Abstract

Background.

Sexual minority men report high rates of childhood sexual abuse (CSA) and adulthood suicidality. However, mechanisms (e.g., PTSD symptoms) through which CSA might drive suicidality remain unknown.

Objective.

In a prospective cohort of sexual minority men, we examined: (1) associations between CSA and suicidal thoughts and behaviors; (2) prospective associations between CSA-related PTSD symptoms and suicidal ideation; and (3) interpersonal moderators of these associations.

Participants and Setting.

Participants included 6,305 sexual minority men (Mage = 33.2, SD = 11.5; 82.0% gay; 53.5% White) who completed baseline and one-year follow-up at-home online surveys.

Methods.

Bivariate analyses were used to assess baseline demographic and suicidality differences between CSA-exposed participants and non-CSA-exposed participants. Among CSA-exposed participants, multivariable logistic regression analyses were used to regress passive and active suicidal ideation at one-year follow-up on CSA-related PTSD symptoms at baseline. Interactions were examined between CSA-related PTSD symptoms and interpersonal difficulties.

Results.

CSA-exposed sexual minority men reported two-and-a-half times the odds of suicide attempt history compared to non-CSA-exposed men (95% CI = 2.15–2.88; p < 0.001). Among CSA-exposed sexual minority men, CSA-related PTSD symptoms were prospectively associated with passive suicidal ideation (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 1.38; 95% CI = 1.19; 1.61). Regardless of CSA-related PTSD symptom severity, those with lower social support and greater loneliness were at elevated risk of active suicidal ideation at one-year follow-up.

Conclusions.

CSA-related PTSD symptom severity represents a psychological mechanism contributing to CSA-exposed sexual minority men’s elevated suicide risk, particularly among those who lack social support and report loneliness.

Keywords: childhood sexual abuse, sexual minority men, PTSD, suicidality, social support

Introduction

Childhood sexual abuse (CSA; e.g., unwanted or inappropriate sexual contact between a child [anyone younger than 18 years of age] and a person at least 5 years older; Murray et al., 2014) is consistently associated with adulthood suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Studies have shown that adults who report one or more instances where someone perpetrated CSA against them (hereafter, “CSA-exposed”) are between two and three times more likely to attempt suicide than non-CSA-exposed adults (Bedi et al., 2011). Sexual minority men (e.g., those who identify as gay, bisexual, or queer) experience poorer health outcomes, including suicidality, compared to their heterosexual counterparts, and an elevated risk of having a history of CSA exposure with 20% to 50% reporting CSA (compared to 5% to 19% of heterosexual men; Friedman et al., 2011; Lloyd & Operario, 2012; O’Cleirigh et al., 2012; Stoltenborgh et al., 2011; Vaillancourt-Morel et al., 2015), 13% to 55% reporting lifetime suicidal ideation (compared to 11.6% to 14.6% of heterosexual men; Blosnich et al., 2016; Luo et al., 2017; Nystedt et al., 2019), and 11% to 20% reporting lifetime suicidal attempts (compared to 2.9% to 4.3% of heterosexual men; Blosnich et al., 2016; Hottes et al., 2016; Nystedt et al., 2019). While prior research demonstrates a clear link between CSA exposure and adulthood suicidality among sexual minority men (Boroughs et al., 2015; Wilton et al., 2018; Xavier Hall et al., 2020), limited research has examined underlying mental health mechanisms by which CSA exposure might drive suicidality. Identifying pathways through which CSA-exposed sexual minority men’s suicidality develops can inform treatment and prevention interventions for CSA-exposed sexual minority men (Fokas et al., 2020; Mościcki, 2001).

Literature identifying posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as a pathway through which CSA might elevate adulthood suicide risk is reviewed first. Next, evidence demonstrating the extent to which interpersonal difficulties, namely, loneliness, lack of social support, and attachment anxiety, might exacerbate the association between CSA-related PTSD symptoms and suicidality is discussed. Then, a justification for why we modeled passive and active suicidal ideation separately is provided. Finally, this study’s aims are described.

CSA-related PTSD Symptoms and Adulthood Suicide Risk

PTSD symptoms, characterized by persistent and extreme stress and anxiety following a potentially traumatic event (Yehuda et al., 1998), represent one pathway through which CSA might elevate adulthood suicide risk (Stanley et al., 2021). Previous research has shown that individuals who experience more PTSD symptoms are more likely to report suicidality (DeCou & Lynch, 2019). Further, a recent study demonstrated that trauma-exposed adults hospitalized for suicidality were nearly four times as likely to meet PTSD criteria compared to trauma-exposed adults hospitalized for non-suicide-related reasons (Stanley et al., 2021). Among sexual minority men specifically, research has identified elevated rates of comorbid PTSD and suicidality among those exposed to interpersonal violence, including CSA, compared to those not exposed to interpersonal violence (Boroughs et al., 2015; Lloyd & Operario, 2012; Mattera et al., 2018; Pantalone et al., 2010). Also, a recent systematic review highlighted that CSA-exposed sexual minorities, including sexual minority men, are more likely to report PTSD symptoms and suicidality relative to non-CSA-exposed sexual minorities (McGeough & Sterzing, 2018). Despite these findings, it remains unknown whether CSA-related PTSD symptoms represent a mechanism through which CSA may increase adulthood suicidality.

Interpersonal difficulties might exacerbate the association between CSA-related PTSD symptoms and suicidality among sexual minority men. The interpersonal theory of suicide is an empirically validated model that identifies several temporally stable interpersonal-psychological factors (e.g., feelings of burdensomeness, such as loneliness or lack of social support) as key risk factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors (Joiner, 2005; Rogers & Joiner, 2019). Interpersonal difficulties might be particularly relevant among CSA-exposed individuals given that many construct internal “working models” – that is, complex mental representations of the self, the perpetrator, and the quality of the relationship between the two (Bowlby, 1982). Internal working models serve to organize trauma-exposed children’s appraisals regarding the self as unworthy of care and protection and regarding others as rejecting (Ainsworth et al., 2015; Bowlby, 1982). Indeed, these maladaptive internal working models can hinder individuals’ ability to form close relationships following CSA victimization (Riggs, 2010).

Sexual minority men’s interpersonal difficulties have been identified as key risk factors for poor mental health, including suicide (Chang et al., 2020; Poštuvan et al., 2019). Nevertheless, virtually no studies have examined sexual minority men’s interpersonal difficulties (e.g., attachment anxiety, lower social support, loneliness) as moderators of the association between CSA-related PTSD symptoms and suicidality. Documenting sexual minority men’s elevated risk of suicidality associated with CSA-related PTSD symptoms and interpersonal difficulties could clarify subgroups of sexual minority men (e.g., those who lack social support and report PTSD symptoms) who might need targeted violence prevention programming and trauma-focused intervention efforts. Together, these results could inform the allocation of resources to prevent CSA and reduce its long-term mental health consequences among sexual minority men.

Prospective Predictors of Passive and Active Suicidal Ideation

Recently, research has shown that passive suicidal ideation (i.e., the desire to be dead) is comparable to active suicidal ideation (i.e., the desire to kill oneself) in its association with predicting subsequent suicidal behavior (Liu et al., 2020; National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention, 2014). Indeed, a recent systematic review showed that passive suicidal ideation – like active suicidal ideation – is strongly associated with suicide attempts and there also exists preliminary evidence that suggests a large association between passive suicidal ideation and suicide death (Liu et al., 2020). Authors of this systematic review called for longitudinal studies that assess passive and active suicidal ideation separately to “…permit analyses necessary to be able confidently to evaluate the degree to which passive and active ideation may have a shared or different etiology and the common clinical view that passive ideation is not of high clinical concern (Liu et al., 2020, p. 9–10).” To advance the scientific understanding of prospective predictors of passive and active suicidal ideation as well as to inform the clinical utility of our findings, in the current study we modeled passive and active suicidal ideation separately.

