Abstract

Glutathione (GSH) is a critical cellular antioxidant that protects against byproducts of aerobic metabolism and other reactive electrophiles to prevent oxidative stress and cell death. Proper maintenance of its reduced form, GSH, in excess of its oxidized form, GSSG, prevents oxidative stress in the kidney and protects against the development of chronic kidney disease. Evidence has indicated that renal concentrations of GSH and GSSG, as well as their ratio GSH/GSSG, are moderately heritable, and past research has identified polymorphisms and candidate genes associated with these phenotypes in mice. Yet those discoveries were made with in silico mapping methods that are prone to false positives and power limitations, so the true loci and candidate genes that control renal glutathione remain unknown. The present study utilized high-resolution gene mapping with the Diversity Outbred mouse stock to identify causal loci underlying variation in renal GSH levels and redox status. Mapping output identified a suggestive locus associated with renal GSH on murine chromosome X at 51.602 Mbp, and bioinformatic analyses identified apoptosis-inducing factor mitochondria-associated 1 (Aifm1) as the most plausible candidate. Then, mapping outputs were compiled and compared against the genetic architecture of the hepatic GSH system, and we discovered a locus on murine chromosome 14 that overlaps between hepatic GSH concentrations and renal GSH redox potential. Overall, the results support our previously proposed model that the GSH redox system is regulated by both global and tissue-specific loci, vastly improving our understanding of GSH and its regulation and proposing new candidate genes for future mechanistic studies.

Keywords: Kidney, Glutathione, Redox, QTL analysis, Systems genetics

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Glutathione is an endogenous antioxidant and key regulator of the cellular redox environment [1]. It is a tripeptide consisting of glutamate, glycine, and cysteine; the reactive thiol on the cysteine residue confers the molecule with its characteristic redox activity and is specifically denoted in its abbreviation, GSH. GSH is oxidized directly by reactive oxygen species (ROS) or via enzymatic reactions, producing the dimer GSSG, which is recycled back to two molecules of GSH by the cell’s antioxidant machinery. Though cellular GSH and GSSG concentrations are dynamic, their ratio (GSH/GSSG), is an informative and convenient marker of oxidative stress.

The kidneys have among the highest concentrations of GSH in the body, second only to the liver [2, 3]. The kidneys are dependent on GSH for phase II metabolism and detoxification of xenobiotics, particularly in the proximal tubules [4]. High GSH concentrations in the kidney are achieved via multiple mechanisms: normal intracellular synthesis and also import of circulating GSH [4], which mostly originates in the liver [5, 6]. In fact, the kidneys are the primary consumer of circulating GSH [6, 7], regularly hydrolyzing the GSH tripeptide to its constituent amino acids at the cell membrane, absorbing them, and then using those amino acids for GSH resynthesis or protein synthesis [8]. Robust levels of renal GSH are essential for preventing oxidative stress and progression of chronic renal diseases [9–12], as markers of ROS and oxidative damage are elevated in chronic kidney disease (CKD) [13, 14]. Moreover, maintenance of renal GSH concentrations is critical to averting other comorbidities, namely diabetes and cardiovascular diseases [13].

Given the importance of GSH in preventing oxidative stress, researchers have investigated the relationships between polymorphisms in genes encoding core GSH enzymes and renal diseases in humans. For instance, glutathione peroxidase (GPX) uses glutathione to convert hydrogen peroxide to water [15], and GPX1 polymorphisms have been associated with increased risk of chronic kidney disease (rs17080528) [16] and diabetes-related kidney complications (rs3448) [17].In addition, a genetic variant of GPX1 (rs17080528) has been associated with CKD and glomerular filtration rate, while a GPX4 variant (rs713041) has been associated with hypertension [16]. Glutathione S-transferases (GSTs) are critical in renal detoxification as they conjugate xenobiotic compounds with GSH to facilitate their excretion [16, 18], and variants in GST genes have been linked with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) [18]. However, the relationship between renal outcomes and these polymorphisms is not entirely understood, as a separate study on Chinese patients documented no association between a GPX1 variant (rs1050450; Pro197Leu) and ESRD [19].

Recent evidence has revealed that GSH status is dictated, in part, by genetic background in both mice [2, 3, 2022] and humans [23] and proposed novel genes and loci responsible for this variation [3]. In particular, a comprehensive mouse strain panel composed of 30 inbred strains documented over a 3-fold difference in renal GSH/GSSG and used in silico tools to identify novel candidate genes associated with renal glutathione homeostasis[3]; follow-up studies determined that the characteristic variation and heritability is conserved across the lifespan [2]. These initial genetic analyses were the first to utilize genome mapping technologies to document the genetic regulation of the renal GSH system, yet inbred strains do not reflect the genetic diversity found in humans and more precise methods are needed to validate the results from those early in silico studies.

In the present study, we sought to experimentally define the genetic loci and candidate genes associated with renal GSH. We used the Diversity Outbred (DO), a powerful mouse model whose genetic and phenotypic diversity is comparable to that of humans and facilitates high-precision mapping of quantitative trait loci (QTL) [24, 25]. We characterized the genetic architecture of renal GSH and contrasted the results against those of hepatic GSH, illustrating an overlapping locus between tissues. Overall, this is the largest and most precise genetic mapping study on the genetics of renal GSH, and our results suggest candidate genes that will steer future research in renal oxidative stress and disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and genotyping

Diversity Outbred (DO) mice (J:DO; JAX® #009376; N = 348 mice; 171 males and 177 females) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory and imported to the University of Georgia. Mice arrived at approximately 4 weeks of age, kept on a 12h light/dark cycle, and given ad libitum access to water and standard chow diet (LabDiet®, St. Louis, MO USA, product 5053) until 5–6 months of age. On the date of harvest, mice were fasted for 3–4 hours during the light phase and then humanely euthanized by cervical dislocation and kidneys were collected for analysis. The University of Georgia Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) approved all methods and procedures involving animals in accordance with the ethical standards of the institution (AUP #A2016 07–016), and all methods and procedures meet the International Guiding Principles for Biomedical Research Involving Animals, as issued by the Council for the International Organizations of Medical Sciences.

Clinical measurements and analysis

Fasting blood was collected via the submandibular vein after mice underwent a 3–4 hour fast during the light cycle and were briefly anesthetized with 2.75% isoflurane in an isoflurane chamber at 3 months of age. All blood samples clotted for 30 minutes to 1 hour and were then immediately centrifuged at 10,000 RPM (9,391 RCF) at 4°C for 5 minutes for serum extraction. Serum samples were stored at −80°C until analysis. Serum samples were submitted to, and analyzed by, the Clinical Pathology Department at the University of Georgia Veterinary Medical Center. Serum blood urea nitrogen (BUN) was quantified using the Cobas 6000 c501 Analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN USA).

Assessment of renal total glutathione, GSH, GSSG, and redox ratios

Kidneys were promptly harvested from each mouse after humane euthanasia and rinsed with ice-cold PBS, blotted on a paper towel, and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. Kidney tissue was processed within 12h after euthanasia and samples were homogenized in PBS containing 10 mM diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA), then promptly acidified with an equal volume of ice-cold 10% perchloric acid (PCA) containing 1 mM DTPA based on previously published methods [2, 26]. The acidified samples were then centrifuged at 15,000 RPM and 4°C for 15 minutes, and the acidified supernatant was collected and filtered.All filtered supernatant samples were stored at −80°C until analyzed. Each filtered sample was analyzed by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) coupled with electrochemical detection (Dionex Ultimate 3000, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA USA) based on previously published methods [27]. The mobile phase consisted of 4.0% acetonitrile, 0.1% pentafluoropropionic acid, and 0.02% ammonium hydroxide with a flow rate of 0.22 mL/min and 5.0 μL injection volume. A conditioning cell (+500 mV) was placed immediately before the boron-doped diamond cell (+1475 mV) with a cleaning potential at +1900 mV between samples. GSH and GSSG peaks were quantified using GSH and GSSG standards, external calibration, and the Chromeleon Chromatography Data System Software (Dionex Version 7.2, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA USA) and both GSH and GSSG concentrations were standardized to total protein (Pierce BCA Protein Assay, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA USA) and expressed in nmol/mg protein. Total glutathione concentrations were calculated through [GSH] + [2GSSG]. The GSH/GSSG ratio was calculated through and the redox potential (Eh) of the GSSG-GSH pair (2GSH → GSSG + 2e− + 2H+) was quantified in each sample using the Nernst equation , where Eh = measured cell potential, E0 = standard electrode potential for GSSG/2GSH (−264 mV at pH 7.4 [28–30]), R = gas constant (8.3145 J x mol−1 x K−1), T = temperature in Kelvin (40°C = 313.15 K), n = number of electrons transferred (2), F = Faraday’s constant (96485 C x mol−1), ox = molar concentration of oxidant (GSSG), and red = molar concentration of reductant (GSH), for a final equation of: .

