Abstract

Asthma, a chronic respiratory disease involving variable airflow limitations, exhibits two phenotypes: eosinophilic and neutrophilic. The asthma phenotype must be considered because the prognosis and drug responsiveness of eosinophilic and neutrophilic asthma differ. CD4+ T cells are the main determinant of asthma phenotype. Th2, Th9 and Tfh cells mediate the development of eosinophilic asthma, whereas Th1 and Th17 cells mediate the development of neutrophilic asthma. Elucidating the biological roles of CD4+ T cells is thus essential for developing effective asthma treatments and predicting a patient’s prognosis. Commensal bacteria also play a key role in the pathogenesis of asthma. Beneficial bacteria within the host act to suppress asthma, whereas harmful bacteria exacerbate asthma. Recent literature indicates that imbalances between beneficial and harmful bacteria affect the differentiation of CD4+ T cells, leading to the development of asthma. Correcting bacterial imbalances using probiotics reportedly improves asthma symptoms. In this review, we investigate the effects of crosstalk between the microbiota and CD4+ T cells on the development of asthma.

Keywords: asthma, T cell, eosinophil, neutrophil, microbiota, commensal, dysbiosis

1. Introduction

Asthma is a common respiratory disease involving chronic airway inflammation, primarily caused by allergens such as house dust mites (HDMs), pollen, and animal dander [1]. In general, the prevalence of asthma is approximately 15–20%, but this varies by country [2]. Chronic inflammation resulting from continuous inhalation of allergens can lead to airway remodeling, which in turn can induce various symptoms associated with asthma, such as cough, dyspnea, and wheezing due to airway narrowing [1].

Steroids are often prescribed to control airway inflammation and represent the gold standard for asthma treatment [3]. Although steroid use has improved the quality of life of many asthma patients [4], some patients with severe asthma are refractory to current steroid treatment protocols [3]. These severe asthma patients have poorer quality of life due to a higher frequency of asthma attacks [5]. A variety of drugs for treating severe asthma have been developed in recent years, including mepolizumab, reslizumab, benralizumab and dupilumab [6]. However, these drugs were developed for patients with T helper (Th)2 asthma, and unfortunately, no drugs for patients with non–Th2-asthma are currently available. Thus, novel therapeutic targets for drugs to treat non–Th2-asthma are needed, but the development of such drugs will require elucidation of the mechanism underlying the role of CD4+ T cells in asthma pathogenesis.

Two asthma phenotypes have been described, Th2 and non-Th2, which are determined by CD4+ T cells [7]. The asthma phenotype can change depending on which type of CD4 T cell is differentiated; consequently, the response to asthma drugs can change accordingly [8]. Th2-asthma (i.e., eosinophilic asthma) is characterized by eosinophilic infiltrate in the sputum [7]. The pathogenesis of eosinophilic asthma is characterized by secretion of high levels of interleukin (IL)-4, IL-5 and IL-13 by Th2 cells [1]. In general, eosinophilic asthma is responsive to steroid treatment, and severe eosinophilic asthma is effectively treated by various newly developed drugs [5]. Non-Th2 asthma (i.e., neutrophilic asthma), by contrast, is characterized by neutrophilic infiltrate in the sputum [7] and secretion of high levels of interferon gamma (IFN-γ) and IL-17 by Th1 and Th17 cells. In contrast to Th2-asthma, non-Th2 asthma does not respond steroids or newly developed asthma drugs [7]. As the disease progression pattern and asthma treatment options differ depending on the differentiation of CD4+ T cells, elucidating the biological roles of CD4+ T cells in the pathogenesis of asthma is critical for developing effective asthma treatments and predicting patient prognosis.

Although CD4+ T cells and other immune cells play key roles in the pathogenesis of asthma, several studies have reported a relationship between the host microbiota and asthma [9,10,11]. Commensal bacteria, which constitute a subtype of the microbiota, are symbiotic bacteria [12]. An adult male weighing 70 kg reportedly harbors approximately 3.8 × 1013 commensal bacteria [13]. Approximately 29% of commensal bacteria reside in the gastrointestinal tract, 26% in the oral cavity, 21% on the skin, 14% in the airways, 9% in the urogenital tract, and 1% in the blood [12]. Commensal bacteria perform a variety of biological functions important to the host, including fermentation of undigested dietary carbohydrates, synthesis of bile acids and vitamins, and immune surveillance [14]. Importantly, alterations in the composition of commensal bacteria have been associated with various chronic inflammatory diseases, such as asthma, inflammatory bowel disease, and obesity [15]. Recent literature indicates that the composition of beneficial and harmful bacteria in the host determines the disease pattern of asthma [16]. The same study revealed that various environmental factors that affect these bacteria also affect the differentiation of CD4+ T cells, resulting in the development of asthma [16].

In this review, we discuss the detailed mechanism of the pathogenesis of asthma as it relates to Th2-asthma and non-Th2 asthma, with a particular focus on CD4+ T cells. In addition, we discuss the role of the bacterial microbiota in the induction of asthma and its effect on CD4+ T cells in asthma.

2. Th2-Asthma with Eosinophilic Inflammation

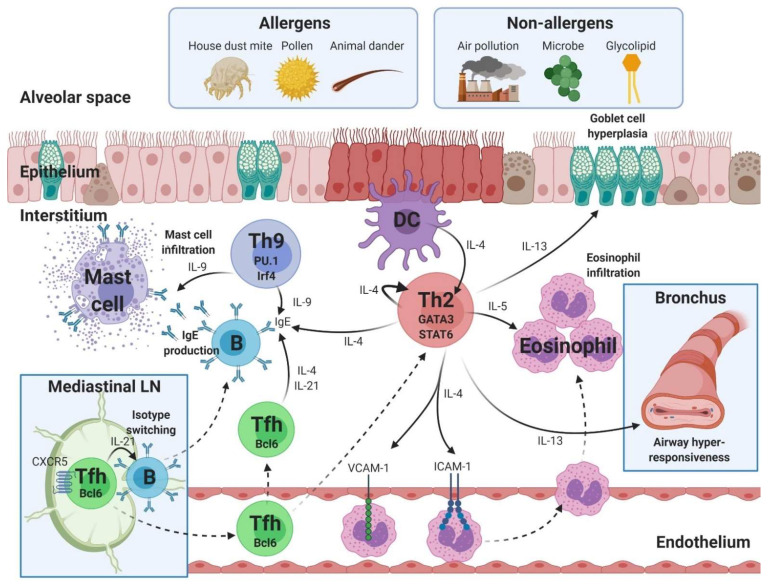

Th2 cells play a central role in the development of Th2-asthma [17]. The hallmark of Th2-asthma is infiltration of the airways by eosinophils. Eosinophilic asthma is diagnosed when the proportion of eosinophils in the sputum is >3% [17]. Th2-asthma can be caused by allergens and non-allergens, including pollutants, microbes, and glycolipids [18]. Approximately 50% of asthmatic adults have Th2-asthma [5]. Although various immune cells are involved in the pathogenesis of Th2-asthma, the Th2, Th9, and T follicular helper cell (Tfh) CD4+ T cell subtypes play particularly key roles (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Pathogenesis of eosinophilic asthma mediated by T helper (Th)2, Th9 and T follicular helper (Tfh) cells. The development of eosinophilic asthma is associated with the Th2, Th9 and Tfh subtypes of CD4+ T cells. Th2 cells play roles in eosinophilic infiltration, goblet cell hyperplasia, airway hyperresponsiveness, immunoglobulin (Ig)E production, and upregulation of endothelial molecules, including vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM)-1 and intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1. GATA-binding protein 3 (GATA3) and signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)6 are transcriptional factors in Th2 cells. Th9 cells mediate mast cell infiltration and IgE production. PU and Irf4 are transcriptional factors in Th9 cells. Bcl6-expressing Tfh cells mediate isotype switching and IgE production. Text color: Black, cytokine. LN, lymph node; DC, dendritic cell; IL, interleukin; Irf4, interferon regulatory factor 4; CXCR5, C-X-C chemokine receptor type 5. Figure created using BioRender.com (accessed on 6 September 2021).

2.1. Th2 Cells

Th2 cells constitute a subtype of CD4+ T cells [19]. Th2 differentiate in response to IL-4 secreted by dendritic cells (DCs), and innate lymphoid cell group 2 (ILC2) promotes the expression of master transcription factors such as GATA-binding protein 3 (GATA3) and signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)6 [19]. Differentiated Th2 cells defend the host against extracellular parasites and secrete various Th2 cytokines, including IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13 [20].

Th2 cytokines play a major role in airway eosinophilic infiltration in Th2-asthma [21]. Compared with healthy control subjects, expression of the Th2 cytokine-related genes IL-5, GPR55, and ELAVL1 is upregulated in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) of asthma patients [22].

IL-4 secreted by Th2 cells binds to the IL-4 receptor (IL-4R) in an autocrine manner to continuously initiate Th2 differentiation [23]. Th2-derived IL-4 also promotes allergen-specific immunoglobulin (Ig)E class switching in B cells [24], and upregulates the expression of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM)-1 in endothelial cells in the lungs, resulting in eosinophil recruitment [24].

