Abstract

The human gut microbiota harbors a heterogeneous and dynamic community of microorganisms that coexist with the host to exert a marked influence on human physiology and health. Throughout the lifespan, diet can shape the composition and diversity of the members of the gut microbiota by determining the microorganisms that will colonize, persist, or become extinct. This is no more pronounced than during early-life succession of the gut microbiome when food type and source changes relatively often and food preferences are established, which is largely determined by geographic location and the customs and cultural practices of that environment. These dietary selection pressures continue throughout life, as society has become increasingly mobile and as we consume new foods to which we have had no previous exposure. Dietary selection pressures also come in the form of overall reduction or excess such as with the growing problems of food insecurity (lack of food) as well as of dietary obesity (overconsumption). These are well-documented forms of dietary selection pressures that have profound impact on the gut microbiota that ultimately may contribute to or worsen disease. However, diets and dietary components can also be used to promote healthy microbial functions in the gut, which will require tailored approaches taking into account an individual’s personal history and doing away with one-size-fits-all nutrition. Herein, we summarize current knowledge on major dietary selection pressures that influence gut microbiota structure and function across and within populations, and discuss both the potential of personalized dietary solutions to health and disease and the challenges of implementation.

Keywords: Diet, Nutrition, Obesity, Malnutrition, Microbiome

Abbreviations used in this paper: MAC, microbially accessible carbohydrate; MDCF, microbiota-directed complementary food; SCFA, short-chain fatty acid

Summary.

We present an overview of dietary selection pressures on the gut microbiome, from the perspective of undernutrition and overnutrition, and reflect on the wealth of data on global dietary patterns to understand the geographical differences in gut microbiome community structure.

Assembly of the microbiota begins at birth and can take between 1 and 3 years to mature to a composition more reflective of the adult microbiome.1, 2, 3 The early gut microbial colonization process is thought to contribute to early education and imprinting of the infant’s metabolic and immunological development and subsequent physiological homeostasis in life. Conversely, marked deviations in gut microbiota configuration or function are thought to underlie the onset and progression of several health disorders.4,5 Thus, a robust and diverse gut microbiota remains vital to the preservation of human health. It is not entirely understood what defines a healthy adult gut microbial profile as variability in species richness, diversity and stability are often used as markers,6 and these vary greatly between individuals in general, and especially across geographic locations.5,7

Diet has long been recognized as a major external determinant of these interindividual differences. Changes in the gut microbiota or the metabolism of dietary components by gut microbiota may affect the absorption of dietary nutrients. Indeed, consumption of various nutrients affects the gut microbial community structure and provides substrates for microbial metabolism. In turn, the gut microbiota can produce small molecules that are absorbed by the host and affect several vital physiological processes.6,8,9 Human lifestyle or geographical differences beget gut microbiota differences and these can be due to associated differences in diet or cooking practices.10 For instance, there are differences in microbial richness in rural individuals consuming plant-based diets compared with consumers of high-meat and high-fat Western diets.11 Western diets trigger the loss of specific gut taxa, particularly those that can degrade complex carbohydrates, while these are highly abundant in the gut of individuals who consume rural diets.12 The progressive loss of microbial diversity over many generations13 in urban-industrialized societies coinciding with the upsurge of chronic diseases is thought to correlate with the decline in the consumption of dietary fiber,14 but this is likely multifactorial and is a combination of decreases in some dietary components and increases in others.

Short-term dietary changes can cause rapid but reversible shifts in the gut microbiota composition, while longer-term changes can alter the genomic composition and metabolic activities of microbiota.11,15,16 However, the alterations in the gut microbiota in response to different types of diet and lifestyle interventions are distinct. Even more, interindividual differences in microbial response to diets tend to dominate analyses, indicating that it is almost impossible to design a universal dietary plan for all individuals.4,8 Thus, microbiota features have emerged as crucial biomarkers to predict responsiveness to dietary interventions that should be taken into consideration during the design of personalized nutrition strategies.17 Herein, we summarize current knowledge on major dietary selection pressures that influence gut microbiota structure and function across populations, and strategies for selectively tuning the gut microbiota in a personalized approach between individuals. The gut microbiota is highly plastic in its composition and function, and as such dietary manipulation represents an attractive and low-risk strategy to alter the gut microbiota ecosystem. Ultimately, research along this avenue will revolutionize the field of nutrition including advances in precision nutrition and the development of next-generation microbiota-based therapeutics to combat specific diseases and improve health.

Global Dietary Patterns: Rural Vs Urban

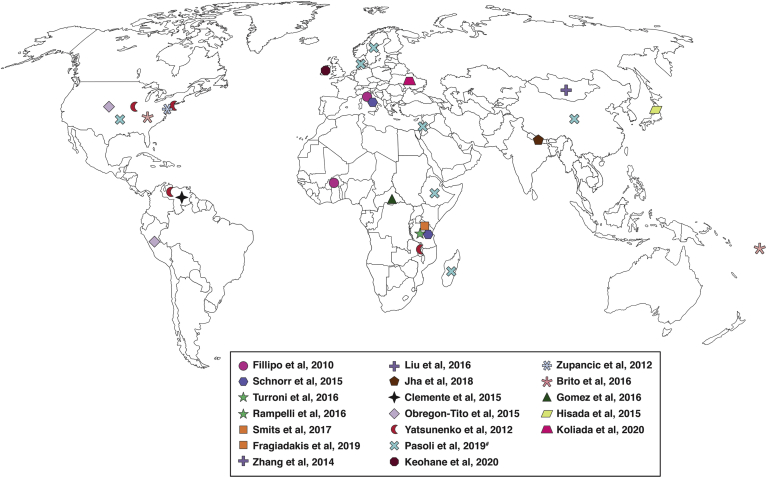

Diet plays a critical role in shaping the gut microbial community structure and function, with an overall impact on health. Dietary habits or practices have been observed to be strongly connected with geography, cultural practices, lifestyle, and socioeconomic status. Studies from different populations have revealed wide variations in the relative proportions of core taxa in the gut microbial community of individuals (Figure 1). Important headways in this area began to emerge roughly a decade ago.

Figure 1.

Geographic locations and populations represented in existing studies on global dietary effects on the gut microbiome. Symbols of the same color represent populations included in a given study.

An early population study by Filippo et al18 investigated the impact of diet on the microbiota by analyzing the gut microbiota of rural children from Burkina Faso compared with the microbiota from counterparts in an industrialized environment in Italy. Rural Burkinabe children who consumed a plant-rich diet were markedly enriched in Bacteroidetes, which are credited for breakdown of polysaccharides, and were depleted in Firmicutes. Conversely these observations were not seen in the Italian children. Also, high proportions of complex carbohydrate degraders such as Prevotella and Xylanibacter, which strongly associate with increased levels of fecal short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), were present in the rural children. The Burkinabe children also displayed increased microbial richness and diversity and a notably reduced representation of pathogenic Enterobacteriaceae taxa. These observed differences were not linked to ethnic backgrounds, as the gut microbiota of children dwelling in urban Burkina Faso resembled more closely the gut microbiota of the Italian children than the rural children.18 This was among the first studies to highlight that rural vs urban lifestyles supersede ethnic distinctions when it comes to the microbiome. This concept that gut microbiota of rural dietary lifestyle vary from those of urban-Westernized dietary practice was further reinforced by the Gomez et al19 study, in which they demonstrated that the gut microbiota of traditional hunter-gatherer BaAka communites and the agriculturist Bantu communities in Central Africa Republic have distinct patterns from the gut microbiota of Westernized Americans. However, the Bantu microbiota harbor more Western-like features, an outcome suggesting an ongoing shift from a traditional practice toward a modern agricultural Western-like pattern. This finding is very consistent with the lifestyle of the Bantu people, who practice a combination of traditional hunter-gatherer and urban-Westernized diets or dietary style.19

The impact of urbanization or Westernization in shaping the gut microbiota has been recognized in multiple studies focusing on diverse aspects of the gut microbiome.20, 21, 22, 23, 24 A meta-analysis study of datasets of fecal samples from urbanized and preagricultural populations revealed that specific gut taxa appear to have been acquired or shed possibly due to dietary alterations that accompany the urbanization process.21 For instance, Treponema, an anaerobic bacterium involved in the degradation of resistant and complex fiber, was a common feature among traditional human communities, suggesting that they could be symbionts that became extinct over periods of urbanization.12,24 Another striking study that aimed to study this concept prospectively, and which possibly explains reduced microbial diversity and richness in industrialized populations, identified the decline in consumption of microbially accessible carbohydrates (MACs), which represent the complex portion of dietary fiber. Remarkably, the study found that in a humanized mouse model, a reduction in MAC consumption over generations could result in a progressive loss of microbial taxa including some fiber-fermenting species. The reintroduction of dietary MACs was so unsuccessful in recovering the lost gut microbial taxa that the authors concluded the MAC-degrading bacteria had become extinct.13 The long-term consequences of the complete loss of specific microbial taxa remain to be investigated. Collectively, data from these studies demonstrate that the gut microbiota is structurally and functionally more diverse among less developed native populations than in urban-industrialized populations,25, 26, 27, 28, 29 although causality needs to be validated. Interestingly, studies of the rural Amish in the United States and the nomadic Irish travelers in Ireland have suggested that the microbiota differences in these rural populations compared with urbanized populations may actually not be diet-related, but rather be related to regular interaction with outdoor animals such as livestock.25,30

Global Dietary Patterns: Seasonal Variation

A newly investigated area and added layer to the study of diets and gut microbiomes at the population level is the impact of seasonal variations in food availability. In Western societies, grocery stores stock the same meats and produce year-round, importing products that may be otherwise out of season locally. In the absence of such conveniences, however, food can only be consumed in the season in which they grow.

