Abstract

Systemic inflammation elicited by sepsis can induce an acute cerebral dysfunction known as sepsis-associated encephalopathy (SAE). Recent evidence suggests that SAE is common but shows a dynamic trajectory over time. Half of all patients with sepsis develop SAE in the intensive care unit, and some survivors present with sustained cognitive impairments for several years after initial sepsis onset. It is not clear why some, but not all, patients develop SAE and also the factors that determine the persistence of SAE. Here, we first summarize the chronic pathology and the dynamic changes in cognitive functions seen after the onset of sepsis. We then outline the cerebral effects of sepsis, such as neuroinflammation, alterations in neuronal synapses and neurovascular changes. We discuss the key factors that might contribute to the development and persistence of SAE in older patients, including premorbid neurodegenerative pathology, side effects of sedatives, renal dysfunction and latent virus reactivation. Finally, we postulate that some of the mechanisms that underpin neuropathology in SAE may also be relevant to delirium and persisting cognitive impairments that are seen in patients with severe COVID-19.

Subject terms: Neuroimmunology, Inflammation

In this Review, Manabe and Heneka examine how the systemic inflammation associated with sepsis can lead to acute cerebral dysfunction known as sepsis-associated encephalopathy (SAE). Moreover, they suggest that some of the mechanisms involved in SAE may be relevant for understanding the cognitive impairments that develop in some patients with COVID-19.

Introduction

Pathogenic infections can cause dysregulated host immune responses and, as a consequence, life-threatening organ dysfunction. The current definition of sepsis (known as the ‘Sepsis-3’ criteria) has placed more emphasis on the organ failure seen in patients with sepsis and requires the presence of at least two points on Sequential Organ Failure Assessment1. Globally, sepsis affected 49 million individuals and led to 11 million deaths in 2017 alone2. We are also observing a gradual decline in the age-standardized mortality rate for sepsis, which is likely due to improved clinical guidelines and care, and this has led to a concomitant rise in the number of patients who survive sepsis2. Although patients of any age can develop sepsis, age acts as a strong risk factor owing to a more than 10-fold increase of the incidence rate among individuals older than 65 years old compared with younger individuals (18–49 years old)3. For this reason, the majority (56%) of these survivors of sepsis are older than 65 years old, and half of them do not fully recover but, instead, develop new functional impairments4. In parallel, emerging evidence suggests that peripheral inflammatory mediators can be chronically elevated for up to 1 year after the hospital admission due to sepsis5. Given that the central nervous system (CNS) is no longer considered to be an immune-privileged organ6, it is plausible that innate immune responses in the brain could be affected for an extended period of time following sepsis. This has led to the need for new research into sepsis as a chronic illness in older patients, as well as the need for new animal models to facilitate this.

In terms of acute cerebral dysfunction caused by sepsis, delirium and coma are observed in approximately half of the patients who have sepsis at the time of intensive care unit (ICU) admission7,8. Such neurological features — that are not due to direct brain infection by pathogens — are referred to as sepsis-associated encephalopathy (SAE)7,8. Notably, delirium represents an acute disturbance of attention, awareness and cognition for hours to days and implies the reversibility of neurological impairment9. However, accumulating evidence suggests that cognitive impairments persist in a subset of patients who survive sepsis and live for several years after the initial onset of sepsis10,11. Yet it is also true that not all patients with sepsis in the ICU develop cognitive impairments8, and some survivors fully recover from neurological impairment during their recovery from sepsis11. What determines the onset and persistence of SAE remains poorly understood. Nevertheless, it is likely that these heterogeneous neurological presentations among survivors of sepsis can be deciphered by focusing on the altered innate and adaptive immune responses in the brain, both of which are known to play intimate roles in various CNS disorders affecting patients’ cognitive functions, such as Alzheimer disease and multiple sclerosis12,13. In this Review, we provide an overview of the temporal trajectory of sepsis and SAE based on data both from clinical observations of cerebral dysfunctions and from animal models (Table 1). We discuss possible mechanisms underlying the persistent cognitive impairments seen in older patients who survive sepsis, with a focus on the role of age-related inflammation and common neurodegenerative pathology. Finally, we discuss how our current knowledge of SAE could be helpful in understanding the encephalopathy and long-term neurological complications that have been seen in hospitalized patients with COVID-19.

Table 1.

Brain dysfunction in mouse models of sepsis

| Type of sepsis model | Specific bacterial component | Protocol | Age of mice (months) | Brain pathology observed | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gram-negative bacterial infection | Escherichia coli O55:B5 LPS | 8 mg kg–1 via intraperitoneal route | 2 | Impaired spatial memory and transient reduction of NMDA and AMPA receptor expression without neuronal cell death in the hippocampus | 210 |

| E. coli O55:B5 LPS | 1 mg kg–1 via intraperitoneal route on 4 consecutive days | 2–3 | Normal neuron and synapse density in the hippocampus | 211,212 | |

| E. coli O55:B5 LPS | 0.25 mg kg–1 via intraperitoneal route on 7 consecutive days | Unknown | Neuronal apoptosis in the CA1 region of the hippocampus | 41 | |

| E. coli O111:B4 LPS | 0.5 mg kg–1 via intraperitoneal route | 2–3 | Increased dendritic spine turnover with a consequence of the reduced spine density in the somatosensory cortex at 2 months post injection | 213 | |

| E. coli O127:B8 LPS | 5 mg kg–1 via intraperitoneal route | 5 | Increased working memory errors and chronic reduction of synaptic proteins without neuronal cell death in the hippocampus at 2 months post injection | 98 | |

|

E. coli O127:B8 LPS Salmonella typhimurium LPS |

0.2 mg kg–1 via intraperitoneal route on 2 consecutive days | 7 (young) and 19 (aged) | Normal dendritic spine density in the hippocampus of young mice but chronic reduction in the aged mice at 3 months post injection | 99 | |

| Gram-positive bacterial infection | Streptococcus pneumoniae | OD600 = 0.63, via intratracheal route | 1–2 | Monocyte infiltration to the brain and chronic spatial memory deficits | 36 |

| Polymicrobial sepsis | Caecal contents (leaked from the caecum to the peritoneal cavity) | Ligation below the ileocaecal valve and puncture of the caecum with a needle (caecal ligation and puncture) | 1–2 | Long-term spatial memory deficits and reduced dendritic spine density in the CA1 region | 214 |

| 1–2 | Long-term impairments of contextual fear conditioning and reduced dendritic spine density in the amygdala and dentate gyrus, but not CA1, of the hippocampus | 217 | |||

| 1–2 | Persistently impaired extinction of fear conditioning and monocyte infiltration without dendritic spine loss or neuronal cell death | 113 | |||

| Viral infection | Influenza A virus subtype H3N2 | 10 FFUs via intranasal route | 2–3 | Impaired spatial memory and temporal reduction of dendritic spine density in the hippocampus at 30 days post infection | 100 |

| Poly(I:C) | 50 μg via intravenous route | 2–4 | Impaired spatial memory in an IFNAR1-dependent manner | 216 | |

| Poly(I:C) | 5 mg kg–1 via intraperitoneal route | 1–2 | Impaired motor learning after the rotarod training and the elevated rate of dendritic spine elimination in the motor cortex in vivo | 101 | |

| Poly(I:C) with low (<0.5 kb) or high (1–6 kb) molecular weights | 12–20 mg kg–1 via intraperitoneal route | 3–6 (young) and 21–24 (aged) | Age-dependent and molecular weight-dependent increase in brain cytokine production and temporary working memory deficits | 71 |

AMPA, α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionic acid; FFU, focus forming unit; IFNAR1, type I interferon-α receptor; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; NMDA, N-methyl-d-aspartate; OD600, optical density at a wavelength of 600 nm; poly(I:C), polyinosinic–polycytidylic acid.

