disaster victims are infectious.8 16 17 36 This is a persistent and wrong belief and has been labelled as the ‘disaster myth that does not want to die’.9 15 30 In contrast to natural disaster fatalities or COVID-19 victims,37 the corpses of Ebola victims were highly contagious.15 38–42 This was also the case with plague and cholera outbreaks.43–48

Studies on natural disasters report that, in many instances, this fear of infection and the logistical difficulties of managing a large number of fatalities force local authorities or even community members to bury their dead in mass graves or to cremate them.8 16 18 19 49–51 As a case in point, after the earthquake in Haiti in 2010, the community resorted to drastic and upsetting measures to dispose of the dead, such as ‘dous(ing) bodies with gasoline and (lighting) them on fire’.18 Mass graves have also been used in the current COVID-19 pandemic. A study reported mass graves being dug in New York City to manage the burial of the increasing numbers of COVID-19 victims.20 Such actions have significant ethical and social consequences. Any form of mass burial goes against commonly held beliefs about respectful burial ceremonies for the dead.52 Mass burials are often perceived as being carried out ‘unceremoniously’, without preserving the individuality and dignity of the dead.53 Long trenches dug with bulldozers,18 containing thousands of dead bodies ‘tossed in huge grave pits’ in several layers without any planning,54 have been put forward as examples of mistreatment of bodies. For example, some mass graves in Indonesia after the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami contained up to 60 000–70 000 victims.8 Furthermore, in some instances, the literature reports on the utilisation of unnecessary ‘precautions’ such as adding chlorinated lime as a ‘disinfectant’ in mass graves and routine disinfection of the body.10 15 Second, another concern relating to mass burial is that dead bodies are often not identified; this deprives the dead person of their individuality and dignity by not treating them as ‘somebody’ and ‘not completing the biography of the person up to the point at which they die,’10 in the most extreme circumstances of natural crisis or infectious disease outbreak.10

Lack of identification—uncertainty and grieving

There is a consensus in the literature that bereaved families need certainty about the fate of the dead in order to ‘find closure’.53 Therefore, not identifying victims creates stress and uncertainty and ‘complicates the mourning process for the survivors’6 18 53; this has a long-term psychological consequence for families.24 29 53 55

The significance of identifying bodies has been said to be ‘one of the most basic of all human rights’.19 Indeed, ‘there is an expectation and determination that all dead must be identified’.33 From the medicolegal perspective, identification of the dead is the most important aspect of mass disaster investigation.19 56 Identification is needed to obtain a death certificate in order to claim insurance, remarry or solve other legal disputes19 32 53 55 and is required to release a body from the mortuary.57

The identification aspect of dead body management has been accentuated to have innumerable practical and psychosocial benefits and in some cases health caveats. Despite this, the identification of dead bodies poses a huge challenge during disasters.24 28 53 58 In many cases, limited resources, the high number of dead bodies and the overall chaos in response to the crisis contribute to the lack of identification. Because of improper storage, dead bodies become unidentifiable and untraceable for family members,18 32 further amplifying their grief,6 53 and constituting as an obstacle to the respectful treatment of the bodies. Moreover, given that the actions of many actors involved in handling the dead remain uncoordinated and chaotic,8 32 this contributes to the mismanagement of the bodies. Several studies have stressed that managing dead bodies after natural disasters happens in a context of uncertainty: breakdown of normality caused by searing scenes of abandoned bodies17 18 35 54 or a lack of information on how to manage dead bodies.15 18 59 Community members are also unaware of the consequences of burying their dead with no permanent identification, such as a tag, and with no photos or other forms of postmortem identification16 that would be helpful for future exhumations to identify the victims.19 This results in trauma for the survivors16 18 24 53 54 and sometimes disrespectful treatment of the dead.

Following cultural and religious obligations towards the dead during natural disasters and epidemics

The literature discusses the significance surrounding death, in particular, the role of religious and cultural practices that follow a death. There are differences in funeral rites that influence the care of the dead body and have significant social and psychological importance for the families of the deceased in terms of allowing them to mourn for their loved ones.31 60

For many practicing Muslims, burial is stipulated to happen within 24 hours. For many Christians, there is not such rigid adherence to a time frame.5 16 59 Christian burials often take place weeks after the death, accompanied by a wake to pay respect to the dead.5 60

There are many instances, however, when due to restrictive policies, the chaos of a crisis or an overwhelming number of dead bodies, it is impossible to perform the rites required by the religion/culture despite all efforts.18 This in turn aggravates the trauma for the families, who become distressed that their loved ones have not been treated respectfully. Sumathipala et al report that neither collective nor individual religious rites were performed for the dead buried in mass graves in Sri Lanka following the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami.53 To maintain the dignity of the body, policymakers were mandated to cover each cadaver in white cloth if a casket was not available.

