Keywords: cellular energy distribution, mitochondria, mitochondrial networks, mitochondrial reticulum, oxidative phosphorylation

Abstract

The design of the energy metabolism system in striated muscle remains a major area of investigation. Here, we review our current understanding and emerging hypotheses regarding the metabolic support of muscle contraction. Maintenance of ATP free energy, so called energy homeostasis, via mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation is critical to sustained contractile activity, and this major design criterion is the focus of this review. Cell volume invested in mitochondria reduces the space available for generating contractile force, and this spatial balance between mitochondria acontractile elements to meet the varying sustained power demands across muscle types is another important design criterion. This is accomplished with remarkably similar mass-specific mitochondrial protein composition across muscle types, implying that it is the organization of mitochondria within the muscle cell that is critical to supporting sustained muscle function. Beyond the production of ATP, ubiquitous distribution of ATPases throughout the muscle requires rapid distribution of potential energy across these large cells. Distribution of potential energy has long been thought to occur primarily through facilitated metabolite diffusion, but recent analysis has questioned the importance of this process under normal physiological conditions. Recent structural and functional studies have supported the hypothesis that the mitochondrial reticulum provides a rapid energy distribution system via the conduction of the mitochondrial membrane potential to maintain metabolic homeostasis during contractile activity. We extensively review this aspect of the energy metabolism design contrasting it with metabolite diffusion models and how mitochondrial structure can play a role in the delivery of energy in the striated muscle.

CLINICAL HIGHLIGHTS

The design of the energy metabolism system has major implications for striated muscle function in health and disease. The ability of the muscle to maintain its available energy during alterations in workload is critical for normal function.

The inability to maintain adequate energy supply for muscle contraction has been implicated in several pathologies including heart failure, age-related dysfunction, arrythmias, muscle atrophy, ragged fiber disease, metabolic syndrome, and a host of other chronic and systemic diseases.

Beyond the content and composition of mitochondria in tissue, the structure of mitochondria into interconnected reticulum networks is proposed to be critical in the distribution of energy across the muscle cell. The role of mitochondrial structure in the metabolic design of muscle is now recognized as a critical element in the balance of energy with work in this tissue. However, the role of mitochondrial structure in different disease states has not been extensively evaluated and could be a contributing factor to many energy-related chronic and acute clinical conditions.

1. INTRODUCTION

The purpose of this review is to update the information and hypotheses regarding the mechanisms of distributing energy converted by intermediary metabolism across the mammalian cardiac and skeletal muscle cell to support muscle contraction. To understand the design of energy conversion and distribution in the muscle cell, the entire process needs to be evaluated as it pertains to its physiological function. This includes the vascular supply of basic substrates, carbon sources and oxygen, the cellular energy conversion process, primarily glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation (OxPhos), and finally the structural and biochemical methods to control and distribute the potential energy across the cell generated by the energy conversion processes. The energetics and physiological regulation of the different elements of muscle energy conversion have been a topic of many prior articles in Physiological Reviews illustrating the continuing interest in this basic physiological process. Some titles include the following: Ventricular Energetics by Suga (1), Energetics of Muscular Contraction by Mommaerts (2), Regulation of Increased Blood Flow (Hyperemia) to Muscles During Exercise: A Hierarchy of Competing Physiological Needs by Joyner and Casey (3), Myocardial Fatty Acid Metabolism in Health and Disease by Lopaschuk et al. (4), Muscle KATP Channels: Recent Insights to Energy Sensing and Myoprotection by Flagg et al. (5), Myocardial Substrate Metabolism in the Normal and Failing Heart by Stanley and Lopaschuk (6), Coronary Physiology by Feigl (7), and Myoglobin-Facilitated Oxygen Diffusion: Role of Myoglobin in Oxygen Entry into Muscle by Wittenberg (8).

With such a broad scope, we have attempted to focus our attention on the performance of the muscle approaching maximum workloads under normal physiological conditions. Maximum work load is a major design criterion of the muscle in that it must be able to support maximum workload output in terms of blood flow, intermediary metabolism, and mechanics. Weibel and coworkers (9–11) have also put forward the concept of symmorphosis where all the elements associated with a given physiological performance are tuned to just meet the maximum work output requirements of the tissue with little or no excess. Simply put, symmorphosis proposes that biology optimizes its use of space and protein to accomplish the task at hand without a large, potentially wasteful, excess protein for “reserve” or as part of the regulatory system. This design concept has been called “enough but not too much” by Diamond (12), who also pointed out the importance of optimizing space in biological systems. Although details of this hypothesis have been challenged (14, 15), this concept provides a theoretical framework to focus on the structural and biochemical design of heart and skeletal muscle function approaching maximum workload conditions.

What are the maximum workload conditions for heart and skeletal muscle? For the heart, the question is rather straightforward since the heart works primarily in a sustainable manner providing constant workload over a long period of time supported, in the steady state, by coronary blood flow and OxPhos. Thus we consider the maximum work of the heart to be the maximum sustainable cardiac output under physiological conditions.

The skeletal muscle is much more complex as it has at least two types of maximum power requirements as well as many different muscle types. The two conditions we will be considering are peak nonsustainable power, where metabolic recovery capacity may be more important than the sustainable rate of energy conversion, while the other is maximal sustained power, commonly called critical power (16–18), where the energy conversion of intermediary metabolism can support muscle contractile power for a sustained period of time. Of these two measures, critical power is similar to the maximum sustainable cardiac output for the heart. With the remarkable variety of skeletal muscle fiber types, we will be seeking common elements consistent across most muscle fiber types.

The energy conversion design of the heart and skeletal muscle will be discussed separately. Due to the very different design constraints on skeletal muscle and heart, we will focus any comparisons between heart and skeletal muscle to the maximum sustained power conditions. Skeletal muscle will be evaluated simply as fast-twitch, glycolytic and slow twitch, oxidative fiber types, with specific qualifications so as to not overly simplify the true spectrum of skeletal muscle fiber types where contractile and metabolic phenotypes may diverge. Additionally, for specific elements in the energy distribution system such as myoglobin, creatine kinase, and the mitochondrial reticulum, the historical and theoretical understanding of these systems will be covered when they are introduced. A more detailed summary of the overall muscle designs will be provided in sect. 4 of the review. Finally, while it is well appreciated that deficits in energy conversion capacity within the striated muscle cell have been implicated in many pathologies, the focus of this review will be on the energy metabolism design of the healthy striated muscle cell. Reviews on the role of muscle energy metabolism in heart failure (19–21), metabolic syndrome (22–24), aging (25, 26), arrhythmias (27, 28), and atrophy (29, 30) can be found elsewhere.

2. METABOLIC HOMEOSTASIS IN STRIATED MUSCLE

The muscle is a remarkable machine, converting chemical potential energy into contractile work. It does this in a rather efficient manner in human skeletal muscle running at ∼20% total efficiency (31); for review see Ref. 32. The muscle performs work primarily using the energy conversion processes of cytosolic glycolysis and mitochondrial OxPhos, which are precisely controlled to match the energetic needs of the muscle. It is now well established that the primary energy intermediate in this process is ATP, as initially taught to us by Lohmann [see historical review published just before his death in 1978 (33)], supporting both muscle contraction as well as ion transport. Early on in working out the energy sources for muscle contraction, it was appreciated that the concentration of ATP, though clearly the potential energy intermediate between carbon substrates and work, is remarkably constant within the cell despite changes in ATP hydrolysis. Hill in his “Challenge to Biochemists” in 1950 (34) was puzzled with the role of ATP from data in intact muscle: “It may very well be the case, and none will be happier than I to be quit of revolutions, that the breakdown of ATP really is responsible for contraction or relaxation: but in fact there is no direct evidence that it is. Indeed, no change in the ATP has ever been found in living muscle except in extreme exhaustion, verging on rigor. This is explained by supposing that as soon as ATP is broken down into ADP and phosphate it is promptly restored”…….“If this happens after each stimulus, then the smallness of the changes involved and their quickness make it extremely difficult to gain any direct evidence on the subject.” At the time, Hill was focused on the Lohmann reaction (creatine kinase), discussed below. However, it took the inhibition of both creatine kinase and metabolism to demonstrate a change in ATP with muscular work from the Davies laboratory a decade later (35, 36) resolving this challenge. Thus the homeostasis of ATP can be maintained by the creatine kinase reaction or metabolism, which was subsequently demonstrated in the creatine kinase knockout mouse models as discussed further below. This phenomenon of a near constant ATP in skeletal muscle with physiological workloads was also observed in the heart for decades using conventional freeze clamp extraction assays (37–39). However, it was unclear what was happening to the phosphorylation potential since both the ADP and phosphate (Pi) were difficult to assay using these extraction techniques (40–42). The advent of 31P-NMR to noninvasively measure intact tissue phosphate metabolites (43) together with the use of enzyme equilibrium measures to estimate the chemical activity of ADP (44), allowed the extensive study of the effect of workload on phosphate metabolites using noninvasive physical methods. Approaching maximum respiratory rates, the entire pool lifetime of ADP is only 40–170 ms, while ATP is 2–10 s and mitochondrial NADH is 70–250 ms, making the freeze-clamp approach challenging in active tissues (45). In both heart and skeletal muscle, the original observation that the concentration of ATP was extremely well maintained has been well replicated in the literature. In most skeletal muscle types, a modest decrease in phosphocreatine (PCr) and increase in Pi is accompanied with an increase in work resulting in a concomitant increase in the calculated ADP and decrease in free energy for ATP hydrolysis while the ATP concentration ([ATP]) remains near constant below exhaustion levels of contraction (31, 46, 47). Although the creatine kinase reaction can transiently maintain ATP using PCr for a few seconds (48), the support of muscle [ATP] for sustained striated muscle work must come from metabolically generated ATP synthesis. Thus the regeneration of ATP via intermediary metabolism, as originally shown by Davies laboratory (35, 36), is critical for maintaining ATP constant within the cell. It is important to point out that with exhaustive exercise, decreases in [ATP] have been reported in some human subjects (32–34) associated with decreases in muscle oxygen content (49) consistent with compromised metabolism due to hypoxia during sustained intense exercise.

In the heart, metabolic homeostasis occurs over a wide range of physiological workloads. Focusing on in vivo cardiac studies, with physiological increases in workload, not only is ATP held constant but PCr and Pi are also unchanged, at the sensitivity of 31P-NMR, until near maximum experimental workloads are achieved across mammalian species (50–55). These studies have also been reproduced in healthy human volunteers (56, 57).

