Abstract

Transcriptional induction of the interleukin-2 receptor alpha-chain (IL-2Rα) gene is a key event regulating T-cell-mediated immunity in mammals. In vivo, the T-cell-restricted protein Elf-1 and the general architectural transcription factor HMG-I(Y) cooperate in transcriptional regulation of the human IL-2Rα gene by binding to a specific positive regulatory region (PRRII) in its proximal promoter. Employing chromatin reconstitution analyses, we demonstrate that the binding sites for both HMG-I(Y) and Elf-1 in the PRRII element are incorporated into a strongly positioned nucleosome in vitro. A variety of analytical techniques was used to determine that a stable core particle is positioned over most of the PRRII element and that this nucleosome exhibits only a limited amount of lateral translational mobility. Regardless of its translational setting, the in vitro position of the nucleosome is such that DNA recognition sequences for both HMG-I(Y) and Elf-1 are located on the surface of the core particle. Restriction nuclease accessibility analyses indicate that a similarly positioned nucleosome also exists on the PRRII element in unstimulated lymphocytes when the IL-2Rα gene is silent and suggest that this core particle is remodeled following transcriptional activation of the gene in vivo. In vitro experiments employing the chemical cleavage reagent 1,10-phenanthroline copper (II) covalently attached to its C-terminal end demonstrate that HMG-I(Y) protein binds to the positioned PRRII nucleosome in a direction-specific manner, thus imparting a distinct architectural configuration to the core particle. Together, these findings suggest a role for the HMG-I(Y) protein in assisting the remodeling of a critically positioned nucleosome on the PRRII promoter element during IL-2Rα transcriptional activation in lymphocytes in vivo.

The magnitude and duration of the antigen-induced T-cell immune response are critically regulated by interaction of interleukin-2 (IL-2) with high-affinity IL-2 receptor (IL-2R) complexes (reviewed in references 32 and 37). The high-affinity IL-2R is composed of three protein subunits, α, β, and γ. Resting T lymphocytes express intermediate-affinity (Kd, ∼10−9 M) complexes consisting of the IL-2Rβ and IL-2Rγ chains. Following lymphocyte activation, the IL-2Rα chain is induced, allowing formation of high-affinity (Kd, ∼10−11 M) complexes consisting of the α, β, and γ chains, as well as low-affinity receptors containing only IL-2Rα. Both intermediate- and high-affinity receptors transduce mitogenic signals in response to IL-2, whereas low-affinity receptors do not. Thus, while dimerization of IL-2Rβ and IL-2Rγ is crucial for IL-2 signaling (36), induction of IL-2Rα regulates formation of high-affinity receptors and acquisition by a cell of full responsiveness to IL-2, leading to a maximal immune response. This essential function of IL-2Rα is underscored by the observation that knockout mice lacking IL-2Rα develop autoimmunity and die at a young age (64) and that truncation of this gene in humans leads to severe immunodeficiency (50).

Corresponding to its pivotal role in controlling T-cell effector function, transcriptional regulation of the IL-2Rα gene is tightly regulated in vivo (reviewed in reference 30). Within 1 h of stimulation with antigens or mitogens, its transcription is potently induced in normal human T cells. Transcription is also rapidly induced in Jurkat cells by phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate (PMA) and the Tax transactivator protein of human T-cell leukemia type 1 (9). As a consequence, the Jurkat human T-cell line has been widely used to delineate regulatory regions of the human IL-2Rα gene promoter. The human promoter contains at least three 5′ upstream positive regulatory regions, PRRI (nucleotides [nt] −276 to −244) (4, 10), PRRII (nt −137 to −64) (23), and PRRIII (nt −3780 to −3703) (24, 29). PRRI contains binding sites for NF-κB and serum response factor, while PRRII contains binding sites for Elf-1, a lymphoid-myeloid cell-specific Ets family member, and the architectural transcription factor HMG-I(Y), a member of the high mobility group of nonhistone proteins (6, 23). PRRIII contains the binding sites for multiple factors (including Elf-1, HMG-I(Y), Stat5, and GATA family proteins) involved in IL-2 induction of the IL-2Rα gene (24, 25, 49). Together, these three elements are important for regulating inducible transcription of the IL-2Rα gene.

Regulation of IL-2Rα gene expression by PRRI and PRRII is the result of both specific protein-DNA and protein-protein interactions of HMG-I(Y), Elf-1, NF-κB, and serum response factor (23). For example, HMG-I(Y) protein can physically interact, in vitro, with each of the other proteins that bind to these regulatory elements (8, 23). Multiple interactions between the transcription factors that bind to PRRI and PRRII have been suggested to result in the formation of a highly ordered multiprotein complex (also known as an enhanceosome [54]) that regulates IL-2Rα promoter activity in vivo (23). Prior to such enhanceosome formation, however, it is reasonable to suspect that a change in the chromatin structure of the human IL-2Rα promoter region that facilitates gene transcriptional activation must occur (reviewed in references 41 and 65). Consistent with this suggestion, several new DNase I nuclease-hypersensitive sites appear in the promoter region of transcriptionally active murine IL-2Rα genes which are absent from the promoters of inactive genes (49, 52).

In marked contrast to the situation for the mouse IL-2Rα promoter, there is a paucity of information about the chromatin structure of the human IL-2Rα promoter in T lymphocytes, either before or after transcriptional activation of the gene. We now report a detailed analysis of the chromatin structure of the proximal IL-2Rα promoter as it exits in vitro in artificial reconstitutes and in vivo in lymphoid cells before and after transcriptional activation of the gene by mitogenic stimulation. These findings, along with data on the substrate binding characteristics of the HMG-I(Y) and Elf-1 proteins to a positioned nucleosome on the promoter in vitro, are discussed in terms of a possible role played by alterations in promoter chromatin structure in regulating expression of the human IL-2Rα gene in human lymphocytes in vivo.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

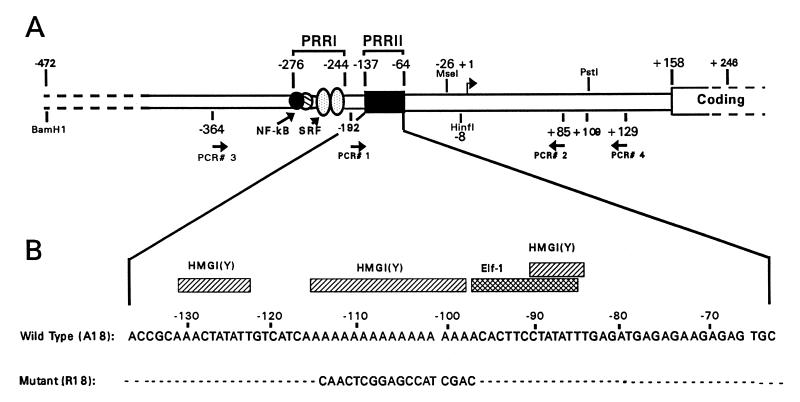

Isolation, mutagenesis, and radiolabeling of DNA fragments.

A cloned 581-bp BamHI-PstI restriction fragment encompassing nt −472 to +109 of the human IL-2Rα gene and its 5′ proximal promoter region (21) served as the starting material (Fig. 1) for isolating subfragments of the promoter for use in in vitro chromatin reconstitution experiments. This fragment spans both the PRRI and PRRII enhancer elements (23). Subfragments were isolated by either selective restriction enzyme digestion or PCR amplification (3). For example, as shown in Fig. 1, the 277-bp promoter fragment that encompasses PRRII and its flanking regions was amplified using the following PCR primer pair: PCR #1 (sense; nt −192 to −173), 5′-CCAGCCCACACCTCCAGCAA-3′, and PCR #2 (antisense; nt +85 to +65), 5′-CCTCTTTTTGGCATCGCGCCG-3′. Likewise, the 493-bp fragment encompassing both PRRI and PRRII (nt −364 to +129) was amplified using the following PCR primer pair: PCR #3 (sense; nt −364 to −346), 5′-CTG AGGACGTTACAGCCCT-3′, and PCR #4 (antisense; nt +112 to +129), 5′-GTGAAGCGGAGGTCTTTC-3′. A mutant IL-2Rα promoter construct designated R18 (Fig. 1B) was produced as follows: an oligonucleotide containing 18 randomized residues (along with nonmutagenized IL-2Rα oligonucleotides flanking either end) was synthesized, and this fragment was inserted by PCR techniques into the IL-2Rα promoter DNA, thereby replacing the wild-type homopolymer “A” tract (A18) in the PRRII enhancer element. Standard gel electrophoretic procedures (3) were used to isolate all DNA fragments, followed by purification on QIAGEN columns (QIAGEN Inc., Chatsworth, Calif.). Isolated DNA fragments were 5′ end radiolabeled with T4 polynucleotide kinase and [γ-32P]ATP or 3′ end labeled by filling using Klenow polymerase and [α-32P]ATP, and Southern blot analyses were performed as described in reference 3.

FIG. 1.

Schematic diagram of the positive regulatory regions (PRRs) of the 5′ proximal promoter of the human IL-2Rα gene. Shown is the promoter region between nucleotides −472 and +158, indicating the binding sites for previously identified transcription factors involved in regulating gene expression in vivo (23, 24). Note that nt +1 is the more 3′ of the two major identified transcription start sites for this gene. (A) PCR primer locations and restriction enzyme cut sites used in this study are indicated. (B) Sequences of the wt (A18) and mutant (R18) PRRII promoter DNAs, with hatched boxes indicating the binding sites for HMG-I(Y) and Elf-1 of the wt promoter (23).

Purification of recombinant wt and mutant HMG-I(Y) proteins.

