Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate aerobic exercise capacity in 5-year intensive care unit (ICU) survivors and to assess the association between severity of organ failure in ICU and exercise capacity up to 5-year follow-up.

Methods

Secondary analysis of the EPaNIC follow-up cohort (NCT00512122) including 433 patients screened with cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET) between 1 and 5 years following ICU admission. Exercise capacity in 5-year ICU survivors (N = 361) was referenced to a historic sedentary population and further compared to demographically matched controls (N = 49). In 5-year ICU survivors performing a maximal CPET (respiratory exchange ratio > 1.05, N = 313), abnormal exercise capacity was defined as peak oxygen consumption (VO2peak) < 85% of predicted peak oxygen consumption (%predVO2peak), based on the historic sedentary population. Exercise liming factors were identified. To study the association between severity of organ failure, quantified as the maximal Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score during ICU-stay (SOFA-max), and exercise capacity as assessed with VO2peak, a linear mixed model was built, adjusting for predefined confounders and including all follow-up CPET studies.

Results

Exercise capacity was abnormal in 118/313 (37.7%) 5-year survivors versus 1/48 (2.1%) controls with a maximal CPET, p < 0.001. Aerobic exercise capacity was lower in 5-year survivors than in controls (VO2peak: 24.0 ± 9.7 ml/min/kg versus 31.7 ± 8.4 ml/min/kg, p < 0.001; %predVO2peak: 94% ± 31% versus 123% ± 25%, p < 0.001). Muscular limitation frequently contributed to impaired exercise capacity at 5-year [71/118 (60.2%)]. SOFA-max independently associated with VO2peak throughout follow-up.

Conclusions

Critical illness survivors often display abnormal aerobic exercise capacity, frequently involving muscular limitation. Severity of organ failure throughout the ICU stay independently associates with these impairments.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00134-021-06541-9.

Keywords: Exercise testing, Exercise tolerance, Critical illness, Organ failure

Take-home message

| Critical illness survivors often display abnormal aerobic exercise capacity, frequently involving muscular limitation. Severity of organ failure throughout the ICU stay independently associates with these impairments. |

Introduction

The impact of severe illness requiring admission to an intensive care unit (ICU) extends long beyond the ICU stay. Survivors of critical illness frequently report exercise intolerance and demonstrate reduced strength and six-minute-walk-distance as compared to healthy controls, features paralleled with reduced quality-of-life [1–6]. The post-ICU trajectories of patients may vary strongly [4, 5, 7, 8], but long-term physical impairments have been frequently attributed to illness severity [1, 4, 5]. However, static evaluations of strength and physical function incompletely capture physical fitness, which is a highly dynamic state [9]. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET) allows assessment of the integrated physiological exercise response, thereby better reflecting peak exercise capacity and functional performance in daily life [10, 11]. CPET, furthermore, allows distinction between cardiorespiratory and muscular impairments primarily limiting exercise [12]. Yet, data on aerobic exercise capacity in ICU survivors are limited to 3 case series, reporting limitations up to 3 months post-ICU [13–15], mainly due to deconditioning and muscle weakness. Evaluation of cardiorespiratory fitness is nonetheless relevant as it informs on long-term prognosis [16–20]. Furthermore, CPET-guided rehabilitation could benefit ICU-survivors, similar to other populations suffering from muscular impairments [21–26], as small increments in exercise capacity entail clinically relevant health benefits [27, 28].

Here, we aimed to investigate cardiorespiratory fitness in long-term survivors of critical illness through CPET. We hypothesized that 5-year survivors of critical illness have impaired aerobic exercise capacity as benchmarked to a sedentary reference population, and further compared to demographically matched healthy controls. We further hypothesized that in these patients, a muscular component frequently contributes to exercise limitation. Finally, we hypothesized that impaired aerobic exercise capacity in ICU survivors independently associates with organ failure severity during critical illness.

Methods

Ethics

The protocol of EPaNIC and its long-term follow-up were approved by the Ethical Committee Research UZ/KU Leuven (ML4190). All patients gave informed consent.

Study design and participants

This is a secondary analysis of the prospective follow-up study of the EPaNIC trial (Clinicaltrials.gov: NCT00512122) in which we included patients assessed for cardiorespiratory fitness by cardiopulmonary exercise testing between 1 and 5 years post-inclusion in EPaNIC. All long-stayers (ICU stay ≥ 8 days), and a random set of short-stayers (ICU stay < 8 days) were invited after 5 years, in the absence of exclusion criteria [29]. A number of patients were additionally invited at intermediate time points according to residual time-slot availability, prioritizing long-stayers. In patients attending the hospital, exercise capacity was assessed with CPET. The primary analysis of this study focused on the prevalence of abnormal exercise capacity in 5-year survivors, referenced to a published historical cohort [30]. Further comparisons were made with CPET results of 49 controls who never stayed in the ICU and who were selected to demographically match the 5-year post-EPaNIC cohort. The secondary analysis examined the association between in-ICU severity of organ failure and exercise capacity from 1 to 5 years post-EPaNIC. See online supplement for further details.

Cardiopulmonary exercise testing

An incremental, symptom-limited CPET was performed on an electrically braked cycle-ergometer (eBIKE, GE, provided by Acertys). Safety criteria for immediate termination were predefined [12, 31]. The test was performed under continuous monitoring of heart rate, transcutaneous oxygen saturation, and 12-lead electrocardiography. Blood pressure was measured at rest and then every 2 min. Oxygen consumption, carbon dioxide production and minute ventilation were measured on a breath-by-breath basis (JAEGER® Oxycon Pro® and Vyntus CPX® metabolic carts [32], CareFusion). See online supplement for further details.

Main CPET parameters

The main exercise parameters derived, were obtained at two pivotal points: (1) peak exercise, corresponding to the highest work rate achieved and maintained for 30 s; and (2) the anaerobic threshold, the point during exercise supposedly marking the onset of anaerobic metabolism [12].

