Abstract

Background

Lung cancer has a poor prognosis; the number of long-term survivors (LTSs) is small compared with that of other cancers. Few studies have focused on late recurrence in LTSs with lung cancer. The purpose of this study was to analyze the risk factors for survival and late recurrence in LTSs after disease-free period of 5 years.

Methods

A retrospective analysis of patients with a disease-free survival of at least 5 years after surgical resection for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) between January 1998 and December 2012 was conducted. Patients who underwent neo-adjuvant therapy, had an incomplete resection, or had advanced stage (stages IIIb and IV) cancer were excluded.

Results

A total of 1,254 (53.2%) of 2,357 patients were enrolled. Of these, 759 (60.5%) were men, and the mean patient age was 61.9±10.1 (range, 10–87 years) years. Pathologic N0 (997 patients, 79.5%) and stage I (860 patients, 68.6%) were the dominant stages. Late recurrence occurred in 22 patients (1.8%) 5 years postoperatively. On multivariate analysis, male sex, older age, node-positive status, and late recurrence were found to be independent risk factors for overall survival (OS), while a node-positive status was the only independent risk factor for disease-free survival [hazard ratio (HR) =3.824; P=0.002; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.658–8.821].

Conclusions

The nodal stage at the time of surgical resection was found to be an independent risk factor for both OS and disease-free survival 5 years after initial treatment in patients with completely resected NSCLC.

Keywords: Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), 5-year disease-free survival, late recurrence, risk factor, N stage

Introduction

The past 30 years have seen substantial improvements in the 5-year survival rates of patients with various cancers; however, the 5-year survival rate for patients with lung cancer remains 19%. This is because most patients with lung cancer are diagnosed at an advanced stage (1). Approximately 50% of patients with resected non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) die within 5 years after surgery (2,3). Thus, very few patients survive in the long term after the initial treatment for NSCLC.

In most previous studies, the outcomes of patients with lung cancer have been evaluated in terms of 5-year survival after the initial treatment (4). The definition of a long-term survivor (LTS) of lung cancer is controversial (5-7). In this study, a LTS was defined as an absence of recurrence over a follow-up period of at least 5 years after complete surgical resection. Lung cancer has a bad prognosis; however, it has improved because of early diagnosis and multimodal treatments. This leads to the increase of the number of LTSs. Thus, exploring the risk factors for survival and late recurrence in LTSs of NSCLC is crucial.

After a 5-year disease-free period, LTSs still can develop recurrence; this is defined as late recurrence in patients with resected NSCLC (6). Recently, the number of LTSs of resected NSCLC has increased because of improvements enabling early diagnosis and multimodal treatments (8). Nevertheless, few studies have focused on late recurrence in LTSs with NSCLC. Moreover, only a small number of those studies have attempted to identify the risk factors for overall survival (OS) or recurrence-free survival (RFS) beyond 5 years in LTSs (3,5,6).

The aim of this study was therefore to determine the risk factors for survival and late recurrence in LTSs of NSCLC after a 5-year follow-up period.

We present the following article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jtd-21-854).

Methods

We conducted a retrospective study of patients who underwent surgical resection for NSCLC at a single hospital between January 1998 and December 2012. Lung cancer stages were adjusted according to the 7th edition of the American Joint Commission for Cancer TNM classification (4). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). This study was approved by the Severance Hospital Institutional Review Board (approved November 20, 2016, approval 4-2016-0862). The patients provided informed consent for the publication of the study data.

Patients

Patients with RFS for 5 years after surgical treatment and a confirmed pathologic stage from I to IIIa were enrolled in the study. The medical records of these patients were carefully reviewed in terms of sex, age, smoking status, tumor site, type of operation, pathologic data, adjuvant therapy, late recurrence, second primary cancer (SPC), cause of death, and survival. Patients who had undergone neo-adjuvant therapy, or incomplete resection, those who did not have NSCLC, or those with an advanced stage (stages IIIb and IV) were excluded (Figure S1). All patients underwent systematic mediastinal lymph node dissection or sampling, according to International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC) criteria (9). RFS was defined as the time from operation to recurrence of tumor.

