Abstract

Objectives

To present a comprehensive real-world micro-costing analysis of bariatric surgery.

Methods

Patients were included if they underwent primary bariatric surgery (gastric banding [GB], gastric bypass [GBP] and sleeve gastrectomy [SG]) between 2013 and 2019. Costs were disaggregated into cost items and average-per-patient costs from the Australian healthcare systems perspective were expressed in constant 2019 Australian dollars for the entire cohort and subgroup analysis. Annual population-based costs were calculated to capture longitudinal trends. A generalized linear model (GLM) predicted the overall bariatric-related costs.

Results

N = 240 publicly funded patients were included, with the waitlist times of ≤ 10.7 years. The mean direct costs were $11,269. The operating theatre constituted the largest component of bariatric-related costs, followed by medical supplies, salaries, critical care use, and labour on-costs. Average cost for SG ($12,632) and GBP ($15,041) was higher than that for GB ($10,049). Operating theatre accounted for the largest component for SG/GBP costs, whilst medical supplies were the largest for GB. We observed an increase in SG and a decrease in GB procedures over time. Correspondingly, the main cost driver changed from medical supplies in 2014–2015 for GB procedures to operating theatre for SG thereafter. GLM model estimates of bariatric average cost ranged from $7,580 to $36,633.

Conclusions

We presented the first detailed characterization of the scale, disaggregated profile and determinants of bariatric-related costs, and examined the evolution of resource utilization patterns and costs, reflecting the shift in the Australian bariatric landscape over time. Understanding these patterns and forecasting of future changes are critical for efficient resource allocation.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10198-021-01405-x.

Keywords: Bariatric surgery, Cost bucket, Disaggregated data, Micro-costing analysis, Public healthcare system, Sleeve gastrectomy

Introduction

Obesity (body mass index [BMI] ≥ 30 kg/m2) is an escalating global epidemic and places a significant economic burden on healthcare systems [1, 2]. According to the latest (2017/2018) Australian estimates, 67.0% of Australian adults are overweight (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2) and 31.0% are obese, and these proportions increase each year [3]. Tasmania (an Australian island state of just over 500,000 people) recorded the highest prevalence of adult obesity (34.8%) and of overweight and obesity combined (70.9%) in 2017/18 (Supplemental Fig. 1) [4]. Being overweight or obese considerably raises the risk of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and many types of cancer [5]. These colliding health crises result in huge costs associated with obesity management and the reduction in health-related quality of life. According to the latest available data, the global economic impact of obesity was estimated to be US $2.0 trillion, approximately 2.8% of the global gross domestic product (GDP) [6].

Bariatric (weight loss) surgery was found to be the most clinically efficacious intervention that leads to considerable weight loss and health improvement [7–9]. Based on the analysis of a recent comprehensive systematic review, we found that bariatric surgery is a cost-saving treatment for patients with obesity over the lifetime particularly when indirect costs are included through a broader societal perspective [10]. Although many of the primary studies included in the review considered the total healthcare costs and medication utilization, other disaggregated medical cost components (also known as cost buckets in the Australian context) were less commonly reported [10]. There are only six publications outside Australia that consider the disaggregated components of bariatric surgery-related utilization and costs (Table 1) [11–16]. Within the Australian setting, the Australian Institute for Health and Welfare (AIHW) report and our previous pilot cost study only provided aggregated estimates for bariatric surgery episodes of care [17, 18]. The substantially high costs of bariatric surgery are recognized, but we have little knowledge of the scale, profile, or determinants of these costs in the Australian healthcare setting.

Table 1.

Published studies with specific bariatric-related cost components/buckets

| Author [ref] | Year | Country | Data source | Surgery type | Sample size | Currency | Cost category | Cost buckets |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weiner [12] | 2013 | USA | 7 BlueCross BlueShield health insurance plans | All types | 29,820 | 2005 USD | Healthcare costs in the operative period | aTotal $27,833: inpatient cost $26,814, professional office cost $160, pharmacy cost $76, outpatient and others $783 |

| Grenda [13] | 2015 | USA | National Medicare claims database | All types | 24,647 | USD | Post-surgery average payment | bpayments to hospitals $9,043, payments to physicians $2,614, post-acute care services $365 |

| Gounder [14] | 2016 | New Zealand | Monthly Index of Medical Specialties | Laparoscopic SG, laparoscopic RYGB | 114 | 2014 New Zealand Dollars | Hospital costs (including bariatric surgery costs) | LSG $9,131: theatre $3,041, surgeon $1,518, anaesthetist $1,614, ward doctor $583; ward $1,619; pharmacy $222; other $534. LRYGB $12,456: theatre $4,707, surgeon $2,351, anaesthetist $2,338, ward doctor $562; ward $1,580; pharmacy $242; other $676 |

| Banerjee [15] | 2017 | USA | Electronic medical record data | RYGB | 15 | USD | Hospital costs (including 1-year post-surgery costs) | Total $38,815: inpatient $25,355, outpatient $13,460, primary care costs $881, specialty care $10,267, pharmacy $1,083, emergency room $339, and other outpatient costs $889 |

| Zubiaurre [16] | 2017 | Brazil | Interview conducted during medical visits | Laparotomy RYGB | 140 | 2015 international dollars | One-year post-surgery healthcare costs and loss of productivity | c Direct medical costs Int $3,759, direct non-medical costs Int $736, indirect costs Int $1,172 |

| Smith [17] | 2019 | USA | Electronic health record of the US Department of Veterans Affairs | All types | 2498 | 2016 USD | Six months post-surgery healthcare costs | Total $6671: outpatient $3691, inpatients $2612, outpatient pharmacy $639 |

aInpatient costs include both institution and professional fees for services provided on an inpatient basis. Professional office costs include all ambulatory services billed by physicians and other independent professionals. Outpatient and other costs include services billed by outpatient departments of hospitals and all other types of ambulatory service providers (e.g. laboratories)

bPayments to hospitals related to the index hospitalization (DRG payments plus outlier payments, if applicable) and readmissions occurring within 30 days of discharge. Payments to physicians categorized according to the service (i.e. surgery, anaesthesia, imaging, and laboratory) provided. Payments related to post-acute care services using Medicare claims for outpatient and home health care

cDirect medical costs included visits with physicians and other healthcare professionals, laboratory and imaging tests, procedures, surgeries, and medications. Direct non-medical costs included transportation, special and dietetic foods, and home caregivers. Indirect costs were estimated based on the work hours/days missed (absenteeism), sick leaves, and early retirement due to obesity or its complications