The ability of the heart, and to a lesser extent the skeletal muscle, to maintain metabolic homeostasis during increases in work is now a well-established phenomenon (58–60). The small alterations observed in even highly aerobic fibers when compared with the heart might be related to the large dynamic range of skeletal muscle energy demands compared with heart. However, the mechanism by which metabolic homeostasis is maintained in all muscle cells is still unknown. The classical model of a simple feedback of ADP and Pi to drive oxidative respiration and glycolysis (61–63) does not seem to be adequate to drive these processes without severe alterations in the kinetics of ATP and Pi utilization (for examples, see Refs. 64, 65) or compartmentation of substrates (see example Ref. 66). Other proposals suggest that there are parallel activation schemes where muscle contractile activity and metabolism are activated in parallel potentially via intracellular calcium (67–71). However, the dominance of calcium as a parallel regulator of OxPhos has been challenged by the survival and modest effect of removing the putative mitochondrial calcium transporter (MCU) in heart and skeletal muscle in the mouse (72–74), although MCU knockout mice are not born at the expected Mendelian ratios and some have indeed reported significant metabolic effects in the MCU knockout mouse (75, 76). However, the fact that a mouse whose heart operates near its maximum capacity at rest survives the removal of MCU, as well as creatine kinase and myoglobin discussed below, with modest changes in metabolic regulation suggests that the signaling network that supports muscle metabolic homeostasis is complex and likely does not depend on only one or two factors but an ensemble of signaling processes to maintain this critical process (77–79). It is clear that to accomplish this task a coordinated modulation of blood flow, substrate entry, substrate oxidation, and the entire OxPhos cascade needs to be activated to accomplish this rather remarkable bioengineering task. Fell and Thomas (77) and Korzeniewski (80–82) have presented theoretical models supporting this notion that the modulation of ATP production needs to occur over most of the steps in the reaction network. No single signaling mechanism like Ca2+ (69), AMPK (83), or even local metabolite (Pi, ADP, etc.) feedback (84) can likely coordinate these processes alone. Likely an integrated signaling network is responsible that we are just beginning to understand and will not be the focus of this review. Intrinsic to this process is the distribution of potential energy through the cell, which will be discussed further below.

The observed metabolic homeostasis first discussed by Hill (34) also has consequences with regard to the distribution of free energy in the muscle cell. That is, the kinetics of metabolically converted free energy distribution needs to match, or exceed, the rate of muscle cell ATP hydrolysis/synthesis and be done in such a way that the concentration of ATP does not change significantly. The complication here is that changes in metabolite diffusion rates require proportional changes in concentration gradients, although small diffusion distances, facilitated diffusion, and specialized gradient barriers could explain some of this phenomenon. However, the fact that large changes in ATP, ADP, and Pi flux occur in striated muscle without significant alterations in the concentration of these metabolites brings into question the role of metabolite diffusion in the regulation of overall energy conversion rates. Much of this review will focus on hypotheses involving a mitochondrial reticulum to distribute free energy in the form of the mitochondrial membrane potential that rapidly conducts through the muscle cell via a regulated mitochondrial reticulum thereby avoiding significant metabolite diffusion requirements.

3. METABOLIC SUPPORT DESIGN OF THE MUSCLE CELL

The heart needs to function, in the steady state, over a wide range of workloads and associated metabolic rates. This steady-state work is almost exclusively supported by the energy conversion occurring in OxPhos as illustrated by the small energy conversion capacity of glycolysis in the heart (85, 86). With this limitation, the maximum rate of ATP production by OxPhos should be matched to the maximum need for energy conversion in support of sustained myocardial contraction (i.e., myofibril activity) and control (i.e., ion transport) as well as basal maintenance of the myocyte [up to 30% of resting heart metabolism (87)]. Supporting this notion, the heart maximum rate of mitochondrial OxPhos, estimated from cytochrome oxidase (COX) content, essentially matches the maximum rate of respiration determined in the exercising animal (88, 89). These observations suggests that the design of the heart permits the delivery of substrates, oxygen and carbon metabolites, to not be rate limiting for OxPhos at maximum rates with little reserve capacity of OxPhos. These observations are consistent with the concept of symmorphosis (9–11) discussed above.

In contrast to cardiac muscle, which is designed to maintain energy homeostasis across nearly the entire range of contractile demands in the constantly beating heart, the design of the intermittently contracting mammalian skeletal muscle places greater emphasis on maximal contractile power at the expense of reducing oxidative energy metabolism. Consistently, whereas oxygen delivery is largely nonlimiting under physiological conditions in the heart due to high capillarization, relatively smaller cell sizes, and stable po2 gradients as discussed above, lower capillary densities and larger cell sizes in skeletal muscle fibers contribute to larger and more dynamic oxygen gradients from the capillary to the mitochondrion (90–95). As a result, the likelihood for oxygen delivery limitations is much greater in skeletal muscle cells and even more so in glycolytic compared with oxidative muscle fibers. Indeed, endurance exercise training in both rodents and humans has been reported to result in a twofold increase in skeletal muscle mitochondrial content, yet only ∼15% change in maximal oxygen uptake (96, 97). These data suggest that while mitochondrial content correlates well with performance on submaximal endurance tests (96, 98), mitochondrial content does not appear to be a major limitation to maximal oxygen uptake by the skeletal muscle cell (99, 100). The exact contributions of specific limiting factors to maximal oxygen uptake remain hotly debated, however (101–106). It is important to note that critical power, or the maximal sustainable skeletal muscle work rate mentioned above, generally occurs at ∼70–80% of the rate of maximal oxygen uptake in humans and thus may not face the same oxygen supply limitations. The primary components of the oxygen delivery system interacting directly with the muscle fiber, capillaries, and myoglobin will be discussed below. Recent in-depth reviews of oxygen delivery pathways upstream from the capillaries can be found elsewhere (3, 90, 107–109).

3.1. Major Muscle Cell Energy Conversion Processes

To understand the distribution of potential energy across the muscle, the sources of energy conversion to ATP need to be evaluated along with the topology of these sites in the cell. The primary sources of ATP during muscle contraction are creatine kinase, glycolysis, and OxPhos (FIGURE 1). Glycolysis and OxPhos provide the large majority of ATP during contractions lasting beyond a few seconds and will be the major focus of this section. However, discussion of creatine kinase will be included below as part of the facilitated diffusion section.

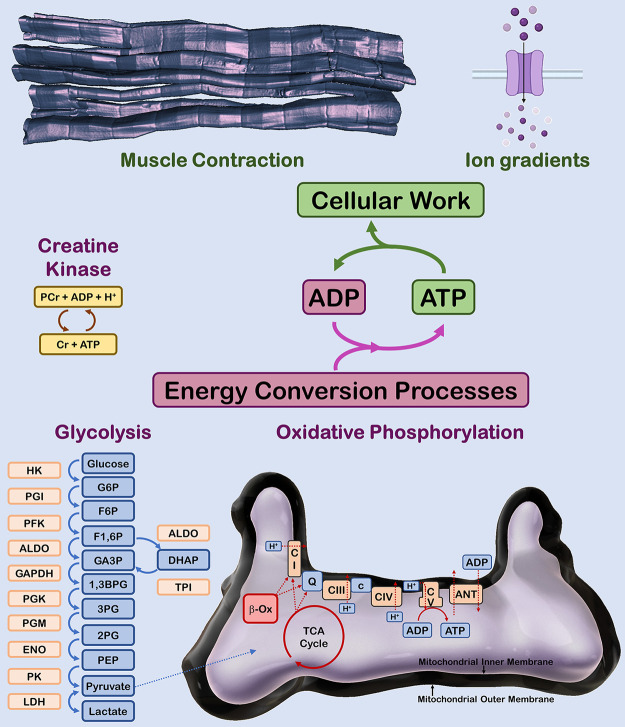

FIGURE 1.

Major adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production and utilization processes in striated muscle. Muscle contraction and maintenance of ion gradients across membranes are the major ATP utilizing work processes in striated muscle cells. Metabolic homeostasis is maintained by ATP production through the creatine kinase, glycolysis, and oxidative phosphorylation energy conversion processes. PCr, phosphocreatine; Cr, creatine; ADP, adenosine diphosphate; HK, hexokinase; PGI, phosphoglucose isomerase; PFK, phosphofructokinase; ALDO, aldolase; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; TPI, triose phosphate isomerase; PGK, phosphoglycerate kinase; PGM, phosphoglycerate mutase; ENO, enolase; PK, pyruvate kinase; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; G6P, glucose 6-phosphate; F6P, fructose 6-phosphate; F1,6BP, fructose 1,6-bisphosphate; GA3P, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate; DHAP, dihdroxyacetone phosphate; 1,3BPG, 1,3-bisphosphoglycerate; 3PG, 3-phosphoglycerate; 2PG, 2-phosphoglycerate; PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate; β-Ox, fatty acid β-oxidation; TCA, tricarboxylic; CI, complex I (NADH dehydrogenase); Q, ubiqinone; CIII, complex III (ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase); c, cytochrome c; CIV, complex IV (cytochrome oxidase); CV, complex V (ATP synthase); ANT, adenine nucleotide translocase.

With regard to the enzymes involved in the major energy conversion processes, it is reasonable to assume that protein content of an enzyme is a reflection of its relative maximum velocity based on the simplified Michaelis-Menten kinetics, where Vmax is assumed to be proportional to the concentration of the enzyme as Vmax∼kcat[E], where kcat is the enzyme rate constant that can depend on many parameters including pH, ions, allosteric interactions, and posttranslational modifications. However, with all of these modulators being equal, the enzyme concentration can be used to estimate the “potential” Vmax of the system (110–112). This is important for this review to understand the relative capacity of the different muscles to produce ATP together with the localization within the cell. The maximum velocity of enzymes, especially putative rate-limiting enzymes, has been used in the past to estimate the maximum ATP production of glycolysis [glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (113, 114), phosphofructokinase (115), and enolase (112)]. Some models have suggested other glycolytic enzymes could be rate limiting (114); however, at this stage, the essentially irreversible phosphofructokinase remains the primary candidate as a rate limiting step (116–118). While estimates of OxPhos have been made from enzymes of the citric acid cycle [oxoglutarate dehydrogenase (113)] or the electron transport chain [cytochrome oxidase (89, 119)], there does not appear to be a single rate limiting enzyme for OxPhos. Instead, control of flux through the OxPhos process is shared among nearly all of the enzymes (68, 120–122). It is important to note that the use of enzyme concentrations to estimate Vmax assumes that the kcat is the same for different tissues at maximumly stimulated workloads, but this is often complicated by different tissue isoforms with different kinetic properties as well as the artificial environment an enzyme is exposed to for in vitro studies (123). Even so, the value of this type of data has been well appreciated in the literature as numerous studies on the protein composition or enzyme activities of muscle tissues have been created (111, 124–135).

