Abstract

The major capsid protein VP2 of human parvovirus B19, when studied in a denatured form exhibiting linear epitopes, is recognized exclusively by immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies of patients with acute or recent B19 infection. By contrast, conformational epitopes of VP2 are recognized both by IgG of the acute phase and by IgG of past immunity. In order to localize the VP2 linear epitope(s) specific for acute-phase IgG, the entire B19 capsid protein sequence was mapped by peptide scanning using well-characterized acute-phase and control sera. A unique heptapeptide epitope showing strong and selective reactivity with the acute-phase IgG was detected and characterized. By using this linear epitope (VP2 amino acids 344 to 350) and virus-like particles exhibiting conformational VP2 epitopes, an innovative approach, second-generation epitope-typing enzyme immunoassay, was set up for improved diagnosis of primary infections by human parvovirus B19.

Human parvovirus B19 is a small nonenveloped DNA virus, the icosahedral capsid of which consists of structural proteins of two types, the minor protein VP1 (83 kDa) and the major protein VP2 (58 kDa). VP2 is contained within VP1, which has an additional unique portion of 227 amino acids (aa). Of the 60 capsid protein molecules in the native virus, VP2 makes up more than 90% (9).

Infection by the B19 virus may lead to a wide range of diseases. In the early phase of infection, virus-induced cessation of erythropoiesis among predisposed subjects can lead to abrupt anemia, aplastic or hypoplastic crisis. In immunocompromised individuals persistent parvovirus infection can cause prolonged bone marrow failure (21). Fifth disease (erythema infectiosum) occurs frequently in children and young adults and is associated with varying forms of autoimmune phenomena and transient, sometimes prolonged arthropathy, especially among older individuals. B19 infection during the first two trimesters of pregnancy can lead to fetal hydrops and/or fetal death (4, 19).

Serologic diagnosis of B19 infection is traditionally based on measurement of virus-specific immunoglobulin G (IgG) and IgM and, in particular cases, on measurement of other immunoglobulin classes or IgG subclasses (6, 10, 12). The time of primary infection can be determined by measurement of IgG avidity (14, 16, 28). An even more novel approach is analysis of the epitope-type specificity (ETS) of VP2-IgG (29). Virus-like VP2 particles exhibiting conformational epitopes are recognized by IgG produced at all stages after infection. By contrast, chemically denatured VP2 particles exhibiting linear epitopes are recognized exclusively by acute-phase IgG (29).

In order to understand the mechanism of the ETS phenomenon, we mapped the linear epitopes that are recognized exclusively by antibodies of the acute phase. The identification of an immunodominant acute-phase-specific IgG epitope led to the development of a peptide-based second-generation ETS assay.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Epitope mapping.

Epitope mapping was performed by using 20-aa peptides attached to cellulose membranes (SPOT peptides) (11). The peptides covered the entire VP1–VP2 region with a 3-aa frameshift. One epitope was characterized further with another set of SPOT peptides by alanine and glycine substitutions, by systematic deletions, and by a 1-aa frameshift. The essential amino acids within the epitope were further examined by replacement of each residue with alanine (alanine scanning). In all the SPOT peptide experiments, the membranes were probed with sera pooled at different phases after B19 infection.

The SPOT peptides were synthesized by using an Abimed Auto-Spot Robot ASP222 on cellulose membranes derivatized with polyethylene glycol spacers (amino-PEG membranes; Abimed Analysentechnik GmbH, Langenfeld, Germany). Peptide synthesis was performed by using 9-fluorenylmethoxy carbonyl (Fmoc) amino acids and the synthesis protocols recommended by the manufacturer. Stock solutions of amino acid derivatives were made in 0.5 M N-hydroxybenzotriazole (HOBt) in N-methylpyrrolidone (NMP) and stored in 180-μl aliquots at −20°C. Prior to use, the amino acid derivatives (final concentration, 0.250 M) were activated in situ by addition of 0.275 M N,N′-diisopropylcarbodiimide (DIC) in NMP. After each twice-repeated amino acid addition, the unreacted amino groups were capped with 2% acetic anhydride in N,N′-dimethylformamide (DMF). Fmoc deprotection was carried out by washing the membranes in 20% piperidine in DMF for 10 min. After capping, the membranes were washed with DMF once for 30 s and twice for 2 min each time, and after Fmoc cleavage, they were washed once for 30 s and four times for 2 min each time, followed by methanol washes (once for 30 s and twice for 2 min each time) and drying. An additional capping was performed after the last round of synthesis. The amino acid side chains were deprotected for 1 hour with a mixture of 5 ml of trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), 5 ml of dichloromethane (DCM), 300 μl of tri-isobutylsilane, and 200 μl of water, followed by rinses with DCM, DMF, and methanol. The membranes were dried and stored at −20°C.