Full-length recombinant human HMG-I protein [i.e., the unspliced member of the HMG-I(Y) protein family (6); here, for simplicity, we refer to this as HMG-I(Y)] was produced using the expression vector pET7C carrying the wild-type (wt) human HMG-I cDNA (26) as previously described (39). Production and purification of the mutant protein HMG-IΔE91, which has a deletion of the 17 C-terminal amino acids found in the wt HMG-I protein, has been described (47). The recombinant mutant HMG-IΔE91 protein has a single cysteine residue added to its C terminus that was used as the conjugation site for the chemical nuclease 1,10-phenanthroline copper(II) (OP-Cu) complex (40) employed in footprinting reactions (see below). The purity and integrity of all protein samples were confirmed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) analysis (3). Protein concentrations were determined spectrophotometrically employing either a Bio-Rad (Richmond, Calif.) protein assay or using the extinction coefficient (ɛ220) of 74,000 liters/mol · cm for HMG-I(Y) (46).

Isolation of nucleosome core particles and histone octamers.

Packed, frozen chicken erythrocytes in sodium citrate were purchased from Lampire Biologicals (Pipersville, Pa.). Trimmed chicken core particles were prepared employing micrococcal nuclease digestion of isolated nuclei as previously described (46, 48). For some experiments, the extended amino-terminal histone tails were removed from isolated monomer nucleosomes by limited trypsin digestion as described previously (47) and the tail-less core particles were used for in vitro chromatin reconstitutions. Histone concentrations were determined using an ɛ230 of 4.2 liters/g · cm, and purity was monitored by denaturing gel electrophoresis as previously reported (48).

Chromatin reconstitutions, competitive reconstitutions, and EMSAs.

Nucleosomes were reconstituted onto radiolabeled DNA fragments in one of two ways (66): (i) by exchange with isolated chicken erythrocyte nucleosomal core in high salt followed by step-wise dilutions to low salt or (ii) by dialysis from high salt with purified histone octamers, following established protocols. Quality control of chromatin reconstitutes was monitored by native nucleoprotein gel electrophoresis (0.8% agarose, 45 mM Tris-borate [pH 8.3], 1 mM EDTA), and the integrity of the core histones was checked before and after reconstitutions by denaturing SDS-PAGE. For typical chromatin assembly reactions, less than 5% of the input labeled DNA fragments remained as free DNA at the end of the reconstitutions and, where necessary to avoid possible background problems, this was removed by standard purification techniques (48). Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) employed purified proteins and either radiolabeled DNA substrates or in vitro-reconstituted nucleosome core particles and were performed as previously described (23, 47, 48).

DNase 1, hydroxyl radical, and copper-phenanthroline cleavages of reconstituted nucleosomes.

Reconstituted chromatin substrates and free DNAs were probed, both alone and in combination with various purified recombinant proteins, by a variety of standard cleavage reagents to obtain detailed information about their in vitro organization. Protocols described by Hayes and his colleagues (17, 18, 66) were generally employed for analyses involving the use of hydroxyl radical cleavages, whereas the methods of Pan et al. (40) were followed in conjugating and using the cleavage OP-Cu complex attached to the C-terminal end of the mutant HMG-IΔE91 protein. The optimum cleavage conditions for each reagent and for each reconstituted chromatin preparation were determined empirically. After treatment, labeled DNA fragments were recovered from the chromatin particles by protease digestion and phenol-chloroform extraction and precipitated with ethanol. Cleavage products were then separated by electrophoresis on either 6 or 8% sequencing gels. Band intensities on sequencing gels were analyzed using a PhosphorImager and ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics Corp., Sunnyvale, Calif.).

Determination of boundaries of translationally positioned nucleosomes.

Two different methods were employed to determine the approximate 5′ and 3′ boundaries of translationally positioned nucleosomes on IL-2Rα promoter DNA reconstituted into chromatin in vitro. Both procedures employed digestion of reconstituted chromatin with micrococcal nuclease (Boehringer Mannheim, GmbH) to release monomer nucleosomal core particles (27). Nucleosome core particle quality was routinely monitored by native nucleoprotein gel electrophoresis, and DNA sizes were determined by electrophoresis on denaturing, 6% polyacrylamide sequencing gels (3). Monomer core particle DNA was purified away from the core histones and subsequently analyzed for nucleosome translational positioning. In the first analytical method, the core particle DNA was enzymatically 32P labeled on both of its 5′ ends by using T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs), and the resulting labeled fragment was probed by digestion with selected restriction endonucleases to determine whether their recognition sequences were present within the fragments. In this assay, the presence of a restriction enzyme cut site within the isolated fragment indicates that the DNA recognition site for that particular enzyme was protected from micrococcal nuclease digestion in the original chromatin by the presence of a positioned nucleosome and the sizes of the radiolabeled DNA subfragments released by the digestion indicate the distance from the restriction enzyme cut site to the 5′ and 3′ borders of the nucleosome (51, 56). The second method involved primer extension by linear PCR amplification (10 extension cycles) from appropriately selected synthetic oligonucleotide primers located within the nucleosome DNA (67). The primers used for these analyses were as follows: PCR #5 (sense; nt −62 to −42), 5′-TAGGCAGTTTCCTGGCTGAA-3′, and PCR #6 (antisense; nt −20 to −40), 5′-CTTTAAGTATTGGGCTGGCG-3′. The extension products were radiolabeled by incorporation of α-32P-labeled deoxynucleoside triphosphates (New England Nuclear) into the PCR, separated by electrophoresis on a 6% sequencing polyacrylamide gel, and quantified with a PhosphorImager.

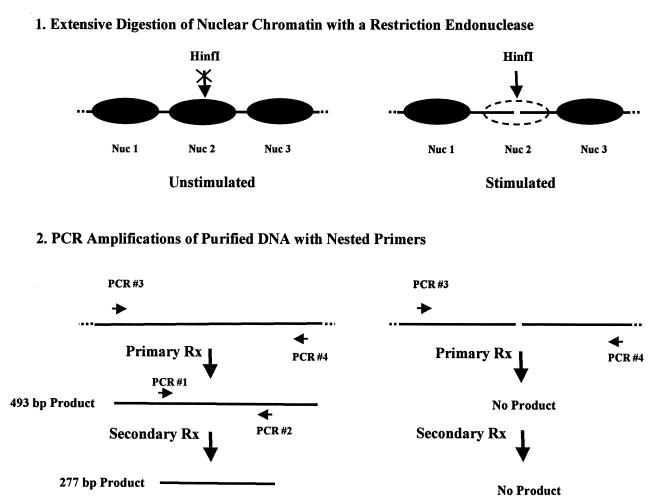

Restriction nuclease accessibility analysis of in vivo chromatin structure.

Sensitivity of the chromatin of isolated nuclei to digestion by restriction endonuclease enzymes was used as a probe to monitor the in vivo structure of nucleosomes in the region of a suspected positioned core particle on the IL-2Rα promoter. An outline of the strategy of these chromatin accessibility analyses is shown in Fig. 8 and followed a previously published two-step PCR amplification protocol (61). Human Jurkat T-leukemia cells (clone E6-1; American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, Va.) were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 U of penicillin/ml, and 100 U of streptomycin/ml. Nuclei (about 7 × 107 cells/aliquot) from either control or stimulated (6-h treatment with 10 μg of concanavalin A [Con-A] per ml plus 10 ng of phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate [PMA] per ml) cells were isolated as previously described (23) and pelleted by centrifugation. For restriction endonuclease digestions (e.g., with either MseI or HinfI; New England Biolabs), about 2 × 107 nuclei were resuspended in 1 ml of buffer A (0.34 M sucrose, 10 mM HEPES [pH 8.0], 60 mM KCl, 2 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM EGTA, 1.5 mM dithiothreitol, 0.5 mM spermine, 0.15 mM spermidine) plus 0.5% NP-40. After a second pelleting, nuclei were washed once in buffer A without NP-40 and then digested in 200 μl with the indicated restriction enzyme at 37°C for 1 h. The reaction was stopped by addition of EDTA (to 25 mM), SDS (to 0.5%), and proteinase K (400 μg/ml), and the samples were then digested overnight at 37°C. DNA was extracted using phenol-chloroform, precipitated with ethanol, and resuspended in 100 μl of TE (10 mM Tris [pH 7.4], 1 mM EDTA). The isolated DNAs from the digested nuclei were subjected to a two-step PCR protocol to specifically detect regions of the IL-2Rα promoter. Equal amounts of DNA from uninduced and induced nuclei were used for the primary PCR amplification reactions. In the primary amplification reaction (25 cycles), the external primer pair PCR #3 (at nt −364) and PCR #4 (at nt +129) (Fig. 1) was used. Products of this first reaction were then serially diluted and subjected to a secondary PCR amplification (25 cycles) using the internal primer pair PCR #1 (at nt −192) and PCR #2 (at nt +85). In this dilution series, equal concentrations of the DNA amplified in the primary reaction from uninduced and induced nuclei were used at each corresponding dilution as the starting material for the second PCR amplification. Aliquots of the secondary amplification were analyzed on 1.2% agarose gels. As a control, a mock nuclease digestion reaction was performed, in which no restriction enzyme was added to the isolated nuclei at the start of the procedure. A second control was to demonstrate that restriction enzymes could be used to distinguish free DNA from nucleosome-containing reconstituted chromatin in vitro using the same reaction conditions as used for the in vivo analyses.

FIG. 8.

Experimental strategy for using restriction nucleases as accessibility probes for chromatin structure and positioned nucleosomes in vivo. The diagram outlines the restriction enzyme digestion accessibility assay and two-step PCR amplification procedure for assessing the in vivo chromatin structure of the IL-2Rα promoter at the position of a suspected positioned nucleosome on the PRRII enhancer before and after transcriptional activation of the gene (see the text and Materials and Methods for details).

RESULTS

The PRRII enhancer region reconstitutes into a rotationally positioned nucleosome in vitro.

