Abstract

Kawasaki disease (KD) is an inflammatory autoimmune vasculitis affecting the coronary arteries of very young patients, which can result in coronary artery aneurysms (CAAs) with lifelong manifestations. Accurate identification and assessment of CAAs in the acute phase and sequentially during the chronic phase of KD is fundamental to the treatment plan for these patients. The differential diagnosis of CAA includes atherosclerosis, other vasculitic processes, connective tissue disorders, fistulas, mycotic aneurysms, and procedural sequelae. Understanding of the initial pathophysiology and evolutionary arterial changes is important to interpretation of imaging findings. There are multiple applicable imaging modalities, each with its own strengths, limitations, and role at various stages of the disease process. Coronary CT angiography is useful for evaluation of CAAs as it provides assessment of the entire coronary tree, CAA size, structure, wall, and lumen characteristics and visualization of other cardiothoracic vasculature. Knowledge of the natural history of KD, the spectrum of other conditions that can cause CAA, and the strengths and limitations of cardiovascular imaging are all important factors in imaging decisions and interpretation.

Keywords: Pediatrics, Coronary Arteries, Angiography, Cardiac

© RSNA, 2021

Keywords: Pediatrics, Coronary Arteries, Angiography, Cardiac

Summary

Coronary CT angiography can accurately depict coronary artery pathologic characteristics beyond aneurysm size, providing assessment of the entire coronary tree, structure, and wall and lumen characteristics and visualization of other cardiothoracic vasculature; this information can be used to guide imaging decisions and interpretation including the natural history of Kawasaki disease and a spectrum of other conditions that can cause coronary artery aneurysms.

Essentials

■ Kawasaki disease (KD) is an acute febrile illness affecting children younger than 5 years old, without an identifiable cause, that can result in coronary artery aneurysms (CAAs) with potential lifelong complications.

■ Intravenous immunoglobulin was introduced in the mid to late 1980s and is now a mainstay of treatment, which reduces CAA formation and mortality rates in those with KD.

■ KD can be classified clinically into acute and chronic phases on the basis of the onset of fever or by pathologic changes seen within the coronary artery wall, including acute (necrotizing arteritis), subacute (subacute or chronic vasculitis), or chronic stages (luminal myofibroblastic proliferation).

■ A spectrum of other conditions can cause CAA, including atherosclerosis, other vasculitic processes, connective tissue disorders, fistulas, mycotic aneurysms, and procedural sequelae.

■ Coronary CT angiography is useful for evaluation of CAAs during follow-up of patients with KD as it provides assessment of the entire coronary tree, CAA size, structure, and wall and lumen characteristics and visualization of other cardiothoracic vasculature.

Introduction

Kawasaki disease (KD), first described by Tomisaku Kawasaki in 1967, is an acute self-limited autoimmune illness that typically affects children younger than 5 years of age. In genetically susceptible hosts, an unidentified trigger leads to systemic inflammation, and involvement of the coronary arteries can lead to coronary artery aneurysm (CAA) (1). The incidence of KD has increased, now surpassing rheumatic heart disease as the leading cause of acquired heart disease among children in the industrialized world (2,3). In the United States, epidemiologic data are collected passively, whereas in Japan, active surveillance is performed every 2 years. Data from Japan have shown an increased incidence annually, which authors posit represents a true rise in KD (4). Epidemiologic data also provide insight into pathogenesis, as seasonal and geographic clustering of cases, as well as epidemic outbreaks, suggest an infectious trigger in susceptible children (5). Characteristically, KD affects children between the ages of 6 months and 5 years, occurring predominantly in children of Asian or Pacific Islander descent, with a male preponderance. KD is also a cause of acute coronary syndrome in young adults and presents a challenge for providers when monitoring these patients into adulthood (6).

Acute KD is clinically diagnosed in the setting of persistent fever and the presence of four of five cardinal features, including erythematous rash, changes to extremities, conjunctivitis, erythema or cracking of lips, and cervical lymphadenopathy (6). In cases where acute KD is suspected, echocardiography is used in the initial assessment for potential coronary artery involvement; however, normal findings at echocardiography do not exclude coronary involvement (3). Laboratory studies including elevated C-reactive protein levels, anemia, thrombocytopenia, and hyponatremia indicate a severe inflammatory state and, when present, are associated with an increased risk of CAA development (3). KD demographic predictors for the formation of CAA include male sex and onset at less than 1 or more than 9 years of age (7). Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG)–resistance also increases risk of CAA formation (3).

Incomplete KD represents approximately 10% of all acute KD cases and occurs when fewer than four clinical features are present, therefore presenting a diagnostic challenge (8). Incomplete KD most commonly occurs in infants younger than 6 months old, and 45%–56% of infants with acute KD will present with the incomplete form (9,10). The development of CAA is more frequent than in typical KD, occurring in 37% of patients presenting with incomplete KD, likely due to the difficulty of diagnosis and thus delayed treatment (11,12).

An understanding of the pathophysiology, natural history, and posttreatment history of KD is important to guide the choice of imaging modalities, interpretation of imaging findings, and decisions for surveillance and therapy. Given that CAAs can develop in multiple disease processes, imaging studies need to be interpreted through the lens of patient clinical history and knowledge of the differential diagnosis of CAA. KD is distinct among these disease processes as it occurs in the very young and with subsequent evolution over a lifetime, presenting unique challenges for the follow-up of these patients. Accurate assessment of CAAs in the acute phase and sequentially during the chronic follow-up of KD is fundamental to the treatment plan for these patients. Advanced imaging techniques, such as coronary CT angiography (CCTA), provide tools to accurately depict coronary artery pathologic characteristics beyond aneurysm size, providing further information about CAA composition and the arterial wall characteristics, which allows for further risk stratification (Figs 1–4). Imaging techniques combined with knowledge regarding the natural history of CAA in KD allows providers to understand a patient's current disease status, risk stratification, and potential need for pharmacologic or interventional therapies.

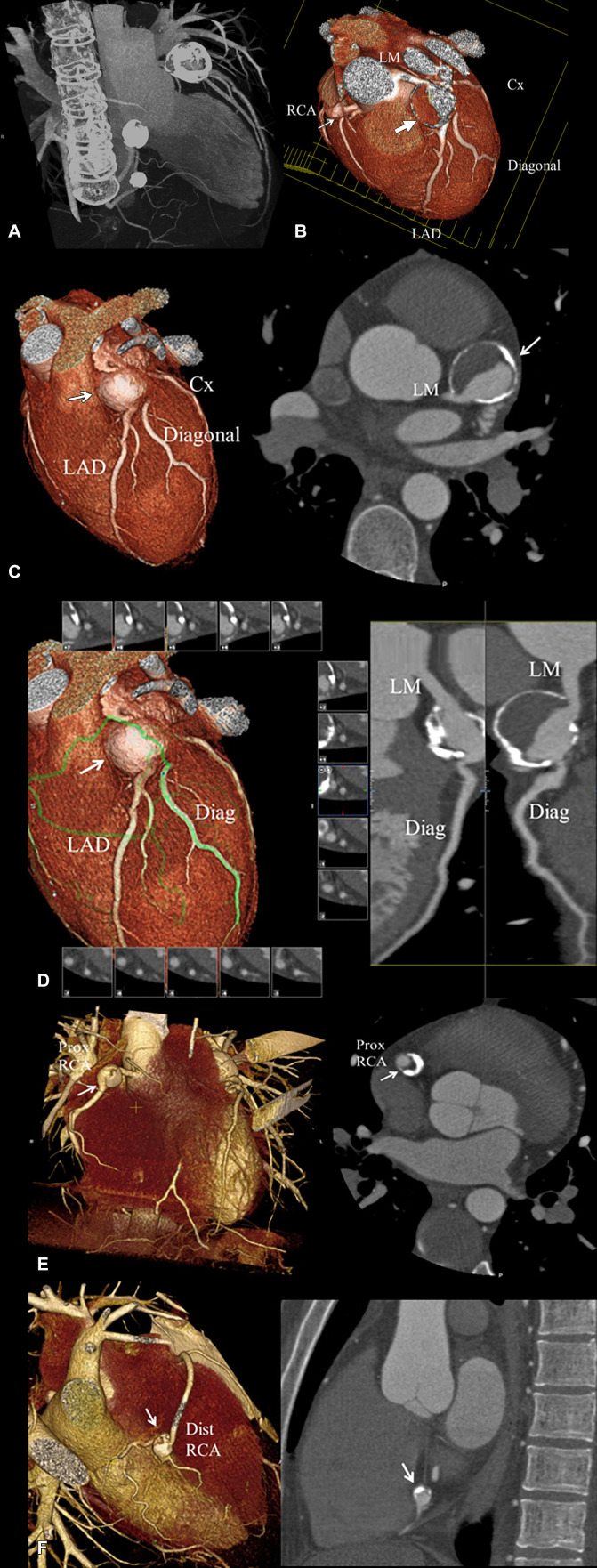

Figure 1:

Coronary CT angiographic images in a 25-year-old man with chronic phase Kawasaki disease. CAAs are seen in the distal LM coronary artery extending into the proximal LAD coronary artery, proximal RCA, and distal RCA, for which he was continued to be given low-dose aspirin and anticoagulation indefinitely. Features that may enhance long-term risk of myocardial ischemia in this patient include presence of multiple large aneurysms across multiple coronary artery branches, distal CAA, and layered mural thrombus. (A) Thick maximum intensity projection image shows the heavy calcification of the CAA involving the LM coronary artery extending into the LAD coronary artery, proximal RCA, and distal RCA. (B) Three-dimensional volume-rendered image of the distal LM coronary artery extending into the proximal LAD coronary artery (large arrow) viewed in an editing plane that shows layered mural thrombus with a patent lumen. The smaller proximal RCA aneurysm is also seen (small arrow). (C) Left: Three-dimensional volume-rendered image shows the LM coronary artery and LAD CAA (arrow). Right: Two-dimensional double oblique view shows the tissue characteristics of the aneurysm with a calcified shell, layered mural thrombus, and lumen opacified with iodinated contrast material (arrow). The distal LM connection to the aneurysm is shown to be patent. (D) Left: Three-dimensional volume-rendered image shows the curved multiplanar reformat path through the LM-LAD artery aneurysm (arrow) and out the first diagonal (Diag) branch (green line). Right: Two-dimensional curved multiplanar reformat view shows patency of the LM into the aneurysms, aneurysm lumen, and diagonal branch ostium extending from the aneurysm. (E) Left: Three-dimensional volume-rendered image shows the proximal RCA aneurysm (arrow). Right: Two-dimensional double oblique view shows the tissue characteristics of the aneurysm with a thick calcified shell, layered mural thrombus, and lumen opacified with iodinated contrast material (arrow). (F) Left: Three-dimensional volume-rendered image shows the distal RCA aneurysm (arrow). Right: Two-dimensional double oblique view shows the tissue characteristics of the aneurysm with a thick calcified shell, layered mural thrombus, and lumen opacified with iodinated contrast material (arrow). CAA = coronary artery aneurysm, Cx = circumflex, Diag = diagonal, Dist = distal, LAD = left anterior descending, LM = left main, Prox = proximal, RCA = right coronary artery.

