Abstract

Empirical audit and review is an approach to assessing the evidentiary value of a research area. It involves identifying a topic and selecting a cross-section of studies for replication. We apply the method to research on the psychological consequences of scarcity. Starting with the papers citing a seminal publication in the field, we conducted replications of 20 studies that evaluate the role of scarcity priming in pain sensitivity, resource allocation, materialism, and many other domains. There was considerable variability in the replicability, with some strong successes and other undeniable failures. Empirical audit and review does not attempt to assign an overall replication rate for a heterogeneous field, but rather facilitates researchers seeking to incorporate strength of evidence as they refine theories and plan new investigations in the research area. This method allows for an integration of qualitative and quantitative approaches to review and enables the growth of a cumulative science.

Keywords: scarcity, reproducibility, open science, meta-analysis, evidentiary value

Over the past decade, behavioral scientists have investigated how scarcity, or a lack of resources, changes how people think and behave, and how those changes can perpetuate poverty and other negative consequences such as reduced life expectancy (1), reduced cognitive ability (2), impulsiveness (3), and pain (4). Perhaps most strikingly, researchers have found that even otherwise prosperous people can fall into a scarcity mindset (5, 6). Because of its importance, researchers have worked tirelessly to understand scarcity’s origins and outcomes. What is the state of the evidence?

Assessing the Evidence of a Literature

During the same decade in which research has explored the psychology of scarcity, behavioral scientists have been revisiting commonplace scientific practices. Selective reporting of measures, treatments, and analyses, and the p-hacking they enable (7) has been identified as an existential threat to behavioral science (8, 9), a threat evident in large-scale replication efforts (10, 11). If researchers accept that not all published evidence is robust to replication, then they must wonder which evidence they should learn from.

Historically, there have been two broad categories of summary: the qualitative review and the quantitative meta-analysis. The former benefits from being broadly inclusive and flexibly articulated. It is a great tool for corralling the various questions researchers ask and the methods they use for finding answers. It is, however, unable to give a quantitative assessment of the underlying evidence. Meta-analysis seems promising in its attempts to use existing data to generate an overall estimate of effects. But meta-analysis risks reifying selectively reported findings (12), is vulnerable to biased selection (13), is indifferent to the quality of the original evidence (14), and answers a question that no one was asking, i.e., what the average effect of dissimilar studies is (15). These are both useful approaches, but they have limitations.

We develop and employ a third alternative: empirical review and audit. This approach defines the bounds of a topic area, followed by the identification and selection of studies that belong to that literature. Close replications of a broad cross-section of these studies allow for a systematic assessment of their robustness to replication.

This approach offers at least four notable advantages. First, the study identification process can limit bias through a clear inclusion rule and random selection within it or alternatively, carefully define the selection bias (e.g., by selecting the most-cited relevant paper from each year). Second, all methods and analyses can be preregistered, so the consequent empirical results will be free of selective reporting. Third, the reporting is not dependent on the results of the replications. We report all our results and consign none to the file drawer. This makes the results of our replications a better estimate of true effect sizes than any meta-analysis that is vulnerable to selective reporting and any publication that is usually dependent on the statistical significance of the results. Finally, the cumulative results offer a practical starting point for someone entering the discipline. The advantages of our approach allow researchers to get a clear sense of the quality of evidence for a specific topic area.

Method

We selected 20 studies for replication. We built a set of eligible papers and then drew from that set at random. The set included studies that 1) cited Shah et al.’s (2012) seminal paper on scarcity (5), 2) included scarcity as a factor in their design, and 3) could be replicated with an online sample. We did not decide on an operational definition of scarcity, but we accepted all measures and manipulations of scarcity that were proposed by the original authors. An initial set of 198 articles citing Shah et al. (2012) was evaluated by two reviewers from the research team, assigned at random (5). This set was narrowed to 32 articles that met all criteria, and at least one member of the research team believed contained studies which could be conducted online. This set was further narrowed to 23 that met all criteria and that both reviewers believed could be conducted online. If a paper contained multiple qualifying studies, we chose one at random. Although our selection rule might seem to allow a wide range of studies into the consideration set, we do not view this as a problem. Because the empirical audit and review is broad in its focus by definition, we opted not to substitute the authors’ definition of a concept with our own. Instead, an empirical audit and review can cover the entire scope of a research domain and does not rely on averaging or homogenizing the studies in a research area. As such, it can identify those strands of the topic that seem to have greater empirical merit, while allowing readers to consider and focus on the set of studies and characteristics that are relevant to their interests.

