Abstract

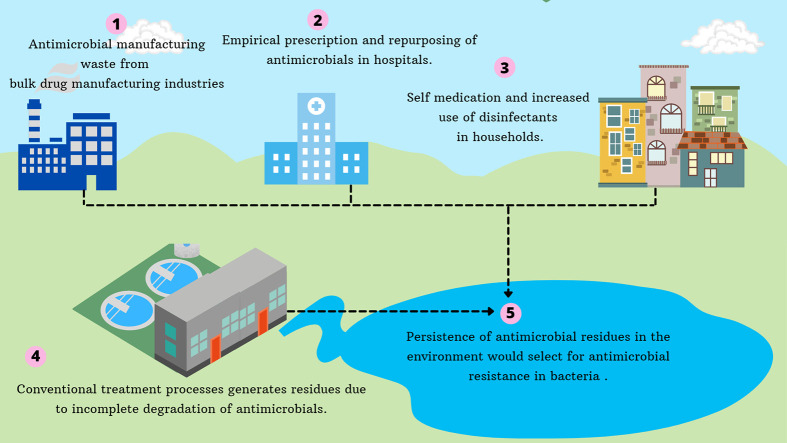

The COVID-19 pandemic has shattered millions of lives globally and continues to be a challenge to public health due to the emergence of variants of concern. Fear of secondary infections following COVID-19 has led to an escalation in antimicrobial use during the pandemic, while some antimicrobials have been repurposed as treatments for SARS-CoV-2, further driving antimicrobial resistance. India is one of the largest producers and consumers of antimicrobials globally, hence the task of curbing antimicrobial resistance is a huge challenge. Practices like empirical antimicrobial prescription and repurposing of drugs in clinical settings, self-medication and excessive use of antimicrobial hygiene products may have negatively impacted the prevalence of antimicrobial resistance in India. However, the expanded production of antimicrobials and disinfectants during the pandemic in response to increased demand may have had an even greater impact on the threat of antimicrobial resistance through major impacts on the environment. The review provides an outline of the impact COVID-19 can have on antimicrobial resistance in clinical settings and the possible outcomes on the environment. This review calls for the upgrading of existing antimicrobial policies and emphasizes the need for research studies to understand the impact of the pandemic on antimicrobial resistance in India.

Keywords: COVID-19, AMR, Empirical consumption, Antimicrobial residues, Antimicrobial manufacturing waste

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) and COVID-19 are the two pandemics the world is currently challenged with and that pose a significant threat to public health in a global scale. Infections resulting from antimicrobial resistant bacteria are expected to claim 10 million lives globally, per year by 2050 (O'Neill, 2014). COVID-19 and AMR are interacting health emergencies which can have mutual impact due to mis-use of existing antimicrobials for the treatment of COVID-19 patients since a specific treatment is absent for the disease (Nieuwlaat et al., 2021). If the current trend of AMR goes unchecked, it would result in the shortage of available therapeutics in future and may even mark an end to the conventional drug discovery pipeline (Kaul et al., 2019). By the year 2050, infections caused by antimicrobial resistant bacteria are projected to cause 2 million deaths in India. Considering India's huge population, the threat of AMR extends to other nations as well. International travel results in the dissemination of antimicrobial resistant bacteria to different nations and continents, extending the threat of AMR in India to a global scale (Frost et al., 2019a). New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase (NDM-1) producing bacteria which are resistant to carbapenems emerged in India and have rapidly disseminated to other nations causing a havoc in health care, worldwide (Nordmann et al., 2011).

India observed a sudden spike of COVID-19 cases from mid-March of 2021 which rose steeply to more than 300,000 COVID-19 cases consecutively for 10 days (Samarasekera, 2021). The crisis worsened with shortages of hospital beds, oxygen supplies, overwhelmed hospitals and exhausted health staff (The Lancet, 2021). Prior to the pandemic, India was already facing major challenges in antimicrobial resistance, with prevalence of highly resistant Gram-negative bacteria orders of magnitude higher than many high-income countries (Gandra et al., 2019; Gandra et al., 2016; Walia et al., 2019). Among the hospitalized COVID-19 patients in India, a predominance of Gram-negative bacteria resistant to higher generation of antimicrobials was observed (Vijay et al., 2021). It is uncertain to what extent COVID-19 will raise AMR and impede the efforts taken to curb its spread, however, there are several determinants of the ongoing pandemic which could possibly fuel the prevailing AMR threat in India.

With attention focused on tackling COVID-19, efforts to curb antimicrobial resistance have largely been put on hold in community and healthcare settings. The current pandemic will amplify the threat of antimicrobial resistance in India: Practices that were already prevalent such as over-the-counter use of antimicrobial drugs and empirical prescription of broad-spectrum antibiotics will have increased with any increase in febrile respiratory illness, while COVID-19 has more specifically led to increased use of antimicrobials through re-purposing and management of secondary infections. While the negative impact of the pandemic on antimicrobial stewardship and excessive consumption has been highlighted around the globe (Rawson et al., 2020, Rawson et al., 2020; Ghosh et al., 2021), India as a world leader in production faces a greater threat: Environmental contamination with antimicrobial waste resulting from a pandemic-altered manufacturing landscape. Excessive use of hygienic products, practice of self-medication, and expanded production of antimicrobials associated with COVID-19, could amplify the concentration of these compounds in the environment. This is further challenged by weak waste management infrastructure and poor sanitation observed in developing communities like India. Antimicrobial residues accumulating in the environment can induce the development of resistance in bacteria to antibiotics.

In this review we provide an overview of the AMR situation in clinical settings in India during the pandemic and explain in detail how the consumption and production of antimicrobials exacerbated by COVID-19 can overwhelm the crisis of AMR in India.

2. AMR in the backdrop of COVID-19: a clinical overview

2.1. Co-infections and secondary infections in healthcare during the COVID-19 pandemic

Viral respiratory infections have been closely linked to increased chances of bacterial co-infections (Rawlinson et al., 2003; Beadling and Slifka, 2004). Although secondary infections caused by bacteria and fungal pathogens were reported frequently in severe cases of COVID-19 (Chen et al., 2020), this finding is not universal (Hughes et al., 2020; Rawson et al., 2020, Rawson et al., 2020; Garcia-Vidal et al., 2021). Preliminary reports from China suggested 50% patients who died of COVID-19 were affected by secondary bacterial infections (Zhou et al., 2020). Concern about bacterial co-infections in COVID-19 will have been augmented by reports of co-infections in MERS-CoV intensive care patients (Memish et al., 2020). It is apparent that co-infection may be more related to hospital-acquired and intensive care-associated secondary infection than COVID-19 alone and may not be the leading cause of death in contrast to co-infection in influenza (Morens et al., 2008).

Several mechanisms could underlie a co-infection risk in COVID-19 patients: During viral infections, viruses can obstruct the configuration required for mucociliary clearance which could enhance the adherence of bacteria to mucins. In addition to this the dense mucus will prevent the entry of immune cells and antimicrobial substances (Wilson et al. 1996). The inflammation stimulated by viral infection activates epithelial cells to alter the expression pattern of surface receptors which can also favor attachment of bacteria (Morris, 2007). SARS-CoV-2 may facilitate colonization of bacterial pathogens to host tissues in a similar manner and result in systemic dissemination of the virus and bacteria (Bengoechea and Bamford, 2020). Health conditions such as severe lymphopenia and respiratory failure observed in COVID-19 patients can also increase the chance of acquiring secondary infections (Ripa et al., 2021).

There are several healthcare practices that have augmented the risk of secondary infection. Mechanical ventilation, consumption of steroidal drugs and other comorbidities can act as a predisposing factor for secondary infections in critically ill COVID-19 patients (Chowdhary et al., 2020). Susceptibility to unusual infections in the intensive care unit has been linked in part to the practice of “proning” patients (placing patients prone, face down, to improve ventilations), leading to greater risk of skin maceration and contact with fomites. Excessive use of personal protective equipment coupled with reduced attention to contact precautions when caring for patients has also been highlighted as a risk for nosocomial infection. Increasing use of steroids in COVID-19 and biological therapies that impair cytokine responses may further augment the risk of fungal and bacterial co-infections. This may underlie the reasons why COVID-19 patients are reportedly vulnerable to opportunistic fungal infections such as pulmonary aspergillosis, mucormycosis, cryptococcosis, and pneumocystis pneumonia which have a high mortality rate (Song et al., 2020; Salehi et al., 2020).