Nothing has exemplified this more than the study of the Hadza in Africa. Initial studies compared the Hadza hunter-gatherer population in Tanzania to urbanized populations, and results were consisted with many of the previously mentioned studies. The Hadza consume a diet rich in complex polysaccharides and display increased levels of microbial diversity, represented by high proportions of Bacteroides in comparison with Italian urban dwellers.12

A follow-up metagenomic analysis of the Hadza microbiome revealed an enrichment of carbohydrate-active enzymes, which are consistent with a foraging, polysaccharide-rich diet, yet retains the metabolic capability to metabolize branched-chain amino acids.29 Further, targeted metabolomic fecal profiling in this dataset showed unique enrichment in hexoses, glycerophospholipids, sphingolipids, and acylcarnitines, while the most available natural amino acids, fatty acids, and derivatives were poorly enriched, perhaps reflecting a gut microbiota phenotype less likely to develop or promote inflammation.31 The retained functional potential of the Hadza gut microbiome to metabolize both complex carbohydrates and proteins may be due to the seasonal changes in food availability, which was later studied by Smits et al32 in this same Hadza population. Here, they discovered indeed that the Hadza gut microbiome undergoes seasonal cycling in composition that coincides with the wet and dry season, with Prevotellaceae and Spirochaetaceae as the 2 most seasonally variable taxa. The proportion of Prevotellaceae dropped in the wet season, which correlated with a marked reduction of carbohydrate-active enzymes present in the metagenome, specific for plant carbohydrates.32 Seasonal cycling was not observed in any of the urbanized populations represented in this study, which is likely due to the relatively stable and consistent supply of most foods year-round. As a result, they also found that many bacterial species were completely absent from the gut microbiomes of industrialized populations compared with those that eat seasonally.

Season-dependent shifts in the microbial community composition in response to dietary changes have been demonstrated in several other populations as well. One of the earliest studies was conducted in the communal-living Hutterite population of North Dakota, whose summer diets are rich in high-fiber fresh fruits and vegetables. The summer gut microbiota of the Hutterites correlated with significantly increased abundance of Bacteroidetes, and a corresponding depletion in the abundances of Actinobacteria and Firmicutes compared with the winter season.33 Similar seasonal character in the microbial community composition has also been demonstrated in the traditional nomads of Mongolia,34,35 in middle-aged Japanese individuals,36 and more recently, in a cross-sectional study of a Ukrainian population.37 One study, however, was unable to detect seasonal variability in the microbiota composition in the hunter-gatherer Canadian Inuit population, which may be attributed to an increasing availability of Westernized foods throughout the year.38

Overall, studying global dietary patterns across degrees of urbanization, global location, and specific food availability contributes at the macro level to the immense heterogeneity seen in the gut microbiomes across the globe. This is a food type–specific observation driven by the types of foods consumed under the previous parameters, and when those foods are consumed. This is often how the gut microbiome is studied in the context of diet. However, another important dietary factor that can influence gut microbiome composition is presence or absence of food. At the extremes, this is manifested either as undernutrition or as overnutrition and overconsumption, both considered malnutrition phenotypes, which are global crises of public health concern.

Gut Microbiota in Undernutrition

Undernutrition is broadly characterized by inadequate intake of one or several nutrients or poor food quality, and can be initiated or worsened by persistent enteric infections.39 Undernutrition is usually assessed using World Health Organization public health indicators such as underweight (low weight for height < –2 SD), wasting (low weight for age < –2 SD), or stunting (low height for age < –2 SD), or having any macronutrient deficiencies. While stunting represents a form of chronic malnutrition, underweight and wasting are forms of acute malnutrition.40 The clinical manifestations of undernutrition include marasmus, a wasting syndrome without edema, and kwashiorkor, which results from protein deficiency and mostly marked by edema.

Pediatric undernutrition during the first 1000 days of life contributes to short-term and lifelong adverse outcomes including linear growth retardation, neurodevelopmental delay, poorer school progression, increased future risks of degenerative diseases, and mortality. Children experiencing undernutrition are typically treated with commercial nutrient-rich “ready-to-use therapeutic food” in combination with antibiotics, and that has resulted in a notable decline in mortality from approximately 40% to 5%.41,42 However, survivors of undernutrition are often unable to recover completely even after improvements in their body weight or mass.43 Moreover, long-term follow-ups report high mortality rates after seemingly successful nutritional interventions.43,44 This suggests that in addition to food insecurity, a network of interacting determinants that operate within and across generations may potentially reflect the incidence of childhood undernutrition in various populations.45,46 Indeed, the gut microbiota has been implicated as a major contributing factor in associated pathological events, driven by marked deviation in the normal assembly of the early gut microbiota.47, 48, 49

Several observational and interventional studies from diverse geographies have reported taxonomic and functional changes of the gut microbiota, enrichment in potential pathobionts and proinflammatory species, depletion in obligate anaerobes, and nutrient malabsorption in undernutrition.39,41,50 Monira et al51 provided one of the early snapshots into gut microbiota compositional changes of malnourished children. Their cross-sectional study that compared the gut microbiota of undernourished and well-nourished healthy children from Bangladesh observed markedly less diverse microbiota (decreased fecal microbiota community richness), a bloom in potentially pathogenic Proteobacteria including Klebsiella, Escherichia, and Neisseria and reduction in α-diversity in undernourished children.51 A separate cross-sectional study also demonstrated how the gut microbiota shifts in response to differing nutritional status. The study, conducted in 20 rural Indian children, disclosed a distinct group of 23 genera with varying proportions that correlate with the different nutritional settings spanning from healthy to severe acute malnutrition. Remarkably, relative proportions of Escherichia, Streptococcus, Shigella, Enterobacter, and Veillonella genera progressively increased in proportion with the decreasing nutritional index of children. Microbial genes associated with amino acid and carbohydrate transport and metabolism, as well as with energy production and conversion, positively correlated with nutritional status, thus identifying efficient nutrient utilization as a key distinguishing feature of healthy children in comparison with malnourished children.52

Subramanian et al53 analyzed the microbiota composition and community development of a healthy Bangladeshi birth cohort during the first 2 years of life by 16S ribosomal RNA amplicon sequencing from monthly collected fecal samples. Using a machine learning model, age-discriminatory microbial species and strains that defined a healthy microbiota maturation index for this cohort were identified, and that index was also shared by other unrelated healthy Bangladeshi children. Children with severe or moderate undernutrition showed notable deviations from this healthy age-associated microbiota index as their gut microbiota communities exhibited delayed development. Their microbiota resembled those of immature healthy children.53 Indeed, clinical studies provide further evidence that microbiota immaturity in children with severe acute undernutrition is not durably fixed even when administered either one of the two widely used food interventions. They revert to immature microbiota configurations following withdrawal of interventions,47,53 suggesting persistent developmental abnormality. Further corroboration of a similar immature microbiota was observed in undernourished children from Malawi by Blanton et al.49 The researchers conducted fecal transplants from either undernourished children or age-matched healthy counterparts into germ-free mice and fed them on the typical Malawian diet of the donors. The germ-free mice harboring microbiota from undernourished children developed poorly, manifested by decreased weight and lean body mass and alteration in bone morphometry. Microbial species including Ruminoccocus gnavus and Clostridium symbiosum were identified as predictive of improved weight and lean mass gain in Malawian children. Colonization of these growth-discriminatory taxa into young germ-free mice harboring an immature microbiota improved their growth and metabolic abnormalities.49,54 In a separate study, adult germ-free mice transplanted with the microbiota from an undernourished child exhibited a wasting phenotype.47 Collectively, these studies were the first to associate gut microbiota maturity with age-dependent anthropometric measures and disease pathogenesis related to nutrition status.

