Abstract

Intracellular condensates formed through liquid–liquid phase separation (LLPS) primarily contain proteins and RNA. Recent evidence points to major contributions of RNA self-assembly in the formation of intracellular condensates. As the majority of previous studies on LLPS have focused on protein biochemistry, effects of biological RNAs on LLPS remain largely unexplored. In this study, we investigate the effects of crowding, metal ions, and RNA structure on formation of RNA condensates lacking proteins. Using bacterial riboswitches as a model system, we first demonstrate that LLPS of RNA is promoted by molecular crowding, as evidenced by formation of RNA droplets in the presence of polyethylene glycol (PEG 8K). Crowders are not essential for LLPS, however. Elevated Mg2+ concentrations promote LLPS of specific riboswitches without PEG. Calculations identify key RNA structural and sequence elements that potentiate the formation of PEG-free condensates; these calculations are corroborated by key wet-bench experiments. Based on this, we implement structure-guided design to generate condensates with novel functions including ligand binding. Finally, we show that RNA condensates help protect their RNA components from degradation by nucleases, suggesting potential biological roles for such higher-order RNA assemblies in controlling gene expression through RNA stability. By utilizing both natural and artificial RNAs, our study provides mechanistic insight into the contributions of intrinsic RNA properties and extrinsic environmental conditions to the formation and regulation of condensates comprised of RNAs.

Keywords: condensate, RNA structure, riboswitch

INTRODUCTION

Subcellular organization of biomolecules such as RNAs and proteins is key to the regulation of cellular biology. Recent evidence points to important roles for membrane-less organelles or intracellular condensates (ICs) such as stress granules (SGs), P-granules, and Cajal bodies, among others, in the spatial organization of biomolecules (Gomes and Shorter 2019). Studies suggest that these ICs form through liquid–liquid phase separation (LLPS) of biopolymers (Brangwynne et al. 2009; Alberti 2017). Associative interactions such as H-bonding, charge-charge contacts, cation-pi interactions, and hydrophobic interactions play important roles for the formation of ICs that contain RNA and proteins (Gomes and Shorter 2019). Furthermore, RNA-containing complex coacervates, which also form by LLPS and lack lipid bilayer membranes, have also been implicated in origins of life as bioreactors, where encapsulated nucleotides, magnesium, and RNA molecules increase in local concentration (Koga et al. 2011; Poudyal et al. 2018). Our group previously demonstrated that increase in concentration of biomolecules within condensates can activate RNA enzymes (Poudyal et al. 2019a). As the structure of RNA can dictate which parts of the molecule are available for associative interactions, RNA structure likely plays important roles for its encapsulation within the condensates. Despite concrete evidence of RNA encapsulation and enrichment in diverse artificial and biological condensates (Aumiller et al. 2016; Frankel et al. 2016; Drobot et al. 2018; Boeynaems et al. 2019; Poudyal et al. 2019a), little is known about how intrinsic properties of RNAs such as structure and sequence affect their encapsulation within condensates formed by associative LLPS.

Several key observations point to essential roles for base-pairing in the assembly of intracellular condensates; however, the structural context for such base-pairing interactions has not been clearly established. In vitro, base-paired DNA has been reported to be less potent at forming condensates with polylysine compared to single stranded DNA (Shakya and King 2018). Furthermore, in the case of droplets composed entirely of DNA, reprogramming of complementarity was shown to enable association of unique droplets (Jeon et al. 2020). RNAs containing CAG and CUG trinucleotide repeats, which are associated with neurodegenerative phenotypes (Nalavade et al. 2013), can self-assemble into droplets both in vitro and in vivo (Jain and Vale 2017). The mode of condensate assembly by such RNAs is likely due to the high propensity for GC base-pairing, which can form extended networks of RNAs. More recently, RNAs with known structure such as G-quadruplexes have also been shown to form condensates in the presence of crowding agent in vitro (Zhang et al. 2019). In this case, condensate assembly is likely driven by the formation of trans G-quadruplex, which can bring together multiple strands of RNA. Furthermore, RNA has been shown to stimulate formation of condensates with MEG-3 and PGL-3 P-granule proteins both in vitro and in vivo (Smith et al. 2016; Putnam et al. 2019). Interestingly, highly structured ribosomal RNA does not stimulate formation of PGL-3 condensates until the RNA is heat denatured, supporting the importance of exchanging intramolecular base-pairing interactions with intermolecular ones in condensate assembly (Saha et al. 2016). Total RNAs from yeast have also been shown to form condensates in the presence of crowding agents or polyamines (Van Treeck et al. 2018). Furthermore, changes in salt conditions have been reported to dramatically impact the constituents of RNP condensates, with high concentrations of salt favoring RNA-rich condensates by depleting proteins (Onuchic et al. 2019). Precipitation of DNA molecules in a length-dependent manner has also been observed in the presence of polyethylene glycol (PEG) and Mg2+ or NaCl (Paithankar and Prasad 1991). Furthermore, long mRNAs generated from rolling circle transcription have been shown to form RNA nanoparticles through multimerization (Kim et al. 2015). Recently, it has been shown that addition of dimerization elements to RNA can significantly alter material properties of the RNP condensates, suggesting important roles for RNA–RNA interactions in such condensates (Ma et al. 2021). These studies point to important contributions of both intrinsic (e.g., structure and sequence of RNA) and extrinsic factors (e.g., crowding, metal cations, and polyions) in facilitating LLPS of RNAs.

In this study, we sought to understand the contribution of RNA structure toward formation of condensates through LLPS. To that end, we used riboswitches as model RNAs to build several artificial condensates, which allowed us to isolate specific structural features in RNAs that potentiate condensate formation. We first demonstrate that in molecularly crowded conditions from PEG, RNA condensation is non-specific, while in the absence of crowding agents, RNA condensation is sequence- and structure-specific. We further show that RNAs that have a high-propensity to form oligomers (dimers up to hexamers) are prone to LLPS. Our study suggests that self-complementary (palindromes) and non-self-complementary sequences in the unpaired regions of the structure play key roles in RNA multimerization and affect condensate formation. To test these principles, we apply RNA structural engineering and generate condensates with novel properties, also introducing functional domains within the network of RNA interactions involved in the assembly of condensates. Finally, we show that RNA-based condensates help protect RNA from degradation by a ribonuclease, suggesting potential roles for LLPS in RNA stabilization.

RESULTS

Molecular crowding induces condensation of bacterial riboswitches

Several studies on RNA condensation provided initial insights on role of RNA sequence on assembly of condensates. For example, homopolymeric RNAs have been shown to undergo liquid–liquid phase separation in the presence of molecular crowders or sufficient divalent ions (Van Treeck et al. 2018; Boeynaems et al. 2019; Onuchic et al. 2019). While an important step forward, such homopolymers of RNAs have little structure, and so contributions of RNA secondary and tertiary structures toward assembly of condensates cannot be deduced. At the other extreme, total RNAs from yeast have been shown to form condensates under specific conditions; while biologically relevant, the heterogeneity in RNA identity prevents delineating effects of individual RNA base pairs or specific structural domains toward the mechanism of assembly of condensates (Van Treeck et al. 2018). To address this gap, we chose bacterial riboswitches as structured but tractable model RNAs to understand how external environment and RNA sequence and structural features facilitate formation of condensates.

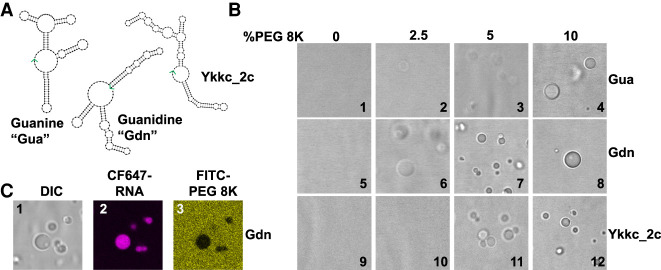

We first sought to understand whether some bacterial riboswitches could form RNA condensates in a structure-dependent manner. We chose the guanine (Gua) (Mandal et al. 2003), guanidine (Gdn) (Nelson et al. 2017), and ykkc_2C riboswitches (Sherlock et al. 2019), as they are similar in size (148–169 nt) and GC content, while forming structures of similar stability, with predicted free energies of −47.8, −56.9, and −47.5 kcal/mol, respectively (Fig. 1A; Supplemental Fig. S1; Supplemental Table 1). Upon renaturation in the presence of 2.5 to 10% (w/w) of the crowding agent polyethylene glycol (8000 Da), all three riboswitches formed droplets in H10N15M10 buffer (Fig.1B, see Materials and Methods). These observations indicate that non-specific RNA condensation of these riboswitch RNAs may be promoted by high concentration of PEG 8K. At low concentrations of PEG 8K, the Gdn riboswitch formed well-defined condensates most readily, even with only 2.5% PEG 8K (Fig. 1B, image 6). This observation suggests that either the sequence or structure of the RNA may determine its propensity to form condensates in low amounts or even the absence (see below) of crowding agents. It is especially important to investigate no-PEG conditions since PEG is a dehydrating agent and its relevance to biology is uncertain (Buscaglia et al. 2013; Tyrrell et al. 2015).

