Abstract

Background

Primary membranous nephropathy (PMN) is a common cause of nephrotic syndrome in adults. Without treatment, approximately 30% of patients will experience spontaneous remission and one third will have persistent proteinuria. Approximately one‐third of patients progress toward end‐stage kidney disease (ESKD) within 10 years. Immunosuppressive treatment aims to protect kidney function and is recommended for patients who do not show improvement of proteinuria by supportive therapy, and for patients with severe nephrotic syndrome at presentation due to the high risk of developing ESKD. The efficacy and safety of different immunosuppressive regimens are unclear. This is an update of a Cochrane review, first published in 2004 and updated in 2013.

Objectives

The aim was to evaluate the safety and efficacy of different immunosuppressive treatments for adult patients with PMN and nephrotic syndrome.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Register of Studies up to 1 April 2021 with support from the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Information Specialist using search terms relevant to this review. Studies in the Register were identified through searches of CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and EMBASE, conference proceedings, the International Clinical Trials Register (ICTRP) Search Portal and ClinicalTrials.gov.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) investigating effects of immunosuppression in adults with PMN and nephrotic syndrome were included.

Data collection and analysis

Study selection, data extraction, quality assessment, and data synthesis were performed using Cochrane‐recommended methods. Summary estimates of effect were obtained using a random‐effects model, and results were expressed as risk ratios (RR) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) for dichotomous outcomes, and mean difference (MD) and 95% CI for continuous outcomes. Confidence in the evidence was assessed using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach.

Main results

Sixty‐five studies (3807 patients) were included. Most studies exhibited a high risk of bias for the domains, blinding of study personnel, participants and outcome assessors, and most studies were judged unclear for randomisation sequence generation and allocation concealment.

Immunosuppressive treatment versus placebo/no treatment/non‐immunosuppressive treatment

In moderate certainty evidence, immunosuppressive treatment probably makes little or no difference to death, probably reduces the overall risk of ESKD (16 studies, 944 participants: RR 0.59, 95% CI 0.35 to 0.99; I² = 22%), probably increases total remission (complete and partial) (6 studies, 879 participants: RR 1.44, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.97; I² = 73%) and complete remission (16 studies, 879 participants: RR 1.70, 95% CI 1.05 to 2.75; I² = 43%), and probably decreases the number with doubling of serum creatinine (SCr) (9 studies, 447 participants: RR 0.46, 95% CI 0.26 to 0.80; I² = 21%). However, immunosuppressive treatment may increase the number of patients relapsing after complete or partial remission (3 studies, 148 participants): RR 1.73, 95% CI 1.05 to 2.86; I² = 0%) and may lead to a greater number experiencing temporary or permanent discontinuation/hospitalisation due to adverse events (18 studies, 927 participants: RR 5.33, 95% CI 2.19 to 12.98; I² = 0%). Immunosuppressive treatment has uncertain effects on infection and malignancy.

Oral alkylating agents with or without steroids versus placebo/no treatment/steroids

Oral alkylating agents with or without steroids had uncertain effects on death but may reduce the overall risk of ESKD (9 studies, 537 participants: RR 0.42, 95% CI 0.24 to 0.74; I² = 0%; low certainty evidence). Total (9 studies, 468 participants: RR 1.37, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.82; I² = 70%) and complete remission (8 studies, 432 participants: RR 2.12, 95% CI 1.33 to 3.38; I² = 37%) may increase, but had uncertain effects on the number of patients relapsing, and decreasing the number with doubling of SCr. Alkylating agents may be associated with a higher rate of adverse events leading to discontinuation or hospitalisation (8 studies 439 participants: RR 6.82, 95% CI 2.24 to 20.71; I² = 0%). Oral alkylating agents with or without steroids had uncertain effects on infection and malignancy.

Calcineurin inhibitors (CNI) with or without steroids versus placebo/no treatment/supportive therapy/steroids

We are uncertain whether CNI with or without steroids increased or decreased the risk of death or ESKD, increased or decreased total or complete remission, or reduced relapse after complete or partial remission (low to very low certainty evidence). CNI also had uncertain effects on decreasing the number with a doubling of SCr, temporary or permanent discontinuation or hospitalisation due to adverse events, infection, or malignancy.

Calcineurin inhibitors (CNI) with or without steroids versus alkylating agents with or without steroids

We are uncertain whether CNI with or without steroids increases or decreases the risk of death or ESKD. CNI with or without steroids may make little or no difference to total remission (10 studies, 538 participants: RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.15; I² = 53%; moderate certainty evidence) or complete remission (10 studies, 538 participants: RR 1.15, 95% CI 0.84 to 1.56; I² = 56%; low certainty evidence). CNI with or without steroids may increase relapse after complete or partial remission. CNI with or without steroids had uncertain effects on SCr increase, adverse events, infection, and malignancy.

Other immunosuppressive treatments

Other interventions included azathioprine, mizoribine, adrenocorticotropic hormone, traditional Chinese medicines, and monoclonal antibodies such as rituximab. There were insufficient data to draw conclusions on these treatments.

Authors' conclusions

This updated review strengthened the evidence that immunosuppressive therapy is probably superior to non‐immunosuppressive therapy in inducing remission and reducing the number of patients that progress to ESKD. However, these benefits need to be balanced against the side effects of immunosuppressive drugs. The number of included studies with high‐quality design was relatively small and most studies did not have adequate follow‐up. Clinicians should inform their patients of the lack of high‐quality evidence.

An alkylating agent (cyclophosphamide or chlorambucil) combined with a corticosteroid regimen had short‐ and long‐term benefits, but this was associated with a higher rate of adverse events.

CNI (tacrolimus and cyclosporin) showed equivalency with alkylating agents however, the certainty of this evidence remains low.

Novel immunosuppressive treatments with the biologic rituximab or use of adrenocorticotropic hormone require further investigation and validation in large and high‐quality RCTs.

Plain language summary

Immunosuppressive treatment for adults with idiopathic membranous nephropathy

What is the issue?

Primary membranous nephropathy (PMN) is an autoimmune disease, where the body's immune system attacks the kidneys. The term "primary" is used to describe membranous nephropathy that is not caused by another disease in the body. PMN is a leading cause of nephrotic syndrome in adults. Nephrotic syndrome is a condition, where the membrane of the kidney is damaged and becomes permeable for proteins. Primary membranous nephropathy is diagnosed through findings in a kidney biopsy and the presence of nephrotic syndrome.

PMN is not harmful in about one‐third of patients, who will have a spontaneous "complete remission", which means that the disease will resolve by itself. However, about another one third will experience spontaneous remission but will have some protein in the urine that continues with normal kidney function. These patients usually only require supportive treatments that do not interact with the immune system. Without treatment, about 15% to 50% of patients progress to end‐stage kidney disease (ESKD) within 10 years.

In some patients, PMN can be severe or continues to get worse even after using 6 months of supportive treatments. In these patients, extra treatment that dampens the activity of the immune system may be used to reduce damage to the kidney. It is not clear which of these treatment(s) is the most helpful and what side effects can occur. Therefore, the duration and intensity of immunosuppressive treatment need to be balanced against possible side effects. There are different classes of drugs used in immunosuppressive therapy. These drugs may or may not be combined with corticosteroids (drugs based on the body's stress response hormone cortisol).

What did we do?

We searched the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant specialised register up to 1 April 2021. We have combined studies to compare different treatment regimens with immunosuppressive therapy to assess which treatments help to treat patients with PMN and nephrotic syndrome with the least side effects.

What did we find?

This review identified sixty‐five studies with 3807 patients. Different types of immunosuppressive treatment include alkylating agents (cyclophosphamide and chlorambucil), calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus and cyclosporine), antimetabolites (mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine), biologicals (e.g. rituximab) and adrenocorticotropic hormone. These drugs may or may not be combined with corticosteroids (e.g. prednisone), which also suppresses the immune system. After combining the results of available studies together, we found that compared with no treatment, supportive treatment or steroids alone, the use of immunosuppressive treatment probably reduced the number of patients who progressed to ESKD by about 40% and increased the number of patients that achieved complete remission. However, immunosuppressive treatment may lead to more adverse events, which can cause treatment to be stopped or lead to the patients needing to go to hospital.

The different drugs that can be used in the immunosuppressive treatment were also examined in our review. We found that alkylating agents probably increases complete remission but may lead to more adverse events. We are uncertain whether alkylating agents increase infection or cancer. Based on the currently available evidence, the effectiveness of using calcineurin inhibitors is still unclear, but there is low certainty of the evidence, that CNI may lead to similar remission rates compared to alkylating agents.

Furthermore, other treatment options such as mycophenolate mofetil, adrenocorticotropic hormone, rituximab and others have only been examined in a few studies. There is not enough data to draw final conclusions on the use of these treatments in adults with PMN and nephrotic syndrome.