In India, a high rate of secondary infections was observed in hospitalized COVID-19 patients of both intensive care unit (ICU) and non-ICU wards during the first wave of the pandemic (Vijay et al., 2021; Khurana et al., 2021). A study by Vijay et al. (2021) found that 3.6% of COVID-19 patients developed secondary infections following hospitalization and the mortality rate among these patients was estimated to be 56.7%. The B.1.617 variant resulted in a massive surge of COVID-19 cases in India during the second wave (Vaidyanathan, 2021). Unexpectedly, India witnessed an increasing trend of mucormycosis in COVID-19 recovered patients during the second wave of the pandemic (Gade et al., 2021). Mucormycosis, an infection with high mortality even when treated, occurred either during or subsequent SARS-CoV-2 infection. Unmanageable diabetes mellitus and immune suppression linked to intake of steroids in COVID-19 patients are known to escalate the risk of fungal infections (Sen et al., 2021). Among the 101 cases of COVID-19-associated mucormycosis reported globally, 82 cases are from India (Singh et al., 2021a). Cases of fatal mucormycosis have been reported among COVID-19 patients in India where the patient deteriorated even after administration of amphotericin B (Nehara et al., 2021). With a lack of population-based studies, the exact incidence of mucormycosis in India is not yet clear (Prakash and Chakrabarti, 2021).

The evidence base regarding secondary and co-infection in COVID-19 is hampered in two ways. Firstly, there is little contextual epidemiological information that allows COVID-19 to be compared with other, similar respiratory viral infections, except in large intensive care databases. As such, although secondary infections are documented in patients diagnosed with COVID-19, whether these are any more frequently observed than in other patients ventilated for pneumonia is unclear. Apart from highly virulent infections such as from species of Mucorales, it is also difficult to comment whether hospital acquired infections are connected to increased COVID-19 severity and mortality. Secondly, invasive diagnostic methods are not routinely undertaken in COVID-19 patients, in part related to infection control considerations, leading to an increase in empiric prescribing.

2.2. Antimicrobial resistance in healthcare during the COVID-19 pandemic

COVID-19 patients in ICU are subject to antimicrobial therapy more often and the decision to treat is based on laboratory markers of inflammation and severity of the disease (Mustafa et al., 2021). Indeed, COVID-19 patients have been subject to antibiotic therapy even in the absence of underlying secondary infections (Moretto et al., 2021). A meta-analysis carried out in the initial six months of the pandemic observed that three-quarters of COVID-19 patients received antibiotic therapy globally (Langford et al., 2021). A recent review by Chedid et al. (2021) reveals that the mean antibiotic use for COVID-19 management is 74% where only 17. 6% patients are tested positive for secondary infections. This underlines the extent to which un-targeted and empiric use of antimicrobials has increased in the wake of the pandemic.

The intersection between AMR and COVID-19 was highlighted by many researchers at the beginning of pandemic (Bengoechea and Bamford, 2020; Cantón et al., 2020; Murray, 2020). AMR in hospitalized COVID-19 patients has been reported from many countries. A study by Kampmeier et al. (2020) reported vanB clones of Enterococcus faecium in COVID-19 subjects from intensive care wards in Germany. New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase (NDM) producing Enterobacter cloacae were isolated from critically-ill COVID-19 patients in New York City, which resulted in the death of four out of five patients admitted at the medical center (Nori et al., 2020). NDM-beta-lactamase-producing carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales isolated from COVID-19 patients of a teaching hospital from Italy worsened the outcome of patients significantly by prolonging length of stay (Porretta et al., 2020). A higher incidence of invasive antimicrobial resistant fungal infections has also been documented in COVID-19 patients: Posteraro et al. (2020) reported a fatal COVID-19 case in Italy where the patient succumbed to death due to co-infection with resistant bacteria and pan-echinocandin-resistant Candida glabrata. Several studies have also pointed out the failure of antimicrobial therapy in Aspergillus infections (Koehler et al., 2020; Alanio et al., 2020; Rutsaert et al., 2020; Blaize et al., 2020; Arastehfar et al., 2020). Evidence comparing prevalence of AMR in specific bacterial and fungal species during the pandemic and pre-pandemic will no doubt emerge in countries where AMR is subject to routine mandatory surveillance.

A tertiary hospital in India reported an overall antimicrobial resistance to be 84% in COVID-19 patients with secondary infections between April 3 and July 11, 2020 (Khurana et al., 2021). The pathogens isolated from these patients exhibited resistance to: amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, levofloxacin, ciprofloxacin, piperacillin/tazobactam, and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole with an overall resistance of 64% to 69% to third-generation cephalosporins and carbapenems (Khurana et al., 2021). Another study carried out by Vijay et al. (2021) reported nosocomial pathogens exhibiting resistance to cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones and β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations, piperacillin/tazobactam and cefoperazone-sulbactam in COVID-19 patients. A greater occurrence of Candida auris blood stream infection was reported in India in COVID-19 patients; most of the C. auris clinical isolates were found to be resistant to antifungal agents such as amphotericin B and fluconazole (Chowdhary et al., 2020). Candida infections resistant to these fungal agents is a matter of concern for low-resource countries where there is limited accessibility to echinocandins and is likely to eventually result in treatment failure (Chowdhary et al., 2020). Certain isolates of Syncephalastrum monosporum which caused mucormycosis in COVID-19 patients were found to exhibit elevated minimum inhibitory concentrations for itraconazole and posaconazole (Singh et al., 2021b).

The Indian Council of Medical Research have reported a higher prevalence of AMR infections in hospitals in India during the pre-COVID-19 period (ICMR, 2019) and the surge of COVID-19 cases in India will likely exacerbate the overall prevalence of AMR infections in hospitals. Studies that have reported the incidence of AMR stem mainly from the first wave of COVID-19 infections in India, while the impact of second wave of COVID-19 on the incidence of AMR infections is not yet clear. The second wave of COVID-19 in India resulted an overflow of patients in hospitals impacting the ability to implement routine infection control practices, paving the way to nosocomial transmission of both SARS-CoV-2 and multi-drug resistant microorganisms. Scarcity in available data makes it difficult to determine if the prevalence of AMR has escalated in India, potentially compounded by under-reporting of antimicrobial surveillance data from hospitals already overwhelmed by the workload of the second pandemic wave. The few studies that do exist, conducted on secondary infections in COVID-19 patients, suggests that AMR may well have worsened. Incorporating AMR surveillance and stewardship alongside the COVID-19 response will be greatly advantageous (Getahun et al., 2020).

3. Antimicrobials used for COVID-19 management in India

Several different guidelines have operated worldwide since the onset of the pandemic. Combination therapy with azithromycin and hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) has been recommended in COVID-19 patients in some countries despite its risk of prolonging the QT interval (Gautret et al., 2020). In China, empirical use of antibiotics like azithromycin, amoxicillin or fluroquinolones has been recommended in mild cases of COVID-19 while broad-spectrum antibiotics were advocated in severe cases to eliminate all possible bacterial co-pathogens (Jin et al., 2020). Initially in the UK, empirical oral administration of doxycycline was suggested in patients who were at increased risk of COVID-19-associated complications or when it was difficult to determine if the causative agent was bacterial or viral, perhaps because patients were asked to remain at home and not present to healthcare (NICE, 2020). Later, antibiotic treatment was limited to confirmed bacterial co-infections (NICE, 2021). Treatment guidelines for COVID-19 management in African countries recommend antibiotics, with Liberia suggesting use of antibiotics for COVID-19 associated symptoms such as cough, diarrhea and sore throat (Adebisi et al., 2021). A survey on antibiotic use in COVID-19 patients reported piperacillin/tazobactam as the most used antibiotic in general, whereas a preponderance in the use of fluoroquinolones in combination with other antibiotics and carbapenems was observed in Italy (Beović et al., 2020).