Genotyping

Tail tips were collected at euthanasia from all 348 mice. Samples were submitted to GeneSeek (Neogen Genomics, Lincoln, NE USA, 68504) for DNA extraction and genotyped using the third-generation Mouse Universal Genotyping Array (GigaMUGA) [31], which is a 143K-probe array built on the Illumina Infinium II platform and optimized for DO genetic mapping.

Quantitative trait loci (QTL) mapping

Genome scans were performed in 345 (170 males, 175 females) of the original 348 DO samples; 2 mice were excluded from QTL analysis because they were XO females, and 1 was excluded due to low call rates. QTL analysis was conducted using the R/qtl2 software [25]. Sex and experimental cohort were included in the genome scans as additive covariates. To ensure normality, each phenotype underwent rank z-score transformation [32], and kinship among the DO mice was accounted for using the “leave one chromosome out” (LOCO) method [25, 33]. 1000 permutation tests were run for each genome scan to determine autosomal significance thresholds [25, 34, 35]. We applied a suggestive threshold (p-value ≤ 0.20) for reporting QTL loci [35]. For phenotype scans with QTL peaks greater than LOD score 6 on the X chromosome, separate permutation tests (18090 total) were run for the X chromosome using the perm_Xsp = TRUE function. A suggestive threshold (p ≤ 0.20) was applied for reporting loci [35], and a 95% Bayesian credible interval was determined for each peak around the reported QTL position [25, 34]. The Best Linear Unbiased Predictors (BLUPs) model within R/qtl2 was used to estimate allelic contributions of the eight founder strains [36]. Genes within intervals were plotted in connection with the Mouse Genome Informatics (MGI) database. All genotype data, genotype probabilities, and marker information are publicly available through figshare (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.c.5360501.v1). All source code, phenotype data, and other files used in QTL analyses are available through a public GitHub repository (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4683884).

Candidate gene analysis

Databases for expression, functional, and phenotypic annotations relevant to the kidney were queried for candidate gene prioritization based on previously published methods [37, 38]. We collected all protein-coding and functional RNA genes within the significant QTL intervals ± 1 Mbp reported by R/qtl2 using the Unified Mouse Genome Feature Catalog within the Mouse Genome Informatics (MGI) database [38]. For each gene, we collected gene expression annotations from the Gene eXpression Database (GXD) [39] through MGI [40]. All expression notations were confirmed using the EBI Expression Atlas (EEA) [41]. InterPro [42] and Gene Ontology (GO) annotations [43, 44] obtained through MGI [40] were collected to document gene function, and phenotypic data relevant to the kidney was collected from PheWeb [45] and Ensembl BioMart [46].

Statistical analysis

RStudio version 1.3.1093 (RStudio, PBC., Boston, MA) and R version 4.0.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) were used to determine descriptive statistics and identify relationships between variables. We calculated Rank-based Spearman’s rho (ρ) to report correlations between values. A relationship between variables with a p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Renal GSH concentrations and redox status vary significantly among DO mice

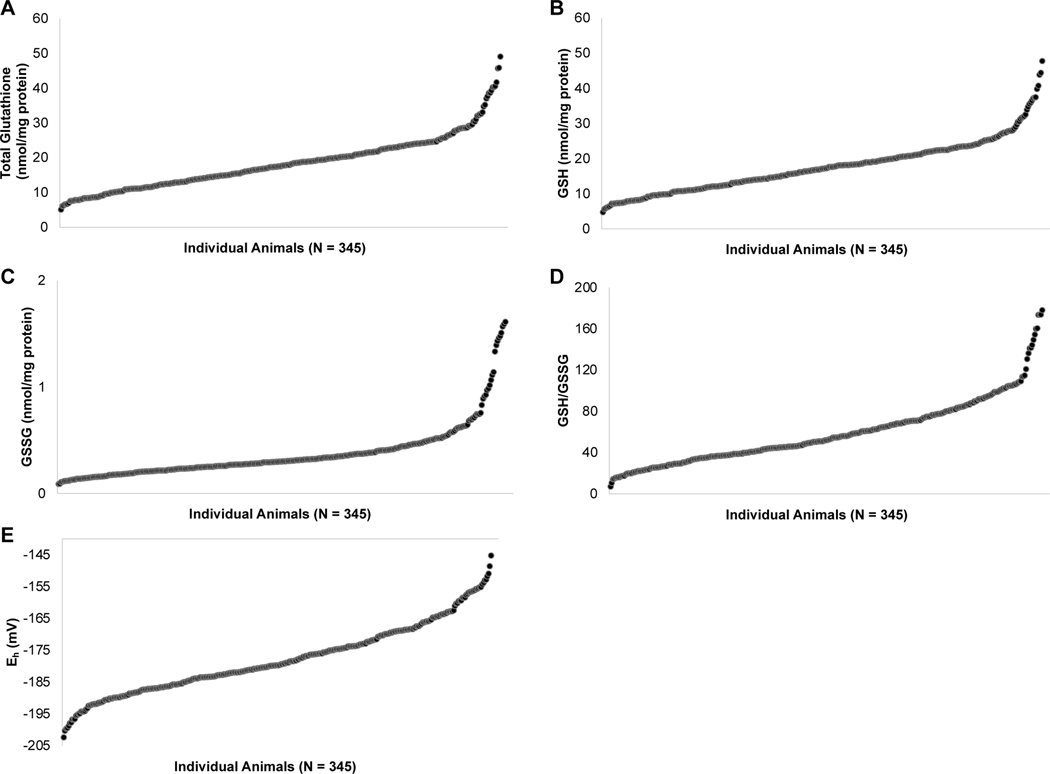

We measured renal concentrations of GSH and GSSG, their ratio GSH/GSSG, and redox potential in a large cohort (N=345) of DO mice and observed substantial variation across all phenotypes (Supplementary Table S1; Figure 1). Renal total glutathione concentrations varied nearly 10-fold (5.069 to 49.074 nmol/mg), similar to the variation seen in renal GSH concentrations (4.744 to 47.712 nmol/mg). Renal GSSG concentrations varied 18-fold, ranging from 0.088 to 1.612 nmol/mg, and the extremes in renal GSH/GSSG values differed by 26-fold (6.855 to 177.900). Renal Eh levels ranged from −202.380 to −145.203 mV, a 1.4-fold difference. There were no sex specific effects observed for any phenotype except for renal GSSG (Supplementary Tables S2 and S3). Variation of BUN is outlined in Supplementary Figure S1. Due to aggressive behavior, 62 males had to be individually housed. Since GSH is sensitive to external stressors, we performed Mann-Whitney tests and confirmed that all GSH system markers were not significantly different between animals individually housed compared to those housed in groups.

Figure 1. Renal glutathione concentrations and redox status vary greatly in the DO population.

In a cohort of genetically-diverse DO mice, kidneys were isolated and the following phenotypes were quantified: A) concentrations of total glutathione (GSH + 2GSSG, expressed in nmol/mg); B) concentrations of GSH (nmol/mg); C) concentrations of GSSG (nmol/mg); D) GSH/GSSG; and E) redox potential of the GSSG-GSH couple, expressed as Eh (mV). Values are arranged from least to greatest to illustrate the range of each phenotype, and the number of animals (N) included in the measurement is provided underneath each panel.