Conclusions

The treatment of patients with PMN and nephrotic syndrome with immunosuppressive therapy compared to no treatment or supportive therapy alone probably protects the kidney but may increase side effects. A combination of immunosuppressive therapy with steroids may decrease disease activity and the use of alkylating agent combined with steroids probably has the short‐term and long‐term benefits of limiting damage to the kidney. Other therapies such as calcineurin inhibitors, mycophenolate mofetil, rituximab and adrenocorticotropic hormone have less certainty regarding their safety and effectiveness from these studies.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Membranous nephropathy is the most common cause of primary nephrotic syndrome in adults, and particularly affects elderly patients (Cameron 1996; Hofstra 2012; Vendemia 2001). Approximately 75% of membranous nephropathy cases are considered primary/idiopathic (Abe 1986) with the other 25% due to secondary causes, such as infections, autoimmune diseases, certain medications, or malignant diseases. Primary membranous nephropathy (PMN) shows a benign or indolent course in about one‐third of patients, with a high rate of spontaneous remission in about 30% of patients (Polanco 2010). Approximately one third develops nephrotic syndrome but maintain normal kidney function. Despite this, 15% to 50% of patients who do not receive immunosuppressive treatment progress to end‐stage kidney disease (ESKD) within 10 years (Deegens 2005; Ponticelli 2010; Waldman 2009). Recent findings of anti‐phospholipase‐A2‐receptor‐antibodies (anti‐PLA2R) (Beck 2009) and anti‐thrombospondin type‐1 domain‐containing protein 7A‐antibodies (anti‐THSD7A) (Tomas 2014) have improved understanding of the autoimmune pathophysiology of PMN. PMN is caused by the subepithelial formation of immune complex deposits in the kidney's glomerular basement membrane (GBM) (Lai 2015). The exact mechanisms behind this remain unclear, however, there are a number of presumptive hypotheses. Firstly, systemically pre‐formed immune‐complexes may deposit in the GBM, suggesting a similar pathophysiological mechanism as in lupus‐associated nephritis (Lai 2015). Secondly, circulating antigens (such as during infection) might be targeted by antibodies, thus forming immune complexes that deposit in this site. this has especially been observed in infection‐related (i.e. secondary) forms of membranous nephropathy, such as during infection with hepatitis B virus (Bhimma 2004; Lai 2000; Lai 2015). Thirdly, based on Heymann's model of nephritis (Heymann 1959), podocyte‐antigens (such as megalin) may lead to binding of autoantibodies to the GBM's podocytes which cause the subepithelial deposits that are present in PMN (Tramontano 2006). However, thus far, this connection has not been clearly established through the extraction of anti‐megalin‐antibodies in PMN. Finally, the complement system and genetic factors might contribute to the autoimmune aetiology of PMN. So far, two associated genomic loci have been identified: chromosome 2q24 encodes for the anti‐PLA2R‐receptor auto‐antibody and chromosome 6p21 encodes for HLADQA1, which might play pivotal roles in the pathogenesis of PMN (Bullich 2014; Stanescu 2011).

In a kidney biopsy, diagnosis of membranous nephropathy can be established by the presence of subepithelial immune deposits. In light‐microscopy, a thickened, prominent GBM with "spikes" (local thickening of the membrane due to matrix reactions to the deposits) may indicate PMN, however electron microscopy and immunofluorescence are superior techniques in establishing the diagnosis of PMN. Immunofluorescence may show staining for PLA2R, complement (C3) and immunoglobulin (Fogo 2015; Lai 2015), whereas electron microscopy allows pathological staging of PMN into four stages according to the classification first suggested by Churg and Ehrenreich (Ehrenreich 1976). Electron microscopy may show "extensive foot process effacement and subepithelial deposits with increasing matrix spike reaction with advancing disease. As the disease progresses, an increase in matrix production can envelop these deposits and lead to a "laddering appearance" (Fogo 2015). The diagnosis of PMN is one of exclusion and secondary causes of membranous nephropathy must be ruled out.

Description of the intervention

Several immunosuppressive treatments have been used to treat patients with PMN and nephrotic syndrome, including corticosteroids, alkylating agents (chlorambucil and cyclophosphamide (CPA)), azathioprine (AZA), and mizoribine. More recently, other treatments such as calcineurin inhibitors (CNI) (cyclosporine (CSA) and tacrolimus (TAC)), mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), Tripterygium wilfordii (a traditional Chinese immunosuppressive medicine), and therapeutic approaches such as biologics (rituximab and eculizumab) and high dose gamma‐globulin have also been considered for PMN. However, due to the uncertain risk‐benefit profile of immunosuppressive treatment and the lack of definite evidence on altering the long‐term course of the disease, the most appropriate therapy remains unclear.

Currently, "Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes" (KDIGO) guidelines suggest supportive therapy for all patients with PMN and immunosuppressive therapy should be considered only in patients with urinary protein exceeding 3.5 g/24 hours and eGFR ≤ 60 mL/min/1.73 m², or in patients with one risk for disease progression is present. Initial suggested therapy consists of a six‐month course of alternating monthly cycles of oral and intravenous (IV) corticosteroids and CPA or TAC or rituximab as alternatives (KDIGO 2020).

How the intervention might work

Given the autoimmune aetiology of PMN, immunosuppressive treatment is used to decrease the overall activity of the immune system, leading to reduced damage to the kidneys. Most immunosuppressive drugs suppress the immune system more broadly, whereas some therapies such as rituximab aim to target specific parts of the immune system.

Why it is important to do this review

In the 2004 Cochrane review (Schieppati 2004), 19 studies with 1025 participants were included. This review found that immunosuppressive treatments could increase complete or partial remission. However, the long‐term effects of immunosuppressive treatments on definite endpoints such as death (any cause) or the prevention of ESKD could not be demonstrated. Immunosuppressive treatments were found to lead to a significantly higher risk of severe adverse events.

In the 2014 update of the Cochrane review (Chen 2014), 39 studies with 1825 participants overall were included, which further strengthened the certainty of the evidence. New treatments have more recently been investigated in randomised controlled trials (RCTs) for the treatment of PMN, and studies have reported on the use of new therapies such as monoclonal antibodies in patients with PMN and traditional Chinese medicine (Shenqi particles) (Chen 2013e). Most notably, rituximab (GEMRITUX 2017; MENTOR 2015) have been tested in studies for PMN.

Objectives

Our objective was to assess the evidence and evaluate the safety and efficacy of immunosuppressive treatments for adult patients with PMN and nephrotic syndrome. The following questions relating to the management of PMN and nephrotic syndrome were addressed:

Is immunosuppressive therapy superior to non‐immunosuppressive therapy?

If so, which immunosuppressive agent/s is the most effective and safe in treating patients with IMN and nephrotic syndrome?

What routes of administration and duration of therapy should be used?

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included RCTs that assessed the effects of immunosuppressive treatments in adult patients with IMN and nephrotic syndrome.

Types of participants

Inclusion criteria

Adults (at least 18 years of age)

Diagnosis of PMN, established by kidney biopsy (and possibly be further proven by detection of anti‐PLA2R‐ or anti‐THSD7‐antibodies). Prior to 2009, membranous nephropathy was determined by kidney biopsy. Other underlying causes of membranous nephropathy were ruled out clinically to establish the diagnosis of primary membranous nephropathy

Diagnosis of nephrotic syndrome as defined by the authors in each study. In studies that included > 50% non‐nephrotic patients, analyses were restricted to nephrotic patients only. In the absence of an explicit definition of nephrotic syndrome, the cut‐off value of proteinuria above 3.5 g/24 hours was used.

Exclusion criteria

Secondary forms of membranous nephropathy were excluded. We also excluded studies where it was impossible to identify how many adult PMN patients had nephrotic syndrome.

Types of interventions

We considered the following immunosuppressive treatments: corticosteroids, alkylating agents (chlorambucil and CPA), CNI (CSA and TAC), sirolimus, MMF, and synthetic ACTH. Other less commonly studied immunosuppressive regiments such as Tripterygium wilfordii (a traditional Chinese immunosuppressive medicine); Shenqi particles (a traditional Chinese immunosuppressive medicine), leflunomide, AZA, mizoribine, methotrexate, and levamisole were also investigated. Furthermore, high dose gamma‐globulin and biologics (rituximab and eculizumab) were included in this review.

Non‐immunosuppressive treatments were excluded: drugs aimed to reduce proteinuria through inhibition of the renin‐angiotensin system (e.g. angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEi) or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) or aliskiren); drugs aimed to correct dyslipidaemia (e.g. statins); anti‐aldosterone drugs (e.g. spironolactone); nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (e.g. indomethacin).

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Death (any cause)

ESKD (requiring kidney replacement therapy) at the last follow‐up

Complete or partial (total) remission, complete remission alone, and partial remission alone at different time points and at the last follow‐up.