Clinical trajectory of sepsis

Acute phase of sepsis

A landmark study in the United States from 1979 to 2001 (n = 10,319,418) demonstrated that various organisms can cause sepsis14. Bacterial infections account for 90% of all sepsis cases, with 52% of all cases caused by Gram-positive bacteria and 38% by Gram-negative bacteria, and polymicrobial and fungal infections accounting, respectively, for 4.7% and 4.6% of all cases14. A recent EPIC (Extended Prevalence of Infection in Intensive Care) III study of patients in the ICU with a median Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score of 7 (n = 15,202) found that bacterial, fungal and viral infections account for 65%, 16% and 3.7% of sepsis cases, respectively15. This study documented that 44% of cultures were positive for multiple bacteria, with 37% of all patients’ cultures containing Gram-positive bacteria and 67% containing Gram-negative bacteria15. On the contrary, other studies suggested that viral infections represent a more frequent aetiology of sepsis. Notably, the majority (62%) of patients with community-acquired pneumonia (n = 6,874) meet the Sepsis-3 criteria16. Viruses are detected in 24% of adult hospitalized patients with community-acquired pneumonia (n = 2,259)17. Among the viruses detected in this cohort, 23% were human rhinoviruses, and 16% were influenza A and influenza B viruses17. Another study in Southeast Asia (n = 815 adult patients; 56% of them meeting the Sepsis-3 criteria) showed that viral infections account for 32% of the identified pathogens with 7.5% showing co-infection with bacteria and viruses18.

In the acute phase of sepsis, these infections can induce inflammation by generating pathogen-activated molecular patterns and damage-associated molecular patterns that activate the innate immune system, for example, via Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and nucleotide-binding and oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptors19. An overwhelming pathogen load can lead to an exaggerated host immune response that is associated with the excessive production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines and acute phase proteins, including, but not restricted to, IL-1β, IL-6, tumour necrosis factor (TNF), interferon-γ (IFNγ), CXC-chemokine ligand 10 (CXCL10), C-reactive protein (CRP) and complement factors, within minutes of detection of damage-associated molecular patterns or pathogen-activated molecular patterns19,20. Based on a recently proposed definition, this so-called ‘cytokine storm’ that occurs in sepsis is thought to be the major cause of organ dysfunction and acute constitutional symptoms (namely, fever, fatigue and anorexia)20. Of note, controversy over the concept of this cytokine storm exists because other disorders linked to pathological cytokine elevations (such as haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and multicentric Castleman disease) are characterized by increases in different inflammatory mediators, and patients show varying degrees of increases in cytokines20. Nevertheless, death caused by this cytokine storm is relatively rare, accounting for less than 10% of all sepsis cases21. As shown in Fig. 1a, the cytokine storm peaks within 2 weeks after the onset of sepsis, and, simultaneously, modest immunosuppression is initiated presumably to avoid the onset of additional cytokine storms elicited by the subsequent infections19.

Fig. 1. Long-term trajectory of sepsis and SAE.

a | Long-term sequelae of sepsis. Sepsis causes excessive inflammation (often referred to as a ‘cytokine storm’), and subsequent chronic alterations in the peripheral immune system21. Compared with healthy individuals, patients with sepsis show both features of enhanced inflammation and enhanced immunosuppression. For example, there is expansion of myeloid-derived suppressor cell populations and higher plasma levels of C-reactive protein (CRP), IL-6 and IL-8 in patients with sepsis5,21. Immunoparalysis is linked to low lymphocyte counts and increased levels of immunosuppressive proteins in plasma with an elevated risk of infections22,23. b | Proposed model of dynamic changes seen in cognitive functions following onset of sepsis. Around half of the patients present with delirium and coma in the intensive care unit (ICU)8,11, but whereas some survivors show restoration of cognitive functions during the recovery phase, others show persistence of cognitive impairments for 2 years or more after sepsis onset11,26–28. CNS, central nervous system; SAE, sepsis-associated encephalopathy.

Chronic phase of sepsis

Although half of those who initially survive sepsis make a full recovery, the other half, especially older patients, develop a chronic condition post sepsis that is associated with a higher 1-year mortality rate4,21. In an attempt to better understand this chronic illness, the concept of persistent inflammation, immunosuppression and catabolism syndrome was first introduced by Gentile et al. in 2012 (ref.22). Persistent inflammation, immunosuppression and catabolism syndrome was defined as either a sustained mild inflammation, a robust immunoparalysis or a combination of both of these immune responses. This first description and a recent follow-up study by Stortz et al.21 showed that the prolonged inflammation seen in patients after sepsis was mediated by increased plasma levels of pro-inflammatory proteins (such as CRP, IL-6 and IL-8) and the expansion of functionally immature myeloid-derived suppressor cells for 4 weeks post sepsis. These studies also found that immunosuppression in patients with sepsis was associated with lymphopenia and elevated plasma levels of immunosuppressive proteins, such as IL-10 and soluble PDL1, for more than 3 weeks21,22. Despite a clear normalizing tendency within 2 weeks after hospitalization in all cases, a recent report showed that two-thirds of patients who survived sepsis had elevated serum levels of CRP and soluble PDL1 for more than a year after their initial hospital admission5. Interestingly, IL-6 levels in 74% of patients who survived sepsis started to increase from 3 months after the hospitalization and continued to increase in the subsequent 9 months5. The development of an immunosuppressive state during the chronic phase of sepsis is consistent with the fact that patients who initially survive sepsis are frequently readmitted to the hospital due to the reoccurrence of sepsis23 and show increased susceptibility to fungal and opportunistic bacterial infections24 and reactivation of latent viruses, including Epstein–Barr virus, herpes simplex virus (HSV) and cytomegalovirus25.

Disturbed cognition after sepsis

Dynamic changes in cognitive functions

In addition to these effects in the periphery, epidemiological data highlight that dynamic changes are seen in cognitive functions following the onset of sepsis (Fig. 1b). A recent retrospective multicentre analysis with large sample sizes (n = 2,513) uncovered that approximately half (53%) of patients with severe sepsis showed delirium or abnormal Glasgow Coma Scale at ICU admission8. However, another study indicates the reversibility of cognitive impairment because 37% of patients with sepsis showed recovery from neurological symptoms within 4 weeks after the initial onset26. This acute cerebral effect and recovery in some patients are corroborated by a recent large-scale retrospective study of German health claims data (n = 161,567)11. The authors longitudinally evaluated the incidence of dementia diagnosis after sepsis onset for more than 6 years and found that dementia diagnosis peaked at the time of sepsis diagnosis11. In this analysis, although a clear reduction in dementia diagnosis was noted within 6 months after the onset, older patients (≥85 years old) who survived sepsis were especially at higher risk of dementia diagnosis for 2 years after the sepsis onset11. Likewise, another population-based study in the United Kingdom (n = 989,800) that followed older survivors for 14 years reported that sepsis can double the risk of dementia, especially vascular cognitive impairment27. More generally, even when an infection (such as infection in the respiratory tract, urinary tract and soft tissue) does not cause sepsis, the highest risk of dementia onset was observed at 3–12 months post infection, and elevated risk for dementia was maintained for more than 9 years after the infection27. Again, a higher dementia risk following infection was found among the oldest subgroup of the cohort (≥90 years old)27. These long-lasting effects on cognitive function are congruent with an earlier US Health and Retirement Study (n = 1,194), which showed that patients who survived severe sepsis have an increased risk of cognitive impairments when followed up for 8 years after sepsis onset28. Nevertheless, it remains to be determined which predisposing factors are associated with the recovery or persistence of SAE.

Brain regions at risk in sepsis

Accumulating evidence suggests that significant damage occurs to the brain in patients with SAE. Frequent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings of cytotoxic oedema in patients with SAE implicate cellular damage that is likely due to ischaemia29. Although not specific to encephalopathy onset in patients with sepsis, abnormal electroencephalography (for example, continuous theta and slower delta waves) is prevalent in patients with SAE and affects 12–100% of these patients according to a systematic review of 17 studies30. Previous plasma biomarker studies demonstrated that patients with SAE displayed a steeper elevation of neurofilament light (NfL) chain protein than those without SAE in the ICU during the follow-up of 7 days31. Because higher plasma NfL levels are associated with cognitive impairments in older individuals32,33, these data reflect neuronal or axonal injury in patients with SAE. Furthermore, another brain injury marker, neuron-specific enolase (NSE), was found to be elevated in the serum of approximately half of the patients with sepsis in the ICU34. Although a diverse range of cognitive functions appear to be affected in SAE, previous studies repeatedly indicate that these impairments are functionally associated with the frontal cortex and medial temporal lobe. For instance, patients who survive sepsis show impaired verbal learning and memory35, spatial recognition memory36, visual attention and executive functions within a year after the hospital discharge37. Neuroimaging studies have indicated a reduced volume of the hippocampus, amygdala and cortex during hospitalization38 and of the hippocampus and superior frontal cortex 6–24 months after the hospital discharge35,37. In post-mortem brain tissues from patients who died from sepsis, apoptotic neurons were found in the amygdala, as well as in the hypothalamus and medulla39,40. Consistently, some, but not all, investigators have reported neuronal loss in the hippocampus in animal models of sepsis-like systemic inflammation41,42 (Box 1; Table 1). Overall, it appears to be possible that widespread CNS damage can be caused by sepsis, but the anatomical changes in the medial temporal lobe and frontal cortex, in particular, may correlate more with the cognitive domains affected in patients with SAE.