A more recent meta-analysis involving 5 geographic sites reported a significant loss of obligate or strict anaerobes in childhood undernutrition when age, sex, and recruitment center were controlled. Importantly, relative proportions of several species from Bacteroidaceae, Eubacteriaceae, Lachnospiraceae, and Ruminococceae families were depleted, whereas several aerotolerant species such as Escherichia coli, Enterococcus faecalis, and Staphylococcus aureus were consistently enriched. Furthermore, assessment of gut redox potential demonstrated significantly higher levels in undernourished children than in healthy control subjects. Together, their data provide insights potentially connecting the loss of specific gut microbes to gut redox changes in severely undernourished children.55 Other studies have sought to understand whether there are differences in gut microbial patterns among the different clinical phenotypes of undernutrition.44,56,57 Culturomic and metagenomic analyses demonstrated a decreasing microbial diversity gradient with the kwashiorkor microbiota when compared with children suffering from marasmus. Kwashiorkor gut microbiota was consistently overrepresented with potential pathogenic groups including Proteobacteria and Fusobacteria, and a complete loss of Methanobrevibacter smithii,44,58 whereas beneficial polysaccharide-rich taxa in Bacteroides were notably underrepresented in marasmus.56 A possibility for this may be that kwashiorkor is protein malnutrition during critical growth periods specifically, while marasmus is protein and energy malnutrition indicating a total reduction in calories including from fiber-rich foods.

Existing commercial therapeutic diets used to treat undernourished children are largely designed to increase nutrient intake but do not take into account how they impact the growth trajectory of the gut microbiota. This may explain to some extent why nutritional interventions are moderately effective in improving childhood growth as well as in sustaining long lasting health benefits. Growing evidence that the gut microbiota affects multiple aspects of human metabolism and physiology has stimulated efforts to develop microbiota-directed ready-to-use therapeutic foods as interventions to promote health. Owing to the profound and rapid impacts of diet in shaping microbial community dynamics and function, microbiota-directed foods present a promising choice for nutritional rehabilitation.58, 59, 60 Consistent with that notion, it was recently investigated whether microbiota-directed complementary foods (MDCFs), which are customized diets, could intentionally manipulate the immature microbiota of malnourished children toward a healthy microbiota, while potentially alleviating the long-lasting consequences of malnutrition. Preclinical animal models were used to screen various formulations of MDCFs based on locally sourced Bangladeshi ingredients to identify the effective MDCFs mostly likely to reverse immature microbiota features and aid recovery. The 3 most promising MDCFs were further tested in a randomized small-scale 1-month clinical trial in malnourished Bangladeshi children. One of the customized diets (MDCF-2) showed a significant microbiota shift that promoted high levels of biomarkers and mediators associated with growth, bone formation, brain development, and immune function in malnourished children toward a state similar to the microbiota communities present in age-matched healthy community children.61,62 The sustainability of the improved gut microbiota maturity in the long term remains the next important question that needs to be established through rigorous clinical studies incorporating individualized information. In line with that notion, Chen et al63 recently published the results of a 3-month efficacy trial evaluating the effects of the newly identified MDCF-2 against a standard supplementary food on measures of growth on a larger cohort of children (n = 124) experiencing moderate acute malnutrition for 3 months. The study outcome reinforced the earlier observations that MDCF-2 has promising metabolic benefits by stimulating child growth and brain development. Importantly, these improvements could be sustained 1 month following cessation of the dietary intervention.63 Moving forward, the exact mechanisms of how MDCF-2 improves ponderal growth in malnourished children are required. Further, largely powered intervention trials with MDCF-2 in different locations, as well as longer monitoring periods on growth rate and cognition after cessation of interventions, are clearly warranted to assess the replicability and the long-lived effects of MDCF-2.63,64 Notwithstanding, these findings, along with ongoing efforts, not only emphasize the interplay between microbiota development and healthy growth of a child, but also demonstrate the importance of choosing the correct nutritional ingredients to repair and improve the perturbed guts of undernourished children.

Gut Microbiota In Overnutrition

On the other end of the caloric quantum, overnutrition is the excessive intake of food leading to adverse health events. Obesity is now considered one such adverse health event that is rising globally at an alarming rate. A primary driving force for obesity is adoption of a Western lifestyle, which is characterized by increased consumption of fat, simple carbohydrates, and sugar, accompanied by decreased physical activity. The obese individual is predisposed to a wide array of chronic diseases, not limited to diabetes, heart diseases, and some cancer types. Numerous studies conducted in the past decade have demonstrated that the gut microbiota may be a crucial intermediary connecting diet and obesity, yet the pathological molecular processes remain poorly defined.65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70 Although Wostmann et al71 observed that 30% more calories were required by germ-free mice to maintain their body mass than conventionally raised counterparts, the first suggestion that the gut microbiota makes appreciable contributions to obesity was reported 2 decades later. A series of seminal studies from Jeffrey Gordon’s team demonstrated that (1) when germ-free mice were colonized with microbiota they had a 47% increase in body fat within 2 weeks72; (2) in a genetic mouse model of hyperphagia-induced obesity, these mice had a distinct microbiota composition compared with their lean counterparts despite being fed the same diet73; and (3) the obese mouse or human phenotype could be transferred to germ-free mice.74,75 Together, these findings provided early evidence that the gut microbiota is different in obese mice and humans compared with lean counterparts, and that obesity could potentially be transferred via the gut microbiota.

Many studies have supported the connection between a high ratio of Firmicutes to Bacteroides and obesity,76, 77, 78, 79, 80 yet contrary observations have also been reported, particularly in humans.81, 82, 83, 84, 85 The lack of consistency raises several important questions regarding the role of environmental factors including diet, lifestyle, and host genetics in heterogeneous populations. Further, interstudy variations and the absence of a standardized definition of the obese phenotype can confound data analysis.86 Of note, a recent publication provided evidence that the differential gut microbiota phenotypes of obesity correlate with race and ethnicity, or its associated determinants including dietary components or socioeconomic status.87 Thus, this study may potentially explain some of the discrepancies reported on changes in microbiota composition and obesity, and highlights that individual circumstances and physiology are important driving forces in understanding how a given diet will impact one’s microbiome. Alternatively, it could be possible that taxonomic composition from 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequence analyses insufficiently capture the complexity of the microbiota relationship in obesity. Perhaps more insights may be obtained by examining a core set or clusters of microbial genes in the microbiome and on metabolites produced that are altered or overrepresented in obese individuals. At the species level, the abundance of SCFA producers such as Eubacterium ventriosum and Roseburia intestinalis have been shown to correlate with obesity,88 whereas Oscillospira spp. and Akkermansia muciniphila are leanness-associated taxa89,90 deficient in obese individuals. Recently, daily oral administration of A. muciniphila was studied in a double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. Here, the study investigators found that in overweight and obese, insulin-resistant volunteers, the A. muciniphila–treated group had improved insulin sensitivity and decreased total cholesterol compared with the placebo group.91 Another metagenome-wide association study showed significantly decreased proportions of Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron, a glutamate-fermenting commensal in obese individuals and negatively correlate with serum glutamate levels.92 Furthermore, B. thetaiotaomicron treatment in mice protected against adiposity, pointing to another possible future microbiota-mediated therapeutic avenue for obesity treatment.

Several interconnecting mechanisms implicating the gut microbiota and its associated loss of richness in obesity have been proposed. The colonic fermentation and SCFA production in regulation of gut hormones and influencing energy expenditure is well-recognized.93 Notably, gut microbial-derived SCFAs bind to G protein–coupled receptors GPR41 and GPR43 to regulate energy expenditure.94 SCFAs can also induce lipogenesis through the activation of ChREBP (carbohydrate responsive element-binding protein) and SREBP1 (sterol regulatory element binding transcription factor 1). Separately, the gut microbiota has been shown to decrease liver fatty acid oxidation by suppressing AMPK (adenosine monophosphate kinase) consequently resulting in increased fat storage.95 Mouse and human studies have also found that gut microbiota are involved in dietary lipid digestion and host absorption of lipids either directly96,97 or by altering host gene expression particularly in the small bowel.98 Gut microbiota has also been demonstrated to provoke obesity-associated inflammation via “leakage” of bacterial products such as lipopolysaccharides into systemic circulation which interact with Toll-like receptors leading to metabolic endotoxemia.99

Observations from these microbiota-obesity interaction studies indicate that manipulation of the gut microbial ecosystem could offer potential treatment regimen for obesity and possibly diabetes. In this regard, 2 human studies have demonstrated transient improvement in insulin sensitivity after allogenic fecal transplant from lean, metabolically healthy individuals to individuals with metabolic syndrome, even though no concomitant changes in body weight were observed.100,101 More mechanistic studies are needed to demonstrate how the gut microbiota can be manipulated, either by diet alone or synergistically with a diet + probiotic regimen, to potentially prevent the onset of metabolic derangements, and also help manage or reverse existing conditions. It is already well established that a diet and exercise interventions alone can reduce risk and reverse metabolic defects; however, it is possible that the additional knowledge about the gut microbiota’s interaction with these metabolic pathways may offer accelerated or complementary benefit to preexisting approaches. The true benefit, however, will come only with more tailored approaches to the individual’s microbiome, which as we have established, is determined by a constellation of lifestyle and even genetic factors.

