Abstract

Clinical lipidomics using mass spectrometry (MS) is important to support discovery of biomarkers for diagnosis and understanding the pathophysiology of diseases. Frequently, lipidomics data from clinical studies have large variations among individuals because the human metabolome/lipidome is strongly influenced by genotype, daily activity, diet and gut flora. This inter-personal variability makes data analysis more complex and normally requires a large cohort for robust statistical analysis. Crossover designed experiments treat each subject as his or her own control, thereby reducing the between-subject variability, such that the effects of exposure/treatment are more likely to be identified when using a relatively small number of subjects. This design repeatedly samples an individual when crossing over from one treatment/exposure to another during the course of the study. The acquired datasets have a distinct data structure resulting from repeated longitudinal measurements. A variety of statistical methods are used in published crossover studies, but many appear to ignore the data structure inherent in the experimental design. An appropriate data analysis approach is critical to discovering robust clinical biomarkers. Hereby, we summarize the statistical methodologies suitable for clinical lipidomics studies using crossover design. To help understand and apply these methods to practical cases, we focused on the general concepts of statistical models in the context of analysis of metabolomics data without spending too much effort on mathematical details. Importantly, we aim to evaluate these methods and provide suggestions for data analysis and biomarker discovery. We applied the discussed methods on a MS-based lipidomics dataset from a double-blind random crossover designed clinical dietary intervention study. The strength and potential pitfalls of each method are briefly discussed and a suggestion for analytic workflow proposed.

Keywords: Crossover design, Clinical lipidomics data, Statistical analysis

1. Introduction

Metabolites are a real-time reflection of human phenotypes that are shaped by genotype and environmental factors, including diet, daily activity and gut microbiota. Systematic analysis of metabolites (i.e. metabolomics) has been increasingly used to study the changes in metabolism associated with disease progression and response to pharmaceutical or nutritional interventions [1]. Mass spectrometry (MS)-based metabolomics has demonstrated great promise in the identification and quantitation of a large diversity (up to thousands) of biologically relevant metabolites, with the goal of elucidating the pathophysiology of diseases and facilitating potential therapeutic interventions. However, to this point, the impact of metabolomics in routine clinical practice has been limited due to challenges relating to study design, bioanalytical techniques and statistical analysis in biomarker discovery [2].

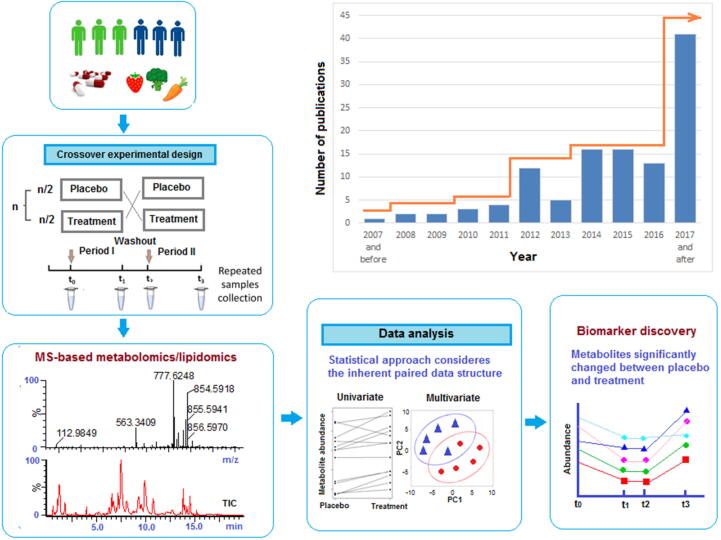

Because of the potentially high intra-individual and inter-individual biological variability of the human metabolome, appropriate experimental design is critical when conducting a clinical metabolomics study [3]. In nutritional intervention trials, for example, treatment-specific biomarkers are usually difficult to define because the treatment effects on metabolite levels tends to be relatively small in comparison to the inherent metabolite variation between subjects. Increasing the sample size may help detect the treatment effect and provide statistical confidence in the biomarker discovered. However, the recruitment of participants is often limited by budgetary constraints, and a larger sample size does not always proportionally enhance power in metabolomics data analysis. In order to boost statistical power, many studies adopt a randomized crossover design where a participant receives two or more sequential interventions/exposures in a random order, in separate treatment periods, usually separated by a washout period to eliminate a ‘carry-over’ intervention effect from one treatment period into the next (Fig. 1). The influence of confounding variance and inter-individual variation is reduced since each participant serves as his/her own control. Hence, fewer subjects are normally required in a crossover study than in comparable parallel design. Due to the potential advantages regarding data analysis, the number of metabolomics studies adopting crossover experimental design has increased steadily over the past decade, as demonstrated by the number of relevant original research articles (using the terms “metabolomics” or “metabolome” and “crossover”) cited in the Pubmed database (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

General workflow of a crossover designed clinical metabolomics study and the trend of publications used this experimental design from Pubmed database in the last decade.

As a recently established sub-field of metabolomics, lipidomics focuses on profiling lipids from cells, biological fluids and tissues. Lipids in human cells not only serve as major structural components, but are involved in signal transduction and regulate cellular functions [4], [5]. It has been demonstrated that the lipidome is altered in disease states and during development [6]. With comprehensive lipidomic analysis using MS-based platforms (usually hundreds of lipid molecules can be identified and quantified from a single sample), this approach has facilitated biomarker discovery for various diseases, including cardiovascular conditions, diabetes, and neurodegeneration [7], [8], [9]. However, data analysis for clinical lipidomics studies with a particular study design can be challenging due to the complex data structure that ensues from a specific experimental scheme. Currently, statistical methods appropriate for placebo-controlled crossover design studies are lacking [10], especially for untargeted lipidomics data analysis. Issues affecting the risk of bias in analysis, such as choice of specific statistical methods, are often ignored. Numerous studies did not adopt within-individual differences in their analyses and the authors treated the results as if they were from a parallel design [11]. This is inappropriate or at least insufficient since it fails to account for the underlying study design.

Development of statistical approaches, which explicitly consider the experimental design, will bridge the gap between current lipidomics studies and discovery of clinically relevant biomarkers. Herein, we summarize the advantages and limitations associated with various statistical approaches in the context of analysis of crossover designed lipidomics data. An example of a MS-based nutritional intervention lipidomics dataset from a double-blind randomized crossover designed study is presented to illustrate the application of these statistical models. Although we have focused on clinical lipidomics studies, statistical approaches discussed in this tutorial may also be applied to other metabolomics datasets in a similar manner.

2. MS-based clinical lipidomics with crossover design studies

2.1. Experimental design for clinical lipidomics/metabolomics studies

The dynamic nature of human metabolome, including lipidome, underlines the importance of experimental design in accurately measuring metabolites with real clinical importance. Large inter-individual variation is observed in human plasma and urine metabolomics samples [12]. Using placebo, or baseline, data from the same subject can potentially reduce the effects from this high degree of variation between individuals. Crossover design has been increasingly adopted in therapeutic studies of chronic disease and in nutritional studies of dietary interventions. Randomized controlled crossover lipidomics/metabolomics studies have recently sought to measure biological responses from environmental exposures [13], [14], dietary interventions [12], [15], [16], [17], [18], exercise effects [3], [19] and pharmacological treatments [20], [21], [22]. One of the main goals of these types of studies is to discover biomarkers and provide insights underlying responses to bioactive nutrients, food ingredients, pollutant exposures, or therapeutic drugs. A two-arm design, including a placebo treatment, is usually used rather than a single-arm design, which is typically not adequately powered and lacks a frame of reference for comparison to identify significantly changed metabolites [23]. In clinical metabolomics studies, participants should be selected with the goal of generating data that will be as homogeneous as possible. Demographic factors may significantly affect the metabolic profile and participants are usually requested to refrain from potential known interferences before and during an intervention study. Other confounding factors that might affect the lipidome during the study period, such as diet and bodyweight changes, are also recorded to help explain possible outliers. The role of thoughtful experimental design in clinical lipidomics studies cannot be overstressed when focusing on treatment-induced variations for both acute and long-term intervention trials.

