Abstract

At-risk alcohol use is prevalent and increases dysglycemia among people living with human immunodeficiency virus (PLWH). Skeletal muscle (SKM) bioenergetic dysregulation is implicated in dysglycemia and type 2 diabetes. The objective of this study was to determine the relationship between at-risk alcohol, glucose tolerance, and SKM bioenergetic function in PLWH. Thirty-five PLWH (11 females, 24 males, age: 53 ± 9 yr, body mass index: 29.0 ± 6.6 kg/m2) with elevated fasting glucose enrolled in the ALIVE-Ex study provided medical history and alcohol use information [Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT)], then underwent an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) and SKM biopsy. Bioenergetic health and function and mitochondrial volume were measured in isolated myoblasts. Mitochondrial gene expression was measured in SKM. Linear regression adjusting for age, sex, and smoking was performed to examine the relationship between glucose tolerance (2-h glucose post-OGTT), AUDIT, and their interaction with each outcome measure. Negative indicators of bioenergetic health were significantly (P < 0.05) greater with higher 2-h glucose (proton leak) and AUDIT (proton leak, nonmitochondrial oxygen consumption, and bioenergetic health index). Mitochondrial volume was increased with the interaction of higher 2-h glucose and AUDIT. Mitochondrial gene expression decreased with higher 2-h glucose (TFAM, PGC1B, PPARG, MFN1), AUDIT (MFN1, DRP1, MFF), and their interaction (PPARG, PPARD, MFF). Decreased expression of mitochondrial genes were coupled with increased mitochondrial volume and decreased bioenergetic health in SKM of PLWH with higher AUDIT and 2-h glucose. We hypothesize these mechanisms reflect poorer mitochondrial health and may precede overt SKM bioenergetic dysregulation observed in type 2 diabetes.

Keywords: alcohol, human immunodeficiency virus, mitochondria, oxygen consumption, proton leak

INTRODUCTION

About 1.2 million people are currently living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in the United States (1), and antiretroviral therapy (ART) has increased life expectancy among people living with HIV (PLWH) to nearly that of seronegative individuals (2). Accordingly, aging PLWH face multimorbidity including increased risk for insulin resistance (3) that may be complicated by lifestyle factors such as at-risk alcohol use. It is estimated that ∼30% of PLWH have concurrent at-risk alcohol use (4, 5).

At-risk alcohol use has multisystemic adverse consequences (6) and increases the risk for comorbidities among PLWH (7). Using a chronic binge alcohol (CBA) administration paradigm to model at-risk alcohol use and simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) infection to model HIV disease, our laboratory has previously observed that at-risk alcohol decreases the acute insulin response to glucose and disposition index (8). Among PLWH, alcohol use increased risk for dysglycemia (9), was directly related to 2-h glucose levels after an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) (9), and decreased homeostatic model assessment (HOMA) β cell function (10). Together, these findings suggest that at-risk alcohol use dysregulates glucose homeostasis in the context of SIV/HIV infection.

Functional skeletal muscle (SKM) mass is necessary for metabolic health (11, 12) and relies on mitochondrial (13, 14) and glycolytic (15, 16) function for its maintenance. Dysfunction of bioenergetic pathways may mechanistically contribute to the accentuated muscle wasting we have previously observed with CBA in male rhesus macaques with end-stage simian acquired immune deficiency syndrome (SAIDS) (17) and to impaired myoblast regeneration capacity (18). Work from our laboratory showed that CBA administration, SIV infection, and ART treatment decrease myoblast maximal mitochondrial respiration and SKM succinate dehydrogenase activity in male rhesus macaques (19). Furthermore, microarray analyses revealed that CBA decreased expression of glycolytic genes in SKM (20). This preclinical evidence demonstrates impaired SKM bioenergetic health, but this has not yet been translated to PLWH.

Insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2D) is characterized by bioenergetic dysfunction (21, 22), but the relationship between SKM bioenergetic function and glucose tolerance in people without overt T2D is not well established, especially among PLWH. Moreover, alcohol dysregulates mitochondrial and glycolytic metabolism in SKM and myoblasts (muscle precursor cells) (18, 23). However, dose or concentration, duration, and other factors may affect the magnitude and direction of these changes. Because PLWH have greater rates of cardiometabolic comorbidities (24, 25) and prevalence of at-risk alcohol use (4, 5) than the general population, determining the relationship between SKM mitochondrial and glycolytic metabolism with at-risk alcohol and glucose tolerance may be particularly meaningful in this population. Therefore, the present study examined the relationship between at-risk alcohol, glucose tolerance, and myoblast/SKM bioenergetic function in PLWH.

METHODS

Participants

The parent study, Alcohol & Metabolic Comorbidities in PLWH: Evidence Driven Interventions (ALIVE-Ex; NCT03299205, registered October 3, 2017), is divided into two phases; the first phase was carried out to assess the relationship between alcohol use, glucose tolerance, and SKM dysfunction, and the second phase includes an exercise intervention to improve glycemic control and SKM metabolic function in PLWH. The present study includes the 35 in-care PLWH from the Greater New Orleans, LA metropolitan area (24 males, 11 females; age: 53 ± 9 yr; BMI: 29.0 ± 6.6 kg/m2; means ± SD) participating in the first phase of the ALIVE-Ex study who were medically cleared and underwent the muscle biopsy procedure. Participant characteristics and distribution based on Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) score are summarized in Table 1. Recruitment details, demographics of the full cohort in the first phase of the parent study, medical history, alcohol assessment, and oral glucose tolerance test procedure have been previously described (9). Inclusion criteria for the ALIVE-Ex study included fasting plasma glucose 95–124 mg/dL and diagnosed HIV infection. Exclusion criteria included T2D diagnosis, metformin or insulin use, current pregnancy, allergy to lidocaine, any bleeding disorder, or use of blood thinners that would contraindicate muscle biopsy. The study was approved by the Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center Institutional Review Board (IRB #736) and complied with the US Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects (45 CFR, Part 46) and the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Each individual was given an explanation of the study goals, procedures, risks, and benefits and verbally demonstrated understanding before providing written informed consent to participate. The first subject was enrolled on November 20, 2017.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics by Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) score

| AUDIT |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (n = 35) | <5 (n = 21) | ≥5 (n = 14) | P Value | |