Both aggregated and disaggregated forms of cost data are essential for understanding the resource allocation and associated budgetary implications of the public healthcare system. Whilst aggregate-data reports are generally limited to the identification of broader trends and patterns in healthcare, disaggregated (micro-level) data are more useful for diagnosing deeper underlying problems such as disparities in healthcare needs and surgical procedural performance among different patient groups, and to identify areas to target improvement in quality and cost-efficiency [19]. A lack of detail or underestimation of costs at the micro-level may result in a flawed cost-effectiveness analysis with considerable policy and healthcare resourcing implications.

Continuing on from our previous National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) partnership project regarding the aggregated costs for patients receiving bariatric surgery (for Australian fiscal years 2007/2008 to 2015/2016) [18], this study aimed to provide the first detailed characterization of the scale, disaggregated profile, and determinants of healthcare costs associated with primary bariatric surgery for the fiscal years 2013/14 to 2018/19 in an Australian publicly funded hospital setting.

Materials and methods

This study was conducted in accordance with the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) checklist [20], and the CHEERS (Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards) statement [21]. Ethics approvals were granted by the University of Tasmania’s Health and Medical Human Research Ethics Committee (approval number H0018235).

Study design and data sources

We conducted a retrospective cohort study identifying N = 254 publicly funded patients who underwent primary bariatric surgery for obesity between the Australian fiscal years of 1st July 2013 to 30th June 2019 from the Tasmanian Department of Health’s (DoH) administrative databases. Fourteen patients’ cost data were not available, which reduced the total number of patients included in the primary analyses to n = 240. All 14 excluded patients underwent GB without postoperative complications and CCU support, but did not differ on other demographic and clinical characteristics when compared with included patients.

The Tasmanian public hospital system is governed by an agreement between Commonwealth and State Governments [22, 23]. Costing is undertaken within a set of costing standards as part of the Australian National Health Reform Agreement [23]. The States manage costing and agree to provide costing that meets these nationally agreed standards [24]. Under the auspices of this resourcing and cost arrangement between the Commonwealth and the States, the Tasmanian DoH provided de-identified patient-level data from: (a) a patient administration system (Information Patient Management —IPM); (b) a costing system (User Cost) and (c) coded admitted patient data. Clinical coding of patient data was carried out in accordance with the International Classification of Diseases and related health problems 10th Revision Australian Modification (ICD-10-AM) with procedure codes applied in accordance with the Australian Classification of Health Interventions (ACHI) [25]. Diagnostic and procedure codes, socio-demographic, clinical, cost and other healthcare utilization data were also obtained from the IPM.

Patients’ socio-demographic and clinical characteristics

Patients’ socio-demographic and clinical characteristics were extracted from the administrative database including age at surgery, gender, preoperative BMI, indigenous status (Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander origin: yes or no), history of smoking (yes or no), the types and number of obesity-related comorbidities (0, 1 or ≥ 2), type of surgery (gastric banding [GB], gastric bypass [GBP] and sleeve gastrectomy [SG]), operating theatre time (in minutes), critical care unit (CCU) admission frequency (none, once or twice admission within the same patient episode of care), total hospital length of stay (LoS; in days), and peri-/postoperative complications (none, clinical related or surgery related).

Cost analyses

We performed a descriptive micro-costing analysis to identify direct, discounted, and disaggregated costs for bariatric surgery episodes of care. Disaggregated costs are episode costs reported into their component costs or cost buckets. The details regarding the costing methodology were described in our previous study [18] and are described briefly here. A bottom-up costing approach for resource use was adopted. Cost data were inflated to constant 2019 Australian dollars (AU$) using the General Final Consumption Expenditure (GFCE) on Hospitals and Nursing Homes inflator (Supplemental Table 1). For comparisons, we also converted Australian dollars to US dollars (AU$ to US$) by using the Campbell–Cochrane Converter based on the IMF GDP deflator [26]. All costs were expressed as mean costs with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Australian Hospital Patient Costing Standards (Version 3.1) were used to code the cost buckets [27]. Supplemental Fig. 2 provides an overview of the cost buckets considered in public hospitals across Australia. Overall, 14 cost buckets were considered, namely: (1) operating theatre, (2) prostheses (surgically implanted devices), (3) ward supplies, (4) ward medical, (5) ward nursing, (6) allied health services, (7) labour (staff) on-costs, (8) critical care areas, (9) pharmacy, (10) pathology, (11) imaging, (12) non-clinical costs, (13) hotel services, and (14) depreciation costs.

Subgroup analyses by surgery type (GB, GBP and SG) and CCU utilization (yes/no) were also performed. Between-surgery type comparisons were performed using Mann–Whitney U test [28]. Annual population-based costs were calculated to capture trends over time. Besides, we also imputed the costs of 14 excluded patients based on the costs from (n = 118) included patients with similar clinical profiles (Supplemental Table 2).

Regression analysis to predict total medical costs

We developed a multivariable linear regression model to predict total per person medical costs for patients undergoing bariatric surgery, and used this model’s estimates to predict costs for a hypothetical cohort of Australian bariatric surgery patients (i.e.: females aged 46–54 years and having a BMI of ≤ 50) by CCU utilization and the absence or presence of complications. Total cost per patient was estimated by using the following formula:

Given the non-negative and right-skewed nature of total costs (Supplemental Fig. 3), we used a generalized linear model (GLM) with a log-link function and Gamma distribution to model bariatric surgery-related costs. Model specification was confirmed by the Modified Park test which indicated that cost data followed a gamma distribution (Gamma: χ2 = 0.17, P = 0.68) [29].

All tests were two-tailed and P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses and graphing were performed using STATA 16.0 and Microsoft Excel software.

