Abstract

Utilizing population-based data from the Covid-19 phone survey () of the Malawi Longitudinal Study of Families and Health (MLSFH) collected during June 2nd–August 17th, 2020, we focus on the crucial role that community leadership and trust in institutions played in shaping behavioral, economic and social responses to Covid-19 in this low-income sub-Saharan African context. We argue that the effective response of Malawi to limit the spread of the virus was facilitated by the engagement of local leadership to mobilize communities to adapt and adhere to Covid-19 prevention strategies. Using linear and ordered probit models and controlling for time fixed effects, we show that village heads (VHs) played pivotal role in shaping individuals’ knowledge about the pandemic and the adoption of preventive health behaviors and were crucial for mitigating the negative economic and health consequences of the pandemic. We further show that trust in institutions is of particular importance in shaping individuals’ behavior during the pandemic, and these findings highlight the pivotal role of community leadership in fostering better compliance and adoption of public health measures essential to contain the virus. Overall, our findings point to distinctive patterns of pandemic response in a low-income sub-Saharan African rural population that emphasized local leadership as mediators of public health messages and policies. These lessons from the first pandemic wave remain relevant as in many low-income countries behavioral responses to Covid-19 will remain the primary prevention strategy for a foreseeable future.

Keywords: Community leadership, Village heads, Behavioral responses, Economic responses, Trust in Local/National Institutions, Sub-Saharan Africa, Low-income countries

1. Introduction

Dire predictions about the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic in low-income countries (LICs) and especially in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) were abundant in the early phase of the pandemic in 2020 (Van Zandvoort et al., 2020, Shuchman, 2020, Gates, 2020, Walker et al., 2020). Many of the initial pandemic models based on evidence generated outside of the continent and primarily in high-income contexts (Salyer et al., 2021) predicted high numbers of Covid-19 infections resulting in severe morbidity and mortality in the SSA region due to the confluence of several factors: fragile health care infrastructures not able to provide effective care for a large expected number of infected people, high prevalence of other infectious diseases and neglected tropical diseases and malaria (NTDM), over-crowded living arrangements and economies mostly structured around manual labor that restricts the implementation of containment measures such as social distancing or remote work (The Lancet, 2020).

Yet, the pandemic unfolded differently in Malawi, a LIC SSA country ranked 174 out of 189 on the human development index (HDI) (UNDP, 2000): as of January 19, 2021, the period when Malawi reported the highest number of Covid-19 cases during the second wave, the country was ranked 186 in terms of cumulative Covid-19 cases per 1 Million population (Worldometers, 2020). While there is likely under-reporting of Covid-19 cases and deaths, the basic conclusion of a generally low Covid-19 incidence is corroborated by evidence of limited Covid-19 excess mortality (Bamgboye et al., 2020) or prevalence of Covid-19 symptoms (see Section 3).

SSA countries reported in May 2021 only about 2% of all global Covid-19 cases and deaths, despite accounting for about 14% of the world’s population (Kaneda & Ashford, 2021). In light of how the pandemic unfolded in sub-Saharan African low-income countries (SSA LICs), including Malawi, the possibility of a “sub-Saharan African Covid-19 puzzle” has been raised in both scientific journals and the popular media (Maeda and Nkengasong, 2021, Mbow et al., 2020, Bearak and Paquette, 2020, Mukherjee, 2021). Explanations for these patterns, however, have been incomplete (Maeda & Nkengasong, 2021). Demography, and specifically young population age structures, fewer chronic co-morbidities linked to Covid-19 mortality and more circulating seasonal coronaviruses do not fully account for the low Covid-19 prevalence (Walker et al., 2020). Government spending on prevention and testing are also an unlikely explanation: for instance, in Malawi an estimated $213 Millions required for effective pandemic responses faced $19 Millions available for program implementation (The Republic of Malawi, 2020), and vaccine roll-out is still very limited with the government having committed to the AstraZeneca vaccine on February 1, 2021 and roll-out since March 2021.

In this study, we use data from the 2020 Covid-19 Phone Survey of the Malawi Longitudinal Study of Families and Health (MLSFH) (Kohler et al., 2015, Kohler et al., 2020) collected during June 2nd—August 26th, 2020. We argue that the effective response of Malawi to limit the direct health impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic was facilitated by the effective engagement of local leaders to mobilize communities to adapt and adhere to Covid-19 prevention strategies. More specifically, we investigate the crucial role that local community leaders play in building social capital (i.e., disease knowledge, adoption of preventive health behavior) and promoting trust in governmental and health authorities and their health policies during the pandemic. The 2020 MLSFH Covid-19 survey covers a critical period during which Covid-19 peaked and began to decline, shaping the long-term trajectory of the pandemic in Malawi. Our findings indicate that meaningful involvement of local communities and local leadership can shape the population-wide response to Covid-19 and mitigate the secondary consequences of the pandemic. Consistent with prior research (Kao et al., 2021, Hopman et al., 2020, Nuwagira and Muzoora, 2020, Hargreaves et al., 2020, Chan, 2014, Nyasulu et al., 2021), the key insight of our analysis is that local community leaders can play an important role for the dissemination of public health messages and fostering of appropriate individual behavioral, social and economic responses to the Covid-19 pandemic, and potentially alleviate its impacts on communities such as the ones we study in rural Malawi. Our study emphasizes the importance of community engagement to address population health in economically vulnerable communities. With expected long delays until vaccinations are administrated to the majority of the population in SSA LICs, and ongoing risks of pandemic relapses due to fragile health care systems and more easily spreading SARS-CoV-2 variants, the factors contributing to Malawi’s successful early response provide a template for the required prolonged effort to contain the pandemic in LICs through behavioral change and community mobilization.

2. Background

Malawi represents an important case study to investigate the course of the pandemic and related responses in a sub-Saharan African low-income context. While Malawi shares common hallmarks with other SSA LICs such as wide-spread poverty, fragile health care system, subsistence-based economy, large households with overcrowded living conditions, two important experiences distinguished the country from its counterparts: First, the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic with devastating global reach and health and economic consequences coincided with a presidential election campaign in a heated political climate after the annulment of the prior outcome resulting in circumstances that counteracted widely recommended public health measures such as social distancing and stay-at-home orders. Second, although the country has made significant progress in addressing the challenges associated with the HIV/AIDS epidemic, it continues to have one of the highest HIV/AIDS prevalence rates in the world (CIA, 2020). As a result, in early 2020, the country had to address a new public health crisis while minimizing the negative impacts on the progress made in the past decades to address the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