In this mini-review, we will focus on the simplest form of crossover experiment, an AB/BA design, which has been used widely in clinical studies. In this paradigm, patients are randomly exposed to treatment A followed by treatment B, or vice versa. Because both treatments have been applied to the same patient, we can estimate the treatment effect based on the average of within-individual variations. Given this advantage, it is theoretically possible to achieve the same power as with a parallel design, but with half of the sample size. Furthermore, we propose that treatment effects measured from the same patient generally have a better precision than case/control cohorts used in a parallel design. We further discuss the issues in power analysis in the following sections.

2.2. MS-based clinical lipidomics platform

For lipidomics analysis, MS offers high sensitivity for detection of low abundance lipids and a wide coverage of metabolites. The MS-based approach is now the most used analysis methodology in clinical lipidomics/metabolomics studies. Chromatography techniques are routinely combined with MS to separate different metabolites before ionization, which helps to reduce compound and matrix signal interferences. As a result, in MS-based lipidomics data, the term “feature” usually refers to a compound ion with a specific retention time (RT) from chromatographic separation, a mass/charge ratio (m/z) and a related intensity. RT adds an extra level of confidence in confirmation and identification of unknown lipid ions. Chromatographic properties of different lipids have been well studied and lipid species from different classes can either be separated by reverse phase (RP) or hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC). RP liquid chromatography separates lipid species based on their hydrophobic properties, such as acyl chain length, sn1 and sn2 positional isomers, and double bond positions [24]. HILIC separates lipids according to polarity in a class-specific fashion. This is possible because lipid species within the same class share a common hydrophilic head group and elute together. While HILIC is suitable for detection of polar lipids, including glycerophospholipids and glycosphingolipids, it is not useful in the separation of non-polar lipids [25]. While RPLC has wide coverage and is powerful for separation of non-polar lipids separation, it lacks the ability to separate isobaric lipids of different classes. Given the chemical diversity of lipids in complex biological samples, using these techniques in tandem provides better separation and characterization of individual lipids.

Another popular MS approach for lipidomics analysis is ‘shotgun lipidomics’, where the crude sample extract is directly infused into a high resolution MS. Lipid molecules are ionized by soft electrospray ionization (ESI) and then analyzed on the basis of accurate m/z information. Since it eliminates chromatographic separation, the analysis time is reduced substantially. However, this approach cannot differentiate isobaric lipid species and the total number of lipids that can be detected remains low [6]. Separation of isobaric/isomeric lipids can be enhanced with the use of ion mobility techniques that utilize the conformational differences in structures to resolve lipid species. Ion mobility MS separates lipid ions based on their drift time in buffer gas phase according to the charge, size and shape of these structurally similar molecules. It measures collision cross section (CCS), which is a physical property of the lipid ion reflecting the conformational shape of the ion [26]. Using CCS as a dimension in addition to accurate mass and fragmentation patterns, interfering isobaric species can potentially be separated to improve lipid identification.

Structural characterization of lipid species in untargeted lipidomics normally carried out by tandem MS (MS/MS) and lipid class-selective fragments from unique head groups such as m/z 184.0733 (C5H15NO4P) of protonated phosphocholine in positive mode, among others, have been well documented. Many databases, such as LipidBlast and HMDB, supply MS/MS spectra generated either in silico or from reference standards providing a high confidence level for identification of lipids, if combined with accurate mass and retention time information [27], [28].

The most common samples in clinical lipidomics studies are biological fluids (e.g., serum, plasma, tissue samples). Extraction, purification and preparation of the sample before MS analysis is important, and the strategy used will depend on the polarity and abundance of targeted analytes of interest. Technical details of sample preparation for clinical lipidomics studies has been thoroughly described elsewhere [29], [30]. Pooled samples and internal standards are normally used as quality controls to determine batch effects. Considering potential instrumental shift, samples from the same individual in a crossover study should be analyzed together in a single run and the individual participant samples randomized in the sample analysis sequence [12]. Before statistical analysis, raw data acquired from MS are first pre-processed with noise filtering, baseline correction, peak detection, alignment, and deconvolution/deisotoping algorithms [31]. Appropriate data pre-processing is necessary to eliminate spectral artifacts and to remove irrelevant variation that is not related to underlying biological characteristics, and convert the data into a usable form for further interpretation. Various ‘free’ or commercial software tools are available for download, or to use online directly [32]. For robust data analysis, metabolite signal abundance (i.e., peak area or height) ideally has a linear correlation with metabolite concentration. Furthermore, the concentrations of different metabolites have a wide range in human metabolome, with differences often being many orders of magnitude. Therefore, it may be that minor constituents hold great clinical significance and the absolute quantities of metabolites may not be directly proportional to their biological relevance. Processed metabolomics data are usually normalized prior to statistical analysis. Methods of normalization and scaling have been reviewed by van den Berg et al. [33]. In addition, further processing procedures can be applied for data validation. For example, excessive zeros in the data need to be evaluated and treated. These zeros could result from situations such as signal response less than the detection limit of the MS platform, peak picking errors, or deconvolution errors. Running a sample in duplicate or triplicate within a batch and using average values is an optional strategy to reduce non-informative zeros. Another strategy is to exclude those features with zeros beyond a certain threshold (e.g., metabolite ion detection frequency less than 50%) [34]. Data transformation by logarithm or square root to normal, or near normal, is common practice, but its usage should be handled carefully due to the change of variance structure. Last but not least, identification or annotation of metabolites for biological interpretation is essential, but could be time-consuming and usually relies on searching available databases with accurate m/z, retention time and MS/MS spectra, when available.

Human lipidome/metabolome changes due to disease progression or therapeutic intervention can be determined using untargeted and targeted approaches. Untargeted approaches seek to measure as many detectable metabolite ions as possible and to uncover previously unknown metabolic modifications. As a hypothesis-free and data-driven strategy, it serves as an exploratory tool in the study. Quantification of feature ions depends on relative comparison of peak area or height among samples from different experimental groups. The results may be used to generate insightful hypotheses to be further tested with a targeted approach. In the targeted analysis, a group of known metabolites, which have shown clinical association with phenotype is quantified with high specificity and sensitivity. Using calibration curves and quality control samples, this approach provides absolute quantification on the compounds of biological importance with high accuracy. A review of the literature shows that many untargeted studies were not further validated with a more accurate targeted approach. For this reason, it is inappropriate to rely solely on an untargeted approach for clinical metabolomics studies; rather, a combined approach is critical to proper data interpretation.

2.3. Essential factors to consider in statistical modeling of clinical lipidomics datasets with crossover design

In general, factors affecting statistical analysis of clinical trials that focus on a single variable are also applied to multivariate lipidomics data. For example, optimal sample size for clinical lipidomics studies generally also depends on experimental factors, including expected effect of intervention, sample homogeneity and study design. It has been recognized that crossover studies require smaller sample size than parallel-group clinical trials in terms of same type I and II error risk criteria [35]. The increase in efficiency can be understood by differentiating between-subject variance and within-subject variance in the dataset. The minimum biological replicates needed to achieve a certain power can be estimated using pilot data, or previously reported study sizes as a reference [36]. However, it has been cautioned that robust sample size estimation is still very poorly established for multivariate metabolomics data [15]. Power analysis for untargeted metabolomics studies is not straightforward because both the analytes to be measured and the effect size of treatment are not known a priori. For example, it is often not known which, and how many, metabolite candidates will be of potential interest, as well as metabolite value distribution and internal correlation structure. Without this information, estimation of the effect size will likely be inaccurate. One alternative is to choose a known metabolite as a representative for the entire metabolome and apply a univariate method to estimate the optimal sample size [37]. This method might oversimplify human metabolome changes since the metabolic network tends to be rather conservative, but a single metabolite usually shows large variation among individuals. Van Iterson et al. [38] developed a BioConductor package (SSPA) for high-dimensional genomics data. In the computation, the pilot multivariate dataset is treated as univariate data in combination with multiple testing correction. One of the limitations of this strategy is that correlations between variables cannot be considered. Blaise et al. proposed a computational method using a large simulation dataset for power estimation [39]. Correlations between variables are explicitly modeled, as well as the data distribution. An artificial effect size was used to determine sample size. Both methods rely strongly on preliminary or previously analyzed data, which are usually absent in clinical lipidomics studies. Furthermore, it is not easy to accommodate the crossover study experimental design into the analysis. There is a strong need to develop efficient algorithms to estimate multivariate study sample size with a special design.