Results

Patient eligibility and characteristics

Table 2 presents the baseline patient characteristics. The included patients were predominantly female (72.1%), with mean age 44.8 ± 11.8 years and mean BMI 49.1 ± 7.3 kg/m2. The mean waiting time for surgery was 3.1 ± 2.9 years with the maximum waiting time of 10.7 years. GB (56.3%, n = 135) was the most frequently conducted procedure, followed by SG (40.0%, n = 96) and GBP (3.7%, n = 9). The use of SG increased over the study period (from 10% in 2014–2015 to 56% in 2018–2019), while the use of the GB surgical procedure diminished (from 90% in 2014–2015 to 25% in 2018–2019) (Supplemental Fig. 4). A total of 44 patients (18.3%) were admitted to CCU. The proportion of patients requiring CCU services were highest in those undergoing SG (26.0%), followed by GBP (22.2%) and GB (12.6%), see Supplemental Fig. 5a).

Table 2.

Socio-demographics and clinical features of patients undergoing bariatric surgery

| Variables | N = 240 |

|---|---|

| Age at surgery, years | |

| Mean ± SD | 44.8 ± 11.8 |

| Median (IQR) | 46.0 (36.0, 54.0) |

| Min, Max | (18.0, 70.0) |

| Gender, % | |

| Females | 173 (72.1%) |

| Males | 67 (27.9%) |

| Indigenous origin, % | |

| Yes | 30 (12.5%) |

| No | 210 (87.5%) |

| BMI at surgery, kg/m2 | |

| Mean ± SD | 49.1 ± 7.3 |

| Median (IQR) | 50.0 (45.0, 51.1) |

| Min, Max | (33.0, 75.1) |

| Smoking history, % | |

| Yes | 46 (19.2%) |

| No | 194 (80.8%) |

| Surgery type, % | |

| GB | 135 (56.3%) |

| SG | 96 (40.0%) |

| GBP | 9 (3.7%) |

| Waiting time for surgery, year | |

| Mean ± SD | 3.1 ± 2.9 |

| Median (IQR) | 1.4 (0.6, 5.9) |

| Min, max | (0.02, 10.7) |

| Operation time, min | |

| Mean ± SD | 100.2 ± 50.1 |

| Median (IQR) | 80.5 (69.0, 123.5) |

| Min, Max | (28.0, 502.0) |

| CCU admission frequency, % | |

| No admission | 196 (81.7%) |

| Once admission | 34 (14.2%) |

| Twice admission | 10 (4.1%) |

| Hospital length of stay, days | |

| Mean ± SD | 2.6 ± 3.3 |

| Median (IQR) | 2.0 (1.0, 3.0) |

| Min, Max | (1.0, 45.0) |

| Number of comorbidities | |

| 0 | 78 (32.5%) |

| 1 | 68 (28.3%) |

| ≥ 2 | 94 (39.2%) |

| Complications | |

| None | 198 (82.5%) |

| Clinical related | 29 (12.1%) |

| Surgical related | 13 (5.4%) |

BMI body mass index; CCU critical care unit; GB gastric banding; GBP gastric bypass; IQR interquartile range; SD standard deviation; SG sleeve gastrectomy

In regard to comorbidity load, 32.5% patients did not have reported preoperative comorbidities, whilst 28.3% had one comorbidity and 39.2% had ≥ 2 comorbidities. Individual comorbidities and their combinations are shown in Supplemental Table 3. The proportion of patients suffering from peri/postoperative clinical and surgical complications was 12.1% and 5.4%, respectively. Preoperative comorbidities and postoperative complications were positively associated with CCU use (Supplemental Fig. 5b, c).

Aggregated and disaggregated medical costs of bariatric surgery (the overall sample)

Table 3 shows the aggregated and disaggregated costs for n = 240 included patients who received primary bariatric surgery. Overall, the mean direct hospital costs for all three surgery types were $11,269 (US$7,799) per person. By imputing the costs for 14 excluded patients, the overall mean cost became $11,099 (US$7,681) (Supplemental Table 4).

Table 3.

Direct medical cost buckets per person (in 2019 AU$), overall and by surgery type

| Cost bucket | Total cohort (n = 240) | GB (n = 135) | SG (n = 96) | GBP (n = 9) | P value* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GB vs. SG | GB vs. GBP | SG vs. GBP | |||||

| Operation theatres | 4,702 (4,336, 5,069) | 2,848 (2,580, 3,117) | 6,875 (6,397, 7,352) | 9,343 (8,431, 10,255) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Medical supplies | 2,465 (2,141, 2,789) | 4,103 (3,707, 4,499) | 365 (319, 411) | 297 (259, 336) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.954 |

| Prostheses | 1,688 (1,496, 1,881) | 3,002 (2,936, 3,067) | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | NA |

| Ward supplies | 777 (549, 1,005) | 1,101 (705, 1,498) | 365 (319, 411) | 297 (259, 336) | < 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.954 |

| Salaries or wages | 1,682 (1,396, 1,969) | 1,408 (945, 1,872) | 2,060 (1,777, 2,343) | 1,756 (1,566, 1,946) | < 0.001 | 0.005 | 0.410 |

| Ward medical | 741 (622, 860) | 700 (550, 851) | 822 (613, 1,031) | 478 (457, 500) | 0.022 | 0.052 | 0.017 |

| Ward nursing | 833 (675, 990) | 566 (314, 818) | 1,170 (1,027, 1,314) | 1,234 (1,038, 1,431) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.184 |

| Allied health services | 109 (60, 157) | 142 (60, 224) | 68 (29, 106) | 44 (5, 83) | < 0.001 | 0.015 | 0.891 |

| Labour on-costs | 663 (578, 748) | 378 (262, 493) | 1,020 (932, 1,108) | 1,138 (928, 1,348) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.122 |

| Critical care | 670 (444, 895) | 422 (196, 648) | 992 (547, 1,437) | 947 (0, 2,233) | 0.008 | 0.358 | 0.899 |