The translational position of a nucleosome refers to where the histone core starts and finishes its association with DNA, whereas rotational positioning refers to which face of the double helix is in contact with, or directed away from, the histone core (51). Only a small percentage (≤5%) of the bulk genomic DNA of eukaryotic cells is able to direct either the rotational or translational positioning of nucleosomes when reconstituted into chromatin in vitro (33). The regulatory regions of certain inducible eukaryotic genes appear to represent a subclass of these nucleosome positioning sequences, since the promoters of many such genes contain arrays of precisely positioned core particles prior to their transcriptional activation in vivo (reviewed in references 51 and 56). Using in vitro chromatin reconstitution experiments, we now demonstrate that the PRRII enhancer region of the 5′ proximal promoter of the human IL-2Rα gene belongs to this category of nucleosome-positioning DNA sequences. For these experiments, different lengths of 5′ 32P-end-labeled IL-2Rα promoter DNA (Fig. 1) were individually reconstituted into chromatin in vitro by two different procedures (see Materials and Methods), both of which produced the same results. Various DNA cleavage reagents were used to probe the fine structures of each of these chromatin reconstitutes, and the results of these cleavage reactions were analyzed by high-resolution mapping techniques. In order not to bias the reconstitution results, in each assembly reaction the starting IL-2Rα promoter DNA fragment was always of sufficient length to allow the formation of either multiple and/or randomly positioned nucleosomes on the fragment. These results suggested that PRRII-containing fragments of the IL2-Rα promoter exhibited the strongest ability to position nucleosomes in vitro (data not shown).

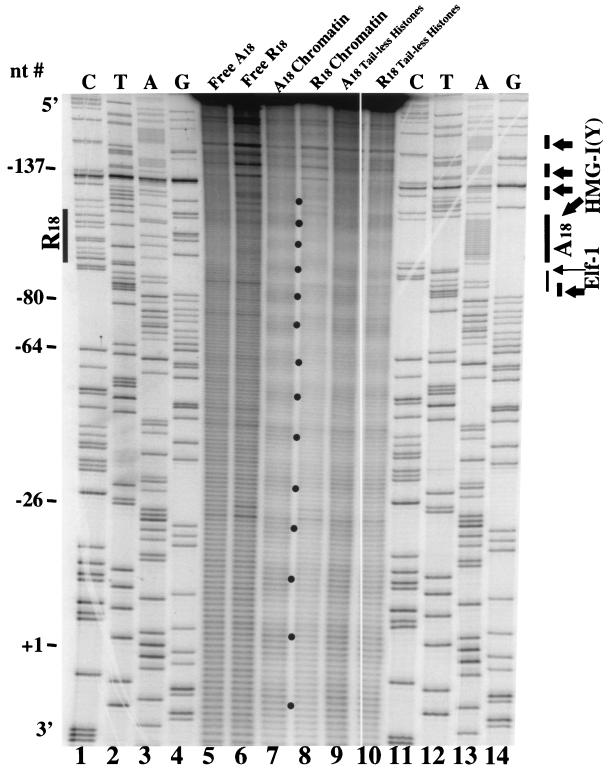

To further investigate the nucleosome positioning ability of the PRRII element, a 277-bp PCR-derived fragment from the wt promoter between nt −192 and +85 (amplified by primers PCR #1 and PCR #2; Fig. 1) was assembled into monomer nucleosome-containing chromatin in vitro. As seen in Fig. 2, this wt promoter fragment (designated A18; Fig. 1) reconstituted a nucleosome whose DNA is rotationally positioned with respect to the histone core. The wt A18 promoter DNA was radiolabeled at its 3′ end, reconstituted into chromatin, and then subjected to cleavage by hydroxyl radicals. Owing to their small size and minimal amount of substrate selectivity, cleavage by hydroxyl radicals allows determination of the fine structure of reconstituted DNA on the surface of histone octamers, with base pair resolution. As is evident in lane 7, such cleavage reveals an approximately 10-bp periodic cutting pattern that is characteristic of nucleosomal core particles that are rotationally positioned on DNA (17, 18). In contrast, hydroxyl radical cleavage of naked wt A18 promoter DNA (lane 5) yields a more uniform cutting pattern, with approximately equal cleavage frequency at each DNA base pair. From these and other results, we conclude that the reconstituted wt A18 chromatin contains a positioned nucleosome with a strong rotational setting on this PRRII-containing fragment of promoter DNA.

FIG. 2.

Nucleosomes reconstituted onto the IL-2Rα promoter are rotationally positioned. Hydroxyl radical cleavage mapping of the fine structure of a monomer nucleosome reconstituted onto 3′-end-labeled wt (A18) and mutant (R18) PRRII promoter DNA fragments. In each case, 277-bp promoter fragments amplified using primers PCR #1 and PCR #2 (cf., Fig. 1) were used in the experiments. Lanes 1 to 4, dideoxy sequencing lanes of the mutant R18 promoter DNA; lane 5, free wt A18 DNA; lane 6, free mutant R18 DNA; lane 7, wt A18 DNA reconstituted in vitro into chromatin; lane 8, mutant R18 DNA reconstituted in vitro into chromatin; lane 9, wt A18 DNA reconstituted in vitro into chromatin with tail-less, typsinized histone octamer cores; lane 10, mutant R18 DNA reconstituted in vitro into chromatin with tail-less, typsinized histone octamer cores; lanes 11 to 14, dideoxy sequencing lanes of the wt A18 promoter DNA. The solid dots indicate the positions of hydroxyl radical cleavages spaced with an approximately 10-bp periodicity indicative of a rotationally positioned nucleosome. The vertical lines on the right indicate the sites on naked wt IL-2Rα promoter DNA that have previously been demonstrated to be footprinted by HMG-I(Y) and Elf-1 (23).

DNA fragments containing long homopolymer adenine stretches, such as that present in the wt A18 PRRII element, are more rigid than random sequence DNAs and therefore assemble into energetically less-stable nucleosome particles in vitro (18). In some cases, such homopolymer A tracts are also known to locally affect the structure of nucleosomes and lead to an increase in the access of transcription factors to such nucleosomal DNA in vivo (22, 67). Consistent with these observations, we have previously emphasized the biological significance of the A18 tract in the PRRII enhancer by demonstrating that deletion of this sequence element inhibits transcription from the IL-2Rα gene promoter in vivo (23). Additional studies reported by others have suggested that stretches of poly(dA-dT) residues may exert their in vivo function by establishing nucleosome positioning by acting as boundary elements (12) and/or by preventing nucleosome formation (13). We therefore investigated whether the A18 stretch might exert its biological function by influencing the formation of a positioned nucleosome on the PRRII element in chromatin reconstitutes in vitro. To accomplish this, a mutant PRRII promoter element, designated R18 because it contains a sequence of 18 randomized nucleotides replacing the wt A18 stretch (Fig. 1B), was produced by in vitro mutagenesis techniques. A 3′-labeled 277-bp fragment of the promoter containing this mutant R18 sequence was then reconstituted into chromatin in vitro and analyzed by hydroxyl radical cleavage. Interestingly, as shown in lane 8 of Fig. 2, the periodicity of the hydroxyl radical cleavage pattern of the reconstituted mutant R18 chromatin demonstrates that it too assembled into a positioned nucleosome with a strong rotational setting. The approximately 10-bp periodic hydroxyl radical cleavage patterns observed for both the wt A18 and mutant R18 promoter fragments are similar, with the phasing of cleavages on the R18 nucleosome being only slightly offset from those on the A18 core particle. Thus, the A18 region is not the major DNA determinant that establishes the PRRII element's ability to direct the formation of a rotationally positioned nucleosome in vitro. Furthermore, quantitative analyses of laser densitometry scans of the gel lanes shown in Fig. 2 indicate that both A18 and R18 sequences of the PRRII element are positioned on the surface of the positioned nucleosome (data not shown).

In a complementary set of experiments, we also investigated whether the basic polypeptide tails of the core histones were involved in establishing the rotational setting of monomer nucleosomes reconstituted on IL-2Rα promoter PRRII fragments. The results shown in Fig. 2 demonstrate that nucleosomes which have had the N-terminal tails of their core histone proteins selectively removed by limited protease digestion also assume strong rotational settings on both reconstituted wt A18 (lane 9) and mutant R18 (lane 10) promoter fragments. These findings are in agreement with the observations of others (11) that the N-terminal tails of histone octamers are not involved in establishing nucleosome position in vitro. Together, these data demonstrate that neither the homopolymer A18 tract found in the wt PRRII enhancer nor the basic tails of the octamer histones are involved in establishing the strong in vitro rotational positioning of nucleosomes on the PRRII element in chromatin reconstitutes. The intrinsic characteristics of the PRRII enhancer element responsible for its ability to position a nucleosome in vitro are unknown. However, based on the present PRRII mutagenesis data, this region of the IL-2Rα promoter can tentatively be placed in the positioning class of DNA fragments “with no evident sequence characteristics” as defined by Widlund et al. (63).

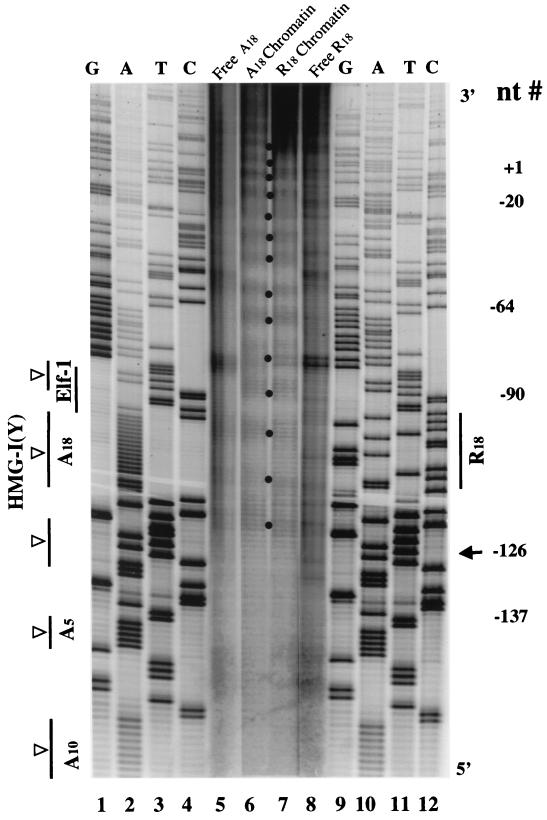

In a series of experiments parallel to those shown in Fig. 2, the same 277-bp wt A18 or the mutant R18 promoter fragments were selectively radiolabeled at their 5′ ends and assembled into chromatin products in vitro and the reconstitutes were subjected to hydroxyl radical cleavage analysis (Fig. 3). The cleavage patterns again demonstrate that rotationally positioned nucleosomes are detected over the PRRII sequence in both the reconstituted A18 (Fig. 3, lane 6) and mutant R18 (lane 7) fragments. In the case of these 5′-labeled substrates, however, it is apparent that the ∼10-bp repeat which characterizes a positioned nucleosome disappears immediately 5′ upstream of approximately nt −126 in both wt A18 and R18 reconstitutes (Fig. 3, arrow). These results suggest that 5′ of nt −126 there are no stable nucleosomes associated with either the wt or the mutant promoter fragments in the chromatin reconstitutes (see below).