For statistical analysis of a crossover dataset, confounding variables, including age and gender of study participants is of less concern than for parallel-group design. However, other sources of variance inherent in a crossover design need to be considered. One of these factors is the period effect, in which a participant shows systematic difference in metabolic outcome in the two treatment periods that is not dependent on the treatment received. Another important factor is carryover effect, which should be checked in a preliminary test, if possible. In addition, analytical variation due to sample preparation, instrumental drift and raw data pre-processing constitutes another source of variation. These factors need to be thoroughly evaluated before beginning data analysis.

3. Statistical analysis of crossover designed metabolomics data

Choosing an appropriate statistical method depends on key factors of the dataset that include normality of the data, number of metabolites and study subjects, variation in metabolic response in the studied population, and available information on the confounding factors included in the statistical model. However, an effective model must account for the paired nature of the crossover data so that the potential gain in statistical efficiency can be achieved. Multivariate approaches, such as principal component (PC)-based methods, take into account the correlation and dependency between metabolites and are more robust for large and noisy datasets, particularly if the sample size is large. Univariate approaches, on the other hand, treat each metabolite feature independently, but can explicitly handle within-individual treatment comparisons, such as paired student t-test. In the following sections, we will cover the mathematical rationale of the univariate approach. We will then discuss application of these methods in the context of metabolomics datasets of crossover design, and potential solutions if the underlying data distribution is not normal.

3.1. Univariate analysis

3.1.1. Paired sample t-test

The paired t-test takes the pairing information of the crossover data into account. It considers the difference in response between the two treatments for each subject and uses a t-test to determine whether the mean difference between the two treatments is zero or not. The non-parametric counterpart of the paired t-test, i.e. Wilcoxon signed-rank test, has also been applied on metabolomics datasets with crossover design [40]. The sign of the difference (positive or negative) is assigned to each absolute difference value. Based on the signed ranks, a test statistic is then calculated and compared with a critical value to determine whether to reject the null hypothesis (i.e., the mean difference response between placebo and intervention is zero). The Wilcoxon signed-rank test works best when distribution of the difference of the response between placebo and intervention is not normal. For similar cases with more than a two-arm design, the Friedman test with post-hoc pairwise comparison could be used [37]. A limitation of paired t-test, or similar, methods is that they do not consider other factors that can affect the result; e.g., if gender is a factor that can affect the subject’s response so subjects can be clustered by their gender. Another limitation of paired t-test if that it does not consider the order of the treatment (placebo or intervention) that each subject receives. Therefore, it will not be appropriate unless the carryover effect is negligible. To overcome these limitations, the more general linear mixed effects model and Grizzle’s method can be used.

3.1.2. Grizzle’s method

Grizzle’s method [41] is a classic method for crossover design. This method considers the carryover effect. In particular, the method is based on the following model,

| (1) |

where is the observed response for the -th () subject of the -th sequence () in the -th () period. Here, the two sequences are AB () and BA (), where A and B are the two treatments (placebo and intervention). ( or ) is the direct effect of the treatment ; is the effect of period k; ( and ) is the residual effect (a term used in [41]) of the treatment , is the random effect associated with the -th subject of the -th sequence; is the overall mean. The period effect and the residual effect are used to represent the carryover effect, where is used to account for the difference of the carryover effect between A and B. The above model is essentially a special case of general linear model called linear mixed effect model (LMM). The random intercepts are the random components and a complete two-way model (two factors, treatment and period, and their interactions) as the fixed component. We will discuss more details of LMMs in the Section 3.1.3.

Grizzle’s method is a two-step procedure. The first step tests the null hypothesis (equality of the residual effects, which is equivalent of equality of carryover effects). If is not rejected, one then tests (equality of treatment effects) using the complete data; if is rejected, one then tests using the data from the first period only. To test , one calculates the sum of the two responses for each subject (), and then applies a two-sample t-test on the sums (the two groups are determined by the sequences of the subjects). To test when is not rejected, one calculates the difference of the two responses for two periods for each subject (), and then applies a two-sample t-test on the differences (the two groups are determined by the sequences of the subjects). To test when is rejected, one applies a two sample t-test on the responses of all subjects for the first period (the two groups are determined by the treatments that the subjects received during the first period). In Grizzle [41], it was recommended to perform the test in the first step under significant level 0.1.

The main advantage of this method lies in its testing and consideration for the carryover effect. However, this effect is only likely to affect the result when the active intervention is carried out before placebo in the sequence. With a sufficient washout period, the artificial “effectiveness” from the first intervention would be minimized and it was recommended that the benefit of including data from both periods almost always overweigh the risk of leaving half of the data out [11]. We suggest that researchers should estimate the carryover effect carefully based on the length of the washout phase and only test for carryover effect if absolutely necessary.

3.1.3. Linear mixed effects models (LMMs)

Linear mixed effect models, which have been widely used in human genomics research, offer a flexible approach to estimate the effects of fixed- and random-effect variables on metabolomics data [42]. A linear mixed model can be constructed in the following general form for a metabolite from a metabolomics study,

| (2) |

where is the observed metabolite level for the -th () subject with -th () treatment, is the overall mean, is the effect of treatment , is fixed effect of the -th predictor , is the random effect for the -th subject, is the Gaussian error term. The error term in LMMs is random and does not have a specific correlation structure. They are independent and identically distributed. The correlation between the observations is reflected by the sample-specific random effects in the model.

LMMs have been increasingly applied in analysis of crossover designed metabolomics data [13], [43]. Instead of assuming the same relationship between the experimental factors and every metabolite detected, LMMs build a linear model for each metabolite, separately. In the model, both experimental variables have a fixed effect on metabolite levels and those having a random effect are incorporated. Such factors with fixed effects influence a metabolite level in an anticipated and consistent way, and they are normally the target of investigation, such as treatment factor, which should impart fixed effects on the metabolome across patients. In comparison, factors with random effects create an unanticipated variation on a metabolite signal. Typical random effect variables include date of sample collection, instrument response and technician who processed the samples [42]. In the model, we can also include predictors, such as age, gender, BMI and other covariates.

Although a sufficient washout period can minimize the carryover, an appropriate statistical method may still take into account the carryover effect and the intrinsic data structure for a more robust analysis. The final metabolomic datasets are normally large and complex with the number of metabolite ions detected reaching thousands to tens of thousands [44]. On the other hand, most clinical metabolomics studies are restricted by a limited number of subjects, often due to budget and recruiting constraints. In the following description, we define an MS-based clinical metabolomics data matrix containing N sample row vectors of P features each. The so-called curse of dimensionality problem is that a metabolomics dataset usually contains many more features (P) in comparison to the number of samples (N), i.e. ‘large P, small N’. Traditional linear regression methods cannot be applied directly to these datasets as is no longer invertible [45]. This problem is a significant challenge for the following statistical analysis.

Importantly, choosing a univariate statistical test depends on the normality, homogeneity of variance (i.e., homoscedasticity), and sample independence of the metabolomics data [46]. Statistical methods discussed in this section, including paired t-test and analysis of variance (ANOVA), rely on assumptions, such as normal distribution of the sample population. Linear models also assume normality and homoscedasticity for the residual data distribution. It is difficult to find real life metabolomics datasets that strictly satisfy these theoretical assumptions. However, most parametric statistical methods are robust for slight violations and they can still be applied. Data can be normalized by taking the logarithm or square root if they follow a lognormal or contain many very small or zero values. But one should be cautious when using these techniques since it changes the variance of the transformed variable and may affect the interpretation of the results [46]. Nonparametric methods are a good option when the normality of the data is a significant concern, particularly for small sample sizes. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test can be used as alternative to the paired t-test, and the Kruskal-Wallis test can be used in place of ANOVA. Nonparametric tests may be more flexible regarding assumptions of underlying data distribution, but they are usually less powerful than their parametric counterparts and the results are often not intuitive to interpret. The latter due to the fact that many nonparametric methods use rankings instead of actual values. We suggest all of these factors be carefully considered before applying a univariate statistical method to the dataset.