| Pharmacy | 105 (75, 134) | 84 (33, 135) | 133 (114, 151) | 113 (80, 146) | < 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.697 |

| Pathology | 189 (138, 239) | 161 (77, 246) | 219 (176, 261) | 279 (194, 364) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.094 |

| Imaging | 49 (30, 68) | 52 (29, 76) | 37 (8, 67) | 124 (0, 336) | 0.140 | 0.549 | 0.277 |

| Non-Clinical costs | 320 (268, 373) | 299 (209, 389) | 352 (317, 387) | 305 (281, 330) | < 0.001 | 0.011 | 0.740 |

| Hotel services | 141 (121, 161) | 76 (47, 105) | 216 (200, 231) | 312 (254, 369) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Depreciation costs | 284 (247, 321) | 217 (157, 278) | 364 (337, 391) | 427 (334, 521) | < 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.074 |

| Overall | 11,269 (10,383, 12,155) | 10,049 (8,694, 11,404) | 12,632 (11,607, 13,656) | 15,041 (13,204, 16,878) | < 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.02 |

GB gastric banding; GBP gastric bypass; NA no applicable; SG sleeve gastrectomy

All costs were expressed as mean costs with 95% confidence intervals

*Between-surgery type comparisons were performed using Mann–Whitney U test

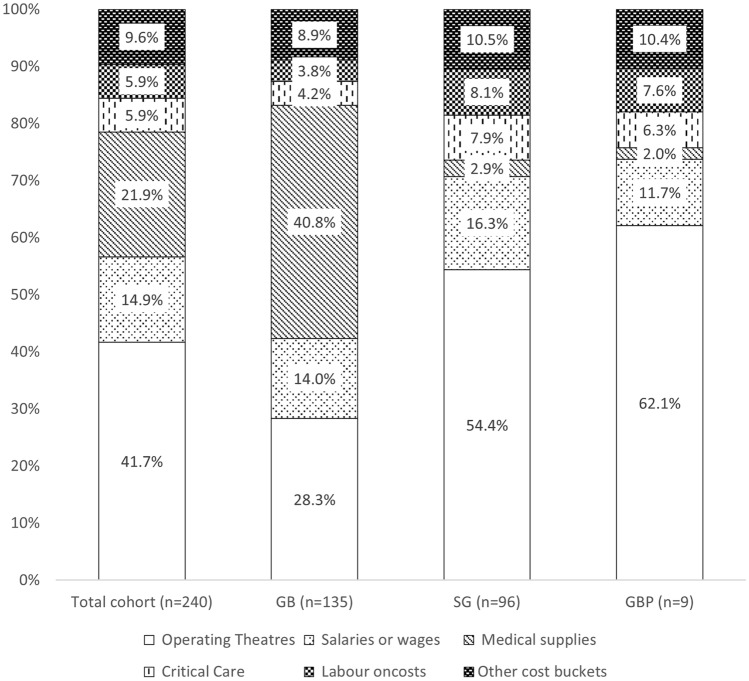

Figure 1 shows the proportional contribution of each cost bucket to the total costs for bariatric surgery. Of the 14 disaggregated cost buckets, the operating theatre cost bucket constituted the largest component of bariatric-related average cost (41.7%, $4,702), followed by medical supplies (21.9%, $2,465), and salaries (4.9%, $4,702). Costs for CCU services and labour staff on-costs each accounted for 5.9% of average costs. Other cost buckets jointly accounted for 9.6% of average costs, and the breakdown of these are shown in Supplemental Fig. 6. The proportional contribution of each cost bucket to the total costs did not materially alter after we conducted further analysis by imputing the costs for 14 excluded patients, and operating theatre remained the main costs driver in the total cohort (Supplemental Table 4).

Fig. 1.

Proportion of cost buckets of bariatric surgery, overall and by surgery type

Subgroup analyses of medical costs of bariatric surgery

Table 3 shows the aggregated and disaggregated costs stratified by surgery type. The average cost for SG ($12,632) and GBP ($15,041) was significantly higher than that for GB ($10,049 [$9,874 when including 14 excluded patients]) (P < 0.001 for both). As shown in Fig. 1, the proportion of operating theatre costs was much higher for SG (54.4%) and GBP (62.1%) than GB (28.3%), which could be explained by the greater operating theatre time for SG and GBP procedures (Supplemental Fig. 7). Surgically implanted prostheses were the specific supplies to patients undergoing GB (29.9%); additionally, the proportion of costs for ward supplies was also higher in GB (11.0%), resulting in the increased contribution for medical supplies from GB (40.8%) than that from SG (2.9%) and GBP (2.0%). The proportion of costs for CCU services was slightly lower in GB (4.2%) than that in SG (7.9%) and GBP (6.3%) procedures. Cost was similar amongst these three procedures in terms of the remaining cost buckets (Fig. 1 and Supplemental Fig. 5).

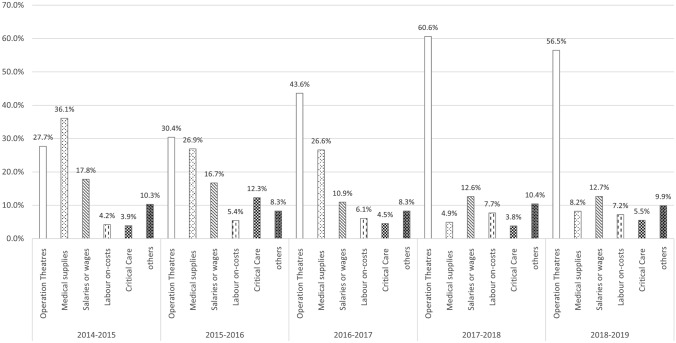

Figure 2 suggests that the distribution of bariatric-related cost buckets has shifted over time from GB-driven medical supplies’ costs to SG/GBP-driven operating theatre costs, reflecting the shift in the prevalence of surgery type over time.

Fig. 2.

