Abstract

Introduction

Migraine is mostly a female disorder because of its lower prevalence in men. Less than 20% of patients included in the available studies on migraine treatments are men; hence, the evidence on migraine treatments might not apply to men. The aims of the present study were to provide reliable information on the effectiveness of onabotulinumtoxinA (BT-A) for chronic migraine in men and to compare clinical benefits between men and women.

Methods

We performed a pooled patient-level gender-specific analysis of real-life data on BT-A for chronic migraine of patients followed-up to 9 months. We reported the 50% responder rates during each BT-A cycle, defined as percentage of reduction in monthly headache days (MHDs) compared to baseline, along with 75% and 30% responder rates. We also reported the mean decrease in MHDs and in days of acute medication use (DAMs) during each BT-A cycle as compared to baseline. We also evaluated the reasons for stopping the treatment within the third cycle.

Results

We included an overall cohort of 2879 patients, 522 of whom (18.1%) were men. In men, 50% responder rates were 27.7% during the first BT-A cycle, 29.2% during the second, and 35.6% during the third cycle; in women, the corresponding rates were 26.6%, 33.5%, and 41.0%. In the overall cohort, responder rates did not differ between men and women during the first two cycles; during the third cycle, the distribution was different (P < 0.001) mostly because of higher rates of treatment stopping and non-responders in men. In the propensity score matched cohort, the trend was maintained but lost its statistical significance. Both men and women had a significant decrease in MHDs and in DAMs with BT-A treatment (P < 0.001). There were no gender differences in those changes with the only exception of MHD decrease which, during the third cycle, was lower in men than in women (7.4 vs 8.2 days, P = 0.016 in the overall cohort and 9.1 vs 12.5 days, P = 0.009 in the propensity score matched cohort). At the end of follow-up, 152 men and 485 women stopped BT-A treatment (29.1% vs 20.6%; P < 0.001). The relative proportion of patients stopping treatment because of inadequate response (less than 30% decrease in MHDs from baseline) was higher in men than in women (42.8% vs 39.6%), while the proportion of patients stopping because of adverse events was higher in women than in men (5.6% vs 0%; P = 0.031).

Conclusions

Our pooled analysis suggests that the response to BT-A is significant in both men and women with a small gender difference in favor of women. Men tended to stop the treatment more frequently than women. We emphasize the need for more gender-specific data on migraine treatments from randomized controlled trials and observational studies.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40122-021-00328-y.

Keywords: Migraine, OnabotulinumtoxinA, Chronic migraine, Men, Gender difference

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| The available data on gender-specific response to migraine treatments are scarce because of the low proportion of male study participants. |

| We performed a large, retrospective, multicenter study to assess the response to onabotulinumtoxinA for chronic migraine in men compared with women. |

| What was learned from this study? |

| We found that onabotulinumtoxinA was effective in both men and women; there was a slight gender difference in favor of women that was, however, not substantial, as it lost significance after propensity score matching. |

| Persistence to onabotulinumtoxinA treatment was lower in men than in women; this finding is in line with previous data on oral migraine treatments and should encourage headache physicians to monitor men’s persistence to treatments. |

Introduction

Migraine is the most prevalent neurological disease, affecting about 20% of the European population [1]. Migraine has remarkable gender differences. Its prevalence, during adulthood, is three times higher in women than in men [2]. Additionally, women with migraine have generally more severe attacks and a higher disease-related disability [3]. On the other hand, men with migraine are less likely to receive the correct diagnosis than women [4].

Factors which may contribute to gender differences are multiple and not entirely understood. Genetic factors and the periodic fluctuations of estrogen levels during the ovarian cycle contribute to the increased susceptibility to migraine in women [3, 5, 6]. On the other hand, hormonal stability and a potential preventive effect of male sex hormones contribute to the lower prevalence of migraine in men [7, 8]. The trigeminal ganglion, the structure supposed to play a pivotal role in generating migraine pain, has a sexual dimorphism as it hosts estrogen receptors [9] that can respond to estrogen fluctuations. Additional psychosocial factors which are remarkably different between men and women, including coping abilities and pain catastrophizing, may impact on the course of migraine and affect its management [10].

Providing gender-specific information for treatments is a mainstay of modern medicine and is of utmost importance in a disorder such as migraine [11]. Unfortunately, gender-specific information for migraine treatments is scarce and mostly related to some data on triptans [12–14]. As men were in a minority (less than 20% of the total study population) in studies aiming to develop migraine preventive treatments [3, 15–20], generalizability to men of the overall findings of those studies is unclear.

OnabotulinumtoxinA (BT-A) is the first treatment that was approved specifically for CM. Randomized clinical trials [15, 16, 21–23] and real-life studies [24–26] confirmed the efficacy and safety of BT-A in mixed populations composed of many more women than men. In the PREEMPT studies, men comprised 12.4% of patients treated with BT-A and 14.8% of those treated with placebo [23]. Real-life studies equally included few men and did not report the gender-specific effect of BT-A [24, 25, 27–32]. The response to migraine treatments can be influenced by the same genetic, hormonal, medical, and psychological factors that determine gender differences in migraine susceptibility. Given the availability of a large amount of data from a European collaboration [33], we aimed to provide reliable information on the effects of treatment with BT-A in men with CM, which were so far underrepresented in available studies, and to compare clinical benefits between men and women.