Precision And Personalized Nutrition

At this point, it is clear that the gut microbial ecosystem is an important driver of heterogeneity among individuals in response to dietary or lifestyle interventions, and why universal dietary approaches are sometimes ineffective. This concept was exemplified in a recent study by Johnson et al15 using participants’ fecal microbiota and detailed daily dietary intake history for 17 days. The study demonstrated that individuals have highly individualized microbiota responses to various foods, which is dependent on their previous dietary history. In other words, a certain microbiota profile can become “fixed” to a degree if a certain dietary pattern is consistently adhered to for a certain duration of time. This is compatible with the concept that the gut microbiota is largely influenced by a person’s dietary choices, which as noted earlier in this review, can be influenced by many external factors, and the longer a certain diet is consumed the more adapted the microbiota becomes. This is of course malleable, but it is unclear how long it takes to durably shift a “fixed” microbiome to adapt new composition or functions. Therefore, designing personalized diets must take into account person-specific information including age, gender, geographic location, metabolic status, baseline microbiota membership and function, and established dietary preferences. Consistent with that notion, in an earlier study, Zeevi et al17 utilized machine learning algorithms incorporating personalized information to demonstrate that the gut microbiota can be used to predict individualized glycemic responses to the same administered foods. This study was groundbreaking in that it called to task the currently acceptable dietary models that focus only on caloric density or glycemic index in determining whether a food item is healthy or not, and now brought in a new variable: the gut microbiome. Further, the algorithm was able to design tailored diets that successfully lowered the postprandial glycemic responses for each participant based on their prior tests on different types of foods. These responses were also validated in a follow-up trial with a different population.102 Similarly, a short-term randomized crossover study in healthy participants that compared the effects of a very specific food component, sourdough bread or white bread consumption, in healthy participants revealed that the glycemic responses to the different bread types were largely person-specific and could markedly be predicted by microbiota features at baseline.103 Such studies not only highlight the individuality of gut microbiomes, but also why one-size-fits-all dietary recommendations are flawed. The most comprehensive study investigating predictors of postprandial responses to diet so far is the PREDICT 1 (Personalized Responses to Dietary Composition Trial 1) trial. Metabolic responses to meals of varying macronutrient content were assessed and the meal compositions were associated with clinical biochemical profiles, continuous glucose monitoring, genetics, microbiome, and lifestyle characteristics in a large-scale human cohort including twin pairs. The differences in interindividual responses could reliably be explained by environmental factors such as diet content, meal timing, and physical activity, rather than by host genetics, underscoring the need to consider personalized nutritional recommendations even in genetically identical twins.104

Collectively, these findings highlight that at the population level people may have similar responses to local diets, but at the individual level, rarely do people respond exactly the same, for example in their glycemic response, to the same foods. Many of these studies point to the gut microbiome as the determinant, or at least an important determinant, in these individualized responses. If that is indeed the case, this completely changes how we need to think about dietary interventions for diabetes, obesity and also undernutrition. Perhaps the first step is to understand the individual’s microbiome composition and their dietary history and preferences before prescribing a particular nutritional regimen. Although the evidence presented are very promising and support this concept, an incomplete understanding of the mechanistic underpinnings of personalized responses to diet, and the exact contribution of the gut microbiota to this complexity, may delay its ultimate translation into clinical practice. It is also inherently difficult to apply personalized dietary approaches at scale. It is also important to note that the majority of evidence so far regarding the gut microbiome’s role in personalized responses to diet comes from gut-resident bacteria, while the potential involvement of other gut-dwelling microorganisms such as parasites, viruses, fungi, phage, and archaea are currently unknown. Equally important are the contributions of microbial metabolites that mediate diet-microbiota signaling in shaping personalized responses. While we would be remiss to not point out these challenges, personalized nutrition based at least in part on gut microbiome profiles and function is a concept that warrants further investigation and support. With more data across human populations, patterns and ultimately applicable protocols will emerge that strike a viable balance between personalized and scalable.

Conclusions

The plasticity of the microbiota makes microbiota-targeted dietary interventions an attractive approach for disease prevention and treatment. However, the effects of diet on the gut microbiota in health and disease have predominantly been drawn from animal studies. More human studies involving large and well-powered cohorts are needed to confirm their relevance and ultimately translation into disease-specific nutrition guidelines, as well as tailored approaches for the general population seeking to improve health. Precision health and nutrition are an important future direction in this regard. The measurement of multiple aspects of individuality including geography, cultural practices, food preference, duration of dietary adherence, medical history, and baseline microbiome composition should be considered when designing microbiota-focused precision nutrition protocols or therapeutic foods. The challenge will be to identify optimal combinations of these variables and this will require transdisciplinary approaches including big data bioinformatics tools and analytical methods to address the issue of the multiple permutations that could exist. Several lines of investigation are already underway in this area and hold great promise for changing future approaches to nutrition through the design of person-specific diets and next-generation diet-derived therapeutics by incorporating a greater understanding of the gut microbiome.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest The authors disclose no conflicts.

Funding Suzanne Devkota was supported by National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grant No. R01DK123446 and Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust Grant No. G-2019PG-CD012.