FIG. 3.

The PRRII enhancer is a strong nucleosome-positioning element. Hydroxyl radical cleavage mapping of the fine structure of a monomer nucleosome reconstituted onto 5′-end-labeled wt (A18) and mutant (R18) PRRII promoter DNA fragments 277 bp in length (amplified with primers PCR #1 and PCR #2). Lanes 1 to 4, dideoxy sequencing lanes of the wt A18 promoter DNA; lane 5, free wt A18 DNA; lane 6, wt A18 DNA reconstituted in vitro into chromatin; lane 7, mutant R18 DNA reconstituted in vitro into chromatin; lane 8, free mutant R18 DNA; lanes 9 to 12, dideoxy sequencing lanes of the mutant R18 promoter DNA. The arrow indicates nt −126, the apparent end of the monomer core particle located over the PRRII enhancer. Other labels are the same as in Fig. 2.

Defining the in vitro borders of the translationally positioned PRRII nucleosome(s).

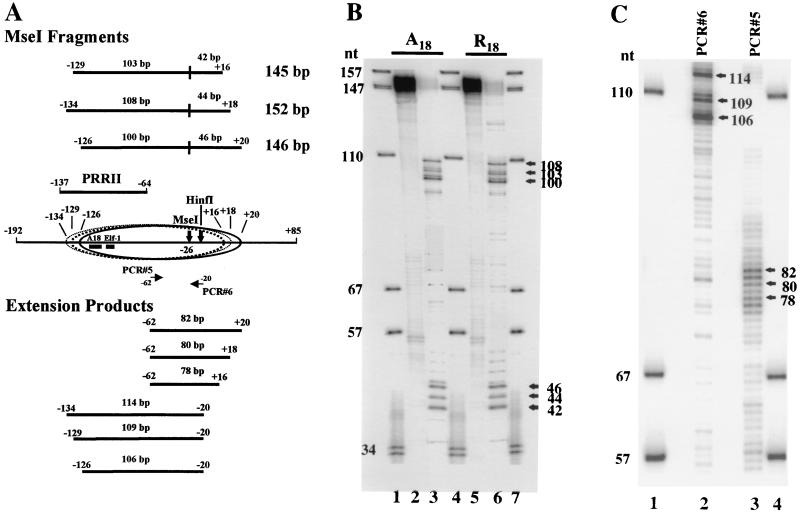

Two independent methods were use to more precisely determine the in vitro boundaries of the positioned monomer nucleosome on the PRRII enhancer element: restriction enzyme accessibility mapping and primer extension analysis. In the first method, micrococcal nuclease was used to digest the chromatin reconstitutes to core particles, and the resistant DNA fragments (∼146 bp in length) were isolated and enzymatically 32P labeled on both 5′ ends. The labeled DNA was then digested with MseI or HinfI (Fig. 4A). The presence of a restriction enzyme cut site within the micrococcal nuclease-released core particle DNA fragment indicates that this site was protected from enzyme digestion in the original reconstituted chromatin by its incorporation into a translationally positioned nucleosome (51, 56). Additionally, the sizes of the two radiolabeled DNA subfragments released by the digestion indicate the distance from the restriction enzyme cut site to the 5′ and 3′ borders of the positioned nucleosome.

FIG. 4.

Defining the borders of the translationally positioned nucleosome on PRRII DNA. (A) The diagram in the middle shows the boundaries of the translationally positioned nucleosome core particles on the reconstituted 277-bp, wt A18 PRRII DNA fragment as determined by the restriction nuclease and PCR primer extension analyses shown in panels B and C. The solid and dashed oval ellipsoids depict core particles that are occupying different translational settings on the IL2-Rα promoter based on DNA fragment sizes observed following MseI digestion (shown above the diagram) and PCR primer extension amplification (shown below the diagram) of isolated core particle DNA (see text for discussion). The position of the PRRII regulatory element, the A18 and Elf-1 sites, the sites for cleavage by the MseI and HinfI enzymes and the sites of primers PCR #5 and PCR #6 are shown along with relevant promoter nucleotide sequences. (B) Restriction enzyme cleavage analysis of the translational positions of a monomer nucleosome reconstituted onto 277-bp-long wt (A18) and mutant (R18) DNA promoter fragments containing the PRRII enhancer element. Lanes 1, 4, and 7, DNA molecular weight markers; lane 2, monomer wt A18 core particle DNA prior to restriction enzyme digestion; lane 3, monomer wt A18 core particle DNA digested with MseI; lane 5, monomer mutant R18 core particle DNA prior to restriction enzyme digestion; lane 6, monomer mutant R18 core particle DNA digested with MseI. (C) Determination of nucleosome borders using linear PCR primer extension analysis employing primers PCR #5 and PCR #6. Lanes 1 and 4, DNA molecular weight markers; lane 2, primer extension products obtained with primer PCR #6; lane 3, primer extension products obtained with primer PCR #5. (B and C) The sizes (in nucleotides) of various DNA fragments are indicated adjacent to the lanes.

Figure 4B shows the results of experiments in which 277-bp promoter fragments (between nt −192 and +85) were reconstituted into chromatin in vitro and then subjected to such nucleosome positioning analysis employing the restriction enzyme MseI. For both A18 (lane 2) and R18 (lane 5), the core particle-length fragments on this denaturing gel migrated as rather broad bands of radioactivity whose widths indicate that they contain DNA strands ranging in size between ∼145 and 152 bp. This heterogeneity in the sizes of core particle DNA released by micrococcal nuclease digestion is confirmed by the resolution of each of these broad bands into about three major DNA sub-bands upon longer electrophoresis of the samples (data not shown). A canonical nucleosome core particle is usually considered to contain approximately 145 to 147 bp of DNA (with an average of ∼146 bp) (34). However, the exact length of the DNA associated with a nucleosome core particle often varies somewhat depending on both the conditions and methods of core particle preparation and assay. Therefore, the differences in sizes of the observed core particle-length DNA fragments (Fig. 4B) are likely to be a product of incomplete enzymatic digestion of the in vitro chromatin substrates (27) and/or due to the presence of functional histone-DNA interactions extending beyond the boundaries of a classical core particle (65). The minor background bands seen on the gels are due to low levels of internal nicking of the nucleosomal DNA by the micrococcal nuclease. Nevertheless, none of this experimental size variation in the core particles interferes with the determination of the approximate in vitro 5′ and 3′ borders of the translationally positioned nucleosome(s) on this promoter fragment. For example, digestion of both A18 (Fig. 4B, lane 3) and R18 (lane 6) nucleosomal DNAs with MseI (which cuts at IL-2Rα nt −26; Fig. 1A and 4A) results in the release of two distinct clusters of DNA subfragments. One group of subfragments has apparent sizes of 108, 103, and 100 bp while the other has apparent sizes of 46, 44, and 42 bp. The diagram in Fig. 4A shows the translational position(s) of this core particle(s) based on restriction enzyme mapping and indicates that the nucleosome(s) is located internally on the fragment, with its 5′ border located at approximately nt −126. Both of these findings are consistent with the results of the hydroxyl footprinting analyses shown in Fig. 3, which also place the upstream boundary of a rotationally positioned nucleosome at approximately nt −126.

Primer extension analysis was employed as a second analytical method for determining the 5′ and 3′ translational boundaries of the in vitro-positioned core particle(s) on the PRRII enhancer DNA fragment. As illustrated in Fig. 4A, two synthetic oligonucleotide primers (PCR #5 and PCR #6) that are located internally to the positioned nucleosome(s) were individually used for these analyses. The radiolabeled products of these linear-extension PCRs were separated by electrophoresis on a sequencing gel, and the results are shown in Fig. 4C. Lanes 1 and 4 are molecular weight markers. Lane 2 shows the products obtained with primer PCR #6, whose products extend toward the 5′ edge of the nucleosome. Lane 3 shows the products of primer PCR #5, whose products extend toward the 3′ end. From this gel, it is evident that extension from primer PCR #5 produces three prominent groups of clustered products with apparent lengths centering around approximately 106, 109, and 114 bp (lane 2). Extension products from primer PCR #6 gives rise to a distinct cluster of bands, including prominent bands approximately 78, 80, and 82 bp in length (lane 3). The lower part of Fig. 4A illustrates the positioning of these prominent extension products on the IL-2Rα promoter sequence relative to the location of the primers.

The diagram in the center of Fig. 4A illustrates the agreement between the experimental results obtained by restriction enzyme mapping (Fig. 4B) and primer extension analysis (Fig. 4C) for determining the approximate 5′ and 3′ borders of the positioned nucleosome on this segment of promoter DNA in vitro. Furthermore, the results of both techniques are in agreement with hydroxyl radical cleavage analyses of the same reconstituted chromatin substrate (Fig. 2 and 3). The cumulative data indicate that a stable nucleosome can be localized to three different centrally located positions on this promoter fragment in vitro. One core particle of ∼146 bp appears to be situated between nt −126 and +20 while a second nucleosome of ∼145 bp seems to occupy a position between nt −129 and +16. Multiple in vitro translational settings for a strongly positioned nucleosome is a well characterized phenomenon attributed to lateral mobility of core particles under low-salt conditions in the absence of histone H1 (35, 43, 58). A third, somewhat larger nucleosome of ∼152 bp appears to occupy a position between nt −134 and +18. As discussed earlier, these variations in core particle size may either result from incomplete micrococcal nuclease digestion of the original reconstituted chromatin or perhaps be derived from octamer histone interactions with DNA outside the canonical 146 bp of the core particle (55). Regardless of their position, however, competitive reconstitution assays indicate that the core particles positioned on the PRRII fragment are very stable in vitro, with a difference in free energy of nucleosome formation of approximately −504 ± 87 cal/mol (data not shown).