Distribution of bariatric surgery-related costs over time

The aggregated and disaggregated costs stratified by CCU utilization type are reported in Supplemental Table 5. The average costs for the CCU group ($20,026) were higher than those for the non-CCU group ($9303), especially for patients who were admitted to CCU twice during the same patient episode ($24,476). For the CCU group, critical care cost accounted for 18.2% of the average cost. The proportion of costs for prostheses and ward supplies was much higher in non-CCU group (27.7%) than that in the CCU group (10.0%), which reflected the higher proportion of GB procedures conducted in the non-CCU group (Supplemental Fig. 5a). Costs were similar among these two groups in terms of the remaining cost buckets.

GLM to predict total medical costs for bariatric surgery

The estimates from our GLM regression model suggested that CCU utilization was associated with substantially higher medical costs. Additionally, SG and GBP surgery types, number of comorbidities and the presence of complications were also associated with higher medical costs (Supplemental Table 6). The total costs for selected groups of female patients aged 46–54 years with BMI ≤ 50 kg/m2 ranged from $7,580 to $23,787 for GB, from 8,792 to 27,593 for SG, and from 11,673 to 36,633 for GBP (Table 4).

Table 4.

Predicted total per person costs of bariatric surgery corresponding to females with a BMI ≤ 50 and age ranged from 46 to 54 yearsa

| None CCU admission | Once CCU admission | Twice CCU admission | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No comorbidity | 1 comorbidity | ≥ 2 comorbidities | No comorbidity | 1 comorbidity | ≥ 2 comorbidities | No comorbidity | 1 comorbidity | ≥ 2 comorbidities | |

| No complications | |||||||||

| GB | 7580 | 8262 | 9323 | 12,582 | 13,715 | 18,387 | 14,325 | 15,615 | 17,620 |

| SG | 8792 | 10,199 | 13,540 | 14,595 | 15,909 | 17,952 | 16,618 | 18,113 | 20,440 |

| GBP | 11,673 | 12,723 | 14,357 | 19,376 | 21,120 | 23,833 | 22,061 | 24,047 | 27,135 |

| None CCU admission | Once CCU admission | Twice CCU admission | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No comorbidity | 1 comorbidity | ≥ 2 comorbidities | No comorbidity | 1 comorbidity | ≥ 2 comorbidities | No comorbidity | 1 comorbidity | ≥ 2 comorbidities | |

| Clinical related complications | |||||||||

| GB | 8034 | 8757 | 9882 | 13,337 | 14,537 | 16,405 | 15,185 | 16,552 | 18,678 |

| SG | 9320 | 10,159 | 11,463 | 15,471 | 16,863 | 19,029 | 17,615 | 19,200 | 21,666 |

| GBP | 12,373 | 13,487 | 15,219 | 20,539 | 22,388 | 25,263 | 23,385 | 25,489 | 28,763 |

| None CCU admission | Once CCU admission | Twice CCU admission | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No comorbidity | 1 comorbidity | ≥ 2 comorbidities | No comorbidity | 1 comorbidity | ≥ 2 comorbidities | No comorbidity | 1 comorbidity | ≥ 2 comorbidities | |

| Surgical related complications | |||||||||

| GB | 10,232 | 11,153 | 12,586 | 16,986 | 18,515 | 20,893 | 19,339 | 21,080 | 23,787 |

| SG | 11,870 | 12,938 | 14,600 | 19,704 | 21,477 | 24,235 | 22,434 | 24,453 | 27,593 |

| GBP | 15,758 | 17,176 | 19,382 | 26,158 | 28,512 | 32,175 | 29,783 | 32,463 | 36,633 |

aOverall, the average cost for the hypothetical cohort ranged from $7,580 to $36,633

CCU critical care unit; GB gastric banding; GBP gastric bypass; SG sleeve gastrectomy

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive micro-costing study for bariatric surgery in the public hospital system in Australia. We used the latest available data to generate the estimates of direct medical costs associated with primary bariatric surgery in an Australian public hospital setting. Importantly, in addition to updating the aggregated costs of bariatric surgery from our previous pilot study [18], this study complements the previous findings regarding the disaggregated bariatric-related costs and their contributions over time, concluding that resource utilization patterns and costs for bariatric are changing, which is as expected from the changing incidence of surgery type in Australia over time.

We found that the bariatric surgery-related costs were largely driven by costs from operating theatres and medical supplies (63.6% of $11,269). More specifically, the proportion of operating theatre costs was, as expected, given the longer operation times, higher in SG and GBP than in GB. On the other hand, as expected given the costs of the GB appliance, medical (prostheses and ward) supplies were higher for GB procedures. We observed an increase in SG and a decrease in GB procedures over time; correspondingly, the main cost driver changed from medical supplies in 2014–2015 for GB procedures to operating theatre after 2014–2015 for SG procedures.

The disaggregated costs of bariatric surgery in Australia

Whilst many previous cost and cost analyses studies reported only aggregated costs or examined specific bariatric surgery-related cost categories or prescription drug costs and utilization, the detailed and systematic examination of disaggregated costs for the entire cohort and by subgroup has largely been neglected in Australia and worldwide. In this micro-costing study, we found that the operating theatre accounted for the largest proportion of the costs for SG or GBP patients, while the medical supplies (mainly related to the banding appliance) accounted for the largest part of the costs for GB patients. These are in line with previous findings. For instance, in an RCT study of the GB procedure in an Australian private hospital, GB prosthesis and supplies accounted for 36.7% of the total costs [30]. In another RCT study of SG and RYGB procedures in New Zealand, around 40% of total costs related to these procedures were related to operating theatre costs [13].

Furthermore, our study observed an increase in SG and a decrease in GB procedures over time, which corresponds to the nationally representative trend of bariatric procedure evolution identified through a larger Bariatric Surgery Registry annually reported by Monash University [31–33]. Corresponding to the shift in the bariatric surgery landscape over time, we captured the changes of the resource utilization and cost patterns (from GB-driven medical supplies costs to SG-driven operating theatre costs). Understanding these patterns and forecasting for future changes (as surgical techniques continue to improve) are critical for healthcare resource allocation and sustainable healthcare budgetary planning particularly with ever-increasing public hospital waiting lists. To illustrate, with the improvement of laparoscopic technology and even robotics [34], we expect a higher efficacy of SG or GBP procedures in Australia that may lead to significant cost savings due to time savings in the operating theatre. Currently, almost 10% of Australia’s bariatric surgical procedures are GB, which is in line with proportions of GB in other countries, particularly those from Europe (Supplemental Table 7). While a decrease in the proportion of GB procedure in Australia is likely to continue over time, there remains a place for GB to be the subject of bariatric surgery-related research worldwide [35, 36].

