Abstract

Aims

This meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled clinical trials assessed the effect of glucose-like peptide-1-receptor agonists (GLP-1RA) on the lipid profile and liver enzymes in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).

Materials and Methods

Randomized placebo-controlled trials investigating GLP-1RA on the lipid profile and liver enzymes in patients with NAFLD were searched in PubMed-Medline, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar databases (from inception to January 2020). A random-effects model and a generic inverse variance method were used for quantitative data synthesis. Sensitivity analysis was conducted. Weighted random-effects meta-regression was performed on potential confounders on lipid profile and liver enzyme concentrations.

Results

12 studies were identified (12 GLP-1RA arms; 677 subjects) that showed treatment with GLP-1RA reduced alanine transaminase (ALT) concentrations (WMD = −10.14, 95%CI = [−15.84, −0.44], P < 0.001), gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) (WMD = −11.53, 95%CI = [−15.21,−7.85], P < 0.001), and alaline phosphatase (ALP) (WMD = −8.29, 95%CI = [−11.34, −5.24], P < 0.001). Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) (WMD = −2.95, 95% CI = [−7.26, 1.37], P=0.18) was unchanged. GLP-1 therapy did not alter triglycerides (TC) (WMD = −7.07, 95%CI = [−17.51, 3.37], P=0.18), total cholesterol (TC) (WMD = −1.17 (−5.25, 2.91), P=0.57), high-density lipoprotein (HDL-C) (WMD = 0.97, 95%CI = [−1.63, 3.58], P=0.46), or low-density lipoprotein (LDL-C) (WMD = −1.67, 95%CI = [−10.08, 6.74], P=0.69) in comparison with controls.

Conclusion

The results of this meta-analysis suggest that GLP-1RA treatment significantly reduces liver enzymes in patients with NAFLD, but the lipid profile is unaffected.

1. Introduction

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is an increasing global public health problem with a worldwide prevalence of NAFLD estimated at approximately 25% [1] and a common cause of chronic liver disease [2], and it is predicted to develop in more than 30% of the US adult population [3]. NAFLD is diagnosed when there is hepatic steatosis in the absence of other causes of hepatic fat [4]. In NAFLD, there is an accumulation of fat in the liver through increased free fatty acid delivery to the liver, increasing triglyceride synthesis, decreasing triglyceride export, and reducing beta-oxidation [5]. Coexisting insulin resistance (IR) in NAFLD enhances lipolysis from the adipose tissue [5]. Currently, there are no approved drug treatments for NAFLD and NASH [6].

Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RA) are a newly introduced class of antidiabetic drugs that improve glycemic control via several molecular pathways [7, 8]. These pharmacologic agents reduce blood glucose via glucose-dependent insulin secretion and by glucagon suppression [8]. In addition, GLP-1RAs have other beneficial effects [9–16] and decrease energy intake and body weight by prolonging gastric emptying and inducing satiety [17]. There is an association between NAFLD and metabolic syndrome that causes DM, dyslipidemia, and obesity suggesting that breaking this cycle by GLP-1 agonists may have therapeutic potential [18], particularly as they may have anti-inflammation activity [19]. The administration of the GLP-1RA liraglutide was suggested to directly reduce liver fibrosis and steatosis in an in vivo study [17] and reduces markers of fibrosis in man [20]. Therefore, GLP-1 receptor analogue therapy may have the potential for the treatment of NAFLD and NASH patients; however, it is unclear from the studies that have been done whether GLP-1 agonists improve the hepatic enzyme and lipid profiles in subjects with NAFLD; therefore, this systematic review and meta-analysis were undertaken.

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

This meta-analysis was conducted according to PRISMA instruction of systematic reviews and meta-analysis [21]. The scientific web-portals such as PubMed, Scopus, Cochrane, Web of Science, Embase, and Scholar were carefully surveyed to extract all relevant literature on the effects of GLP-1 receptor agonists on lipid profile and liver enzymes in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease published until January 2020. The key terms that were applied to finalize the first step of the search strategy to gather target data are shown in Appendix. Additionally, manual searches were performed to find articles that were not indexed in target databases. Only human-based studies were selected from the search strategy, and language restriction was not considered. Two authors (Sh.R. and P.N.) independently surveyed the title and abstracts of the classified papers, extracted relevant data, and applied quality assessments of eligible studies. A third author (R.T.) checked the data and resolved all disagreements.

2.2. Study Selection

The following strategy was utilized to select target papers: randomized clinical trials (parallel or cross-over) that investigated the effect of GLP-1 receptor agonists on the lipid profile and liver enzymes in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, individuals treated with GLP-1 receptor agonists that were compared with placebo-control or other pharmaceutical agents, at least 12 weeks' administration of GLP-1 receptor agonists, papers that contained data for standard deviation (SD), standard error (SE), and confidence interval (CI) parameters in the beginning and the end of each study for both the intervention and control groups.

