Abstract

Background

Anthocyanins, which belong to flavonoids, are widely colored among red-purple pigments in the Asiatic hybrid lilies (Lilium spp.). Transcription factor (TF) LhMYBSPLATTER (formerly known as LhMYB12-Lat), identified as the major kernel protein, regulating the anthocyanin biosynthesis pathway in ‘Tiny Padhye’ of Tango Series cultivars, which the pigmentation density is high in the lower half of tepals and this patterning is of exceptional ornamental value. However, the research on mechanism of regulating the spatial and temporal expression differences of LhMYBSPLATTER, which belongs to the R2R3-MYB subfamily, is still not well established. To explore the molecular mechanism of directly related regulatory proteins of LhMYBSPLATTER in the anthocyanin pigmentation, the yeast one-hybrid (Y1H) cDNA library was constructed and characterized.

Results

In this study, we describe a yeast one-hybrid library to screen transcription factors that regulate LhMYBSPLATTER gene expression in Lilium, with the library recombinant efficiency of over 98%. The lengths of inserted fragments ranged from 400 to 2000 bp, and the library capacity reached 1.6 × 106 CFU of cDNA insert, which is suitable to fulfill subsequent screening. Finally, seven prey proteins, including BTF3, MYB4, IAA6-like, ERF4, ARR1, ERF WIN1-like, and ERF061 were screened by the recombinant bait plasmid and verified by interaction with the LhMYBSPLATTER promoter. Among them, ERFs, AUX/IAA, and BTF3 may participate in the negative regulation of the anthocyanin biosynthesis pathway in Lilium.

Conclusion

A yeast one-hybrid library of lily was successfully constructed in the tepals for the first time. Seven candidate TFs of LhMYBSPLATTER were screened, which may provide a theoretical basis for the study of floral pigmentation.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12870-021-03347-1.

Keywords: Lilium, Anthocyanins, Transcriptional factor, Yeast one-hybrid library, LhMYBSPLATTER

Background

Lily (Lilium spp.), a worldwide ornamental flower, has a significant range of flower colors, mainly composed of anthocyanins. Anthocyanins are among the secondary metabolites that contribute to the colors of tepals. Anthocyanins play important roles in UV-B protection, pathogen, and biotic stress defenses, attracting pollinators and seed-dispersing animals [1–4]. Additionally, anthocyanins in the tepals of flowers among cultivars is the important horticultural characteristic that directly determines the aesthetic and commercial value of floricultural crops [5, 6]. Spatially and temporally distinct anthocyanin accumulation in tepals of lilies leads to various colour patterning, including bicolor and spots (raised spots and splatter-type spots), such as the Asiatic hybrid lilies Tango Series cultivars ‘Tiny Padhye’, in which anthocyanins are specifically colored in the basal tepals (referred to as splatter-type spots) and have special ornamental value [6]. LhMYB12-Lat which derived from the Asiatic hybrid lilies cv. ‘Tiny Padhye’ causing splatter-type spots, was renamed LhMYBSPLATTER (LhMYBSPL) because it was not an allele gene of LhMYB12 [7]. LhMYBSPLATTER, the kernel of the MBW transcriptional complex that was composed of MYB, bHLH and WD40 transcription factors (TFs), regulated the structural genes in splatter-type anthocyanin biosynthesis [8] and transport pathways [9] in Tango Series cultivars of Asiatic hybrid lilies. Thus, LhMYBSPLATTER is a crucial transcription factor among various pathways that regulates pigmentation at splatter-type spots in lilies.

In the plants, anthocyanins accumulation during flower development is induced by environmental (exogenous) and developmental (endogenous) factors, including stress-response factors (BBX, HY5, NAC, and WRKY) [10–15], certain growth hormone-response factors (ERF, ARF/IAA, and bZIP) [16–26], and nutritional factors (BT2 and LBD) [21, 27, 28]. Among them, the target MYB gene expression may be controlled by response factors based on DNA cis-elements, which caused differential anthocyanin contents and coloring.