Follow-up

After surgery, all patients received routine postoperative care and follow-up. Follow-up was achieved through regular clinic visits until the patient’s death. The patients who did not visit the hospital were followed up via phone calls. Patients were examined at 6-month intervals for the first 2 years and at 1-year intervals for the next 5 years. The evaluation included a physical examination, chest radiography, and measurement of tumor markers. Chest computed tomography (CT), abdominal CT, or positron emission tomography (PET)-CT scans were obtained at 6-month intervals for a period of 5 years after surgery and then annually thereafter. Brain MRI scans were performed when the patient had signs or symptoms of recurrence. OS, RFS, follow-up time was calculated from surgery.

Recurrence

Recurrence was diagnosed based on pathologic results or imaging studies (including chest CT, abdominal CT, brain CT, whole body bone scan, or PET-CT). The diagnosis of lung cancer late recurrence was approved by an interdisciplinary tumor board consisting of thoracic surgeons, medical oncologists, radiologists and pathologists. Local recurrence was defined as disease in the ipsilateral lung, mediastinum, or regional lymph nodes and distant recurrence as disease in the contralateral lung, mediastinum, or outside the hemithorax. SPC was distinguished from recurrences according to the Marini-Melamed criteria (10): different histologic profile from the index tumor; same histologic profile as the index tumor but diagnosed 2 years later; or same histologic profile as the index tumor, diagnosed within 2 years, but in a separate lobe or segment, without involvement of intervening lymph nodes or metastasis. And SPC was diagnosed based on pathologic results according to American College of Chest Physicians guidelines (11). Patients diagnosed with recurrence without pathology are those with bilateral or extrapulmonary metastases without a history of other cancers. Late recurrence was defined as recurrence that occurred more than 5 years after surgical resection in LTSs. Late SPC was defined using the same criteria.

Statistical analyses

Continuous data are expressed as means with standard deviations and categorical data as frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables were analyzed using Student’s t-test, and categorical variables were analyzed using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. The survival rate was analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method. The log-rank test was used to assess statistical significance. A stepwise multivariable Cox proportional hazards model was used among statistically significant variables (P<0.05) in the univariate model. Multivariable analysis was performed using Cox’s proportional hazards regression model to evaluate the effects of multiple variables on survival and late recurrence. A P value less than 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. SPSS ver. 25.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used to perform the statistical analyses.

Results

Patients

A total of 2,357 patients underwent surgical resection for NSCLC at a single institution between January 1998 and December 2012. Of these, 1,254 patients (53.2%) survived without recurrence for 5 years after surgery. The study patients included 759 (60.5%) men, and the mean patient age was 61.9±10.1 (range, 10–87) years. The most common type of surgery performed was lobectomy (1,046 patients, 83.4%), followed by pneumonectomy (94 patients, 7.5%). Adenocarcinoma was the most common histology (756 patients, 60.3%). Cases of pathologic N0 (997 patients, 79.5%) and stage I (860 patients, 68.6%) were more common than the cases of other stages in this study (Table 1).

Table 1. Demographic and characteristics of 1,254 patients.

| Variables | Patients | |

|---|---|---|

| Total (n=1,254) | Recurrence (n=22) | |

| Male | 759 (60.5) | 14 (63.6) |

| Age, y | 61.9±10.1 | 59.1±10.3 |

| 70≤ age | 287 (22.9) | 4 (16.0) |

| Smoking history | 561 (44.7) | 10 (45.5) |

| Operation | ||

| Sublobar resection | 26 (2.1) | 0 |

| Bilobectomy | 88 (7.0) | 4 (18.2) |

| Lobectomy | 1,046 (83.4) | 13 (59.1) |

| Pneumonectomy | 94 (7.5) | 5 (22.7) |

| Histology | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 756 (60.3) | 8 (36.4) |

| Squamous | 393 (31.3) | 12 (54.5) |

| Mixed | 14 (1.1) | 1 (4.5) |

| Others | 91 (7.3) | 1 (4.5) |

| p-N stage | ||

| N0 | 997 (79.5) | 11 (50.0) |

| N1 | 153 (12.2) | 6 (27.3) |

| N2 | 104 (8.3) | 5 (22.7) |

| p-stage | ||

| I | 860 (68.6) | 7 (31.8) |

| II | 251 (20.0) | 9 (40.9) |

| IIIa | 143 (11.4) | 6 (27.3) |

| RFS, m | 115.8±41.1 | 83.0±19.8 |

| OS, m | 116.3±41.0 | 114.1±34.0 |

| Post-recurrence survival, m | – | 32.9±33.0 |

Data are presented as number of patients (percentage) or mean ± standard deviation. p-, pathologic; RFS, recurrence-free survival; OS, overall survival.