2.3. Data Extraction

Relevant RCT data were extracted by rechecking the name of first author, country, the number of individuals in the intervention and control groups, the type and doses of GLP-1 receptor agonists, duration of the study, type of the study, and related data for analysis (Table 1). For each study, the values of the mean and SD for lipid profile and liver enzymes were recorded at the beginning and the end of each study using the calculation of the difference between the values before and after the intervention. The following formula was used to calculate the mean difference of SDs:

| (1) |

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies.

| First author | Publication year | Country | Population | Age (control vs. intervention) | Sample size (control vs. intervention) | Type of study | Type of intervention | Control group | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fan et al. | 2013 | China | NAFLD + T2DM + obesity | 54.68 ± 12.14; 51.02 ± 10.10 | 68/49 | RCT | Exenatide | Metformin | 12 weeks |

|

| |||||||||

| Shao et al. | 2014 | China | NAFLD + T2DM | 42 ± 3.2; 43 ± 4.1 | 30/30 | RCT | Exenatide + insulin glargine | Insulin aspart + insulin glargine | 12 weeks |

|

| |||||||||

| Armstrong et al. | 2016 | UK | NASH with/without T2DM | 18–70 | 7/7 | Double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial | Liraglutide | Placebo | 12 weeks |

|

| |||||||||

| Armstrong et al. | 2016 | UK | NASH with/without T2DM | 50 ± 12; 50 ± 11 | 22/23 | Multicentre, double-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial | Liraglutide | Placebo | 48 weeks |

|

| |||||||||

| Khoo et al. | 2017 | Singapore | NAFLD + obesity | 43.7 ± 10.4; 39.0 ± 8.1 | 12/12 | Pilot randomized trial | Liraglutide | Diet + exercise | 26 weeks |

|

| |||||||||

| Wang et al. | 2017 | China | NAFLD + T2DM | 40–78; 41–75 | 49/49 | RCT | Exenatide + metformin | Metformin | 12 weeks |

|

| |||||||||

| Feng et al. | 2017 | China | NAFLD + T2DM | 48.07 ± 12.59; 46.79 ± 9.68 | 29/14.5 | Single-center, open-label, prospective, and randomized trial with parallel design | Liraglutide | Gliclazide | 24 weeks |

|

| |||||||||

| Feng et al. | 2017 | China | NAFLD + T2DM | 46.31 ± 12.32; 46.79 ± 9.68 | 29/14.5 | Single-center, open-label, prospective, and randomized trial with parallel design | Liraglutide | Metformin | 24 weeks |

|

| |||||||||

| Tian et al. | 2018 | China | NAFLD + T2DM | 56.4 ± 8.4; 58.5 ± 7.6 | 75/52 | RCT | Liraglutide | Metformin | 12 weeks |

|

| |||||||||

| Yan et al. | 2019 | China | NAFLD + T2DM | 45.7 ± 9.2; 43.1 ± 9.7 | 27/12 | Randomized, open-label, active-controlled, parallel-group, multicenter trial | Liraglutide | Sitagliptin | 26 weeks |

|

| |||||||||

| Yan et al. | 2019 | China | NAFLD + T2DM | 45.6 ± 7.6; 43.1 ± 9.7 | 24/12 | Randomized, open-label, active-controlled, parallel-group, multicenter trial | Liraglutide | Insulin glargine + metformin | 26 weeks |

|

| |||||||||

| Khoo et al. | 2019 | Singapore | NAFLD | 43.6 ± 9.9; 38.6 ± 8.2 | 15/15 | Prospective randomized pilot study | Liraglutide | Diet + exercise | 26 weeks |

A correlation coefficient of 0.5 was used for r, estimated between 0 and 1 values [22]. The formula (n = the number of individuals in each group) was used to measure SD in each article that reported SE instead of SD.

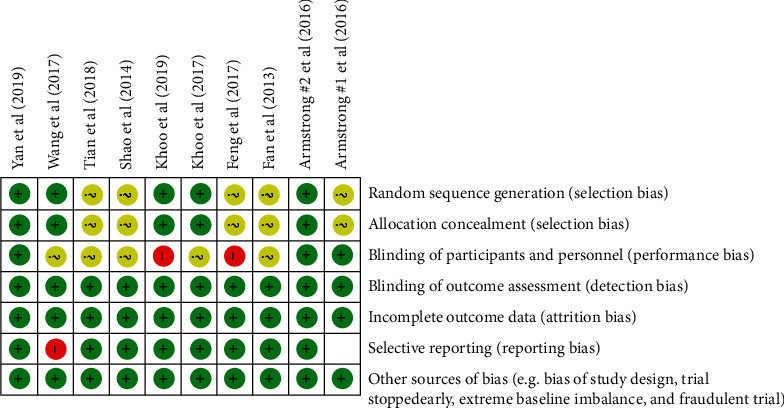

2.4. Quality Assessment

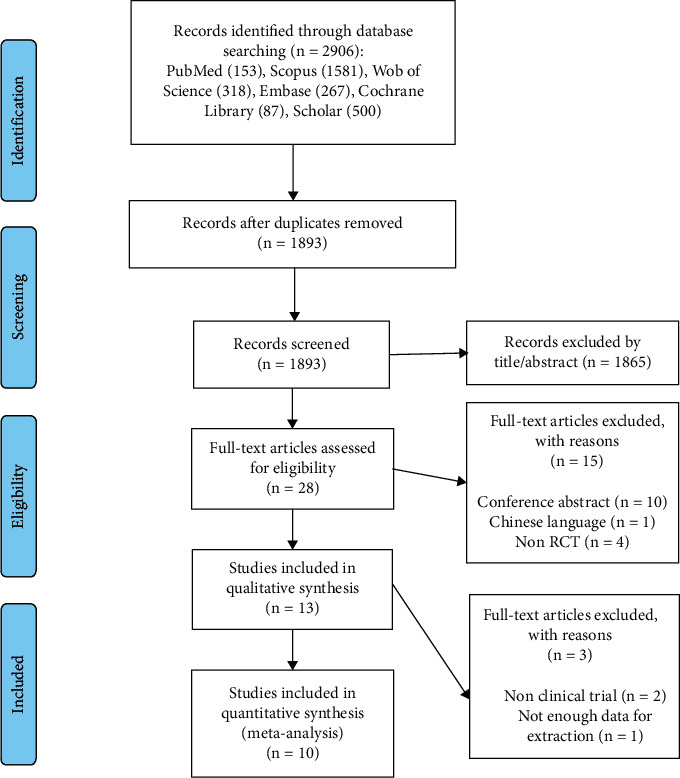

The quality assessment of the included papers in this meta-analysis was conducted based on Cochrane criteria [23]. Accordingly, any source of bias, including selection bias, performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias, and reporting bias, was judged for all included studies (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of study selection method.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