The Present Study

The current study aims to extend research on the association between CSA-related PTSD symptoms and suicidality among sexual minority men by first assessing whether CSA-exposed sexual minority men are more likely to report recent suicidal thoughts and behaviors (i.e., suicidal ideation, suicide attempts), compared to non-CSA-exposed sexual minority men. In this study, CSA exposure was defined as experiences of unwanted sexual contact at age 16 years or younger with someone who was at least five years older. We hypothesized that CSA-exposed sexual minority men would be more likely to report suicidal thoughts and behaviors compared to non-CSA-exposed sexual minority men. Second, among CSA-exposed sexual minority men, we sought to longitudinally examine the association between CSA-related PTSD symptoms and suicidal ideation. We hypothesized that CSA-exposed sexual minority men who report more CSA-related PTSD symptoms at baseline would be more likely to report suicidal ideation at one-year follow-up. Third, among CSA-exposed sexual minority men, we sought to examine attachment anxiety, social support, and loneliness as potential moderators of the longitudinal association between CSA-related PTSD symptoms and suicidal ideation. We hypothesized that the risk of suicidal ideation among sexual minority men experiencing CSA-related PTSD symptoms would be greatest for those with higher levels of attachment anxiety, lower levels of social support, and higher levels of loneliness.

Method

Participants and Procedures

Data were taken from the baseline and one-year follow-up at-home online surveys as part of the UNITE (Understanding New In-fections through Targeted Epidemiology) study (see Rendina et al., 2020, 2021 for more details). UNITE is a national longitudinal cohort study examining biopsychosocial predictors of HIV seroconversion among sexual minority men. From November 2017 through September 2018, participants were sampled through targeted advertisements on social media (e.g., Facebook) and sexual networking sites (e.g., Adam4Adam). All potential participants completed a brief online eligibility questionnaire. Eligibility criteria for the UNITE study included (1) being at least 16 years old; (2) currently identifying as male (including transgender men); (3) reporting a sexual minority identity (e.g., gay, bisexual, queer); (4) having a mailing address at which packages could be received in the U.S. or Puerto Rico; (5) being recruited from or reporting geosocial networking application use in the past 6 months; (6) reporting willingness to complete at-home HIV and STI testing; (7) reporting HIV negative or unknown status; (8) allowing their contact information to be shared with distributors for the purposes of HIV/STI testing kit and compensation delivery; and (9) reporting HIV-acquisition risk in the past 6 months (i.e., an STI diagnosis; condomless anal sex [CAS] with a casual male partner, with an HIV-positive or unknown status main partner, or with an HIV-negative main partner who reports CAS with other male partners; or receiving a prescription for postexposure prophylaxis); and (10) reporting not currently using or not consistently using PrEP (i.e., missing ≥ 4 days of dosing in a row or indicating suboptimal adherence; Phillips et al., 2017).

After completing the eligibility screener, participants were prompted to complete a consent form. After consent, participants completed an online survey assessing minority stress and trauma, health variables, and HIV risk. Participants completed at-home sample collection for lab-based HIV testing and were compensated with a $25 Amazon e-gift card. In total, 113,874 sexual minority men completed screening, of whom 26,000 were invited to the study based on the eligibility criteria described above, 10,691 completed the online survey at baseline, and 7,957 fully enrolled in the study after receiving an HIV-negative test result. In our analysis, we included participants who were aged 18 years or older and had complete follow-up data for the outcomes of interest; thus, the final analytic sample included 6,305 participants. The Institutional Review Board of the City University of New York approved all study procedures.

Measures

Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviors.

Suicidal thoughts and behaviors were assessed at baseline and one-year follow-up using the five-item Ask Suicide - Screening Questions (ASQ), a validated screening tool used to assess suicide risk in youth and adults (Horowitz et al., 2012). The ASQ includes four questions assessing suicidal thoughts and behavior and one question assessing self-harm (not utilized in the current analyses). Passive suicidal ideation (i.e., a desire to be dead) was characterized by an affirmative response to either, “In the past few weeks, have you wished you were dead?” or “In the past few weeks, have you felt that you or your family would be better off if you were dead?” Active suicidal ideation (i.e., a desire to kill oneself) was characterized by an affirmative response to, “In the past week, have you been having thoughts about killing yourself?” Suicidal behavior was characterized, at baseline, by an affirmative response to, “Have you ever tried to kill yourself?” and at one-year follow-up by an affirmative response to, “In the past 12 months, have you ever tried to kill yourself?”

Childhood Sexual Abuse (CSA).

CSA exposure was assessed at baseline using a measure assessing whether an individual had ever been “forced or frightened into doing something sexually that you did not want to do.” Participants who endorsed CSA exposure were then asked about the age at which the event occurred and the age and gender of the perpetrator. This measure has been used previously to assess CSA among gay and bisexual men (Paul et al., 2001; Stall et al., 2003). As noted in prior research (e.g., Catania et al., 2008), the validity and reliability of this retrospective measure of CSA is substantiated by cross-sectional and longitudinal studies (Boroughs et al., 2015; Paul et al., 2001). To prevent misclassifying CSA as adolescent or adulthood sexual abuse (i.e., assault occurring at age 17 or over; Rellini & Meston, 2007; Tromovitch & Rind, 2008) and to be consistent with previous CSA research with sexual minority men (Arreola et al., 2009), CSA in the current study was defined as any experience of unwanted sexual contact at age 16 years or younger with a person at least five years older.

CSA-related Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) Symptoms.

CSA-related PTSD symptoms were assessed among participants who reported CSA (as defined above) utilizing an adapted version of the SPAN (Startle, Physiological arousal, Anger, and Numbness), a 4-item scale assessing past-week PTSD symptoms specifically about CSA exposure (Meltzer-Brody et al., 1999; O’Cleirigh et al., 2009). Participants who endorsed CSA exposure were asked, “The following questions refer to symptoms you may have had since this event (i.e., unwanted sexual contact at age 16 years or younger) has happened. Please complete the answers pertaining to symptoms that have occurred in the past week as they relate to this incident.” As such, this scale was limited to CSA for the current study. Items asked participants to rate their symptoms (e.g., “physically upset by reminders of the event,” “unable to have sad or loving feelings”) on a scale of 0 (not at all) to 4 (every day). Items were averaged to create a mean score (Chronbach’s α: 0.83).

Attachment Anxiety.

Attachment anxiety was assessed at baseline utilizing the 6-item Anxiety subscale of the Experiences in Close Relationship Scale (ECR) - Short Form (Wei et al., 2007), which assesses anxious dimensions of romantic relationships (e.g., fear of rejection or abandonment, excessive need for approval, distress at partner unresponsiveness). Participants reported how they generally feel in romantic relationships on a Likert-type scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). Items were summed (Chronbach’s α: 0.77).

Social Support.

Social support was assessed at baseline using the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS; Canty-Mitchell & Zimet, 2000), a 12-item scale assessing the level of social support from family (e.g., “I can talk about my problems with my family”), friends (e.g., “My friends really try to help me”), and significant others (e.g., “There is a special person with whom I can share my joys and sorrows”) on a 6-point Likert-type scale from 1 (very strongly disagree) to 6 (very strongly agree). Items were averaged to create a mean score denoting level of social support with higher scores reflecting more social support. Scale scores in the current sample displayed excellent reliability (Chronbach’s α: 0.94).

Loneliness.

Loneliness was assessed at baseline using the 8-item UCLA Loneliness Scale (Hays & DiMatteo, 1987) which assesses feelings of loneliness (e.g., “How often do you feel isolated from others?”) on a 4-point Likert-type scale from 1 (never) to 4 (often). Items were summed and higher total scores represented greater loneliness (Chronbach’s α: 0.85).

