Abstract

Background: Although proven effective interventions for childhood obesity exist, there remains a substantial gap in the adoption of recommended practices by clinicians.

Objective: The aims are to: (1) package implementation and training supports to facilitate the adoption of the evidence-based Healthy Weight Clinic Pediatric Weight Management Intervention (PWMI) (based on three previous effectiveness trials); (2) pilot and evaluate the packaged Healthy Weight Clinic PWMI; and (3) develop a sustainability and dissemination plan.

Design/Methods: We used the Consolidated Framework of Implementation Research constructs to create an Implementation Research Logic Model that defined the facilitators and barriers of the Healthy Weight Clinic PWMI. We linked these constructs to implementation strategies and mechanisms. Packaging and design will be informed by the core essential components and functions of the PWMI along with stakeholder engagement. Once the package is complete, we will pilot the PWMI by using a Type III effectiveness-implementation hybrid design. Implementation outcomes will be evaluated by using the RE-AIM framework.

Results: We will create an integrated, multisystems level package for national dissemination. The package will include training and a suite of resources for primary care physicians and healthy weight clinic staff, including: patient and caregiver facing videos, patient and caregiver handouts, group curriculum guide, online provider trainings, and access to a virtual learning collaborative.

Conclusion: The results will highlight the extent to which the package of the Healthy Weight Clinic PWMI facilitates the adoption of effective strategies for treating childhood obesity. Lessons learned will inform modifications to the Healthy Weight Clinic PWMI and strategies for future scaling.

Keywords: childhood obesity, implementation, primary care

Introduction

Childhood obesity is highly prevalent and disproportionately affects communities of color and low-income children. In the United States, ∼18.5% of children aged 2–19 years have obesity defined as a BMI at or above the age- and sex-specific 95th percentile, and 5.6% have severe obesity defined as a BMI at or above 120% of the 95th percentile.1 Although childhood obesity prevalence appears to have plateaued in some U.S. population subgroups from 2007 to 2016, overall rates remain at historically high levels and socioeconomic disparities appear to be widening with children of color bearing a disproportionate share of the burden.2–4 Between 2013 and 2016, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data indicate that compared with White youth, obesity and severe obesity prevalence were significantly higher among Black and Latinx youth and by household income.5,6

Substantial evidence also suggests that obesity and related behavioral risk factors such as poor diet quality, physical inactivity, and insufficient sleep are major drivers of diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and many cancers.7–12 The economic burden of obesity in the United States is staggering—annual direct medical costs of childhood obesity are estimated at $14.3 billion, whereas future economic burden includes an additional $45 billion of direct medical costs and $208 billion due to lost productivity when these children transition into adulthood.13–16

In June 2017, the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) updated their recommendations on the screening and management of obesity in children, indicating that clinicians screen children ≥6 years of age for obesity and offer them comprehensive, intensive behavioral interventions to improve weight status.17,18 In addition, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) developed integrated guidelines for cardiovascular health and risk reduction in children and recommended screening and management beginning at age 2 rather than age 6.19 The USPSTF review and NHLBI guidelines offer strong evidence that (1) screening and evaluation of children for obesity is an important prelude to effective treatment, (2) comprehensive treatment including counseling for weight management and healthful nutrition and physical activity is effective, and (3) behavioral management techniques to make and sustain lifestyle changes are important intervention components. In addition, there is a need for pediatric weight management for children with a BMI ≥85th percentile in primary care to prevent severe obesity and aid the overburdened tertiary care centers. Recognizing the need for an integrated approach to address the needs of pediatric weight management in primary care, the Healthy Weight Clinic Pediatric Weight Management Intervention (PWMI) combines elements from effective PWMIs into one comprehensive program serving children with a BMI ≥85th percentile.

Methods

Preliminary Work

The Healthy Weight Clinic PWMI will work to package elements of Connect for Health and a primary care based Healthy Weight Clinic intervention (based off the effectiveness trials: Mass in Motion Kids and Clinic and Community Approaches to Healthy Weight Trials both previously CDC-funded Childhood Obesity Research Demonstration projects).20–24 This package is a collaboration between the team at Mass General Hospital for Children (MGHfC) and the American Academy of Pediatrics Institute for Childhood Healthy Weight.