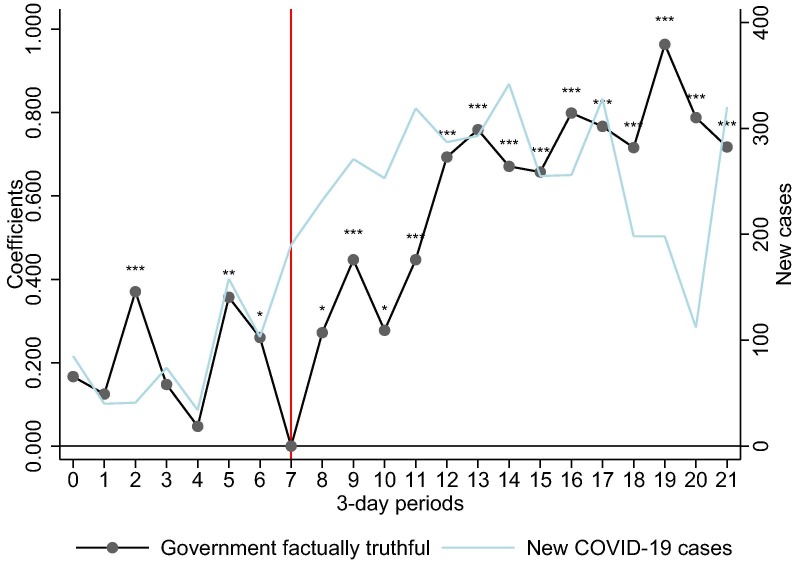

Despite these challenges, Malawi initiated an early response and focused Covid-19 information campaign in February 2020, about two months before the first case was reported in the country. A special cabinet committee on coronavirus was established in March, and a state of emergency was declared shortly thereafter, resulting in the implementation of restrictive social distancing measures (including school closures at all levels, ban on public events and gatherings limited to 100 people, reduction in public transport capacity and border closures). A 21-day national lock-down beginning April 18th, however, was not implemented as a court injunction deemed it unconstitutional and potentially causing a severe nutritional crisis. The subsequent phase of the pandemic coincided with a volatile period of political uncertainty, polarization and a heated election campaign, ultimately leading to a new government on June 28th (BBC News, 2020, Chirwa et al., 2020, Nyasulu et al., 2021). Yet, irrespective of which administration was in place, the government maintained a focus of its Covid-19 campaigns on risk communication and community engagement following a similar approach employed to address the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Public health messages were disseminated via national radio, interactive phone text messages through both phone network suppliers, distribution of printed materials, community awareness meetings, and others. During April–May, mobile van units for the distribution of Covid-19 information and educational materials were mainly employed in the urban areas, expanding nationally only after the election and intensifying in July as the number of Covid-19 cases rose. Despite these governmental efforts, pre-existing mistrust towards the government increased with the reports of the first Covid-19 cases in the country in spring 2020, hampering the attempts to control the pandemic and resulting in widespread concerns about its future trajectory (Nyasulu et al., 2021, Schrad, 2020). Importantly, the government transition in June provided a turn-around in perceptions: once the new government was in place, individuals significantly increased their perceptions of how truthful the government is about Covid-19 (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Pre- and post-election trust in the government’s messaging about Covid-19.

Notes: Change in trust over time is derived using data from the 2020 MLSFH Covid-19 Phone Survey during June 2nd–August 26th, 2020. Black dotted line shows the coefficients associated with time dummy variables (3-day period time) estimated from a regression of survey responses about the government’s truthfulness on a set of control variables (age, gender, schooling, region, p < 0.1, p < 0.05, p < 0.01). Trust in the government was assessed with the question “How factually truthful do you think your country’s government has been about the Covid-19 epidemic? ” with responses measured on a Likert scale ranging from 1=“very untruthful” to 5=“very truthful”. Red vertical line denotes change in government. Superimposed is the Covid-19 incidence data reported by the Ministry of Health (WHO, 2021).

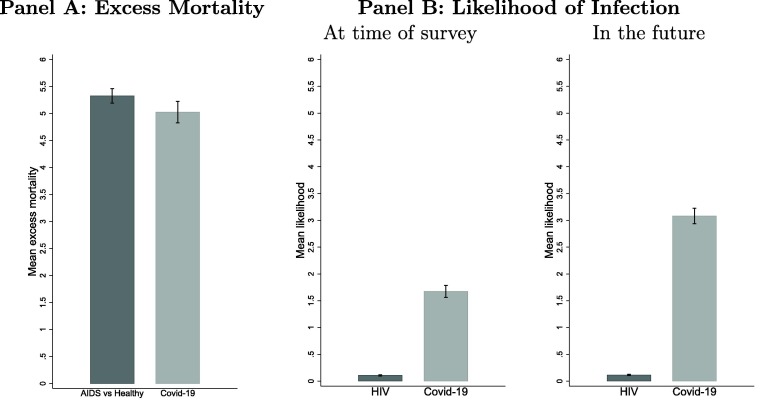

Furthermore, the experience acquired during the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Malawi has not only guided the government in how to implement an early and proactive response to the emergency of the Covid-19 situation, but it also importantly shaped individuals’ and communities’ perceptions and understanding of infection risks, which are crucial for behavioral and public health policy responses to the epidemic and adoption of adequate risk reduction strategies (Ciancio et al., 2020, UNAIDS, 2007, Wilson and Halperin, 2008). Not unlike the early phases of the HIV epidemic, when Covid-19 reached the African continent in early March 2020, it was a novel disease with limited and constantly changing information based mostly on evidence generated in socially and economically very different contexts.1 Comparing perceptions of the impact of both epidemics, our data show that MLSFH respondents had very similar perceived excess mortality risk due to Covid-19 in 2020 and perceived excess mortality risk due to HIV in 2006 (Panel A in Fig. 2 ). This comparison suggests that perceived excess mortality in mid-2020 due to Covid-19, when vaccines were only in the developmental stage, was of similar magnitude as the perceived excess mortality from HIV near the peak of the epidemic in 2006 before the country-wide introduction of antiretroviral treatments (ART). Importantly, these perceptions of high excess Covid-19 mortality in Malawi are in stark contrast to the relatively low perceived excess mortality among US residents early in the pandemic (Ciancio et al., 2020). Hence, a possible important contributor to Malawi’s effective early response to the pandemic and low Covid-19 incidence in 2020 was the widespread perception of Covid-19 as a substantial health and mortality threat, facilitating the adaption of preventive measures and the development of community responses. In addition, participants in the 2020 MLSFH Covid-19 Phone survey estimated a much higher likelihood to be infected with Covid-19 as compared to HIV, an infection that has been widespread in Malawi since the mid-1990s. They also perceived a rapidly increasing risk of Covid-infection as the pandemic unfolded during mid-2020 (Panel B in Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Comparison of Covid-19 (mid-2020) and HIV (2006) Perceptions Panel A: We combine data on the perceived prevalence and perceived mortality to create a measure of excess mortality. Perceived excess mortality for HIV was estimated using the difference between the probability of a hypothetical person dying in 5 years if sick with HIV/AIDS minus the probability of a healthy person dying in 5 years. Perceived excess mortality for Covid-19 was estimated as the probability of dying from Covid-19 conditional on being infected. Panel B: Likelihood of infection with Covid-19 (2020) and HIV (2006) is obtained using a method to elicit subjective probabilistic expectations that has been implemented in the MLSFH since 2006 (Delavande and Kohler, 2009). In the 2020 MLSFH Covid-19 Phone Survey, this question was worded as “Out of 10, tell me the number of peanuts that reflects how likely you think it is that you are infected with coronavirus (Covid-19) now?,” where each peanut represents a 10% chance. An analogous question was asked about the likelihood of being infected with HIV in 2006. “In the future” refers to 3 months for Covid-19 and 2 years for HIV in 2006.

It is important to acknowledge that, despite the relatively low prevalence of Covid-19 infection and death rates, the pandemic has exacerbated economic and other health challenges in SSA LICs including Malawi. Poverty levels in SSA quickly increased due to the pandemic-induced economic downturn. Food insecurity and malnutrition worsened, and children’s immunizations decreased sharply to levels last seen in the 1990s (BMGF, 2020, Egger et al., 2021). Through these secondary impacts, the Covid-19 pandemic has the potential to result in devastating health and social crises even if Covid-19 infections were to remain relatively curtailed (BMGF, 2020, Roberton et al., 2020, Madhi et al., 2020). Malawi, similarly to other SSA LICs, is thus characterized by a striking dichotomy in terms of Covid-19’s impact on society: economic and related social and secondary health implications have been severe (Kanu, 2020, Buonsenso et al., 2020, Burger et al., 2020, Roberton et al., 2020, Egger et al., 2021), while the direct health consequences of the Covid-19 pandemic—Covid-19 infections and related mortality—have been substantially more modest than many observers expected at the beginning of the pandemic (Musa et al., 2021).