India is one of the countries most severely affected by COVID-19 with approximately 31 million cases reported in India as of July 2021 (Arogya setu mobile app). For patients with severe illness, a combination of HCQ and the antibiotic azithromycin was initially recommended by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare in India. The anti-malarial drug HCQ was recommended for asymptomatic healthcare personnel, asymptomatic frontline personnel, and asymptomatic household contacts of the confirmed patients (MoHFW, 2020). Later ivermectin, another antiparasitic drug, was introduced as an alternative for HCQ in COVID-19 management in India (MoHFW, 2021). The standard operating protocol for COVID-19 management is different throughout Indian states. For example, the state health boards of the Indian states Bihar and West Bengal recommend the use of ivermectin and doxycycline in all patients diagnosed with severe COVID-19 (Government of Bihar, 2021; Health and Family welfare department, 2021). In the Indian state of Maharashtra, use of antimicrobials is based on the severity of COVID-19 illness. For those with mild symptoms and other comorbidities the antibiotic cefixime or amoxicillin clavulanate along with HCQ is recommended, whereas in patients with moderate illness and pneumonia, empiric intravenous administration of ceftriaxone for 5–10 days has been recommended. In severe cases with pneumonia, septic shock, or acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), intravenous administration of meropenem is suggested (Government of Maharashtra, 2020). The latest guidelines for treatment by the Maharashtra COVID-19 task force have revised the protocol to recommend piperacillin-tazobactam in cases of pneumonia with respiratory failure (Nagpur Municipal Corporation, 2021). Use of carbapenems and even the so-called “last resort” antibiotic colistin have been reported in COVID-19 patients in India (Gale and Shrivastava, 2020). Most of the antibiotics prescribed in treatment of bacterial infections in COVID-19 patients in India come under the category of ‘Watch’ and ‘Reserve’ in the WHO Aware, Watch and Reserve (AWaRe) classification. The WHO advises against the prescription of antimicrobial agents in mild to moderate cases of COVID-19 cases without clear indication of bacterial infections (WHO, 2020). Ideally, local guidelines set by public health agencies should adhere to WHO guidelines and the choice of antibiotic for treatment should be based on confirmation of bacterial infection and antibiogram profiling rather than empirical prescription.

Although repurposing antimicrobials such as HCQ, azithromycin and doxycycline might appear to be a reasonable approach to COVID-19 management, it is by no means clear that such drugs have any activity against COVID-19 apart from their already known anti-bacterial or anti-malarial activity; their injudicious use can have setbacks. The use of HCQ is a big concern for India as malaria is endemic in the country (WHO, 2018; Principi and Esposito, 2020), and its indiscriminatory use may contribute to resistance in Plasmodium sp. (Sutherland et al., 2007). Typhoid fever is an important health concern for India specifically because of the emergence of azithromycin resistance in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi (Carey et al., 2021). In such a situation, the decision to repurpose azithromycin in India could endanger the treatment of typhoid fever. Irrational use of doxycycline in poultry rearing is already a prevailing issue in developing communities (Waghamare et al., 2020; Ali et al., 2020) and introduction of the antibiotic as a treatment regimen for COVID-19 may exacerbate the risk of doxycycline resistance. Ivermectin resistance has also been documented in several studies (Dent et al., 2000; Osei-Atweneboana et al., 2011) highlighting the need for surveillance of these antimicrobial drugs in developing countries before its implementation as an anti-SARS-CoV-2 drug.

4. The AMR burden of antimicrobial production and consumption: a pandemic point of view

The consumption of antimicrobials by humans and animals and their subsequent excretion is considered a major source of antimicrobial residues in the environment. Even though the concentration of antimicrobials is in low ranges of μg/kg to mg/kg (soil) and ng/L to μg/L (water), their presence in such levels has been found to promote antimicrobial resistance (Gilbertson et al., 1990; Boxall et al., 2003; Göbel et al., 2004; Roberts and Thomas, 2006; Watkinson et al., 2009). In addition to consumption of antimicrobials, the pharmaceutical industry acts as another important source for antimicrobial residues in the environment. The pharmaceutical industry comprises of active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) units that manufacture the raw materials of antimicrobials and units that formulate antimicrobials to finished pharmaceutical product (FPP) (Nahar, 2020). Residues emerging from these sources lays grounds for the development of AMR in bacteria.

While the Republic of China is the chief global hub for API production, the Indian pharmaceutical industry is oriented towards the formulation of FPP (Arnum, 2013; Gandra et al., 2017). The environment surrounding API manufacturing units has been identified as an important source of AMR bacteria, especially in India (Larsson et al., 2007; Rutgersson et al., 2014; Bengtsson-Palme et al., 2014). Despite an order by the Supreme Court of India to treat wastewater and reuse it, pharmaceutical industries have breached these regulations (The Hans India, 2015; Changing Markets, 2021). Technologies to ensure zero liquid discharge are expensive, and pharmaceutical industries may elect to dispose residues and waste directly into surrounding environments surreptitiously (The Hans India, 2015; Changing Markets, 2021). A lack of effective waste management in the API manufacturing and formulating industries leads to dispersal of manufacturing wastes to water bodies and further leads to the development of AMR. Aquatic environments surrounded by bulk drug manufacturing companies in India was found to exhibit 1000 times higher concentration of antimicrobials than what is generally found in rivers of high-income countries (Gothwal and Shashidhar, 2017).

The pandemic has also resulted in more pharmaceutical companies commencing production of azithromycin and HCQ in India (The Times of India, 2020; The Economic Times, 2020). It can therefore be expected that the overall production of antimicrobials, especially those that have been recommended for treating COVID-19 is likely to have escalated. Increased production of antimicrobials coupled with poor waste management strategies is predicted to intensify the prevalence of AMR in environmental settings. Environment (Protection) Amendment Rules, 2019 (set by the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, Government of India) have released emission standards for 111 antimicrobials in treated effluent originating from bulk drug and formulation units (The Gazette of India, 2020). However, HCQ, ivermectin and other putative anti-COVID-19 agents are not listed. Since the pandemic has resulted in an increased demand for HCQ and antivirals, inclusion of emission standards for these APIs are desirable.

4.1. Landfills and wastewater treatment plants

Hospitals, municipal sewage and manufacturing plants are important sources of both antimicrobials and antibiotic-resistance genes to freshwater bodies. Municipal WWTPs with or without an in-situ pre-treatment step (Giger et al., 2003) often do not sufficiently neutralize antibiotic resistant bacteria and genes, nor remove antimicrobial residues which are further shed into the local environment. For example, WWTPs receiving effluents from hospitals with considerable numbers of COVID-19 patients could be potential reservoirs of antimicrobial residues, antimicrobial resistant bacteria as well as AMR genes that are capable of horizontal transmission into other bacterial species. A risk assessment study conducted in an emergency hospital in the UK suggested that the ratio of predicted environmental concentration to predicted no-effect concentration (PEC: PNEC) would be above 1 for amoxicillin, if around 70% of patients consumed the antibiotic, highlighting a realistic environmental concern for selection of AMR during a pandemic where large proportions of the population are consuming antibiotics, particularly in healthcare settings (Comber et al., 2020). Considering the widespread use of antimicrobials during the pandemic it can be expected that municipal and hospital WWTPs may receive a heavy load of antimicrobials. Microbial forms such as flocs and biofilms are essential for the functioning and stability of sewage treatment plants and high concentrations of antibiotics in wastewaters may exert inhibitory effects on these microbial forms and subsequently compromise the efficacy of sewage treatment (Singer et al., 2008).

Sales of antimicrobial disinfectants and soaps have soared during the pandemic in India (Tandon, 2020). Soaps and disinfectants containing antimicrobials could persist in wastewater biosolids at higher concentrations than that of antibiotics, imposing damage to the ecosystem (McClellan and Halden, 2010). Depending on the physical and chemical properties of the antimicrobial compound and the technology of WWTPs, antimicrobials may undergo precipitation, biodegradation, transformation or sorption onto the activated sludge (Ternes and Joss, 2006). Conventional WWTP processes either partially mineralise antimicrobials or transform them into metabolites with biological activity, resulting in the generation of residues, thereby allowing the entry of these compounds into the environment through effluent discharges or applications of sewage sludge (Miranda and Castillo, 1998; Marcinek et al., 1998; Reinthaler et al., 2003; Lindberg et al., 2005; Silva et al., 2006). Some antimicrobials get transformed into molecules that may have higher or similar antimicrobial effect than that of parent molecule. For example, transformed products of the antibiotic sulfamethoxazole modified at the para-amino group exhibit antibacterial effects like that of the parent molecule whereas its 4-NO2 and 4-OH derivatives have higher inhibitory activity than the parent molecule (Majewsky et al., 2014). Methyltriclosan, a by-product of triclosan following biological treatment, has a mode of action similar to the parent molecular even when triclosan levels are below measurable limits (Lindström et al., 2002). Thus, antimicrobial residues and transformed by products of antimicrobials originating from WWTPs may enable microorganisms to develop resistance through selective sweeps of point mutations or horizontally transferred AMR genes due to selection driven by exposure to these compounds at sub-inhibitory concentrations. Antimicrobials at sub-inhibitory concentrations could promote the expression of efflux pumps and efflux-mediated resistance to antimicrobials (Poole, 2005; Maillard, 2007). Additionally, WWTPs act as a fulcrum in the generation of AMR bacteria due to the high microbial load present and increased availability of nutrients within them (Threedeach et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2015) which may enable their dissemination into various environments.