A random-effects model was performed using Stata v.13 (StataCorp. 2021, Stata Statistical Software: release 17; College Station, TX: StataCorp. LLC) to obtain weighted mean difference (WMD) and corresponding 95% CIs. Interstudy heterogeneity was investigated by checking Cochrane's Q test (I2 > 50%, P < 0.1) [24]. In cases with a high amount of statistical heterogeneity, a random-effects meta-regression was applied to find its potential source by confounders such as age, intervention duration, baseline body weight, and body mass index (BMI). Subgroup calculation was conducted according to the age (≥50 years, <50 years), study duration (≤12 weeks vs >12 weeks), BMI (>30, <30), body weight (>85 kg, <85 kg), and type of intervention (GLP-1 vs. GLP-1 plus other treatment) to detect the source of heterogeneity. Overall sensitivity analysis was performed to assess the dependence of pooled results by discarding each study in turn.

Estimation of the value of a correlation coefficient (r) in each outcome was imputed from studies that reported the SD of change for each intervention group in the current meta-analysis. The following formula was used to determine the SD of change calculation among studies that did not provide sufficient information [24]:

| (2) |

where R was for TC: 0.81, TG: 0.45, HDL-c: 0.50, LDL-C: 0.68, AST: 0.64, Alt: 0.62, GGT: 0.60, and ALP: 0.50. We also conducted a sensitivity analysis for outcomes (TG, AST, and ALT) with different values of r; TG (0.26 and 0.63), AST (0.20 and 0.77), and ALT (0.40 and 0.82) to evaluate if the pooled results are sensitive to these levels.

2.6. The Grade Profile

The overall evaluation of the evidence relating to the outcomes was conducted by the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) approach (Table 2) [25].

Table 2.

Summary of findings.

| Absolute effect WMD (95% CI) | No. of studies | Study design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Publication bias | Effect size | GRADE quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effects of GLP-1 on lipid profile | |||||||||

| TG | |||||||||

| −7.07 [−17.51, 3.37] | 9 | RCT | −1 | −1¥ | 0 | −2† | 0 | +1 |

|

| TC | |||||||||

| −1.17 [−5.25, 2.91] | 9 | RCT | −1∗ | 0 | 0 | −1 | 0 | 0 |

|

| HDL-c | |||||||||

| 0.97 [−1.63, 3.58] | 8 | RCT | −1 | 0 | 0 | −1¶ | 0 | 0 |

|

| LDL-c | |||||||||

| −1.67 [−10.08, 6.74] | 8 | RCT | −1 | 0 | 0 | −2 | 0 | 0 |

|

|

| |||||||||

| Effects of GLP-1 on liver enzymes | |||||||||

| AST | |||||||||

| −2.95 [−7.26, 1.37] | 12 | RCT | −1 | 0 | 0 | −2 | 0 | 0 |

(low) (low) |

| ALT | |||||||||

| −10.14 [−15.84, −4.44] | 12 | RCT | −1 | 0 | 0 | −1 | 0 | +1‡ |

(moderate) (moderate) |

The symbols  show the quality of evidence. Abbreviations: WMD, weighted mean difference; CI, confidence interval; RCT, randomized controlled trial; TG, triglycerides; TC, total cholesterol; HDL-c, high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol; LDL-c, low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol, AST, aspartate aminotransfrase; ALT, alanine aminotransfrase. ∗Downgraded one level as the moderate risk of bias. ¶Downgraded one level as the confidence interval was moderate. †Downgraded two levels as the number of studies was <5 and imprecision was considerable. ‡Upgraded one level due to considerable effect size. ¥Downgraded one level as the statistical heterogeneity was >50%.

show the quality of evidence. Abbreviations: WMD, weighted mean difference; CI, confidence interval; RCT, randomized controlled trial; TG, triglycerides; TC, total cholesterol; HDL-c, high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol; LDL-c, low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol, AST, aspartate aminotransfrase; ALT, alanine aminotransfrase. ∗Downgraded one level as the moderate risk of bias. ¶Downgraded one level as the confidence interval was moderate. †Downgraded two levels as the number of studies was <5 and imprecision was considerable. ‡Upgraded one level due to considerable effect size. ¥Downgraded one level as the statistical heterogeneity was >50%.

3. Results

3.1. Search Results and Study Selection

The flowchart explaining the method of selection and references obtained in the databases is shown in Figure 1. In total, 2906 articles were identified in the first phase of the literature search. After removal of duplicate studies (n = 1013), irrelevant studies according to the title and abstracts (n = 1865), different type of intervention (n = 4), conference abstracts (n = 10), and Chinese language (n = 1), thirteen potentially eligible studies were considered for full-text review. Subsequently, three articles were excluded for the following reasons: type of study and insufficient data reporting outcomes. Ultimately, ten studies were entered in the current meta-analysis.