A challenge in the field has been to rely on the more difficult determination of absolute protein content rather than the relatively easy enzymatic activity of tissue extracts. Given the dependence of enzyme activity on the assay conditions and purification conditions (136), we have selected to use protein content measured with quantitative antibody or, preferably, physical measures such as mass spectrometry or optical spectroscopy to characterize the flux capacity of different muscle systems. Despite the extensive work on the protein content of muscle, a relational quantitative study of protein content in the three muscle types we are considering in this review, heart, slow-twitch, and fast-twitch muscles from a single species, is not in the literature. To help our analysis to assimilate data from many different sources, we created a relational database of the proteins of the rabbit heart, soleus (98% slow-twitch), and gracilis [99% fast-twitch (137)] muscles using standard contemporary mass spectrometry labeling techniques. While we only focus on the creatine kinase, glycolytic, and OxPhos enzymes here, although the other detected proteins will be provided in Supplemental Table S1 (see https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14109524.v1). We selected rabbit since it provided adequate sample for analysis, is one of the most extensively characterized muscle systems in the literature, and contains highly homogenous fast- and slow-twitch muscles (gracilis and soleus, respectively). In this comparison, we found over 3,000 proteins across the different tissue types using mass spectrometry (data presented in Supplemental Table S1). Again, we focus on the protein programming of these muscle cells for the metabolic energy conversion systems including putative facilitated diffusion systems such as creatine kinase. This analysis will use the extensive prior literature data together with the relational database in the rabbit to illustrate the protein programming associated with the overall energy conversion in striated muscle cells.

3.1.1. Glycolysis.

Glycolysis is an important energy source both in the form of ATP as well as for providing pyruvate for OxPhos. The relative database created for this review can be converted into a quantitative analysis of glycolysis using the baseline concentrations of glycolytic enzymes provided by Maughan et al. (125) of the free cytosolic proteins in the fast-twitch psoas muscle of the rabbit. This analysis is presented in TABLE 1. It has been noted by Maughan et al. (125), and others (111), that their values are considerably higher than prior work using primarily enzyme activities in extracts (138). We have selected to use Maughan et al. (125) for these analysis as they are the only quantitative physical measure of the glycolytic enzymes of the rabbit currently available.

Table 1.

Concentrations of glycolytic enzymes in rabbit muscles

| Glycolytic Enzyme | Soleus, µmol/L cell volume | Gracilis,* µmol/L cell volume | Heart, µmol/L cell volume |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glycogen Phosphorylase | 8 | 43 | 5.6 |

| Phosphoglucose isomerase | 5 | 29 | 9 |

| Phosphofructose kinase | 5 | 35 | 8 |

| Aldolase | 8 | 54 | 6 |

| Triose-phosphate isomerase | 20 | 82 | 13 |

| Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | 16 | 74 | 10 |

| Phosphoglycerate kinase | 30 | 131 | 20 |

| Phosphoglycerate mutase | 16 | 69 | 12 |

| Beta enolase | 15 | 108 | 12 |

| Pyruvate kinase | 11 | 78 | 7 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase† | 25 | 76 | 40 |

Gracilis data equated to rabbit psoas data from Ref. 125. †Lactate dehydrogenase concentrations are based on the sum of both the A and B isoforms.

Summing the mass of these proteins by grams of protein per liter cell, we find that the gracilis muscle has over 60 g of protein per liter cell devoted to glycolysis while the soleus and heart muscle have only 9 and 10 g/l, respectively. Using a protein density of 1.37 g/ml (139), this corresponds to ∼9% of the gracilis muscle cell volume is devoted to glycolytic enzymes while only 1–2% of the cell volume of the soleus and heart. Note that the remaining space is primarily consumed by myofilaments and mitochondria as discussed below, as well as sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR). These rather large differences reflect the known heavy dependence of the gracilis, a glycolytic fast twitch muscle, on the production of ATP from glycolysis when compared with soleus or heart muscle.

What is the maximum ATP conversion rates of glycolysis in these muscles? It is tempting to take the concentration of phosphofructokinase and its specific activity to arrive at a maximum velocity for glycolysis. However, this approach in the past has grossly overestimated the physiological fluxes observed. For example, Newshome and Crabtree (113) estimated from phosphofructokinase activity the maximum ATP production rate in the rat heart at 60 µmol ATP/min/g (corrected for temperature to 37°C). However, Kobayashi and Neely (85) found only ∼5 µmol ATP/min/g wt in rat heart while in the rabbit heart maximum glycolytic ATP production rate is ∼6 µmol ATP/min/g wt (140) [both calculations assume a wet/dry weight of 5.9 (141)] Similarly, the maximum glycolytic ATP production rates estimated from PFK activity in male and female human tibialis anterior muscle [∼180 and 140 µmol ATP/min/g wt, respectively (142)] exceed the measured maximal glycolytic rates in male and female human tibialis anterior muscles [∼60 and 30 µmol ATP/min/g wt, respectively (143)] by severalfold. Thus there is either significant reserve capacity in these enzymes under some conditions (115) or the extract assays do not reflect the true activities of these cytosolic enzymes (113, 115). This is likely even more important for many of the OxPhos enzymes that reside in a membrane with a very complex reaction environment including a membrane potential etc. As a result, we will consider the proteomics data to provide relative Vmax capacities, but they cannot, at this time, be used to estimate absolute fluxes.

3.1.2. Oxidative phosphorylation.

The mitochondrial protein content of the heart is clearly much higher than the other muscle tissues. Summing all of the mitochondrial proteins, we find that for the 304 highest abundance mitochondrial proteins, the ratio of mitochondrial proteins compared with heart was 36 ± 2 and 4 ± 0.1 for heart/gracilis and heart/soleus, respectfully. Due to the remarkable consistency in the ratios across tissues for these mitochondrial enzymes, the protein content for OxPhos has been simplified down to the levels of COX, the only irreversible step in the entire cascade from NADH to the terminal reduction of oxygen to water. Thus the content of COX serves as a good estimate of the OxPhos capacity of a system. We used the quantitative data on COX content in the rabbit heart from Phillips et al. (89) at 35 µmol/L cell volume and from Glancy and Balaban (144) at 12.2 and 1.9 µmol/L cell volume for the rabbit soleus and gracilis, respectively (TABLE 2). For reference, the relative COX abundance in each muscle type can also be calculated using our relational proteome database (Supplemental Table S1). Assessing the 14 COX subunits detected in each tissue yields a 21.7 ± 0.1- and 4.4 ± 0.0-fold greater COX concentration in the heart compared with the gracilis and soleus, respectively.

Table 2.

Concentrations of cytochrome c oxidase in striated rabbit muscle

| Protein | Soleus,† µmol/L cell volume | Gracilis,† µmol/L cell volume | Heart*, µmol/L cell volume |

|---|---|---|---|

| COX | 12.2 | 1.9 | 35 |

These data support the notion that the heart has the largest capacity for OxPhos when compared with the other striated muscle systems. Note that most of the enzymes associated with OxPhos are upregulated in the heart and soleus suggesting that the entire network cascade is required to provide more ATP from OxPhos. Moreover, it appears that all of the enzymes within mitochondria seem to be in proportion across the different muscle types as illustrated in FIGURE 2, A–C, for the top 152 abundant mitochondrial proteins, normalized to total tissue protein. The ratio of mitochondrial protein content is remarkably consistent with very few exceptions. The average ratio of mitochondrial protein expression was 0.3 + 0.01 for soleus/heart, 0.1 + 0.02 for gracilis/heart, and 4.8 + 0.2 for soleus/gracilis. The gracilis/heart data are plotted as heart/gracilis to condense the ratio axis. The tabulated data for these plots are presented in Supplemental Table S2 (see https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14109521.v1). The similarities in mitochondrial protein composition among striated muscles as shown here for the rabbit has also been observed in the pig with nearly identical protein expression profiles as assessed by two-dimensional (2-D) differential in gel electrophoresis (89, 144). Moreover, while endurance exercise training results in an increase in skeletal muscle mitochondrial content, the OxPhos protein content per mitochondrion remains relatively unchanged in both rats and humans (96, 97). In sum, these data are consistent with the notion that, with the possible exception of fuel preference (137, 144), the protein programming per mitochondrial volume is nearly constant across mammalian striated muscle, implying that content and structure are the primary methods of adapting to different maximum OxPhos velocity requirements in different muscle types. Possibly, the protein composition for ATP production is maximized per mitochondrion, and all that is left is modulation of content and location to regulate cellular ATP production capacity.

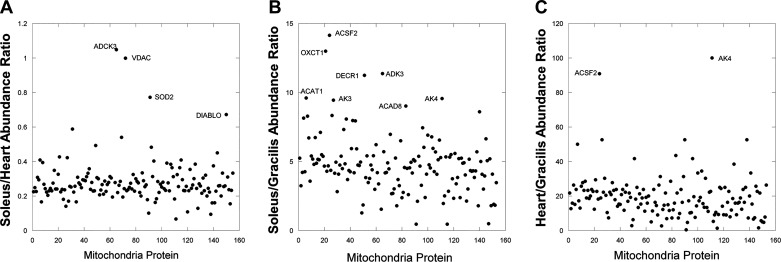

FIGURE 2.

Mitochondrial protein composition is remarkably similar across striated muscle types. Ratio of mitochondrial protein contents normalized to total protein content between tissues from whole muscle mass spectroscopy data. One-hundred fifty-two of the highest abundant proteins are plotted with labels applied to the proteins with large increases beyond the mean. All proteins are identified along with tabulated data in Supplemental Table S1. A: soleus muscle vs. heart. B: soleus vs. gracilis. C: heart vs. gracilis.

3.1.3. Specific power of energy conversion processes in muscle.

As muscle is a moving organic system, the specific power, or weight efficiency, of the energy conversion process used is important as moving the “weight” of the energy conversion system becomes one of the workloads of the muscle. Thus the higher the specific power of the energy conversion system, the more efficient the muscle can be in performing work. For example, the high specific power of the internal combustion engine, in comparison with the steam engine, made airplane flight possible (145). Using the data in the rabbit heart, we can total the glycolysis enzymes for ATP production to be ∼10 mg/gr wet weight (extrapolated from Ref. 125) and our relational proteomic data (Supplemental Table S1) that can support a realized rate of 5 µmol ATP/min/g heart resulting in 0.5 mmol ATP/min/g glycolytic enzymes. How does this compare with the weight/volume efficiency of OxPhos? The maximum rate of ATP production by OxPhos per gram of mitochondria (including associated water) can be estimated from the cytochrome oxidase (COX) content and maximum activity in intact heart mitochondria of ∼700 nmol O2/nmol COX/min (88, 146) or assuming 5.6 ATP/O2 then ∼4 µmol ATP/nmol Cox/min, which correlates with maximum in vivo rates of canines (88). In heart mitochondria, there are ∼1 nmol COX/mg protein (89) resulting in 4 µmol ATP/min/mg mitochondria protein. The mitochondria require an intact compartmentalized structure to function, in contrast to glycolysis; thus, to get the wet weight of mitochondria, the mass of mitochondrial lipid, water, and solutes must be accounted for. Mitochondrial protein makes up 25% of the total mass of mitochondria (147), so 1 mg protein is equivalent to 4 mg of mitochondrial wet weight. This results in 1 µmol ATP/min/mg wet weight or 1 mmol ATP/min/g compared with 0.5 mmol ATP/min/g in glycolysis calculated above. Assuming a free energy of hydrolysis (ΔGATP) of –64 kJ/mol of ATP, these values correspond to a specific power (kW/kg) of 1.1 and 0.5 for aerobic respiration and glycolysis in the heart, respectfully. The specific powers of skeletal muscle glycolysis (3.8 kW/kg) and aerobic respiration (1.7 kW/kg) are of similar magnitude (skeletal muscle calculations),1 although glycolysis appears to have greater specific power than OxPhos in the skeletal muscle. For reference the specific power of a V8 internal combustion engine is ∼0.65 kW/kg or close to the specific power of glycolysis in the heart. The weight efficiency of OxPhos and glycolysis are clearly very close within a factor of 3 taking into account the potential errors in this type of calculation including ignoring the water space associated with glycolysis.