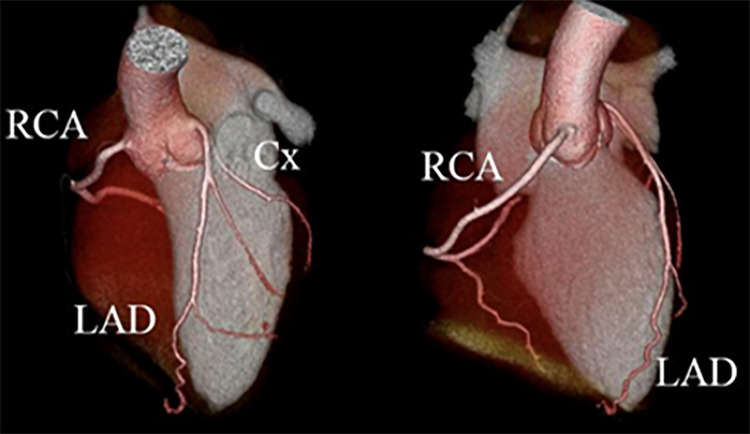

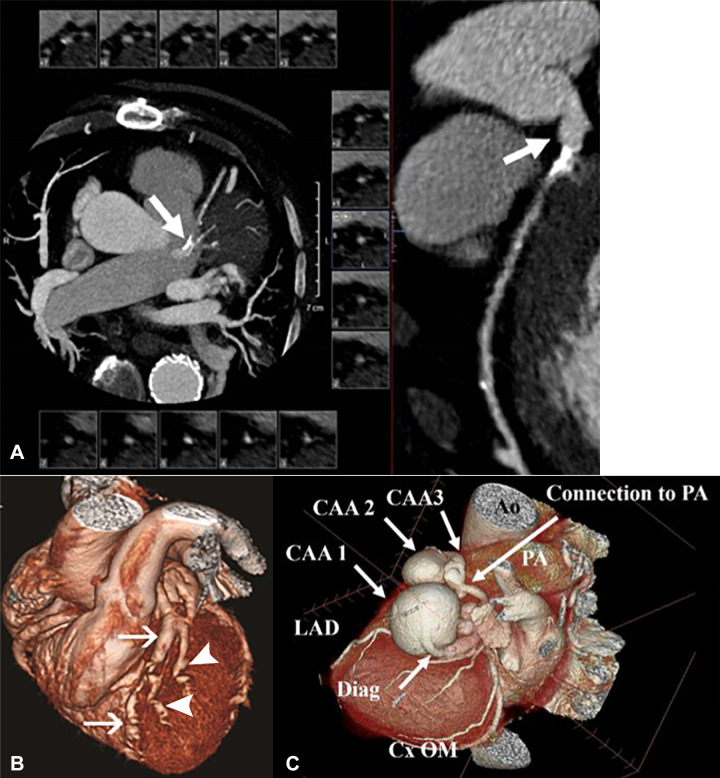

Figure 4:

Coronary CT angiographic images in a 21-year-old man with a history of Kawasaki disease in childhood. Three-dimensional reconstructions show no evidence of coronary artery aneurysm. Cx = circumflex, LAD = left anterior descending artery, RCA = right coronary artery.

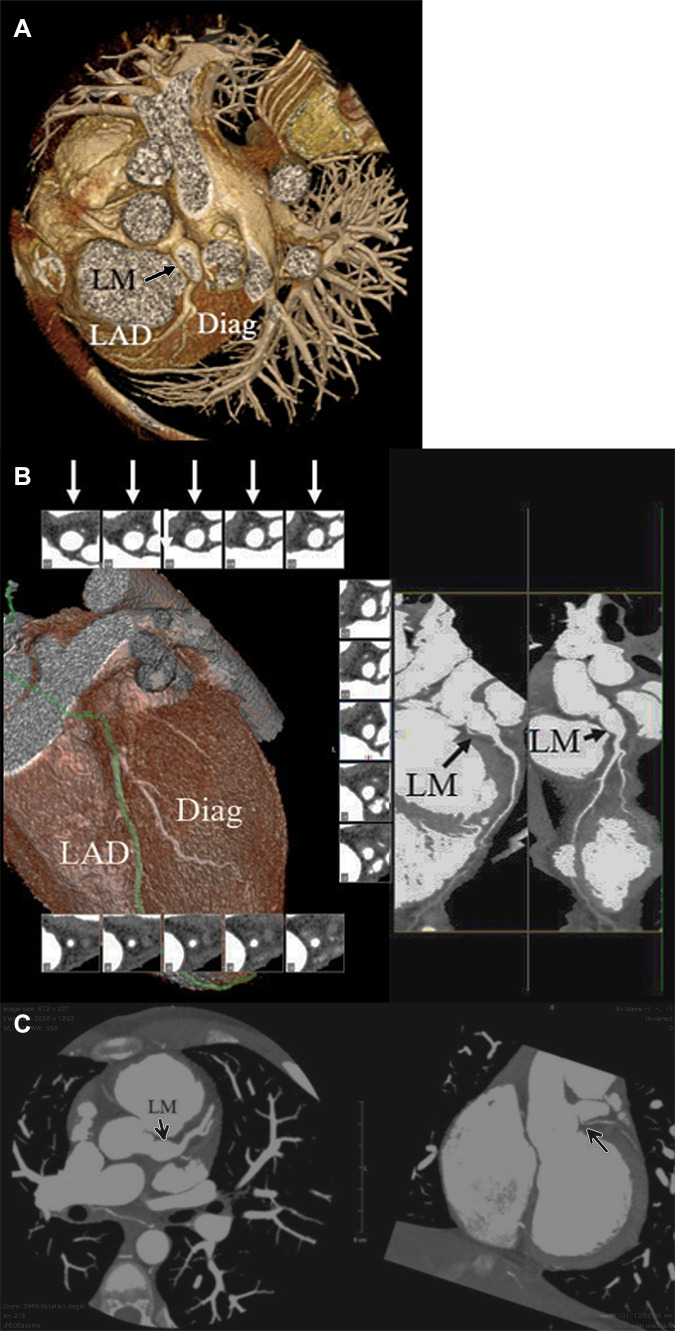

Figure 2:

Coronary CT angiographic images in a 14-year-old boy with chronic phase Kawasaki disease CAA who has undergone thrombectomy and aneurysm reduction surgery. A residual fusiform aneurysm of the LM coronary artery, measuring up to 9 mm in diameter over a length of 11 mm was present. (A) Three-dimensional volume-rendered image shows the LM CAA (arrow). (B) Two-dimensional curved multiplanar and reformat views show patency of the LM into the aneurysm (long black arrow), aneurysm lumen (short black arrow), and patency of the LAD and first diagonal branch. Short-axis views of the LM aneurysm show a patent and aneurysm lumen (white arrows). (C) Left: Two-dimensional double oblique view shows patency of the LM into the aneurysm, aneurysm lumen, and LAD artery and first diagonal branch (arrow). Right: Two-dimensional double oblique view shows the LM residual aneurysm. The LCX coronary artery is occluded. A small collateral vessel arises from the proximal LM coronary artery and supplies the LCX territory (arrow). CAA = coronary artery aneurysm, Diag = diagonal, LAD = left anterior descending, LCX = left circumflex artery, LM = left main.

Pathophysiology of CAA in KD

The underlying cause of KD is still unknown, and although various genes and signaling pathways have been implicated in the susceptibility and response to treatment, no genetic basis has been definitively identified (4). It is likely that in these genetically susceptible patients, a trigger causes an immunologic response involving the innate and adaptive immune system (3), which results in arteritis of the coronary wall. The use of electron microscopy has identified three vasculopathic processes that occur within the coronary artery. KD can be classified clinically into acute and chronic phases on the basis of time from fever onset. Additionally, KD can be classified by pathologic changes within the coronary artery wall that progress over time and include acute (necrotizing arteritis), subacute (subacute or chronic vasculitis), or chronic changes (luminal myofibroblastic proliferation [LMP]).

The first process, termed necrotizing arteritis, occurs acutely within the first 2 weeks and consists of neutrophil-mediated necrosis of all layers of the coronary artery wall, originating from the intima and moving outward toward the adventitia. Neutrophil-derived elastase enzymes are implicated in this process and can disrupt the entire intimal and medial layers with variable adventitial destruction (13). Aneurysms persist and can thrombose or rupture within 1 month. The process of necrotizing arteritis has not been observed to initiate or recur after day 14 and therefore is self-limiting.