The in vitro-positioned nucleosome blocks both HMG-I(Y) and Elf-1 binding sites.

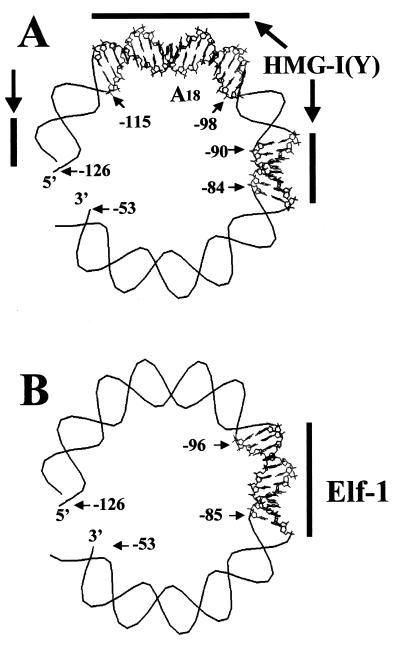

The most important conclusion to be drawn from the above in vitro experiments is that, regardless of the translational setting, a stable nucleosome is positioned over most of the PRRII enhancer element such that the recognition sequences for both the Elf-1 protein and the homopolymer A18 binding site for HMG-I(Y) are always located on the surface of a core particle (Fig. 4A). Figure 5 illustrates that the binding sites for HMG-I(Y) and Elf-1 (23) are located on the surface of the nucleosome positioned between nt −126 and +20 even though, of the three different translational settings, this core particle covers the smallest portion of the PRRII enhancer element. These two panels show polar views of a positioned nucleosome in which 73 bp of the PRRII promoter DNA between nt −126 and −53 are shown wrapped about one half-turn around the surface of an imaginary core of octamer histones (Superhelix-2 Program; K. Ohlenbusch). The diagram in Fig. 5B indicates the binding site for the Elf-1 protein on the surface of this particular positioned nucleosome is such that the major groove of the DNA between nt −96 and −90 (i.e., about half of the Elf-1 recognition sequence) is directed inwards towards the histone octamer core. A similar steric occlusion of a large portion of the Elf-1 recognition sequence exists on all three of the in vitro nucleosome positions, regardless of their translational setting (Fig. 4A). Since Elf-1 is a member of the Ets family of transcription factors whose helix-turn-helix DNA-binding domains make primary contact with the DNA major groove (62), steric blockage of part of its major groove binding site by association with histones might be expected to inhibit Elf-1 binding. Likewise, as illustrated in Fig. 5A, regardless of the nucleosome translational setting (Fig. 4A), several of the minor groove binding sites of the HMG-I(Y) protein in the A18 region of the PRRII enhancer are also blocked by association with the surface of the core histones. Nevertheless, in the case of the HMG-I(Y) protein, binding to the in vitro-positioned PRRII nucleosome would be expected as a consequence of the protein's previously reported ability to induce localized changes in the rotational setting of DNA on the surface of isolated core particles (48), a prediction confirmed by electrophoretic mobility shift experiments (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

The A18 and Elf-1 binding sites are located on the surface of the PRRII nucleosome in vitro. (A) Diagrammatic polar view representation of an approximate one-half turn (74 bp) of the PRRII promoter DNA (nt −126 to −53) from the positioned nucleosome located between nt −126 and +20 (Fig. 4C), wrapped around the surface of an imaginary histone octamer core. The known binding sites for HMG-I(Y) on naked forms of this DNA, including the A18 homopolymer tract, are indicated by the molecular stick model portions of the diagram. (B) The same diagrammatic polar view representation model as in panel A except that the binding site for the Elf-1 protein (nt −96 to −85) is indicated by the molecular stick model portion of the diagram.

Directional binding of HMG-I(Y) to the PRRII A18 site on a positioned nucleosome.

Recent solution nuclear magnetic resonance studies of complexes of HMG-I(Y) with a short synthetic DNA substrate demonstrate that the individual DNA-binding domains of the protein (i.e., single A · T hooks) bind to the minor groove of naked A · T-rich DNA with a specific directional orientation (20). We therefore performed experiments to determine whether HMG-I(Y) might likewise bind with a preferred polarity to its DNA recognition sites on the surface of a positioned nucleosome.

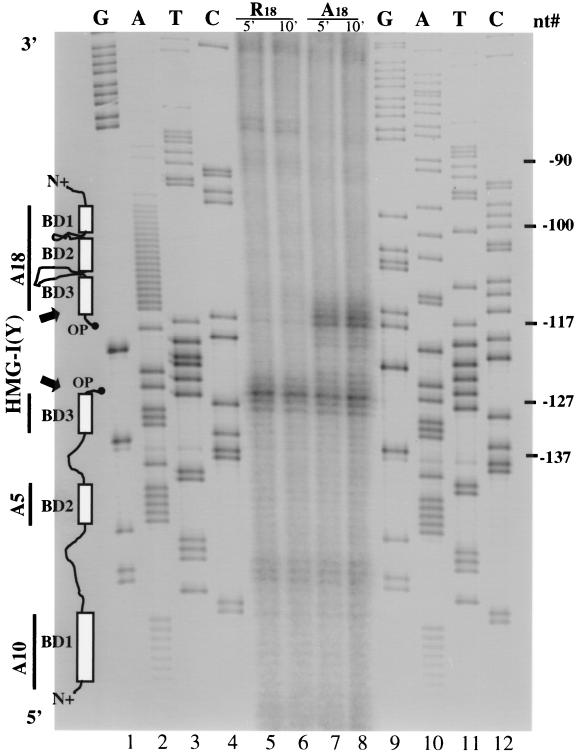

We have recently reported on the use of the chemical cleavage reagent OP-Cu complex (40), covalently attached to the C-terminal end of a modified form of HMG-I(Y), to demonstrate its directional binding to four-way junction DNA in vitro (19). Figure 6 shows the results of experiments employing this cleavage reagent to determine whether HMG-I(Y) binds with a preferred directional orientation to its A18 binding site in the PRRII enhancer when this DNA is positioned on a nucleosome surface. For these experiments, reconstituted PRRII monomer nucleosomes were stoichiometrically bound in vitro by either one [in the case of R18 which, owing to mutation, has only a single strong HMG-I(Y) binding site] or two (in the case of A18, which has two strong binding sites) molecules of an OP-Cu-derivatized HMG-I(Y). These protein-bound nucleosomes were then subjected to in vitro chemical cleavage reactions, and the resulting fragments of 5′-end-labeled DNA were isolated and separated by electrophoresis on a sequencing gel. In these binding studies, the OP-Cu cleavage reagent was attached to a unique cysteine residue introduced at the C-terminal end of a truncated form of the HMG-I(Y) protein (designated HMG-IΔE91) whose negatively charged carboxyl-terminal tail had been removed by in vitro mutagenesis (38). The sites of cleavage observed in these studies, therefore, correspond to the regions of the DNA that are in close proximity to the C-terminal ends of the bound HMG-I(Y) proteins. We have previously demonstrated that the HMG-IΔE91 protein retains the ability to specifically bind to both A · T stretches on naked DNA and its DNA recognition sites on the surface of nucleosomal core particles (38), as well as to four-way junction DNA (19), with the same substrate specificity as the full-length wt HMG-I(Y) protein.

FIG. 6.

Directional binding of HMG-I(Y) to the positioned nucleosome on IL-2Rα promoter DNA in vitro. Cleavage of 5′-end-labeled wt (A18) and mutant (R18) 277-bp promoter DNA fragments (nt −192 to +85) assembled into monomer nucleosomes in the presence of a twofold molar excess of OP-Cu complex-derivatized HMGIΔE91 protein. Lanes 1 to 4, dideoxy sequencing lanes of the wt A18 PRRII promoter DNA in the region of the homopolymer adenine track; lanes 5 and 6, cleavage (5 and 10 min, respectively) of R18 nucleosomal DNA bound by the OP-Cu-HMGIΔE91 protein; lanes 7 and 8, cleavage (5 and 10 min, respectively) of wt A18 nucleosomal DNA bound by the OP-Cu-HMGIΔE91 protein; lanes 9 to 12, dideoxy sequencing lanes of the mutant R18 PRRII promoter DNA in the region of the randomized nucleotides. The diagram on the left indicates the positions of two directionally bound HMG-I(Y) protein molecules on the DNA of the monomer wt A18 nucleosome that are consistent with both protein footprinting and site-directed chemical cleavage data (see text for discussion). The open boxes depict the three independent A · T hook DNA-binding domains (BD-1, -2, -3) of each of the two bound HMG-I(Y) proteins. The vertical lines on the left indicate the sites HMG-I(Y) binding on the naked IL-2Rα (23). The numbers on the right indicate nucleotide locations in the IL-2Rα promoter.

Figure 6 (lanes 7 and 8) demonstrates that the two OP-Cu– HMG-I(Y) protein molecules bound to the reconstituted wt A18 fragment cleave the DNA at two primary sites (at nt −116 or −117 and at ∼nt −127), with each site consisting of several closely spaced cleavage bands. In contrast, only one primary cleavage site (at ∼nt −127) was observed on the reconstituted mutant R18 fragment (lanes 5 and 6). From these results, it is apparent that the common site of OP-Cu cleavage present on both the A18 and R18 reconstitutes is centered around nt −127, near the edge of the centrally positioned nucleosome on both reconstituted 277-bp fragments. In contrast, the additional cleavage site at nt −116 or −117 that is present only on the A18 reconstitute is located on the surface of the centrally positioned core particle about one helical turn of DNA from its edge (Fig. 4A and 8).

