Abstract

It is unknown how patterns of cannabis and other drug use changed among young adult cannabis users as they became, exited or stayed medical cannabis patients (MCPs) after California legalized cannabis for adult use in 2016. A cohort of 18-26 year-old cannabis users was recruited in Los Angeles in 2014-15 (64.8% male; 44.1% Hispanic/Latinx). Based on wave 1 (pre-legalization) and wave 4 (post-legalization) MCP status, four transition groups emerged: MCP, Into MCP, Out of MCP and NPU (non-patient user). Relationships between self-reported medical cannabis use, transition group membership, and cannabis/other drug use outcomes were examined. Changes in cannabis practices were consistent with changes in MCP status. Cannabis days, concentrate use, self-reported medical cannabis use and driving under influence of cannabis were highest among MCP, increased for Into MCP, and decreased for Out of MCP in wave 4. A majority of drug use outcomes decreased significantly by wave 4. Self-reported medical cannabis use was associated with more frequent cannabis use but less problematic cannabis and other drug use. Future studies should continue to monitor the impact of policies that legalize cannabis for medical or recreational use, and medical motivations for cannabis use on young adults’ cannabis and other drug use.

Keywords: medical marijuana, cannabis legalization, drug use, young adults

INTRODUCTION

Young adults have the highest rates of cannabis use and contribute about 18% to the total population of medical cannabis patients (MCPs) (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality 2018; Nunberg et al. 2011; Reinarman et al. 2011). To date, cannabis is legal for medical use in thirty-five states and DC. California was the first state to legalize medical cannabis in 1996 and has one of the most inclusive definitions of qualifying conditions for a medical cannabis recommendation (California Code). California legalized recreational cannabis use for adults 21 or older with the passage of the Adult Use of Marijuana Act in November 2016, while recreational cannabis sales began in January 2018. The new legislation stipulates that MCPs are exempt from the state excise and cultivation taxes and may possess cannabis products in greater quantities than recreational cannabis users while continuing the provision that medical cannabis recommendations can be issued to adults 18 or older, or at a younger age with a parental permission (California Department of Public Health 2020). Given a policy environment that allows for both medical and recreational cannabis use, it is important to monitor trends in cannabis, other drug use, and problematic use, and how these trends relate to ongoing participation in a medical cannabis program among young adults. Apart from recent changes in cannabis laws and policy, cannabis use for medical purposes has been practiced for centuries and continues to be reported among those who choose not to or cannot legally become MCP (Chapkis and Webb 2008; Lankenau et al. 2017a; Ogborne, Smart, and Adlaf 2000). As a result, self-reported medical cannabis use is an emerging domain to study in a mixed policy environment since it can be a better indicator of medical orientation towards cannabis use than MCP status alone, especially among younger MCPs who have a greater proportion of self-reported recreational cannabis users compared to older MCPs (Fedorova et al. 2019; Haug et al. 2017).

Cannabis practices

Research on the impact of recreational cannabis legalization on cannabis use among young adults has shown mixed findings across several states to date: post-legalization increases in cannabis use in Oregon (Kerr, Bae, and Koval 2018), temporary increase in Washington (Miller, Rosenman, and Cowan 2017) and no significant change in use in Colorado (Jones, Jones, and Peil 2018). Studies conducted in California found an increase in post-legalization cannabis use among adults but not among adolescents or justice-involved young adults (Grigorian et al. 2019; Kan et al. 2020). Nationally, while there has been a shift indicating more positive attitudes towards recreational cannabis use, frequency or prevalence of cannabis use and cannabis use disorder among young adults was not significantly greater in states that have legalized recreational cannabis use compared to states that have not (Cerdá et al. 2020; Swift 2016). Regarding medical cannabis use, MCP status (Compton et al. 2017; Lankenau et al. 2017b; Lin et al. 2016; Richmond et al. 2015; Woodruff and Shillington 2016) and self-reported medical cannabis use (Choi, Dinitto, and Marti 2017; Metrik et al. 2018; Sznitman 2017) were associated with daily and more frequent cannabis use among adults. Several studies also reported higher rates of vaporization and use of cannabis concentrate and edibles among MCPs (Cranford et al. 2016; Lankenau et al. 2017b; Sznitman 2017) and self-reported medical cannabis users (Daniulaityte et al. 2017; Pacula, Jacobson, and Maksabedian 2016). No studies to date have investigated how changes in cannabis practices (e.g., use of different cannabis forms and frequency of use) may be related to young adults’ transitions in and out of MCP status pre- and post- recreational cannabis legalization in a legal medical cannabis environment, nor simultaneously accounting for the impact of self-reported medical cannabis use.

The growing number of states legalizing medical and recreational cannabis use has led to concerns about increases in the rates of cannabis use, driving while under the influence of cannabis (DUIC), and associated traffic fatalities. Recreational cannabis states have reported non-significant or temporary increases in traffic fatalities post-legalization (Aydelotte et al. 2019; Hansen, Miller, and Weber 2020; Lane and Hall 2019). Furthermore, in a national epidemiological study, medical cannabis laws were associated with reduction in traffic fatalities (Santaella-Tenorio et al. 2017). However, conflicting results have been reported on the association between MCP status and DUIC within a population of young adults. Young adult MCPs in California were more likely to report DUIC compared to NPUs (Tucker et al. 2019). In contrast, no difference in DUIC rates was found between MCPs and NPUs within a Facebook sample of 18-34-year-old past month cannabis users (Berg et al. 2018). No study has explored the role of self-reported medical cannabis use and changes in MCP status in the pre- and post-recreational cannabis legalization DUIC rates.

Other drug use

Cannabis policy liberalization and its impact on the rates of other drug use as a gateway to or a substitute for hard drugs has been debated over the past three decades (Chan, Burkhardt, and Flyr 2020; Hall 2015; Hasin et al. 2017; Kandel, Yamaguchi, and Chen 1992; Sifaneck and Kaplan 1995). Research examining the impact of recreational cannabis legalization on the use of alcohol, tobacco and other drugs among young adults is limited. A study of college undergraduates in Oregon showed a post-legalization reduction in tobacco use and a trend towards reduction in heavy alcohol use while no change was found for illicit drug use (Kerr et al. 2017; Kerr, Bae, and Koval 2018). Similarly, another study of college students in Washington did not observe significant increases in alcohol, tobacco or illicit drug use corresponding to changes in cannabis use after recreational cannabis use became legal (Miller, Rosenman, and Cowan 2017). Furthermore, studies of medical cannabis use among adults showed negative associations between MCP status and rates or severity of illicit drug use, prescription drug misuse and alcohol use (Compton et al. 2017; Lin et al. 2016; Martins et al. 2015; Park and Wu 2017; Richmond et al. 2015; Woodruff and Shillington 2016). However, in a study of 12th graders, MCPs were more likely to report past year illicit drug use and prescription drug misuse (Boyd, Veliz, and McCabe 2015). In an earlier cross-sectional study of young adults, we found no differences in recent illicit and prescription drug use and misuse between MCPs and NPUs (Lankenau et al. 2017b).