3.2. Data Charachteristics

The main characteristics of the included trials are shown in Table 1. All of the RCTs were published between 2013 and 2019, were conducted in China [26–31], Singapore [32, 33], and UK [34, 35], and lasted 12 to 48 weeks. A total of 677 participants were aged between 18 to 70 years. Seven studies used Liraglutide as an intervention [28, 30–35], and two others [26, 27, 29] used exenatide plus other treatments. The details of the quality assessment are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Details of quality assessment of the included papers.

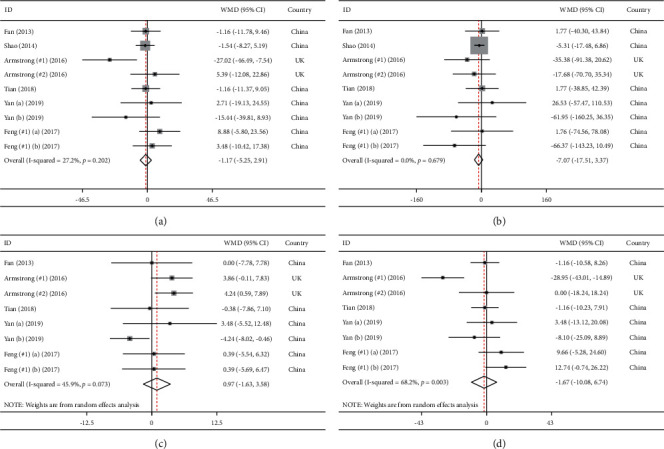

3.3. The Effects of GLP-1 Receptor Agonists on Lipid Profile

The results of the meta-analysis regarding the influence of GLP-1 receptor agonists are shown in Figure 3. Pooled effect sizes indicated that receiving GLP-1 receptor agonists did not cause a statistically significant change in serum TG (WMD = −7.07, 95% CI = [−17.51, 3.37], P=0.18), TC (WMD = −1.17, 95% CI = [−5.25, 2.91], P=0.57), HDL-C (WMD = 0.97, 95% CI = [−1.63, 3.58], P=0.46), and LDL-C (WMD = −1.67, 95% CI = [−10.08, 6.74], P=0.69) in comparison with controls.

Figure 3.

Meta-analysis of weighted mean differences estimates for lipid profiles including (a) total cholesterol, (b) triglycerides, (c) HDL-cholesterol, and (d) LDL-cholesterol in intervention and placebo groups (CI = 95%).

In addition, based on Cochrane's Q test, low degree of between-study heterogeneity was observed in TG (I2 = 0.0%, P=0.6), TC (I2 = 27.2%, P=0.2), and HDL-C (I2 = 45.9%, P < 0.1). Conversely, LDL-C (I2 = 68.2%, P < 0.1) had a high amount of statistical heterogeneity.

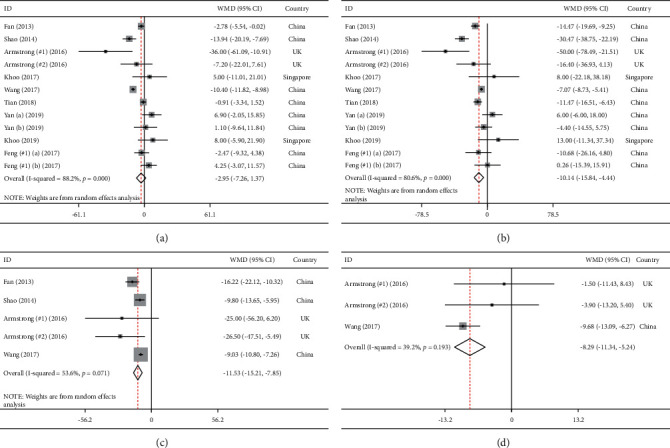

3.4. The Effects of GLP-1 Receptor Agonists on Liver Enzymes

Figure 4 presents the results of meta-analysis for liver enzymes. Treatment with GLP-1 receptor agonists lead to the amelioration of ALT serum concentration (WMD = −10.14, 95% CI = [−15.84, −4.44], P < 0.001), GGT (WMD = −11.53, 95% CI = [−15.21, −7.85], P < 0.001), and ALP (WMD = −8.29, 95% CI = [−11.34, −5.24], P < 0.001). However, serum AST level (WMD = −2.95, 95% CI = [−7.26, 1.37], P=0.18) was not significantly affected following intervention.

Figure 4.

Meta-analysis of weighted mean differences estimates for liver enzymes including (a) aspartate aminotransferase, (b) alanine aminotransferase, (c) gamma-glutamyltransferase, and (d) alkaline phosphatase in intervention and placebo groups (CI = 95%).

Regarding between-study heterogeneity, Cochrane's Q test showed the following results: ALT (I2 = 80.6%, P < 0.1), AST (I2 = 88.2%, P < 0.1), ALP (I2 = 39.2%, P=0.19) and GGT (I2 = 53.6%, P < 0.1).

3.5. Subgroup Analysis

As shown in Table 3, lipid profiles were not changed based on subgroup analysis. Conversely, AST and ALT were significantly affected when we conducted a subanalysis on duration (≤12 weeks). However, serum ALT was significantly changed when subjects received GLP-1 agonists alone, and serum AST was reduced when they received another treatment along with GLP-1 agonists. In addition, the AST level was altered in older participants (≥50 years).

Table 3.