3. MLSFH Covid-19 Phone Survey sample characteristics and methods

The MLSFH Covid-19 Phone Survey was conducted during June 2nd—August 26th, 2020 and the target sample included MLSFH respondents, village heads (VHs) and health care providers (HCPs) serving the three MLSFH study areas who were interviewed during 2017–2019 and for whom at least one phone number was available. Out of 3,172 eligible MLSFH respondents (excluding HCPs), 2,262 were successfully interviewed (71% response rate), with the response rate being higher among younger study participants (71%–78% for ages 25–64 years), while only 62% among those age 65–74 years and 47% of those age 75+ years were successfully surveyed. Survey participants were on average 49 years old and about 42% were men. The majority of the respondents were currently married (84.7%), and had finished standard/primary level of schooling (67.8%). About equal proportions of respondents lived in the central (Mchinji) and northern (Rumphi) study districts (35–36%), 25% were located in the southern (Balaka) district, and about 4% were residing in other parts of Malawi as a result of migration out of the three MLSFH study areas (Supplemental Table S1). The survey collected a comprehensive range of information on Covid-19 related topics ranging from knowledge about transmission pathways and behavioral responses to reduce infections, experience of current and past Covid-19 infection symptoms among respondents and the members of their households, impact of the pandemic on economic and social well-being, trust in institutions, village-level responses to the pandemic, to subjective well-being and mental health during the pandemic. Our analyses are primarily based on regression models (linear or ordered probit) that control for gender, age, schooling, region of residence and time (survey day fixed effects to control for systematic difference across days).

Consistent with the narrative of a relatively successful containment of the Covid-19 pandemic in Malawi and other SSA LICs, very few MLSFH respondents reported the experience of any Covid-19-related symptoms at the time of the interview (3.7% had fever, 14.4% had dry cough, 1.9% had shortness of breath, and only 0.3% reported having all these three symptoms simultaneously; very few reported symptoms among household members; Supplemental Table S1). Only four respondents reported having been diagnosed with Covid-19, two of whom based on a coronavirus test. Similarly low prevalence of Covid-19 symptoms in mid-2020 and relatively modest excess mortality due to Covid-19 have also been documented in other rural SSA LICs’ communities (Bamgboye et al., 2020, Banda et al., 2020).

Despite low prevalence, however, the impact of Covid-19 on daily lives and livelihoods was apparent even at this early stage of the pandemic. About 77.1% of respondents had reduced their non-food expenditures (e.g., expenses related to children’s schooling, agriculture, transportation and entertainment), 19.2% had reduced food consumption, 16.3% reduced health expenditures as a result of the pandemic. 55.3% reported an overall worsening economic situation, and 22.2% reported increased food-related worries during the last 12 months. The pandemic also exacerbated concerns about access to health care, including HIV treatment, children’s vaccinations, and treatment for non-communicable diseases (NCDs) (Supplemental Table S1).

Because community leaders (i.e., village heads (VHs)) have eminent roles in all village-related matters, including promoting and monitoring compliance with public health measures and their authority to sanction dissent behavior (Kao et al., 2021), the 2020 MLSFH Covid-19 Phone Survey elicited information from the respondents on the pandemic-related activities of their VHs. In our analysis, we define a VH as “socially active” if MLSFH respondents reported that their VHs had instructed village residents to implement social distancing measures (cancel village meetings, keep distance from other people during activities outside of the household (i.e., when fetching water), stop public works or recreational activities on common playgrounds). We define a VH as “economically active” if he/she had given instructions to create a village fund for emergency purposes or redistribute resources (i.e., food, money, medical supplies) to the most vulnerable residents.

The majority of MLSFH respondents (87%) reported having VHs who were socially active, 25% VHs who were economically active, 24% VHs who were both socially and economically active, and 13% VHs who were neither socially nor economically active. Male respondents were more likely to report that their VHs were socially or economically active, possibly reflecting gender differences in participation in social activities in the village, with men being typically more active and involved in activities outside of their households compared to women in the rural areas in Malawi. Some regional differences in reporting VHs as being socially or economically active are also noticeable. Generally, VHs in the southern district of Balaka were reported to be more socially active compared to VHs in the central region (the district of Mchinji). In contrast, VHs in Balaka and Rumphi were reported to be economically less active compared to their counterparts in Mchinji (Supplemental Table S2). The presidential election is also associated with changes in VHs’ activities. Specifically, respondents reported that their VHs’ in Balaka and Rumphi were more socially active post-election, but this association declined over time in Balaka and the change is not statistically significant in Rumphi (Supplemental Table S3). Similarly, VHs were reported to be more economically active post-election, with this association becoming weaker over time (Supplemental Table S2).

The MLSFH longitudinal information also allows us to investigate whether the past experience with health and economic crises might have facilitated the Covid-19 response 2. Specifically, respondents living in villages that experienced relatively high number of negative economic shocks between 2008 and 2010 were more likely to have a socially active VH more than a decade later (Supplemental Table S4). Hence, the extent to which VHs are socially and economically pro-active during the Covid-19 pandemic is partially related to whether these rural communities have experienced adversity in the past.

4. Results: curtailing the pandemic on a dollar-a-day

4.1. Role of local leadership for behavioral responses to Covid-19

Table 1 reports the associations between village head’s (VH) social and/or economic activities and behavioral responses to Covid-19. The table documents substantively large and statistically significant associations between these activities of VHs and various measures of respondents' Covid-related knowledge and prevention behaviors (wearing or owning face masks, knowledge of symptoms and summary indices of Covid knowledge and risk reduction behaviors2 ). To put these findings in context, it is important to point out that relatively good knowledge about Covid-19 was widespread already in the early phase of the pandemic. 34.2% of respondents were able to list the main infection symptoms (dry cough, fever and difficulties breathing), and 68% knew that infected people can be asymptomatic. Almost all (86.3% to 95.6%) knew the primary transmission pathways. Similarly, protective and social distancing measures were widely known and followed by the survey participants: 70% reported decreased time spent close to people outside of their household, 91% had avoided close contact to other people, and 72.6% reported staying at home to prevent infection (Supplemental Table S1 for additional indicators). Evidence of high Covid-19-related knowledge and social distancing measures has already been documented in Malawi (Fitzpatrick et al., 2021, Banda et al., 2020).

Table 1.