Second, subacute and chronic vasculitis proceed in the reverse direction from the adventitia toward the lumen (3). Neutrophilic infiltration is not seen, but rather lymphocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils are predominant in this process, causing variable inflammation within the arterial wall. Subacute and chronic vasculitis can occur months to years after the acute event and is more often associated with fusiform aneurysms, which display gradual tapering at both ends and tend to involve the distal vasculature (6). This process activates muscle cell–derived myofibroblasts, giving way to the next and final process, LMP.

The third process is LMP, which is likely triggered by subacute or chronic vasculitis and occurs in aneurysms with partially preserved medial layers. The inflammatory damage caused by subacute or chronic vasculitis within the arterial wall induces smooth muscle cells residing in the media and adventitia to transition into myofibroblasts. These myofibroblasts remain chronically active and over time can cause progressive luminal narrowing, potentially leading to ischemia or infarction. Large or giant aneurysms with necrotic medial layers will not undergo LMP and instead may normalize their lumen with layered thrombus formation. At autopsy, LMP has been shown to rarely calcify, whereas calcification is commonly observed in layering thrombus (14). Radiographically, the presence of calcifications in the arterial wall can be used as a corollary of the underlying vasculopathologic process. Specifically, the presence of calcifications in an aneurysmal segment suggests normalization of the lumen by thrombus formation, whereas the lack of calcification suggests normalization by LMP (6,14).

Anatomy of CAA in KD

IVIG as a mainstay of treatment was introduced in the mid to late 1980s (15). In a study by Kato et al from before IVIG was clinically used, the incidence of CAA in those with acute KD was 24.6% as detected with coronary angiography (16). Of those patients with CAA in acute KD, 49% had regression at 1–2 years after the onset of acute illness, 41% had persistence of aneurysms without stenosis, and 10% developed aneurysms with stenosis. After the implementation and clinical use of IVIG after the mid to late 1980s, the incidence of CAA among those with acute KD declined to approximately 4% (6,11,17). Giant CAA, defined as dilatation of greater than or equal to 8 mm, develops in 4.4% of patients without treatment (16).

In a study by Takahashi et al from before IVIG was used, two-thirds of patients with CAA underwent regression in caliber within 30 months of presentation (18). The strongest predictive factor for the decrease in diameter of the CAA was initial aneurysm size in the acute stage, with smaller aneurysms tending toward regression. Other factors that favored regression were onset at less than 1 year of age, female sex, fusiform as opposed to saccular or complex structure aneurysm, and distal location of the aneurysm in the coronary artery. With use of IVIG, approximately 71% of CAAs undergo regression by 2 years, this improvement possibly due to earlier recognition and treatment (19). Previously, regression was defined as a decrease in the caliber of the CAA, but further studies have demonstrated that although the caliber of the CAA may decrease, the architecture of the coronary wall remains abnormal, and CAA components are still present and may continue to evolve.

Aneurysms involving noncoronary vasculature have been reported in 2% of untreated patients with acute KD (20). All patients with systemic aneurysms also had CAA, with the vast majority, 95%–100%, having multiple giant CAAs (16,20,21).The occurrence of systemic arterial aneurysm portends a worse prognosis due to its association with severe coronary artery involvement. When systemic aneurysms occur, they tend to be multiple, bilateral, and more commonly found in patients younger than 8 months old (22). The most frequently involved sites are the brachial and internal iliac arteries (20). Overall, long-term outcomes of systemic arterial aneurysms associated with KD tend toward regression, although at a lower frequency and more slowly than seen with CAA (20). Likewise, stenosis tends to occur more slowly in systemic aneurysms when compared with stenosis in coronary arteries (20). Some patients go on to develop stenosis or thrombosis at these systemic sites, although ischemic symptoms from obstruction of the systemic vasculature are rare. Screening for systemic aneurysms has been proposed (20).

Prognosis and Outcomes Associated with CAA in KD

CAA Outcomes and Mortality

Prognosis in KD is determined by the extent of coronary artery involvement, ranging from transient ectasia to giant coronary aneurysm. CAA size in the acute phase is predictive of future outcomes and determines interval follow-up and therapies (6,23). Long-term complications of KD include persistent CAA, stenosis, or thrombosis. Expansion of aneurysm or formation of new aneurysms after the acute phase is rare but has been described (24).

Within the first 2 months of acute illness, coronary artery complications include aneurysm formation, thrombosis, and CAA rupture. Rupture is rare but can be rapidly fatal due to cardiac tamponade, most often occurring in those with giant CAA (25,26). Given the rarity of CAA rupture, data are limited to case reports with varying IVIG treatment administration (25,26). Giant CAAs occur in 0.18% of those diagnosed with KD despite treatment with IVIG, and mortality is highest in this subset of patients, approaching 6% (27). Among patients with bilateral giant CAAs of the left and right coronary arteries, a study by Tsuda et al reported a fourfold increased risk of death compared with giant CAA involving one coronary artery. Notably in this study, 27% of patients received IVIG, and further investigations into the outcomes of patients with giant CAA are ongoing (28). Unlike smaller aneurysms, giant CAAs do not regress over time, and layered mural thrombus formation may occur, leading to occlusion requiring intervention (6,14).

Prior to IVIG, in the late 1970s to early 1980s, the mortality rate approached 0.2%. With the widespread use of IVIG, the mortality rate has declined to less than 0.1%, paralleling a decline in the incidence of CAA from 25% to 4% (28,29). Risk of death, when it does occur, is highest in the first 15 to 45 days after onset of the acute illness due to CAA thrombosis and resultant myocardial infarction caused by marked thrombocytosis, hypercoagulability, abnormal flow conditions within the CAA, and, rarely, coronary rupture with tamponade (30). Reported standardized mortality ratios are available and based on epidemiologic data from Japan spanning treatments before and after the adoption of IVIG, with most data available after IVIG. During the acute phase, defined as 2 months after onset of illness, standardized mortality ratios were reported as 9.86 for boys and girls combined (95% CI: 3.95, 20.3), 13.33 for boys (95% CI: 4.89, 29.07), and 3.85 for girls (95% CI: 0.10, 21.42) (31). Mortality information after the acute phase showed that only those with cardiac sequelae had an elevated standardized mortality ratio at 1.86 (95% CI: 1.02, 3.13) (32). Mortality data from the United States are still emerging.

Progressive coronary artery stenosis continues during the chronic phase of KD, increasing the risk for ischemia (14,33). During follow-up of approximately 2 years after onset of acute illness, stenotic segments occurred in 14% of patients with CAA, more frequently involving the inlet or outlet of aneurysms and most commonly found in the right coronary artery (16,34). The occurrence of stenosis increases over time, affecting nearly 20% of patients with CAA at 17-year follow-up, reflecting the underlying chronic ongoing proliferative process that occurs in a CAA with a damaged but present medial layer (14). Investigators have shown that coronary artery dilatation greater than 5 mm is associated with persistence of CAA and risk of developing stenosis later in life requiring intervention (35). Among patients with progressive stenosis, collateral circulation can develop and is associated with a better prognosis (6). Furthermore, although coronary artery stenosis occurs more often in those with CAA, it has been shown that coronary artery dilatation as small as 4 mm in the acute phase causes morphologic changes in the coronary wall, leading to an increased intimal-medial wall thickness at 10-year follow-up as assessed with intravascular US (36).

Vasoreactivity and Endothelial Dysfunction

Decreased vasoreactivity and a thickened intima-media complex has been seen in persistent aneurysms, regressed aneurysms, and stenotic lesions (33,37–39). Additionally, at adjacent angiographically normal coronary artery segments, diminished vasoreactivity and increased coronary artery intima-media thickness has been reported (39). LMP has also been shown to occur at remote, systemic arteries, which authors suggest is related to circulating factors still under investigation (14). Likewise, systemic vascular beds demonstrate impaired endothelial function in those with a history of KD, even without CAA in the acute phase (40). The mechanism behind endothelial dysfunction is multifactorial and due in part to decreased vasodilatory factors within the coronary artery wall, including decreased endothelial nitric oxide synthetase, ongoing inflammation with increased cytokine production, alterations in adhesion molecules, and abnormal coronary wall architecture (23,41,42).

Atherosclerosis and KD

Similarities exist between atherosclerotic disease and KD and include endothelial dysfunction, intimal thickening, and ongoing inflammation. However, fundamentally atherosclerosis and KD appear to be different processes (42). Impaired endothelial function in atherosclerotic coronary artery disease is well described and is triggered by migration of lipids and macrophages into the endothelial wall, leading to formation of foam cells and low-density lipoprotein oxidation (43). Foam cells and lipid-laden macrophages seen in atherosclerotic plaque have not been observed at autopsies of patients with KD (14,41).

One study by Suzuki et al examined seven patients at autopsy with a history of KD in childhood and CAA; none showed atherosclerotic lesions (41). Another study of six patients showed one patient with findings suggestive of atherosclerosis (44). Furthermore, patients with a history of KD, but without CAA, when followed for up to 20 years, did not show accelerated atherosclerosis as assessed by carotid intima-media thickness and arterial stiffness (45). Differences in the expression of vascular growth factors within the coronary artery wall have also been reported, supporting the fact that KD vasculopathy is a distinct disease process from atherosclerosis (41). However, KD as a risk factor for the development of atherosclerotic disease in adulthood is still under investigation. Adverse lipid profiles including levels of high-density lipoprotein have been reported in those with persistent CAA (46). Current guidelines suggest ongoing atherosclerotic risk factor modification with healthy dietary practices and physical activity for those with a history of KD (6). Guidelines published in 2017 also mention that the earliest patients diagnosed with KD are currently in middle adulthood, thus further studies in this population as they age are needed, and registries for patients with KD in the United States are being developed (6). Long-term follow-up and transition to an adult cardiologist at the age of 18–21 years is recommended for those with a history of CAA regardless of CAA regression. For patients who have never had CAA, long-term cardiology follow-up is not necessary (6,33).

