Abstract

Purpose

Unhealthy eating is a major modifiable risk factor for non-communicable diseases and obesity, and remote acculturation to U.S. culture is a recently identified cultural determinant of unhealthy eating among adolescents and families in low/middle-income countries. This small-scale RCT evaluated the efficacy of the “JUS Media? Programme”, a food-focused media literacy intervention promoting healthier eating among remotely acculturating adolescents and mothers in Jamaica.

Methods

Gender-stratified randomization of 184 eligible early adolescents and mothers in Kingston, Jamaica (i.e., 92 dyads: Madolescent.age=12.79 years, 51% girls) determined 31 ‘Workshops-Only’ dyads, 30 ‘Workshops+SMS/texting’ dyads, and 31 ‘No-Intervention-Control’ dyads. Nutrition knowledge (food group knowledge), nutrition attitudes (stage of nutritional change), and nutrition behavior (24-hr recall) were primary outcomes assessed at four timepoints (T1/baseline, T2, T3, T4) across five months using repeated measures ANCOVAs.

Results

Compared to control, families in one or both intervention groups demonstrated significantly higher nutrition knowledge (T3 adolescents, T4 mothers: mean differences 0.79–1.08 on a 0–6 scale, 95% CI 0.12 to 1.95, Cohen’s ds=0.438–0.630); were more prepared to eat fruit daily (T3 adolescents and mothers: 0.36–0.41 on a 1–5 scale, 95% CI 0.2 to 0.77, d=.431-.493); and were eating more cooked vegetables (T2 and T4 adolescents and T4 mothers: 0.21–0.30 on a 0–1 scale, 95% CI 0.02 to 0.55, ds=.470–0.642). Post-intervention focus groups (6-month-delay) revealed major positive impacts on participants’ health and lives more broadly.

Conclusions

A food-focused media literacy intervention for remotely acculturating adolescents and mothers can improve nutrition. Replication in Jamaica and extension to the Jamaican diaspora would be useful.

Keywords: Remote Acculturation, Media Literacy, Advertising, Nutrition, Obesity, Transdisciplinary, Globalization, Jamaica, Adolescent Health, Family Intervention

Globalization has given rise to a new psychocultural determinant of health for youth and families, “remote acculturation”: internalizing a distant, non-native cultural identity and lifestyle (1). Remote acculturation (RA) was first documented in Jamaica, where U.S.-identified youth and mothers watch more hours of U.S. cable daily, including embedded junk food advertising, in turn, eating more unhealthy food compared to their culturally traditional peers (2). However, recent research shows that high media literacy – being more critical of the content and intent of food advertising – can weaken/nullify this RA-unhealthy eating association (3). A transdisciplinary food-focused media literacy intervention, blending acculturation psychology, media/advertising, and nutrition sciences – the ‘J(amaican and) U(nited) S(tates) Media?, Programme’ – was developed to promote healthier eating among U.S-identified Jamaican adolescents and mothers by improving their critical thinking skills about food advertising (4). This study evaluated the efficacy of this intervention using a small-scale randomized controlled trial (RCT). Jamaican views of U.S. culture derive mainly from mainstream European American norms observed through media (5); therefore, our use of ‘U.S.’ henceforth refers to European American.

Obesity has multi-level ‘cell-to-society’ predictors (6) and the obesity epidemic is exacerbated by economic vulnerabilities in low/middle-income countries (7). The nutrition transition from traditional whole foods to highly processed and energy-dense convenience foods is a major contributor to rising obesity rates in these countries (8). Rising incomes and lowered food prices have had the unintended effect that many global families now have disposable income to purchase U.S.-style junk food (9). Companies have also turned intensive global marketing efforts to the Majority World (10).

Western media play a role in rising overweight and obesity among children and adolescents globally (8,11). An international meta-analysis of 29 RCTs demonstrated that exposure to junk food advertising increases children’s/adolescents’ consumption of energy dense, low nutrition products (12). Comprising one-third of the global media/entertainment industry (13), the United States exports cable television, movies, music, games, and streaming services. The Caribbean region has experienced an explosion in access to fast food and U.S. media, including U.S cable TV with advertising intact (14), and now has one of the world’s highest adolescent mean BMI scores (15). Studies in Jamaica consistently show that food and beverage advertising is unavoidable and promotes largely unhealthy options, especially for children/adolescents and mothers (16, 17).

RA of global youth towards U.S. culture puts them at higher risk of unhealthy eating (1,2,18). A cross-sectional study of 330 adolescent-mother dyads in Kingston, Jamaica found that, controlling for socioeconomic status, adolescents and mothers who identified more strongly with U.S. culture and found U.S. media more enjoyable, watched more U.S. cable television and ate more unhealthily (2). Together with experimental research findings from advertising (12), this suggests a negative influence of U.S.-produced food advertising on their diets. Awareness of the manipulative intent of food advertising, part of media literacy, may disrupt the negative influence of media on adolescents’ dietary habits (3) and health (19); hence, the need for food-focused media literacy training among adolescents (20), a prime target for advertisers (21). Multiple initiatives have promoted healthier food in Jamaica (22), but did not address RA or media literacy, which led to the development of the JUS Media? Programme (4).

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of JUS Media? in Jamaica using an RCT with follow-up focus groups. To our knowledge, no prior RCTs have evaluated parent-adolescent food-focused media literacy workshops at post-intervention and after delay, nor has SMS been used, especially in a low/middle-income country. We expected participants who received the intervention workshops to have better nutrition knowledge, attitudes, and behavior and higher food-focused media literacy post-intervention compared to the control group. We also expected participants receiving the workshops+SMS to benefit most. This intervention was designed to target adolescents (both genders) and mothers; therefore, no gender/generation differences were expected.

Methods

The JUS Media? Programme Intervention

The JUS Media? Programme involves transdisciplinary food-focused media literacy training for remotely acculturating adolescents and mothers. The question mark communicates the goal to teach individuals to question health and lifestyle messages embedded in food advertising. Mothers are included because they overwhelmingly manage family nutrition, and Jamaican research shows that their media and nutrition habits are linked to adolescents’ (2). The JUS Media? Programme (4) originated from a major cultural and developmental adaptation of a successful food-focused media literacy intervention designed for U.S. schoolchildren (23), an approach used successfully in family-based format (24). JUS Media? – described in detail elsewhere (4) – includes two 90-minute face-to-face interactive workshops for adolescents and mothers, followed by eight weeks of SMS/text messaging to reinforce workshop themes.

Setting and Sample

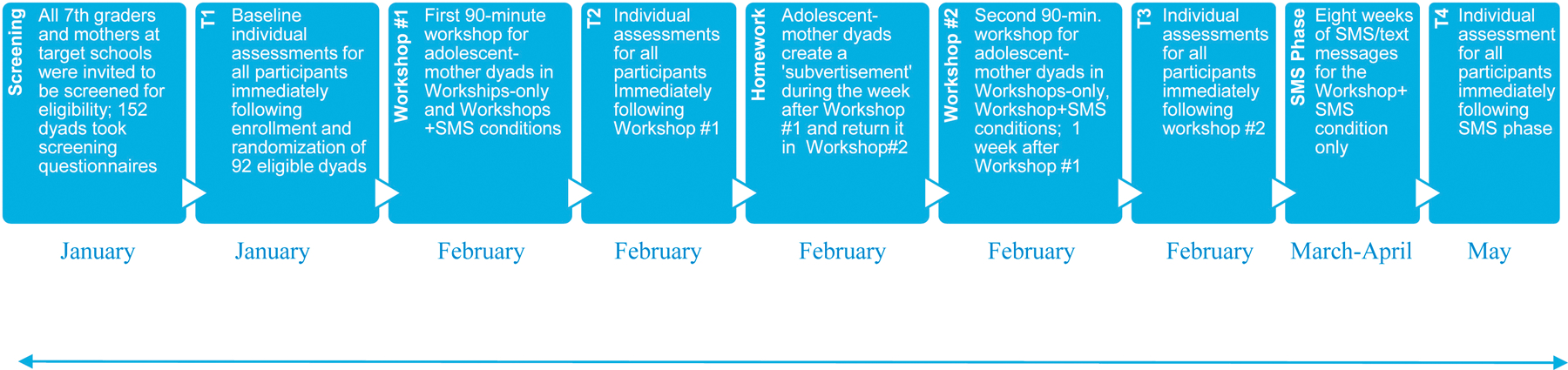

This RCT involved 7th graders and their mothers from three large, geographically, socioeconomically, and academically diverse government-run high schools around Kingston, Jamaica (two single-sex, one co-educational). In Jamaica, after passing a national 6th grade exam, 7th grade is the entry point into high school where students establish independent dietary habits. Students can vary in age from 11 to 13 years. This contextual shift, along with major psychosocial, cognitive, and biological shifts around puberty, presents a window of opportunity for intervention. Figure 1 outlines the design and timeline of this five-month study.

