Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to explore the C-X-C chemokines CXCL2 and CXCL10 as potential anti-inflammatory targets for Bacillus endophthalmitis.

Methods

Bacillus endophthalmitis was induced in C57BL/6J, CXCL2−/−, and CXCL10−/− mice. At specific times postinfection, eyes were analyzed for Bacillus, retinal function, and inflammation. The efficacies of intravitreal anti-CXCL2 and anti-CXCL10 with or without gatifloxacin in B. cereus endophthalmitis were also assessed using the same techniques.

Results

Despite similar Bacillus growth in eyes of C57BL/6J, CXCL2−/−, and CXCL10−/− mice, retinal function retention was greater in eyes of CXCL2−/− and CXCL10−/− mice compared to that of C57BL/6J mice. Neutrophil migration into eyes of CXCL2−/− and CXCL10−/− mice was reduced to a greater degree compared to that of eyes of C57BL/6J mice. Infected CXCL2−/− and CXCL10−/− mouse eyes had significantly less inflammation compared to that of C57BL/6J eyes. Retinal structures in infected eyes of CXCL2−/− mice were preserved for a longer time than in CXCL10−/− eyes. Compared to untreated eyes, there was less inflammation and significant retention of retinal function in eyes treated with anti-CXCL2 and anti-CXCL10 with or without gatifloxacin.

Conclusions

For Bacillus endophthalmitis, the absence of CXCL2 or CXCL10 in mice resulted in retained retinal function and less inflammation. The absence of CXCL2 led to a better clinical outcome than the absence of CXCL10. The use of anti-CXCL2 and anti-CXCL10 limited inflammation during B. cereus endophthalmitis. These results highlight the utility of CXCL2 and CXCL10 as potential targets for anti-inflammatory therapy that can be tested in conjunction with antibiotics for improving treating Bacillus endophthalmitis.

Keywords: endophthalmitis, infection, bacteria, chemokines, inflammation

Endophthalmitis is a devastating infection most commonly caused by bacterial entry into the eye.1 Bacteria can be introduced into the globe of the eye after a surgical procedure (postoperative), due to an injury (post-traumatic), or by migration of organisms into the eye from an extraocular site of infection (endogenous).2–4 Irrespective of the etiology of infection, the signs and symptoms of these types of endophthalmitis are comparable, and range from red, inflamed eyes and eyelids to extreme intraocular pain and vision loss. Disease outcomes range from treatable inflammation to fulminant, rapidly progressing, intractable infections. Endophthalmitis is reported to be associated with various organisms, including Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria and fungi. Among all organisms associated with endophthalmitis, 85% of isolates from culture-positive cases were reported to be Gram-positive bacteria.5–7

Bacillus is a Gram‐positive, spore-forming, β‐hemolytic, aerobic rod‐shaped and motile bacterium commonly associated with food poisoning and other gastrointestinal infections. Bacillus strains have also been linked to serious non-gastrointestinal infections as bacteremia, meningitis, endocarditis, wound infections, septicemia, and pneumonia.8–10 Bacillus causes the most severe form of bacterial endophthalmitis and is often linked with devastating clinical consequences.11,12 Contamination of the eye with Bacillus often ends in a rapidly developing infection that is difficult to manage with the available treatment options.13 Compared to other organisms linked with endophthalmitis, Bacillus intraocular infection is very rapid. Within 12 to 48 hours, Bacillus-infected eyes typically lose useful vision and experience significant intraocular damage, frequently leading to removal of the eye.7,12 Due to the extremely fast progression of Bacillus endophthalmitis and threat of vision loss, understanding the underlying events that lead to this devastating outcome may aid in developing better therapeutics.

Several components of the host and bacterium contribute to the pathogenesis of experimental Bacillus endophthalmitis.12,14 The toxicity of Bacillus secreted products, quorum sensing regulation of virulence factors, flagella-directed motility, pili-mediated adhesion, and S-layer-mediated inflammation, all impact the pathogenesis of Bacillus endophthalmitis to various degrees.15–22 From the host's perspective, activation of Toll-like receptors TLR4 and TLR2, but not TLR5, are responsible for rapid intraocular inflammation during infection.23–25 During ocular infection, TLRs interact with microbial ligands, resulting in an acute and rapidly evolving inflammatory response in the eye.24,25 Activation of TLRs 2 and 4 and signaling through downstream adaptor proteins MyD88 and TRIF are critical in the response to Bacillus endophthalmitis.26,27 This signaling induces the expression of mediators that attract inflammatory cells to the infection site, primarily polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs). These inflammatory mediators are often produced in parallel with a deteriorating clinical outcome in other endophthalmitis models and in the human eye infected with Bacillus.28,29

Numerous proinflammatory genes are expressed and mediators are synthesized during experimental Bacillus endophthalmitis.22,28–31 The production of cytokines, including macrophage inflammatory protein 1 alpha (MIP-1α), interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), IL-6, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), and the chemokine KC (C-X-C motif ligand 1 [CXCL1]), have been reported to increase in parallel with blood retinal barrier (BRB) permeability and inflammatory cell influx.22,30–33 To date, TNF-α and CXCL1 have been reported to be important to the immune response to experimental Bacillus endophthalmitis.31,33 We also reported that macrophage inflammatory protein 2-alpha (CXCL2 or MIP2-α) and interferon gamma-induced protein 10 (CXCL10 or IP-10) were highly upregulated during Bacillus endophthalmitis, and several of the aforementioned mediators were blunted when innate activation was blocked or absent.22 CXCL2 and CXCL10 are highly homologous and share comparable functions to CXCL1.34,35

Detecting invading pathogens and clearing them as quickly as possible are the primary functions of the innate inflammatory response.36,37 Bacillus is highly inflammogenic and the host-mediated inflammatory response in the eye is often so robust that it is challenging to control, eventually resulting in significant loss of vision, blindness, or enucleation. Anti-inflammatory therapeutics and their use have not proven to be very effective at improving outcomes in this disease.38–41 Here, we explored the role of the C-X-C chemokines CXCL2 and CXCL10 in experimental Bacillus endophthalmitis. Previously, we reported improved and positive clinical outcomes in CXCL1-deficient mice and mice treated with anti-CXCL1 during Bacillus endophthalmitis.31 Therefore, we tested the hypothesis that the absence or inhibition of CXCL2 or CXCL10 would also reduce the inflammation and infection severity, highlighting these mediators as potential therapeutic targets to treat Bacillus endophthalmitis. Our results suggested that the absence of CXCL2 or CXCL10 delayed overall pathogenesis and significantly minimized disease severity, as did the treatment of infected eyes with anti‐CXCL2 or anti-CXCL10. These results identify CXCL2 and CXCL10 as potential anti‐inflammatory targets for the treatment of Bacillus and possibly other types of endophthalmitis.

Material and Methods

Mice

C57BL/6J (000664) mice and breeding pairs of CXCL2−/− (C57BL/6NJ-Cxcl2em1(IMPC)J/J, 029557) and CXCL10−/− mice (B6.129S4‐Cxcl10tm1adl/J, 006087) were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. CXCL2−/− and CXCL10−/− mice were bred on the C57BL/6J background. All breeders were kept on a 12‐hours on/off light cycle in a barrier facility. Weaned or vendor‐supplied animals were accustomed to housing under biosafety level 2 conditions and were co-housed for at least 2 weeks to equilibrate their microbiota. Mice were used in experiments at 8 to 10 weeks of age. All procedures were conducted according to guidelines and recommendations of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center (OUHSC) IACUC, and the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research.

Isolation of Primary Neutrophils From Mice

Mouse primary neutrophils were isolated from bone marrow of euthanized C57BL/6J, CXCL2−/−, and CXCL10−/− mice by using a neutrophil isolation kit (MACS, Miltenyl Biotech, Gladbach, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Bone marrow from the C57BL/6J, CXCL2−/−, and CXCL10−/− harvested femurs was collected into 3 different 50 mL Falcon tubes containing RPMI media (GIBCO/Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) with 10% FBS (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) using a 10 mL syringe. The bone marrow was centrifuged at 100 g for 10 minutes and washed with wash buffer (PBS, pH 7.2, 0.5% bovine serum albumin [BSA], and 2 mM EDTA). Cells were counted manually using a hemocytometer. Then, 200 µL of wash buffer and 50 µL neutrophil biotin-antibody cocktail were added to the tubes for every 5 × 107 cells. After mixing, cells were incubated for 10 minutes at 4°C. Cells were washed and the pellet resuspended in 400 µL of wash buffer and 100 µL of anti-biotin microbeads. Cells were mixed and incubated at 4°C for 15 minutes. Cells were washed and resuspended to a concentration 108 cells in 500 µL of buffer. For magnetic separation, a MACS column and separator of appropriate size was chosen according to the number of total cells and number of neutrophils. LS columns (Miltenyi Biotech) were placed inside the MACS separator. A 15 mL tube was placed under each LS column and the columns were washed with 3 mL of wash buffer. Once the wash buffer was completely removed, the buffer was discarded and new 15 mL tubes were placed under the columns. The entire sample (500 µL) was loaded onto the column. The columns were washed three times with 3 mL of wash buffer. The washed cells were collected, counted, centrifuged at 100 × g for 10 minutes, and resuspended in RPMI medium.42

Bacterial Phagocytosis Assay

Primary neutrophils from C57BL/6J, CXCL2−/−, and CXCL10−/− mice were used in a gentamicin exclusion assay42 to assess the impact of the absence of CXCL2 and CXCL10 on phagocytosis. Approximately 1 × 105 of cells from each group of mice were incubated at 20 MOI (∼2 × 106) with Bacillus cereus ATCC 14579 for 90 minutes. For each group of mice, one aliquot of cells was washed and then treated with 200 µg/mL gentamicin for 60 minutes to kill any extracellular bacteria. The gentamicin-treated cells were centrifuged, washed to remove residual antibiotic, and lysed with 0.5% Triton X-100. The gentamicin-treated group contained only intracellular bacteria. A second aliquot of cells from each group of mice was centrifuged, washed, and lysed with 0.5% Triton X-100. The second group contained both intra- and extracellular bacteria. Equal numbers of Bacillus cereus (approximately 2 × 106 in 2 mL) were incubated with 200 µg/mL gentamicin for 60 minutes as a control. CFU were enumerated by serial dilution and plating.42

Mice and Intraocular Infection

All in vivo experiments were performed with C57BL/6J, and CXCL2−/−, CXCL10−/− mice on the C57BL/6J background. Mice were housed in the animal facility as described above and were 8 to 10 weeks of age at the time of the experiments. Mice were sedated using a combination of ketamine (85 mg/kg body weight; Ketathesia, Henry Schein Animal Health, Dublin, OH, USA) and xylazine (14 mg/kg body weight; AnaSed, Akorn Inc., Decatur, IL, USA). C57BL/6J and CXCL2−/− or CXCL10−/- male and female mice were infected with 100 CFU Bacillus cereus/0.5 µL BHI into the right eye using a sterile glass capillary needle, as previously described.21,28,43 At various times postinfection, electroretinography was performed prior to euthanasia by CO2 inhalation, and then eyes were harvested for quantitation of viable intraocular bacteria, retinal function, and PMN infiltration, and analysis of ocular architecture by histology, as described below.