The Ebola epidemic of 2014, in particular, demonstrated the ethical tensions between managing a contagion and the safety of the living and, at the same time, the value placed on sacred obligations towards the dead.21 61–67 As the bodies of Ebola victims were infectious, burial rites and mourning ceremonies were identified as the most significant drivers of the disease.40–42 68–76 The regulation of burials, a key concern for reducing Ebola transmission, was a top priority in the Ebola response, with guidance recommended by international organisations across affected countries.5 22 76–78 Many studies describe tensions during the Ebola epidemic between local practices and the national policymakers/international organisations that imposed ‘safe burial’ policies.5 21 22 45 66 79 A study from Liberia states that cremation was ‘a taboo that was accepted reluctantly and incompletely’.80 The cremation order, although efficient, was perceived as lacking understanding and respect for the spiritual significance of the dead and the psychological repercussions for families and was, therefore, met with resistance.49–52 81 82 These studies suggest that local culture was neglected ‘as an inconvenient and backwards obstacle to the elimination of the virus’5 or misrepresented.77 83 The communities were blamed for their ‘resistance’ to the epidemic response; however, in fact, limited resources and inconsistent communication with the burial teams contributed to some people personally burying their deceased loved ones before the arrival of the body collection team.21 22 61 72 79

The literature agrees that religious leaders are trusted, and that they could communicate matters that require cultural or religious modification. While the studies have underscored the psychological distress associated with regulations restricting attendance at funerals,31 84 they also highlight the engagement of religious leaders in promoting safe burials,23 62 72 85 recognising the importance of postmortem procedures59 86 and giving permission for body retrieval.16

The current COVID-19 pandemic has likewise significantly altered burial ceremonies around the world and impacted the grieving process for families.20 31 60 87 88 As in the Ebola epidemic discussed earlier, during COVID-19, regulations have been introduced to regulate the number of people attending funerals, and so certain rites performed on a dead body could not be honoured.20 31 Moreover, many people died alone in hospital, which is perceived as ‘a bad death’, and their loved ones were forced to mourn in isolation, which has negative psychological effects.7 31 The literature reports the potential psychological impact of these pandemic losses. Enabling the living to find closure by at least giving them some semblance of a funeral ritual is an integral part of the balance between managing the dead and helping the living. While the experiences from past crises show that funeral rites can be modified—for example, a study from Japan discussed post-tsunami burials without bodies,89 and practices were modified after the earthquake in Haiti in 201018—there is a growing body of COVID-19 literature that focuses on how such symbolic representations could aid in improving the well-being of the grieving survivors.31 87

Inequality in caring for the dead

There are marked inequalities visible in the treatment of dead bodies belonging to foreign nationals and local victims after disasters in the literature reviewed. The literature points to a trend of preferential treatment for the bodies of foreign nationals.18 53 59 First, the evidence indicates that the governments of high-income countries make substantial efforts to identify and obtain the bodies of their citizens and return them to their families in their respective countries; however, the governments of countries where such disasters happen often do not have similar resources available.18 53 A case in point, the USA and the UN deployed special resources, so that the bodies of their nationals and staff could be recovered and identified after the Haitian earthquake of 2010 and in Thailand following the Indian Ocean tsunami of 2004.18 In comparison, the majority of the Asian nationals who died during the tsunami were buried or cremated without identification,53 due to lack of technology or sufficient forensic capability, among other reasons.8 It has been estimated that only 5000–6000 of the estimated 2 50 000–3 00 000 tsunami victims were formally identified.34

Furthermore, retrieval of the bodies of foreign nationals is conducted with a lack of sensitivity to local people, who were not able to identify their dead family members due to the lack of resources.53 In search of foreign nationals in Sri Lanka following the Indian Ocean tsunami of 2004, six mass graves were exhumed in order to retrieve and identify the missing bodies of foreign nationals.53 One paper reported a situation where out of the 155 bodies exhumed, only 18 were tourists8; in another case, in search of one missing Japanese tourist, a mass grave of 26 was exhumed.32 This action impacted the grieving process of many Sri Lankans whose family members were exhumed in order to find foreign nationals.53

Even among the local population, some bodies received preferential treatment, reflecting the realities of pre-existing socioeconomical divides. A cremation order in Liberia aimed at curbing the Ebola epidemic resulted in ‘an informal economy of dead bodies’.77 Those who were able bribed burial teams and organised funerals in cemeteries, circumventing the official cremation order, to avoid a method of disposal that they found culturally and religiously vile.5 77 In contrast, those who were less privileged had to cremate their dead.5 77 Similarly, the bodies of people experiencing deprivation were less likely to be identified after the earthquake in Haiti in 2010 due to the general lack of any form of identification among the deprived.18