Demographic Covariates.

At baseline, participants reported their birth year and month (used to calculate age in years), race/ethnicity (i.e., Black, Latinx, White and, other), and sexual orientation (i.e., gay, bisexual, queer, straight, and other).

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics including means, standard deviations, and proportions were utilized to characterize the sample’s baseline demographics and suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Bivariate analyses, including t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables, were used to assess baseline demographic and suicidality differences between participants who reported CSA exposure (n = 1,047) versus those who did not report CSA exposure (n = 5,258). Among those who reported CSA exposure, we then used multivariable logistic regression analyses to regress passive and active suicidal ideation, respectively, at one-year follow-up on CSA-related PTSD symptoms reported at baseline, adjusting for age, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, and the outcome at baseline. We did not assess the multivariable association between baseline CSA-related PTSD symptoms and one-year suicidal behavior because relatively few participants reported a suicide attempt at one-year follow-up (n = 40/1047; 3.8%) and we, therefore, did not have adequate power to detect effects. To test interpersonal moderators of the longitudinal association between CSA-related PTSD symptoms and suicidal ideation, in separate multivariable logistic regression models we then examined interactions between CSA-related PTSD symptoms and attachment anxiety, social support, and loneliness. Continuous predictors were mean-centered before computing the interaction terms. Interactions significant at p < 0.05 were graphed to visualize predicted probabilities of the outcome (suicidal ideation = 1) at +/− 1 standard deviation of the mean-centered predictors. We present exponentiated coefficients (adjusted odds ratios [aORs]) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Analyses were conducted in SAS version 9.4.

Results

Baseline Sample Characteristics

Participants were, on average, 33.2 years of age (SD = 11.5), and a large majority of participants identified as gay (82.0%) compared to identifying as bisexual or queer (see Table 1). Most participants identified as White (53.5%) or Latinx (23.2%), with a smaller proportion identifying with another race (12.9%) or as Black (10.4%).

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics by Exposure to Childhood Sexual Abuse (CSA; N = 6,305)

| Baseline Characteristics | Total sample n (%) | Experienced CSA n (%)a | Did not experience CSA n (%) | Chi-Sq or t-statistic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size, n (%) | 6305 (100.0) | 1047 (16.6) | 5258 (83.4) | |

| Age, M [SD] | 33.2 [11.5] | 34.5 [11.2] | 33.0 [11.5] | 3.85*** |

| Sexual orientation | 2.80 | |||

| Gay | 5167 (82.0) | 930 (81.7) | 4328 (83.8) | |

| Bisexual or Queer | 208 (18.3) | 208 (18.3) | 839 (16.2) | |

| Race/ethnicity | 32.8*** | |||

| Black | 657 (10.4) | 126 (12.0) | 531 (10.1) | |

| Latinx | 1461 (23.2) | 300 (28.7) | 1161 (22.1) | |

| White | 3376 (53.5) | 482 (46.0) | 2894 (55.0) | |

| Other | 811 (12.9) | 139 (13.3) | 672 (12.8) | |

| Endorsement of Baseline Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviors | Total sample n (%) | Experienced CSA n (%)a | Did not experience CSA n (%) | Chi-Sq or t-statistic |

| In the past few weeks, have you wished you were dead? | 1047 (16.6) | 229 (21.9) | 818 (15.6) | 25.14*** |

| In the past few weeks, have you felt that you or your family would be better off if you were dead? | 848 (13.5) | 197 (18.8) | 651 (12.4) | 31.06*** |

| In the past week, have you been having thoughts about killing yourself? | 541 (8.6) | 117 (11.2) | 424 (8.1) | 10.77** |

| Have you ever tried to kill yourself? | 1254 (19.9) | 355 (33.9) | 899 (17.1) | 154.8*** |

| Childhood Sexual Abuse (CSA) Characteristics | -- | Experienced CSA n (%)a | -- | -- |

| Age of participant when CSA occurred, M [SD] | 8.8 [3.7] | |||

| Age of perpetrator when CSA occurred, M [SD] | 25.3 [12.1] | |||

| Age difference between participant and perpetrator, M [SD] Perpetrator’s gender | 16.4 [11.3] | |||

| Male | 974 (93.0) | |||

| Female | 73 (7.0) |

CSA = Childhood Sexual Abuse; participant reported at baseline that they experienced unwanted sexual contact at age 16 years or younger with someone who was at least five years older than them.

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01;

p < 0.001

Baseline CSA-related Characteristics and Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviors

In total, 16.6% (n = 1,047) of participants had experienced CSA (see Table 1). Participants who experienced CSA were, on average, 8.8 years old when the CSA occurred (SD = 3.7), and the perpetrators were, on average, 25.3 years old (SD = 12.1) and male (93.0%). At baseline, a substantially higher proportion of participants who had experienced CSA reported suicidal thoughts and behaviors compared to those who had not experienced CSA. Of those who had experienced CSA, 21.9% reported wishing they were dead in the past few weeks (versus 15.6% who did not experience CSA, p < 0.001), 18.8% reported feeling that they or their family would be better off if they were dead in the past few weeks (versus 12.4% who did not experience CSA, p < 0.001), and 11.2% reported thoughts of killing themselves in the past week (versus 8.1% who did not experience CSA, p < 0.01). Notably, at baseline, over one-third (33.9%) of participants who experienced CSA reported a lifetime suicide attempt compared to 17.1% of those who did not experience CSA corresponding to a 2.49 greater odds of suicide attempt among participants who experienced CSA (95% CI = 2.15–2.88; p < 0.001).

Main Effects of CSA-related PTSD Symptoms and Passive and Active Suicidal Ideation

Table 2 displays results from multivariable logistic regression models presenting main and interaction effects. The models on the left-hand side (Models 1a-4a) present associations between baseline CSA-related PTSD symptoms and passive suicidal ideation (i.e., desire to be dead) at one-year follow-up; the models on the right-hand side (Models 1b-4b) present associations between baseline CSA-related PTSD symptoms and active suicidal ideation (i.e., desire to kill oneself) at one-year follow-up.

Table 2.

Partial Results from Logistic Regression Analyses Assessing Childhood Sexual Abuse-related PTSD symptoms (CSA-Related PTSD Symptoms) and Interpersonal Difficulties as Moderators on Passive and Active Suicidal Ideation at One-Year Follow-Up

| Passive suicidal ideation (i.e., desire to be dead) at one-year follow-upa | Active suicidal ideation (i.e., desire to kill oneself) at one-year follow-upb | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Variables | aOR | 95% CI | p-value | aOR | 95% CI | p-value |

| Model 1a | Model 1b | |||||

| CSA-related PTSD symptoms | 1.38*** | 1.18; 1.60 | <0.001 | 1.15 | 0.93; 1.40 | 0.189 |

| Model 2a | Model 2b | |||||

| CSA-related PTSD symptoms | 1.43*** | 1.22; 1.68 | <0.001 | 1.19 | 0.95; 1.46 | 0.131 |

| Attachment Anxiety | 1.07*** | 1.04; 1.11 | <0.001 | 1.06*** | 1.03; 1.11 | <0.001 |

| Interaction of CSA-related PTSD symptoms and Attachment Anxiety | P-value = 0.108 | P-value = 0.283 | ||||

| Model 3a | Model 3b | |||||

| CSA-related PTSD symptoms | 1.39*** | 1.19; 1.65 | <.001 | 1.23ϯ | 0.98; 1.55 | 0.068 |

| Social Support | 0.83** | 0.72; 0.95 | 0.008 | 0.77** | 0.64; 0.94 | 0.009 |

| Interaction of CSA-related PTSD symptoms and Social Support | P-value = 0.075 | P-value = 0.013 | ||||

| Model 4a | Model 4b | |||||

| CSA-related PTSD symptoms | 1.38*** | 1.15; 1.63 | <0.001 | 1.27ϯ | 1.00; 1.63 | 0.053 |

| Loneliness | 1.07*** | 1.03; 1.11 | <0.001 | 1.08** | 1.03; 1.14 | 0.002 |

| Interaction of CSA-related PTSD symptoms and Loneliness | P-value = 0.178 | P-value = 0.013 | ||||

Note. N=1047; Models adjusted for race, age, sexual orientation, and outcome at baseline. aOR = adjusted odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; CSA = Childhood Sexual Abuse; participant reported at baseline that they experienced unwanted sexual contact at age 16 years or younger with someone who was at least five years older than them.