Municipal solid waste landfills are also sentinels of antimicrobials and AMR residues which can disperse into surrounding environments (Li et al., 2017). It has been predicted that the risk of AMR is increased in populations of 20 million who reside ˂2 km from landfills (Wilson et al., 2015). Antimicrobial residues in landfills could even result in depletion of microbes essential in biogeochemical cycles. This has been demonstrated in a study by Wu et al. (2017) where oxytetracycline present in landfill refuse reduced N2 production capacity by >50% linked to depletion of Rhodothermus sp. and inhibited denitrification in the long term. Practices like long-term landfilling enriches the abundance of antimicrobial resistance genes (Wu et al., 2017) and abandoning these landfills are not an effective solution as antimicrobials can still diffuse out for years (Velpandian et al., 2018). Alarming levels of pharmaceuticals have been recorded in aquifers adjoined to the Ghazipur landfill in 1984 and the leachate from the landfill was found have continuously drained into the river Yamuna (Velpandian et al., 2018). The overuse and misuse of antimicrobials linked to the continuing global pandemic can concentrate such landfills with antimicrobials and may present vital damage to natural ecosystems.

4.2. Water bodies

Lack of access to clean water is one of the pressing issues the world is facing. Studies have documented antimicrobial contamination in water resources including surface water, groundwater and seawater (López-Serna et al., 2013; Zhao et al., 2015; Mahmood et al., 2019). In addition, water mixes up bacteria from the environment, humans and animals which enables the transfer of AMR encoding mobile elements between bacteria and evolution of new AMR encoding mobile elements through recombination of AMR genes and genes for mobile element transfer from an enhanced gene pool. Aquatic ecosystems have a significant ecological and evolutionary role in influencing the emergence, transmission and persistence of AMR and can dampen the efforts taken to reduce the prevalence of AMR in clinical settings (Taylor et al., 2011).

AMR is a huge burden for highly populated areas where clean water, sanitation and hygiene (WaSH) are not stringently followed and unrestricted use of antimicrobials prevails. Since COVID-19 has brought an unprecedented change in antimicrobial consumption and production, it can be presumed that the composition of wastewater generated has changed, introducing new challenges to wastewater management. This inevitably leaves water resources at stake and the biota dependent on it. One study in India has confirmed an increased incidence of Escherichia coli resistant to antibiotics during the pandemic in ambient waterbodies in the city of Ahmedabad where many COVID-19 cases were being reported (Kumar et al., 2021). In many cities of India, a proper WWTP is absent and domestic sewage is directly discharged into aquatic ecosystems. Of crucial importance, AMR is not included in the water quality standards and guidelines of India precisely because of this reason (IS10500, 2012; Kumar et al., 2021).

4.3. Human beings

Besides the empirical use of antimicrobials in clinical settings, another important factor leading to increased antimicrobial consumption is self-medication. Misuse of antimicrobial drugs is common in urban and rural parts of India, due to ease in procuring over-the-counter antibiotics. Social stigma associated with declaring oneself affected by the virus can tempt people to self-medicate. The knowledge that antimicrobials recommended for COVID-19 are readily available without prescription further facilitates the practice of self-medication. The lack of regulation in antimicrobial self-medication in India has supported an increase in the consumption of antimicrobials by 105% between 2000 and 2015, a metric that is expected to increase globally by 63% during 2010–2030 (Klein et al., 2018; GARP-India Working Group, 2011; Van Boeckel et al., 2015). Furthermore, since the beginning of pandemic, the public has been directed to use hand sanitizers and disinfectants as a key infection control intervention. Quaternary ammonium compounds, a common ingredient in many commercially available disinfectants can affect the susceptibility of bacteria to other antibacterial agents when they are present at sub-inhibitory concentrations (Soumet et al., 2012). According to the State of the World's Antibiotics 2021 report, the change in per capita use of antibiotics in India between 2010 and 2020 is 30.64% (Sriram et al., 2021). The increased use of antimicrobials like HCQ and azithromycin during COVID-19 can disrupt the composition of human gut microbiome (Finlay et al., 2021) which could result in serious health consequences. Moreover, consumption of azithromycin has proven to alter the metabolic functioning of the gut microbiome and select for azithromycin resistance in the gut (Doan et al., 2019). Antimicrobial consumption also results in the loss of microbial taxa which are low in number and more susceptible to antimicrobials, and this can alter metabolic and immune functioning of the host (Neuman et al., 2018). The altered manufacturing landscape of APIs during the pandemic can also magnify the risk of AMR. Untreated effluents from manufacturing industries contaminates surface, ground, and drinking water with antimicrobials and human consumption of such polluted water could select for AMR in the intestine.

4.4. Animals and aquatic biota

With numerous studies confirming the presence of antimicrobial resistant bacteria in the gut microbiota of wildlife species such as birds, reptiles, mammals and fish (Gilliver et al., 1999; Sjölund et al., 2008; Wheeler et al., 2012; Bonnedahl and Järhult, 2014), it is apparent that the issue of AMR is not confined to food animals. Ensuing the selection of antimicrobial resistance in the intestinal flora of humans receiving antimicrobial therapy, antimicrobial resistant bacteria and antimicrobial residues are released into the environment through excreta. The antimicrobial residues and their metabolites reaching aquatic resources exert toxic effects to various biological systems (Bilal et al., 2020). Their presence in water causes the enteric bacteria in the gut of aquatic animals to evolve resistance through selection of already existing environmental AMR genes (Arnold et al., 2016). Long-range animal movement further assists the circulation of resistant genes in a global scale making them potential vectors of AMR (Dolejska and Papagiannitsis, 2018).

Aquatic environments provide perfect conditions for horizontal gene transfer and establishment of antimicrobial resistant bacteria (Bhattacharyya et al., 2019). Effluents from sewage treatment plants contain heavy metals, detergents and other pollutants along with antimicrobials that can co-select AMR (Baker-Austin et al., 2006). Run offs from agricultural lands, aquaculture facilities and pharmaceutical industries also introduces antimicrobial products and resistant bacteria into marine and other aquatic ecosystems (Baquero et al., 2008). Antimicrobial resistant genes from aquatic organisms can re-enter into the human and animal microbiota via food chain resulting in a vicious cycle of AMR.

5. Concluding remarks and recommendations

The current pandemic demonstrates how poor planning and preparedness can impact public health. There are no defined borders for microorganisms, which can spread easily from one source to another. Infectious diseases with no reliable therapeutic options can further decimate public health infrastructure. AMR is however a silent pandemic that has worsened in the face of COVID-19 (Mahoney et al., 2021). Ironically, lack of access to antimicrobials and healthcare currently costs more lives than AMR, particularly in resource limited countries (Frost et al., 2019b). However, if the bacteria impacting resource-limited countries develop AMR, then a more catastrophic situation will arise where even those who reach healthcare cannot be treated. The solution will be to address AMR without delay and ensure rational use without affecting accessibility to antimicrobials for those who need them most (Ginsburg and Klugman, 2020). Research studies assessing the prevalence of AMR in humans, animals and environment is required urgently to assess the overall impact of COVID-19 and plan mitigation strategies for the future. Accelerating the COVID-19 vaccination drive in India can also help reduce the incidence of AMR to an extent, as vaccines can reduce the need for hospitalization in patients infected with the virus (Sheikh et al., 2021) and dependency on antimicrobials.

India's national action plan for AMR is a well-structured proposal inclusive of all realms of One Health to tackle AMR. However, the execution of the plan has been slow-paced and requires momentum. So far, only three states of India have proposed an action plan for the containment of AMR (Government of Kerala, 2018; Government of Madhya Pradesh, 2019; Government of NCT of Delhi, 2020). Such initiatives must be introduced from other states as well, since this enables the direct involvement of state governments for effective monitoring and assessment of programs and policies. The absence of a surveillance system monitoring antibiotic usage and AMR from manufacturing sources, animal husbandry, aquaculture and other environmental settings, restricts our understanding on the overall burden of AMR. Hence, it will be necessary to develop an integral AMR surveillance system that is fully inclusive of all sectors of One Health. COVID-19 can increase the prevalence of AMR even in natural environments due to the increase in production and consumption of antimicrobials. According to the Scoping Report on Antimicrobial Resistance in India, only 7% of the research studies conducted on AMR in the environmental scale accounts to industrial effluents (Gandra et al., 2017), a number which is too small considering the volume of antimicrobial production in India. The AMR risks associated with hospital and industrial effluents are largely unknown and demands further research to real solutions to prevent AMR. About 50% of people in rural parts of India are still dependent on pharmacies for treatment as their first choice due to the geographical constraints, affordability and inaccessibility to health care (DownToEarth, 2020). Even though Schedule H1 prohibits the sale of antimicrobials without any prescription, it is often not enforced extensively and over-the-counter sale of antimicrobials still prevails in some parts of India (Satyanarayana et al., 2016). AMR is an issue of social construct and it requires the collective efforts of psychologists, social and environmental scientists in order to frame strategies for behavior and technical interventions in minimising the irrational use of antimicrobials and their inputs to the environment. As much as it is important to educate pharmacists, it is equally important to educate the public on the injudicious use of antimicrobials and its relation to AMR. Inculcating knowledge on AMR and the sensible use of antimicrobials in early education can amend the knowledge gap that exists within the public regarding AMR. India has a history of successful health campaigns like the pulse polio and BCG vaccination drive where social media has aided in reaching out to the masses. Social media has played an immense role in creating awareness about COVID-19 and instilling COVID-19 appropriate behaviours among the public. This model could be extended to disseminate knowledge regarding AMR and appropriate behavioural interventions by public health authorities.