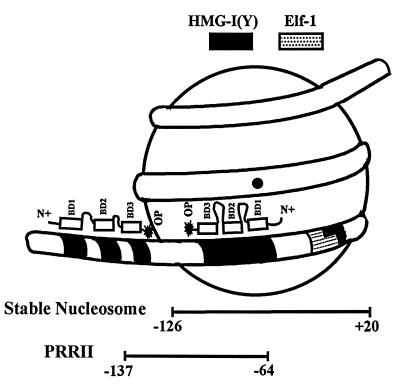

The vertical lines on the left of Fig. 6 indicate in vitro sites of high-affinity binding of HMG-I(Y) on this region of the wt IL-2Rα promoter (23). In this context, it should be recalled that each HMG-I(Y) protein molecule has three independent DNA-binding domains (i.e., BD-1, -2, and -3; also known as A · T hooks) that exhibit intramolecular cooperativity in binding to such high-affinity sites (46). We therefore interpret the cleavage data in Fig. 6, lanes 7 and 8, to indicate that the two molecules of HMG-I(Y) bound to the high-affinity sites on the reconstituted A18 promoter fragment do so in a directional manner with their C termini in a tail-to-tail orientation, with their ends being separated by about 10 or 11 bp. In this polar configuration, one of the HMG-I(Y) proteins would have all three of its DNA-binding domains associated with the wt homopolymer A18 tract on the surface of the nucleosome positioned on the PRRII enhancer with its C-terminal end located near nt −116 and −117 and its amino-terminal end directed toward the transcription initiation start site of the IL-2Rα gene at nt +1 (Fig. 1). The second HMG-I(Y) protein would therefore have its C-terminal end situated near nt −127 and its three DNA-binding domains associated with the other high-affinity binding sites (including the A5 and A10 adenine stretches) situated further 5′ upstream on the promoter DNA. This interpretation of the orientation of binding of the two HMG-I(Y) molecules on the reconstituted A18 promoter fragment is strongly supported by the fact that the single HMG-I(Y) protein molecule bound to the reconstituted R18 fragment cleaves only at nt −127, with no cutting being present at nt −116 and −117 (lanes 5 and 6), a pattern consistent with the fact that HMG-I(Y) is unable to bind to the randomized 18-nucleotide sequence in this mutant PRRII promoter. These data are consistent with the diagram in Fig. 7, illustrating how the two HMG-I(Y) molecules are bound to the reconstituted A18 fragment with its centrally positioned monomer nucleosome and its flanking nonnucleosomal DNA sequences (Fig. 4A).

FIG. 7.

Diagrammatic representation of the centrally positioned nucleosome on a 277-bp fragment of the IL-2Rα promoter bound, in an orientation-specific manner, by two HMG-I(Y) protein molecules. The locations of the relevant HMG-I(Y) and Elf-1 binding sites, along with the position of the PRRII enhancer element, are indicated. The designations and abbreviations for the HMG-I(Y) proteins are as in Fig. 6 (model not to scale).

Transcriptional activation of the IL-2Rα gene alters the chromatin structure of the PRRII enhancer element in vivo.

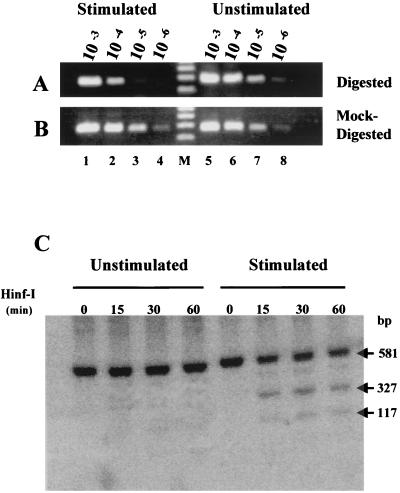

To investigate the possibility that a similarly positioned nucleosome might be present on the PRRII promoter element of the IL-2Rα gene in uninduced human lymphoid in vivo, we employed a restriction enzyme accessibility assay that has previously been successfully used to study positioned nucleosomes in vivo (61). This in vivo chromatin footprinting procedure is based on the observation that packaging of the DNA recognition sequences of restriction enzymes into nucleosomes presents an obstacle to digestion by these nucleases. Restriction enzymes have been extensively used as sensitive probes of nucleosome stability and dynamics both in vitro (44) and in vivo (15, 61). The diagram in Fig. 8 outlines the restriction nuclease accessibility strategy employed in the present in vivo chromatin structure analyses. This experimental approach is greatly facilitated by the results of the prior in vitro nucleosome-positioning studies (Fig. 4A), which indicate that the restriction enzymes HinfI and MseI can be used as accessibility probes for a specifically positioned nucleosome on the PRRII element of the IL-2Rα promoter in vivo. Figure 9 shows the results of an experiment in which nuclei from both unstimulated and mitogenically stimulated Jurkat cells were isolated and then digested with HinfI, a restriction endonuclease that specifically cleaves the PRRII DNA at nt −8. Following HinfI digestion of the nuclei, DNA was isolated and the cleavage products were visualized by a two-step PCR amplification strategy (61). As diagrammed in Fig. 8, a nucleosome positioned on the PRRII element in the nuclei of unstimulated cells in vivo would be expected to prevent cutting of the promoter DNA by the enzyme and the PCR amplification procedure would therefore produce a diagnostic 277-bp fragment. On the other hand, if the PRRII enhancer element were not protected by a nucleosome in vivo (for example, in stimulated cells), the promoter DNA would be more accessible to cleavage by the enzyme and the PCR amplification procedure would be expected to yield a reduced amount of the diagnostic 277-bp product.

FIG. 9.

The in vivo chromatin structure at the position of a predicted nucleosome on the IL-2Rα promoter changes following transcriptional activation of the gene. (A) The restriction enzyme HinfI was used as a probe for chromatin structure to detect a positioned nucleosome on the PRRII enhancer element in either Jurkat cells that had been induced to transcribe the IL-2Rα gene by stimulation for 6 h with PMA plus Con-A (lanes 1 to 4) or unstimulated control cells (lanes 5 to 8). In these experiments (see Fig. 8 and text for details), the PCR products from the first amplification reaction of DNAs isolated from nuclease-treated nuclei of either unstimulated or stimulated cells were serially diluted (lanes 1 and 5, 10−3 dilution; lanes 2 and 6, 10−4 dilution; lanes 3 and 7, 10−5 dilution; lanes 4 and 9, 10−6 dilution), and then each diluted sample was subjected to a second round of PCR amplification using primers PCR #1 and PCR #2. The second PCR would have amplified a 277-bp fragment of the IL-2Rα promoter if the nuclear DNA in the initial nuclease digestion reactions had not been cleaved by the enzyme. Molecular size markers (M) are shown. (B) Control experiments in which nuclei from either unstimulated (lanes 5 to 8) or stimulated (lanes 1 to 4) Jurkat cells were mock digested with HinfI but otherwise treated identically to comparable samples shown in panel A. (C) Southern blot of DNA isolated from the nuclei of uninduced and induced (6 h with PMA plus Con-A) Jurkat cells that had been digested for various lengths of time (15, 30, or 60 min) with HinfI and subsequently processed as described in the text. The membrane was probed by hybridization with a radiolabeled 581-bp BamHI-PstI restriction fragment of the IL-2Rα gene and its promoter (Fig. 1A). The 581-bp band observed in both the uninduced and induced cells was from promoter chromatin that was resistant to HinfI digestion in vivo while the 327- and 117-bp sub-bands resulted from HinfI cleavage of the promoter DNA at nt −8 as a consequence of this site becoming accessible to the enzyme in vivo following transcriptional activation of the IL-2Rα gene (see text for details).

Figure 9 shows the results of these in vivo chromatin accessibility assays using the HinfI enzyme. In this analysis, equal amounts of DNA product from the first PCR amplification derived from unstimulated and stimulated Jurkat cells were serially diluted (103- to 106-fold) and each dilution was then subjected to a second round of amplification using a set of internal PCR primers (e.g., PCR #1 and PCR #2; Fig. 8). The DNA products of this secondary amplification were then electrophoretically separated on an agarose gel and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. As can be seen in Fig. 9A, the 277-bp product that is characteristic of a positioned nucleosome over the PRRII element in vivo is easily detected in DNA from unstimulated Jurkat cells even when the originally amplified sample is diluted 106-fold (lanes 5 to 8). In contrast, markedly diminished amounts of this diagnostic DNA fragment are detected in a comparable DNA dilution series obtained from stimulated Jurkat cells (lanes 1 to 4). A quantitative estimation of the amount of DNA in these amplified mass bands indicated that following transcriptional activation of the IL-2Rα gene in vivo, the chromatin structure of the PRRII promoter element increased its sensitivity to digestion by HinfI approximately 6- to 10-fold (data not shown). In the control experiment shown in Fig. 9B, nuclei from unstimulated (lanes 5 to 8) and stimulated (lanes 1 to 4) cells were mock digested (i.e., not exposed to restriction enzyme) prior to their subsequent analyses, as shown in Fig. 9A. These results demonstrate that there is no significant difference between the unstimulated (lanes 5 to 8) and stimulated (lanes 1 to 4) cells in the amount of the 277-bp promoter DNA fragment produced from the mock-digested nuclei.