Passive suicidal ideation includes an affirmative response to either: “In the past few weeks, have you wished you were dead?” or “In the past few weeks, have you felt that you or your family would be better off if you were dead?”

Active suicidal ideation includes an affirmative response to: “In the past week, have you been having thoughts about killing yourself?”

p < 0.10;

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01;

p < 0.001

In main effects models (Models 1a & 1b), CSA-related PTSD symptoms were longitudinally associated with passive suicidal ideation such that for a one-point mean elevation in CSA-related PTSD symptoms at baseline, participants demonstrated 38% increased odds of endorsing passive suicidal ideation at one-year follow-up (Model 1a; adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 1.38; 95% CI = 1.19; 1.61). The association between CSA-related PTSD symptoms at baseline and active suicidal ideation at one-year follow-up approached, but did not reach, statistical significance (Model 1b; aOR = 1.15; 95% CI = 0.94; 1.41).

Interactions between CSA-related PTSD Symptoms, Interpersonal Moderators, and Passive and Active Suicidal Ideation

For the outcome of passive suicidal ideation at one-year follow-up, in models assessing potential interactions between baseline CSA-related PTSD symptoms and attachment anxiety (Model 2a), social support (Model 3a), and loneliness (Model 4a), none of the omnibus interaction terms reached significance at p < 0.05 and thus were not probed further. For the outcome of active suicidal ideation, social support (Model 3b) and loneliness (Model 4b), but not attachment anxiety (Model 2b), served as significant moderators of the association between CSA-related PTSD symptoms at baseline and active suicidal ideation at one-year follow-up (omnibus interaction terms both p = 0.013; see Table 2).