Few studies have investigated a relationship between self-reported medical cannabis use and other drug use. According to a longitudinal study of primary care patients, self-reported medical cannabis users had lower rates of polydrug use and scored lower on the Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST-10) (Roy-Byrne et al. 2015). A national cross-sectional epidemiological study of adults found no differences in cannabis or other drug use disorders between self-reported medical and recreational cannabis users, except for lower rates of alcohol use disorder among self-reported medical users (Choi, Dinitto, and Marti 2017). In an earlier cross-sectional report, we found that young adult self-reported medical cannabis users were less likely to use illicit drugs, but no differences were observed for prescription drug misuse (Fedorova et al. 2019). Notably, no study has assessed how post- recreational cannabis legalization transitions into and out of MCP status or self-reported medical cannabis use are related to other drug use over time.

Given the gap in the literature on longitudinal changes in MCP status, cannabis and other drug use among young adult cannabis users, especially within a context of cannabis legalization for adult use, the current study sought to address the following questions: (1) What were the changes in MCP status, cannabis use practices and other drug use before and after recreational cannabis legalization? (2) How were pre- versus post-recreational cannabis legalization changes in MCP status related to cannabis and other drug use?

METHODS

All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Boards at Drexel University and Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to the wave 1 survey.

Study sample

The study sample was recruited in Los Angeles, California, through targeted sampling (e.g., college campuses, parks, medical cannabis dispensaries, Craigslist) and chain referral by enrolled participants (Biernacki and Waldorf 1981; Watters and Biernacki 1989) as a part of the longitudinal Cannabis, Health And Young Adults (CHAYA) study. Eligible participants were 18 to 26 years old, able to speak and read English, lived in Los Angeles metro area, and used cannabis at least four times within 30 days prior to recruitment. Additional eligibility requirement was either being MCP (i.e., possessing a current valid medical cannabis recommendation issued in California), or being NPU (i.e., never been issued a medical cannabis recommendation). NPUs with expired medical cannabis recommendations were excluded from the study enrollment at baseline (see Lankenau et al. 2017a for additional details).

Data collection

Wave 1 (n=366), wave 2 (n=339), wave 3 (n=322) and wave 4 (n=302) surveys were conducted in February 2014 - April 2015, April 2015 - June 2016, March 2016 - June 2017, and April 2017 - April 2018, respectively, resulting in 83% retention rate at wave 4. About one third of wave 3 and all of wave 4 surveys were collected after cannabis became legal for adult use in California in November 2016. About one fifth of wave 4 surveys were collected after January 2018 when cannabis became available for purchase from recreational cannabis dispensaries. Surveys were interviewer-administered in waves 1, 2 and 3 (Fedorova et al. 2019), while wave 4 surveys were completed online through Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) survey link.

Measures

Demographic data (i.e., age, age at first cannabis use, assigned sex at birth, race/ethnicity, educational level, and employment status) were collected at wave 1 (Lankenau et al. 2017a).

MCP transition status, a primary independent variable, was created by using MCP status (yes/no) at waves 1 (pre-legalization) and 4 (post-legalization), which resulted in four groups: (1) MCP (MCP at waves 1 and 4); (2) NPU (NPU at waves 1 and 4); (3) transitioning Into MCP (NPU at wave 1, MCP at wave 4); and (4) transitioning Out of MCP (MCP at wave 1, NPU at wave 4). MCP status was verified by interviewers through visual inspection of the participant’s medical cannabis recommendation in waves 1-3 and based upon self-report in wave 4.

Self-reported medical cannabis use, another independent variable, was dichotomized (yes/no) into exclusively medical (no recreational use) or primarily medical (some recreational use) cannabis use versus equally medical and recreational use, primarily recreational (some medical use), or exclusively recreational (no medical use) in the past 90 days regardless of MCP status. Instructions to this item included examples of medical (to treat or help cope with any physical ailments, such as pain or discomfort, or psychological conditions, such as feeling anxious or sad, insomnia) and recreational (to socialize with others, to increase creativity, or to make experiences more pleasurable, interesting, or exciting) cannabis uses. A longitudinal summary variable was created by summing up self-reported medical cannabis use (yes/no) at each wave, with the scores ranging from 0 to 4.

Dependent or outcome variables were past 90-day cannabis practices and other drug use. Cannabis practices included days of cannabis use (range 0-90), cannabis concentrate (wax, shatter, dab, oil) use (yes/no), and DUIC (yes/no). Problematic cannabis use was assessed with the Severity of Dependence Scale (SDS), which is a five-item valid and reliable (Cronbach’s α=0.83) measure focused on worry or concern about cannabis use rather than consequences of use (Martin et al. 2006). Other drug use was assessed with the following items: In the past 12 months, have you used any of the following drugs when they were not prescribed to you or that you took only for the experience or feeling it caused (including to get high or to self-medicate)? followed by How long has it been since you last used [drug name]? to dichotomize responses into past-90-day use/misuse versus non-use/misuse of illicit, prescription drugs (see Fedorova et al. 2019 for the full list of drugs), alcohol, cigarettes and e-cigarettes. Polydrug use measured past-90-day illicit drug use and/or prescription drug misuse either immediately before, during, or after using cannabis (yes/no). The Short Michigan Alcohol Screening Test (SMAST) (Selzer, Vinokur, and van Rooijen 1975) and DAST-10 (Bohn, Babor, and Kranzler 1991; Skinner 1982), which assessed problematic alcohol use and problematic drug use other than alcohol and tobacco, respectively, applied a 12-month assessment frame and were introduced into the survey instrument beginning in wave 2. Both measures demonstrated good validity and reliability (Cronbach’s α=0.93 for SMAST, Cronbach’s α=0.92 for DAST-10; Selzer, Vinokur, and van Rooijen 1975; Evren et al. 2013).

Data analysis

All analyses were performed in SAS (version 9.4). The final analytical sample consisted of participants who completed all four waves (n=301). First, we described prevalence and means of the outcome variables within each MCP transition group and at each wave. Second, the longitudinal analysis was implemented through two models. Model 1 included fitting a fixed effect regression model for each outcome with MCP transition group as a between-subject effect and wave as a within-subject effect. Model 2 included fitting a fixed effects regression model for each outcome with MCP transition group and self-reported medical cannabis use (longitudinal summary variable) as between-subject effects to estimate independent effect of self-reported medical cannabis use and assess the potential impact of self-reported medical cannabis use on MCP transition group estimates. Both models used either logistic regression for binary outcomes or negative binomial regression for count outcomes (i.e., cannabis days, SDS, DAST, and SMAST). Regression models were adjusted for key demographic variables (i.e., age, assigned sex at birth, race/ethnicity) whenever there was a statistically significant association (p<0.05) with either outcome variable in at least two waves or MCP transition group variable or both.