FIGURE 1.

Macromolecular crowding induces condensate formation of bacterial riboswitches. (A) Secondary structure models of guanine (Gua), guanidine (Gdn), and ykkc_2c riboswitches based on NUPACK (Zadeh et al. 2011). See Supplemental Figure S1 for sequences. The 3′ ends of the RNAs are indicated with green arrows. (B) DIC microscope images of riboswitch RNA condensates in the presence of polyethylene glycol 8K (PEG8K). 10 µM RNA was renatured in the presence of H10N15M10 buffer (see Materials and Methods), and varying amounts of polyethylene glycol (8K) for the indicated riboswitches. Renaturation was carried out by heating the mixture at 90°C for 3 min, 65°C for 1 min, and holding at 37°C until mounted on a glass slide with DIC visualization. (C) Condensates contain RNA and are depleted in PEG. Conditions as per image 8, except CF647-labeled guanidine riboswitch (8% labeled) and FITC-labeled PEG-8K (0.5% labeled) were used in all three images. See Materials and Methods for excitation and emission parameters.

To further understand the composition of the condensates, we used CF-647 fluorescent dye-tagged Gdn RNA and FITC-tagged PEG in the condensation experiments. The resultant droplets were highly enriched in RNA, while PEG was excluded (Fig. 1C, compare panels 2 and 3). These observations confirmed that RNA itself is the main macromolecular component of the condensate.

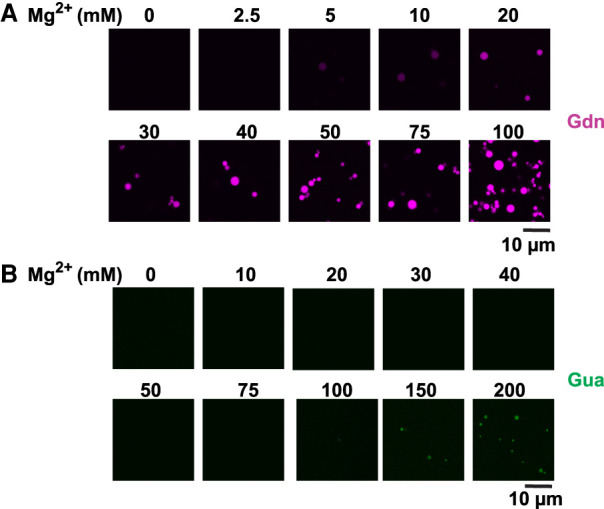

Mg2+ promotes condensation of specific RNAs in the absence of PEG

In an effort to understand how RNA structure, sequence, and environmental factors affect condensation, we eliminated crowding agents in our experiments. Here, we were specifically interested in the roles of Mg2+ in condensate formation, which could be associated with RNA–RNA interactions or specific structures. It has been shown that elevated Mg2+ levels can induce phase separation of homopolymeric RNAs in vitro (Onuchic et al. 2019). To test whether elevated Mg2+ levels can drive RNA condensation in the absence of macromolecular crowding, we focused on the Gua and Gdn RNAs as they showed apparent differences in condensation propensity at low PEG concentrations (Fig. 1B, compare panels 2/3 with 6/7). We titrated Mg2+ in our condensation experiments with CF-647-labeled Gdn and CF488-labeled Gua riboswitch RNAs. Even in the absence of a crowding agent, the Gdn riboswitch formed droplets at concentrations as low as 5 mM Mg2+ (Fig. 2A). Both the amount of RNA inside droplets and size of the condensates increased with increasing concentration of Mg2+ (Fig. 2A). Specifically, when the largest visible condensates were compared between 30 and 100 mM Mg2+, both the average fluorescence intensity and size of the condensates increased approximately 1.3- to 1.5-fold (Supplemental Fig. S2A).

FIGURE 2.

RNA phase transition is dependent on RNA identity and magnesium concentration. (A) 2.5 µM Guanidine riboswitch (CF-647-labeled, ∼13% labeled RNA) was renatured in the presence of 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.0) and the indicated amounts of Mg2+. Contrast of the images was increased to aid in visualization at lower Mg2+ levels. (B) Same as A but with Guanine riboswitch (CF-488-labeled, ∼10% labeled RNA). Note that the CF-647 label is essential to visualization: When 10 µM Gdn RNA was used (Fig. 1B) as opposed to 2.5 µM (A), no condensates were visible in the absence of PEG 8K at the 10 mM Mg2+ with DIC visualization (Fig. 1B, panel 5).

To investigate the potential role for Mg2+ and RNA stoichiometry further, we compared condensation experiments at 2.5 and 10 µM Gdn RNA in 10 and 100 mM Mg2+. At 10 mM Mg2+ we observed condensates for only 2.5 µM RNA; however, at 100 mM Mg2+, both 2.5 µM and 10 µM RNA samples formed condensates (Supplemental Fig. S2B). These results are consistent with Mg2+ shielding charges of anionic backbone of RNA allowing extensive RNA–RNA interactions, and that more Mg2+ is required to allow such RNA–RNA interactions at high concentrations of RNA. Interestingly, when we performed similar Mg2+ titration experiments with 2.5 µM Gua riboswitch, no droplets were observed until 100 mM Mg2+ (Fig. 2B). These data indicate that sequence and structure of the riboswitch RNAs are critical for the formation of condensates at elevated Mg2+ in the absence of crowding agents. Furthermore, these observations are consistent with previous reports on short oligonucleotides where increase in cation concentration was found to shift the equilibria from hairpin to dimers (Nakano et al. 2007).

To further understand the biophysical and biochemical properties of these condensates, we tested whether Na+ ions could substitute for Mg2+ ions. In the absence of Mg2+, no condensates were visible for the Gdn riboswitch at 0.5 or even 1 M NaCl, despite the ionic strength being greater than at 50 mM MgCl2 (Supplemental Fig. S3A), indicating that divalent cations are needed to drive RNA condensation. We then investigated the dynamics of the RNA within droplets by Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP) at 50 mM Mg2+ (Supplemental Fig. S3B). Fluorescence did not recover in the bleached region even after 4 min, indicating that Gdn RNAs inside the droplets at 50 mM Mg2+ are largely immobile. This observation is consistent with previously published reports on phase transition of RNAs containing triplet repeats (Jain and Vale 2017) and may be the result of strong base-pairing between RNAs, although Mg2+-phosphate interactions could also contribute to the lack of diffusion. Finally, Mg•ATP has been shown to completely dissolve proteinaceous condensates even at concentrations as low as 4–8 mM (Patel et al. 2017). We thus, formed Gdn RNA condensates in the presence of various concentrations of Mg•ATP. However, no significant effect of Mg•ATP on RNA droplets was observed even up to 10 mM Mg•ATP (Supplemental Fig. S3C). Together, these observations suggest that biochemical and biophysical properties of condensates formed by riboswitches are distinct from many liquid-like condensates, which are formed by weak multivalent interactions and typically show high diffusion of biomolecules and sensitivity toward hydrotropes and salt (Aumiller et al. 2016; Patel et al. 2017; Onuchic et al. 2019).