Some studies have pointed to the mass media’s role in perpetuating inequalities through sensational or inaccurate reporting. An Ebola epidemic study pointed to the biased narrative of the Western media, which mispresented burial practices ‘as exotic and mystifying’.52 There is also a concern that indiscriminate photography of the dead constitutes a breach of the privacy, dignity and rights of those with little power.54 Consequently, there is a consensus in the literature that the significant amount of media interest resulting from disasters needs to be managed.22 28 54 90 This review has also found a small number of studies that discussed the significance of conducting research on dead bodies to find causes of death86 and the importance of collecting mortality data to understand the scale of the crisis.91 Two research papers brought to attention the issues around organ donation and the availability of dead bodies for medical education postepidemics.37 92

Discussion

This scoping review of the literature examined the management of dead bodies during epidemics and natural disasters. We have identified a wide range of ethical and sociocultural challenges, such as ensuring dignity for the deceased while protecting the living, honouring the cultural and religious rituals surrounding death, alleviating the suffering that accompanies grieving for the survivors and mitigating inequalities of resource allocation. It was revealed that several ethical and sociocultural issues arise at all stages of body management: notification, retrieving, identification, storage and burial of dead bodies.

This scoping review shows that the management of dead bodies remains an unresolved issue, with numerous ethical and practical issues occurring globally, which are nonetheless not given adequate attention by the policymakers and researchers. This is a crucial concern. Adequate dead body handling signifies respectful treatment of the dead, and as argued by Jones and Whitaker, a dead body should always be regarded as ‘somebody’s body’.93 Moreover, ‘the care of the dead and of the living are intimately connected,’ and appropriate management of the dead contributes to the recovery of survivors.10 When this is not the case, families of the deceased may suffer additional psychological harm due to the way their dead were handled. Further mismanagement of dead bodies has grave consequences, such as distrust of public health policies in a time of crisis, when rescuing the living is given immediate priority. As mapped out in this review, the mismanagement of dead bodies in epidemics and natural disasters is a persistent challenge; this issue remains apparent in the current COVID-19 pandemic.

The COVID-19 pandemic, as earlier health and natural crises, has overwhelmed the infrastructure for dealing with the deceased. As a result, the dead has not been treated with dignity, and their families have suffered not only from the loss of a loved one but also from the way their body has been handled. The COVID-19 pandemic, like earlier crises with mass fatality, has exacerbated the practical difficulties with adequately and respectfully storing dead bodies, scarce burial spaces and burying the deceased in a way that respects their dignity.

Drawing lessons from current and previous pandemics and natural disasters, national and global policymakers should prepare emergency response plans for future crises with a particular focus on poorly resourced countries that do not have the capacity for a possible COVID-19 mass death scenario. These plans and strategies should take into consideration the prevention of possible infections, respectful and safe storage and transport of the dead bodies and dignified burial. They should be developed in consultation with the stakeholders who are involved in managing dead bodies and supported by research carried out by global health researchers and other scholars dealing with death and bodies. The policymakers should map out the responsibilities, expectations and values of these stakeholders, whose views, as this review has demonstrated, often do not converge. Such preparedness will help to avoid disrespectful handling of the dead and potential trauma for the living during possible future mass fatality events. There is also a necessity of memorialisation or dealing with collective loss at the national and community level. Logan94 discussed, for example, a number of ways bushfire deaths in Australia are commemorated by the local communities and nationally. Simpson et al,7 in their study on ‘good’ and ‘bad’ deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK, concluded that the pandemic was ‘as a traumatic period of national loss that transcended ethnic or religious boundaries’ and recommended the collective memorialisation such as a national day of mourning to recognise the trauma of those deaths. Such efforts should be made to incorporate such events in crises.