Box 1 A need for standardized animal models.

The failure of more than 150 clinical trials in the past three decades warns us that the current animal models of sepsis do not accurately recapitulate sepsis seen in human patients. Notably, rodents and humans show key differences in their physiological responses to infections (such as sensitivity to endotoxins and body temperature changes)217. Despite age conferring a strong risk of adult sepsis and cognitive impairments in humans3,11, juvenile mice at 1–4 months old have been frequently used in sepsis models (Table 1; see Supplementary Table 1). This may lead us to overlook the pathology observed only in aged animals. Standardization of protocols is another consideration for improving the reproducibility of findings. Many investigators have published conflicting data using rodents and have argued for and against neuronal cell death41,42,102,210,211, synapse loss98,99,102,210,212,213 and spatial memory deficits41,99,218. There are also inconsistent data concerning the loss of dendritic spines after polymicrobial sepsis induced by caecal ligation and puncture113,214,215. Because these studies differed in the age of animals, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) injection protocols (for example, differences in dosage, bacterial serotype and number of LPS injections) and caecal ligation and puncture surgery methods (differing in the size or number of the punctures and the length of the ligated caecum), technical inconsistency is likely to account for these mixed findings. Lastly, in accord with the Sepsis-3 criteria, it is important to confirm the development of peripheral organ failures using a uniform criterion (for instance, a recommendation proposed for the caecal ligation and puncture models219) (Supplementary Table 1) because these are often unexplored when the research is focused on the cerebral effects of sepsis and the related systemic inflammation.

Cerebral changes in sepsis

Immediate neuroinflammation

Neuroinflammatory responses to sepsis are not due to infection of the brain but systemic inflammation relaying to the innate immunity in the CNS via various routes. Circulating lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (a well-known component of the Gram-negative bacterial cell wall) can activate TLR2 and TLR4 in the circumventricular organs, choroid plexus and leptomeninges, which profoundly induces transcription of inflammatory mediators across the brain parenchyma43,44. Of note, only 0.025% of intravenously injected endotoxin could cross the blood–brain barrier (BBB), implying that the entry of LPS into the brain should have a negligible effect on neuroinflammation45. In addition, some blood-borne cytokines (including IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF) are known to pass through the BBB via respective saturable transporters46–48. Consequent activation of cytokine receptors — as exemplified by type I IL-1 receptor (IL-1R1) and TNF receptor (TNFR) — elevates cytokine levels in the brain49,50. In particular, IL-1R1 activation in glial cells induces genes to encode cyclooxygenase 2 (COX2) in endothelial cells, which synthesizes prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) from arachidonic acid49,51,52. PGE2 activates prostaglandin EP2 receptor in microglia, leading to a generation of pro-inflammatory mediators (such as IL-1β, IL-6, TNF and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS))53. The nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain, leucine-rich repeat and pyrin domain-containing protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome (Box 2) is also activated in microglia with a consequence of IL-1β and IL-18 production54,55. Previous studies highlighted that IL-1β levels in the brain were coupled to neuronal activity of the vagal afferent fibre. This tenth cranial nerve conveys sensory information from the abdominal organs to various brain regions (such as the hypothalamus, amygdala, thalamus and cortex) via the nucleus tractus solitarius and locus coeruleus56. Sub-diaphragmatic vagotomy attenuated IL-1β increases in the hypothalamus and hippocampus following systemic injection of LPS and IL-1β (refs57,58). Conversely, intraperitoneal TNF or IL-1β injection markedly increased the activity of the vagal afferent fibres, which was blocked in mice deficient for the respective receptors for these cytokines in the nodose ganglion (also known as the inferior ganglion of the vagus nerve)59. Electrical stimulation of the afferent vagal nerve also increased the IL-1β levels in the hypothalamus and hippocampus60. However, the molecular mechanism of how vagal stimulation elevates IL-1β levels in the brain has yet to be deciphered. Additionally, considering the long projecting areas of the vagus fibres, neuronal activity may be altered in widespread brain regions. In support, vagus nerve stimulation increased noradrenaline levels in the hippocampus and cortex61. Endotoxin injection increased neuronal activity in the cortex, which was prevented in TNF-deficient mice but not NLRP3-deficient mice62.

Viral infection induces neuroinflammation via distinct molecular mechanisms from bacterial infection. Notably, polyinosinic–polycytidylic acid (poly(I:C)) is a synthetic analogue of double-stranded RNA and is recognized by TLR3 in endosomes63,64, as well as by melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 (MDA5) and retinoic acid-induced gene 1 (RIG1) in the cytoplasm65,66. Provided that viruses do not invade and infect the CNS cells, these neuroinflammatory responses are mainly driven by systemic inflammation. An intraperitoneal injection of poly(I:C) into rodents increases the levels of antiviral type I interferons and pro-inflammatory cytokines in the periphery and the brain via TLR3 and type I IFNα receptor (IFNAR1) activation63,64,67–69. Upregulation of the Cox2 gene (likely derived from endothelium and microglia or perivascular macrophages) was also observed, thus prostaglandins are likely to aid neuroinflammation caused by viral infection67,70. Intriguingly, a recent study has demonstrated that greater production of inflammatory mediators in the brain, as well as in the plasma, is linked to a higher molecular weight of poly(I:C) or older age of the injected animals71. This underlines an important consideration when viral sepsis is modelled in rodents by the systemic injection of poly(I:C).

On a post-mortem investigation, brain tissue from patients who died from sepsis showed higher levels of CD68 immunostaining in microglia with less ramified morphology (consistent with microglia activation), thereby supporting the idea that neuroinflammation occurs after the onset of sepsis72,73. Induction of glial activation is corroborated by positron emission tomography (PET) imaging of neuroinflammation following systemic injections of LPS into mice and humans74,75. Both of these studies demonstrated that radioligand signals for glial translocator protein (TSPO) (for example, [11C]PBR28 and [18F]FEPPA) were enhanced in all of the examined brain regions74,75, suggesting that there is no apparent correlation between the levels of neuroinflammation and anatomical susceptibility to the damage caused by sepsis (namely, frontal cortex and medial temporal lobe).

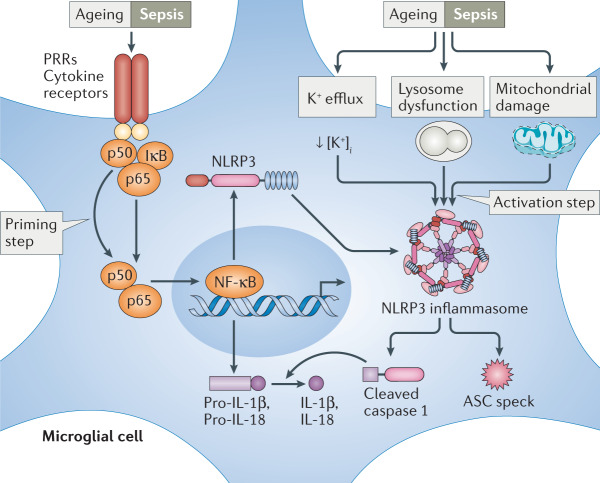

Box 2 The NLRP3 inflammasome.

The canonical nucleotide binding oligomerization domain, leucine-rich repeat and pyrin domain-containing protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome pathway is one of the major pathways leading to production of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the brain in response to systemic inflammation. Pro-inflammatory cytokines derived from the blood circulation or lipopolysaccharide (LPS) can enter the brain through regions lacking an intact blood–brain barrier (BBB) and the saturable transporter system for each cytokine. LPS and these cytokines activate pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) and cytokine receptors to induce the nuclear translocation of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) — this is the inflammasome priming step (see the figure)220,221. This leads to transcription of NLRP3 monomers and cytokine precursors (such as pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18)221,222. In parallel, both systemic inflammation and ageing result in K+ efflux via P2X7 purinoceptors223–225, mitochondrial damage226,227 and lysosomal dysfunctions228 (the inflammasome activation step). As a consequence of both priming and activation steps, NLRP3 monomers, apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a caspase recruitment domain (ASC) and pro-caspase 1 assemble together to form the NLRP3 inflammasome229. Subsequently, cleaved caspase 1 (proteolytically active form of pro-caspase 1 dimers) is released from the NLRP3 inflammasome and contributes to producing IL-1β and IL-18 from the respective precursors54,55,230. Meanwhile, ASC proteins are oligomerized as ASC specks and are released into the extracellular space153,231.