Retinal Function Analysis by Electroretinography

Electroretinography (ERG) was used to quantify percent retinal function retained, as previously described.20,21,24,25,28,42 After infection, mice were dark adapted for 6 hours. Mice were then sedated as described above, and pupils were dilated with topical phenylephrine (Akorn, Inc.). Gold wire electrodes were placed onto each cornea. Reference electrodes were attached to the forehead and tail. Eyes were then stimulated by five flashes of white light (1200 cd s/m2) and retinal responses were recorded as A-wave (retinal photoreceptor cell function) and B-wave (Muller cell, bipolar cell, and second order neuronal function) amplitudes for infected eyes and compared with the uninfected eyes of the same animal (Espion E2 software; Diagnosys LLC, Lowell, MA, USA).

Intraocular Bacterial Quantitation

As previously described, harvested eyes from euthanized mice at specific time points were homogenized in 400 µL PBS with sterile 1-mm glass beads (BioSpec Products, Inc., Bartlesville, OK, USA), serially diluted 10-fold in PBS, and plated onto BHI agar plates.20,21,24,25,28,44

Histology

Eyes were harvested from euthanized mice at specific time points and incubated in High Alcoholic Prefer fixative for 30 minutes, and then transferred to 70% ethanol. Paraffin-embedded eyes were sectioned and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E).20,21,25,27,28

Inflammatory Cell Influx

Inflammatory cell influx was assessed by measuring myeloperoxidase concentrations using a sandwich ELISA (Hycult Biotech, Plymouth Meeting, PA, USA), as previously described. At various time points, eyes were harvested, transferred into PBS supplemented with proteinase inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA), and homogenized using 1-mm sterile glass beads (BioSpec Products, Inc.). Uninfected eye homogenates were the negative controls. The lower limit of detection for this assay was 2 ng/mL.24,42

Neutralization of CXCL2 or CXCL10 In Vivo

C57BL/6J mice were anesthetized using isoflurane and intravitreally infected with 100 CFU B. cereus, as described above. At 2 hours postinfection, mice were anesthetized again with isoflurane and randomly parsed into the following treatment groups: anti-CXCL2 monoclonal antibody (anti-CXCL2; 250 ng/0.5 µL anti-CXCL2/MIP-2 IgG, AF-452-NA clone 48415; R&D Systems), anti-CXCL10 monoclonal antibody (anti-CXCL10; 250 ng/0.5 µL anti-CXCL10/IP-10 IgG, clone 134013, MAB466; R&D Systems), 0.5 µL PBS containing 1.25 µg gatifloxacin (GAT; Zymaxid 0.5%; Allergan, Inc., Irvine, CA, USA), 0.5 µL PBS containing 1.25 µg gatifloxacin and 250 ng of anti-CXCL2 (GAT + anti-CXCL2), or 0.5 µL PBS containing 1.25 µg gatifloxacin and 250 ng of anti-CXCL10 (GAT + anti-CXCL10), or isotype control antibody (Isotype; 0.5 µg nonspecific control IgG2A/0.5 µL MAB 006, clone 54447l; R&D Systems). Another group of mice was left untreated to serve as controls.31,45 Bacterial growth, retinal function, and intraocular inflammation were assessed at 10 hours postinfection, as described above.

Results

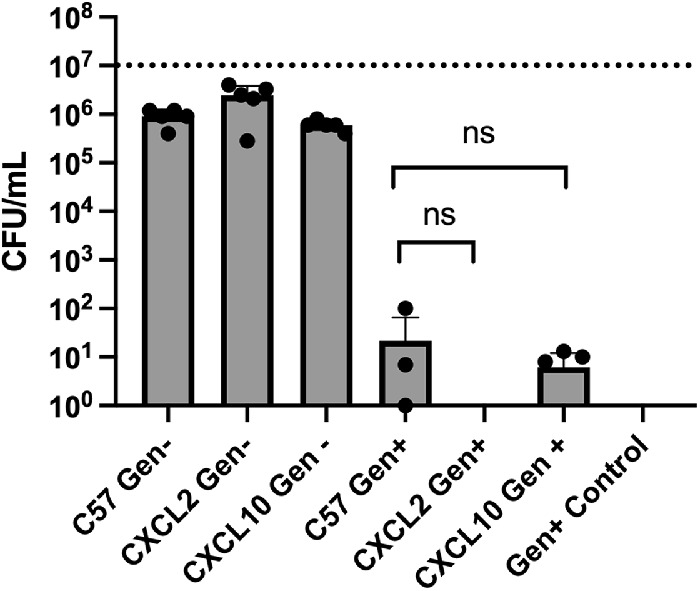

The Absence of CXCL2 or CXCL10 Did Not Affect Bacillus Internalization by Mouse Primary Neutrophils

Chemokines and chemokine receptors are known to regulate neutrophil recruitment. Destruction of microorganisms as well as other foreign particles by phagocytosis is the primary function of neutrophils.46 To determine whether the absence of CXCL2 or CXCL10 altered neutrophil function, a phagocytosis (gentamicin [Gen] exclusion) assay was used (Fig. 1). No differences in internalization of B. cereus were observed among neutrophils isolated from C57BL/6J, CXCL2−/− (P = 0.1667), or CXCL10−/− (P = 0.8254) mice. Incubation with gentamicin recovered no bacteria, indicating that B. cereus were susceptible to the antibiotic (data not shown). Together, these results demonstrated that an absence of CXCL2 or CXCL10 did not interfere with internalization of B. cereus by mouse primary neutrophils.

Figure 1.

The absence of CXCL2 or CXCL10 did not affect Bacillus internalization by mouse primary neutrophils. Primary neutrophils from C57BL/6J, CXCL2−/−, and CXCL10−/− mice were incubated with B. cereus strain ATCC 14579 for 90 minutes. Cells were then treated with gentamicin for 60 minutes to kill external bacteria. Internalization of bacteria by CXCL2−/− and CXCL10−/− neutrophils was not significantly different from that of C57BL/6J neutrophils. C57, C57BL/6J; Gen+, Gentamicin treated; Gen-, Gentamicin untreated. Values represent mean ± SEM of N ≥ 5 for at least two separate experiments; *P < 0.05. Dashed lines represent the initial bacterial inoculum. nsP ≥ 0.05.

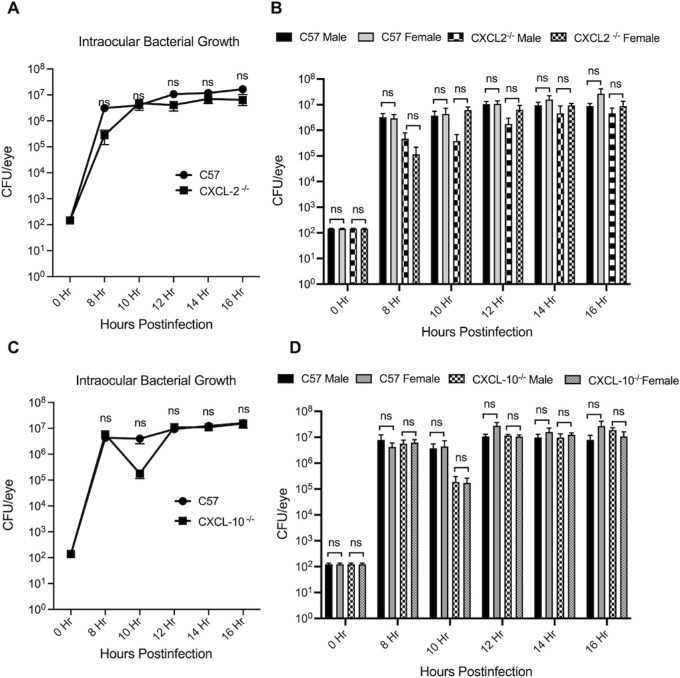

Absence of CXCL2 and CXCL10 Did Not Affect Intraocular Bacillus Growth

Intraocular B. cereus growth in CXCL2−/− and CXCL10−/− male and female mice was compared with that of C57BL/6J male and female mice after infection with 100 CFU B. cereus (Figs. 2A, 2C). B. cereus intraocular numbers in infected eyes of CXCL2−/− male and female mice were comparable to that of infected eyes of C57BL/6J male and female mice at all time points (P ≥ 0.05; Fig. 2B). Intraocular numbers of B. cereus in eyes of CXCL10−/− and C57BL/6J male and female mice were also comparable at all time points (P ≥ 0.05; Fig. 2D). Overall, these results implied that the absence of CXCL2 or CXCL10 in mice did not alter the intraocular growth of B. cereus, suggesting that bacterial growth was independent of CXCL2 or CXCL10 production. Intraocular growth of B. cereus in these mice was also independent of sex at each time point.

Figure 2.

Absence of CXCL2 and CXCL10 did not affect intraocular Bacillus growth. Intraocular B. cereus ATCC 14579 growth was not affected by absence of CXCL2 or CXCL10. Eyes of CXCL2 −/−, CXCL10 −/−, and C57BL/6J (C57) male and female mice were infected with 100 CFU B. cereus. Eyes were harvested at designated timepoints and B. cereus were quantified. No significant differences in B. cereus burden were observed among mouse strains (P ≥ 0.05) (A and C), and no difference was observed in intraocular bacterial burden between males and females (B and D). Values represent means ± SEM of n ≥ 6 eyes at each time point with at least 3 independent experiments. nsP ≥ 0.05.