3.2. Multivariate analysis

3.2.1. Multivariate approaches ignoring the inherit data structure perform poorly

Because of the inter-correlation of metabolites in the metabolic network, metabolomics data analysis tends to be multivariate by nature [47]. Multivariate approaches, such as principal component analysis (PCA) and partial least squares – discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) are extremely popular for metabolomics studies. This is at least partially due to the more intuitive interpretation of these models in comparison to more complex support vector machine (SVM) and artificial neural network (ANN) methods [45], which seek to decompose metabolite variables into latent structures and maximize projected variance.

Several randomized crossover intervention studies have used PLS-DA directly as part of the data analysis for biomarker discovery [48], [49]. There is a significant disadvantage in disregarding the paired data structure underlying the crossover design, considering that the inter-individual variability is likely greater than intra-individual variability resulting from intervention [49]. As a result, the intervention effects may be underestimated. It has been demonstrated that small and subtle treatment effects appear differently among human participants and will not be observed by Orthogonal projections to latent structures-discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) [50]. In general, direct application of the above classical multivariate methods may result in significant misinterpretation of the effect of treatment intervention under a noisy biological variation background. A similar underperformance of PCA was shown in a study of the cardiometabolic effects of soy nuts [49] where PCA revealed no significant pattern in blood and urine samples of pre- and post-intervention groups. This is because the inter-individual variation was large, while treatment effect was subtle and small (i.e. in the above mentioned study, samples from same individual cluster together but not pre- and post-intervention groups). To focus on within-subject variation, new methods, such as multilevel approach, are proposed to split within-subject variation from between-subject variation before PCA and following statistical analysis.

3.2.2. Multilevel multivariate approach

In this section, the normalized data, or response, is denoted by a matrix . Here is the number of subjects (participants), is the number of periods and is the number of metabolite features. The response of the -th metabolite feature for the -th subject in the -th period is denoted by , where , and . The intervention/placebo information for the observations forms a -dimensional vector (usually encoded by −1 and 1).

There is only a very limited number of published papers that have applied special adjustment of multivariate methods for crossover metabolomics data. Crossover design studies primarily use a multilevel approach that performs variation separation as an essential step before the multivariate analysis [50], [51], [52], [53], [54]. This is because the crossover design generates metabolomics data with a multilevel data structure, i.e., different treatments are nested within subjects. To differentiate biological variation among subjects from the variation caused by treatment effect, within-subject variation and between-subject variation must be divided and analyzed separately.

In multilevel analysis [52], each column of (the response data for each metabolite feature) is decomposed into three components. The three components are the overall mean, the deviation of the averaged response (averaged over the two periods) of each subject to the overall mean (of the column), and the deviation of the two responses to the averaged response for each subject. In particular, each entry of column j can be represented by

| (3) |

where is the overall mean of column j, is the deviation of the averaged response (averaged over the two periods) of subject i to the overall mean, and is the deviation of the response to the averaged response of subject i. In this way, the total variation is decomposed into the between-subject variation and the within-subject variation . Therefore, the data matrix is decomposed as

| (4) |

where contains the mean values of the columns of , contains the between-subject variations, and contains the within-subject variations. and can then be examined and processed separately by different multivariate analyses.

3.2.2.1. Multilevel PCA

In multilevel analysis [52], PCA is applied on . Such an analysis can detect large variations between the subjects due to their biological differences, e.g., age, gender etc [55]. In this PCA, is standardized as using Pareto-scaling, which uses the square root of standard derivation as scaling factor, thus emphasizing more intense metabolites in the dataset [33].

3.2.2.2. Multilevel PLS-DA

In multilevel analysis [52], PLS-DA is applied to . Such an analysis can identify the most discriminative metabolite features. In this PLS-DA, is standardized as using Univariate Variance (UV) scaling, which scales all variables to unit variance, thus giving all metabolites equal opportunity to influence the model. UV-scaling scales up features with low intensity and scales down features with high intensity, so that these features are considered equally in the PLS-DA model. The cross model validation procedure [56] is used to determine the optimal number of latent components. By exploiting variances from different sources, multilevel PLSDA can explore diverse treatment effects on each subject and the intrinsic variability between the study subjects [50]. In general, multilevel PLS-DA can be regarded as a multivariate extension of the paired t-test.

In most nutritional metabolomics datasets, the number of subjects () is usually much smaller than the number of metabolite features (). This makes the obtained models prone to serious overfitting issues. Rigorous validation measures, including cross model validation with permutation is recommended to confirm class separation [57]. In this case, a high dimensional metabolomics dataset is randomly split into a test set, a validation set and a training set. Importantly the test set is left out during model optimization and is only used to estimate the rate of classification error. Furthermore, the paired data structure has to be retained during resampling to estimate a true model classification error [52].

The most discriminative features in the multilevel PLS-DA model can be selected by the so-called rank products (RP) [58]. In this model, all metabolite features are ranked by their PLS regression coefficients corresponding to their contribution to the regression. Final RP is the product of all the ranks over multiple validation repeats or the geometric average of those ranks. The most discriminant features are those with the lowest rank products, are thus the best candidate biomarkers. Combining classification models, permutation tests, double cross-validation and variable selection with RP score can provide a more robust approach to statistically discover and validate candidate biomarkers.

Table 2 summarizes the main advantages, along with important caveats that need to be considered, in crossover designed clinical lipidomics data analysis. This is not an exhaustive list since new statistical approaches are continually being applied and developed. We believe this can be used as an introduction for clinical researchers to start thinking through the appropriate statistical approaches for analysis of lipidomics or metabolomics data with specialized design.

Table 2.

Summary of discussed statistical methods for biomarker discovery of cross-over designed clinical lipidomics studies [45], [46], [50].

| Paired t-test | Grizzle’s method | Linear mixed effects models | Multilevel PLSDA & derivatives | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pros |

|

|

|

|

| Caveats |

|

|

|

|

When the number of variables greatly exceeds the number of samples, e.g., number of features far more than subjects, overfitting due to spurious correlations could be a serious problem, especially for PLS based models. In this case sparse multivariate models can be considered as a better alternative. Sparse PCA [59] and independent PCA [60] proposed to perform an internal variable selection to identify biologically relevant features in modelling. Sparse PLS-DA is a variant of PLS-DA and adds a L1 constraint on the loading vector [59]. This constraint forces the loadings of irrelevant variables to be zeros so that those variables do not contribute to the discriminant direction. Therefore, only variables that best discriminate sample classes will be chosen in the model [51]. This is particularly useful in metabolomics data analysis, as such data contains many variables that are irrelevant and could affect the model performance.

In some cases, the change from baseline for each metabolite can be used as an outcome metric in the statistical analysis. Some researchers have suggested that estimation of treatment effects could be improved when baseline data analysis is applied appropriately [61]. However, others have mentioned that it is unlikely to be beneficial in a crossover design because the changes from baseline from the two treatment periods usually have a low correlation and the variance of the treatment effect estimates actually may be less precise [11]. Nevertheless, an explanation of which baseline was used for the calculation of change, i.e. “is it the trial baseline that collected before the first period?” or “is it after the completion of one period and a washout, but before the start of the next period” and a rationale on including baseline value could be helpful for the readers to understand the results.

4. Example: clinical nutritional intervention lipidomics data analysis

To illustrate the application of the statistical methods discussed above, we present preliminary data from an untargeted MS-based lipidomics dataset from a clinical nutritional intervention study. In this study we focused on biomarker discovery of the untargeted data analyzed using both univariate- and multivariate-based approaches.

4.1. Study design

This clinical pilot study was a double-blinded, placebo-controlled crossover design. Participants consumed a novel soy germ (isoflavone-enriched) pasta (Aliveris srl, Foligno, Italy), containing 33 mg isoflavones per 80 g serving [62] daily for 3 consecutive weeks, while conventional pasta (lacking isoflavones) was used as placebo. A 2-week washout period was used to diminish the carryover effect. Thirteen out of sixteen healthy participants (28–67 years of age, 6 males and 7 females) completed the study. Compliance to the isoflavone-enriched pasta was confirmed by urinary/serum isoflavone levels measured with a targeted LC-MS/MS assay, as described in a previous study [63]. Fasting blood samples were collected from each participant before and after placebo or isoflavone-enriched pasta. Previous studies have shown significant clinical effects of this type of pasta in hypercholesterolemic [64] and diabetic patients [62], [65].