RESULTS

The analytical sample (n=301) was not statistically different from the wave 1 sample (n=366) across age, assigned sex at birth or race/ethnicity (Lankenau et al. 2017a; Fedorova et al. 2020). The sample was predominantly male (64.8%), Hispanic/Latinx (44.1%) with a mean wave 1 age of 21.2 years (range 18-26). Mean age of first cannabis use was 15.3 years, and the majority reported having some college education or above (73.4%) and being employed (68.8%) at wave 1.

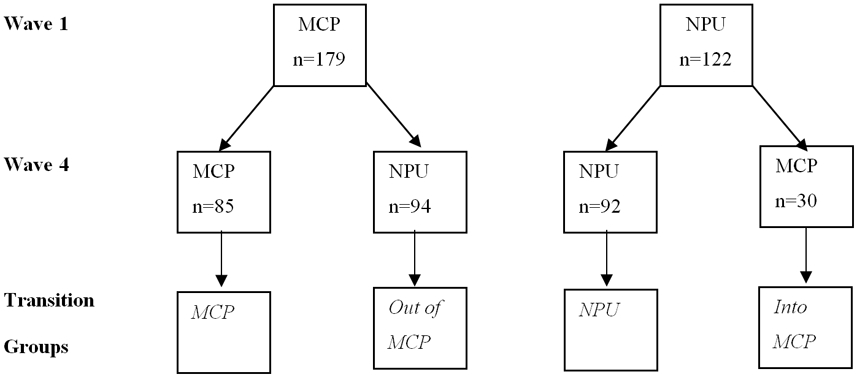

Among the 179 MCPs and 122 NPUs recruited at wave 1 (pre-legalization), only 47.5% of MCPs remained MCPs at wave 4 (post-legalization), while 73.8% of wave 1 NPUs remained NPUs at wave 4. Among the four transition groups (see Figure 1), Out of MCP was the largest (31.2%, n=94), followed by NPU (30.6%, n=92), MCP (28.2%, n=85) and Into MCP (10.0%, n=30). Among these four transition groups, we did not find statistically significant differences across demographic characteristics. Cannabis legalization (36.2%) and reduced/stopped cannabis use (27.6%) were the most common reasons for transitioning out of MCP. Having physical or psychological health conditions (43.3%), recreational access to cannabis (40.0%), and protection against arrest (33.3%) were the key reasons for transitioning into MCP (data not shown).

Figure 1. Medical cannabis patient transition groups among young adult cannabis users in Los Angeles (n=301).

MCP – medical cannabis patients; NPU – non-patient users.

Days of cannabis use were greatest within MCP group in all waves compared to other groups (see Table 1). Days of cannabis use increased by wave 4 for Into MCP group and decreased for other groups. A majority of participants, who reported they stopped using cannabis for one or more waves, was among Out of MCP and NPU groups; no one from Into MCP group reported stopping cannabis use. Concentrate use was highest among MCP group at each wave and declined or stayed at the same level by wave 4 for all groups except Into MCP group. Self-reported medical cannabis use was highest within MCP group in waves 1-3 (exceeded by Into MCP group in wave 4) and increased for all groups except Out of MCP group. DUIC was generally highest among MCP and remained relatively consistent across all four waves, while it decreased for all other groups. SDS scores were highest among MCP and increased between waves 1 and 4 for all groups. Illicit drug use, polydrug use, cigarette and e-cigarette use were generally higher among Into MCP and Out of MCP groups, and alcohol use was highest among Out of MCP group (see Table 2).

Table 1.

Past 90-day cannabis practices by MCP transition group at each wave among young adult cannabis users in Los Angeles (n=301).

| Total n=301 %(n) |

MCP n=85 %(n) |

Into MCP n=30 %(n) |

Out of MCP n=94 %(n) |

NPU n=92 %(n) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Cannabis days (mean, SD) |

|||||

| Wave 1 | 69.2(26.2) | 79.0(19.2) | 64.2(29.4) | 73.1(23.8) | 57.8(24.9) |

| Wave 2 | 64.7(30.9) | 77.6(22.9) | 64.9(30.2) | 62.4(32.3) | 54.9(32.6) |

| Wave 3 | 60.9(33.3) | 78.6(19.3) | 64.8(29.2) | 54.3(34.9) | 49.9(36.5) |

| Wave 4 | 53.8(36.7) | 69.1(31.3) | 68.4(29.7) | 46.9(36.9) | 42.4(37.4) |

| Did not use cannabis | |||||

| Wave 1 | 0.0(0) | 0.0(0) | 0.0(0) | 0.0(0) | 0.0(0) |

| Wave 2 | 4.0(12) | 0.0(0) | 0.0(0) | 7.4(7) | 5.4(5) |

| Wave 3 | 9.0(27) | 1.2(1) | 0.0(0) | 12.8(12) | 15.2(14) |

| Wave 4 | 8.3(25) | 2.4(2) | 0.0(0) | 11.7(11) | 13.0(12) |

| Concentrates use 1 | |||||

| Wave 1 | 58.1(175) | 70.6(60) | 50.0(15) | 61.7(58) | 45.7(42) |

| Wave 2 | 58.8(170) | 67.1(57) | 63.3(19) | 57.5(50) | 50.6(44) |

| Wave 3 | 61.7(169) | 72.6(61) | 70.0(21) | 58.5(48) | 50.0(39) |

| Wave 4 | 54.7(151) | 63.9(53) | 60.0(18) | 53.0(44) | 45.0(36) |

| Self-reported medical cannabis use 1 | |||||

| Wave 1 | 22.9(69) | 27.1(23) | 20.0(6) | 26.6(25) | 16.3(15) |

| Wave 2 | 25.3(73) | 32.9(28) | 20.0(6) | 25.3(22) | 19.5(17) |

| Wave 3 | 22.6(62) | 34.5(29) | 16.7(5) | 18.3(15) | 16.7(13) |

| Wave 4 | 25.4(65) | 31.6(24) | 32.1(9) | 20.0(16) | 22.2(16) |

| Self-reported medical cannabis use2 (mean, SD) | 0.9(1.2) | 1.2(1.4) | 0.9(1.0) | 0.8(1.1) | 0.7(1.0) |

| DUIC 1 | |||||

| Wave 1 | 60.9(182) | 63.9(53) | 63.3(19) | 64.9(61) | 53.3(49) |

| Wave 2 | 56.0(159) | 63.1(53) | 56.7(17) | 54.1(46) | 50.6(43) |

| Wave 3 | 61.0(163) | 68.8(55) | 58.6(17) | 60.0(48) | 55.1(43) |

| Wave 4 | 53.1(144) | 63.4(52) | 44.8(13) | 56.8(46) | 41.8(33) |

| SDS1 (mean, SD) | |||||

| Wave 1 | 2.5(2.7) | 2.8(2.9) | 2.2(2.3) | 2.7(3.0) | 2.1(2.3) |

| Wave 2 | 2.7(2.6) | 3.0(2.4) | 2.3(2.6) | 2.4(2.3) | 2.9(3.2) |

| Wave 3 | 2.8(2.8) | 3.1(2.5) | 2.1(2.2) | 2.5(2.6) | 2.9(3.4) |

| Wave 4 | 2.9(3.0) | 3.3(2.8) | 3.2(3.1) | 2.8(3.1) | 2.5(3.0) |

Past 90-day cannabis users.