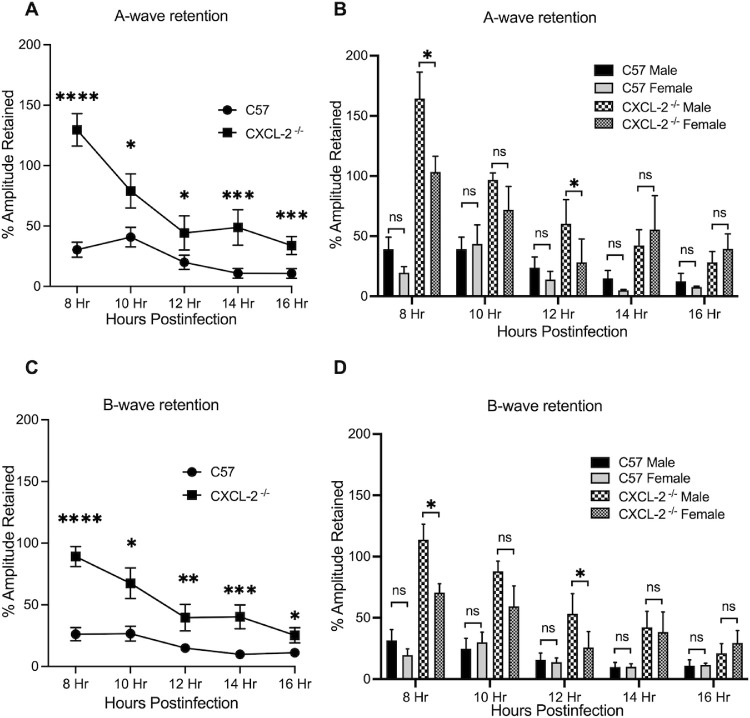

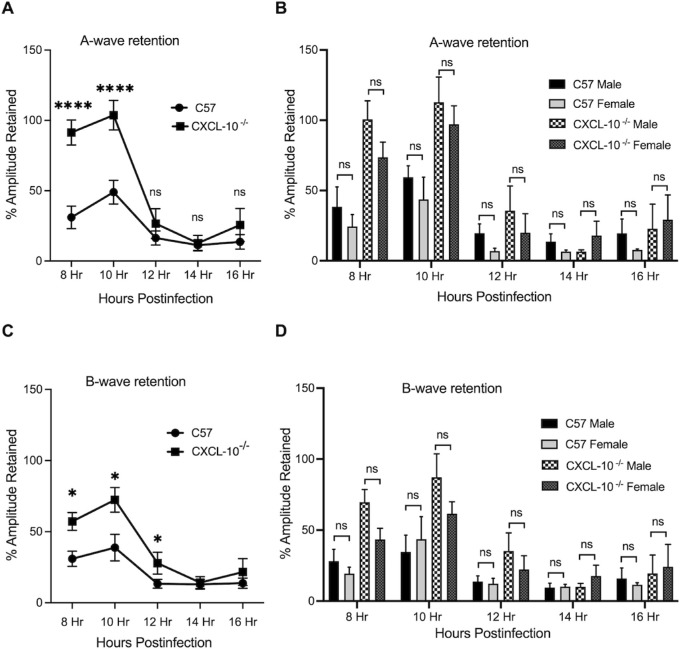

The Absence of CXCL2 or CXCL10 Chemokines Resulted in Improved Retinal Function After B. cereus Infection

Analysis of retinal function of eyes infected with B. cereus is described in Figures 3 and 4. Mice were dark acclimated for 6 hours and ERG was performed at 8, 10, 12, 14, and 16 hours postinfection. A- and B-wave amplitudes in CXCL2−/− mouse eyes infected with B. cereus were significantly retained compared to that of B. cereus-infected C57BL/6J mouse eyes (P ≤ 0.05; see Figs. 3A, 3C). A similar outcome was observed for infected CXCL10−/− mouse eyes, but only until 12 to 14 hours postinfection (P ≤ 0.05; see Figs. 4A, 4C). The function of retinal photoreceptor cells, represented by the A-wave amplitude, decreased rapidly from 8 to 16 hours postinfection in the eyes of C57BL/6J mice infected with B. cereus (see Figs. 3A, 4A). The B-wave amplitude, which is a result of the light-evoked depolarization of the Muller cells, second order neurons, and bipolar cells, was also rapidly reduced from 8 to 16 hours postinfection in B. cereus-infected C57BL/6J eyes (see Figs. 3C, 4C). At 16 hours postinfection, A-wave and B-wave retention in B. cereus-infected C57BL/6J eyes was approximately 13%. Over time, average A-wave and B-wave amplitudes in B. cereus-infected CXCL2−/− and CXCL10−/− eyes decreased by approximately 73% and 66% (Figs. 3A, 3B, 4A, 4A). In CXCL2−/− mice, A-wave and B-wave amplitudes were significantly retained at all time points compared to C57BL/6J mice (P ≤ 0.05; see Fig. 3A). In CXCL10−/− mice, A-wave amplitudes were significantly retained at 8 and 10 hours postinfection (P ≤ 0.05; see Fig. 4A), whereas B-wave function was only significantly retained at 8 (55%), 10 (72%), and 12 (27%) hours postinfection (see Fig. 4C). To determine whether biological sex variability influenced these outcomes, we separated and analyzed data of male and female mice at each time point. A-wave and B-wave retention was significantly higher in male CXCL2−/− mice compared to CXCL2−/− female mice at 8 and 12 hours postinfection only (P ≤ 0.05; see Figs. 3B, 3D). We did not observe any differences in A-wave and B-wave retention between male and female CXCL10−/− mice or C57BL/6J mice (P ≥ 0.05; Figs. 4B, 4D). Together, these results demonstrated that the CXCL2−/− and CXCL10−/− eyes infected with B. cereus retained higher retinal function compared to C57BL/6J eyes, suggesting that absence of CXC chemokines influenced the retention of retinal function during experimental endophthalmitis.

Figure 3.

The absence of CXCL2 resulted in improved retinal function after B. cereus infection. Eyes of CXCL2−/− and C57BL/6J (C57) male and female mice were infected with 100 CFU B. cereus. Retinal function was assessed by ERG at 8, 10, 12, 14, and 16 hours postinfection. In infected CXCL2−/− eyes, retained A‐ and B‐wave responses were significantly greater than retained A‐ and B‐wave responses in infected C57BL/6J eyes (A and C). A sex-related difference in retinal function was only observed at 8 hours (P = 0.0491) and 12 hours (P = 0.0411) time points with CXCL2−/− mice. Values represent means ± SEM of n ≥ 6 eyes at each time point with at least 3 independent experiments. *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, ****P ≤ 0.0001, and nsP ≥ 0.05.

Figure 4.

The absence of CXCL10 resulted in improved retinal function after B. cereus infection. Eyes of CXCL10−/− and C57BL/6J (C57) male and female mice were infected with 100 CFU B. cereus. Retinal function was assessed by ERG at 8, 10, 12, 14, and 16 hours postinfection. Compared to infected C57BL/6J mice eyes, A‐ wave responses were significantly retained at 8 (P < 0.0001) and 10 (P < 0.0001) hours postinfection, whereas B-wave responses were significantly retained at 8 (P = 0.0170), 10 (P = 0.0289), and 12 (P = 0.0423) hours postinfection (A and C). No sex-related differences in retinal function were observed at any time point. Values represent means ± SEM of n ≥ 6 eyes at each time point with at least 3 independent experiments. *P ≤ 0.05, ****P ≤ 0.0001, and nsP ≥ 0.05.

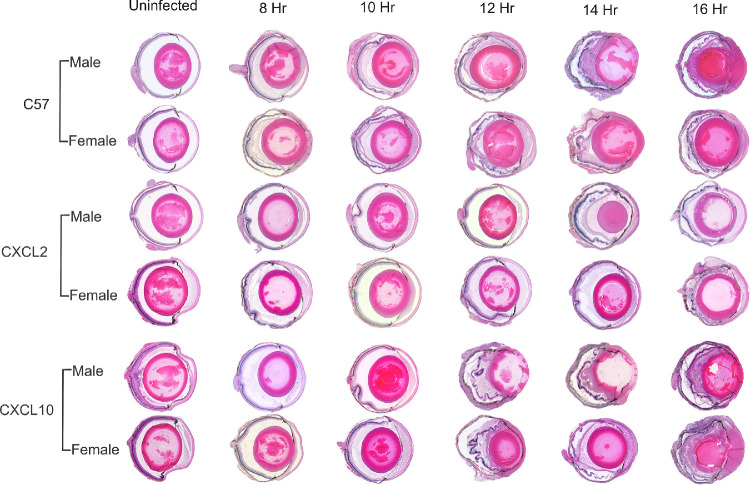

Intraocular Inflammation and Retinal Damage Were Delayed in the Absence of CXCL2 and CXCL10

Histological sections of infected and uninfected eyes of CXCL2−/−, CXCL10−/−, and C57BL/6J male and female mice are depicted in Figure 5. Infected eyes were harvested, fixed, sectioned, and stained with H&E at 8, 10, 12, 14, and 16 hours postinfection. Uninfected CXCL2−/− and CXCL10−/− male/female mice eyes looked morphologically and architecturally similar to eyes of C57BL/6J male/female mice, with no obvious alterations in retinal or corneal cellular morphology and without signs of inflammation. At 8 hours postinfection in C57BL/6J male/female eyes, significant increase of infiltrating cells and fibrin in the posterior segment were detected. In these eyes, anterior chambers were obstructed with fibrin and retinas were also partially detached. On the other hand, ocular architectures were well-preserved in infected CXCL2−/− and CXCL10−/− male/female eyes. These eyes exhibited minimal inflammation and fibrin deposition, distinguishable retinal layers, and intact retinas. At 10 hours postinfection, inflammatory cell infiltration and significant fibrin deposition throughout the vitreous were observed in infected C57BL/6J male/female eyes. Indistinguishable retinal architecture, complete retinal detachments, and highly edematous corneas were observed in these eyes. In stark contrast, retinal layers were distinguishable and retinas were well-preserved in infected CXCL2−/− and CXCL10−/− male/female eyes. At 12, 14, and 16 hours postinfection, retinal architecture was completely lost and inflammation pervaded all ocular structures in infected C57BL/6J and CXCL10−/− male/female eyes. In contrast, retinal layers and architecture remained well-preserved in infected CXCL2−/− male/female eyes and these eyes looked similar to that of infected C57BL/6J eyes at 8 hours postinfection. By 16 hours postinfection, CXCL2−/− male/female eyes were analogous to that of C57BL/6J and CXCL10 male/female eyes, as retinal architecture was completely lost. Overall, compared to C57BL/6J infected eyes during B. cereus endophthalmitis, neutrophil influx and the damage to retinal architecture in infected eyes of CXCL2−/− mice was delayed. For infected CXCL10−/− mice, this delay was observed for a shorter period of time. In contrast to what was observed in wild type mice, ocular architecture was preserved for a longer period of time in the eyes of infected CXCL2−/− mice than in CXCL10−/− mice during B. cereus infection, supporting the contribution of both chemokines to inflammation and overall endophthalmitis pathogenesis.

Figure 5.