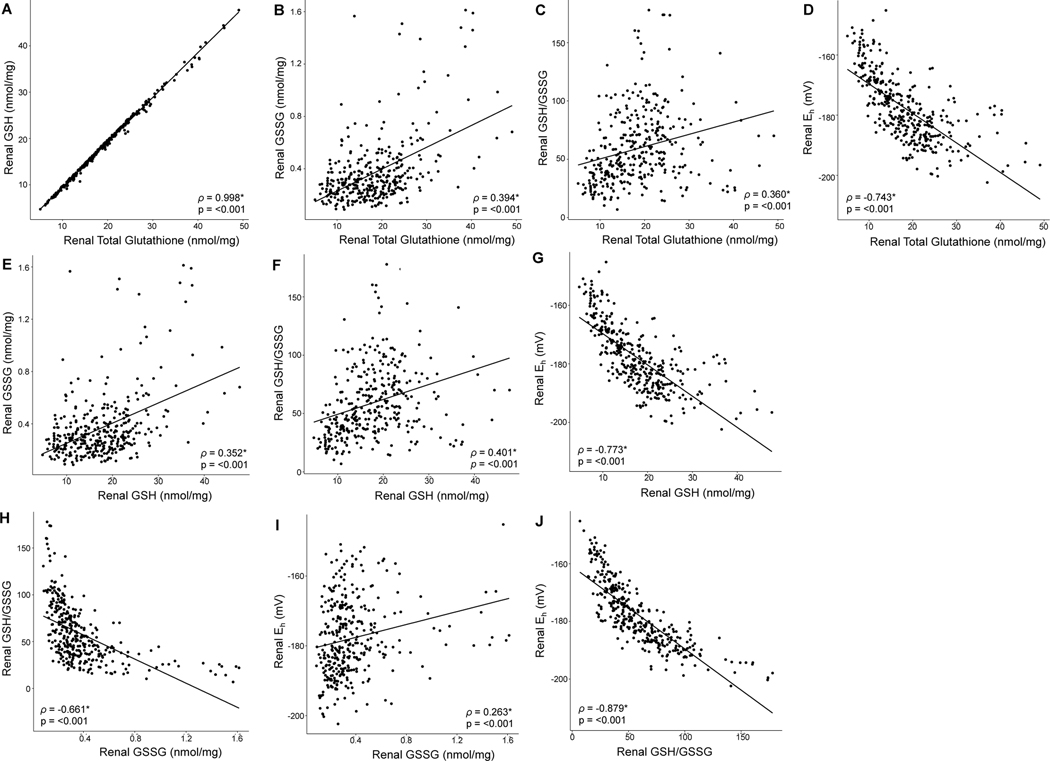

We screened for statistical correlations among variables and discovered multiple significant associations (Figure 2). Renal total glutathione concentrations were positively correlated with renal GSH concentrations (ρ = 0.998, p = <0.001), renal GSSG concentrations (ρ = 0.394, p = <0.001), renal GSH/GSSG levels (ρ = 0.360, p = <0.001), and negatively correlated with renal Eh levels (ρ = −0.743, p = <0.001). Similarly, renal GSH concentrations were also positively correlated with renal GSSG concentrations (ρ = 0.352, p = <0.001), renal GSH/GSSG levels (ρ = 0.401, p = <0.001), and negatively correlated with renal Eh levels (ρ = −0.773, p = <0.001). Renal GSSG concentrations had an additional positive correlation with renal Eh (ρ = 0.263, p = <0.001) and negative correlation with renal GSH/GSSG levels (ρ = −0.661, p = <0.001). Lastly, renal GSH/GSSG levels were negatively correlated with renal Eh (ρ = −0.879, p = <0.001). Correlations between serum BUN and renal GSH system markers are included in Supplementary Table S4.

Figure 2. Markers of the renal GSH redox system are correlated in the DO population.

In the top row, total glutathione concentrations (x-axis) are plotted against A) GSH concentrations, B) GSSG concentrations, C) GSH/GSSG levels, and D) Eh levels. In the middle row, GSH concentrations (x-axis) are plotted against E) GSSG concentrations, F) GSH/GSSG levels, and G) Eh levels. On the bottom row, GSSG concentrations (x-axis) are plotted against H) GSH/GSSG levels, and I) Eh levels. Panel J) shows GSH/GSSG levels (x-axis) plotted against Eh levels. Spearman’s rho (ρ) was calculated for each variable combination and listed within each corresponding box. * indicates a significant relationship (p ≤ 0.05). The corresponding p-value was listed underneath each ρ value. Total glutathione, GSH, and GSSG concentrations were standardized as nmol/mg protein. Eh was expressed as mV.

QTL mapping of renal GSH redox system markers

We performed genome-wide analysis using R/qtl2 on renal concentrations of total glutathione, GSH, GSSG, as well as GSH/GSSG and redox potential (Figure 3). We initially ran 1000 permutation tests in each QTL scan to identify LOD score thresholds to assess significance for autosomes. For scans that had QTL peaks with a LOD score > 6 on mouse chromosome X, we ran separate permutation tests (18090 total) using the perm_Xsp function to identify X chromosome-specific significance thresholds. Suggestive QTL peaks (p ≤ 0.20) were investigated using bioinformatics resources to identify plausible candidate genes. Genome-wide scans for renal concentrations of total glutathione and GSH revealed suggestive QTL peaks (p ≤ 0.10) on mouse chromosome X (LOD scores 7.105 and 6.962, respectively). Given that the peak position and QTL intervals were the same between the two scans, genome scan results for renal GSH are included in Figure 3, and total glutathione results are found in Supplementary Figure S2. Renal total glutathione and GSH scans revealed an additional peak that surpassed LOD score of 6 yet failed to meet significance thresholds on mouse chromosome 11 (LOD scores 6.428 and 6.664, respectively). Candidate gene results for the chromosome 11 peaks are included in Supplementary Table S5 and Supplementary Figures S3 and S4. QTL results for the genome scan of BUN are included in Supplementary Figure S1.

Figure 3. QTL mapping of renal GSH concentrations and redox status reveals distinct genetic architectures.

Genome-wide scans were generated for renal A) total glutathione concentrations (GSH + 2GSSG, expressed as nmol/mg); B) GSH concentrations (nmol/mg); C) GSSG concentrations (nmol/mg); D) GSH/GSSG; and E) redox potential of the GSSG-GSH couple (Eh, expressed as mV). Permutation-derived significance thresholds for each scan were indicated by colored lines at significance (α) levels 0.05 (blue), 0.1 (red), and 0.2 (purple). PanelsA and Binclude X chromosome-specific significance thresholds since they had QTL peaks with LOD scores greater than 6 on the X chromosome.

The suggestive peak (p<0.10) on mouse chromosome X, associated with renal concentrations of total glutathione and GSH, was further explored and defined by the following location: 51.602 Mbp with a QTL interval of 49.234 – 51.892 Mbp (Figure 4A). Founder allele effects showed that the NOD, NZO, and 129 alleles contributed to lower renal concentrations of total glutathione and GSH, whereas the AJ and PWK alleles contributed to higher renal concentrations of total glutathione and GSH (Figure 4B). R/qtl2 was used to plot genes located within this interval ± 1 Mbp (Figure 4C), and functional RNA and protein coding genes were collected and screened for physiological relevance (Supplementary Table S6). The QTL interval contained 63 possible candidate genes – 29 protein-coding, 32 non-coding RNA, and 2 unclassified (GRCm38/mm10; gene query performed February 2021, Feature Type “gene” [38]). 37 of the 63 candidate genes had limited renal expression annotations and were therefore excluded. Out of the remaining 26 candidate genes, 2 did not have functional annotations and were excluded, and out of the remaining 24 genes, 4 had additional phenotypic annotations related to renal function or redox metabolism: apoptosis-inducing factor, mitochondrion-associated 1 (Aifm1), immunoglobulin superfamily, member 1 (Igsf1), glypican 3 (Gpc3), and coiled-coil domain containing protein 160 (Ccdc160). Aifm1 (ChrX: 48474944–48513563 bp; 25.68 cM; GRCmm38) functions as a NADH oxidoreductase and regulator of apoptosis [47]. A query in Ensembl BioMart revealed that Aifm1 is associated with increased catalase activity (MP:0011593), increased superoxide dismutase (SOD) levels (MP:0012660), increased cellular sensitivity to hydrogen peroxide (MP:0008406), and oxidative stress (MP:0003674) in mice. In humans, AIFM1 was linked with combined oxidative phosphorylation deficiency 6 (300816) [46]. Igsf1 is a transmembrane glycoprotein whose function is largely unknown. It is expressed by thyrotropin (TSH)-producing cells in the pituitary gland and can cause central hypothyroidism [48]. We noted phenotypic annotations of Igsf1 related to chronic kidney disease, Stage I or II (p = 8.6e-7) and pyelonephritis (p = 4.1e-6) in humans [45]. However, the large majority of Igsf1 expression and action is in the pituitary gland, and it is unlikely that Igsf1 is responsible for glutathione metabolism variation in the kidneys. Gpc3 is part of the glypican family which are heparan sulfate proteoglycans linked to the cell surface through a glycosyl–phosphatidylinositol anchor [49]. GPC3 was linked with Wilms Tumor (194070), nephroblastoma (654), and Simpson–Golabi–Behmel (SGB) syndrome (373, 312870) in humans [46]. SGB overgrowth syndrome causes as wide variety of congenital defects, including renal dysplasia and nephromegaly [50]. Gpc3-deficient mice serve as a model of human renal dysplasia and GPC3 has been linked with modulating the actions of stimulatory and inhibitory growth factors during branching morphogenesisin renal tissue [51]. There is limited research on the action of GPC3 in the kidneys, though it has been shown to reduce cell proliferation in renal carcinoma cells [52]. We were unable to find literature documenting associations between Gpc3 or Igsf1 expression and oxidative stress. Lastly, Ccdc160 was linked with nephritis and nephropathy without mention of glomerulonephritis (p = 3.8e-5) [45].