At peak exercise, we obtained (a) peak oxygen consumption rate (VO2peak) as index of cardiorespiratory fitness [12, 18]; (b) peak work rate; (c) peak heart rate (HRpeak), and heart rate reserve (HRR); (d) peak ventilation (VEpeak), and ventilatory reserve, the ratio of VEpeak to maximal voluntary ventilation (MVV); (e) peak oxygen pulse (O2-pulse); (f) respiratory exchange ratio (RER), calculated as VCO2peak/VO2peak.

(g) The anaerobic threshold is generally referenced to the VO2 at which CO2-production exceeds O2-consumption due to lactic acid buffering (VO2AT); (h) additionally, we determined the ratio of ventilation rate to CO2-production rate at the anaerobic threshold (VE/VCO2AT) or ventilatory efficiency [33].

(i) In addition to estimates at peak exercise and at the anaerobic threshold, the metabolic efficacy for mechanical work, reflected by ΔVO2/ΔWR, was calculated.

Predicted values were based on reference equations from a historic sedentary benchmark population published by Jones et al. [30]. See online supplement for further details.

Categorising CPET outcomes

The main goal of the classification of the CPET studies was to identify patients in whom abnormal aerobic exercise capacity was primarily due to peripheral limitations, presumably due to muscular impairments or deconditioning, further referred to as muscular limitations. To avoid erroneous labelling of patients delivering insufficient effort, we first excluded patients with submaximal CPET. Maximal effort was defined as RER > 1.05 [9]. Next, we identified patients with abnormal exercise capacity, defined as VO2peak < 85% of predicted VO2peak [12, 34]. We subsequently identified patients with ventilator and gas exchange limitations and those in whom signs of cardiac disease were present. Patients without a clear indication of such pathological exercise responses were considered to predominantly exhibit muscular limitation. See online supplement for further details.

Severity of organ failure

Severity of organ dysfunction was quantified as the maximal Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA-max) score during ICU stay, ranging from 0 to 24, with higher values indicating more severe organ failure [35, 36].

Other outcomes

At follow-up, patients also underwent pulmonary function testing, evaluation of peripheral and respiratory strength, functional exercise capacity as assessed with the 6-min-walk-distance (6MWD), and quality-of-life assessment with the SF-36 [6, 8]. See online supplement for further details.

Statistics

The primary outcome was evaluation of exercise capacity and prevalence of abnormal exercise capacity in 5-year survivors, as referenced to a historical sedentary population [30]. Data were further compared with demographically matched healthy controls. Secondary outcomes included description of exercise limiting factors and the association between the severity of organ dysfunction and exercise capacity in ICU survivors. Descriptive analyses are provided in the online supplement.

Association between aerobic exercise capacity and severity of organ failure

To assess whether long-term aerobic exercise limitation was independently associated with severity of organ dysfunction throughout follow-up, data from all CPET studies between 1- and 5-year follow-up used and we created an adjusted linear mixed model for VO2peak. Fixed effects included the SOFA-max, time-to-follow-up in years, the interaction between SOFA-max and time, as well as a priori identified confounders, including: age and BMI at ICU admission, gender, diabetes mellitus at ICU admission, malignancy, preadmission dialysis, randomisation, diagnostic category, sepsis upon admission, and ICU-length-of stay [37]. The correlation within the repeated measures over time was modelled through an unstructured covariance matrix [38, 39]). Details are provided in the online supplement.

Exploratory analyses

If an independent effect of the severity of organ failure on VO2peak was demonstrated, we further examined whether the effect of severity of organ failure could be explained by persisting weakness. For this purpose, we built additional linear mixed models in which both knee and hip strength at follow-up were added as covariates in separate models.

Descriptive analyses were conducted with SPSS version 27 (IBM), linear mixed modelling with the MIXED procedure in SAS version 9.4 (SAS institute).

Results

Participants

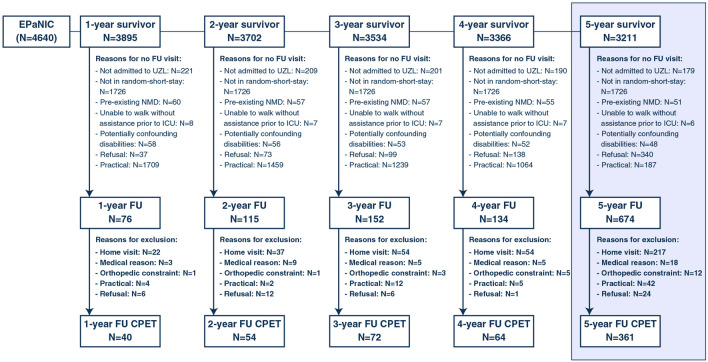

Throughout the 5-year period, 1151 follow-up visits were performed in 774 unique patients. CPET was performed during 591 follow-up visits (40/76 visits at 1-year, 54/115 at 2-year, 72/152 at 3-year, 64/134 at 4-year and 361/674 at 5-year), involving 433 unique patients. Reasons for not performing CPET are provided in Fig. 1. Characteristics of enrolled and non-enrolled 5-year follow-up patients are depicted in Table 1. Follow-up patients who performed a CPET were significantly younger, more frequently were male, had fewer comorbidities, received vasopressors less frequently and for shorter periods of time, less frequently acquired a new infection and had shorter ICU stays as compared to patients who did not perform a CPET. Mean time to follow-up was 5.5 ± 0.2 years. In parallel, 49 controls were tested with similar demographics as the 5-year cohort (Supplementary Table 1). Characteristics of the cohorts at intermediate time points are provided in Supplementary Table 2.

Fig. 1.

Patient flow chart and reasons for not performing CPET during the 5-year follow-up period. EPaNIC: Early Parenteral Nutrition in Intensive Care, CPET cardiopulmonary exercise testing, FU, follow-up

Table 1.