Each of the studies we selected used different manipulations and measures, but they had some commonalities. (The studies that are referenced directly in the text are cited in the main paper. The remaining studies are cited in SI Appendix as 1 through 13.) All included a conceptualization of scarcity as a factor in the study design, whether by asking people to consider a time they lacked resources, by restricting the supply of resources in the context of the experiment, or exposing people to images consistent with the absence of resources. The University of California Berkeley Institutional Review Board approved each study and participants provided their consent online at the start of each study.

Members of our research team had primary responsibility for replicating one study and secondary oversight for another study. We used original materials when possible and contacted the original authors if we encountered issues in recreating the study. We preregistered all methods, analyses, and sample sizes. To give us sufficient precision to comment on the statistical power of the original effects, our replications employed 2.5 times the sample size of the original paper (8). Because this approach would also allow us to detect smaller effects than in the original studies, it would have allowed us to detect significant effects even in the cases where the original findings were not significant.

Results

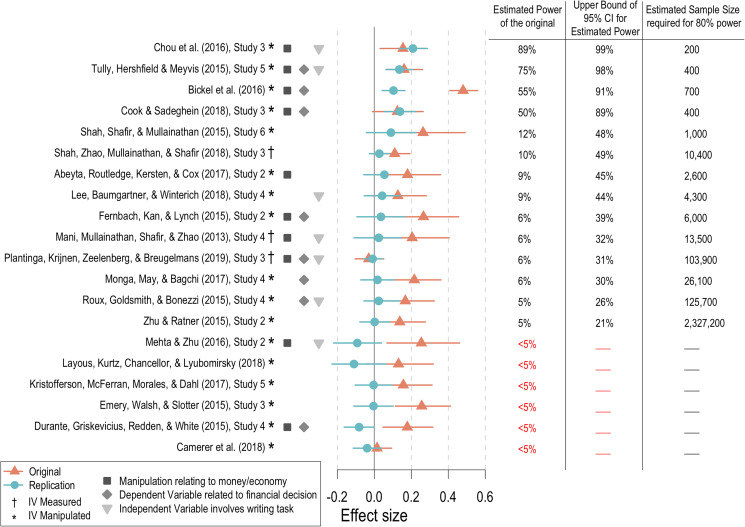

Fig. 1 shows our results. The Leftmost columns categorize commonalities among the 20 studies. In the six studies featuring writing independent variables we reviewed the responses for nonsensical or careless responses and excluded them. Results including these responses are in SI Appendix. The Middle column shows that replication effect sizes were smaller than the original effect sizes for 80% of the 20 studies, and directionally opposite for 30% of these 20 studies. Of the 20 studies that were significant in the original, four of our replication efforts yielded significant results. But significance is only one way to evaluate the results of a replication. The three Rightmost columns report estimates of the power in the original studies based on the replication effects. This analysis provides the upper bounds of the 95% CI for the estimated power of the original studies. Only 9 of the original studies included 33% power in these 95% CIs, indicating that most of the 20 effects we attempted to replicate were too small to be detectably studied in the original investigations.

Fig. 1.

The Leftmost columns indicate common features among the replicated studies and the Middle column depicts effect size (correlation coefficients) for the original and replication studies. Effect sizes are bounded by 95% CIs. The Right columns indicate the estimated power in the original studies (third column from Right), the upper bound of the 95% CI for estimated power in the original (second column from Right), and well as an estimated sample size required for 80% power, based on the replication effect (Rightmost column).

Empirical audit and review can look past aggregate conclusions to see either the specific cases that look empirically sound or categories of research manipulations or measures that seem stronger than others. While these 20 studies are conceptually linked, there is no reason to assume that all hypotheses, designs, and tests are equally representative. Although most of our replications did not approach statistical significance, those that did (4, 16–18) shared some common features. Generally, they included scarcity manipulations related to economic scarcity and used dependent variables related to economic decisions. Three of the four successful replications involved priming participants with some type of financial constraint and then requiring them to engage in a financial or consumer decision task under these constraints. These commonalities suggest that a researcher who wants to build on scarcity priming literature should focus on how economic constraints affect financial decisions but shy away from attempting to build on the literature relating to other effects of scarcity.