For the epitope-mapping assay, the SPOT peptide membranes were treated in a shaker first with methanol followed by Tris-buffered saline, pH 8.0 (TBS), and then with blocking buffer (10% of casein-based blocking buffer [10×] [Genosys, London, United Kingdom] and 0.05 g of sucrose/ml in TBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 [TBS-Tween]) overnight at 4°C. The membranes were washed once with TBS-Tween and incubated at 37°C for 90 min with each serum pool diluted 1:5,000 in blocking buffer. After three washes of 10 min each with TBS-Tween, the membranes were treated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-human IgG (DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark) diluted 1:5,000 in blocking buffer followed by three washes and were incubated for 60 s in freshly prepared enhanced chemiluminescence detection reagent (1.25 mM luminol and 0.2 mM p-coumaric acid in 0.1 M Tris-HCl buffer, pH 8.5, with 0.01% H2O2). Chemiluminescence was visualized on X-ray films exposed for various times (5 s to 10 min). The SPOT peptide membranes were regenerated (twice for 15 min each time at 50°C) with a solution containing 8 M urea, 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), and 0.1% β-mercaptoethanol followed by 50 mM glycine-HCl buffer, pH 2.2 (three times for 10 min each time at 20 to 23°C), rinsed with TBS-Tween and methanol, and dried. The conjugate alone was tested between the analyses of serum pools.

Synthesis of peptide antigen for enzyme immunoassay (EIA).

A 24-aa peptide containing VP2 aa 335 to 359 was synthesized in the solid phase (Applied Biosystems [Foster City, Calif.] 433A peptide synthesizer) by using Fmoc chemistry. A portion of the peptide was biotinylated with preactivated N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) biotin overnight at 37°C, followed by washes with DMF and methanol, and then dried. Final cleavage of the peptide from the solid matrix was carried out under acidic conditions in the presence of scavengers (95% TFA, 2.5% thioanisole, 1.25% ethanedithiol, and 1.25% water). Peptide purity was assessed by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography and matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry.

Synthesis of VP2 capsids.

By using viremic serum as a template, the entire VP2 gene was amplified by PCR using a DNA polymerase with strong 3′→5′ proofreading exonuclease activity (DeepVent; New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.). The PCR product was cloned into a baculovirus transfer vector, p2Bac (Invitrogen, NV Leek, The Netherlands), under the control of the polyhedrin promoter, by standard methods. Bacteria (Escherichia coli DH5α) containing the vector with the correct insert were identified by restriction enzyme analysis.

Spodoptera frugiperda cells (Sf-9 cells) were cotransfected with the recombinant vector DNA and linearized baculovirus DNA (BaculoGold; PharMingen, San Diego, Calif.). Transfection was done with Lipofectin as recommended by the manufacturer (Bethesda Research Laboratories, Life Technologies Inc., Gaithersburg, Md.). After 4 days the cells were harvested and plaque purified twice (30). SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunoblotting showed VP2 production (3), and electron microscopy showed native-like B19 capsids (18), which were purified by ultracentrifugation in a 28% CsCl gradient (at 100,000 × g for 24 h) followed by precipitation with 40% ammonium sulfate. The protein pellet was resuspended in and dialyzed against phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). For EIA, the VP2 capsids were biotinylated by using the EZ-Link Sulfo-NHS-LC-biotinylation kit (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Serum samples.

We had sera from 61 patients with acute infection and, for most patients, one to four follow-up samples taken during convalescence, up to 700 days after the onset of symptoms (28). The total number of acute-phase and follow-up sera was 163. The diagnostic criteria were seroconversion or a ≥4-fold rise in B19-IgG and B19-IgM in each patient. All infections were primary, as verified by significant VP1-IgG avidity maturation. Sera from 78 subjects with B19-IgG, but without IgM, were used as past-immunity controls. Negative-control sera came from 46 nonimmune subjects. Serum pools were made of 5 to 10 individuals' samples each. There were two pools of sera from acute infection, two pools collected several years after infection, and one pool devoid of B19 antibodies.