IL-5 also plays a critical role in eosinophilic inflammation [25]. Foster et al. reported that IL-5–deficient mice exhibit reduced airway eosinophilia despite allergen-induced allergic inflammation [26]. In the bone marrow, IL-5 promotes the differentiation of myeloid precursor cells to mature eosinophils [27]. Circulating mature eosinophils that were triggered to differentiate by IL-5 then adhere to VCAM-1 on endothelial cells and migrate to the bronchial lumen [28]. Accumulation of mature eosinophils in the bronchial lumen exacerbates eosinophilic asthma because activation of Jak2 and Raf-1 inhibits eosinophil apoptosis [25]. In addition, eosinophil survival is prolonged due to the upregulation of mitogen-activated protein kinase genes [25].

IL-13 plays an important role in airway remodeling [29]. IL-13–STAT6 signaling in human epithelial cells induces goblet cell hyperplasia via the upregulation of the mucin 5AC gene [30]. In addition, IL-13 promotes airway hyperresponsiveness, which is aggravated narrowing of the airways in response to external stimuli, by upregulating smooth muscle cell contractility and pulmonary fibrosis [31].

As Th2 cytokines have a marked effect on the occurrence of eosinophilic asthma, various therapeutic agents targeting Th2 cytokines have been developed [6]. Current Th2 cytokine–targeted therapies approved by the Food and Drug Administration can be divided into two classes: drugs that target cytokines (e.g., mepolizumab and reslizumab), and drugs that target cytokine-binding receptors (e.g., benralizumab and dupilumab).

Mepolizumab, an IgG1 monoclonal antibody targeting IL-5, is administered via subcutaneous injection of 100 mg every 4 weeks [6]. Compared with the placebo, mepolizumab reduced glucocorticoid and asthma exacerbation in patients with eosinophilic asthma [32,33]. Reslizumab, an IgG4 monoclonal antibody targeting IL-5, is administered via intravenous injection of 3 mg/kg every 4 weeks [6]. Reslizumab also reduces the number of acute exacerbations and the amount of maintenance steroids required in patients with moderate to severe eosinophilic asthma [34].

Benralizumab, a humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody targeting IL-5 receptor α, is administered via subcutaneous injection of 30 mg every 8 weeks [6]. Compared with the placebo, benralizumab decreased glucocorticoid use by 75% and decreased the number of asthma exacerbations by 70% in patients with severe eosinophilic asthma [35]. Dupilumab, an IL-4Rα antagonist, is administered via subcutaneous injection every 2 weeks [36]. Compared with the placebo, dupilumab decreased the number of asthma exacerbations by 47.7% in patients with moderate to severe uncontrolled asthma [36]. Furthermore, dupilumab improves lung function, which has not been demonstrated with the other Th2 cytokine–targeted therapies [36]. After 12 weeks of dupilumab use, an improvement in forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) was observed, with an average increase in FEV1 of 0.32 L [36].

In addition to these cytokines and cytokine-binding receptor-targeted therapy, drugs targeting Th2 transcription factors are also under development [37]. For example, SB010, a GATA3-specific DNAzyme that inhibits transcription of the GATA3 gene, improved lung function and decreased plasma IL-5 levels compared with the placebo [38]. However, that study had several limitations, such as the small study group involving only 40 asthma patients [38]. Large-scale studies of SB010 targeting patients with severe eosinophilic asthma are thus needed.

2.2. Th9 Cells

Recent reports suggest that Th9 cells induce allergic reactions and inflammatory responses [39]. Th9 cells are a subset of CD4+ T cells that secrete IL-9 and were initially thought to be a subtype of Th2 cells [40]. However, research has revealed that Th9 cells do not produce IL-4, Il-5, or IL-13 and only secrete IL-9 [41]. In addition, Th9 cells express PU.1 and interferon regulatory factor 4 (Irf4) as transcription factors [42]. Th9 cells are therefore recognized as a new subtype of CD4+ T cells due to differences compared with conventional Th2 cells in terms of the cytokines and transcription factors produced [41].

Th9-derived IL-9 plays an important role in the development of eosinophilic asthma by assisting the action of Th2 cells [21]. For example, IL-9 enhances IgE production by B cells in conjunction with Th2-derived IL-4. Petit-Frere et al. reported that simultaneous administration of IL-4 and IL-9 exhibited synergistic effects that resulted in upregulation of IgE production [43]. McLane et al. reported that serum IgE levels were elevated in IL-9 transgenic mice compared with normal mice [44]. Analyses of PBMCs isolated from patients with allergen-induced asthma revealed a positive correlation between the number of Th9 cells and plasma IgE level [45]. Other studies found that IL-9 exacerbates eosinophilic inflammation by amplifying the effects of Th2 cytokines. Temann et al. found that compared with normal mice, transgenic mice overexpressing IL-9 exhibited increased production of Th2 cytokines, including IL-5 and IL-13 [46]. The increased levels of IL-5 and IL-13 resulting from IL-9 stimulation increase eosinopoiesis in the bone marrow and enhance goblet cell metaplasia of epithelial cells [47,48]. Chang et al. reported that mice with T cell-specific deletion of PU.1 exhibit reduced OVA-induced eosinophilic inflammation compared with wild-type mice [49].

A unique role of IL-9 compared with Th2 cytokines is the effect on the infiltration of mast cells in lungs. It was previously thought that Th2 cytokines, including IL-4 and IL-13, were responsible for mastocytosis [50]. However, Sehra et al. demonstrated that IL-9 derived from Th9 cells regulates mast cell infiltration in the lungs [51]. Using adoptive Th9 transfer, they found that only IL-9 blockade—and not IL-13 blockade—effectively reduced the infiltration of mast cells in the lungs [51].

Several murine studies examining IL-9 blockade demonstrated effective improvement in eosinophilic asthma factors such as inflammation, suggesting that IL-9 is a novel therapeutic target for treating eosinophilic asthma [52,53]. Unfortunately, however, a randomized controlled trial involving over 300 asthma patients did not find any beneficial improvement in asthma symptoms and lung function compared with the placebo group in patients treated with MEDI-528, a humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody that inhibits the function of IL-9 [54]. JQ1, a bromodomain-containing protein 4 inhibitor that suppresses chromatin looping, resulting in reduced IL-9 transcription, has attracted recent attention for its potential in Th9 cell-targeted therapies [55]. In a murine study performed by Xiao et al., JQ1 alleviated OVA-induced allergic inflammation [56]. However, the short half-life of JQ1 currently poses an obstacle to clinical use [57]. Therefore, it will be necessary to develop improved Th9 cell-targeted drugs that can be used in asthma patients.

2.3. Tfh Cells

Tfh cells constitute a subset of CD4+ T cells that localize primarily in lymphoid tissues and function as key regulators of B-cell functions, including proliferation, cytokine production, and isotype switching [58]. When DCs secrete IL-6 in lymphoid tissues after allergen binding, naïve CD4+ T cells differentiate into C-X-C chemokine receptor type 5 (CXCR5)-expressing Tfh cells [59]. Regulated by the transcription factor B-cell lymphoma 6 (Bcl6), Tfh cells then secrete IL-4 and IL-21 [60].

Tfh-derived cytokines are major stimulators of IgE production by B cells. Previous studies indicated that IL-4 and IL-9 are involved in IgE production [61]. Kobayashi et al. reported reduced levels of serum IgE in T cell-specific Bcl6-depleted mice compared with control mice, despite no changes in levels of Th2 cytokines such as IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 [62]. Noble and Zhao reported abnormalities in class switching of IgG as well as IgE in T cell-specific IL-6R mutant mice [63]. A study in humans reported a positive correlation between circulating Tfh cells and HDM-specific IgE [64]. These results suggest that Tfh cells—but not Th2 cells—play an important role in IgE production.

Tfh cells also play a role in amplifying the effects of Th2 cytokines during the induction of Th2-asthma. Two hypotheses have been proposed to explain this phenomenon. The first hypothesis holds that peripheral Tfh cells, which do not express CXCR5, migrate directly from the mediastinal lymph nodes to the lungs. The second hypothesis holds that Tfh cells are transformed into pathogenic Th2 cells. Using IL-21–green fluorescent protein reporter mice, Coquet et al. concluded that IL-21–producing cells presumed to be of Tfh origin localize in lungs and amplify Th2 cell responses via the binding of IL-21 to IL-21R on Th2 cells [65]. In contrast, Ballesteros-Tato et al. reported that IL-4–producing Tfh cells can differentiate into precursors of pathogenic Th2 cells [66].

Two types of therapeutics targeting Tfh cells have been developed: an inducible T-cell costimulatory (ICOS) ligand–targeted antibody, and a CXCR5-targeted therapy. Uwadiae et al. reported that the ICOS ligand–targeted antibody alleviated HDM-induced eosinophilic inflammation in a murine model [67]. Using PBMCs isolated from asthma patients and healthy controls, Zhang et al. reported that miR-192, a small, non-coding RNA that regulates CXCR5 expression, inhibits the function of Tfh cells [68]. Because Tfh cell-targeted therapies are still in the experimental stage, clinical trials of the ICOS ligand–targeted antibody and miR-192 are in progress.

3. Non-Th2 Asthma with Neutrophilic Inflammation

Non–Th2 asthma refers to asthma involving <3% eosinophilic infiltration in the sputum [7]. Fewer than 50% of asthma patients are diagnosed with non–Th2 asthma, which primarily occurs in adulthood [69]. Non–Th2 asthma is induced by non-allergenic factors such as smoking, air pollution, inhaled ozone, and infection [7]. Patients with non–Th2 asthma suffer from poor asthma control and experience frequent exacerbations of asthma symptoms due to the development of medication resistance [70]. Neutrophil infiltration is a key characteristic of patients presenting with non–Th2-asthma. Among the CD4+ T cell subsets, Th17 and Th1 cells reportedly play important roles in neutrophil infiltration of the airways (Figure 2) [7].