In order to verify the PCR-based findings outlined above by a second, independent method, restriction enzyme accessibility was combined with Southern blot hybridization analysis (3) to probe the chromatin structure of the IL-2Rα gene promoter before and after stimulation of the Jurkat cells. The results of one such Southern hybridization analysis are shown in Fig. 9C. In this experiment, the nuclei from uninduced and induced cells were isolated and digested for various lengths of time (15, 30, or 60 min) with HinfI. The HinfI-digested DNA was isolated and double digested overnight with BamHI and PstI restriction enzymes, and the resulting digestion products were separated by electrophoresis and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was probed by hybridization with a radiolabeled 581-bp BamHI-PstI restriction fragment corresponding to nt −472 to +109 of the IL-2Rα gene and its promoter (Fig. 1A). The HinfI cut site at nt −8 in the positioned PRRII nucleosome (Fig. 4C) is located 117 bp from the PstI cut site at nt +109 in the gene coding region (Fig. 1A) and 317 bp from the nearest HinfI site located further 5′ upstream in the promoter region. As a consequence, the 581-bp hybridization band observed in these experiments in both the uninduced and induced cells (Fig. 9C) is derived from a DNA fragment that is resistant to HinfI digestion in vivo. On the other hand, the hybridizing 327- and 117-bp sub-bands that appear in the induced cells (Fig. 9C) result from HinfI cleavage of the IL-2Rα promoter at nt −8 as a consequence of this site becoming accessible to the enzyme in vivo following cellular stimulation. Thus, the results obtained from two entirely different experimental strategies, quantitative PCR amplification and Southern hybridization, are in remarkably good agreement. Together, these data provide direct and persuasive evidence that a nucleosome is positioned on the critical PRRII promoter-enhancer element in unstimulated Jurkat cells and is remodeled, or somehow altered, in vivo following transcriptional activation of the IL-2Rα gene.

DISCUSSION

An extensive body of evidence suggests that even a single properly positioned nucleosome on a crucial regulatory promoter element can inhibit or regulate gene transcription in vivo (reviewed in references 51 and 65). Here we report the first demonstration that the PRRII regulatory element of the human IL-2Rα gene promoter possesses an intrinsic ability to position a stable nucleosome under chromatin reconstitution conditions and have also precisely defined its boundaries in vitro (Fig. 2 to 4). We also present chromatin accessibility data assessed by two different analytical techniques (quantitative PCR analysis and Southern blot hybridization) indicating that a similarly positioned nucleosome is present in vivo on the IL-2Rα promoter in unstimulated Jurkat cells and is disrupted during transcriptional activation of the gene in stimulated cells (Fig. 9). Together, these in vitro and in vivo data intimate that a positioned nucleosome on the PRRII promoter-enhancer element contributes to the maintenance of transcriptional repression of the IL-2Rα gene in unstimulated human lymphocytes. Such repression seems mechanistically reasonable since the location of a nucleosome between approximately nt −126 and +20 on the promoter (Fig. 5) results in the positioning of both the recognition sequence for the Elf-1 protein (Fig. 5B) and the A18 polyadenine binding site for the HMG-I(Y) protein (Fig. 5A) on the surface of a stable core particle.

We have previously reported that transcription from the IL-2Rα promoter is inhibited in vivo if either the Elf-1 recognition sequence or the A18 binding site for HMG-I(Y) are mutated and have also provided evidence that both the Elf-1 and HMG-I(Y) proteins are critically involved in the formation of a multiprotein, enhanceosome-like structure on the promoter that is required for transcription of the gene in living cells (23). Thus, in unstimulated cells, if the positioned nucleosome on the PRRII enhancer element inhibits the ability of either the Elf-1 or the HMG-I(Y) proteins to bind to their recognition sites, no transcription of the IL-2Rα gene would be expected to occur in vivo. Here, we demonstrate in vitro, however, that binding of the HMG-I(Y) protein to its recognition sites on the positioned PRRII nucleosome is apparently not a limiting factor to subsequent transcriptional activation of the promoter but also note that this binding does not lead to an overt disruption of the core particle itself (Fig. 6 and 7). Assuming that the protein exhibits similar binding characteristics in living cells, these results suggest that additional processes besides HMG-I(Y) binding to the core particle must occur in vivo in order to lead to subsequent remodeling of the positioned nucleosome and allow for Elf-1 and the other necessary transcriptions factors to engage in enhanceosome formation on the promoter of the IL-2Rα gene during its transcriptional activation. Nevertheless, the current findings also raise the intriguing and testable hypothesis that the directional binding of the HMG-I(Y) protein on the A18 region of the PRRII enhancer (Fig. 6 and 7) acts as an in vivo stereospecific recognition signal for targeting of the cellular factors or complexes that are necessary participants in the actual nucleosome remodeling process.

Two biological mechanisms for in vivo nucleosome disruption and/or displacement have been extensively investigated and therefore represent likely candidates for possible involvement in this chromatin remodeling process. The first involves the action of large, ATP-requiring, multiprotein complexes called chromatin remodeling machines (7, 60) that function primarily by induction of core particle sliding (16, 28). The other remodeling mechanism involves regulating the acetylation levels of octamer histones, transcription factors, and other components of the basal transcription complex via histone acetyltransferase and deacetylase enzyme complexes (recently reviewed in reference 53). In many cases, an intricate interplay between these two different, but interconnected, types of chromatin modulating systems appears to be involved with regulating gene transcription (reviewed in reference 45). Recent evidence also indicates that targeting of these chromatin modifying complexes to particular chromatin regions can be mediated by specific transcription factors, nuclear receptors, or other accessory factors that possess the ability to bind directly to nucleosomes (5, 59), and it is possible that the directional binding of HMG-I(Y) on the positioned PRRII nucleosome may function in a similar capacity on the IL-2Rα promoter.

Relatively few transcription factors have the intrinsic ability to bind to their recognition sequences when these are incorporated into nucleosomes. This raises the important, but generally unsolved, question of how such inhibitory nucleosomes are specifically marked or targeted for disruption when they are blocking the promoter regions of genes requiring these particular non-core particle binding factors for transcriptional activation. Cooperative binding of disparate transcriptional activators to nucleosomal DNA has been suggested as one solution to this biological problem (1, 42). Transcriptional induction of the IL-2Rα gene, which occurs only in stimulated T lymphocytes, is known to involve the coordinate binding of both constitutive and inducible factors to the gene's promoter (2). Given the present findings, it is appealing to suggest that the initial directional binding of the constitutively expressed architectural factor HMG-I(Y) to the positioned nucleosome on the PRRII enhancer in vivo may facilitate cooperative binding of the lymphoid-myeloid cell-specific transcription factor Elf-1 to this same core particle, thus targeting it for subsequent disruption during in vivo activation of the IL-2Rα promoter. Although resting T cells contain low but detectable amounts of both Elf-1 (58) and HMG-I(Y), the concentrations and states of biochemical modification of these proteins change markedly following lymphocyte activation (14; unpublished observations). Thus, the coordinated increases in concentrations and/or changes in secondary modifications of both the Elf-1 and HMG-I(Y) proteins following activation could provide an essential control point for chromatin remodeling and transcriptional regulation of the IL-2Rα gene in lymphoid cells. We are presently experimentally investigating these possibilities.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported, in part, by the following grants: N.S.F. grant MB-9405332 and N.I.H. grant RO1-GM46352 (both to R.R).