References

- 1.Rodríguez J.M., Murphy K., Stanton C., Ross R.P., Kober O.I., Juge N., Avershina E., Rudi K., Narbad A., Jenmalm M.C., Marchesi J.R., Collado M.C. The composition of the gut microbiota throughout life, with an emphasis on early life. Microb Ecol Health Dis. 2015;26:26050. doi: 10.3402/mehd.v26.26050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bergström A., Skov T.H., Bahl M.I., Roager H.M., Christensen L.B., Ejlerskov K.T., Mølgaard C., Michaelsen K.F., Licht T.R. Establishment of intestinal microbiota during early life: a longitudinal, explorative study of a large cohort of Danish infants. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80:2889–2900. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00342-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koenig J.E., Spor A., Scalfone N., Fricker A.D., Stombaugh J., Knight R., Angenent L.T., Ley R.E. Succession of microbial consortia in the developing infant gut microbiome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(Suppl 1):4578–4585. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000081107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zmora N., Suez J., Elinav E. You are what you eat: diet, health and the gut microbiota. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16:35–56. doi: 10.1038/s41575-018-0061-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gilbert J.A., Blaser M.J., Caporaso J.G., Jansson J.K., Lynch S.V., Knight R. Current understanding of the human microbiome. Nat Med. 2018;24:392–400. doi: 10.1038/nm.4517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gentile C.L., Weir T.L. The gut microbiota at the intersection of diet and human health. Science. 2018;362:776–780. doi: 10.1126/science.aau5812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yatsunenko T., Rey F.E., Manary M.J., Trehan I., Dominguez-Bello M.G., Contreras M., Magris M., Hidalgo G., Baldassano R.N., Anokhin A.P., Heath A.C., Warner B., Reeder J., Kuczynski J., Caporaso J.G., Lozupone C.A., Lauber C., Clemente J.C., Knights D., Knight R., Gordon J.I. Human gut microbiome viewed across age and geography. Nature. 2012;486:222–227. doi: 10.1038/nature11053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu Y., Wan J., Choe U., Pham Q., Schoene N.W., He Q., Li B., Yu L., Wang T.T.Y. Interactions between food and gut microbiota: impact on human health. Annu Rev Food Sci Technol. 2019;10:389–408. doi: 10.1146/annurev-food-032818-121303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Albenberg L.G., Wu G.D. Diet and the intestinal microbiome: associations, functions, and implications for health and disease. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:1564–1572. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.01.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carmody R.N., Bisanz J.E., Bowen B.P., Maurice C.F., Lyalina S., Louie K.B., Treen D., Chadaideh K.S., Maini Rekdal V., Bess E.N., Spanogiannopoulos P., Ang Q.Y., Bauer K.C., Balon T.W., Pollard K.S., Northen T.R., Turnbaugh P.J. Cooking shapes the structure and function of the gut microbiome. Nat Microbiol. 2019;4:2052–2063. doi: 10.1038/s41564-019-0569-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu G.D., Chen J., Hoffmann C., Bittinger K., Chen Y.-Y., Keilbaugh S.A., Bewtra M., Knights D., Walters W.A., Knight R., Sinha R., Gilroy E., Gupta K., Baldassano R., Nessel L., Li H., Bushman F.D., Lewis J.D. Linking long-term dietary patterns with gut microbial enterotypes. Science. 2011;334:105–108. doi: 10.1126/science.1208344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schnorr S.L., Candela M., Rampelli S., Centanni M., Consolandi C., Basaglia G., Turroni S., Biagi E., Peano C., Severgnini M., Fiori J., Gotti R., De Bellis G., Luiselli D., Brigidi P., Mabulla A., Marlowe F., Henry A.G., Crittenden A.N. Gut microbiome of the Hadza hunter-gatherers. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3654. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sonnenburg E.D., Smits S.A., Tikhonov M., Higginbottom S.K., Wingreen N.S., Sonnenburg J.L. Diet-induced extinction in the gut microbiota compounds over generations. Nature. 2016;529:212–215. doi: 10.1038/nature16504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deehan E.C., Walter J. The fiber gap and the disappearing gut microbiome: implications for human nutrition. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2016;27:239–242. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2016.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson A.J., Vangay P., Al-Ghalith G.A., Hillmann B.M., Ward T.L., Shields-Cutler R.R., Kim A.D., Shmagel A.K., Syed A.N. Personalized Microbiome Class Students, Walter J, Menon R, Koecher K, Knights D. Daily sampling reveals personalized diet-microbiome associations in humans. Cell Host Microbe. 2019;25:789–802.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2019.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.David L.A., Maurice C.F., Carmody R.N., Gootenberg D.B., Button J.E., Wolfe B.E., Ling A.V., Devlin A.S., Varma Y., Fischbach M.A., Biddinger S.B., Dutton R.J., Turnbaugh P.J. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature. 2014;505:559–563. doi: 10.1038/nature12820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zeevi D., Korem T., Zmora N., Israeli D., Rothschild D., Weinberger A., Ben-Yacov O., Lador D., Avnit-Sagi T., Lotan-Pompan M., Suez J., Mahdi J.A., Matot E., Malka G., Kosower N., Rein M., Zilberman-Schapira G., Dohnalová L., Pevsner-Fischer M., Bikovsky R., Halpern Z., Elinav E., Segal E. Personalized nutrition by prediction of glycemic responses. Cell. 2015;163:1079–1094. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Filippo C.D., Cavalieri D., Paola M.D., Ramazzotti M., Poullet J.B., Massart S., Collini S., Pieraccini G., Lionetti P. Impact of diet in shaping gut microbiota revealed by a comparative study in children from Europe and rural Africa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:14691–14696. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005963107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gomez A., Petrzelkova K.J., Burns M.B., Yeoman C.J., Amato K.R., Vlckova K., Modry D., Todd A., Jost Robinson C.A., Remis M.J., Torralba M.G., Morton E., Umaña J.D., Carbonero F., Gaskins H.R., Nelson K.E., Wilson B.A., Stumpf R.M., White B.A., Leigh S.R., Blekhman R. Gut microbiome of coexisting BaAka pygmies and Bantu reflects gradients of traditional subsistence patterns. Cell Rep. 2016;14:2142–2153. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jha A.R., Davenport E.R., Gautam Y., Bhandari D., Tandukar S., Ng K.M., Fragiadakis G.K., Holmes S., Gautam G.P., Leach J., Sherchand J.B., Bustamante C.D., Sonnenburg J.L. Gut microbiome transition across a lifestyle gradient in Himalaya. PLOS Biol. 2018;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2005396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mancabelli L., Milani C., Lugli G.A., Turroni F., Ferrario C., Sinderen D. van, Ventura M. Meta-analysis of the human gut microbiome from urbanized and pre-agricultural populations. Environ Microbiol. 2017;19:1379–1390. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brito I., Yilmaz S., Huang K., Xu L., Jupiter S., Jenkins A., Naisilisili W., Tamminen M., Smillie C., Wortman J., Birren B., Xavier R., Blainey P., Singh A., Gevers D., Alm E. Mobile genes in the human microbiome are structured from global to individual scales. Nature. 2016;535:435–439. doi: 10.1038/nature18927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clemente J.C., Ursell L.K., Parfrey L.W., Knight R. The impact of the gut microbiota on human health: an integrative view. Cell. 2012;148:1258–1270. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Obregon-Tito A.J., Tito R.Y., Metcalf J., Sankaranarayanan K., Clemente J.C., Ursell L.K., Zech Xu Z., Van Treuren W., Knight R., Gaffney P.M., Spicer P., Lawson P., Marin-Reyes L., Trujillo-Villarroel O., Foster M., Guija-Poma E., Troncoso-Corzo L., Warinner C., Ozga A.T., Lewis C.M. Subsistence strategies in traditional societies distinguish gut microbiomes. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6505. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keohane D.M., Ghosh T.S., Jeffery I.B., Molloy M.G., O’Toole P.W., Shanahan F. Microbiome and health implications for ethnic minorities after enforced lifestyle changes. Nat Med. 2020;26:1089–1095. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0963-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fragiadakis G.K., Smits S.A., Sonnenburg E.D., Treuren W.V., Reid G., Knight R., Manjurano A., Changalucha J., Dominguez-Bello M.G., Leach J., Sonnenburg J.L. Links between environment, diet, and the hunter-gatherer microbiome. Gut Microbes. 2019;10:216–227. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2018.1494103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pasolli E., Asnicar F., Manara S., Zolfo M., Karcher N., Armanini F., Beghini F., Manghi P., Tett A., Ghensi P., Collado M.C., Rice B.L., DuLong C., Morgan X.C., Golden C.D., Quince C., Huttenhower C., Segata N. Extensive unexplored human microbiome diversity revealed by over 150,000 genomes from metagenomes spanning age, geography, and lifestyle. Cell. 2019;176:649–662.e20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sonnenburg J.L., Sonnenburg E.D. Vulnerability of the industrialized microbiota. Science. 2019;366 doi: 10.1126/science.aaw9255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rampelli S., Schnorr S.L., Consolandi C., Turroni S., Severgnini M., Peano C., Brigidi P., Crittenden A.N., Henry A.G., Candela M. Metagenome sequencing of the Hadza hunter-gatherer gut microbiota. Curr Biol. 2015;25:1682–1693. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.04.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zupancic M.L., Cantarel B.L., Liu Z., Drabek E.F., Ryan K.A., Cirimotich S., Jones C., Knight R., Walters W.A., Knights D., Mongodin E.F., Horenstein R.B., Mitchell B.D., Steinle N., Snitker S., Shuldiner A.R., Fraser C.M. Analysis of the gut microbiota in the Old Order Amish and its relation to the metabolic syndrome. PLoS One. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Turroni S., Fiori J., Rampelli S., Schnorr S.L., Consolandi C., Barone M., Biagi E., Fanelli F., Mezzullo M., Crittenden A.N., Henry A.G., Brigidi P., Candela M. Fecal metabolome of the Hadza hunter-gatherers: a host-microbiome integrative view. Sci Rep. 2016;6:32826. doi: 10.1038/srep32826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smits S.A., Leach J., Sonnenburg E.D., Gonzalez C.G., Lichtman J.S., Reid G., Knight R., Manjurano A., Changalucha J., Elias J.E., Dominguez-Bello M.G., Sonnenburg J.L. Seasonal cycling in the gut microbiome of the Hadza hunter-gatherers of Tanzania. Science. 2017;357:802–806. doi: 10.1126/science.aan4834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davenport E.R., Mizrahi-Man O., Michelini K., Barreiro L.B., Ober C., Gilad Y. Seasonal variation in human gut microbiome composition. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu W., Zhang J., Wu C., Cai S., Huang W., Chen J., Xi X., Liang Z., Hou Q., Zhou B., Qin N., Zhang H. Unique features of ethnic Mongolian gut microbiome revealed by metagenomic analysis. Sci Rep. 2016;6:34826. doi: 10.1038/srep34826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang J., Guo Z., Lim A.A.Q., Zheng Y., Koh E.Y., Ho D., Qiao J., Huo D., Hou Q., Huang W., Wang L., Javzandulam C., Narangerel C., Jirimutu Menghebilige, Lee Y.-K., Zhang H. Mongolians core gut microbiota and its correlation with seasonal dietary changes. Sci Rep. 2014;4:5001. doi: 10.1038/srep05001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hisada T., Endoh K., Kuriki K. Inter- and intra-individual variations in seasonal and daily stabilities of the human gut microbiota in Japanese. Arch Microbiol. 2015;197:919–934. doi: 10.1007/s00203-015-1125-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koliada A., Moseiko V., Romanenko M., Piven L., Lushchak O., Kryzhanovska N., Guryanov V., Vaiserman A. Seasonal variation in gut microbiota composition: cross-sectional evidence from Ukrainian population. BMC Microbiol. 2020;20:100. doi: 10.1186/s12866-020-01786-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dubois G., Girard C., Lapointe F.-J., Shapiro B.J. The Inuit gut microbiome is dynamic over time and shaped by traditional foods. Microbiome. 2017;5:151. doi: 10.1186/s40168-017-0370-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gómez-Gallego C., García-Mantrana I., Martínez-Costa C., Salminen S., Isolauri E., Collado M.C. The microbiota and malnutrition: impact of nutritional status during early life. Annu Rev Nutr. 2019;39:267–290. doi: 10.1146/annurev-nutr-082117-051716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.World Health Organization Double burden of malnutrition. http://www.who.int/nutrition/double-burden-malnutrition/en/ Available at:

- 41.Million M., Diallo A., Raoult D. Gut microbiota and malnutrition. Microb Pathog. 2017;106:127–138. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2016.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Trehan I., Goldbach H.S., LaGrone L.N., Meuli G.J., Wang R.J., Maleta K.M., Manary M.J. Antibiotics as part of the management of severe acute malnutrition. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:425–435. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1202851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Selber-Hnatiw S., Rukundo B., Ahmadi M., Akoubi H., Al-Bizri H., Aliu A.F., Ambeaghen T.U., Avetisyan L., Bahar I., Baird A., Begum F., Ben Soussan H., Blondeau-Éthier V., Bordaries R., Bramwell H., Briggs A., Bui R., Carnevale M., Chancharoen M., Chevassus T., Choi J.H., Coulombe K., Couvrette F., D’Abreau S., Davies M., Desbiens M.-P., Di Maulo T., Di Paolo S.-A., Do Ponte S., Dos Santos Ribeiro P., Dubuc-Kanary L.-A., Duncan P.K., Dupuis F., El-Nounou S., Eyangos C.N., Ferguson N.K., Flores-Chinchilla N.R., Fotakis T., Gado Oumarou H.D.M., Georgiev M., Ghiassy S., Glibetic N., Grégoire Bouchard J., Hassan T., Huseen I., Ibuna Quilatan M.-F., Iozzo T., Islam S., Jaunky D.B., Jeyasegaram A., Johnston M.-A., Kahler M.R., Kaler K., Kamani C., Karimian Rad H., Konidis E., Konieczny F., Kurianowicz S., Lamothe P., Legros K., Leroux S., Li J., Lozano Rodriguez M.E., Luponio-Yoffe S., Maalouf Y., Mantha J., McCormick M., Mondragon P., Narayana T., Neretin E., Nguyen T.T.T., Niu I., Nkemazem R.B., O’Donovan M., Oueis M., Paquette S., Patel N., Pecsi E., Peters J., Pettorelli A., Poirier C., Pompa V.R., Rajen H., Ralph R.-O., Rosales-Vasquez J., Rubinshtein D., Sakr S., Sebai M.S., Serravalle L., Sidibe F., Sinnathurai A., Soho D., Sundarakrishnan A., Svistkova V., Ugbeye T.E., Vasconcelos M.S., Vincelli M., Voitovich O., Vrabel P., Wang L., Wasfi M., Zha C.Y., Gamberi C. Human gut microbiota: toward an ecology of disease. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:1265. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tidjani Alou M., Million M., Traore S.I., Mouelhi D., Khelaifia S., Bachar D., Caputo A., Delerce J., Brah S., Alhousseini D., Sokhna C., Robert C., Diallo B.A., Diallo A., Parola P., Golden M., Lagier J.-C., Raoult D. Gut bacteria missing in severe acute malnutrition, can we identify potential probiotics by culturomics? Front Microbiol. 2017;8:899. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goyal M.S., Venkatesh S., Milbrandt J., Gordon J.I., Raichle M.E. Feeding the brain and nurturing the mind: Linking nutrition and the gut microbiota to brain development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:14105–14112. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1511465112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ahmed T., Auble D., Berkley J.A., Black R., Ahern P.P., Hossain M., Hsieh A., Ireen S., Arabi M., Gordon J.I. An evolving perspective about the origins of childhood undernutrition and nutritional interventions that includes the gut microbiome. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2014;1332:22–38. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smith M.I., Yatsunenko T., Manary M.J., Trehan I., Mkakosya R., Cheng J., Kau A.L., Rich S.S., Concannon P., Mychaleckyj J.C., Liu J., Houpt E., Li J.V., Holmes E., Nicholson J., Knights D., Ursell L.K., Knight R., Gordon J.I. Gut microbiomes of Malawian twin pairs discordant for kwashiorkor. Science. 2013;339:548–554. doi: 10.1126/science.1229000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gordon J.I., Dewey K.G., Mills D.A., Medzhitov R.M. The human gut microbiota and undernutrition. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:137ps12. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Blanton L.V., Charbonneau M.R., Salih T., Barratt M.J., Venkatesh S., Ilkaveya O., Subramanian S., Manary M.J., Trehan I., Jorgensen J.M., Fan Y.-M., Henrissat B., Leyn S.A., Rodionov D.A., Osterman A.L., Maleta K.M., Newgard C.B., Ashorn P., Dewey K.G., Gordon J.I. Gut bacteria that prevent growth impairments transmitted by microbiota from malnourished children. Science. 2016;351 doi: 10.1126/science.aad3311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pekmez C.T., Dragsted L.O., Brahe L.K. Gut microbiota alterations and dietary modulation in childhood malnutrition – the role of short chain fatty acids. Clin Nutr. 2019;38:615–630. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2018.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Monira S., Nakamura S., Gotoh K., Izutsu K., Watanabe H., Alam N.H., Endtz H.P., Cravioto A., Ali S.I., Nakaya T., Horii T., Iida T., Alam M. Gut microbiota of healthy and malnourished children in Bangladesh. Front Microbiol. 2011;2:228. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ghosh T.S., Gupta S.S., Bhattacharya T., Yadav D., Barik A., Chowdhury A., Das B., Mande S.S., Nair G.B. Gut microbiomes of Indian children of varying nutritional status. PloS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Subramanian S., Huq S., Yatsunenko T., Haque R., Mahfuz M., Alam M.A., Benezra A., DeStefano J., Meier M.F., Muegge B.D., Barratt M.J., VanArendonk L.G., Zhang Q., Province M.A., Petri W.A., Ahmed T., Gordon J.I. Persistent gut microbiota immaturity in malnourished Bangladeshi children. Nature. 2014;510:417–421. doi: 10.1038/nature13421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kau A.L., Planer J.D., Liu J., Rao S., Yatsunenko T., Trehan I., Manary M.J., Liu T.-C., Stappenbeck T.S., Maleta K.M., Ashorn P., Dewey K.G., Houpt E.R., Hsieh C.-S., Gordon J.I. Functional characterization of IgA-targeted bacterial taxa from undernourished Malawian children that produce diet-dependent enteropathy. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa4877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Million M., Tidjani Alou M., Khelaifia S., Bachar D., Lagier J.-C., Dione N., Brah S., Hugon P., Lombard V., Armougom F., Fromonot J., Robert C., Michelle C., Diallo A., Fabre A., Guieu R., Sokhna C., Henrissat B., Parola P., Raoult D. Increased gut redox and depletion of anaerobic and methanogenic prokaryotes in severe acute malnutrition. Sci Rep. 2016;6:26051. doi: 10.1038/srep26051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 56.Pham T.-P.-T., Tidjani Alou M., Bachar D., Levasseur A., Brah S., Alhousseini D., Sokhna C., Diallo A., Wieringa F., Million M., Raoult D. Gut microbiota alteration is characterized by a proteobacteria and fusobacteria bloom in Kwashiorkor and a Bacteroidetes paucity in marasmus. Sci Rep. 2019;9:9084. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-45611-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 57.Kristensen K.H.S., Wiese M., Rytter M.J.H., Özçam M., Hansen L.H., Namusoke H., Friis H., Nielsen D.S. Gut microbiota in children hospitalized with oedematous and non-oedematous severe acute malnutrition in Uganda. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Patnode M.L., Beller Z.W., Han N.D., Cheng J., Peters S.L., Terrapon N., Henrissat B., Le Gall S., Saulnier L., Hayashi D.K., Meynier A., Vinoy S., Giannone R.J., Hettich R.L., Gordon J.I. Interspecies competition impacts targeted manipulation of human gut bacteria by fiber-derived glycans. Cell. 2019;179:59–73.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Barratt M.J., Lebrilla C., Shapiro H.-Y., Gordon J.I. The gut microbiota, food science and human nutrition; a timely marriage. Cell Host Microbe. 2017;22:134–141. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2017.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Blanton L.V., Barratt M.J., Charbonneau M.R., Ahmed T., Gordon J.I. Childhood undernutrition, the gut microbiota, and microbiota-directed therapeutics. Science. 2016;352 doi: 10.1126/science.aad9359. 1533–1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gehrig J.L., Venkatesh S., Chang H.