Consideration also must be given to ‘last responders’ involved in addressing infectious diseases outbreaks and natural crises, including pathologists, body collection teams, funeral directors and other mortuary workers. While frontline staff work to save lives, little is known about the experiences of those who care for the dead; they seem almost to be an ‘invisible group.’ Anecdotally and from media reports, it is apparent that there are significant challenges experienced ‘on the ground.’ Mortuary workers and funeral directors face stigmatisation and moral distress while being overwhelmed with dead bodies to manage.82 95 They have a duty of care to mourning families. The level of support given to those workers and the issues they have faced during the COVID-19 epidemic is unknown. This empirical gap needs to be addressed urgently.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, some deaths have been perceived as ‘bad deaths’.7 31 Many have died in isolation in hospital with no family or friends present due to safety restrictions; instead, they were accompanied by healthcare professionals, and so their deaths may not have been peaceful. Bereaved family members are reported to be suffering emotional uncertainty from an ambiguous loss, and this suffering is aggravated by the social isolation imposed by the COVID-19 restrictions.31 87 In addition, restrictive policies aimed at managing the spread of infections have changed burial procedures and, hence, impeded the grieving process. While the studies show that communities are flexible and willing to adapt to new regulations and funeral rites,5 96 the policies regulating burials should always be developed in consultation with religious leaders or be informed by local community members, and importantly they should demonstrate respect for religious beliefs and the family’s grief. Policymakers need to develop compassionate and sustainable ways of supporting bereaved family members as well as healthcare professionals and ‘last responders’. Furthermore, there need to be plans in place to ensure that patients do not die alone if restrictions prevent visits; technology, although not a perfect solution, may alleviate that challenge.

This scoping review highlights that caring for the dead also mirrors the injustices perpetrated on the living. Deprived or vulnerable populations are more likely to die in time of crisis. There is a clear link between a country’s lower socioeconomic status and greater numbers of deaths from natural disasters.55 People experiencing deprivation or vulnerable are more likely to remain uncounted and unidentified, thereby rendering their deaths invisible. The question of whose deaths count, and why they do or do not count, should be investigated. On national levels, policymakers need to identify inequalities in the application of policies regulating the management of the dead during pandemics or natural disasters. These efforts could be made in collaboration with researchers. As argued by Simpson et al7 in their study on ‘good’ and ‘bad’ deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK, the use of rapid ethnographic methods has proven efficient in making direct recommendations for policymaking. Finally, this review has identified a gap in the research on dead bodies in pandemics and natural disasters. Global and national policymakers and scholars need to make serious efforts to identify when such research is allowed or not allowed, under what circumstances and by whom.

Limitations

We have not excluded policy reports in our scoping. However, no policy reports were found on the COVID-19 pandemic, which is a limitation of this review. We only reviewed literature written in English, which is another limitation of this study.

Conclusions

The findings of this review have demonstrated that management of dead bodies in epidemics or natural disasters raises a wide range of ethical and sociocultural challenges. While practical issues with managing dead bodies have been discussed in the global health literature and the ethical and sociocultural facets of handling the dead have been recognised, they are nonetheless not given adequate attention. The results of this review implicate and inform the ethical aspect of the current management of dead bodies in the COVID-19 pandemic and will be valuable in pandemic and natural disasters preparedness strategies. There is an urgent need to address the knowledge gap pertaining to the ethical and practical issues with handling dead bodies. Without adequate attention to the arising socioethical issues around this process, it is likely to be mismanaged from the perspectives of the individual families, cultures and communities involved.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Marisha Wickremsinhe, Regis Wilson, Scholastica Zakayo and Karol Waniek for comments on earlier drafts of this paper. We also would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on the manuscript. We are grateful to Anna Suwalowska for creating the artwork accompanying the paper.

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

Contributors: HS and FA prepared the first draft of the manuscript, NR was involved in the study design and library searches, HS, FA and PK were involved in the study design and analysis of the data. HS is the guarantor of this paper responsible for the overall content of the manuscript.

Funding: This paper was supported with funding from the Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF) through UKRI/ESRC for the ‘RECAP’ project (ES/P010873/1).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

In this article, we use the term sociocultural challenges/implications/issues to mean challenges/implications/issues relating to or involving a combination of social and cultural factors, for example, religion, wealth and income disparities, age. We use the term ethical challenge/dilemma to mean any situation in which a difficult choice must be made between two courses of action, either of which entails transgressing a moral value

It was not appropriate or possible to involve patients or the public in the design, conduct, reporting or dissemination plans of our research.

Data availability statement

Data sharing not applicable as no datasets generated and/or analysed for this study.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1.AlJazeera . Tensions grow in quake-hit Haiti. as death toll tops 2,000, 2021. Available: https://www.aljazeera.com/gallery/2021/8/19/haiti-earthquake-deaths-aid-victims-les-cayes?utm_source=pocket_mylist

- 2.TheGuardian . 'Utter disaster': Manaus fills mass Graves as Covid-19 hits the Amazon, 2021. Available: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/30/brazil-manaus-coronavirus-mass-graves

- 3.Aljazeera . Non-stop cremations cast doubt on India’s counting of COVID dead, 2021. Available: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/4/20/non-stop-cremations-cast-doubt-on-indias-counting-of-covid-dead

- 4.AlJazeera . Bodies of dozens of suspected COVID dead found in India’s Ganges, 2012. Available: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/5/11/dozens-of-suspected-covid-victims-found-in-indias-ganges