Retinal damage and intraocular inflammation were delayed in the absence of CXCL2 and CXCL10. Eyes of CXCL2−/−, CXCL10−/−, and C57BL/6J (C57) male/female mice were infected with 100 CFU B. cereus. Uninfected and infected globes were harvested at 8, 10, 12, 14, and 16 hours postinfection and processed for H&E staining. Uninfected C57, CXCL2−/−, and CXCL10−/− male and female mice were not inflamed, and were architecturally and morphologically similar. At 8 hours postinfection, fibrin deposition was observed in the anterior chamber of all eyes. At 8 and 10 hours postinfection, infected eyes of C57 male/female mice were similarly inflamed, with inflammatory cells in the posterior segment. At 12, 14, and 16 hours postinfection, infected eyes of C57 and CXCL10−/− male/female mice showed retinal detachment and dissolution of retinal layers. In contrast, infected eyes of CXCL2−/− male/female mice had minimal inflammation and intact retinal layers at the same time points. Sections are representative of 3 eyes per time point with at least 3 independent experiments. Original magnification, × 10.

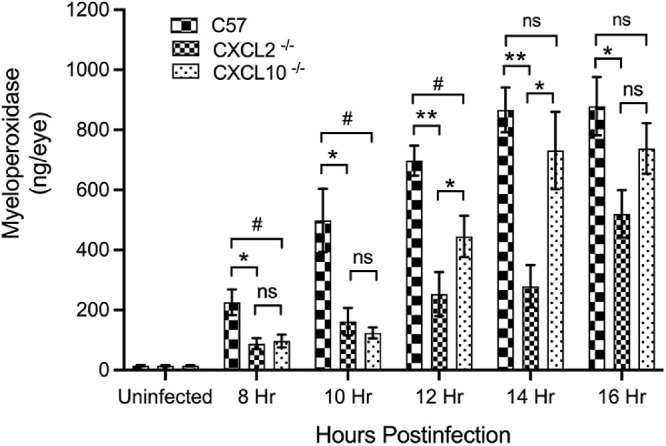

Absence of CXCL2 and CXCL10 Reduces Intraocular Inflammation During Experimental Bacillus Endophthalmitis

We assessed the levels of inflammatory cell influx in C57BL/6J, CXCL2−/−, and CXCL10−/− eyes infected with B. cereus (see Fig. 6). PMNs are the primary infiltrating immune cells in Bacillus endophthalmitis. The presence of myeloperoxidase (MPO) is an indicator of the extent of PMN infiltration. Infected eyes were harvested at 8, 10, 12, 14, and 16 hours postinfection and PMN infiltration was assessed by measuring MPO concentrations in eye homogenates by ELISA. MPO levels in B. cereus-infected CXCL2−/− eyes were significantly less (P ≤ 0.05) compared to that of B. cereus-infected C57BL/6J eyes at all time points. At all time points, the mean MPO concentrations were reduced 66% in infected CXCL2−/− eyes relative to C57BL/6J eyes. However, in infected CXCL10−/− eyes, MPO concentrations were only significantly reduced (P ≤ 0.05) at 8, 10, and 12 hours postinfection. No differences were found in MPO concentration between C57BL/6J and CXCL10−/− eyes at 14 and 16 hours postinfection. At all time points, the mean MPO concentrations were 41% less in CXCL10−/− eyes compared to that of infected C57BL/6J eyes. Compared to CXCL10−/− eyes, MPO concentrations in CXCL2−/− eyes were significantly less (P ≤ 0.05) at 12 (49%) and 14 (60%) hours postinfection. These findings indicated a significant delay in PMN infiltration in infected eyes of CXCL2−/− mice. Although there was an initial delay, eventually, MPO concentrations of infected CXCL10−/− eyes reached that of infected C57BL/6J eyes. Overall, these results further support our findings of less ocular pathology and less retinal function loss in CXCL2−/− and CXCL10−/− eyes infected with B. cereus, strongly suggesting that CXC chemokines play a significant role in the response to B. cereus intraocular infection.

Figure 6.

Absence of CXCL2 and CXCL10 resulted in reduced intraocular inflammation during experimental Bacillus endophthalmitis. MPO concentrations were significantly reduced in the absence of CXCL2 and CXCL10. C57BL/6J (C57), CXCL2−/−, and CXCL10−/− mouse eyes were injected with 100 CFU B. cereus. At 8, 10, 12, 14, and 16 hours postinfection, infected eyes were harvested and infiltration of PMN was assessed by quantifying MPO in whole eyes by sandwich ELISA. At 8, 10, and 12 hours postinfection, MPO levels were significantly reduced (P ≤ 0.05) in CXCL2−/− and CXCL10−/− eyes compared to that of C57 eyes. At 14 and 16 hours postinfection, MPO levels were significantly reduced in CXCL2−/− eyes compared to that of C57 eyes. No difference in MPO levels between CXCL10 and C57 were found at these time points. Compared to CXCL10−/−, CXCL2−/− eyes had reduced levels of MPO at 12 and 14 hours postinfection. Values represent means ± SEM for n ≥ 5 eyes per group per time point with at least 3 independent experiments. *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, and nsP ≥ 0.05.

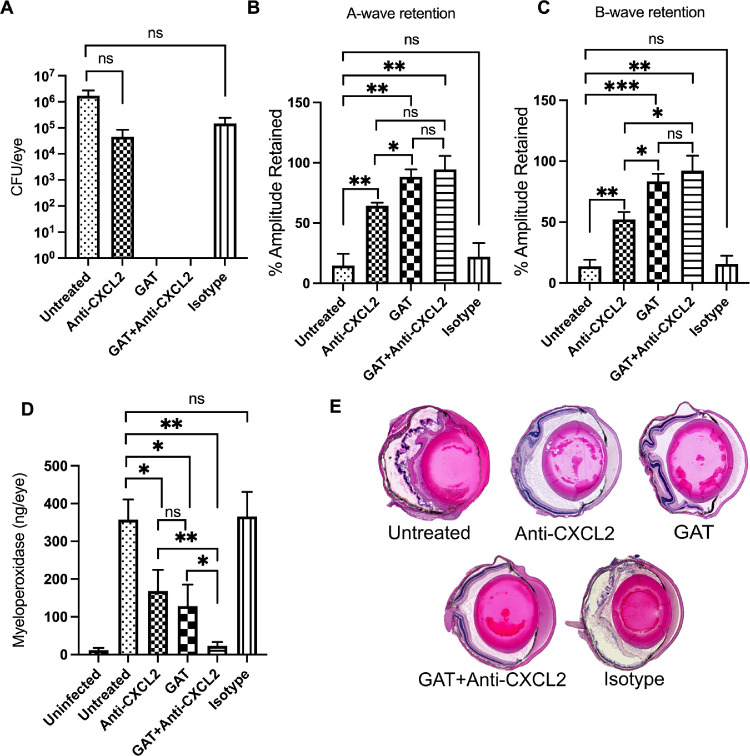

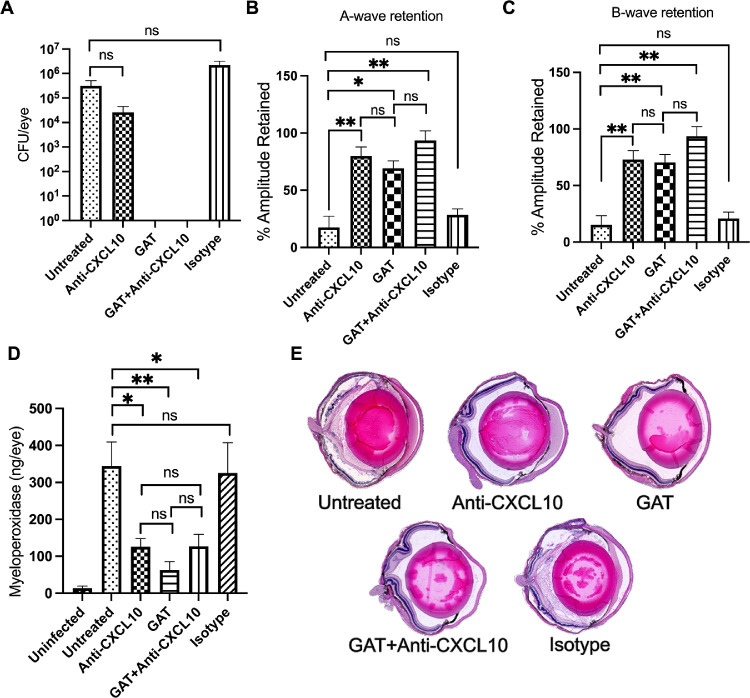

Treatment With Anti-CXCL2 or Anti-CXCL10 Resulted in Better Retinal Function and Reduced Intraocular Inflammation

Because the absence of CXCL2 or CXCL10 in mice resulted in improved retinal function and resulted in reduced inflammation and inflammation-associated damage to the retina, we investigated the impact of CXCL2 and CXCL10 neutralization on disease severity. C57BL/6J mice were divided into five experimental groups. All groups were infected with B. cereus. At 2 hours postinfection, groups of infected eyes were treated with anti-CXCL2 or anti-CXCL10 antibody with or without GAT, or with nonspecific isotype IgG2A (isotype control). One group was left untreated to serve as controls. At 10 hours postinfection, eyes were analyzed for bacterial counts, inflammation, and retinal function (Figs. 7, 8). GAT treatment completely sterilized the infected eyes in both CXCL2 and CXCL10 experimental groups. There were less B. cereus in the groups treated with anti-CXCL2 or anti-CXCL10 alone, but the differences were not significant (P ≥ 0.05; see Figs. 7A, 8A). The average A- and B-wave retention in both untreated and isotype treated experimental groups were approximately 14.5% (see Figs. 7B, 7C, 8B, 8C). Retention of A-wave and B-wave function was nearly 58% in infected eyes treated with anti-CXCL2 antibody alone (see Figs. 7B, 7C). A-wave and B-wave retention was approximately 85% when the eyes were treated with GAT alone (see Figs. 7B, 7C). In contrast, A-wave and B-wave retention was approximately 93% when infected eyes were treated with both GAT and anti-CXCL2 antibody (see Figs. 7B, 7C). Retinal function retention in these three groups was significantly higher than that of control eyes (P ≤ 0.05; see Figs. 7B, 7C). Similarly, in the anti-CXCL10 experimental groups, A-wave and B-wave retention in eyes treated with anti-CXCL10 alone, GAT alone, or GAT + anti-CXCL10-treated eyes was approximately 76%, 69%, and 94%, respectively, and were significantly higher than that of the control eyes (P ≤ 0.05; see Figs. 8B, 8C).

Figure 7.