Figure 1.

Study design and timeline for small-scale RCT of the JUS Media? Programme occurring over 5 months. Individual assessments at T1, T2, T3, and T4 included a questionnaire and two telephone-mediated 24-hour food recalls.

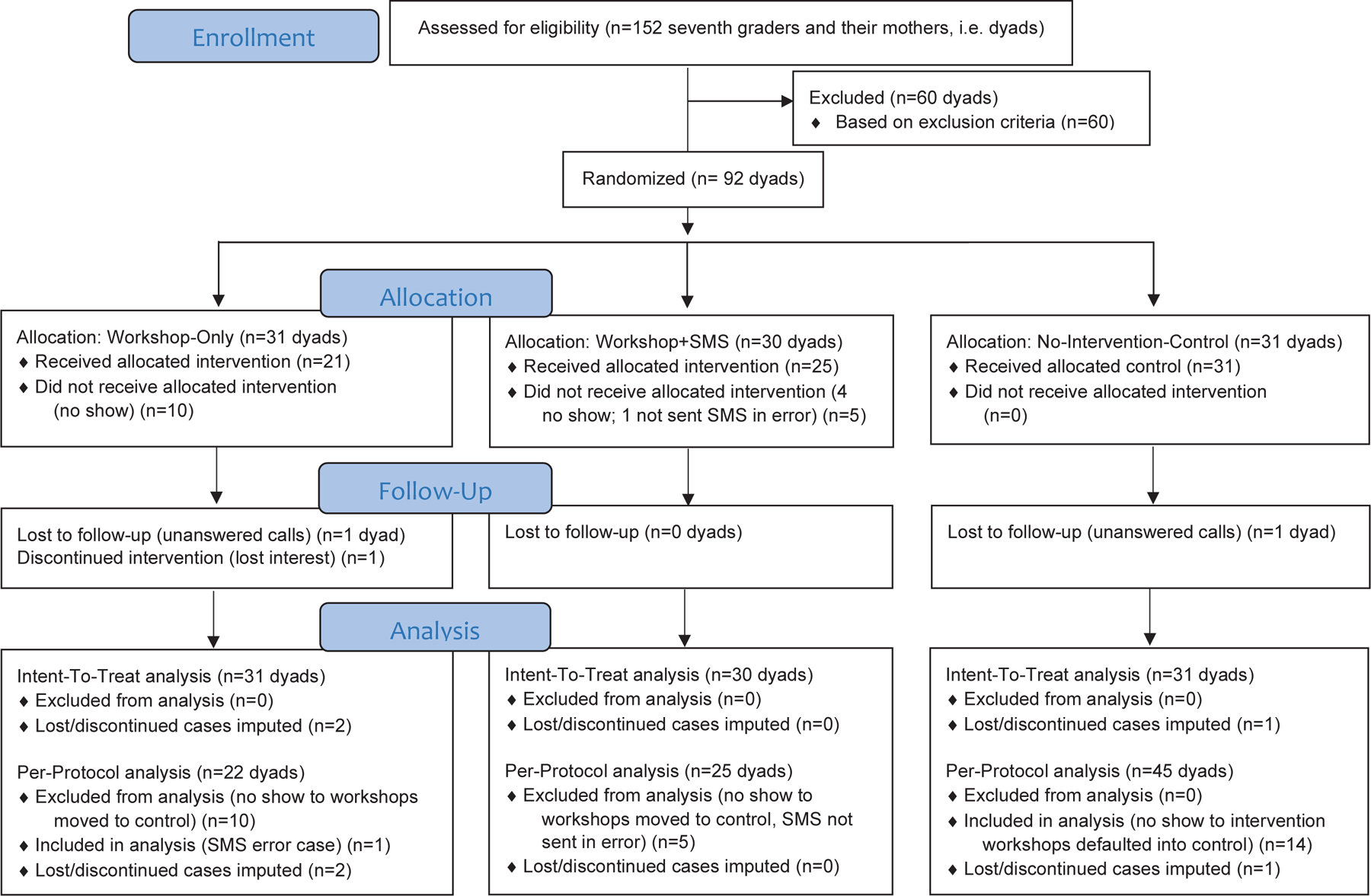

Following IRB approval from the U.S. institution (lead IRB# 17182) and collaborating Jamaican institution, approximately 800 7th-graders and their mothers were invited to be screened for eligibility. All 7th graders in attendance on screening days were given an envelope containing a parental consent form, adolescent assent form, and two 1-page screeners (student, mother). Altogether, 152 families opted into the study by returning all forms, consenting to group assignment to one of two intervention groups or no intervention (Appendix A). Dyads were excluded if: 1) mother/student had a mean score < 2 and any of the three screening measures indicating “none or none at all” for U.S. media enjoyment, “1 hr or less per day” watching U.S. TV, and “none”/“one time every week” consuming fast food/sugary drinks; 2) mother/student was not born in Jamaica, 3) mother/student was not a Jamaican citizen, 4) mother/student was a U.S. citizen/dual citizen, 5) had not lived in Jamaica for the past 15 years (mother) or 8 years (student), 6) mother/student did not live together, and 7) mother had been primary guardian for <5 years. Based on these criteria, 92 of those 152 screened dyads were selected for enrollment (Madolescent.age=12.79, SD=0.49, Mmother.age=39.08, SD=6.06; 51% girls). See Appendix C for more participant characteristics.

Single-blinded gender-stratified randomization of the 92 dyads was then performed by the U.S.-based principal investigator, who was not involved in recruitment/screening in Jamaica, by creating a randomization sequence using Excel 2016 with a 1:1:1 allocation. Dyads were placed into one of three ‘intent-to-treat’ conditions: Workshops-Only (31 dyads), Workshops+SMS (30 dyads), and No-Intervention-Control (31 dyads). The actual ‘per-protocol’ condition enrollments were: Workshops-Only (23 dyads), Workshops+SMS (26 dyads), and No-Intervention-Control (45 dyads) (per protocol groups were based on intervention/control condition actually received; see Appendix A for explanation including intervention no-shows).

Six months after T4 (final data collection point) for the RCT, a subsample of families who received the intervention participated in three post-intervention feedback focus groups (n = 16 individuals; ndyads=3, 2, 3 respectively). Only Workshops+SMS families were invited to participate in focus groups because they had experienced both the Workshops and SMS/texting components of the intervention (except for one Workshops-only family who was inadvertently added to the list of potentials making 26 eligible dyads total). Focus group interviews are ideal to gather in-depth feedback on participants’ program experiences 25) and can provide another index of the intervention effects. See Appendix D for more details.

Procedures

Adolescent-mother dyads in the Workshops-Only and Workshops+SMS conditions were pooled for workshops that covered: 1) national guidelines for a healthy balanced diet from the Jamaica Ministry of Health and Wellness (JMHW); 2) RA in Jamaica; 3) media literacy principles pertinent to food advertising such as how to critically analyze authors, audiences, messages/meanings, and representations/reality of ads (26); and 4) “subvertising” (subvert + advertising: 27), creating a parody of an existing ad. Each adolescent-mother dyad created a subvertisement over the next week and returned to Workshop #2 for a competition wherein participants voted for the best subvertisements. Winning families received certificates and small gifts. Dyads in the Workshops+SMS condition then received thirty 160-character SMS messages across 8 weeks reinforcing workshop content (responses not required). Fifteen of these messages paralleled workshop content to teach/remind the participant of a principle, then prompt towards a behavior. Interspersed were 15 companion messages delivering social feedback on responses to the prior content-driven SMS, which contained normative information (28). Six month after the intervention, a subsample of dyads assented to participate in feedback focus groups.