Figure 2.

Pathogenesis of neutrophilic asthma mediated by Th1 and Th17 cells. The development of neutrophilic asthma is associated with subtypes of CD4+ T cells including Th1 and Th17 cells. Th1 cells are involved in mediating the infiltration of neutrophils and the formation of emphysematous lung. T-bet, STAT1, and STAT4 are transcriptional factors in Th1 cells. Th17 cells play critical roles in neutrophil infiltration, airway remodeling, collagen deposition, and airway hyperresponsiveness. RORγt and STAT3 are transcriptional factors in Th17 cells. Text color: Black, cytokine; Red, chemokine; Blue, anti-protease. T-bet, T-box protein expressed in T cells; RORγt, RAR-related orphan receptor gamma; CXCL, C-X-C motif chemokine ligand; SLPI, secretory leukocyte peptidase inhibitor. The figure was created using BioRender.com (accessed on 6 September 2021).

3.1. Th17 Cells

Th17 cells exert a significant effect on neutrophilic inflammation during the development of asthma [7]. Th17 cells secrete IL-17A, IL-17F, and IL-22 as part of the response against extracellular pathogens and fungi. In addition, Th17 cells express the transcription factors STAT3, RAR-related orphan receptor gamma (RORγt), and RORα [20]. To differentiate Th17 cells, IL-6, IL-23, and TGF-β are required [19].

Th17 cytokines such as IL-17A, IL-17F, and IL-22 promote neutrophil recruitment in the airways. Studies in human cell lines reported that exposure to IL-17 enhances the secretion of neutrophil chemotaxis factors such as C-X-C motif chemokine ligand (CXCL)1 and CXCL8 by stimulating epithelial cells and fibrocytes [71,72,73]. Newcomb et al. found reduced neutrophil infiltration in the airways of IL-17A–knockout mice [74]. Camargo et al. reported that blockade of IL-17 reduces lipopolysaccharide-induced neutrophilic inflammation in the airways of mice [75].

Th17 cytokines are also involved in airway remodeling and hyperresponsiveness via binding to IL-17RA and IL-17RC on airway smooth muscle cells [76,77,78]. In an animal model study of airway remodeling, Ramakrishnan et al. demonstrated that IL-17-induces autophagy in fibroblasts, which initiates mitochondrial dysfunction that results in collagen deposition [79]. In a study examining hyperresponsiveness, Chiba et al. reported that the complex formed by the binding of IL-17A to the IL-17R on smooth muscle cells stimulates increased production of RhoA protein, which plays a role in upregulating intracellular calcium concentrations, resulting in enhanced smooth muscle cell contractility [80]. These data from murine studies suggest that antibodies targeting IL-17A would reduce airway remodeling and airway hyperresponsiveness [75,81].

Several other studies have reported a link between steroid resistance and Th17 [82,83]. Two hypotheses have been proposed to explain this possible relationship. The first hypothesis involves the steroid resistance of Th17 cells, whereas Th2 cells are sensitive to steroids. The second hypothesis suggests that steroids promote Th17 cell differentiation. Nanzer et al. examined PBMCs of asthma patients and showed that steroids did not inhibit cytokine synthesis by Th17 cells, in contrast to PBMCs of healthy controls [82]. However, Chambers et al. reported that steroid dose-dependent Th17 cytokine synthesis plays a role in in vitro activation of human PBMCs [83]. These data explain the high proportion of Th17 cells in asthma patients with steroid resistance.

Unfortunately, antibody-based therapy targeting IL-17A did not improve asthma symptoms in clinical trials [84]. However, treatment of a patient with chronic psoriasis and asthma with ustekinumab, a humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody targeting both IL-12 and IL-23, resulted in improvement in asthma symptoms and a reduction in asthma maintenance medication [85]. Collectively, the above results suggest that alleviating Th17-related asthma requires the control of not just one Th17 cytokine pathway but all pathways that simultaneously regulate Th17 cytokines.

3.2. Th1 Cells

Th1 cells are also major inducers of neutrophilic inflammation in non–Th2-asthma. Th1 cells function in protecting host tissues against intracellular bacteria and viruses [20]. Th1 transcription factors include STAT1, STAT4, and T-bet (T-box protein expressed in T cells) [86]. Th1 cells, which differentiate in response to IL-12, secrete IFN-γ [20].

According to the hygiene hypothesis, Th1 cells inhibit the development of eosinophilic asthma, whereas Th2 cells promote the development of eosinophilic asthma [87]. However, recent studies reported that Th1 cells play an important role in the pathogenesis of severe non–Th2-asthma. Cui et al. reported that administration of OVA-specific Th1 aggravated neutrophilic inflammation in the lungs [88]. Raundhal et al. reported increased levels of the Th1 cytokine IFN-γ in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of non–Th2-asthma patients [89]. Additionally, increased neutrophilic infiltration and IFN-γ mRNA expression in the sputum were observed in patients with severe asthma compared with patients with mild to moderate asthma [90]. These data suggest that Th1 cells play a role in the pathogenesis of severe non–Th2-asthma.

Th1 cell-derived IFN-γ is associated with airway hyperresponsiveness and pathologic changes in the lungs. Raundhal et al. found that IFN-γ reduces the expression of secretory leukocyte peptidase inhibitor, which neutralizes proteases in epithelial cells, thus aggravating airway hyperresponsiveness [89]. IFN-γ transgenic mice expressing high levels of IFN-γ developed emphysematous lungs, which is frequently observed in asthma–chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) overlap [91]. In the future, it will be necessary to develop new asthma treatments targeting Th1 cells.

4. Beneficial and Harmful Bacteria in the Pathogenesis of Asthma

Many species of bacteria live in symbiosis with hosts and play an important role in the development of asthma [92]. Beneficial species of bacteria suppress asthma, whereas harmful bacteria induce asthma [93]. In this section, we summarize the roles of these two types of bacteria in the pathogenesis of asthma.

4.1. Beneficial Bacteria with Anti-Asthmatic Effects

Beneficial bacteria include symbiotic species of the genera Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, Lachnospira and Akkermansia. Fermented foods such as yogurt and kimchi contain numerous beneficial bacteria [94,95]. Recently, probiotic products incorporating these beneficial bacteria have been used to reduce the risk of asthma [16].

Members of the genus Lactobacillus are gram-positive anaerobic bacteria that play a protective role in the pathogenesis of asthma. Spacova et al. reported that intranasal administration of Lactobacillus rhamnosus alleviated pollen-induced eosinophilic inflammation in the lungs [96]. According to Li et al., butyrate, a short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) generated from the fermentation of fiber by L. reuteri, exhibits anti-inflammatory activity in patients with asthma [97]. In a randomized, placebo-controlled study, the asthma patients group who received L. gasseri A5 daily for 2 months exhibited higher lung function scores (peak expiratory flow rate) and lower clinical symptom scores, indicating improvement in asthma compared with patients who received the placebo [98].

Members of the genus Bifidobacterium are Gram-positive anaerobic bacteria that exert immunomodulatory effects that suppress the development of asthma. In a study by Raftis et al., Bifidobacterium breve strain MRx0004 suppressed HDM-induced inflammation and the number of eosinophils and neutrophils [99]. Administration of Bifidobacterium upregulates IL-10–producing regulatory T cells (Tregs), a type of CD4+ T cell that suppresses hyper-activation of immune responses [100]. In a randomized controlled study of pediatric asthma patients, administration of a Bifidobacterium mixture resulted in improvement in clinical symptoms and quality of life compared with patients who received the placebo [101].

Members of the genus Lachnospira are gram-positive anaerobic bacteria that function as major producers of SCFAs such as acetate, propionate, and butyrate [102]. These SCFAs bind to G-protein–coupled receptor (GPR) 43 on the surface of naïve CD4+ T cells [103]. The SCFA-GPR43 complex, in turn, promotes acetylation of the Treg transcription factor Foxp3 by suppressing histone deacetylase (HDAC) in naïve CD4+ T cells [104]. Arrieta et al. found that fecal transplantation with a mixture of Lachnospira reduced OVA-induced neutrophilic inflammation to a greater degree than the control [105]. It is possible that increased levels of SCFAs produced by Lachnospira enhance Treg differentiation and suppress pathogenic immune cells.

Members of the genus Akkermansia are gram-negative anaerobic bacteria that inhibit the development of asthma by promoting differentiation of Treg [106]. In a study by Kuczma et al., Akkermansia-derived antigenic peptide-induced anergy of T cells and increased the peripheral Treg population [107]. Michalovich et al. showed that oral administration of A. muciniphila reduced OVA-induced eosinophilic inflammation [106]. In a cross-sectional case-controlled study, A. muciniphila was decreased in the stool of asthma patients compared to healthy controls [108]. In addition, the fecal concentration of A. muciniphila was negatively correlated with asthma severity [106]. These results suggest that Akkermansia plays a protective role in the development of asthma.

Other bacteria also reportedly exert beneficial effects in inhibiting the induction of asthma, including members of the genera Veillonella, Faecalibacterium and Rothia [93].