Complete and partial remission of nephrotic syndrome was assessed according to the definition provided in each study. In the absence of an explicit definition, complete remission was defined as proteinuria < 0.3 g/24 hours and with a normal or stable serum creatinine (SCr) (within 50% of baseline value). In the absence of an explicit definition, partial remission was defined as a reduction in proteinuria by at least 50% and remaining between 0.3 to 3.5 g/24 hours with a normal or stable SCr (within 50% of baseline value).

Secondary outcomes

Relapse (recurrence of disease) after initial remission

100% increase (doubling) in SCr from baseline at different time points and at the last follow‐up

Quality of Life (as measured by study investigators).

The following side effects (toxicity) of treatments were considered.

-

Adverse events (as defined by the study investigators)

Temporary or permanent discontinuation or hospitalisation due to adverse events

Infection

Malignancy.

The following continuous kidney function outcomes were analysed at the end of follow‐up.

SCr (μmol/L)

Serum albumin (g/L)

Glomerular filtration rate (GFR) (mL/min/1.73 m²)

Proteinuria (g/24 hours)

50% increase in SCr from baseline at different time points and at the last follow‐up.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Register of Studies up to 1 April 2021 through contact with the Information Specialist using search terms relevant to this review. The Register contains studies identified from the following sources.

Monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL)

Weekly searches of MEDLINE OVID SP

Searches of kidney and transplant journals, and the proceedings and abstracts from major kidney and transplant conferences

Searching of the current year of EMBASE OVID SP

Weekly current awareness alerts for selected kidney and transplant journals

Searches of the International Clinical Trials Register (ICTRP) Search Portal and ClinicalTrials.gov.

Studies contained in the Register are identified through searches of CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and EMBASE based on the scope of Cochrane Kidney and Transplant. Details of search strategies, as well as a list of handsearched journals, conference proceedings and current awareness alerts, are available on the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant website.

See Appendix 1 for search terms used in strategies for this review.

Searching other resources

Reference lists of review articles, relevant studies, and clinical practice guidelines.

Handsearching proceedings of major rheumatology conferences.

Contacting relevant individuals/organisations seeking information about unpublished or incomplete studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

A search was performed to identify relevant studies. In this update, study selection was done by two authors (GW, TvG). The titles and abstracts of retrieved citations, and where necessary the full‐text articles, were independently evaluated by two authors (GW, TvG). Disagreements were resolved by consulting a third author (DT). Where duplicated reports of the same study were confirmed, the initial first complete publication was selected (the index publication) and was the primary data source, but any other additional prior or subsequent reports were also included. These additional prior or subsequent reports containing supplementary outcome data (such as longer‐term follow‐up, or different outcomes) also contributed to the review and meta‐analysis.

Data extraction and management

Data extraction was carried out independently by two authors (GW, TvG) using standard data extraction forms. Studies reported in non‐English language journals were translated before assessment. In case of duplicates, reports were grouped together and the publication with the most complete data was included. When relevant outcomes were only published in earlier versions, these data were used. Any differences between published versions were highlighted. A third author (DT) resolved these discrepancies. If needed, further details were requested by written correspondence to principal investigators and any relevant information obtained in this manner was included in this review. We also contacted principal investigators for missing data whenever necessary.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The following items were independently assessed by two authors (GW, TvG) using the risk of bias assessment tool (Higgins 2011) (see Appendix 2). Publication bias was especially investigated for the comparison of immunosuppressive treatments versus no immunosuppression.

Was there adequate sequence generation (selection bias)?

Was allocation adequately concealed (selection bias)?

-

Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented during the study?

Participants and personnel (performance bias)

Outcome assessors (detection bias)

Were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed (attrition bias)?

Are reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting (reporting bias)?

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at risk of bias?

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous outcomes (death, ESKD, total remission, complete remission, partial remission, relapse, doubling of SCr, 50% increase in SCr, adverse events, infection, malignancy) results were expressed as risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). RR was the selected effect measure because it describes the multiplication of risk and is relatively easy to understand, is a bounded measure of effect that provides a consistent estimate of effect.

Continuous data

When a continuous scale of measurement was used (eGFR, SCr, 24‐hour proteinuria, quality of life), the mean difference (MD) with 95% CI was chosen or the standardised mean difference (SMD) was considered if a different scale was adopted or SMDs were reported in a publication.

Unit of analysis issues

In studies with multiple intervention arms we considered the following:

If different classes (for example, CPA, or MMF versus steroids), we included each treatment group in a separate meta‐analysis, ensuring that we did not include outcome data for the control group participants more than once in a single meta‐analysis

If interventions were the same therapy (for example Mizoribine 150 mg once/day versus Mizoribine 50 mg three times/day), we compared the two intervention arms with each other as in the study.

Dealing with missing data

Missing data were assessed for each included study. For missing participants due to drop‐out, intention‐to‐treat analyses (ITT) were performed if the data were reported elsewhere or were provided by principal investigators in response to our requests for additional information. For missing statistics such as standard deviations, these studies were not considered in the meta‐analysis unless the missing data could be appropriately imputed using methods recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration. We included missing participants in the analyses. Issues of missing data and imputation methods (for example last‐observation‐carried‐forward) were critically appraised (Higgins 2011).

In one study that reported median and interquartile ranges (GEMRITUX 2017), we calculated mean and standard deviations, using the formula suggested by Hozo 2005 for larger sample sizes, given the sample sizes of both groups in the study exceeded 25. We used the Vassarstats calculator (http://vassarstats.net/median_range.html), which is based on the Hozo formula.

We also contacted principal investigators to request missing data where possible.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We first assessed the heterogeneity by visual inspection of the forest plot, by examining the direction of the effect estimates and the overlap of confidence intervals. Heterogeneity was then further assessed by using the Chi² test, with a p‐value less than 0.1 used to denote statistical significance, and with the I² statistic calculated to measure the proportion of total variation in the estimates of treatment effect that was due to heterogeneity rather than chance (Higgins 2011). A guide to the interpretation of I² values (Higgins 2003) is as follows.

0% to 40%: might not be important

30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity

50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity

75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity.

The importance of the observed value of I² depends on the magnitude and direction of treatment effects and the strength of evidence for heterogeneity (e.g. P‐value from the Chi² test, or a confidence interval for I²).

Assessment of reporting biases

We planned to assess for publication bias for the primary outcomes. We made every attempt to minimise publication bias by including unpublished studies (for example, including abstract‐only publications and searching online trial registries). To assess publication bias we used funnel plots of the log odds ratio (OR) (effect versus standard error of the effect size) when a sufficient number of studies were available (10 studies or more) (Harbord 2009; Higgins 2011). For the analysis and interpretation of the funnel plots, other reasons for asymmetry besides publication bias were considered (differences in methodological quality and true heterogeneity in intervention effects). However, the limited amount of study data did not enable meaningful interpretation.

Data synthesis

Data were abstracted from individual studies and then pooled for summary estimates using a random‐effects model. The random‐effects model was chosen because it provides a more conservative estimate of effect in the presence of known or unknown potential heterogeneity (Higgins 2011).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Subgroup analyses are hypothesis‐generating rather than hypothesis testing and should be treated with caution. Subgroup analysis was used to explore possible sources of heterogeneity (e.g. participants and interventions). Heterogeneity among participants could be related to age and disease severity. Heterogeneity in treatments could be related to the route, dose, and duration of therapies in the studies. Subgroup analysis was also performed to explore the following covariates: the language of publication, source of funding and sample size calculation as well as anti‐PLA2R‐levels. However, there was limited data reported to undertake these subgroup analyses, in particular the reporting of anti‐PLA2R‐levels.

Sensitivity analysis

We considered the following sensitivity analyses in order to explore the influence of the following factors.

Repeating the analysis excluding unpublished studies or low‐quality studies based on the assessment of the risk of bias

-

Repeating the analysis excluding studies that were of insufficient follow‐up for the primary outcome

Death: 10‐year follow‐up

ESKD:10‐year follow‐up

Complete remission:2‐year follow‐up

Repeating the analysis excluding any very long or very large study to determine the extent to which they unduly influenced the results.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We presented the main results of the review in 'Summary of findings' tables. These tables present key information concerning the quality of the evidence, the magnitude of the effects of the interventions examined, and the sum of the available data for the main outcomes (Schunemann 2011a). The 'Summary of findings' tables also includes an overall grading of the evidence related to each of the main outcomes using the GRADE (Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) approach (GRADE 2008; GRADE 2011). The GRADE approach defines the quality of a body of evidence as to the extent to which one can be confident that an estimate of effect or association is close to the true quantity of specific interest. The quality of a body of evidence involves consideration of the within‐trial risk of bias (methodological quality), directness of evidence, heterogeneity, the precision of effect estimates and risk of publication bias (Schunemann 2011b). We presented the following outcomes in the 'Summary of findings' tables.