Cognitive toxicity of cytokines

Because pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF, are known to play important roles in learning and memory in healthy and diseased brains76, the worsening of cognitive functions in patients with sepsis may be attributed to cytokine-induced toxicity in the brain. For instance, during normal ageing in humans, higher plasma IL-6 levels were associated with a reduced hippocampal volume in older human subjects77 and with age-related cognitive decline in the same individuals78. Although controversial findings have been reported79–81, young healthy humans who received endotoxin showed a temporal deterioration of episodic memory and working memory, correlating with the increased IL-6 and TNF levels82,83. Patients with delirium caused by sepsis and other causes (such as hip fracture surgery) also showed higher IL-6 and IL-8 levels (but not TNF levels) than cognitively intact patients with sepsis or other hospitalized patients84–86. Interestingly, despite the delirious symptoms lasting for 8 days, cytokine levels became normalized in these patients at an earlier time86, indicating that the initial rise of IL-6 levels might be sufficient to induce the cognitive impairments seen in patients with sepsis in the ICU. Considering that IL-6 levels can progressively increase in patients who survive sepsis from 3 months after the hospital admission5, it might be possible that this second wave of increased IL-6 might contribute to the persistence or delayed onset of cognitive impairments. Meanwhile, other investigators reported the elevated levels of IL-1β in the plasma and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of patients with delirium caused by sepsis or hip fracture surgery87,88. Previous preclinical studies supported the multifactorial roles of these pro-inflammatory cytokines in cognitive functions and neuronal activity. To illustrate, IL-6 deficiency prevented LPS-induced deficits in transient spatial memory in young mice without affecting the circulating IL-1β and TNF levels89. In addition, pretreatment with IL-1R antagonists protected against LPS-induced impairments in working memory in naive mice90 and prevented impairments in contextual fear memory in mice possessing prion-induced neurodegenerative pathology in the hippocampus91. We discuss the roles of IL-1β in the aged brain in more detail below.

Synapses in SAE

As cognitive functions strongly correlate with the abundance of synapses across the species, cognitive disturbances in patients with SAE may result from synapse loss. To illustrate, reduced synapse density is found in the hippocampus of patients with cognitive impairments, such as mild cognitive impairment, early-onset Alzheimer disease and non-demented oldest-old individuals92–95. Similarly, age-related synapse loss is documented in the frontal cortex of primates and in the hippocampus of mice, which is again associated with altered behaviours that suggest cognitive dysfunction96,97. As summarized in Table 1, several investigators found diminished synapses in mice for more than a month after systemic inflammation (including that induced by endotoxin challenge and peripheral viral infections) in the absence of infection in the CNS98–102. In agreement with microglial contacts with dendrites promoting the filopodia formation (namely, synaptogenesis)103,104, endotoxin challenge reduced microglia–synapse interactions102,105 and synchronization of cortical neuronal activity in vivo105. Another study demonstrated that LPS injection increased the neuronal firing in the cortex62. Altogether, these in vivo functional imaging data sets hinted at synaptic changes following systemic inflammation. To our knowledge, however, the clinical data to examine the synapse density in patients with SAE are currently not available. One recent biomarker study using CSF from patients with delirium caused by infection showed downregulation of proteins related to synapse formation and function106, implying the possible reduction of synapses in patients with SAE. Recently, a novel PET tracer — [11C]UCB-J — that can be used to visualize synaptic vesicle glycoprotein 2A (SV2A) was developed107. This enables the detection of synapse loss in patients with amnestic mild cognitive impairment and in patients with epilepsy95,108. As the post-mortem analysis of synapse density may be confounded by a premorbid pathology and a post-mortem delay, minimally invasive prospective imaging of synapses would be of great interest to elucidate whether synapses might be modulated by sepsis.

Neurovascular changes

Deterioration of cognitive functions can also be explained by neurovascular changes (Fig. 2a). In patients with SAE, MRI has frequently revealed the presence of vasogenic oedema and white matter hyperintensity, both of which can be attributed to the BBB breakdown29,109,110. Consistently, abnormal BBB integrity was reported in many animal models of sepsis, which include endotoxin models111, Gram-positive bacterial infection36, polymicrobial infection (such as that induced by caecal ligation and puncture112,113) and viral infection101 (Table 1). In the kidney and liver of patients with sepsis, the integrity of endothelial tight junctions — which determines endothelial permeability — was lowered as a result of migration of leukocytes to the endothelium and the subsequent endothelial glycocalyx degradation via secreted inflammatory molecules114. A similar mechanism seems to be involved in the increased leakage of the BBB. Using a novel in vivo imaging method, it was shown that repeated LPS injections in mice on more than four consecutive days gradually increased the entry of 10 kDa dextrans, but not larger proteins (such as 40 or 70 kDa dextrans and 340 kDa fibrinogen) across the BBB during the endotoxin challenges115. The investigators suggested this was due to phagocytosis of tight junctions by activated microglia that had migrated to the blood vessels115. Another study found that high doses of endotoxin induced glycocalyx degradation, and its main constituents, namely heparan sulfate fragments, were allowed to enter the hippocampus116. Because these heparan sulfate disaccharides with specific sulfation patterns (that is, N-sulfation and 2O-sulfation) show high affinity for brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), activation of the tropomyosin receptor kinase B (TrkB) receptor by BDNF was impeded, resulting in transient deficits of long-term potentiation and fear learning116.

Fig. 2. Proposed pathological mechanisms behind SAE.

a | Blood–brain barrier (BBB) breakdown mediated by microglia during sepsis. Microglia migrate to blood vessels and remove tight junctions in the endothelium following sepsis115. This results in the extravasation of dextrans115 and heparan sulfate fragments into the brain116. If the BBB is compromised by a prior pathology such as amyloid pathology, sepsis may induce a more robust increase in BBB permeability, allowing entry of larger fibrinogen molecules along with monocytes117 and T cells151. b | Synaptic pruning by microglia via complement activation. Sepsis can activate the complement pathway and increase production of C3 by astrocytes125. Following sepsis, phosphatidylserine (PS) exposure is likely to occur and recruits C1q at synapses, which cleaves C3 to C3a and C3b in the extracellular space125,129. In parallel, C3 may accumulate at synapses for as yet unknown mechanisms97,128. Following recognition of C3a/C3b (via C3a receptor (C3aR) and complement receptor 3 (CR3))126,130 and the exposed PS (via TREM2 (refs129,131) and GPR56 (ref.132)), microglia initiate synaptic pruning. c | Nucleotide binding oligomerization domain, leucine-rich repeat and pyrin domain-containing protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome activation links sepsis to premorbid neuropathology. Sepsis can activate the NLRP3 inflammasome via pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) and cytokine receptors in the brain via systemic inflammation117,120. Because this pathway plays an important role in the pathogenesis of amyloid and tau pathology (via ASC speck formation and kinase activity153,162), sepsis may exacerbate the progression of dementia-related neuropathology. Aβ, amyloid-β; ASC, apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a caspase recruitment domain; GPR56, G-protein-coupled receptor 56; SAE, sepsis-associated encephalopathy; TREM2, triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2.

This loss of BBB integrity is congruent with the acute monocyte infiltration observed in multiple models of sepsis and systemic inflammation36,113,117. It seems that the transmigration of monocytes has a pathological relevance in SAE because abrogation of monocytes rescued long-term spatial memory and motor learning deficits following Gram-positive bacterial infection36 and exposure to poly(I:C)101. The exact mechanism of how monocyte infiltration is required for memory deficits remains poorly understood. Nevertheless, because these cells can differentiate into macrophages and dendritic cells once entering the brain, augmentation of the neuroinflammatory responses is plausible, as previously shown in mouse models of traumatic brain injury and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis118. Monocyte-derived cells might alter the synaptic plasticity because monocyte-derived macrophages seem to be capable of eliminating synapses following the induction of a focal experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis mouse model119, and depletion of monocytes, not microglia, prevented systemic poly(I:C) treatment from increasing the loss of dendritic spines in the cortex101.