Outcomes of LTS

Follow-up was completed in all patients, and the mean follow-up duration was 116.4±41.0 (range, 60.0–246.1) months. Of the total number of patients, 185 (14.8%) died, of whom 78 (42.2%) died of cancer-related illnesses. The mean OS time was 116.3±41.0 (range, 60.0–246.1) months.

Late recurrence occurred in 1.8% (22 cases of patients, comprising 6 cases (27.3%) of local recurrence, 11 cases (50.0%) of distant recurrence, and 5 cases (22.7%) of simultaneous local and distant recurrence. The mean RFS time was 115.8±41.1 (range, 60.0–246.1) months (Table 2). The most common recurrence site was the lung (15 cases, 68.2%), followed by the brain (4 cases, 18.2%). Among the lung recurrence, contralateral lung (5 cases, 22.7%), bilateral lung (5 cases, 22.7%), and ipsilateral lung (5 cases, 22.7%) were equally distributed. Sixteen patients (72.7%) had late recurrence, as confirmed through tissue biopsy, and 12 (80.0%) had lung recurrence, as confirmed through pulmonary biopsy (among 16 patients). Patients with late recurrence had a lower 10-year OS rate than those without (31.8% vs. 87.0%, P<0.001).

Table 2. Post-operative results.

| Variables | Patients |

|---|---|

| Follow-up, m | 114.1±34.0 |

| Adjuvant therapy | 551 (43.6) |

| Chemotherapy | 460 (36.7) |

| Chemotherapy + radiotherapy | 72 (5.7) |

| Radiotherapy | 19 (1.5) |

| Death | 185 (14.8) |

| Cancer-related | 78 (42.1) |

| Non-cancer-related | 37 (20) |

| Unknown | 70 (37.8) |

| OS time, m | 116.3±41.0 |

| Late recurrence | 22 (1.8) |

| Local | 6 (27.3) |

| Distant | 11 (50.0) |

| Local + distant | 5 (22.7) |

| Disease-free survival time, m | 115.8±41.1 |

| SPC | 89 (7.1) |

| Lung | 48 (53.9) |

| SPC, after 5 years | 22 (1.8) |

| Lung | 11 (50.0) |

Data are presented as number of patients (percentage) or mean ± standard deviation. OS, overall survival; SPC, second primary cancer.

SPC was observed in 89 patients (7.1%) during the follow-up period, the most common site being the lung (48 cases, 53.9%), followed by the stomach (8 cases, 9.0%), thyroid (8 cases, 9.0%), and colorectum (7 cases, 7.9%). The diagnoses of 48 patients who had an SPC in the lung were confirmed through pathology. The OS of patients with SPC was 133.1±44.5 months, and the SPC was not deemed a risk factor for OS (P=0.179) or RFS (P=0.365) among the LTSs of resected NSCLC (Figures S2,S3). Forty-eight patients (3.8%) developed an SPC in the lung after primary surgery and 11 patients (0.9%) developed an SPC in the lung more than 5 years after primary surgery. A late SPC was observed in 22 patients (1.8%), including an SPC in the lung in 11 patients (50.0%) and colorectal cancer in 4 patients (18.2%). All 11 patients with late lung SPCs were diagnosed based on their pathologic results (Table 2).

In the current study, no difference was found in the late recurrence rate with regard to the type of operation performed (P=0.353): 5/94 patients (5.3%) experienced late recurrence after pneumonectomy, 4/88 (4.5%) late recurrence after bilobectomy, and 13/1,046 (1.2%) late recurrence after lobectomy.