Therefore, why pick localized mitochondrial OxPhos over the more distributed glycolysis or vice versa? The selection of energy source is much more complex than the simple specific power of the enzyme system. The complete oxidation of glucose to CO2 makes more efficient use of the entry of glucose and does not result in the generation of a high potential metabolic end product, lactate, that needs to be regenerated into glucose in the liver and kidney at a deficit to the net energy balance of the animal. That is, if the muscles only used glycolysis and lactate was converted back to glucose in liver and kidney for subsequent reuse, the body actually losses 4 ATP for each glucose oxidized (148) which is not sustainable. Thus lactate must be excreted, which is a huge loss of potential energy, or used as reducing equivalents in other regions of the body for OxPhos. This later constraint is likely a reason that the heart prefers plasma lactate for oxidation over almost all other substrates when present in high concentration in the blood (149, 150). Another reason may well reside in the structural requirements of glycolysis versus OxPhos. Glycolysis is believed to be partially compartmentalized but is clearly in the freely soluble cytosolic fraction permitting tight packing within the myofilaments. Also, being free in the cytosol reduces the impact of internal shear forces of the muscle that the mitochondria could be susceptible to as complex organelles. As the muscle reduces longitudinal length and thickens upon contraction, shear on the highly compliant mitochondria is potentially generated in both the short and long axis. One compensatory mechanism is to place mitochondria where internal shear is minimized such as the I-band, Z-disk, or subsarcolemmal regions of the cell. Another is to have the mitochondria move with the myofilaments in both dimensions by being directly attached to the myofilaments, thus shortening and thickening with each contraction. Evidence is available that cardiac mitochondria do remain attached to the sarcomere, shortening and thickening with each contraction and retaining their relationship with the sarcomere (151). The connection to the sarcomere may be through the intermediate fibers of desmin together with plectin (152). The impact of this reshaping of the mitochondria on each contraction has not been extensively explored. Overall, the mitochondria require dedicated space that is difficult to locate within the muscle without the sacrificing cross-sectional area of the contractile apparatus needed to maximize power, and specific placement of mitochondria may result in exposure to shear forces as mentioned above. Finally, OxPhos resulting from fatty acid fuel sources, as is most common in the heart (153, 154), also requires displacement of myofibrils or other cellular structures to make room for lipid droplets, which are often tightly coupled to mitochondria. This aspect of the topology of the energy conversion systems will be discussed further in section 3.2.3.

3.2. Energy Distribution Processes of the Muscle Cell

In addition to the content and composition of the energy conversion processes as discussed above, the energetic design of a cell must also take into account the distribution of the inputs, intermediates, and outputs involved in the energy conversion processes (155). Thus, in the relatively large and densely packed muscle cell, the distances between the participating structures as well as the processes regulating the movement of metabolites and ions between them play a particularly important role in determining the energetic support capacity of the cell. To limit the scope of this section of the review, we will focus on the delivery of oxygen from the capillary to mitochondria, the distribution of electrical potential energy within mitochondria, and the delivery of ATP from mitochondria to cellular ATPases. Thorough discussion of substrate metabolism in muscle cells can be found elsewhere (4, 6, 156–158).

3.2.1. Capillary structure and blood flow.

One of the primary requirements to support OxPhos is to provide oxygen. To support the supply of oxygen, the heart is highly vascular with a remarkable density of capillaries between 2,500 and 4,500 capillaries/mm2 (159–164), which are nearly evenly spaced every 12 to 22 μm (162, 164–166) consistent with the average diameter of a heart cell (163). These densities suggest that each heart cell is in contact with one or more supporting capillaries. This is consistent with the three-dimensional electron microscopy studies (167, 168) revealing a capillary associated region within most cardiac myocytes. Adjacent to these capillaries is a slightly higher density of mitochondria (159) within the paravascular pool (167), although not as well developed as in the skeletal muscle (169). Thus the capillary network is well designed to deliver blood and associated oxygen and substrates to essentially every cell in the heart wall.

To support the high level of OxPhos, the coronary blood flow is relatively high and linearly balanced with the workload (170) maintaining a low venous po2 (∼18 Torr) over much of the workload range (171). The mechanism of how coronary flow is precisely matched to oxygen demand remains a major question in cardiac physiology and likely relies on multiple and redundant mechanisms across varying spatial scales for this absolutely critical function in the heart and the body (7, 171–173). The net result is a highly dynamic system providing an appropriate amount of oxygen, maintaining a near constant venous po2, and meeting the oxygen delivery needs of the heart through a dense feeding capillary network.

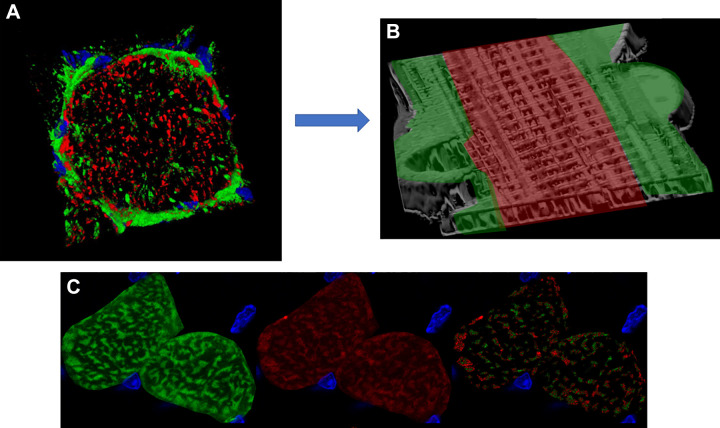

The capacity of capillaries to deliver oxygen to skeletal muscles has been of great interest (174–178) since August Krogh’s Nobel Prize winning work (179) on the regulation of oxygen diffusion in muscles roughly a century ago. Capillary density can vary greatly in skeletal muscles from ∼250 to 1,500/mm2 of muscle volume with oxidative muscles containing up to twice the number of capillaries per unit volume and ∼33% higher capillary to muscle fiber ratio (∼2.0 vs. 1.5) (175, 177, 178, 180, 181). While capillary-to-fiber ratio and capillary density have been commonly measured on 2-D images for decades and often, but not always, correlate well with muscle oxidative capacity (174–178, 180, 182–184), how the capillary interacts with the muscle fiber also plays a major role in the diffusion capacity between these structures. Indeed, measures that incorporate the geometry of capillary-fiber interactions, either in 2-D or 3-D, have become more prevalent and better correlate with mitochondrial content across both oxidative and glycolytic muscle types across a variety of conditions (175, 176, 185–192). Thus the overall structural capacity for oxygen delivery from capillaries to within the skeletal muscle fiber is dependent on 1) the number of capillaries in proximity to the cell, 2) the direct surface area contact between capillaries and the muscle fiber, and 3) the cross-sectional area of the cell. As mentioned above, more oxidative muscles are smaller, have greater capillary densities, and have greater capillary surface area contact than more glycolytic muscles. However, most muscles, particularly in humans, are comprised of heterogeneous groups of both oxidative and glycolytic muscle fibers with the relative proportion of each determining the overall metabolic phenotype of the whole muscle (182, 193). This heterogeneity results in adjacent oxidative and glycolytic muscle fibers each with different demands for oxygen delivery along their shared borders, and often, oxidative fibers can be surrounded by several glycolytic fibers. The incongruous demand for oxygen to oxidative fibers adjacent to glycolytic fibers may be met by placing capillaries in grooves in the sarcolemma of the more oxidative cell (194). Embedding capillaries atop only one of the two adjacent fibers allows the capillary surface area contact to be increased to one but not the other fiber (FIGURE 3, A–D) and thus offers another level of control when designing the structural capacity for oxygen delivery to the muscle cell within heterogeneous tissues. Much remains to be discovered regarding these capillary grooves such as how and when they form during muscle development as well as more precise information on their contribution to oxygen delivery capacity to muscle cells. It is clear, however, that these grooves in the sarcolemma are true physical structures and not just the result of capillary compression of the cell membrane, as sarcolemmal grooves remain visible in isolated live muscle fibers even after removal of the adjacent capillaries (FIGURE 3C). How or whether the composition of the sarcolemma is altered in this region has yet to be determined, although we speculate that receptors or transporters, which interact with substrates carried in the blood may be upregulated in sarcolemmal grooves relative to the rest of the membrane to increase the efficiency of intercellular signaling and/or transport processes.

FIGURE 3.

Capillary embedding within sarcolemmal grooves provides additional control over oxygen delivery capacity to specific muscle cells. A: schematic figure of a capillary located between a glycolytic (top) and oxidative (bottom) muscle fiber. Mitochondria and nuclei locate laterally to the capillary sitting in a sarcolemmal groove and increasing surface area contact with the oxidative fiber. Adapted from Ref. 194. B: 3-dimensional (3-D) rendering of mitochondrial structure in an intact Tibialis anterior muscle cell showing voids where capillary grooves (C) and nuclei (N) are located. Adapted from Ref. 169. C: 3-D rendering of mitochondrial structure in an isolated, live soleus muscle fiber. Grooves in the sarcolemma remain even after removal of capillaries through collagenase digestion. Adapted from Ref. 169. D: transmission electron microscopy image of a capillary (white arrow; IMF, intermyofibrillar; PV, paravascular) embedded in a sarcolemmal groove in the upper but not lower muscle fiber. RBC, red blood cells. Adapted from Ref. 194.