Associations between village head’s (VH) social or economic activities and behavioral responses to Covid-19.

| Wear face masks (1) |

HH owns face masks (2) |

Symptoms score (3) |

Reduce Risk score (4) |

Action score (5) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VH socially active | 0.157*** | 0.153*** | 0.289*** | 0.203*** | 0.745*** |

| (0.029) | (0.028) | (0.089) | (0.065) | (0.095) | |

| VH economically active | 0.115*** | 0.097*** | 0.116 | 0.031 | 0.261*** |

| (0.023) | (0.023) | (0.073) | (0.043) | (0.054) | |

| Observations | 2131 | 2132 | 2125 | 2127 | 2128 |

Note: Estimates are derived from linear regressions with robust standard errors reported in parentheses (). All regressions control for sex, age (dichotomous variables for age 19–34, 35–44, 45–54, 55–64, 65–90) and education (dichotomous variables for “never attended school”, “finished standard” and “finished form and above”), and include region and time (in days) fixed-effects. We define a VH as being “socially active” if he/she had instructed respondents to cancel village meetings, keep distance from other people while fetching water, stop public works or stopping recreational activities, such as soccer on the playground. We define a VH as being “economically active” if he/she had instructed respondents to create a village fund for emergency purposes or redistribute resources (food, money, medical supplies) to the most vulnerable members of the village community. “HH” stands for household. “Symptoms score” (with range 0 to 10) represents the number of Covid-19-related symptoms the respondent can name (1 point assigned for each correct symptom). “Reduce risk score (RR)” (range from 0 to 7) represents the number of appropriate strategies known to respondents that can help reduce the risk of infection such as washing hands, avoiding close contact, covering mouth/nose, avoiding shaking hands, coughing in elbow, but not using herbs and not praying are considered as appropriate behaviors that can help reduce the risk of infection. “Action score (AS)” (ranging from 0 to 6) represents the number of appropriate actions taken by respondents to reduce the risk of infections such as washing hands, avoiding close contacts, staying at home, covering mouth/nose, avoiding shaking hands and coughing in elbow are considered as appropriate actions.

Variation in respondents’ knowledge is importantly related to the local community leadership, and in particular VHs: respondents whose VHs were socially and/or economically active were more likely to own and/or wear face masks, had higher knowledge of Covid-19 symptoms, knew more risk-reducing behaviors for Covid-19 infection (i.e., measured by the Reduce risk score (RR)) and were taking more actions to prevent infections (i.e., as measured by the Action Score (AS)) (Table 1). These associations were particularly large for individuals whose VHs were socially active. Differences between socially and/or economically active VHs also emerge once Covid-19 prevention strategies are classified as “low cost” (e.g., washing hands, avoiding shaking hands, avoiding close contacts with people outside of the household) and “high cost” (staying at home, or decreasing time spent with people outside of the household, with the latter baring high economic costs and being difficult to implement in subsistence agricultural societies) (Supplemental Table S5). Respondents were more likely to implement both low and high costs measures if they had a socially active VH, while having economically active VH is only associated with adopting low costs measures.

4.2. Role of local leadership for mitigating the consequences of Covid-19

Table 2 documents that VHs’ activities were importantly related to how respondents tried to mitigate the economic consequences of the pandemic. Respondents with economically active VHs were more likely to reduce non-food and health expenditures at this early stage of the pandemic, possibly as a result of VHs advising respondents to smooth their consumption and contribute to public funds to help other villagers experiencing economic difficulties (Column 1 in Table 2). There is no association between having an economically active VH and a decrease in food expenditures, while the association exists for socially active VHs (Column 2). This difference possibly reflects the fact that food expenditures are more inelastic and individuals who felt financially more stable thanks to the behavior of their VHs did not have to reduce their food consumption. This pattern is also supported by the negative association between economically active VHs and the increase in food worries over time (Column 5) and in the frequency of eating less food than needed (Column 6) since 2019. These associations are not statistically significant for socially active VHs. Respondents whose VHs were socially or economically active were more likely to borrow money than others (Column 4), suggesting an ability of VH actions to provide stable and less risky environment for individuals to make financial decisions during the pandemic. Having an economically active VHs was negatively associated with respondents’ worries about access to health care during the pandemic (Supplemental Table S6), including HIV testing, pre/post-natal care, vaccinations, access to contraception, while socially active VHs were not systematically associated with mitigating health care related worries (Supplemental Table S6).

Table 2.

Associations between village head’s (VH) social or economic activities and economic consequences.

| Economic consequences |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reduce non food exp. (1) |

Reduce food exp. (2) |

Reduce health exp. (3) |

Borrow money (4) |

Increase food worries (5) |

Increase eaten less food (6) |

Increase no food (7) |

Econ. sit. worse (8) |

|

| VH socially active | 0.061** | 0.047** | 0.035 | 0.083*** | −0.042 | −0.030 | −0.015 | −0.003 |

| (0.029) | (0.023) | (0.021) | (0.027) | (0.039) | (0.036) | (0.027) | (0.032) | |

| VH economically active | 0.066*** | 0.023 | 0.052*** | 0.067*** | −0.082*** | −0.082*** | −0.021 | −0.027 |

| (0.020) | (0.020) | (0.019) | (0.023) | (0.027) | (0.025) | (0.018) | (0.025) | |

| Observations | 2131 | 2132 | 2132 | 2132 | 1151 | 1151 | 1151 | 2130 |

Note: Estimates are derived from linear regressions with robust standard errors reported in parentheses (). All regressions control for sex, age (dichotomous variables for age 19–34, 35–44, 45–54, 55–64, 65–90) and education (dichotomous variables for “never attended school”, “finished standard” and “finished form and above”), and include region and time (in days) fixed-effects. We define a VH as being “socially active” if he has instructed respondents to cancel village meetings, keep distance from other people while fetching water, stop public works or stopping recreational activities, such as soccer on the playground. We define a VH as being “economically active” if he has instructed respondents to creating a village fund for emergency purposes or redistribute resources (food, money, medical supplies) to the most vulnerable members of the village community.

4.3. Trust in institutions and well-being during Covid-19

Respondents expressed relatively high levels of trust and confidence in the two institutions mainly in charge for the country’s response to Covid-19: the government and the health care system as represented by the health care workers. About 80.2% of the respondents trusted that health care workers “do what it takes” to minimize the negative impact of the Covid-19 pandemic, and the majority of respondents (61.8%) thought of the Malawian government as being factually truthful about the pandemic (especially after the elections; Fig. 1).

Table 3 documents that trust in health workers (“HW”) and considering the government (“Gvt”) as being truthful about Covid-19 is associated with higher levels of well-being, better self-reported health and fewer depressive symptoms.3 , 4 Except for depression, these associations persisted when measuring changes between the most recent pre-pandemic measures of well-being or subjective health and the corresponding outcomes measured during 2020 (Table 3). This suggests that respondents who perceived the government as truthful or trusted the health care workers were subjectively enduring the pandemic better than others.

Table 3.

Associations between trust towards institutions (health workers (HW) and the government (Gvt)) and respondent’s wellbeing, self-reported health and mental health (PHQ-9 score)

| Well-being (1) |

Well-being (2) |

Health (3) |

Health (4) |

PHQ-9 score (5) |

PHQ-9 score (6) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distrust in HW | 0.139 | 0.100 | 0.174 | 0.088 | −0.101 | −0.397 |