Methods

This is a pooled patient-level analysis of data from real-life studies on patients with CM treated with BT-A at 16 European headache centers. The methods of the study have been previously published [33]. Briefly, all the centers which joined this project had already performed a local real-life prospective data collection on patients with CM. All included patients had a CM diagnosis according to the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD) criteria, were aged at least 18 years, and received treatment with BT-A 155–195 units quarterly according to the phase 3 REsearch Evaluating Migraine Prophylaxis Therapy (PREEMPT) protocol [15]. Inclusion periods varied across centers and ranged from 2010 to 2020.

Pooling of previously collected data for the present collaborative study was approved by the Internal Review Board of the University of L’Aquila with protocol number 23/2020; local ethical approval to pool data was obtained if needed. All centers had their former data collections approved by the local ethics committees if necessary, according to the local regulations; informed consent was obtained from patients. The study was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments.

Variables and Outcomes

All included patients were followed up for 9 months, irrespective of treatment discontinuation. The 9-month follow-up was chosen to include the first three BT-A injection sets, after which more than 70% of patients showed a 50% response according to the PREEMPT trials [34].

Monthly headache days (MHDs) and monthly days of acute medication use (DAMs) were collected in all centers by using headache diaries. Baseline was defined as the monthly mean of the 3 months preceding BT-A treatment. Patients reporting at least a 50% reduction in MHDs during a BT-A cycle compared with baseline were defined as “50% responders” during that cycle. We also defined patients as “30–49% responders” if reporting a 30–49% reduction in MHDs and as “75% responders” if reporting at least a 75% reduction in MHDs. Patients reporting a smaller than 30% reduction in MHDs compared with baseline were defined as “non-responders”.

For each patient who stopped the treatment before the third cycle, we recorded whether stopping occurred because of inadequate response, good response, adverse events, or loss to follow-up. Inadequate response was defined as application of a “negative stopping rule” as per the UK guidelines (i.e., smaller than 30% decrease in MHDs from baseline after two BT-A cycles [35]) or patient decision due to perceived ineffectiveness of BT-A. Good response was defined as application of a “positive stopping rule” as per the UK guidelines (i.e., less than 15 MHDs for more than 3 months [35]) or patient decision due to perceived high effectiveness of BT-A.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were reported as numbers and proportions and means and standard deviations (SDs), as appropriate. We performed chi-square test with adjustment by linear trend data to compare categorical variables and Student’s t test to compare continuous variables according to gender. Continuous outcome variables, including MHDs and DAMs, were imputed by carrying forward the last observation in patients withdrawing the treatment. All analyses used the intent-to-treat population including all patients who started BT-A treatment. The co-primary efficacy outcomes of our analyses included the proportion of 50% responders, mean decrease in MHDs from baseline, and mean decrease in DAMs from baseline during each BT-A cycle. Secondary efficacy outcomes included the proportions of 30% and 75% responders during each BT-A cycle. We also reported the proportion of patients stopping the treatment within the third cycle with reasons. Given the absence of gender-specific data on BT-A, all outcomes were considered as exploratory; hence, no adjustment for multiple comparisons was performed.

Variables were considered for the analyses if available for at least two thirds of patients; no imputation was done for missing baseline data. To impute missing diary data of patients stopping the treatment, we repeated the last available observation according to a “last observation carried forward” approach.

To adjust for possible differences between men and women, we performed a propensity score matching with the exact method between a subset of men and one of women, considering age, CM duration, and baseline MHDs as matching variables. Age was chosen as a matching variable to ensure a balance of demographic characteristics between men and women; CM duration and baseline MHDs were chosen because previous studies showed that high frequency of headache at baseline and a long history of CM negatively affect the response to BT-A [31, 36]. To assess the validity of the propensity score model, we performed a test of significance on the matched variables between men and women. To account for possible age differences, a comparison between men and women within three age groups (18–34, 35–49, and 50 years or older) was also performed in the overall cohort, referring to the third BT-A cycle.

No sample size calculation was planned, as we used a convenience sample based on the available data. Two-tailed P for significance was set at less than 0.05. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 20 and R version 4.0.0.

Results

We included an overall cohort of 2879 patients, 522 of whom (18.1%) were men. Supplemental Table 1 reports the proportion of men in each center, which ranged from 10.3% to 27.1%. Men were older than women (47.8 ± 13.2 vs 46.3 ± 12.1 years; P = 0.024), while the remaining baseline characteristics did not differ between men and women (Table 1). The propensity score matched cohort included 291 patients, 121 of whom were men (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the included subjects in the overall cohort and in the propensity score matched cohort

| Men | Women | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall cohort, n | 522 | 2357 | |

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 47.8 ± 13.2 | 46.3 ± 12.1 | 0.024 |

| Medication overuse, n (%) | 366 (70.1) | 1686 (71.5) | 0.385 |

| Baseline headache days, mean ± SD | 23.8 ± 6.3 | 23.8 ± 5.9 | 0.900 |

| CM duration (years), mean ± SD | 8.5 ± 9.0 | 7.9 ± 7.8 | 0.209 |

| Acute medication days (number), mean ± SD | 18.8 ± 9.7 | 19.5 ± 8.9 | 0.157 |

| Propensity score matched cohort, n | 121 | 170 | |

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 45.2 ± 10.9 | 44.9 ± 11.1 | 0.822 |

| Medication overuse, n (%) | 85 (70.2) | 121 (71.2) | 0.912 |

| Baseline headache days, mean ± SD | 27.1 ± 5.0 | 27.2 ± 4.9 | 0.794 |

| CM duration (years), mean ± SD | 6.1 ± 5.7 | 6.2 ± 5.5 | 0.916 |

| Acute medication days (number), mean ± SD | 20.5 ± 10.8 | 20.7 ± 10.4 | 0.884 |