4.2. Harmful Bacteria with Pro-Asthmatic Effects

Bacteria that exert harmful effects with respect to asthma include pathogens of the genera Clostridium, Staphylococcus and Pseudomonas. Under certain conditions, these harmful bacteria reportedly exacerbate enterocolitis and pneumonia [109,110]. Additionally, colonization by harmful bacteria reportedly increases the risk of asthma development [16].

Members of the genus Clostridium are gram-positive anaerobic bacteria that reportedly aggravate asthma. Nimwegen et al. reported that colonization by Clostridium difficile within 1 month after birth is associated with an increased risk of developing childhood asthma [111]. In a pediatric cohort study, asthma patients exhibited higher numbers of C. neonatale [112]. Colonization by Clostridium species was positively correlated with fecal IgE levels in a childhood asthma study, indicating that the presence of Clostridium increases the risk of asthma [113]. Although the detailed mechanism of the role of Clostridium in asthma pathogenesis has not been elucidated, infections involving Clostridium could cause excessive inflammation and increase the pathologic immune cells, thereby worsening asthma.

Members of the genus Staphylococcus are gram-positive bacteria that induce eosinophilic asthma. Stentzel et al. demonstrated that serine protease–like proteins (Spls), extracellular proteases expressed by Staphylococcus aureus, exacerbate eosinophilic asthma [114]. Proteases such as Spls bind to the protease-activated receptor-2 on epithelial cells, which then secrete alarmins such as IL-33 and TSLP, which in turn activate ILC2 and induce a Th2 response [115]. According to the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), nasal colonization by S. aureus is associated with increased severity of asthma symptoms [116].

Members of the genus Pseudomonas are gram-negative bacteria known as opportunistic pathogens that cause respiratory diseases such as asthma, COPD, and bronchiectasis. Pseudomonas aeruginosa is the second most common bacteria in sputum cultures of patients with severe asthma [117]. According to Tuli et al., planktonic exo-proteins isolated from P. aeruginosa damage the mucosal barrier, thereby exacerbating asthma and chronic rhinosinusitis [118]. Flagellin isolated from P. aeruginosa was shown to increase secretion of the potent neutrophil chemoattractants IL-6 and IL-8 in human epithelial cells [119]. In a human study conducted by Green et al., asthma patients in which P. aeruginosa was the dominant pathogenic bacteria exhibited more severe neutrophilic inflammation and steroid resistance than patients in which other species were dominant [120].

In addition, nasopharyngeal colonization by members of the genera Streptococcus, Moraxella, and Haemophilus within the first year of life is associated with an increased risk of childhood asthma [121].

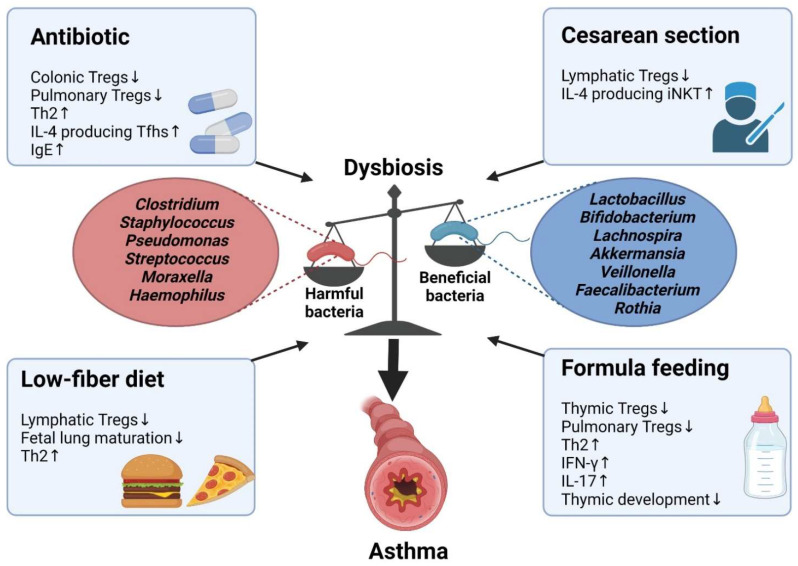

5. Dysbiosis-Induced Asthma

Dysbiosis is a disruption of the immune system caused by a dysregulation of microbiota homeostasis [122]. Several factors can initiate dysbiosis, including the use of antibiotics in the prenatal or neonatal periods, cesarean section, consumption of a low-fiber diet by the mother, or formula feeding [123]. Dysbiosis reportedly aggravates asthma by decreasing the number of Tregs and increasing the numbers of pathologic Th2 and Th17 cells [108,124]. In this section, we discuss how alterations in CD4+ T cells during dysbiosis affect the pathogenesis of asthma (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Development of dysbiosis-induced asthma. Beneficial bacteria suppress asthma, whereas harmful bacteria induce asthma. Dysbiosis can be caused by many factors, such as antibiotic use, cesarean section, low-fiber diet, and formula feeding. Dysbiosis influences the differentiation of T cells, resulting in asthma development. Tregs, regulatory T cells; Tfhs, T follicular helper cells; IgE, immunoglobulin E; iNKT, invariant natural killer T; IFN-γ, interferon gamma. The figure was created using BioRender.com (accessed on 6 September 2021).

5.1. Antibiotics

Several reports have indicated that antibiotic use can induce asthma [125,126,127]. The use of antibiotics before and after pregnancy reportedly increases the incidence of childhood asthma [128]. The functions of CD4+ T cells can be altered by antibiotic use, subsequently provoking the development of eosinophilic asthma. Murine studies demonstrated that antibiotic-induced dysbiosis exacerbates Th2-driven allergic inflammation by reducing numbers of Tregs in the colon [129] and lungs [129,130]. Hong et al. reported abnormal immune responses to undigested food in antibiotic-treated mice, resulting in increases in food antigen-driven IL-4–producing Tfhs and IgE production [131]. In a prospective cohort study, infants who received antibiotics between birth and 1 year of age had a 50% increased risk of childhood asthma [127].

5.2. Cesarean Section

Children delivered by cesarean section are reportedly at increased risk of asthma. According to Shao et al., delivery mode is the most influential factor in the formation of the neonatal gut microbiota [132]. Babies born via vaginal delivery obtain commensal bacteria from the mother’s vagina, whereas babies born via cesarean section receive commensal bacteria from the mother’s skin [133]. Kim et al. reported that infants born via cesarean section harbor fewer asthma-suppressing Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus, and Lachnospira and more asthma-promoting Pseudomonas in the gut [134]. In a murine study conducted by Zachariassen et al., mice born via cesarean section had fewer Tregs and increased numbers of IL-4–producing invariant natural killer T cells in mesenteric lymph nodes [135]. As a result, cesarean section–induced dysbiosis increases the risk of childhood asthma by 3-fold [136].

5.3. Low-Fiber Diet

A high-fiber diet protects against asthma. Fiber, a component of plants, is a complex carbohydrate structure composed of β-glycoside–linked glucose monomers [137]. Plant fibers are degraded into SCFAs, including acetate, via fermentation by gut bacteria [138]. Thorburn et al. reported that pregnant mother mice fed a high-fiber diet exhibited increased acetate production, which in turn increased the number of Tregs via HDAC9 inhibition; this led to alleviation of HDM-induced eosinophilic inflammation [139]. Fetal mice provided increased acetate via the placenta exhibited asthma-resistant lung maturation [139]. On the other hand, a low-fiber diet increased Th2 differentiation which led to eosinophilic airway inflammation [140]. Trompette et al. showed that reduction of SCFA by low-fiber diet affected hematopoiesis and increased Th2 cell response [140]. Using data from the 2007–2012 NHANES, Saeed et al. showed that low fiber intake is associated with a higher incidence of asthma as compared with high fiber intake [141].

5.4. Formula Feeding

Breast milk contains a variety of components that suppress the development of asthma in children. Mosconi et al. reported that allergen-specific IgG contained in breast milk binds to the Fc receptor of intestinal epithelial cells of the fetus, resulting in allergen-specific Treg induction and reduction of Th2 response [142]. Other breast milk components, including IL-7, cortisol, and microRNAs, aid in thymus development [143]. Ultrasound analyses comparing the size of the thymus of breastfed infants with that of formula-fed infants, the thymus size was reduced by >50% in 4-month-old formula-fed infants [144]. A murine study conducted by Nakajima et al. showed that SCFAs contained in breast milk bind to GPR41 in the fetal thymus and enhance Treg differentiation in both the thymus and peripheral organs [145]. Analyses of PBMCs from formula-fed and breastfed babies showed that formula feeding leads to a reduction in the number of Tregs, resulting in increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IFN-γ and IL-17 [146]. A cross-sectional study including 31,049 children reported that formula-fed children had a higher incidence of asthma than breastfed children [147].

6. Conclusions

Asthma is a heterogenous disease that can be largely classified as either eosinophilic asthma or neutrophilic asthma. CD4+ T cells play important roles in determining the asthma phenotype. Th2, Th9, and Tfh cells are involved in the development of eosinophilic asthma, whereas Th1 and Th17 cells are involved in the development of neutrophilic asthma. Proper classification of the asthma phenotype based on CD4+ T cells is essential to determine the optimal asthma treatment and accurately predict the prognosis.