Each participating adolescent and mother received pre-paid phone credit as incentives (approximately US$1 for screener, US$7 for each workshop and focus group) and several families received a small travel stipend to attend workshops.

Measurement

This intervention aimed to improve nutrition and food-focused media literacy – the primary and secondary outcomes, respectively. Intervention effects were measured multidimensionally at T1-T4 and using post-intervention focus groups (described below). Nutrition was measured by food group knowledge, attitudes (stage of change towards nutrition goal), and behavior (foods eaten in the last 24 hours). First, knowledge of the JMHW national “Food Plate” dietary guidelines of Jamaica was measured (29). Participants were asked to assign each of 6 food groups to the correct proportion within a blank food plate: responses were scored “1” (correct) or “0” (incorrect) and a sum score was calculated (range=0–6). Second, a stages of change measure of healthy eating (30) was adapted to measure adherence to five JMHW food-based dietary guidelines (e.g., reducing sugary foods and eating a variety of food groups: 29). Participants used a 6-point scale including 1:precontemplation, 2:contemplation, 3:preparation; 4:action, and 5:maintenance stages (30). For items discouraging eating certain foods, there was a 6th option for total abstinence. Third, using structured telephone interviews with open-ended responses, 24-hour food recalls were conducted for one weekday and one weekend day at T1-T4 using a modified brief multiple pass method. The 24-hour recall is the most widely used dietary intake measure and has proven valid and reliable in Jamaica (31). Participant responses were recorded by trained interviewers and coded for the presence (1) or absence (0) of fruits, raw vegetables, cooked vegetables, fats/oils, and sugary foods/beverages.

For the secondary outcome, food-focused media literacy was measured with a 14-item 4-point disagree-agree scale that assesses meanings of advertising, representation, and truth (24). This measure was previously validated in Jamaica (3) and the scale mean was used (αadolescent =.75-.89, αmother=.83-.92).

For focus groups, three interviewers (Jamaican, Jamaican American, American) posed interview questions with clarifying probes. Questions covered: 1) participants’ general experiences in the JUS Media? Programme and its perceived impact on their nutrition and their lives; 2) perceived strengths and weaknesses of the intervention; and 3) SMS effectiveness. See Appendix D for more details.

Data Analyses

Persistent attempts (calls/texts) were made to follow and retain all participants across the study (32). The amount of missing data for youth at T1 was 24%, 30% at T2 and T3, and 16% at T4. For mothers, there was 20% missing data at T1, 32% at T2, 31% at T3, and 16% at T4. Little’s MCAR test was conducted for youth and mother data at each time point, confirming by non-significance that these values were missing at random. For youth, results at T1-T4 were, respectively: χ2(2,925)=148.32, χ2(3,099)=34.35, χ2(2,607)=1731.64, and χ2(2,911)= 310.12, all ps>.05. Mothers’ values were similar: χ2(2,463)=1729.56, χ2(3,869)=1481.54, χ2(3,657)=2223.56, and χ2(3,298)=139.44, all ps>.05. Therefore, multiple imputation specifying five imputations was done, and imputed values were aggregated across the five new datasets before data analyses. Three dyads were lost to follow-up (see Appendix A) and those missing values were imputed as described. Based on RCT recommendations (33, 34), per-protocol (PP) analyses were performed in addition to intent-to-treat (ITT) to most accurately estimate the actual difference between conditions, which can be underestimated by ITT analyses. PP analyses showed very similar results to intent-to-treat analyses (ITT); therefore, ITT analyses are reported in the text whereas ITT and PP results are displayed in Table 1. In one case (24-hour Food Recall), both ITT and PP analyses are reported in the text because only the PP MANCOVA reached the threshold for statistical significance; however, the ITT and PP means comparisons and effect sizes are virtually identical (see Table 1). Sensitivity analyses showed identical results with an alternate dataset (32; see Appendix C). An alpha level of .05 was used although ‘marginal significance’ (<.10) is also noted.

Table 1.

Statistically significant mean comparisons from ANCOVAs comparing RCT conditions across study outcomes

| Outcome | Scale range | Time point | Participant | Contrasted conditions | Intent-to-treat analyses |

Per-protocol analyses |

Figure | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean difference | 95% CI | Cohen’s d | Mean difference | 95% CI | Cohen’s d | ||||||

| Nutrition knowledge (food groups) | 0–6 | T3 | Adolescents | W + S > C | 1.08* | .20–1.95 | .630 | .88* | .01–1.77 | .458 | 2 |

| T4 | Mothers | W +S > C | .79* | .12–1.71 | .608 | .84+ | −.08, 1.76 | .510 | 2 | ||

| Mothers | W > C | 1.07+ | .14–1.99 | .438 | .96* | .02–1.91 | .552 | 2 | |||

| Stage of change toward healthier eating (fruits) | 1–5 | T3 | Adolescents | Pooled W > C | .41* | .04–.77 | .493 | .34+ | −.02, .70 | .417 | 2 |

| T3 | Mothers | Pooled W > C | .36* | .02–.75 | .431 | .44* | .07–.81 | .452 | 2 | ||

| 24-Hour recall of cooked vegetables | 0–1 | T2 | Mothers | W > C | .26* | .05, .47 | .607 | .21+ | .01–.43 | .470 | 3 |

| T2 | Mothers | W + S > C | .22* | .01–.43 | .601 | .23* | .02–.45 | .519 | 3 | ||

| T4 | Adolescents | W > C | .25* | .01–.50 | .528 | .27* | .02–.52 | .477 | 3 | ||

| T4 | Adolescents | W + S > C | .22+ | −.03–.48 | .429 | .30* | .05–.55 | .500 | 3 | ||

| T4 | Mothers | W > C | .20+ | −.03–.43 | .406 | .25* | .04–.50 | .581 | 3 | ||

| T4 | Mothers | W + S > C | .24* | .06–.47 | .548 | .26* | .02–.48 | .642 | 3 | ||

| Food-focused media literacy | 1–4 | T2 | Adolescents | W > C | .24* | .03–.44 | .580 | .24* | .03–.45 | .610 | 3 |

| T2 | Adolescents | W + S > C | .18+ | .38–.38 | .439 | .18+ | −.03, .38 | .410 | 3 | ||

| T3 | Mothers | W > C | .11* | .01–.44 | .536 | .19+ | −.04, .41 | .528 | 3 | ||

| T3 | Mothers | W + S > C | .11* | .04–.48 | .620 | .25* | .03–.47 | .721 | 3 | ||

| T4 | Mothers | W + S > W | .34* | .06–.62 | .625 | .25+ | −.03, .53 | .468 | 3 | ||

| T4 | Mothers | W + S > C | .26* | .02–.54 | .600 | .39** | .11–.67 | .800 | 3 | ||

Note. Table displays statistically significant mean comparisons to correspond to the Results section text; see text for M/ANCOVA F-test statistics. Mean comparisons displayed here controlled for SES (household possessions).

ANCOVA = analysis of covariance; C = Control; CI = confidence interval; MANCOVA = multivariate analysis of covariance; Pooled W = Pooled Workshops; RCT = randomized controlled trial; W = Workshop; W + S = Workshop + SMS.

p < .01

p < .05

p < .10.

Using SPSS 25 for quantitative data, mixed repeated-measures MANCOVAs and ANCOVAs were conducted with two within-subject factors (Time X 4, Person X 2) and one between-subjects factor (Condition X 3) controlling for SES (Household possessions) to examine the intervention effects on nutrition and media literacy. Whenever the sphericity assumption was violated, the Greenhouse-Geisser test was used (35). A priori power calculations based on mean changes in media/advertising literacy from previous research (23) confirmed that the sample size would provide adequate to robust statistical power (≥ .80) to detect small effects for the central Time X Condition interaction. Within-group change over time was not the focus of these analyses because of expected placebo effects across conditions; rather, group differences in change over time were the focus. Thematic analyses (36) were used to analyze the focus group data and coding was performed by two project staff present in the focus groups.

Results

Appendix B displays the T1 means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations among major study variables. Generally, at T1 both adolescents and mothers had moderate nutrition and media literacy scores. SES was significantly correlated with adolescents’ fruit consumption (r= −.22, p < .05) and mothers’ nutrition knowledge (r=.22, p<.05) at T1. Therefore, SES was covaried in the main analyses. There were no significant group differences at T1, except in one instance where the Workshop group had lower cooked vegetable consumption than control (pattern reversed by T4). Table 1 displays mean comparisons across conditions for all outcomes analyzed.