Treatment with anti-CXCL2 resulted in better retinal function and reduced intraocular inflammation. Treatment with anti‐CXCL2 antibody alone, or with or without gatifloxacin (GAT) arrests intraocular inflammation and protects retinal function. C57BL/6J mice were intravitreally injected with 100 CFU B. cereus. At 2 hours postinfection, groups of infected eyes were treated with 250 ng/0.5 µL anti-CXCL2, 1.25 ug/0.5 µL GAT, 0.5 µL PBS containing 250 ng anti-CXCL2 and 1.25 µg GAT, and 0.5 µg/0.5 µL nonspecific isotype IgG2A (Isotype). All eyes were analyzed at 10 hours postinfection. (A) Gatifloxacin sterilized the eye in both GAT alone and GAT + anti-CXCL2 treated eyes. No differences in bacterial counts were detected between untreated and anti-CXCL2 (P = 0.1905) or isotype-treated (P = 0.5152) eyes. (B) Retained A-wave function was significantly greater in anti-CXCL2 alone (P = 0.0087), GAT alone (P = 0.0013), and GAT + anti-CXCL2 (P = 0.0027) treated eyes compared to untreated eyes. (C) Compared to untreated eyes, B-wave function was significantly retained in anti-CXCL2 alone (P = 0.0047), GAT alone (P = 0.0003), and GAT + anti-CXCL2 (P = 0.0012) treated eyes. No differences in A- or B-wave retention was detected between untreated and isotype treated eyes. (D) MPO concentrations in infected eyes of mice treated with anti‐CXCL2 with or without antibiotics were significantly less than in untreated eyes (P ≤ 0.01). (E) Histology analysis showed that eyes of untreated and isotype‐treated mice were similar in inflammation severity and the loss of complete retinal architecture. In contrast, there was mild inflammation and undamaged retinal layers in infected eyes treated with either anti‐CXCL2 alone, GAT alone, and GAT + anti-CXCL2. Original magnification, × 10. Values represent means ± SEM for n ≥ 5 eyes per group per time point with at least 3 independent experiments. *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, and nsP ≥ 0.05.

Figure 8.

Treatment with anti-CXCL10 resulted in better retinal function and reduced intraocular inflammation. Treatment with anti‐CXCL10 antibody alone, with or without gatifloxacin (GAT) arrested intraocular inflammation and protected retinal function. C57BL/6J mice were intravitreally injected with 100 CFU B. cereus. At 2 hours postinfection, groups of infected eyes were treated with 250 ng/0.5 µL anti-CXCL10, 1.25 ug/0.5 µL GAT, 0.5 µL PBS containing 250 ng anti-CXCL10 and 1.25 µg GAT, and 0.5 µg/0.5 µL nonspecific isotype IgG2A (Isotype). All eyes were analyzed at 10 hours postinfection. (A) Treatment with gatifloxacin sterilized the eye in both GAT alone and GAT + anti-CXCL10 treated eyes. No differences in bacterial counts were observed between untreated and anti-CXCL10 (P = 0.1320) or isotype-treated (P = 0.2403) eyes. (B) A-wave function was significantly greater in anti-CXCL10 alone (P = 0.0016), GAT alone (P = 0.0109), and GAT + anti-CXCL10 (P = 0.0031) treated eyes compared to untreated eyes. (C) Compared to untreated eyes, B-wave function was significantly retained in anti-CXCL10 alone (P = 0.0031), GAT alone (P = 0.0016), and GAT + anti-CXCL10 (P = 0.0016) treated eyes. No differences in A- or B-wave retention was detected between untreated and isotype-treated eyes. (D) MPO concentrations in infected eyes of mice treated with anti-CXCL10 antibody with or without antibiotics were significantly less than in untreated eyes (*P ≤ 0.01). (E) Pathology analysis showed that eyes of untreated and isotype‐treated mice were similar. Eyes in these groups were inflamed, with the loss of complete retinal architecture. In contrast, there was mild inflammation and undamaged retinal layers in infected eyes treated with anti‐CXCL10 alone, GAT alone, and GAT + anti-CXCL10. Original magnification, × 10. Values represent means ± SEM for n ≥ 5 eyes per group per time point with at least 2 independent experiments. *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, and nsP ≥ 0.05.

To assess whether PMN influx was altered following anti-CXCL2 and/or anti-CXCL10 treatment, MPO concentrations were measured in these eyes and compared with that of untreated eyes. MPO concentrations in untreated eyes were 29-fold higher compared to the uninfected eyes in both anti-CXCL2 and anti-CXCL10 experimental groups (see Figs. 7D, 8D). No differences in MPO concentrations between untreated and isotype control-treated eyes were observed. In contrast, MPO levels in infected eyes treated with anti-CXCL2 alone, GAT alone, or GAT + anti-CXCL2 were 52%, 64%, or 93% lower than that of untreated eyes, respectively (see Fig. 7D). Compared to eyes treated anti-CXCL2 alone or GAT alone, the MPO level was reduced in GAT + anti-CXCL2-treated eyes by 86% and 82%, respectively (Fig. 7D). Similarly, in anti-CXCL10 experimental groups, MPO concentrations in eyes treated with anti-CXCL10 alone, GAT alone, or GAT + anti-CXCL10 were approximately 64%, 81%, and 63% lower than that of untreated eyes, respectively (see Fig. 8D). No differences in MPO levels between eyes treated with anti-CXCL10 alone, GAT alone, and GAT + anti-CXCL10 eyes were observed (P ≥ 0.05; see Fig. 8D).

Histology revealed that control and isotype-treated eyes were greatly inflamed and severely damaged, as described above (see Figs. 7E, 8E). Retinal layers were detached from choroid and were indistinguishable. However, compared to untreated and isotype-treated eyes, eyes treated with GAT alone, anti-CXCL2 alone, GAT + anti-CXCL2, anti-CXCL10 alone, or GAT + anti-CXCL10 were similar in appearance, architecturally better-preserved, and had less inflammatory damage (see Figs. 7E, 8E). Taken together, these results demonstrated that treatment with an anti-CXCL2 or anti-CXCL10 antibody limited intraocular inflammation during B. cereus endophthalmitis. This suggests that CXCL2 and CXCL10 could potentially serve as possible anti-inflammatory therapeutic targets for endophthalmitis.

Discussion

Bacillus endophthalmitis is a devastating intraocular infection resulting in inflammation that frequently leads to blindness due to bystander damage to delicate ocular tissues. During Bacillus endophthalmitis, bacterial and host factors contribute to the development of a damaging inflammatory responses which interferes with ocular immune privilege by recruiting immune cells into the eye.12,29,47,48 Bacterial factors, such as cell wall components and secreted toxins, contribute to a loss of vascular permeability and overt damage to the retina.15–18,21,49 Host factors, such as innate receptors, their adaptors, and immune mediators, also significantly influence the extent of inflammation during this disease.23–25,27,29–31,50 With the increasing numbers of surgical procedures and intraocular injections for the treatment of ocular diseases, the incidence of cases of endophthalmitis will only increase.4,51,52 Moreover, the current approaches to treat endophthalmitis are often unsuccessful in mitigating damaging inflammation.40,53–56 Therefore, rational anti-inflammatory and anti-bacterial targets are needed to prevent the vision loss in this disease.

Among all the Gram-positive pathogens which cause endophthalmitis, Bacillus causes significant damage to ocular tissues in the shortest period of time.12 Although members of the B. cereus sensu lato group (Bacillus thuringiensis and B. cereus) cause the most fulminant forms of bacterial endophthalmitis, other pathogens, such as Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and other streptococcal and enterococcal species can also cause sight-threatening endophthalmitis.7,57–59 Cell wall peptidoglycan, S-layer, flagellar-driven motility, and secreted toxins play a key role in the pathogenesis of Bacillus endophthalmitis.15–18,21,49 TLR2 and TLR4 of the host also play a vital role in the pathogenesis of Bacillus endophthalmitis.23,25 We discovered that Bacillus S-layer protein was an activator of TLR2 and a novel activator of TLR4.42 Downstream from TLRs, innate adaptors such as MyD88 and TRIF also impacted the pathogenesis of Bacillus endophthalmitis.23 Bacterial products interact with and activate TLRs and their adaptors, resulting in the production of a plethora of immune mediators.29,37 Production of inflammatory mediators are linked with clinical signs, including anterior chamber inflammatory cells infiltration and fibrin deposition, vitreous exudate, and posterior synechiae (adhesion of the iris to the lens).12,29 We reported that inflammatory mediators CXCL1, TNFα, IL-1β, and IL-6 were detected as early as 4 hours postinfection, which correlated with fibrin accumulation in the anterior chamber and early neutrophil influx.28 These reports showed that proinflammatory mediator synthesis was associated with neutrophil infiltration and subsequent decline of retinal function, which implied the importance of these inflammatory mediators as targets in directing ocular inflammation and overall endophthalmitis pathogenesis.

Chemoattractants are multifunctional mediators. Depending on the positioning of the first pair of N-terminal cysteine residues chemokines divided into two subfamilies (C-X-C and C-C chemokines). C-C chemokines tend to attract monocytes, whereas C-X-C chemokines recruit neutrophils.34,35 Chemokines are secreted by a broad range of cells, including immune cells such as neutrophils, macrophages, lymphocytes, natural killer cells, and thus play an important role in immune mediated inflammation.60,61 In the eye, these mediators are likely the products of receptor-agonist interactions from retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), astrocytes, corneal epithelium, iris epithelium, retinal microglia, and/or Muller cells.29 We reported that the expression of C-X-C and C-C chemokines observed at 10 hours postinfection with Bacillus was TLR4-dependent.22,30 Of the 12 most highly upregulated chemokines reported in that study, 6 of them belonged to the C-X-C family.22 S. aureus-mediated TLR2 activation of retinal microglia and triggering Muller glia to synthesize C-X-C chemokines.62 To dissect the importance of these mediators and identify potential anti-inflammatory targets, we first investigated CXCL1. We reported that an absence of CXCL1, either by genetic knockout or treatment with neutralizing antibody, minimized inflammatory responses during endophthalmitis, but not completely.31 In the current study, we investigated the role of CXCL2 and CXCL10 during Bacillus endophthalmitis, which were highly upregulated C-X-C chemokines during Bacillus endophthalmitis at 4 hours and 10 hours postinfection.22,30

Chemokines function in recruiting phagocytes and other immune cells to the area of infection, modulating inflammatory and wound healing responses, and directing cell differentiation, proliferation, and polarization. CXCL2 and CXCL10 mobilize cells by interacting with cell surface chemokine receptors CXCR2 and CXCR3, respectively.60,61,63 Endogenous CXCL10 protected mice from viral infection by decreasing viral loads in corneal tissue, and thus the absence of this chemokine aggravated stromal keratitis due to reduced primary neutrophil influx in mice.64 CXCL2 contributed to neutrophil recruitment and activation of their effector functions, including phagocytosis and production of reactive oxygen species in an immune complex-mediated cutaneous inflammation model.65,66 CXCR2-mediated (CXCL2 receptor) signaling is essential to margination of PMNs in S. aureus keratitis.67 CXCL2 and CXCL10 also coordinate several types of cellular functions, including wound healing, angiogenesis, leucocyte recruitment, and internalization of foreign substances.68–71 Most studies on CXCL2 and CXCL10 have been focused on inflammatory cell recruitment, with very few focusing on bacterial internalization. To understand whether the absence of these chemokines altered neutrophil function, we compared the phagocytic capabilities of mouse neutrophils derived from wild type, CXCL2−/−, and CXCL10−/− mice. The absence of CXCL2 or CXCL10 did not alter Bacillus internalization, suggesting that the absence of either of these chemokines did not affect this function in neutrophils.