Death

ESKD

Total remission (complete or partial)

Complete remission

Recurrence (relapse) of disease

Doubling of SCr from baseline

-

Adverse events

Temporary or permanent discontinuation or hospitalisation due to adverse events

Infection

Malignancy

Results

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of studies awaiting classification; Characteristics of ongoing studies.

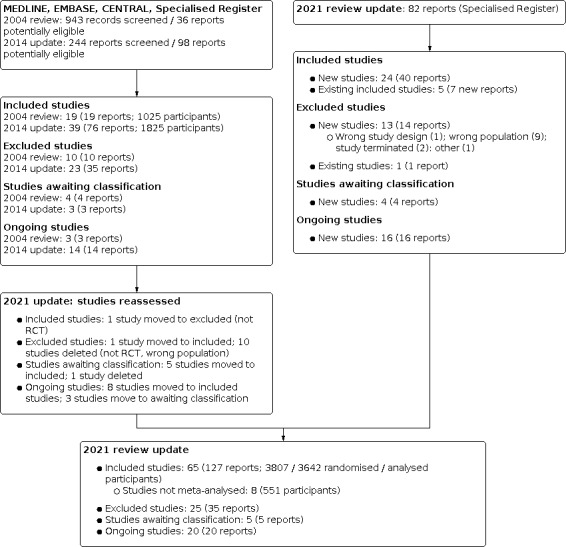

Results of the search

We searched the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Register of Studies 1 April 2021 and identified 82 new reports. After full‐text assessment, 57 new studies were identified; 24 new included studies (40 reports), 13 new studies (14 reports) were excluded, and 16 new ongoing studies were identified. Four new studies are awaiting assessment (recently completed but no data available). We also identified eight new reports of existing included and excluded studies.

In this update, we also reassessed the existing studies.

Included studies: 1 study moved to excluded (not RCT)

Excluded studies: 1 study moved to included; 10 studies deleted (not RCT, wrong population)

Studies awaiting classification: 5 studies moved to included; 1 study deleted

Ongoing studies: 8 studies moved to included studies; 3 studies move to awaiting classification.

A total of 65 studies (127 reports, 3807 randomised participants; Figure 1) were included, 25 excluded, 5 are awaiting assessment, and there are 20 ongoing studies.

1.

2021 review update: study selection flow diagram.

Included studies

A total of 65 studies (3807 randomised participants) investigating immunosuppressive therapy in adults with primary membranous nephropathy and nephrotic syndrome were included in this updated review (Figure 1). The median sample size was 57 (range 9 to 190) patients. The median follow‐up time was 26 months (range 6 months to 12 years). Unpublished data were provided by the authors of two studies (Braun 1995; CYCLOMEN 1994). Eight studies (Appel 2002; Austin 1996a; Dyadyk 2001a; Hladunewich 2014; Sahay 2002; Stegeman 1994; Sun 2014; Zhang 2015d) could not be included in the meta‐analyses as we were unable to extract the necessary data. One study was prematurely terminated due to a low accrual rate (Stegeman 1994).

Four studies only investigated patients with deteriorating kidney function (Cattran 1995; CYCLOMEN 1994; Falk 1992; Reichert 1994). Some studies did not report whether or not they included patients with deteriorating kidney function.

Five studies involved patients who were resistant to corticosteroids monotherapy (Koshikawa 1993; Saito 2014; Shibasaki 2004) or corticosteroids plus alkylating agents (Cattran 2001; Naumovic 2011). Eleven studies included patients who had previously received immunosuppressive treatment before inclusion in the study or who had previously received immunosuppressive treatments if a defined wash‐out period of not receiving any immunosuppressive treatment was completed (Cattran 1989; Chan 2007; Chen 2010a; Donadio 1974; Jha 2007; Liu 2009b; Murphy 1992; Praga 2007; Reichert 1994; Shibasaki 2004; Tiller 1981).

Studies were arranged into the following comparison groups.

Corticosteroids versus placebo/no treatment

Immunosuppressive treatments ± steroids versus placebo/no treatment/non‐immunosuppressive treatments

Immunosuppressive treatments ± steroids versus steroids monotherapy

CPA + leflunomide + steroid versus CPA + steroid

Oral alkylating agents ± steroids versus placebo/no treatment/supportive treatment/steroids

CPA + steroids versus chlorambucil + steroids

Early (immediate) CPA + steroids versus late (when SCr increased > 25%) CPA + steroids

CPA + leflunomide + steroids versus leflunomide + steroids

MMF + CNI versus CNI

CNI ± steroids versus placebo/no treatment/supportive treatment/steroids

CNI ± steroids versus alkylating agents ± steroids

Short‐course tacrolimus + steroids short‐course versus long‐course tacrolimus + steroids

Cyclosporine + steroids versus steroids alone

Cyclosporine + steroids (3.0 mg/kg, once/day) versus cyclosporine + steroids (1.5 mg/kg, twice/day)

Cyclosporine + steroids versus tacrolimus + steroids

Cyclosporin versus AZA

AZA ± steroids versus no treatment

MMF versus no treatment/supportive therapy

MMF ± steroids versus alkylating agents ± steroids

MMF ± steroids versus CNI ± steroids

ACTH versus no treatment

ACTH versus alkylating agents + steroids

Mizoribine ± steroids versus placebo/no treatment/corticosteroids

Mizoribine: 150 mg (once/day) versus 50 mg (3 times/day)

Rituximab + supportive therapy versus supportive therapy alone

Rituximab versus cyclosporine

Traditional Chinese medicine versus immunosuppressive therapy (Shenqi particles; Tripterygium wilfordii)

The following comparisons were planned however no data were available.

Two non‐steroid immunosuppressive agents versus one non‐steroid immunosuppressive agent

CPA + leflunomide + steroid versus CPA + steroids

ACTH 40 IU versus ACTH 80 IU

Studies awaiting classification

Five studies are awaiting assessment (NCT00302523; NCT00518219; NCT01093157; NCT01386554; NCT01845688) and will be assessed in a future update when the methods and results become available.

Ongoing studies

We identified 20 ongoing studies which will be assessed in a future update (Chen 2020; ChiCTR‐INR‐15007440; ChiCTR‐INR‐17011400; ChiCTR‐INR‐17012070; ChiCTR‐INR‐17012212; ChiCTR‐IPR‐16008344; ChiCTR‐IPR‐16008527; ChiCTR‐IPR‐17011386; ChiCTR‐IPR‐17011702; ChiCTR‐TRC‐11001144; CTRI/2017/05/008648; EudraCT2007‐005410‐39; HIGHNESS 2011; ISRCTN17977921; ISRCTN70791258; MMF‐STOP‐IMN 2017; NCT02173106; RI‐CYCLO 2020; STARMEN 2015; UMIN000001099).

Excluded studies

Twenty‐five studies (35 records) were excluded. Reasons for exclusion were: wrong study design or conduct (Branten 1998; Michail 2004; Sharma 2009; Sun 2008); wrong or mixed population (Ambalavanan 1996; Badri 2013; Black 1970; ChiCTR‐IPR‐14005366; Edefonti 1988; Heimann 1987; Krasnova 1998; Lagrue 1975; Li 2012e; Liu 2016c; Majima 1990; MRCWP 1971; Nand 1997; Plavljanic 1998; Ponticelli 1993a; Sharpstone 1969; Xu 2011; Yang 2016a); study was terminated (EudraCT2011‐000242‐38; NCT01762852); and the status of one study is unknown 10 years after initial registration (ChiCTR‐TRC‐09000539).

Risk of bias in included studies

See Figure 2.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Allocation

Random sequence generation

Twenty‐seven studies (48%) specified appropriate methods for random sequence generation and were considered to be at low risk of bias. Appropriate methods of randomisation were not reported in 39 studies (51%). These studies were thus considered to have an unclear risk of bias. One study (1%) was considered to have a high risk of bias for random sequence generation.

Allocation concealment

Twenty studies (31%) reported appropriate allocation concealment methods and were considered to be at low risk of bias, while the remaining45 studies (69%) did not provide details about allocation concealment and were considered to have an unclear risk of bias.

Blinding

Performance bias

Appropriate procedure relating to the blinding of participants was reported in five studies (8%) and were considered to be at low risk of bias. Five studies (5%) were considered to have an unclear risk of bias, and the remaining 55 studies (84%) did not perform adequate blinding of participants and were considered to be at high risk of bias.

Detection bias

Adequate blinding of personnel and outcome assessors was reported in four studies (6%) and were considered to be at low risk of bias. Fifty‐five studies (85%) were considered to have an unclear risk of bias, and the remaining six studies (9%) did not perform adequate blinding of personnel and outcome assessors and were considered to be at high risk of bias.

Incomplete outcome data

Forty‐four studies (68%) were considered to be at low risk of bias; 11 studies (17%) were considered to have an unclear risk of bias, and 10 studies (15%) were considered to be at high risk of bias.