Figure 4. High-resolution association mapping for renal GSH concentrations reveals a suggestive QTL on mouse chromosome X.

A) Genome-wide scan of renal GSH concentrations (nmol/mg) in outbred mice shows a QTL with peak LOD score 6.962 at 51.602 Mbp (28.205 cM) on mouse chromosome X. Permutation-derived significance thresholds are indicated by colored lines at significance (α) levels 0.05 (blue), 0.1 (red), and 0.2 (purple). Autosome LOD score thresholds were 6.97, 7.33, and 7.80 for p-values of 0.20, 0.10, and 0.05, respectively. X chromosome LOD score thresholds were 6.50, 6.89, and 7.40 for p-values of 0.20, 0.10, and 0.05, respectively. B) The founder allele QTL effects indicate that the NOD, NZO, and 129 alleles contribute to a lower renal GSH (nmol/mg) concentration, whereas the AJ and PWK alleles contribute to a higher renal GSH (nmol/mg) concentration. Each colored line represents a DO founder allele as indicated in the legend. The differences between strains are considered significant when the LOD score (bottom) crosses significance thresholds (panel A). C) Candidate genes found within the QTL interval relative to the MGI database. The renal total glutathione genome scan resulted in the same suggestive QTL interval on mouse chromosome X compared to renal GSH (Supplementary Figure S4).

Comparison of the renal and hepatic GSH redox systems

Since renal GSH pools are formed, in part, from GSH originating in the liver [53, 54], we screened for statistical correlations between the renal GSH variables measured in the present study and those measured in the livers of the same DO population [84]. We observed multiple significant associations between GSH variables in the kidney and liver (Figure 5). Since this population of DO mice had been previously studied for hepatic NAD(P)H dynamics as well, we screened for associations between hepatic NAD(P)H variables and the renal GSH system markers measured in the present study (Supplementary Table S7). Correlations between BUN and hepatic GSH system markers are included in Supplementary Table S4 as well.

Figure 5. Markers of the renal and hepatic GSH redox systems are correlated within the same cohort of DO mice.

Renal and hepatic GSH concentrations and redox statuses were pooled and screened for statistical relationships. In the first row, renal total glutathione concentrations (x-axis) are plotted against A) hepatic total glutathione concentrations, B) hepatic GSH concentrations, C) hepatic GSSG concentrations, D) hepatic GSH/GSSG levels, and E) hepatic Eh levels. In the second row, renal GSH concentrations (x-axis) are plotted against F) hepatic total glutathione concentrations, G) hepatic GSH concentrations, H) hepatic GSSG concentrations, I) hepatic GSH/GSSG levels, and J) hepatic Eh levels. In the third row, renal GSSG concentrations (x-axis) are plotted against K) hepatic total glutathione concentrations, L) hepatic GSH concentrations, M) hepatic GSSG concentrations, N) hepatic GSH/GSSG levels, and O) hepatic Eh levels. In the fourth row, renal GSH/GSSG levels (x-axis) are plotted against P) hepatic total glutathione concentrations, Q) hepatic GSH concentrations, R) hepatic GSSG concentrations, S) hepatic GSH/GSSG levels, and T) hepatic Eh levels. In the fifth row, renal Eh levels (x-axis) are plotted against U) hepatic total glutathione concentrations, V) hepatic GSH concentrations, W) hepatic GSSG concentrations, X) hepatic GSH/GSSG levels, and Y) hepatic Eh levels. Spearman’s rho (ρ) was calculated for each variable combination and listed within each corresponding box. * indicates a significant relationship (p ≤ 0.05). The corresponding p-value was listed underneath each ρ value. Total glutathione, GSH, and GSSG concentrations were standardized as nmol/mg protein. Eh was expressed as mV.

Additionally, previous genetic mapping of hepatic GSH markers identified a novel locus on murine chromosome 16 associated with hepatic GSH/GSSG status [84]. We compiled that locus and all other QTL associated with either renal or hepatic GSH phenotypes with LOD scores greater than 6 (Supplementary Table S8). We found a QTL for renal Eh (mV) on mouse chromosome 14 at 22.959 (22.359 – 23.926) Mbp (LOD score 6.258) overlapping with a QTL peak for hepatic total glutathione and GSH on murine chromosome 14 at 22.506 (22.058 – 22.528) Mbp (LOD score 6.755 and 6.748 for GSH and total glutathione, respectively; Figure 6). In the locus underlying renal Eh levels, the NZO allele contributed to a lower renal Eh concentration whereas the CAST and NOD alleles contributed to a higher renal Eh level (Supplementary Figure S5B). In the locus underlying hepatic concentrations of total glutathione and GSH, the NZO allele contributed to lower hepatic total glutathione and GSH concentrations and the B6 allele contributed to higher concentrations. The specific overlapping region, spanning 22.058 – 23.926 ± 1 Mbp, contains many genes which were plotted using R/qtl2, and functional RNA and protein coding genes were collected and screened for physiological relevance using existing expression, functional, and phenotypic annotations for both the liver and kidney (Supplementary Table S9). The QTL interval contained 68 possible candidate genes: 16 protein-coding, 44 non-coding RNA, and 8 unclassified (GRCm38/mm10; gene query performed February 2021, Feature Type “gene” [38]). 44 of the 68 genes were not expressed in the liver and kidney and were excluded as candidates. Out of the remaining 24 candidate genes, 12 did not have functional annotations and were excluded, and out of the remaining 12 genes, 9 had additional phenotypic annotations related to liver and/or kidney function: adenosine kinase (Adk), K(lysine) acetyltransferase 6B (Kat6b), dual specificity phosphatase and pro isomerase domain containing 1 (Dupd1), dual specificity phosphatase 13 (Dusp13), sterile alpha motif domain containing 8 (Samd8), zinc finger protein 503 (Zfp503), leucine rich melanocyte differentiation associated (Lrmda), potassium calcium-activated channel subfamily M alpha 1 (Kcnma1), discs large MAGUK scaffold protein 5 (Dlg5). Additionally, voltage dependent anion channel 2 (Vdac2) did not have additional phenotypic annotations, though it is a known participant in redox signaling in Saccharomyces cerevisiae [55], and in rat hearts, VDAC is involved in superoxide anion release from the mitochondria into the cytoplasm [56]. A comprehensive literature search was inconclusive on which gene is the most plausible candidate.

Figure 6. A locus on murine chromosome 14 overlaps between hepatic and renal GSH markers.

Genome-wide QTL plots for hepatic GSH markers and renal Eh levels were compared using R/qtl2. In panel A, the QTL plot for renal Eh levels was overlayed onto the QTL plot for hepatic total glutathione (nmol/mg). A dashed arrow connects to panel C which shows the overlapping locus on murine chromosome 14 at approximately 22.5 Mbp. In the same manner, panel B shows the QTL plot for renal Eh levels overlayed onto the QTL plot for hepatic GSH (nmol/mg). A dashed arrow connects to panel D which shows the overlapping locus on murine chromosome 14 at approximately 22.5 Mbp.

DISCUSSION

GSH plays an important role in renal protection and health, and studies have suggested that renal GSH status is dictated at least in part by genetics [2, 3, 20–23], yet the underlying loci and genes remain unknown. To address this knowledge gap, we used the DO stock, which contains a level of genetic diversity comparable to humans, and quantified renal GSH concentrations and redox status. Through comprehensive genetic mapping using R/qtl2, we documented novel loci associated with renal GSH and delineated a shared locus associated with both renal Eh and hepatic GSH, vastly expanding our understanding of renal GSH and its regulation.