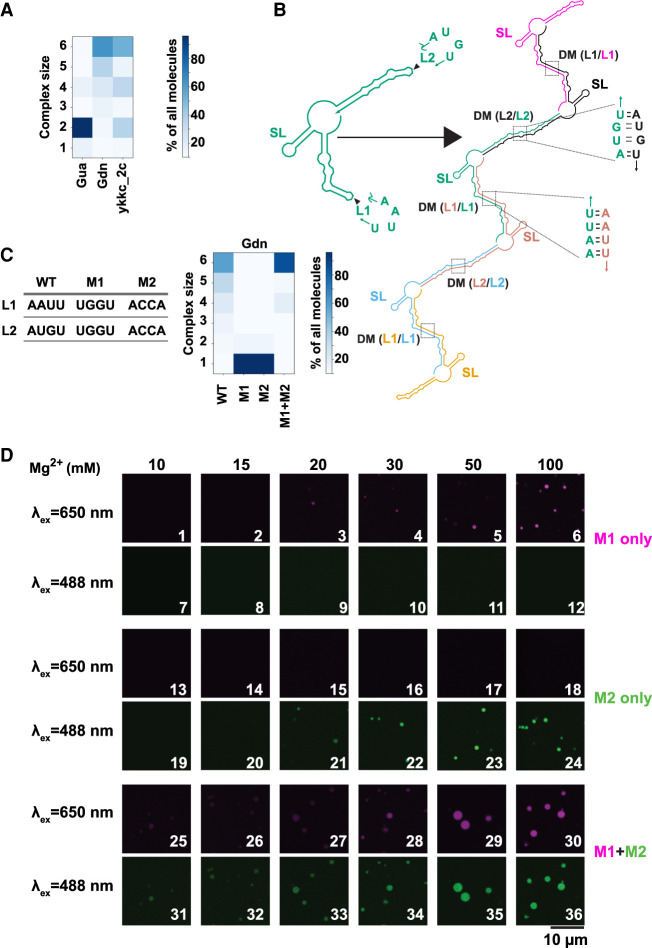

To further understand the contribution of RNA structure toward formation of condensates, we predicted the propensity of multimerization for all three riboswitches using the Nucleic Acid Package (NUPACK) (Zadeh et al. 2011). The Gua riboswitch, which did not form RNA droplets readily in the absence of crowding agents (Fig. 2), was predicted to form primarily dimers and not higher order multimers (Fig. 3A, col 1). Strikingly, the Gdn riboswitch, which demonstrated a high propensity to form RNA condensates (Figs. 1, 2), also had a high predicted propensity for multimerization (Fig. 3A, col 2), consistent with this behavior. These in silico predictions suggest that RNAs predisposed to multimerization may be prone to forming condensates and that intermolecular RNA–RNA interactions are drivers of condensate formation.

FIGURE 3.

Loop–loop interactions mediate assembly of RNA condensates. (A) Propensity for RNA multimerization as predicted by NUPACK for guanine (Gua), guanidine (Gdn), and ykkc_2c nucleotide binding riboswitch (ykkc_2c). (B) NUPACK predicted architecture for multimerization (n = 6 here) of guanidine riboswitch. Self-complementary loops L1 and L2 form trans-strand dimerization motif (DM). Stem–loop structure (SL) is retained as a cis-strand structure within the multimers. Each copy of the transcript is a separate color and labels are color matched. (C) Propensity for RNA multimerization of the guanidine riboswitch as predicted by NUPACK for WT, M1, M2, and M1 + M2 mutants. M1 was CF647 labeled and M2 was CF488 labeled. (D) Guanidine riboswitch mutant RNAs were renatured with indicated amounts of Mg2+ (in the absence of PEG). Samples contained 2.5 µM total RNA, with ∼8% labeled with indicated dyes. For experiments containing both M1 and M2, half amounts of individual RNAs were premixed while keeping the total RNA concentrations identical to experiments containing single RNA only.

Loop-mediated intermolecular RNA interactions drive RNA condensation

To further examine the relationship between multimerization and RNA phase transition, we focused on the Gdn riboswitch, which forms condensates most readily. For this RNA, the structure of the monomer consists of three helical domains, two of which have internal bulges and unpaired tetraloop regions (L1 and L2), while the remaining helix forms an uninterrupted very stable stem–loop structure (SL) (Fig. 3B, left). Upon multimerization, structural features that normally form intramolecularly are predicted to form intermolecularly, as is typical in most RNAs (Proctor et al. 2003). Interestingly, the L1 and L2 loop sequences are palindromic and so are predicted to become part of the dimerization helices as the dimerization motifs DM(L1/L1) and DM(L2/L2) (Fig. 3B, right). Notably, the helices containing L1 and L2 are considerably less stable than the SL region, approximately two- to fourfold in terms of free energy change per nt (Supplemental Fig. S4A). This suggests that during renaturation the SL domain is likely to remain folded or to rapidly reform localized cis base-pairs, while the L1 and L2 regions are likely to re-pair during this step. To test this model, we generated two variants of the Gdn riboswitch, wherein the L1 and L2 sequences were changed to UGGU (M1) and ACCA (M2) (Fig. 3C, left). (See also Supplemental Text for effects of mutants on structure itself and Supplemental Fig. S5.) In silico, both M1 and M2 mutant RNAs are predicted to not multimerize when they are present by themselves (Fig. 3C, grid, cols 2 and 3), but to form higher-order multimers when both the mutant RNAs are present, similar to WT (Fig. 3C, grid, compare cols 1 and 4). Although NUPACK will predict up to 10 monomers, we chose 6 for ease of inspection and clarity, as no new modes of interaction were observed for the WT Gdn riboswitch when 10 monomer complexes were tested (Supplemental Fig. S4B).

Next, we tested these predictions experimentally. When M1 (CF-647 labeled) and M2 (CF-488 labeled) were present by themselves, no condensates were visible until 20 mM Mg2+ (Fig. 3D, panels 3 and 21), and even here RNA droplets were sparse compared to the WT guanidine riboswitch (compare to Fig. 2A). These data suggest that mutations of the palindromic sequences indeed have a deleterious effect on RNA condensation. Strikingly, when the mutants were mixed together, the droplets are visible even at 10 mM Mg2+ and become larger with increasing Mg2+ (Fig. 3D, rows 5 and 6), similar to WT guanidine riboswitch (Fig. 2A). Combined, these results suggest that loop–loop interactions play key roles in driving RNA multimerization and condensation. Our data thus indicate that RNA sequence and structures can be rationally designed to tune and control the propensity of RNAs to form condensates.

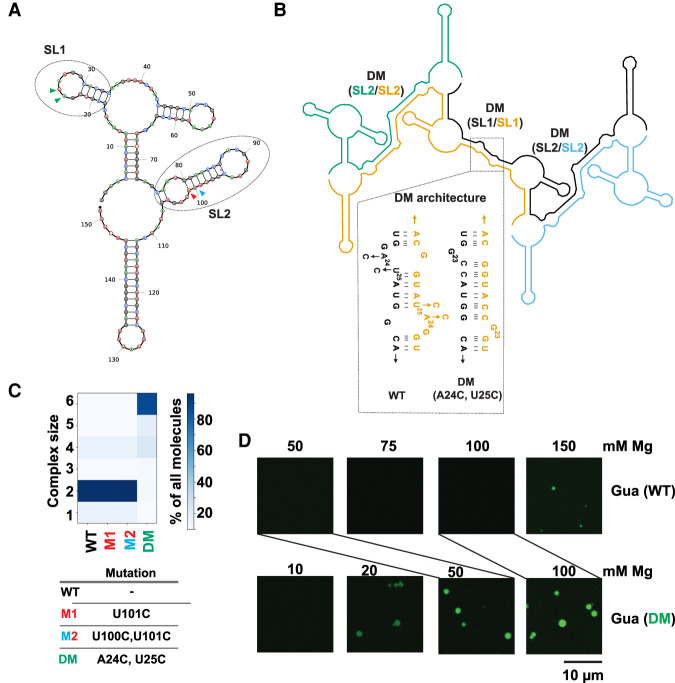

To understand whether modulation of RNA condensation by RNA structure can be generalized, we turned our attention from the Gdn riboswitch to the Gua riboswitch (Fig. 4), which does not readily form condensates, even at 100 mM Mg2+ (Fig. 2B). In silico predictions suggested that SL1 and SL2 domains of monomeric Gua riboswitch (Fig. 4A) form helical structures in trans DM(SL1/SL1) and DM(SL2/SL2), which contain bulges (Fig. 4B). We reasoned that mutating nucleotides to strengthen the DM interactions might promote RNA multimerization. We began by considering strengthening of base-pairing in SL2. Specifically, we looked at the two G•U wobbles at the base of SL2 involving U100 and U101. Strengthening the SL2 dimerization stem from two G•U wobbles to two GC base pairs in U101C and U100C:U101C as “M1” and “M2” in Figure 4A were predicted by NUPACK to not have any significant impact on RNA multimerization (Fig. 4C, compare WT to M1 and M2). These mutations strengthen base-pairing equally in the monomeric and dimeric states, revealing that a design principle for driving LLPS is to strengthen selectively in the multimeric state.

FIGURE 4.

Stabilization of RNA–RNA interactions favors LLPS of the Guanine riboswitch. (A) Predicted secondary structure of the Guanine riboswitch monomer. Regions containing unpaired nucleotides that become part of base-paired structures post-multimerization are indicated as SL1 and SL2 and encompassed with ovals. Colored arrows refer to positions of mutants below. (B) NUPACK model for multimerization of the Guanine riboswitch (n = 4 here). Self-complementary SL1 and SL2 form extended dimer helices (DM) in trans. The SL1 region was stabilized by the A24C:U25C double mutant designed to stabilize DM (SL1/SL1) region (shown in dotted region). Each copy of the transcript is a separate color and labels are color-matched. (C) The SL2 region was stabilized by the M1 and M2 changes (SL2/SL2). See panel A for color-matching arrows. (D). Microscopy images comparing formation of condensates by the WT (10% labeled RNA) and A24C:U25C double mutant guanine (15% labeled RNA) riboswitch. Samples contained 2.5 µM RNA in 10 mM HEPES and 15 mM NaCl (pH 7.0) with indicated concentrations of Mg2+. Lines directly compare the 50 mM Mg2+ concentrations for WT and DM, as well as the 100 mM Mg2+ concentrations.