Outcomes of late recurrence

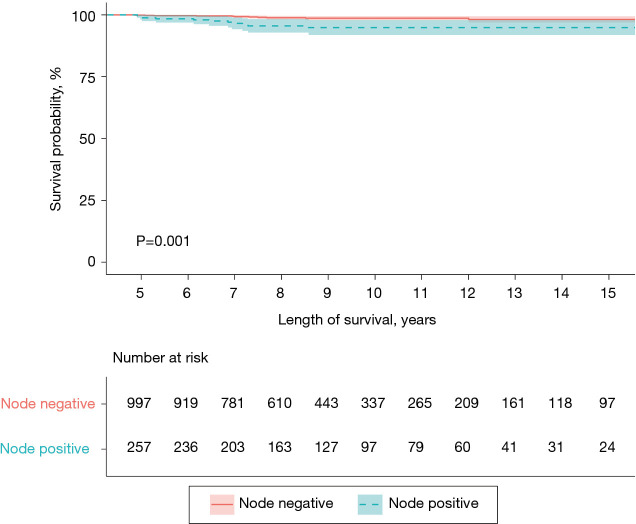

In the patients with late recurrence, the mean age was 59.1±10.3 (range, 28–76) years, and 14 (63.6%) were men. The most common type of operation performed was lobectomy (13 patients, 59.1%), followed by pneumonectomy (5 patients, 22.7%). Squamous cell carcinoma was the most common histology (12 patients, 54.5%). Pathologic N0 (11 patients, 50.0%) was more common, and patients with a node-positive status (N1+N2) had a lower 10-year RFS than those with a node-negative status (94.8% vs. 98.7%, P=0.001, Figure 1). The numbers of patients in each stage were similar: 7 patients (31.8%) in stage I, 9 patients (40.9%) in stage II, and 6 patients (27.3%) in stage IIIa. The mean RFS time was 83.0±19.8 months, and the mean OS time was 114.1±34.0 months. The mean post-recurrence survival was 32.9±33.0 months. Nineteen patients (86.4%) died during the follow-up period, including 14 (73.7%) who died from cancer-related illness (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Comparison of RFS between the node positive and node negative groups for long-term survivors with complete resected NSCLC, derived using the Kaplan-Meier method. There was a significant difference in the RFS between the two groups (P=0.001). RFS, recurrence-free survival; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer.

Multivariate analysis

Multivariate analysis was performed to determine the independent risk factors of OS and RFS. Male sex, age, node-positive (N1+N2) status, and late recurrence were identified as independent risk factors for OS. In the RFS analysis, however, sex, age, T-stage, histology, type of operation, and adjuvant therapy were not found to be risk factors. A node-positive status was the only independent risk factor found on multivariate analysis (Tables 3,4).

Table 3. Univariate and multivariate analyses of OS.

| Factor | HR | 95% CI | P value | HR | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (vs. female) | 3.011 | 2.057–4.408 | <0.001 | 2.633 | 1.747–3.966 | <0.001 |

| Age ≥70 (vs. <70) | 2.397 | 1.730–3.320 | <0.001 | 2.423 | 1.746–3.364 | <0.001 |

| Smoking | 2.094 | 1.550–2.830 | <0.001 | 1.040 | 0.712–1.518 | 0.839 |

| p-N stage | 1.974 | 1.458–2.673 | <0.001 | 1.643 | 1.182–2.283 | 0.003 |

| SPC | 1.358 | 0.869–2.121 | 0.179 | 0.968 | 0.394–2.377 | 0.943 |

| Late recurrence | 6.590 | 4.096–10.603 | <0.001 | 6.323 | 4.518–11.870 | <0.001 |

| Operative method | ||||||

| Lobectomy | 1 | – | – | 1 | – | – |

| Sublobar resection | 0.639 | 0.089–4.586 | 0.656 | 0.870 | 0.121–6.277 | 0.890 |

| Bilobectomy | 1.584 | 1.011–2.480 | 0.044 | 1.154 | 0.712–1.870 | 0.562 |

| Pneumonectomy | 2.408 | 1.677–3.459 | <0.001 | 1.526 | 1.008–2.311 | 0.046 |

| Histology | ||||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 1 | – | – | 1 | – | – |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 2.189 | 1.601–2.994 | <0.001 | 1.063 | 0.713–1.584 | 0.765 |

| Mixed | 2.450 | 0.770–7.790 | 0.129 | 1.208 | 0.360–4.047 | 0.760 |

| Other | 1.369 | 0.791–2.369 | 0.262 | 1.101 | 0.610–1.989 | 0.749 |

| p-T stage | ||||||

| 1 | 1 | – | – | – | – | – |

| 2 | 1.079 | 0.791–1.473 | 0.630 | – | – | – |

| 3 | 1.054 | 0.645–1.722 | 0.833 | – | – | – |

| 4 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.950 | – | – | – |

OS, overall survival; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; SPC, second primary cancer; p-, pathologic.