The vitreous humor contains a variety of organic and inorganic components that support bacterial growth, with no inherent antibacterial effects.72 We reported that B. cereus grows faster than S. epidermidis, S. aureus, E. faecalis, and S. pneumoniae in the mouse eye, and reaches maximum concentrations within 12 hours postinfection.12 During Bacillus endophthalmitis, the absence of innate receptors such as TLR2, TLR4, their adaptor MyD88, or immune mediators IL-6 or CXCL1 did not affect intraocular Bacillus growth.23,25,27,31 We reported that the absence of TNFα resulted in greater intraocular bacterial Bacillus growth, whereas the absence of the TLR4 adaptor TRIF resulted in significantly reduced intraocular Bacillus growth.23,33 Here, we found that in the absence of CXCL2 or CXCL10, Bacillus growth was not affected. Given the similar finding in CXCL1−/− mouse eyes infected with B. cereus31 it appears that these particular chemoattractants do not affect the control of Bacillus growth in the eye.

The retina is a multilayered tissue consisting of photosensitive cells and is responsible for phototransduction. Damage to this tissue is considered irreversible and can disrupt vision.73 We and others have demonstrated that bacterial infection in the eye interferes with retinal structure and integrity, and negatively affects retinal function.28,49,74 During Bacillus endophthalmitis, retinal function declines rapidly compared to endophthalmitis caused by other Gram-positive ocular pathogens.12 The absence of innate receptors TLR2 and TLR4, adaptor molecules MyD88 and TRIF, and chemokine CXCL1 prevented retinal damage and preserved retinal function.23,25,27,31 In the present study, compared to infected C57BL/6J eyes, CXCL2−/−-infected eyes retained significant retinal function, even at 16 hours postinfection. However, CXCL10−/−-infected eyes only retained retinal function up to 8 and 10 hours postinfection. Starting at 12 hours, retinal function in CXCL10−/− infected eyes declined to approximately 25%. In contrast, retinal function in CXCL2−/− eyes declined to 40% to 50% but remained elevated throughout 14 hours. We reported that an absence of CXCL1 preserved retinal structure and integrity, which corresponded with retinal function retention.31 In the current study, retinal architecture was preserved and retinal layers were relatively intact in infected CXCL2−/− eyes at 10, 12, and 14 hours postinfection. Ocular structures were also well preserved in infected CXCL10−/− eyes at earlier time points. However, significant damage was observed after 12 hours postinfection, which correlated with the decline in retinal function in CXCL10−/− eyes after 12 hours postinfection. These findings suggested that the absence of CXCL2 resulted in well preserved retinal structure and integrity for a prolonged period of time after infection, compared to that of the absence of CXCL10. The longer retention of retinal function and better ocular pathology observed in CXCL2−/− mice could be because of the highly elevated CXCL2 expression in ocular environment during Bacillus endophthalmitis.

Chemokines play a crucial role in fighting bacterial infections by recruiting neutrophils to infected tissues. In mice, the chemokines KC (CXCL1) and MIP-2α (CXCL2) fulfill this role.70,75 Neutrophils function as effector cells that kill bacteria and destroy affected tissues mainly through the production of reactive oxygen species.46,48,76 Cytokines TNF-α, IL-6, and CXCL1 were detected as early as 4 hours postinfection during Bacillus endophthalmitis, which correlated with early neutrophil influx and fibrin accumulation in the anterior chamber.28,30,33 High levels of myeloperoxidase, a microbicidal enzyme produced by PMNs,77 have also been detected in the eye during Bacillus endophthalmitis.25 Blocking the TLR2 and TLR4 pathways resulted in significantly reduced myeloperoxidase in infected eyes, which is a marker for reduced inflammation due to limited infiltration of PMN.42 Inhibition of TLR2 and TLR4 activation significantly reduced the expression of chemoattractants that recruit PMNs to the infection site, which ultimately resulted in increased retinal function retention and improved ocular pathology. These studies suggest that the ocular damage and reduced retinal function observed in our current study are partly due to the uncontrolled infiltration of PMNs into the eyes. Here, we observed that at all times PMN influx was significantly reduced in the absence of CXCL2. In infected CXCL10−/− eyes, PMN influx was reduced at only early times, but was similar to that of infected C57BL/6J eyes at later times. These findings correspond to our retinal function and histology data. These findings suggest that, compared to CXCL10, CXCL2 may play a much broader role in the pathogenesis of Bacillus endophthalmitis.

Sex differences related to immune response and inflammation play a role in the susceptibility and pathogenesis of a variety of infections and diseases,78–80 and are therefore an important biological variable.81,82 A recent report demonstrated that aging, not sex and genetic diversity, impacted the pathology of experimental S. aureus endophthalmitis.83 In our study, we separately analyzed the data of male and female C57BL/6J, CXCL2−/−, and CXCL10−/− male and female mice to identify any potential sex differences in our model (see Figs. 23–4). In general, we did not find consistent differences in Bacillus growth or retinal function loss between males and females in these groups, demonstrating that sex was not a significant biological variable for Bacillus endophthalmitis.

At present, treatment options for Bacillus endophthalmitis involve topical, systemic, and intravitreal antibiotics, which can effectively sterilize the infected eye if applied early during infection.84,85 Because severe inflammation is a hallmark of sight-threatening endophthalmitis, corticosteroid use for anti‐inflammatory therapy is common, but their effectiveness in this disease is debatable.39,40,54,86,87 Therefore, identifying viable anti-inflammatory targets is crucial in protecting the infected eye during Bacillus endophthalmitis. Proinflammatory mediator synthesis was associated with neutrophil infiltration and subsequent retinal function decline, which suggested the significance of these mediators as targets in controlling inflammation and overall pathogenesis of Bacillus endophthalmitis.25,28,31,33 Furthermore, targets that drive acute inflammatory responses in Bacillus endophthalmitis may be similar in slower‐developing forms of bacterial endophthalmitis. During Bacillus endophthalmitis, in addition to CXCL1, we identified a cohort of inflammatory mediators whose expression in the retina is dependent upon a functional TLR4.30 However, the role of these cytokines and chemokines in the pathogenesis of Bacillus endophthalmitis and as potential therapeutic targets has not been elucidated.

The proinflammatory chemokine CXCL2 possesses several physiological functions, including cell migration, adhesion, and innate immune responses.75 A receptor antagonist of CXCL2 inhibited glioma growth during tumor initiation and progression, suggesting CXCL2 as a promising therapeutic target in glioma.88 CXCL2 contributes to PMN infiltration in P. aeruginosa-infected corneas and administration of CXCL2 neutralizing antibody reduced PMN infiltration and corneal destruction during P. aeruginosa keratitis.89 Here, we investigated the therapeutic potential of anti-CXCL2 antibody with or without routinely used antibiotics. Because intraocular Bacillus grow very rapidly and PMNs are recruited into the eye as early as 4 hours postinfection, we chose 2 hours postinfection as our time point for treatment. The concentration of GAT and antibody we chose was based on our previously reported findings.90 Early administration of neutralizing antibodies against CXCL2 during experimental B. cereus endophthalmitis resulted in significantly improved retinal function, improved disease pathology, and reduced inflammation at 10 hours postinfection. Because intravitreal antibiotics are critical for eliminating bacteria, we also tested the therapeutic potential of CXCL2 antibody with or without GAT. The combination of GAT and anti-CXCL2 antibody treatment significantly reduced the inflammation compared to anti-CXCL2 antibody or GAT alone.

CXCL10 binds the CXCR3 receptor to induce apoptosis, cell growth, chemotaxis, and angiostasis.91 CXCL10 is also recognized as a biomarker that predicts severity of various diseases.92 Changes in CXCL10 levels have been associated with infectious diseases, immune dysfunction, and tumor development.68,91,93 Administration of anti-CXCL10 antibody served as a promising therapeutic for experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) by decreasing the clinical and histological manifestation in mice.94 CXCL10 neutralization, either by specific antibody or by genetic deletion, protected mice from cerebral malaria infection and inflammation.95 In another study, targeted blocking of CXCL10 or CXCR3 receptor with antibodies attenuated inflammatory colitis in mice.96 Here, administration of anti-CXCL10 antibody to Bacillus-infected eyes reduced inflammatory cell influx, resulting in retained retinal function and reduced disease pathology compared to that of untreated infected mice. However, there was no difference in inflammation or retinal function when anti-CXCL10 antibody with or without GAT or when GAT alone was administered. Although we observed better clinical outcomes in our study using a single antibiotic (gatifloxacin) and single antibodies alone at this early stage of infection, additional studies with different dosages of antibody and different antibiotics are necessary to better conclude the therapeutic potential of neutralizing the important chemokines analyzed in this model.

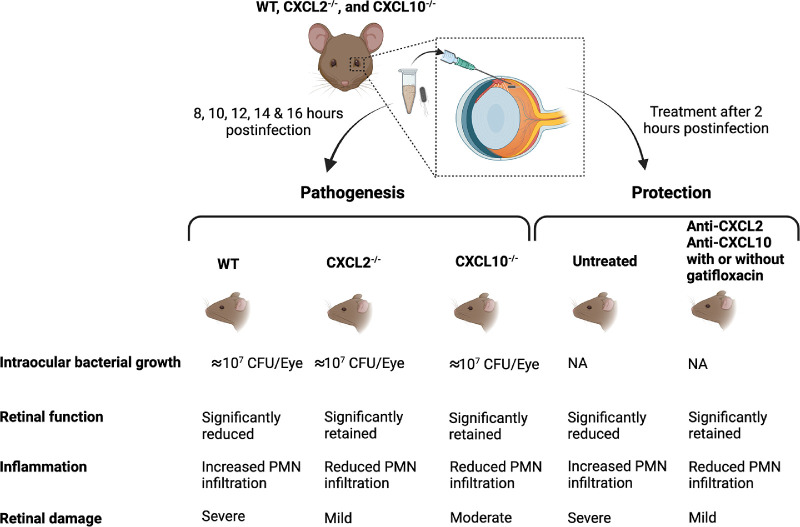

Bacillus endophthalmitis is characterized by uncontrolled and robust acute immune responses that rapidly recruit inflammatory cells and damage host intraocular tissues. Identification of targets that reduce inflammatory cell infiltration into the eye could serve as the basis of novel therapeutic modalities. In this study, we showed that the absence of CXCL2 or CXCL10 by genetic deletion resulted in better retention of retinal function, better ocular pathology, and less inflammation compared to C57BL/6J eyes (Fig. 9). In comparing the absence of CXCL2 with that of CXCL10, the absence of CXCL2 maintained a greater degree of retinal function and less pathology and inflammation. Furthermore, treatment aimed at neutralizing CXCL2 and CXCL10 reduced the inflammation and pathology. Adding gatifloxacin sterilized infected eyes, but synergistic effects with the antibodies were not clearly defined. Overall, our study presents a unique therapeutic approach of targeting chemokines in ocular environment as an anti-inflammation treatment modality that can be tested in conjunction with antibiotics for treating Bacillus endophthalmitis. Because the course of endophthalmitis caused by other Gram-positive pathogens is similar but delayed compared with that of Bacillus endophthalmitis, this therapeutic strategy could have broader applicability.