QTL mapping of renal total glutathione and GSH suggested a novel locus on mouse chromosome X at 51.602 (49.234 – 51.892) Mbp. Renal total glutathione (GSH + 2GSSG) is disproportionately influenced by GSH concentrations, as opposed to GSSG, so it is reasonable to expect that the two phenotypes could have overlapping QTL peaks. Bioinformatics analyses identified candidate genes within the QTL, and our results suggested 4 candidates – Aifm1, Igsf1, Gpc3, and Ccdc160. Kidney-specific phenotypic annotations were documented for Igsf1, Gpc3, and Ccdc160, yet functional annotations were unrelated to cellular redox function. Therefore, we concluded that these three genes are unlikely to drive variation in renal GSH status. Instead, Aifm1 emerged as the most likely candidate gene underlying renal total glutathione and GSH concentrations, given its established role in regulating oxidative stress. AIFM1, also known as programmed cell death 8 (PDCD8), is a flavoprotein that functions as a NADH oxidoreductase and regulator of apoptosis independent of the caspase pathway [47, 57] while also playing roles in electron transport, ROS generation, ferredoxin metabolism, and immune system regulation [58]. AIFM1 is normally confined to the mitochondrial intermembrane space where it acts as an electron acceptor/donor with oxidoreductase activity [59]. After an apoptotic insult, the mitochondrial outer membrane is permeabilized, and AIFM1 translocates to the cytosol – then to the nucleus – to induce peripheral chromatin condensation and DNA fragmentation [60, 61]. Concurrently, cytochrome c is released from the mitochondrial membrane as it is permeabilized during caspase-dependent apoptosis [62]. Loss of AIFM1 and cytochrome c increases oxidative stress and ROS generation by disrupting the mitochondrial respiratory chain and membrane potential [59].

AIFM1 has a second role in the mitochondria: regulation of the electron transport chain by promoting formation of complex I [63]. Specifically, AIFM1 recruits and stabilizes MIA40 – an essential protein involved in complex I assembly – likely as a docking protein, recruiting factor, or redox intermediate [63]. AIFM1 also appears to alter complex I function independently of MIA40, though the exact mechanism is unknown [64]. When AIFM1 deficiency disrupts complex I formation and stability, the downstream effects include increased superoxide leakage and oxidative stress, decreased ATP formation, and alteration in mitochondrial-mediated apoptotic events [65]. Outside of the mitochondria, AIFM1 activity is still influenced by ROS. A surge in ROS alters the conformation of the canonical NRF2–KEAP1–PGAM5 complex and causes the complex to dissociate[66]. The untethered PGAM5 binds to AIFM1 to catalyze its dephosphorylation, and dephosphorylated AIFM1 activates caspase-independent cell death and blocks inflammation [66]. Freed NRF2 then upregulates expression of cytoprotective genes, including those involved in GSH metabolism, a mechanism to combat ROS [66, 67]. This response links AIFM1 to the concept of hormesis, where cells adapt to elevated ROS-induced stress by eliciting adaption mechanisms to resist oxidative stress, including upregulation of cytoprotective transcriptional factors and genes [68–73]. Hormesis has been cited as critical for protecting renal tissue against stress-induced injury [74, 75] and it is plausible that AIFM1 impacts the process via regulation of NRF2-KEAP1-PGAM5 and additional mechanisms not yet elucidated. Lastly, and perhaps most surprisingly, some evidence suggests that AIFM1 may even serve as a free radical scavenger [76]. The protein contains a pyridine nucleotide-disulphide oxidoreductase domain, common to bacterial hydrogen peroxide scavengers, and overexpression of AIFM1 in wild-type cerebellar granule cells decreases peroxide-mediated cell death [76]. However, the action of AIFM1 as an oxidant scavenger has been debated [77, 78], and additional research is needed.

Beyond cell studies, prior research has also tied Aifm1 to oxidative stress in vivo. Homozygous Aifm1-knockout mice are rendered embryonic lethal, illustrating the profound impact of the protein on growth and development [79]. The Aifm1Hq mouse model, also known as the Harlequin mutant, is a model of Aifm1 insufficiency, exhibiting lowered transcription and protein levels compared to wild-type controls [76]. In the cerebellum of Aifm1Hq mice, levels of two oxidative stress markers – lipid hydroperoxides and 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine – were higher than controls [76]. Concurrently, there was elevated catalase activity and total glutathione levels, likely an adaptation to combat oxidative stress [76]. These trends were not restricted to the brain, as catalase and SOD protein levels were increased in skeletal muscle samples of Aifm1Hq mice as well [65]. In humans, AIFM1 deficiency causes mitochondrial complex I activity and assembly loss [80, 81], resulting in combined oxidative phosphorylation deficiency 6 (OMIM #300816) [46]. Moreover, Aifm1 deficiency has been linked to renal pathologies, as Aifm1Hq mice exhibit markedly decreased AIFM1 levels in the kidneys, resulting in reduced complex I activity [65]. Interestingly, a partial knockdown of Aifm1 in mice resulted in CKD features with excess mitochondrial ROS production and NADPH oxidase 4 (Nox4) upregulation, yet these mice retained their complex I activity [82]. In humans, patients with diabetic nephropathy had reduced AIFM1 expression and protein concentrations as renal function decreased [82]; a decrease in AIFM1 expression may impair mitochondrial respiration, increasing ROS generation and eventually driving the progression of CKD [83]. Currently, it is unclear what effect AIFM1 variants have on renal health. To identify known Aifm1 variants in the DO founder strains, we queried Sanger SNP Viewer (Sanger release number 1410; https://churchilllab.jax.org/snpsnap/search) and identified 367 known polymorphisms. Future research will determine whether variants in Aifm1 affect GSH homeostasis and oxidative stress in renal tissue.

Of all known genes related to oxidative stress and antioxidant metabolism, it is striking that we identified Aifm1 as the candidate gene underlying renal GSH. And even more surprisingly, genetic mapping did not identify any QTL near canonical genes involved in GSH synthesis and metabolism. We hypothesized that such GSH genes lack significant allelic variation in the DO population and its founder strains, so they would not contribute to variation in GSH phenotypes. To test our hypothesis, we used R/qtl2 to visualize founder allele effects for GPx1, glutathione cysteine ligase – catalytic subunit (Gclc), glutathione cysteine ligase – modifier subunit (Gclm), glutathione synthetase (Gs), and Gr (Supplementary Figures S6 – S10) [84]. According to the data output, no haplotypes in these genes contribute to a significantly lower or higher GSH phenotype. These results support our hypothesis that novel loci and genes outside of the canonical GSH pathway are responsible for the variation in renal GSH concentrations and redox status. Yet we cannot rule out the influence of polymorphisms in GSH genes from the DO founder strains. We investigated all known single nucleotide polymorphisms in the DO population using Sanger (release number 1410) through the SNP Viewer (https://churchilllab.jax.org/snpsnap/search) and documented 8 Gpx1 variants, 534 Gclc variants, 115 Gclm variants, 429 Gs variants, and 943 Gr variants. Additionally, expression QTL (eQTL) could have influenced the expression of these canonical GSH metabolism genes. We identified known eQTL for renal Gpx1, Gclc, Gclm, Gs, and Gr expression in the DO population using the QTL Viewer through https://churchilllab.jax.org/qtlviewer/JAC/DOKidney. We noted eQTL for renal expression of Gclc (chromosome 4: 98.6979 Mbp, LOD score 7.0425; chromosome 6: 135.1814 Mbp, LOD score 6.6574), and Gclm (chromosome 3: 120.5554 Mbp, LOD score 13.9594), Gs (chromosome 4: 106.6555 Mbp, LOD score 7.4223; chromosome 12: 115.6087 Mbp, LOD score 6.7989), and Gr (chromosome 8: 34.1411 Mbp, LOD score 15.8493), whereas eQTL did not appear for renal Gpx1 expression.