Table 4. Univariate and multivariate analyses of disease-free survival.

| Factor | HR | 95% CI | P value | HR | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (vs. female) | 1.120 | 0.470–2.671 | 0.798 | – | – | – |

| Age ≥70 (vs. <70) | 0.376 | 0.088–1.612 | 0.188 | 0.388 | 0.091–1.665 | 0.203 |

| Smoking | 0.987 | 0.426–2.285 | 0.976 | – | – | – |

| p-N stage | 3.797 | 1.646–8.758 | 0.002 | 3.824 | 1.658–8.821 | 0.002 |

| SPC | 0.044 | 0.000–38.082 | 0.365 | – | – | – |

| Operative method | ||||||

| Lobectomy | 1 | – | – | 1 | – | – |

| Sublobar resection | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.982 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.983 |

| Bilobectomy | 3.220 | 1.048–9.896 | 0.041 | 2.694 | 0.868–8.365 | 0.086 |

| Pneumonectomy | 3.627 | 1.289–10.203 | 0.015 | 2.286 | 0.753–6.938 | 0.144 |

| Histology | ||||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 1 | – | – | 1 | – | – |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 2.655 | 1.083–6.508 | 0.033 | 1.560 | 0.563–4.326 | 0.393 |

| Mixed | 6.497 | 0.812–51.962 | 0.078 | 4.382 | 0.523–36.706 | 0.173 |

| Other | 0.938 | 0.117–7.508 | 0.952 | 0.718 | 0.088–5.871 | 0.757 |

| p-T stage | ||||||

| 1 | 1 | – | – | – | – | – |

| 2 | 1.842 | 0.734–43624 | 0.193 | – | – | – |

| 3 | 1.386 | 0.287–6.699 | 0.684 | – | – | – |

| 4 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.984 | – | – | – |

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; SPC, second primary cancer; p-, pathologic.

Discussion

Lung cancer is usually diagnosed at an advanced stage; as a result, it has a generally poor prognosis (1,12). Therefore, the number of LTSs of lung cancer is small compared with that of other cancers (13-15). The risk factors for OS among LTSs have yet to be fully investigated.

In a previous study, age, positive N stage, and complete resection were significant prognostic factors for patients who survived more than 5 years after surgery for lung cancer (7). However, other studies showed that age, sex, histology, and stage were not risk factors for late recurrence or survival (5,6), and the 5-year RFS time from the time of initial treatment was the only prognostic factor for survival among LTSs (6). In a recent study (3), age, node-negative status, and lobar or greater resection positively affected the OS of LTSs. However, the type of patients differed between that study and ours, in that, unlike the present study, that study enrolled patients with non-surgical treatments.

In the present study, patients with a RFS time of at least 5 years after surgical resection were included; we determined that age, node-positive status, and late recurrence were independent risk factors for OS among cured patients (Tables 3,4). Generally, a LTS patient is regarded as a survivor of at least 5 years after the initial treatment for lung cancer, and this term has been used synonymously with cure. However, three are other views about the definition of cure in lung cancer. Some authors suggest that a 5-year interval might be long enough to declare a patient with NSCLC as cured (5,6,16). In contrast, others argue that a 5-year survival without NSCLC recurrence does not mean cure because LTSs present a persistent risk of late recurrence and death from lung cancer more than 5 years after treatment (3,7,17).