Salaries, labour on-costs and CCU utilization costs were the other major drivers of bariatric surgery-related expenditure. Furthermore, salaries and labour on-costs were found to be much higher in patients who required CCU services. This finding also reflected the positive relationship between healthcare utilization and bariatric surgery-related costs. Consistent with previous studies [11, 14, 37], our study found that non-surgery costs (e.g. medication fees) only explained a small proportion of bariatric surgery-related costs.

There is increasing pressure to provide more bariatric surgery places in the public hospital sector in Australia and worldwide due to the high demand of surgery for mitigating the obesity pandemic. It is therefore important that researchers continue to monitor the cost components in larger cohorts to better understand the resource use and efficacy of bariatric surgery.

The aggregated costs of bariatric surgery nationally and internationally

This study also provides the updated aggregated costs of bariatric surgery based on the latest Australian data. We found that the latest costs for GB ($10,049) and SG ($12,632) were similar while slightly lower than these in Australian fiscal years 2007/08 to 2015/16 (GB: $14,622 and SG: $15,014) [18]. This can be explained by the consideration of surgical sequelae (including secondary surgery) for GB patients in our previous study, which accounted for a mean cost of $6,267. Further to this, obese patients with different conditions tend to require alternative sets of healthcare services after bariatric surgery, which may explain part of these cost differences. This was also reflected in the AIHW’s report which estimated the average costs for ten of the most common Australian Refined Diagnosis Related Groups (AR-DRGs) for weight loss surgery separations, ranging from $2,180 to $34,407 [17]. In this study, we used a GLM model to predict the average costs for different cohorts of bariatric patients based on their demographic and other characteristics, and healthcare utilization. Even though surgical sequelae were not considered in this study, we found that comorbidities, complications, surgery type and CCU utilization were important determinants of direct medical costs. Importantly, these cost estimates could be used as the input parameters for future health economic modelling regarding bariatric surgery to ensure an efficient healthcare resource allocation and sustainable budgetary planning.

As mentioned in the recent systematic review of published procedural costs of bariatric surgery [38], bariatric surgery-related aggregated costs are well reported in other jurisdictions including the USA and some parts of Europe. The medical costs of bariatric surgery ranged from US$8,160 (AU$12,505 in 2019) to US$33,541 (AU$51,400 in 2019) in 2016 US dollars, with an overall average of US$16,993 (AU$26,041 in 2019). The figures for European countries ranged from US$8,244 (AU$12,634 in 2019) to US$17,751 (AU$27,203 in 2019) in 2016 currency, with an overall average of US$13,875 (AU$21,263 in 2019). Australian per person costs of bariatric surgery were lower than those in the US and Europe. Higher bariatric procedure costs in the US and Europe were as expected due to the dominance of SG and GBP procedures in these jurisdictions than in Australia, and the differing healthcare systems [39, 40]. Whilst our findings show a significant inter-country and inter-regional difference in bariatric surgery costs, the estimates from different studies and jurisdictions with alternative study periods, samples, availability/use/price of services, surgery type distributions, CCU admission criteria, healthcare systems and other factors must be compared with caution. For instance, comparisons with the US data are likely to be less meaningful, as the contrasting bariatric surgery landscape and non-single payer system in the US complicate the comparison.

The need to address prolonged wait times for bariatric surgery

We observed that wait time for bariatric surgery-eligible Tasmanians is currently up to 10.7 years and increasing. This dilemma has been echoed in other countries and highlighted in previous research [41, 42]. In most countries, patients with morbid obesity endure long waitlist times before they are provided with publicly funded bariatric surgery [43]. Bariatric surgery wait times (from 445 days to 5 years) in Canada were longest of any surgically treated health condition [44]. Government’s perceived high costs of bariatric surgery procedures, coupled with patients’ features (e.g. age, sex, BMI, comorbidity history) and operational factors (e.g. restrictive policies with burdensome preoperative requirements) are reported to be associated with increased bariatric surgery wait times [45, 46], which may substantially reduce obese patients’ health outcomes (e.g. life years and or HRQoL) [10]. Nevertheless, the important point here is that bariatric surgery is a cost-saving procedure over the life course, particularly when both direct and indirect costs are considered and this should be reflected in public policy decision making regarding the number of surgical places for bariatric surgery in public hospital systems [10]. More specifically, bariatric surgery supply (particularly in public healthcare systems) is not meeting the demand for bariatric surgery, especially given the projected increases in severe and morbid obesity [10, 47]. We acknowledge that the provision of elective surgeries is extremely challenging during COVID-19. However, as prompt surgery has been shown to be less expensive and more effective than all the strategies that delayed the provision of bariatric surgery [48, 49], policy strategies (e.g. increased insurance coverage,and the elimination of restrictive policies with burdensome preoperative requirements) to relieve the long waitlist in public healthcare system are mandated, particularly in the post-COVID-19 world.

Strength and limitations

We acknowledge that our study is subject to some weaknesses. First, our study was based on a small sample of patients from the public healthcare sector. However, our micro-costing approach has provided much needed information for policymakers to ensure efficient allocation of scarce public healthcare resources and sustainable budgetary planning, particularly for smaller regional jurisdictions such as Tasmania. Second, the exclusion of 14 patients may have impacted on the mean cost estimates; however, our sensitivity analysis showed that the influence is likely to be minor. Finally, as our analysis is based on data from public healthcare sector only, the generalisability of our findings to the private healthcare sector may be limited.