Admission and ICU-characteristics of patients evaluated at 5-year follow-up

| CPET (N = 361) | No CPET (N = 313) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Admission | |||

| Agea | 59 ± 14 | 68 ± 15 | < 0.001 |

| Gender, male | 254 (70.4) | 196 (62.6) | 0.003 |

| BMIa | 27.5 ± 4.7 | 26.8 ± 5 | 0.056 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 40 (11.1) | 58 (18.6) | 0.006 |

| Malignancy | 47 (13) | 59 (18.9) | 0.036 |

| Preadmission dialysis | 3 (0.8) | 0 (0) | 0.253 |

| Diagnostic category | 0.131 | ||

| Cardiac surgery | 146 (40.4) | 154 (49.4) | |

| Emergency SICU | 164 (45.4) | 119 (38.1) | |

| Elective SICU | 26 (7.2) | 18 (5.8) | |

| Medical ICU | 25 (6.9) | 21 (6.7) | |

| Randomisation, late PN | 181 (50.1) | 163 (52.2) | |

| APACHE II | 26 (16–33) | 24 (17–34) | 0.543 |

| Sepsis upon admission | 88 (24.4) | 88 (28.2) | 0.260 |

| ICU stay | |||

| Mechanical ventilation | 351 (97.2) | 298 (95.5) | 0.231 |

| Duration of mechanical ventilation, days | 3 (1–8) | 3 (2–9) | 0.190 |

| Vasopressors/inotropics | 291 (80.6) | 269 (86.2) | 0.052 |

| Duration of HD support, days | 2 (1–5) | 3 (2–9) | < 0.001 |

| New infection | 110 (30.5) | 120 (38.5) | 0.029 |

| New dialysis | 26 (7.2) | 31 (9.9) | 0.204 |

| Bilirubin > 3 mg/dL | 64 (17.8) | 56 (17.9) | 0.954 |

| ICU LOS, daysb | 5 (2–12) | 7 (3–14) | 0.001 |

| ICU-stay > 8 days | 136 (37.7) | 140 (44.9) | 0.058 |

Continuous variables are depicted as mean (standard deviation)a or median (interquartile range)b, categorical variables are depicted as number (percentages)

ICU intensive care unit, CPET cardiopulmonary exercise test, BMI body mass index, SICU surgical intensive care unit, PN parenteral nutrition, APACHE II acute physiology and chronic health evaluation, HD hemodynamic, LOS length of stay

Cardiopulmonary exercise capacity in 5-year survivors

At 5 years follow-up, 313/361 (86.7%) patients performed a maximal test, of which 118 (37.7%) revealed impaired aerobic exercise capacity. This was significantly different from controls, in whom 48/49 (98.0%) performed a maximal test, of which 1/48 (2.1%) exhibited abnormal aerobic exercise capacity (p < 0.001). VO2peak was significantly lower in 5-year follow-up patients as compared to controls (VO2peak: 24.0 ± 9.7 ml/min/kg versus 31.7 ± 8.4 ml/min/kg, p < 0.001; %predVO2peak: 94 ± 31% versus 123% ± 25%, p < 0.001) (Fig. 2; Table 2). The anaerobic threshold was identified in 331/361 (92%) patients at 5-year follow-up and values were significantly lower as compared to the healthy controls (VO2AT: 15.3 ± 8.7 ml/min/kg versus 18.5 ± 6.0 ml/min/kg, p = 0.015; % predicted VO2peak: 55% ± 16% versus 71% ± 21%, p < 0.001). Other CPET results are shown in Table 2 and Supplementary Table 3.

Fig. 2.

Key outcomes of cardiopulmonary exercise testing in the post-EPaNIC 5-year follow-up cohort and controls, depicted as mean and standard deviation. A VO2peak in ml/kg/min and as percentage predicted of VO2peak; B VO2AT in ml/kg/min and as percentage predicted of VO2peak. Comparisons were performed with t test. VO2peak: peak oxygen consumption rate; VO2AT: oxygen consumption rate at the anaerobic threshold

Table 2.

Selected outcomes of cardiopulmonary exercise testing in the post-EPaNIC 5-year follow-up cohort and controls

| EPANIC 5-year follow-up | Controls | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CPET—peak exercise | N = 361 | N = 49 | |

| VO2peak (ml/min/kg) | 24.0 ± 9.7 | 31.7 ± 8.4 | < 0.001 |

| VO2peak (%pred) | 94 ± 31 | 123 ± 25 | < 0.001 |

| Work rate (Watt) | 126 ± 53 | 180 ± 56 | < 0.001 |

| Work rate (%pred) | 81 ± 26 | 112 ± 29 | < 0.001 |

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 128 ± 29 | 150 ± 21 | < 0.001 |

| Heart rate (%pred HRmax) | 80 ± 15 | 95 ± 12 | < 0.001 |

| Heart rate reserve | 31 ± 24 | 7 ± 20 | < 0.001 |

| O2-pulse (ml/beat) | 14.8 ± 4.8a | 17.1 ± 4.6 | 0.001 |

| O2-pulse (%pred) | 110 ± 31a | 118 ± 23 | 0.068 |

| SpO2 (%) | 95 ± 2b | 96 ± 2 | 0.574 |

| VEpeak (L/min) | 67.3 ± 27.2 | 85.2 ± 23.4 | < 0.001 |

| Ventilatory reserve (VEpeak/MVV) | 64 ± 18c | 66 ± 15 | 0.370 |

| RER | 1.17 ± 0.11 | 1.21 ± 0.09 | 0.025 |

| ΔVO2/ΔWR (ml/W/min) | 13.4 ± 5.1d | 13.6 ± 2.5e | 0.955 |

| CPET—anaerobic threshold | N = 331 | N = 49 | |

| VO2AT (ml/min/kg) | 15.3 ± 8.7 | 18.5 ± 6 | 0.015 |

| VO2AT (%pred of VO2peak) | 55 ± 16 | 71 ± 21 | < 0.001 |

| VE/VCO2AT | 31 ± 17.3 | 27.6 ± 3.4 | < 0.001 |

Continuous variables are depicted as mean (± standard deviation), categorical variables are depicted as number (percentages). Measurement available in aN = 357, bN = 338, cN = 355, dN = 345, eN = 21