-W., Hibberd M.C., Kung V.L., Cheng J., Chen R.Y., Subramanian S., Cowardin C.A., Meier M.F., O’Donnell D., Talcott M., Spears L.D., Semenkovich C.F., Henrissat B., Giannone R.J., Hettich R.L., Ilkayeva O., Muehlbauer M., Newgard C.B., Sawyer C., Head R.D., Rodionov D.A., Arzamasov A.A., Leyn S.A., Osterman A.L., Hossain M.I., Islam M., Choudhury N., Sarker S.A., Huq S., Mahmud I., Mostafa I., Mahfuz M., Barratt M.J., Ahmed T., Gordon J.I. Effects of microbiota-directed foods in gnotobiotic animals and undernourished children. Science. 2019;365 doi: 10.1126/science.aau4732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Raman A.S., Gehrig J.L., Venkatesh S., Chang H.-W., Hibberd M.C., Subramanian S., Kang G., Bessong P.O., Lima A.A.M., Kosek M.N., Petri W.A., Rodionov D.A., Arzamasov A.A., Leyn S.A., Osterman A.L., Huq S., Mostafa I., Islam M., Mahfuz M., Haque R., Ahmed T., Barratt M.J., Gordon J.I. A sparse covarying unit that describes healthy and impaired human gut microbiota development. Science. 2019;365:eaau4735. doi: 10.1126/science.aau4735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chen R.Y., Mostafa I., Hibberd M.C., Das S., Mahfuz M., Naila N.N., Islam MdM., Huq S., Alam MdA., Zaman M.U., Raman A.S., Webber D., Zhou C., Sundaresan V., Ahsan K., Meier M.F., Barratt M.J., Ahmed T., Gordon J.I. A Microbiota-directed food intervention for undernourished children. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1517–1528. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2023294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Garrett W.S. Microbial nourishment for undernutrition. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1566–1567. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe2104212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gérard C., Vidal H. Impact of gut microbiota on host glycemic control. Front Endocrinol. 2019;10:29. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2019.00029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cuevas-Sierra A., Ramos-Lopez O., Riezu-Boj J.I., Milagro F.I., Martinez J.A. Diet, Gut microbiota, and obesity: links with host genetics and epigenetics and potential applications. Adv Nutr. 2019;10:S17–S30. doi: 10.1093/advances/nmy078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gérard P. Gut microbiome and obesity. How to prove causality? Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14:S354–S356. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201702-117AW. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ng M., Fleming T., Robinson M., Thomson B., Graetz N., Margono C., Mullany E.C., Biryukov S., Abbafati C., Abera S.F., Abraham J.P., Abu-Rmeileh N.M.E., Achoki T., AlBuhairan F.S., Alemu Z.A., Alfonso R., Ali M.K., Ali R., Guzman N.A., Ammar W., Anwari P., Banerjee A., Barquera S., Basu S., Bennett D.A., Bhutta Z., Blore J., Cabral N., Nonato I.C., Chang J.-C., Chowdhury R., Courville K.J., Criqui M.H., Cundiff D.K., Dabhadkar K.C., Dandona L., Davis A., Dayama A., Dharmaratne S.D., Ding E.L., Durrani A.M., Esteghamati A., Farzadfar F., Fay D.F.J., Feigin V.L., Flaxman A., Forouzanfar M.H., Goto A., Green M.A., Gupta R., Hafezi-Nejad N., Hankey G.J., Harewood H.C., Havmoeller R., Hay S., Hernandez L., Husseini A., Idrisov B.T., Ikeda N., Islami F., Jahangir E., Jassal S.K., Jee S.H., Jeffreys M., Jonas J.B., Kabagambe E.K., Khalifa S.E.A.H., Kengne A.P., Khader Y.S., Khang Y.-H., Kim D., Kimokoti R.W., Kinge J.M., Kokubo Y., Kosen S., Kwan G., Lai T., Leinsalu M., Li Y., Liang X., Liu S., Logroscino G., Lotufo P.A., Lu Y., Ma J., Mainoo N.K., Mensah G.A., Merriman T.R., Mokdad A.H., Moschandreas J., Naghavi M., Naheed A., Nand D., Narayan K.M.V., Nelson E.L., Neuhouser M.L., Nisar M.I., Ohkubo T., Oti S.O., Pedroza A., Prabhakaran D., Roy N., Sampson U., Seo H., Sepanlou S.G., Shibuya K., Shiri R., Shiue I., Singh G.M., Singh J.A., Skirbekk V., Stapelberg N.J.C., Sturua L., Sykes B.L., Tobias M., Tran B.X., Trasande L., Toyoshima H., van de Vijver S., Vasankari T.J., Veerman J.L., Velasquez-Melendez G., Vlassov V.V., Vollset S.E., Vos T., Wang C., Wang X., Weiderpass E., Werdecker A., Wright J.L., Yang Y.C., Yatsuya H., Yoon J., Yoon S.-J., Zhao Y., Zhou M., Zhu S., Lopez A.D., Murray C.J.L., Gakidou E. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2014;384:766–781. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Myles I.A. Fast food fever: reviewing the impacts of the Western diet on immunity. Nutr J. 2014;13:61. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-13-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhao L. The gut microbiota and obesity: from correlation to causality. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2013;11:639–647. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wostmann B.S., Larkin C., Moriarty A., Bruckner-Kardoss E. Dietary intake, energy metabolism, and excretory losses of adult male germfree Wistar rats. Lab Anim Sci. 1983;33:46–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bäckhed F., Ding H., Wang T., Hooper L.V., Koh G.Y., Nagy A., Semenkovich C.F., Gordon J.I. The gut microbiota as an environmental factor that regulates fat storage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:15718–15723. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407076101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ley R.E., Bäckhed F., Turnbaugh P., Lozupone C.A., Knight R.D., Gordon J.I. Obesity alters gut microbial ecology. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:11070–11075. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504978102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ridaura V.K., Faith J.J., Rey F.E., Cheng J., Duncan A.E., Kau A.L., Griffin N.W., Lombard V., Henrissat B., Bain J.R., Muehlbauer M.J., Ilkayeva O., Semenkovich C.F., Funai K., Hayashi D.K., Lyle B.J., Martini M.C., Ursell L.K., Clemente J.C., Van Treuren W., Walters W.A., Knight R., Newgard C.B., Heath A.C., Gordon J.I. Gut microbiota from twins discordant for obesity modulate metabolism in mice. Science. 2013;341:1241214. doi: 10.1126/science.1241214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Turnbaugh P.J., Ley R.E., Mahowald M.A., Magrini V., Mardis E.R., Gordon J.I. An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature. 2006;444:1027–1031. doi: 10.1038/nature05414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Riva A., Borgo F., Lassandro C., Verduci E., Morace G., Borghi E., Berry D. Pediatric obesity is associated with an altered gut microbiota and discordant shifts in F irmicutes populations. Environ Microbiol. 2017;19:95–105. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bervoets L., Van Hoorenbeeck K., Kortleven I., Van Noten C., Hens N., Vael C., Goossens H., Desager K.N., Vankerckhoven V. Differences in gut microbiota composition between obese and lean children: a cross-sectional study. Gut Pathog. 2013;5:10. doi: 10.1186/1757-4749-5-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hildebrandt M.A., Hoffmann C., Sherrill-Mix S.A., Keilbaugh S.A., Hamady M., Chen Y.-Y., Knight R., Ahima R.S., Bushman F., Wu G.D. High-fat diet determines the composition of the murine gut microbiome independently of obesity. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1716–1724.e1–2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.08.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Turnbaugh P.J., Hamady M., Yatsunenko T., Cantarel B.L., Duncan A., Ley R.E., Sogin M.L., Jones W.J., Roe B.A., Affourtit J.P., Egholm M., Henrissat B., Heath A.C., Knight R., Gordon J.I. A core gut microbiome in obese and lean twins. Nature. 2009;457:480–484. doi: 10.1038/nature07540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Turnbaugh P.J., Bäckhed F., Fulton L., Gordon J.I. Diet-induced obesity is linked to marked but reversible alterations in the mouse distal gut microbiome. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;3:213–223. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sze M.A., Schloss P.D. Looking for a signal in the noise: revisiting obesity and the microbiome. mBio. 2016;7 doi: 10.1128/mBio.01018-16. 01018-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Walters W.A., Xu Z., Knight R. Meta-analyses of human gut microbes associated with obesity and IBD. FEBS Lett. 2014;588:4223–4233. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.09.