Nutrition Knowledge: Food Groups

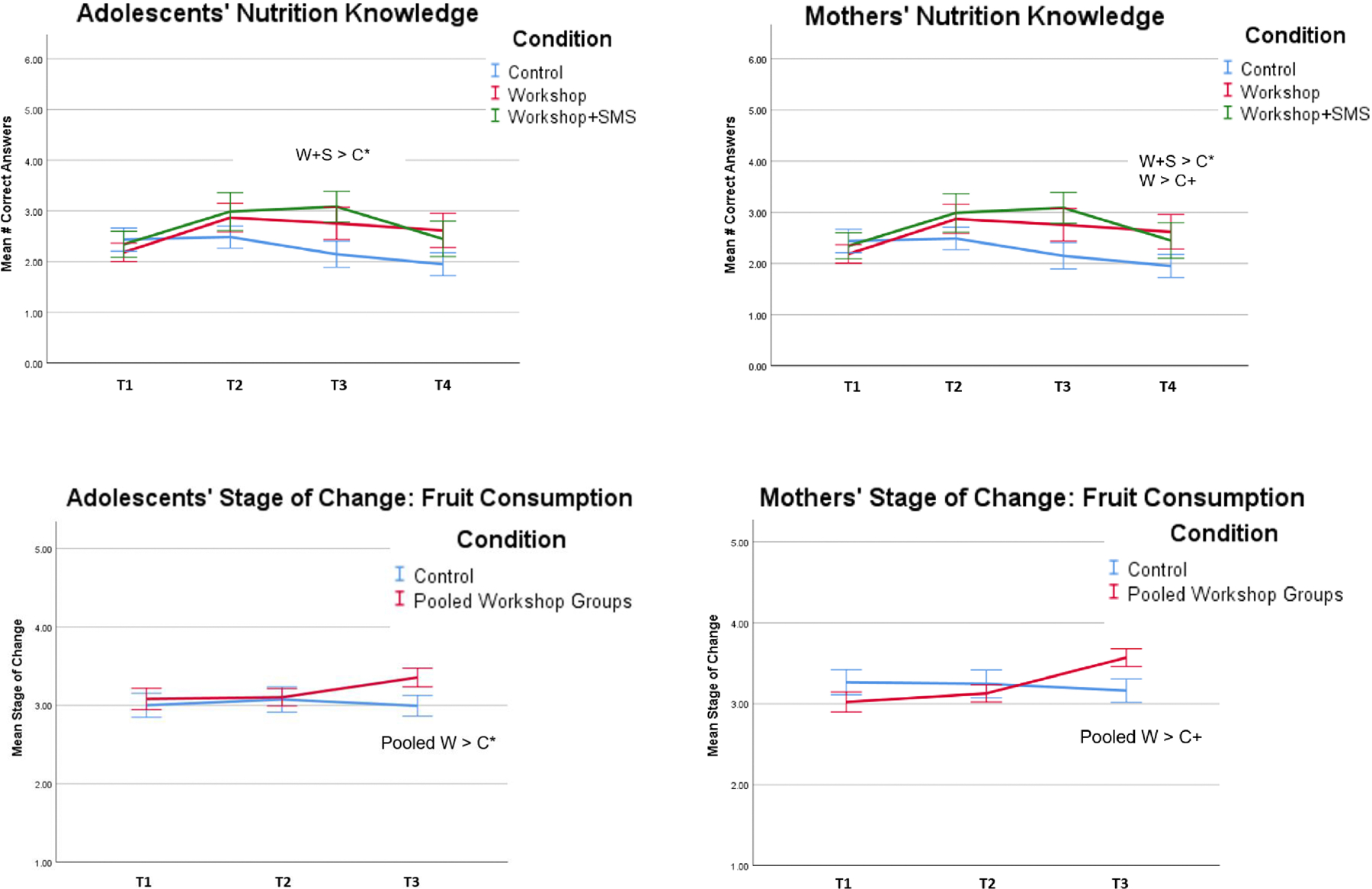

There were no significant main effects of Condition on Nutrition Knowledge in the ANCOVA but, as hypothesized, there was a significant Time X Condition interaction, F(6,264)=2.432, p=.026, ηp2=.052, further qualified by a marginally significant Time X Condition X Person interaction, F(6,264)=1.964, p=.071, ηp2=.043. Follow-up ANCOVAs revealed mean differences across conditions at T3 for adolescents, F(2,88)=2.998, p=.055, ηp2=.064, and at T4 for mothers, F(2,88)=2.879, p=.061, ηp2=.061. Per means comparisons, adolescents in the Workshops+SMS group had significantly higher Nutrition Knowledge at T3 compared to those in the Control group and mothers in the Workshops+SMS group and Workshops-only group had higher Nutrition Knowledge than those in the Control group at T4 (Table 1, Figure 2 top).

Figure 2.

Changes in Adolescents’ and Mothers’ Nutrition Knowledge (top) and Stage of Change in Fruit Consumption (bottom) by Condition. W = Workshop, Pooled W = Pooled Workshops, W+S = Workshop+SMS, C = Control. *p < .05 +p < .10

Nutrition Attitudes: Stage of Change Towards Healthy Eating

Initial MANCOVA results showed no significant main effects or interactions of Condition on participants’ Stage of Change Towards Healthy Eating. However, to further investigate the a priori hypotheses, the two intervention conditions were pooled to increase analytic power given that both intervention conditions had identical experiences from T1-T3 (i.e., pooled workshops). Therefore, the MANCOVA was rerun with T1-T3 data only. As expected, the multivariate effects and univariate analyses showed no significant main effects, but there was a significant Time X Condition interaction for Fruit Consumption, F(2,178)=4.600, p=.011, ηp2=.049. Follow-up ANCOVAs for adolescents revealed significant differences across conditions at T3, F(1,89)=4.796, p=.031, ηp2=.05: relative to those in the Control group, adolescents in the pooled Workshops condition were further along in the preparation stage and closer to the action stage of change towards recommended daily fruit consumption. There was a similar finding for mothers, albeit a marginal effect, F(1,89)=3.563, p=.062, ηp2=.038 (Table 1, Figure 2 bottom).