Longitudinal summary variable. MCP – medical cannabis patients; NPU – non-patient users; DUIC – driving under influence of cannabis; SDS – Severity of Dependence Scale (cannabis).

Table 2.

Past 90-day other drug use by MCP transition group at each wave among young adult cannabis users in Los Angeles (n=301).

| Total n=301 %(n) |

MCP n=85 %(n) |

Into MCP n=30 %(n) |

Out of MCP n=94 %(n) |

NPU n=92 %(n) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illicit drug use | |||||

| Wave 1 | 31.9(96) | 35.3(30) | 40.0(12) | 34.0(32) | 23.9(22) |

| Wave 2 | 33.2(100) | 27.1(23) | 43.3(13) | 38.3(36) | 30.4(28) |

| Wave 3 | 30.2(91) | 29.4(25) | 30.0(9) | 37.2(35) | 23.9(22) |

| Wave 4 | 25.2(76) | 21.2(18) | 40.0(12) | 29.8(28) | 19.6(18) |

| Rx drug misuse | |||||

| Wave 1 | 23.3(70) | 18.8(16) | 33.3(10) | 24.5(23) | 22.8(21) |

| Wave 2 | 18.6(56) | 17.6(15) | 26.7(8) | 21.3(20) | 14.1(13) |

| Wave 3 | 17.9(54) | 16.5(14) | 26.7(8) | 19.1(18) | 15.2(14) |

| Wave 4 | 15.6(47) | 10.6(9) | 16.7(5) | 20.2(19) | 15.2(14) |

| Polydrug use 1,2 | |||||

| Wave 1 | 25.9(78) | 27.1(23) | 40.0(12) | 24.5(23) | 21.7(20) |

| Wave 2 | 26.3(76) | 28.2(24) | 30.0(9) | 29.9(26) | 19.5(17) |

| Wave 3 | 27.0(74) | 28.6(24) | 33.3(10) | 35.4(29) | 14.1(11) |

|

DAST3 (mean, SD) |

|||||

| Wave 2 | 2.2(2.1) 3.0 | 2.1(2.0) | 2.5(2.4) | 2.2(2.1) | 2.3(2.2) |

| Wave 3 | 2.2(2.3) 2.9 | 2.2(2.2) | 2.4(2.4) | 2.5(2.3) | 1.9(2.2) |

| Wave 4 | 1.8(2.2) 2.7 | 1.6(1.9) | 2.5(2.8) | 2.0(2.4) | 1.5(2.1) |

|

SMAST3 (mean, SD) |

|||||

| Wave 2 | 1.8(1.7) 1.8 | 1.9(1.9) | 2.0(1.7) | 1.6(1.6) | 1.9(1.6) |

| Wave 3 | 2.0(2.1) 2.0 | 2.0(2.0) | 2.4(2.2) | 1.9(2.5) | 2.0(1.8) |

| Wave 4 | 2.1(2.4) 2.4 | 1.9(2.0) | 2.2(2.3) | 2.1(2.5) | 2.3(2.6) |

| Alcohol | |||||

| Wave 1 | 81.4(245) | 84.7(72) | 83.3(25) | 85.1(80) | 73.9(68) |

| Wave 2 | 79.7(240) | 76.5(65) | 80.0(24) | 87.2(82) | 75.0(69) |

| Wave 3 | 75.7(228) | 76.5(65) | 66.7(20) | 79.8(75) | 73.9(68) |

| Wave 4 | 52.8(158) | 56.0(47) | 53.3(16) | 53.8(50) | 48.9(45) |

| Cigarettes | |||||

| Wave 1 | 45.8(138) | 44.7(38) | 50.0(15) | 45.7(43) | 45.7(42) |

| Wave 2 | 45.8(138) | 38.8(33) | 53.3(16) | 47.9(45) | 47.8(44) |

| Wave 3 | 40.2(121) | 40.0(34) | 36.7(11) | 45.7(43) | 35.9(33) |

| Wave 4 | 34.7(104) | 34.1(29) | 48.3(14) | 37.2(35) | 28.3(26) |

| E-cigarettes | |||||

| Wave 1 | 29.9(90) | 30.6(26) | 46.7(14) | 33.0(31) | 20.7(19) |

| Wave 2 | 19.7(59) | 10.7(9) | 26.7(8) | 27.7(6) | 17.4(16) |

| Wave 3 | 14.7(44) | 7.1(6) | 20.0(6) | 22.3(21) | 12.0(11) |

| Wave 4 | 12.3(37) | 12.9(11) | 13.3(4) | 16.0(15) | 7.7(7) |

Past 90-day cannabis users.

Outcome was not assessed in wave 4.

Outcomes were not assessed in wave 1.

MCP – medical cannabis patients; NPU – non-patient users; DAST – Drug Abuse Screening Test; SMAST – Short Michigan Alcohol Screening Test.

In the adjusted longitudinal Model 1, MCP, relative to NPU, reported greater days of cannabis use, and had greater odds of concentrate use (p<0.001), self-reported medical cannabis use (p<0.01), DUIC, and polydrug use (p<0.05) (see Table 3). Similarly, compared to NPU, Into MCP reported greater days of cannabis use (p<0.01) and had greater odds of polydrug use (p<0.05). Out of MCP reported greater days of cannabis use and had greater odds of using alcohol and e-cigarettes (p<0.05).

Table 3.

Repeated measures analyses of cannabis practices and other drug use by MCP transition group among young adult cannabis users in Los Angeles (n=301).

| Outcomes | AOR (95% CI) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||||||||

| Patient Status1 | Wave2 | Patient Status1 | Self- reported medical cannabis use3 |