Similar to the dynamic nature of skeletal muscle contraction, the rate of blood flow can increase more than an order of magnitude from rest to exercise (195) and occurs fast enough that oxygen delivery to the muscle does not appear limiting at the onset of exercise in healthy populations (195–198). Despite the large, rapid increase in oxygen delivery at the onset of exercise, the increased contractile rate of the muscle cells during even moderate exercise results in a fall in the mean po2 in both the capillaries (∼35 to 24 Torr) and interstitial space between capillaries and muscle fibers (∼16 to 7 Torr) (90, 92). Together with the similar magnitude fall reported for intramuscular po2 from ∼10–15 Torr at rest to 2–5 Torr at exercise intensities ranging from moderate to severe (91, 199–201), it has been suggested that exercise does not alter the oxygen pressure gradient from the capillary to mitochondria as previously thought (90, 202). Instead, the diffusion constant for oxygen (do2), analogous to its conductance, appears to increase severalfold to account for the increased oxygen flux (90, 202), although the precise mechanisms behind this change remain to be resolved. What is clear is that blood flow to the skeletal muscle is tightly regulated through several related and likely overlapping mechanisms, which provide precise control over oxygen delivery across the wide range of skeletal muscle contractile demands.

3.2.2. Cytosolic facilitated diffusion processes.

Due to the metabolic rates and distinct compartmentation of the ATP-utilizing and -producing machinery in muscle, as well as the observed metabolic homeostasis limiting large metabolite gradients, it has often been suggested that simple metabolite diffusion is inadequate to support this highly active structure (203). The two major cytosolic facilitated diffusion systems that have been the focus of extraordinary effort are creatine kinase for ATP and ADP (204–208) and myoglobin for oxygen (8, 209–212). These two mechanisms will be discussed below as they represent the classical view of energy distribution in the muscle cell.

3.2.2.1 myoglobin.

In addition to the dense capillary network with only 20 or so micrometers separating each capillary run, the heart also contains myoglobin that can serve as a parallel facilitated diffusion pathway for oxygen (8). Although myoglobin in diving animals is believed to provide an oxygen reserve for diving (213), the low concentration in land animals would only support OxPhos for seconds during a hypoxic event (214, 215). Thus a role as an oxygen reserve in most nondiving mammals is believed to be very small. However, the relatively high concentration of myoglobin relative to oxygen suggested it might play a role in facilitated diffusion. The demonstration of facilitated oxygen diffusion by an oxygen binding protein was first described for hemoglobin and/or myoglobin by several investigators early in the 1960s (209–212) with an early suggestive abstract by Wittenberg (209). This was then developed into a detailed model of myoglobin facilitated diffusion within muscle in a classic paper in Physiological Reviews (8). The concept of myoglobin facilitated diffusion is basically that myoglobin can provide a parallel diffusion pathway for oxygen through the gradients in oxy- and deoxymyoglobin. Myoglobin facilitated diffusion depends on several factors: first, myoglobin affinity for oxygen is intermediate between the relatively low nonlinear affinity of hemoglobin and high-affinity cytochrome oxidase, thus facilitating the transfer from low- to high-affinity sites reflected in hemoglobin/myoglobin and myoglobin/cytochrome oxidase transfers of oxygen. Second, myoglobin is relatively small and is nearly freely diffusible in the cytosol (216, 217). Third, depending on the tissue (218), myoglobin is in sufficient concentration, significantly higher than molecular oxygen, to provide a viable diffusion driven oxygen transfer mechanism. However, based on the concentration and diffusion coefficient measured by two independent physical measures, fluorescence (216, 219) or NMR (220), the contribution of myoglobin diffusion to oxygen transport has been suggested to be <10% even under extreme conditions (203, 219, 220). One of the key aspects of the facilitated diffusion mechanism with myoglobin is that gradients in oxy-and deoxymyoglobin, as well as oxygen, need to exist for this passive facilitated pathway to contribute to oxygen distribution in the muscle cell. We will address this key measure, in vivo, below.

The normal venous po2 of the heart, depending on the impact of arterial-venous shunting (221), can represent an upper limit for the end capillary po2, which would put the oxygen tension well above the consensus affinity for cytochrome oxidase under most conditions (7). Indeed, taking the structure of the capillary system and assuming very simple Krogh type diffusion models (222, 223), it has been predicted that within the heart cell, the oxygen tension should greatly exceed the COX P50 for oxygen with a capillary to muscle cell gradient of only 1 or 2 Torr. However, several lines of evidence suggest that the tissue po2 may be much lower than the capillary geometry, venous po2, and models would imply. The initial evidence was with small oxygen-sensitive electrodes plunged into the tissue and recording the distribution of oxygen tensions over a large number of insertions (224). These results provided evidence that a significant fraction of the tissue was well below the po2 of the venous blood. The interpretation of these results ranged from selective barriers to oxygen at the capillaries (222, 225), capillary perfusion heterogeneity (226), and various measures in isolated perfused hearts with questionable extrapolation to in vivo conditions (227). Numerous studies have shown that the saline-perfused mammalian heart with this low-oxygen content but high flow rate, is hypoxic under most experimental conditions using a variety of techniques (228, 229). Since this review is focused on the in vivo condition, the saline perfused mammalian heart will not be considered further here.

Two independent studies in 1999 using noninvasive NMR (230) or optical spectroscopy (223) measures in the heart of the average myoglobin oxygenation, in vivo, detected little or no deoxymyoglobin under normal physiological conditions even approaching maximum workloads. With ischemia or low flow conditions, deoxymyoglobin was easily detected (223, 230). These independent studies supported two important conclusions: 1) that the average oxygen tension in the heart in vivo exceeded the oxygen P50 of myoglobin, consistent with earlier model predictions; and 2) that myoglobin facilitated diffusion of oxygen does not participate in oxygen distribution in heart muscle under normal conditions since no deoxymyoglobin was detected for a driving a diffusion gradient for oxy-myoglobin. These data suggest that the earlier invasive microelectrode studies were not reflecting the true average tissue oxygen tension while the saline perfused hearts were intrinsically oxygen deprived (224, 228, 229). However, under conditions where the capillary po2 drops, deoxymyoglobin is formed consistent with a potential role for myoglobin facilitated diffusion under these conditions. These observations are consistent with several models that suggested myoglobin facilitated diffusion would only occur under severe anoxic conditions (216, 231). These data also suggest that the heart was designed to supply all the oxygen the mitochondria need to support near maximal work without being oxygen limited.

More recently, genetic knockout experiments have demonstrated that the presence of myoglobin is not necessary for near normal function in the mouse (232, 233). This is particularly surprising in the mouse that operates within a factor of two of its maximum cardiac output while at rest suggesting it is operating near its maximum demand for oxygen nearly all the time (234). The degree of molecular adaptation to myoglobin knockout seems to be controversial with modifications ranging from changes in capillary density (233) and nitric oxide handling (235) to no change in capillary structure and protein expression in heart and skeletal muscle (194). Thus, if any modifications occurred in the myoglobin knockout mouse, they are likely small.

Based on these different lines of evidence, the role of myoglobin in the normal distribution of oxygen in the heart is believed to be minimal. Again, even at maximum workloads, there is little evidence that myoglobin plays a critical role in the delivery of oxygen across the heart (223, 230) even under hypertrophic heart conditions (236). These results coupled with new experiments on other roles of myoglobin have led to other hypotheses for the large investment in myoglobin protein in the mammalian heart (237) and oxidative muscle with the most prevalent being the metabolism of free radicals or nitric oxide (237–239). These new roles for the high concentration of myoglobin in the heart and skeletal muscle are currently an active area of research.

The fact that deoxymyoglobin has not been detected in the working heart in vivo suggests that the vascular-cellular geometry, together with the highly regulated coronary flow results in an oxygen tension in the cell that far exceeds the consensus affinity for oxygen for OxPhos. Thus it is our conclusion that oxygen is not rate limiting for energy conversion under most physiological conditions in the heart. This suggests that the extensive capillary network and regulation of blood flow is capable of keeping the cellular oxygen content well above the P50 of myoglobin and cytochrome oxidase under most conditions using pure oxygen diffusion mechanisms. A specialized system to support molecular oxygen delivery beyond the extensive capillary system does not seem to be necessary in the heart.

The putative oxygen facilitated diffusion system through myoglobin discussed above for the heart is also present to some degree in skeletal muscle fibers (240). Oxidative fibers contain large concentrations of myoglobin, albeit less than in the heart, capable of maintaining a viable diffusion driven oxygen transfer mechanism whereas glycolytic fibers are generally considered to have insufficient myoglobin for facilitated diffusion to contribute significantly (240). Unlike the cardiac tissue, deoxygenated myoglobin can begin to be detected in humans by NMR during exercise at ∼50% of maximal oxygen uptake (moderate exercise) (91, 201) implying oxy/deoxymyoglobin gradients may be present within the skeletal muscle cell. However, increasing the intensity of exercise in these NMR studies all the way up to 100% of maximal oxygen uptake either under normoxia or hypoxia did not lead to further deoxygenation of myoglobin. Although a similar NMR study did find progressive deoxygenation of myoglobin with exercise intensity (200), both groups reported ∼50% myoglobin deoxygenation during exercise at maximal oxygen uptake resulting in a calculated intracellular po2 of ∼3 Torr similar to the values obtained using biochemical methods (94). Even with the lower intracellular po2 compared with cardiac cells, the po2 values in skeletal muscle cells appear to remain above the threshold, which would begin to limit oxygen consumption by mitochondria (P50 <1 Torr) (93, 241–243). Indeed, in vivo spectroscopic measurements resolving myoglobin and hemoglobin individually in mouse skeletal muscle revealed that oxygen consumption was not limited by oxygen availability across the physiological range of intracellular po2 values (93) supporting the conclusion that oxygen does not play a regulatory role in skeletal muscle respiration under physiological conditions. Together with the lack of effect of myoglobin knockout on exercise capacity in mice (232), these data suggest that myoglobin does not play a significant role in oxygen distribution in skeletal muscle cells under normal conditions. However, further investigations into the myoglobin knockout mice have revealed an important role of myoglobin in nitric oxide signaling (244, 245), which supports the hypothesis that myoglobin may act as a protective shield for mitochondrial respiration by scavenging nitric oxide, a known inhibitor of cytochrome oxidase (246, 247).

In summary, current evidence suggests that the oxygen concentration gradients driving oxygen delivery through the striated muscle cell do not result in oxygen concentrations that become rate limiting for OxPhos under submaximal conditions in the heart or skeletal muscle. It should be stressed that a near maximum workloads, difficult to replicate in the laboratory (54), myoglobin-facilitated diffusion may contribute to oxygen delivery as direct measures of myoglobin oxygenation under conditions of maximum exercise-induced cardiac output, in vivo, have not been attained in contrast to contracting skeletal muscle (91, 200, 201).

3.2.2.2. creatine kinase.