SAE related to the aged brain

The heterogeneous clinical presentations and outcomes shed light on the complex nature of pathophysiology of SAE. Here, we highlight three signalling pathways that are relevant to the onset and persistence of SAE and later cognitive impairments in older patients.

The complement pathway

Considering that age is one of the main risk factors for developing adult sepsis in general, one could argue that systemic inflammation might accelerate age-related pathology in the brain, which in turn exacerbates cognitive decline. One of the pathways that is frequently suggested to contribute to sepsis is the complement pathway120. Robust activation of complement has previously been documented in the CNS after endotoxin challenge in young mice121,122. During normal healthy ageing, activation of the complement pathway gradually increases in the hippocampus, as seen by the accumulation of the complement factors C1q and C3 (refs97,123). This complement deposition coincides with a diminishment of neurons and synapses — particularly in the CA3 subfield of the hippocampus — and with the emergence of hippocampus-dependent spatial memory deficits in aged mice97,124. As these age-dependent effects on neurons can be rescued in C3-deficient mice97, we propose that activation of the complement pathway in association with sepsis may worsen age-related neuron and synapse losses. In support, a recent report demonstrated that LPS injection reduced inhibitory synaptic proteins in CA3 at 3 days after injection, affecting animal behaviour, but all of these changes were prevented by prior treatment with a C3a receptor (C3aR) antagonist125. Another study has shown that when middle-aged mice were challenged with LPS, density of excitatory synaptic puncta and that of synaptic C3 puncta were reduced in CA3 by two months post-injection, inferring that C3-tagged CA3 synapses might be destroyed during ageing102.

Moreover, the complement pathway plays a key role in synaptic pruning by microglia to remove excess numbers of synapses during development and in pathological contexts such as Alzheimer disease126–128 (Fig. 2b). Recently, this synaptic pruning was shown to require the exposure of phosphatidylserine (PS) from the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane to the outer synaptic membrane, which allows binding and accumulation of C1q at synapses129. This results in the cleavage of C3 and, finally, microglia start to eliminate the synapses via C3aR130 and complement receptor 3 (CR3)126,127. Of note, this PS exposure on the neuronal surface is also recognized by other microglial receptors to facilitate synaptic pruning (such as triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 (TREM2)129,131 and G-protein-coupled receptor 56 (GPR56)132) and is observed during apoptosis or under subtoxic stress133. Considering that neuronal apoptosis takes place in patients who survive sepsis and also in non-survivors35,39,40, PS exposure is likely to happen on neurons in parallel. We hypothesize that the exposed PS at synapses should be more efficiently tagged by complement factors, which may exacerbate synaptic pruning by microglia. Examinations of this PS exposure, especially at the level of synapses, are currently lacking. A more extensive analysis of patients with sepsis and in animal models of sepsis will be needed in the future.

The NLRP3 inflammasome

There is mounting evidence of a gradual increase in low-grade inflammation during ageing, and the resulting age-related tissue dysfunction that occurs throughout the body has been referred to as ‘inflammaging’134. One important molecular target for inflammaging is the NLRP3 inflammasome (Box 2). Whereas aged mice exhibit various alterations in their cognitive, motor and metabolic functions, together with upregulation of genes related to the NLRP3 inflammasome and complement pathways, NLRP3-deficient mice did not reveal all of these changes at 20–24 months of age135. Roles of this pathway in neuroinflammatory responses to sepsis can be inferred by the significant reduction of pro-inflammatory cytokine changes and morphological alterations of microglia when endotoxin was injected into NLRP3-deficient mice117,136. Thus, it seems plausible that sepsis can produce heightened neuroinflammatory responses in aged mice due to priming of the NLRP3 inflammasome during ageing. In support, more pronounced cytokine production in the hippocampus (including of IL-1β) and more frequent spatial learning deficits were observed in aged mice than in juvenile mice at 4–24 h post injection of LPS137–139. Further, LPS-induced reduction of dendritic spine density and impairment of long-term potentiation in the hippocampus of aged mice were prevented by pharmacological inhibition of the NLRP3 inflammasome99. Delayed neuronal loss in the substantia nigra observed at 10 months after LPS injection50 was also blocked by deficiency of NLRP3 or IL-1R1 (ref.136). Collectively, these data sets substantiate the hypothesis that the NLRP3 inflammasome is involved in chronic cerebral damage in the aged brain that occurs as a result of systemic inflammation. Because complement factors diminished in the brain of aged NLRP3-deficient mice135, it remains possible that the NLRP3 inflammasome might contribute to initiating the complement-induced cerebral disturbances.

The CX3CR1–CX3CL1 axis

One of the molecular pathways that confer neuroprotective functions on microglia is the CX3C-chemokine receptor 1 (CX3CR1)–CX3C-chemokine ligand 1 (CX3CL1) axis. CX3CR1 is predominantly expressed by microglia in the CNS140,141 and is activated by CX3CL1 that is secreted from or expressed on neurons141,142. Endotoxin challenge in CX3CR1-deficient mice induced extensive cell death in the hippocampus and more persistent effects on locomotion at 7 days post injection143,144. Notably, several rare loss-of-function single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the CX3CR1 gene have been identified in humans145–147. Hence, it seems likely that such genetic variations contribute to worsening the cognitive functions in subsets of patients with sepsis. To verify this, genome-wide association studies could reveal the candidate genes associated with the higher susceptibility of SAE and cognitive deterioration after the recovery of sepsis.

Premorbid ‘silent’ neuropathology

Importantly, even though ageing contributes to the onset or persistence of SAE, additional predisposing factors must contribute because not all patients show equal development and maintenance of cognitive impairments after sepsis8,11. Although SAE is diagnosed by the cognitive disturbances caused by sepsis, it is possible that these older individuals can possess typical hallmarks of dementia. Notably, amyloid-β (Aβ) deposition, elevation of tau proteins in the CSF (an indication of the leakage of tau from the CNS to the CSF as a result of hyperphosphorylation) and hippocampal atrophy can start 10–20 years before the onset of symptoms of Alzheimer disease148. On a post-mortem investigation, a significant portion of cognitively normal (‘reserved’) individuals demonstrate Aβ plaques and neurofibrillary tangles in the brain at an equivalent abundance to that seen in patients with Alzheimer disease149. These pre-existing neuropathologies may be necessary for the onset of persistent cognitive impairments caused by sepsis. In support, endotoxin challenge or respiratory infection by live bacteria in aged APP/PS1 mice (which harbour familial Alzheimer disease mutations in the human APP (amyloid precursor protein) and PS1 (presenilin 1) genes) resulted in more robust Il1b upregulation150 and BBB breakdown (characterized by fibrinogen deposition and infiltration of monocytes and T cells into the brain)117,151 (Fig. 2a). Furthermore, both LPS challenge and caecal ligation and puncture in APP/PS1 mice increased Aβ deposition without altering the APP processing117,152. These studies highlighted the possible roles of sepsis in aggravating the amyloid pathology through diminished phagocytosis of Aβ by microglia or increased extracellular release of apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a caspase recruitment domain (ASC) specks117, which can cross-seed Aβ and promote Aβ aggregation in vivo153 (Fig. 2c). Consistent with the roles of amyloid pathology in synapse loss128,154, LPS injection into aged APP/PS1 mice with abundant Aβ plaques resulted in greater impairment of working memory at 2 h post injection150 and a more significant reduction in dendritic spine density in the hippocampus at 3 months post injection99.