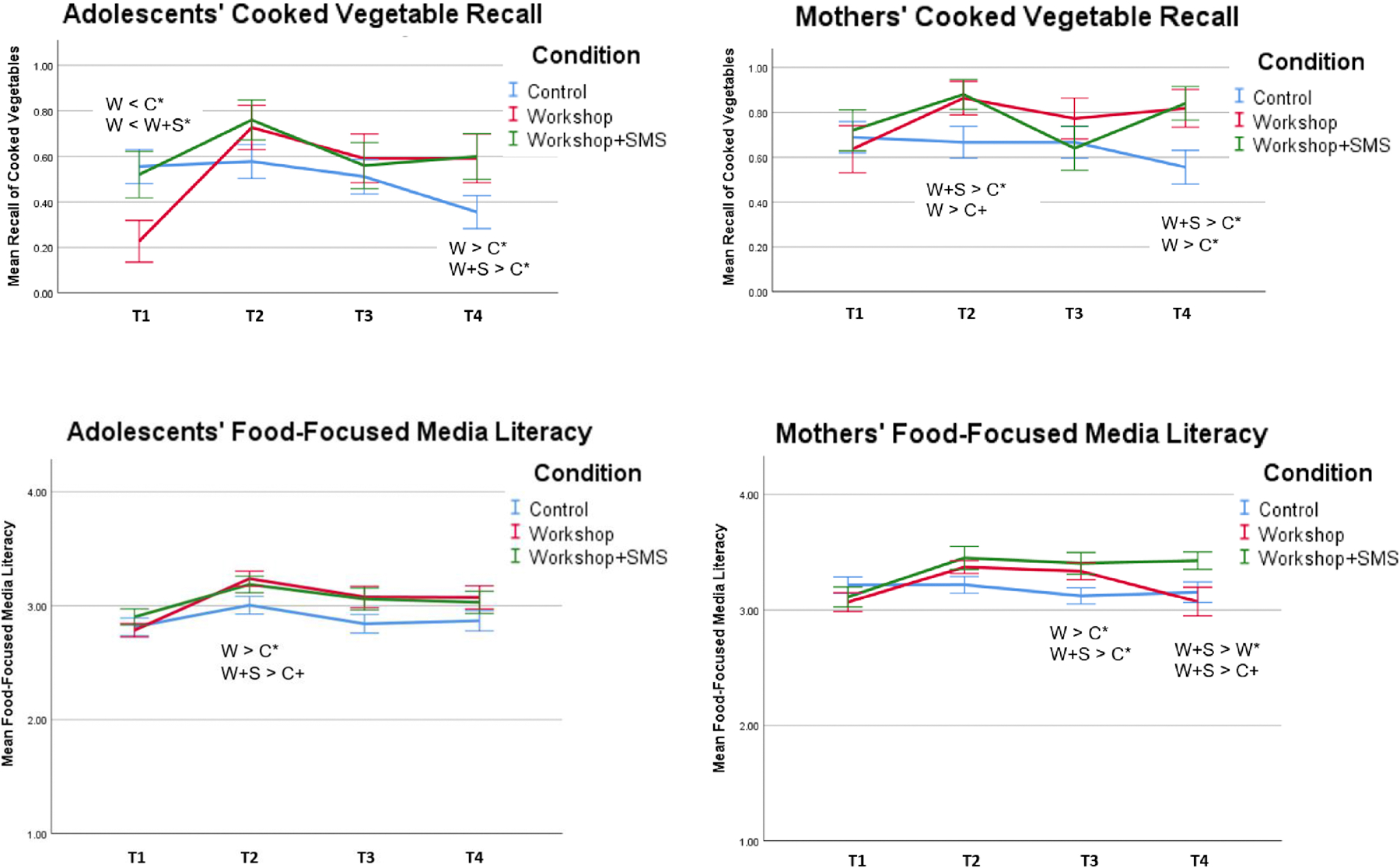

Nutrition Behavior: 24-Hour Recall

There were no significant main effects or interactions on 24-hour Food Recall in ITT MANCOVA analyses: Wilks Lambda=.652, F(30,148)=1.176, p=.260, ηp2=.193 for the central Time X Condition interaction. However, PP analyses showed no significant main effects but, as hypothesized, there was a significant multivariate Time X Condition interaction, Wilks Lambda=.572, F(30,148)=1.588, p=.038, ηp2=.244. Univariate analyses showed this 2-way interaction was significant for Cooked Vegetable recall, F(5,244)=3.478, p=.003, ηp2=.073. First, follow-up ANCOVAs for adolescents at T1 revealed a main effect that Workshop adolescents ate fewer cooked vegetables than did those in other conditions (F(2,88) = 3.391, p=.038, ηp2.072, see Table 1). However, this pattern reversed by T4 (F(2,88)=3.700, p=.029, ηp2=.078: Figure 3a): adolescents in the Workshops+SMS and Workshops-only groups ate more cooked vegetables than those in the Control group. Practically, only one in three control group adolescents recalled eating cooked vegetables at T4 compared to nearly two in three intervention adolescents. Mothers’ ANCOVA findings were identical at T2 (F(2,88)=3.139, p=.048, ηp2=.067) and T4 (F(2,88)=3.582, p=.032, ηp2=.075: Table 1, Figure 3 top). Only 55% of control mothers recalled eating cooked vegetables at T4 compared with over 80% of intervention mothers. There were also significant main effects of person on adolescents’ Sugary Foods and Beverages in the multivariate and univariate analyses, Wilks Lambda=.890, F(5,84)=2.076, p=.076, ηp2=.110, F(1,88)=5.094, p=.026, ηp2=.055, whereby adolescents consumed more sugary foods and drinks overall compared to their mothers.

Figure 3.

Changes in Adolescents’ and Mothers’ Recall of Cooked Vegetables Consumed in the Last 24 Hours (top) and Food-Focused Media Literacy (bottom) by Condition. W = Workshop, W+S = Workshop+SMS, C = Control. *p < .05 +p < .10

Food-Focused Media Literacy

There were no significant ANCOVA main effects on Food-Focused Media Literacy, but as hypothesized, there was a significant Time X Condition interaction (F(4.812, 211.734)=3.616, p=.004, ηp2=.076). Follow-up ANCOVAs revealed differences across conditions at T2 for adolescents, F(2,88)=2.889, p=.061, ηp2=.062, and differences at T3 and T4 for mothers, F(2,88)=3.339, p=.040, ηp2=.071) and F(2,88)=3.101, p=.050, ηp2=.066, respectively. Specifically, adolescents in the Workshops-only and the Workshops+SMS groups had higher media literacy at T2 than those in the Control group and mothers showed near identical effects at T3 with higher scores in the Workshops-only and Workshops+SMS groups relative to the Control group. At T4 Workshops+SMS mothers had higher media literacy scores than Workshops-only and Control mothers (Table 1, Figure 3 bottom).

Focus Groups

Thematic analyses revealed six themes regarding perceived impacts of the intervention: increased healthy eating, decreased unhealthy eating, balanced diet, catalyzed parent-adolescent communication, indirect impacts on others, and improved physical health and fitness. Additionally, there were three themes regarding perceived behavior change: process of change, facilitators of change, and barriers to change. See Table 2 for these themes, codes, and illustrative quotes.

Table 2.

Themes and codes from post-intervention feedback focus groups discussing the JUS Media? Programme

| Themes | Codes | Illustrative quotesa | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Impact of intervention | Increased healthy eating | Eat more fruits and vegetables |

|

| Drink more water | |||

| Buy healthier lunches | |||

| Decreased unhealthy eating | Consume less sugar-sweetened beverage |

|

|

| Reduce unhealthy lunch purchases |

|

||

| Eat less junk food |

|

||

| Balanced diet | Eat multiple food groups |

|

|

| Use moderation |

|

||

| Catalyzed parent-adolescent communication | Discuss healthy eating |

|

|

| Discuss unhealthy eating |

|

||

| Discuss media literacy |

|

||

| Discuss shared activities |

|

||

| Indirect impacts on others | Tell others |

|

|

| Others observe my change |

|

||

| Encourage others to eat healthily |

|

||

| Less acid reflux |

|

||

| More energy and stamina |

|

||

| Improved physical health and fitness | Better athletic performance |

|

|

| Behavior change | Process of change | Heightened awareness |

|

| Critical thinking |

|

||

| Recollections and reflections |

|

||

| Parental reinforcement |

|

||

| Rapid/major change |

|

||

| Gradual/partial change |

|

||

| Facilitators of change | Food plate chart |

|

|

| Medical condition |

|

||

| Accessibility of healthy food options |

|

||

| Awareness of health risks of junk food |

|

||

| Program dare/challenge |

|

||

| Barriers to change | Bad habits |

|

|

| Lack of healthy food options |

|

||

| Practical constraints |

|

Each participant’s illustrative quote is preceded by a dyad ID containing a “Y” or “M” to indicate whether it was the Youth or Mother speaking, respectively.

Beyond these themes, focus groups also revealed that participants found the workshop enjoyable (i.e., “nice”, “fun”, “interesting”, “helpful”) and they were fond of the visuals (e.g., Food Plate, video clips of ads) and the subvertising component (e.g., ad spoofing, contest). Participants also felt proud of their accomplishments and the future preventive value of their learning (e.g., 217M “Saves you money from going to the doctor because when you get obese and everything”). Finally, focus group feedback suggested that the SMS supplement was of appropriate length (i.e., 8 weeks) and that several factors facilitated SMS responsiveness including use of local dialect and appropriate frequency and timing of SMS, and a consistent morning send-time for SMS, and barriers were also reported including technical issues and human error.

Discussion

Remote acculturation (RA) to U.S. culture has only recently been recognized as a psychocultural determinant of health (2). RA puts some global youth and parents at higher health risk because their strong affinity for U.S. media exposes them to more junk food advertising, which is associated with eating less healthy foods (2). Teaching food-focused media literacy skills is an underexploited strategy to support healthy eating choices globally in the face of pervasive junk food advertising especially in U.S. media (3,4). The current study evaluated the efficacy of the JUS Media? Programme – a transdisciplinary food-focused media literacy intervention designed for remotely acculturating families – among adolescents and mothers in Jamaica using a small-scale RCT. Findings showed support for the efficacy of this brief intervention with small to medium effects (ηp2=.03-.07; d=.43-.63) with extended gains via SMS follow-up. Relative to control, families in one or both intervention groups – Workshops-only and Workshops+SMS – were eating significantly more cooked vegetables after the intervention (nearly twice as many intervention participants vs. control were eating cooked vegetables at study endpoint), were at a more advanced stage of change regarding increasing daily fruit consumption, demonstrated greater nutrition knowledge, and showed better critical thinking about food advertising.