| Sex, % (n) | 0.298 | |||

| Female | 31.4 (11) | 38.1 (8) | 21.4 (3) | |

| Male | 68.6 (24) | 61.9 (13) | 78.6 (11) | |

| Race, % (n) | 0.143 | |||

| Black | 79.4 (27) | 74.1 (15) | 92.3 (12) | |

| White | 20.6 (7) | 28.6 (6) | 7.7 (1) | |

| Age, yr (range: 28–69 yr), % (n) | 0.821 | |||

| 20 to <30 yr | 2.9 (1) | 4.8 (1) | 0.0 (0) | |

| 30 to <40 yr | 8.6 (3) | 9.5 (2) | 7.1 (1) | |

| 40 to <50 yr | 22.9 (8) | 19.1 (4) | 28.6 (4) | |

| 50 to <60 yr | 45.7 (16) | 42.9 (9) | 50.0 (7) | |

| 60+ yr | 20.0 (7) | 23.8 (5) | 14.3 (2) | |

| Income, % (n) | 0.139 | |||

| <$20,000 | 91.4 (32) | 85.7(18) | 100.0 (14) | |

| $20,000–$39,999 | 8.6 (3) | 14.3 (3) | 0.0 (0) | |

| Education, % (n) | 0.414 | |||

| <High school | 37.1 (13) | 42.9 (9) | 28.6 (4) | |

| High school graduate | 37.1 (13) | 33.3 (7) | 42.9 (6) | |

| Some college or trade school | 20.0 (7) | 14.3 (3) | 28.6 (4) | |

| 4-yr College/graduate school | 5.7 (2) | 9.5 (2) | 0 (0) | |

| Body mass index (BMI), % (n) | 0.120 | |||

| <18.5 | 2.9 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 7.1 (1) | |

| 18.5–24.9 | 22.9 (8) | 33.3 (7) | 7.1 (1) | |

| 25–29.9 | 42.9 (15) | 28.6 (6) | 64.3 (9) | |

| 30–34.9 | 8.6 (3) | 9.5 (2) | 7.14 (1) | |

| 35+ | 22.9 (8) | 28.6 (6) | 14.3 (2) | |

| Viral load, % (n) | 0.288 | |||

| <200 Copies/mL | 96.0 (24) | 91.7 (11) | 100.0 (13) | |

| 200+ Copies/mL | 4.0 (1) | 8.3 (1) | 0.0 (0) | |

| Smoking status, % (n) | 0.053 | |||

| Nonsmoker | 48.6 (17) | 61.9 (13) | 28.6 (4) | |

| Current smoker | 51.4 (18) | 38.1 (8) | 71.4 (10) | |

| Phosphatidylethanol (PEth), % (n) | 0.011 | |||

| Positive (≥8 ng/mL) | 60.0 (21) | 43.9 (9) | 85.7 (12) | |

| Negative (<8 ng/mL) | 40.0 (14) | 57.1 (12) | 14.3 (2) | |

| Glucose tolerance status, % (n) | 0.037 | |||

| Normal | 57.1 (20) | 71.4 (15) | 35.7 (5) | |

| Impaired | 42.9 (15) | 28.6 (6) | 64.3 (9) | |

ALIVE-Ex study (2018–2020). Bold values indicate P < 0.05.

Oral Glucose Tolerance Test and Blood Collection

After an overnight fast, glucose was measured and verified by capillary blood using a glucometer (True Metrix Pro Blood Glucose Monitoring System, McKesson) during participant screening as previously described (9). Participants with a fasting glucose between 95 and 124 mg/dL returned to the laboratory and underwent an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT). Participants consumed a 75-g bolus of glucose (Trutol, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and rested comfortably in a seated position for 2 h. Blood samples were collected from an antecubital vein using standard venipuncture technique into EDTA-coated tubes before and 2 h after glucose ingestion. Plasma was separated (750 g, 15 min) and stored in several aliquots at −80°C until analysis for glucose in duplicate using an Analox (GM7 Micro-Stat Analyzer, Analox Instruments Ltd., UK). For calculation of gene expression, participants were categorized as having normal (<140 mg/dL) or impaired (140 to <200 mg/dL) glucose tolerance based on their plasma glucose measured 2 h after glucose ingestion. For regression analyses, 2-h glucose levels were considered a continuous measure of glucose tolerance, with a lower value indicating greater tolerance.

Demographics and Alcohol Use Assessment

At the oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) visit, participants provided their demographic information. The AUDIT (26) was used to assess alcohol use. AUDIT < 5 was considered low-risk alcohol use and AUDIT ≥ 5 was considered at-risk alcohol use for gene expression calculations. Continuous AUDIT scores were used for regression analyses. This self-report alcohol use assessment was complemented by phosphatidylethanol (PEth) analysis as a biomarker of recent alcohol use (27). A dried blood spot was prepared from the pre-OGTT blood sample for PEth measurement (United States Drug Testing Laboratories, Inc., Des Plaines, IL). PEth values were used as a continuous variable.

Muscle Biopsy

For the muscle biopsy, participants returned to the laboratory after an overnight fast and were administered a standardized meal of Carnation Breakfast Essential Nutritional Drink (chocolate or vanilla, 240 kcals: 17% from protein, 15% from fat, 68% from carbohydrates; Nestlé, Vevey, Switzerland) 90 min before the muscle biopsy procedure. Biopsy supplies (Temno Biopsy Needle, 14 G, CIA7003702; Basic Biopsy Tray, CIA7005455) were purchased from Central Infusion Alliance (Skokie, IL). A small area of skin on the thigh over the vastus lateralis approximately halfway between the anterior superior iliac spine and the superior lateral patella was cleaned using povidone-iodine swab sticks and local anesthesia was applied (2% lidocaine without epinephrine). Then, a small incision was made through the skin and fascia using a sterile scalpel and a sterile, single-use microbiopsy needle was introduced into the muscle under ultrasound guidance. Six samples (∼25 mg each) were obtained through the same incision site. After completion of the biopsy, pressure was applied to the incision site for 5 min to prevent bleeding, and the site was closed using a sterile bandage. Participants were provided with written instructions, antibiotics, and gauze for care of the biopsy site. A staff nurse followed up with each participant 24–36 h following the biopsy procedure to inquire about the incision site. A portion of the muscle sample (∼75 mg) was quickly cleaned of residual blood, fat, and connective tissue and subsequently flash frozen; a portion (∼50 mg) was retained in sterile culture media for myoblast isolation (described in Myoblast Isolation and Expansion) and a portion (∼25 mg) was immediately fixed in zinc-buffered formalin.

Myoblast Isolation and Expansion

Primary myoblasts were isolated from vastus lateralis muscle samples (∼50 mg) as previously described (18, 28–31). Samples were washed three times in Ham’s F-12 nutrient mixture (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Marlborough, MA), minced, and trypsin digested (0.25% trypsin EDTA diluted 1:4 in Ham’s F-12). Digested muscle tissue was plated for 5 h in growth media [Ham’s F-12 nutrient mixture with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2% l-glutamine, and 2.5 ng/mL recombinant human fibroblast growth factor (R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN)] to allow fibroblasts to adhere to the plate. Supernatant containing muscle tissue and myoblasts was transferred to a fresh plate with growth media, and myoblast colonies were allowed to grow for 1 wk. Thereafter, media was changed every other day. Myoblasts were passaged at 80%–90% confluence and cryopreserved after each passage. Cells were taken to passage 3 (P3) to P4 for use in experiments.

Mitochondrial Function

Mitochondrial oxygen consumption rate (OCR) was measured using a Mito Stress Test (18) and Seahorse XFe96 technology (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Myoblasts at P3 to P4 were seeded on a collagen-coated 96-well Seahorse plate in triplicate at a density of 35,000 cells/well and maintained under standard cell culture conditions (5% CO2, 37°C). After 24 h, growth media was replaced with XF Assay Medium (pH 7.4) with sodium pyruvate (1 mM), L-glutamine (2 mM), and glucose (10 mM) and incubated at 37°C without CO2 for 1 h before measuring myoblast oxygen consumption rate (OCR) with an XFe96 Extracellular Flux Analyzer (Agilent) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Respiratory parameters were assessed using the Mito Stress Test Kit (Agilent) by the sequential addition of oligomycin (1.5 µM), carbonyl cyanide‐p‐trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone (FCCP; 2 μM), and rotenone/antimycin A (0.5 μM). Resulting OCR measurements were normalized to cell count obtained by staining nuclei with Hoescht dye (2 µM; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and visualizing on a BioTek Cytation 1 cell imaging multimode reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT).