Acute and Chronic KD Treatment

Acute KD Treatment

Currently, the reference standard of treatment for KD is a single high dose of IVIG and aspirin (6). Treatment before day 10 of illness is associated with a decrease in CAA, with greatest benefit in preventing cardiac sequelae seen when treatment is initiated before day 7. In a retrospective study of more than 20 000 patients, IVIG given after day 7 of illness was associated with a 66% increased risk of developing coronary aneurysm or dilatation, with an odds ratio of 1.66 (95% CI: 1.03, 2.68) (47,48). Delayed IVIG treatment, given 10 days after acute illness onset, is associated with an increased risk of CAA, with an odds ratio of 5.3 (CI 95%: 1.7, 15.9) (49). One study found that a total of 10%–20% of patients are IVIG resistant, defined as having a persistent or recurrent fever occurring 36 hours to 2 weeks after the start of IVIG treatment (6). These patients are at increased risk for developing CAA, and 24% of IVIG-resistant patients have been shown to develop coronary artery abnormalities (6,50). Meta-analyses suggest other anti-inflammatory treatments, such as high-dose steroids, lower the incidence of CAA in patients at high risk when given with IVIG (6).

Acute coronary syndrome may occur in the acute setting due to thrombosis of a CAA. Although data are limited, treatment differs from acute coronary syndrome due to coronary artery disease. In KD, the cause of coronary flow disruption is due to acute large thrombus formation and markedly abnormal hemodynamics within a CAA rather than plaque rupture as in coronary artery disease. Therefore, for treatment to restore flow, thrombolytic therapy is preferred in addition to aspirin and anticoagulation therapy (3,6). The small size of coronary arteries in children makes stent placement difficult, but this remains an option if coronary artery size and structure permit (6).

After the acute phase, medication and timing of imaging surveillance are determined by coronary artery z scores adjusted for body surface area, both the maximal CAA z score ever measured and CAA z score at each subsequent follow-up. The 2017 American Heart Association guidelines suggest transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) as the imaging modality of choice for the initial diagnosis of coronary artery involvement in acute KD and during follow-up (6). Compared with prior CAA diagnostic criteria by the Japanese Ministry of Health that relied on absolute measurements, indexed z scores are currently recommended, as they more accurately classify CAA size (6,51,52). CAAs are classified into small, medium or large, or giant on the basis of z score range: small, between 2.5 and 5; medium or large, between 5 and 10; and giant, greater than 10. The greatest initial z score, as well as the z scores at subsequent assessments, determine the frequency of surveillance and treatment decisions; therefore, accurate assessment is crucial. CAA z scores predict future outcomes; those with z scores of greater than 10 do not regress and are at risk for thrombosis and ischemia (6,52). Persistent dilatation or any degree of CAA requires long-term follow-up, with imaging surveillance intervals dependent on the size of the CAA and extent of regression. Serial follow-up assessments include, at minimum, history and physical, echocardiography, and electrocardiography. Use of additional studies, including stress testing and anatomic studies (CCTA, MR angiography [MRA], or invasive angiography), are based on aneurysm size, ischemic symptoms, and risk factors. Risk factors include previous myocardial infarction, CAA thrombosis, history of coronary revascularization, ventricular dysfunction, CAA size, CAA number, CAA location, luminal irregularities, CAA wall tissue characteristics, as well as presence and quality of collateral arteries (23).

Chronic KD Treatment

Long-term medications are aimed at preventing thrombus formation. Aspirin is indicated for a 4- to 6-week duration after the acute illness regardless of coronary artery involvement. For those with no acute CAA, aspirin can be discontinued after this period (recommendation class I, level of evidence A: recommendation that treatment is useful and effective, sufficient multiple randomized trials or meta-analyses). Aspirin should be continued indefinitely for all aneurysms that persist, regardless of size (recommendation class I, level of evidence A). For aneurysms that decrease to normal size after the acute illness, indefinite continuation of aspirin may be considered (recommendation class IIB, level of evidence C: treatment may be considered; only consensus expert opinion, case studies, or standard of care). In patients with persistent medium-sized aneurysms, dual antiplatelet with the addition of irreversible adenosine diphosphate receptor–P2Y12 inhibitors may be considered (recommendation class IIB, level of evidence C). Anticoagulation is reasonable for persistent large or giant aneurysms in addition to aspirin (international normalized ratio goal, 2–3) (recommendation class IIA, level of evidence B: recommendation in favor of treatment). Use of aspirin, irreversible adenosine diphosphate receptor–P2Y12 inhibitors, and anticoagulation may be considered in those with large or giant aneurysm and high-risk features or prior thrombosis (recommendation class IIB, level of evidence C) (6). (6). Low-molecular-weight heparin should be replaced by warfarin only after the aneurysm has stopped expanding, due to the potential anti-inflammatory properties of low-molecular-weight heparin (6). Direct oral anticoagulants are still under investigation and may be used in the future (53). β-blocker therapy can also be considered in those with persistent aneurysms (6). Long-term data are limited in those with KD, but low-dose statins have been shown to decrease inflammatory markers and improve endothelial function in those with KD therapy and may be used. The role of statins in the setting of large aneurysms is under further investigation (54).

In the acute phase, thrombolytic therapy is recommended for restoration of flow if ischemia occurs; percutaneous coronary intervention is another option, although there may be difficulty restoring flow due to the acute large thrombus (6). Treatment of acute coronary syndrome in the chronic phase of KD is challenging. Missed KD in childhood with chronic coronary involvement should be suspected when encountering a young adult presenting with acute coronary syndrome, especially when aneurysmal changes are found. If percutaneous coronary intervention is needed, guidance by intravascular US has been suggested to delineate luminal content and determine true vessel size to guide stent choice and deployment (6).

Differential Diagnosis of CAA

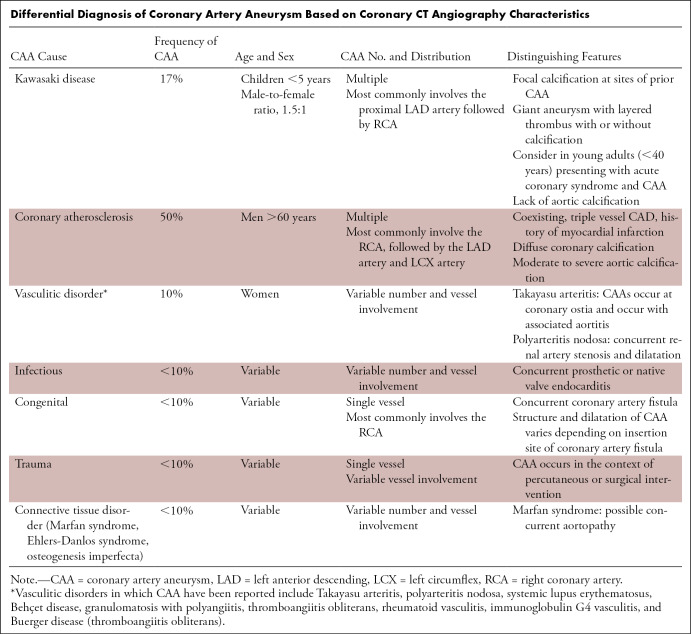

CAAs can be seen in a range of pathologic conditions in addition to KD, including atherosclerosis, vasculitis, connective tissue disorders, congenital or acquired fistulas of the coronary arteries, infection, or direct trauma from iatrogenic causes. The incidence of CAA from all causes in patients undergoing coronary angiography is estimated at 1.4% (55). The number, location, and involvement of vascular distributions vary by the underlying cause of CAA (Table). Given this, differential diagnosis of CAA causes, knowledge of the patient's history, physical examination, and diagnostic studies are essential for contextualization of CAA imaging (Fig 5).

Differential Diagnosis of Coronary Artery Aneurysm Based on Coronary CT Angiography Characteristics

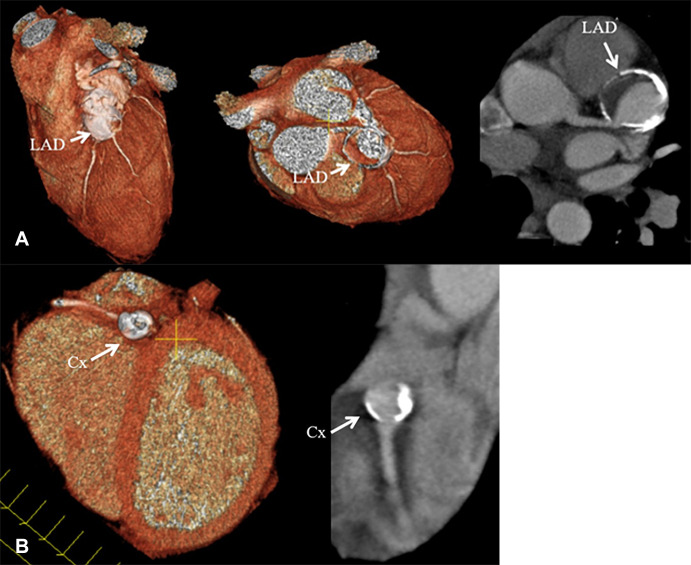

Figure 5:

Non–Kawasaki disease CAAs. (A) Coronary CT angiographic (CCTA) images in a 71-year-old man with multivessel coronary artery disease with an atherosclerotic left main CAA. Left: Curved multiplanar reformat shows an aneurysm. Right: Two-dimensional double oblique view. (B) CCTA image in a 29-year-old woman with systemic lupus erythematosus vasculitis with multiple CAAs. Three-dimensional volume-rendered views with inclusion of the background cardiac anatomy show multiple aneurysms in the LAD coronary artery (arrows) and diagonal vessels (arrowheads). (Reprinted, with permission, from reference 56.) (C) CCTA image in a 76-year-old man with multiple potential causes of CAA. A three-dimensional reconstruction of three serial aneurysms of the diagonal artery shows three giant aneurysms that were present in the first diagonal branch of the LAD coronary artery. The largest measured 4 × 4.4 × 3.6 cm, followed by two additional smaller aneurysms. The artery terminated into a small (2.5 mm) fistulous tract to the main PA. The RCA ostium was mildly aneurysmal. A right bronchial artery aneurysm and focal dilated peripheral branches of the pulmonary arteries in the right upper lobe were also present. Multiple causes are possible, including previous vasculitis, given the multiple aneurysms in multiple vascular distributions, atherosclerotic vascular disease, and the presence of a small arterial to venous fistula in the diagonal artery aneurysms. Ao = aorta, CAA = coronary artery aneurysm, Cx = circumflex, Diag = diagonal, LAD = left anterior descending, OM = obtuse marginal, PA = pulmonary artery, RCA = right coronary artery.