Crosstalk between the microbiota and host immune system is another important factor in asthma development. Beneficial bacteria play a protective role in the pathogenesis of asthma, whereas harmful bacteria exacerbate asthma symptoms. Dysbiosis caused by an imbalance in the microbiota homeostasis alters the differentiation of CD4+ T cells, resulting in asthma aggravation. Dysbiosis can be corrected using various probiotic products that were developed to improve asthma symptoms [148,149]. However, these probiotics still play an adjuvant role in the treatment of asthma. To evaluate the microbiota as a potential therapeutic target in greater detail, a precise mechanistic study will be necessary to fully elucidate the effects of the microbiota and CD4+ T cells on the pathogenesis of asthma.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the members of the Laboratory of Host Defenses for their helpful advice and discussions.

Author Contributions

Writing and original draft preparation, J.J. and H.K.L.; writing, reviewing, and editing, J.J. and H.K.L.; supervision, H.K.L.; funding acquisition, J.J. and H.K.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2019R1A2C2087490, NRF-2021M3A9D3026428 and NRF-2021M3A9H3015688) and funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT of Korea (Sejong-si, Korea). J. Jeong is the recipient of a Global PhD Fellowship (NRF-2019H1A2A1076865) awarded by the National Research Foundation of Korea (Daejeon, Korea).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hammad H., Lambrecht B.N. The basic immunology of asthma. Cell. 2021;184:1469–1485. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Enilari O., Sinha S. The Global Impact of Asthma in Adult Populations. Ann. Glob. Health. 2019;85:1–7. doi: 10.5334/aogh.2412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.2021 GINA Main Report Global Initiative for Asthma–GINA. [(accessed on 12 August 2021)]. Available online: https://ginasthma.org/gina-reports/