Selective reporting

Forty‐seven studies (72%) were considered to be at low risk of bias and, three studies (5%) were considered to have an unclear risk of bias. Fifteen studies (23%) were considered to be at high risk of bias.

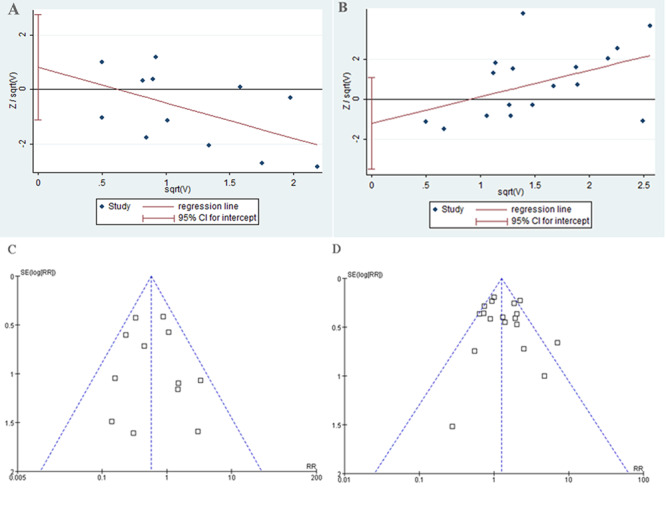

Publication bias

It has been recommended that tests for publication bias should be used only when at least 10 studies are included in the meta‐analysis (Harbord 2009). Given the wide variety of different treatments tested in studies, comparisons did not include more than 10 studies, so that publication bias could not be assessed properly (Figure 3).

3.

Publication bias of comparison: 1 Immunosuppressive treatment versus placebo/no treatment/non‐immunosuppressive treatments, outcome: 1.1 death or risk of ESKD (Harbord test) (A); 1.6 complete or partial remission (Harbord test) (B); 1.1 death or risk of ESKD (funnel plot) (C); and 1.6 complete or partial remission (funnel plots) (D).

Other potential sources of bias

Twenty‐nine studies (45%) were considered to be at low risk of bias; twenty‐five studies (38%) were considered to have an unclear risk of bias. The remaining 11 studies (17%) were assessed as having a high risk of bias using GRADE in this section as there were concerns about potential financial interest or other significant conflicts of interest. Four studies were primarily funded and executed by private companies. These studies were evaluated to be at high risk of bias. Five studies received substantial financial and/or technical support or donated medicines from private companies. These studies were rated as low risk of bias if no employees of private companies were directly involved in the execution of the trial, data analysis and/or publication. Funding from foundations, not‐for‐profit and philanthropic organisations were not considered to increase the risk of bias. The underlying rationale has been detailed in the risk of bias tables in the Characteristics of included studies.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4

Summary of findings 1. Immunosuppressive treatment versus placebo/no treatment/non‐immunosuppressive supportive treatment.

| Immunosuppressive treatment versus placebo/no treatment/non‐immunosuppressive supportive treatment for primary membranous nephropathy in adults with nephrotic syndrome | |||||

| Patient or population: primary membranous nephropathy in adults with nephrotic syndrome Setting: primary care Intervention: immunosuppressive treatment Comparison: control (placebo/no treatment/non‐immunosuppressive supportive treatment) | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Risk with control | Risk with immunosuppressive treatment | ||||

| Death at final follow‐up (range: 9 months to 12 years) |

40 per 1000 | 30 per 1000 (14 to 64) | RR 0.73 (0.34 to 1.59) | 944 (16) | ⊕⊕⊕⊖ Moderate1 |

| End‐stage kidney disease at final follow‐up (range: 9 months to 12 years) |

124 per 1000 | 73 per 1000 (43 to 123) | RR 0.59 (0.35 to 0.99) | 944 (16) | ⊕⊕⊕⊖ Moderate1 |

| Total remission (complete or partial) at final follow‐up (range: 6 months to 12 years) |

337 per 1000 | 485 per 1000 (355 to 663) | RR 1.44 (1.05 to 1.97) | 879 (16) | ⊕⊕⊕⊖ Moderate1 |

| Complete remission at final follow‐up (range: 6 months to 12 years) | 127 per 1000 | 216 per 1000 (133 to 349) | RR 1.70 (1.05 to 2.75) | 879 (16) | ⊕⊕⊕⊖ Moderate1 |

| Recurrence of disease (relapse) at final follow‐up (range: 21 months to 12 years) |

114 per 1000 | 181 per 1000 (102 to 316) |

RR 1.73 (1.05 to 2.86) |

310 (3) | ⊕⊕⊖⊖ Low1,2 |

| 100% increase in serum creatinine at final follow‐up (range: 12 months to 12 years) |

299 per 1000 | 138 per 1000 (78 to 240) |

RR 0.46 (0.26 to 0.80) |

447 (8) | ⊕⊕⊕⊖ Moderate1 |

| Adverse events: temporary/permanent discontinuation or hospitalisation at final follow‐up (range: 6 months to 12 years) |

2 per 1000 | 13 per 1000 (5 to 31) | RR 5.33 (2.19 to 12.98) | 927 (16) | ⊕⊕⊕⊖ Moderate1 |

| Adverse events: infection at 3 years | 54 per 1000 | 159 per 1000 (37 to 682) |

RR 2.95 (0.69 to 12.61) |

106 (1) | ⊕⊖⊖⊖ Very low1,3 |

| Adverse events: malignancy at final follow‐up (range: 17 months to 3 years) |

13 per 1000 | 14 per 1000 (2 to 120) |

RR 1.03 (0.12 to 9.14) |

182 (2) | ⊕⊖⊖⊖ Very Low1,3 |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | |||||

1 Downgraded one level: studies generally unclear or high risk of bias for many domains

2Downgraded one level: serious imprecision ‐ due few events and participants in the included studies

3 Downgraded two levels: very serious imprecision ‐ only one study and very wide confidence intervals indicating appreciable benefit and harm

4Downgraded one level: serious imprecision ‐ very wide confidence intervals indicating appreciable benefit and harm

Summary of findings 2. Oral alkylating agents ± steroids versus placebo/no treatment/steroids.

| Oral alkylating agents ±steroids versus placebo/no treatment/steroids for primary membranous nephropathy in adults with nephrotic syndrome | |||||

|

Patient or population: primary membranous nephropathy in adults with nephrotic syndrome

Setting: primary care Intervention: oral alkylating agents ± steroids Comparison: control (placebo/no treatment/steroids) | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Risk with control | Risk with alkylating agents ± steroids | ||||

| Death at final follow‐up (range: 9 months to 12 years |

37 per 1000 | 28 per 1000 (9 to 84) | RR 0.76 (0.25 to 2.30) | 440 (7) | ⊕⊕⊖⊖ Low1,2 |

| End‐stage kidney disease at final follow‐up (range: 9 months to 12 years) |

146 per 1000 | 61 per 1000 (35 to 108) | RR 0.42 (0.24 to 0.74) | 537 (9) | ⊕⊕⊕⊖ Moderate1 |

| Total remission (complete or partial) at final follow‐up (range: 6 months to 12 years) |

411 per 1000 | 604 per 1000 (459 to 803) | RR 1.37 (1.04 to 1.82) | 468 (9) | ⊕⊕⊕⊖ Moderate1 |

| Complete remission at final follow‐up (range: 9 months to 12 years) |

171 per 1000 | 362 per 1000 (227 to 577) | RR 2.12 (1.33 to 3.38) | 432 (8) | ⊕⊕⊕⊖ Moderate1 |

| Recurrence of disease (relapse) at final follow‐up (range: 21 months to 12 years) |

190 per 1000 | 152 per 1000 (76 to 307) |

RR 0.80 (0.40 to 1.61) |

161 (3) | ⊕⊖⊖⊖ Very low1,3 |

| 100% increase in serum creatinine at final follow‐up (range: 12 months to 12 years) |

329 per 1000 | 194 per 1000 (99 to 382) |

RR 0.59 (0.30 to 1.16) |

332 (7) | ⊕⊕⊕⊖ Moderate1 |

| Adverse events ‐ temporary/permanent discontinuation or hospitalisation at final follow‐up (range: 9 months to 12 years) |

5 per 1000 | 33 per 1000 (11 to 101) | RR 1.44 (0.96 to 2.15 |

184 (3) | ⊕⊕⊖⊖ Low1,4 |

| Adverse events ‐ infection at 3 years | 54 per 1000 | 91 per 1000 (16 to 511) |

RR 1.68 (0.30 to 9.45) |

70 (1) | ⊕⊖⊖⊖ 1,3 Very low |

| Adverse events ‐ malignancy at final follow‐up (range: 3 to 4 years) |

12 per 1000 | 19 per 1000 (2 to 146) |

RR 1.63 (0.21 to 12.37) |

199 (2) | ⊕⊖⊖⊖ Very low1,3 |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | |||||