- 5.Lipton J. ‘Black’ and ‘white’ death: burials in a time of Ebola in Freetown, Sierra Leone. J R Anthropol Inst 2017;23:801–19. 10.1111/1467-9655.12696 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghaffari-Nejad A, Ahmadi-Mousavi M, Gandomkar M, et al. The prevalence of complicated grief among Bam earthquake survivors in Iran. Arch Iran Med 2007;10:525. doi:07104/AIM.0019 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simpson N, Angland M, Bhogal JK, et al. 'Good' and 'Bad' deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic: insights from a rapid qualitative study. BMJ Glob Health 2021;6:e005509. 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-005509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morgan OW, Sribanditmongkol P, Perera C, et al. Mass fatality management following the South Asian tsunami disaster: case studies in Thailand, Indonesia, and Sri Lanka. PLoS Med 2006;3:e195. 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morgan O, de Ville de Goyet C, De Goyet CDV. Dispelling disaster myths about dead bodies and disease: the role of scientific evidence and the media. Rev Panam Salud Publica 2005;18:33–6. 10.1590/s1020-49892005000600006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woods S. Death duty – caring for the dead in the context of disaster. New Genet Soc 2014;33:333–47. 10.1080/14636778.2014.944260 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005;8:19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Armstrong R, Hall BJ, Doyle J, et al. ’Scoping the scope’ of a cochrane review. J Public Health 2011;33:147–50. 10.1093/pubmed/fdr015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peterson J, Pearce PF, Ferguson LA, et al. Understanding scoping reviews: definition, purpose, and process. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract 2017;29:12–16. 10.1002/2327-6924.12380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clarke V, Braun V. Thematic analysis. J Posit Psychol 2017;12:297–8. 10.1080/17439760.2016.1262613 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morgan O. Infectious disease risks from dead bodies following natural disasters. Rev Panam Salud Publica 2004;15:307–12. 10.1590/s1020-49892004000500004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ibrion M, Parsizadeh F, Naeini MP, et al. Handling of dead people after two large earthquake disasters in Iran: Tabas 1978 and Bam 2003 – Survivors’ perspectives, beliefs, funerary rituals, resilience and risk. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 2015;11:60–77. 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2014.11.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamada S, Gunatilake RP, Roytman TM, et al. The Sri Lanka tsunami experience. Disaster Manag Response 2006;4:38–48. 10.1016/j.dmr.2006.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McEntire D, Sadiq A-A, Gupta K. Unidentified bodies and Mass-Fatality management in Haiti: a case study of the January 2010 earthquake with a cross-cultural comparison. Int J Mass Emerg Disasters 2012;30:301–27. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perera C. After the tsunami: legal implications of mass burials of unidentified victims in Sri Lanka. PLoS Med 2005;2:e185. 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Entress R, Tyler J, Sadiq A-A. Managing mass fatalities during COVID-19: lessons for promoting community resilience during global pandemics. Public Adm Rev 2020;80:856–61. 10.1111/puar.13232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nuriddin A, Jalloh MF, Meyer E, et al. Trust, fear, stigma and disruptions: community perceptions and experiences during periods of low but ongoing transmission of Ebola virus disease in Sierra Leone, 2015. BMJ Glob Health 2018;3:e000410. 10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Walker A, Kennedy C, Taylor H, et al. Rethinking resistance: public health professionals on empathy and ethics in the 2014-2015 Ebola response in Sierra Leone and Liberia. Crit Public Health 2020;30:577–88. 10.1080/09581596.2019.1648763 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee-Kwan SH, DeLuca N, Bunnell R, et al. Facilitators and barriers to community acceptance of safe, Dignified medical Burials in the context of an Ebola epidemic, Sierra Leone, 2014. J Health Commun 2017;22:24–30. 10.1080/10810730.2016.1209601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ballera JE, de los Reyes VC, Sucaldito MN, et al. Management of the dead in Tacloban City after Typhoon Haiyan. Western Pac Surveill Response J 2015;6 Suppl 1:44. 10.5365/WPSAR.2015.6.2.HYN_004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alexander DA. Stress among police body handlers. A long-term follow-up. Br J Psychiatry 1993;163:806–8. 10.1192/bjp.163.6.806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCarroll JE, Ursano RJ, Ventis WL, et al. Anticipation of handling the dead: effects of gender and experience. Br J Clin Psychol 1993;32:466–8. 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1993.tb01082.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elliott A, Rehfisch N. Mortuary provision in emergencies causing mass fatalities. J Bus Contin Emer Plan 2011;5:430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leditschke J, Collett S, Ellen R. Mortuary operations in the aftermath of the 2009 Victorian bushfires. Forensic Sci Int 2011;205:8–14. 10.1016/j.forsciint.2010.