Systemic inflammation can also affect the tau pathology. In mice overexpressing the human MAPT (microtubule-associated protein tau) mutations that cause frontotemporal dementia in humans or the human wild-type MAPT gene at the expense of the endogenous murine Mapt gene (hTau mice), a single LPS injection increases tau phosphorylation155,156 and exacerbates acute and chronic motor deficits155. Likewise, when LPS was injected biweekly into young and aged triple transgenic (3×Tg) mice that manifest both amyloid and tau pathology over 6 weeks, tau phosphorylation was increased in the hippocampus without affecting the amyloid pathology157,158. In line with this, the spatial memory of LPS-injected 3×Tg mice was found to be worse at 2 days and 7 weeks post injection158,159. It should be noted that kinases involved in the LPS-induced tau phosphorylation in these animal models are mixed, and this discrepancy remains to be investigated further. Namely, p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) was suggested to be involved in hTau mice, whereas cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (CDK5) and glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β) were implicated in young and aged 3×Tg mice, respectively157,158. Similarly, LPS injection into wild-type mice demonstrated the increased tau phosphorylation in the wake of increased GSK3α, GSK3β and CDK5 activity, which was normalized at some epitopes by 4 h post injection160. However, it remained unclear whether these changes in tau phosphorylation were sustained in mouse models of tauopathy after systemic inflammation. Again, it is reasonable to assume that NLRP3 inflammasome activation is required for exaggerating the tau pathology because IL-1R antagonists can block LPS-induced and IL-1β-induced tau phosphorylation in hippocampal neurons in vitro161, and the tau pathology can be mitigated by NLRP3 deficiency in vivo162 (Fig. 2c). Furthermore, the CX3CR1–CX3CL1 axis is relevant because it has intimate associations with tau protein. LPS injection into CX3CR1-deficient hTau mice robustly increased tau phosphorylation via TLR4 and IL-1R activation156. Neuronal apoptosis in the hippocampus and behavioural changes in CX3CR1-deficient mice post LPS injection were rescued by loss of the Mapt gene144.

It is also important to highlight the consequences of systemic inflammation in the presence of ongoing neurodegeneration. Such a neurodegenerative pathology can be modelled by inoculation of prion-infected mouse brain homogenates into young mouse brain (ME7 mice), and severe synapse loss is progressively observed in the hippocampus at 16 weeks post inoculation163. When these animals were challenged with a low dose of endotoxin, severe working memory deficits were found at 3–7 h post injection91,163 and increased apoptosis in the hippocampus at 18 h post injection91. These acute behavioural and neuropathological findings were protected by treatment with an IL-1R antagonist or partly rescued in IL-1R1-deficient mice91, which further supports the necessity of the NLRP3 inflammasome in this neurodegenerative context. Additionally, whereas these ME7 mice show normal motor functions at 1 week post LPS injection, their motor functions deteriorate faster than vehicle-treated ME7 mice over a period of 4 weeks following LPS injection164. The long-term effects of systemic inflammation on cognitive functions in this model of neurodegeneration, however, remain to be fully explored.

Likewise, viral infection influences neurodegenerative pathology in various disease models. Infection of young APP/PS1 mice with non-neurotropic influenza A virus subtype H3N2 increases the plaque load and reduces the hippocampal dendritic spine density with spatial leaning deficits at 4 months post infection165. A single poly(I:C) injection into young 3×Tg mice robustly enhanced Aβ deposition and tau phosphorylation in the hippocampus by 15 months of age166. Similar to LPS challenge, a single poly(I:C) injection into ME7 mice was sufficient for promoting apoptosis induction in the hippocampus and thalamus with transient motor impairments167. Additional injections at 14, 16 and 18 weeks post inoculation accelerated the motor dysfunctions over 5 weeks after the first injection167.

Nonetheless, despite all of the consistent findings pointing towards detrimental effects of systematic inflammation on the progression of the neurodegenerative pathology, it is important to underline that neuroimaging or CSF biomarker studies that verify the preclinical studies are currently sparse. One study compared Aβ and tau protein levels in the CSF of patients who had an infection with or without delirious symptoms (n = 15 with delirium and n = 30 without delirium)106. Although the investigators did not find any differences in the Aβ42:Aβ40 ratio, total tau and phosphorylated tau protein levels106, performing a similar analysis that focuses on patients with or without sepsis or SAE will be essential in the future. Moreover, the findings of downregulated synaptic proteins in patients with delirium suggest that synapse loss can be due to the modest increase in pre-existing amyloid and/or tau pathology in the patients’ brain106. Therefore, it is recommended to image the effects of sepsis onset on the amyloid and tau pathology in patients with or without Alzheimer disease and other types of dementia.

Other perspectives of SAE

Chronic renal dysfunction in SAE

Given that renal dysfunctions are intimately associated with the acute and chronic phases of sepsis168 and with cognitive impairments in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) but without sepsis169, there is a possibility that SAE might be relevant to renal dysfunctions. Approximately two-thirds of patients with sepsis were reported to develop acute kidney injury at the time of hospital or ICU admission, and 19% of them progressed to CKD during a 1-year follow-up170,171. Development of acute kidney injury in patients with sepsis increases the risk of SAE onset in the ICU8. An earlier study also documented the elevated levels of bilirubin and blood urea nitrogen in the plasma of patients with SAE7. This is in line with evidence for renal dysfunction in animal models of sepsis that were treated with LPS172 or were infected with Gram-positive bacteria173 and polymicrobial pathogens172 (Supplementary Table 1).

In the wake of renal dysfunctions, one can speculate that elevation of uraemic toxins, which are usually filtered out by the kidney, might participate in SAE pathology. Of note, some of the uraemic toxins can cross the BBB and have neurotoxic effects169. Even without sepsis, cognitive impairments are frequent in patients with CKD, and the incidence of mild cognitive impairment is found to be twice as high in these patients as in age-matched controls169. In animal models of CKD, both an adenine-rich diet and nephrectomy are sufficient to induce cognitive impairments and disruption of the BBB174. Another study found that LPS injection 5 weeks after CKD onset in mice induced microhaemorrhages and markedly reduced expression of tight junction proteins in the brain, suggesting that BBB breakdown and ischaemia were exaggerated by LPS injections175. Taken together with the clinical studies of patients with SAE, these studies suggest that acute or chronic renal dysfunctions caused by sepsis might influence cognitive functions by contributing to pronounced BBB breakdown, and persistent SAE may be partly explained by this mechanism.

Use of sedatives

Sedative drugs (such as benzodiazepine, propofol and opioids) are commonly used for patients with sepsis who require mechanical ventilation in the ICU176 and are known to accompany the onset of delirium177. A recent multicentre prospective study (n = 1,040) found that although a majority of delirium cases can be attributed to multiple causes, approximately 90% and 72% of delirium cases recorded in the ICU are, in part, associated with the sedative administration and sepsis, respectively178. Further, those who received sedatives and developed delirium for a longer duration are more likely to present poorer cognitive performances at 3 and 12 months after the hospital discharge178. As a previous randomized controlled trial demonstrated a halved duration of delirium, to a median of 2 days, through physical exercise and mobilization during the interruptions of sedation in the ICU179, similar non-pharmacological interventions might help to prevent the persistence of delirium symptoms in patients with sepsis.

Latent virus reactivations

Another important difference between animal models and patients with sepsis is the history of prior infections. Most humans have been infected with pathogenic latent viruses in childhood and adulthood, and the dormant form of viruses can be detected in the periphery and CNS. To illustrate, HSV-1 infects more than 60% of adult humans and is capable of infecting neurons in various brain regions, including the trigeminal ganglion, frontal cortex and hippocampus180,181. Reactivation of these viruses is known to occur in the periphery of patients with sepsis25 and requires certain triggers, such as LPS challenge, exposure to pro-inflammatory cytokines or chronic immunoparalysis182,183. As all of these triggers are present when patients develop and recover from sepsis, and immune tolerance in the CNS is reported in mice that received repeated LPS injections184, it is plausible that the latent viruses are reactivated in the CNS. A recent study demonstrated that in mice previously infected with HSV-1, hyperthermic stress induced latent viral reactivation and apoptotic fragmentation of the infected neurons at the centre of microglial clusters (‘microglial nodules’) in the brain185. Hence, a comparable mechanism might be involved in the neuronal cell death and brain atrophy seen in patients with SAE. Further research needs to be carried out to investigate whether latent virus reactivation and microglial nodules are observed following the onset of sepsis.