1 Study limitations: studies generally unclear or high risk of bias for many domains

2 Imprecision: estimate of effect includes negligible difference and considerable benefit and harm

3Downgraded two levels: very serious imprecision ‐ only one study and very wide confidence intervals indicating appreciable benefit and harm

4 Serious imprecision (few participants and few events)

Summary of findings 3. Calcineurin inhibitors ± steroids versus placebo/no treatment/supportive treatment/steroids.

| Calcineurin inhibitors ± steroids versus to placebo/no treatment/supportive treatment/steroids for primary membranous nephropathy in adults with nephrotic syndrome | |||||

|

Patient or population: primary membranous nephropathy in adults with nephrotic syndrome

Setting: primary care Intervention: calcineurin inhibitors ± steroids Comparison: control (placebo/no treatment/supportive treatment/steroids) | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Risk with control | Risk with CNI | ||||

| Death at final follow‐up (range: 9 to 60 months) |

15 per 1000 | 25 per 1000 (7 to 92) | RR 1.69 (0.46 to 6.14) | 296 (7) | ⊕⊖⊖⊖ Verylow1,2,3 |

| End‐stage kidney disease at final follow‐up (range: 9 to 60 months) |

82 per 1000 | 97 per 1000 (44 to 263) | RR 1.18 (0.54 to 2.60) | 296 (7) | ⊕⊖⊖⊖ Verylow1,3,4 |

| Total remission at final follow‐up (range: 9 to 60 months) |

416 per 1000 | 503 per 1000 (258 to 989) | RR 1.21 (0.62 to 2.38) | 206 (5) | ⊕⊕⊖⊖ Low1,5 |

| Complete remission at final follow‐up (range: 9 to 60 months) |

146 per 1000 | 156 per 1000 (74 to 327) | RR 1.07 (0.51 to 2.24) | 206 (5) | ⊕⊕⊖⊖ Low1,5 |

| Recurrence of disease (relapse) at final follow‐up (range: 18 to 60 months) |

259 per 1000 | 404 per 1000 (205 to 801) |

RR 1.56 (0.79 to 3.09) |

92 (2) | ⊕⊖⊖⊖ VeryLow1,4 |

| 100% increase in SCr at final follow‐up (range: 18 to 60 months) |

178 per 1000 | 149 per 1000 (66 to 331) |

RR 0.84 (0.37 to 1.86) |

117 (2) | ⊕⊖⊖⊖ VeryLow1,4 |

| Adverse events ‐ temporary or permanent discontinuation/hospitalisation at final follow‐up (range: 9 to 60 months) |

0/63 | 2/98** | RR 5.45 (0.29 to 101.55) |

156 (5) | ⊕⊖⊖⊖ VeryLow1,4 |

| Adverse events ‐ infection at 36 months | 54 per 1000 | 222 per 1000 (51 to 976) |

RR 4.11 (0.94 to 18.06) |

73 (1) | ⊕⊖⊖⊖ VeryLow1,4 |

| Adverse events ‐ malignancy at 36 months | 0/38 | 2/69** | RR 2.79 (0.14 to 56.57) |

107 (1) | ⊕⊖⊖⊖ VeryLow1,2 |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). ** Event rate derived from the raw data. A 'per thousand' rate is non‐informative in view of the scarcity of evidence and zero events in the control group CI: Confidence interval; CNI: calcineurin inhibitors; RR: Risk ratio | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | |||||

1 Study limitations: studies generally unclear or high risk of bias for many domains

2 Very serious imprecision (2 grades): few events, and estimate of effect includes negligible difference and considerable benefit and harm

3 Serious Indirectness: insufficient follow‐up for the outcome to occur ≤ 10 years

4 Very serious imprecision: few events and estimate of effect includes negligible difference and considerable benefit and harm

5 Serious imprecision: estimate of effect includes negligible difference and considerable benefit and harm

6 Serious imprecision: only one study

Summary of findings 4. Calcineurin inhibitors ± steroids versus alkylating agents ± steroids.

| Calcineurin inhibitors ± steroids versus alkylating agents ± steroids for primary membranous nephropathy in adults with nephrotic syndrome | |||||

|

Patient or population: primary membranous nephropathy in adults with nephrotic syndrome

Setting: primary care Intervention: calcineurin inhibitors ± steroids Comparison: alkylating agents ± steroids | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Risk with alkylating agents ± steroids | Risk with CNI ± steroids | ||||

| Death at final follow‐up (range: 9 to 60 months) |

38 per 1000 | 34 per 1000 (13 to 89) | RR 0.90 (0.35 to 2.34) | 394 (7) | ⊕⊖⊖⊖ Verylow 1,2,3 |

| End‐stage kidney disease at final follow‐up (range: 9 to 60 months) |

15 per 1000 | 36 per 1000 (10 to 134) | RR 2.40 (0.64 to 9.01) | 293 (5) | ⊕⊖⊖⊖ Very low 1,2,3 |

| Total remission at final follow‐up (range: 9 to 60 months) |

784 per 1000 | 791 per 1000 (697 to 901) | RR 1.01 (0.89 to 1.15) | 529 (10) | ⊕⊕⊕⊖ Moderate 1 |

| Complete remission at final follow‐up (range: 9 to 60 months) |

429 per 1000 | 493 per 1000 (360 to 669) | RR 1.15 (0.84 to 1.56) | 533 (10) | ⊕⊕⊖⊖ Low 4,5 |

| Recurrence of disease (relapse) at final follow‐up (range: 9 to 18 months) |

61 per 1000 | 130 per 1000 (43 to 390) |

RR 2.13 (0.71 to 6.37) |

295 (6) | ⊕⊕⊖⊖ Low 1,2 |

| 100% increase in SCr at final follow‐up (range: 9 to 60 months) |

136 per 1000 | 95 per 1000 (41 to 226) |

RR 0.70 (0.30 to 1.67) |

132 (2) | ⊕⊖⊖⊖ Verylow 1,2,3 |

| Adverse events ‐ temporary or permanent discontinuation/hospitalisation at final follow‐up (range: 9 to 12 months) |

42 per 1000 | 60 per 1000 (13 to 278) |

RR 1.43 (0.31 to 6.67) | 151 (3) | ⊕⊖⊖⊖ VeryLow 1,6 |

| Adverse events ‐ infection (range: 9 to 30 months) |

223 per 1000 | 191 per 1000 (96 to 381) |

RR 0.86 (0.43 to 1.71) |

552 (9) | ⊕⊕⊖⊖ Low 1,2 |

| Adverse events ‐ malignancy (range 30 to 36 months |

33 per 1000 | 6 per 1000 (0 to 121) |

RR 0.18 (0.01 to 3.69) |

127 (2) | ⊕⊖⊖⊖ VeryLow1,6 |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; CNI: calcineurin inhibitors; RR: Risk ratio | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | |||||

1 Study limitations (studies generally at unclear or high risk of bias for many domains)

2 Serious imprecision: estimate of effect includes negligible difference and considerable benefit and harm

3 Serious indirectness: Follow‐up less than 10 years

4 Serious study limitations: Unclear randomisation sequence generation and allocation concealment

5 Serious inconsistency: point estimates vary widely, and the magnitude of statistical heterogeneity was high, with I2 =53%

6 Very serious imprecision (2 grades): few events, and estimate of effect includes negligible difference and considerable benefit and harm

See Summary of findings tables for the main comparisons:

Table 1: Immunosuppressive treatments versus placebo/no treatment/non‐immunosuppressive treatments

Table 2: Oral alkylating agent with or without steroids versus placebo/no treatment/steroids

Table 3: CNI versus placebo/no treatment/supportive therapy/steroids

Table 4: CNI with or without steroids versus alkylating agents with or without steroids.

1) Corticosteroids versus placebo or no treatment

Four studies (Cameron 1990; Cattran 1989; Coggins 1979; Donadio 1974) investigated monotherapy with corticosteroids versus placebo or no treatment.