Glycolytic Function

To quantify glycolytic function, capacity, and reserve, a Glycolysis Stress Test was performed using Seahorse XFe96 technology (Agilent; 32). Myoblasts were seeded as described in Mitochondrial Function. After 24 h, growth media was replaced with glucose- and pyruvate-free XF Assay Medium (pH 7.4) with L-glutamine (2 mM). Then, myoblasts were incubated at 37°C without CO2 for 1 h before measuring myoblast extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) at baseline and after the sequential addition of glucose (10 mM), oligomycin (1.5 μM), and 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG; 50 mM). Nuclei were stained using Hoescht dye (2 µM; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and visualized on a Cytation 1 cell imaging multimode reader (BioTek) for normalization to cell count.

Mitochondrial Volume Assessment

To quantify functional myoblast mitochondrial volume, MitoTracker Deep Red FM probes (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) were used (33, 34). Myoblasts were incubated with growth media containing MitoTracker Deep Red FM (100 nM) under standard cell culture conditions for 30 min. An unstained control was simultaneously incubated in growth media without MitoTracker. Cells were pelleted, washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and prepared for flow cytometry using the PerFix-nc Kit (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA) according to manufacturer instructions. Briefly, ∼500,000 cells in 100-µL PBS were incubated at room temperature for 15 min with 5 µL of fixative. Then, cells were washed and resuspended in 300 µL final reagent. Ten-thousand events per sample were acquired and excited by a 633-nm wavelength laser line using flow cytometry (BD FACSCanto II, Becton, Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Fluorescence was analyzed using FlowJo software (v. 10.7.1, Becton, Dickinson and Company). Autofluorescence of the unstained control sample was subtracted from the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of each experimental sample for analysis.

RNA Isolation and Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction

To assess expression of mitochondrial genes, total RNA was extracted from flash frozen SKM samples (∼10 mg) using the miRNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was synthesized from 0.15 µg of RNA using the Quantitect reverse transcription kit (Qiagen) according to manufacturer’s instructions and diluted 1:4 in nuclease-free water. Custom primers designed to span exon-exon junctions were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA; Table 2). Final reactions contained cDNA (7.5 ng), primers (500 nM), SyBr green (Quantitect SyBr Green PCR kit, Qiagen), and nuclease-free water to 20 µL. qPCR reactions were carried out in duplicate using a CFX96 thermal cycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) with ribosomal protein S13 (RPS13) as the endogenous control (18, 31, 35, 36). Data were then analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCt method. Results for target genes are calculated as fold change versus the normal glucose tolerance, low-AUDIT group.

Table 2.

List of primers for qPCR analysis (primers from IDT Technologies)

| Gene | Forward Primer | Reverse Primer |

|---|---|---|

| TFAM | CTCCTGAGTAGCTGGGATTA | TCAGCTCCTACAGCAACTA |

| PGC1A | CCACCACTCCTCCTCATAA | ACTGTACCTGGGCTTCTT |

| PGC1B | GGCAACTCCAAGGTCTATTC | ACGAGATGGTTGCCAATG |

| PPARA | GATTGATAAGGGTCCCATGAC | GGATGTCCTAACCCTAACTTTC |

| PPARG | GACTTCTCCAGCATTTCTACTC | GGTACTCTTGAAGTTTCAGGTC |

| PPARD | TGATGCCCAGTACCTCTT | TCTCGGTTTCGGTCTTCT |

| MFN1 | CGATGCACCGATGAAGTAA | GCAAGGGATCAGTGTATGTAG |

| MFN2 | CATGCAGCAGGACATGATAG | TAGGTCATAGTTGAGGGAGAAG |

| DRP1 | GTCCTCGTCCTGCTTTATTT | CATGAACCAGTTCCACACA |

| MFF | AAGTAGCACCAAAC | CCTGCTACAACAATCCTCTC |

| UCP2 | CTCTGGCCTTCACAACATC | GGCAAATGGTATCCCTTCTC |

| UCP3 | ACTATGGACGCCTACAGAA | CTCAGCACAGTTGACGATAG |

| RPS13 | CTTCACAGATCGGTGTAATCC | ATCAGGAGCAAGTCCCTTA |

DRP, dynamin-related protein; MFF, mitochondrial fission factor; MFN, mitofusin; PGC, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPAR) coactivator; RPS13, ribosomal protein S13; TFAM, mitochondrial transcription factor A; UCP, uncoupling protein.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the sample population overall. χ2 and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were used to compare the means of the continuous measures by AUDIT score <5 or ≥5. Spearman’s correlations were used to examine the relationship between alcohol use measures (AUDIT and PEth). As anticipated, AUDIT and PEth were strongly associated (Spearman’s ρ = 0.64, P < 0.001). Spearman’s correlations were used to determine whether a significant relationship existed between sex, age, smoking status, and body mass index (BMI) and each outcome measure of interest. Outcome measures were log transformed before analyses. Multiple linear regression was used to determine the relationships between alcohol use, glucose tolerance, and each outcome measure. Sex, age, and smoking status, but not BMI, were significantly associated with at least one outcome measure; therefore, subsequent regression models were adjusted for age, sex, and smoking status. Four separate regression models were run for each dependent variable: model 1 examined the relationship with glucose tolerance, model 2 examined the relationship with AUDIT, and model 3 examined the relationship with the interaction of glucose tolerance and AUDIT. The fourth model (results not shown) included both AUDIT and glucose tolerance without the interaction term. Analyses were completed using SPSS Statistics software (version 25, IBM, Armonk, NY).

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

Participants were majority male (∼69%), Black (∼79%), middle aged (53 ± 9 yr), and virally suppressed (<200 copies/mL; 96%). Sex, race, age, income, education, BMI, and mean 2-h glucose after OGTT (AUDIT < 5: 121.8 ± 32.9 mg/dL, AUDIT ≥ 5: 140.1 ± 35.5 mg/dL) did not differ between participants with lower (<5) or higher (≥5) AUDIT scores. Although smoking was not different between groups, there was a strong trend for current smoking to be more prevalent among participants with AUDIT ≥ 5 (P = 0.053). A positive PEth test, a measure of recent alcohol use, and 2-h glucose in the “impaired” category were significantly (P < 0.05) more prevalent among participants with AUDIT scores ≥ 5 (Table 1).

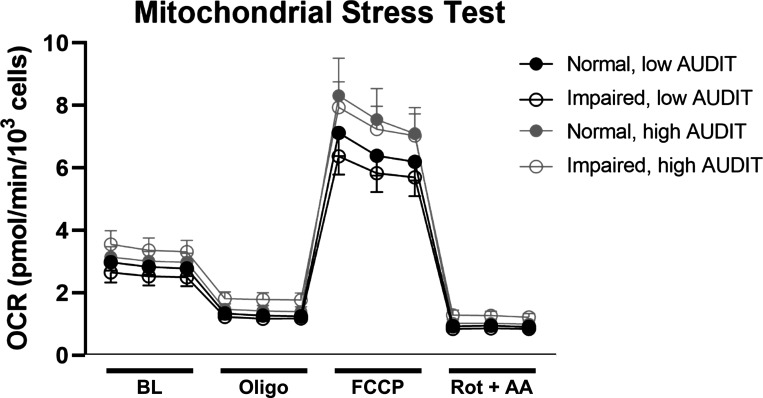

Mitochondrial Function

Proton leak, measured as the difference between OCR after oligomycin treatment and rotenone/antimycin A treatment, was significantly associated (P < 0.05) with higher 2-h glucose levels and higher AUDIT score (Table 3). Increasing nonmitochondrial oxygen consumption, measured as OCR after rotenone/antimycin A treatment, was associated with increasing AUDIT scores, and bioenergetic health index (37) [BHI; (ATP-linked OCR × spare capacity)/(proton leak × nonmitochondrial OCR)] was lower with higher AUDIT scores. No significant associations were observed between 2-h glucose, AUDIT, or their interaction and measures of mitochondrial respiration (basal OCR, spare capacity, ATP-linked OCR, or coupling efficiency). For visualization of OCR throughout the assay, OCR traces during the Mitochondrial Stress Test stratified by glucose tolerance and alcohol use categories are shown in Fig. 1.