| (0.099) | (0.130) | (0.107) | (0.120) | (0.334) | (0.408) | |

| Trust in HW | 0.416*** | 0.217** | 0.285*** | 0.181** | −0.871*** | −0.425 |

| (0.071) | (0.092) | (0.069) | (0.082) | (0.228) | (0.268) | |

| Observations | 2130 | 2122 | 2130 | 2122 | 2130 | 2130 |

| Gvt untruthful | 0.108 | 0.132 | 0.243*** | 0.216** | −0.176 | 0.388 |

| (0.075) | (0.090) | (0.075) | (0.088) | (0.231) | (0.290) | |

| Gvt truthful | 0.351*** | 0.321*** | 0.228*** | 0.162** | −0.535*** | 0.014 |

| (0.063) | (0.075) | (0.064) | (0.074) | (0.199) | (0.254) | |

| Observations | 2129 | 2121 | 2129 | 2121 | 2129 | 2129 |

Note: Estimates are derived from ordered probit (columns 1 and 3) and linear (columns 2, 4, 5 and 6) regressions with robust standard errors reported in parentheses (). Our measure of well-being is derived from the question: “I am interested in your general level of well-being or satisfaction with life. How satisfied are you with your life, all things considered?” with possible answers ranging from 1 (“very unsatisfied”) to 5 (“very satisfied”). Subjective health is measured based on the following question: “In general, would you say your health now is”, with possible answers ranging form 1 (“poor”) to 5 (“excellent”). PHQ-9 is a multi-item instrument that is frequently used to determine the presence and severity of depressive symptoms among participants in primary care and in non-clinical settings, and is standard in most population-based surveys Kroenke et al., 2001. All regressions control for sex, age (dichotomous variables for age 19–34, 35–44, 45–54, 55–64, 65–90) and education (dichotomous variables for “never attended school”, “finished standard” and “finished form and above”), and include region and time (in days) fixed-effects. “Health” is self-reported subjective health. “Distrust in HW” combines those who strongly distrust and those who somewhat distrust HW. “Trust in HW” combines those who strongly trust and those who somewhat trust HW. The reference category represents those who neither trust nor distrust. “Government untruthful” combines those who consider the government very untruthful and somewhat untruthful. “Government truthful” combines those who consider the government very truthful and somewhat truthful. The reference category represents those who consider the government to be neither truthful nor untruthful. represents the change in the corresponding outcome variables.

Parsing the results in Table 3 further, our supplemental analyses show that perceiving the government as truthful is associated with lower worries about Covid-19 affecting access to health care (Supplemental Table S7). Only 21.1% of respondents perceived the government as having been untruthful with pandemic-related information, and respondents who rated the government as factually untruthful about Covid-19 were less likely to implement social distancing measures (Supplemental Table S8). Similarly, respondents who distrusted health care workers had lower probability to adopt social distancing measures or preventive health behaviors compared to those who consider health care workers neither truthful nor untruthful with respect to the Covid-19 response (Supplemental Table S9).

Respondents’ trust in institutions (health workers and government) is importantly related to VHs' social and/or economic activities, and Table 4 emphasizes the important role local community leadership can play in building this trust. Specifically, respondents who lived in villages with socially active VHs expressed higher trust in the health care workers to deal with the pandemic. These respondents also perceived the government being truthful with Covid-19 messages. In contrast, this association was not established for economically active VHs.5

Table 4.

Association between village head’s (VH) social/economic activities and trust towards institutions (health workers (HW) and the government (Gvt))

| Trust in HW (1) |

Trust in HW (2) |

Trust in HW (3) |

Gvt truthful (4) |

Gvt truthful (5) |

Gvt truthful (6) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VH socially active | 0.333*** | 0.327*** | 0.263*** | 0.249*** | ||

| (0.089) | (0.090) | (0.078) | (0.080) | |||

| VH economically active | 0.080 | 0.030 | 0.100 | 0.065 | ||

| (0.074) | (0.076) | (0.064) | (0.065) | |||

| Observations | 2130 | 2130 | 2130 | 2129 | 2129 | 2129 |

Note: Estimates are derived from ordered probit regressions with robust standard errors reported in parentheses ( p < 0.1, p < 0.05, p < 0.01). All regressions control for sex, age (dichotomous variables for age 19–34, 35–44, 45–54, 55–64, 65–90) and education (dichotomous variables for “never attended school”, “finished standard” and “finished form and above”), and include region and time (in days) fixed-effects. We define a VH as being “socially active” if he has instructed respondents to cancel village meetings, keep distance from other people while fetching water, stop public works or stopping recreational activities, such as soccer on the playground. We define a VH as being “economically active” if he has instructed respondents to creating a village fund for emergency purposes or redistribute resources (food, money, medical supplies) to the most vulnerable members of the village community. “HW” stands for health care workers. Outcome variables take three possible values: 0 (very untruthful or somewhat untruthful/strongly distrust or somewhat distrust), 1 (neither truthful nor untruthful/neither trust nor distrust) and 2 (very truthful or somewhat truthful/strongly trust or somewhat trust).

5. Summary and discussion

Our analyses aim to illuminate how Malawi, a poor country where more than half of the population lives on less than one dollar a day, succeeded in curtailing the Covid-19 pandemic with relatively low rates of infections and excess mortality during 2020. While multiple mechanisms are likely to contribute to this pattern, including for instance a favorable (young) population age structure, effective behavioral and institutional responses during the early phase of the pandemic almost certainly deserve substantial credit. Utilizing data from the 2020 MLSFH Covid-19 Phone Survey, our research focus on the role of the community leadership for shaping public health and economic responses to the pandemic is motivated by the observation that the timely and decisive handling of the Covid-19 pandemic and a joint continental strategy have been an important factor that may have influenced the pandemic’s trajectory across the African continent in 2020 (Maeda and Nkengasong, 2021, Rosenthal et al., 2020). While most of the Covid-related public and scientific discourse have focused on the functions of governmental and other national institutions to address the pandemic, we explicitly investigate the role of traditional community leaders in promoting the welfare of their citizens during the pandemic. Prior research has emphasized the importance of VHs as “development brokers” (Baldwin, 2016): VHs care about the welfare of their citizens as they are embedded in their community, have a long time horizon and their success depends on the economic development and the approval of their citizens. The role of VHs extends also to health policy: for instance, Walsh et al. (2018) show that VHs in Malawi have an essential role in the success of maternal and child health policies as they are trusted but at the same time feared by women in the villages. Tsai, Morse, and Blair (2020) analyze the role of VHs in fighting the Ebola epidemic in Liberia. They show that information campaigns were successful at increasing adherence and trust in the government thanks to the work of VHs who can be held accountable by their fellow residents. Our study shows that VHs have a similar role in the Covid-19 pandemic.

Focusing on the period June–August 2020 that was critical for shaping the longer-term trajectory of the pandemic in Malawi, we document that this effective behavioral and institutional response to Covid-19 in the country is related to several factors. Notably, despite considerable budgetary restrictions, a presidential election and government transition in mid-2020, the country adopted early in the pandemic a sustained prevention-focused information campaign that emphasized community engagement and dissemination of risk-reduction strategies through multiple channels to ensure a broad reach of the primarily rural population. The employed strategies conceivably build on and reflect lessons learned from addressing the HIV epidemic in the country (Natukunda et al., 2020, Mkandawire et al., 2021). This prevention- and information-focused public health approach is reflected in our data in the fairly high knowledge of Covid-19 disease symptoms, transmission pathways and appropriate behavioral responses reported by our predominantly rural MLSFH respondents in mid-2020. Consistent with prior findings (Banda et al., 2020, Fitzpatrick et al., 2021), participants in the 2020 MLSFH Covid-19 Phone Survey also reported widespread compliance with social distancing and other preventive behaviors. Our analyses extend prior studies by also exploring potential mechanisms. For example, the widespread adaption of preventive behaviors was likely facilitated by the recognition of Covid-19 as a severe health risk that can entail significant mortality risks. Drawing on longitudinal MLSFH data from 2006–2020, comparisons of subjective mortality expectations indicate that study respondents associated an excess mortality risk with Covid-19 that is of similar magnitude of that resulting from HIV/AIDS near the peak of the HIV-epidemic when antiretroviral treatments (ART) were not yet widely available for large fractions of the rural population (Fig. 2). These perceptions of high excess mortality due to Covid-19 in Malawi are in stark contrast to the relatively low perceived excess mortality among US residents early in the pandemic (Ciancio et al., 2020).