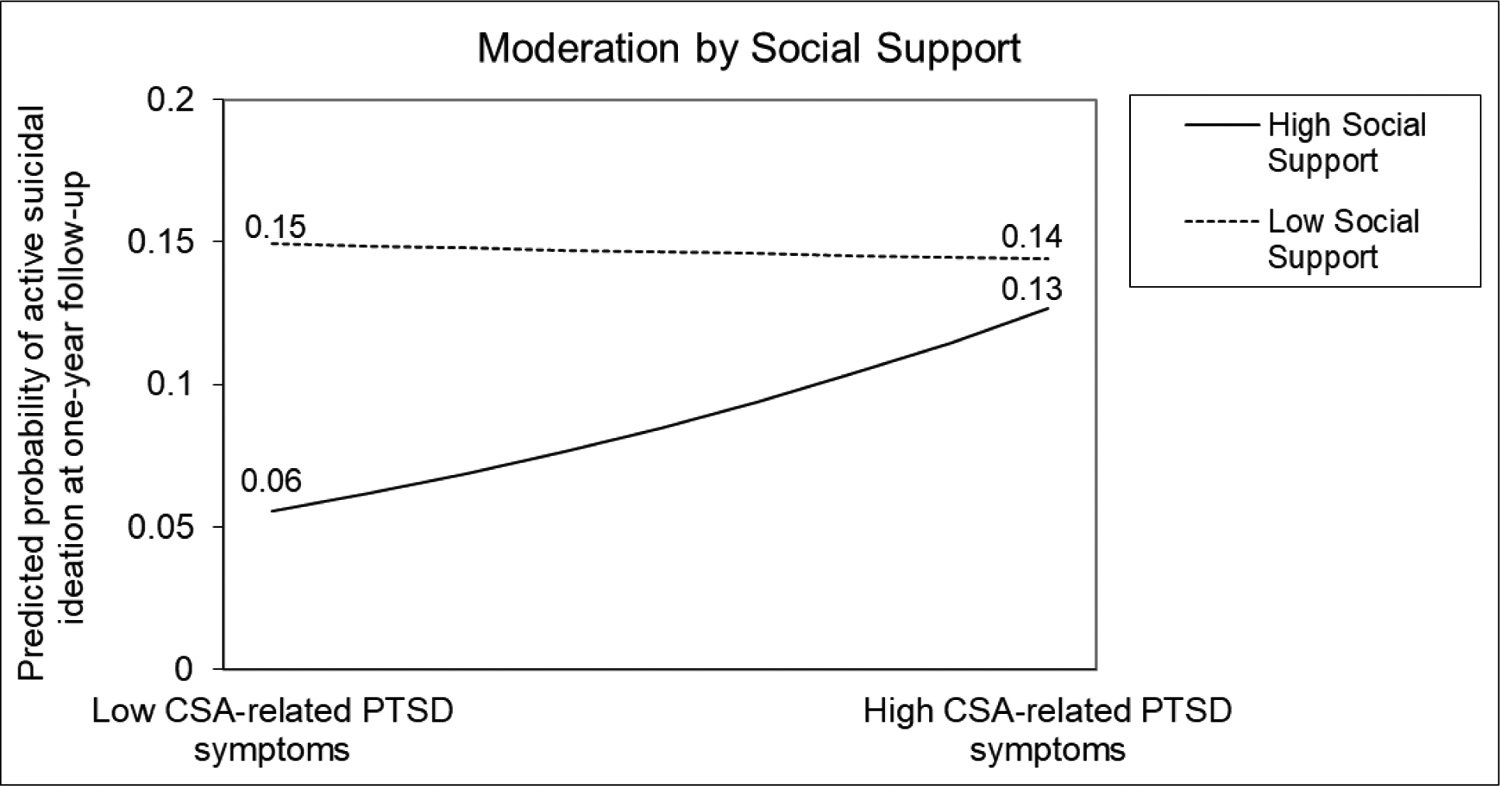

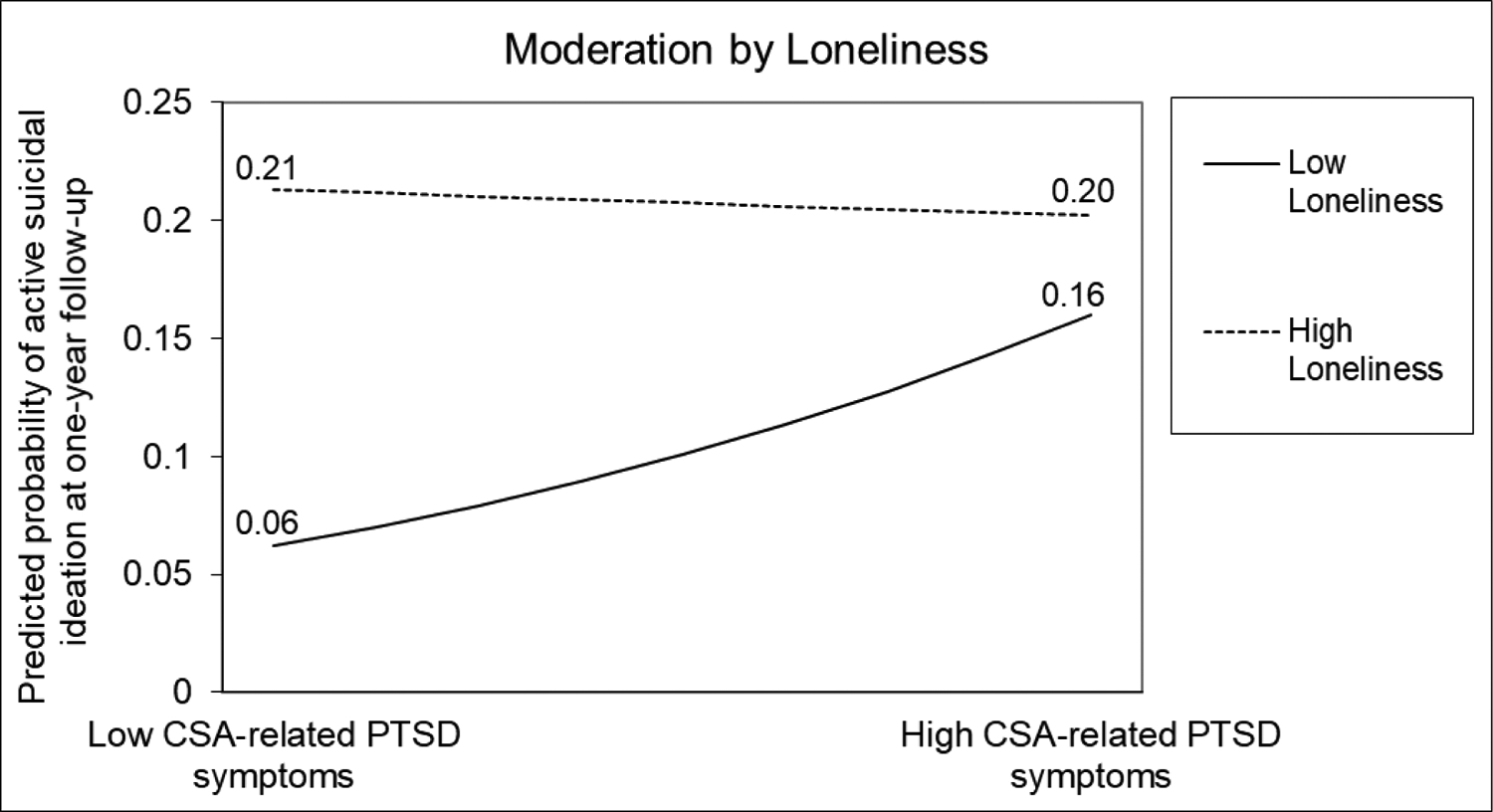

Figures 1 and 2 depict graphical representations of the predicted probability of active suicidal ideation at high and low baseline levels (+/− 1 SD) of CSA-related PTSD symptoms and social support and loneliness, respectively. Both figures demonstrate a similar pattern: at lower levels of social support and higher levels of loneliness, the predicted probability of reporting active suicidal ideation at one-year follow-up is elevated regardless of CSA-related PTSD symptom severity. Further, the only group whose likelihood of endorsing active suicidal ideation is substantially reduced is among those reporting higher social support or lower loneliness and less CSA-related PTSD symptoms.

Figure 1.

CSA-related PTSD symptoms by social support for active suicidal ideation (i.e., desire to kill oneself) at one-year follow-up.

Figure 2.

CSA-related PTSD symptoms by loneliness for active suicidal ideation (i.e., desire to kill oneself) at one-year follow-up.

Discussion

In this study, we found that sexual minority men who were exposed to CSA were more likely to report recent suicidal ideation and suicide attempt history compared to non-CSA-exposed sexual minority men, consistent with our first hypothesis and with the existing literature among the general population (Bedi et al., 2011; DeCou & Lynch, 2019; Ng et al., 2018) and among sexual minority men specifically (Wilton et al., 2018; Xavier Hall et al., 2020). This study also found that among CSA-exposed sexual minority men, CSA-related PTSD symptoms at baseline prospectively predicted passive suicidal ideation, but not active suicidal ideation, at one-year follow-up. The current study also examined whether interpersonal difficulties moderate the longitudinal association between CSA-related PTSD symptoms and suicidal ideation among CSA-exposed sexual minority men. Moderation analyses revealed that social support and loneliness, but not attachment anxiety, moderated the association between CSA-related PTSD symptoms at baseline and active suicidal ideation at one-year follow-up.

Our findings confirm that CSA is a prevalent public health problem among sexual minority men that likely causes significant psychological consequences in adulthood. Similar to previous studies among sexual minority men (e.g., Boroughs et al., 2015; Flynn et al., 2016; Wilton et al., 2018; Xavier Hall et al., 2020), a substantially higher proportion of participants who had experienced CSA reported suicidal thoughts and behaviors (i.e., wishing they were dead, feeling that they or their family would be better off if they were dead, having thoughts of killing themselves, having made a suicide attempt) compared to those who had not experienced CSA. Similar patterns have been observed in general population samples, with a recent meta-analysis demonstrating that CSA-exposed people report 1.9 times the odds of suicide attempts compared to non-CSA-exposed people (Ng et al., 2018). Prior research also suggests that CSA seems to be more strongly associated with suicidality among women compared to men (Bernegger et al., 2015). However, given that we documented a large association between CSA exposure and suicide attempt history, the current study’s results emphasize the importance of assessing suicidal thoughts and behaviors among sexual minority men in particular.

This is among the first studies, to our knowledge, to identify one potential pathway through which CSA-exposed sexual minority men’s elevated risk for suicide develops. Our findings demonstrated that sexual minority men’s CSA-related PTSD symptoms at baseline were associated with passive suicidal ideation at one-year follow-up. This finding extends prior research that has primarily examined the association between PTSD symptoms in general (i.e., not in the context of CSA) and suicidality among sexual minority men (Boroughs et al., 2015; Lloyd & Operario, 2012; Mattera et al., 2018; McGeough & Sterzing, 2018; Pantalone et al., 2010). This study’s findings also revealed that CSA-related PTSD symptoms were not associated with sexual minority men’s active suicidal ideation. The current study’s inconsistent results between CSA-related PTSD symptoms and passive and active suicidal ideation might reflect the extent to which passive suicidal ideation may differentiate from active suicidal ideation in its etiology and supports evidence that passive and active suicidality should be assessed separately (Liu et al., 2020).

We also aimed to examine whether interpersonal difficulties moderated the association between sexual minority men’s CSA-related PTSD symptoms and adulthood suicidality. Consistent with our hypotheses, we found that lower levels of social support and higher levels of loneliness moderated the association between CSA-related PTSD symptoms and active suicidal ideation. Specifically, regardless of their CSA-related PTSD symptom severity, CSA-exposed sexual minority men who reported lower levels of social support and higher levels of loneliness (i.e., more interpersonal difficulties) were at greater risk for active suicidal ideation. These results are aligned with prior research demonstrating that those who have problems with securing positive social support or who feel lonely may have greater difficulty regulating negative or unpleasant affect, thereby increasing the likelihood of utilizing tension-reducing strategies, such as self-harm (Ng et al., 2018; van der Kolk et al., 2005). Extending these findings, our study demonstrated that even among CSA-exposed sexual minority men who reported higher levels of social support and lower levels of loneliness (i.e., less interpersonal difficulties), those reporting more CSA-related PTSD symptoms were more like to endorse active suicidality. These findings offer preliminary evidence that interpersonal difficulties may not necessarily exacerbate the association between CSA-related PTSD symptoms and active suicidality among CSA-exposed sexual minority men. Rather, CSA-exposed sexual minority men’s likelihood of endorsing active suicidal ideation seems to increase in the presence of both lower levels of social support or higher levels of loneliness and more CSA-related PTSD symptoms.