The results of subgroup analysis for serum TC, TG, HDL-C, LDL-C, AST, and ALT.

| Subgroup | Study | WMD (95% CI) | P value | Heterogeneity (I2) | Meta-regression | Test of group differences P > Q_b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TG | |||||||

| Age | ≥50 years old | 3 | −2.76 (−28.35, 22.83) | 0.83 | 0.0 | — | 0.718 |

| <50 years old | 6 | −7.93 (−19.36, 3.5) | 0.17 | 3.7 | |||

| Duration | ≤12 weeks | 4 | −5.47 (−16.48, 5.55) | 0.33 | 0.0 | — | 0.373 |

| >12 weeks | 5 | −21.10 (−17.51, 3.37) | 0.20 | 0.0 | |||

| Baseline BMI | >30 | 4 | −7.31 (−18.72, 4.10) | 0.21 | 0.0 | — | 0.920 |

| <30 | 4 | −5.86 (−31.57, 19.85) | 0.65 | 0.0 | |||

| Baseline body weight | >85 kg | 4 | −7.31 (−18.72, 4.10) | 0.21 | 0.0 | — | 0.920 |

| <85 kg | 4 | −5.86 (−31.57, 19.85) | 0.65 | 0.0 | |||

| Intervention type | GLP-1 agonists | 8 | −11.96 (−32.24, 8.32) | 0.24 | 0.0 | — | 0.582 |

| GLP-1 agonists + other treatment | 1 | −5.31 (−17.48, 6.86) | 0.39 | — | |||

|

| |||||||

| TC | |||||||

| Age | ≥50−years old | 3 | −0.17 (−6.95, 6.61) | 0.96 | 0.0 | — | 0.719 |

| <50 years old | 6 | −1.73 (−6.84, 3.37) | 0.50 | 51.9 | |||

| Duration | ≤12 weeks | 4 | −2.93 (−7.74, 1.88) | 0.23 | 52.1 | — | 0.175 |

| >12 weeks | 5 | 3.35 (−4.34, 11.05) | 0.39 | 0.0 | |||

| Baseline BMI | >30 | 4 | −3.39 (−9.00, 2.21) | 0.23 | 51.0 | — | 0.256 |

| <30 | 4 | 1.33 (−4.61, 7.28) | 0.65 | 0.0 | |||

| Baseline body weight | >85 kg | 4 | −3.39 (−9.00, 2.21) | 0.23 | 51.0 | — | 0.256 |

| <85 kg | 4 | 1.33 (−4.61, 7.28) | 0.65 | 0.0 | |||

| Intervention type | GLP-1 agonists | 8 | −0.95 (−6.08, 4.18) | 0.71 | 36.2 | — | 0.891 |

| GLP-1 agonists + other treatment | 1 | −1.54 (−8.27, 5.19) | — | — | |||

|

| |||||||

| HDL-C | |||||||

| Age | ≥50 years old | 3 | 2.84 (−0.18, 5.86) | 0.06 | 0.0 | — | 0.307 |

| <50 years old | 5 | 0.40 (−3.18, 3.98) | 0.82 | 55.8 | |||

| Duration | ≤12 weeks | 3 | 2.43 (−0.76, 5.63) | 0.13 | 0.0 | — | 0.460 |

| >12 weeks | 5 | 0.56 (−3.21, 4.35) | 0.76 | 61.8 | |||

| Baseline BMI | >30 | 4 | 1.61 (−3.03, 6.26) | 0.49 | 76.1 | — | 0.619 |

| <30 | 4 | 0.16 (−3.17, 3.50) | 0.92 | 0.0 | |||

| Baseline body weight | >85 kg | 4 | 1.61 (−3.03, 6.26) | 0.49 | 76.1 | — | 0.619 |

| <85 kg | 4 | 0.16 (−3.17, 3.50) | 0.92 | 0.0 | |||

|

| |||||||

| LDL-C | |||||||

| Age | ≥50 years old | 3 | −1.02 (−7.17, 5.12) | 0.74 | 0.0 | 0.45 (−1.87, 2.78) | 0.890 |

| <50 years old | 5 | −2.22 (−18.06, 13.60) | 0.78 | 81.8 | |||

| Duration | ≤12 weeks | 3 | −9.48 (−24.70, 5.74) | 0.22 | 83.8 | 0.36 (−0.37, 1.40) | 0.097 |

| >12 weeks | 5 | 4.79 (−2.48, 12.07) | 0.19 | 5.8 | |||

| Baseline BMI | >30 | 4 | −8.96 (−24.42, 6.50) | 0.25 | 71.9 | −3.43 (−7.10, 0.22) | 0.155 |

| <30 | 4 | 3.26 (−3.46, 10.00) | 0.34 | 30.3 | |||

| Baseline body weight | >85 kg | 4 | −8.96 (−24.42, 6.50) | 0.25 | 71.9 | −0.59 (−1.36, 0.18) | |

| <85 kg | 4 | 3.26 (−3.46, 10.00) | 0.34 | 30.3 | |||

|

| |||||||

| AST | |||||||

| Age | ≥50 years old | 4 | −5.04 (−11.24, 1.15) | 0.11 | 95.2 | −0.31 (−1.22, 0.58) | 0.663 |

| <50 years old | 8 | −1.60 (−8.97, 5.77) | 0.67 | 80.4 | |||

| Duration | ≤12 weeks | 5 | −8.07 (−13.86, −2.29) | 0.006 | 94.4 | 0.36 (−0.22, 0.95) | 0.031 |