In this study, a cure (LTS) was defined as a RFS of 5 years or more after surgical resection. Despite enrolling only cured patients, late recurrences and cancer-related deaths were observed nevertheless. A previous study reported that the prevalence of late recurrence was 3.8% among cured patients (6), and the present study reported a rate of 1.8% (22 patients). Thus, late recurrence can occur in cured patients as well. Further studies are therefore needed to properly define “cured” in NSCLC. In addition, late recurrence was found to be a risk factor for survival among LTSs of NSCLC (6), and our results were similar to those of that study [hazard ratio (HR) =6.323, P<0.001, 95% confidence interval (CI): 4.518–11.870; Table 3]. However, various constraints were present regarding the risk factor analysis of late recurrence in LTSs, and this was the motivation for the present study.

Martini et al. found that age, sex, histologic condition, and stage were not determinants of the risk of late recurrence (6). However, they enrolled patients who had survived longer than 5 years after NSCLC recurrence during the follow-up period. In our study, we excluded patients who experienced recurrence within 5 years of the initial treatment (surgical resection) and showed that a node-positive status was an independent risk factor for disease-free survival in LTSs of NSCLC (HR =3.824, P=0.002, 95% CI: 1.658–8.821; Table 4). We consider that the difference in study populations between the two studies led to the different results.

In the present study, age and the extent of tobacco use were also not found to be risk factors for late recurrence. Similarly, previous studies have shown that age was not a risk factor for recurrence (18,19) or late recurrence (5,6) among patients with NSCLC after surgical resection. A previous study found more pack-years of smoking to be a risk for late recurrence (17). The cancer stage has been analyzed as a RFS risk factor in lung cancer (20), although there are different results whether the stage is a risk factor in LTSs (6). Taken together, our data reveal that the stage was found to be a risk factor for RFS (P=0.004), but only in terms of the N stage (P=0.017) rather than the T-stage (P=0.144). Therefore, we believe that the N stage has a greater association with late recurrence than does the T stage. We think that additional researches are needed to corroborate this result.

The N2 stage is considered a more advanced stage of lung cancer, and such patients tend to relapse more often than the N1 stage patients (21). However, the effect of the N stage in LTSs of lung cancer is unclear. We found that a node-positive (N1+N2) status had a negative effect on late recurrence: late recurrence occurred in 11 patients (50.0%) each with N1 or N2 stage disease. However, there was no difference in RFS between N1 and N2 stages (P=0.609) (Figure S2). In a previous study, patients with resected NSCLC who were node-positive were at a significantly increased risk of distant recurrence (20). Similar results were achieved in our study in LTSs of resected NSCLC, in that node-positive patients exhibited a greater rate of distant recurrence (57.1% vs. 81.8%, P=0.141). However, there was no difference in OS according to either local or distant recurrence (P=0.674) (Figure S3). Therefore, regardless of whether local or distant, recurrence was a risk factor for OS among LTSs with resected NSCLC.

All patients experienced late recurrence within 10 years after surgical resection, with the exception of one at 146 months. Out of a total of 22 patients with late recurrence, 16 (72.7%) were confirmed through pathology and 6 (27.3%) through imaging.

This study has some limitations. First, it was a retrospective study conducted at a single center. Second, the number of patients was relatively small, even though our study included LTS patients with a RFS of at least 5 years after NSCLC resection. There may be follow-up underestimation due to loss of follow-up over 5 years. Third, the therapeutic value of adjuvant therapy (chemotherapy regimen and cycle, radiation dose, and field) was not fully evaluated. Fourth, the molecular tumor characterization for the primary resected tumor and tumor with late recurrence was not included in this study. Notwithstanding these limitations, this study is valuable in that it was performed in patients with a recurrence-free interval of at least 5 years after surgical resection, a factor that has not been evaluated in previous studies.

Conclusions

This study confirmed that late recurrence occurred in LTSs who had not experienced recurrence during the 5-year after surgical resection (1.8%), and this had a negative effect on OS more than 5 years after the operation. Furthermore, late recurrence frequently occurred in patients who were node-positive (4.3%), which was found to be an independent risk factor for late recurrence. Therefore, careful follow-up is needed for the detection of late recurrence even in LTSs with a RFS of at least 5 years, particularly in node-positive patients.

Supplementary

The article’s supplementary files as

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). This study was approved by the Severance Hospital Institutional Review Board (approval number: 4-2016-0862). The patients provided informed consent for the publication of the study data.