|||||||

| MCP | Into MCP |

Out of MCP |

Wave 2 | Wave 3 | Wave 4 | MCP | Into MCP |

Out of MCP |

||

| Cannabis practices | ||||||||||

| Cannabis days4 | 1.49*** (1.33-1.67) |

1.29** (1.09-1.52) |

1.15* (1.00-1.32) |

0.93** (0.89-0.98) |

0.87*** (0.82-0.93) |

0.77*** (0.71-0.83) |

1.45*** (1.30-1.62) |

1.27** (1.07-1.50) |

1.15* (1.00-1.31) |

1.05** (1.02-1.08) |

| Concentrates use5 | 2.33*** (1.52-3.57) |

1.67 (0.89-3.13) |

1.49 (0.98-2.27) |

1.01 (0.77-1.32) |

1.11 (0.83-1.49) |

0.83 (0.62-1.13) |

2.36*** (1.54-3.59) |

1.67 (0.89-3.13) |

1.49 (0.98-2.27) |

0.98 (0.85-1.13) |

| Self-reported medical cannabis use | 2.02** (1.23-3.32) |

1.23 (0.66-2.28) |

1.31 (0.80-2.14) |

1.13 (0.83-1.54) |

0.98 (0.69- 1.39) |

1.14 (0.80-1.63) |

- | - | - | - |

| DUIC6 | 1.85* (1.13-3.02) |

1.20 (0.59-2.42) |

1.25 (0.80-1.97) |

0.79 (0.61-1.01) |

0.97 (0.77-1.22) |

0.69** (0.53-0.90) |

2.23** (1.30-3.82) |

1.28 (0.64-2.54) |

1.33 (0.84-2.10) |

0.71*** (0.59-0.86) |

| SDS4 | 1.20 (0.96-1.53) |

0.95 (0.68-1.34) |

1.03 (0.80-1.33) |

1.09 (0.97-1.23) |

1.09 (0.96-1.25) |

1.18* (1.03- 1.35) |

1.27 (1.00-1.61) |

0.98 (0.69-1.38) |

1.05 (0.81-1.35) |

0.92* (0.85-1.00) |

| Other drug use | ||||||||||

| Illicit drug use6 | 1.21 (0.74-1.95) |

1.80 (1.00-3.23) |

1.48 (0.93-2.38) |

1.08 (0.82-1.43) |

0.94 (0.70-1.26) |

0.72* (0.53-0.99) |

1.36 (0.83-2.24) |

1.89* (1.06-3.35) |

1.54 (0.96-2.47) |

0.77** (0.65-0.92) |

| Rx drug misuse6 | 0.91 (0.55-1.51) |

1.63 (0.83-3.20) |

1.20 (0.73-1.97) |

0.78 (0.55-1.11) |

0.73 (0.50-1.06) |

0.61* (0.41-0.90) |

0.95 (0.57-1.58) |

1.64 (0.84-3.20) |

1.22 (0.75-2.00) |

0.91 (0.76-1.09) |

| Polydrug use6 | 1.67* (0.99-2.82) |

2.07* (1.01-4.21) |

1.54 (0.90-2.63) |

0.99 (0.73-1.35) |

1.02 (0.73-1.42) |

- | 1.89* (1.11-3.24) |

2.18* (1.07-4.43) |

1.61 (0.94-2.75) |

0.77** (0.64-0.93) |

| DAST4-7 | 0.95 (0.74-1.24) |

1.21 (0.85-1.73) |

1.10 (0.86-1.41) |

- | 0.98 (0.88-1.10) |

0.79*** (0.68-0.90) |

0.99 (0.77-1.30) |

1.23 (0.86-1.76) |

1.12 (0.87-1.43) |

0.90* (0.82-0.99) |

| SMAST4,5,7 | 0.92 (0.72-1.17) |

1.04 (0.77-1.40) |

0.90 (0.70-1.17) |

- | 1.11 (0.99-1.24) |

1.16* (1.03-1.31) |

0.86 (0.68-1.10) |

1.01 (0.75-1.37) |

0.88 (0.68-1.15) |

1.09* (1.01-1.18) |

| Alcohol | 1.33 (0.85-2.06) |

1.15 (0.61-2.15) |

1.55* (1.01-2.36) |

0.90 (0.64-1.27) |

0.71 (0.50-1.03) |

0.26*** (0.18-0.36) |

1.43 (0.95-2.16) |

1.18 (0.66-2.11) |

1.59* (1.06-2.36) |

0.86* (0.76-0.99) |

| Cigarettes6 | 1.04 (0.63-1.70) |

1.34 (0.68-2.64) |

1.17 (0.73-1.89) |

1.01 (0.82-1.25) |

0.80 (0.62-1.02) |

0.62*** (0.49-0.80) |

1.16 (0.70-1.91) |

1.42 (0.72-2.81) |

1.23 (0.77-1.97) |

0.86 (0.72-1.02) |

| E-cigarettes5,6 | 1.09 (0.60-1.99) |

2.07 (0.97-4.43) |

1.87* (1.03-3.37) |

0.56*** (0.42-0.75) |

0.38*** (0.27-0.55) |

0.31*** (0.21-0.45) |

1.01 (0.56-1.81) |

1.90 (0.90-4.00) |

1.74 (0.98-3.07) |

1.10 (0.92-1.30) |

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p>0.001.

NPU is a reference group.

Wave 1 is a reference group.

Longitudinal summary variable.

Negative binomial distribution with adjusted incidence rate ratios as estimates.

Adjusted for assigned sex at birth.

Adjusted for non-Hispanic White.

Wave 2 is a reference group. AOR - adjusted odds ratio; MCP - medical cannabis patients; NPU - non-patient user; DUIC - driving under influence of cannabis; SDS - Severity of Dependence Scale (cannabis); DAST - Drug Abuse Screening Test; SMAST - Short Michigan Alcohol Screening Test.

Time effect was statistically significant for cannabis days, DUIC, illicit drug use, prescription drug misuse, alcohol, cigarette and e-cigarette use, and DAST scores, all indicating decline by wave 4 (post-legalization) (see Table 3). Conversely, SDS and SMAST scores showed statistically significant increases by wave 4.

In the adjusted longitudinal Model 2, which included self-reported medical cannabis use as another independent variable, MCP transition group effects were similar to those in Model 1 (see Table 3). Self-reported medical cannabis use was positively associated with cannabis use days (p<0.01) and SMAST scores (p<0.05), but negatively associated with DUIC (p<0.001), illicit drug and polydrug use (p<0.01), alcohol use, SDS and DAST scores (p<0.05).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study comparing changes in cannabis practices, other drug use and problematic drug use among young adult cannabis users who stayed MCPs or NPUs, and those who transitioned into or out of MCP status after cannabis was legalized for adult use in California. Conceptually, apart from MCP and NPU groups, we created two MCP transition groups, i.e., Into MCP and Out of MCP, to represent changes in legal access to medical cannabis and exposure to medical cannabis culture via medical cannabis dispensaries over time. Notably, we observed a steady movement of MCP participants recruited during wave 1 towards Out of MCP by wave 4, which is consistent with recent recreational cannabis legalization in California. Nevertheless, more than one third of our sample maintained MCP status or newly acquired a doctor’s medical cannabis recommendation by wave 4 (MCP plus Into MCP), which could be attributed to preserving a MCP identity (Lankenau et al. 2018) or anticipating benefits linked to MCP status, such as a sales tax exemption when purchasing cannabis.

Remarkably, we observed a significant reduction in the prevalence of almost all outcomes by wave 4 (i.e., cannabis days, DUIC, illicit drug use, prescription drug misuse, alcohol, cigarette and e-cigarette use) irrespective of transition group. These findings may point to a maturing out phenomenon whereby drug use is reduced as young adults age and learn alternative coping strategies (Chen and Kandel 1995; Winick 1962). The decline in the days of cannabis use is particularly striking given that wave 4 overlapped with the start of cannabis sales for adult use in California. Declines in licit and illicit drug use in our sample corroborate previous studies of young adults, which observed either post-legalization decline in use in Oregon or no significant changes in the rates of use in Washington (Kerr et al. 2017; Kerr, Bae, and Koval 2018; Miller, Rosenman, and Cowan 2017). Our finding of a significant decline in cannabis use frequency post-legalization contrasts with findings from cross-sectional studies of young adults (i.e., increases in use in Oregon and Washington, while no change in use in Colorado and California), possibly, due to differences in study population (college students versus young adult cannabis users), measurement (i.e., days of use versus prevalence of use), design (i.e., longitudinal cohort versus cross-sectional samples), or state-level differences in the stipulation and implementation of recreational cannabis laws (Anderson et al. 2019; Grigorian et al. 2019; Kan et al., 2020; Kerr et al. 2017; Kerr, Bae, and Koval 2018). By examining within-subject changes over time in this study, we expanded upon the findings from prior cross-sectional studies of the impact of recreational cannabis legalization on cannabis and other drug use, and DUIC rates.