CM indicates chronic migraine, SD standard deviation

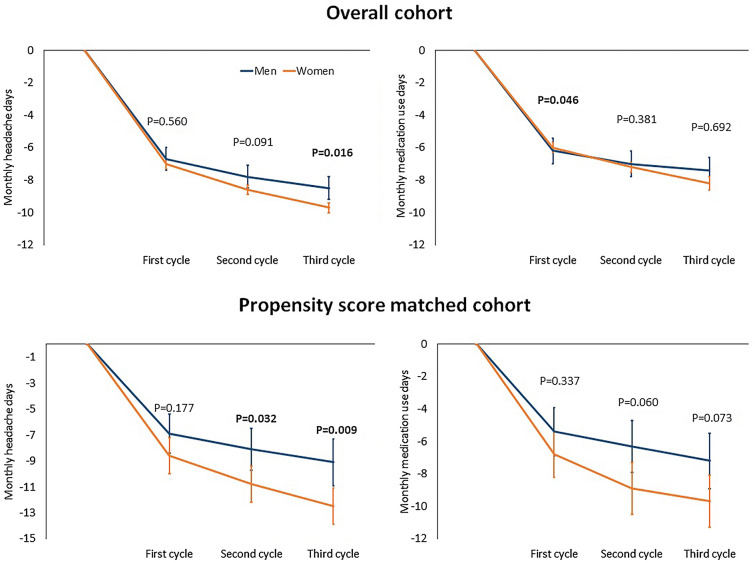

In the overall cohort of men, 145 (27.7%) were 50% responders during the first BT-A cycle, 152 (29.2%) during the second, and 186 (35.6%) during the third cycle (Fig. 1). In the overall cohort of women, the corresponding numbers were 628 (26.6%), 790 (33.5%), and 967 (41.0%) respectively (Fig. 1). At the statistical analysis, response rates did not differ between men and women in the overall cohort during the first cycle; during the second and the third cycle, the distribution was different (P = 0.019 and P = 0.010, respectively) mostly because of higher rates of treatment stopping and non-responders in men compared to women. In the propensity score matched cohort, the numerical difference was still present but lost its statistical significance (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Response and discontinuation rates of onabotulinumtoxinA during the first three cycles in the overall cohort (men = 522; women = 2357) and in the propensity score matched cohort (men = 121; women = 170). P values refer to the comparison between men and women according to the chi-squared test adjusted for linear trend data

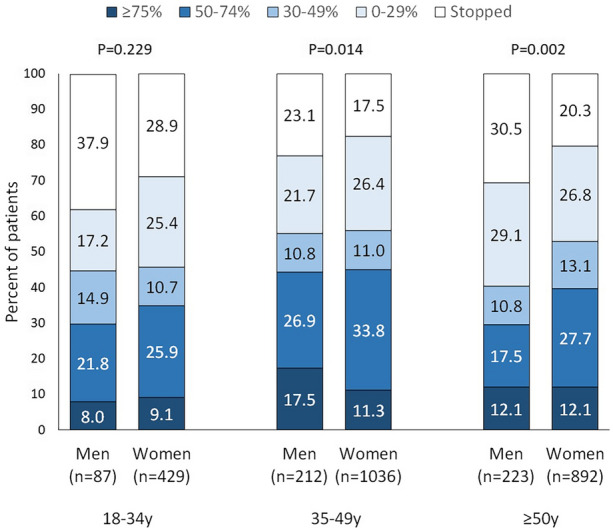

In the overall cohort, 87 (%) men were aged 18–34 years, 212 (%) 35–49 years, and 223 (%) 50 years or older; the corresponding numbers for women were 429 (%), 1036 (%), and 892 (%). During the third BT-A cycle, response rates were different between men and women in patients aged 35–49 years (P = 0.014) and in those aged 50 years or older (P = 0.002), mostly because of a higher rate of treatment stopping in men than in women (Fig. 2). In patients aged 18–24 years, there was no gender difference (P = 0.229; Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Response and discontinuation rates of onabotulinumtoxinA during the third cycle according to gender and age groups. P values refer to the comparison between men and women according to the chi-squared test