To better understand how GSH regulation in the kidney compares to other tissues, we sought to determine the relationship between renal and hepatic GSH, the latter of which we explored in a distinct study [84]. We screened for statistical correlations and found that within the same DO cohort, renal GSH concentrations were positively correlated with hepatic GSH concentrations (ρ = 0.199, p = <0.001), renal GSH/GSSG values were positively correlated with hepatic GSH/GSSG values (ρ = 0.150, p = 0.005), and renal Eh values were positively correlated with hepatic Eh values (ρ = 0.238, p = <0.001), pointing to the relatedness between the systems. Then, we tested for genetic correlations by comparing loci associated with the renal GSH phenotypes with those previously identified for the hepatic GSH phenotypes [84]. We documented a locus overlapping between the renal Eh and hepatic GSH (and total glutathione) concentrations on mouse chromosome 14. Through bioinformatic query, we identified 10 candidate genes within the region: Adk, Kat6b, Dupd1, Dusp13, Samd8, Zfp503, Lrmda, Kcnma1, Dlg5, and Vdac2. Despite a comprehensive literature search on each gene, we were not yet able to delineate which gene is the most plausible for influencing renal and hepatic GSH systems alike. Overall, these results suggest that the renal and hepatic GSH redox systems are under both shared and tissue-specific genetic control, and future research will build upon our findings by identifying and validating the causative gene on chromosome 14 that influences hepatic and renal GSH simultaneously.

Previously, we mapped polymorphisms associated with renal GSH in mice using in silico techniques [3]. Because that approach has inherent limitations, it was essential to map renal GSH using the DO, though we also compared the present QTL results with those of our past study. We did not observe any peaks that directly overlap between our QTL results and those discovered in silico. Yet it must be noted that QTL peaks for renal GSH and total glutathione on mouse chromosome 11 at 100.810 (100.059 – 101.369) Mbp and 100.804 (100.059 – 101.369) Mbp, respectively, were near an in silico peak discovered for renal GSH at 93.177 Mbp on mouse chromosome 11. Similarly, a QTL peak for renal GSSG on mouse chromosome 1 at 144.970 (143.603 – 148.590) Mbp was in proximity to an in silico peak for renal GSH at 138.112 Mbp on mouse chromosome 1. Ideally, future studies will investigate and validate the candidate genes we present here, rather than building upon those collected in silico, as the power and precision of DO mapping far surpasses that of in silico studies.

CONCLUSION

We explored the renal GSH redox system using a novel systems genetics approach based on the Diversity Outbred (DO) mouse stock, a model of human genetic diversity. Using a large cohort of DO mice, we identified a novel QTL peak underlying renal concentrations of total glutathione and GSH on chromosome X and identified Aifm1 as the most plausible candidate gene within that region, given its function in redox metabolism and the mitochondrial electron transport chain. Secondarily, we compared our genetic mapping results with that of the hepatic GSH system and discovered a shared locus on murine chromosome 14, suggesting that the two systems are under both shared and tissue-specific control and highlighting a list of novel candidate genes within the locus. Overall, Aifm1 is an exciting candidate gene associated with renal GSH – and an unexpected discovery considering the large number of established antioxidant and pro-oxidant genes in the genome. Future studies will interrogate Aifm1 as a direct regulator of renal GSH, and the results will considerably expand upon our knowledge of the renal GSH redox system, its genetic regulation, and its broader impact on disease.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Genetically-diverse mice exhibited considerable variation in renal GSH

A suggestive locus on murine chromosome X was associated with renal GSH

Bioinformatic analyses highlighted Aifm1 as best candidate gene on chromosome X

Renal and hepatic GSH phenotypes were statistically correlated

A locus on murine chromosome 14 is shared between renal Eh and hepatic GSH

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge Dan Gatti for his input on study design, Kristen Peissig, Mallory Johns, Kylah Chase, Aida Rassam, and Madeleine Williams for their assistance with the data collection, Vivek Phillip and Belinda Cornes for their assistance with the genetic mapping process, and Ali Ennis for creating the graphical abstract.