Antibody assays.

All the samples had been studied for B19-IgG and -IgM with a reference radioimmunoassay (6, 7) and/or a commercial EIA (IDEIA; DAKO). IgG avidity for VP1 was measured by a protein-denaturing EIA (28). IgG binding to conformational versus linear VP2 epitopes was measured with an ETS EIA. Biotinylated VP2 capsids (DAKO) in native and denatured forms were used in the first-generation ETS EIA as described previously (29). In the second-generation ETS EIA, the biotinylated antigens (VP2 capsid at 10 ng/well and VP2 peptide at 6 ng/well) in PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (PBST) were immobilized on streptavidin-coated plates (Labsystems, Helsinki, Finland) by incubation for 60 min at room temperature in a rocking (400 rpm) EIA incubator (iEMS; Labsystems). To minimize nonspecific background, the antigen-sensitized plates were precoated three times, for 10 min each time, with a sample diluent containing a protein and detergent additive (Labsystems). Serum samples (1:200 in PBST) in 100-μl portions were applied for 60 min at room temperature, followed by washes (three times, for 5 min each time) with PBST and treatment for 60 min with anti-human IgG-horseradish peroxidase conjugate (DAKO) diluted 1:2,000 in the sample diluent. After four washes with PBST, orthophenylene diamine substrate and H2O2 were added, the reaction was stopped after 10 min with 0.5 M H2SO4, and the absorbances at 492 nm were recorded. All tests were performed in duplicate.

In all the in-house EIAs, the cutoff values for IgG positivity were set at the mean + 3 standard deviations (SD) of the absorbances of the 46 seronegative subjects.

RESULTS

Epitope scanning.

The entire B19 capsid sequence in SPOT peptides was studied for IgG reactivity in two acute-phase serum pools, one pool representing past immunity, and one pool devoid of B19 antibodies.

Antibody reactivity in ≥4 contiguous spots was regarded as indicative of an antigenic region. As shown in Fig. 1 and Table 1, in the portion unique to VP1, four such regions showed reactivity with the IgG of all the pools tested and hence were not acute phase specific. In the portion common to VP1 and VP2 (VP1 aa 228 to 780), IgG binding at eight antigenic regions was observed. Of these eight regions, four were labeled with all the pools, and one of these four (VP1 aa 677 to 707) appeared to contain two or more overlapping epitopes. One region (VP1 aa 316 to 326) was antigenic only with the pool representing past immunity. Three regions were specific for the acute-phase IgG: residues 292 to 302, 571 to 578, and 493 to 500 (weakly). By far the strongest IgG reactivity with the acute-phase pools, and no reactivity with any other pool, came from peptide spots containing VP1 aa 571 to 578.

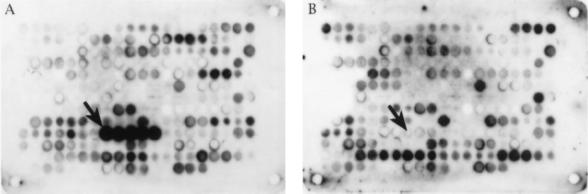

FIG. 1.

Epitope mapping with a pool of sera from individuals with acute B19 infection (A) and a pool of sera from subjects previously infected with B19 (B). Twenty-amino-acid synthetic peptides covering the entire VP1–VP2 sequence were synthesized on cellulose membranes, and IgG binding from the serum pools was visualized with chemiluminescence. Panels A and B show the same membrane containing 255 partially overlapping (3-aa frameshift) B19 peptides. Each spot corresponds to one peptide. After spot 1 (a technical control), the VP1–VP2 sequence flows from left to right in each successive row. The peptides containing VP1 aa 571 to 578 are marked with an arrow.

TABLE 1.

B19 antigenic regions in epitope scanning using serum pools

| VP1 amino acids | VP2 amino acids | Pool(s) showing IgG reactivity |

|---|---|---|

| 31–41 | All (weak) | |

| 55–65 | All (weak) | |

| 85–95 | All | |

| 151–161 | All | |

| 292–302 | 65–75 | Acute phase |

| 316–326 | 89–99 | Past immunity |

| 493–500 | 266–273 | Acute phase (weak) |

| 529–539 | 302–312 | All (weak) |

| 547–554 | 320–327 | All (weak) |

| 571–578 | 344–351 | Acute phase (strong) |

| 667–707 | 440–480 | All |

| 712–722 | 485–505 | All |

Epitope characterization.