The Connect for Health trial examined the comparative effectiveness of two clinical-community interventions in improving child BMI z-scores and family-centered outcomes for childhood obesity. The study was a two-arm, randomized controlled trial.23 Participants were 721 children aged 2–12 years with BMI ≥85th percentile from six primary care practices in Massachusetts. Children were randomized to one of two arms: (1) Enhanced primary care, for example, flagging of children with BMI ≥85th percentile, clinical decision support tools for child weight management, caregiver educational materials, a neighborhood resource guide, and monthly text messages, or (2) Enhanced primary care plus contextually tailored, individual health coaching (twice-weekly text messages and telephone or video contacts every other month) and direct linkage of families to neighborhood resources. Both intervention arms demonstrated improved BMI z-scores and family-centered outcomes, and there was no significant difference between the two arms.20 BMI z-score outcomes at 2 years were assessed for sustainability of the interventions' effectiveness, with intervention effects on BMI z-score maintained in both groups.

The Mass in Motion Kids trial, similar to Connect for Health, implemented clinical decision support tools and caregiver educational materials, but in addition implemented a Healthy Weight Clinic, in two community health centers. The multidisciplinary Healthy Weight Clinics worked to reorganize care to provide access to a trained team consisting of a pediatric provider, nutritionist/dietitian, and community health worker during dedicated weight management visits. The Healthy Weight Clinic model improved pediatric weight management by promoting local specialization and increasing capacity for specialized care; building multidisciplinary teams within primary care; and focusing on health behavior change as a critical determinant of chronic disease outcomes. This model was found to be effective in reducing BMI z-score by −0.16 U/year (95% confidence interval [CI]: −0.21 to −0.12) compared with the comparison health center.21

The Clinic and Community Approaches to Healthy Weight trial was a nested randomized trial conducted in two federally qualified health centers and two regional YMCAs serving the same two communities in Massachusetts.25 Eligible children were 6 to 12 years old with a BMI ≥85th percentile, receiving primary care at the two health centers. Participants were randomized to either (1) a PWMI delivered in the Healthy Weight Clinics at the health center, or a (2) modified Healthy Weight and Your Child (M-HWYC) intervention delivered in YMCAs. Both PWMIs were 1 year in duration and offered at least 30 contact hours. Compared with children in eight demographically similar comparison health centers (n = 4037), children receiving care in the HWC (n = 191) had a −0.23 kg/m2 [95% CI: −0.36 to −0.10] decrease in BMI and a −1.03 [−1.61 to −0.45] %BMIp95 decrease over 1 year. There was no significant BMI effect among children in the M-HWYC (n = 197).25

The Healthy Weight Clinic PWMI package is designed to support adoption of the evidence-based Healthy Weight Clinic PWMI by community health centers serving low-income children. The Healthy Weight Clinic PWMI will be piloted and evaluated, and this will inform the development of a sustainability and dissemination plan to accelerate adoption and scale across our nation's health centers.

Study Overview and Framework

As previously mentioned, the aims for the Healthy Weight Clinic PWMI are threefold:

-

1.

Package the Healthy Weight Clinic evidence-based PWMI to support adoption by community health centers serving low-income children,

-

2.

Pilot and evaluate the packaged PWMI by using a Type III hybrid effectiveness-implementation design to test our implementation strategies and improvement in BMI over 1 year in two health centers in Mississippi.

-

3.

Develop a sustainability and dissemination plan to accelerate adoption and scale of the Healthy Weight Clinic PWMI across community health centers.

Our overall strategy will be guided by the Knowledge to Action Framework.26 We will define the Healthy Weight Clinic PWMI core components and functions and develop a package that supports quality delivery of those core components and functions. The package will include implementation supports and resources as well as training and technical assistance to facilitate operational elements of creating a Healthy Weight Clinic as well as quality care delivery to patients and families. The package will include virtual training as well as a suite of resources for primary care providers and the healthy weight clinic staff (nutritionist/dietitian and community health worker), including: patient and caregiver facing videos, patient and caregiver handouts, optional text messaging or social media campaign, group curriculum guide, online provider trainings, accompanied with real-time technical assistance, virtual learning collaborative, and structured quality improvement activities to facilitate practice changes and adoption. All patient and caregiver facing materials are available in English and Spanish.