| >12 weeks | 7 | 1.84 (−1.59, 5.28) | 0.29 | 0.2 | |||

| Intervention type | GLP-1 agonists | 10 | −0.35 (−3.44, 2.75) | 0.82 | 47.6 | — | 0.000 |

| GLP-1 agonists + other treatment | 2 | −10.81 (−13.03, −8.59) | <0.001 | 14.7 | |||

|

| |||||||

| ALT | |||||||

| Age | ≥50 years old | 4 | −10.71 (−15.32, −6.11) | <0.001 | 71.1 | −0.30 (−1.86, 1.26) | 0.997 |

| <50 years old | 8 | −8.47 (−22.18, 5.24) | 0.22 | 88.1 | |||

| Duration | ≤12 weeks | 5 | −18.12 (−27.34, −8.91) | <0.001 | 94.2 | 0.53 (−0.41, 1.48) | 0.003 |

| >12 weeks | 7 | −2.05 (−8.43, 4.31) | 0.52 | 20.7 | |||

| Intervention type | GLP-1 agonists | 10 | −7.69 (−14.20, −1.18) | 0.02 | 64.7 | — | 0.378 |

| GLP-1 agonists + other treatment | 2 | −18.40 (−41.32, 4.52) | 0.11 | 96.6 | |||

3.6. Sensitivity Analysis and Publication Bias

The sensitivity analysis was applied using “one-study-removed” strategy to investigate the influence of each study on the effect size. The results of sensitivity analysis displayed that the pooled results of interested outcomes were not sensitive to each study. Additionaly, we checked triglycerides, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase (TG, AST, and ALT) with different values of r. The significance of the results of TG (r = 0.26: I2 = 0.0%, P=0.22; r = 0.63: I2 = 0.0%, P=0.13), AST (r = 0.20: I2 = 83.7%, P=0.18; r = 0.77: I2 = 99.4%, P=0.05), and ALT (r = 0.40: I2 = 76.3%, P < 0.001; r = 0.82: I2 = 86.5%, P=0.001) was independent of different values of r. Due to the minimum number of studies required for the assessment of publication bias by funnel plot being 10 and for Egger's test being 20, these tools for detection of publication bias would not be meaningful with so few studies and therefore were not performed.

4. Discussion

This meta-analysis showed that the combined available studies, including liraglutide and exenatide, showed an improvement in the liver enzymes of patients with NAFLD but that the lipid profile was unchanged. This suggests that GLP-1 agonists may have utility in the treatment of NAFLD or at least prevention of further progression. Similarly, hepatic histological features in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NAFLD with additional inflammation) were improved in the liraglutide group compared to placebo (hepatocyte ballooning (61% vs. 32%) and steatosis (83% vs. 45%) [34]. Moreover, in a recent meta-analysis of four clinical trials, histological improvement was demonstrated [36]. The mechanism by which liraglutide may improve NAFLD could be through inhibiting the NLRP3 inflammasome and pyroptosis activation through mitophagy [37]. Currently, there is no recognized therapeutic agent for the treatment of NAFLD [38]; however, whilst the studies with these GLP-1 agonists may be encouraging, they are of too short a study duration to know if their effects are maintained or that they have continued clinical therapeutic utility.

Liraglutide is reported to have a cholesterol-lowering effect though the mechanism is unclear [39], and others have shown an improvement in lipids in nondiabetic subjects [20, 40]. In this meta-analysis, there was no effect of GLP-1 agonists on any of the lipid parameters, including TG, TC, HDL-C (where the heterogeneity between studies was low), and LDL-C (where the heterogeneity between studies was high). This suggests that GLP-1 agonists do not have a direct effect on lipid metabolism in NAFLD and that the lipid changes reported in the literature may have been indirectly due to associated weight loss through the satiety effects of the GLP-1 agonists such as liraglutide [17].

The strength of this study was that it focused on randomized clinical trials that would increase its power. This meta-analysis has a number of limitations. Firstly, the effects of GLP-1 therapy on liver enzymes and the lipid profile in NAFLD were not the primary aim of the clinical trials and the studies were not powered for this. Secondly, there were only 12 trials with relatively few subjects available to be analyzed, giving a modest though robust number of subjects to undertake the analysis. The meta-analysis was also limited in that only two studies were with exenatide and the remainder was with liraglutide and no studies were available for the newer GLP-1 agonists such as semaglutide. Since GLP-1 agonists have differing structures and potencies, their effects on liver enzymes are also likely to be different [41].

5. Conclusion

The results of this meta-analysis suggest that GLP-1 agonist treatment significantly reduces the liver enzymes ALT, GGT, and ALP, though AST was no different in patients with NAFLD; however, the lipid profile is unaffected.