MCP group reported highest cannabis use days while NPU group had the lowest cannabis days in all waves. Cannabis days increased for Into MCP group and decreased for Out of MCP group. Similar trends were observed for cannabis concentrate use. These findings are consistent with studies demonstrating higher cannabis use frequency (Compton et al. 2017; Lin et al. 2016; Woodruff and Shillington 2016) and use of cannabis concentrate among MCPs due to greater access to cannabis and its various forms through medical cannabis dispensaries (Lankenau et al. 2017b). Moreover, since MCPs, relative to NPUs, report more chronic health conditions where cannabis can be used to alleviate symptoms, greater use of cannabis and concentrate among MCP may reflect cannabis use to manage existing health conditions (Athey, Boyd, and Cohen 2017; Lankenau et al. 2018). Conversely, reduction in cannabis days among Out of MCP group is consistent with our earlier qualitative study demonstrating declining cannabis use among participants who let their medical cannabis recommendation expire (Lankenau et al. 2018). Additionally, we observed a decline in the DUIC rates for all groups, except MCP who had highest cannabis use days and whose health conditions might require cannabis administration throughout a day, including morning and daytime, before driving to school or work (Lankenau et al. 2017b; Sznitman 2017).

Similarly, self-reported medical cannabis use was highest among MCP and lowest among NPU, showing an increasing trend among all groups except Out of MCP. The decline in self-reported medical cannabis use by wave 4 among Out of MCP, who allowed their medical cannabis recommendation to expire, suggests the importance of a medical cannabis dispensary environment or identifying as MCP to maintain medical cannabis use (Lankenau et al. 2018). Remarkably, overall, while the proportion of MCPs declined post-legalization, self-reported medical cannabis use did not decline indicating continued medical cannabis use and the preservation of medical cannabis user identity even within a context of legal recreational cannabis use.

Into MCP and Out of MCP groups tended to have greater rates of other drug use in all categories compared to MCP and NPU across the four waves. In most cases, MCP did not differ from NPU regarding the rates of other drug use. For some participants within Into MCP and Out of MCP groups, sensation seeking may be one of the motives for greater cannabis and other drug use (Evans-Polce et al. 2018). Additionally, among Out of MCP group, cannabis may not have been effective in treating physical (e.g., pain) or mental (e.g., depression) health conditions so that they used other drugs to self-medicate for these conditions (Boys, Marsden, and Strang 2001; McCabe et al. 2007; Müller and Schumann 2011).

Self-reported medical cannabis use was positively associated with frequency of cannabis use, but negatively associated with a wide range of risk behaviors, including DUIC, problematic cannabis and other drug use, illicit drug use, polydrug use, and alcohol use. Overall, self-reported medical cannabis use appeared to be protective against other drug use in most cases which is consistent with previous research (Choi, Dinitto, and Marti 2017; Roy-Byrne et al. 2015).

Our findings have several implications for research and practice. Changes in MCP status, which are linked to legal access to cannabis via medical cannabis dispensaries (including access to a higher quality and greater variety of cannabis products), had a significant impact on cannabis use frequency, alternative form use, and DUIC (Reed et al. 2020). These results suggest that other states that increase access to cannabis through legalizing cannabis for medical or recreational purposes may experience a similar impact on cannabis use. Interestingly, membership in MCP and Into MCP groups was associated with increased likelihood of polydrug use but was not associated with any other type of drug use. Conversely, the negative association between self-reported medical cannabis and rates/severity of other drug use suggests that the medicalization of cannabis use, which may include education about medical uses of cannabis via dispensaries, has the potential to reduce the risk of other drug use within a population of young adult cannabis users. Finally, despite policy changes that legalized cannabis for all participants by wave 4, the frequency of cannabis and all other drug use decreased over the course of the study, which followed a natural history of drug use trajectories (Chen and Kandel 1995). Since age is a crucial variable in the natural history of drug use, it is important to monitor the effects of legalization and the role of medical motivations for cannabis use on other drug use among young adult cannabis users before and after reaching the legal age for access to recreational cannabis dispensaries.

Our study is a subject to several limitations. First, since our sample was not randomly selected, our findings may not be generalizable to all young adult cannabis users in Los Angeles. However, the sample was diverse in terms of age, sex, residency, and race/ethnicity representative of the racial/ethnic composition in Los Angeles with a high percentage of Hispanic/Latinx (Lankenau et al. 2019; US Census Bureau). Second, we cannot claim causal relationships between transition groups, self-reported medical cannabis use and outcomes since observational study design precluded us from controlling for all potential confounders that could have an impact on those relationships. However, given that data collection happened amidst recreational cannabis legalization, the observational longitudinal study was the most viable design to examine the potential impact of this policy change on drug using behaviors. Third, the change in the mode of administration from interviewer-administered surveys to self-administered online surveys in wave 4 could have affected how participants answered sensitive questions related to drug use. However, while we might expect higher social desirability bias and underreporting of drug use and other stigmatized behaviors in interviewer-administered surveys in waves 1-3, we observed reduction in those behaviors by wave 4. Lastly, this analysis does not capture the effects of the establishment of a legal market for cannabis on cannabis and other drug use since only one-fifth of wave 4 data was collected after legal sales of cannabis for adult use started.

Conclusion

In this longitudinal study, we found changes in cannabis use frequency, cannabis concentrate use and self-reported medical cannabis use as young adults transitioned into or out of MCP status after a change in cannabis policy. Importantly, we observed a significant decline in cannabis, licit and illicit drug use and DUIC after cannabis became legal for adult use in California, which supports a maturing out of drug use hypothesis despite changing norms and increased access to cannabis. The declining number of MCPs in our sample over time might be a reflection of either cannabis legalization for adult use or maturing out phenomenon, or both. On the other hand, the persistence of self-reported medical cannabis use over time among current users, even after recreational cannabis legalization, and its negative relationships with several drug use related outcomes are promising. As cannabis policies evolve towards greater liberalization and legalization in states across the U.S., future studies should continue to evaluate longitudinally the impact of medical and recreational cannabis policies on cannabis use rates and practices as well as other drug use among young adult cannabis users.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the project’s Community Advisory Board and the following individuals who supported the development of this manuscript: Miles McNeely, Megan Treese, Ali Johnson, Chaka Dodson, Maral Shahinian, Avat Kioumarsi, Salini Mohanti, Megan Reed and Alexander Kecojevic.