General Discussion

Scarcity is a real and enduring societal problem, yet our results suggest that behavioral scientists have not fully identified the underlying psychology. Although this project has neither the goal nor the capacity to “accept the null” hypothesis for any of these tests, the replications of these 20 studies indicate that within this set, scarcity primes have a minimal influence on cognitive ability, product attitudes, or well being. Nevertheless, feeling poor may influence financial and consumer decisions.

We used well-defined criteria for inclusion in our investigation. That is a strength in that it means there are conceptual links between the studies or methodological links in their execution. Nevertheless, it is also a weakness for further generalization. Perhaps studies conducted online are inherently smaller in effect size or more variable in replicability. Furthermore, some of the largest effects reported in the scarcity literature draw on considerably more-difficult-to-reach communities and pose a challenge to replication efforts (e.g., the field studies from ref. 2). Although many of our replications failed to find evidence for the psychological consequences of primed scarcity, real-life scarcity likely has many antecedents and consequences. Despite these limitations, our studies indicate that scarcity studies conducted online and using experimental manipulations do not reliably replicate.

Researchers strive to build a cumulative science. The idiosyncrasies of research questions, designs, and analyses can make that difficult, especially when publication bias and p-hacking distort findings. Qualitative reviews and meta-analyses offer imperfect solutions to the problem. The empirical audit and review corrals the disparate evidence and offers a tidier collection of findings. By identifying the strongest and weakest evidence, future researchers can build on the more solid parts of that foundation.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Dean’s office at the Haas School of Business for providing funding. NSF Graduate Research Fellowship Program Award DGE 1752814 supported S.A., M.E.E.-L., R.F., R.J., S.N.J., and J.M.O.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2103313118/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability

All original data, preregistration documents, and analysis code have been deposited in the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/a2e96/) (19).

References

- 1.Chetty R., et al., The association between income and life expectancy in the United States, 2001-2014. JAMA 315, 1750–1766 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mani A., Mullainathan S., Shafir E., Zhao J., Poverty impedes cognitive function. Science 341, 976–980 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spears D., Economic decision-making in poverty depletes behavioral control. B.E. J. Econ. Anal. Policy 11, 1–42 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chou E. Y., Parmar B. L., Galinsky A. D., Economic insecurity increases physical pain. Psychol. Sci. 27, 443–454 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shah A. K., Mullainathan S., Shafir E., Some consequences of having too little. Science 338, 682–685 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shah A. K., Shafir E., Mullainathan S., Scarcity frames value. Psychol. Sci. 26, 402–412 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simmons J. P., Nelson L. D., Simonsohn U., False-positive psychology: Undisclosed flexibility in data collection and analysis allows presenting anything as significant. Psychol. Sci. 22, 1359–1366 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simonsohn U., Small telescopes: Detectability and the evaluation of replication results. Psychol. Sci. 26, 559–569 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vazire S., Quality uncertainty erodes trust in science. Collabra Psychol. 3, 10.1525/collabra.74. (2017). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Open Science Collaboration, Psychology. Estimating the reproducibility of psychological science. Science 349, aac4716 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Camerer C. F., et al., Evaluating the replicability of social science experiments in Nature and Science between 2010 and 2015. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2, 637–644 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahmed I., Sutton A. J., Riley R. D., Assessment of publication bias, selection bias, and unavailable data in meta-analyses using individual participant data: A database survey. BMJ 344, d7762 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vosgerau J., Simonsohn U., Nelson L. D., Simmons J. P., 99% impossible: A valid, or falsifiable, internal meta-analysis. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 148, 1628–1639 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ioannidis J. P., The mass production of redundant, misleading, and conflicted systematic reviews and meta‐analyses. Milbank Q. 94, 485–514 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nelson L., Data Colada, How Many Studies Have Not Been Run? Why We Still Think the Average Effect Does Not Exist, datacolada.org/70. Accessed 25 June 2021.

- 16.Bickel W. K., Wilson A. G., Chen C., Koffarnus M. N., Franck C. T., Stuck in time: Negative income shock constricts the temporal window of valuation spanning the future and the past. PLoS One 11, e0163051 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cook L. A., Sadeghein R., Effects of perceived scarcity on financial decision making. J. Public Policy Mark. 37, 68–87 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tully S. M., Hershfield H. E., Meyvis T., Seeking lasting enjoyment with limited money: Financial constraints increase preference for material goods over experiences. J. Consum. Res. 42, 59–75 (2015). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All original data, preregistration documents, and analysis code have been deposited in the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/a2e96/) (19).