Linking to COVID-19

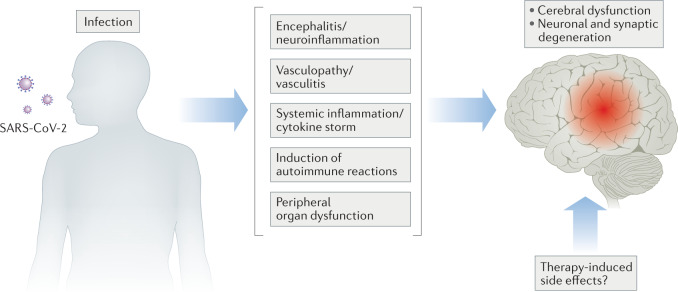

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus type 2 (SARS-CoV-2) was reported to cause viral sepsis in a majority (59%) of patients who were hospitalized with severe COVID-19 (ref.186). Similar to what is seen in patients with bacterial sepsis, more than half (55%) of patients with severe COVID-19 developed delirium in the ICU187, whereas those who survived COVID-19 (especially those who developed encephalopathy or were admitted to the ICU) showed an elevated risk of dementia onset during 6 months of follow-up188. These epidemiological data sets highlight the urgent need to understand how COVID-19 impairs cognitive functions acutely and chronically. To our best knowledge, the following pathways have been addressed: neuroinvasion of the virus, generation of anti-neuronal autoantibodies, neurovascular damage, systemic inflammation, peripheral organ dysfunction and the use of sedatives (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Mechanisms associated with neurological manifestations in patients with COVID-19.

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus type 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection can affect functioning of the brain owing to the loss of neuron and neuronal integrity by various possible mechanisms. This includes, but is not restricted to, encephalitis192,193,199,202, vasculopathy or vasculitis192,193, effects of systemic inflammation204,205, induction of autoimmune reactions199–201 and peripheral organ dysfunctions208,209. How SARS-CoV-2-directed therapies eventually affect brain function and structure also remains to be seen 187.

It is currently hotly debated whether SARS-CoV-2 can infect the brain. Whereas several investigators failed to detect the virus in brain189–192, others have reported the presence of SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins in the brain193–195. Consistent with the latter findings, human neurons in organoids, which express the viral entry receptor angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), can be infected by SARS-CoV-2 (refs195–197). Furthermore, cerebral infection was confirmed in vivo following intranasal infection of SARS-CoV-2 in mice only when the human ACE2 gene is overexpressed in the brain198,199. Analogous to what is seen in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 who have neurological complications199–201, autoantibodies were found in the brain and CSF of mice with cerebral SARS-CoV-2 infection199. Extensive characterization of these patient-derived autoantibodies revealed that they can target neurons in various brain regions and have an affinity for synaptic proteins199. This finding is in keeping with the downregulation of genes enriched in cortical excitatory synapses in the post-mortem brains from patients with COVID-19 (ref.202) and synapse loss in human neurons after SARS-CoV-2 infection in vitro197. In this sense, activation of complement and a consequent increase in synaptic pruning might contribute to the synapse loss, as has been observed in mice infected by the neuroinvasive West Nile virus203.

Alternatively, if the brain is not infected by SARS-CoV-2, it is likely that the underlying mechanisms of cognitive disturbance might be shared with those found in patients with bacterial sepsis. Post-mortem evidence for glial activation192,193 and distinct transcriptional signatures of microglia and astrocytes202, as well as elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the CSF from patients with COVID-19 and neurological symptoms199, indicated the induction of neuroinflammation after the onset of COVID-19. In the periphery, cytokine levels increased along with the disease severity204–207 and were especially high in the older subgroup of patients205. In addition, ischaemic lesions, haemorrhage and infarcts were observed in the post-mortem brains192,193, and an incidence of neurovascular lesions significantly increased within 6 months after the diagnosis of COVID-19 in the ICU188. Acute kidney injury was the most common complication in hospitalized patients with an incidence of 24%208, and 35% of survivors of COVID-19 still exhibited abnormal renal dysfunction at 6 months of follow-up209. Lastly, two-thirds of patients with COVID-19 in the ICU received sedatives during the mechanical ventilation, and the use of benzodiazepine was identified as one of the risk factors of delirium onset187. In order to prevent the long-lasting effects of COVID-19 on the CNS, future investigations will be essential for deciphering the pathogenesis on the basis of currently available knowledge about SAE.

Conclusion

It is now clear that sepsis can cause long-term sequelae that affect the cognitive functions of older patients for several years after their recovery from sepsis. The onset of delirium is common at the time of admission to the hospital or ICU. However, although many patients who survive sepsis show an apparent recovery of cognitive functions, some survivors manifest prolonged impairments, which substantially affects their quality of life. The mechanisms that drive these cognitive alterations are complex, and due to the heterogeneity of neuropathological findings seen in patients with SAE, multiple mechanisms are likely to be involved. Untangling which precise factors determine recovery from or persistence of SAE will be crucial for identifying those patients at most risk and for discovering therapeutic targets (Box 3). These factors might be related to comorbidities, genetic variations, prior infections, age-related cerebral changes and functioning of other peripheral organs. It seems likely that viral sepsis caused by SARS-CoV-2 impairs cerebral functions both acutely and chronically, likely through similar mechanisms to those involved in bacterial SAE.

Many animal models can successfully recapitulate organ dysfunctions observed in humans, including the pathologies that affect the brain, but it is also true that there are conflicting data regarding the onset of organ failures, neuronal damage and behavioural changes. In order to identify therapeutically beneficial targets for SAE, as well as for sepsis in general, standardization of animal models is needed (Box 1). Up to now, investigators in the neuroscience field tend to focus on the brain alone when studying SAE, whereas immunologists tend to overlook the cerebral effects of sepsis. Considering that sepsis can produce long-lasting sequelae that affect the functions of the peripheral organs as well as the immune system in the periphery and CNS, a more systemic approach will provide further insights into the pathology of SAE.

Box 3 Outstanding questions for the field.

What determines whether patients with sepsis present as cognitively normal or show cognitive disturbances in the intensive care unit (ICU)?

Which factors determine the persistence of sepsis-associated encephalopathy (SAE) for years after the initial sepsis onset?

Which aspects of the neuropathology contribute to the cognitive impairments seen in patients? Can synapses be affected in patients?

Are there any genetic determinants that increase the risk of SAE after the initial sepsis onset? Alternatively, is SAE associated with genetic variants that can prolong survival?

Is there a secondary hit on the central nervous system (CNS) during persistent inflammation, immunosuppression and catabolism syndrome?

If patients who survive sepsis develop moderate cognitive impairments, are they subsequently more susceptible to specific types of dementia than individuals without a history of sepsis?

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

Financial support for this article was provided by German Research Council (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft) to M.T.H. (HE 3350/11-1).

Glossary

- Sepsis

A condition characterized by organ dysfunction as a result of abnormal host responses to systemic inflammation induced by various pathogens (mostly commonly bacteria and viruses).

- Sequential Organ Failure Assessment

A scale to measure the severity and number of organ dysfunctions by rating six organ systems (that is, respiratory, cardiovascular, coagulation, renal, hepatic and nervous systems) from 0 (normal) to 4 (severe dysfunction).

- Delirium

An acute, fluctuating course of neurological symptoms characterized by inattention, altered awareness and disturbed cognition following infection, surgery and trauma.

- Sepsis-associated encephalopathy

(SAE). Sepsis-induced acute cerebral dysfunctions characterized by delirium and coma, each of which is determined by either the CAM-ICU (Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit) or DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders fifth edition) and the Glasgow Coma Scale, respectively.

- Cytokine storm

Dysregulated, pathological immune responses characterized by elevated levels of various cytokines, chemokines and plasma proteins that cause both organ dysfunction and acute inflammatory symptoms (such as fever, anorexia and fatigue).

- Persistent inflammation, immunosuppression and catabolism syndrome

The clinical phase after the cytokine storm in survivors of sepsis, determined by the duration of hospital stay, plasma C-reactive protein (CRP) levels, circulating lymphocyte number, serum albumin and creatinine height index.

- Latent viruses

Pathogenic viruses that infect and remain in the host organism for many years without producing infectious viruses.

- Glasgow Coma Scale

A scale used to categorize the levels of a patient’s loss of consciousness as mild (score of 14–15), moderate (score of 9–13) or severe (score of 3–8) by rating the motor, eye and verbal responses of the patient.

- Amyloid-β

(Aβ). Cleavage products (36–43 amino acids in length) of APP (amyloid precursor protein), encoded by the APP gene, mutations of which cause familial Alzheimer disease in humans and similar amyloid pathology (namely, amyloid plaques in the extracellular space) without inducing tau pathology and brain atrophy in transgenic and knock-in animal models.

- Tau

A microtubule binding protein, encoded by the MAPT (microtubule-associated protein tau) gene, which can dissociate from the microtubule by phosphorylation and, ultimately, aggregate inside neurons to form neurofibrillary tangles if being hyperphosphorylated (pathological hallmarks of various tauopathies, including Alzheimer disease and frontotemporal dementia).