- 4.Mina Gaga E.Z. Oral steroids in asthma: A double-edged sword. Eur. Respir. J. 2019;54:1902034. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02034-2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Papi A., Brightling C., Pedersen S.E., Reddel H.K. Asthma. Lancet. 2018;391:783–800. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33311-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doroudchi A., Pathria M., Modena B.D. Asthma biologics: Comparing trial designs, patient cohorts and study results. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2020;124:44–56. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2019.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sze E., Bhalla A., Nair P. Mechanisms and therapeutic strategies for non-T2 asthma. Allergy Eur. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2020;75:311–325. doi: 10.1111/all.13985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muehling L.M., Lawrence M.G., Woodfolk J.A. Pathogenic CD4+ T cells in patients with asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2017;140:1523–1540. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang Y.J., Nariya S., Harris J.M., Lynch S.V., Choy D.F., Arron J.R., Boushey H. The airway microbiome in patients with severe asthma: Associations with disease features and severity. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015;136:874–884. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.05.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simpson J.L., Daly J., Baines K.J., Yang I.A., Upham J.W., Reynolds P.N., Hodge S., James A.L., Hugenholtz P., Willner D., et al. Airway dysbiosis: Haemophilus influenzae and Tropheryma in poorly controlled asthma. Eur. Respir. J. 2016;47:792–800. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00405-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Durack J., Lynch S.V., Nariya S., Bhakta N.R., Beigelman A., Castro M., Dyer A.-M., Israel E., Kraft M., Martin R.J., et al. Features of the bronchial bacterial microbiome associated with atopy, asthma, and responsiveness to inhaled corticosteroid treatment. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2017;140:63–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.08.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peterson J., Garges S., Giovanni M., McInnes P., Wang L., Schloss J.A., Bonazzi V., McEwen J.E., Wetterstrand K.A., Deal C., et al. The NIH Human Microbiome Project. Genome Res. 2009;19:2317–2323. doi: 10.1101/GR.096651.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sender R., Fuchs S., Milo R. Revised Estimates for the Number of Human and Bacteria Cells in the Body. PLoS Biol. 2016;14:e1002533. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramakrishna B.S. Role of the gut microbiota in human nutrition and metabolism. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013;28:9–17. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Durack J., Lynch S.V. The gut microbiome: Relationships with disease and opportunities for therapy. J. Exp. Med. 2019;216:20–40. doi: 10.1084/jem.20180448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang Y.J., Marsland B.J., Bunyavanich S., O’Mahony L., Leung D.Y.M., Muraro A., Fleisher T.A. The microbiome in allergic disease: Current understanding and future opportunities—2017 PRACTALL document of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology and the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2017;139:1099–1110. doi: 10.1016/J.JACI.2017.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuruvilla M.E., Lee F.E.-H., Lee G.B. Understanding Asthma Phenotypes, Endotypes, and Mechanisms of Disease. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2018;56:219–233. doi: 10.1007/s12016-018-8712-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brusselle G.G., Maes T., Bracke K.R. Eosinophils in the Spotlight: Eosinophilic airway inflammation in nonallergic asthma. Nat. Med. 2013;19:977–979. doi: 10.1038/nm.3300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dong C. Cytokine Regulation and Function in T Cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2021;39:51–76. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-061020-053702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knochelmann H.M., Dwyer C.J., Bailey S.R., Amaya S.M., Elston D.M., Mazza-McCrann J.M., Paulos C.M. When worlds collide: Th17 and Treg cells in cancer and autoimmunity. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2018;15:458–469. doi: 10.1038/s41423-018-0004-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saeki M., Nishimura T., Kitamura N., Hiroi T., Mori A., Kaminuma O. Potential Mechanisms of T Cell-Mediated and Eosinophil-Independent Bronchial Hyperresponsiveness. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:2980. doi: 10.3390/ijms20122980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seumois G., Zapardiel-Gonzalo J., White B., Singh D., Schulten V., Dillon M., Hinz D., Broide D.H., Sette A., Peters B., et al. Transcriptional Profiling of Th2 Cells Identifies Pathogenic Features Associated with Asthma. J. Immunol. 2016;197:655–664. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1600397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Junttila I.S. Tuning the Cytokine Responses: An Update on Interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-13 Receptor Complexes. Front. Immunol. 2018;9:888. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lambrecht B.N., Hammad H., Fahy J.V. The Cytokines of Asthma. Immunity. 2019;50:975–991. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pelaia C., Paoletti G., Puggioni F., Racca F., Pelaia G., Canonica G.W., Heffler E. Interleukin-5 in the Pathophysiology of Severe Asthma. Front. Physiol. 2019;10:1514. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.01514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Foster P.S., Hogan S.P., Ramsay A.J., Matthaei K.I., Young I.G. Interleukin 5 deficiency abolishes eosinophilia, airways hyperreactivity, and lung damage in a mouse asthma model. J. Exp. Med. 1996;183:195–201. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.1.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnston L.K., Hsu C.-L., Krier-Burris R.A., Chhiba K.D., Chien K.B., McKenzie A., Berdnikovs S., Bryce P.J. IL-33 Precedes IL-5 in Regulating Eosinophil Commitment and Is Required for Eosinophil Homeostasis. J. Immunol. 2016;197:3445–3453. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1600611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johansson M.W. Eosinophil Activation Status in Separate Compartments and Association with Asthma. Front. Med. 2017;4:75. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2017.00075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seibold M.A. Interleukin-13 Stimulation Reveals the Cellular and Functional Plasticity of the Airway Epithelium. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2018;15:S98–S106. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201711-868MG. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li J., Ye Z. The Potential Role and Regulatory Mechanisms of MUC5AC in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Molecules. 2020;25:4437. doi: 10.3390/molecules25194437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marone G., Granata F., Pucino V., Pecoraro A., Heffler E., Loffredo S., Scadding G.W., Varricchi G. The Intriguing Role of Interleukin 13 in the Pathophysiology of Asthma. Front. Pharmacol. 2019;10:1387. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.01387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bel E.H., Wenzel S.E., Thompson P.J., Prazma C.M., Keene O.N., Yancey S.W., Ortega H.G., Pavord I.D. Oral Glucocorticoid-Sparing Effect of Mepolizumab in Eosinophilic Asthma. N. Eng. J. Med. 2014;371:1189–1197. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1403291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ortega H.G., Liu M.C., Pavord I.D., Brusselle G.G., FitzGerald J.M., Chetta A., Humbert M., Katz L.E., Keene O.N., Yancey S.W., et al. Mepolizumab Treatment in Patients with Severe Eosinophilic Asthma. N. Eng. J. Med. 2014;371:1198–1207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1403290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Castro M., Zangrilli J., Wechsler M.E., Bateman E.D., Brusselle G.G., Bardin P., Murphy K., Maspero J.F., O’Brien C., Korn S. Reslizumab for inadequately controlled asthma with elevated blood eosinophil counts: Results from two multicentre, parallel, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trials. Lancet Respir. Med. 2015;3:355–366. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00042-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nair P., Wenzel S., Rabe K.F., Bourdin A., Lugogo N.L., Kuna P., Barker P., Sproule S., Ponnarambil S., Goldman M. Oral Glucocorticoid–Sparing Effect of Benralizumab in Severe Asthma. N. Eng. J. Med. 2017;376:2448–2458. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1703501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Castro M., Corren J., Pavord I.D., Maspero J., Wenzel S., Rabe K.F., Busse W.W., Ford L., Sher L., FitzGerald J.M., et al. Dupilumab Efficacy and Safety in Moderate-to-Severe Uncontrolled Asthma. N. Eng. J. Med. 2018;378:2486–2496. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1804092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Garn H., Renz H. GATA-3-specific DNAzyme A novel approach for stratified asthma therapy. Eur. J. Immunol. 2017;47:22–30. doi: 10.1002/eji.201646450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krug N., Hohlfeld J.M., Kirsten A.-M., Kornmann O., Beeh K.M., Kappeler D., Korn S., Ignatenko S., Timmer W., Rogon C., et al. Allergen-Induced Asthmatic Responses Modified by a GATA3-Specific DNAzyme. N. Eng. J. Med. 2015;372:1987–1995. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1411776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Badolati I., Sverremark-Ekström E., Heiden M. van der Th9 cells in allergic diseases: A role for the microbiota? Scand. J. Immunol. 2020;91:e12857. doi: 10.1111/sji.12857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Neurath M.F., Kaplan M.H. Th9 cells in immunity and immunopathological diseases. Semin. Immunopathol. 2017;39:1–4. doi: 10.1007/s00281-016-0611-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Angkasekwinai P., Dong C. IL-9-producing T cells: Potential players in allergy and cancer. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2021;21:37–48. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0396-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Koch S., Sopel N., Finotto S. Th9 and other IL-9-producing cells in allergic asthma. Semin. Immunopathol. 2016;39:55–68. doi: 10.1007/s00281-016-0601-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Petit-Frere C., Dugas B., Braquet P., Mencia-Huerta J.M. Interleukin-9 potentiates the interleukin-4-induced IgE and IgG1 release from murine B lymphocytes. Immunology. 1993;79:146. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McLane M.P., Haczku A., van de Rijn M., Weiss C., Ferrante V., MacDonald D., Renauld J.-C., Nicolaides N.C., Holroyd K.J., Levitt R.C. Interleukin-9 promotes allergen-induced eosinophilic inflammation and airway hyperresponsiveness in transgenic mice. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 1998;19:713–720. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.19.5.3457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jones C.P., Gregory L.G., Causton B., Campbell G.A., Lloyd C.M. Activin A and TGF-β promote TH9 cell–mediated pulmonary allergic pathology. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2012;129:1000–1010.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.12.965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Temann U.A., Ray P., Flavell R.A. Pulmonary overexpression of IL-9 induces Th2 cytokine expression, leading to immune pathology. J. Clin. Investig. 2002;109:29–39. doi: 10.1172/JCI0213696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Louahed J., Zhou Y., Maloy W.L., Rani P.U., Weiss C., Tomer Y., Vink A., Renauld J., Snick van J., Nicolaides N.C., et al. Interleukin 9 promotes influx and local maturation of eosinophils. Blood. 2001;97:1035–1042. doi: 10.1182/blood.V97.4.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vermeer P.D., Harson R., Einwalter L.A., Moninger T., Zabner J. Interleukin-9 induces goblet cell hyperplasia during repair of human airway epithelia. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2003;28:286–295. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.4887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chang H.-C., Sehra S., Goswami R., Yao W., Yu Q., Stritesky G.L., Jabeen R., McKinley C., Ahyi A.-N., Han L., et al. The transcription factor PU.1 is required for the development of IL-9-producing T cells and allergic inflammation. Nat. Immunol. 2010;11:527–534. doi: 10.1038/ni.1867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McLeod J.J.A., Baker B., Ryan J.J. Mast cell production and response to IL-4 and IL-13. Cytokine. 2015;75:57–61. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2015.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sehra S., Yao W., Nguyen E.T., Glosson-Byers N.L., Akhtar N., Zhou B., Kaplan M.H. TH9 cells are required for tissue mast cell accumulation during allergic inflammation. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015;136:433–440.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cheng G., Arima M., Honda K., Hirata H., Eda F., Yoshida N., Fukushima F., Ishii Y., Fukuda T. Anti-interleukin-9 antibody treatment inhibits airway inflammation and hyperreactivity in mouse asthma model. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2002;166:409–416. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2105079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim M.S., Cho K.-A., Cho Y.J., Woo S.-Y. Effects of interleukin-9 blockade on chronic airway inflammation in murine asthma models. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Res. 2013;5:197–206. doi: 10.4168/aair.2013.5.4.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Oh C.K., Leigh R., McLaurin K.K., Kim K., Hultquist M., Molfino N.A. A randomized, controlled trial to evaluate the effect of an anti-interleukin-9 monoclonal antibody in adults with uncontrolled asthma. Respir. Res. 2013;14:1–11. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-14-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lloyd C.M., Harker J.A. Epigenetic Control of Interleukin-9 in Asthma. N. Eng. J. Med. 2018;379:87–89. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcibr1803610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xiao X., Fan Y., Li J., Zhang X., Lou X., Dou Y., Shi X., Lan P., Xiao Y., Minze L., et al. Guidance of super-enhancers in regulation of IL-9 induction and airway inflammation. J. Exp. Med. 2018;215:559–574. doi: 10.1084/jem.20170928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sanders Y.Y., Thannickal V.J. BETting on Novel Treatments for Asthma: Bromodomain 4 Inhibitors. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2019;60:7. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2018-0271ED. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gong F., Zheng T., Zhou P. T Follicular Helper Cell Subsets and the Associated Cytokine IL-21 in the Pathogenesis and Therapy of Asthma. Front. Immunol. 2019;10:2918. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Crotty S. T Follicular Helper Cell Biology: A Decade of Discovery and Diseases. Immunity. 2019;50:1132–1148. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vinuesa C.G., Linterman M.A., Yu D., MacLennan I.C.M. Follicular Helper T Cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2016;34:335–368. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-041015-055605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Corry D.B., Kheradmand F. Induction and regulation of the IgE response. Nature. 1999;402:18–23. doi: 10.1038/35037014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kobayashi T., Iijima K., Dent A.L., Kita H. Follicular helper T cells mediate IgE antibody response to airborne allergens. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2017;139:300–313.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Noble A., Zhao J. Follicular helper T cells are responsible for IgE responses to Der p 1 following house dust mite sensitization in mice. Clin. Exp. Allergy. 2016;46:1075–1082. doi: 10.1111/cea.12750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yao Y., Chen C.L., Wang N., Wang Z.C., Ma J., Zhu R.F., Xu X.Y., Zhou P.C., Yu D., Liu Z. Correlation of allergen-specific T follicular helper cell counts with specific IgE levels and efficacy of allergen immunotherapy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2018;142:321–324.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Coquet J.M., Schuijs M.J., Smyth M.J., Deswarte K., Beyaert R., Braun H., Boon L., Hedestam G.B.K., Nutt S.L., Hammad H., et al. Interleukin-21-Producing CD4+ T Cells Promote Type 2 Immunity to House Dust Mites. Immunity. 2015;43:318–330. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ballesteros-Tato A., Randall T.D., Lund F.E., Spolski R., Leonard W.J., León B. T Follicular Helper Cell Plasticity Shapes Pathogenic T Helper 2 Cell-Mediated Immunity to Inhaled House Dust Mite. Immunity. 2016;44:259–273. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Uwadiae F.I., Pyle C.J., Walker S.A., Lloyd C.M., Harker J.A. Targeting the ICOS/ICOS-L pathway in a mouse model of established allergic asthma disrupts T follicular helper cell responses and ameliorates disease. Allergy. 2019;74:650–662. doi: 10.1111/all.13602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang D., Wu Y., Sun G. miR-192 suppresses T follicular helper cell differentiation by targeting CXCR5 in childhood asthma. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Investig. 2018;78:236–242. doi: 10.1080/00365513.2018.1440628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Thomson N.C. Novel approaches to the management of noneosinophilic asthma. Ther. Adv. Respir. Dis. Rev. 2016;10:211–234. doi: 10.1177/1753465816632638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wener R.R.L., Bel E.H. Severe refractory asthma: An update. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2013;22:227–235. doi: 10.1183/09059180.00001913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Laan M., Cui Z.H., Hoshino H., Lötvall J., Sjöstrand M., Gruenert D.C., Skoogh B.E., Lindén A. Neutrophil recruitment by human IL-17 via C-X-C chemokine release in the airways. J. Immunol. 1999;162:2347–2352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pène J., Chevalier S., Preisser L., Vénéreau E., Guilleux M.-H., Ghannam S., Molès J.-P., Danger Y., Ravon E., Lesaux S., et al. Chronically Inflamed Human Tissues Are Infiltrated by Highly Differentiated Th17 Lymphocytes. J. Immunol. 2008;180:7423–7430. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.11.7423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bellini A., Marini M.A., Bianchetti L., Barczyk M., Schmidt M., Mattoli S. Interleukin (IL)-4, IL-13, and IL-17A differentially affect the profibrotic and proinflammatory functions of fibrocytes from asthmatic patients. Mucosal Immunol. 2011;5:140–149. doi: 10.1038/mi.2011.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Newcomb D.C., Boswell M.G., Reiss S., Zhou W., Goleniewska K., Toki S., Harintho M.T., Lukacs N.W., Kolls J.K., Peebles R.S. IL-17A inhibits airway reactivity induced by respiratory syncytial virus infection during allergic airway inflammation. Thorax. 2013;68:717–723. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-202404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Camargo L.D.N., Righetti R.F., Aristóteles L.R.D.C.R.B., Dos Santos T.M., de Souza F.C.R., Fukuzaki S., Cruz M.M., Alonso-Vale M.I.C., Saraiva-Romanholo B.M., Prado C.M., et al. Effects of Anti-IL-17 on Inflammation, Remodeling, and Oxidative Stress in an Experimental Model of Asthma Exacerbated by LPS. Front. Immunol. 2018;8:1835. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chang Y., Al-Alwan L., Risse P.A., Roussel L., Rousseau S., Halayko A.J., Martin J.G., Hamid Q., Eidelman D.H. TH17 cytokines induce human airway smooth muscle cell migration. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2011;127:1046–1053.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.12.1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kudo M., Melton A.C., Chen C., Engler M.B., Huang K.E., Ren X., Wang Y., Bernstein X., Li J.T., Atabai K., et al. IL-17A produced by αβ T cells drives airway hyper-responsiveness in mice and enhances mouse and human airway smooth muscle contraction. Nat. Med. 2012;18:547–554. doi: 10.1038/nm.2684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chang Y., Al-Alwan L., Risse P.-A., Halayko A.J., Martin J.G., Baglole C.J., Eidelman D.H., Hamid Q. Th17-associated cytokines promote human airway smooth muscle cell proliferation. FASEB J. 2012;26:5152–5160. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-208033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ramakrishnan R.K., Bajbouj K., Al Heialy S., Mahboub B., Ansari A.W., Hachim I.Y., Rawat S., Salameh L., Hachim M.Y., Olivenstein R., et al. IL-17 Induced Autophagy Regulates Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Fibrosis in Severe Asthmatic Bronchial Fibroblasts. Front. Immunol. 2020;11:1002. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chiba Y., Tanoue G., Suto R., Suto W., Hanazaki M., Katayama H., Sakai H. Interleukin-17A directly acts on bronchial smooth muscle cells and augments the contractility. Pharmacol. Rep. 2016;69:377–385. doi: 10.1016/j.pharep.2016.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Willis C.R., Siegel L., Leith A., Mohn D., Escobar S., Wannberg S., Misura K., Rickel E., Rottman J.B., Comeau M.R., et al. IL-17RA signaling in airway inflammation and bronchial hyperreactivity in allergic asthma. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2015;53:810–821. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2015-0038OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nanzer A.M., Chambers E.S., Ryanna K., Richards D.F., Black C., Timms P.M., Martineau A.R., Griffiths C.J., Corrigan C.J., Hawrylowicz C.M. Enhanced production of IL-17A in patients with severe asthma is inhibited by 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in a glucocorticoid-independent fashion. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2013;132:3037. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chambers E.S., Nanzer A.M., Pfeffer P.E., Richards D.F., Timms P.M., Martineau A.R., Griffiths C.J., Corrigan C.J., Hawrylowicz C.M. Distinct endotypes of steroid-resistant asthma characterized by IL-17Ahigh and IFN-γhigh immunophenotypes: Potential benefits of calcitriol. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015;136:628–637.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Safety, Tolerability, and Efficacy of AIN457 in Patients with Uncontrolled Asthma–Study Results–ClinicalTrials.gov. [(accessed on 12 August 2021)]; Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/results/NCT01478360?cond=AIN457&draw=2#part.