The latter region was characterized further with SPOT peptides by 1-aa frameshifting, systematic deletions, and alanine and glycine scanning. These experiments were performed with two acute-phase pools, two past-immunity pools, and one seronegative pool, of which the latter three were nonreactive. Performed with 20-aa SPOT peptides covering the sequence 555 to 601, 1-aa frameshifting showed strong acute-phase IgG reactions with aa 571 to 577, whereas no reactions were obtained with peptides lacking 1 or more of these 7 amino acids. Hence, the frameshifting experiments mapped the acute-phase-specific epitope to a heptapeptide, Lys-Tyr-Val-Thr-Gly-Ile-Asn (KYVTGIN), at VP1 aa 571 to 577.

In the alanine and glycine substitutions the KYVTGIN sequence and its vicinity were replaced with increasing numbers of these amino acids, from VP1 aa 568 downstream and from VP1 aa 581 upstream, without changing the peptide length. The amino acid deletions followed a similar design except that the peptide was shortened. All these experiments gave the same result: substitutions or deletions extending to the KYVTGIN sequence abolished its reactivity with the acute-phase serum IgG, whereas perturbations in its surroundings had no such effect. Interestingly, all the serum pools weakly recognized long repeats of alanine or glycine; however, the intensity of these reactions was only a fraction of that obtained with the acute-phase IgG on the peptides containing the KYVTGIN sequence.

In alanine scanning, VP1 aa 562 to 581 in the SPOT peptides were replaced one by one with alanine. As shown in Fig. 2, within KYVTGIN the essential amino acids were K, T, G, I, and possibly N, whereas replacement of Y or V did not markedly affect reactivity with the acute-phase IgG.

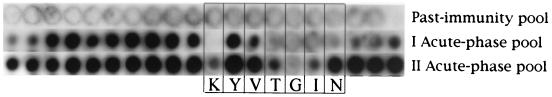

FIG. 2.

Alanine scanning exploring the effect of point mutations on the reactivity of IgG in a past-immunity serum pool and two acute-phase serum pools. Each of the three rows contains the same set of synthetic peptides, and all the spots contain VP1 aa 562 to 581 (VP2 aa 335 to 354). The first spot on the left contains peptides with the native amino acid sequence, and the subsequent spots (from left to right) contain peptides point mutated sequentially with alanine. The boxed area marks the spots in which the KYVTGIN sequence has been mutated, at the sites indicated by the letters.

KYVTGIN-antibody EIA.

The synthetic peptide and the native VP2 capsids, linked with biotin and streptavidin in the solid phase, were studied by EIA for reactivity with IgG in individual sera (Fig. 3). In keeping with the definition of the EIA cutoffs, among the 46 nonimmune controls, 45 (97.8%) showed IgG absorbances below cutoff with the native VP2 antigen. Also with the KYVTGIN antigen, 45 of 46 nonimmune controls gave negative results.

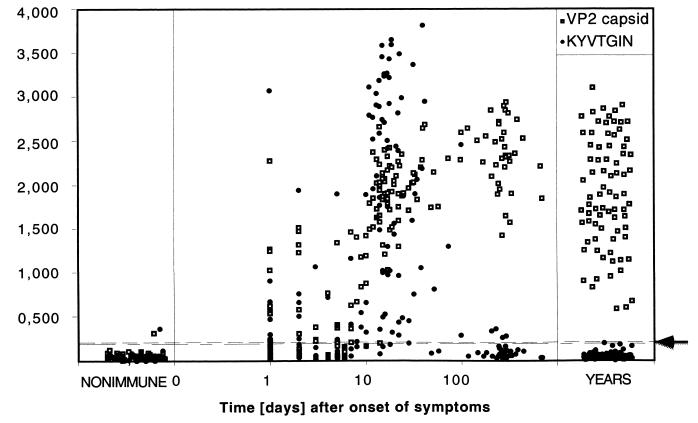

FIG. 3.

Kinetics of IgG response for the native VP2 capsids and the KYVTGIN peptide. Individual sera from 46 nonimmune subjects and 78 subjects with past immunity, and 163 acute-phase or followup sera from 61 patients, were used. The y axis shows A492. Dashed lines mark cutoffs for IgG positivity for the VP2 capsids (lower line; A492 = 0.198) and the KYVTGIN peptide (upper line; A492 = 0.205).