4.2. Serum sample preparation and lipidomics profiling

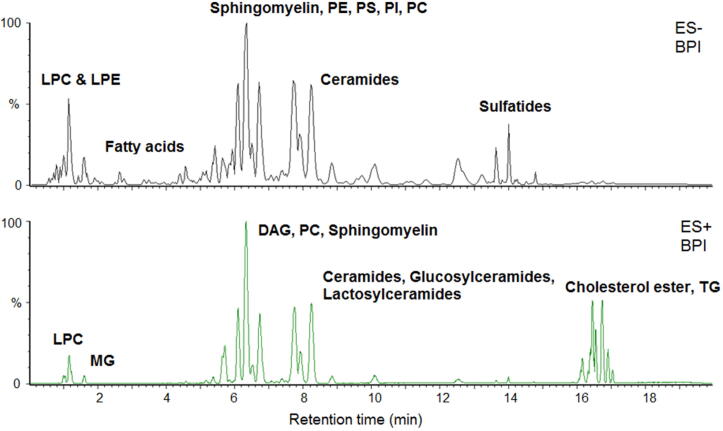

Serum samples were extracted by a modified Folch method [66] and data were collected using ultra-high performance liquid chromatography coupled with a quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometer (UPLC-QTOF-MS, Waters, Milford, MA). A gradient mobile phase was used with a binary solvent system, which changed from 60% solvent A to 57% solvent A over 2 min, then to 50% solvent A at 2.1 min, then to 46% solvent A over 9.9 min, and then, after change to 30% at 12.1 min, to 1% solvent A over 5.9 min, then to 60% solvent A at 18.1 min and this was held for 2 min. The total run time was 20 min, and the flow rate was 0.4 mL/min. Solvent A consisted of acetonitrile/water (60/40) with 10 mM ammonium formate and 0.1% formic acid; solvent B consisted of isopropanol/acetonitrile (90/10) with 10 mM ammonium formate and 0.1% formic acid. The injection volume was 5 μL for negative mode and 2 μL for positive mode. Column temperature was kept at 55 °C. The capillary voltage was 2 KV for positive mode and 1 KV for negative mode, cone voltage was 30 V, desolvation temperature, 550 °C; desolvation gas flow, 900 L/h; source temperature, 120 °C; mass acquisition range 50–1200 m/z. In total, 163 lipid species were detected with accurate mass and retention time match to an in-house lipid database in both positive and negative ion modes from serum samples. Representative ion chromatograms from positive and negative mode are shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Representative mass chromatograms (base peak ion) from serum lipidomics profiling samples acquired in both positive and negative ion mode by UPLC-QTOF-MS. Mass chromatogram regions harbor different lipid classes and separated by respective retention times and accurate mass over charge (m/z). Abbreviations: lysophosphatidylcholines (LPC), lysophosphatidylethanolamines (LPE), phosphatidylserines (PS), phosphatidylinositols (PI), phosphatidylethanolamines (PE), phosphatidylcholines (PC), monoacylglycerols (MG), diacylglycerols (DG), triacylglycerols (TG).

Lipid features were considered for further statistical analysis only if the area of the peak was at least 3 times higher than blank samples or not present in blanks. We also excluded lipids that had more than 20% CV in QC samples. By these criteria, both triglyceride (TG) and cholesteryl ester (CE) classes were not included in the example dataset due to the higher noise observed from QC samples from this batch in the retention time window. We recognize the potential bias from not including the abundant TGs in the nutritional-based biomarker analysis. Nevertheless, despite this limitation, the purpose of using this dataset was to provide a general example to illustrate the statistical approaches for crossover data structure.

Lipid features were detected in both positive and negative ion modes in this MS-based lipidomics platform. Phosphatidylcholine (PC) and sphingomyelin (SM) classes form positive protonated ion [M+H]+ and negative formate adduct ions [M+FA−H]−, while phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) can form both protonated and deprotonated ions under ESI. We checked to confirm the lipid identifications and used the sum of the peak area from different ion modes for the final data analysis when the lipid species identification was confirmed.

4.3. Data analysis

Normality and homogeneity of variance of the dataset were evaluated by the Shapiro-Wilk method and Levene’s test using MetabR [42]. Since the sample size is small, we used the Shapiro-Wilk test and 44 lipid features had a p-value <0.05, which was about 25% of the total identified lipid species. After logarithmic transformation (Log2) the number of significant lipid features decreased to 20. Levene’s test assesses the equality of variance and 7 lipid features had p-values <0.05. After logarithmic transformation (Log2) the number of lipid features decreased to 5. After Log2 transformation, the Shapiro-Wilk test indicated no substantial deviations from normal distribution. Therefore, logarithm transformation was applied on the example dataset in the following analysis when the statistical model assumed normal distribution and homoscedasticity. Biomarker discovery was conducted either by available R packages for multilevel multivariate analysis and linear mixed effects model or by in-house written R scripts Core [67] for other univariate- and multivariate-based methods.

4.3.1. Analysis of sample variation by multilevel PCA

According to Eq. (4), variation of the dataset can be partitioned into a group mean (), between subject variation, i.e. biological variation (), and within subject variation, i.e. treatment variation (). The sum of the squares || ||2 thus, can be represented by the sum of ||||2, ||||2, and ||||2 (||||2 = ||||2+||||2 + ||||2). Since each sub-model is independent of the others, we can estimate the proportion of variation resulting from different sources. The respective variations for the example dataset are, 93.2% explained by , 5.8% by , and the about 1% is explained by , which is the effect brought by the soy isoflavone. As expected, is primarily defined by the group mean, . The treatment effect described by within-subject variation is relatively small, accounting for only one-seventh of the biologically relevant variation in the data. This echoes previous reports that found the effect from nutritional intervention is generally much smaller in the context of individual variations for the reason that volunteers in the study were normally healthy and in metabolic homeostasis [68], [69]. This implied that it is unlikely to differentiate this treatment effect from individual biological variations without using approaches that explicitly account for the underlying paired data structure.

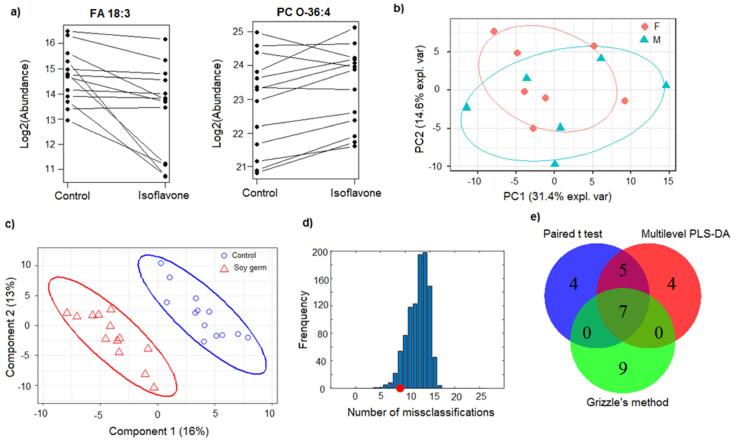

A multilevel PCA score plot of between-individual variation was used to explore systematic patterns in the dataset to see if gender is a factor in response to soy isoflavone intervention. We observed no clear gender effect in the data (Fig. 3b). Since this is a relatively small dataset with in total 13 participants (7 females and 6 males), we feel that there is not enough statistical power to reveal a true pattern. It can only serve as an illustration for the exploration tools available for data analysis. PCA can only reveal group separation when within-group variation is sufficiently less than between-group variation. This indicates that, in this example dataset, the personal variation in response to isoflavone-enriched food is still relatively large.