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ellingham S, Cordner S, Tidball-Binz M. Revised practical guidance for first responders managing the dead after disasters. Int Rev Red Cross 2016;98:647–69. 10.1017/S1816383117000248 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perera C, Briggs C. Guidelines for the effective conduct of mass burials following mass disasters: post-Asian tsunami disaster experience in retrospect. Forensic Sci Med Pathol 2008;4:1–8. 10.1007/s12024-007-0026-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carr D, Boerner K, Moorman S. Bereavement in the time of coronavirus: unprecedented challenges demand novel interventions. J Aging Soc Policy 2020;32:425–31. 10.1080/08959420.2020.1764320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rohan RP, Hettiarachchi M, Vidanapathirana M, et al. Management of dead and missing: aftermath tsunami in Galle. Leg Med 2009;11 Suppl 1:S86–8. 10.1016/j.legalmed.2009.01.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stoney C, Scanlon J, Kramar K, et al. Steadily increasing control: the professionalization of mass death. J Contingencies Crisis Manag 2011;19:66–74. 10.1111/j.1468-5973.2011.00635.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scanlon J, McMahon T, van Haastert C. Handling mass death by integrating the management of disasters and pandemics: lessons from the Indian Ocean tsunami, the Spanish flu and other incidents. J Contingencies & Crisis Man 2007;15:80–94. 10.1111/j.1468-5973.2007.00511.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gershon RRM, Magda LA, Riley HEM, et al. Mass fatality preparedness in the death care sector. J Occup Environ Med 2011;53:1179. 10.1097/JOM.0b013e31822cfe76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kirkis EJ. A myth too tough to die: the dead of disasters cause epidemics of disease. Am J Infect Control 2006;34:331–4. 10.1016/j.ajic.2005.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ravi KS. Dead body management in times of Covid-19 and its potential impact on the availability of cadavers for medical education in India. Anat Sci Educ 2020;13:316–7. 10.1002/ase.1962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pandey A, Atkins KE, Medlock J, et al. Strategies for containing Ebola in West Africa. Science 2014;346:991. 10.1126/science.1260612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Robert A, Edmunds WJ, Watson CH, et al. Determinants of transmission risk during the late stage of the West African Ebola epidemic. Am J Epidemiol 2019;188:1319. 10.1093/aje/kwz090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hagan JE, Smith W, Pillai SK, et al. Implementation of Ebola case-finding using a village chieftaincy taskforce in a remote outbreak - Liberia, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015;64:183. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Waheed Y. Ebola in West Africa: an international medical emergency. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed 2014;4:673–4. 10.12980/APJTB.4.201414B389 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barbarossa MV, Dénes A, Kiss G, et al. Transmission dynamics and final epidemic size of Ebola virus disease outbreaks with varying interventions. PLoS One 2015;10:e0131398. 10.1371/journal.pone.0131398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rabaan AA, Al-Ahmed SH, Alsuliman SA, et al. The rise of pneumonic plague in Madagascar: current plague outbreak breaks usual seasonal mould. J Med Microbiol 2019;68:292–302. 10.1099/jmm.0.000915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gunnlaugsson G, Einarsdóttir J, Angulo FJ, et al. Funerals during the 1994 cholera epidemic in Guinea-Bissau, West Africa: the need for disinfection of bodies of persons dying of cholera. Epidemiol Infect 1998;120:7–15. 10.1017/s0950268897008170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Poleykett B. Ethnohistory and the dead: cultures of colonial epidemiology. Med Anthropol 2018;37:472–85. 10.1080/01459740.2018.1453507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ngwa MC, Young A, Liang S, et al. Cultural influences behind cholera transmission in the far North region, Republic of Cameroon: a field experience and implications for operational level planning of interventions. Pan Afr Med J 2017;28:311. 10.11604/pamj.2017.28.311.13860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sack RB, Siddique AK. Corpses and the spread of cholera. Lancet 1998;352:1570. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)61040-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Glass RI, Claeson M, Blake PA, et al. Cholera in Africa: lessons on transmission and control for Latin America. Lancet 1991;338:791. 10.1016/0140-6736(91)90673-d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Donovan GK, Ebola DGK. Ebola, epidemics, and ethics - what we have learned. Philos Ethics Humanit Med 2014;9:15. 10.1186/1747-5341-9-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brainard J, Hooper L, Pond K, et al. Risk factors for transmission of Ebola or Marburg virus disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol 2016;45:102–16. 10.1093/ije/dyv307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shultz JM, Cooper JL, Baingana F, et al. The role of Fear-Related behaviors in the 2013–2016 West Africa Ebola virus disease outbreak. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2016;18:1–14. 