Figure 9.

Summary of critical findings. Experimental B. cereus endophthalmitis was induced in WT, CXCL2−/−, and CXCL10−/− mice. After various times postinfection, infected eyes were analyzed for pathogenesis. Absence of either CXCL2 or CXCL10 did not affect the intraocular Bacillus growth. Compared to WT, CXCL2−/− and CXCL10−/− mice had significantly retained retinal function, reduced PMN infiltration, and mild to moderate retinal damage. B. cereus-infected WT mouse eyes were treated with anti-CXCL2 or anti-CXCL10 antibodies with or without gatifloxacin at 2 hours postinfection. Compared to untreated eyes, treated eyes showed significantly retained retinal function, reduced PMN infiltration, and mild retinal damage. Created with BioRender.com.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Feng Li and Mark Dittmar (OUHSC P30 Live Animal Imaging Core, Dean A. McGee Eye Institute, Oklahoma City, OK, USA), and the OUHSC P30 Cellular Imaging Core (Dean A. McGee Eye Institute, Oklahoma City, OK, USA) for histology expertise.

Supported by National Institutes of Health grants R21EY028066 and R01EY028810 (to M.C.C.). Our research is also supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants R21EY021802 (to M.C.C.), National Eye Institute Vision Core Grant P30EY021725 (to M.C.C.), a Presbyterian Health Foundation Research Support Grant Award (to M.C.C.), and an unrestricted grant to the Dean A. McGee Eye Institute from Research to Prevent Blindness.

Disclosure: M.H. Mursalin, None; P.S. Coburn, None; F.C. Miller, None; E.T. Livingston, None; R. Astley, None; M.C. Callegan, None