Creatine phosphate (PCr) was one of the first “high energy” phosphate metabolites found in muscle (248, 249), and its breakdown with muscle contraction (248) and ability to support muscle action in the absence of glycolysis (250) supported the early notion that PCr could actually be the high energy molecule supporting muscle contraction. However, it quickly became apparent that PCr had these functional properties due its rapid exchange of high energy phosphate bonds with ADP creating the primary source of muscle contraction, ATP, through the reversible Lohman (251) reaction catalyzed by creatine kinase:

MgADP + PCr + H+ MgATP + Cr (Keq = 100: 1 mM Mg2, pH 7.0) (252)

This reaction is believed to be operating near equilibrium in heart and skeletal muscle based primarily on two independent measures: 1) The concentrations of reactants and cofactors (i.e., PCr, ATP, H+, Cr, and Mg2+) appear to be poised near the creatine kinase equilibrium (44, 253, 254); and 2) the unidirectional flux through this “dead end” (i.e., Cr and PCr are not rapidly used for any other reaction) measured using 31P-magnetization transfer methods, far exceeds the calculated ATP turnover rate (255–258). Thus ATP, ADP, Cr, and PCr are believed to be at near equilibrium concentrations in mammalian muscles under most experimental conditions. Additionally, creatine kinase is one of the most abundant proteins in the cytosol, although its concentration varies according to muscle fiber type (TABLE 3). With the high concentrations of creatine kinase, Cr, and PCr coupled with this rapid exchange process, it quickly became clear that the PCr pool could serve as a short term spatial and temporal “buffer” for ATP when ATP production could not keep up with ATP utilization (260). With [PCr] only exceeding [ATP] by twofold in heart (261) and fourfold in muscle (262), this buffer capacity is quite small considering that the turnover of ATP at high workload is only a few seconds in heart (263). Thus, for short temporal mis-matches in ATP production and utilization, the rapid creatine kinase reaction could maintain ATP (264) even with the net production of Pi reducing the free energy of ATP hydrolysis (265, 266).

Table 3.

Concentrations of creatine kinase in striated rabbit muscle. Values are µmol/L cell volume

| Protein | Soleus,* µmol/L cell volume | Gracilis,† µmol/L cell volume | Heart,† µmol/L cell volume |

|---|---|---|---|

| Creatine kinase | 10.4 | 20.6 | 7.0 |

*Rabbit soleus value from Illg and Pette (259). †Rabbit heart and gracilis calculated from relational proteome database using the abundance ratios of the sum of cytosolic creatine kinase isoforms.

Once the buffering power of PCr was realized to be minimal, another more sustained impact of creatine kinase on maintaining the spatial distribution of free energy in ATP was proposed by Bessman and coworkers in a series of papers (204–208) describing the creatine kinase shuttle where the topology of the creatine kinase enzyme at the mitochondria and the myofibrils facilitated the conversion of ATP + Cr to PCr + ADP at the mitochondria and PCr + ADP to ATP + Cr at the myofibrils. Due to the aforementioned higher concentrations of PCr when compared with ATP, and especially Cr when compared with ADP, this resulted in a potential for facilitated diffusion through the cytosol (267). That is, PCr facilitated the diffusion of the high energy phosphate bond from ATP created at the mitochondria to the myofibrils while the diffusion of the low energy substrate ADP, in micromolar concentrations, was greatly enhanced by the mM concentration of Cr. This proposal suggested that the creatine kinase reaction is not just a short-term buffer for high-energy metabolites but also plays a role in the distribution of the potential energy and reaction intermediates required for energy conversion in the muscle cell. The creatine kinase shuttle has been a major focus in muscle energetics since the Bessman proposal and has been the topic of numerous reviews (204, 263, 267–273), although many have questioned the extent of cytosolic energy distribution dependent on this shuttle, especially in the heart, for various quantitative and experimental considerations (203, 267, 271, 274–277).

Numerous investigators have repeated the classical work of Jacobus and Lehninger (278) demonstrating that isolated muscle mitochondria will preferentially generate PCr when given ADP, Pi, and creatine at reasonable physiological concentrations (279). This is a fundamental element of the creatine kinase shuttle that ATP is converted to PCr at the mitochondria and both the ATP and PCr are available for diffusion through the cytosol in a parallel path. There is a muscle creatine kinase isoform in the mitochondrial intermembrane space to perform this task (280, 281). At the myofibrils, the creatine kinase converts the ADP generated by the contractile and ion transport ATPase to Cr. Due to the equilibrium of the creatine kinase reaction, most of the ADP will be rapidly transferred into Cr providing a potentially large gradient in Cr from the ATPase sites to the mitochondria to be used in the mitochondrial creatine kinase reaction. Although this is an attractive theory, and simply based on facilitated diffusion arguments (267) should supplement the distribution of energy across the muscle cell, several observations bring the net importance of this process into question. In the heart, over large variations in workload in vivo, there were little or no changes in PCr concentration ([PCr]) or by mass balance arguments Cr concentration ([Cr]), until near maximum cardiac workloads were attained (50, 282–288). No changes were also observed transiently with work jumps (282). Diffusion, or a metabolite shuttle, relies on changes in the concentration gradients of the metabolites to change the rate of flux. Since [Cr] and [PCr] do not change significantly over physiological workload in heart, in vivo, this suggests that alterations in these facilitated diffusion pathways are not playing a dynamic role in matching the rate of ATP production with ATP utilization as first predicted by Hill (34). A more likely hypothesis is that the energy distribution system of the cell greatly exceeds the energy requirements throughout the cell below Vmax without requiring significant changes in steady state concentrations of any metabolite. However, as maximum workloads are approached, numerous systems become limiting from blood flow to energy conversion (9–11).

Another line of in vivo evidence against a baseline role for the creatine kinase shuttle mechanism of energy distribution has been the evaluation of different types of creatine kinase (289–295) or creatine (274) knockouts in mice. The mouse provides an excellent model for evaluating energy distribution in the heart due to its remarkably high baseline metabolic rate (89, 234) setting energy demands near maximum even at rest. Creatine kinase knockout studies have revealed very modest changes in the performance or protein programming of these animals suggesting a potentially secondary role of creatine kinase shuttle in supporting energy distribution in the mammalian striated muscle system. This conclusion is strongly supported by the recent review from the Dr. Weiss laboratory that concluded: “…….31P MRS studies in CK-deficient hearts suggest that CK does not play an obligate intracellular transport role in the normal mouse heart and that its presence is not critical for baseline contractile function in normal hearts.” (275). We agree with this conclusion based on theoretical concerns and the experimental results including biophysical measures and genetic knockout experiments.

3.2.3. An alternative to metabolite facilitated diffusion: the muscle mitochondrial reticulum.

As discussed above, the concept that facilitated diffusion of metabolites or oxygen supporting normal muscle function has been challenged over the last several decades based on theoretical ground, genetic modifications and the observation of a metabolic homeostasis of the metabolites involved. Another possible mechanism to rapidly distribute energy across the cell from OxPhos is the mitochondrial reticulum with its high conductance only requiring small gradients in potential energy throughout the cell (169, 296). Thus the actual structure of the mitochondrial network may provide an additional mechanism for intracellular distribution of potential energy within the muscle cell. The following sections will address our current understanding of muscle mitochondrial network structure and several remaining questions surrounding how the mitochondrial reticulum may contribute to and regulate cellular energy distribution in striated muscle.

3.2.3.1. initial observations of muscle mitochondrial structures.