10.1007/s11920-016-0741-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moran MH. Missing bodies and secret funerals: the production of "safe and dignified burials" in the Liberian Ebola crisis/Corpos desaparecidos e funerais secretos: a producao de "enterros seguros e dignos" na crise Liberiana do Ebola Essay). Anthropol Q 2017;90:399. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sumathipala A, Siribaddana S, Perera C. Management of dead bodies as a component of psychosocial interventions after the tsunami: a view from Sri Lanka. Int Rev Psychiatry 2006;18:249–57. 10.1080/09540260600656100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Roy N. The Asian tsunami: PAHO disaster guidelines in action in India. Prehosp Disaster Med 2006;21:310. 10.1017/s1049023x00003939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cordner S, Ellingham STD. Two halves make a whole: both first responders and experts are needed for the management and identification of the dead in large disasters. Forensic Sci Int 2017;279:60–4. 10.1016/j.forsciint.2017.07.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hartman D, Drummer O, Eckhoff C, et al. The contribution of DNA to the disaster victim identification (DVI) effort. Forensic Sci Int 2011;205:52–8. 10.1016/j.forsciint.2010.09.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dyer O. Puerto Rico’s morgues full of uncounted bodies as hurricane death toll continues to rise. BMJ 2017;359. 10.1136/bmj.j4648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.O'Donnell C, Iino M, Mansharan K, et al. Contribution of postmortem multidetector CT scanning to identification of the deceased in a mass disaster: experience gained from the 2009 Victorian bushfires. Forensic Sci Int 2011;205:15–28. 10.1016/j.forsciint.2010.05.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fitrasanti BI, Syukriani YF. Social problems in disaster victim identification following the 2006 Pangandaran tsunami. Leg Med 2009;11 Suppl 1:S89–91. 10.1016/j.legalmed.2009.01.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.O'Mahony S. Mourning our dead in the covid-19 pandemic. BMJ 2020;369:m1649. 10.1136/bmj.m1649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mokuwa E, Richards P. How should public health Officials respond when important local rituals increase risk of contagion? AMA J Ethics 2020;22:E5-9. 10.1001/amajethics.2020.5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Marshall K, Smith S, Religion SS. Religion and Ebola: learning from experience. Lancet 2015;386:e24–5. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61082-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jalloh MF, Robinson SJ, Corker J, et al. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Related to Ebola Virus Disease at the End of a National Epidemic - Guinea, August 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66:1109. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6641a4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Adongo PB, Tabong PT-N, Asampong E, et al. Preparing towards preventing and containing an Ebola virus disease outbreak: what Socio-cultural practices may affect containment efforts in Ghana? PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2016;10:e0004852. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Omonzejele P. Current ethical and other problems in the practice of African traditional medicine. Med Law 2003;22:29–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Piot P, Muyembe J-J, Edmunds WJ. Ebola in West Africa: from disease outbreak to humanitarian crisis. Lancet Infect Dis 2014;14:1034. 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70956-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Asfaw Y, Boateng I, Calderon M, et al. Interagency technical consultation on improving mortality reporting in Sierra Leone: meeting report. Pan Afr Med J 2017;26. 10.11604/pamj.2017.26.27.11111 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tiffany A, Dalziel BD, Kagume Njenge H, et al. Estimating the number of secondary Ebola cases resulting from an unsafe burial and risk factors for transmission during the West Africa Ebola epidemic. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2017;11:e0005491. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cleaton JM, Viboud C, Simonsen L, et al. Characterizing Ebola transmission patterns based on Internet news reports. Clin Infect Dis 2016;62:24–31. 10.1093/cid/civ748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Curran KG, Gibson JJ, Marke D, et al. Cluster of Ebola Virus Disease Linked to a Single Funeral - Moyamba District, Sierra Leone, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65:202. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6508a2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Victory KR, Coronado F, Ifono SO, et al. Ebola transmission linked to a single traditional funeral ceremony - Kissidougou, Guinea, December, 2014-January 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015;64:386–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jalloh MF, Bunnell R, Robinson S, et al. Assessments of Ebola knowledge, attitudes and practices in Forécariah, guinea and Kambia, Sierra Leone, July-August 2015. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2017;372. 10.1098/rstb.2016.0304. [Epub ahead of print: 26 May 2017]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bhatnagar N, Grover M, Kotwal A, et al. Study of recent Ebola virus outbreak and lessons learned: a scoping study. Ann Trop Med Public Health 2016;9:145–51. 