Table 3.

Mitochondrial Stress Test parameters

| Basal OCR |

Spare Capacity |

ATP-Linked OCR |

Proton Leak |

Nonmitochondrial OCR |

Coupling Efficiency |

BHI |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | P | β | P | β | P | β | P | β | P | β | P | β | P | |

| Model 1 | ||||||||||||||

| GLUC | 0.18 | 0.88 | 0.15 | 0.44 | 0.09 | 0.67 | 0.38 | 0.05 | 0.35 | 0.06 | −0.27 | 0.17 | −0.22 | 0.24 |

| Model 2 | ||||||||||||||

| AUDIT | 0.09 | 0.64 | 0.02 | 0.92 | −0.03 | 0.89 | 0.41 | 0.02 | 0.35 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.70 | −0.38 | 0.03 |

| Model 3 | ||||||||||||||

| GLUC | 0.02 | 0.95 | 0.08 | 0.78 | 0.04 | 0.9 | −0.06 | 0.81 | −0.02 | 0.92 | −0.42 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.68 |

| AUDIT | −2.46 | 0.49 | −1.43 | 0.66 | −1.32 | 0.71 | −5.11 | 0.09 | −4.37 | 0.15 | −1.08 | 0.74 | 2.89 | 0.36 |

| GLUC × AUDIT | 2.54 | 0.48 | 1.42 | 0.67 | 1.28 | 0.73 | 5.54 | 0.07 | 4.72 | 0.13 | 1.30 | 0.70 | −3.31 | 0.30 |

Linear regression β coefficients of 2-h glucose levels after an oral glucose tolerance test (GLUC; model 1), alcohol use disorders information test (AUDIT) score (model 2), and their interaction (model 3) and mitochondrial stress test parameters measured in myoblasts adjusted by age, sex, and smoking status in people living with HIV (PLWH) in the ALIVE-Ex study (2018–2020). Bold text indicates P < 0.05. BHI, bioenergetic health index; OCR, oxygen consumption rate.

Figure 1.

Mitochondrial Stress Test. Note: Oxygen consumption rate (OCR) normalized to cell count at baseline (BL; measurements 1–3) and after the sequential addition of oligomycin (Oligo; measurements 4–6), carbonyl cyanide‐p‐trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone (FCCP; measurements 7–9), and rotenone/antimycin A (Rot + AA; measurements 10–12) in myoblasts from participants with normal or impaired glucose tolerance and low (<5) or high (≥5) Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) scores. n = 35 participants, means ± SE.

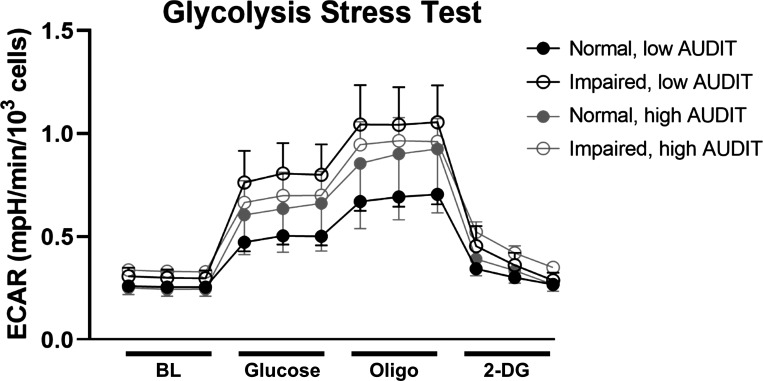

Glycolytic Function

No significant associations were observed between 2-h glucose, AUDIT, and measures of glycolysis (nonglycolytic acidification, glycolysis, glycolytic capacity, and glycolytic reserve; Table 4). There was a nonsignificant trend (P = 0.053) for a negative association between baseline glycolysis and the interaction between 2-h glucose and AUDIT. For visualization of ECAR throughout the assay, ECAR traces during the glycolytic stress test stratified by glucose tolerance and alcohol use categories are shown in Fig. 2.

Table 4.

Glycolysis Stress Test parameters

| Nonglycolytic Acidification |

Glycolysis |

Glycolytic Capacity |

Glycolytic Reserve |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | P | β | P | β | P | β | P | |

| Model 1 | ||||||||

| GLUC | 0.24 | 0.19 | 0.03 | 0.86 | 0.07 | 0.72 | 0.11 | 0.57 |

| Model 2 | ||||||||

| AUDIT | 0.28 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.50 | 0.15 | 0.41 | 0.15 | 0.42 |

| Model 3 | ||||||||

| GLUC | −0.10 | 0.70 | 0.35 | 0.20 | 0.3 | 0.29 | 0.07 | 0.82 |

| AUDIT | −3.90 | 0.19 | 6.38 | 0.05 | 5.09 | 0.12 | 0.29 | 0.94 |

| GLUC × AUDIT | 4.21 | 0.17 | −6.38 | 0.05 | −5.05 | 0.13 | −0.16 | 0.97 |

Linear regression β coefficients of 2-h glucose levels after an oral glucose tolerance test (GLUC; model 1), alcohol use disorders information test (AUDIT) score (model 2), and their interaction (model 3) and glycolysis stress test parameters measured in myoblasts adjusted by age, sex, and smoking status in people living with HIV (PLWH) in the ALIVE-Ex study (2018–2020). Bold text indicates P < 0.05.

Figure 2.

Glycolysis Stress Test. Note: Extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) normalized to cell count at baseline (BL; measurements 1–3) and after the sequential addition of glucose (measurements 4–6), oligomycin (Oligo; measurements 7–9), and 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG; measurements 10–12) in myoblasts from participants with normal or impaired glucose tolerance and low (<5) or high (≥5) Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) scores. n = 35 participants, means ± SE.

Mitochondrial Volume

There was no significant association of mitochondrial volume, measured by MitoTracker, with 2-h glucose or AUDIT independently. However, mitochondrial volume was positively associated with the interaction between 2-h glucose and AUDIT (Table 5).

Table 5.

Mitochondrial volume

| Mitochondrial Volume |

||

|---|---|---|

| β | P | |

| Model 1 | ||

| GLUC | 0.23 | 0.26 |

| Model 2 | ||

| AUDIT | 0.17 | 0.36 |

| Model 3 | ||

| GLUC | −0.25 | 0.37 |

| AUDIT | −7.27 | 0.03 |

| GLUC × AUDIT | 7.53 | 0.03 |

Linear regression β coefficients of 2-h glucose levels after an oral glucose tolerance test (GLUC, model 1), alcohol use disorder information test (AUDIT) score (model 2), and their interaction (model 3) and mitochondrial volume (MitoTracker mean fluorescence intensity) measured in myoblasts adjusted by age, sex, and smoking status in people living with HIV (PLWH) in the ALIVE-Ex study (2018–2020). Bold text indicates P < 0.05.