Our first set of key findings point to the crucial role of local community leadership (village heads, VHs) to shape their constituents’ behavior and mitigate the impact of Covid-19 in poor rural subsistence communities. Specifically, we show that respondents who live in villages with socially active VHs are more knowledgeable about the pandemic and more likely to adopt preventive health behaviors (Table 1). Importantly, individuals living in villages with economically active VHs were also less likely to report food worries, suggesting a better ability to smooth their food consumption as a response to Covid-19 (Table 2). Our supplemental analyses also show that this variation in the extent to which VHs were active during the early-phase of the Covid-19 pandemic does not seem to be random; on the contrary, respondents who live in villages with relatively high number of negative economic shocks reported between 2008 and 2010 were more likely to have a socially active VH more than a decade later during the Covid-19 pandemic (Supplemental Table S4). This finding is important since it provides evidence that lessons learned from the past, not only from fighting the HIV/AIDS epidemic and other community-spread diseases but also from surviving economic hardship and instability during periods of community-wide adversities, have facilitated effective Covid-19 responses that contribute to reducing the negative consequences of the pandemic among the rural population.

Our second set of key findings highlights the potentially important role that VHs can have in building trust in national institutions such as the health care system and the government during the pandemic (Table 4). This trust can in turn result in better compliance and adoption of public health measures to contain the virus. These aspects are important as broad public support, trust in institutions, and culturally informed and credible public health communication are often emphasized by the public health community as essential components for achieving compliance with governmental orders and public health prevention measures (Lazarus et al., 2020, Freimuth et al., 2014, Siegrist and Zingg, 2014, Blair et al., 2017, Quinn et al., 2013, Shore, 2003)—a finding that is also indicated in our data (Supplemental Tables S8 and S9).

Even more importantly, trust in institutions can also affect key outcomes such as subjective well-being and health: our analyses show that trust in institutions is positively associated with subjective well-being, self-reported health and mental health outcomes during the pandemic, suggesting that trust has a broader impact and plays an important role for individual’s life satisfaction and quality of life during a period of distress and insecurity (Table 3).

The consistent patterns of findings across multiple outcomes and specifications in our analyses underscore the importance of local community leadership for shaping their constituents’ behavior during the pandemic. Covid-19 knowledge and prevention behaviors, health and well-being and trust in institutions are all correlated with VHs’ social and economic activities. As the experience of the United States, another country with a competitive election in 2020, has shown, the presence of distrust and lack of support for Covid-19 prevention measures shared by significant fractions of the population can be an impediment to an effective pandemic response (Ciancio et al., 2020, Soveri et al., 2020). Trust is related to cultural values, norms and beliefs that in Malawi are represented by the authority of the VHs (OECD, 2013, Quinn et al., 2013) and prior research in SSA has shown that local authorities are often seen as more trustful than national institutions and leaders (Kao et al., 2021, Vinck et al., 2019). Our supplemental analyses for example show that local sources of information (coming from local health care personnel, traditional healers, community leaders and/or religious leaders) are more important to implementing social distancing measures than national sources such as newspapers, radio, TV, etc (Supplemental Table S12) and are therefore consistent with these previously established patterns.

In interpreting the above results, it is important to acknowledge that our analyses do not formally establish causation, which is beyond the scope of this paper. Future studies that can exploit exogenous variations in village leadership structures in the form of quasi-experiments can possibly overcome this limitation. In addition, all our outcomes, including Covid-19 knowledge and prevention behavior, are necessarily self-reported, and therefore subject to “social desirability” bias. To the extent that respondents who over-report compliance to COVID-19 social distancing measures are at the same time more likely to report having active VHs, then “social desirability” bias is likely to bias our associations upwards. This limitation is inherent as in-person surveys and direct observation were not feasible during the time-period of this study, and indirect measures (e.g., based on cell phone mobility data) are not viable in the rural Malawi context where cell phone ownership continues to be uncommon (albeit growing). Additional limitation pertains to the fact that participation in the Covid-19 phone survey was not random as we find that younger individuals and those with higher level of schooling were more likely to participate and complete our phone survey (Supplemental Table S13). The associations documented in our analyses may therefore not generalize completely to the overall population. Furthermore, only future research can investigate whether the important role of local leadership remains critical in mitigating the secondary consequences of Covid-19 in the long term.

Notwithstanding the success that we highlight in terms of curtailing Covid-19 infections and mortality in rural Malawi during 2020, the social and economic impacts of the pandemic are severe and possibly long-lasting. For example, a substantial fraction of the MLSFH respondents reduced non-food consumption as a result from Covid-19, and about 61% reported worries about having enough food to eat. For more than half of the interviewed respondents (55%), the economic situation deteriorated compared to the previous year. Worries about access to health care for NCDs and other medical needs such as malaria treatment or HIV/AIDS care were also high. The Covid-19 pandemic resulted in immense challenges and delays to achieve the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (e.g. eradication of communicable diseases (SDG3), promoting social and economic inclusion (SDG 10) (Health, 2020, United Nations, 2015)).

In summary, behavioral and institutional responses to Covid-19 will continue to remain a central hallmark of the response to the Covid-19 pandemic in SSA LICs for the foreseeable future as vaccines are only slowly reaching rural and poor populations (Khan et al., 2021, Nkengasong et al., 2020). The task of effectively addressing the Covid-19 pandemic represents a large-scale collective action problem that involves multiple actors, from national to local levels, from individuals to national institutions (de Andrade & dos Santos, 2020). In the context of the governance constrains in many SSA LICs, the innovation of our study is that we not only describe individual’s behavior during the Covid-19 pandemic in rural areas in a SSA LIC, but we also document how pandemic related behavior is shaped, and focus implicitly on the role of local institutions and community leadership to frame the response to the pandemic. Our study is important as it documents the potential role of local and national stakeholders to implement public health measures, monitor and mitigate the social and economic impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic in these rural communities and protect the welfare of their most vulnerable individuals. Specifically, our findings emphasize the importance of local community leadership for shaping behavioral and economic responses to the pandemic in low-income settings such as Malawi: while the government and health care system are entrusted with defining and prioritizing public health policies during Covid-19, local traditional institutions as represented in our case by the traditional authority of the VHs are indispensable for reinforcing their effective implementation. This involvement of affected communities and their governance during the pandemic is essential, not only in the implementation of official public health measures, but also in the application of countermeasures designed to address the social and economic consequences of the pandemic occurring in rapidly changing health environments.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Iliana V. Kohler: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition. Fabrice Kämpfen: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Alberto Ciancio: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. James Mwera: Project administration. Victor Mwapasa: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Hans-Peter Kohler: Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the generous support for the Mature Adults Cohort of the Malawi Longitudinal Study of Families and Health (MLSFH-MAC) by the Swiss Programme for Research on Global Issues for Development (SNF r4d Grant 400640_160374) and the pilot funding received through the Penn Center for AIDS Research (CFAR), supported by NIAID AI 045008 and the University of Pennsylvania Institute on Aging. We are also grateful for support for the Malawi Longitudinal Study of Families and Health (MLSFH) by the Rockefeller Foundation; the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD, Grant Nos. R01 HD044228, R01 HD053781, R01 HD087391); the National Institute on Aging (NIA, Grant Nos. P30 AG12836, R21 AG053763 and R03-AG-069817); the Boettner Center for Pensions and Retirement Security at the University of Pennsylvania; and the NICHD Population Research Infrastructure Program (Grant Nos. R24 HD-044964), all at the University of Pennsylvania. Iliana V. Kohler also acknowledges the support through NIH rant R03-AG-069817. Fabrice K. was supported by the Swiss National Science foundation (grant number: P2LAP1_187736).