10.4103/1755-6783.181658 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Roshania R, Mallow M, Dunbar N, et al. Successful implementation of a multicountry clinical surveillance and data collection system for Ebola virus disease in West Africa: findings and lessons learned. Glob Health Sci Pract 2016;4:394–409. 10.9745/GHSP-D-16-00186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Stehling-Ariza T, Rosewell A, Moiba SA, et al. The impact of active surveillance and health education on an Ebola virus disease cluster - Kono District, Sierra Leone, 2014-2015. BMC Infect Dis 2016;16:611. 10.1186/s12879-016-1941-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.International Ebola Response Team, Agua-Agum J, Ariyarajah A, et al. Exposure patterns driving Ebola transmission in West Africa: a retrospective observational study. PLoS Med 2016;13:e1002170. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pellecchia U, Crestani R, Decroo T, et al. Social consequences of Ebola containment measures in Liberia. PLoS One 2015;10:e0143036. 10.1371/journal.pone.0143036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Roca A, Afolabi MO, Saidu Y, et al. Ebola: a holistic approach is required to achieve effective management and control. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015;135:856. 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.02.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nielsen CF, Kidd S, Sillah ARM, et al. Improving burial practices and cemetery management during an Ebola virus disease epidemic - Sierra Leone, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015;64:20–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Nyenswah TG, Kateh F, Bawo L, et al. Ebola and its control in Liberia, 2014-2015. Emerg Infect Dis 2016;22:169–77. 10.3201/eid2202.151456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Blair RA, Morse BS, Tsai LL. Public health and public trust: survey evidence from the Ebola virus disease epidemic in Liberia. Soc Sci Med 2017;172:89–97. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cordner S, Bouwer H, Tidball-Binz M. The Ebola epidemic in Liberia and managing the dead-A future role for humanitarian forensic action? Forensic Sci Int 2017;279:302–9. 10.1016/j.forsciint.2017.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Richards P, Amara J, Ferme MC, et al. Social pathways for Ebola virus disease in rural Sierra Leone, and some implications for containment. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2015;9:e0003567. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jaja IF, Anyanwu MU, Iwu Jaja C-J. Social distancing: how religion, culture and burial ceremony undermine the effort to curb COVID-19 in South Africa. Emerg Microbes Infect 2020;9:1077. 10.1080/22221751.2020.1769501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Jalloh MF, Sengeh P, Bunnell RE, et al. Evidence of behaviour change during an Ebola virus disease outbreak, Sierra Leone. Bull World Health Organ 2020;98:330–40. 10.2471/BLT.19.245803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gurley ES, Parveen S, Islam MS, et al. Family and community concerns about post-mortem needle biopsies in a Muslim Society. BMC Med Ethics 2011;12:10. 10.1186/1472-6939-12-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yardley S, Rolph M. Death and dying during the pandemic. BMJ 2020;369:m1472. 10.1136/bmj.m1472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Swain R, Sahoo J, Biswal SP, et al. Management of mass death in COVID-19 pandemic in an Indian perspective. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 2020:1–4. 10.1017/dmp.2020.399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Taniyama RY, Becker CB. Religious Care by Zen Buddhist Monks: A Response to Criticism of “Funeral Buddhism”. J Relig Spiritual Soc Work 2014;33:49–60. 10.1080/15426432.2014.873649 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Anderson M, Leditschke J, Bassed R, et al. Mortuary operations following mass fatality natural disasters: a review. Forensic Sci Med Pathol 2017;13:67–77. 10.1007/s12024-016-9836-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Woodruff BA. Interpreting mortality data in humanitarian emergencies. Lancet 2006;367:9–10. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67637-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kates OS, Fisher CE, Rakita RM, et al. Use of SARS-CoV-2-infected deceased organ donors: Should we always "just say no?". Am J Transplant 2020;20:1787–94. 10.1111/ajt.16000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Jones DG, Whitaker MI. Speaking for the dead : the human body in biology and medicine. 2 edn. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Logan W. Bushfire catastrophe in Victoria, Australia: public record, accountability, commemoration, memorialization and heritage protection. National Identities 2015;17:155–74. 10.1080/14608944.2015.1019207 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 95.AlJazeera . COVID ‘swallowing’ people in India as crematoriums overwhelmed, 2021. Available: https://www.aljazeera.com/gallery/2021/4/26/mass-funeral-pyres-reflect-indias-covid-crisis

- 96.Scott Bray R, Martin G. Exploring fatal facts: current issues in coronial law, policy and practice. Int J Law Context 2016;12:115–40. 10.1017/S1744552316000100 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjgh-2021-006345supp001.pdf (1.1MB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable as no datasets generated and/or analysed for this study.