These findings indicate the health promoting effect of JUS Media? – the intervention was efficacious in increasing vegetable and fruit consumption plans and actions but not in reducing dietary sugar or fat in our analyses. However, in post-intervention focus groups, participants did report reducing both sugar and fat along with several other positive changes (e.g., swapping water for soda, less fried food – see Table 2). This quantitative/qualitative discrepancy is likely because the 24-hr recall measurement focused on food presence/absence versus quantity (i.e., sugar/fat are ingredients in many more foods than fruits). The loss of sensitivity was a necessary methodological compromise in favor of the higher feasibility of phone versus in-person assessment, and higher validity of 24-hours recall over other tools.

Post-intervention focus groups clearly demonstrated that the statistical significance translated into large practical significance (see Table 2). Major positive impacts of JUS Media? on participants’ daily lives included healthier food choices at home and at school, developing a habit of critical thinking about food and advertising, improved medical conditions, enhanced physical fitness and performance, and even better parent-adolescent communication. Not only did both adolescents and mothers show positive changes in nutrition and food-focused media literacy post-intervention, but they also reported positive changes in their parent-adolescent communication and bonding in focus groups. Therefore, according to Masten’s (2015) categorization of resilience-promoting interventions (37), the JUS Media? Programme had dual effects: boosting media literacy as a protective resource for adolescents and mothers as individuals, and bolstering the parent-adolescent relationship to mobilize the power of this adaptive system in the face of globalization-related stressors. Socially desirable responding does not account for these remarkable positive impacts reported because participants were also candid in voicing their initial skepticism and giving constructive feedback about the intervention.

Several aspects of the JUS Media? Programme likely contributed to its efficacy. First, targeting early adolescents enabled the intervention to capitalize on this window of opportunity during rapid development, and the program was tailored to adolescents’ developmental characteristics including increased autonomy-seeking and the rise in abstract and critical thinking abilities (4). The intervention was well-timed at the transition into high school (7th grade) when adolescents are establishing new dietary habits that will serve them for several years. The inclusion of mothers likely also contributed to intervention efficacy because mothers are major drivers of nutrition in the home and they continue to matter for positive adolescent development and well-being (4). Finally, the cultural and contextual tailoring of the intervention to Jamaican families contributed to its acceptability and efficacy as did the societal timing given the current national/regional efforts to address obesity (22).

We acknowledge some study limitations. First, although all 7th graders at the diverse schools participating were invited, participants self-selected into the study. However, randomization ensured that the intervention effects were not due to higher motivation of the treatment groups. The 24-hour recall MANCOVA findings were only statistically significant in PP analyses although both ITT and PP means comparisons found statistically significant post-intervention differences between the control group and both intervention groups for adolescents and their mothers. A modest sample size was planned to adequately power the detection of small effects in a priori efficacy analyses, but the study would have been underpowered to conclusively test mechanisms including media literacy as a mediator of intervention effects. Future studies can assess longer-term maintenance of gains, the degree to which JUS Media? may motivate better alignment between one’s food choices and one’s values (e.g., adolescent autonomy: 38), and decrease attentional biases to junk food (39).

Conclusion

To our knowledge, this study is the first RCT to demonstrate that brief food-focused media literacy training can improve adolescent and family nutrition in a low/middle-income country, and that remote acculturation can be used to better target health interventions. Study results can guide the Jamaican government and supranational organizations (e.g., World Bank) in designing and implementing cost-/ time-effective policies in culturally and contextually appropriate ways (3). With minor cultural adaptations the JUS Media? Programme may be extended to Jamaican immigrant families in the United States and elsewhere, as well as in other acculturating groups. This approach can be applied to food marketing from any cultural source, not only U.S.-produced and can be easily extended to other unwanted foreign media messages impacting adolescent health habits such as smoking (40).

Implications and Contribution.

This brief cost-effective transdisciplinary intervention, the JUS Media? Programme, promotes healthier eating among remotely acculturating adolescents and mothers internationally by teaching critical thinking skills about food advertising on U.S. cable television. This study demonstrates the efficacy of media literacy training to promote adolescent nutrition in a low/middle income country.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the National Institutes of Health, Fogarty International Center (#R21TW010440) and the trial is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04492592). We thank the staff and families at the participating schools for their partnership, McKenzie Martin and Euette Mundy-Parkes for assistance with data collection, and Lauren Eales and Cara Lucke for assistance with manuscript preparation. This transdisciplinary research was presented at the conferences of the Society for Research on Adolescence, the Society for Public Health Education, the Jamaican National Health Research Conference, the International Society for the Study of Behavioral Development, the International Association of Cross-Cultural Psychology, the National Association for Media Literacy Education Conference, and the American Academy of Advertising. We have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Appendix A. CONSORT Flow Diagram of RCT method (n=dyads, not individuals)

Appendix B: Inter-correlations among T1 study variables for adolescents (above diagonal) and mothers (below diagonal)

| Measure | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. | M youth | SDyouth |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Household Possessions | 0.65 ** | 0.09 | −0.22* | −0.14 | −0.12 | −0.11 | 0.06 | −0.15 | 0.00 | −0.06 | N/A | 0.01 | 14.00 | 5.12 |

| 2. Nutrition Knowledge | 0.00 | 0.26 * | 0.18 | 0.32** | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.21* | −0.11 | N/A | −0.09 | 2.32 | 1.33 |

| 3. Stage of Change_Fruits | −0.04 | −0.16 | 0.08 | 0.46** | 0.34** | 0.22* | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.19 | −0.09 | N/A | −0.03 | 3.10 | 0.93 |

| 4. Stage of Change_Vegetables | −0.03 | −0.19 | 0.47** | 0.26 * | 0.29** | 0.14 | 0.03 | 0.19 | 0.11 | −0.18 | N/A | −0.08 | 2.41 | 1.10 |

| 5. Stage of Change_Sugar | 0.23* | 0.08 | −0.19 | 0.09 | 0.00 | 0.49** | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.11 | −0.06 | N/A | 0.11 | 3.29 | 1.07 |

| 6. Stage of Change_Fats/Oils | 0.04 | −0.24* | 0.18 | 0.38** | 0.29** | 0.06 | 0.16 | 0.08 | 0.17 | −0.25* | N/A | −0.01 | 3.20 | 1.03 |

| 7. Food Recall_Fruits | −0.02 | 0.00 | 0.13 | 0.17 | −0.03 | 0.13 | 0.06 | 0.28** | 0.09 | −0.02 | N/A | −0.22* | 0.49 | 0.50 |

| 8. Food Recall_Raw Vegetables | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.13 | 0.05 | −0.10 | −0.06 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.07 | −0.11 | N/A | −0.26* | 0.52 | 0.50 |

| 9. Food Recall_Cooked Vegetables | 0.09 | 0.02 | −0.20 | −0.09 | 0.08 | −0.02 | 0.08 | −0.05 | 0.07 | −0.02 | N/A | 0.07 | 0.47 | 0.50 |

| 10. Food Recall_Sugary Items | 0.05 | −0.18 | −0.08 | −0.01 | −0.07 | −0.01 | −0.06 | −0.06 | 0.00 | 0.20 | N/A | 0.14 | 4.79 | 2.18 |

| 11. Food Recall_Fats/Oils | 0.17 | 0.00 | −0.03 | −0.05 | 0.10 | −0.07 | −0.05 | −0.09 | 0.04 | 0.07 | N/A | N/A | 1.00 | 0.00 |

| 12. Food-Focused Media Literacy | 0.05 | −0.08 | −0.05 | −0.06 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.18 | −0.04 | −0.10 | 0.03 | −0.13 | 0.34 ** | 2.83 | 0.38 |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| M mother | 13.83 | 2.47 | 3.05 | 3.09 | 3.96 | 3.91 | 0.71 | 0.41 | 0.68 | 4.02 | 0.95 | 3.13 | ||

| SD mother | 4.06 | 1.30 | 0.99 | 1.07 | 1.09 | 0.88 | 0.46 | 0.50 | 0.47 | 2.17 | 0.23 | 0.44 | ||

Note.