SKM Mitochondrial Gene Expression

Expression of genes controlling mitochondrial biogenesis [mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM) and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPAR) coactivator (PGC)1B] was significantly decreased with higher 2-h glucose (Table 6). Expression of genes associated with lipid handling was significantly decreased with higher 2-h glucose (PPARG) and with the interaction between 2-h glucose and AUDIT (PPARG and PPARD). Expression of genes controlling mitochondrial dynamics was significantly decreased with higher 2-h glucose [mitofusin (MFN)1] and AUDIT [MFN1, dynamin-related protein (DRP)1, and mitochondrial fission factor (MFF)]. There was a statistically significant interaction between 2-h glucose and AUDIT (MFF). No significant relationship was observed between 2-h glucose, AUDIT, and PGC1A, PPARA, MFN2, or gene expression of uncoupling proteins UCP2 and UCP3.

Table 6.

Skeletal muscle mitochondrial gene expression

|

TFAM

|

PGC1A

|

PGC1B

|

PPARA

|

PPARG

|

PPARD

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | P | β | P | β | P | β | P | β | P | β | P | |

| Model 1 | ||||||||||||

| GLUC | −0.46 | 0.01 | −0.27 | 0.15 | −0.41 | 0.01 | −0.26 | 0.11 | −0.37 | 0.04 | −0.18 | 0.37 |

| Model 2 | ||||||||||||

| AUDIT | −0.14 | 0.46 | −0.03 | 0.87 | −0.09 | 0.57 | −0.06 | 0.68 | −0.30 | 0.08 | −0.21 | 0.26 |

| Model 3 | ||||||||||||

| GLUC | −0.52 | 0.07 | −0.26 | 0.37 | −0.28 | 0.21 | −0.24 | 0.32 | 0.13 | 0.59 | 0.32 | 0.24 |

| AUDIT | −0.7 | 0.83 | 0.92 | 0.78 | 2.82 | 0.28 | 0.58 | 0.84 | 7.05 | 0.02 | 7.23 | 0.03 |

| GLUC × AUDIT | 0.75 | 0.82 | −0.86 | 0.80 | −2.81 | 0.29 | −0.56 | 0.85 | −7.40 | 0.01 | −7.56 | 0.03 |

|

MFN1

|

MFN2

|

DRP1

|

MFF

|

UCP2

|

UCP3

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | P | β | P | β | P | β | P | β | P | β | P | |

| Model 1 | ||||||||||||

| GLUC | −0.46 | 0.02 | 0.1 | 0.64 | −0.26 | 0.19 | −0.03 | 0.87 | −0.04 | 0.85 | −0.24 | 0.20 |

| Model 2 | ||||||||||||

| AUDIT | −0.43 | 0.02 | −0.23 | 0.22 | −0.55 | <0.01 | −0.47 | <0.01 | −0.03 | 0.87 | 0.08 | 0.64 |

| Model 3 | ||||||||||||

| GLUC | −0.22 | 0.42 | 0.41 | 0.17 | −0.01 | 0.98 | 0.58 | 0.03 | 0.34 | 0.23 | 0.01 | >0.99 |

| AUDIT | 1.57 | 0.61 | 2.89 | 0.40 | 0.14 | 0.96 | 6.23 | 0.04 | 6.37 | 0.06 | 5.79 | 0.07 |

| GLUC × AUDIT | −1.93 | 0.55 | −3.26 | 0.35 | −0.68 | 0.82 | −6.91 | 0.02 | −6.53 | 0.06 | −5.71 | 0.08 |

Linear regression β coefficients of 2-h glucose levels after an oral glucose tolerance test (GLUC; model 1), alcohol use disorders information test (AUDIT) score (model 2), and their interaction (model 3) and expression of mitochondrial genes measured in skeletal muscle adjusted by age, sex, and smoking status in people living with HIV (PLWH) in the ALIVE-Ex study (2018–2020). Bold text indicates P < 0.05. DRP: dynamin-related protein; MFF, mitochondrial fission factor; MFN, mitofusin; PPAR, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor; PGC, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator; TFAM, mitochondrial transcription factor A; UCP, uncoupling protein.

DISCUSSION

Skeletal muscle tissue plays a key role in whole body metabolism and glucose homeostasis; therefore, factors that influence SKM energetic health have multisystemic implications. In the present study, there was a negative interaction of 2-h glucose level and AUDIT score with SKM expression of genes controlling mitochondrial fission and lipid handling and this was associated with greater myoblast mitochondrial volume. Bioenergetic health index (BHI) accounts for positive (ATP-linked oxygen consumption and spare capacity) and negative (proton leak and nonmitochondrial oxygen consumption) mitochondrial respiratory parameters (37). In myoblasts from PLWH, BHI was lower with increasing AUDIT score. Increased 2-h glucose and AUDIT were independently related to decreased SKM expression of genes regulating mitochondrial biogenesis and dynamics. Overall, our study provides evidence that the mitochondrial profile in PLWH is dysregulated with increased 2-h glucose and at-risk alcohol use when adjusted for age, sex, and smoking status.

We previously observed decreased glycolytic function and, conversely, increased maximal mitochondrial respiration in myoblasts cultured with 50 mM ethanol, a physiologically relevant dose (18). In contrast, myoblasts isolated from SKM of chronic binge alcohol-administered, SIV-infected male rhesus macaques had decreased maximal mitochondrial respiration compared with controls (19). In the current study, proton leak-associated and nonmitochondrial oxygen consumption were higher and overall bioenergetic health lower with AUDIT in myoblasts from PLWH, with no statistically significant changes in other bioenergetics measures such as basal, maximal, or ATP-linked oxygen consumption. There may be a threshold of intensity of alcohol exposure (concentration × frequency) required to produce overt bioenergetic deficits. Furthermore, whereas samples from our previous preclinical studies were derived from animals fed high-quality, healthy diets, with normal fasting glycemia, participants in the present study had elevated fasting glucose (95–124 mg/dL) and habitual diets were not controlled. Therefore, it is possible that differences may be elucidated with the inclusion of more participants at either end of the fasting glucose tolerance spectrum, from normal fasting glucose to fasting hyperglycemia indicative of T2D.

Increased mitochondrial content is often an adaptive process (e.g., in response to exercise) that can increase aerobic energy production capacity via increased content of electron transport chain complexes on the inner mitochondrial membrane (38). This adaptive increase is driven by increased expression of master regulators of mitochondrial biogenesis (e.g., PGC1α and PGC1β) along with transcription of the mitochondrial genome by TFAM (39, 40). In the present study, greater mitochondrial volume was not driven by increased expression of regulators of mitochondrial biogenesis as gene expression of PGC1B and TFAM was decreased with lower glucose tolerance (higher 2-h glucose). Moreover, the greater mitochondrial volume did not coincide with improved mitochondrial function. There was no concomitant increase in gene expression of uncoupling proteins, changes in ATP-linked oxygen consumption, or decreased maximal oxygen consumption. Rather, it appears that the observed increase in mitochondrial content may reflect accumulation of suboptimal portions of the mitochondrial network that would typically have been eliminated through mitochondrial fission and subsequent mitophagy under normal physiological conditions. Accordingly, bioenergetic health was decreased with AUDIT, and proton leak, a negative indicator of bioenergetic health (37), was increased with lower glucose tolerance. These data suggest that the overall health of the mitochondrial network is compromised in PLWH with lower glucose tolerance and at-risk alcohol use.