Improving AMR surveillance capacity and antimicrobial stewardship activities will be essential if we are to effectively manage AMR in India. Reinforcement of AMR stewardship activities, revision of environmental policies and antimicrobial policies will not only help in mitigating the current challenge of AMR but could prevent a worsening crisis in any forthcoming third wave of COVID-19 in India.

Credit authorship contribution statement

P.S. Seethalakshmi: Investigation, Writing – original draft; Oliver J Charity: Writing – review & editing; Theodoros Giakoumis: Investigation, Writing – review & editing; George Seghal Kiran: Supervision, Writing – review & editing; Shiranee Sriskandan: Conceptualization, Methodology; Nikolaos Voulvoulis: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing; Joseph Selvin: Conceptualization and Supervision.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

This work has been supported by the Department of Biotechnology (DBT), Ministry of Science and Technology, Government of India and the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) (DBT Reference: BT/IN/Indo-UK/AMR-Env/02/JS/2020-21; NERC Reference: NE/T013184/1). SS acknowledges the support of the NIHR Imperial Biomedical Research Centre.

Compliance with ethical standards

Research involving human participants and/or animals: This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent: This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Editor: Warish Ahmed

References

- Adebisi Y.A., Jimoh N.D., Ogunkola I.O., Uwizeyimana T., Olayemi A.H., Ukor N.A., Lucero-Prisno D.E., III The use of antibiotics in COVID-19 management: a rapid review of national treatment guidelines in 10 african countries. Trop. Med. Health. 2021;49(1):51. doi: 10.1186/s41182-021-00344-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alanio A., Dellière S., Fodil S., Bretagne S., Mégarbane B. Prevalence of putative invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in critically ill patients with COVID-19. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020;8(6):e48–e49. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30237-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali M.R., Sikder M.M.H., Islam M.S., Islam M.S. Investigation of discriminate and indiscriminate use of doxycycline in broiler: an indoor research on antibiotic doxycycline residue study in edible poultry tissue. Asian J. Med. Biol. Res. 2020;6(1):1–7. doi: 10.3329/ajmbr.v6i1.46472. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial Research and Surveillance Network . Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR); 2019. Annual report January 2019- December 2019.http://iamrsn.icmr.org.in/index.php/resources/amr-icmr-data (accessed 14 July 2021) [Google Scholar]

- Arastehfar A., Carvalho A., van de Veerdonk F.L., Jenks J.D., Koehler P., Krause R., Hoenigl M.… COVID-19 associated pulmonary aspergillosis (CAPA)—from immunology to treatment. J. Fungi. 2020;6(2):91. doi: 10.3390/jof6020091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold K.E., Williams N.J., Bennett M. ‘Disperse abroad in the land’: the role of wildlife in the dissemination of antimicrobial resistance. Biol. Lett. 2016;12(8) doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2016.0137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnum P.V. PTSM: Pharmaceutical Technology Sourcing and Management. 2013. The weaknesses and strengths of the Global API market; p. 9.https://www.pharmtech.com/view/weaknesses-and-strengths-global-api-market Available at: (accessed 14 July 2021) [Google Scholar]

- Baker-Austin C., Wright M.S., Stepanauskas R., McArthur J.V. Co-selection of antibiotic and metal resistance. Trends Microbiol. 2006;14(4):176–182. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2006.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baquero F., Martínez J.L., Cantón R. Antibiotics and antibiotic resistance in water environments. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2008;19(3):260–265. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beadling C., Slifka M.K. How do viral infections predispose patients to bacterial infections? Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2004;17(3):185–191. doi: 10.1097/00001432-200406000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bengoechea J.A., Bamford C.G. SARS-CoV-2, bacterial co-infections, and AMR: the deadly trio in COVID-19? EMBO Mol. Med. 2020;12(7) doi: 10.15252/emmm.202012560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bengtsson-Palme J., Boulund F., Fick J., Kristiansson E., Larsson D.G. Shotgun metagenomics reveals a wide array of antibiotic resistance genes and mobile elements in a polluted lake in India. Front. Microbiol. 2014;5:648. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beović B., Doušak M., Ferreira-Coimbra J., Nadrah K., Rubulotta F., Belliato M., Berger-Estilita J., Ayoade F., Rello J., Erdem H. Antibiotic use in patients with COVID-19: a 'snapshot' infectious diseases international research initiative (ID-IRI) survey. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2020;75(11):3386–3390. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkaa326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya A., Haldar A., Bhattacharyya M., Ghosh A. Anthropogenic influence shapes the distribution of antibiotic resistant bacteria (ARB) in the sediment of sundarban estuary in India. Sci. Total Environ. 2019;647:1626–1639. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilal M., Mehmood S., Rasheed T., Iqbal H.M. Antibiotics traces in the aquatic environment: persistence and adverse environmental impact. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health. 2020;13:68–74. doi: 10.1016/j.coesh.2019.11.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blaize M., Mayaux J., Nabet C., Lampros A., Marcelin A.G., Thellier M., Piarroux R., Demoule A., Fekkar A. Fatal invasive aspergillosis and coronavirus disease in an immunocompetent patient. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020;26(7):1636–1637. doi: 10.3201/eid2607.201603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnedahl J., Järhult J.D. Antibiotic resistance in wild birds. Ups. J. Med. Sci. 2014;119(2):113–116. doi: 10.3109/03009734.2014.905663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boxall A.B., Kolpin D.W., Halling-Sørensen B., Tolls J. Peer reviewed: are veterinary medicines causing environmental risks? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2003;37(15):286A–294A. doi: 10.1021/es032519b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantón R., Gijón D., Ruiz-Garbajosa P. Antimicrobial resistance in ICUs: an update in the light of the COVID-19 pandemic. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care. 2020;26(5):433–441. doi: 10.1097/mcc.0000000000000755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey M.E., Jain R., Yousuf M., Maes M., Dyson Z.A., Thu T.N.H., Taneja N.… Spontaneous emergence of azithromycin resistance in independent lineages of salmonella typhi in northern India. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021;72(5):e120–e127. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Changing Markets Superbugs in the Supply Chain, 2016: how pollution from antibiotics factories in India and China is fuelling the global rise of drug-resistant infections. 2021. https://epha.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Superbugsinthesupplychain_CMreport.pdf (accessed 13 July 2021)

- Chedid M., Waked R., Haddad E., Chetata N., Saliba G., Choucair J. Antibiotics in treatment of COVID-19 complications: a review of frequency, indications, and efficacy. J. Infect. Public Health. 2021;14(5):570. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2021.02.001. 10.1016%2Fj.jiph.2021.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen N., Zhou M., Dong X., Qu J., Gong F., Han Y., Zhang L.… Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhary A., Tarai B., Singh A., Sharma A. Multidrug-resistant Candida auris infections in critically ill coronavirus disease patients, India, april-july 2020. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020;26(11):2694–2696. doi: 10.3201/eid2611.203504. 10.3201%2Feid2611.203504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comber S.D., Upton M., Lewin S., Powell N., Hutchinson T.H. COVID-19, antibiotics and one health: a UK environmental risk assessment. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2020;75(11):3411–3412. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkaa338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COVID-19 rapid guideline: managing COVID-19 NICE guideline. 2021. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng191/resources/covid19-rapid-guideline-managing-covid19-pdf-51035553326 Published: 23 March. (accessed 2 July 2021)

- COVID-19 rapid guideline: managing suspected or confirmed pneumonia in adults in the community NICE guideline [NG165] 2020. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng165#antibiotic-treatment (accessed 2 July 2021) [PubMed]