Because SL2 mutants were not predicted to affect multimerization, we turned our attention to SL1. Specifically, we considered a A24C:U25C double mutant, which was predicted to replace a single G•U wobble in the multimer structure with two GC base pairs (Fig. 4B, inset) and to increase the propensity of the guanine riboswitch to multimerize (Fig. 4C, DM). The reason is that these mutations preferentially strengthen the dimer/multimeric state, much like M1 + M2 in the guanidine riboswitch (Fig. 3C,D). To test these in silico predictions, we compared the experimental condensation data of the A24C:U25C double mutant (Gua DM) to the WT (Fig. 4D). While no condensates were observed for the WT Gua riboswitch until 150 mM Mg2+ (Fig. 4D, top row), robust condensates formed in the A24C:U25C double mutant even at 20 mM Mg2+ (Fig. 4D, bottom row). This is similar to the Mg2+ response of the WT and M1+M2 Gdn riboswitches (Figs. 2, 3), although in the case of the Gua riboswitch, the DM mutant turned on condensation, while in the case of the Gdn riboswitch it only restored it. Overall, these data indicate that structure-guided modulation of trans-RNA–RNA interactions can be used to control the condensation behavior of RNAs.

RNA structure probing corroborates in silico predictions

To test our multimerization model, we performed in-line probing (ILP) experiments on the 5′-labeled Gua DM riboswitch inside of condensates (Supplemental Fig. S6). We chose this RNA because in silico calculations predict a 15 nt base pair upon multimerization (Fig. 4A), which is double the number for the Gdn riboswitch. The ILP approach provides nucleotide-level resolution of RNA structure, with base-catalyzed hydrolysis of the RNA backbone occurring preferentially in flexible, single-stranded regions of the RNA (Regulski and Breaker 2008; Cakmak et al. 2020; Poudyal et al. 2021). Because the multimerization model predicts the single-stranded loops of SL1 and SL2 in the monomer conformation (Fig. 4A) to be base-paired in the multimer conformation (Fig. 4B), nucleotides in this loop region were monitored by in-line probing upon droplet formation.

We found that overall the Gua DM RNA exhibited similar ILP patterns in the presence and absence of condensates (Supplemental Fig. S6, compare “−Condensate” and “+Condensate” lanes), supporting a model in which the Gua DM RNA adopts a similar core secondary structure inside and outside of condensates. Moreover, the ILP reactivity data were consistent with the NUPACK-predicted secondary structures for −Condensate and +Condensate RNA populations (Supplemental Fig. S7, red maps to single-stranded regions).

Evidence to support multimerization came from the SL1/SL1 and SL2/SL2 regions. The SL1/SL1 region showed a striking change in ILP patterns (Fig. 4B; Supplemental Fig. 6, gray). Upon multimerization, G23 has drastically reduced ILP reactivity while G22 has slightly enhanced reactivity (Supplemental Fig. S6). This supports a very slight change of a migrating bulge, with G23 pairing and G22 unpairing upon multimerization as shown in Supplemental Figure S7C.

Our ILP data also captured predicted SL2/SL2 interactions. For example, in silico models predicted nucleotides C87 to G92 to be base-paired exclusively in the multimeric state (Supplemental Figs. S6, S7). Indeed, we see experimentally that ILP signals from this set of nucleotides are lower in the condensate fraction (Supplemental Fig. S6). Overall, the ILP data directly support the importance of loop–loop interactions in driving RNA condensation and indicate that NUPACK calculations are largely predictive of phase separation.

Engineering of new RNA-mediated condensate functions

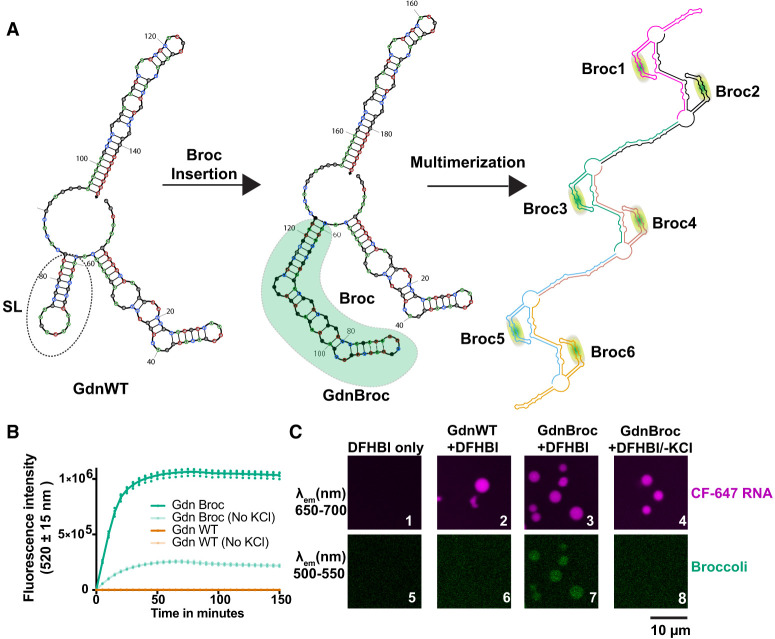

We next sought to explore whether novel properties could be engineered into RNA condensates, as guided by in silico structural predictions. The Gdn riboswitch was used as the model system. In this RNA, the SL domain of the monomer was the only structural element predicted to retain cis-interactions during multimerization (Fig. 3B). We thus investigated whether this domain can be swapped with other functional RNA modules (Fig. 5A). A hybrid RNA termed “GdnBroc” was designed, wherein we embedded the fluorescence-activating broccoli aptamer at SL domain (Fig. 5A, middle) (Filonov et al. 2014). This design allows native RNA folding to be readily determined owing to the fluorescence of the DFHBI ligand in the presence of its broccoli aptamer. On the basis of NUPACK, the resulting RNA was predicted to multimerize and to adopt the same framework of RNA–RNA interactions as the wild-type Gdn riboswitch (compare Fig. 5A, right to Fig. 3B, right).

FIGURE 5.

Structure-guided engineering toward condensates with novel functions. (A, left) Structure of the guanidine riboswitch monomer and (middle) with broccoli aptamer insert (green). (Right) Predicted multimerization architecture for the broccoli insert-containing guanidine riboswitch shown out to a hexamer. Each copy of the transcript is a separate color. (B) Fluorescence intensity at 520 ± 15 nm of in vitro transcription reactions in the presence of 10 µM DFHBI dye and 10 mM KCl for both WT (gold) and the broccoli insert-containing (green) guanidine riboswitch. Note that graphs for Gdn WT (±KCl) are indistinguishable. (C) Microscopy images showing fluorescence from either CF-647 labeled RNA (∼15% labeled RNA) (top row) or from the broccoli aptamer (bottom row). All experiments contained 10 mM KCl to promote Broccoli fluorescence except panels 4 and 8.

To test whether the engrafted aptamer remains functional, we performed cotranscriptional fluorescence measurements for GdnBroc. The fluorescence from DFHBI increased with time of transcription (Fig. 5B, dark green), suggesting that the GdnBroc RNA contains a natively folded broccoli aptamer unit. Fluorescence was enhanced by KCl, as predicted for this G-quadruplex containing aptamer (Shelke et al. 2018), and missing in WT controls without broccoli (Fig. 5B). To understand whether GdnBroc could form condensates and remain functional while in droplets, we labeled the GdnBroc RNA on the 3′-end with CF 647 dye, which we then used to form RNA condensates. The 3′-end labeling with CF647 dye enabled simultaneous tracking of the total RNA (Ex. 633 nm, Em. 650 nm) (Fig. 5C, top row) and the functional broccoli (Ex. 488, Em 510) (Fig. 5C, bottom row). As with the Gdn riboswitch (Fig. 5C, panel 2), GdnBroc formed condensates (Fig. 5C, panel 3). Strikingly, when DFHBI was added to the GdnBroc condensates, fluorescence was observed in the green channel (Fig. 5C, panel 7), indicating that the broccoli aptamer remains functional and is natively folded within the condensates. Importantly, when the Gdn riboswitch without engineered broccoli but with DFHBI was tested, no fluorescence was observed in the green channel (Fig. 5C, panel 6) even though RNA was present (panel 2), suggesting that fluorescence from broccoli is not due to non-specific interactions between the DFHBI dye and RNA in the condensates. Additionally, the broccoli fluorescence was sensitive to K+ (Fig. 5C, panels 4 and 8), strongly supporting that the observed fluorescence is indeed from the engrafted broccoli aptamer. Overall, these data indicate that structure-guided engineering of RNA domains can be used to introduce novel functions within condensates, while also showing that some portions of an RNA can remain natively folded even when other parts dimerize within condensates.