- 85.Amarnani A., Rosenthal K.S., Mercado J.M., Brodell R.T. Concurrent treatment of chronic psoriasis and asthma with ustekinumab. J. Dermatol. Treatm. 2013;25:63–66. doi: 10.3109/09546634.2013.782095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Webb L.M., Oyesola O.O., Früh S.P., Kamynina E., Still K.M., Patel R.K., Peng S.A., Cubitt R.L., Grimson A., Grenier J.K., et al. The Notch signaling pathway promotes basophil responses during helminth-induced type 2 inflammation. J. Exp. Med. 2019;216:1268–1279. doi: 10.1084/jem.20180131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Garn H., Potaczek D.P., Pfefferle P.I. The Hygiene Hypothesis and New Perspectives—Current Challenges Meeting an Old Postulate. Front. Immunol. 2021;12:847. doi: 10.3389/FIMMU.2021.637087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Cui J., Pazdziorko S., Miyashiro J.S., Thakker P., Pelker J.W., Declercq C., Jiao A., Gunn J., Mason L., Leonard J.P., et al. TH1-mediated airway hyperresponsiveness independent of neutrophilic inflammation. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2005;115:309–315. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.10.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Raundhal M., Morse C., Khare A., Oriss T.B., Milosevic J., Trudeau J., Huff R., Pilewski J., Holguin F., Kolls J., et al. High IFN-γ and low SLPI mark severe asthma in mice and humans. J. Clin. Investig. 2015;125:3037–3050. doi: 10.1172/JCI80911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kim Y.-K., Oh S.-Y., Jeon S.G., Park H.-W., Lee S.-Y., Chun E.-Y., Bang B., Lee H.-S., Oh M.-H., Kim Y.-S., et al. Airway Exposure Levels of Lipopolysaccharide Determine Type 1 versus Type 2 Experimental Asthma. J. Immunol. 2007;178:5375–5382. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.8.5375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wang Z., Zheng T., Zhu Z., Homer R.J., Riese R.J., Chapman H.A., Shapiro S.D., Elias J.A. Interferon γ induction of pulmonary emphysema in the adult murine lung. J. Exp. Med. 2000;192:1587–1599. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.11.1587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Loverdos K., Bellos G., Kokolatou L., Vasileiadis I., Giamarellos E., Pecchiari M., Koulouris N., Koutsoukou A., Rovina N. Lung Microbiome in Asthma: Current Perspectives. J. Clin. Med. 2019;8:1967. doi: 10.3390/jcm8111967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Frati F., Salvatori C., Incorvaia C., Bellucci A., Di Cara G., Marcucci F., Esposito S. The Role of the Microbiome in Asthma: The Gut–Lung Axis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:123. doi: 10.3390/ijms20010123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Patra J.K., Das G., Paramithiotis S., Shin H.-S. Kimchi and Other Widely Consumed Traditional Fermented Foods of Korea: A Review. Front. Microbiol. 2016;7:1493. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Redondo-Useros N., Gheorghe A., Díaz-Prieto L.E., Villavisencio B., Marcos A., Nova E. Associations of Probiotic Fermented Milk (PFM) and Yogurt Consumption with Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus Components of the Gut Microbiota in Healthy Adults. Nutrients. 2019;11:651. doi: 10.3390/nu11030651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Spacova I., Petrova M.I., Fremau A., Pollaris L., Vanoirbeek J., Ceuppens J.L., Seys S., Lebeer S. Intranasal administration of probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG prevents birch pollen-induced allergic asthma in a murine model. Allergy. 2019;74:100–110. doi: 10.1111/all.13502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Li L., Fang Z., Liu X., Hu W., Lu W., Lee Y., Zhao J., Zhang H., Chen W. Lactobacillus reuteri attenuated allergic inflammation induced by HDM in the mouse and modulated gut microbes. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0231865. doi: 10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0231865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Chen Y.-S., Jan R.-L., Lin Y.-L., Chen H.-H., Wang J.-Y. Randomized placebo-controlled trial of lactobacillus on asthmatic children with allergic rhinitis. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2010;45:1111–1120. doi: 10.1002/ppul.21296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Raftis E.J., Delday M.I., Cowie P., McCluskey S.M., Singh M.D., Ettorre A., Mulder I.E. Bifidobacterium breve MRx0004 protects against airway inflammation in a severe asthma model by suppressing both neutrophil and eosinophil lung infiltration. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:1–13. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-30448-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Sun S., Luo L., Liang W., Yin Q., Guo J., Rush A.M., Lv Z., Liang Q., Fischbach M.A., Sonnenburg J.L., et al. Bifidobacterium alters the gut microbiota and modulates the functional metabolism of T regulatory cells in the context of immune checkpoint blockade. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2020;117:27509–27515. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1921223117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Del Giudice M.M., Indolfi C., Capasso M., Maiello N., Decimo F., Ciprandi G. Bifidobacterium mixture (B longum BB536, B infantis M-63, B breve M-16V) treatment in children with seasonal allergic rhinitis and intermittent asthma. Ital. J. Pediatrics. 2017;43:3405. doi: 10.1186/S13052-017-0340-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Vacca M., Celano G., Calabrese F.M., Portincasa P., Gobbetti M., Angelis M. De The Controversial Role of Human Gut Lachnospiraceae. Microorganisms. 2020;8:573. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8040573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Maslowski K.M., Vieira A.T., Ng A., Kranich J., Sierro F., Yu D., Schilter H.C., Rolph M.S., Mackay F., Artis D., et al. Regulation of inflammatory responses by gut microbiota and chemoattractant receptor GPR43. Nature. 2009;461:1282–1286. doi: 10.1038/nature08530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Arpaia N., Campbell C., Fan X., Dikiy S., Van Der Veeken J., Deroos P., Liu H., Cross J.R., Pfeffer K., Coffer P.J., et al. Metabolites produced by commensal bacteria promote peripheral regulatory T-cell generation. Nature. 2013;504:451–455. doi: 10.1038/nature12726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Arrieta M.-C., Stiemsma L.T., Dimitriu P.A., Thorson L., Russell S., Yurist-Doutsch S., Kuzeljevic B., Gold M.J., Britton H.M., Lefebvre D.L., et al. Early infancy microbial and metabolic alterations affect risk of childhood asthma. Sci. Transl. Med. 2015;7:307ra152. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aab2271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Michalovich D., Rodriguez-Perez N., Smolinska S., Pirozynski M., Mayhew D., Uddin S., Van Horn S., Sokolowska M., Altunbulakli C., Eljaszewicz A., et al. Obesity and disease severity magnify disturbed microbiome-immune interactions in asthma patients. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:1–14. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13751-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kuczma M.P., Szurek E.A., Cebula A., Ngo V.L., Pietrzak M., Kraj P., Denning T.L., Ignatowicz L. Self and microbiota-derived epitopes induce CD4+ T cell anergy and conversion into CD4+Foxp3+ regulatory cells. Mucosal Immunol. 2020;14:443–454. doi: 10.1038/s41385-020-00349-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Demirci M., Tokman H.B., Uysal H.K., Demiryas S., Karakullukcu A., Saribas S., Cokugras H., Kocazeybek B.S. Reduced Akkermansia muciniphila and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii levels in the gut microbiota of children with allergic asthma. Allergol. Et. Immunopathol. 2019;47:365–371. doi: 10.1016/j.aller.2018.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Falcone M., Tiseo G., Menichetti F. Community-acquired Pneumonia Owing to Multidrug-Resistant Pathogens: A Step toward an Early Identification. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2021;18:211. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202009-1207ED. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Lee H.S., Plechot K., Gohil S., Le J. Clostridium difficile: Diagnosis and the Consequence of Over Diagnosis. Infect. Dis. Ther. 2021;10:687–697. doi: 10.1007/s40121-021-00417-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Van Nimwegen F.A., Penders J., Stobberingh E.E., Postma D.S., Koppelman G.H., Kerkhof M., Reijmerink N.E., Dompeling E., Van Den Brandt P.A., Ferreira I., et al. Mode and place of delivery, gastrointestinal microbiota, and their influence on asthma and atopy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2011;128:948–955. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Stiemsma L.T., Arrieta M.-C., Dimitriu P.A., Cheng J., Thorson L., Lefebvre D.L., Azad M.B., Subbarao P., Mandhane P., Becker A., et al. Shifts in Lachnospira and Clostridium sp. in the 3-month stool microbiome are associated with preschool age asthma. Clin. Sci. 2016;130:2199–2207. doi: 10.1042/CS20160349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Chiu C.Y., Chan Y.L., Tsai M.H., Wang C.J., Chiang M.H., Chiu C.C. Gut microbial dysbiosis is associated with allergen-specific IgE responses in young children with airway allergies. World Allergy Organ. J. 2019;12:100021. doi: 10.1016/j.waojou.2019.100021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Stentzel S., Teufelberger A., Nordengrün M., Kolata J., Schmidt F., van Crombruggen K., Michalik S., Kumpfmüller J., Tischer S., Schweder T., et al. Staphylococcal serine protease like proteins are pacemakers of allergic airway reactions to Staphylococcus aureus. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2017;139:492–500.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Krysko O., Teufelberger A., Nevel S.V., Krysko D.V., Bachert C. Protease/antiprotease network in allergy: The role of Staphylococcus aureus protease-like proteins. Allergy. 2019;74:2077–2086. doi: 10.1111/all.13783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Davis M.F., Peng R.D., McCormack M.C., Matsui E.C. Staphylococcus aureus colonization is associated with wheeze and asthma among US children and young adults. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015;135:811–813.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.10.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Zhang Q., Illing R., Hui C.K., Downey K., Carr D., Stearn M., Alshafi K., Menzies-Gow A., Zhong N., Fan Chung K. Bacteria in sputum of stable severe asthma and increased airway wall thickness. Respir. Res. 2012;13:1–8. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-13-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Tuli J.F., Ramezanpour M., Cooksley C., Psaltis A.J., Wormald P.-J., Vreugde S. Association between mucosal barrier disruption by Pseudomonas aeruginosa exoproteins and asthma in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis. Allergy. 2021;76:1–11. doi: 10.1111/all.14959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Nakamoto K., Watanabe M., Sada M., Inui T., Nakamura M., Honda K., Ishii H., Takizawa H. IL-6 and IL-8 production induced by Pseudomonas aeruginosa flagellin in human bronchial epithelial cells. Eur. Respir. J. 2017;50:PA989. doi: 10.1183/1393003.CONGRESS-2017.PA989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Green B.J., Wiriyachaiporn S., Grainge C., Rogers G.B., Kehagia V., Lau L., Carroll M.P., Bruce K.D., Howarth P.H. Potentially Pathogenic Airway Bacteria and Neutrophilic Inflammation in Treatment Resistant Severe Asthma. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e100645. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Teo S.M., Mok D., Pham K., Kusel M., Serralha M., Troy N., Holt B.J., Hales B.J., Walker M.L., Hollams E., et al. The Infant Nasopharyngeal Microbiome Impacts Severity of Lower Respiratory Infection and Risk of Asthma Development. Cell Host Microbe. 2015;17:704–715. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Tiffany C.R., Bäumler A.J. Dysbiosis: From fiction to function. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2019;317:G602–G608. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00230.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Hufnagl K., Pali-Schöll I., Roth-Walter F., Jensen-Jarolim E. Dysbiosis of the gut and lung microbiome has a role in asthma. Semin. Immunopathol. 2020;42:75–93. doi: 10.1007/s00281-019-00775-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Atarashi K., Tanoue T., Shima T., Imaoka A., Kuwahara T., Momose Y., Cheng G., Yamasaki S., Saito T., Ohba Y., et al. Induction of colonic regulatory T cells by indigenous Clostridium species. Science. 2011;331:337–341. doi: 10.1126/science.1198469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Örtqvist A.K., Lundholm C., Kieler H., Ludvigsson J.F., Fall T., Ye W., Almqvist C. Antibiotics in fetal and early life and subsequent childhood asthma: Nationwide population based study with sibling analysis. BMJ. 2014;349:g6979. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g6979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Ni J., Friedman H., Boyd B.C., McGurn A., Babinski P., Markossian T., Dugas L.R. Early antibiotic exposure and development of asthma and allergic rhinitis in childhood. BMC Pediatrics. 2019;19:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12887-019-1594-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Patrick D.M., Sbihi H., Dai D.L.Y., Al Mamun A., Rasali D., Rose C., Marra F., Boutin R.C.T., Petersen C., Stiemsma L.T., et al. Decreasing antibiotic use, the gut microbiota, and asthma incidence in children: Evidence from population-based and prospective cohort studies. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020;8:1094–1105. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30052-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Zhang M., Litonjua A.A., Mueller N.T. Maternal antibiotic use and child asthma: Is the association causal? Eur. Respir. J. 2018;52:1801007. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01007-2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Russell S.L., Gold M.J., Hartmann M., Willing B.P., Thorson L., Wlodarska M., Gill N., Blanchet M.R., Mohn W.W., McNagny K.M., et al. Early life antibiotic-driven changes in microbiota enhance susceptibility to allergic asthma. EMBO Rep. 2012;13:440–447. doi: 10.1038/embor.2012.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Adami A.J., Bracken S.J., Guernsey L.A., Rafti E., Maas K.R., Graf J., Matson A.P., Thrall R.S., Schramm C.M. Early-life antibiotics attenuate regulatory T cell generation and increase the severity of murine house dust mite-induced asthma. Pediatric. Res. 2018;84:426–434. doi: 10.1038/s41390-018-0031-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Hong S.W., Eunju O., Lee J.Y., Lee M., Han D., Ko H.J., Sprent J., Surh C.D., Kim K.S. Food antigens drive spontaneous IgE elevation in the absence of commensal microbiota. Sci. Adv. 2019;5:eaaw1507. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaw1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Shao Y., Forster S.C., Tsaliki E., Vervier K., Strang A., Simpson N., Kumar N., Stares M.D., Rodger A., Brocklehurst P., et al. Stunted microbiota and opportunistic pathogen colonization in caesarean-section birth. Nature. 2019;574:117–121. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1560-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Park Y.J., Lee H.K. The role of skin and orogenital microbiota in protective immunity and chronic immune-mediated inflammatory disease. Front. Immunol. 2018;8:1–13. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Kim G., Bae J., Kim M.J., Kwon H., Park G., Kim S.J., Choe Y.H., Kim J., Park S.H., Choe B.H., et al. Delayed Establishment of Gut Microbiota in Infants Delivered by Cesarean Section. Front. Microbiol. 2020;11:2099. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.02099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Zachariassen L.F., Krych L., Rasmussen S.H., Nielsen D.S., Kot W., Holm T.L., Hansen A.K., Hansen C.H.F. Cesarean Section Induces Microbiota-Regulated Immune Disturbances in C57BL/6 Mice. J. Immunol. 2019;202:142–150. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1800666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Stokholm J., Thorsen J., Blaser M.J., Rasmussen M.A., Hjelmsø M., Shah S., Christensen E.D., Chawes B.L., Bønnelykke K., Brix S., et al. Delivery mode and gut microbial changes correlate with an increased risk of childhood asthma. Sci. Transl. Med. 2020;12 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aax9929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Yuan H., Lan P., He Y., Li C., Ma X. Effect of the Modifications on the Physicochemical and Biological Properties of β-Glucan—A Critical Review. Molecules. 2020;25:57. doi: 10.3390/molecules25010057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Lynch J.P., Sikder M.A.A., Curren B.F., Werder R.B., Simpson J., Cuív P., Dennis P.G., Everard M.L., Phipps S. The influence of the microbiome on early-life severe viral lower respiratory infections and asthma-Food for thought? Front. Immunol. 2017;8:1–15. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Thorburn A.N., McKenzie C.I., Shen S., Stanley D., MacIa L., Mason L.J., Roberts L.K., Wong C.H.Y., Shim R., Robert R., et al. Evidence that asthma is a developmental origin disease influenced by maternal diet and bacterial metabolites. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:7320. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]