Fig. 3.

a) Lipids that belong to ether phosphatidylcholine and fatty acid (FA) classes are significant by paired t-test including FA 18:3 (decreased in 12 out 13 participants after consuming isoflavone enriched pasta with a p-value 0.007) and PC O-36:4 (increased in 10 out 13 participants after consuming isoflavone enriched pasta with a p-value 0.019). b) Multilevel PCA score plot of between-individual variation to detect if gender effect can be detected in response to soy isoflavone intervention. c) Multilevel PLS-DA scores plot reveals difference of lipidomics samples after participants taking control and soy germ pasta. d) Effect on lipidome from isoflavone enriched pasta is statistically significant using permutation test. The distribution of CMV prediction errors from 1000 permutations is considered as the null distribution of no effect. e) Venn diagram of significant metabolites identified from univariate- and multivariate-based methods.

4.3.2. Biomarker discovery by univariate methods

To detect metabolic effects from consuming isoflavone enriched food, we first applied a paired t-test in combination to false discovery rate correction for multiple testing problem. It was found that the FDR correction was too strict for this clinical lipidomics dataset as all adjusted p-values were >0.10. We believe that in a clinical metabolomics dataset with relatively small sample size and subtle intervention effects, solely relying on statistical threshold for biomarker discovery maybe too rigid. The alternate approach may be to use a less stringent threshold to control false positives and further examine potential biomarker candidate in the context of the biochemical interpretation of the interested phenotype. With a p-value cutoff of 0.05, it was found that 16 lipids were significantly differentiated between two periods using a paired t-test. Among these metabolites, two potential lipid biomarkers are especially interesting findings. One candidate, FA 18:3 decreased in 12 out 13 participants after consuming isoflavone enriched pasta with a p-value 0.007 (Fig. 3a). One possible identity of this compound is linolenelaidic acid, a trans-fatty acid (TFA). TFA has been implicated in cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk for its role in raising low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels and lower high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol levels [70]. However, linolenelaidic acid cannot be differentiated from its geometric isomer linoleic acid using the current chromatographic method. Another candidate biomarker was PC O-36:4, which was increased in 10 out 13 participants after consuming isoflavone enriched pasta with a p-value of 0.019. One of the two isomeric forms of this lipid is plasmenlogen PC, which has been implicated in metabolic diseases, including diabetes [71], [72]. These lipids now need to be definitively confirmed by comparison against authentic standards, which is the standard approach when untargeted analysis identify potentially significant biomarkers. This work is currently ongoing and outside the scope of this article.

Using Grizzle’s method, 20 significant metabolites were identified (assuming that the residual effects were the same for the two treatments and p-value <0.05). Among them, 7 metabolites were detected by both methods. All of these seven lipids were also revealed by multilevel PLS-DA as discussed below (Table 1). The difference in the number of significant features between the two methods mainly lies in the carryover effect factor. Grizzle’s method incorporates the sequential order of control and treatment in the model, but the paired t-test ignores the carryover effect. With a sufficient washout period, carryover should not be a major concern in the crossover designed data analysis. However, individual differences could exist and influence the metabolome if the washout phase is not able to completely eliminate a carryover effect. In this case, Grizzle’s method may be more suitable and accurate. We measured urinary isoflavones at baseline and after consumption of placebo and isoflavone enriched pasta, thus providing confidence regarding subject compliance to the diets. We only included participants with insignificant levels of isoflavones after washout period for the final data analysis. Carryover effects may not be a major concern, but we concentrated on the common biomarkers discovered by both methods for further targeted analysis.

Table 1.

Candidate biomarkers from univariate and multilevel multivariate analysis.

| Metabolite | Paired t-test (p-value) |

Grizzle’s method (p-value) |

Multilevel PLSDA (Rank based on RP score of 20 CMV*) |

|---|---|---|---|

| FA 18:3 | 0.007 | 0.010 | 1 |

| LPC 20:4 | 0.010 | 0.018 | 4 |

| PC 38:6 | 0.030 | 0.069 | 9 |

| PC O-36:4 | 0.019 | 0.210 | 36 |

| C16 Sulfatide | 0.675 | 0.008 | 52 |

*RP score is the geometric average of rank products, i.e. RP1/20. Rank is out of total 163 lipid features.

We also tested LMMs on the example dataset to model the fixed and random effects from participants. Although LMMs are intensively used in genomics research, there are no appropriate computational tools that have been developed specifically for metabolomic data. We used the R Bioconductor package limma [73] which is a popular tool of applying linear models for microarray and RNA-Seq data analysis. A desirable capability of this tool is the use of linear models to discover potential biomarkers in the context of crossover designed experiments. Running a linear effects mixed model based on Eq. (2) gave very similar results as that from the two sample paired t-test (data not shown). This is because paired t-test is essentially a special case of LMMs and we didn’t include extra factors in the linear model for the example dataset. LMMs have the potential to model more complex multilevel experimental design and we recommend that readers explore its application based on their own research needs. The p-values from LMMs have a small difference than those of corresponding paired t-test since limma uses an empirical Bayes approach borrowing information between metabolite features before estimating statistical significance.

4.3.3. Biomarker discovery by multilevel multivariate analysis

The spatial distribution in the PLS-DA scores plot, after considering multilevel data structure, of participants taking control and soy germ pasta was distinct (Fig. 3c). As discussed previously, it has been well-recognized that overfitting is a major concern for PLS-based modelling for metabolomic data analysis. There are two main reasons for this problem. First, PLS-based methods are supervised approaches and explicitly code class membership for group separation in the model. Second, the number of features in normal metabolomic data is much higher than that of subjects. Therefore, it is essential to validate the obtained model and estimate overfitting risk. To do this, we used a cross model validation (CMV) procedure to estimate misclassification (i.e. classification error) as described earlier [52]. In the procedure, metabolomic data is randomly divided into a training dataset, a validation dataset, and a test dataset. Unlike the training and validation datasets, which are used in the model optimization, the test set is kept out of this procedure and only was used in estimating the prediction error of the model. Data from same individual, i.e. collected after eating control and isoflavone-enriched pasta, were treated pairwise in the resampling procedure. Then variation partitioning was conducted as described in Section 3.2.2 prior to PLS-DA analysis. Sequentially decreasing numbers of features (about half of the variables were retained through each selection round based on the updated rank) were tested in the PLS-DA model construction using single cross validation to determine the optimum PLS components and features for the final model. Parameters of the obtained model were iteratively optimized in this step. A permutation test was then used to test statistical significance of the treatment in which control and isoflavone-enriched pasta classes were randomly assigned. In total, 1000 permutations were conducted in the model and the distribution of their prediction errors was used as the null hypothesis. The treatment is considered significant if the p-value <0.05.

By means of CMV we can predict the intervention class labels of the test samples. Before prediction, the training dataset was scaled by the unit variance method. To obtain a robust class prediction and a stable rank product, an average result of 20 CMVs was used. On average, 9 test samples were predicted incorrectly with the obtained MLPLS-based model, which is about 35% of all prediction results (Fig. 3d). To test overfitting risk (i.e. obtained by chance), a comparative permutation test was performed. In this test, the predictions of permuted data from 1000 permutations, which were representative of a null distribution of no effect. That is, if there is no detectable treatment effect, an average number of 13 misclassifications would be expected. As shown in Fig. 3d, the experimentally obtained null distribution H0 is exactly a normal distribution with a mean at 13. Comparing the CMV prediction error of the original model (9 misclassifications) against the permutations under the null distribution, the p-value is much smaller than 0.05. This indicates that only a fraction of the 1000 permutations resulted in a prediction error lower than 9. Therefore, we validated that the observed treatment effect is, in fact, statistically significant (p value <0.05). Despite the small sample size in this pilot study, it revealed that dietary intervention of soy germ pasta has a metabolic effect in healthy adults and these observed effects on metabolites were different from pasta lacking isoflavones.

Since we are ultimately interested in biomarker discovery, we need a scoring system to select the most discriminative features from the optimized model. In this study, we used rank products from 20 CMV to identify potential biomarkers, as delimited in Section 3.2.2.2. In the computation we initially chose the top 16 features, i.e. the same number of significant features as that of paired t-test, using RP score and compared them with the results of univariate methods. In total, 12 out of 16 lipids were identified by both MLPLS-DA and the paired t-test, but only 7 of them overlapped with Grizzle’s method (Fig. 3e). Among the lipid features discovered by multiple methods, fatty acid and ether-linked phosphatidylcholine lipid classes are directly implicated in the potential health effects and will be investigated more carefully by a targeted approach.