- Dent J.A., Smith M.M., Vassilatis D.K., Avery L. The genetics of ivermectin resistance in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2000;97(6):2674–2679. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.6.2674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doan T., Hinterwirth A., Worden L., Arzika A.M., Maliki R., Abdou A., Lietman T.M.… Gut microbiome alteration in MORDOR I: a community-randomized trial of mass azithromycin distribution. Nat. Med. 2019;25(9):1370–1376. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0533-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolejska M., Papagiannitsis C.C. Plasmid-mediated resistance is going wild. Plasmid. 2018;99:99–111. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2018.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DownToEarth: what should India do to control antimicrobial resistance. 2020. https://www.downtoearth.org.in/blog/health/what-should-india-do-to-control-antimicrobial-resistance-74267 (Accessed: 17 October 2021)

- Finlay B.B., Amato K.R., Azad M., Blaser M.J., Bosch T.C., Chu H., Giles-Vernick T.… The hygiene hypothesis, the COVID pandemic, and consequences for the human microbiome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2021;118(6) doi: 10.1073/pnas.2010217118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost I., Craig J., Joshi J., Faure K., Laxminarayan R. Center for Disease Dynamics, Economics & Policy; Washington, DC: 2019. Access barriers to antibiotics.https://cddep.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/AccessBarrierstoAntibiotics_CDDEP_FINAL.pdf (accessed 12 July 2021) [Google Scholar]

- Frost I., Van Boeckel T.P., Pires J., Craig J., Laxminarayan R. Global geographic trends in antimicrobial resistance: the role of international travel. J. Travel Med. 2019;26(8) doi: 10.1093/jtm/taz036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gade V., Bajaj N., Sonarkar S., Radke S., Kokane N., Rahul N. Mucormycosis: tsunami of fungal infection after second wave of COVID-19. Ann. Rom. Soc. Cell Biol. 2021;25(6):6383–6390. https://www.annalsofrscb.ro/index.php/journal/article/view/6700 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Gale J., Shrivastava B. BloombergQuint; 2020. Antibiotics for Covid cases worsen India’s superbug crisis.https://www.bloombergquint.com/coronavirus-outbreak/antibiotics-for-covid-patients-worsen-india-s-superbug-plight May 25. (accessed 14 July 2021) [Google Scholar]

- Gandra S., Mojica N., Klein E.Y., Ashok A., Nerurkar V., Kumari M., Laxminarayan R.… Trends in antibiotic resistance among major bacterial pathogens isolated from blood cultures tested at a large private laboratory network in India, 2008–2014. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2016;50:75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2016.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandra S., Joshi J., Trett A., Lamkang A.S., Laxminarayan R. Center for Disease Dynamics, Economics & Policy; Washington, DC: 2017. Scoping report on antimicrobial resistance in India.https://cddep.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/AMR-INDIA-SCOPING-REPORT.pdf (accessed 14 July 2021) [Google Scholar]

- Gandra S., Tseng K.K., Arora A., Bhowmik B., Robinson M.L., Panigrahi B., Klein E.Y.… The mortality burden of multidrug-resistant pathogens in India: a retrospective, observational study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2019;69(4):563–570. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Vidal C., Sanjuan G., Moreno-García E., Puerta-Alcalde P., Garcia-Pouton N., Chumbita M., Torres A.… Incidence of co-infections and superinfections in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2021;27(1):83–88. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.07.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautret P., Lagier J.C., Parola P., Meddeb L., Mailhe M., Doudier B., Raoult D.… Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as a treatment of COVID-19: results of an open-label non-randomized clinical trial. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2020;56(1) doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Getahun H., Smith I., Trivedi K., Paulin S., Balkhy H.H. Tackling antimicrobial resistance in the COVID-19 pandemic. Bull. World Health Organ. 2020;98(7):442. doi: 10.2471/BLT.20.268573. 10.2471%2FBLT.20.268573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S., Bornman C., Zafer M.M. Antimicrobial resistance threats in the emerging COVID-19 pandemic: where do we stand? J. Infect. Public Health. 2021;14(5):555–560. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2021.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giger W., Alder A.C., Golet E.M., Kohler H.P.E., McArdell C.S., Molnar E., Suter M.J.F. Occurrence and fate of antibiotics as trace contaminants in wastewaters, sewage sludges, and surface waters. CHIMIA Int. J. Chem. 2003;57(9):485–491. doi: 10.2533/000942903777679064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbertson T.J., Hornish R.E., Jaglan P.S., Koshy K.T., Nappier J.L., Stahl G.L., Kubicek M.F.… Environmental fate of ceftiofur sodium, a cephalosporin antibiotic. Role of animal excreta in its decomposition. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1990;38(3):890–894. [Google Scholar]

- Gilliver M.A., Bennett M., Begon M., Hazel S.M., Hart C.A. Antibiotic resistance found in wild rodents. Nature. 1999;401(6750):233–234. doi: 10.1038/45724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsburg A.S., Klugman K.P. COVID-19 pneumonia and the appropriate use of antibiotics. Lancet Glob. Health. 2020;8(12):e1453–e1454. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30444-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Global Antibiotic Resistance Partnership (GARP)-India Working Group Rationalizing antibiotic use to limit antibiotic resistance in India+ Indian J. Med. Res. 2011;134(3):281. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Göbel A., McArdell C.S., Suter M.J.F., Giger W. Trace determination of macrolide and sulfonamide antimicrobials, a human sulfonamide metabolite, and trimethoprim in wastewater using liquid chromatography coupled to electrospray tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2004;76(16):4756–4764. doi: 10.1021/ac0496603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gothwal R., Shashidhar Occurrence of high levels of fluoroquinolones in aquatic environment due to effluent discharges from bulk drug manufacturers. J. Hazard. Toxic Radioact. Waste. 2017;21(3) (Accessed: 17 October 2021) [Google Scholar]

- Government of Bihar Management of COVID-19 cases in Bihar. 2021. https://state.bihar.gov.in/health/cache/19/17-Jun-21/SHOW_DOCS/74(H.S)%20-%2021.04.2021%20(1).pdf accessed 10 May 2021.

- Government of Kerala Kerala antimicrobial resistance strategic action plan one health response to AMR containment. 2018. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/searo/india/antimicrobial-resistance/karsap-keralaantimicrobialresistancestrategicactionplan.pdf?sfvrsn=ccaa481a_2 Accessed on 16 October 2021.

- Government of Madhya Pradesh Madhya Pradesh state action plan to combat antimicrobial resistance in Delhi. 2019. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/searo/india/antimicrobial-resistance/mp-state-action-plan-for-containment-of-antimicrobial-resistance-final.pdf?sfvrsn=a06ee216_2 Accessed on 16 October 2021.

- Government of Maharashtra Standard treatment protocol for COVID-19. 2020. https://www.nmcnagpur.gov.in/assets/250/2020/07/mediafiles/22_July_2020_Standard_Treatment_Protocol_Revision_4.pdf accessed 10 May 2021.

- Government of NCT of Delhi State action plan to combat antimicrobial resistance in Delhi. 2020. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/searo/india/antimicrobial-resistance/sapcard-final.pdf?sfvrsn=83eb02f4_2 Accessed on 16 October 2021.

- Health and Family welfare department. Government of West Bengal Top sheet for the management of COVID-19 patients. 2021. https://www.wbhealth.gov.in/uploaded_files/corona/Top_Sheet_for_Covid-19_with_sig.pdf (accessed 10 May 2021)

- Hughes S., Troise O., Donaldson H., Mughal N., Moore L.S. Bacterial and fungal coinfection among hospitalized patients with COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study in a UK secondary-care setting. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2020;26(10):1395–1399. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Human pharmaceuticals, hormones and fragrances, Human pharmaceuticals, hormones and fragrances. In: T. Ternes A. Joss (Eds.), The Challenge of Micropollutants in Urban Water Management. IWA Publishing. doi:10.2166/9781780402468.