Contrary to our hypotheses, attachment anxiety, social support, and loneliness did not moderate the longitudinal association between CSA-related PTSD symptoms and passive suicidal ideation. That is, regardless of one’s interpersonal functioning, more CSA-related PTSD symptoms might contribute to this population’s elevated risk of passive suicidal ideation. Moreover, the interaction between CSA-related PTSD and attachment anxiety was not significantly associated with active suicidality. As demonstrated by the current study, understanding whether adverse childhood experiences, including CSA, and related PTSD symptoms are differentially associated with passive versus active suicidal ideation is essential for preventing suicidal behavior (Liu et al., 2020), particularly among sexual minority men.

Prevention and Intervention Implications

The World Health Organization recognizes CSA as a preventable public health issue (Mathers et al., 2009). Yet, current CSA prevention efforts are limited (Kenny et al., 2020). For instance, there currently exists no federal legislation requiring school-based CSA prevention programs. Our findings underscore the importance of targeted prevention programs for reducing young boys’ risk of CSA exposure (e.g., promoting community education about CSA, improving parent/caregiver monitoring, implementing policies that foster a zero-tolerance attitude toward CSA; Kenny & Wurtele, 2012). Additionally, CSA prevention efforts that target adults, including family members and leaders of youth-based organizations, at risk of sexually abusing children are needed (Mathers et al., 2009; Rudolph et al., 2018). Given the importance of CSA identification and the benefits of CSA disclosure for youth (Sekhar et al., 2018), school personnel, pediatricians, and other trusted adults might consider improving CSA screening efforts. Moreover, given that attachment styles tend to remain relatively stable during adulthood (Bowlby, 1982), caregivers, mentors, school personnel, and mental health professionals working with CSA-exposed youth could consider bolstering these youths’ capacity to represent others as safe and trustworthy (Boroujerdi et al., 2019).

Informed by the current study’s findings, mental health interventions that target CSA-related PTSD symptoms in addition to interpersonal difficulties could diminish CSA-exposed sexual minority men’s suicidality. Evidence-based trauma-focused mental health interventions, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy for trauma and self-care (CBT-TSC), show promise in reducing sexual minority men’s CSA-related distress (O’Cleirigh et al., 2019, 2021). Nevertheless, it remains unknown whether CBT-TSC might improve this population’s interpersonal functioning or reduce this population’s suicide risk. Future studies might examine whether integrating trauma-focused treatment components (e.g., exposing clients to traumatic memories, helping clients to identify and modify their CSA-related maladaptive thoughts and beliefs; Foa & Rauch, 2004) with affirmative, transdiagnostic CBT interventions for sexual minorities, such as ESTEEM (Effective Skills to Empower Effective Men; Pachankis, 2014), could reduce this population’s CSA-related PTSD, interpersonal difficulties, and suicidality. Also, attention to whether the timing of CSA exposure differentially impacts sexual minority men’s CSA-related PTSD symptoms and suicidality in adulthood could inform future intervention efforts for this population (Xavier Hall et al., 2020). For instance, child-focused interventions might include parent-child dyads and play therapy (Cohen et al., 2004), whereas adolescent-focused interventions might incorporate identity-specific treatment components (e.g., modules focused on identity salience; Sánchez-Meca et al., 2011).

Study Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study is the first, to our knowledge, to document the longitudinal association between sexual minority men’s CSA-related PTSD symptoms and adulthood suicidality; however, several limitations should be considered. While our sample was relatively large, racially and ethnically diverse, and inclusive of sexual minority men with diverse sexual orientations (e.g., queer) and gender identities (e.g., transgender men), eligibility criteria for the UNITE study could limit the generalizability of the present study’s findings. For example, all participants were recruited from or reported geosocial networking application use in the past 6 months, reported willingness to complete at-home HIV and STI testing, reported HIV negative or unknown status, reported HIV-acquisition risk in the past 6 months, and reported not currently using or not consistently using PrEP. As such, whether our study’s findings generalize to other populations of sexual minority men, such as those who report HIV positive status or current PrEP use, remains unknown. The current study also did not account for whether participants were currently enrolled in or had previously received therapy, which represent important covariates for future research.

The upper age cutoff of 16 for CSA exposure in the current study presents a potential limitation as well. For instance, life course theories posit that the timing of adverse childhood experiences, including CSA, could influence long-term mental health consequences associated with childhood maltreatment (Ben-Shlomo & Kuh, 2002; Kuh et al., 2003). As such, mental health comorbidities related to CSA exposure might have a stronger impact on emotion regulation abilities for those abused during childhood compared to those abused during adolescence (Xavier Hall et al., 2020). Also, while participants were asked to report on past-week CSA-related PTSD symptoms, our use of a four-item scale limited the extent to which we could examine CSA-related PTSD diagnosis or symptom clusters related to adulthood suicidality.

Despite this study’s strength of employing a longitudinal design, causal inference is limited by our use of self-reported CSA exposure and related PTSD symptoms, interpersonal difficulties, and suicidality, given known confounds between mental health status and reports of adverse experiences and same-source reporting bias (Dohrenwend et al., 1984; Meyer, 2003). In addition, our use of retrospective self-report obtained in adulthood to collect information regarding CSA exposure may affect the accuracy of reports given that individuals tend to underreport traumatic events (Shaffer et al., 2008). It is also unclear whether participants’ lifetime suicidal attempts reported at baseline occurred prior to or after CSA exposure. As such, future studies should consider employing ecological momentary assessment approaches to examine event-level associations between CSA exposure, PTSD symptoms, and suicidality.

Future research should consider sexual-orientation-specific interpersonal difficulties (e.g., experiencing family rejection, feeling a lack of belonging to the LGBTQ community) that could potentially moderate the longitudinal association between CSA-related PTSD symptoms and suicidal ideation in this sample. Other factors that were not captured in the current study, such as stress appraisals, self-esteem, and emotion regulation strategies, represent important attachment-related mechanisms associated with PTSD (Lim et al., 2020) and suicidality (Boroujerdi et al., 2019; Johnson et al., 2010). As such, future studies should examine these factors in relation to CSA-related PTSD and CSA-exposed sexual minority men’s active suicidal ideation. Future research efforts that aim to improve our evidence-based assessment of CSA, including understanding the moderating effect of the victim’s age, victim’s relationship to the perpetrator, and age difference between participants and perpetrators, could help to clarify the potential long-term impact of CSA exposure on sexual minority men’s mental health risks (Arreola et al., 2008; Boroughs et al., 2015; Flynn et al., 2016).

Conclusion

CSA-exposed individuals are at increased risk of attempting suicide compared to non-CSA-exposed individuals (Bedi et al., 2011). Moreover, sexual minority men are at elevated risk of both CSA and suicidality (Friedman et al., 2011; Hottes et al., 2016; Lloyd & Operario, 2012; Luo et al., 2017; O’Cleirigh et al., 2012). The current study extends prior research on CSA and sexual minority men’s mental health by highlighting the role of CSA-related PTSD symptoms as a contributor to adulthood suicidality in this population. Our findings underscore the need for interventions targeting CSA-related PTSD symptoms in addition to interpersonal difficulties facing CSA-exposed sexual minority men. Such interventions might have the potential to significantly reduce CSA-exposed sexual minority men’s suicidality – a clinical and public health priority.

Acknowledgments:

We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of all our participants within the UNITE study for their time and feedback. We would like to thank all the staff, students, and volunteers who made this study possible, particularly those who worked closely on implementing the study and the safety of participants expressing active suicidal or self-harm ideation: Trinae Adebayo, Paula Bertone, Dr. Cynthia Cabral, Ingrid Camacho, Juan Castiblanco, Jessica Cheng, Jorge Cienfuegos Szalay, Ricardo Despradel, Nicola Forbes, Ruben Jimenez, Scott Jones, Jonathan López-Matos, Raymond Moody, Ore Shalhav, Nico Tavella, and Brian Salfas. We would also like to thank our collaborators, Drs. Carlos Rodriguez-Díaz, Brian Mustanski, and Mark Pandori, as well as the staff at the Alameda County Public Health Laboratory.