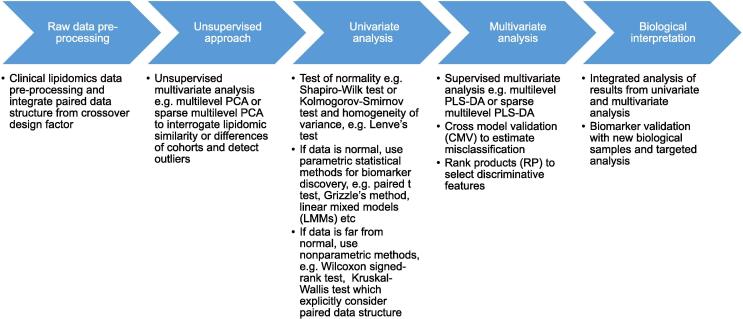

In analysis of this example dataset, we applied both univariate and multivariate methods following a proposed workflow as summarized in Fig. 4. Multilevel PCA (or its sparse alternative) was used first in understanding the overall pattern of the dataset after variation splitting. In this step we inspected both the biological differences between individuals and the treatment effect from dietary intervention within individuals. Further biomarker discovery was carried out by both univariate and multivariate analysis. Depending on the carryover effects concerned, either the whole dataset or only the first period was used in the analysis, such as that adopted in Grizzle’s method. Candidate biomarkers that showed high significance in more than one method were examined and a biological interpretation was attempted on the candidates. Each statistical model has its own merits and limits, so an ensemble of methods could improve biomarker discovery. Furthermore, biological interpretation of the biomarkers carries greater importance when supported by mathematical models.

Fig. 4.

Proposed general workflow of statistical analysis of MS-based datasets using crossover design.

A preliminary investigation of significant lipid features demonstrates this approach has the capacity to highlight relevant metabolic changes with respect to diet intervention in the example dataset. Potential biomarkers of clinical relevance were identified highlighting how appropriately combining univariate and multivariate approaches, as discussed in this paper, may be used to enhance biomarker discovery.

5. Concluding remarks

Clinical lipidomics studies generate complex and high dimensional datasets that are further complicated by experimental designs, including crossover design. Statistical analysis of clinical lipidomics data for biomarker discovery needs to be adjusted to better fit the data structure that results from the respective design. To use the available statistical methods, we considered correlation between samples from the same subject and took the paired data structure into account in choosing appropriate models. However, even with this improved approach, there still is the chance to oversimplify the metabolic profile changes in response to the intervention. Disease progress and treatment response are inherently dynamic processes [74]. To better define intra-individual sample variability in terms of lipdiome or metabolome dynamics, time-course samples, as well as period baseline samples, should be collected. Linear mixed effect models and jointly modeling baseline and post-treatment measurements, has great potential for longitudinal data analysis for their ability to model time course data. The joint modeling method is especially useful when data are strongly correlated within the same period, but weakly correlated between different periods [75]. Currently, computational tools designed for lipidomics/metabolomics data with multilevel data structure are still limited. Growing clinical lipidomics data from studies with different experimental designs warrant development of new statistical methodologies for robust biomarker discovery.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

This study was partially supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program, grant 5UL1TR001425-02. Authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Junfang Zhao of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center for her expert support.