Mitochondrial dynamics maintain quality and morphology of the mitochondrial network. Inhibition of either mitochondrial fusion (41) or fission (42) impairs mitochondrial function, particularly electron transport chain activity. Mitochondrial fission is essential for quality control of the mitochondrial network, limiting mitochondrial size (43), and precedes mitophagy (44), which eliminates damaged or dysregulated mitochondria. In the present study, SKM expression of DRP1 was decreased with alcohol, and gene expression of an essential DRP1 recruitment factor (45), MFF, was decreased with the interaction of increased AUDIT and 2-h glucose. It is possible that the observed increase in mitochondrial volume in the present study may have been due, in part, to decreased fission machinery. This hypothesis is consistent with previous findings that ethanol increased the formation of enlarged hepatic mitochondria with aberrant Drp1 pathway signaling in a murine model of chronic ethanol administration (46).

Separately, chronic ethanol feeding increased total SKM mitochondrial area in mice with a paradoxical decrease in fusion protein Mfn1 but not Mfn2 (47), which is consistent with gene expression results in the present study. These preclinical data support a role for altered mitochondrial dynamics in enlarged SKM mitochondria in human participants with alcohol use disorder (48). In the present study, participants ranged in severity of at-risk alcohol use and mitochondrial volume was not associated with AUDIT alone. Instead, increased mitochondrial volume was observed with the combination of higher AUDIT and lower glucose tolerance. Preclinical models have shown that MFN2 expression protects against glucose intolerance (49), whereas deficiency of fusion protein optic atrophy 1 (OPA1) protects against high-fat diet-mediated glucose intolerance (50), suggesting that mitochondrial fusion-related gene expression might be implicated in the development of T2D although the direction is less clear. Furthermore, people with overt T2D have smaller and more fragmented mitochondria than nondiabetic counterparts (51). The relationship between mitochondrial volume and the interaction between alcohol and glucose tolerance in the present study differs from that observed in T2D patients and may reflect a compensatory mechanism to maintain bioenergetic function in our cohort of PLWH. Although participants were largely virally suppressed, mitochondrial dynamics parameters may be complicated by their HIV status. Detailed analyses of mitochondrial dynamics are the subject of ongoing investigations.

Although no overt insufficiency in the capacity for mitochondrial ATP synthesis was observed in the present study, the interaction of AUDIT and lower glucose tolerance was associated with decreased PPARG and PPARD gene expression, suggesting dysregulated fuel utilization. This family of genes encodes transcription factors required for lipid handling, and in SKM, they are particularly important for fatty acid oxidation and insulin sensitivity (52–54). Previous work demonstrated that semiweekly administration of a PPARα, δ, or γ agonist protects against chronic ethanol-induced decreases in insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) receptor binding and insulin-responsive gene expression [aspartyl‐asparaginyl‐β‐hydroxylase (AAH)] in the liver, with concomitantly decreased steatosis (55). In SKM, activation of PPARδ rescued ethanol-mediated decreases in Akt phosphorylation, intramuscular triglyceride accumulation, and myotube glucose uptake (56). SKM insulin resistance is a key feature of T2D and precedes diabetes onset, and the PPAR family of transcription factors is targeted by antidiabetic medications that directly improve SKM insulin sensitivity (i.e., thiazolidinediones) (57). Therefore, it is notable that our observed decreases in expression of these genes with the interaction of AUDIT and 2-h glucose occurred in participants without overt T2D, suggesting that altered SKM lipid handling via PPAR signaling may occur before overt pathology. Our study was not powered to examine differences in specific fuel substrate oxidation, and studies that will determine the impact of alcohol use are warranted.

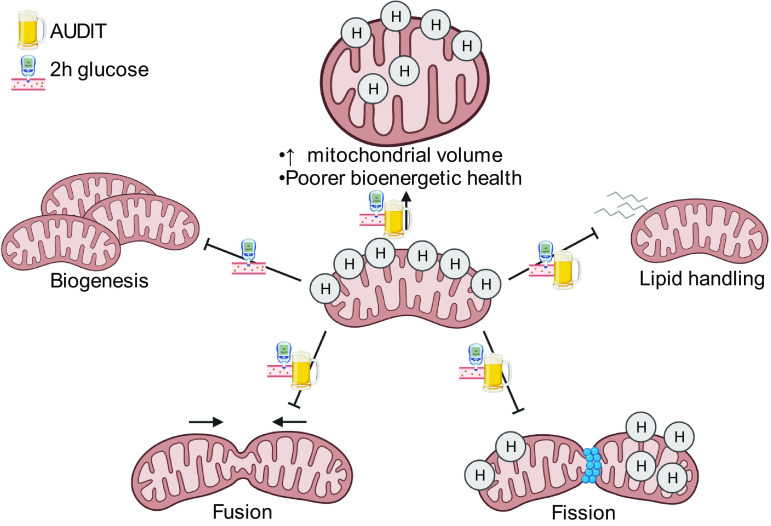

Perspectives and Significance

Overall, mitochondrial-related gene expression decreased with lower glucose tolerance and higher AUDIT score, and these changes were coupled with increased mitochondrial volume and decreased bioenergetic health in SKM of PLWH with elevated fasting glucose. However, the increase in mitochondrial volume does not appear to be adaptive. We hypothesize that the changes observed in genes regulating biogenesis, dynamics, and lipid handling may underlie poorer bioenergetic health and may precede overt energetic dysregulation observed with T2D (Fig. 3). These data underscore the need for effective interventions such as exercise to improve SKM and systemic metabolic health among PLWH with dysglycemia and at-risk alcohol use.

Figure 3.

Summary of findings. Note: Observed relationship between Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) score, 2-h glucose level, and outcome measures including expression of genes controlling mitochondrial biogenesis, fusion, fission, and lipid handling; mitochondrial volume; and indices of bioenergetic health, indicating a dysregulated mitochondrial profile as AUDIT score and 2-h glucose increase in PLWH. Image created with BioRender.com.

GRANTS

This work was funded by National Institutes of Health (NIH)/ National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) Grants F32AA027982 (to D.E.L.), UH2AA026198 (to P.E.M.), and P60AA009803 (to P.E.M.).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

D.E.L., L.S., and P.E.M. conceived and designed research; D.E.L., J.A.Z., J.A., and R.H.M. performed experiments; D.E.L. and T.F.F. analyzed data; D.E.L. and L.S. interpreted results of experiments; D.E.L. prepared figures; D.E.L. drafted manuscript; D.E.L., T.F.F., S.D.P., L.S., and P.E.M. edited and revised manuscript; D.E.L., T.F.F., S.D.P., J.A.Z., J.A., R.H.M., L.S., and P.E.M. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank all study participants, the ALIVE-Ex study staff (Alice Y. Yeh, MPH; Adrianna Peters), research staff affiliated with the LSUHSC Comprehensive Alcohol-HIV/AIDS Research Center for technical assistance (Bryant Autin, MS; Curtis Vande Stouwe; Naveena Chalapati, MSc; Rhonda M. Martinez; Jasmine Hall, MS; Chaoyi Zeng, MS), and the research staff with the LSUHSC Clinical Translational Research Center (Mary Meyaski-Schluter, FNP; Erin Meyaski, RN, BSN). We thank the Cellular Immunology and Immune Metabolism Core at the Louisiana Cancer Research Center (Grant 5P30GM114732-05 NIH/NIGMS) for access to the Seahorse XFe96 equipment, and Dorota Wyczechowska, PhD, for outstanding technical support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Estimated HIV incidence and prevalence in the United States, 2014–2018 (Online). https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-supplemental-report-vol-25-1.pdf [2021 Mar 22].