Funding Information:

This work was funded by a grant jointly awarded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institute on Mental Health, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute on Child Health and Human Development, and National Institute on Drug Abuse (UG3-AI133674, PI: Rendina). Dr. Jillian R. Scheer acknowledges support from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism under grant K01AA028239. Dr. Kirsty A. Clark acknowledges support from the National Institute on Mental Health under grant K01MH125073. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Interest: There are no conflicts of interest to report regarding this project.

Disclosures: There are no significant financial disclosures relevant to this project.

Ethics Statement: This study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki, that the locally appointed ethics committee has approved the research protocol, and that informed consent has been obtained from the subjects.

Data Availability Statement:

Data is available upon request.

References

- Ainsworth MDS, Blehar MC, Waters E, & Wall SN (2015). Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation (Classic Edition). Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Arreola SG, Neilands TB, & Díaz R (2009). Childhood sexual abuse and the sociocultural context of sexual risk among adult Latino gay and bisexual Men. American Journal of Public Health, 99(Suppl 2), S432–S438. APA PsycInfo. 10.2105/AJPH.2008.138925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arreola SG, Neilands T, Pollack L, Paul J, & Catania J (2008). Childhood sexual experiences and adult health sequelae among gay and bisexual men: Defining childhood sexual abuse. Journal of Sex Research, 45(3), 246–252. 10.1080/00224490802204431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedi S, Nelson EC, Lynskey MT, Cutcheon VVM, Heath AC, Madden PAF, & Martin NG (2011). Risk for suicidal thoughts and behavior after childhood sexual abuse in women and men. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 41(4), 406–415. 10.1111/j.1943-278X.2011.00040.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Shlomo Y, & Kuh D (2002). A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology: Conceptual models, empirical challenges and interdisciplinary perspectives. International Journal of Epidemiology, 31(2), 285–293. 10.1093/intjepid/31.2.285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernegger A, Kienesberger K, Carlberg L, Swoboda P, Ludwig B, Koller R, & Schosser A (2015). Influence of sex on suicidal phenotypes in affective disorder patients with traumatic childhood experiences. PLOS ONE, 10(9), e0137763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boroughs MS, Valentine SE, Ironson GH, Shipherd JC, Safren SA, Taylor SW, Dale SK, Baker JS, Wilner JG, & O’Cleirigh C (2015). Complexity of childhood sexual abuse: Predictors of current PTSD, mood disorders, substance use, and sexual risk behavior among adult men who have sex with men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44(7), 1891–1902. 10.1007/s10508-015-0546-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boroujerdi FG, Kimiaee SA, Yazdi SAA, & Safa M (2019). Attachment style and history of childhood abuse in suicide attempters. Psychiatry Research, 271, 1–7. 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J (1982). Attachment and loss: Retrospect and prospect. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 52(4), 664–678. 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1982.tb01456.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canty-Mitchell J, & Zimet GD (2000). Psychometric properties of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support in urban adolescents. American Journal of Community Psychology, 28(3), 391–400. 10.1023/A:1005109522457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catania JA, Paul J, Osmond D, Folkman S, Pollack L, Canchola J, Chang J, & Neilands T (2008). Mediators of childhood sexual abuse and high-risk sex among men-who-have-sex-with-men. Child Abuse & Neglect, 32(10), 925–940. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.12.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CJ, Fehling KB, & Selby EA (2020). Sexual minority status and psychological risk for suicide attempt: A serial multiple mediation model of social support and emotion regulation. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11. 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JA, Deblinger E, Mannarino AP, & Steer RA (2004). A multisite, randomized controlled trial for children with sexual abuse–related PTSD symptoms. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 43(4), 393–402. 10.1097/00004583-200404000-00005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeCou CR, & Lynch SM (2019). Emotional reactivity, trauma-related distress, and suicidal ideation among adolescent inpatient survivors of sexual abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect, 89, 155–164. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohrenwend BS, Dohrenwend BP, Dodson M, & Shrout PE (1984). Symptoms, hassles, social supports, and life events: Problem of confounded measures. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 93(2), 222–230. 10.1037/0021-843X.93.2.222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn AB, Johnson RM, Bolton S-L, & Mojtabai R (2016). Victimization of lesbian, gay, and bisexual people in childhood: Associations with attempted suicide. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 46(4), 457–470. 10.1111/sltb.12228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, & Rauch SAM (2004). Cognitive Changes During Prolonged Exposure Versus Prolonged Exposure Plus Cognitive Restructuring in Female Assault Survivors With Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72(5), 879–884. 10.1037/0022-006X.72.5.879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fokas K, Robinson CSH, Witkiewitz K, McCrady BS, & Yeater EA (2020). The indirect relationship between interpersonal trauma history and alcohol use via negative cognitions in a multisite alcohol treatment sample. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly, 38(3), 290–305. 10.1080/07347324.2019.1669513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman MS, Marshal MP, Guadamuz TE, Wei C, Wong CF, Saewyc EM, & Stall R (2011). A meta-analysis of disparities in childhood sexual abuse, parental physical abuse, and peer victimization among sexual minority and sexual nonminority individuals. American Journal of Public Health, 101(8), 1481–1494. 10.2105/AJPH.2009.190009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays R, & DiMatteo M (1987). A short-form measure of loneliness. Journal of Personality Assessment, 51, 69–81. 10.1207/s15327752jpa5101_6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz LM, Bridge JA, Teach SJ, Ballard E, Klima J, Rosenstein DL, Wharff EA, Ginnis K, Cannon E, Joshi P, & Pao M (2012). Ask suicide-screening questions (ASQ): A brief instrument for the pediatric emergency department. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 166(12), 1170–1176. 10.1001/archpediatrics.2012.1276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hottes TS, Bogaert L, Rhodes AE, Brennan DJ, & Gesink D (2016). Lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts among sexual minority adults by study sampling strategies: A systematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Public Health, 106(5), e1–e12. 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson J, Gooding PA, Wood AM, & Tarrier N (2010). Resilience as positive coping appraisals: Testing the schematic appraisals model of suicide (SAMS). Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48(3), 179–186. 10.1016/j.brat.2009.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE (2005). Why people die by suicide. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny MC, Helpingstine C, & Long H (2020). College students’ recollections of childhood sexual abuse prevention programs and their potential impact on reduction of sexual victimization. Child Abuse & Neglect, 104, 104486. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny MC, & Wurtele SK (2012). Preventing childhood sexual abuse: An ecological approach. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 21(4), 361–367. 10.1080/10538712.2012.675567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuh D, Ben-Shlomo Y, Lynch J, Hallqvist J, & Power C (2003). Life course epidemiology. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 57(10), 778–783. 10.1136/jech.57.10.778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeb R, Paulozzi L, Melanson C, Simon T, & Arias I (2008). Child maltreatment surveillance: Uniform definitions for public health and recommended data elements, Version 1.0.

- Lim BH, Hodges MA, & Lilly MM (2020). The differential effects of insecure attachment on post-traumatic stress: A systematic review of extant findings and explanatory mechanisms. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 21(5), 1044–1060. 10.1177/1524838018815136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu RT, Bettis AH, & Burkey TA (2020). Characterizing the phenomenology of passive suicidal ideation: A systematic review and meta-analysis of its prevalence, psychiatric comorbidity, correlates, and comparisons with active suicidal ideation. Psychological Medicine, 50(3), 367–383. 10.1017/S003329171900391X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd S, & Operario D (2012). HIV risk among men who have sex with men who have experienced childhood sexual abuse: Systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Education and Prevention, 24(3), 228–241. 10.1521/aeap.2012.24.3.228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Z, Feng T, Fu H, & Yang T (2017). Lifetime prevalence of suicidal ideation among men who have sex with men: A meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry, 17(1), 406. 10.1186/s12888-017-1575-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathers C, Stevens G, & Mascarenhas M (2009). Global health risks: Mortality and burden of disease attributable to selected major risk.