Footnotes

While COVID-19 and HIV/AIDS are very distinct epidemics with non-overlapping transmission pathways, the HIV/AIDS epidemic is an important aspect of the overall context in countries such as Malawi that continue to have a high prevalence of HIV.

“Reduce risk score (RR)”, ranging from 0 to 7, represents the number of appropriate strategies known to respondents that can help reduce the risk of infection such as washing hands, avoiding close contact, covering mouth/nose, avoiding shaking hands, coughing in elbow, not using herbs and not praying. “Action score (AS)” (ranging from 0 to 6) represents the number of appropriate actions taken by respondents to reduce the risk of infections such as washing hands, avoiding close contacts, staying at home, covering mouth/nose, avoiding shaking hands and coughing in elbow.

The reference category for the models in Table 3 corresponds to individuals who neither trust nor distrust health care workers (Panel 1) and those who find the government neither untruthful nor truthful (Panel 2). “Distrust in HW” combines those who strongly distrust and those who somewhat distrust health care workers. “Trust in HW” combines those who strongly trust and those who somewhat trust health care workers. “Government untruthful” combines those who consider the government very untruthful and somewhat untruthful. “Government truthful” combines those who consider the government very truthful and somewhat truthful. This model specification allows for non-linearities in the relationship between the dependent variables and the independent variables.

Our measure of subjective well-being is derived from the question: “I am interested in your general level of well-being or satisfaction with life. How satisfied are you with your life, all things considered?” with possible answers ranging from 1 (“very unsatisfied”) to 5 (“very satisfied”). Subjective health is measured based on the following question: “In general, would you say your health now is”, with possible answers ranging form 1 (“poor”) to 5 (“excellent”). PHQ-9 is a multi-item instrument that is frequently used to determine the presence and severity of depressive symptoms among participants in primary care and in non-clinical settings, and is standard in most population-based surveys (Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, 2001).

These results were robust to using linear (Supplemental Table S10) and ordered logit specifications (Supplemental Table S11).

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, athttps://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2021.105753.

Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Baldwin K. Cambridge University Press; 2016. The paradox of traditional chiefs in democratic Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Bamgboye E.L., Omiye J.A., Afolaranmi O.J., Davids M.R., Tannor E.K., Wadee S., Niang A., Were A., Naicker S. Covid-19 pandemic: Is Africa different? Journal of the National Medical Association. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jnma.2020.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banda, J., Dube, A., Brumfield, S., Amoah, A., Crampin, A., Reniers, G., and Helleringer, S. (2020). Knowledge and behaviors related to the COVID-19 pandemic in Malawi. medRxiv.

- BBC News (2020). Lazarus Chakwera sworn in as Malawi president after historic win. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-53210473. Accessed: 2021-02-27.

- Bearak M., Paquette D. The Washington Post; 2020. The coronavirus is ravaging the world. But life looks almost normal in much of Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Blair R.A., Morse B.S., Tsai L.L. Public health and public trust: Survey evidence from the ebola virus disease epidemic in Liberia. Social Science & Medicine. 2017;172:89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BMGF . Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation Global Report. 2020. Covid-19: A global perspective 2020 goalkeepers report. [Google Scholar]

- Buonsenso D., Cinicola B., Raffaelli F., Sollena P., Iodice F. Social consequences of COVID-19 in a low resource setting in Sierra Leone, West Africa. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2020;97:23–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.05.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger R., Nkonki L., Rensburg R., Smith A., van Schalkwyk C. Examining the unintended health consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic in South Africa. NIDS-CRAM. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Chan M. Ebola virus disease in West Africa—No early end to the outbreak. New England Journal of Medicine. 2014;371(13):1183–1185. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1409859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chirwa G.C., Dulani B., Sithole L., Chunga J.J., Alfonso W., Tengatenga J. Malawi at the crossroads: Does the fear of contracting covid-19 affect the propensity to vote? The European Journal of Development Research. 2020:1–23. doi: 10.1057/s41287-020-00353-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CIA (2020). HIV/AIDS – Adult prevalence rate – Country comparisons. https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/field/hiv-aids-adult-prevalence-rate/country-comparison. Accessed: 2021-07-06.

- Ciancio, A., Kämpfen, F., Kohler, I. V., Bennett, D., Bruine de Bruin, W., Darling, J., Kapteyn, A., Maurer, J., and Kohler, H. -P. (2020). Know your epidemic, know your response: Early perceptions of COVID-19 and self-reported social distancing in the United States. PLOS ONE. Published September 4, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- de Andrade N., dos Santos S.F. Multi-level governance tackling the covid-19 pandemic in china. Brazilian Journal of Public Administration. 2020;55(1) [Google Scholar]

- Delavande A., Kohler H.-P. Subjective expectations in the context of HIV/AIDS in Malawi. Demographic Research. 2009;20(31):817–874. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2009.20.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger D., Miguel E., Warren S.S., Shenoy A., Collins E., Karlan D., Parkerson D., Mobarak A.M., Fink G., Udry C., et al. Falling living standards during the covid-19 crisis: Quantitative evidence from nine developing countries. Science Advances. 2021;7(6):eabe0997. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abe0997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick A.E., Beg S.A., Derksen L.C., Karing A., Kerwin J.T., Lucas A., Reynoso N.O., Squires M. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2021. Health knowledge and non-pharmaceutical interventions during the COVID-19 pandemic in Africa. (Technical report) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freimuth V.S., Musa D., Hilyard K., Quinn S.C., Kim K. Trust during the early stages of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic. Journal of Health Communication. 2014;19(3):321–339. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2013.811323. PMID: 24117390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates B. Responding to Covid-19—A once-in-a-century pandemic? New England Journal of Medicine. 2020;382(18):1677–1679. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2003762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves J., Davey C., Auerbach J., Blanchard J., Bond V., Bonell C., Burgess R., Busza J., Colbourn T., Cowan F., et al. Three lessons for the COVID-19 response from pandemic HIV. The Lancet HIV. 2020;7(5):e309–e311. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(20)30110-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health T.L.P. Will the covid-19 pandemic threaten the SDGs? The Lancet. Public Health. 2020;5(9) doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30189-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopman J., Allegranzi B., Mehtar S. Managing COVID-19 in Low-and Middle-Income Countries. JAMA. 2020;323(16):1549–1550. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneda, T. and Ashford, L. S. (2021). COVID-19 Cases and Deaths in Sub-Saharan Africa appear vastly undercounted. https://www.prb.org/articles/covid-19-cases-and-deaths-in-sub-saharan-africa-appear-vastly-undercounted/. Accessed: 2021-07-24.