KD Characteristics

Unlike the majority of other CAA-producing conditions, KD is unique in that it tends to involve the proximal left anterior descending artery, followed by the proximal right coronary artery, and last, the left main coronary artery (34,57). Multivessel involvement is more common than single vessel disease; 67% of those with aneurysm will have more than one site involved (57). The aneurysmal structure is commonly sacculo-fusiform or fusiform; saccular lesions do occur but are less common and have worse outcomes, tending not to regress (57). No particular morphologic configuration differs between coronary arteries (20). Coronary calcifications are common, occurring in 94% of patients who had had at least 6 mm of dilatation in the acute phase (58). Calcification in those with KD tends to occur focally, at sites of prior CAA, whereas those with atherosclerosis tend to have more diffuse coronary calcifications (59). Calcification of layered thrombus within a large or giant aneurysm may also occur, forming a rim of calcification (60).

Other Causes and Differential Diagnosis

Atherosclerosis is the most common cause of CAA in the Western World, accounting for 50% of all CAA (Fig 5A) (61–63). CAA is observed in 15% of patients with coronary artery disease, and those affected tend to be male, have coexisting three-vessel obstructive coronary disease, and a history of myocardial infarction (64). Like KD, CAD tends to involve more than one CAA; however, involvement is more common in the right coronary artery, followed by the left anterior descending artery and left circumflex artery (61,65,66). Associated findings include moderate to severe aortic calcifications not seen in those with KD (60).

Vasculitides, hereditary collagen defects, and infectious causes of CAA all have varying number and distribution of CAAs. Takayasu arteritis, a large vessel vasculitis, typically affects the aorta and its branches. CAAs occur in 8% of patients with Takayasu arteritis, tend to develop at coronary ostia, and are associated with aortic wall thickening, suggesting a contiguous spread of inflammation from the aorta into the coronary ostia (60,67–70). All other rheumatologic vasculitic processes have varying number and distribution of CAA. Polyarteritis nodosa is a vasculitis that, similar to KD, affects medium-size muscular arteries. The coronary circulation is the second most affected arterial bed following the renal arteries; variable reports of solitary and multiple CAAs involving various CAA have been reported (71–73). In a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus, fusiform CAAs of the proximal and mid portions of the coronary arteries have been described, with saccular aneurysms and intervening stenoses in the distal coronary arteries (Fig 5B). Other vasculitic conditions in which CAAs have been reported include Behçet disease, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, rheumatoid vasculitis, immunoglobulin G4 vasculitis (and infiltrative disorders of immunoglobulin G4), and Buerger disease (thromboangiitis obliterans) (71,74–82). CAA in patients with heritable collagen defects, including Marfan syndrome, osteogenesis imperfecta, and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, have been reported (83,84). Mycotic CAAs may occur in the setting of native or prosthetic valve bacterial endocarditis, resulting in varying distribution and number of CAAs (85). Case reports of mycotic coronary aneurysm associated with syphilis, Lyme disease, and fungal infections have also been reported (86–88).

Congenital and traumatic causes of CAA tend to affect one coronary artery. Congenital CAA usually occurs in the setting of coronary artery fistulas, most often affecting the RCA. One study found that congenital artery fistulas originated from the right coronary artery 52% of the time, and 90% drained into the right side of the heart (89). Aneurysm structure depends on the site of insertion, with proximal fistulas having a more dilated vessel, while fistulas with distal origins result in a less dilated but more tortuous vessel (90). Direct trauma following angioplasty or atherectomy with resultant CAA has been reported between 0.2% and 2.3% of the time and is limited to the site of intervention (91).

In scenarios where patients with a limited previous history present with CAA, in an age group where coronary artery disease is possible, there may be multiple possible causes of CAA (Fig 5).

CAA Imaging Modalities and Comparisons to CCTA

CCTA

The role of CCTA in the assessment and management of KD is growing. Current guidelines consider CCTA as one option for surveillance of patients at high risk, such as those with persistent aneurysm of any size, history of aneurysm, or inducible ischemia (4). As an alternative to conventional angiography, CCTA has been shown to be a viable choice for the assessment of coronary pathologic conditions and can accurately assess aneurysm, stenosis, and occlusion when compared with the reference standard of conventional coronary angiography (92). In regard to radiation exposure, “as low as reasonably achievable” principles apply to all patients, most importantly to pediatric patients given higher radiosensitivity, smaller body size, greater time to express the effects of radiation, and potentially a greater number of surveillance studies over time when compared with adult patients. Historically, radiation exposure limited the use of CCTA and remains a concern particularly in the pediatric population, but dose-reduction techniques related to hardware and software improvements have successfully reduced exposure levels for some studies to less than 1 mSv (93). Another issue encountered with CCTA in children is that elevated heart rates may necessitate β-blocker therapy, depending on scanner type (94). Patient participation is required if breath-hold technique is to be used, and generally, patients younger than 5–6 years of age cannot be taught breath holding (95). Overall, breath holding is in the range of seconds; however, sedation may be necessary to minimize respiratory artifacts in patients who cannot cooperate (96). Although not specific to patients with KD, there is a risk of contrast agent–related injury that is present with CCTA and invasive angiography. A limitation of CCTA interpretation is the evaluation of heavily calcified coronary artery segments. Interpretation of degree of stenosis may be difficult on the basis of vessel caliber and degree of calcification (92,97,98).

CCTA has a role in the acute and chronic stages of KD. In the acute phase, it has been used when echocardiographic images are unclear or in older patients presenting with delayed-onset KD who are suboptimally imaged with echocardiography (99,100). CCTA is also used in the chronic stages of KD in those with persistent or regressed CAA (94). CCTA provides information on the entire coronary tree, including CAA location, size, structure, overall coaxial lumen, stenosis, and wall characteristics including wall dimensions, thrombus, and calcification (92,94,99,101). Information derived from CCTA may be used to estimate long-term ischemia risk. Information that can be derived from CCTA and may indicate an increased risk for ischemia includes size of CAA, number of CAAs, presence across multiple coronary arteries, abnormal wall characteristics, including thrombus or calcification, and distal CAA location (Figs 1–3) (6). CCTA, when compared with TTE and MRI, is superior at depicting distal CAA, which is associated with flow stasis and may be a risk factor for ischemia (6,102–104). With the ability of CCTA to examine the aneurysm composition and arterial wall, a patient with prior aneurysm but normalized coronary artery diameter can also be assessed (105). In these cases, the luminal diameter of the CAA may appear normal with invasive angiography; however, coronary wall components such as luminal proliferation or thrombus may be detected at CCTA and can be used to identify segments at risk for progressive stenosis (Figs 1–3) (6).

Figure 3:

Coronary CT angiographic images in a 15-year-old boy with chronic phase Kawasaki disease CAAs show a heavily calcified, fusiform 1.5 × 0.8-cm aneurysm present within the proximal LAD coronary artery, with prominent mural thrombus. Contrast is seen in the LAD artery distal to the aneurysm. A more saccular-shaped, heavily calcified 1.0 × 0.7-cm aneurysm was present within the proximal LCX artery, without clinically significant mural thrombus. Patient was continued to be given low-dose aspirin and anticoagulation indefinitely. Features found in this patient that may enhance long-term risk of myocardial ischemia include the presence of multiple giant aneurysms across multiple coronary artery branches that contain layered mural thrombus and heavy calcification. (A) Left: Three-dimensional volume-rendered image shows the proximal LAD coronary artery aneurysm (arrow). Middle: Three-dimensional volume-rendered image shows the LAD coronary artery aneurysm (arrow). The editing plane shows the lumen of the LAD artery aneurysm with layered nonocclusive mural thrombus. Right: Two-dimensional double oblique view shows the tissue characteristics of the aneurysm with a calcified shell, layered mural thrombus, and lumen opacified with iodinated contrast material (arrow). The LAD artery connection to the aneurysm is shown to be patent. (B) Left: Three-dimensional volume-rendered image shows the saccular-shaped, heavily calcified aneurysm of the proximal LCX coronary artery (arrow). Right: Two-dimensional double oblique view shows the tissue characteristics of the aneurysm with a calcified shell, minimal mural thrombus, and patent lumen opacified with iodinated contrast material (arrow). CAA = coronary artery aneurysm, Cx = circumflex, LAD = left anterior descending, LCX = left circumflex.

CCTA with transluminal attenuation gradient analysis has been preliminarily used in patients with KD to noninvasively measure flow characteristics of patients with CAA. Transluminal attenuation gradient analysis relies on the attenuation of contrast media through a coronary artery segment to assess hemodynamics and has recently been applied to patients during the chronic phase of KD to determine flow dynamics across aneurysmal segments (106,107). This novel application of CCTA could potentially provide a functional and dynamic assessment of coronary arteries, offering an alternative to invasive modalities of assessment.

Although there is no role for coronary artery calcium scoring in the acute phase of KD, some studies suggest that coronary calcium can be used to screen those with a questionable history of KD with unknown coronary involvement approximately 15 years after the acute KD presentation (108). Coronary artery calcification is seen in those with a remote history of coronary aneurysm from KD without traditional coronary artery disease risk factors and on average develops 10 years after the acute illness (108,109). Large or giant CAA in the acute phase increases the likelihood of calcification. Lesions greater than or equal to 6 mm are prone to calcification, with 44% of these lesions calcifying by 10 years and 95% calcifying by 20 years as detected with CT (58). Coronary artery calcium scoring has also been proposed as a method to assess young adult patients with a remote history of KD or suspected history of KD with unknown coronary artery status (110).