Implementation Research Logic Model

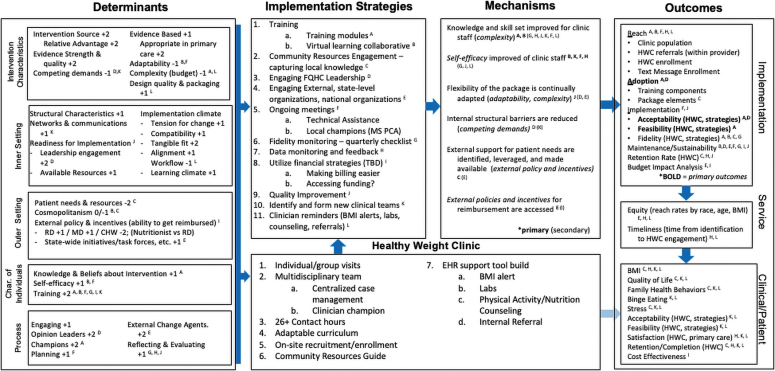

In an effort to guide the elements of implementation and evaluation of the Healthy Weight Clinic PWMI, and to specify the conceptual linkages between elements of this project, we developed an Implementation Research Logic Model.27 This exercise was used to improve understanding of the Healthy Weight Clinic PWMI among the research and implementation teams by clearly defining the facilitators and barriers of the implementation of the PWMI based on the Consolidated Framework of Implementation Research domains and constructs.28 We then linked these to specific implementation strategies and mechanisms that were used to inform the implementation supports included in the Healthy Weight Clinic PWMI (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Implementation Research Logic Model for the Healthy Weight Clinic pediatric weight Management Intervention. Superscript letters denote linkages between the determinants, strategies, mechanism, and outcomes. Superscript numbers denote the relative strength of the determinant based on the coding system of Damschroder and Lowery35 to gauge the relative strength of the determinant on the following scale: −2 (strong negative impact), −1 (weak negative impact), 0 (neutral or mixed influence), 1 (weak positive impact), and 2 (strong positive impact). Bold indicates primary outcomes.

Packaging and Design

A critical first step to the design of the Healthy Weight Clinic PWMI was to define the core components and functions and those that would be considered optional. Core functions are the defining components of Healthy Weight Clinic PWMI whose functionality may be met in varying forms. Perez Jolles et al. define core functions as the “purposes of the change process” that the PWMI facilitates, and the form as the “specific strategies or activities” for the local context.29 Table 1 maps the five core functions and their corresponding forms that can be adjusted according to the resources present within a participating health center.

Table 1.

Healthy Weight Clinic Pediatric Weight Management Intervention Functions and Forms

| Intervention functions and forms |

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Core function | Form | CFIR construct |

| Offer multidisciplinary team support for children with overweight or obesity in the context of primary care that offers nutritional assessment, behavioral change counseling, goal setting, medical management and tracking of BMI, and linkage to community resources | Clinician, nutritionist/Registered Dietitian, Community Health Worker Offered in-person, virtual, telephone support |

Inner Setting—Networks and communications Characteristics of individuals—Training |

| Ensure the child receives at least 26 contact hours of treatment consistent with the USPSTF recommendations | Individual and group visit curriculums Healthy lifestyle and wellness counseling, including: physical activity counseling, nutrition counseling, and mindfulness |

Intervention characteristics—Evidence strength and quality |

| Coordinating care in the community and eliminating barriers to achieving a healthy lifestyle |

Healthy Weight Clinic staff facilitates connections to community resources Addressing unmet social needs Phone contact in between visits to ensure families have access to the resources they need |

Outer setting—Patient needs and resources and cosmopolitanism |

| Creating infrastructure for providers on how to identify, counsel, and refer a child with overweight/obesity | Electronic Health Record Clinical Decision Support tool to: (1) identify children with overweight or obesity, (2) Order recommended labs, (3) Provide healthy lifestyle counseling, and (4) Make appropriate referrals and follow-up Workflow modifications |

Inner setting, implementation climate, workflow |

| Reinforcement of healthy lifestyle outside of clinic | Direct to patient family messaging campaign around healthy lifestyle changes Phone contact in between visits to check in on barriers and facilitators for healthy lifestyle change |

Outer setting—Patient needs and resources |

CFIR, Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research; USPSTF, United States Preventive Services Task Force.