Despite the existing limitations, our study is first to investigate the scale, profile, and determinants of bariatric surgery-related costs and their evolution in Australia. We found that the bariatric surgery changes in Tasmania reflect the national surgical trend. The analyses were conducted using data from the latest available period of 2013–2019 based on national costing standards. Importantly, the disaggregated data of this study adds further contextualised evidence to our previous pilot cost study regarding the aggregated costs of bariatric surgery from 2007/08 to 2015/16. Our micro-costing approach provides precise estimates of the true bariatric-related costs to the healthcare system due to its reliance on the actual resource use and unit costs of those resources. Our estimates overcome the bias associated with gross-costing estimation techniques [50], and provide transparent and robust cost inputs for future bariatric surgery-related health economic evaluations, allowing adjustments to cost inputs to account for the contextual differences.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the disaggregated costs (cost buckets) of bariatric surgery in Australia and to examine how the cost and resource utilization patterns are evolving within an Australian public hospital setting. Patterns of resource utilization and costs for bariatric surgery in Australia are changing as the incidence of surgery type changes. Our micro-costing approach provides precise cost inputs that can be used in future health economic evaluations of bariatric surgery to facilitate decision making in alternative contextual settings, and has the potential to support health policymakers in budgeting for future bariatric expenditure in the public health system. We regard our study as a national alternative to complement the previous findings about the disaggregated costs of bariatric surgery using a detailed micro-costing approach. We however recommend future multi-centre studies of larger sample sizes to validate our results.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Tasmanian Department of Health for supporting the project.

Author contributions

Conceptualization and supervision: AP, JC, BdG and LS. Material preparation and data collection: KR, JT, JM, MH, BH, MG, JC and QX. Formal analysis and investigation: AP, JC, BdG, LS, HA, PO and QX. The first draft of the manuscript was written by JC, BdG, HA, PO and QX, and all co-authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

None.

Data availability

All data supporting this study are provided in the results section of this paper and as supplementary information accompanying this paper.

Code availability

The codes generated during the current study are available from the second corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. Dr. Lei Si is funded by a NHMRC Early Career Fellowship (GNT1139826).

Ethics approvals

Medical ethics approvals were obtained from the University of Tasmania’s Health and Medical Human Research Ethics Committee (approval number H0018235).

Consent to participate

Our de-identified data is based on the confidential administrative database.

Consent to publication

All authors provide consent for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Qing Xia, Email: Qing.Xia@utas.edu.au.

Andrew J. Palmer, Email: Andrew.Palmer@utas.edu.au

References

- 1.Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet. 2014;384:766–781. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC) Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128.9 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet. 2017;390:2622–2627. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33113-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare . Overweight and obesity: an interactive insight. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Australian Bureau of Statistics. 4364.0.55.001 - National Health Survey: First Results, 2017–18 (LATEST ISSUE Released at 11:30 AM (CANBERRA TIME) 27/03/2019).

- 5.Guh DP, Zhang W, Bansback N, Amarsi Z, Birmingham CL, Anis AH. The incidence of co-morbidities related to obesity and overweight: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pub Health. 2009;9:88. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dobbs R, Sawers C, Thompson F, et al.: Overcoming obesity: an initial economic assessment. McKinsey Global Institute: Jakarta, Indonesia. http://www.mckinsey.com/industries/healthcaresystems-and-services/our-insights/how-the-world-could-better-fightobesity. (Accessed 1 Nov 2014)

- 7.Welbourn R, Pournaras DJ, Dixon J, et al. Bariatric surgery worldwide: baseline demographic description and one-year outcomes from the second IFSO global registry report 2013–2015. Obes Surg. 2018;28:313–322. doi: 10.1007/s11695-017-2845-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Angrisani L, Santonicola A, Iovino P, Formisano G, Buchwald H, Scopinaro N. Bariatric surgery worldwide 2013. Obes Surg. 2015;25:1822–1832. doi: 10.1007/s11695-015-1657-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang SH, Stoll CR, Song J, Varela JE, Eagon CJ, Colditz GA. The effectiveness and risks of bariatric surgery: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis, 2003–2012. JAMA Surg. 2014;149:275–287. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.3654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xia Q, Campbell JA, Ahmad H, et al. Bariatric surgery is a cost-saving treatment for obesity—A comprehensive meta-analysis and updated systematic review of health economic evaluations of bariatric surgery. Obes Rev. 2019;1:1–15. doi: 10.1111/obr.12932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weiner JP, Goodwin SM, Chang HY, et al. Impact of bariatric surgery on health care costs of obese persons: a 6-year follow-up of surgical and comparison cohorts using health plan data. JAMA Surg. 2013;148:555–562. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grenda T, Pradarelli J, Thumma J, Dimick J. Variation in hospital episode costs with bariatric surgery. JAMA Surg. 2015;150:1109–1115. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2015.2394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gounder ST, Wijayanayaka DR, Murphy R, et al. Costs of bariatric surgery in a randomised control trial (RCT) comparing Roux en Y gastric bypass vs sleeve gastrectomy in morbidly obese diabetic patients. N Z Med J. 2016;129:43–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Banerjee S, Garrison LP, Jr, Flum DR, Arterburn DE. Cost and health care utilization implications of bariatric surgery versus intensive lifestyle and medical intervention for type 2 diabetes. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2017;25:1499–1508. doi: 10.1002/oby.21927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zubiaurre PR, Bahia LR, da Rosa MQM, et al. Estimated costs of clinical and surgical treatment of severe obesity in the brazilian public health system. Obes Surg. 2017;27:3273–3280. doi: 10.1007/s11695-017-2776-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith VA, Arterburn DE, Berkowitz TSZ, et al. Association between bariatric surgery and long-term health care expenditures among veterans with severe obesity. JAMA Surg. 2019;154:e193732–e193732. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.3732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) Weight loss surgery in Australia 2014–15: Australian hospital statistics. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Campbell JA, Hensher M, Davies D, et al. Long-term inpatient hospital utilisation and costs (2007–2008 to 2015–2016) for publicly waitlisted bariatric surgery patients in an australian public hospital system based on Australia's activity-based funding model. Pharmacoecon Open. 2019;3:599–618. doi: 10.1007/s41669-019-0140-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Look Hong NJ, Cheng SY, Wright FC, Petrella TM, Earle CC, Mittmann N. Resource utilization and disaggregated cost analysis for initial treatment of melanoma. J Cancer Policy. 2018;16:63–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jcpo.2018.04.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cuschieri S. The STROBE guidelines. Saudi J Anaesth. 2019;13:S31–S34. doi: 10.4103/sja.SJA_543_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Husereau D, Drummond M, Petrou S, et al. Consolidated health economic evaluation reporting standards (CHEERS) statement. Value Health. 2013;16:e1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2013.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Australian Council on Federal Financial Relations. National Partnership Agreement on Improving Health Services in Tasmania. (2014)