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Payne A.N., Chassard C., Zimmermann M., Müller P., Stinca S., Lacroix C. The metabolic activity of gut microbiota in obese children is increased compared with normal-weight children and exhibits more exhaustive substrate utilization. Nutr Diabetes. 2011;1:e12. doi: 10.1038/nutd.2011.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Schwiertz A., Taras D., Schäfer K., Beijer S., Bos N.A., Donus C., Hardt P.D. Microbiota and SCFA in lean and overweight healthy subjects. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18:190–195. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zhang H., DiBaise J.K., Zuccolo A., Kudrna D., Braidotti M., Yu Y., Parameswaran P., Crowell M.D., Wing R., Rittmann B.E., Krajmalnik-Brown R. Human gut microbiota in obesity and after gastric bypass. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:2365–2370. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812600106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Finucane M.M., Sharpton T.J., Laurent T.J., Pollard K.S. A taxonomic signature of obesity in the microbiome? Getting to the guts of the matter. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Stanislawski M.A., Dabelea D., Lange L.A., Wagner B.D., Lozupone C.A. Gut microbiota phenotypes of obesity. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes. 2019;5:18. doi: 10.1038/s41522-019-0091-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tims S., Derom C., Jonkers D.M., Vlietinck R., Saris W.H., Kleerebezem M., de Vos W.M., Zoetendal E.G. Microbiota conservation and BMI signatures in adult monozygotic twins. ISME J. 2013;7:707–717. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2012.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gophna U., Konikoff T., Nielsen H.B. Oscillospira and related bacteria – From metagenomic species to metabolic features. Environ Microbiol. 2017;19:835–841. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Everard A., Belzer C., Geurts L., Ouwerkerk J.P., Druart C., Bindels L.B., Guiot Y., Derrien M., Muccioli G.G., Delzenne N.M., de Vos W.M., Cani P.D. Cross-talk between Akkermansia muciniphila and intestinal epithelium controls diet-induced obesity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:9066–9071. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219451110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Depommier C., Everard A., Druart C., Plovier H., Van Hul M., Vieira-Silva S., Falony G., Raes J., Maiter D., Delzenne N.M., de Barsy M., Loumaye A., Hermans M.P., Thissen J.-P., de Vos W.M., Cani P.D. Supplementation with Akkermansia muciniphila in overweight and obese human volunteers: a proof-of-concept exploratory study. Nat Med. 2019;25:1096–1103. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0495-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Liu R., Hong J., Xu X., Feng Q., Zhang D., Gu Y., Shi J., Zhao S., Liu W., Wang X., Xia H., Liu Z., Cui B., Liang P., Xi L., Jin J., Ying X., Wang X., Zhao X., Li W., Jia H., Lan Z., Li F., Wang R., Sun Y., Yang M., Shen Y., Jie Z., Li J., Chen X., Zhong H., Xie H., Zhang Y., Gu W., Deng X., Shen B., Xu X., Yang H., Xu G., Bi Y., Lai S., Wang J., Qi L., Madsen L., Wang J., Ning G., Kristiansen K., Wang W. Gut microbiome and serum metabolome alterations in obesity and after weight-loss intervention. Nat Med. 2017;23:859–868. doi: 10.1038/nm.4358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Byrne C.S., Chambers E.S., Morrison D.J., Frost G. The role of short chain fatty acids in appetite regulation and energy homeostasis. Int J Obes 2005. 2015;39:1331–1338. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2015.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kimura I., Ozawa K., Inoue D., Imamura T., Kimura K., Maeda T., Terasawa K., Kashihara D., Hirano K., Tani T., Takahashi T., Miyauchi S., Shioi G., Inoue H., Tsujimoto G. The gut microbiota suppresses insulin-mediated fat accumulation via the short-chain fatty acid receptor GPR43. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1829. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.López M. EJE PRIZE 2017: Hypothalamic AMPK: a golden target against obesity? Eur J Endocrinol. 2017;176:R235–R246. doi: 10.1530/EJE-16-0927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wang Y., Kuang Z., Yu X., Ruhn K.A., Kubo M., Hooper L.V. The intestinal microbiota regulates body composition through NFIL3 and the circadian clock. Science. 2017;357:912–916. doi: 10.1126/science.aan0677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Semova I., Carten J.D., Stombaugh J., Mackey L.C., Knight R., Farber S.A., Rawls J.F. Microbiota regulate intestinal absorption and metabolism of fatty acids in the zebrafish. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;12:277–288. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Martinez-Guryn K., Hubert N., Frazier K., Urlass S., Musch M.W., Ojeda P., Pierre J.F., Miyoshi J., Sontag T., Cham C., Reardon C., Leone V., Chang E.B. Small intestine microbiota regulate host digestive and absorptive adaptive responses to dietary lipids. Cell Host Microbe. 2018;23:458–469.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2018.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Cani P.D., Amar J., Iglesias M.A., Poggi M., Knauf C., Bastelica D., Neyrinck A.M., Fava F., Tuohy K.M., Chabo C., Waget A., Delmée E., Cousin B., Sulpice T., Chamontin B., Ferrières J., Tanti J.-F., Gibson G.R., Casteilla L., Delzenne N.M., Alessi M.C., Burcelin R. Metabolic endotoxemia initiates obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2007;56:1761–1772. doi: 10.2337/db06-1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kootte R.S., Levin E., Salojärvi J., Smits L.P., Hartstra A.V., Udayappan S.D., Hermes G., Bouter K.E., Koopen A.M., Holst J.J., Knop F.K., Blaak E.E., Zhao J., Smidt H., Harms A.C., Hankemeijer T., Bergman J.J.G.H.M., Romijn H.A., Schaap F.G., Olde Damink S.W.M., Ackermans M.T., Dallinga-Thie G.M., Zoetendal E., de Vos W.M., Serlie M.J., Stroes E.S.G., Groen A.K., Nieuwdorp M. Improvement of insulin sensitivity after lean donor feces in metabolic syndrome is driven by baseline intestinal microbiota composition. Cell Metab. 2017;26:611–619.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Vrieze A., Van Nood E., Holleman F., Salojärvi J., Kootte R.S., Bartelsman J.F.W.M., Dallinga-Thie G.M., Ackermans M.T., Serlie M.J., Oozeer R., Derrien M., Druesne A., Van Hylckama Vlieg J.E.T., Bloks V.W., Groen A.K., Heilig H.G.H.J., Zoetendal E.G., Stroes E.S., de Vos W.M., Hoekstra J.B.L., Nieuwdorp M. Transfer of intestinal microbiota from lean donors increases insulin sensitivity in individuals with metabolic syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:913–916.e7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Mendes-Soares H., Raveh-Sadka T., Azulay S., Ben-Shlomo Y., Cohen Y., Ofek T., Stevens J., Bachrach D., Kashyap P., Segal L., Nelson H. Model of personalized postprandial glycemic response to food developed for an Israeli cohort predicts responses in MidWestern American individuals. Am J Clin Nutr. 2019;110:63–75. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqz028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Korem T., Zeevi D., Zmora N., Weissbrod O., Bar N., Lotan-Pompan M., Avnit-Sagi T., Kosower N., Malka G., Rein M., Suez J., Goldberg B.Z., Weinberger A., Levy A.A., Elinav E., Segal E. Bread affects clinical parameters and induces gut microbiome-associated personal glycemic responses. Cell Metab. 2017;25:1243–1253.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Berry S.E., Valdes A.M., Drew D.A., Asnicar F., Mazidi M., Wolf J., Capdevila J., Hadjigeorgiou G., Davies R., Al Khatib H., Bonnett C., Ganesh S., Bakker E., Hart D., Mangino M., Merino J., Linenberg I., Wyatt P., Ordovas J.M., Gardner C.D., Delahanty L.M., Chan A.T., Segata N., Franks P.W., Spector T.D. Human postprandial responses to food and potential for precision nutrition. Nat Med. 2020;26:964–973. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0934-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]