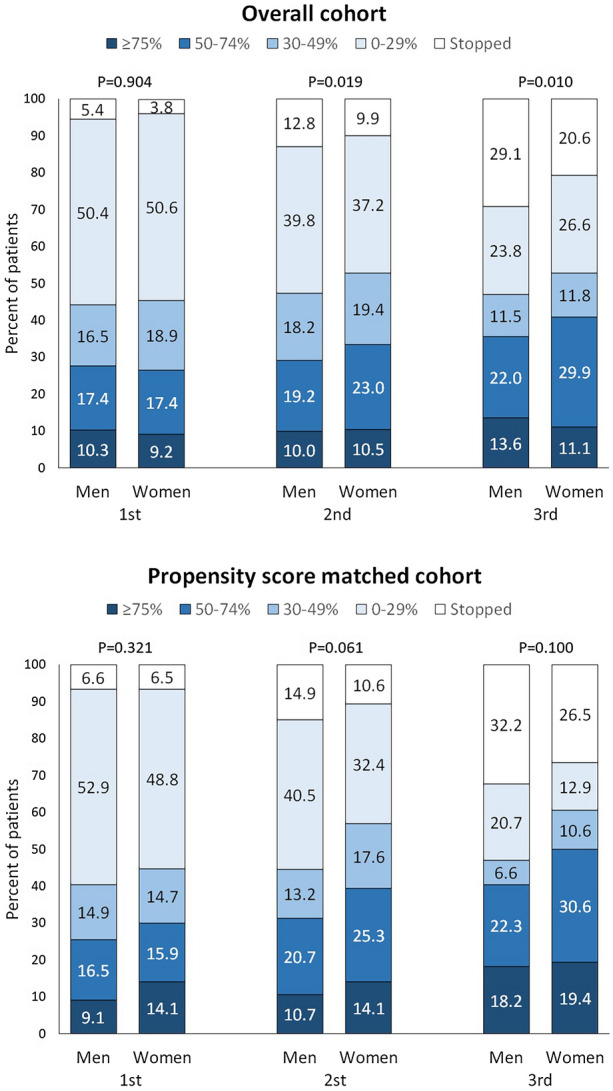

In the overall cohort of men, mean MHDs decreased from baseline by 6.7 days (95% confidence interval [CI] 6.0–7.3; P < 0.001) during the first cycle, 7.8 days (95% CI 7.1–8.5; P < 0.001) during the second cycle, and 8.5 days (95% CI 7.8–9.3; P < 0.001) during the third cycle; the corresponding numbers in women were 7.0 days (95% CI 6.7–7.3; P < 0.001), 8.6 days (95% CI 8.3–8.9; P < 0.001), and 9.7 days (95% CI 9.4–10.0; P < 0.001) (Fig. 3). The decrease in MHDs was comparable in men and women during the first two cycles, while it was lower in men than in women during the third cycle (P = 0.016; Fig. 3). In the propensity score matched cohort, mean MHDs decreased from baseline in men by 6.9 days (95% CI 5.4–8.4; P < 0.001) during the first cycle, 8.1 days (95% CI 6.5–9.8; P < 0.001) during the second cycle, and 9.1 days (95% CI 7.4–10.9; P < 0.001) during the third cycle; the corresponding numbers in women were 8.6 days (95% CI 7.2–9.9; P < 0.001), 10.8 days (95% CI 9.4–12.2; P < 0.001), and 12.5 days (95% CI 9.4–10.0; P < 0.001) (Fig. 3). The decrease in MHDs from baseline was significant (P < 0.001) in both men and women during all the three BT-A cycles; however, men reported a lower decrease in MHDs than women during the second (P = 0.032) and the third cycle (P = 0.009) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Mean decrease in monthly headache days and monthly acute medication use days over the study period in the overall cohort and in the propensity score matched cohort. P values for men and women are less than 0.001 at all timepoints with respect to baseline. The P values shown in the figure refer to the comparison between men and women (t tests). Error bars show 95% confidence intervals

In the overall cohort of men, mean DAMs decreased from baseline by 6.2 days (95% CI 5.4–7.0; P < 0.001) during the first cycle, 7.0 days (95% CI 6.2–7.8) during the second cycle, and 7.4 days (95% CI 6.5–8.2; P < 0.001) during the third cycle; the corresponding numbers in women were 6.0 days (95% CI 5.6–6.3; P < 0.001), 7.2 days (95% CI 6.9–7.6; P < 0.001) during the second cycle, and 8.2 days (95% CI 7.8–8.6; P < 0.001) during the third cycle. The decrease in DAMs from baseline did not differ between men and women during the second and third cycle, while it was slightly higher in men than in women during the first cycle (P = 0.046). In the propensity score matched cohort, mean DAMs decreased in men from baseline by 5.4 days (95% CI 3.9–6.9; P < 0.001) during the first cycle, 6.3 days (95% CI 4.7–8.0) during the second cycle, and 7.2 days (95% CI 5.4–9.0; P < 0.001) during the third cycle; the corresponding numbers in women were 6.8 days (95% CI 5.3–8.2; P < 0.001), 8.9 days (95% CI 7.3–10.6; P < 0.001) during the second cycle, and 9.7 days (95% CI 8.2–11.3; P < 0.001) during the third cycle. There were no gender differences during any of the three BT-A cycles (Fig. 3).

Table 2 reports the proportions of patients stopping BT-A treatment with reasons in the overall cohort. At the end of follow-up, 152 men and 485 women stopped BT-A treatment (29.1% vs 20.6%; P < 0.001). Among men stopping the treatment, the reason was inadequate response for 65 patients (42.8%), and good response for 52 (34.2%), while 35 (23.0%) were lost to follow-up; among women stopping the treatment, the reason was inadequate response for 192 patients (39.6%), good response for 162 (33.4%), and adverse events for 27 (5.6%), while 104 (21.4%) were lost to follow-up. The causes for treatment stopping were different between men and women (P = 0.031).

Table 2.

Detail of onabotulinumtoxinA stopping rates and reasons

| Overall cohort (n = 2879) | Men (n = 522) | Women (n = 2357) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inadequate response, n (%) | 257 (8.9) | 65 (12.5) | 192 (8.1) |

| Good response, n (%) | 214 (7.4) | 52 (10.0) | 162 (6.9) |

| Adverse events, n (%) | 27 (0.9) | 0 | 27 (1.1) |

| Lost to follow-up, n (%) | 139 (4.8) | 35 (6.7) | 104 (4.4) |

| Total, n (%) | 637 (22.1) | 152 (29.1) | 485 (20.6) |

P = 0.031 for distribution (men vs women)

Discussion

Reporting gender-specific data is relevant to discuss with patients the expected outcome of BT-A treatment and to improve our understanding of migraine and its gender differences. To our knowledge, our data are the first gender-specific analysis on the efficacy of BT-A. We found that BT-A was effective in both men and women; the proportion of responders increased over the first three BT-A cycles and more than one third of patients were 50% responders during the third cycle in both genders. A significant and stable decrease in headache frequency and acute medication use was also found in both men and women. We found a slightly lower response in men than in women that was, however, apparent only during the third BT-A treatment cycle and likely not substantial from a clinical point of view. The difference was significant only in patients aged 35 years or more, even if the non-significant difference in younger patients could be attributed to low numbers. As the difference was not present after propensity score matching, it can be attributed to differences in some characteristics of men and women which may affect treatment response. A further finding was that, at the end of the study follow-up, men reported a lower decrease in headache frequency compared with women. Again, the between-group difference was small, both in the overall and in the propensity score matched cohort. Besides, acute medication use did not show gender differences.