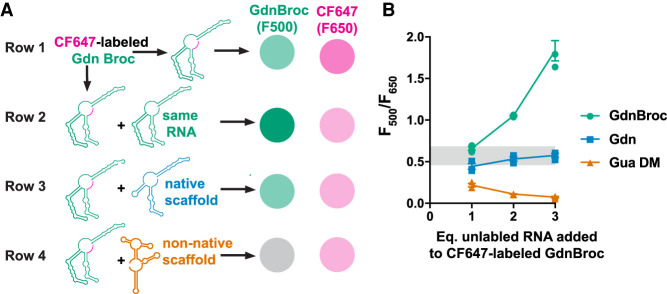

Specificity of RNA interactions in condensates

Intracellular condensates such as stress granules and P-granules have been shown to contain a wide variety of RNAs (Khong et al. 2017; Lee et al. 2020). We sought to understand whether different RNAs interact non-specifically when renatured together, as non-specific RNA–RNA interactions can lead to misfolding of native RNA structures. As GdnBroc RNA contains a functional domain, it can report on native RNA folding via fluorescence within the condensates. Occurrence of non-native RNA–RNA interactions, which can lead to misfolding of RNA structures, can thus be observed as a decrease in broccoli fluorescence in the condensates.

We first formed droplets by mixing 3′-CF647-labeled-GdnBroc (shown in Fig. 6A row 1, Supplemental Fig. S8A) with increasing concentration of unlabeled GdnBroc (Fig. 6A row 2, Supplemental Fig. S8B). In these experiments, the droplets grew brighter for broccoli fluorescence (λem = 510 nm), dimmer for CF647 fluorescence (λem = 650 nm) owing to dilution, and also larger as expected due to increased concentration of condensate forming RNA (Fig. 6B green, Supplemental Fig. S8B). We then performed a similar experiment but instead of adding unlabeled-GdnBroc, we added a WT Gdn riboswitch, which has the same scaffold as the GdnBroc but lacks the functional broccoli unit (Fig. 6A, row 3, Supplemental Fig. S8C). Addition of Gdn resulted in condensates with a slight decrease in broccoli and CF647 fluorescence compared to no added Gdn owing to dilution, as expected. The droplets remained fluorescent up to threefold excess Gdn WT RNA and the ratio of F500 and F650 did not change appreciably with excess Gdn (Fig. 6B blue, Supplemental Fig. S8C). Since GdnBroc is built on the scaffold of Gdn, these data are consistent with correct folding of the broccoli aptamer even in the presence of WT Gdn, which is also predicted by heterodimer foldings in silico (Supplemental Fig. S9A, green is natively folded).

FIGURE 6.

Presence of noncognate RNAs lead to misfolded RNAs in condensates. (A) Expected results. Monitoring nonspecific RNA–RNA interactions through broccoli fluorescence. Row 1: Condensates formed with 3′-CF 647-Gdn Broc RNA are expected to fluoresce both in the 500–550 nm range (green) and the 650–700 nm (magenta). Row 2: Addition of unlabeled GdnBroc RNA (“same RNA”) is expected to dilute the fluorescence from the 3′-CF 647-labeled Gdn Broc RNA while increasing the broccoli fluorescence. Row 3: Addition of unlabeled WT guanidine riboswitch (“native scaffold”) is expected to dilute the fluorescence from both the 3′-CF 647-labeled Gdn Broc RNA and the broccoli element. Row 4: Addition of unlabeled double mutant Gua riboswitch (“non-native scaffold”) is expected to dilute the fluorescence from the 3′-CF 647-labeled Gdn Broc RNA but also disrupt broccoli fluorescence. (B) Actual results. Relative fluorescence of broccoli to CF-647 with condensates containing different RNAs. Range of relative fluorescence values of Gdnbroc without any additional RNAs is marked in gray rectangle. Symbols are color coded with added RNAs in rows 2–4 of panel A.

Finally, we added a different RNA altogether, unlabeled Gua DM RNA. This mixture showed fluorescence from the CF647 3′-end-labeled-GdnBroc RNA; but very little fluorescence from the broccoli units (Fig. 6B orange, Supplemental Fig. S8D). These data suggest that when different RNAs are present in the condensate, non-specific RNA–RNA interactions can occur leading to colocalization and misfolding of the RNAs. The unfolded broccoli in the presence of non-native “scaffold” is also consistent with in silico heterodimer predictions (Supplemental Fig. S9B, green is misfolded).

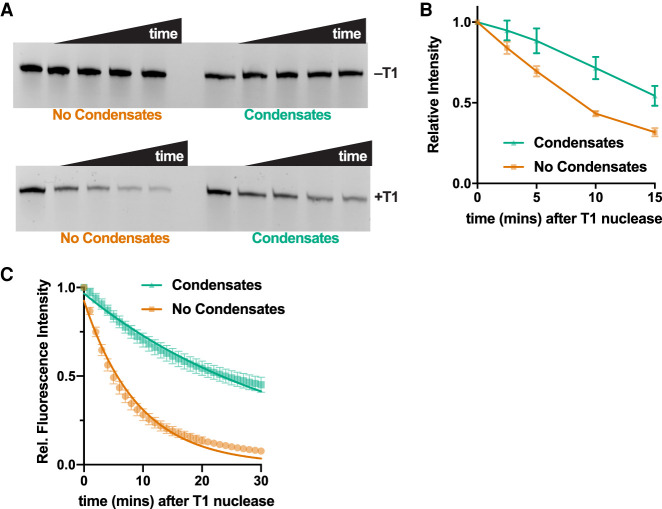

Condensates partially protect RNA from nuclease degradation

Condensates have been hypothesized to play important roles as bioreactors and containers for biomolecules such as RNAs and proteins, especially in origins of life scenarios (Jia et al. 2014; Drobot et al. 2018; Poudyal et al. 2018). One important characteristic of such compartments might be protection of the encapsulated contents from degradation. To test whether RNA-based condensates could have such properties, we probed the sensitivity of RNA in condensates toward a ribonuclease. We incubated 3′-CF488 labeled Gdn WT RNA in condensates or in solution with G-specific RNase T1. In the absence of the nuclease, the amount of RNA remained constant over 15 min for both solutions and condensates, as expected (Fig. 7A top). However, in the presence of T1 nuclease, the RNA degraded more rapidly in the absence of droplets as compared to condensates, suggesting that condensates partially protect RNA from degradation (Fig. 7A bottom and Fig. 7B).

FIGURE 7.

RNA condensates protect RNA from RNase T1-mediated degradation. (A, top) Denaturing polyacrylamide gel image showing full-length Gdn RNA (3′-CF488-labeled) over time in solution or as condensates without (top row) and with (bottom row) 0.3 U RNase T1. Time points are 0, 2.5, 5, 10, and 15 min. (B) Quantification of data in panel A. Error bars represent standard error n = 5. (C) Fluorescence of the broccoli aptamer as a function of time after addition of RNase T1 nuclease to Gdn Broc RNA. The RNA was either present in solution (orange) or as condensates (green). Error bars represent standard error (n = 4). Fluorescence values were normalized to intensities at 0 min. Fitting the data to first order exponential decay (Equation 1, see Materials and Methods) provide observed rate constants of 0.03 and 0.11 min−1 for condensate and no condensate samples, respectively.

To test this hypothesis further, we formed condensates from Gdn Broc RNA and challenged them with RNase T1. We used real-time fluorescence measurements from the broccoli aptamer to provide a direct quantitative assessment of intact RNA. Even after 30 min, 50% of the RNA remained as fully functional broccoli aptamer when present as condensates compared to <10% in the absence of condensates (Fig. 7C). The observed rate constant for signal decay from the broccoli aptamer was almost fourfold faster in the absence of condensates (0.11 vs. 0.03 min−1). These data demonstrate that having RNAs encapsulated as condensates can protect the RNA from protein nucleases. While the exact mechanism of protection remains unclear, it could involve sequestration of unpaired Gs upon multimerization, making them inaccessible for the RNase T1.