- 23.The Australian Government. 2020–25 National health reform agreement (NHRA). department of health. https://www.health.gov.au/initiatives-and-programs/2020-25-national-health-reform-agreement-nhra. (Accessed 30 May 2020)

- 24.Update from the prime minister on hospital funding over the next 5 years. https://www.health.gov.au/news/update-from-the-prime-minister-on-hospital-funding-over-the-next-5-years [press release]. (Accessed 30 May 2020).

- 25.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Procedures data cubes. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/hospitals/procedures-data-cubes/contents/user-guide. (Accessed 23 May 2019).

- 26.The Campbell and Cochrane Economics Methods Group (CCEMG): The evidence for policy and practice information and coordinating centre (EPPI-Centre). CCEMG - EPPI-centre cost converter. http://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/costconversion/default.aspx. (Accessed Oct 2020).

- 27.Independent Hospital Pricing Authority (IHPA): Australian hospital patient costing standards version 3.1.https://www.ihpa.gov.au/sites/default/files/publications/ahpcs-version3.1.pdf?acsf_files_redirect. (Accessed Jul 2014).

- 28.Neuhäuser M. Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney Test. In: Lovric M, editor. International encyclopedia of statistical science. Springer; 2011. pp. 1656–1658. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deb P, Norton EC. Modeling health care expenditures and use. Annu Rev Pub Health. 2018;39:489–505. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040617-013517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keating CL, Dixon JB, Moodie ML, Peeters A, Playfair J, O'Brien PE. Cost-efficacy of surgically induced weight loss for the management of type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:580–584. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Monash University. First report of the pilot Bariatric Surgery Registry. (2013)

- 32.Monash University. Fifth Annual Report of the Bariatric Surgery Registry. (2017)

- 33.Monash University. Bariatric Surgery Registry Seventh Annual Report: 2018/19. (2018/19)

- 34.Reoch J, Mottillo S, Shimony A, et al. Safety of laparoscopic vs open bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Surg. 2011;146:1314–1322. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gould JC. Considering the role of the laparoscopic adjustable gastric band: do not throw the baby out with the bathwater. JAMA Surg. 2017;152:842. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O’Brien P, Brown W. Outcomes after adjustable gastric banding. JAMA Surg. 2018;153:190. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.4513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maciejewski ML, Smith VA, Livingston EH, et al. Health care utilization and expenditure changes associated with bariatric surgery. Med Care. 2010;48:989–998. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181ef9cf7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Doble B, Wordsworth S, Rogers CA, Welbourn R, Byrne J, Blazeby JM. What are the real procedural costs of bariatric surgery? A systematic literature review of published cost analyses. Obes Surg. 2017;27:2179–2192. doi: 10.1007/s11695-017-2749-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arterburn DE, Telem DA, Kushner RF, Courcoulas AP. Benefits and risks of bariatric surgery in adults: a review. JAMA. 2020;324:879–887. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.12567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Borisenko O, Colpan Z, Dillemans B, Funch-Jensen P, Hedenbro J, Ahmed AR. Clinical indications, utilization, and funding of bariatric surgery in europe. Obes Surg. 2015;25:1408–1416. doi: 10.1007/s11695-014-1537-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Doumouras AG, Albacete S, Mann A, Gmora S, Anvari M, Hong D. A longitudinal analysis of wait times for bariatric surgery in a publicly funded regionalized bariatric care system. Obes Surg. 2020;30:961–968. doi: 10.1007/s11695-019-04259-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Anvari M, Lemus R, Breau R. A landscape of bariatric surgery in canada: for the treatment of obesity, type 2 diabetes and other comorbidities in adults. Can J Diabetes. 2018;42:560–567. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjd.2017.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Arteaga-González IJ, Martín-Malagón AI, Ruiz de Adana JC, de la Cruz VF, Torres-García AJ, Carrillo-Pallares AC. Bariatric surgery waiting lists in Spain. Obes Surg. 2018;28:3992–3996. doi: 10.1007/s11695-018-3453-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Christou NV, Efthimiou E. Bariatric surgery waiting times in Canada. Can J Surg J Can Chirurgie. 2009;52:229–234. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alvarez R, Bonham AJ, Buda CM, Carlin AM, Ghaferi AA, Varban OA. Factors associated with long wait times for bariatric surgery. Ann Surg. 2019;270:1103–1109. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Diamant A, Cleghorn MC, Milner J, et al. Patient and operational factors affecting wait times in a bariatric surgery program in Toronto: a retrospective cohort study. CMAJ Open. 2015;3:E331–E337. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20150020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Campbell JA, Venn A, Neil A, Hensher M, Sharman M, Palmer AJ. Diverse approaches to the health economic evaluation of bariatric surgery: a comprehensive systematic review. Obes Rev. 2016;17:850–894. doi: 10.1111/obr.12424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lucchese M, Borisenko O, Mantovani LG, et al. Cost-utility analysis of bariatric surgery in italy: results of decision-analytic modelling. Obes Facts. 2017;10:261–272. doi: 10.1159/000475842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cohen RV, Luque A, Junqueira S, Ribeiro RA, Le Roux CW. What is the impact on the healthcare system if access to bariatric surgery is delayed? Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13:1619–1627. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2017.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xu X, Grossetta Nardini HK, Ruger JP. Micro-costing studies in the health and medical literature: protocol for a systematic review. Syst Rev. 2014;3:47. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-3-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting this study are provided in the results section of this paper and as supplementary information accompanying this paper.

The codes generated during the current study are available from the second corresponding author on reasonable request.