To better inform the package development, a broad group of 53 stakeholders, including primary care physicians, chief medical officers of health centers providing care to children, public and private insurance representatives, representatives from national organizations such as the American Academy of Pediatrics, the National Association of Community Health Centers, and state organizations such as leaders in the Mississippi Primary Care Association, previous implementers of the primary care based Healthy Weight Clinics and staff from our pilot community health centers, including community health center leadership, community stakeholders, and clinical teams, have been engaged informally in interviews to advise on the feasibility, sustainability, and community resources to inform the package design and relative adaptions to better suit the clinic and patient population. Identification of key facilitators and barriers to successful implementation through informal interviews as experienced by these stakeholders providing care for low-income children have informed the design of package components.

Pilot Community Health Centers

Once the first iteration of the full package of the Healthy Weight Clinic PWMI is complete, we will pilot the Healthy Weight Clinic PWMI at two health centers in rural Mississippi by using a Type III effectiveness-implementation hybrid design (primary aim focused on implementation, secondary aim on effectiveness of the intervention).30 Mississippi ranks third in the nation for prevalence of overweight and obesity with a combined prevalence of childhood overweight and obesity equal to 37% (vs. the national average of 31.2%) among 10–17-year olds.31 Previous research has also shown that obesity prevalence is higher among children living in rural versus urban areas.32,33 Thus, efforts to prevent and manage obesity in the South, in non-metropolitan, rural areas could help reduce existing disparities in obesity prevalence found across geographic regions of the United States, by socioeconomic status, and by urbanization. The pilot will target children aged 2–18 years with a BMI ≥85th percentile who receive their primary care at one of the two health centers and their caregivers.

Training at these community health centers before recruitment will engage not only the Healthy Weight Clinic implementation staff, but also local and state-level champions to ensure sustainability of the program after piloting. Technical assistance will be available to the community health centers throughout the duration of the pilot study, and the MGHfC and AAP research and implementation team will maintain communication and engagement throughout the study. Evaluation of the pilot outcomes will use the RE-AIM framework34 and will inform further development of the Healthy Weight Clinic PWMI. Our primary effectiveness outcomes will be a change in percentage of the 95th percentile (%BMIp95) and a change in the BMI of children enrolled in the Healthy Weight Clinic at the intervention health centers compared with children from several demographically similar health centers in Mississippi. We will receive age, sex, height, weight, and BMI data from all health care visits in the electronic health care record from each implementation health center and from the comparison health centers. We will request heights, weights, and BMI from children across all sites, including all that are available 1–2 years before implementation and during the implementation period. To enable adjustment for differences between the implementation and comparison health centers, we will also receive sociodemographic data including age, sex, race, and ethnicity from all sites.

We plan to examine changes in BMI and %BMIp95 and compare changes among the intervention health centers with the comparison health centers. To assess changes per year in BMI and %BMIp95, we will use indicator variables for time and intervention arm (Healthy Weight Clinic or comparison site). We will perform an intention to treat analysis for children enrolled in the interventions. We will use the MIXED procedure in SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) to fit mixed linear regression models with random intercepts and slopes. The models will account for clustering of observations within individuals and within sites.

Sustainability and Dissemination Plan

While piloting in Mississippi, we will continue to convene quarterly with key stakeholders and advisory groups to develop (1) a dissemination strategy related to findings of this research study, (2) a scaling strategy for the PWMI package itself, as well as (3) a sustainability plan. Anticipated future target audiences for the Healthy Weight Clinic PWMI package include health centers that provide care to pediatric populations. We will continue to engage with our key stakeholders, including partnering with foundations, payers, and national organizations such as professional associations to understand critical actionable strategies for dissemination, scaling, and developing a plan to ensure sustainable funding.