References

- 1. Coburn PS, Callegan MC. Endophthalmitis. In: Rumelt S, ed. Advances in Ophthalmology. London, IntechOpen; 2012: 319–340. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cunningham ET, Flynn HW, Relhan N, Zierhut M. Endogenous Endophthalmitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm . 2018; 26(4): 491–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rahmani S, Eliott D.. Postoperative Endophthalmitis: A Review of Risk Factors, Prophylaxis, Incidence, Microbiology, Treatment, and Outcomes. Semin Ophthalmol . 2018; 33(1): 95–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dehghani AR, Rezaei L, Salam H, Mohammadi Z, Mahboubi M.. Post traumatic endophthalmitis: incidence and risk factors. Glob J Health Sci . 2014; 6(6): 68–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Durand ML. Bacterial and Fungal Endophthalmitis. Clin Microbiol Rev . 2017; 30(3): 597–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sansome SG, Ting M, Jain S. Endophthalmitis. Br J Hosp Med (Lond) . 2019; 80(1): C8–C11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Parkunan S.M., Callegan MC. The pathogenesis of bacterial endophthalmitis. In: Durand ML, Miller JW, Young LHY, eds. Endophthalmitis . Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2016: 17–47. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Enosi Tuipulotu D, Mathur A, Ngo C, Man SM. Bacillus cereus: Epidemiology, Virulence Factors, and Host-Pathogen Interactions. Trends Microbiol . 2021; 29(5): 458–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ehling-Schulz M, Lereclus D, Koehler TM.. The Bacillus cereus Group: Bacillus Species with Pathogenic Potential. Microbiol Spectr . 2019; 7(3): 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jessberger N, Dietrich R, Granum PE, Märtlbauer E.. The Bacillus cereus Food Infection as Multifactorial Process. Toxins (Basel) . 2020; 12(11): 701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Miller JJ, Scott IU, Flynn HW Jr., et al. Endophthalmitis caused by Bacillus species. Am J Ophthalmol . 2008; 145(5): 883–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mursalin MH, Livingston ET, Callegan MC.. The cereus matter of Bacillus endophthalmitis. Exp Eye Res . 2020; 193: 107959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lam KC. Endophthalmitis caused by Bacillus cereus: a devastating ophthalmological emergency. Hong Kong Med J . 2015; 21(5): 475.e471–475.e472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gregory M, Callegan MC, Gilmore MS.. Role of bacterial and host factors in infectious endophthalmitis. Chem Immunol Allergy . 2007; 92: 266–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Callegan MC, Cochran DC, Kane ST, et al.. Contribution of membrane-damaging toxins to Bacillus endophthalmitis pathogenesis. Infect Immun . 2002; 70(10): 5381–5389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Callegan MC, Jett BD, Hancock LE, Gilmore MS.. Role of hemolysin BL in the pathogenesis of extraintestinal Bacillus cereus infection assessed in an endophthalmitis model. Infect Immun . 1999; 67(7): 3357–3366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Callegan MC, Kane ST, Cochran DC, et al.. Relationship of plcR-regulated factors to Bacillus endophthalmitis virulence. Infect Immun . 2003; 71(6): 3116–3124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Callegan MC, Kane ST, Cochran DC, et al.. Bacillus endophthalmitis: roles of bacterial toxins and motility during infection. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci . 2005; 46(9): 3233–3238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Callegan MC, Novosad BD, Ramirez R, Ghelardi E, Senesi S.. Role of swarming migration in the pathogenesis of Bacillus endophthalmitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci . 2006; 47(10): 4461–4467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Callegan MC, Parkunan SM, Randall CB, et al.. The role of pili in Bacillus cereus intraocular infection. Exp Eye Res . 2017; 159: 69–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mursalin MH, Coburn PS, Livingston E, et al.. S-layer Impacts the Virulence of Bacillus in Endophthalmitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci . 2019; 60(12): 3727–3739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mursalin MH, Coburn PS, Miller FC, et al.. Innate Immune Interference Attenuates Inflammation in Bacillus Endophthalmitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci . 2020; 61(13): 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Parkunan SM, Randall CB, Coburn PS, et al.. Unexpected Roles for Toll-Like Receptor 4 and TRIF in Intraocular Infection with Gram-Positive Bacteria. Infect Immun . 2015; 83(10): 3926–3936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Parkunan SM, Astley R, Callegan MC.. Role of TLR5 and flagella in Bacillus intraocular infection. PLoS One . 2014; 9(6): e100543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Novosad BD, Astley RA, Callegan MC.. Role of Toll-like receptor (TLR) 2 in experimental Bacillus cereus endophthalmitis. PLoS One . 2011; 6(12): e28619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Muzio M, Polentarutti N, Bosisio D, Manoj Kumar PP, Mantovani A. Toll-like receptor family and signalling pathway. Biochem Soc Trans . 2000; 28(5): 563–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Parkunan SM, Roehrkasse AM, Staats RL, Callegan MC.. Role of MyD88-dependent and MyD88-independent Pathways in Bacillus cereus Endophthalmitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci . 2014; 55(13): 2872–2872. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ramadan RT, Ramirez R, Novosad BD, Callegan MC.. Acute inflammation and loss of retinal architecture and function during experimental Bacillus endophthalmitis. Curr Eye Res . 2006; 31(11): 955–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Miller FC, Coburn PS, Huzzatul MM, et al.. Targets of immunomodulation in bacterial endophthalmitis. Prog Retin Eye Res . 2019; 73(100763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Coburn PS, Miller FC, LaGrow AL, et al. TLR4 modulates inflammatory gene targets in the retina during Bacillus cereus endophthalmitis. BMC Ophthalmol . 2018; 18(1): 96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Parkunan SM, Randall CB, Astley RA, Furtado GC, Lira SA, Callegan MC.. CXCL1, but not IL-6, significantly impacts intraocular inflammation during infection. J Leukoc Biol . 2016; 100(5): 1125–1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Moyer AL, Ramadan RT, Thurman J, Burroughs A, Callegan MC.. Bacillus cereus induces permeability of an in vitro blood-retina barrier. Infect Immun . 2008; 76(4): 1358–1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ramadan RT, Moyer AL, Callegan MC.. A role for tumor necrosis factor-alpha in experimental Bacillus cereus endophthalmitis pathogenesis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci . 2008; 49(10): 4482–4489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fernandez EJ, Lolis E.. Structure, function, and inhibition of chemokines. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol . 2002; 42: 469–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Allen SJ, Crown SE, Handel TM.. Chemokine: receptor structure, interactions, and antagonism. Annu Rev Immunol . 2007; 25: 787–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Brubaker SW, Bonham KS, Zanoni I, Kagan JC.. Innate immune pattern recognition: a cell biological perspective. Annu Rev Immunol . 2015; 33: 257–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fitzgerald KA, Kagan JC.. Toll-like Receptors and the Control of Immunity. Cell . 2020; 180(6): 1044–1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Das T, Choudhury K, Sharma S, Jalali S, Nuthethi R, Endophthalmitis Research Group. Clinical profile and outcome in Bacillus endophthalmitis. Ophthalmology . 2001; 108(10): 1819–1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Callegan MC, Parke DW, 2nd Gilmore MS. Corticosteroid and antibiotic therapy for Bacillus endophthalmitis. Arch Ophthalmol . 2001; 119(9): 1391–1393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Liu SM, Way T, Rodrigues M, Steidl SM.. Effects of intravitreal corticosteroids in the treatment of Bacillus cereus endophthalmitis. Arch Ophthalmol . 2000; 118(6): 803–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Callegan MC, Guess S, Wheatley NR, et al.. Efficacy of vitrectomy in improving the outcome of Bacillus cereus endophthalmitis. Retina . 2011; 31(8): 1518–1524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mursalin MH, Coburn PS, Livingston E, et al.. Bacillus S-Layer-Mediated Innate Interactions During Endophthalmitis. Front Immunol . 2020; 11: 215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Moyer AL, Ramadan RT, Novosad BD, Astley R, Callegan MC.. Bacillus cereus-induced permeability of the blood-ocular barrier during experimental endophthalmitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci . 2009; 50(8): 3783–3793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Coburn PS, Miller FC, LaGrow AL, et al.. Disarming Pore-Forming Toxins with Biomimetic Nanosponges in Intraocular Infections. mSphere . 2019; 4(3): e00262–e00319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. LaGrow AL, Coburn PS, Miller FC, et al.. A Novel Biomimetic Nanosponge Protects the Retina from the Enterococcus faecalis Cytolysin. mSphere . 2017; 2(6): e00335–e00417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Malech HL, Deleo FR, Quinn MT.. The role of neutrophils in the immune system: an overview. Methods Mol Biol . 2014; 1124: 3–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Coburn PS, Miller FC, Enty MA, et al.. The Bacillus virulome in endophthalmitis. Microbiology (Reading) . 2021; 167(5): 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Livingston ET, Mursalin MH, Callegan MC.. A Pyrrhic Victory: The PMN Response to Ocular Bacterial Infections. Microorganisms . 2019; 7(11): 573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Callegan MC, Booth MC, Jett BD, Gilmore MS.. Pathogenesis of gram-positive bacterial endophthalmitis. Infect Immun . 1999; 67(7): 3348–3356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Coburn PS, Miller FC, Enty MA, et al.. Expression of Bacillus cereus Virulence-Related Genes in an Ocular Infection-Related Environment. Microorganisms . 2020; 8(4): 607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Mishra C, Lalitha P, Rameshkumar G, et al.. Incidence of Endophthalmitis after Intravitreal Injections: Risk Factors, Microbiology Profile, and Clinical Outcomes. Ocul Immunol Inflamm . 2018; 26(4): 559–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ledbetter EC, Spertus CB, Kurtzman RZ.. Incidence and characteristics of acute-onset postoperative bacterial and sterile endophthalmitis in dogs following elective phacoemulsification: 1,447 cases (1995-2015). J Am Vet Med Assoc . 2018; 253(2): 201–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Pan Q, Liu Y, Wang R, Chen T, et al.. Treatment of Bacillus cereus endophthalmitis with endoscopy-assisted vitrectomy. Medicine (Baltimore) . 2017; 96(50): e8701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sakalar YB, Ozekinci S, Celen MK.. Treatment of experimental Bacillus cereus endophthalmitis using intravitreal moxifloxacin with or without dexamethasone. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther . 2011; 27(6): 593–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Yang C-S, Lu C-K, Lee F-L, et al.. Treatment and outcome of traumatic endophthalmitis in open globe injury with retained intraocular foreign body. Ophthalmologica . 2010; 224(2): 79–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Vahey JB, Flynn HW Jr. Results in the management of Bacillus endophthalmitis. Ophthalmic Surg . 1991; 22(11): 681–686. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Fayad N, Kallassy Awad M, Mahillon J. Diversity of Bacillus cereus sensu lato mobilome. BMC Genomics . 2019; 20(1): 436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Major JC Jr., Engelbert M, Flynn HW, et al.. Staphylococcus aureus endophthalmitis: antibiotic susceptibilities, methicillin resistance, and clinical outcomes. Am J Ophthalmol . 2010; 149(2): 278–283.e271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Miller JJ, Scott IU, Flynn HW Jr., et al.. Endophthalmitis caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae. Am J Ophthalmol . 2004; 138(2): 231–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Abdulkhaleq LA, Assi MA, Abdullah R, et al.. The crucial roles of inflammatory mediators in inflammation: A review. Vet World . 2018; 11(5): 627–635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Baggiolini M. Chemokines and leukocyte traffic. Nature . 1998; 392(6676): 565–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Shamsuddin N, Kumar A.. TLR2 mediates the innate response of retinal Muller glia to Staphylococcus aureus. J Immunol . 2011; 186(12): 7089–7097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Liu K, Wu L, Yuan S, Wu M, et al.. Structural basis of CXC chemokine receptor 2 activation and signalling. Nature . 2020; 585(7823): 135–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Shen FH, Wang SW, Yeh TM, et al.. Absence of CXCL10 aggravates herpes stromal keratitis with reduced primary neutrophil influx in mice. J Virol . 2013; 87(15): 8502–8510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Li JL, Lim CH, Tay FW, et al.. Neutrophils Self-Regulate Immune Complex-Mediated Cutaneous Inflammation through CXCL2. J Invest Dermatol . 2016; 136(2): 416–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Metzemaekers M, Gouwy M, Proost P.. Neutrophil chemoattractant receptors in health and disease: double-edged swords. Cell Mol Immunol . 2020; 17(5): 433–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Cole N, Hume EBH, Khan S, et al.. The role of CXC chemokine receptor 2 in Staphylococcus aureus keratitis. Exp Eye Res . 2014; 127: 184–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Martins-Green M, Petreaca M, Wang L.. Chemokines and Their Receptors Are Key Players in the Orchestra That Regulates Wound Healing. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle) . 2013; 2(7): 327–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Sommer F, Torraca V, Meijer AH.. Chemokine Receptors and Phagocyte Biology in Zebrafish. Front Immunol . 2020; 11: 325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Sawant KV, Sepuru KM, Lowry E, et al.. Neutrophil recruitment by chemokines Cxcl1/KC and Cxcl2/MIP2: Role of Cxcr2 activation and glycosaminoglycan interactions. J Leukoc Biol . 2021; 109(4): 777–791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Zhang H, Ye YL, Li MX, et al.. CXCL2/MIF-CXCR2 signaling promotes the recruitment of myeloid-derived suppressor cells and is correlated with prognosis in bladder cancer. Oncogene . 2017; 36(15): 2095–2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Le Goff MM, Bishop PN. Adult vitreous structure and postnatal changes. Eye . 2008; 22(10): 1214–1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Hoon M, Okawa H, Della Santina L, Wong RO. Functional architecture of the retina: development and disease. Prog Retin Eye Res . 2014; 42: 44–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Kumar A, Kumar A.. Role of Staphylococcus aureus Virulence Factors in Inducing Inflammation and Vascular Permeability in a Mouse Model of Bacterial Endophthalmitis. PLoS One . 2015; 10(6): e0128423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Sokol CL, Luster AD.. The chemokine system in innate immunity. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol . 2015; 7(5): a016303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Czuprynski CJ, Henson PM, Campbell PA.. Killing of Listeria monocytogenes by inflammatory neutrophils and mononuclear phagocytes from immune and nonimmune mice. J Leukoc Biol . 1984; 35(2): 193–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Aratani Y. Myeloperoxidase: Its role for host defense, inflammation, and neutrophil function. Arch Biochem Biophys . 2018; 640: 47–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Klein SL, Flanagan KL.. Sex differences in immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol . 2016; 16(10): 626–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Scully EP, Haverfield J, Ursin RL, Tannenbaum C, Klein SL.. Considering how biological sex impacts immune responses and COVID-19 outcomes. Nat Rev Immunol . 2020; 20(7): 442–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Riccio RE, Park SJ, Longnecker R, Kopp SJ.. Characterization of Sex Differences in Ocular Herpes Simplex Virus 1 Infection and Herpes Stromal Keratitis Pathogenesis of Wild-Type and Herpesvirus Entry Mediator Knockout Mice. mSphere . 2019; 4(2): e00073–e00119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Lee SK. Sex as an important biological variable in biomedical research. BMB Rep . 2018; 51(4): 167–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Miller LR, Marks C, Becker JB, et al.. Considering sex as a biological variable in preclinical research. Faseb J . 2017; 31(1): 29–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Singh PK, Singh S, Wright RE III, Rattan R, Aging Kumar A., But Not Sex and Genetic Diversity, Impacts the Pathobiology of Bacterial Endophthalmitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci . 2020; 61(14): 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Callegan MC, Engelbert M, Parke DW, 2nd Jett BD, Gilmore MS. Bacterial endophthalmitis: epidemiology, therapeutics, and bacterium-host interactions. Clin Microbiol Rev . 2002; 15(1): 111–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Callegan MC, Gilmore MS, Gregory M, et al.. Bacterial endophthalmitis: therapeutic challenges and host-pathogen interactions. Prog Retin Eye Res . 2007; 26(2): 189–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Pollack JS, Beecher DJ, Pulido JS, Lee Wong AC. Failure of intravitreal dexamethasone to diminish inflammation or retinal toxicity in an experimental model of Bacillus cereus endophthalmitis. Curr Eye Res . 2004; 29(4-5): 253–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Wiskur BJ, Robinson ML, Farrand AJ, Novosad BD, Callegan MC.. Toward improving therapeutic regimens for Bacillus endophthalmitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci . 2008; 49(4): 1480–1487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Acker G, Zollfrank J, Jelgersma C, et al.. The CXCR2/CXCL2 signalling pathway - An alternative therapeutic approach in high-grade glioma. Eur J Cancer . 2020; 126: 106–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Kernacki KA, Barrett RP, Hobden JA, Hazlett LD.. Macrophage inflammatory protein-2 is a mediator of polymorphonuclear neutrophil influx in ocular bacterial infection. J Immunol . 2000; 164(2): 1037–1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. LaGrow A, Coburn P, Miller FC, et al.. Biomimetic nanosponges augment gatifloxacin in reducing retinal damage during experimental MRSA endophthalmitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci . 2019; 60(9): 4632–4632.31682714 [Google Scholar]

- 91. Liu M, Guo S, Hibbert JM, et al.. CXCL10/IP-10 in infectious diseases pathogenesis and potential therapeutic implications. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev . 2011; 22(3): 121–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Kumar NP, Moideen K, Nancy A, et al.. Plasma chemokines are biomarkers of disease severity, higher bacterial burden and delayed sputum culture conversion in pulmonary tuberculosis. Scientific Reports . 2019; 9(1): 18217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Koper OM, Kamińska J, Sawicki K, Kemona H.. CXCL9, CXCL10, CXCL11, and their receptor (CXCR3) in neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration. Adv Clin Exp Med . 2018; 27(6): 849–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Narumi S, Kaburaki T, Yoneyama H, Iwamura H, Kobayashi Y, Matsushima K.. Neutralization of IFN-inducible protein 10/CXCL10 exacerbates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Eur J Immunol . 2002; 32(6): 1784–1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Wilson NO, Solomon W, Anderson L, et al.. Pharmacologic inhibition of CXCL10 in combination with anti-malarial therapy eliminates mortality associated with murine model of cerebral malaria. PLoS One . 2013; 8(4): e60898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Singh UP, Venkataraman C, Singh R, Lillard JW Jr. CXCR3 axis: role in inflammatory bowel disease and its therapeutic implication. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets . 2007; 7(2): 111–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]