During the acute phase and convalescence, all samples collected more than 2 weeks after the onset of symptoms were IgG positive for the native VP2 capsid. With the KYVTGIN peptide, most sera collected between days 10 and 50 after onset were reactive, whereas most samples collected >100 days after onset were devoid of KYVTGIN-IgG reactivity.

All the 78 control sera from subjects with preexisting immunity gave positive IgG results with the native VP2 capsid antigen. Noticeably, of the same past-immunity sera, none was reactive with the KYVTGIN peptide (Fig. 3).

Second-generation epitope-typing EIA.

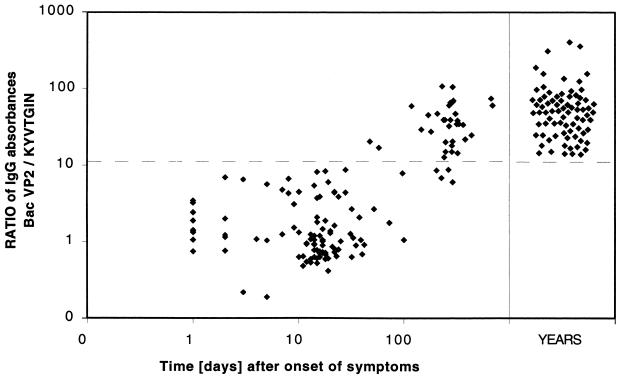

From the EIA absorbances of the previous experiment, we calculated the ratios of ETS, i.e., the ratios between IgG binding to the native VP2 and IgG binding to the synthetic peptide epitope. In this assay the cutoff for separation of acute infection from past immunity was set at the mean + 3 SD of the ETS ratios of the sera collected within 3 months after onset. Among 105 B19-IgG-seropositive acute-phase samples, 103 (98.1%) yielded ETS ratios below cutoff. From the donors of the other two samples, earlier acute-phase sera showed low ETS ratios, compatible with acute B19 infection. By contrast, all the 78 past-immunity controls showed ETS ratios exceeding the diagnostic cutoff (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Second-generation ETS EIA in diagnosis, showing ratios of IgG absorbances for the native VP2 antigen and the KYVTGIN peptide. The dashed line marks the diagnostic cutoff (ETS ratio, 1.3).

DISCUSSION

We mapped the acute-phase specificity of the primary structure of the B19 major structural protein to an immunodominant epitope and characterized its structure-function relation. Using this heptapeptide (KYVTGIN) epitope and native VP2 capsids, we set up a new ETS assay for diagnosis of B19 primary infections.

In terms of its acute-phase specificity, the KYVTGIN-IgG response is strikingly different from the long-standing IgG response against the unique part of VP1 (14, 20, 24, 27, 29, 31). On the other hand, the kinetics of the KYVTGIN-IgG response was very similar to that of the IgG response for the entire VP2 capsid protein in denatured form (29). The epitope-scanning data suggested that, although it was the most important, KYVTGIN was not the only acute-phase-specific linear epitope in the VP2 molecule. Two relatively weaker acute-phase IgG epitopes of our study (VP2 aa 65 to 75 and 266 to 273) have been studied earlier for B19 antigenicity (13, 26).

As we have recently shown with chemically denatured protein antigens, IgG binding to the primary structure of VP2 is specific for B19 infection, i.e., is not due to cross-reactive antibodies from other acute viral infections (29). The IgG-KYVTGIN reactions presently observed by EIA could be completely abolished by the same KYVTGIN peptide in solution (17a), adding proof for the specificity of the KYVTGIN-IgG response.

Recent studies on pathogens structurally and biologically unrelated to B19, the lentiviruses human immunodeficiency virus (8) and equine infectious anemia virus (15), have shown a transition from a linear-epitope to a conformational-epitope specificity of IgG, kinetically similar to our findings with VP2-IgG. Furthermore, a linear epitope in the envelope glycoprotein of Sin Nombre virus appears to be specific for acute-phase IgG (17). It therefore appears that B-cell responses against certain entirely nonrelated viruses have a feature in common, the molecular and cell biologic mechanism of which is thus far incompletely understood. A simple explanation, cryptic residence, appears unlikely for the B19 virus because of the external localization of the KYVTGIN sequence on the surface protrusions between the twofold and threefold axes of the VP2 capsid (5).