Footnotes

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jtd-21-854

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jtd-21-854

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jtd-21-854). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, et al. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin 2010;60:277-300. Erratum in: CA Cancer J Clin 2011;61:133-4. 10.3322/caac.20073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goya T, Asamura H, Yoshimura H, et al. Prognosis of 6644 resected non-small cell lung cancers in Japan: a Japanese lung cancer registry study. Lung Cancer 2005;50:227-34. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2005.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hubbard MO, Fu P, Margevicius S, et al. Five-year survival does not equal cure in non-small cell lung cancer: a Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results-based analysis of variables affecting 10- to 18-year survival. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2012;143:1307-13. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.01.078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edge SB, Compton CC. The American Joint Committee on Cancer: the 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual and the future of TNM. Ann Surg Oncol 2010;17:1471-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Okada M, Nishio W, Sakamoto T, et al. Long-term survival and prognostic factors of five-year survivors with complete resection of non-small cell lung carcinoma. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2003;126:558-62. 10.1016/S0022-5223(03)00360-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martini N, Rusch VW, Bains MS, et al. Factors influencing ten-year survival in resected stages I to IIIa non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1999;117:32-6; discussion 37-8. 10.1016/S0022-5223(99)70467-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wada H, Fukuse T, Hitomi S. Long-term survival of surgical cases of lung cancer. Lung Cancer 1995;13:269-74. 10.1016/0169-5002(95)00499-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Lung Screening Trial Research Team , Aberle DR, Adams AM, et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med 2011;365:395-409. 10.1056/NEJMoa1102873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rusch VW, Asamura H, Watanabe H, et al. The IASLC lung cancer staging project: a proposal for a new international lymph node map in the forthcoming seventh edition of the TNM classification for lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2009;4:568-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martini N, Melamed MR. Multiple primary lung cancers. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1975;70:606-12. 10.1016/S0022-5223(19)40289-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kozower BD, Larner JM, Detterbeck FC, et al. Special treatment issues in non-small cell lung cancer: Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 2013;143:e369S-99S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeSantis CE, Lin CC, Mariotto AB, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin 2014;64:252-71. 10.3322/caac.21235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chirlaque MD, Salmerón D, Galceran J, et al. Cancer survival in adult patients in Spain. Results from nine population-based cancer registries. Clin Transl Oncol 2018;20:201-11. 10.1007/s12094-017-1710-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jung KW, Won YJ, Kong HJ, et al. Cancer Statistics in Korea: Incidence, Mortality, Survival, and Prevalence in 2016. Cancer Res Treat 2019;51:417-30. 10.4143/crt.2019.138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen JG, Chen HZ, Zhu J, et al. Cancer survival in patients from a hospital-based cancer registry, China. J Cancer 2018;9:851-60. 10.7150/jca.23039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maeda R, Yoshida J, Ishii G, et al. Risk factors for tumor recurrence in patients with early-stage (stage I and II) non-small cell lung cancer: patient selection criteria for adjuvant chemotherapy according to the seventh edition TNM classification. Chest 2011;140:1494-502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murthy SC, Reznik SI, Ogwudu UC, et al. Winning the battle, losing the war: the noncurative “curative” resection for stage I adenocarcinoma of the lung. Ann Thorac Surg 2010;90:1067-74. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.04.108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Früh M, Rolland E, Pignon JP, et al. Pooled analysis of the effect of age on adjuvant cisplatin-based chemotherapy for completely resected non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:3573-81. 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.2727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Landreneau RJ, Normolle DP, Christie NA, et al. Recurrence and survival outcomes after anatomic segmentectomy versus lobectomy for clinical stage I non-small-cell lung cancer: a propensity-matched analysis. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:2449-55. 10.1200/JCO.2013.50.8762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Varlotto JM, Yao AN, DeCamp MM, et al. Nodal stage of surgically resected non-small cell lung cancer and its effect on recurrence patterns and overall survival. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2015;91:765-73. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.12.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Izbicki JR, Passlick B, Pantel K, et al. Effectiveness of radical systematic mediastinal lymphadenectomy in patients with resectable non-small cell lung cancer: results of a prospective randomized trial. Ann Surg 1998;227:138-44. 10.1097/00000658-199801000-00020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The article’s supplementary files as