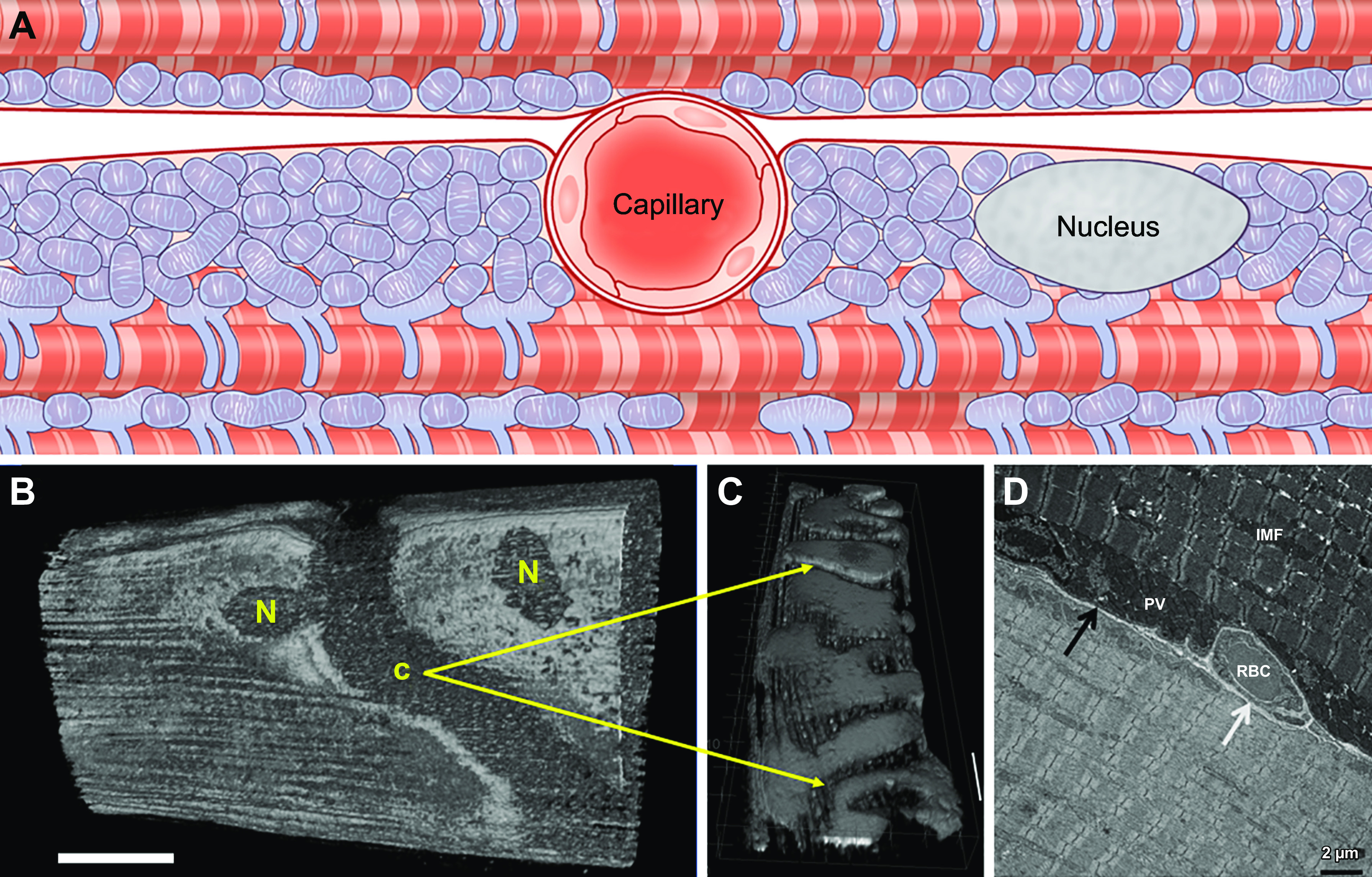

Mitochondria in striated muscle were first visualized roughly 180 years ago by Schwann (297) and Henle (298) who each described them as “granules” located between the myofibrils as well as near the nuclei (FIGURE 4A) of skeletal muscle cells. The description of these interstitial granules was extended by Kolliker (305, 306) who found that they varied across different species and muscle types in addition to demonstrating their capacity for swelling under different osmotic conditions and speculating a relationship with metabolism. Knoll (307) provided perhaps the most detailed descriptions of interstitial granules within cardiac muscle cells around this time, demonstrating the alignment of many granules between the myofibrils in a variety of species. In 1890, the terms “bioblast” and “sarcosome” were coined by Altmann (308) and Retzius (309), respectively, to describe what are now known as mitochondria in the muscle, with Altmann considering the bioblast to have metabolic and genetic autonomy within the cell. The term mitochondria was coined by Benda in 1898 (310) to describe both the thread-like and granular nature he observed for these organelles, and soon after mitochondria, bioblasts, and sarcosomes were all confirmed to be the same as the granules initially described by Schwann (311, 312). However, the term sarcosome persisted into the 1960s (313–315) and was sometimes described as a separate structure from mitochondria (316). It is also interesting to note that many investigators in this era believed that mitochondria could transform directly into myofibrils, although this was largely attributable to nonspecificity of the staining techniques used at the time (317). Overall, the early studies up through 1920 found that mitochondria in striated muscles were generally located around the nuclei, between the myofibrils along the anisotropic (A)-bands, and/or at the end of each sarcomere in the isotropic (I)-band region of the muscle fiber with A-band mitochondria being the predominant type in oxidative and cardiac muscle and I-band mitochondria more abundant in glycolytic muscle types.

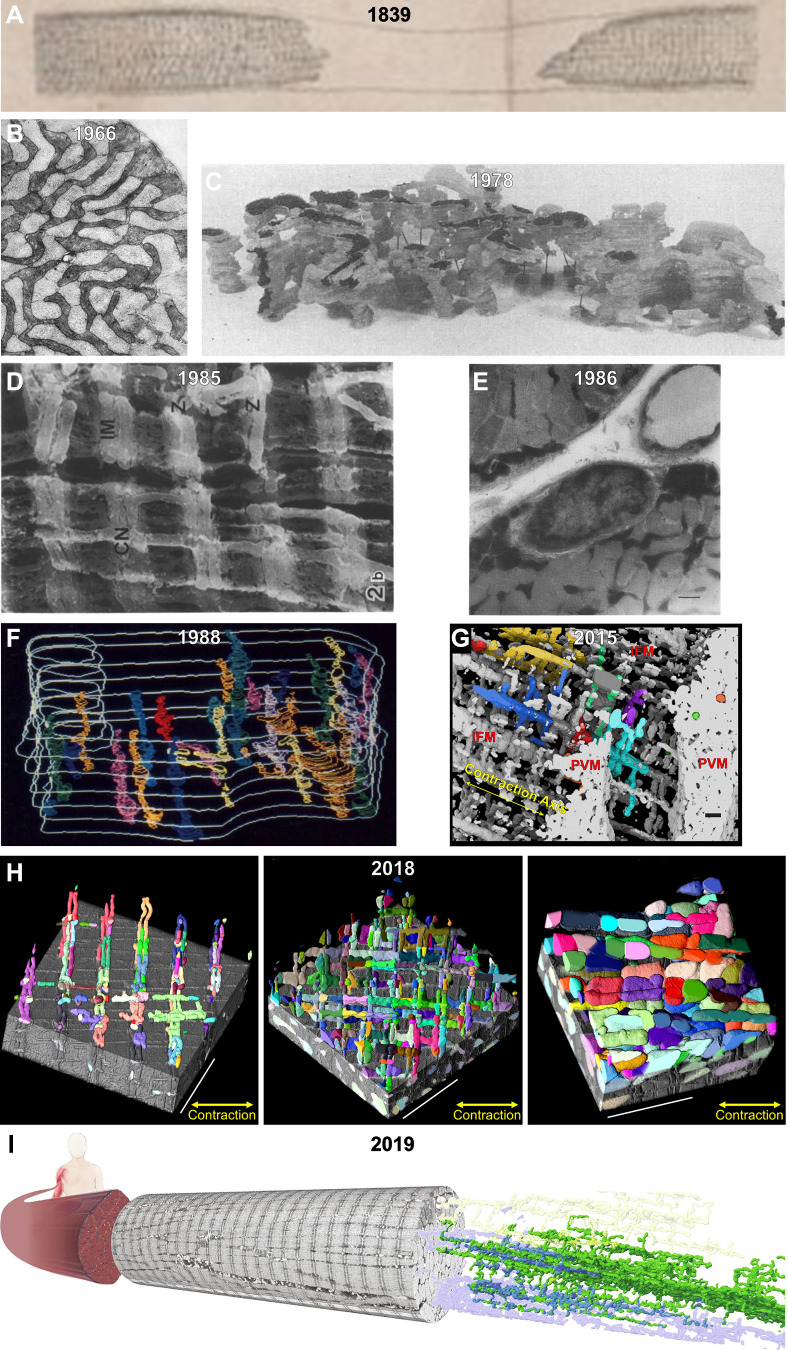

FIGURE 4.

A visual history of muscle mitochondrial reticulum structure. A: interstitial granules within a muscle cell imaged through a light microscope in 1839 (297). B: cross-sectional 2-dimensional image of the mitochondrial reticulum in rat diaphragm oxidative muscle imaged by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) in 1966 (322). C: 3-dimensional (3-D) rendering of the rat diaphragm oxidative muscle mitochondrial reticulum imaged by serial section TEM in 1978 (299). D: scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image of the rat hindlimb oxidative muscle mitochondrial reticulum from 1985 (300). CN, thin mitochondrial column; IM, I-band limited mitochondria; Z, Z-disk. E: high-voltage TEM projection image of rat hindlimb muscle mitochondrial reticulum in 1986 (301). F: 3-D rendering of horse muscle mitochondrial reticulum imaged by serial section TEM in 1988 (302). G: 3-D rendering of the oxidative mouse muscle mitochondrial reticulum imaged by focused ion beam (FIB)-SEM in 2015 (169). H: 3-D renderings of the mitochondrial reticulum in glycolytic (left), oxidative (middle), and cardiac (right) mouse muscles imaged by FIB-SEM in 2018 (303). IFM, intrafibillar mitochondria; PVM, paravascular mitrochondria. I: 3-D rendering of the human oxidative muscle mitochondrial reticulum imaged by FIB-SEM in 2019 (304).

3.2.3.2. origins of the muscle mitochondrial reticulum.