DISCUSSION

Overall, our study provides a mechanistic framework for formation of RNA droplets through base-pairing-mediated RNA multimerization. Intermolecular RNA–RNA interactions have been hypothesized to play important roles in both the assembly and dynamics of intracellular RNP condensates. Here we have demonstrated the critical contributions of specific RNA sequence and structural properties in assembly of RNA-based condensates, as distinct from the more general contributions of environmental factors such as crowding and ionic strength. Our data show that specific RNA structures can promote condensation of RNAs even without the need for polyamines and crowding agents, which have been shown to facilitate assembly of condensates of biological and synthetic RNA molecules (Jain and Vale 2017; Van Treeck et al. 2018; Zhang et al. 2019).

We showed that without any macromolecular crowding, RNA multimerization is enhanced by RNA–RNA interactions through base-pairing and divalent cations. Others have reported that high concentrations of Mg2+ and Ca2+ ions can drive formation of homopolymeric RNA coacervates such as polyU (Onuchic et al. 2019). However, in such RNAs, which have minimal hydrogen bonding, condensation is driven primarily by non-specific RNA interactions (Thrierr et al. 1971; Young and Kallenbach 1978). In contrast, our study used highly structured biological RNAs to address contributions from RNA sequence and structure toward formation of RNA condensates. As RNA multimers could lead to formation of large networks of RNA condensates, we used in silico predictions to estimate whether certain RNAs are prone to forming multimers. These predictions suggested that for RNAs that form condensates, the overall structure of the RNA may remain largely unchanged; however, many monomeric cis helices were predicted to be traded for trans helices, thereby allowing formation of the extended networks of RNA molecules that can generate condensates. We showed specifically that palindromic sequences in the loop regions are critical in determining the propensity of a single RNA to form higher order multimers ultimately maturing into condensates; moreover, complementary nonpalindromic loop sequences can also interact in trans to yield similar behavior, as illustrated in Figure 3 M1 + M2. This is likely because no base pairs have to be broken for loops to interact. These observations are in-line with biological instances where palindromic sequences nucleate critical RNA–RNA interactions such as in the case of HIV, where the genome dimerization is initiated by the palindromic dimerization initiation sequence (DIS) (Lu et al. 2011). Furthermore, large unpaired loops in artificial RNA aptamers derived from SELEX have also been shown to play critical role in the formation of hydrogels (Huang et al. 2017).

One feature of RNA-based condensates is the potential to control their internal network of RNA–RNA interactions. Complex coacervates and other RNP condensates formed by charge-charge interactions typically interact non-specifically. As such, controlling encapsulation of RNAs with unique identity, structure, and function can be challenging (Boeynaems et al. 2019; Poudyal et al. 2019b). In contrast, we demonstrated that mutations that selectively stabilize the dimeric states of RNAs while not affecting the monomeric states can promote formation of functional RNA condensates. Based on this idea, we demonstrated that structure-guided engineering allows complete turn on or turn off of RNA condensation. Furthermore, we provided evidence that specific RNA structures that do not engage in trans RNA–RNA interactions can be grafted with functional RNA domains to generate RNA condensates with novel properties.

Although beyond the scope of this study, engineering of condensates with functional RNAs presents opportunities to recruit and enrich specific proteins or other small metabolites via RNA aptamers into the condensates, providing a compartment for biomolecular reactions. Native folding of aptamers might be retained in complex mixtures by the order in which the RNAs condense and by the very nature of the partners. Indeed, we and others have shown that non-specific enrichment of enzymes and substrates by complex coacervates can lead to activation of enzymes (Poudyal et al. 2019a). RNA-based condensates may also be useful in synthetic biological applications as bioreactors which can activate chemical reactions. RNA condensates could potentially be used in a similar fashion to increase local concentration of specific oligonucleotides by base-pairing interactions. Such increase of local concentration may be utilized to activate specific chemical reactions (Gartner et al. 2004).

We found that condensates protected RNAs from a ribonuclease. This observation indicates that intracellular condensates may also act as “containers” for RNAs and proteins until they are utilized in their specific processes (Riback et al. 2017). Such a mechanism would prevent RNAs from being degraded by cellular nucleases when not being actively translated or performing native functions (e.g., lncRNAs). mRNA-based nanoparticles, which are also highly packed, have been shown to have increased resistance toward serum nucleases, consistent with our observations of RNA condensates resisting T1 RNase (Kim et al. 2015). However, because biomolecular partitioning within condensates is affected by the composition of proteins and RNAs that form the given condensate, other condensate systems may have opposite effects, wherein recruitment of proteins could promote RNA degradation.

Our results also have implications in origins of life scenarios, where RNA is hypothesized to have played both informational and catalytic roles in the RNA World. First, condensates may have had similar protecting effects against other nucleases in the primordial world. Additionally, as the mechanism of RNA condensate assembly involves base-pairing of the unpaired nucleotides in loop regions, this protects the RNA from hydrolysis, as 2′OH in base-paired nucleotides sample the “in-line” conformation less frequently compared to an unpaired nucleotide (Regulski and Breaker 2008). Although we used thermal denaturation to drive assembly of RNAs, cellular helicases and other intracellular condensates (Nott et al. 2016) may unfold RNA helices allowing for trans RNA–RNA interactions; alternatively, cotranscriptional folding can lead to access of base pairs, which can drive formation of RNA multimers and RNA condensates. Overall, our study suggests that propensity of an RNA to undergo LLPS is “coded” in both its sequence and structure, and as such provides a foundation for using model RNA-based condensates such as those described herein to study biological condensation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

All chemicals were purchased from Sigma unless otherwise noted. DNA templates to make riboswitch RNA transcripts were purchased from IDT. Sequences of riboswitches and primers used for PCR amplification are provided in the Supplemental Information. Ribonuclease T1 was purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific, and DFHBI dye was purchased from Tocris Biosciences.

DNA template generation and RNA transcription

Ten nanograms of DNA template (top strand) was PCR amplified using the forward and the reverse primer. All DNA templates gave single-band RNA transcripts on an 8% denaturating polyacrylamide gel. RNA bands were excised following UV-shadowing, and ethanol precipitated as described (Poudyal et al. 2021). RNAs were stored in RNase-free water until use in 10 to 20 µL aliquots at −20°C (∼100 µM).

3′-end labeling of RNA

RNAs were fluorescently labeled on the 3′ end using sodium periodate-mediated oxidation followed by reductive amination using a hydrazide-functionalized dye (Poudyal et al. 2021). In brief, 1 nanomole of RNA was resuspended in a solution containing 10 mM sodium periodate (freshly prepared) and 100 mM sodium acetate (pH 5.2). Samples were incubated at room temperature for 1.5 h. They were then precipitated by adding 300 µL of 300 mM sodium acetate, followed by 800 µL of 100% EtOH. Samples were then kept in dry ice for 2 h, followed by centrifugation at 4°C at 14,000g for 30 min. Supernatant was decanted and pellet was dried. To initiate the coupling reaction, the pellets were resuspended in 2 µL of 10 mM hydrazide dye (CF488 or CF647, Sigma) derivative fluorophore (dissolved in anhydrous DMSO), 2 µL of 0.5 M sodium acetate (pH 5.2), and 16 µL of water (in the given order) and left in the dark at 4°C for overnight. The RNAs were ethanol precipitated as described above to remove excess unincorporated dye, followed by filtration using a 10,000 Da (Amicon) molecular weight cut-off centrifugal filter unit. Labeling efficiencies were calculated by ratios of RNA concentrations obtained by using absorbance values at 260 and 490 nm (for CF488, Ex. Coeff = 70,000 M−1cm−1) or 650 nm (for CF650, Ex. Coeff = 240,000 M−1cm−1). Labeled RNAs were added to the sample at the indicated final concentrations during condensation experiments.

Structure prediction

All RNA structure predictions were performed in NUPACK (http://www.nupack.org/) using free-energy parameters from Mathews et al. (1999). For RNA multimerization predictions, maximum complex size was typically capped at 6, and RNA concentration was set at 10 µM. All structural predictions were carried out at 37°C and 1 M NaCl.

RNA condensation experiments

Indicated concentration of RNA (2.5–10 µM) was resuspended in 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.0) and 15 mM NaCl. Magnesium concentration was varied as indicated. As an example of our shorthand notation, H10M10N15 buffer contains 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.0), 10 mM MgCl2, and15 mM NaCl. Experiments shown in Figure 1 also contained polyethylene glycol as specified. Samples (20 µL) were first heated at 90°C for 3 min after which time they were moved to 65°C and incubated for 1 min. Samples were finally moved to 37°C and incubated for 1 min. Following the incubation at 37°C, samples were mixed using a pipette, and 10 µL was added on a glass coverslip and viewed on Leica TCS SP5 laser scanning confocal inverted microscope (LSCM) with a ×63 objective lens. This procedure is a variation from a previously reported protocol (Jain and Vale 2017). The 488 (broccoli or CF488 dye) and 633 nm lasers (CF647 dye) were used for excitation, and emission spectra were collected from 500–510 nm (broccoli or CF488 dye) and 650–700 nm (CF647 dye). Images were acquired using Leica LAS AF software. For experiments containing the broccoli aptamer, the buffer contained 10 mM KCl to promote formation of the G-quadruplex in the aptamer unless otherwise noted (Fernandez-Millan et al. 2017).