Funding

This research study was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse under Grant R01-DA034067.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

No potential competing interest was reported by the authors.

REFERENCES

- Anderson DM, Hansen B, Rees DI, and Sabia JJ. 2019. Association of marijuana laws with teen marijuana use. JAMA Pediatrics 173 (9): 879–81. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Athey N, Boyd N, and Cohen E. 2017. Becoming a medical marijuana user: Reflections on Becker’s trilogy — learning techniques, experiencing effects, and perceiving those effects as enjoyable. Contemporary Drug Problems 44 (3): 212–31. 10.1177/0091450917721206. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aydelotte JD, Mardock AL, Mancheski CA, Quamar SM, Teixeira PG, Brown CVR, and Brown LH. 2019. Fatal crashes in the 5 years after recreational marijuana legalization in Colorado and Washington. Accident Analysis and Prevention 132: 105284. 10.1016/j.aap.2019.105284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg CJ, Daniel CN, Vu M, Li J, Martin K, and Le L. 2018. Marijuana use and driving under the influence among young adults: a socioecological perspective on risk factors. Substance Use and Misuse 53 (3): 370–80. 10.1080/10826084.2017.1327979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biernacki P, and Waldorf D. 1981. Snowball sampling: Problems and techniques of chain referral sampling. Sociological Methods & Research 10 (2): 141–63. 10.1177/004912418101000205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bohn MJ, Babor TF, and Kranzler HR. 1991. Validity of the Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST-10) in inpatient substance abusers. Problems of Drug Dependence 119: 233–35. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd CJ, Veliz PT, and McCabe SE. 2015. Adolescents’ use of medical marijuana: A secondary analysis of Monitoring The Future data. Journal of Adolescent Health 57 (2): 241–44. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boys A, Marsden J, and Strang J. 2001. Understanding reasons for drug use amongst young people: A functional perspective. Health Education Research 16 (4): 457–69. 10.1093/her/16.4.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- California Code. Health and Safety Code - HSC § 11362.5.