CPET cardiopulmonary exercise testing, HR heart rate, VE ventilation, VO2 oxygen consumption rate, AT anaerobic threshold, VCO2 carbon dioxide production rate, RER respiratory exchange ratio, O2-pulse oxygen pulse, VE/VCO2AT ratio of ventilation to CO2-production at the anaerobic threshold, ΔVO2/ΔWR: metabolic efficiency, calculated as (VO2peak−VO2baseline)/peak work rate, MVV maximum voluntary ventilation

Factors limiting cardiopulmonary exercise capacity in 5-year survivors

In 5-year follow-up patients exhibiting abnormal exercise capacity, the anaerobic threshold was abnormal in 78/118 (66.1%), undetermined in N = 4/118 (3.4%) and normal in 36/118 (30.5%) of patients. After eliminating patients in whom primary ventilatory [7/118 (5.9%)], gas exchange [5/118 (4.2%)], combined respiratory [3/118 (2.5%)] limitation, or cardiac disease limiting exercise [12/118 (10.2%)] was suspected, a primary muscular limitation was presumed in 71/118 (60.2%) patients (Supplementary Fig. 1). In the single control subject with abnormal VO2peak, the anaerobic threshold was normal and there were no signs of ventilatory or gas exchange impairment, nor signs of cardiac ischemia, hence abnormal exercise capacity was likely due to muscular limitation.

Other physical outcomes

As reported previously in general ICU survivors, 5-year follow-up patients performed worse on all other outcomes as compared to controls (Table 3) [6]. Patients who received a CPET had higher peripheral and respiratory muscle strength, performed better on pulmonary function tests, 6-MWD and functional quality-of-life, as compared to those who did not perform CPET.

Table 3.

Demographics, physical outcomes in the post-EPaNIC 5-year follow-up cohort and controls

| EPaNIC 5-year follow-up | Controls | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No CPET | Nb | CPET | Nb | p value | Nb | p value a | ||

| Test location, hospital | 94 (30) | 313 | 361 (100) | 361 | < 0.001 | 49 (100) | 49 | NA |

| Pulmonary function | ||||||||

| FVC (%pred) | 85 ± 24 | 306 | 103 ± 19 | 361 | < 0.001 | 114 ± 14 | 49 | < 0.001 |

| FEV1 (%pred) | 78 ± 24 | 306 | 94 ± 20 | 361 | < 0.001 | 108 ± 12 | 49 | < 0.001 |

| Tiff | 74 ± 10 | 306 | 74 ± 9 | 361 | 0.932 | 77 ± 6 | 49 | 0.022 |

| TLC (%pred) | 92 ± 15 | 82 | 98 ± 15 | 331 | 0.001 | NA | 0 | NA |

| DLCO (%pred) | 72 ± 19 | 97 | 81 ± 17 | 349 | < 0.001 | NA | 0 | NA |

| Muscle strength | ||||||||

| MRC-sum score | 60 (57–60) | 307 | 60 (58–60) | 361 | 0.001 | 60 (60–60) | 49 | < 0.001 |

| HGS (%pred) | 77 ± 29 | 312 | 93 ± 21 | 359 | < 0.001 | 104 ± 19 | 49 | < 0.001 |

| HHD (%pred) | ||||||||

| Shoulder | 86 ± 28 | 304 | 94 ± 22 | 355 | < 0.001 | 104 ± 27 | 49 | 0.002 |

| Elbow | 79 ± 23 | 305 | 89 ± 20 | 360 | < 0.001 | 103 ± 21 | 49 | < 0.001 |

| Wrist | 95 ± 27 | 298 | 102 ± 23 | 360 | < 0.001 | 109 ± 22 | 49 | 0.038 |

| Hip | 139 ± 40 | 297 | 148 ± 33 | 352 | 0.002 | 163 ± 36 | 49 | 0.004 |

| Knee | 53 ± 18 | 293 | 53 ± 15 | 340 | 0.794 | 65 ± 15 | 48 | < 0.001 |

| Ankle | 72 ± 21 | 299 | 73 ± 21 | 358 | 0.480 | 91 ± 22 | 49 | < 0.001 |

| Knee extension (%pred) c | 79 ± 28 | 79 | 86 ± 26 | 333 | 0.037 | 99 ± 30 | 46 | 0.002 |

| MIP (%pred) | 83 ± 32 | 299 | 95 ± 30 | 357 | < 0.001 | 105 ± 27 | 49 | 0.029 |

| Physical function | ||||||||

| 6MWD (%pred) | 81 ± 22 | 206 | 95 ± 19 | 361 | < 0.001 | 115 ± 18 | 49 | < 0.001 |

| Quality of life | ||||||||

| PCS | 42 (32–52) | 290 | 49 (39–55) | 344 | < 0.001 | 56 (52–58) | 49 | < 0.001 |

| PF-SF36 | 60 (30–85) | 306 | 80 (60–95) | 357 | < 0.001 | 95 (90–100) | 49 | < 0.001 |

| MCS | 55 (45–59) | 290 | 55 (49–59) | 344 | 0.689 | 58 (53–60) | 49 | 0.025 |

Continuous variables are depicted as mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range) as appropriate, categorical variables are depicted as number (percentages)

FVC forced vital capacity, FEV1 forced expiratory volume in 1 s, TLC total lung capacity, VC vital capacity, DLCO diffusion capacity, MRC Medical Research Council sum score, HGS hand-grip-strength, HHD handheld dynamometry, MIP maximal inspiratory pressure, 6MWD six-minute-walk-distance, PF-SF36 physical function sub-score of the 36-item Short-Form Health score, MCS Mental Component Score, PCS physical component score

ap value for comparison of patients EPaNIC patients at 5-year follow-up who performed CPET and controls

bNumber of patients for whom data are available

cKnee extension was assessed with Biodex

Association between severity of organ failure and aerobic exercise capacity

Severity of organ dysfunction significantly and independently associated with VO2peak, with a reduction in VO2peak of 0.345 ml/min/kg (95% CI − 0.669 to − 0.021, p = 0.037) per point increase in SOFA-max throughout follow-up (Supplementary Table 4). This effect did not depend on the timing of evaluation during the 1- to 5-year study period. There was no difference between VO2peak at intermediate time points and at 5-year follow-up.