Discussion

The Healthy Weight Clinic PWMI creates an integrated, multisystems level approach for pediatric weight management housed in primary care. The significance of the Healthy Weight Clinic PWMI lies in its implications for childhood obesity and chronic disease outcomes by providing sound approaches that are not only feasible, but also informed by robust conceptual frameworks to guide and better understand implementation and intervention delivery. Further, the Healthy Weight Clinic PWMI is built on innovations that are proven effective in similar settings and have demonstrated improved health outcomes, including reduction in BMI and improvement in quality of life and health behaviors for those disproportionately impacted by the disease. Evaluation of the Healthy Weight Clinic PWMI through the proposed primary care pilot study in two community health centers will inform improvements on the Healthy Weight Clinic PWMI for wide-scale dissemination. Given that the prevalence of obesity is beyond tertiary care capacity, having treatment options in primary care and community health centers is extremely important to ensure all children have access to evidence-based treatment.

As with all studies, the Healthy Weight Clinic PWMI has its limitations. The multilevel nature of the PWMI requires participation and buy-in from all levels of the health care system to ensure success, thus the process for such a complex implementation effort may prove to be difficult at scale. In addition, previous limitations of the sustainability of the Healthy Weight Clinic PWMI include the process for securing funds for community health workers and nutritionists/dietitians, including variable reimbursement for these roles from state to state. Without reimbursement policies on the federal level for these critical team members, this package could be limited in its dissemination. Finally, there is heterogeneity in the patients that this program serves by both weight status (overweight, obesity, and severe obesity) and age (2–18 years); however, the individual visits with the health care team allows for tailoring to the individual family, and we and our clinical partners felt that having a primary care solution for all children was important. However, given these limitations, the Healthy Weight Clinic PWMI creates a comprehensive PWMI that can effectively improve health outcomes in primary care.

Conclusion

The Healthy Weight Clinic PWMI is a comprehensive program that combines multidisciplinary team support, increases treatment contact hours, coordinates care within the community by eliminating barriers for patients and their families, and creates infrastructure for primary care providers to better care for their patients with childhood overweight and obesity. Through this project, we will demonstrate the ability to effectively implement the Healthy Weight Clinic PWMI in a new rural setting with more robust implementation support, which we believe will, in turn, improve the health status of children with obesity, allowing for broader adoption and spread of this evidence-based Healthy Weight Clinic PWMI to other health centers.

Disclaimer

The contents are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of, nor an endorsement, by CDC/HHS, or the US Government.

Funding Information

This publication is supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention of the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) as part of a financial assistance award (U18DP006424). Dr. Fiechtner is supported by grant number K23HD090222 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Dr. Taveras is supported by grant K24 DK105989 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1. Hales CM, Fryar CD, Carroll MD, et al. Trends in obesity and severe obesity prevalence in US youth and adults by sex and age, 2007-2008 to 2015-2016. JAMA 2018;319:1723–1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rossen LM, Schoendorf KC. Measuring health disparities: Trends in racial-ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in obesity among 2- to 18-year old youth in the United States, 2001-2010. Ann Epidemiol 2012;22:698–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Olds T, Maher C, Zumin S, et al. Evidence that the prevalence of childhood overweight is plateauing: Data from nine countries. Int J Pediatr Obes 2011;6:342–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wang YC, Gortmaker SL, Taveras EM. Trends and racial/ethnic disparities in severe obesity among US children and adolescents, 1976-2006. Int J Pediatr Obes 2011;6:12–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ogden CL, Fryar CD, Hales CM, et al. Differences in obesity prevalence by demographics and urbanization in us children and adolescents, 2013-2016. JAMA 2018;319:2410–2418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Fakhouri TH, et al. Prevalence of obesity among youths by household income and education level of head of household—United States 2011-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67:186–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. The US Burden of Disease Collaborators. The State of US Health, 1990-2016: Burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors among US States. JAMA 2018;319:1444–1472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Massetti GM, Dietz WH, Richardson LC. Excessive weight gain, obesity, and cancer: Opportunities for clinical intervention. JAMA 2017;318:1975–1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Freedman DS, Khan LK, Dietz WH, et al. Relationship of childhood obesity to coronary heart disease risk factors in adulthood: The Bogalusa Heart Study. Pediatrics 2001;108:712–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. McGill HC Jr, McMahan CA. Determinants of atherosclerosis in the young. Pathobiological Determinants of Atherosclerosis in Youth (PDAY) Research Group. Am J Cardiol 1998;82(10B):30–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Buscot MJ, Thomson RJ, Juonala M, et al. BMI trajectories associated with resolution of elevated youth BMI and incident adult obesity. Pediatrics 2018;141:e20172003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ward ZJ, Long MW, Resch SC, et al. Simulation of growth trajectories of childhood obesity into adulthood. N Engl J Med 2017;377:2145–2153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hammond RA, Levine R. The economic impact of obesity in the United States. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes 2010;3:285–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Finkelstein EA, Trogdon JG, Cohen JW, Dietz W. Annual medical spending attributable to obesity: Payer- and service-specific estimates. Health Aff Millwood 2009;28:W822-W831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Finkelstein EA, Graham WC, Malhotra R. Lifetime direct medical costs of childhood obesity. Pediatrics 2014;133:854–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lightwood J, Bibbins-Domingo K, Coxson P, et al. Forecasting the future economic burden of current adolescent overweight: An estimate of the coronary heart disease policy model. Am J Public Health 2009;99:2230–2237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. O'Connor EA, Evans CV, Burda BU, et al. Screening for obesity and intervention for weight management in children and adolescents: Evidence report and systematic review for the US preventive services task force. JAMA 2017;317:2427–2444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. US Preventive Services Task Force, Grossman DC, Bibbins-Domingo K, et al. Screening for obesity in children and adolescents: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA 2017;317:2417–2426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Expert panel on integrated guidelines for cardiovascular health and risk reduction in children and adolescents. NIH publication 12-7486. (Published October 2012). Available at https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/files/docs/peds_guidelines_sum.pdf Last accessed October 11, 2020.