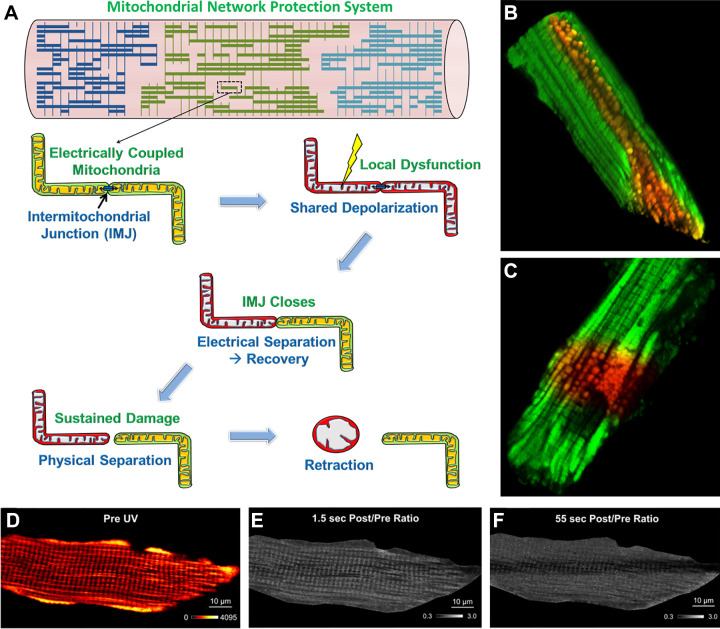

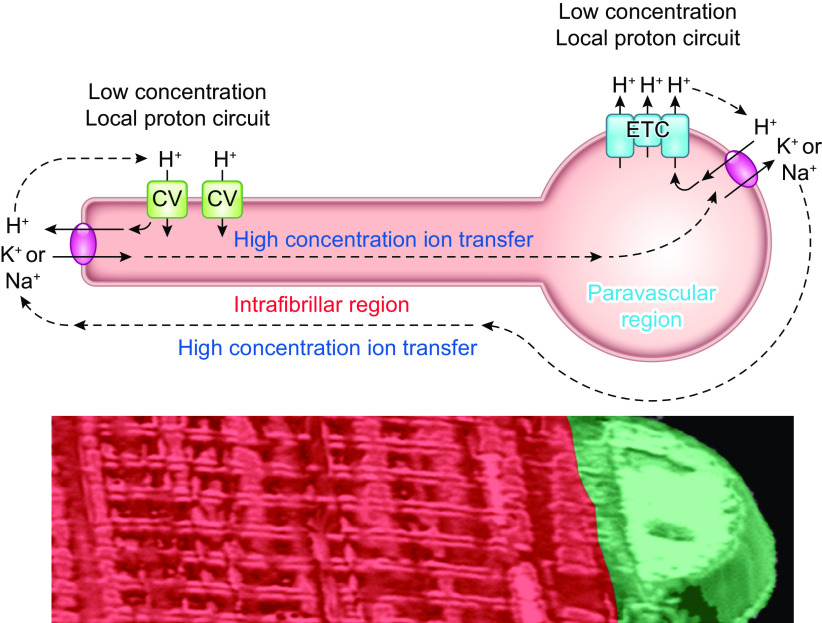

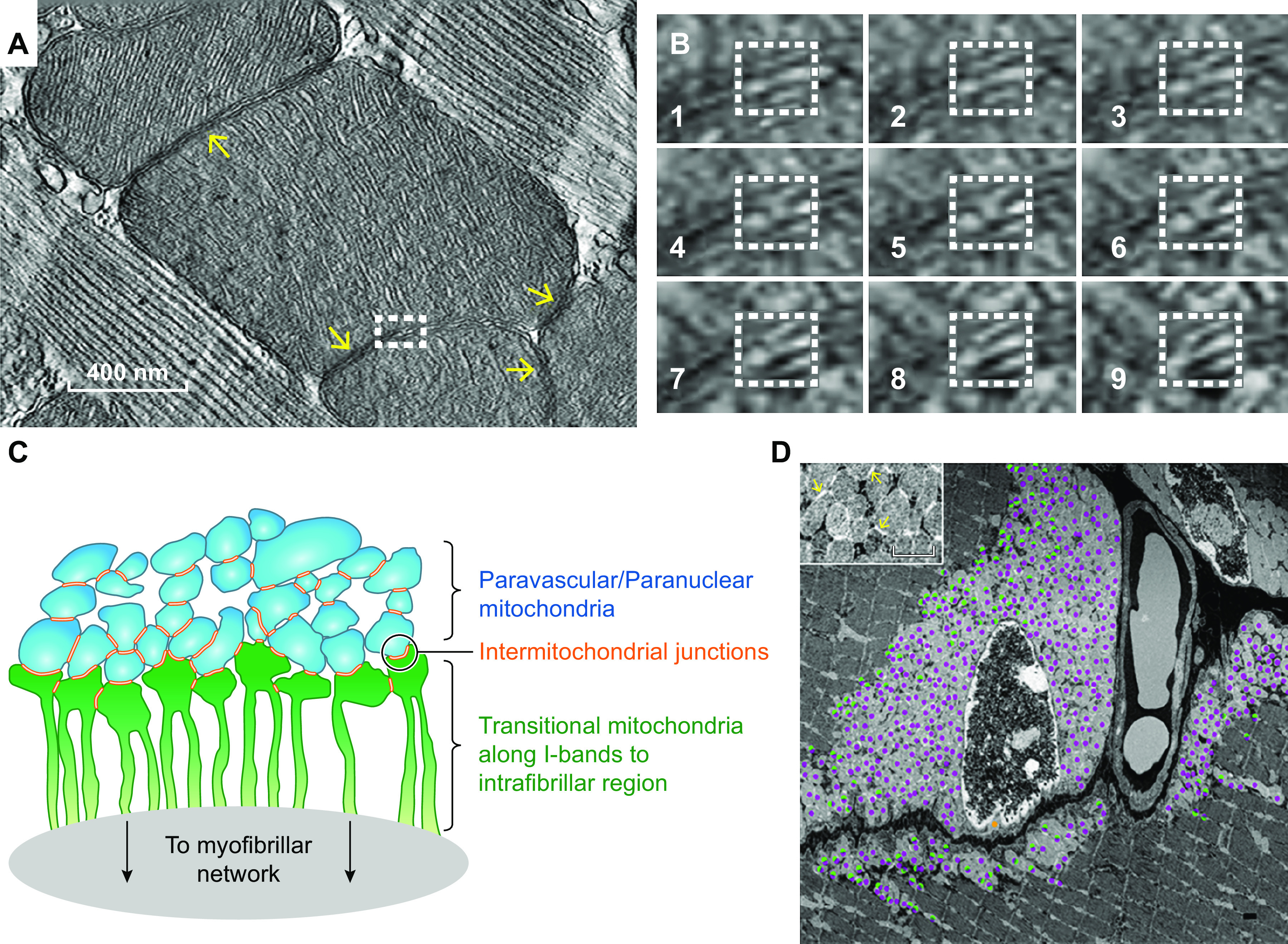

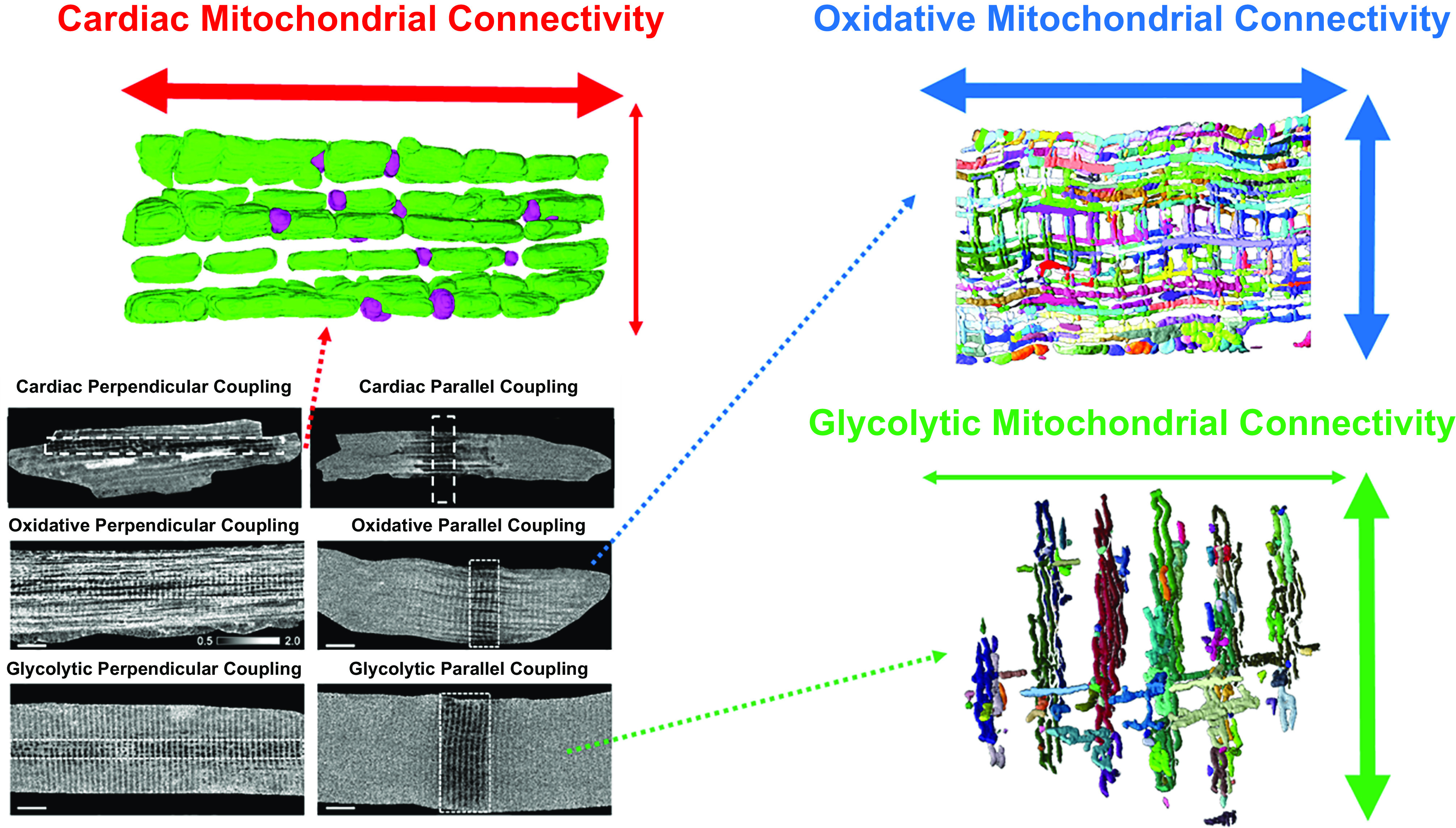

Though little attention was paid to muscle mitochondrial structure in the 1920s, 30s, and 40s, the advent of histochemical staining (318, 319) and electron microscopy (320) together with new methods to isolate mitochondria for functional testing (315, 321) brought muscle mitochondria back into focus in the 1950s. Andersson-Cedergren (322) provided the first look at muscle mitochondrial structure in 3-D in 1959 by using serial section electron microscopy. However, she focused primarily on the motor end plate region of a mouse intercostal skeletal muscle where mitochondria appeared as individual, globular shapes. The initial notion of a mitochondrial reticulum, or network, in skeletal muscle was reported by Bubenzer in 1966 (323) where he showed using 2-D transmission electron microscopy (TEM) that the thin (likely oxidative) fibers of the rat diaphragm contained mitochondrial grids around the sarcomeric I-bands (FIGURE 4B), which were connected through longitudinal mitochondrial tubules along the A-band to form what he proposed was a 3-D mitochondrial framework. Furthermore, Bubenzer showed a fiber type dependence of the mitochondrial network structure as the thicker (likely more glycolytic) fibers of the diaphragm contained smaller grids of mitochondria around the I-bands with fewer connecting mitochondrial tubules along the A-bands. It was around this time that Skulachev first proposed the hypothesis that energy could be transported throughout the cell along mitochondrial membranes in the form of the mitochondrial membrane potential (324). The idea of mitochondria as electric power transmitting cables was suggested to be of particular importance in large cells with “giant” mitochondria, which could cover distances on the scale of cell sizes. In mammalian systems, the muscle fiber was considered likely to contain the proposed electrically coupled mitochondrial energy distribution system due to the large diameter of muscle fibers, the very high-energy demands to be met, and the presence of what appeared in 2-D images to be highly connected networks linking the round mitochondria near the sarcolemma to the more grid-like mitochondrial profiles in the intrafibrillar space (325).

To confirm that mitochondria formed three dimensional networks in rat diaphragm muscle as suggested by the 2-D images of Bubenzer, Skulachev’s group (299) stitched serial section electron microscopy images together in 1978 to provide the first 3-D look at intrafibrillar muscle mitochondrial structure. Indeed, in this seminal work, they confirmed Bubenzer’s suggestions of highly connected mitochondrial networks in the rat thin diaphragm fibers and also showed that these networks could span across the entire cross-sectional diameter of the cell. Moreover, they found that the mitochondrial reticulum of the rat diaphragm contained many intermitochondrial junctions between the inner and outer mitochondrial membranes of adjacent mitochondrial profiles and suggested that electrical conductivity may propagate across these structures analogous to gap junctions. It was further suggested that these junctions may act as regulatory sites of conductivity within the network and may prevent spreading of de-energization throughout the network in response to localized damage. However, the tools to test these many of the newly generated hypotheses were lacking at the time in addition to scarce technology available to visualize the 3-D mitochondrial structures. In fact, all mitochondrial structures were transposed on to dental wax models and photographed to make the 3-D figures for that paper (FIGURE 4C) which, in several cases, made it difficult to fully appreciate the connectivity and complex shapes within the mitochondrial reticulum. Soon thereafter, Skulachev’s group (326) used a similar serial section approach to report that all of the mitochondria within cardiomyocytes were connected through intermitochondrial junctions into a singular mitochondrial reticulum again suggesting that this would allow for cell-wide transmission of electrical potential energy. Furthermore, they demonstrated that mitochondria often appeared physically coupled across the cell membranes at gap junction sites between cardiomyocytes further speculating that the putative intracellular power transmission system could extend across cells through these regions. Many of Skulachev’s original hypotheses regarding the distribution of energy through mitochondrial networks would eventually be tested further once the appropriate technology was developed and will be discussed further below.