Compared to placebo or no treatment, corticosteroids may make little or no difference to death (Analysis 1.1 (3 studies. 33 participants): RR 0.59, 95% CI 0.11 to 3.23, I² = 32%), ESKD (Analysis 1.2 (3 studies 333 participants): RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.35 to 1.98; I² = 17%), total (complete or partial) remission (Analysis 1.3 (3 studies, 295 participants): RR 1.15, 95% CI 0.58 to 2.27; I² = 69%), complete remission (Analysis 1.4 (2 studies, 192 participants): RR 0.64, 95% CI 0.29 to 1.42; I² = 0%), or partial remission (Analysis 1.5 (2 studies, 192 participants): RR 1.34, 95% CI 0.34 to 5.21; I² = 75%)

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Corticosteroids versus placebo/no treatment, Outcome 1: Death

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Corticosteroids versus placebo/no treatment, Outcome 2: ESKD (dialysis/transplantation)

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Corticosteroids versus placebo/no treatment, Outcome 3: Complete or partial remission

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Corticosteroids versus placebo/no treatment, Outcome 4: Complete remission

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Corticosteroids versus placebo/no treatment, Outcome 5: Partial remission

Compared to placebo or no treatment, corticosteroids may make little or no difference to the number with doubling of SCr (Analysis 1.6.1 (3 studies, 120 participants): RR 0.41, 95% CI 0.11 to 1.53; I² = 19%) or adverse events (Analysis 1.7 (2 studies, 175 participants): RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.11 to 9.82; I² = 0%).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Corticosteroids versus placebo/no treatment, Outcome 6: Increase in serum creatinine

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Corticosteroids versus placebo/no treatment, Outcome 7: Adverse events

It is unclear whether corticosteroids compared to placebo or no treatment improve kidney function (Analysis 1.8; Analysis 1.9; Analysis 1.10). The number relapsing after complete or partial remission was not reported.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Corticosteroids versus placebo/no treatment, Outcome 8: Final serum creatinine

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Corticosteroids versus placebo/no treatment, Outcome 9: Final CrCl

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Corticosteroids versus placebo/no treatment, Outcome 10: Final proteinuria

2) Immunosuppressive treatment versus placebo, no treatment or non‐immunosuppressive treatment

Eighteen studies investigated immunosuppressive treatment versus placebo/no treatment/non‐immunosuppressive treatments (Arnadottir 2006; Badri 2013; Braun 1995; Cattran 1989; Coggins 1979; CYCLOMEN 1994; Donadio 1974; Dussol 2008; GEMRITUX 2017; Imbasciati 1980; Jha 2007; Koshikawa 1993; Kosmadakis 2010; Murphy 1992; Praga 2007; Sharma 2009; Shibasaki 2004; Silverberg 1976).

Compared to placebo/no treatment/non‐immunosuppressive treatment, immunosuppressive treatment probably makes little or no difference to death (Analysis 2.1 (16 studies, 944 participants): RR 0.73, 95% CI 0.34 to 1.59; I² = 0%; moderate certainty evidence) but may reduce the overall risk of ESKD by 40% (Analysis 2.2 (16 studies, 944 participants): RR 0.59, 95% CI 0.35 to 0.99; I² = 22%; moderate certainty evidence) at final follow‐up (9 months to 12 years), and in studies with follow‐up of ≥ 10 years immunosuppressive treatment probably decreases ESKD by 71% (Analysis 2.2.2 (2 studies, 185 participants): RR 0.29, 95% CI 0.13 to 0.63; I² = 0%).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Immunosuppressive treatment ± steroids versus placebo/no treatment/non‐immunosuppressive supportive treatment, Outcome 1: Death

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Immunosuppressive treatment ± steroids versus placebo/no treatment/non‐immunosuppressive supportive treatment, Outcome 2: ESKD (dialysis/transplantation)

Compared to placebo/no treatment/non‐immunosuppressive treatment, immunosuppressive treatment probably increases the number who achieve total remission (Analysis 2.3 (16 studies, 879 participants): RR 1.44, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.97; I² = 73%; moderate certainty evidence) and complete remission (Analysis 2.4 (16 studies, 879 participants): RR 1.70, 95% CI 1.05 to 2.75; I² = 43%; moderate certainty evidence), and may increase the number achieving partial remission (Analysis 2.5 (16 studies, 879 participants): RR 1.36, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.98; I² = 60%). The number relapsing after complete or partial remission may increase with immunosuppressive treatment (Analysis 2.6 (3 studies, 148 participants): RR 1.73, 95% CI 1.05 to 2.86; I² = 0%; low certainty evidence).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Immunosuppressive treatment ± steroids versus placebo/no treatment/non‐immunosuppressive supportive treatment, Outcome 3: Complete or partial remission

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Immunosuppressive treatment ± steroids versus placebo/no treatment/non‐immunosuppressive supportive treatment, Outcome 4: Complete remission

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Immunosuppressive treatment ± steroids versus placebo/no treatment/non‐immunosuppressive supportive treatment, Outcome 5: Partial remission

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Immunosuppressive treatment ± steroids versus placebo/no treatment/non‐immunosuppressive supportive treatment, Outcome 6: Relapse after complete or partial remission

Immunosuppressive treatment probably decreases the number with doubling of SCr (Analysis 2.7 (9 studies, 447 participants): RR 0.46, 95% CI 0.26 to 0.80; I² = 21%; moderate certainty of the evidence), but may increase the number experiencing temporary or permanent discontinuation/hospitalisation due to adverse events (Analysis 2.9 (18 studies, 927 participants): RR 5.33, 95% CI 2.19 to 12.98; I² = 0%; low certainty evidence). Immunosuppressive treatment has uncertain effects on infection and malignancy.

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Immunosuppressive treatment ± steroids versus placebo/no treatment/non‐immunosuppressive supportive treatment, Outcome 7: 100% increase in serum creatinine

2.9. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Immunosuppressive treatment ± steroids versus placebo/no treatment/non‐immunosuppressive supportive treatment, Outcome 9: Temporary or permanent discontinuation/hospitalisation due to adverse events

Immunosuppressive treatment may improve GFR (Analysis 2.14), proteinuria (Analysis 2.15), but not SCr (Analysis 2.13).

2.14. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Immunosuppressive treatment ± steroids versus placebo/no treatment/non‐immunosuppressive supportive treatment, Outcome 14: Final GFR [mL/min/1.73 m²]

2.15. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Immunosuppressive treatment ± steroids versus placebo/no treatment/non‐immunosuppressive supportive treatment, Outcome 15: Final proteinuria

2.13. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Immunosuppressive treatment ± steroids versus placebo/no treatment/non‐immunosuppressive supportive treatment, Outcome 13: Final serum creatinine

3) Immunosuppressive treatments with or without steroids versus steroids alone

Five studies (Ahmed 1994; Falk 1992; Hasegawa 2017; Pahari 1993; Ponticelli 1992) compared immunosuppressive treatment with steroids alone.

Immunosuppressive treatment may make little or no difference to death (Analysis 3.1) or ESKD (Analysis 3.2), but may increase the number achieving total remission (Analysis 3.3 (5 studies, 241 participants): (RR 1.47, 95% CI 1.19 to 1.82; I² = 0%) and complete remission (Analysis 3.4 (4 studies, 205 participants): RR 1.89, 95% CI 1.34 to 2.65; I² = 0%). There were no differences between studies that had a follow‐up of less than 2 years and studies with 2 years or more of follow‐up.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Immunosuppressive treatment ± steroids versus steroids, Outcome 1: Death

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Immunosuppressive treatment ± steroids versus steroids, Outcome 2: ESKD (dialysis/transplantation)

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Immunosuppressive treatment ± steroids versus steroids, Outcome 3: Complete or partial remission

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Immunosuppressive treatment ± steroids versus steroids, Outcome 4: Complete remission

Immunosuppressive treatment had uncertain effects on doubling of SCr (Analysis 3.7 (3 studies, 97 participants): RR 1.19, 95% CI 0.52 to 2.71; I² = 0%), adverse events (Analysis 3.9; Analysis 3.8), and relapse after complete or partial remission (Analysis 3.6).

3.7. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Immunosuppressive treatment ± steroids versus steroids, Outcome 7: Increase in serum creatinine

3.9. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Immunosuppressive treatment ± steroids versus steroids, Outcome 9: Adverse events

3.8. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Immunosuppressive treatment ± steroids versus steroids, Outcome 8: Temporary or permanent discontinuation/hospitalisation due to adverse events

3.6. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Immunosuppressive treatment ± steroids versus steroids, Outcome 6: Relapse after complete or partial remission

4) Cyclophosphamide plus leflunomide plus steroids versus cyclophosphamide plus steroids

Liu 2015e reported CPA plus leflunomide plus steroids may increase complete remission compared to leflunomide plus steroids (Analysis 4.1 (1 study. 48 participants): RR 1.50, 95% CI 1.04 to 2.17). No other outcomes were reported.

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4: Cyclophosphamide + leflunomide + steroid versus cyclophosphamide + steroid, Outcome 1: Complete remission

5) Oral alkylating agents with or without steroids versus placebo/no treatment/supportive treatment/steroids

Nine studies (Ahmed 1994; Braun 1995; Donadio 1974; Hasegawa 2017; Imbasciati 1980; Jha 2007; Kosmadakis 2010; Pahari 1993) investigated oral alkylating agents with or without steroids versus placebo/no treatment/supportive treatments/steroids only.