In-line probing (ILP) analysis of Gua DM RNA

ILP was performed in triplicate according to standard protocols for ILP (Regulski and Breaker 2008; Poudyal et al. 2021) with some key modifications to address the propensity of the RNA to form extensive trans interactions. Briefly, the RNA was 5′-end labeled using [γ32-P] ATP according to previously published methods. Then, 70,000 cpm (<3 nM) radiolabeled RNA was diluted into 8 µL of water or 5 µM unlabeled RNA in water for the condensate-minus and condensate-plus condition, respectively. The RNA samples were heated to 90°C in the block of a PCR thermocycler. After 1 min, 2 µL of 5×ILP buffer was added for a final buffer concentration of 10 mM Tris, 30 mM MgCl2 15 mM NaCl, 0.001% sodium dodecyl sulfate, pH 8.0. Heat denaturation at 80°C instead of 90°C was chosen to minimize the RNA degradation at 30 Mg2+ concentration. Tubes were visibly turbid after the denaturation step, confirming formation of RNA condensates. Reactions were incubated for 18 h at 37°C and stopped with 30 µL (3×) of formamide loading dye, composed of 50 mM EDTA (pH 8.0) in 90% aqueous formamide, with trace xylene cyanol and bromophenol blue. (High concentration of formamide and excess EDTA are required to prevent smearing.) The NR samples were identical to condensate minus samples but stopped with formamide loading dye immediately after the renaturation step. Ladders were prepared under denaturing conditions as previously described (Poudyal et al. 2021) followed by fractionation on a 10% denaturing gel. For data analysis, the raw gel image was quantified with SAFA (Das et al. 2005) to produce ILP reactivities for each nucleotide. The ILP reactivities for each nucleotide were averaged over triplicate experiments and mapped to secondary structures using R2easyR (http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4683742) and R2R (Weinberg and Breaker 2011).

Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP)

The Gdn RNA condensates were prepared as described for previous experiments. An approximately 1 µM diameter was chosen as the region of interest (ROI) for photobleaching. Laser power was set at 100% with 458, 476, 488, 514, 543, and 633 nm lasers all on at the same time for bleaching (Aumiller et al. 2016). Images were then collected every 10 sec using the 633 nm laser for excitation and 650–700 nm emission window. Since no significant recovery of fluorescence was observed, FRAP data were not further analyzed.

T1 nuclease experiments

The guanidine riboswitch at 2.5 µM (CF 488-labeled) was resuspended in 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.0), 15 mM NaCl, and 50 mM MgCl2. For no condensate samples, the indicated amount of RNase T1 was added and samples were incubated from 2.5 to 15 min at room temperature. Reactions were stopped by adding two volumes of stopping solution (50% formamide, 50 mM EDTA and 0.1% SDS) and heating at 90°C for 30 sec. For condensate samples, RNAs were renatured by heating at 90°C for 3 min after which time they were moved to 65°C and incubated for 1 min. Samples were finally moved to 37°C and incubated for 1 min prior to addition of RNase T1 2.5 to 15 min. Stopped reactions were separated on a 10% denaturing polyacrylamide gel (8M urea). The gel was visualized in the gel documentation instrument (BioRad) using UV-transillumination. For experiments with GdnBroc RNA, we collected fluorescence intensity from Broccoli RNA over time (520 ± 15 nm on Applied Biosystems StepOne Plus qRT-PCR instrument). Experiments were set up as described for guanidine riboswitch RNA, with the following differences. For experiments with GdnBroc RNA, the buffer was supplemented with 10 mM KCl and 10 µM DFHBI, which was added after the renaturation. Using a multichannel pipette, RNAs (±condensates) were added to a 96-well plate containing the RNase T1. Fluorescence measurements where then taken immediately following the mixing on Applied Biosystems qPCR instrument. Pseudofirst order rate constants were obtained by fitting the florescence versus time data to the following equation.

| (1) |

where f(t) is the fluorescence intensity at indicated time t, and k is the observed rate constant. The equation provides acceptable fits for the purpose of comparing relative rates of RNA degradation.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Supplemental material is available for this article.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NASA grant 80NSSC17K0034 to P.C.B. and C.D.K., Maximizing Investigators’ Research Award (MIRA) grant 5R35GM127064 to P.C.B., and Simons Foundation grant 290363 to R.R.P.

Footnotes

Article is online at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.078875.121.