Declaration of Competing Interest

Dr. Setchell and Dr. Clerici report holding an equity interest in Aliveris s.r.l.. Dr. Zhao and Dr. Niu report grants from National Institutes of Health (NIH) Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program during the conduct of the study. Dr. Russo and Melissa Byrd have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinms.2019.05.002.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Tolstikov V., Akmaev V.R., Sarangarajan R., Narain N.R., Kiebish M.A. Clinical metabolomics: a pivotal tool for companion diagnostic development and precision medicine. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2017;17(5):411–413. doi: 10.1080/14737159.2017.1308827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kohler I., Verhoeven A., Derks R.J., Giera M. Analytical pitfalls and challenges in clinical metabolomics. Bioanalysis. 2016;8(14):1509–1532. doi: 10.4155/bio-2016-0090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siopi A., Mougios V. Metabolomics in human acute-exercise trials: study design and preparation. Methods Mol. Biol. 2018;1738:279–287. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-7643-0_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Meer G. Cellular lipidomics. EMBO J. 2005;24(18):3159–3165. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saliba A.E., Vonkova I., Gavin A.C. The systematic analysis of protein-lipid interactions comes of age. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2015;16(12):753–761. doi: 10.1038/nrm4080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lydic T.A., Goo Y.H. Lipidomics unveils the complexity of the lipidome in metabolic diseases. Clin. Transl. Med. 2018;7(1):4. doi: 10.1186/s40169-018-0182-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kulkarni H., Meikle P.J., Mamtani M., Weir J.M., Barlow C.K., Jowett J.B., et al. Plasma lipidomic profile signature of hypertension in Mexican American families: specific role of diacylglycerols. Hypertension. 2013;62(3):621–626. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.01396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gomez Rosso L., Lhomme M., Merono T., Dellepiane A., Sorroche P., Hedjazi L., et al. Poor glycemic control in type 2 diabetes enhances functional and compositional alterations of small, dense HDL3c. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Mol. Cell. Biol. Lipids. 2017;1862(2):188–195. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2016.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wong M.W., Braidy N., Poljak A., Sachdev P.S. The application of lipidomics to biomarker research and pathomechanisms in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2017;30(2):136–144. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nolan S.J., Hambleton I., Dwan K. The use and reporting of the cross-over study design in clinical trials and systematic reviews: a systematic assessment. PLoS One. 2016;11(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li T., Yu T., Hawkins B.S., Dickersin K. Design, analysis, and reporting of crossover trials for inclusion in a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trost K., Ulaszewska M.M., Stanstrup J., Albanese D., De Filippo C., Tuohy K.M., et al. Host: Microbiome co-metabolic processing of dietary polyphenols – an acute, single blinded, cross-over study with different doses of apple polyphenols in healthy subjects. Food Res. Int. 2018;112:108–128. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2018.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ladva C.N., Golan R., Liang D., Greenwald R., Walker D.I., Uppal K., et al. Particulate metal exposures induce plasma metabolome changes in a commuter panel study. PLoS One. 2018;13(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0203468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li H., Cai J., Chen R., Zhao Z., Ying Z., Wang L., et al. Particulate matter exposure and stress hormone levels: a randomized, double-blind. crossover trial of air purification. Circulation. 2017;136(7):618–627. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.026796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gonzalez-Granda A., Damms-Machado A., Basrai M., Bischoff S.C. Changes in plasma acylcarnitine and lysophosphatidylcholine levels following a high-fructose diet: a targeted metabolomics study in healthy women. Nutrients. 2018;10(9) doi: 10.3390/nu10091254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Derkach A., Sampson J., Joseph J., Playdon M.C., Stolzenberg-Solomon R.Z. Effects of dietary sodium on metabolites: the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH)-Sodium Feeding Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017;106(4):1131–1141. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.116.150136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miles F.L., Navarro S.L., Schwarz Y., Gu H., Djukovic D., Randolph T.W., et al. Plasma metabolite abundances are associated with urinary enterolactone excretion in healthy participants on controlled diets. Food Funct. 2017;8(9):3209–3218. doi: 10.1039/c7fo00684e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ney D.M., Murali S.G., Stroup B.M., Nair N., Sawin E.A., Rohr F., et al. Metabolomic changes demonstrate reduced bioavailability of tyrosine and altered metabolism of tryptophan via the kynurenine pathway with ingestion of medical foods in phenylketonuria. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2017;121(2):96–103. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2017.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Valerio D.F., Berton R., Conceicao M.S., Canevarolo R.R., Chacon-Mikahil M.P.T., Cavaglieri C.R., et al. Early metabolic response after resistance exercise with blood flow restriction in well-trained men: a metabolomics approach. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2018;43(3):240–246. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2017-0471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moaddel R., Shardell M., Khadeer M., Lovett J., Kadriu B., Ravichandran S., et al. Plasma metabolomic profiling of a ketamine and placebo crossover trial of major depressive disorder and healthy control subjects. Psychopharmacology. 2018 doi: 10.1007/s00213-018-4992-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nguyen T.V., Reuter J.M., Gaikwad N.W., Rotroff D.M., Kucera H.R., Motsinger-Reif A., et al. The steroid metabolome in women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder during GnRH agonist-induced ovarian suppression: effects of estradiol and progesterone addback. Transl. Psychiatry. 2017;7(8) doi: 10.1038/tp.2017.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boxler M.I., Liechti M.E., Schmid Y., Kraemer T., Steuer A.E. First time view on human metabolome changes after a single intake of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine in healthy placebo-controlled subjects. J. Proteome Res. 2017;16(9):3310–3320. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.7b00294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Evans S.R. Clinical trial structures. J. Exp. Stroke Transl. Med. 2010;3(1):8–18. doi: 10.6030/1939-067x-3.1.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ulmer C.Z., Patterson R.E., Koelmel J.P., Garrett T.J., Yost R.A. A robust lipidomics workflow for mammalian cells, plasma, and tissue using liquid-chromatography high-resolution tandem mass spectrometry. Methods Mol. Biol. 2017;1609:91–106. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-6996-8_10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cifkova E., Holcapek M., Lisa M., Ovcacikova M., Lycka A., Lynen F., et al. Nontargeted quantitation of lipid classes using hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization mass spectrometry with single internal standard and response factor approach. Anal. Chem. 2012;84(22):10064–10070. doi: 10.1021/ac3024476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paglia G., Kliman M., Claude E., Geromanos S., Astarita G. Applications of ion-mobility mass spectrometry for lipid analysis. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2015;407(17):4995–5007. doi: 10.1007/s00216-015-8664-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kind T., Liu K.H., Lee D.Y., DeFelice B., Meissen J.K., Fiehn O. LipidBlast in silico tandem mass spectrometry database for lipid identification. Nat. Methods. 2013;10(8):755–758. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wishart D.S., Feunang Y.D., Marcu A., Guo A.C., Liang K., Vazquez-Fresno R., et al. HMDB 4.0: the human metabolome database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:D608–D617. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reis A., Rudnitskaya A., Blackburn G.J., Mohd Fauzi N., Pitt A.R., Spickett C.M. A comparison of five lipid extraction solvent systems for lipidomic studies of human LDL. J. Lipid Res. 2013;54(7):1812–1824. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M034330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vuckovic D. Current trends and challenges in sample preparation for global metabolomics using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2012;403(6):1523–1548. doi: 10.1007/s00216-012-6039-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Euceda L.R., Giskeodegard G.F., Bathen T.F. Preprocessing of NMR metabolomics data. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Invest. 2015;75(3):193–203. doi: 10.3109/00365513.2014.1003593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vettukattil R. Preprocessing of raw metabonomic data. Methods Mol. Biol. 2015;1277:123–136. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2377-9_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van den Berg R.A., Hoefsloot H.C., Westerhuis J.A., Smilde A.K., van der Werf M.J. Centering, scaling, and transformations: improving the biological information content of metabolomics data. BMC Genomics. 2006;7:142. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bijlsma S., Bobeldijk I., Verheij E.R., Ramaker R., Kochhar S., Macdonald I.A., et al. Large-scale human metabolomics studies: a strategy for data (pre-) processing and validation. Anal. Chem. 2006;78(2):567–574. doi: 10.1021/ac051495j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wellek S., Blettner M. On the proper use of the crossover design in clinical trials: part 18 of a series on evaluation of scientific publications. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2012;109(15):276–281. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2012.0276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ryan E.P., Heuberger A.L., Broeckling C.D., Borresen E.C., Tillotson C., Prenni J.E. Advances in nutritional metabolomics. Curr. Metabolomics. 2013;1(2):109–120. doi: 10.2174/2213235x11301020001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mena P., Tassotti M., Martini D., Rosi A., Brighenti F., Del Rio D. The Pocket-4-Life project, bioavailability and beneficial properties of the bioactive compounds of espresso coffee and cocoa-based confectionery containing coffee: study protocol for a randomized cross-over trial. Trials. 2017;18(1):527. doi: 10.1186/s13063-017-2271-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Iterson M., van de Wiel M.A., Boer J.M., de Menezes R.X. General power and sample size calculations for high-dimensional genomic data. Stat. Appl. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2013;12(4):449–467. doi: 10.1515/sagmb-2012-0046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Blaise B.J., Correia G., Tin A., Young J.H., Vergnaud A.C., Lewis M., et al. Power analysis and sample size determination in metabolic phenotyping. Anal. Chem. 2016;88(10):5179–5188. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b00188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Albaugh V.L., Singareddy R., Mauger D., Lynch C.J. A double blind, placebo-controlled, randomized crossover study of the acute metabolic effects of olanzapine in healthy volunteers. PLoS One. 2011;6(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grizzle J.E. The two-period change-over design an its use in clinical trials. Biometrics. 1965;21:467–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ernest B., Gooding J.R., Campagna S.R., Saxton A.M., Voy B.H. MetabR: an R script for linear model analysis of quantitative metabolomic data. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:596. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mei Y.J., Kim S.B., Tsui K.L. Linear-mixed effects models for feature selection in high-dimensional NMR spectra. Expert Syst. Appl. 2009;36(3):4703–4708. doi: 10.1016/.j.eswa.2008.06.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mamas M., Dunn W.B., Neyses L., Goodacre R. The role of metabolites and metabolomics in clinically applicable biomarkers of disease. Arch. Toxicol. 2011;85(1):5–17. doi: 10.1007/s00204-010-0609-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Worley B., Powers R. Multivariate analysis in metabolomics. Curr. Metabolomics. 2013;1(1):92–107. doi: 10.2174/2213235X11301010092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vinaixa M., Samino S., Saez I., Duran J., Guinovart J.J., Yanes O. A guideline to univariate statistical analysis for LC/MS-based untargeted metabolomics-derived data. Metabolites. 2012;2(4):775–795. doi: 10.3390/metabo2040775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Saccenti E., Hoefsloot H.C.J., Smilde A.K., Westerhuis J.A., Hendriks M.M.W.B. Reflections on univariate and multivariate analysis of metabolomics data. Metabolomics. 2014;10(3):361–374. doi: 10.1007/s11306-013-0598-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schmedes M., Aadland E.K., Sundekilde U.K., Jacques H., Lavigne C., Graff I.E., et al. Lean-seafood intake decreases urinary markers of mitochondrial lipid and energy metabolism in healthy subjects: metabolomics results from a randomized crossover intervention study. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2016;60(7):1661–1672. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201500785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reverri E.J., Slupsky C.M., Mishchuk D.O., Steinberg F.M. Metabolomics reveals differences between three daidzein metabolizing phenotypes in adults with cardiometabolic risk factors. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2017;61(1) doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201600132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Westerhuis J.A., van Velzen E.J., Hoefsloot H.C., Smilde A.K. Multivariate paired data analysis: multilevel PLSDA versus OPLSDA. Metabolomics. 2010;6(1):119–128. doi: 10.1007/s11306-009-0185-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liquet B., Le Cao K.A., Hocini H., Thiebaut R. A novel approach for biomarker selection and the integration of repeated measures experiments from two assays. BMC Bioinf. 2012;13:325. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-13-325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.van Velzen E.J., Westerhuis J.A., van Duynhoven J.P., van Dorsten F.A., Hoefsloot H.C., Jacobs D.M., et al. Multilevel data analysis of a crossover designed human nutritional intervention study. J. Proteome Res. 2008;7(10):4483–4491. doi: 10.1021/pr800145j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sautron V., Terenina E., Gress L., Lippi Y., Billon Y., Larzul C., et al. Time course of the response to ACTH in pig: biological and transcriptomic study. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:961. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-2118-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Garcia-Perez I., Posma J.M., Gibson R., Chambers E.S., Hansen T.H., Vestergaard H., et al. Objective assessment of dietary patterns by use of metabolic phenotyping: a randomised, controlled, crossover trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5(3):184–195. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(16)30419-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]