- California Department of Public Health. Manufactured Cannabis Safety Branch. Legislation. Last Modified January 29, 2020. Accessed December 22, 2020. https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/CEH/DFDCS/MCSB/Pages/Legislation.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. 2018. 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Rockville, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Cerdá M, Mauro C, Hamilton A, Levy NS, Santaella-tenorio J, Hasin D, Wall MM, Keyes KM, and Martins SS. 2020. Association between recreational marijuana legalization in the United States and changes in marijuana use and cannabis use disorder from 2008 to 2016. JAMA Psychiatry 77 (2): 165–71. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.3254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan NW, Burkhardt J, and Flyr M. 2020. The effects of recreational marijuana legalization and dispensing on opioid mortality. Economic Inquiry 58 (2): 589–606. 10.1111/ecin.12819. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chapkis W, and Webb RJ. 2008. Dying to get high: Marijuana as medicine. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chen K, and Kandel DB. 1995. The natural history of drug use from adolescence to the mid-thirties in a general population sample. American Journal of Public Health 85 (1): 41–47. 10.2105/ajph.85.1.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi NG, Dinitto DM, and Marti CN. 2017. Nonmedical versus medical marijuana use among three age groups of adults: associations with mental and physical health status. The American Journal on Addictions 26 (7): 697–706. 10.1111/ajad.12598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton WM, Han B, Hughes A, Jones CM, and Blanco C. 2017. Use of marijuana for medical purposes among adults in the United States. JAMA 317 (2): 209–11. 10.1001/jama.2016.18900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cranford JA, Bohnert KM, Perron BE, Bourque C, and Ilgen M. 2016. Prevalence and correlates of “Vaping” as a route of cannabis administration in medical cannabis patients. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 169: 41–47. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniulaityte R, Lamy FR, Barratt M, Nahhas RW, Martins SS, Boyer EW, Sheth A, and Carlson RG. 2017. Characterizing marijuana concentrate users: A web-based survey. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 178 (June): 399–407. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.05.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Polce RJ, Schuler MS, Schulenberg JE, and Patrick ME. 2018. Gender- and age-varying associations of sensation seeking and substance use across young adulthood. Addictive Behaviors 84: 271–77. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evren C, Can Y, Yilmaz A, Ovali E, Cetingok S, Karabulut V, and Mutlu E. 2013. Psychometric properties of the Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST-10) in heroin dependent adults and adolescents with drug use disorder. The Journal of Psychiatry and Neurological Sciences 26 (4): 351–59. 10.5350/DAJPN2013260404. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fedorova EV, Schrager SM, Robinson LF, Cepeda A, Wong CF, Iverson E, and Lankenau SE. 2019. Illicit drug use and prescription drug misuse among young adult medical cannabis patients and non-patient users in Los Angeles. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 198: 21–27. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedorova EV, Schrager SM, Robinson LF, Roth AM, Wong CF, Iverson E, and Lankenau SE. 2020. Developmental trajectories of illicit drug use, prescription drug misuse and cannabis practices among young adult cannabis users in Los Angeles. Drug and Alcohol Review 39: 743–52. 10.1111/dar.13078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigorian A, Lester E, Lekawa M, Figueroa C, Kuza CM, Dolich M, Schubl SD, Jr CB, and Nahmias J. 2019. Marijuana use and outcomes in adult and pediatric trauma patients after legalization in California. The American Journal of Surgery 218 (6): 1189–94. 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2019.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall W 2015. What has research over the past two decades revealed about the adverse health effects of recreational cannabis use? Addiction 110 (1): 19–35. 10.1111/add.12703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen B, Miller K, and Weber C. 2020. Early evidence on recreational marijuana legalization and traffic fatalities. Economic Inquiry 58 (2): 547–68. 10.1111/ecin.12751. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Sarvet AL, Cerdá M, Keyes KM, Stohl M, Galea S, and Wall MM. 2017. US adult illicit cannabis use, cannabis use disorder, and medical marijuana laws 1991-1992 to 2012-2013. JAMA Psychiatry 74 (6): 579–88. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haug NA, Padula CB, Sottile JE, Vandrey R, Heinz AJ, and Bonn-Miller MO. 2017. Cannabis use patterns and motives: A comparison of younger, middle-aged, and older medical cannabis dispensary patients. Addictive Behaviors 72: 14–20. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones J, Jones KN, and Peil J. 2018. The impact of the legalization of recreational marijuana on college students. Addictive Behaviors 77: 255–59. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kan E, Beardslee J, Frick PJ, Steinberg L, and Cauffman E. 2020. Marijuana Use Among Justice-Involved Youths After California Statewide Legalization , 2015 – 2018. American Journal of Public Health 110 (9): 1386–92. 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB, Yamaguchi K, and Chen K. 1992. Stages of progression in drug involvement from adolescence to adulthood: further evidence for the gateway theory. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 53 (5): 447–57. 10.15288/jsa.1992.53.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr DCR, Bae H, and Koval AL. 2018. Oregon recreational marijuana legalization: Changes in undergraduates’ marijuana use rates from 2008 to 2016. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 32 (6): 670–78. 10.1037/adb0000385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr DCR, Bae H, Phibbs S, and Kern AC. 2017. Changes in undergraduates’ marijuana, heavy alcohol and cigarette use following legalization of recreational marijuana use in Oregon. Addiction 112 (11): 1992–2001. 10.1111/add.13906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane TJ, and Hall W. 2019. Traffic fatalities within US states that have legalized recreational cannabis sales and their neighbours. Addiction 114 (5): 847–56. 10.1111/add.14536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lankenau SE, Ataiants J, Mohanty S, Schrager S, Iverson E, and Wong CF. 2017a. Health conditions and motivations for marijuana use among young adult medical marijuana patients and non-patient marijuana users. Drug and Alcohol Review 37 (2): 237–46. 10.1111/dar.12534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lankenau SE, V Fedorova E, Reed M, Schrager SM, Iverson E, and Wong CF. 2017b. Marijuana practices and patterns of use among young adult medical marijuana patients and non-patient marijuana users. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 170 (January): 181–88. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lankenau SE, Kioumarsi A, Reed M, Mcneeley M, Iverson E, and Wong CF. 2018. Becoming a medical marijuana user. International Journal of Drug Policy 52: 62–70. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lankenau SE, Tabb LP, Kioumarsi A, Ataiants J, Wong CF, and Iverson E. 2019. Density of medical marijuana dispensaries and current marijuana use among young adult marijuana users in Los Angeles. Substance Use & Misuse 54 (11): 1862–74. 10.1080/10826084.2019.1618332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin LA, Ilgen MA, Jannausch M, and Bohnert KM. 2016. Comparing adults who use cannabis medically with those who use recreationally: Results from a national sample. Addictive Behaviors 61: 99–103. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin G, Copeland J, Gates P, and Gilmour S. 2006. The Severity of Dependence Scale (SDS) in an adolescent population of cannabis users: Reliability, validity and diagnostic cut-off. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 83 (1): 90–93. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins SS, Santaella J, Pacek LR, Keyes K, Cerda M, Hasin DS, and Galea S. 2015. Are medical marijuana users different than recreational marijuana users? Drug and Alcohol Dependence 156: e141. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.07.385. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, Cranford JA, Boyd CJ, and Teter CJ. 2007. Motives, diversion and routes of administration associated with nonmedical use of prescription opioids. Addictive Behaviors 32 (3): 562–75. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metrik J, Bassett SS, Aston ER, Jackson KM, and Borsari B. 2018. Medicinal versus recreational cannabis use among returning veterans. Translational Issues in Psychological Science 4 (1): 6–20. 10.1037/tps0000133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AM, Rosenman R, and Cowan BW. 2017. Recreational marijuana legalization and college student use: Early evidence. SSM - Population Health 3: 649–57. 10.1016/j.ssmph.2017.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller CP, and Schumann G. 2011. Drugs as instruments: A new framework for non-addictive psychoactive drug use. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 34 (6): 293–347. 10.1017/S0140525X11000057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunberg H, Kilmer B, Pacula RL, and Burgdorf JR. 2011. An analysis of applicants presenting to a medical marijuana specialty practice in California. Journal of Drug Policy Analysis 4 (1): 387–93. 10.2202/1941-2851.1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogborne AC, Smart RG, and Adlaf EM. 2000. Self-reported medical use of marijuana: a survey of the general population. Canadian Medical Association Journal 162 (12): 1685–86. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacula R, Jacobson M, and Maksabedian EJ. 2016. In the weeds: a baseline view of cannabis use among legalizing states and their neighbours. Addiction 111 (6): 973–80. 10.1111/add.13282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J-Y, and Wu L-T. 2017. Prevalence, reasons, perceived effects and correlates of medical marijuana use: A review. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 177: 1–13. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed M, Kioumarsi A, Ataiants J, V Fedorova E, Wong CF, and Lankenau SE. 2020. Marijuana sources in a medical marijuana environment: dynamics in access and use among a cohort of young adults in Los Angeles , California. Drugs: Education , Prevention and Policy 27 (1): 69–78. 10.1080/09687637.2018.1557595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinarman C, Nunberg H, Lanthier F, and Heddleston T. 2011. Who are medical marijuana patients? Population characteristics from nine California assessment clinics. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 43 (2): 128–35. 10.1080/02791072.2011.587700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richmond MK, Pampel FC, Rivera LS, Broderick KB, Reimann B, and Fischer L. 2015. Frequency and risk of marijuana use among substance-using health care patients in Colorado with and without access to state legalized medical marijuana. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 47 (1): 1–9. 10.1080/02791072.2014.991008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy-Byrne P, Maynard C, Bumgardner K, Krupski A, Dunn C, West II, Donovan D, Atkins DC, and Ries R. 2015. Are medical marijuana users different from recreational users? The view from primary care. American Journal on Addictions 24 (7): 599–606. 10.1111/ajad.12270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santaella-tenorio J, Mauro CM, Wall MM, Kim JH, Cerdá M, Keyes KM, Hasin DS, Galea S, and Martins SS. 2017. US traffic fatalities, 1985–2014, and their relationship to medical marijuana laws. American Journal of Public Health 107 (2): 336–43. 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selzer ML, Vinokur A, and van Rooijen L. 1975. A self-administered Short Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (SMAST). Journal of Studies on Alcohol 36 (1): 117–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sifaneck SJ, and Kaplan CD. 1995. Keeping off, stepping on and stepping off: the steppingstone theory reevaluated in the context of the Dutch cannabis experience. Contemporary Drug Problems 22 (3): 483–512. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner HA 1982. The Drug Abuse Screening Test. Addictive Behaviors 7: 363–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swift A 2016. Support for Legal Marijuana Use Up to 60% in U.S. Gallup Social Issues, 98–103. [Google Scholar]

- Sznitman SR 2017. Do recreational cannabis users, unlicensed and licensed medical cannabis users form distinct groups? International Journal of Drug Policy 42: 15–21. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2016.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JS, Rodriguez A, Pedersen ER, Seelam R, Shih RA, and D’Amico EJ. 2019. Greater risk for frequent marijuana use and problems among young adult marijuana users with a medical marijuana card. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 194: 178–83. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Census Bureau. Los Angeles City, California. Last Modified July 1, 2019. Accessed December 22, 2020. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/losangelescitycalifornia#. [Google Scholar]

- Watters JK, and Biernacki P. 1989. Targeted sampling: Options for the study of hidden populations. Social Problems 36 (4): 416–30. [Google Scholar]

- Winick C 1962. Maturing out of narcotic addiction. Bulletin on Narcotics 14 (1): 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Woodruff SI, and Shillington AM. 2016. Sociodemographic and drug use severity differences between medical marijuana users and non-medical users visiting the emergency department. American Journal on Addictions 25 (5): 385–91. 10.1111/ajad.12401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]