Author contributions

T.M. and M.T.H. equally contributed to the literature search, writing and revision of this article.

Competing interests

M.T.H. belongs to an advisory board at IFM Therapeutics and Alector. T.M. declares no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information

Nature Reviews Immunology thanks J.-L. Vincent and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41577-021-00643-7.

References

- 1.Singer M, et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3) JAMA. 2016;315:801–810. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rudd KE, et al. Global, regional, and national sepsis incidence and mortality, 1990–2017: analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 2020;395:200–211. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32989-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ljungström L, Andersson R, Jacobsson G. Incidences of community onset severe sepsis, Sepsis-3 sepsis, and bacteremia in Sweden — a prospective population-based study. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0225700. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0225700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prescott HC, Angus DC. Enhancing recovery from sepsis: a review. JAMA. 2018;319:62–75. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.17687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yende S, et al. Long-term host immune response trajectories among hospitalized patients with sepsis. JAMA Netw. Open. 2019;2:e198686. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.8686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Louveau A, Harris TH, Kipnis J. Revisiting the mechanisms of CNS immune privilege. Trends Immunol. 2015;36:569–577. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2015.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eidelman LA, Putterman D, Putterman C, Sprung CL. The spectrum of septic encephalopathy: definitions, etiologies, and mortalities. JAMA. 1996;275:470–473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sonneville R, et al. Potentially modifiable factors contributing to sepsis-associated encephalopathy. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43:1075–1084. doi: 10.1007/s00134-017-4807-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Inouye SK, et al. Postoperative delirium in older adults: best practice statement from the American Geriatrics Society. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2015;220:136–148.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2014.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Widmann CN, Heneka MT. Long-term cerebral consequences of sepsis. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13:630–636. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70017-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fritze T, Doblhammer G, Widmann CN, Heneka MT. Time course of dementia following sepsis in German health claims data. Neurol. Neuroimmunol. Neuroinflamm. 2021;8:e911. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heneka MT, Golenbock DT, Latz E. Innate immunity in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Immunol. 2015;16:229–236. doi: 10.1038/ni.3102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fletcher JM, Lalor SJ, Sweeney CM, Tubridy N, Mills KHG. T cells in multiple sclerosis and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2010;162:1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04143.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin GS, Mannino DM, Eaton S, Moss M. The epidemiology of sepsis in the United States from 1979 through 2000. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:1546–1554. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vincent J-L, et al. Prevalence and outcomes of infection among patients in intensive care units in 2017. JAMA. 2020;323:1478–1487. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ranzani OT, et al. New sepsis definition (Sepsis-3) and community-acquired pneumonia mortality. A validation and clinical decision-making study. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2017;196:1287–1297. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201611-2262OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jain S, et al. Community-acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization among U.S. adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;373:415–427. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1500245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Southeast Asia Infectious Disease Clinical Research Network Causes and outcomes of sepsis in Southeast Asia: a multinational multicentre cross-sectional study. Lancet Glob. Health. 2017;5:e157–e167. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30007-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hotchkiss RS, et al. Sepsis and septic shock. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2016;2:16045. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fajgenbaum DC, June CH. Cytokine storm. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;383:2255–2273. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra2026131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stortz JA, et al. Benchmarking clinical outcomes and the immunocatabolic phenotype of chronic critical illness after sepsis in surgical intensive care unit patients. J. Trauma. Acute Care Surg. 2018;84:342–349. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gentile LF, et al. Persistent inflammation and immunosuppression: a common syndrome and new horizon for surgical intensive care. J. Trauma. Acute Care Surg. 2012;72:1491–1501. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318256e000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prescott HC, Langa KM, Iwashyna TJ. Readmission diagnoses after hospitalization for severe sepsis and other acute medical conditions. JAMA. 2015;313:1055–1057. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.1410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hotchkiss RS, Coopersmith CM, McDunn JE, Ferguson TA. Tilting toward immunosuppression. Nat. Med. 2009;15:496–497. doi: 10.1038/nm0509-496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walton AH, et al. Reactivation of multiple viruses in patients with sepsis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e98819. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang Y, et al. Mitochondrial DNA haplogroup R in the Han population and recovery from septic encephalopathy. Intensive Care Med. 2011;37:1613–1619. doi: 10.1007/s00134-011-2319-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muzambi R, et al. Assessment of common infections and incident dementia using UK primary and secondary care data: a historical cohort study. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2021;2:e426–e435. doi: 10.1016/S2666-7568(21)00118-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iwashyna TJ, Ely EW, Smith DM, Langa KM. Long-term cognitive impairment and functional disability among survivors of severe sepsis. JAMA. 2010;304:1787–1794. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stubbs DJ, Yamamoto AK, Menon DK. Imaging in sepsis-associated encephalopathy — insights and opportunities. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2013;9:551–561. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2013.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hosokawa K, et al. Clinical neurophysiological assessment of sepsis-associated brain dysfunction: a systematic review. Crit. Care. 2014;18:674. doi: 10.1186/s13054-014-0674-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ehler J, et al. The prognostic value of neurofilament levels in patients with sepsis-associated encephalopathy — a prospective, pilot observational study. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0211184. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0211184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mattsson N, Cullen NC, Andreasson U, Zetterberg H, Blennow K. Association between longitudinal plasma neurofilament light and neurodegeneration in patients with Alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76:791–799. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.0765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mielke MM, et al. Plasma and CSF neurofilament light: relation to longitudinal neuroimaging and cognitive measures. Neurology. 2019;93:e252–e260. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nguyen DN, et al. Elevated serum levels of S-100β protein and neuron-specific enolase are associated with brain injury in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock. Crit. Care Med. 2006;34:1967–1974. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000217218.51381.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Semmler A, et al. Persistent cognitive impairment, hippocampal atrophy and EEG changes in sepsis survivors. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2013;84:62–69. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2012-302883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Andonegui G, et al. Targeting inflammatory monocytes in sepsis-associated encephalopathy and long-term cognitive impairment. JCI Insight. 2018;3:e99364. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.99364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gunther ML, et al. The association between brain volumes, delirium duration, and cognitive outcomes in intensive care unit survivors: the VISIONS cohort magnetic resonance imaging study. Crit. Care Med. 2012;40:2022–2032. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318250acc0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Orhun G, et al. Brain volume changes in patients with acute brain dysfunction due to sepsis. Neurocrit. Care. 2020;32:459–468. doi: 10.1007/s12028-019-00759-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sharshar T, et al. Apoptosis of neurons in cardiovascular autonomic centres triggered by inducible nitric oxide synthase after death from septic shock. Lancet. 2003;362:1799–1805. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)14899-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sharshar T, et al. The neuropathology of septic shock. Brain Pathol. 2004;14:21–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2004.tb00494.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee JW, et al. Neuro-inflammation induced by lipopolysaccharide causes cognitive impairment through enhancement of β-amyloid generation. J. Neuroinflammation. 2008;5:37. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-5-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Semmler A, et al. Sepsis causes neuroinflammation and concomitant decrease of cerebral metabolism. J. Neuroinflammation. 2008;5:38. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-5-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Laflamme N, Echchannaoui H, Landmann R, Rivest S. Cooperation between Toll-like receptor 2 and 4 in the brain of mice challenged with cell wall components derived from Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria. Eur. J. Immunol. 2003;33:1127–1138. doi: 10.1002/eji.200323821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Laflamme N, Rivest S. Toll-like receptor 4: the missing link of the cerebral innate immune response triggered by circulating Gram-negative bacterial cell wall components. FASEB J. 2001;15:155–163. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0339com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Banks WA, Robinson SM. Minimal penetration of lipopolysaccharide across the murine blood–brain barrier. Brain Behav. Immun. 2010;24:102–109. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Banks WA, Ortiz L, Plotkin SR, Kastin AJ. Human interleukin (IL) 1α, murine IL-1α and murine IL-1β are transported from blood to brain in the mouse by a shared saturable mechanism. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1991;259:988–996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Banks WA, Kastin AJ, Gutierrez EG. Penetration of interleukin-6 across the murine blood–brain barrier. Neurosci. Lett. 1994;179:53–56. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(94)90933-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gutierrez EG, Banks WA, Kastin AJ. Murine tumor necrosis factor α is transported from blood to brain in the mouse. J. Neuroimmunol. 1993;47:169–176. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(93)90027-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]