FUNDING SOURCES

This work was supported by the following National Institutes of Health grants: National Institute of General Medical Sciences R01GM121551 and the National Institute on Aging R56 AG053309.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- [1].Sies H, Glutathione and its role in cellular functions, Free Radic Biol Med 27(9–10) (1999) 916–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Gould RL, Zhou Y, Yakaitis CL, Love K, Reeves J, Kong W, Coe E, Xiao Y, Pazdro R, Heritability of the aged glutathione phenotype is dependent on tissue of origin, Mamm Genome 29(9) (2018) 619–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Zhou Y HD, Love-Myers K, Chen Y, Grider A, Wickwire K, Burgess JR, Stochelski MA, Pazdro R, Genetic analysis of tissue glutathione concentrations and redox balance, Free Radic Biol Med 71 (2014) 157–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Lash LH, Role of glutathione transport processes in kidney function, Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 204(3) (2005) 329–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Forman H ZH, Rinna A, Glutathione: Overview of its protective roles, measurement, and biosynthesis, Mol Aspects Med 30(1–2) (2009) 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Lash LH, Renal Membrane Transport of Glutathione in Toxicology and Disease, Vet Pathol 48(2) (2010) 408–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Potter DW, Tran TB, Apparent rates of glutathione turnover in rat tissues, Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 120(2) (1993) 186–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].McIntyre TM, Curthoys NP, The interorgan metabolism of glutathione, Int J Biochem 12(4) (1980) 545–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Ling XC, Kuo K-L, Oxidative stress in chronic kidney disease, Ren Replace Ther 4(1) (2018) 53. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Himmelfarb J, Stenvinkel P, Ikizler TA, Hakim RM, The elephant in uremia: oxidant stress as a unifying concept of cardiovascular disease in uremia, Kidney international 62(5) (2002) 1524–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Zuo M.-h, Tang J, Xiang M.-m., Long Q, Dai J.-p., Yu G.-d., Zhang H.-g., Hu H, Clinical observation of the reduced glutathione in the treatment of diabetic chronic kidney disease, J Cell Biochem 120(5) (2019) 8483–8491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Hagen TM, Aw TY, Jones DP, Glutathione uptake and protection against oxidative injury in isolated kidney cells, Kidney international 34(1) (1988) 74–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Signorini L, Granata S, Lupo A, Zaza G, Naturally Occurring Compounds: New Potential Weapons against Oxidative Stress in Chronic Kidney Disease, International journal of molecular sciences 18(7) (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Witko-Sarsat V, Friedlander M, Nguyen Khoa T, Capeillère-Blandin C, Nguyen AT, Canteloup S, Dayer JM, Jungers P, Drüeke T, Descamps-Latscha B, Advanced oxidation protein products as novel mediators of inflammation and monocyte activation in chronic renal failure, J Immunol 161(5) (1998) 2524–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Ursini F, Maiorino M, Glutathione Peroxidases, in: Lennarz WJ, Lane MD (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Biological Chemistry (Second Edition), Academic Press, Waltham, 2013, pp. 399–404. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Corredor Z, Filho M.I.d.S., Rodríguez-Ribera L, Velázquez A, Hernández A, Catalano C, Hemminki K, Coll E, Silva I, Diaz JM, Ballarin J, Vallés Prats M, Calabia Martínez J, Försti A, Marcos R, Pastor S, Genetic Variants Associated with Chronic Kidney Disease in a Spanish Population, Sci Rep 10(1) (2020) 144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Mohammedi K, Patente TA, Bellili-Muñoz N, Driss F, Le Nagard H, Fumeron F, Roussel R, Hadjadj S, Corrêa-Giannella ML, Marre M, Velho G, Glutathione peroxidase-1 gene (GPX1) variants, oxidative stress and risk of kidney complications in people with type 1 diabetes, Metabolism 65(2) (2016) 12–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Agrawal S, Tripathi G, Khan F, Sharma R, Baburaj VP, Relationship between GSTs gene polymorphism and susceptibility to end stage renal disease among North Indians, Ren Fail 29(8) (2007) 947–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Chao C-T, Chen Y-C, Chiang C-K, Huang J-W, Fang C-C, Chang C-C, Yen C-J, Interplay between Superoxide Dismutase, Glutathione Peroxidase, and Peroxisome Proliferator Activated Receptor Gamma Polymorphisms on the Risk of End-Stage Renal Disease among Han Chinese Patients, Oxid Med Cell Longev 2016 (2016) 8516748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Rebrin I FM, Sohal RS, Effects of age and caloric intake on glutathione redox state in different brain regions of C57BL/6 and DBA/2 mice, Brain Res 1127(1) (2007) 10–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Rebrin I FM, Sohal RS, Association between life-span extension by caloric restriction and thiol redox state in two different strains of mice, Free Radic Biol Med 51(1) (2011) 225–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Ferguson M RI, Forster M, Sohal R, Comparison of metabolic rate and oxidative stress between two different strains of mice with varying response to caloric restriction, Exp Gerontol 43(8) (2008) 757–763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].van ‘t Erve TJ, Wagner BA, Ryckman KK, Raife TJ, Buettner GR, The concentration of glutathione in human erythrocytes is a heritable trait, Free Radic Biol Med 65 (2013) 742–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Churchill GA, Gatti DM, Munger SC, Svenson KL, The Diversity Outbred mouse population, Mamm Genome 23(9–10) (2012) 713–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Broman KW, Gatti DM, Simecek P, Furlotte NA, Prins P, Sen S, Yandell BS, Churchill GA, R/qtl2: software for mapping quantitative trait loci with high dimensional data and multi-parent populations, Genetics 211(2) (2019) 495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Park HJ, Mah E, RS B, Validation of high-performance liquid chromatography boron-doped diamond detection for assessing hepatic glutathione redox status, Anal Biochem 407 (2010) 151–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Park H, Mah E, Bruno R, Validation of high-performance liquid chromatography boron-doped diamond detection for assessing hepatic glutathione redox status, Anal Biochem 407(2) (2010) 151–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Wang X, Wang Q, Andersson R, Bengmark S, Intramucosal pH and oxygen extraction in the gastrointestinal tract after major liver resection in rats, Eur J Surg 159(2) (1993) 81–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Ziegler TR, Panoskaltsus-Mortari A, Gu LH, Jonas CR, Farrell CL, Lacey DL, Jones DP, Blazar BR, Regulation of glutathione redox status in lung and liver by conditioning regimens and keratinocyte frowth factor in murine allogeneic bone marrow transplantation, Transplantation 72(8) (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Rost J, Rapoport S, Reduction potential of glutathione, Nature 201 (1964) 185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Morgan AP, Fu C-P, Kao C-Y, Welsh CE, Didion JP, Yadgary L, Hyacinth L, Ferris MT, Bell TA, Miller DR, Giusti-Rodriguez P, Nonneman RJ, Cook KD, Whitmire JK, Gralinski LE, Keller M, Attie AD, Churchill GA, Petkov P, Sullivan PF, Brennan JR, McMillan L, Pardo-Manuel de Villena F, The Mouse Universal Genotyping Array: From Substrains to Subspecies, G3 6(2) (2016) 263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Svenson KL, Gatti DM, Valdar W, Welsh CE, Cheng R, Chesler EJ, Palmer AA, McMillan L, Churchill GA, High-Resolution Genetic Mapping Using the Mouse Diversity Outbred Population, Genetics 190(2) (2012) 437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Yang J, Zaitlen NA, Goddard ME, Visscher PM, Price AL, Advantages and pitfalls in the application of mixed-model association methods, Nature Genet 46(2) (2014) 100–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Sen S, Churchill GA, A statistical framework for quantitative trait mapping, Genetics 159(1) (2001) 371–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Churchill GA, Doerge RW, Empirical threshold values for quantitative trait mapping, Genetics 138(3) (1994) 963–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Robinson GK, That BLUP is a Good Thing: The Estimation of Random Effects, Stat Sci 6(1) (1991) 15–32. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Recla JM, Robledo RF, Gatti DM, Bult CJ, Churchill GA, Chesler EJ, Precise genetic mapping and integrative bioinformatics in Diversity Outbred mice reveals Hydin as a novel pain gene, Mamm Genome 25(5–6) (2014) 211–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Spanidis Y, Mpesios A, Stagos D, Goutzourelas N, Bar‑Or D, Karapetsa M, Zakynthinos E, Spandidos DA, Tsatsakis AM, Leon G, Kouretas D, Assessment of the redox status in patients with metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes reveals great variations, Exp Ther Med 11(3) (2016) 895–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Finger JH, Smith CM, Hayamizu TF, McCright IJ, Xu J, Law M, Shaw DR, Baldarelli RM, Beal JS, Blodgett O, Campbell JW, Corbani LE, Lewis JR, Forthofer KL, Frost PJ, Giannatto SC, Hutchins LN, Miers DB, Motenko H, Stone KR, Eppig JT, Kadin JA, Richardson JE, Ringwald M, The mouse Gene Expression Database (GXD): 2017 update, Nucleic Acids Res 45(D1) (2017) D730–d736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Blake JA, Eppig JT, Kadin JA, Richardson JE, Smith CL, Bult CJ, Mouse Genome Database (MGD)-2017: community knowledge resource for the laboratory mouse, Nucleic Acids Res 45(D1) (2017) D723–d729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Petryszak R, Keays M, Tang YA, Fonseca NA, Barrera E, Burdett T, Füllgrabe A, Fuentes AM, Jupp S, Koskinen S, Mannion O, Huerta L, Megy K, Snow C, Williams E, Barzine M, Hastings E, Weisser H, Wright J, Jaiswal P, Huber W, Choudhary J, Parkinson HE, Brazma A, Expression Atlas update-an integrated database of gene and protein expression in humans, animals and plants, Nucleic Acids Res 44(D1) (2016) D746–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Finn RD, Attwood TK, Babbitt PC, Bateman A, Bork P, Bridge AJ, Chang HY, Dosztányi Z, El-Gebali S, Fraser M, Gough J, Haft D, Holliday GL, Huang H, Huang X, Letunic I, Lopez R, Lu S, Marchler-Bauer A, Mi H, Mistry J, Natale DA, Necci M, Nuka G, Orengo CA, Park Y, Pesseat S, Piovesan D, Potter SC, Rawlings ND, Redaschi N, Richardson L, Rivoire C, Sangrador-Vegas A, Sigrist C, Sillitoe I, Smithers B, Squizzato S, Sutton G, Thanki N, Thomas PD, Tosatto SC, Wu CH, Xenarios I, Yeh LS, Young SY, Mitchell AL, InterPro in 2017-beyond protein family and domain annotations, Nucleic Acids Res 45(D1) (2017) D190–d199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, Harris MA, Hill DP, Issel-Tarver L, Kasarskis A, Lewis S, Matese JC, Richardson JE, Ringwald M, Rubin GM, Sherlock G, Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium, Nat Genet 25(1) (2000) 25–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Expansion of the Gene Ontology knowledgebase and resources, Nucleic Acids Res 45(D1) (2017) D331–d338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Gagliano Taliun SA, VandeHaar P, Boughton AP, Welch RP, Taliun D, Schmidt EM, Zhou W, Nielsen JB, Willer CJ, Lee S, Fritsche LG, Boehnke M, Abecasis GR, Exploring and visualizing large-scale genetic associations by using PheWeb, Nat Genet 52(6) (2020) 550–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Kinsella RJ, Kähäri A, Haider S, Zamora J, Proctor G, Spudich G, Almeida-King J, Staines D, Derwent P, Kerhornou A, Kersey P, Flicek P, Ensembl BioMarts: a hub for data retrieval across taxonomic space, Database 2011 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [47].Sevrioukova IF, Redox-linked conformational dynamics in apoptosis-inducing factor, J Mol Biol 390(5) (2009) 924–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Turgeon MO, Silander TL, Doycheva D, Liao XH, Rigden M, Ongaro L, Zhou X, Joustra SD, Wit JM, Wade MG, Heuer H, Refetoff S, Bernard DJ, TRH Action Is Impaired in Pituitaries of Male IGSF1-Deficient Mice, Endocrinology 158(4) (2017) 815–830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Cano-Gauci DF, Song HH, Yang H, McKerlie C, Choo B, Shi W, Pullano R, Piscione TD, Grisaru S, Soon S, Sedlackova L, Tanswell AK, Mak TW, Yeger H, Lockwood GA, Rosenblum ND, Filmus J, Glypican-3-deficient mice exhibit developmental overgrowth and some of the abnormalities typical of Simpson-Golabi-Behmel syndrome, J Cell Biol 146(1) (1999) 255–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Sajorda BJ, Gonzalez-Gandolfi CX, Hathway ER, Kalish JM, Simpson-Golabi-Behmel syndrome type 1, University of Washington, Seattle, Seattle (WA), 2006. [Google Scholar]