We thank Heiko Ohlenbusch, Strasbourg, France, for the DNA superhelix coordinates shown in Fig. 5.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams C C, Workman J L. Binding of disparate transcriptional activators to nucleosomal DNA is inherently cooperative. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:1405–1421. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.3.1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Algarte M, Lecine P, Costello R, Piet A, Olive D, Imbert J. In vivo regulation of interleukin-2 receptor α gene transcription by the coordinate binding of constitutive and inducible factors in primary T cells. EMBO J. 1995;14:5050–5072. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00188.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ausubel F, Brent R, Kingston R, Moore D, Seidman J, Smith J, Struhl J. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Publishers; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bohnlein E, Lowenthal J W, Siekevitz M, Ballard D W, Franza B R, Greene W C. The same inducible nuclear proteins regulate mitogen activation of both the interleukin-2-receptor-α gene and type I HIV. Cell. 1988;53:827–836. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90099-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bourachot B, Yaniv M, Muchardt C. The activity of mammalian brm/SNF2α is dependent on a high-mobility-group protein I/Y-like DNA binding domain. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:3931–3939. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.6.3931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bustin M, Reeves R. HMG chromosomal proteins: architectural components that facilitate chromatin function. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1996;54:35–100. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60360-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cairns B R. Chromatin remodeling machines: similar motors, ulterior motives. Trends Biochem Sci. 1998;23:20–25. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(97)01160-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chin M, Pellacani A, Wang H, Lin S J, Jain M K, Perrella M A, Lee M-E. Enhancement of serum-response factor-dependent transcription and DNA binding by the architectural transcription factor HMG-I(Y) J Biol Chem. 1998;273:9755–9760. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.16.9755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cross S L, Halden N F, Feinberg B, Wolf J B, Holbrook N J, Wong-Staal F, Leonard W J. Regulation of the human interleukin-2 receptor α chain gene promoter: activation of a nonfunctional promoter by the transactivator gene of HTLV-1. Cell. 1987;49:47–56. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90754-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cross S L, Halden N F, Lenardo M J, Leonard W J. Functionally distinct NF-κB binding sites in the Igκ and IL-2 receptor α chain gene. Science. 1989;244:466–469. doi: 10.1126/science.2497520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dong F, Hansen J C, van Holde K E. DNA and protein determinants of nucleosome positioning on sea urchin 5S rRNA gene sequences in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:5724–5728. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.15.5724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Englander E W, Howard B H. Nucleosome positioning by human Alu elements in chromatin. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:10091–10096. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.17.10091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Englander E W, Howard B H. A naturally occurring T(14)A(II) tract blocks nucleosome formation over the human neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1)-Alu element. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:5819–5823. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.10.5819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giancotti V, Bandiera A, Buratti E, Fusco A, Marzari R, Coles B, Goodwin G H. Comparison of multiple forms of the high mobility group I proteins in rodent and human cells: identification of the human high mobility group I-C protein. Eur J Biochem. 1991;198:211–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1991.tb16003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gregory P D, Barbaric S, Horz W. Restriction nucleases as probes for chromatin structure. In: Becker P, editor. Chromatin protocols. Totowa, N.J: Humana Press; 1999. pp. 417–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamiche A, Sandaltzopoulos R, Gdula D A, Wu C. ATP-dependent histone octamer sliding mediated by the chromatin remodeling complex NURF. Cell. 1999;97:833–842. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80796-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hayes J J, Tullius T D, Wolffe A P. The structure of DNA in a nucleosome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:7405–7409. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.19.7405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hayes J J, Bashkin J, Tullius T D, Wolffe A P. The histone core exerts a dominant constraint on the structure of DNA in a nucleosome. Biochemistry. 1991;30:8434–8440. doi: 10.1021/bi00098a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hill D A, Pedulla M L, Reeves R. Directional binding of HMG-I(Y) on four-way junction DNA and the molecular basis for competitive binding with HMG-1 and histone H1. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:2135–2144. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.10.2135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huth J R, Bewley C A, Nissen M S, Evans J N S, Reeves R, Gronenborn A M, Clore G M. The solution structure of an HMG-I(Y)-DNA complex defines a new architectural minor groove binding motif. Nat Struct Biol. 1997;4:657–665. doi: 10.1038/nsb0897-657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ishida N, Kanamori H, Noma T, Nikaido T, Sabe H, Suzuki A, Shimizu A, Honjo T. Molecular cloning and structure of human interleukin-2 receptor gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 1985;13:7579–7589. doi: 10.1093/nar/13.21.7579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iyer V, Struhl K. Poly(dA:dT), a ubiquitous promoter element that stimulates transcription via its intrinsic DNA structure. EMBO J. 1995;14:2570–2579. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07255.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.John S, Reeves R, Lin J-X, Child R, Leiden J M, Thompson C B, Leonard W J. Regulation of cell-type-specific interleukin-2 receptor α-chain gene expression: potential role of physical interactions between Elf-1, HMG-I(Y), and NF-κB family proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:1786–1796. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.3.1786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.John S, Robbins C M, Leonard W J. An IL-2 response element in the human IL-2 receptor α chain promoter is a composite element that binds Stat5, Elf-1, HMG-I(Y) and a GATA family protein. EMBO J. 1996;15:5627–5635. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.John S, Vinkemeier U, Soldaini E, Darnell J E, Jr, Leonard W J. The significance of tetramerization in promoter recruitment by Stat5. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:1910–1918. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.3.1910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson K R, Lehn D A, Reeves R. Alternative processing of mRNAs encoding mammalian high mobility group proteins HMG-I and HMG-Y. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:2114–2123. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.5.2114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kornberg R D, LaPointe J W, Lorch Y. Preparation of nucleosomes and chromatin. Methods Enzymol. 1989;170:3–14. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(89)70039-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Langst G, Bonte F J, Corona D F V, Becker P B. Nucleosome movement by CHRAC and ISWI without disruption or trans-displacement of the histone octamer. Cell. 1999;97:843–852. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80797-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lecine P, Algarte M, Rameil P, Beadling C, Bucher P, Nabholz M, Imbert J. Elf-1 and Stat5 bind to a critical element in a new enhancer of the human interleukin-2 receptor alpha gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:6829–6840. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.12.6829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leonard W J. The interleukin-2 receptor: structure, function, intercellular messengers and molecular regulation. In: Waxman J, Balkwill F, editors. Interleukin-2. Oxford, England: Blackwell Scientific Publications Ltd.; 1992. pp. 29–46. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin B B, Cross S L, Halden N F, Roman D G, Toledano M B, Leonard W J. Delineation of the enhancer-like positive regulatory element in the interleukin-2 receptor α-chain gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:850–853. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.2.850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin J X, Leonard W J. Signaling from the IL-2 receptor to the nucleus. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 1997;8:313–332. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(97)00021-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lowary P T, Widom J. Nucleosome packaging and nucleosome positioning of genomic DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:1183–1188. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.4.1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luger K, Mader A W, Richmond R K, Sargent D E, Richmond T. Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8 Å resolution. Nature. 1997;389:251–260. doi: 10.1038/38444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meersseman G, Pennings S, Bradbury E M. Chromatosome positioning on assembled long chromatin: linker histones affect nucleosome placement on 5S rDNA. J Mol Biol. 1991;220:89–100. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90383-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nakamura Y, Russell S M, Mess S A, Friedmann M, Erdos M, Francois C, Jacques Y, Adelstein S, Leonard W J. Heterodimerization of the IL-2 receptor beta- and gamma-chain cytoplasmic domains is required for signalling. Nature. 1994;369:330–333. doi: 10.1038/369330a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nelson B H, Willerford D M. Biology of the interleukin-2 receptor. Adv Immunol. 1998;70:1–81. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60386-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nissen M S, Reeves R. Changes in superhelicity are introduced into closed circular DNA by binding of high mobility group protein I(Y) J Biol Chem. 1995;270:4355–4360. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.9.4355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nissen M S, Langan T A, Reeves R. Phosphorylation by cdc2 kinase modulates DNA binding activity of HMG-I nonhistone chromatin protein. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:19945–19952. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pan C Q, Feng J-A, Finkel S E, Landgraf R, Sigman D, Johnson R. Structure of the Escherichia coli Fis-DNA complex probed by protein conjugated with 1,10-phenanthroline copper(II) complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:1721–1725. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.5.1721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Paranjape S M, Kamakaka R T, Kadonaga J T. Role of chromatin structure in the regulation of transcription by RNA polymerase II. Annu Rev Biochem. 1994;63:265–297. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.001405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pazin M J, Sheridan P L, Canno K, Cao Z, Keck J G, Kadonaga J T, Jones K A. NF-κB-mediated chromatin reconfiguration and transcriptional activation of the HIV-1 enhancer in vitro. Genes Dev. 1996;10:37–49. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pennings S, Meersseman G, Bradbury E M. Mobility of positioned nucleosomes of 5S rDNA. J Mol Biol. 1991;220:101–110. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90384-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Polach K J, Widom J. Restriction enzymes as probes of nucleosome stability and dynamics. Methods Enzymol. 1999;304:278–298. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)04017-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pollard K J, Peterson C L. Chromatin remodeling: a marriage between two families? Bioessays. 1998;20:771–780. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199809)20:9<771::AID-BIES10>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reeves R, Nissen M. The A-T-rich DNA-binding domain of high mobility group protein HMG-I: a novel peptide motif for recognizing DNA structure. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:8573–8582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reeves R, Nissen M. Interaction of high mobility group-I (Y) nonhistone proteins with nucleosome core particles. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:21137–21146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reeves R, Wolffe A P. Substrate structure influences binding of the non-histone protein HMG-I(Y) to free and nucleosomal DNA. Biochemistry. 1996;35:5063–5073. doi: 10.1021/bi952424p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rusterholz C, Henrioud P C, Nabholz M. Interleukin-2 (IL-2) regulates the accessibility of the IL-2-responsive enhancer in the IL-2 receptor alpha gene to transcription factors. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:2681–2689. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.4.2681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sharfe N, Dadi H K, Shahar M, Roifman C M. Human immune disorder arising from mutation of the alpha chain of the interleukin-2 receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3168–3171. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Simpson R T. Nucleosome positioning: occurrence, mechanisms, and functional consequences. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1991;40:143–184. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60841-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Soldaini E, Pla M, Beermann F, Espel E, Corthesy P, Barange S, Waanders G A, MacDonald H R, Nabholz M. Mouse interleukin-2 receptor α gene expression: delimitation of cis-acting regulatory elements in transgenic mice and by mapping of DNase-I hypersensitive sites. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:10733–10742. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.18.10733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Struhl K. Histone acetylation and transcriptional regulatory mechanisms. Genes Dev. 1998;12:599–606. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.5.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thanos D, Maniatis T. Virus inducton of human IFNβ gene expression requires the assembly of an enhanceosome. Cell. 1995;83:1091–1100. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90136-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thiriet C, Hayes J J. Functionally relevant histone-DNA interactions extend beyond the classically defined nucleosome core region. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:21352–21358. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.33.21352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thoma F. Nucleosome positioning. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1130:1–19. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(92)90455-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Thompson C B, Wang C-Y, Ho I-C, Bohjanen P R, Petryniak B, June C H, Miesfeldt S, Zhang L, Nabel G J, Karpinski B, Leiden J M. cis-acting sequences required for inducible interleukin-2 enhancer function bind a novel Ets-related protein, Elf-1. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:1043–1053. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.3.1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ura K, Hayes J J, Wolffe A P. A positive role for nucleosome mobility in the transcriptional activity of chromatin templates: restriction by linker histones. EMBO J. 1995;14:3752–3765. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00045.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Utley R T, Ikeda K, Grant P A, Cote J, Steger D J, Eberharter A, John S, Workman J L. Transcriptional activators direct histone acetyltransferase complexes to nucleosomes. Nature. 1998;394:498–502. doi: 10.1038/28886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Varga-Weisz P D, Becker P B. Chromatin-remodeling factors: machines that regulate? Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1998;10:346–353. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(98)80010-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ward S, Hernandez-Hoyos G, Chen F, Reeves R, Rothenberg E V. Chromatin remodeling of the interleukin-2 gene: distinct alterations in the proximal versus distal enhancer regions. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:2923–2934. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.12.2923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Werner M H, Clore M, Fisher C L, Fisher R J, Trinh L, Shiloach K, Gronenborn A M. The solution structure of the human ETS1-DNA complex reveals a novel mode of binding and true side chain intercalation. Cell. 1995;83:761–771. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90189-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Widlund H R, Cao H, Simonsson S, Magnusson E, Simonsson T, Nielsen P E, Kahn J D, Crothers D M, Kubista M. Identification and characterization of genomic nucleosome-positioning sequences. J Mol Biol. 1997;267:807–817. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.0916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Willerford D M, Chen J, Ferry J, Davidson L, Ma A, Alt F W. Interleukin-2 receptor α chain regulates the size and content of the peripheral lymphoid compartment. Immunity. 1995;3:521–530. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90180-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wolffe A P. Chromatin: structure and function. 2nd ed. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wolffe A P, Hayes J J. Transcription factor interactions with model nucleosomal templates. Methods Mol Genet. 1993;2:314–320. [Google Scholar]