- IS10500 B.I.S. Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS); New Delhi: 2012. Indian standard drinking water–specification (second revision)http://cgwb.gov.in/Documents/WQ-standards.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Jin Y.H., Cai L., Cheng Z.S., Cheng H., Deng T., Fan Y.P., Wang X.H.… A rapid advice guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) infected pneumonia (standard version) Mil. Med. Res. 2020;7(1):1–23. doi: 10.1186/s40779-020-0233-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kampmeier S., Tönnies H., Correa-Martinez C.L., Mellmann A., Schwierzeck V. A nosocomial cluster of vancomycin resistant enterococci among COVID-19 patients in an intensive care unit. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 2020;9(1):1–6. doi: 10.1186/s13756-020-00820-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaul G., Shukla M., Dasgupta A., Chopra S. 2019. Update on Drug-repurposing: Is it Useful for Tackling Antimicrobial Resistance? [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khurana S., Singh P., Sharad N., Kiro V.V., Rastogi N., Lathwal A., Mathur P.… Profile of co-infections & secondary infections in COVID-19 patients at a dedicated COVID-19 facility of a tertiary care Indian hospital: implication on antimicrobial resistance. Indian J. Med. Microbiol. 2021;39(2):147–153. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmmb.2020.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein E.Y., Van Boeckel T.P., Martinez E.M., Pant S., Gandra S., Levin S.A., Laxminarayan R.… Global increase and geographic convergence in antibiotic consumption between 2000 and 2015. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2018;115(15):E3463–E3470. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1717295115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koehler P., Cornely O.A., Böttiger B.W., Dusse F., Eichenauer D.A., Fuchs F., Shimabukuro-Vornhagen A.… COVID-19 associated pulmonary aspergillosis. Mycoses. 2020;63(6):528–534. doi: 10.1111/myc.13096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar M., Dhangar K., Thakur A.K., Ram B., Chaminda T., Sharma P., Barcelo D.… Antidrug resistance in the Indian ambient waters of Ahmedabad during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021;126125 doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.126125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancet The. India's COVID-19 emergency. Lancet (London, England) 2021;397(10286):1683. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01052-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langford B.J., So M., Raybardhan S., Leung V., Soucy J.P.R., Westwood D., MacFadden D.R.… Antibiotic prescribing in patients with COVID-19: rapid review and meta-analysis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson D.J., de Pedro C., Paxeus N. Effluent from drug manufactures contains extremely high levels of pharmaceuticals. J. Hazard. Mater. 2007;148(3):751–755. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2007.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L.G., Xia Y., Zhang T. Co-occurrence of antibiotic and metal resistance genes revealed in complete genome collection. ISME J. 2017;11(3):651–662. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2016.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg R.H., Wennberg P., Johansson M.I., Tysklind M., Andersson B.A. Screening of human antibiotic substances and determination of weekly mass flows in five sewage treatment plants in Sweden. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005;39(10):3421–3429. doi: 10.1021/es048143z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindström A., Buerge I.J., Poiger T., Bergqvist P.A., Müller M.D., Buser H.R. Occurrence and environmental behavior of the bactericide triclosan and its methyl derivative in surface waters and in wastewater. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2002;36(11):2322–2329. doi: 10.1021/es0114254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Serna R., Jurado A., Vázquez-Suñé E., Carrera J., Petrović M., Barceló D. Occurrence of 95 pharmaceuticals and transformation products in urban groundwaters underlying the metropolis of Barcelona, Spain. Environ. Pollut. 2013;174:305–315. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2012.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood A.R., Al-Haideri H.H., Hassan F.M. Detection of antibiotics in drinking water treatment plants in Baghdad City, Iraq. Adv. Public Health. 2019;2019 doi: 10.1155/2019/7851354. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney A.R., Safaee M.M., Wuest W.M., Furst A.L. The silent pandemic: emergent antibiotic resistances following the global response to SARS-CoV-2. Iscience. 2021;102304 doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2021.102304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maillard J.Y. Bacterial resistance to biocides in the healthcare environment: should it be of genuine concern? J. Hosp. Infect. 2007;65:60–72. doi: 10.1016/S0195-6701(07)60018-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majewsky M., Wagner D., Delay M., Bräse S., Yargeau V., Horn H. Antibacterial activity of sulfamethoxazole transformation products (TPs): general relevance for sulfonamide TPs modified at the para position. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2014;27(10):1821–1828. doi: 10.1021/tx500267x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcinek H., Wirth R., Muscholl-Silberhorn A., Gauer M. Enterococcus faecalis gene transfer under natural conditions in municipal sewage water treatment plants. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1998;64(2):626–632. doi: 10.1128/AEM.64.2.626-632.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClellan K., Halden R.U. Pharmaceuticals and personal care products in archived US biosolids from the 2001 EPA national sewage sludge survey. Water Res. 2010;44(2):658–668. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2009.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Memish Z.A., Perlman S., Van Kerkhove M.D., Zumla A. Middle East respiratory syndrome. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1063–1077. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)33221-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health &. Family Welfare (MoHFW) Government of India guidelines on clinical management of COVID-19. 2020. https://www.mohfw.gov.in/pdf/RevisedNationalClinicalManagementGuidelineforCOVID1931032020.pdf (accessed 10 May 2021)

- Ministry of Health &. Family Welfare (MoHFW) Government of India. Clinical guidance for management of adult COVID-19 patients. 2021. https://www.icmr.gov.in/pdf/covid/techdoc/COVID_Management_Algorithm_17052021.pdf (accessed 10 May 2021)

- Miranda C.D., Castillo G. Resistance to antibiotic and heavy metals of motile aeromonads from Chilean freshwater. Sci. Total Environ. 1998;224(1–3):167–176. doi: 10.1016/S0048-9697(98)00354-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morens D.M., Taubenberger J.K., Fauci A.S. Predominant role of bacterial pneumonia as a cause of death in pandemic influenza: implications for pandemic influenza preparedness. J. Infect. Dis. 2008;198(7):962–970. doi: 10.1086/591708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moretto F., Sixt T., Devilliers H., Abdallahoui M., Eberl I., Rogier T., Piroth L.… Is there a need to widely prescribe antibiotics in patients hospitalized with COVID-19? Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021;105:256–260. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.01.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris D.P. Bacterial biofilm in upper respiratory tract infections. Curr. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2007;9(3):186–192. doi: 10.1007/s11908-007-0030-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray A.K. The novel coronavirus COVID-19 outbreak: global implications for antimicrobial resistance. Front. Microbiol. 2020;11:1020. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustafa L., Tolaj I., Baftiu N., Fejza H. Use of antibiotics in COVID-19 ICU patients. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2021;15(04):501–505. doi: 10.3855/jidc.14404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagpur Municipal Corporation Maharashtra COVID-19 task force recommendations for the management of hospitalised COVID-19 patients. 2021. https://www.nmcnagpur.gov.in/assets/250/2021/04/mediafiles/COVID_latest_guidelines.pdf accessed 10 May 2021.

- Nahar S. Understanding how the Indian pharmaceutical industry works – part 2. 2020. https://www.alphainvesco.com/blog/understanding-how-the-indian-pharmaceutical-industry-works-part-2/ accessed 10 May 2021.

- Nehara H.R., Puri I., Singhal V., Sunil I.H., Bishnoi B.R., Sirohi P. Rhinocerebral mucormycosis in COVID-19 patient with diabetes a deadly trio: case series from the north-western part of India. Indian J. Med. Microbiol. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.ijmmb.2021.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuman H., Forsythe P., Uzan A., Avni O., Koren O. Antibiotics in early life: dysbiosis and the damage done. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2018;42(4):489–499. doi: 10.1093/femsre/fuy018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwlaat R., Mbuagbaw L., Mertz D., Burrows L.L., Bowdish D.M., Moja L., Schünemann H.J. Coronavirus Disease 2019 and antimicrobial resistance: parallel and interacting health emergencies. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021;72(9):1657–1659. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordmann P., Naas T., Poirel L. Global spread of Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2011;17(10):1791–1798. doi: 10.3201/eid1710.110655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nori P., Szymczak W., Puius Y., Sharma A., Cowman K., Gialanella P., Fleischner Z., Corpuz M., Torres-Isasiga J., Bartash R., Felsen U., Chen V., Guo Y. Emerging co-pathogens: New Delhi Metallo-beta-lactamase producing Enterobacterales infections in New York City COVID-19 patients. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2020;56(6) doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.106179. 10.1016%2Fj.ijantimicag.2020.106179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill J. Antimicrobial resistance. Tackling a crisis for the health and wealth of nations. 2014. https://www.who.int/antimicrobial-resistance/news/amr-newsletter-no13-july2016.pdf (Accessed: 17 October 2021)