Oral alkylating agents may have little or no effects on death (Analysis 5.1 (7 studies, 440 participants): RR 0.76, 95% CI 0.25 to 2.30; I² = 0%; low certainty evidence) compared with no treatment/placebo/steroids alone but probably decreases ESKD at final follow‐up (Analysis 5.2 (9 studies, 537 participants): RR 0.42, 95% CI 0.24 to 0.74; I² = 0%; moderate certainty evidence). In moderate certainty evidence, total and complete remission may increase using oral alkylating agents with or without steroids (Analysis 5.3 (9 studies, 468 participants): RR 1.37, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.82; I² = 70%; Analysis 5.4 (8 studies, 432 participants): RR 2.12, 95% CI 1.33 to 3.38; I² = 37%), but uncertain effects on partial remission (Analysis 5.5 (8 studies, 432 participants): RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.57 to 1.55; I² = 57%) and the number relapsing after complete or partial remission (Analysis 5.7). There was no evidence of difference for studies with < 10 years follow‐up and the study with ≥ 10 years follow‐up.

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5: Oral alkylating agents ± steroids versus placebo/no treatment/steroids, Outcome 1: Death

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5: Oral alkylating agents ± steroids versus placebo/no treatment/steroids, Outcome 2: ESKD (dialysis/transplantation)

5.3. Analysis.

Comparison 5: Oral alkylating agents ± steroids versus placebo/no treatment/steroids, Outcome 3: Complete or partial remission

5.4. Analysis.

Comparison 5: Oral alkylating agents ± steroids versus placebo/no treatment/steroids, Outcome 4: Complete remission

5.5. Analysis.

Comparison 5: Oral alkylating agents ± steroids versus placebo/no treatment/steroids, Outcome 5: Partial remission

5.7. Analysis.

Comparison 5: Oral alkylating agents ± steroids versus placebo/no treatment/steroids, Outcome 7: Relapse after complete or partial remission

It is uncertain whether oral alkylating agents decrease the doubling of SCr (Analysis 5.6.1 (7 studies, 332 participants): RR 0.59, 95% CI 0.30 to 1.16; I² = 42%; low certainty evidence). Oral alkylating agents compared with placebo/no treatment/steroids may increase temporary or permanent discontinuation or hospitalisation due to adverse events (Analysis 5.8 (8 studies 439 participants): RR 6.82, 95% CI 2.24 to 20.71; I² = 0%; low certainty evidence). Oral alkylating agents with or without steroids had uncertain effects on infection (Analysis 5.9.2), malignancy (Analysis 5.9.3) and final GFR (Analysis 5.10).

5.6. Analysis.

Comparison 5: Oral alkylating agents ± steroids versus placebo/no treatment/steroids, Outcome 6: Increase in serum creatinine

5.8. Analysis.

Comparison 5: Oral alkylating agents ± steroids versus placebo/no treatment/steroids, Outcome 8: Temporary or permanent discontinuation/hospitalisation due to adverse events

5.9. Analysis.

Comparison 5: Oral alkylating agents ± steroids versus placebo/no treatment/steroids, Outcome 9: Adverse events

5.10. Analysis.

Comparison 5: Oral alkylating agents ± steroids versus placebo/no treatment/steroids, Outcome 10: Final GFR [mL/min/1.73 m²]

6) Cyclophosphamide plus steroids versus chlorambucil plus steroids

Two studies (Ponticelli 1998; Reichert 1994) investigated CPA plus steroids versus chlorambucil plus steroids.

There was only one death reported in the CPA group in Reichert 1994. We are uncertain whether CPA plus steroids increases the risk of ESKD (Analysis 6.2 (2 studies, 115 participants): RR 3.01, 95% CI 0.61 to 14.81; I² = 0%).

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6: Cyclophosphamide + steroids versus chlorambucil + steroids, Outcome 2: ESKD (dialysis/transplantation)

CPA plus steroids compared with chlorambucil plus steroids may increase total remission (Analysis 6.3 (2 studies, 115 participants): RR 1.23, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.50; I² = 0%; low certainty evidence), however, it had uncertain effects on complete (Analysis 6.4) and partial remission (Analysis 6.5) (low certainty evidence). Relapse after complete or partial remission was not reported.

6.3. Analysis.

Comparison 6: Cyclophosphamide + steroids versus chlorambucil + steroids, Outcome 3: Complete or partial remission

6.4. Analysis.

Comparison 6: Cyclophosphamide + steroids versus chlorambucil + steroids, Outcome 4: Complete remission

6.5. Analysis.

Comparison 6: Cyclophosphamide + steroids versus chlorambucil + steroids, Outcome 5: Partial remission

It is uncertain whether CPA plus steroids decreases the number with doubling of SCr (Analysis 6.6), decreases temporary or permanent discontinuation or hospitalisation due to adverse events (Analysis 6.7), improves kidney function (Analysis 6.8), or decreases proteinuria (Analysis 6.9).

6.6. Analysis.

Comparison 6: Cyclophosphamide + steroids versus chlorambucil + steroids, Outcome 6: Increase in serum creatinine

6.7. Analysis.

Comparison 6: Cyclophosphamide + steroids versus chlorambucil + steroids, Outcome 7: Temporary or permanent discontinuation/hospitalisation due to adverse events

6.8. Analysis.

Comparison 6: Cyclophosphamide + steroids versus chlorambucil + steroids, Outcome 8: Final serum creatinine

6.9. Analysis.

Comparison 6: Cyclophosphamide + steroids versus chlorambucil + steroids, Outcome 9: Final proteinuria

7) Early (immediate) cyclophosphamide versus late (serum creatinine increase > 25%) cyclophosphamide plus steroids

Hofstra 2010 investigated early (immediate) initiation of therapy with CPA versus late (SCr increase by > 25%) initiation of therapy with CPA and steroids. Participants were followed up for a mean period of 72 ± 22 months.

Hofstra 2010 reported one death in the initiation group (Analysis 7.1), and one patient reached ESKD in the early initiation group (Analysis 7.2).

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7: Early (immediate) cyclophosphamide + steroids versus late (when SCr increase > 25%) cyclophosphamide + steroids, Outcome 1: Death

7.2. Analysis.

Comparison 7: Early (immediate) cyclophosphamide + steroids versus late (when SCr increase > 25%) cyclophosphamide + steroids, Outcome 2: ESKD (dialysis/transplantation)

We are uncertain whether early initiation of CPA improved total (Analysis 7.3), complete (Analysis 7.4) or partial remission (Analysis 7.5) due to very low certainty evidence. We are also uncertain whether early initiation of CPA improves temporary or permanent discontinuation or hospitalisation due to adverse events (Analysis 7.6), SCr (Analysis 7.7), eGFR (Analysis 7.8), or proteinuria (Analysis 7.9), because the certainty of the evidence is very low.

7.3. Analysis.

Comparison 7: Early (immediate) cyclophosphamide + steroids versus late (when SCr increase > 25%) cyclophosphamide + steroids, Outcome 3: Complete or partial remission

7.4. Analysis.

Comparison 7: Early (immediate) cyclophosphamide + steroids versus late (when SCr increase > 25%) cyclophosphamide + steroids, Outcome 4: Complete remission

7.5. Analysis.

Comparison 7: Early (immediate) cyclophosphamide + steroids versus late (when SCr increase > 25%) cyclophosphamide + steroids, Outcome 5: Partial remission

7.6. Analysis.

Comparison 7: Early (immediate) cyclophosphamide + steroids versus late (when SCr increase > 25%) cyclophosphamide + steroids, Outcome 6: Temporary or permanent discontinuation/hospitalisation due to adverse events

7.7. Analysis.

Comparison 7: Early (immediate) cyclophosphamide + steroids versus late (when SCr increase > 25%) cyclophosphamide + steroids, Outcome 7: Final serum creatinine

7.8. Analysis.

Comparison 7: Early (immediate) cyclophosphamide + steroids versus late (when SCr increase > 25%) cyclophosphamide + steroids, Outcome 8: Final GFR [mL/min/1.73 m²]

7.9. Analysis.

Comparison 7: Early (immediate) cyclophosphamide + steroids versus late (when SCr increase > 25%) cyclophosphamide + steroids, Outcome 9: Final proteinuria

Relapse and other adverse events were not reported.

8) Cyclophosphamide plus leflunomide plus steroids versus leflunomide plus steroids

Liu 2015e reported CPA plus leflunomide plus steroids versus leflunomide plus steroids may make little or no difference to complete remission (Analysis 8.1 (1 study, 48 participants): RR 1.40, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.98) or malignancy (Analysis 8.2). No other outcomes were reported.

8.1. Analysis.

Comparison 8: Cyclophosphamide + leflunomide + steroid versus leflunomide + steroid, Outcome 1: Complete remission

8.2. Analysis.

Comparison 8: Cyclophosphamide + leflunomide + steroid versus leflunomide + steroid, Outcome 2: Malignancy

9) Mycophenolate mofetil plus calcineurin inhibitors versus calcineurin inhibitors alone

Jurubita 2012 investigated CSA plus MMF versus CSA alone and Nikolopoulou 2019 investigated TAC plus MMF versus TAC alone.