- Mattera B, Levine EC, Martinez O, Muñoz-Laboy M, Hausmann-Stabile C, Bauermeister J, Fernandez MI, Operario D, & Rodriguez-Diaz C (2018). Long-term health outcomes of childhood sexual abuse and peer sexual contact among an urban sample of behaviourally bisexual Latino men. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 20(6), 607–624. 10.1080/13691058.2017.1367420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGeough B, & Sterzing PR (2018). A systematic review of family victimization experiences among sexual minority youth. Journal of Primary Prevention, 39, 491–528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer I (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mościcki EK (2001). Epidemiology of completed and attempted suicide: Toward a framework for prevention. Clinical Neuroscience Research, 1(5), 310–323. 10.1016/S1566-2772(01)00032-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murray LK, Nguyen A, & Cohen JA (2014). Child sexual abuse. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 23(2), 321–337. 10.1016/j.chc.2014.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B, Garofalo R, Herrick A, & Donenberg G (2007). Psychosocial health problems increase risk for HIV among urban young men who have sex with men: Preliminary evidence of a syndemic in need of attention. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 34(1), 37–45. 10.1007/BF02879919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention. (2014). National action alliance for suicide prevention, a prioritized research agenda for suicide prevention: An action plan to save lives. National Institute of Mental Health and the Research Prioritization Task Force, Rockville, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Ng QX, Yong BZJ, Ho CYX, Lim DY, & Yeo W-S (2018). Early life sexual abuse is associated with increased suicide attempts: An update meta-analysis. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 99, 129–141. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Cleirigh C, Batchelder AW, & McKetchnie SM (2021). Contextualizing evidence-based approaches for treating traumatic life experiences and posttraumatic stress responses among sexual minority men. In Lund EM, Burgess C, & Johnson AJ (Eds.), Violence Against LGBTQ+ Persons: Research, Practice, and Advocacy (pp. 149–161). Springer International Publishing. 10.1007/978-3-030-52612-2_11 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Cleirigh C, Safren SA, & Mayer KH (2012). The pervasive effects of childhood sexual abuse: Challenges for improving HIV prevention and treatment interventions. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999), 59(4), 331–334. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31824aed80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Cleirigh C, Safren SA, Taylor SW, Goshe BM, Bedoya CA, Marquez SM, Boroughs MS, & Shipherd JC (2019). Cognitive behavioral therapy for trauma and self-care (CBT-TSC) in men who have sex with men with a history of childhood sexual abuse: A randomized controlled trial. AIDS and Behavior, 23(9), 2421–2431. 10.1007/s10461-019-02482-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE (2014). Uncovering clinical principles and techniques to address minority stress, mental health, and related health risks among gay and bisexual men. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 21(4), 313–330. 10.1111/cpsp.12078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantalone DW, Hessler DM, & Simoni JM (2010). Mental health pathways from interpersonal violence to health-related outcomes in HIV-positive sexual minority men. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78(3), 387–397. 10.1037/a0019307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul JP, Catania J, Pollack L, & Stall R (2001). Understanding childhood sexual abuse as a predictor of sexual risk-taking among men who have sex with men: The Urban Men’s Health Study11The random digit dial (RDD) sample frame was constructed by the Survey Research Center (SRC) of the University of Maryland (UMD), in collaboration with Dr. Graham Kelton at Westat and University of California investigators.☆. Child Abuse & Neglect, 25(4), 557–584. 10.1016/S0145-2134(01)00226-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips T, Brittain K, Mellins CA, Zerbe A, Remien RH, Abrams EJ, Myer L, & Wilson IB (2017). A self-reported adherence measure to screen for elevated HIV viral load in pregnant and postpartum women on antiretroviral therapy. AIDS and Behavior, 21(2), 450–461. 10.1007/s10461-016-1448-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poštuvan V, Podlogar T, Zadravec Šedivy N, & De Leo D (2019). Suicidal behaviour among sexual-minority youth: A review of the role of acceptance and support. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 3(3), 190–198. 10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30400-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers ML, & Joiner TE (2019). Exploring the Temporal Dynamics of the Interpersonal Theory of Suicide Constructs: A Dynamic Systems Modeling Approach. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 87(1), 56–66. 10.1037/ccp0000373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph J, Zimmer-Gembeck MJ, Shanley DC, & Hawkins R (2018). Child sexual abuse prevention opportunities: Parenting, programs, and the reduction of risk. Child Maltreatment, 23(1), 96–106. 10.1177/1077559517729479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Meca J, Rosa-Alcázar AI, & López-Soler C (2011). The psychological treatment of sexual abuse in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 11(1), 67–93. [Google Scholar]

- Scott D, Lonne B, & Higgins D (2016). Public health models for preventing child maltreatment: Applications from the field of injury prevention. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 17(4), 408–419. 10.1177/1524838016658877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekhar DL, Kraschnewski JL, Stuckey HL, Witt PD, Francis EB, Moore GA, Morgan PL, & Noll JG (2018). Opportunities and challenges in screening for childhood sexual abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect, 85, 156–163. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.07.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer A, Huston L, & Egeland B (2008). Identification of child maltreatment using prospective and self-report methodologies: A comparison of maltreatment incidence and relation to later psychopathology. Child Abuse & Neglect, 32(7), 682–692. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.09.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stall R, Mills TC, Williamson J, Hart T, Greenwood G, Paul J, Pollack L, Binson D, Osmond D, & Catania JA (2003). Association of co-occurring psychosocial health problems and increased vulnerability to HIV/AIDS among urban men who have sex with men. American Journal of Public Health, 93(6), 939–942. 10.2105/AJPH.93.6.939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley IH, Marx BP, Keane TM, & Vujanovic AA (2021). PTSD symptoms among trauma-exposed adults admitted to inpatient psychiatry for suicide-related concerns. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 133, 60–66. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Kolk BA, Roth S, Pelcovitz D, Sunday S, & Spinazzola J (2005). Disorders of extreme stress: The empirical foundation of a complex adaptation to trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 18(5), 389–399. 10.1002/jts.20047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei M, Russell DW, Mallinckrodt B, & Vogel DL (2007). The experiences in close relationship Scales(ECR)-short form: Reliability, validity, and factor structure. Journal of Personality Assessment, 88(2), 187–204. 10.1080/00223890701268041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilton L, Chiasson MA, Nandi V, Lelutiu-Weinberger C, Frye V, Hirshfield S, Hoover DR, Downing MJ Jr., Lucy D, Usher D, & Koblin B (2018). Characteristics and correlates of lifetime suicidal thoughts and attempts among young Black men who have sex with men (MSM) and transgender women. Journal of Black Psychology, 44(3), 273–290. 10.1177/0095798418771819 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xavier Hall CD, Moran K, Newcomb ME, & Mustanski B (2020). Age of occurrence and severity of childhood sexual abuse: Impacts on health outcomes in men who have sex with men and transgender women. Journal of Sex Research. APA PsycInfo. 10.1080/00224499.2020.1840497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yehuda R, McFarlane A, & Shalev A (1998). Predicting the development of posttraumatic stress disorder from the acute response to a traumatic event. Biological Psychiatry, 44(12), 1305–1313. 10.1016/S0006-3223(98)00276-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available upon request.