In our study, men tended to stop BT-A treatment more often than women. As BT-A treatment stopping was due to both inadequate and good response (Table 2), the lower persistence with BT-A treatment of men might reflect a different attitude towards care rather than a lower response to the treatment. The issue of a lower persistence to migraine treatments in men than in women was already noted by previous literature [37, 38]; however, definite reasons for that gender difference are still not clear. Factors potentially impairing men’s persistence to CM treatments should be adequately monitored and managed in clinical practice.

Gender differences in migraine primarily depend on sex hormones. The high fluctuations in estrogen levels that accompany the menstrual cycle and perimenopause are associated with a possible exacerbation of migraine, leading to the particularly higher prevalence of migraine in women than in men during the female fertile period [39–41]. On the other hand, male sex hormones are likely protective against migraine, as suggested by the cessation of migraine in women treated with testosterone for reasons other than their migraines [7]. Animal models indicate that estrogen receptors are present in the trigeminal ganglion, which releases calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), a peptide implied in migraine pain [42, 43]. Besides, a correlation was found between the different phases of estrous cycle and the amount of CGRP released from the trigeminovascular system [9]. In humans, there is also evidence that female sex hormone fluctuations can alter the “set point” for the generation of migraine attacks [44]. However, the ways in which estrogens modulate migraine-generating structures are still not clear. Besides, it is not known how estrogens can interact with migraine preventatives acting on CGRP release, which include BT-A [45]. Other factors which may contribute to gender differences in the presentation of migraine and its response to medication include comorbidities and mostly psychiatric conditions. Two cross-sectional studies suggest that the association between symptoms of anxiety or depression and migraine is stronger in men than in women [46, 47]. Depressive symptoms have been already associated with lower response to BT-A [48]. Hence, the effect of comorbidities such as anxiety or depression could explain a lower response to BT-A in men compared with women. However, the presence of anxiety and depression could not be retrieved from our dataset.

The main strength of our study was the inclusion of a high number of men. We also reported the first available data on adherence to BT-A treatment in men compared with women. Being multicenter, international, and reflecting the real-life headache care setting, our findings have a good generalizability. Additionally, all study centers prospectively recruited all BT-A treated patients, thus reducing the possibility of selection bias. A further strength of the present paper is the use of an exact propensity score matching between men and women which enhanced the between-group comparability. Propensity score matching has been already used in previous studies to assess the risk for migraine comorbidities [49–51] and the effect of migraine treatment on several outcomes [52]. However, in the present study, the matching variables only included age, length of CM history, and baseline headache frequency; matching for medical comorbidities could not be performed as those data were not included in our dataset. Data collection across centers was heterogeneous, resulting in a limited number of variables to consider for the present analysis. The present analysis was primarily designed to assess BT-A effectiveness; therefore, the assessment of gender differences could not be complete. Moreover, we could not collect data on BT-A safety except from BT-A discontinuation due to adverse events. However, BT-A has shown an excellent tolerability profile in the trials [15, 16] and in real-life studies [26–28, 30, 31, 53–56]. Lastly, our study is limited by its observational nature and lack of randomization, which may introduce biases we cannot adjust for.

Conclusions

BT-A is an effective treatment for CM prevention both in men and in women. We only found slight and probably unmeaningful differences in BT-A efficacy favoring women over men. On the other hand, adherence to treatment was a more important concern in men than in women. There is an unmet need for gender-specific data on migraine treatments which should be reported first in randomized controlled trials and then in observational studies.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Author Contributions

RO and SS conceived the study; RO performed the analyses and wrote the initial draft; all authors provided data for the analyses and contributed to the critical revision of the manuscript.