Within this immunodominant heptapeptide, VP1 aa 571 to 577, corresponding to VP2 aa 344 to 350, merely four or five residues (Lys344, Thr347, Gly348, Ile349, and Asn350) were the actual hot spots for binding of acute-phase IgG. In this respect the KYVTGIN-specific human IgG resembles a well-characterized monoclonal antilysozyme antibody (1). By sequence mapping the KYVTGIN epitope is part of a long region (VP2 aa 266 to 376) shown to be immunogenic in rabbits (23). Binding sites for neutralizing antibodies (2, 22, 25) localize in the vicinity of KYVTGIN. However, even if high-resolution data on the topology of this sequence in the B19 capsid are available (5), its function in the virus warrants further study.

In conclusion, in the human parvovirus major structural protein we have detected an immunodominant B-cell epitope eliciting antibodies exclusively during the early phase of B19 infection. Using this linear epitope specific for acute-phase IgG, and conformational VP2 antigenicity recognizing IgG at all stages after infection, we have set up a sensitive and specific, technically straightforward new method. In confirmatory use this second-generation ETS EIA should improve the accuracy of diagnosis of B19 primary infections.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Helsinki University Central Hospital Research and Education Fund, the Finnish Technology Advancement Fund, the Finnish Science Academy, and the Päivikki and Sakari Sohlberg Foundation.

We thank Antti Vaheri and Leena Kostamovaara for help with Sf-9 cell culturing and Mavis Agbandje-McKenna, Matti Kaartinen, and Ilkka Seppälä for stimulating discussions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Braden B C, Goldman E R, Mariuzza R A, Poljak R J. Anatomy of an antibody molecule: structure, kinetics, thermodynamics and mutational studies of the antilysozyme antibody D1.3. Immunol Rev. 1998;163:45–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1998.tb01187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown C S, Jensen T, Meloen R H, Puijk W, Sugamura K, Sato H, Spaan W. Localization of an immunodominant domain on baculovirus-produced parvovirus B19 capsids: correlation to a major surface region on the native virus particle. J Virol. 1992;66:6989–6996. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.12.6989-6996.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown C S, van Lent J W M, Vlak J M, Spaan W J M. Assembly of empty capsids by using baculovirus recombinants expressing human parvovirus B19 structural proteins. J Virol. 1991;65:2702–2706. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.5.2702-2706.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown T, Anand A, Richie L D, Clewley L P, Reid T M S. Intrauterine parvovirus infection associated with hydrops fetalis. Lancet. 1984;ii:1033–1034. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)91126-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chipman P R, Agbandje-McKenna M, Kajigaya S, Brown K E, Young N S, Baker T S, Rossman M G. Cryo-electron microscopy studies of empty capsids of human parvovirus B19 complexed with its cellular receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:7502–7506. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen B J, Mortimer P P, Pereira M S. Diagnostic assays with monoclonal antibodies for the human serum parvovirus-like virus (SPLV) J Hyg Camb. 1983;91:113–130. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400060095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen B J. Detection of parvovirus B19-specific IgM by antibody capture radioimmunoassay. J Virol Methods. 1997;66:1–4. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(97)00048-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cole K S, Murphey-Corb M, Narayan O, Joag S V, Shaw G M, Montelaro R C. Common themes of antibody maturation to simian immunodeficiency virus, simian-human immunodeficiency virus, and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infections. J Virol. 1998;72:7852–7859. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.10.7852-7859.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cotmore S F, McKie V C, Anderson L J, Astell C R, Tattersall P. Identification of the major structural and nonstructural proteins encoded by human parvovirus B19 and mapping of their genes by procaryotic expression of isolated genomic fragments. J Virol. 1986;60:548–557. doi: 10.1128/jvi.60.2.548-557.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Erdman D D, Usher M J, Tsou C, Caul E O, Gary W, Kajigaya S, Young N S, Anderson L J. Human parvovirus B19 specific IgG, IgA, and IgM antibodies and DNA in serum specimens from persons with erythema infectiosum. J Med Virol. 1991;35:110–115. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890350207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frank R. Spot-synthesis: an easy technique for the positionally addressable, parallel chemical synthesis on a membrane support. Tetrahedron. 1992;48:9217–9232. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Franssila R, Söderlund M, Brown C S, Spaan W J M, Seppälä I, Hedman K. IgG subclass response to human parvovirus B19 infection. Clin Diagn Virol. 1996;6:41–49. doi: 10.1016/0928-0197(96)00156-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fridell E, Trojnar J, Wahren B. A new peptide for human parvovirus B19 antibody detection. Scand J Infect Dis. 1989;21:597–603. doi: 10.3109/00365548909021686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gray J, Cohen B, Desselberger U. Detection of human parvovirus B19-specific IgM and IgG antibodies using a recombinant viral VP1 antigen expressed in insect cells and estimation of infection time by testing for antibody avidity. J Virol Methods. 1993;44:11–24. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(93)90003-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hammond S A, Cook S J, Lichtenstein D L, Issel C J, Montelaro R C. Maturation of the cellular and humoral immune responses to persistent infection in horses by equine infectious anemia virus is a complex and lengthy process. J Virol. 1997;71:3840–3852. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.5.3840-3852.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hedman K, Lappalainen M, Söderlund M, Hedman L. Avidity of IgG in serodiagnosis of infectious diseases. Rev Med Microbiol. 1993;4:123–129. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hjelle B, Jenison S, Torrez-Martinez N, Herring B, Quan S, Polito A, Pichuantes S, Yamada T, Morris C, Elgh F, Wang Lee H, Artsob H, Dinello R. Rapid and specific detection of Sin Nombre virus antibodies in patients with hantavirus pulmonary syndrome by a strip immunoblot assay suitable for field diagnosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:600–608. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.3.600-608.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17a.Kaikkonen, L., et al. Unpublished data.