Appendix

Search String Employed for the Systematic Review

(INDEXTERMS (“GLP-1 analog” OR “glucagon-like peptide-1 analog” OR “GLP-1 receptor agonist” OR “glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist” OR “glp-1 receptor agonists” OR “glp1 receptor agonist” OR “glucagon-like” OR exenatide OR lixisenatide OR eperzan OR tanzeum OR albiglutide OR dulaglutide OR liraglutide OR semaglutide OR taspoglutide OR tanzeum OR trulicity OR byetta OR bydureon OR victoza OR adlyxin OR ozemoic OR saxenda OR bydureon OR “ITCA 650” OR “Exendin-4” OR “Exendin 4” OR byetta OR adlyxin OR lyxumia OR “rGLP-1 protein” OR ozempic) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“GLP-1 analog” OR “glucagon-like peptide-1 analog” OR “GLP-1 receptor agonist” OR “glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist” OR “glp-1 receptor agonists” OR “glp1 receptor agonist” OR “glucagon-like” OR exenatide OR lixisenatide OR eperzan OR tanzeum OR albiglutide OR dulaglutide OR liraglutide OR semaglutide OR taspoglutide OR tanzeum OR trulicity OR byetta OR bydureon OR victoza OR adlyxin OR ozemoic OR saxenda OR bydureon OR “ITCA 650” OR “Exendin-4” OR “Exendin 4” OR byetta OR adlyxin OR lyxumia OR “rGLP-1 protein” OR ozempic)) AND (INDEXTERMS (NASH OR Liver OR “Fatty Liver” OR steatohepatitis OR “Steatosis of Liver” OR “Visceral Steatosis” OR steatosis OR “Liver Steatosis” OR “Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease” OR “Non alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease” OR “NAFLD” OR “Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease” OR nonalcoholic OR “Non alcoholic” OR “Nonalcoholic Fatty” OR “Non-alcoholic Fatty” OR “Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver” OR “Nonalcoholic Fatty Livers” OR “Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis” OR steatohepatitis OR steatotic) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (NASH OR Liver OR “Fatty Liver” OR steatohepatitis OR “Steatosis of Liver” OR “Visceral Steatosis” OR steatosis OR “Liver Steatosis” OR “Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease” OR “Non alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease” OR “NAFLD” OR “Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease” OR nonalcoholic OR “Non alcoholic” OR “Nonalcoholic Fatty” OR “Non-alcoholic Fatty” OR “Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver” OR “Nonalcoholic Fatty Livers” OR “Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis” OR steatohepatitis OR steatotic)) AND (INDEXTERMS (“randomized clinical trial” OR “Randomized controlled trial” OR “random allocation” OR randomized OR “clinical trial” OR random∗ OR trial OR blind OR “controlled trial” OR “controlled study” OR “randomized trial” OR “clinical study”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“randomized clinical trial” OR “Randomized controlled trial” OR “random allocation” OR randomized OR “clinical trial” OR random∗ OR trial OR blind OR “controlled trial” OR “controlled study” OR “randomized trial” OR “clinical study”)).