- Kanu I.A. Covid-19 and the economy: An African perspective. Journal of African Studies and Sustainable Development. 2020;3(2) [Google Scholar]

- Kao K., Lust E., Dulani B., Ferree K.E., Harris A.S., Metheney E. The ABCs of Covid-19 prevention in Malawi: Authority, benefits, and costs of compliance. World Development. 2021;137 doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan M., Roy P., Matin I., Rabbani M., Chowdhury R. An adaptive governance and health system response for the COVID-19 emergency. World Development. 2021;137 doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler I.V., Bandawe C., Ciancio A., Kämpfen F., Payne C.F., Mwera J., Mkandawire J., Kohler H.-P. Cohort profile: the mature adults cohort of the Malawi Longitudinal Study of Families and Health (MLSFH-MAC) BMJ Open. 2020;10(10) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-038232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler H.-P., Watkins S.C., Behrman J.R., Anglewicz P., Kohler I.V., Thornton R.L., Mkandawire J., Honde H., Hawara A., Chilima B., Bandawe C., Mwapasa V. Cohort profile: The Malawi Longitudinal Study of Families and Health (MLSFH) International Journal of Epidemiology. 2015;44(2):394–404. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K., Spitzer R.L., Williams J.B. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus J.V., Binagwaho A., El-Mohandes A.A.E., Fielding J.E., Larson H.J., Plaséncia A., Andriukaitis V., Ratzan S.C. Keeping governments accountable: The COVID-19 assessment scorecard (COVID-SCORE) Nature Medicine. 2020;26(7):1005–1008. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0950-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madhi, A. S., Gray, E. G., Ismail, N., Izu, A., Mendelson, M., Cassim, N., Stevens, W., and Venter, F. (2020). Covid-19 lockdowns in Low-and Middle-Income Countries: Success against COVID-19 at the price of greater costs. SAMJ: South African Medical Journal 110(8), 724–726. [PubMed]

- Maeda J.M., Nkengasong J.N. The puzzle of the COVID-19 pandemic in Africa. Science. 2021;371(6524):27–28. doi: 10.1126/science.abf8832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbow M., Lell B., Jochems S.P., Cisse B., Mboup S., Dewals B.G., Jaye A., Dieye A., Yazdanbakhsh M. COVID-19 in Africa: Dampening the storm? Science. 2020;369(6504):624–626. doi: 10.1126/science.abd3902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mkandawire P., Cochrane L., Sadaf S. Covid-19 pandemic: Lessons from the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Southern Africa. African Geographical Review. 2021:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee, S. (2021). The Covid conundrum: Why does the pandemic seem to be hitting some countries harder than others? The New Yorker. Published in the print edition of the March 1, 2021.

- Musa H.H., Musa T.H., Musa I.H., Musa I.H., Ranciaro A., Campbell M.C. Addressing Africa’s pandemic puzzle: Perspectives on COVID-19 transmission and mortality in sub-Saharan Africa. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2021;102:483–488. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.09.1456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natukunda J., Sunguya B., Ong K.I.C., Jimba M. Adapting lessons learned from HIV epidemic control to COVID-19 and future outbreaks in sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Global Health Science. 2020;2 [Google Scholar]

- Nkengasong J.N., Ndembi N., Tshangela A., Raji T. Nature Publishing Group; 2020. COVID-19 vaccines: How to ensure Africa has access. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuwagira E., Muzoora C. Is sub-Saharan Africa prepared for COVID-19? Tropical Medicine and Health. 2020;48(1):1–3. doi: 10.1186/s41182-020-00206-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyasulu J.C.Y., Munthali R.J., Nyondo-Mipando A.L., Pandya H., Nyirenda L., Nyasulu P., Manda S. COVID-19 pandemic in Malawi: Did public social-political events gatherings contribute to its first wave local transmission? International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.03.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OECD, O. (2013). Trust in government, policy effectiveness and the governance agenda. Government at a Glance, 2013.

- Quinn S.C., Parmer J., Freimuth V.S., Hilyard K.M., Musa D., Kim K.H. Exploring communication, trust in government, and vaccination intention later in the 2009 H1N1 pandemic: results of a national survey. Biosecurity and bioterrorism: biodefense strategy, practice, and science. 2013;11(2):96–106. doi: 10.1089/bsp.2012.0048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberton T., Carter E.D., Chou V.B., Stegmuller A.R., Jackson B.D., Tam Y., Sawadogo-Lewis T., Walker N. Early estimates of the indirect effects of the covid-19 pandemic on maternal and child mortality in low-income and middle-income countries: A modelling study. The Lancet Global Health. 2020;8(7):e901–e908. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30229-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal P.J., Breman J.G., Djimde A.A., John C.C., Kamya M.R., Leke R.G., Moeti M.R., Nkengasong J., Bausch D.G. Covid-19: Shining the light on Africa. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2020;102(6):1145. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-0380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salyer S.J., Maeda J., Sembuche S., Kebede Y., Tshangela A., Moussif M., Ihekweazu C., Mayet N., Abate E., Ouma A.O., et al. The first and second waves of the COVID-19 pandemic in Africa: A cross-sectional study. The Lancet. 2021;397(10281):1265–1275. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00632-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrad M.L. The Secret to Coronavirus Success Is Trust. Foreign Policy. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Shore D. Communicating in times of uncertainty: The need for trust. Journal of Health Communications. 2003;8(Suppl. 1):13–14. doi: 10.1080/713851977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuchman, M. (2020). Low-and middle-income countries face up to COVID-19. Nat. med. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Siegrist M., Zingg A. The role of public trust during pandemics: Implications for crisis communication. European Psychologist. 2014;19(1):23. [Google Scholar]

- Soveri, A., Karlsson, L. C., Antfolk, J., Lindfelt, M., and Lewandowsky, S. (2020). Unwillingness to engage in behaviors that protect against COVID-19: Conspiracy, trust, reactance, and endorsement of complementary and alternative medicine. PsyArXiv. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- The Lancet (2020). COVID-19 in Africa: no room for complacency. Lancet (London, England), 395(10238), 1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- The Republic of Malawi (2020). National covid-19 preparedness and response plan.

- Tsai L.L., Morse B.S., Blair R.A. Building credibility and cooperation in low-trust settings: persuasion and source accountability in Liberia during the 2014–2015 Ebola crisis. Comparative Political Studies. 2020;53(10–11):1582–1618. [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS Practical guidelines for intensifying HIV prevention: Towards universal access. World Health Organization. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- UNDP (2000). The next frontier – Human development and the Anthropocene.

- United Nations . New York, NY, USA; United Nations: 2015. Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. [Google Scholar]

- Van Zandvoort K., Jarvis C.I., Pearson C.A., Davies N.G., Ratnayake R., Russell T.W., Kucharski A.J., Jit M., Flasche S., Eggo R.M. Response strategies for COVID-19 epidemics in African settings: a mathematical modelling study. BMC Medicine. 2020;18(1):1–19. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-01789-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinck P., Pham P.N., Bindu K.K., Bedford J., Nilles E.J. Institutional trust and misinformation in the response to the 2018–19 Ebola outbreak in North Kivu, DR Congo: A population-based survey. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2019;19(5):529–536. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30063-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker P.G., Whittaker C., Watson O.J., Baguelin M., Winskill P., Hamlet A., Djafaara B.A., Cucunubá Z., Mesa D.O., Green W. The impact of COVID-19 and strategies for mitigation and suppression in Low-Income and Middle-Income Countries. Science. 2020;369(6502):413–422. doi: 10.1126/science.abc0035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh A., Matthews A., Manda-Taylor L., Brugha R., Mwale D., Phiri T., Byrne E. The role of the traditional leader in implementing maternal, newborn and child health policy in Malawi. Health Policy and Planning. 2018;33(8):879–887. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czy059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO (2021). WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard – Malawi. URL: https://covid19.who.int/region/afro/country/mw. [Online; accessed 2021-06-09].

- Wilson D., Halperin D.T. “Know your epidemic, know your response”: A useful approach, if we get it right. The Lancet. 2008;372(9637):423–426. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60883-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worldometers (2020). Covid-19 coronavirus pandemic. Accessed: 2020-09-24.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.