Exploratory analyses

Both knee extensors strength [increase in VO2peak of 0.229 ml/min/kg per 10 N increase in strength (95% CI 0.132–0.327, p < 0.001)] and hip flexors strength at follow-up [increase in VO2peak of 0.182 ml/min/kg per 10 N increase in strength (95% CI 0.071–0.294), p = 0.001] independently associated with VO2peak at follow-up. In these models adjusting for strength at follow-up, SOFA-max remained independently associated with VO2peak. Hence, strength at follow-up did not statistically explain the effect of SOFA-max on VO2peak (Supplementary Table 4).

Discussion

In this cohort of ICU survivors, we evaluated aerobic exercise capacity with cardiopulmonary exercise testing throughout a 5-year follow-up period. Peak oxygen consumption rate and oxygen consumption rate at the anaerobic threshold were lower in 5-year ICU-survivors as compared to demographically matched controls and abnormal exercise capacity was present in 118/313 (37.7%) of patients. Muscular limitation contributed to abnormal exercise capacity in 60.2% of these patients. Adjusted for confounders, the severity of organ failure throughout the ICU stay independently associated with peak oxygen consumption. The association between SOFA max and VO2peak was not explained by strength at follow-up.

Though physical impairments after ICU- and hospital discharge and their association with illness severity are well-documented in various subpopulations of critical illness [1, 3, 7], data on aerobic exercise capacity in ICU survivors are largely uncharted. In a cohort of 50 patients ventilated for at least 5 days, severe exercise limitation with VO2peak at 56% ± 16% and an anaerobic threshold of 41% ± 13% of predicted VO2peak were described, 24 ± 14 days after hospital discharge [14]. In 10 patients, ventilated for acute lung injury, VO2peak was significantly lower 6 weeks following hospital discharge as compared to controls (median 17.8 ml/kg/min versus 31.8 ml/kg/min) [15]. Ong et al. demonstrated reduced VO2peak in 18/44 (41%) SARS-survivors, 3 months after hospital discharge, of which 10 had required intensive care [13]. Our study focused on the longer-term exercise limitations and showed overall improved aerobic exercise capacity as compared to results obtained very early after hospital discharge [14, 15]. However, exercise capacity was still reduced as compared to controls, and 37.7% of patients had an abnormal exercise capacity 5 years following ICU stay, although striking variability between patients was observed. Noteworthy, our data show no difference in exercise capacity between intermediate time-points and the 5-year follow-up point, suggesting recovery of exercise capacity may have occurred within the first year following ICU stay.

We further demonstrated an independent association between in-ICU severity of organ dysfunction and VO2peak in ICU survivors up to 5 years post-ICU. We chose the SOFA-max score to reflect the severity of organ dysfunction throughout the ICU stay, rather than admission severity scores, which would not capture new organ failure due to complications occurring during ICU stay.

Previous data showed that up to 3 months after hospital discharge, deconditioning and muscular factors frequently limited exercise capacity [13–15]. We demonstrated that, at 5 years, muscular limitation contributed to abnormal exercise capacity in 60.2% of cases. This is consistent with previous reports, indicating neuromuscular sequellae of critical illness up to 5 years post-ICU [3, 6], in particular in patients with intensive care unit acquired weakness (ICUAW) [8]. Furthermore, we here demonstrate that hip and knee strength at follow-up independently associate with exercise capacity. Intriguingly, strength at follow-up did not statistically explain the impact of severity of organ failure, an important risk factor for the development of ICUAW [40–45]—and hence for the functional legacy of critical illness—on exercise capacity. This suggests that also mechanisms related to organ failure other than muscle strength contribute to impairment of the integrated exercise response. The number of patients with pulmonary factors contributing to exercise limitation was limited. These findings are in agreement with previous data [13, 14] suggesting that pulmonary function is not the main exercise limiting factor in ICU-survivors, notwithstanding some persistent abnormalities in static pulmonary function.

The observation that a significant amount of ICU survivors has reduced aerobic exercise capacity, not recovering between the 1- and 5-year follow-up period, may have important implications for the management of ICU survivors. Efforts to improve outcomes of ICU survivors after hospital discharge have been largely disappointing [46–48]. Multiple factors may explain the lack of success, notably population heterogeneity, possibly implicating differential rehabilitation potential and need for an individualized approach [49]. As aerobic exercise testing can efficiently guide rehabilitation in various populations [22–25, 50], CPET may stratify patients, and individualise rehabilitation programs in survivors of critical illness, in particular those who experienced more severe organ dysfunction [51]. Presently, data from a single pilot study suggested benefit of tailored rehabilitation schemes on physical function and quality-of-life in ICU survivors, lost upon cessation of the program [52]. Evaluation in larger cohorts seems warranted to identify the window of opportunity for initiation, and feasibility of home-based continuation of such programs.