- 18.Kajigaya S, Shimada T, Fujita S, Young N S. A genetically engineered cell line that produces empty capsids of B19 (human) parvovirus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:7601–7605. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.19.7601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knott P D, Weply G A C, Anderson M J. Serologically proved intrauterine infection with parvovirus. Br Med J. 1984;289:1660. doi: 10.1136/bmj.289.6459.1660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koch W C. A synthetic parvovirus B19 capsid protein can replace viral antigen in antibody-capture enzyme immunoassays. J Virol Methods. 1995;55:297–303. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(95)00046-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kurtzman G J, Ozawa K, Cohen B, Hanson G, Oseas R, Young N R. Chronic bone marrow failure due to persistent B19 parvovirus infection. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:287–294. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198707303170506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loughrey A C, O'Neill H, Coyle P V, DeLeys R. Identification and use of a neutralizing epitope of parvovirus B19 for the rapid detection of virus infection. J Med Virol. 1993;39:97–100. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890390204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saikawa T, Anderson S, Momoeda M, Kajigaya S, Young N S. Neutralizing linear epitopes of B19 parvovirus cluster in the VP1 unique and VP1-VP2 junction regions. J Virol. 1993;67:3004–3009. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.6.3004-3009.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salimans M M M, van Bussel M J A W M, Brown C S, Spaan W J M. Recombinant parvovirus B19 capsids as a new substrate for detection of B19-specific IgG and IgM antibodies by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. J Virol Methods. 1992;39:247–258. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(92)90098-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sato H, Hirata J, Furukawa M, Kuroda N, Shiraki H, Maeda Y, Okochi K. Identification of the region including the epitope for a monoclonal antibody which can neutralize human parvovirus B19. J Virol. 1991;65:1667–1672. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.4.1667-1672.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sato H, Hirata J, Shiraki H, Maeda Y, Okochi K. Identification and mapping of neutralizing epitopes of human parvovirus B19 by using human antibodies. J Virol. 1991;65:5485–5490. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.10.5485-5490.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schwartz T F, Modrow S, Hotteträger B, Höflächer B, Jäger G, Schartl W, Sumazaki R, Wolf H, Middeldorp J, Roggendorf M, Deinhardt F. New oligopeptide immunoglobulin G test for human parvovirus B19 antibodies. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:431–435. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.3.431-435.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Söderlund M, Brown C S, Cohen B J, Hedman K. Accurate serodiagnosis of B19 parvovirus infections by measurement of IgG avidity. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:710–713. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.3.710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Söderlund M, Brown C S, Spaan W J M, Hedman L, Hedman K. Epitope type-specific IgG responses to capsid proteins VP1 and VP2 of human parvovirus B19. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:1431–1436. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.6.1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Summers M D, Smith G E. A manual of methods for baculovirus vectors and insect cell culture procedures. Tex Agric Exp Stn Bull. 1987;1555:1–56. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yaegashi N, Shiraishi H, Tada K, Yajima A, Sugamura K. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for IgG and IgM antibodies against human parvovirus B19: use of monoclonal antibodies and viral antigen propagated in vitro. J Virol Methods. 1989;26:171–182. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(89)90146-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]