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01.

Bolded cells represent correlations between mother and child variables.

“N/A” indicates that a correlation was not possible because “Food Recall_Fats/Oils” for children lacked variation (i.e., present for all adolescents).

Appendix C. Additional Methods

Participant Characteristics

All but two participating women (stepmother, older sister) were biological mothers of the adolescents and virtually all participants identified as Black or being ‘mixed’ with Black (adolescents: 87% & 10%; mothers: 88% & 8%, respectively). Per adolescent report, the modal household size was four including the adolescent-mother dyad, with fathers living in 32% of households, siblings in 37%, and grandparents in 20%. Household principal earner education on a 1–7 ordinal scale ranged from 2 (“7th, 8th, or 9th grade”, 8%) to 7 (“graduate professional degree (e.g., MS, MD, PhD)”, 17%) with a mode of 5 (“technical/vocation program or started university”, 30%) (adapted from 1). A common instrument in this cultural context captured socioeconomic status: on a list of 20 household possessions wherein one extra point was added for each additional phone or vehicle beyond one, the sample range was 2 – 25 with a mean of 13.94 (SD=4.01; adapted from 2).

Sensitivity Analyses for the Randomized Controlled Trial

Sensitivity analyses were performed by preparing an alternative dataset in which missing data points were replaced using the ‘last observation carried forward’ method (1), using an assumption of no change in an outcome whenever it was not reported (e.g., T3 score carried forward to T4 if T4 missing). Analyses testing a priori hypotheses showed identical results using this alternative dataset, boosting confidence in the findings.

References

- 1.Hollingshead AA (1975). The four-factor index of social status. New Haven: Department of Sociology, Yale University; (Unpublished manuscript). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilks R, Younger N, McFarlane S, Francis D, Van DenBroeck J Jamaican youth risk and resiliency behaviour survey 2006: Community-based survey on risk and resiliency behaviours of 15–19 year olds. 2007. Retrieved from: http://www.cpc.unc.edu/measure/publications/tr-07-64

Appendix D. JUS Media? Post-Intervention Focus Groups

Post-intervention focus groups provided another index of the intervention effects by capturing the felt impact of the JUS Media? Programme on adolescents’ and mothers’ daily lives in their own words to complement statistical analysis findings. Below is an outline of the methods, results, and discussion of those focus groups.

Methods

Participants and Procedure

Six months after T4 (final data collection point) for the JUS Media? Programme RCT, a subsample of families who received the intervention participated in three post-intervention feedback focus groups (n = 16 individuals; ndyads=3, 2, 3 respectively). Focus group interviews are ideal to gather in-depth feedback on participants’ program experiences. Relative to individual interviews or surveys, focus groups can foster an exchange of opinions among participants who experienced the same program and elicit richer and more representative reflections. Focus groups also uniquely empower participants, especially adolescents, to share their views in spontaneous and authentic ways, rather than requiring every participant to answer every question (2).

Only Workshops+SMS families were considered for invitations to participate in focus groups because they had experienced both the Workshops and SMS/texting components of the JUS Media? Programme (except for one Workshops-only family who was inadvertently added to the list of potentials making 26 eligible dyads total). The first set of focus group invitations was sent to an even distribution of more responsive and less responsive participants based on their engagement with the SMS phase of the intervention, which was the final component of the RCT preceding the focus groups. Additional dyads were invited if those initial invitees declined or failed to respond until a total of 20 invitations were sent. Mothers and adolescents in each dyad individually assented to participate: 11 dyads enrolled and eight of these eventually attended. Independent samples t-tests confirmed that the focus group subsample was representative of the larger sample in that they did not differ in SES (household principal earner education, possessions) nor in T1 or T4 major study variables, except that they reported exerting less effort than the larger sample to increase fruit consumption at T4, t(90) = 3.14, p = .03. The direction of this difference makes it less likely for these participants to report meaningful intervention effects relative to the rest of the RCT study sample; therefore, focus group participant feedback might underestimate intervention-related gains.

Three interviewers, who were arranged around a table amongst participants, posed interview questions with clarifying probes. There were three clusters of focus group questions: 1) Participants’ general experiences in the JUS Media? Programme (e.g., “We would like to hear a little bit about your experience participating in the JUS Media? Programme”); 2) Perceived strengths and weaknesses of the intervention (e.g., “Was there anything that was helpful or unhelpful about the JUS Media? Programme for you?” “Are there aspects of the Programme you would keep and aspects you would change”); and 3) SMS component effectiveness (e.g., “Did you like or dislike receiving text messages?” “What was your favorite [SMS] and why?”)

Data Analysis

Thematic analysis (3) was used to code and analyze the felt impact of the JUS Media? Programme in participants’ lives, as well as the process of their behavior change. Focus group interviews were coded by two project personnel of Jamaican descent. After transcription, coders read all transcripts entirely, then identified initial codes independently of each other. Next, coders met to discuss their codes/themes and to establish consensus between them including resolving any discrepancies. Finally, themes and their definitions were refined by coders and quotes were selected to represent each theme. Negative cases (i.e., differing opinions) were few, and were included in the process.

Results

Both positive and constructive feedback were explicitly sought from participants in feedback focus groups six months post-intervention. Content analysis revealed overwhelmingly positive experiences during the intervention, a variety of perceived positive impacts after the intervention, and key features of their behavior change process (see Table 2 for a detailed breakdown of themes, codes, and sample quotes). Overall, participants found the workshop enjoyable (i.e., “nice”, “fun”, “interesting”, “helpful”) and of appropriate length (i.e., 8 weeks). Adolescents and mothers reported fondness for the visuals (e.g., Food Plate, video clips of ads, stages of change visual) and for the subvertising component (e.g., singing, ad spoofing, contest). They also felt proud of their accomplishments and the future preventive value of their learning (e.g., 217M “Saves you money from going to the doctor because when you get obese and everything”).

As outlined in Table 2, there were six themes regarding perceived impacts of the intervention: increased healthy eating, decreased unhealthy eating, balanced diet, catalyzed parent-adolescent communication, indirect impacts on others, and improved physical health and fitness. Additionally, there were three themes regarding perceived behavior change: process of change, facilitators of change, and barriers to change. Participants (all in 7th grade, the lowest grade in Jamaican high schools) also suggested offering the intervention to higher grades and to other schools. Participants also shared suggestions for boosting SMS responsiveness in the future (e.g., Whatsapp: free/cheaper; staggered phone credit vs. lump sum).

Finally, focus group feedback suggested that several factors facilitated SMS responsiveness including the use of the local dialect (Jamaican Patois), appropriate frequency and timing of SMS blasts, and a consistent AM send-time for SMS that participants could integrate into their morning routine (e.g., 562M “The texts wake me every morning…because the phone is right at my head, so it just vibrates ‘mmmm’ and it’s time to get up.”). There were also some barriers reported including technical issues (e.g., lack of phone credit, failure to receive project SMS, phone crashes) and human error (e.g., did not read SMS, limited time to respond to SMS, forgetting to respond).

Conclusion

Post-intervention focus groups clearly demonstrated that the statistical significance found in the RCT translated into large practical significance (see Table 2 quotes). Participants – both those who were more engaged and others who were less so by the end of the intervention (SMS phase) – described major positive impacts of JUS Media? on their daily lives including healthier food choices at home and at school, developing a habit of critical thinking about food and advertising, improved medical conditions (e.g., acid reflux), enhanced physical fitness and performance (e.g., greater stamina in track and field), and even better parent-adolescent communication. Socially desirable responding does not account for the remarkable positive impacts reported because participants also candidly acknowledged their initial skepticism with the program (i.e. “Honestly at first I was’n, I wasn’t following the diet…”), owned their internal barriers to change (e.g., ‘I’m a person weh love junk food’), and noted external barriers that limited their change (e.g., availability and cost of healthy foods).