Disclosures

Raffaele Ornello reports speaker fees from Novartis and Eli Lilly, travel grants from Teva, and support for publication from Novartis and Allergan. Simona Sacco reports personal fees from Allergan-AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Abbott, Teva, Novartis, NovoNordisk, Medscape, Neurodiem, and Eli Lilly. Alicia Alpuente has received honoraria for educational projects from Allergan-Abbvie, Novartis and Teva. Patricia Pozo-Rosich has received honoraria as a consultant and speaker for Allergan-Abbvie, Almirall, Amgen, Biohaven, Chiesi, Eli Lilly, Medscape, Neurodiem, Novartis and Teva; her research group has received research grants from Allergan, and has received funding for clinical trials from Alder, Allergan-Abbvie, Electrocore, Eli Lilly, Novartis and Teva; she is a trustee member of the board of the International Headache Society, member of the Council of the European Headache Society; she is in the editorial board of Revista de Neurologia, associate editor for Cephalalgia, Headache, Neurologia, Frontiers of Neurology and advisor for The Journal of Headache and Pain; she is a member of the Clinical Trials Guidelines Committee of the International Headache Society; she has edited the Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Headache of the Spanish Neurological Society; she is the founder of www.midolordecabeza.org; she does not own stocks from any pharmaceutical company. Andrea Negro has received speaking honoraria and has served on the advisory boards of Allergan, Eli Lilly and Company and Novartis. Paolo Martelletti has received speaker’s honoraria and has served on the advisory boards of Allergan, Eli Lilly and Company, Novartis and Teva Pharmaceuticals; he is also an EMA Expert and has served as Editor in Chief for The Journal of Headache and Pain and as Editor in Chief for Springer Nature Comprehensive Clinical Medicine; he also declares received royalties from Springer Nature. Massimo Filippi is Editor-in-Chief of the Journal of Neurology and Associate Editor of Neurological Sciences, received compensation for consulting services and/or speaking activities from Bayer, Biogen Idec, Merck‐Serono, Novartis, Roche, Sanofi Genzyme, Takeda, and Teva Pharmaceutical Industries; and receives research support from Biogen Idec, Merck‐Serono, Novartis, Teva Pharmaceutical Industries, Roche, Italian Ministry of Health, Fondazione Italiana Sclerosi Multipla, and ARiSLA (Fondazione Italiana di Ricerca per la SLA). Elena Filatova reports speaker fees from Novartis and Teva. Nina Latysheva reports speaker fees from Novartis and Allergan. Carlo Baraldi received travel grants and honorary from Allergan, Novartis, Teva and Ely Lilly. Licia Grazzi has received consultancy and advisory fees from Allergan, Electrocore LLC, Novartis, and Eli Lilly, and collaborates in trials sponsored by Eli Lilly, Teva, and PharmInd. Simona Guerzoni received travel grants and honorary from Allergan, Eli Lilly, TEVA and Novartis. Sabina Cevoli received honoraria as speaker, for participating in advisory boards or for clinical investigation studies from Teva, Allergan, Novartis, Lilly, Ibsa. Fayyaz Ahmed has received honorarium from Allergan for being on their advisory board and is paid to the charitable organisations. Giorgio Lambru has received speaker honoraria, funding for travel and has received honoraria for participation in advisory boards sponsored by Allergan, Novartis, Eli Lilly and TEVA; he has also received speaker honoraria, funding for travel from electroCore, Nevro Corp. and Autonomic Technologies. Anna P. Andreou received speaker honoraria and funding for travel from Allergan, Eli Lilly and eNeura, honoraria for participation in advisory boards sponsored by Allergan and Eli Lilly, sponsorship for educational purposes from eNeura, Allergan, Autonomic Technologies and Novartis, and an equipment grant from eNeura. Antonio Russo has received speaker honoraria from Allergan, Lilly, Novartis and Teva and serves as an associate editor of Frontiers in Neurology (Headache Medicine and Facial Pain session). Marcello Silvestro has received speaker honoraria from Lilly, Novartis and Teva. Ruth Ruscheweyh has received travel grants and/or honoraria from Allergan, Hormosan, Lilly Novartis and Teva. Fabrizio Vernieri received travel grants, honoraria for advisory boards and speaker panels from Allergan, Angelini, Lilly, Novartis, and Teva. Marcin Straburzynski received personal fees from Novartis and Teva. Katharina Kamm received travel grants and/ or honoraria from Lilly, Novartis and Teva. Paola Torelli has received travel grants and/or honoraria from Allergan, Lilly, Novartis and Teva. Anna Gryglas-Dwora has received honoraria as a speaker and travel grants from Allergan and honoraria as a speaker from Novartis. Anna Maria Miscio, Antonio Santoro Nicoletta Brunelli, Calogera Butera and Bruno Colombo and Marco Russo have nothing to disclose.

Prior Presentation

The study was accepted as oral presentation for the 2021 International Headache Society/European Headache Federation Joint Congress (virtual, 8–10 September 2021).

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The present analysis was approved by the Internal Review Board of the University of L’Aquila with protocol number 23/2020. The approval was shared with all the participating centers. Patients did not have to sign an additional informed consent as no additional data were required for the present analyses. The study was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments.