Data Availability

There are no raw data associated with this review article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Araújo A. R., Rosso N., Bedogni G., Tiribelli C., Bellentani S. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease/nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: what we need in the future. Liver International . 2018;38:47–51. doi: 10.1111/liv.13643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hagström H., Nasr P., Ekstedt M., et al. Risk for development of severe liver disease in lean patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a long‐term follow‐up study. Hepatology communications . 2018;2(1):48–57. doi: 10.1002/hep4.1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wise J. Pioglitazone seems safe and effective for patients with fatty liver disease and diabetes. BMJ . 2016;353:p. i3435. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i3435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wong V. W.-S., Chan W.-K., Chitturi S., et al. Asia-pacific working party on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease guidelines 2017-part 1: definition, risk factors and assessment. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology . 2018;33(1):70–85. doi: 10.1111/jgh.13857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwenger K. J. P. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Investigating the Impact of Bariatric Care and the Role of Immune Function . Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Younossi Z. M., Loomba R., Rinella M. E., et al. Current and future therapeutic regimens for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology . 2018;68(1):361–371. doi: 10.1002/hep.29724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yaribeygi H., Sathyapalan T., Sahebkar A. Molecular mechanisms by which GLP-1 RA and DPP-4i induce insulin sensitivity. Life Sciences . 2019;234 doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2019.116776.116776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yaribeygi H., Maleki M., Sathyapalan T., Jamialahmadi T., Sahebkar A. Anti-inflammatory potentials of incretin-based therapies used in the management of diabetes. Life Sciences . 2020;241 doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2019.117152.117152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yaribeygi H., Ashrafizadeh M., Henney N. C., Sathyapalan T., Jamialahmadi T., Sahebkar A. Neuromodulatory effects of anti-diabetes medications: a mechanistic review. Pharmacological Research . 2020;152:1096–1186. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2019.104611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Radbakhsh S., Atkin S. L., Simental-Mendia L. E., Sahebkar A. The role of incretins and incretin-based drugs in autoimmune diseases. International Immunopharmacology . 2021;98 doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2021.107845.107845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yaribeygi H., Atkin S. L., Montecucco F., Jamialahmadi T., Sahebkar A. Renoprotective effects of incretin-based therapy in diabetes mellitus. BioMed Research International . 2021;2021:7. doi: 10.1155/2021/8163153.8163153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yaribeygi H., Farrokhi F. R., Abdalla M. A., et al. The effects of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and dipeptydilpeptidase-4 inhibitors on blood pressure and cardiovascular complications in diabetes. Journal of Diabetes Research . 2021;2021:10. doi: 10.1155/2021/6518221.6518221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yaribeygi H., Katsiki N., Butler A. E., Sahebkar A. Effects of antidiabetic drugs on NLRP3 inflammasome activity, with a focus on diabetic kidneys. Drug Discovery Today . 2019;24(1):256–262. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2018.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yaribeygi H., Rashidy-Pour A., Atkin S. L., Jamialahmadi T., Sahebkar A. GLP-1 mimetics and cognition. Life Sciences . 2021;264:p. 118645. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yaribeygi H., Maleki M., Sathyapalan T., Jamialahmadi T., Sahebkar A. Antioxidative potentials of incretin-based medications: a review of molecular mechanisms. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity . 2021;2021:9. doi: 10.1155/2021/9959320.9959320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ranjbar G., Mikhailidis D. P., Sahebkar A. Effects of newer antidiabetic drugs on nonalcoholic fatty liver and steatohepatitis: think out of the box! Metabolism . 2019;101:p. 154001. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2019.154001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ohki T., Isogawa A., Iwamoto M., et al. The effectiveness of liraglutide in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus compared to sitagliptin and pioglitazone. The ScientificWorld Journal . 2012;2012:8. doi: 10.1100/2012/496453.496453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Angelico F., Del Ben M., Conti R., et al. Insulin resistance, the metabolic syndrome, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism . 2005;90(3):1578–1582. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu W., Feng P.-P., He K., Li S.-W., Gong J.-P. Liraglutide protects non-alcoholic fatty liver disease via inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome activation in a mouse model induced by high-fat diet. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications . 2018;505(2):523–529. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.09.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kahal H., Abouda G., Rigby A. S., Coady A. M., Kilpatrick E. S., Atkin S. L. Glucagon-like peptide-1 analogue, liraglutide, improves liver fibrosis markers in obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clinical Endocrinology . 2014;81(4):523–528. doi: 10.1111/cen.12369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D. G. J. A. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses. The PRISMA Statement . 2009;151(4):264–269. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Borenstein M., Hedges L. V., Higgins J. P., Rothstein H. R. Introduction to Meta-Analysis . Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Higgins J. P. T., Altman D. G., Gotzsche P. C., et al. The Cochrane collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ . 2011;343:p. d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Higgins J., Thomas J., Chandler J., et al. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions . London, UK: Cochrane Handbook; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guyatt G. H., Oxman A. D., Vist G. E., et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ . 2008;336(7650):924–926. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.ad. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fan H., Pan Q., Xu Y., Yang X. Exenatide improves type 2 diabetes concomitant with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Arquivos Brasileiros de Endocrinologia & Metabologia . 2013;57(9):702–708. doi: 10.1590/s0004-27302013000900005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shao N., Kuang H. Y., Hao M., Gao X. Y., Lin W. J., Zou W. Benefits of exenatide on obesity and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease with elevated liver enzymes in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes . 2014;30(6):521–529. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.2561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Feng W., Gao C., Bi Y., et al. Randomized trial comparing the effects of gliclazide, liraglutide, and metformin on diabetes with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Journal of Diabetes . 2017;9(8):800–809. doi: 10.1111/1753-0407.12555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang D. J. J. M. U. Effect of exenatide combined with metformin therapy on insulin resistance, liver function and inflammatory response in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus combined with NAFLD. Journal of Hainan Medical University . 2017;23(18):44–47. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tian F., Zheng Z., Zhang D., He S., Shen J. Efficacy of liraglutide in treating type 2 diabetes mellitus complicated with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Bioscience Reports . 2018;38 doi: 10.1042/BSR20181304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yan J., Yao B., Kuang H., et al. Liraglutide, sitagliptin, and insulin glargine added to metformin: the effect on body weight and intrahepatic lipid in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology . 2019;69(6):2414–2426. doi: 10.1002/hep.30320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khoo J., Hsiang J., Taneja R., Law N. M., Ang T. L. Comparative effects of liraglutide 3 mg vs structured lifestyle modification on body weight, liver fat and liver function in obese patients with non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease: a pilot randomized trial. Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism . 2017;19(12):1814–1817. doi: 10.1111/dom.13007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khoo J., Ho M., Kam S., et al. Comparing effects of liraglutide-induced weight loss versus lifestyle modification on liver fat content and plasma acylcarnitine levels in obese adults with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Obesity Facts . 2019;12:p. 61. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Armstrong M. J., Gaunt P., Aithal G. P., et al. Liraglutide safety and efficacy in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (LEAN): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 2 study. The Lancet . 2016;387(10019):679–690. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(15)00803-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Armstrong M. J., Hull D., Guo K., et al. Glucagon-like peptide 1 decreases lipotoxicity in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Journal of Hepatology . 2016;64(2):399–408. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.08.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lv X., Dong Y., Hu L., Lu F., Zhou C., Qin S. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) for the management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): a systematic review. Endocrinology, Diabetes & Metabolism . 2020;3(3) doi: 10.1002/edm2.163.e00163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu X., Hao M., Liu Y., et al. Liraglutide ameliorates non-alcoholic steatohepatitis by inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome and pyroptosis activation via mitophagy. European Journal of Pharmacology . 2019;864 doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2019.172715.172715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sumida Y., Yoneda M., Tokushige K., et al. Antidiabetic therapy in the treatment of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences . 2020;21(6) doi: 10.3390/ijms21061907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aoki K., Kamiyama H., Takihata M., et al. Effect of liraglutide on lipids in patients with type 2 diabetes: a pilot study. Endocrine Journal . 2020;67(9):957–962. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.ej19-0464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kahal H., Aburima A., Ungvari T., et al. The effects of treatment with liraglutide on atherothrombotic risk in obese young women with polycystic ovary syndrome and controls. BMC Endocrine Disorders . 2015;15(1):p. 14. doi: 10.1186/s12902-015-0005-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Capehorn M. S., Catarig A.-M., Furberg J. K., et al. Efficacy and safety of once-weekly semaglutide 1.0 mg vs once-daily liraglutide 1.2 mg as add-on to 1–3 oral antidiabetic drugs in subjects with type 2 diabetes (SUSTAIN 10) Diabetes & Metabolism . 2020;46(2):100–109. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2019.101117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

There are no raw data associated with this review article.