- Osei-Atweneboana M.Y., Awadzi K., Attah S.K., Boakye D.A., Gyapong J.O., Prichard R.K. Phenotypic evidence of emerging ivermectin resistance in Onchocerca volvulus. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2011;5(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole K. Efflux-mediated antimicrobial resistance. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2005;56(1):20–51. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porretta A.D., Baggiani A., Arzilli G., Casigliani V., Mariotti T., Mariottini F., Privitera G.P.… Increased risk of acquisition of New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase-producing carbapenem-resistant enterobacterales (NDM-CRE) among a cohort of COVID-19 patients in a teaching hospital in Tuscany, Italy. Pathogens. 2020;9(8):635. doi: 10.3390/pathogens9080635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posteraro B., Torelli R., Vella A., Leone P.M., De Angelis G., De Carolis E., Fantoni M.… Pan-echinocandin-resistant Candida glabrata bloodstream infection complicating COVID-19: a fatal case report. J. Fungi. 2020;6(3):163. doi: 10.3390/jof6030163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakash H., Chakrabarti A. Epidemiology of mucormycosis in India. Microorganisms. 2021;9(3):523. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms9030523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Principi N., Esposito S. Chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine for prophylaxis of COVID-19. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020;20(10):1118. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30296-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawlinson W.D., Waliuzzaman Z., Carter I.W., Belessis Y.C., Gilbert K.M., Morton J.R. Asthma exacerbations in children associated with rhinovirus but not human metapneumovirus infection. J. Infect. Dis. 2003;187(8):1314–1318. doi: 10.1086/368411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawson T.M., Ming D., Ahmad R., Moore L., Holmes A.H. Antimicrobial use, drug-resistant infections and COVID-19. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2020;18(8):409–410. doi: 10.1038/s41579-020-0395-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawson T.M., Moore L.S., Zhu N., Ranganathan N., Skolimowska K., Gilchrist M., Holmes A.… Bacterial and fungal coinfection in individuals with coronavirus: a rapid review to support COVID-19 antimicrobial prescribing. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020;71(9):2459–2468. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinthaler F.F., Posch J., Feierl G., Wüst G., Haas D., Ruckenbauer G., Marth E.… Antibiotic resistance of E. coli in sewage and sludge. Water Res. 2003;37(8):1685–1690. doi: 10.1016/S0043-1354(02)00569-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ripa M., Galli L., Poli A., Oltolini C., Spagnuolo V., Mastrangelo A., Vinci C.… Secondary infections in patients hospitalized with COVID-19: incidence and predictive factors. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2021;27(3):451–457. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts P.H., Thomas K.V. The occurrence of selected pharmaceuticals in wastewater effluent and surface waters of the lower Tyne catchment. Sci. Total Environ. 2006;356(1-3):143–153. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2005.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutgersson C., Fick J., Marathe N., Kristiansson E., Janzon A., Angelin M., Larsson D.J.… Fluoroquinolones and qnr genes in sediment, water, soil, and human fecal flora in an environment polluted by manufacturing discharges. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014;48(14):7825–7832. doi: 10.1021/es501452a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutsaert L., Steinfort N., Van Hunsel T., Bomans P., Naesens R., Mertes H., Van Regenmortel N.… COVID-19-associated invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. Ann. Intensive Care. 2020;10:1–4. doi: 10.1186/s13613-020-00686-4. 10.1186%2Fs13613-020-00686-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salehi M., Ahmadikia K., Badali H., Khodavaisy S. Opportunistic fungal infections in the epidemic area of COVID-19: a clinical and diagnostic perspective from Iran. Mycopathologia. 2020;185(4):607–611. doi: 10.1007/s11046-020-00472-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samarasekera U. India grapples with second wave of COVID-19. The Lancet Microbe. 2021;2(6) doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(21)00123-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satyanarayana S., Kwan A., Daniels B., Subbaraman R., McDowell A., Bergkvist S., Pai M.… Use of standardised patients to assess antibiotic dispensing for tuberculosis by pharmacies in urban India: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2016;16(11):1261–1268. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30215-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen M., Lahane S., Lahane T.P., Parekh R., Honavar S.G. Mucor in a viral land: a tale of two pathogens. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2021;69(2):244–252. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_3774_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheikh A., McMenamin J., Taylor B., Robertson C. SARS-CoV-2 Delta VOC in Scotland: demographics, risk of hospital admission, and vaccine effectiveness. Lancet. 2021 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01358-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva J., Castillo G., Callejas L., López H., Olmos J. Frequency of transferable multiple antibiotic resistance amongst coliform bacteria isolated from a treated sewage effluent in Antofagasta, Chile. Electron. J. Biotechnol. 2006;9(5) [Google Scholar]

- Singer A.C., Howard B.M., Johnson A.C., Knowles C.J., Jackman S., Accinelli C., Watts C.… Meeting report: risk assessment of Tamiflu use under pandemic conditions. Environ. Health Perspect. 2008;116(11):1563–1567. doi: 10.1289/ehp.11310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A.K., Singh R., Joshi S.R., Misra A. Mucormycosis in COVID-19: a systematic review of cases reported worldwide and in India. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2021.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S., Pal N., Chander J., Sardana R., Mahajan B., Joseph N., Ghosh A. Mucormycosis caused by Syncephalastrum spp.: clinical profile, molecular characterization, antifungal susceptibility and review of literature. Clin. Infect. Pract. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.clinpr.2021.100074. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sjölund M., Bonnedahl J., Hernandez J., Bengtsson S., Cederbrant G., Pinhassi J., Olsen B.… Dissemination of multidrug-resistant bacteria into the Arctic. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2008;14(1):70. doi: 10.3201/eid1401.070704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song G., Liang G., Liu W. Fungal co-infections associated with global COVID-19 pandemic: a clinical and diagnostic perspective from China. Mycopathologia. 2020;1–8 doi: 10.1007/s11046-020-00462-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soumet C., Fourreau E., Legrandois P., Maris P. Resistance to phenicol compounds following adaptation to quaternary ammonium compounds in Escherichia coli. Vet. Microbiol. 2012;158(1–2):147–152. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2012.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sriram A., Kalanxhi E., Kapoor G., Craig J., Balasubramanian R., Brar S., Criscuolo N., Hamilton A., Klein E., Tseng K., Van Boeckel T., Laxminarayan R. Center for Disease Dynamics, Economics & Policy; Washington DC: 2021. State of the world's antibiotics 2021: a global analysis of antimicrobial resistance and its drivers.https://cddep.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/The-State-of-the-Worlds-Antibiotics-2021.pdf (Acessed 02 October 2021) [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland C.J., Haustein T., Gadalla N., Armstrong M., Doherty J.F., Chiodini P.L. Chloroquine-resistant Plasmodium falciparum infections among UK travellers returning with malaria after chloroquine prophylaxis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2007;59(6):1197–1199. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tandon S. Covid drives growth in germ-protection soaps category over beauty. Mint. 2020. https://www.livemint.com/industry/retail/covid-drives-growth-in-anti-bacterial-soaps-category-over-beauty-11594537156083.html (accessed 14 July 2021)

- Taylor N.G., Verner-Jeffreys D.W., Baker-Austin C. Aquatic systems: maintaining, mixing and mobilising antimicrobial resistance? Trends Ecol. Evol. 2011;26(6):278–284. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Economic Times Eight global pharmaceutical firms evince interest in India's plan to ramp up API production: Mansukh Mandaviya. 2020. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/industry/healthcare/biotech/pharmaceuticals/eight-global-pharmaceutical-firms-evince-interest-in-indias-plan-to-ramp-up-api-production-mansukh-mandaviya/articleshow/76201809.cms?from=mdr (accessed 1 July 2021)

- The Gazette of India Ministry of environment, forest and climate change notification. 2020. http://moef.gov.in/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/finalization.pdf (accessed 14 July 2021)

- The Hans India Pharma still pollutes Patancheru. 2015. http://www.thehansindia.com/posts/index/Telangana/2015-11-28/Pharma-still-pollutes-Patancheru/189407 (accessed 14 July 2021)

- The Times of India 37 pharma firms get Gujarat FDCA nod for azithromycin. 2020. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/ahmedabad/37-pharma-firms-get-gujarat-fdca-nod-for-azithromycin/articleshow/75730482.cms (accessed 14 July 2021)

- Threedeach S., Chiemchaisri W., Watanabe T., Chiemchaisri C., Honda R., Yamamoto K. Antibiotic resistance of Escherichia coli in leachates from municipal solid waste landfills: comparison between semi-aerobic and anaerobic operations. Bioresour. Technol. 2012;113:253–258. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2012.01.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaidyanathan G. Coronavirus variants are spreading in India—what scientists know so far. Nature. 2021;593:321. doi: 10.1038/d41586-021-01274-7. (accessed 1 July 2021) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Boeckel T.P., Brower C., Gilbert M., Grenfell B.T., Levin S.A., Robinson T.P., Laxminarayan R.… Global trends in antimicrobial use in food animals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2015;112(18):5649–5654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1503141112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velpandian T., Halder N., Nath M., Das U., Moksha L., Gowtham L., Batta S.P. Un-segregated waste disposal: an alarming threat of antimicrobials in surface and ground water sources in Delhi. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018;25(29):29518–29528. doi: 10.1007/s11356-018-2927-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]