- 20. Taveras EM, Marshall R, Sharifi M, et al. Comparative effectiveness of clinical-community childhood obesity interventions: A randomized clinical trial. [2017;171:814]. JAMA Pediatr 2017;171:e171325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Taveras EM, Perkins M, Anand S, et al. Clinical effectiveness of the Massachusetts childhood obesity research demonstration initiative among low-income children. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2017;25:1159–1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fiechtner L, Perkins M, Biggs V, et al. Rationale and design of the Clinic and Community Approaches to Healthy Weight Randomized Trial. Contemp Clin Trials 2018;67:16–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Taveras EM, Marshall R, Sharifi M, et al. Connect for health: Design of a clinical-community childhood obesity intervention testing best practices of positive outliers. Contemp Clin Trials 2015;45(Pt B):287–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Taveras EM, Marshall R, Sharifi M, et al. Design of the Massachusetts Childhood Obesity Research Demonstration (MA-CORD) study. Child Obes 2015;11:11–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fiechtner L, Perkins M, Biggs V, et al. Comparative effectiveness of clinical and community-based approaches to healthy weight. Pediatrics 2021:e2021050405. [Epub ahead of print]; DOI: 10.1542/peds.2021-050405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Applying the Knowledge to Action (K2A) Framework: Questions to Guide Planning. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Dept of Health and Human Services, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Smith JD, Li D, Rafferty MR. The Implementation Research Logic Model: A method for planning, executing, reporting, and synthesizing implementation projects. Implement Sci 2020;15:84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, et al. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci 2009;4:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Perez Jolles M, Lengnick-Hall R, Mittman BS. Core Functions and Forms of Complex Health Interventions: A Patient-Centered Medical Home Illustration [published correction appears in J Gen Intern Med. 2019 Apr 1]. J Gen Intern Med 2019;34:1032–1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B, et al. Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: Combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Med Care 2012;50:217–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative. Fast Facts: 2018-2019 National Survey of Children's Health. Data Resource Center for Child and Adolescent Health supported by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), Maternal and Child Health Bureau (MCHB). Available at www.childhealthdata.org Last accessed July 1, 2021.

- 32. Probst JC, Barker JC, Enders A, Gardiner P. Current state of child health in rural America: How context shapes children's health. J Rural Health 2018;34 (suppl 1):3–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Johnson JA III, Johnson AM. Urban-rural differences in childhood and adolescent obesity in the United States: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Obes 2015;11:233–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Glasgow RE, Harden SM, Gaglio B, et al. RE-AIM Planning and Evaluation Framework: Adapting to new science and practice with a 20-year review [Mini review]. Front Public Health 2019;7:64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Damschroder LJ, Lowery JC. Evaluation of a large-scale weight management program using the consolidated framework for implementation research (CFIR). Implement Sci 2013;8:1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]