REFERENCES

- Alberti S. 2017. Phase separation in biology. Curr Biol 27: R1097–R1102. 10.1016/j.cub.2017.08.069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aumiller WMJ, Cakmak FP, Davis BW, Keating CD. 2016. RNA-based coacervates as a model for membraneless organelles: formation, properties, and interfacial liposome assembly. Langmuir 32: 10042–10053. 10.1021/acs.langmuir.6b02499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeynaems S, Holehouse AS, Weinhardt V, Kovacs D, Van Lindt J, Larabell C, Van Den Bosch L, Das R, Tompa PS, Pappu RV, et al. 2019. Spontaneous driving forces give rise to protein-RNA condensates with coexisting phases and complex material properties. Proc Natl Acad Sci 116: 7889–7898. 10.1073/pnas.1821038116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brangwynne CP, Eckmann CR, Courson DS, Rybarska A, Hoege C, Gharakhani J, Julicher F, Hyman AA. 2009. Germline P-granules are liquid droplets that localize by controlled dissolution/condensation. Science 324: 1729–1732. 10.1126/science.1172046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buscaglia R, Miller MC, Dean WL, Gray RD, Lane AN, Trent JO, Chaires JB. 2013. Polyethylene glycol binding alters human telomere G-quadruplex structure by conformational selection. Nucleic Acids Res 41: 7934–7946. 10.1093/nar/gkt440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cakmak FP, Choi S, Meyer MO, Bevilacqua PC, Keating CD. 2020. Prebiotically-relevant low polyion multivalency can improve functionality of membraneless compartments. Nat Commun 11: 5949. 10.1038/s41467-020-19775-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das R, Laederach A, Pearlman SM, Herschlag D, Altman RB. 2005. SAFA: semi-automated footprinting analysis software for high-throughput quantification of nucleic acid footprinting experiments. RNA 11: 344–354. 10.1261/rna.7214405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drobot B, Iglesias-Artola JM, Le Vay K, Mayr V, Kar M, Kreysing M, Mutschler H, Tang TD. 2018. Compartmentalised RNA catalysis in membrane-free coacervate protocells. Nat Commun 9: 3643. 10.1038/s41467-018-06072-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Millan P, Autour A, Ennifar E, Westhof E, Ryckelynck M. 2017. Crystal structure and fluorescence properties of the iSpinach aptamer in complex with DFHBI. RNA 23: 1788–1795. 10.1261/rna.063008.117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filonov GS, Moon JD, Svensen N, Jaffrey SR. 2014. Broccoli: rapid selection of an RNA mimic of green fluorescent protein by fluorescence-based selection and directed evolution. J Am Chem Soc 136: 16299–16308. 10.1021/ja508478x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankel EA, Bevilacqua PC, Keating CD. 2016. Polyamine/nucleotide coacervates provide strong compartmentalization of Mg2+, nucleotides, and RNA. Langmuir 32: 2041–2049. 10.1021/acs.langmuir.5b04462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gartner ZJ, Tse BN, Grubina R, Doyon JB, Snyder TM, Liu DR. 2004. DNA-templated organic synthesis and selection of a library of macrocycles. Science 305: 1601–1605. 10.1126/science.1102629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes E, Shorter J. 2019. The molecular language of membraneless organelles. J Biol Chem 294: 7115–7127. 10.1074/jbc.TM118.001192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z, Kangovi GN, Wen W, Lee S, Niu L. 2017. An RNA aptamer capable of forming a hydrogel by self-assembly. Biomacromolecules 18: 2056–2063. 10.1021/acs.biomac.7b00314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain A, Vale RD. 2017. RNA phase transitions in repeat expansion disorders. Nature 546: 243–247. 10.1038/nature22386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon BJ, Nguyen DT, Saleh OA. 2020. Sequence-controlled adhesion and microemulsification in a two-phase system of DNA liquid droplets. J Phys Chem B 124: 8888–8895. 10.1021/acs.jpcb.0c06911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia TZ, Hentrich C, Szostak JW. 2014. Rapid RNA exchange in aqueous two-phase system and coacervate droplets. Orig Life Evol Biosph 44: 1–12. 10.1007/s11084-014-9355-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khong A, Matheny T, Jain S, Mitchell SF, Wheeler JR, Parker R. 2017. The stress granule transcriptome reveals principles of mRNA accumulation in stress granules. Mol Cell 68: 808–820 e805. 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.10.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Park Y, Lee JB. 2015. Self-assembled messenger RNA nanoparticles (mRNA-nps) for efficient gene expression. Sci Rep 5: 12737. 10.1038/srep12737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koga S, Williams DS, Perriman AW, Mann S. 2011. Peptide-nucleotide microdroplets as a step towards a membrane-free protocell model. Nat Chem 3: 720–724. 10.1038/nchem.1110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CS, Putnam A, Lu T, He S, Ouyang JPT, Seydoux G. 2020. Recruitment of mRNAs to P granules by condensation with intrinsically-disordered proteins. Elife 9: e52896. 10.7554/eLife.52896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu K, Heng X, Garyu L, Monti S, Garcia EL, Kharytonchyk S, Dorjsuren B, Kulandaivel G, Jones S, Hiremath A, et al. 2011. NMR detection of structures in the HIV-1 5'-leader RNA that regulate genome packaging. Science 334: 242–245. 10.1126/science.1210460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma W, Zheng G, Xie W, Mayr C. 2021. In vivo reconstitution finds multivalent RNA-RNA interactions as drivers of mesh-like condensates. Elife 10: e64252. 10.7554/eLife.64252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal M, Boese B, Barrick JE, Winkler WC, Breaker RR. 2003. Riboswitches control fundamental biochemical pathways in Bacillus subtilis and other bacteria. Cell 113: 577–586. 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00391-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews DH, Sabina J, Zuker M, Turner DH. 1999. Expanded sequence dependence of thermodynamic parameters improves prediction of RNA secondary structure. J Mol Biol 288: 911–940. 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano S, Kirihata T, Fujii S, Sakai H, Kuwahara M, Sawai H, Sugimoto N. 2007. Influence of cationic molecules on the hairpin to duplex equilibria of self-complementary DNA and RNA oligonucleotides. Nucleic Acids Res 35: 486–494. 10.1093/nar/gkl1073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nalavade R, Griesche N, Ryan DP, Hildebrand S, Krauss S. 2013. Mechanisms of RNA-induced toxicity in CAG repeat disorders. Cell Death Dis 4: e752. 10.1038/cddis.2013.276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson JW, Atilho RM, Sherlock ME, Stockbridge RB, Breaker RR. 2017. Metabolism of free guanidine in bacteria is regulated by a widespread riboswitch class. Mol Cell 65: 220–230. 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.11.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nott TJ, Craggs TD, Baldwin AJ. 2016. Membraneless organelles can melt nucleic acid duplexes and act as biomolecular filters. Nat Chem 8: 569–575. 10.1038/nchem.2519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onuchic PL, Milin AN, Alshareedah I, Deniz AA, Banerjee PR. 2019. Divalent cations can control a switch-like behavior in heterotypic and homotypic RNA coacervates. Sci Rep 9: 12161. 10.1038/s41598-019-48457-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paithankar KR, Prasad KS. 1991. Precipitation of DNA by polyethylene glycol and ethanol. Nucleic Acids Res 19: 1346. 10.1093/nar/19.6.1346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel A, Malinovska L, Saha S, Wang J, Alberti S, Krishnan Y, Hyman AA. 2017. ATP as a biological hydrotrope. Science 356: 753–756. 10.1126/science.aaf6846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poudyal RR, Pir Cakmak F, Keating CD, Bevilacqua PC. 2018. Physical principles and extant biology reveal roles for RNA-containing membraneless compartments in origins of life chemistry. Biochemistry 57: 2509–2519. 10.1021/acs.biochem.8b00081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poudyal RR, Guth-Metzler RM, Veenis AJ, Frankel EA, Keating CD, Bevilacqua PC. 2019a. Template-directed RNA polymerization and enhanced ribozyme catalysis inside membraneless compartments formed by coacervates. Nat Commun 10: 490. 10.1038/s41467-019-08353-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poudyal RR, Keating CD, Bevilacqua PC. 2019b. Polyanion-assisted ribozyme catalysis inside complex coacervates. ACS Chem Biol 14: 1243–1248. 10.1021/acschembio.9b00205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poudyal RR, Meyer MO, Bevilacqua PC. 2021. Measuring the activity and structure of functional RNAs inside compartments formed by liquid-liquid phase separation. Methods Enzymol 646: 307–327. 10.1016/bs.mie.2020.06.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor DJ, Kierzek E, Kierzek R, Bevilacqua PC. 2003. Restricting the conformational heterogeneity of RNA by specific incorporation of 8-bromoguanosine. J Am Chem Soc 125: 2390–2391. 10.1021/ja029176m [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putnam A, Cassani M, Smith J, Seydoux G. 2019. A gel phase promotes condensation of liquid P granules in Caenorhabditis elegans embryos. Nat Struct Mol Biol 26: 220–226. 10.1038/s41594-019-0193-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regulski EE, Breaker RR. 2008. In-line probing analysis of riboswitches. Methods Mol Biol 419: 53–67. 10.1007/978-1-59745-033-1_4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riback JA, Katanski CD, Kear-Scott JL, Pilipenko EV, Rojek AE, Sosnick TR, Drummond DA. 2017. Stress-triggered phase separation is an adaptive, evolutionarily tuned response. Cell 168: 1028–1040.e19. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.02.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha S, Weber CA, Nousch M, Adame-Arana O, Hoege C, Hein MY, Osborne-Nishimura E, Mahamid J, Jahnel M, Jawerth L, et al. 2016. Polar positioning of phase-separated liquid compartments in cells regulated by an mRNA competition mechanism. Cell 166: 1572–1584.e16. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.08.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakya A, King JT. 2018. DNA local-flexibility-dependent assembly of phase-separated liquid droplets. Biophys J 115: 1840–1847. 10.1016/j.bpj.2018.09.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelke SA, Shao Y, Laski A, Koirala D, Weissman BP, Fuller JR, Tan X, Constantin TP, Waggoner AS, Bruchez MP, et al. 2018. Structural basis for activation of fluorogenic dyes by an RNA aptamer lacking a G-quadruplex motif. Nat Commun 9: 4542. 10.1038/s41467-018-06942-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherlock ME, Sadeeshkumar H, Breaker RR. 2019. Variant bacterial riboswitches associated with nucleotide hydrolase genes sense nucleoside diphosphates. Biochemistry 58: 401–410. 10.1021/acs.biochem.8b00617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J, Calidas D, Schmidt H, Lu T, Rasoloson D, Seydoux G. 2016. Spatial patterning of P granules by RNA-induced phase separation of the intrinsically-disordered protein MEG-3. Elife 5: e21337. 10.7554/eLife.21337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thrierr JC, Dourlent M, Leng M. 1971. A study of polyuridylic acid. J Mol Biol 58: 815–830. 10.1016/0022-2836(71)90042-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyrrell J, Weeks KM, Pielak GJ. 2015. Challenge of mimicking the influences of the cellular environment on RNA structure by PEG-induced macromolecular crowding. Biochemistry 54: 6447–6453. 10.1021/acs.biochem.5b00767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Treeck B, Protter DSW, Matheny T, Khong A, Link CD, Parker R. 2018. RNA self-assembly contributes to stress granule formation and defining the stress granule transcriptome. Proc Natl Acad Sci 115: 2734–2739. 10.1073/pnas.1800038115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg Z, Breaker RR. 2011. R2R—software to speed the depiction of aesthetic consensus RNA secondary structures. BMC Bioinformatics 12: 3. 10.1186/1471-2105-12-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young PR, Kallenbach NR. 1978. Secondary structure in polyuridylic acid. J Mol Biol 126: 467–479. 10.1016/0022-2836(78)90053-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zadeh JN, Steenberg CD, Bois JS, Wolfe BR, Pierce MB, Khan AR, Dirks RM, Pierce NA. 2011. NUPACK: analysis and design of nucleic acid systems. J Comput Chem 32: 170–173. 10.1002/jcc.21596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Yang M, Duncan S, Yang X, Abdelhamid MAS, Huang L, Zhang H, Benfey PN, Waller ZAE, Ding Y. 2019. G-quadruplex structures trigger RNA phase separation. Nucleic Acids Res 47: 11746–11754. 10.1093/nar/gkz978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.