Not only did both adolescents and mothers show positive changes in nutrition and food-focused media literacy post-intervention, but they also reported positive changes in their parent-adolescent communication and bonding in focus groups. Therefore, according to Masten’s (2015) categorization of resilience-promoting interventions (4), the JUS Media? Programme had dual effects: boosting media literacy as a protective resource for adolescents and mothers as individuals, and bolstering the parent-adolescent relationship to mobilize the power of this adaptive system in the face of globalization-related stressors.

REFERENCES

- 1.White IR, Carpenter J, Horton NJ. Including all individuals is not enough: Lessons for intention-to-treat analysis. Clin Trials J Soc Clin Trials. 2012. August;9(4):396–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vaughn SR, Schumm JS, & Sinagub JM. Focus group interviews in education and psychology. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006. January;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Masten AS. Ordinary magic: Resilience in development. New York, NY: Guildford Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ferguson GM, Bornstein MH. Remote acculturation of early adolescents in Jamaica towards European American culture: A replication and extension. Int J Intercult Relat 2015. March;45:24–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferguson GM, Muzaffar H, Iturbide MI, Chu H, Meeks Gardner J. Feel American, Watch American, Eat American? Remote Acculturation, TV, and Nutrition Among Adolescent-Mother Dyads in Jamaica. Child Dev 2018. July;89(4):1360–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferguson GM, Nelson MR, Fiese BH, Meeks Gardner J, Koester B, The JUS Media Team. U.S. media enjoyment without strong media literacy undermines efforts to reduce adolescents’ and mothers’ reported unhealthy eating in Jamaica. J Res Adolesc [Internet]. Early online publication 10.1111/jora.12571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferguson GM, Fiese BH, Nelson MR, Meeks Gardner JM. Transdisciplinary team science for global health: Case study of the JUS Media? Programme. Am Psychol 2019. September;74(6):725–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferguson GM, Iturbide MI. Jamaican boys’ construals of Jamaican and American teenagers. Caribb J Psychol 2013;5(1):65–84. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harrison K, Bost KK, McBride BA, Donovan SM, Grigsby-Toussaint DS, Kim J, et al. Toward a Developmental Conceptualization of Contributors to Overweight and Obesity in Childhood: The Six-Cs Model: Developmental Ecological Model of Child Obesity. Child Dev Perspect 2011. March;5(1):50–8. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee A, & Gibbs SE (2013). Neurobiology of food addiction and adolescent obesity prevention in low-and middle-income countries. Journal of adolescent health, 52(2), S39–S42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Popkin BM, Adair LS, Ng SW. Global nutrition transition and the pandemic of obesity in developing countries. Nutr Rev 2012. January;70(1):3–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kearney J Food consumption trends and drivers. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci 2010. September 27;365(1654):2793–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacobs A, Richtel M. How big business got Brazil hooked on junk food: As growth slows in wealthy countries Western food companies are aggressively expanding in developing nations, contributing to obesity and health problems. New York Times [Internet]. 2017 Sep 16; Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/09/16/health/brazil-obesity-nestle.html

- 11.Jensen LA. Globalization: Human Development in a New Cultural Context. In: Oxford handbook of cultural neuroscience and global mental health. New York: Oxford University Press, New Jork; in press. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sadeghirad B, Duhaney T, Motaghipisheh S, Campbell NRC, Johnston BC. Influence of unhealthy food and beverage marketing on children’s dietary intake and preference: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials: Meta-analysis of unhealthy food and beverage marketing. Obes Rev 2016. October;17(11):945–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.SelectUSA. Media and entertainment spotlight: The media and entertainment industry in the United States. [Internet]. Available from: https://www.selectusa.gov/media-entertainment-industry-united-states

- 14.Gordon NSA. Globalization and Cultural Imperialism in Jamaica: The Homogenization of Content and Americanization of Jamaican TV through Programme Modeling. Int J Commun 2009;3:307–31. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abarca-Gómez L, Abdeen ZA, Hamid ZA, Abu-Rmeileh NM, Acosta-Cazares B, Acuin C, et al. Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128·9 million children, adolescents, and adults. The Lancet 2017. December;390(11113):2627–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nelson MR, Ahn R, Giray C, Ferguson GM. Globalization and “Jahmerican” Food Advertising in Jamaica. Paper presented at the global conference of the American Academy of Advertising, Tokyo, Japan. 2017; [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nelson MR, Ahn RJ, Ferguson GM, Anderson A. Consumer exposure to food and beverage advertising out of home: An exploratory case study in Jamaica. Int J Consum Stud 2020. May;44(3):272–84. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferguson GM, Adams BG. Americanization in the Rainbow Nation: Remote Acculturation and Psychological Well-Being of South African Emerging Adults. Emerg Adulthood. 2016. April 1;4(2):104–18. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brown JD (2006). Media literacy has potential to improve adolescents’ health. Journal of Adolescent Health, 39(4), 459–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brownell KD, Schwartz MB, Puhl RM, Henderson KE, & Harris JL (2009). The need for bold action to prevent adolescent obesity. Journal of Adolescent Health, 45(3), S8–S17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lowe CJ, Morton JB, Reichelt AC. Adolescent obesity and dietary decision making—a brain-health perspective. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020. May;4(5):388–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Healthy Caribbean Coalition. My healthy Caribbean school: Monitoring the health of Caribbean schools. HealthyCaribbean [Internet]. HealthyCaribbean.Org; Available from: https://www.healthycaribbean.org/cop/my-healthy-school.php

- 23.Nelson MR. Developing Persuasion Knowledge by Teaching Advertising Literacy in Primary School. J Advert 2016. April 2;45(2):169–82. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Powell RM, Gross T Food for Thought: A Novel Media Literacy Intervention on Food Advertising Targeting Young Children and their Parents. J Media Lit Educ [Internet]. 2018. October 1 [cited 2020 Sep 17];10(3). Available from: https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/jmle/vol10/iss3/5/ [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vaughn SR, Schumm JS, & Sinagub JM. Focus group interviews in education and psychology. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Primack BA, Gold MA, Land SR, & Fine MJ (2006). Association of cigarette smoking and media literacy about smoking among adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 39(4), 465–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carducci V Culture Jamming: A Sociological Perspective. J Consum Cult 2006. March;6(1):116–38. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goldstein NJ, Cialdini RB, Griskevicius V. A Room with a Viewpoint: Using Social Norms to Motivate Environmental Conservation in Hotels. J Consum Res 2008. October;35(3):472–82. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jamaica Ministry of Health and Wellness. Food based dietary guidelines [Internet]. 2015. Available from: https://www.moh.gov.jm/programmes-policies/food-based-dietary-guidelines/

- 30.Wright JA, Whiteley JA, Laforge RG, Adams WG, Berry D, Friedman RH. Validation of 5 Stage-of-Change Measures for Parental Support of Healthy Eating and Activity. J Nutr Educ Behav 2015. March;47(2):134–142.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jackson M, Walker S, Cade J, Forrester T, Cruickshank J, Wilks R. Reproducibility and validity of a quantitative food-frequency questionnaire among Jamaicans of African origin. Public Health Nutr 2001. October;4(5):971–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.White IR, Carpenter J, Horton NJ. Including all individuals is not enough: Lessons for intention-to-treat analysis. Clin Trials J Soc Clin Trials. 2012. August;9(4):396–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tripepi G, Chesnaye NE, Dekker FW, Zoccali C, Jager KJ. Intention to treat and per protocol analysis in clinical trials. Nephrology. 2020. March; 25(7): 513–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hernán MA, Hernández-Diaz S Beyond the intention-to-treat in comparative effectiveness research. Clinical Trials. 2012; 9:48–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Greenhouse SW; Geisser S (1959). On methods in the analysis of profile data. Psychometrika. 24: 95–112. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006. January;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Masten AS. Ordinary magic: Resilience in development. New York, NY: Guildford Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bryan CJ, Yeager DS, Hinojosa CP. A values-alignment intervention protects adolescents from the effects of food marketing. Nat Hum Behav 2019. June;3(6):596–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Folkvord F, Anschütz DJ, Boyland E, Kelly B, Buijzen M. Food advertising and eating behaviour in children. Appetite 2016. December;107:681. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Arillo-Santillán E, Unger JB, Thrasher J. Remote Acculturation and Cigarette Smoking Susceptibility Among Youth in Mexico. J Cross-Cult Psychol 2019. January;50(1):63–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]