- [51].Grisaru S, Cano-Gauci D, Tee J, Filmus J, Rosenblum ND, Glypican-3 modulates BMP- and FGF-mediated effects during renal branching morphogenesis, Dev Biol 231(1) (2001) 31–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Valsechi MC, Oliveira ABB, Conceição ALG, Stuqui B, Candido NM, Provazzi PJS, de Araújo LF, Silva WA Jr., Calmon M.d.F., Rahal P, GPC3 reduces cell proliferation in renal carcinoma cell lines, BMC cancer 14 (2014) 631–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Shang Y, Siow YL, Isaak CK, O K, Downregulation of Glutathione Biosynthesis Contributes to Oxidative Stress and Liver Dysfunction in Acute Kidney Injury, Oxid Med Cell Longev 2016 (2016) 9707292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Purucker E, Marschall H-U, Geier A, Gartung C, Matern S, Increase in renal glutathione in cholestatic liver disease is due to a direct effect of bile acids, Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 283(6) (2002) F1281–F1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Galganska H, Budzinska M, Wojtkowska M, Kmita H, Redox regulation of protein expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae mitochondria: possible role of VDAC, Arch Biochem Biophys 479(1) (2008) 39–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Han D, Antunes F, Canali R, Rettori D, Cadenas E, Voltage-dependent anion channels control the release of the superoxide anion from mitochondria to cytosol, J Biol Chem 278(8) (2003) 5557–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Miramar MD, Costantini P, Ravagnan L, Saraiva LM, Haouzi D, Brothers G, Penninger JM, Peleato ML, Kroemer G, Susin SA, NADH oxidase activity of mitochondrial apoptosis-inducing factor, J Biol Chem 276(19) (2001) 16391–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Morton SU, Prabhu SP, Lidov HGW, Shi J, Anselm I, Brownstein CA, Bainbridge MN, Beggs AH, Vargas SO, Agrawal PB, AIFM1 mutation presenting with fatal encephalomyopathy and mitochondrial disease in an infant, Cold Spring Harb Mol Case Stud 3(2) (2017) a001560–a001560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Bano D, Prehn JHM, Apoptosis-Inducing Factor (AIF) in Physiology and Disease: The Tale of a Repented Natural Born Killer, EBioMedicine 30 (2018) 29–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Daugas E, Susin SA, Zamzami N, Ferri KF, Irinopoulou T, Larochette N, Prévost MC, Leber B, Andrews D, Penninger J, Kroemer G, Mitochondrio-nuclear translocation of AIF in apoptosis and necrosis, FASEB J 14(5) (2000) 729–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Yuste V, Lorenzo H-K, Susin SA, AIFM1 (apoptosis-inducing factor, mitochondrion-associated, 1), Atlas Genet Cytogenet Oncol Haematol 12 (2008) 190–194. [Google Scholar]

- [62].Garrido C, Galluzzi L, Brunet M, Puig PE, Didelot C, Kroemer G, Mechanisms of cytochrome c release from mitochondria, Cell Death Differ 13(9) (2006) 1423–1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Meyer K, Buettner S, Ghezzi D, Zeviani M, Bano D, Nicotera P, Loss of apoptosis-inducing factor critically affects MIA40 function, Cell Death & Disease 6(7) (2015) e1814–e1814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Hu B, Wang M, Castoro R, Simmons M, Dortch R, Yawn R, Li J, A novel missense mutation in AIFM1 results in axonal polyneuropathy and misassembly of OXPHOS complexes, Eur J Neurol 24(12) (2017) 1499–1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Bénit P, Goncalves S, Dassa EP, Brière J-J, Rustin P, The Variability of the Harlequin Mouse Phenotype Resembles that of Human Mitochondrial-Complex I-Deficiency Syndromes, PLOS ONE 3(9) (2008) e3208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Kesavardhana S, Kanneganti T-D, Stressed-out ROS take a silent death route, Nat Immunol 19(2) (2018) 103–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Lo S-C, Hannink M, PGAM5 tethers a ternary complex containing Keap1 and Nrf2 to mitochondria, Exp Cell Res 314(8) (2008) 1789–1803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Calabrese V, Cornelius C, Dinkova-Kostova AT, Calabrese EJ, Mattson MP, Cellular stress responses, the hormesis paradigm, and vitagenes: novel targets for therapeutic intervention in neurodegenerative disorders, Antioxidants & Redox Signaling 13(11) (2010) 1763–1811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Calabrese V, Cornelius C, Dinkova-Kostova AT, Iavicoli I, Di Paola R, Koverech A, Cuzzocrea S, Rizzarelli E, Calabrese EJ, Cellular stress responses, hormetic phytochemicals and vitagenes in aging and longevity, Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease 1822(5) (2012) 753–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Calabrese V, Renis M, Calderone A, Russo A, Reale S, Barcellona ML, Rizza V, Stress proteins and SH-groups in oxidant-induced cellular injury after chronic ethanol administration in rat, Free Radic Biol Med 20(3) (1996) 391–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Calabrese V, Signorile A, Cornelius C, Mancuso C, Scapagnini G, Ventimiglia B, Ragusa N, Dinkova-Kostova A, Practical approaches to investigate redox regulation of heat shock protein expression and intracellular glutathione redox state, Methods Enzymol 441 (2008) 83–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Cornelius C, Graziano A, Perrotta R, Paola RD, Cuzzocrea S, Calabrese EJ, Calabrese V, Chapter 26 - Cellular Stress Response, Hormesis, and Vitagens in Aging and Longevity: Role of mitochondrial “Chi”, in: Rahman I, Bagchi D. (Eds.), Inflammation, Advancing Age and Nutrition, Academic Press, San Diego, 2014, pp. 309–321. [Google Scholar]

- [73].Siracusa R, Scuto M, Fusco R, Trovato A, Ontario ML, Crea R, Di Paola R, Cuzzocrea S, Calabrese V, Anti-inflammatory and Anti-oxidant Activity of Hidrox(®) in Rotenone-Induced Parkinson’s Disease in Mice, Antioxidants (Basel, Switzerland: ) 9(9) (2020) 824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Swaminathan S, Iron, hormesis, and protection in acute kidney injury, Kidney international 90(1) (2016) 16–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Park KM, Byun JY, Kramers C, Kim JI, Huang PL, Bonventre JV, Inducible nitric-oxide synthase is an important contributor to prolonged protective effects of ischemic preconditioning in the mouse kidney, J Biol Chem 278(29) (2003) 27256–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Klein JA, Longo-Guess CM, Rossmann MP, Seburn KL, Hurd RE, Frankel WN, Bronson RT, Ackerman SL, The harlequin mouse mutation downregulates apoptosis-inducing factor, Nature 419(6905) (2002) 367–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Sevrioukova IF, Apoptosis-inducing factor: structure, function, and redox regulation, Antioxid Redox Signal 14(12) (2011) 2545–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Churbanova IY, Sevrioukova IF, Redox-dependent changes in molecular properties of mitochondrial apoptosis-inducing factor, J Biol Chem 283(9) (2008) 5622–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Brown D, Yu BD, Joza N, Bénit P, Meneses J, Firpo M, Rustin P, Penninger JM, Martin GR, Loss of Aif function causes cell death in the mouse embryo, but the temporal progression of patterning is normal, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103(26) (2006) 9918–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Vahsen N, Candé C, Brière J-J, Bénit P, Joza N, Larochette N, Mastroberardino PG, Pequignot MO, Casares N, Lazar V, Feraud O, Debili N, Wissing S, Engelhardt S, Madeo F, Piacentini M, Penninger JM, Schägger H, Rustin P, Kroemer G, AIF deficiency compromises oxidative phosphorylation, EMBO J 23(23) (2004) 4679–4689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Bénit P, Goncalves S, Dassa EP, Brière JJ, Rustin P, The variability of the harlequin mouse phenotype resembles that of human mitochondrial-complex I-deficiency syndromes, PLOS ONE 3(9) (2008) e3208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Coughlan MT, Higgins GC, Nguyen TV, Penfold SA, Thallas-Bonke V, Tan SM, Ramm G, Van Bergen NJ, Henstridge DC, Sourris KC, Harcourt BE, Trounce IA, Robb PM, Laskowski A, McGee SL, Genders AJ, Walder K, Drew BG, Gregorevic P, Qian H, Thomas MC, Jerums G, Macisaac RJ, Skene A, Power DA, Ekinci EI, Wijeyeratne XW, Gallo LA, Herman-Edelstein M, Ryan MT, Cooper ME, Thorburn DR, Forbes JM, Deficiency in Apoptosis-Inducing Factor Recapitulates Chronic Kidney Disease via Aberrant Mitochondrial Homeostasis, Diabetes 65(4) (2016) 1085–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Cañadas-Garre M, Anderson K, Cappa R, Skelly R, Smyth LJ, McKnight AJ, Maxwell AP, Genetic Susceptibility to Chronic Kidney Disease – Some More Pieces for the Heritability Puzzle, Front Genet 10(453) (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].The Jackson Laboratory, Mouse Genome Database (MGD) at the Mouse Genome Informatics website, 2020.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.