This study has several strengths. To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest study assessing aerobic exercise capacity in ICU survivors, and the first to repeatedly evaluate cardiorespiratory fitness up to 5 years following ICU stay. As the data were collected in a cohort that was included in a randomized trial, the ICU stay was well documented, allowing to assess and confirm the independent association of exercise limitation with in-ICU severity of organ failure. There are also some limitations. First, patients who performed CPET represented a subgroup of ICU survivors with less severe illness, shorter stays and better overall outcomes as compared to those who did not perform CPET. This was inevitable as patients unable to attend the follow-up clinic or with unstable medical conditions could not participate. Despite this bias, exercise limitation was highly prevalent, suggesting the true burden in the overall population of ICU survivors may be even higher. Second, by excluding submaximal CPETs from classification, we may have missed some patients unable to perform this degree of exercise due to muscular limitation. We lack invasive measurements and used a pragmatic protocol to categorise exercise-limiting factors ensuring feasibility in this large-scale research setting. We were able to identify major cardiopulmonary limitations but may have missed subtle limitations. Third, for the mixed model, as evidence on CPET in ICU-survivors is limited, unmeasured confounding cannot be excluded. In addition, selection bias may have occurred due to the recruitment strategy at intermediate time points which focused on long-stayers. However, mixed models can handle unbalanced designs and major bias seems unlikely as values at intermediate time points were not significantly lower than at 5 years. Fourth, as muscle strength was not systematically assessed during ICU-stay, we could not assess whether the impact of SOFA-max on exercise capacity was mediated by ICUAW. Fifth, as this was a secondary analysis, sample size was not modifiable. Sixth, our controls appeared relatively fit. However, we chose the reference equations described by Jones et al. [30], representing a “sedentary healthy state” [9, 12], and therefore, a good benchmark for our patients, as we wanted to avoid overestimating the prevalence of abnormal exercise capacity. These reference values may be inappropriately low for more active healthy people [9, 53]. However, this issue, nor the size of the control population affects the overall conclusions as defining abnormal exercise capacity in patients was based on comparison with a widely accepted reference population [30] and not as a comparison to our controls. In addition, controls were not included in the mixed model evaluating the association between SOFA-max and VO2peak. Seventh, we did not study post-ICU events, which could potentially contribute to exercise capacity. Finally, as our population was derived from an RCT, generalisability may be limited.

In summary, ICU survivors have impaired aerobic exercise capacity. Severity of organ failure independently associates with exercise performance throughout follow-up. Reduced muscle strength at follow-up also independently associates with reduced exercise capacity but did not explain the effect of severity of organ failure on this outcome. Although causal pathways explaining the lasting reduction in exercise capacity require further exploration, our data suggest a role for CPET in guiding rehabilitation programs in ICU survivors.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to all patients and controls for their participation in this study; to Helena Van Mechelen, Tine Vanhullebusch, Sanne Verweyen, Tim Van Assche for acquisition of data, to Helena Van Mechelen, Tine Vanhullebusch, Sanne Verweyen, Tim Van Assche, Alexandra Hendrickx, Heidi Utens, Sylvia Van Hulle for their technical and administrative support and to Steffen Fieuws for his statistical advice. The abstract of this work was accepted for presentation at the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine meeting 2021.

Author contributions

Study concept and design: GH, NVA, KG, RG. Acquisition of data: GH, PM, YD, AW, MPC, JG, JW, PJW. Analysis and interpretation of data: NVA, GVdB, GH, KG, RG. Drafting of the manuscript: NVA, GH. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: NVA, PM, YD, AW, MPC, JG, JW, KG, RG, PJW, GVdB, GH. Statistical analysis: GH, NVA. Obtained funding: GH, NVA, GVdB, MPC, JG. Administrative, technical support: PJW. Study supervision: GH, PJW, GVdB.

Funding

This work was supported by the Research Foundation—Flanders, Belgium (Grant G.0399.12 to GH; Fundamental Clinical Research fellowship to GH: 1805116 N, to MPC: 1700111 N; aspirant PhD fellowship to NVA: 1131618 N), the Clinical Research and Education Council (KOOR) of the University Hospitals Leuven, Belgium (postdoctoral research fellowship to JG); the Methusalem program of the Flemish Government (METH/08/07 which has been renewed as METH/14/06 via KU Leuven) to GVdB; the European Research Council (ERC) Advanced Grants (AdvG-2012-321670 from the Ideas Program of the EU FP7 and AdvG-2017-785809 from the Horizon 2020 Program of the EU) to GVdB. Baxter provided an unrestricted and non-conditional research grant to KU Leuven between 2007 and 2010.

Declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest with the sponsors of the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Iwashyna TJ, Ely EW, Smith DM, Langa KM. Long-term cognitive impairment and functional disability among survivors of severe sepsis. JAMA. 2010;304:1787–1794. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Winters BD, Eberlein M, Leung J, Needham DM, Pronovost PJ, Sevransky JE. Long-term mortality and quality of life in sepsis: a systematic review. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:1276–1283. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181d8cc1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herridge MS, Tansey CM, Matté A, Tomlinson G, Diaz-Granados N, Cooper A, Guest CB, Mazer CD, Mehta S, Stewart TE, Kudlow P, Cook D, Slutsky AS, Cheung AM, Group CCCT Functional disability 5 years after acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1293–1304. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pfoh ER, Wozniak AW, Colantuoni E, Dinglas VD, Mendez-Tellez PA, Shanholtz C, Ciesla ND, Pronovost PJ, Needham DM. Physical declines occurring after hospital discharge in ARDS survivors: a 5-year longitudinal study. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42:1557–1566. doi: 10.1007/s00134-016-4530-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dinglas VD, Friedman LA, Colantuoni E, Mendez-Tellez PA, Shanholtz CB, Ciesla ND, Pronovost PJ, Needham DM. Muscle weakness and 5-year survival in acute respiratory distress syndrome survivors. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(3):446–453. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hermans G, Van Aerde N, Meersseman P, Van Mechelen H, Debaveye Y, Wilmer A, Gunst J, Casaer MP, Dubois J, Wouters P. Five-year mortality and morbidity impact of prolonged versus brief ICU stay: a propensity score matched cohort study. Thorax. 2019;74:1037–1045. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2018-213020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Needham DM, Wozniak AW, Hough CL, Morris PE, Dinglas VD, Jackson JC, Mendez-Tellez PA, Shanholtz C, Ely EW, Colantuoni E, Hopkins RO, Network NIoHNA Risk factors for physical impairment after acute lung injury in a national, multicenter study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189:1214–1224. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201401-0158OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Aerde N, Meersseman P, Debaveye Y, Wilmer A, Gunst J, Casaer MP, Bruyninckx F, Wouters PJ, Gosselink R, Van den Berghe G. Five-year impact of ICU-acquired neuromuscular complications: a prospective, observational study. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:1184–1193. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-05927-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sietsema K, Sue D, Stringer W, Ward S. Wasserman & Whipp's principles of exercise testing and interpretation. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins (LWW); 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tamai M, Kubota M, Ikeda M, Nagao K, Irikura N, Sugiyama M, Yoshikawa H, Kawamori R, Kamada T. Usefulness of anaerobic threshold for evaluating daily life activity and prescribing exercise to the healthy subjects and patients. J Med Syst. 1993;17:219–225. doi: 10.1007/BF00996949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mezzani A, Agostoni P, Cohen-Solal A, Corra U, Jegier A, Kouidi E, Mazic S, Meurin P, Piepoli M, Simon A. Standards for the use of cardiopulmonary exercise testing for the functional evaluation of cardiac patients: a report from the Exercise Physiology Section of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2009;16:249–267. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e32832914c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beck K, Casaburi R, Johnson B, Marciniuk D, Wagner P, Weisman I, Physicians ATSACoC ATS/ACCP statement on cardiopulmonary exercise testing. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167(2):211–277. doi: 10.1164/rccm.167.2.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ong KC, Ng A-K, Lee L-U, Kaw G, Kwek SK, Leow M-S, Earnest A. Pulmonary function and exercise capacity in survivors of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Eur Respir J. 2004;24:436–442. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00007104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benington S, McWilliams D, Eddleston J, Atkinson D. Exercise testing in survivors of intensive care—is there a role for cardiopulmonary exercise testing? J Crit Care. 2012;27:89–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2011.07.080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mackney J, Harrold M, Jenkins S, Havill K, Hill K. Abnormal exercise responses in survivors of acute lung injury during cardiopulmonary exercise testing: an observational study. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2019;39:E16–E22. doi: 10.1097/HCR.0000000000000432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wei M, Gibbons LW, Kampert JB, Nichaman MZ, Blair SN. Low cardiorespiratory fitness and physical inactivity as predictors of mortality in men with type 2 diabetes. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:605–611. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-8-200004180-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guazzi M, Dickstein K, Vicenzi M, Arena R. Six-minute walk test and cardiopulmonary exercise testing in patients with chronic heart failure: a comparative analysis on clinical and prognostic insights. Circ Heart Fail. 2009;2:549–555. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.109.881326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ross R, Blair SN, Arena R, Church TS, Després J-P, Franklin BA, Haskell WL, Kaminsky LA, Levine BD, Lavie CJ. Importance of assessing cardiorespiratory fitness in clinical practice: a case for fitness as a clinical vital sign: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;134:e653–e699. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kodama S, Saito K, Tanaka S, Maki M, Yachi Y, Asumi M, Sugawara A, Totsuka K, Shimano H, Ohashi Y. Cardiorespiratory fitness as a quantitative predictor of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events in healthy men and women: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2009;301:2024–2035. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Imboden MT, Harber MP, Whaley MH, Finch WH, Bishop DL, Kaminsky LA. Cardiorespiratory fitness and mortality in healthy men and women. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:2283–2292. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.08.2166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anderson L, Taylor RS. Cardiac rehabilitation for people with heart disease: an overview of Cochrane systematic reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2014(12):CD011273. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011273.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Long L, Mordi IR, Bridges C, Sagar VA, Davies EJ, Coats AJ, Dalal H, Rees K, Singh SJ, Taylor RS. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for adults with heart failure. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;1(1):CD003331. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003331.pub5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCarthy B, Casey D, Devane D, Murphy K, Murphy E, Lacasse Y. Pulmonary rehabilitation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;23(2):CD003793. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003793.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yamamoto R, Ito T, Nagasawa Y, Matsui K, Egawa M, Nanami M, Isaka Y, Okada H. Efficacy of aerobic exercise on the cardiometabolic and renal outcomes in patients with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Nephrol. 2021;34(1):155–164. doi: 10.1007/s40620-020-00865-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luo L, Meng H, Wang Z, Zhu S, Yuan S, Wang Y, Wang Q. Effect of high-intensity exercise on cardiorespiratory fitness in stroke survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2020;63:59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.rehab.2019.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Palermo P, Corra U. Exercise prescriptions for training and rehabilitation in patients with heart and lung disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14:S59–S66. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201702-160FR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Swank AM, Horton J, Fleg JL, Fonarow GC, Keteyian S, Goldberg L, Wolfel G, Handberg EM, Bensimhon D, Illiou M-C. Modest increase in peak VO2 is related to better clinical outcomes in chronic heart failure patients: results from heart failure and a controlled trial to investigate outcomes of exercise training. Circ Heart Fail. 2012;5:579–585. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.111.965186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smart N, Steele M. Exercise training in haemodialysis patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nephrology. 2011;16:626–632. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2011.01471.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hermans G, Van Aerde N, Meersseman P, Van Mechelen H, Debaveye Y, Wilmer A, Gunst J, Casaer MP, Dubois J, Wouters P, Gosselink R, Van den Berghe G. Five-year mortality and morbidity impact of prolonged versus brief ICU stay: a propensity score matched cohort study. Thorax. 2019;74:1037–1045. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2018-213020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones NL, Makrides L, Hitchcock C, Chypchar T, McCartney N. Normal standards for an incremental progressive cycle ergometer test. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1985;131:700–708. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1985.131.5.700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fletcher GF, Ades PA, Kligfield P, Arena R, Balady GJ, Bittner VA, Coke LA, Fleg JL, Forman DE, Gerber TC. Exercise standards for testing and training: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;128:873–934. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31829b5b44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Groepenhoff H, de Jeu RC, Schot R. Vyntus CPX compared to Oxycon pro shows equal gas-exchange and ventilation during exercise. Eur Respir J. 2017;50:PA3002. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leclerc K. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing: a contemporary and versatile clinical tool. Cleve Clin J Med. 2017;84:161–168. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.84a.15013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Radtke T, Crook S, Kaltsakas G, Louvaris Z, Berton D, Urquhart DS, Kampouras A, Rabinovich RA, Verges S, Kontopidis D. ERS statement on standardisation of cardiopulmonary exercise testing in chronic lung diseases. Eur Respir Rev. 2019;28(154):180101. doi: 10.1183/16000617.0101-2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vincent J-L, Moreno R, Takala J, Willatts S, De Mendonça A, Bruining H, Reinhart C, Suter P, Thijs LG. The SOFA (Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. Intensive Care Med. 1996;22:707–710. doi: 10.1007/BF01709751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Amaral ACK-B, Andrade FM, Moreno R, Artigas A, Cantraine F, Vincent J-L. Use of the sequential organ failure assessment score as a severity score. Intensive Care Med. 2005;31:243–249. doi: 10.1007/s00134-004-2528-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lederer DJ, Bell SC, Branson RD, Chalmers JD, Marshall R, Maslove DM, Ost DE, Punjabi NM, Schatz M, Smyth AR. Control of confounding and reporting of results in causal inference studies. Guidance for authors from editors of respiratory, sleep, and critical care journals. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2019;16:22–28. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201808-564PS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mallinckrodt CH, Sanger TM, Dubé S, DeBrota DJ, Molenberghs G, Carroll RJ, Potter WZ, Tollefson GD. Assessing and interpreting treatment effects in longitudinal clinical trials with missing data. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53:754–760. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(02)01867-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Molenberghs G, Thijs H, Jansen I, Beunckens C, Kenward MG, Mallinckrodt C, Carroll RJ. Analyzing incomplete longitudinal clinical trial data. Biostatistics. 2004;5:445–464. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxh001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.de Letter MA, Schmitz PI, Visser LH, Verheul FA, Schellens RL, Op de Coul DA, van der Meché FG. Risk factors for the development of polyneuropathy and myopathy in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:2281–2286. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200112000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Garnacho-Montero J, Madrazo-Osuna J, García-Garmendia JL, Ortiz-Leyba C, Jiménez-Jiménez FJ, Barrero-Almodóvar A, Garnacho-Montero MC, Moyano-Del-Estad MR. Critical illness polyneuropathy: risk factors and clinical consequences. A cohort study in septic patients. Intensive Care Med. 2001;27:1288–1296. doi: 10.1007/s001340101009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.De Jonghe B, Sharshar T, Lefaucheur JP, Authier FJ, Durand-Zaleski I, Boussarsar M, Cerf C, Renaud E, Mesrati F, Carlet J, Raphaël JC, Outin H, Bastuji-Garin S, GdRedEdNe R. Paresis acquired in the intensive care unit: a prospective multicenter study. JAMA. 2002;288:2859–2867. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.22.2859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bednarík J, Vondracek P, Dusek L, Moravcova E, Cundrle I. Risk factors for critical illness polyneuromyopathy. J Neurol. 2005;252:343–351. doi: 10.1007/s00415-005-0654-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nanas S, Kritikos K, Angelopoulos E, Siafaka A, Tsikriki S, Poriazi M, Kanaloupiti D, Kontogeorgi M, Pratikaki M, Zervakis D, Routsi C, Roussos C. Predisposing factors for critical illness polyneuromyopathy in a multidisciplinary intensive care unit. Acta Neurol Scand. 2008;118:175–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2008.00996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schmidt SB, Rollnik JD. Critical illness polyneuropathy (CIP) in neurological early rehabilitation: clinical and neurophysiological features. BMC Neurol. 2016;16:1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12883-016-0775-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Connolly B, Salisbury L, O'Neill B, Geneen LJ, Douiri A, Grocott MP, Hart N, Walsh TS, Blackwood B, Group E. Exercise rehabilitation following intensive care unit discharge for recovery from critical illness. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;6:CD008632. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008632.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Denehy L, Skinner EH, Edbrooke L, Haines K, Warrillow S, Hawthorne G, Gough K, Vander Hoorn S, Morris ME, Berney S. Exercise rehabilitation for patients with critical illness: a randomized controlled trial with 12 months of follow-up. Crit Care. 2013;17:1–12. doi: 10.1186/cc12835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mehlhorn J, Freytag A, Schmidt K, Brunkhorst FM, Graf J, Troitzsch U, Schlattmann P, Wensing M, Gensichen J. Rehabilitation interventions for postintensive care syndrome: a systematic review. Crit Care Med. 2014;42:1263–1271. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Herridge MS, Chu LM, Matte A, Tomlinson G, Chan L, Thomas C, Friedrich JO, Mehta S, Lamontagne F, Levasseur M. The RECOVER program: disability risk groups and 1-year outcome after 7 or more days of mechanical ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194:831–844. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201512-2343OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lakoski SG, Eves ND, Douglas PS, Jones LW. Exercise rehabilitation in patients with cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2012;9(5):288–296. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2012.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Molinger J, Pastva AM, Whittle J, Wischmeyer PE. Novel approaches to metabolic assessment and structured exercise to promote recovery in ICU survivors. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2020;26:369–378. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0000000000000748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Batterham A, Bonner S, Wright J, Howell S, Hugill K, Danjoux G. Effect of supervised aerobic exercise rehabilitation on physical fitness and quality-of-life in survivors of critical illness: an exploratory minimized controlled trial (PIX study) Br J Anaesth. 2014;113:130–137. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeu051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wagner J, Knaier R, Infanger D, Königstein K, Klenk C, Carrard J, Hanssen H, Hinrichs T, Seals D, Schmidt-Trucksäss A. Novel CPET reference values in healthy adults: associations with physical activity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2020;53:26–37. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000002454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.