Data Availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the participant centers upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Deuschl G, Beghi E, Fazekas F, et al. The burden of neurological diseases in Europe: an analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(10):e551–e567. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30190-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.GBD 2016 Headache Collaborators Global, regional, and national burden of migraine and tension-type headache, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(11):954–976. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30322-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vetvik KG, MacGregor EA. Sex differences in the epidemiology, clinical features, and pathophysiology of migraine. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16(1):76–87. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(16)30293-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scher AI, Wang SJ, Katsarava Z, et al. Epidemiology of migraine in men: results from the Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes (CaMEO) Study. Cephalalgia. 2019;39(2):296–305. doi: 10.1177/0333102418786266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delaruelle Z, Ivanova TA, Khan S, et al. Male and female sex hormones in primary headaches. J Headache Pain. 2018;19(1):117. doi: 10.1186/s10194-018-0922-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.MacGregor EA, Frith A, Ellis J, Aspinall L, Hackshaw A. Incidence of migraine relative to menstrual cycle phases of rising and falling estrogen. Neurology. 2006;67(12):2154–2158. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000233888.18228.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glaser R, Dimitrakakis C, Trimble N, Martin V. Testosterone pellet implants and migraine headaches: a pilot study. Maturitas. 2012;71(4):385–388. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shields LBE, Seifert T, Shelton BJ, Plato BM. Testosterone levels in men with chronic migraine. Neurol Int. 2019;11(2):8079. doi: 10.4081/ni.2019.8079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Labastida-Ramírez A, Rubio-Beltrán E, Villalón CM, MaassenVanDenBrink A. Gender aspects of CGRP in migraine. Cephalalgia. 2019;39(3):435–444. doi: 10.1177/0333102417739584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smitherman TA, Ward TN. Psychosocial factors of relevance to sex and gender studies in headache. Headache. 2011;51(6):923–931. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2011.01919.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schroeder RA, Brandes J, Buse DC, et al. Sex and gender differences in migraine-evaluating knowledge gaps. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2018;27(8):965–973. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2018.7274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Franconi F, Finocchi C, Allais G, et al. Gender and triptan efficacy: a pooled analysis of three double-blind, randomized, crossover, multicenter, Italian studies comparing frovatriptan vs. other triptans. Neurol Sci. 2014;35(Suppl 1):99–105. doi: 10.1007/s10072-014-1750-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Casteren DS, Kurth T, Danser AHJ, Terwindt GM, MaassenVanDenBrink A. Sex differences in response to triptans: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurology. 2021;96(4):162–170. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000011216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lipton RB, Munjal S, Buse DC, Fanning KM, Bennett A, Reed ML. Predicting inadequate response to acute migraine medication: results from the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) Study. Headache. 2016;56(10):1635–1648. doi: 10.1111/head.12941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aurora SK, Dodick DW, Turkel CC, et al. OnabotulinumtoxinA for treatment of chronic migraine: results from the double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase of the PREEMPT 1 trial. Cephalalgia. 2010;30(7):793–803. doi: 10.1177/0333102410364676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diener HC, Dodick DW, Aurora SK, et al. OnabotulinumtoxinA for treatment of chronic migraine: results from the double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase of the PREEMPT 2 trial. Cephalalgia. 2010;30(7):804–814. doi: 10.1177/0333102410364677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reuter U, Goadsby PJ, Lanteri-Minet M, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of erenumab in patients with episodic migraine in whom two-to-four previous preventive treatments were unsuccessful: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3b study. Lancet. 2018;392(10161):2280–2287. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32534-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferrari MD, Diener HC, Ning X, et al. Fremanezumab versus placebo for migraine prevention in patients with documented failure to up to four migraine preventive medication classes (FOCUS): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3b trial. Lancet. 2019;394(10203):1030–1040. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31946-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mulleners WM, Kim BK, Láinez MJA, et al. Safety and efficacy of galcanezumab in patients for whom previous migraine preventive medication from two to four categories had failed (CONQUER): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3b trial. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19(10):814–825. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30279-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robbins NM, Bernat JL. Minority representation in migraine treatment trials. Headache. 2017;57(3):525–533. doi: 10.1111/head.13018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aurora SK, Winner P, Freeman MC, et al. OnabotulinumtoxinA for treatment of chronic migraine: pooled analyses of the 56-week PREEMPT clinical program. Headache. 2011;51(9):1358–1373. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2011.01990.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aurora SK, Dodick DW, Diener HC, et al. OnabotulinumtoxinA for chronic migraine: efficacy, safety, and tolerability in patients who received all five treatment cycles in the PREEMPT clinical program. Acta Neurol Scand. 2014;129(1):61–70. doi: 10.1111/ane.12171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dodick DW, Turkel CC, DeGryse RE, et al. OnabotulinumtoxinA for treatment of chronic migraine: pooled results from the double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phases of the PREEMPT clinical program. Headache. 2010;50(6):921–936. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2010.01678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blumenfeld AM, Stark RJ, Freeman MC, Orejudos A, Manack AA. Long-term study of the efficacy and safety of onabotulinumtoxinA for the prevention of chronic migraine: COMPEL study. J Headache Pain. 2018;19(1):13. doi: 10.1186/s10194-018-0840-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ahmed F, Gaul C, García-Moncó JC, Sommer K, Martelletti P, REPOSE Principal Investigators An open-label prospective study of the real-life use of onabotulinumtoxinA for the treatment of chronic migraine: the REPOSE study. J Headache Pain. 2019;20(1):26. doi: 10.1186/s10194-019-0976-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Andreou AP, Trimboli M, Al-Kaisy A, et al. Prospective real-world analysis of onabotulinumtoxinA in chronic migraine post-National Institute for Health and Care Excellence UK technology appraisal. Eur J Neurol. 2018;25(8):1069–e83. doi: 10.1111/ene.13657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khalil M, Zafar HW, Quarshie V, Ahmed F. Prospective analysis of the use of onabotulinumtoxinA (BOTOX) in the treatment of chronic migraine; real-life data in 254 patients from Hull, UK. J Headache Pain. 2014;15:54. doi: 10.1186/1129-2377-15-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Negro A, Curto M, Lionetto L, Martelletti P. A two years open-label prospective study of onabotulinumtoxinA 195 U in medication overuse headache: a real-world experience. J Headache Pain. 2015;17:1. doi: 10.1186/s10194-016-0591-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guerzoni S, Pellesi L, Baraldi C, et al. Long-term treatment benefits and prolonged efficacy of onabotulinumtoxinA in patients affected by chronic migraine and medication overuse headache over 3 years of therapy. Front Neurol. 2017;8:586. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2017.00586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Domínguez C, Pozo-Rosich P, Torres-Ferrús M, et al. OnabotulinumtoxinA in chronic migraine: predictors of response. A prospective multicentre descriptive study. Eur J Neurol. 2018;25(2):411–6. doi: 10.1111/ene.13523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ornello R, Guerzoni S, Baraldi C, et al. Sustained response to onabotulinumtoxinA in patients with chronic migraine: real-life data. J Headache Pain. 2020;21(1):40. doi: 10.1186/s10194-020-01113-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alpuente A, Gallardo VJ, Torres-Ferrus M, Alvarez-Sabin J, Pozo-Rosich P. Early efficacy and late gain in chronic and high-frequency episodic migraine with onabotulinumtoxinA. Eur J Neurol. 2019;26(12):1464–70. doi: 10.1111/ene.14028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ornello R, Ahmed F, Negro A, et al. Early management of onabotulinumtoxinA treatment in chronic migraine: insights from a Real-Life European Multicenter Study. Pain Ther. 2021;10(1):637–50. doi: 10.1007/s40122-021-00253-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Silberstein SD, Dodick DW, Aurora SK, et al. Per cent of patients with chronic migraine who responded per onabotulinumtoxinA treatment cycle: PREEMPT. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2015;86(9):996–1001. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2013-307149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE). Botulinum toxin type A for the prevention of headaches in adults with chronic migraine. Technology appraisal guidance [TA260]. 2012. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta260. Accessed 20 June 2021.