- 2.Nakagawa F, May M, Phillips A. Life expectancy living with HIV: recent estimates and future implications. Curr Opin Infect Dis 26: 17–25, 2013. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e32835ba6b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hulgan T. Factors associated with insulin resistance in adults with HIV receiving contemporary antiretroviral therapy: a brief update. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 15: 223–232, 2018. doi: 10.1007/s11904-018-0399-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crane HM, McCaul ME, Chander G, Hutton H, Nance RM, Delaney JAC, Merrill JO, Lau B, Mayer KH, Mugavero MJ, Mimiaga M, Willig JH, Burkholder GA, Drozd DR, Fredericksen RJ, Cropsey K, Moore RD, Simoni JM, Christopher Mathews W, Eron JJ, Napravnik S, Christopoulos K, Geng E, Saag MS, Kitahata MM. Prevalence and factors associated with hazardous alcohol use among persons living with HIV across the US in the current era of antiretroviral treatment. AIDS Behav 21: 1914–1925, 2017. doi: 10.1007/s10461-017-1740-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duko B, Ayalew M, Ayano G. The prevalence of alcohol use disorders among people living with HIV/AIDS: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy 14: 52, 2019. doi: 10.1186/s13011-019-0240-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Molina PE, Nelson S. Binge drinking’s effects on the body. Alcohol Res 39: 99–109, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Molina PE, Simon L, Amedee AM, Welsh DA, Ferguson TF. Impact of alcohol on HIV disease pathogenesis, comorbidities and aging: integrating preclinical and clinical findings. Alcohol 53: 439–447, 2018. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agy016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ford SM, Simon L, Vande Stouwe C, Allerton T, Mercante DE, Byerley LO, Dufour JP, Bagby GJ, Nelson S, Molina PE. Chronic binge alcohol administration impairs glucose-insulin dynamics and decreases adiponectin in asymptomatic simian immunodeficiency virus-infected macaques. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 311: R888–R897, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00142.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Primeaux SD, Simon L, Ferguson TF, Levitt DE, Brashear MM, Yeh A, Molina PE. Alcohol use and dysglycemia among people living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in the Alcohol & Metabolic Comorbidities in PLWH: Evidence Driven Interventions (ALIVE-Ex) study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 2021. doi: 10.1111/acer.14667.[34342022] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simon L, Ferguson TF V, Stouwe C, Brashear MM, Primeaux SD, Theall KP, Welsh DA, Molina PE. Prevalence of insulin resistance in adults living with HIV: implications of alcohol use. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 36: 742–752, 2020. doi: 10.1089/AID.2020.0029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee MJ, Kim E-H, Bae S-J, Choe J, Jung CH, Lee WJ, Kim HK. Protective role of skeletal muscle mass against progression from metabolically healthy to unhealthy phenotype. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 90: 102–113, 2019. doi: 10.1111/cen.13874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hong S, Chang Y, Jung H-S, Yun KE, Shin H, Ryu S. Relative muscle mass and the risk of incident type 2 diabetes: a cohort study. PLoS One 12: e0188650, 2017. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0188650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Romanello V, Sandri M. Mitochondrial quality control and muscle mass maintenance. Front Physiol 6: 422, 2015. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2015.00422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Favaro G, Romanello V, Varanita T, Andrea Desbats M, Morbidoni V, Tezze C, Albiero M, Canato M, Gherardi G, De Stefani D, Mammucari C, Blaauw B, Boncompagni S, Protasi F, Reggiani C, Scorrano L, Salviati L, Sandri M. DRP1-mediated mitochondrial shape controls calcium homeostasis and muscle mass. Nat Commun 10: 2576, 2019. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10226-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McBride MJ, Foley KP, D'Souza DM, Li YE, Lau TC, Hawke TJ, Schertzer JD. The NLRP3 inflammasome contributes to sarcopenia and lower muscle glycolytic potential in old mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 313: E222–E232, 2017. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00060.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akasaki Y, Ouchi N, Izumiya Y, Bernardo BL, LeBrasseur NK, Walsh K. Glycolytic fast-twitch muscle fiber restoration counters adverse age-related changes in body composition and metabolism. Aging Cell 13: 80–91, 2014. doi: 10.1111/acel.12153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Molina PE, Lang CH, McNurlan M, Bagby GJ, Nelson S. Chronic alcohol accentuates simian acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-associated wasting. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 32: 138–147, 2008. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00549.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levitt DE, Chalapati N, Prendergast MJ, Simon L, Molina PE. Ethanol-impaired myogenic differentiation is associated with decreased myoblast glycolytic function. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 44: 2166–2176, 2020. doi: 10.1111/acer.14453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duplanty AA, Siggins RW, Allerton T, Simon L, Molina PE. Myoblast mitochondrial respiration is decreased in chronic binge alcohol administered simian immunodeficiency virus-infected antiretroviral-treated rhesus macaques. Physiol Rep 6: e13625, 2018. doi: 10.14814/phy2.13625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simon L, Hollenbach AD, Zabaleta J, Molina PE. Chronic binge alcohol administration dysregulates global regulatory gene networks associated with skeletal muscle wasting in simian immunodeficiency virus-infected macaques. BMC Genomics 16: 1097, 2015. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-2329-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simoneau JA, Kelley DE. Altered glycolytic and oxidative capacities of skeletal muscle contribute to insulin resistance in NIDDM. J Appl Physiol 83: 166–171, 1997. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.83.1.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hesselink MKC, Schrauwen-Hinderling V, Schrauwen P. Skeletal muscle mitochondria as a target to prevent or treat type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Endocrinol 12: 633–645, 2016. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2016.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumar A, Davuluri G, Welch N, Kim A, Gangadhariah M, Allawy A, Priyadarshini A, McMullen MR, Sandlers Y, Willard B, Hoppel CL, Nagy LE, Dasarathy S. Oxidative stress mediates ethanol-induced skeletal muscle mitochondrial dysfunction and dysregulated protein synthesis and autophagy. Free Radic Biol Med 145: 284–299, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2019.09.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hernandez-Romieu AC, Garg S, Rosenberg ES, Thompson-Paul AM, Skarbinski J. Is diabetes prevalence higher among HIV-infected individuals compared with the general population? Evidence from MMP and NHANES 2009–2010. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care 5: e000304, 2017. doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2016-000304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jeremiah K, Filteau S, Faurholt-Jepsen D, Kitilya B, Kavishe BB, Krogh-Madsen R, Olsen MF, Changalucha J, Rehman AM, Range N, Kamwela J, Ramaiya K, Andersen AB, Friis H, Heimburger DC, PrayGod G. Diabetes prevalence by HbA1c and oral glucose tolerance test among HIV-infected and uninfected Tanzanian adults. PLoS One 15: e0230723, 2020. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0230723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG. The alcohol use disorders identification test: guidelines for use in primary care, second edition (Online). World Health Organization, 2001. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/67205/1/WHO_MSD_MSB_01.6a.pdf [2016 Mar 1]. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hahn JA, Anton RF, Javors MA. The formation, elimination, interpretation, and future research needs of phosphatidylethanol for research studies and clinical practice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 40: 2292–2295, 2016. doi: 10.1111/acer.13213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levitt DE, Adler KA, Simon L. HEMA 3 staining: a simple alternative for the assessment of myoblast differentiation. Curr Protoc Stem Cell Biol 51: e101, 2019. doi: 10.1002/cpsc.