Conventional Coronary Angiography

CCTA has shown excellent agreement with invasive coronary angiography in the detection of coronary artery stenosis, aneurysm, and occlusion in the follow-up of patients with KD (92,96,103). In a study that compared conventional angiography to CCTA in adolescents with a history of KD, CCTA demonstrated 100% sensitivity for detection of CAA and 87.5% for detection of stenosis greater than 50% or occlusion (111). In the follow-up of patients with KD who were initially imaged with conventional angiography, CCTA displayed all previous abnormalities and additionally displayed worsening stenosis, which led to percutaneous coronary intervention being performed in one patient (96).

Conventional angiography can be used in the acute phase to clarify CAA pathologic characteristics, or percutaneous coronary intervention can be performed in the setting of acute thrombosis. During the chronic phase, invasive angiography should be performed if inducible ischemia is present, or it can be used for periodic surveillance in patients at high risk (6). Unlike conventional coronary angiography, which provides information on intraluminal characteristics, CCTA also details coronary artery wall characteristics. Like CCTA, adjuncts to conventional coronary angiography, including intravascular US and optical coherence tomography, allow for visualization of the coronary wall and accurate measurements of the vessel diameter. Intravascular US has been used in KD to assess myointimal thickening during patient follow-up (36). Similarly, optical coherence tomography allows for improved visualization of the coronary wall when compared with intravascular US, as it can better delineate each arterial layer on the basis of the degree of backscatter. In a follow-up study of patients with KD, optical coherence tomography demonstrated marked intimal hyperplasia, more pronounced at sites of CAA but also present at angiographically normal segments in the coronary tree. Optical coherence tomography was also able to display thrombus, calcifications, fibrosis, and other components of the arterial wall (112). Although both adjunct modalities provide information on the coronary artery wall and luminal contents, over-the-wire catheter placement is required for invasive angiography (3). Like CCTA, invasive angiography requires use of iodinated contrast material and, although not specific to patients with KD, carries with it the risk of contrast material–related injury.

Echocardiography

TTE is a central modality for imaging acute and chronic phases of KD given the need for minimal sedation and lack of radiation exposure. In children, the specificity of TTE when compared with conventional angiography for detection of CAA is 93%–97% for the entire coronary tree; however, sensitivity decreases to between 50% and 80% in distal coronary artery regions (113,114). Echocardiography is also less reliable in older children due to poor acoustic windows. TTE has also been used preliminarily in the detection of coronary stenosis, with some studies reporting a sensitivity of 80% for obstructive lesions, although the role of TTE in stenotic lesions remains unclear (115). Transesophageal echocardiography is a more invasive alternative to TTE, requiring sedation, and therefore is less commonly used in patients with KD. However, there are a small number of cases reporting the use of transesophageal echocardiography when the use of TTE failed to identify an aneurysm in an adult patient suspected of having a history of KD (116).

In comparison to TTE, CCTA is more sensitive for the detection of CAA and stenosis in the chronic follow-up phase of KD (94,95). In one study of eight children, echocardiography did not depict three distal CAAs (102). In another study, eight CAAs that had been observed with CCTA in 12 children were not identified by using echocardiography (95). In both studies, CCTA helped detect all lesions seen with echocardiography (95,102). CCTA provides more reproducible results with less operator and interobserver variability in the diagnosis of total aneurysmal burden, including small or distally located lesions critical for correct risk stratification (99). CCTA is superior at depicting small aneurysms and those with subtle fusiform aneurysmal shape when compared with echocardiography (102).

CCTA can display all segments of the coronary tree including distal lesions. These regions are known to be problematic and suboptimally imaged with TTE, which can typically only show ostial and proximal segments of the coronary arteries (94,99,102,117). CCTA can also reveal the entire length of a given coronary artery including distal segments that are poorly seen with TTE. Up to 14% of aneurysms occur distally, and studies have shown reclassification of patients into higher-risk groups on the basis of distal aneurysms discovered with CCTA that were initially missed with TTE (118,119).

Cardiac MRI

Whole-heart MR coronary angiography differs from traditional coronary MRA as it allows imaging of the entire coronary tree in one image acquisition instead of multiple images targeting each arterial tree (120). Respiratory gating through diaphragmatic tracking eliminates the need for breath holding and is especially important in younger children (121). In the convalescent phase of KD, coronary MRA can help detect CAA, including length and maximal diameter and wall thickness (122,123). However, CCTA remains superior in terms of spatial resolution when compared with coronary MRA (120) and its ability to image more segments of the coronary tree (124). A study by Arnold et al compared coronary MRA and CCTA to angiography during the chronic phase of KD in 16 patients. The sensitivity of coronary MRA in depicting CAA was 93%, while the sensitivity of CCTA was 100% (103). Another study that compared coronary MRA to CCTA retrospectively showed that among 54 patients who underwent both CCTA and coronary MRA, 50% of CAA identified with CCTA was missed at coronary MRA (125). Coronary MRA has limitations for imaging smaller diameter vessels, distal vessels, stenotic lesions, and severity of stenosis in KD (103,104).

Although there are substantial limitations to comprehensive coronary artery analysis with cardiac MRI (CMR), it can provide other important information on myocardial characteristics in patients with KD. CMR can help detect myocarditis, a feature universal to the early stages of KD that develops before coronary arteritis and peaks at day 10 (126,127). In KD, ventricular function has been seen to improve within 1 week after IVIG, and myocarditis, although ubiquitous, resolves in the majority of patients. Myocardial inflammation parallels transient left ventricular dysfunction, both resolving rapidly. In a study by Mavrogeni et al where CMR was performed during the convalescent stage of KD, defined as 20–25 days after the onset of acute illness, 46% of patients demonstrated early gadolinium enhancement suggestive of ongoing inflammation. Resolution occurred in all patients at 3-month follow-up (128). During the initial CMR, late gadolinium enhancement was only seen in three of the 13 patients. During the chronic phase of KD, CMR has been used to demonstrate fibrosis, which occurs in a minority of patients with severe coronary pathologic conditions (128). In one study, late gadolinium enhancement was seen in two of 66 patients, both of whom had giant CAAs and had undergone coronary artery bypass graft previously (129). In another study with comprehensive CMR of 20 patients with chronic phase KD, two patients demonstrated delayed contrast enhancement and showed reduced ejection fraction, both of whom had history of myocardial infarction during acute KD (130).

Assessment for Ischemia

Stress echocardiography can identify segmental wall motion abnormalities in patients with KD (131). Stress echocardiography is more sensitive for detection of ischemia than stress electrocardiography in patients with KD and therefore stress electrocardiography is not recommended (132). Difficulties in using exercise stress echocardiography are related to cooperation in young patients. Those younger than 6 years old generally cannot perform exercise stress testing and require dobutamine administration. Young children also experience a rapid return to resting heart rate after cessation of exercise, leading to false-negative results. Additionally, exercise stress echocardiography may not show abnormalities if substantial collateral vessels have developed. Dobutamine stress echocardiography can provide information on acute cardiac pathologic characteristics such as wall motion abnormalities, and degree of wall motion abnormalities as detected by dobutamine stress echocardiography during the acute phase of KD is an independent risk factor for major adverse cardiac events over a 15-year follow-up (133,134). CMR, performed as a combination stress test with use of dobutamine or adenosine, as well as nuclear stress imaging are also options for ischemic workup in those with persistent aneurysm as outlined in the 2017 guidelines, keeping in mind individual decisions based on radiation exposure with nuclear stress testing (23).

Conclusions

KD is a unique disease process with potential lifelong manifestations. A knowledge of the natural history of KD, the spectrum of other conditions that can cause CAA, and the strengths and limitations of cardiovascular imaging are all important factors in imaging decisions and interpretation. A variety of modalities can be used for follow-up of patients with KD, and selection should be specific to patient characteristics, including age of the patient, aneurysmal size, and location. Registries of disease processes causing CAA, as well as further advances in CAA imaging, will help forward understanding of the incidence, pathophysiologic characteristics, and treatment of KD and other CAA-related illnesses through a multidisciplinary approach.

Authors declared no funding for this work.

Disclosures of Conflicts of Interest: J.T. No relevant relationships. M.K. No relevant relationships. M.T. No relevant relationships. J.S.S. No relevant relationships.

Abbreviations:

- CAA

- coronary artery aneurysm

- CCTA

- coronary CT angiography

- CMR

- cardiac MRI

- IVIG

- intravenous immunoglobulin

- KD

- Kawasaki disease

- LMP

- luminal myofibroblastic proliferation

- MRA

- MR angiography

- TTE

- transthoracic echocardiography

References

- 1. Kawasaki T. Acute febrile mucocutaneous syndrome with lymphoid involvement with specific desquamation of the fingers and toes in children [in Japanese]. Arerugi 1967;16(3):178–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Newburger JW, Takahashi M, Gerber MA, et al. Diagnosis, treatment, and long-term management of Kawasaki disease: a statement for health professionals from the Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis and Kawasaki Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, American Heart Association. Circulation 2004;110(17):2747–2771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Newburger JW, Takahashi M, Burns JC. Kawasaki Disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;67(14):1738–1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nakamura Y. Kawasaki disease: epidemiology and the lessons from it. Int J Rheum Dis 2018;21(1):16–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nakamura Y, Yashiro M, Uehara R, Oki I, Watanabe M, Yanagawa H. Monthly observation of the number of patients with Kawasaki disease and its incidence rates in Japan: chronological and geographical observation from nationwide surveys. J Epidemiol 2008;18(6):273–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. McCrindle BW, Rowley AH, Newburger JW, et al. Diagnosis, Treatment, and Long-Term Management of Kawasaki Disease: A Scientific Statement for Health Professionals From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2017;135(17):e927–e999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Belay ED, Maddox RA, Holman RC, Curns AT, Ballah K, Schonberger LB. Kawasaki syndrome and risk factors for coronary artery abnormalities: United States, 1994-2003. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2006;25(3):245–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fukushige J, Takahashi N, Ueda Y, Ueda K. Incidence and clinical features of incomplete Kawasaki disease. Acta Paediatr 1994;83(10):1057–1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yeom JS, Woo HO, Park JS, Park ES, Seo JH, Youn HS. Kawasaki disease in infants. Korean J Pediatr 2013;56(9):377–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yeo Y, Kim T, Ha K, et al. Incomplete Kawasaki disease in patients younger than 1 year of age: a possible inherent risk factor. Eur J Pediatr 2009;168(2):157–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Baer AZ, Rubin LG, Shapiro CA, et al. Prevalence of coronary artery lesions on the initial echocardiogram in Kawasaki syndrome. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2006;160(7):686–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Anderson MS, Todd JK, Glodé MP. Delayed diagnosis of Kawasaki syndrome: an analysis of the problem. Pediatrics 2005;115(4):e428–e433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kanai T, Ishiwata T, Kobayashi T, et al. Ulinastatin, a urinary trypsin inhibitor, for the initial treatment of patients with Kawasaki disease: a retrospective study. Circulation 2011;124(25):2822–2828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Orenstein JM, Shulman ST, Fox LM, et al. Three linked vasculopathic processes characterize Kawasaki disease: a light and transmission electron microscopic study. PLoS One 2012;7(6):e38998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Takahashi K, Oharaseki T, Yokouchi Y, Yamada H, Shibuya K, Naoe S. A half-century of autopsy results--incidence of pediatric vasculitis syndromes, especially Kawasaki disease. Circ J 2012;76(4):964–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kato H, Sugimura T, Akagi T, et al. Long-term consequences of Kawasaki disease. A 10- to 21-year follow-up study of 594 patients. Circulation 1996;94(6):1379–1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Newburger JW, Takahashi M, Burns JC, et al. The treatment of Kawasaki syndrome with intravenous gamma globulin. N Engl J Med 1986;315(6):341–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Takahashi M, Mason W, Lewis AB. Regression of coronary aneurysms in patients with Kawasaki syndrome. Circulation 1987;75(2):387–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Friedman KG, Gauvreau K, Hamaoka-Okamoto A, et al. Coronary Artery Aneurysms in Kawasaki Disease: Risk Factors for Progressive Disease and Adverse Cardiac Events in the US Population. J Am Heart Assoc 2016;5(9):e003289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hoshino S, Tsuda E, Yamada O. Characteristics and Fate of Systemic Artery Aneurysm after Kawasaki Disease. J Pediatr 2015;167(1):108–112. e1–e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Noto N, Kato M, Abe Y, et al. Reassessment of carotid intima-media thickness by standard deviation score in children and adolescents after Kawasaki disease. Springerplus 2015;4(1):479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Heran MK, Hockley A. Multiple mirror-image peripheral arterial aneurysms in Kawasaki disease. Pediatr Cardiol 2011;32(5):670–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. McCrindle BW, Li JS, Minich LL, et al. Coronary artery involvement in children with Kawasaki disease: risk factors from analysis of serial normalized measurements. Circulation 2007;116(2):174–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tsuda E, Kamiya T, Ono Y, Kimura K, Echigo S. Dilated coronary arterial lesions in the late period after Kawasaki disease. Heart 2005;91(2):177–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Miyamoto T, Ikeda K, Ishii Y, Kobayashi T. Rupture of a coronary artery aneurysm in Kawasaki disease: a rare case and review of the literature for the past 15 years. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2014;147(6):e67–e69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fukazawa R, Kobayashi T, Mikami M, et al. Nationwide Survey of Patients With Giant Coronary Aneurysm Secondary to Kawasaki Disease 1999-2010 in Japan. Circ J 2017;82(1):239–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Makino N, Nakamura Y, Yashiro M, et al. Descriptive epidemiology of Kawasaki disease in Japan, 2011-2012: from the results of the 22nd nationwide survey. J Epidemiol 2015;25(3):239–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tsuda E, Hamaoka K, Suzuki H, et al. A survey of the 3-decade outcome for patients with giant aneurysms caused by Kawasaki disease. Am Heart J 2014;167(2):249–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chang RK. Hospitalizations for Kawasaki disease among children in the United States, 1988-1997. Pediatrics 2002;109(6):e87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Burns JC, Glode MP, Clarke SH, Wiggins J Jr, Hathaway WE. Coagulopathy and platelet activation in Kawasaki syndrome: identification of patients at high risk for development of coronary artery aneurysms. J Pediatr 1984;105(2):206–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nakamura Y, Yanagawa H, Kawasaki T. Mortality among children with Kawasaki disease in Japan. N Engl J Med 1992;326(19):1246–1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nakamura Y, Aso E, Yashiro M, et al. Mortality among Japanese with a history of Kawasaki disease: results at the end of 2009. J Epidemiol 2013;23(6):429–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gordon JB, Daniels LB, Kahn AM, et al. The Spectrum of Cardiovascular Lesions Requiring Intervention in Adults After Kawasaki Disease. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2016;9(7):687–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Suzuki A, Kamiya T, Kuwahara N, et al. Coronary arterial lesions of Kawasaki disease: cardiac catheterization findings of 1100 cases. Pediatr Cardiol 1986;7(1):3–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mueller F, Knirsch W, Harpes P, Prêtre R, Valsangiacomo Buechel E, Kretschmar O. Long-term follow-up of acute changes in coronary artery diameter caused by Kawasaki disease: risk factors for development of stenotic lesions. Clin Res Cardiol 2009;98(8):501–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tsuda E, Kamiya T, Kimura K, Ono Y, Echigo S. Coronary artery dilatation exceeding 4.0 mm during acute Kawasaki disease predicts a high probability of subsequent late intima-medial thickening. Pediatr Cardiol 2002;23(1):9–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yamakawa R, Ishii M, Sugimura T, et al. Coronary endothelial dysfunction after Kawasaki disease: evaluation by intracoronary injection of acetylcholine. J Am Coll Cardiol 1998;31(5):1074–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sugimura T, Kato H, Inoue O, Takagi J, Fukuda T, Sato N. Vasodilatory response of the coronary arteries after Kawasaki disease: evaluation by intracoronary injection of isosorbide dinitrate. J Pediatr 1992;121(5 Pt 1):684–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Suzuki A, Yamagishi M, Kimura K, et al. Functional behavior and morphology of the coronary artery wall in patients with Kawasaki disease assessed by intravascular ultrasound. J Am Coll Cardiol 1996;27(2):291–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pinto FF, Gomes I, Loureiro P, Laranjo S, Timóteo AT, Carmo MM. Vascular function long term after Kawasaki disease: another piece of the puzzle? Cardiol Young 2017;27(3):488–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Suzuki A, Miyagawa-Tomita S, Komatsu K, et al. Active remodeling of the coronary arterial lesions in the late phase of Kawasaki disease: immunohistochemical study. Circulation 2000;101(25):2935–2941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fukazawa R. Long-term prognosis of Kawasaki disease: increased cardiovascular risk? Curr Opin Pediatr 2010;22(5):587–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Falk E. Pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;47(8 Suppl):C7–C12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Takahashi K, Oharaseki T, Naoe S. Pathological study of postcoronary arteritis in adolescents and young adults: with reference to the relationship between sequelae of Kawasaki disease and atherosclerosis. Pediatr Cardiol 2001;22(2):138–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gupta-Malhotra M, Gruber D, Abraham SS, et al. Atherosclerosis in survivors of Kawasaki disease. J Pediatr 2009;155(4):572–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Cheung YF, Yung TC, Tam SC, Ho MH, Chau AK. Novel and traditional cardiovascular risk factors in children after Kawasaki disease: implications for premature atherosclerosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004;43(1):120–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tse SM, Silverman ED, McCrindle BW, Yeung RS. Early treatment with intravenous immunoglobulin in patients with Kawasaki disease. J Pediatr 2002;140(4):450–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kuwabara M, Yashiro M, Ae R, Yanagawa H, Nakamura Y. The effects of early intravenous immunoglobulin therapy for Kawasaki disease: The 22nd nationwide survey in Japan. Int J Cardiol 2018;269(334):338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bal AK, Prasad D, Umali Pamintuan MA, Mammen-Prasad E, Petrova A. Timing of intravenous immunoglobulin treatment and risk of coronary artery abnormalities in children with Kawasaki disease. Pediatr Neonatol 2014;55(5):387–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Burns JC, Capparelli EV, Brown JA, Newburger JW, Glode MP. Intravenous gamma-globulin treatment and retreatment in Kawasaki disease. US/Canadian Kawasaki Syndrome Study Group. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1998;17(12):1144–1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. de Zorzi A, Colan SD, Gauvreau K, Baker AL, Sundel RP, Newburger JW. Coronary artery dimensions may be misclassified as normal in Kawasaki disease. J Pediatr 1998;133(2):254–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Marchesi A, Tarissi de Jacobis I, Rigante D, et al. Kawasaki disease: guidelines of the Italian Society of Pediatrics, part I - definition, epidemiology, etiopathogenesis, clinical expression and management of the acute phase. Ital J Pediatr 2018;44(1):102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Chen T, Li J, Xu Q, Li X, Lv Q, Wu H. Antithrombotic Therapy of a Young Adult with Giant Left Main Coronary Artery Aneurysm. Int Heart J 2020;61(3):601–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Huang SM, Weng KP, Chang JS, Lee WY, Huang SH, Hsieh KS. Effects of statin therapy in children complicated with coronary arterial abnormality late after Kawasaki disease: a pilot study. Circ J 2008;72(10):1583–1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Hartnell GG, Parnell BM, Pridie RB. Coronary artery ectasia. Its prevalence and clinical significance in 4993 patients. Br Heart J 1985;54(4):392–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Shriki J, Shinbane JS, Azadi N, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus coronary vasculitis demonstrated on cardiac computed tomography. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol 2014;43(5):294–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Onouchi Z, Shimazu S, Kiyosawa N, Takamatsu T, Hamaoka K. Aneurysms of the coronary arteries in Kawasaki disease. An angiographic study of 30 cases. Circulation 1982;66(1):6–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Kaichi S, Tsuda E, Fujita H, et al. Acute coronary artery dilation due to Kawasaki disease and subsequent late calcification as detected by electron beam computed tomography. Pediatr Cardiol 2008;29(3):568–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Gordon JB, Kahn AM, Burns JC. When children with Kawasaki disease grow up: Myocardial and vascular complications in adulthood. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;54(21):1911–1920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Jeudy J, White CS, Kligerman SJ, et al. Spectrum of Coronary Artery Aneurysms: From the Radiologic Pathology Archives. RadioGraphics 2018;38(1):11–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Cohen P, O'Gara PT. Coronary artery aneurysms: a review of the natural history, pathophysiology, and management. Cardiol Rev 2008;16(6):301–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Tsuda E, Kamiya T, Ono Y, Kimura K, Kurosaki K, Echigo S. Incidence of stenotic lesions predicted by acute phase changes in coronary arterial diameter during Kawasaki disease. Pediatr Cardiol 2005;26(1):73–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Pahlavan PS, Niroomand F. Coronary artery aneurysm: a review. Clin Cardiol 2006;29(10):439–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Lamblin N, Bauters C, Hermant X, Lablanche JM, Helbecque N, Amouyel P. Polymorphisms in the promoter regions of MMP-2,. MMP-3,MMP-9 and MMP-12 genes as determinants of aneurysmal coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002;40(1):43–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Valente S, Lazzeri C, Giglioli C, et al. Clinical expression of coronary artery ectasia. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2007;8(10):815–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Swaye PS, Fisher LD, Litwin P, et al. Aneurysmal coronary artery disease. Circulation 1983;67(1):134–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Matsubara O, Kuwata T, Nemoto T, Kasuga T, Numano F. Coronary artery lesions in Takayasu arteritis: pathological considerations. Heart Vessels Suppl 1992;7(S1):26–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Kang EJ, Kim SM, Choe YH, Lee GY, Lee KN, Kim DK. Takayasu arteritis: assessment of coronary arterial abnormalities with 128-section dual-source CT angiography of the coronary arteries and aorta. Radiology 2014;270(1):74–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Suzuki H, Daida H, Tanaka M, et al. Giant aneurysm of the left main coronary artery in Takayasu aortitis. Heart 1999;81(2):214–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Chougule A, Bal A, Das A, Jain S, Bahl A. Uncommon associations and catastrophic manifestation in Takayasu arteritis: an autopsy case report. Cardiovasc Pathol 2014;23(5):313–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Mavrogeni S, Manoussakis MN, Karagiorga TC, et al. Detection of coronary artery lesions and myocardial necrosis by magnetic resonance in systemic necrotizing vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum 2009;61(8):1121–1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Wi J, Choi HH, Lee CJ, et al. Acute Myocardial Infarction due to Polyarteritis Nodosa in a Young Female Patient. Korean Circ J 2010;40(4):197–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Yanagawa B, Kumar P, Tsuneyoshi H, et al. Coronary artery bypass in the context of polyarteritis nodosa. Ann Thorac Surg 2010;89(2):623–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Melikoglu M, Kural-Seyahi E, Tascilar K, Yazici H. The unique features of vasculitis in Behçet's syndrome. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2008;35(1-2):40–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Barçin C, Iyisoy A, Kurşaklioğlu H, Demirtaş E. A giant left main coronary artery aneurysm in a patient with Behçet's Disease. Anadolu Kardiyol Derg 2004;4(2):193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Siegrist PT, Sumitsuji S, Osuga K, Sakaguchi T, Tachibana K, Nanto S. Endovascular coil embolization of Behçet disease-related giant aneurysm of the right coronary artery after failure of surgical suture. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2013;6(6):e31–e32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Cevik C, Otahbachi M, Nugent K, Jenkins LA. Coronary artery aneurysms in Behçet's disease. Cardiovasc Revasc Med 2009;10(2):128–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Gülcü E, Sağlam E, Gülcü E, Emiroğlu MY. Giant coronary artery aneurysm in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis [in Turkish]. Turk Kardiyol Dern Ars 2011;39(8):701–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Kan-o M, Kado Y, Sadanaga A, Tamiya S, Toyoshima S, Sakamoto M. Immunoglobulin G4-related multiple cardiovascular lesions successfully treated with a combination of open surgery and corticosteroid therapy. J Vasc Surg 2015;61(6):1599–1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Guo Y, Ansdell D, Brouha S, Yen A. Coronary periarteritis in a patient with multi-organ IgG4-related disease. J Radiol Case Rep 2015;9(1):1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Ishizaka N. IgG4-related disease underlying the pathogenesis of coronary artery disease. Clin Chim Acta 2013;415:220–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Tezuka D, Haraguchi G, Inagaki H, Isobe M. Progression of thrombogenesis in large coronary aneurysms during anticoagulant therapy in a Buerger's disease patient. BMJ Case Rep 2013;2013(aug06 1):bcr2013009945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Eriksen UH, Aunsholt NA, Nielsen TT. Enormous right coronary arterial aneurysm in a patient with type IV Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Int J Cardiol 1992;35(2):259–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Hajsadeghi S, Jafarian Kerman SR, Pouraliakbar H, Mohammadi R. A huge coronary artery aneurysm in osteogenesis imperfecta: a case report. Acta Med Iran 2012;50(11):785–788. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Berkowitz JM, Lansman S, Fyfe B. Coronary artery mycotic aneurysm following endocarditis of a composite aortic graft--a case report and literature review. Angiology 1998;49(2):145–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Tewari S, Moorthy N. Cardiovascular syphilis with coronary stenosis and aneurysm. Indian Heart J 2014;66(6):735–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Gasser R, Watzinger N, Eber B, et al. Coronary artery aneurysm in two patients with long-standing Lyme borreliosis. Borreliosis Study Group. Lancet 1994;344(8932):1300–1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Yeen W, Panza A, Cook S, Warrell C, Sun B, Crestanello JA. Mycotic coronary artery aneurysm from fungal prosthetic valve endocarditis. Ann Thorac Surg 2007;84(1):280–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Levin DC, Fellows KE, Abrams HL. Hemodynamically significant primary anomalies of the coronary arteries. Angiographic aspects. Circulation 1978;58(1):25–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Qureshi SA. Coronary arterial fistulas. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2006;1(1):51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Aoki J, Kirtane A, Leon MB, Dangas G. Coronary artery aneurysms after drug-eluting stent implantation. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2008;1(1):14–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Tsujii N, Tsuda E, Kanzaki S, Kurosaki K. Measurements of coronary artery aneurysms due to Kawasaki Disease by dual-source computed tomography (DSCT). Pediatr Cardiol 2016;37(3):442–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Hill KD, Frush DP, Han BK, et al. Radiation safety in children with congenital and acquired heart disease: A scientific position statement on multimodality dose optimization from the Image Gently Alliance. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2017;10(7):797–818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Xing Y, Wang H, Yu X, Chen R, Hou Y. Assessment of coronary artery lesions in children with Kawasaki disease: evaluation of MSCT in comparison with 2-D echocardiography. Pediatr Radiol 2009;39(11):1209–1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Peng Y, Zeng J, Du Z, Sun G, Guo H. Usefulness of 64-slice MDCT for follow-up of young children with coronary artery aneurysm due to Kawasaki disease: initial experience. Eur J Radiol 2009;69(3):500–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Carbone I, Cannata D, Algeri E, et al. Adolescent Kawasaki disease: usefulness of 64-slice CT coronary angiography for follow-up investigation. Pediatr Radiol 2011;41(9):1165–1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Sato Y, Matsumoto N, Komatsu S, et al. Coronary artery abnormalities after Kawasaki disease in an adult: depiction at whole heart coronary magnetic resonance angiography. Int J Cardiol 2007;116(3):396–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Kanamaru H, Karasawa K, Ichikawa R, et al. Advantages of multislice spiral computed tomography for evaluation of serious coronary complications after Kawasaki disease [in Japanese]. J Cardiol 2007;50(1):21–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Yu Y, Sun K, Wang R, et al. Comparison study of echocardiography and dual-source CT in diagnosis of coronary artery aneurysm due to Kawasaki disease: coronary artery disease. Echocardiography 2011;28(9):1025–1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Azmoon S, Atkinson D, Budoff MJ. Refractory progression of coronary aneurysms, a case of delayed onset Kawasaki disease as depicted by cardiac computed tomography angiography. Congenit Heart Dis 2010;5(3):321–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Sohn S, Kim HS, Lee SW. Multidetector row computed tomography for follow-up of patients with coronary artery aneurysms due to Kawasaki disease. Pediatr Cardiol 2004;25(1):35–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Chu WC, Mok GC, Lam WW, Yam MC, Sung RY. Assessment of coronary artery aneurysms in paediatric patients with Kawasaki disease by multidetector row CT angiography: feasibility and comparison with 2D echocardiography. Pediatr Radiol 2006;36(11):1148–1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Arnold R, Ley S, Ley-Zaporozhan J, et al. Visualization of coronary arteries in patients after childhood Kawasaki syndrome: value of multidetector CT and MR imaging in comparison to conventional coronary catheterization. Pediatr Radiol 2007;37(10):998–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Cantin L, Chartrand-Lefebvre C, Marcotte F, Pressacco J, Ducharme A, Lapierre C. Coronary artery noninvasive imaging in adult Kawasaki disease. Clin Imaging 2009;33(3):181–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Goh YG, Ong CC, Tan G, et al. Coronary manifestations of Kawasaki Disease in computed tomography coronary angiography. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2018;12(4):275–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]