- 36.Alpuente A, Gallardo VJ, Torres-Ferrús M, Álvarez-Sabin J, Pozo-Rosich P. Short and mid-term predictors of response to onabotulinumtoxinA: real-life experience observational study. Headache. 2020;60(4):677–85. doi: 10.1111/head.13765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yaldo AZ, Wertz DA, Rupnow MF, Quimbo RM. Persistence with migraine prophylactic treatment and acute migraine medication utilization in the managed care setting. Clin Ther. 2008;30(12):2452–60. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2008.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Khan K, Arain MI, Asghar MA, et al. Analysis of treatment cost and persistence among migraineurs: a two-year retrospective cohort study in Pakistan. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(3):e0248761. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0248761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sacco S, Ricci S, Degan D, Carolei A. Migraine in women: the role of hormones and their impact on vascular diseases. J Headache Pain. 2012;13(3):177–89. doi: 10.1007/s10194-012-0424-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ornello R, De Matteis E, Di Felice C, Caponnetto V, Pistoia F, Sacco S. Acute and preventive management of migraine during menstruation and menopause. J Clin Med. 2021;10(11):2263. doi: 10.3390/jcm10112263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ornello R, Caponnetto V, Frattale I, Sacco S. Patterns of migraine in postmenopausal women: a systematic review. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2021;17:859–71. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S285863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bereiter DA, Cioffi JL, Bereiter DF. Oestrogen receptor-immunoreactive neurons in the trigeminal sensory system of male and cycling female rats. Arch Oral Biol. 2005;50(11):971–9. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Warfvinge K, Krause DN, Maddahi A, Edvinsson JCA, Edvinsson L, Haanes KA. Estrogen receptors α, β and GPER in the CNS and trigeminal system—molecular and functional aspects. J Headache Pain. 2020;21(1):131. doi: 10.1186/s10194-020-01197-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Borsook D, Erpelding N, Lebel A, et al. Sex and the migraine brain. Neurobiol Dis. 2014;68:200–14. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2014.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Durham PL, Cady R. Regulation of calcitonin gene-related peptide secretion from trigeminal nerve cells by botulinum toxin type A: implications for migraine therapy. Headache. 2004;44(1):35–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2004.04007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Victor TW, Hu X, Campbell J, White RE, Buse DC, Lipton RB. Association between migraine, anxiety and depression. Cephalalgia. 2010;30(5):567–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2009.01944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lampl C, Thomas H, Tassorelli C, et al. Headache, depression and anxiety: associations in the Eurolight project. J Headache Pain. 2016;17:59. doi: 10.1186/s10194-016-0649-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schiano di Cola F, Caratozzolo S, Liberini P, Rao R, Padovani A. Response predictors in chronic migraine: medication overuse and depressive symptoms negatively impact onabotulinumtoxin-A treatment. Front Neurol. 2019;10:678. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2019.00678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Peng KP, Chen YT, Fuh JL, Tang CH, Wang SJ. Association between migraine and risk of venous thromboembolism: a nationwide cohort study. Headache. 2016;56(8):1290–9. doi: 10.1111/head.12885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Peng KP, Chen YT, Fuh JL, Tang CH, Wang SJ. Migraine and incidence of ischemic stroke: a nationwide population-based study. Cephalalgia. 2017;37(4):327–35. doi: 10.1177/0333102416642602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hoffman V, Xue F, Ezzy SM, et al. Risk of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events and mortality in patients with migraine receiving prophylactic treatments: an observational cohort study. Cephalalgia. 2019;39(12):1544–59. doi: 10.1177/0333102419856630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tepper SJ, Fang J, Zhou L, et al. Effectiveness of erenumab and onabotulinumtoxinA on acute medication usage and health care resource utilization as migraine prevention in the United States. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2021 doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2021.21060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Aicua-Rapun I, Martínez-Velasco E, Rojo A, et al. Real-life data in 115 chronic migraine patients treated with onabotulinumtoxinA during more than one year. J Headache Pain. 2016;17(1):112. doi: 10.1186/s10194-016-0702-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cernuda-Morollón E, Ramón C, Larrosa D, Alvarez R, Riesco N, Pascual J. Long-term experience with onabotulinumtoxinA in the treatment of chronic migraine: what happens after one year? Cephalalgia. 2015;35(10):864–8. doi: 10.1177/0333102414561873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kollewe K, Escher CM, Wulff DU, et al. Long-term treatment of chronic migraine with onabotulinumtoxinA: efficacy, quality of life and tolerability in a real-life setting. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2016;123(5):533–40. doi: 10.1007/s00702-016-1539-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Russo M, Manzoni GC, Taga A, et al. The use of onabotulinum toxin A (Botox(®)) in the treatment of chronic migraine at the Parma Headache Centre: a prospective observational study. Neurol Sci. 2016;37(7):1127–31. doi: 10.1007/s10072-016-2568-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the participant centers upon reasonable request.