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Simon L, LeCapitaine N, Berner P, Vande Stouwe C, Mussell JC, Allerton T, Primeaux SD, Dufour J, Nelson S, Bagby GJ, Cefalu W, Molina PE. Chronic binge alcohol consumption alters myogenic gene expression and reduces in vitro myogenic differentiation potential of myoblasts from rhesus macaques. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 306: R837–R844, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00502.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Simon L, Ford SM, Song K, Berner P, Vande Stouwe C, Nelson S, Bagby GJ, Molina PE. Decreased myoblast differentiation in chronic binge alcohol-administered simian immunodeficiency virus-infected male macaques: role of decreased miR-206. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 313: R240–R250, 2017. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00146.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adler K, Molina PE, Simon L. Epigenomic mechanisms of alcohol-induced impaired differentiation of skeletal muscle stem cells; role of Class IIA histone deacetylases. Physiol Genomics 51: 471–479, 2019. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00043.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen Y, Ikeda K, Yoneshiro T, Scaramozza A, Tajima K, Wang Q, Kim K, Shinoda K, Sponton CH, Brown Z, Brack A, Kajimura S. Thermal stress induces glycolytic beige fat formation via a myogenic state. Nature 565: 180–185, 2019. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0801-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xiao B, Deng X, Zhou W, Tan E-K. Flow cytometry-based assessment of mitophagy using MitoTracker. Front Cell Neurosci 10: 76, 2016. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2016.00076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gautam N, Sankaran S, Yason JA, Tan KSW, Gascoigne NRJ. A high content imaging flow cytometry approach to study mitochondria in T cells: MitoTracker Green FM dye concentration optimization. Methods 134–135: 11–19, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2017.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Robichaux S, Lacour N, Bagby GJ, Amedee AM. Validation of RPS13 as a reference gene for absolute quantification of SIV RNA in tissue of rhesus macaques. J Virol Methods 236: 245–251, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2016.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Levitt DE, Yeh AY, Prendergast MJ, Budnar RG Jr, Adler KA, Cook G, Molina PE, Simon L. Chronic alcohol dysregulates skeletal muscle myogenic gene expression after hind limb immobilization in female rats. Biomolecules 10: 441, 2020. doi: 10.3390/biom10030441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chacko BK, Kramer PA, Ravi S, Benavides GA, Mitchell T, Dranka BP, Ferrick D, Singal AK, Ballinger SW, Bailey SM, Hardy RW, Zhang J, Zhi D, Darley-Usmar VM. The Bioenergetic Health Index: a new concept in mitochondrial translational research. Clin Sci (Lond) 127: 367–373, 2014. doi: 10.1042/CS20140101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Menshikova EV, Ritov VB, Fairfull L, Ferrell RE, Kelley DE, Goodpaster BH. Effects of exercise on mitochondrial content and function in aging human skeletal muscle. J Gerontol Ser A: Biol Sci Med Sci 61: 534–540, 2006. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.6.534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ventura-Clapier R, Garnier A, Veksler V. Transcriptional control of mitochondrial biogenesis: the central role of PGC-1alpha. Cardiovasc Res 79: 208–217, 2008. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shao D, Liu Y, Liu X, Zhu L, Cui Y, Cui A, Qiao A, Kong X, Liu Y, Chen Q, Gupta N, Fang F, Chang Y. PGC-1β-regulated mitochondrial biogenesis and function in myotubes is mediated by NRF-1 and ERRα. Mitochondrion 10: 516–527, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2010.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen H, Chomyn A, Chan DC. Disruption of Fusion results in mitochondrial heterogeneity and dysfunction. J Biol Chem 280: 26185–26192, 2005. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503062200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Parone PA, Da Cruz S, Tondera D, Mattenberger Y, James DI, Maechler P, Barja F, Martinou JC. Preventing mitochondrial fission impairs mitochondrial function and leads to loss of mitochondrial DNA. Herman C, editor. PLoS One 3: e3257, 2008. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lewis TL, Kwon S-K, Lee A, Shaw R, Polleux F. MFF-dependent mitochondrial fission regulates presynaptic release and axon branching by limiting axonal mitochondria size. Nat Commun 9: 5008, 2018. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07416-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mao K, Klionsky DJ. Participation of mitochondrial fission during mitophagy. Cell Cycle 12: 3131–3132, 2013. doi: 10.4161/cc.26352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Otera H, Wang C, Cleland MM, Setoguchi K, Yokota S, Youle RJ, Mihara K. Mff is an essential factor for mitochondrial recruitment of Drp1 during mitochondrial fission in mammalian cells. J Cell Biol 191: 1141–1158, 2010. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201007152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Palma E, Ma X, Riva A, Iansante V, Dhawan A, Wang S, Ni HM, Sesaki H, Williams R, Ding WX, Chokshi S. Dynamin-1–like protein inhibition drives megamitochondria formation as an adaptive response in alcohol-induced hepatotoxicity. Am J Pathol 189: 580–589, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2018.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eisner V, Lenaers G, Hajnóczky G. Mitochondrial fusion is frequent in skeletal muscle and supports excitation-contraction coupling. J Cell Biol 205: 179–195, 2014. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201312066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Song SK, Rubin E. Ethanol produces muscle damage in human volunteers. Science 175: 327–328, 1972. doi: 10.1126/science.175.4019.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kong D, Song G, Wang C, Ma H, Ren L, Nie Q, Zhang X, Gan K. Overexpression of mitofusin 2 improves translocation of glucose transporter 4 in skeletal muscle of high-fat diet-fed rats through AMP-activated protein kinase signaling. Mol Med Rep 8: 205–210, 2013. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2013.1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pereira RO, Tadinada SM, Zasadny FM, Oliveira KJ, Pires KMP, Olvera A, Jeffers J, Souvenir R, Mcglauflin R, Seei A, Funari T, Sesaki H, Potthoff MJ, Adams CM, Anderson EJ, Abel ED. OPA1 deficiency promotes secretion of FGF21 from muscle that prevents obesity and insulin resistance. EMBO J 36: 2126–2145, 2017. doi: 10.15252/embj.201696179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kelley DE, He J, Menshikova EV, Ritov VB. Dysfunction of mitochondria in human skeletal muscle in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 51: 2944–2950, 2002. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.10.2944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Muoio DM, MacLean PS, Lang DB, Li S, Houmard JA, Way JM, Winegar DA, Corton JC, Dohm GL, Kraus WE. Fatty acid homeostasis and induction of lipid regulatory genes in skeletal muscles of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) α knock-out mice. J Biol Chem 277: 26089–26097, 2002. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203997200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smith AG, Muscat GEO. Skeletal muscle and nuclear hormone receptors: implications for cardiovascular and metabolic disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 37: 2047–2063, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Amin RH, Mathews ST, Camp HS, Ding L, Leff T. Selective activation of PPARγ in skeletal muscle induces endogenous production of adiponectin and protects mice from diet-induced insulin resistance. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 298: E28–E37, 2010. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00446.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.de la Monte SM, Pang M, Chaudhry R, Duan K, Longato L, Carter J, Ouh J, Wands JR. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor agonist treatment of alcohol-induced hepatic insulin resistance: PPAR treatment of ALD. Hepatol Res 41: 386–398, 2011. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2011.00775.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Koh J-H, Kim K-H, Park S-Y, Kim Y-W, Kim J-Y. PPARδ attenuates alcohol-mediated insulin resistance by enhancing fatty acid-induced mitochondrial uncoupling and antioxidant defense in skeletal muscle. Front Physiol 11: 749, 2020. 10.3389/fphys.2020.00749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Petersen KF, Shulman GI. Pathogenesis of skeletal muscle insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am J Cardiol 90: 11–18, 2002. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(02)02554-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]