The yeast one-hybrid system is generally used to screen prey protein interactions based on bait DNA promoter sequence and analyze transcriptional regulation controlled by TFs that bind to DNA cis-elements located in the gene promoters [29]. Therefore, candidate prey proteins could be obtained by yeast one-hybrid assay, such as in wheat [30], Arabidopsis [31, 32], Populus [33], tobacco [34], Cymbidium [35] etc. Nevertheless, until now, the TFs acting on the LhMYBSPLATTER gene promoter that positively/negatively responds to anthocyanin biosynthesis and accumulation remains unclear in flower plants.

LhMYBSPLATTER, a positive transcription factor, was shown to regulate pigmentation at splatter-type spots in the Asiatic hybrid lilies Tango Series cultivars, and its expression was consistent with that of anthocyanin structural genes [8, 36]. However, the mechanism by which upstream regulation leads to differential expression of LhMYBSPLATTER has rarely been studied. Therefore, the present study aimed to screen the prey interaction proteins and determine the TFs specifically directly binding to the LhMYBSPLATTER gene promoter based on a yeast one-hybrid system. The findings of this study may provide a further understanding of the regulatory pathway of anthocyanin in lily.

Results

Cloning of LhMYBSPLATTER promoter

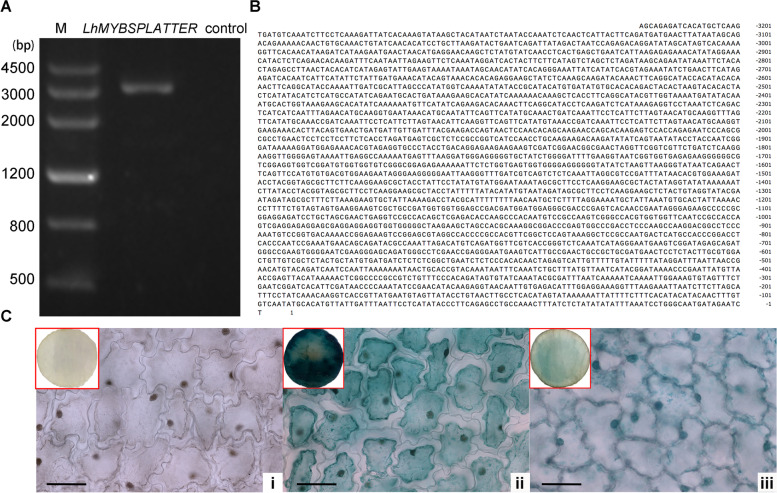

The lily LhMYBSPLATTER promoter was isolated based on amplifying promoter sequences primers using the genome walking method and submitted as MW719044. The PCR products, a 3222 bp length, were verified by agarose gel electrophoresis (Fig. 1a) and shown in Fig. 1b. The cis-elements and transcription factor binding sites showed ABA-, auxin-, MeJA-, gibberellin-, ethylene-, light-, and stress-responsive elements by online software PlantCARE and PlantPAN 2.0 in LhMYBSPLATTER promoter sequence (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Cloning of LhMYBSPLATTER promoter and GUS expression levels in the disc of lily tepals. A Electrophoretic diagram of cloned LhMYBSPLATTER promoter. B Sequencing result of cloned LhMYBSPLATTER promoter. C GUS histochemical staining detected in the disc of tepals transformed by negative control (i), 35S (ii) and LhMYBSPLATTER promoter sequences (iii); bars = 250 μm

Table 1.

Promoter cis-elements prediction

| Element | Sequence | Position | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| A-box | CCGTCC | − 912 to − 907 | cis-acting regulatory element |

| ABRE | ACGTG | − 2726 to − 2722 | ABA-responsive element |

| ATCT-motif | AATCTAATCC | − 3154 to − 3144 | part of a conserved DNA module involved in light-responsiveness |

| ARR | CAAATCT | − 447 to − 441 | ARR motif |

| Box II | ACACGTAGA | − 1882 to − 1874 | part of a light-responsive element |

| Box 4 | ATTAAT | − 216 to − 211 | light-responsive element |

| CAAT-box | CAAT | −98 to − 95 | common cis-acting element in promoter and enhancer regions |

| CAT-box | GCCACT | − 935 to − 930 | cis-acting regulatory element related to meristem expression |

| CGTCA-motif | CGTCA | − 1587 to − 1583 | cis-acting regulatory element involved in the MeJA-responsiveness |

| G-box | CACGTG | − 1513 to − 1508 | cis-acting regulatory element involved in light-responsiveness |

| GATA-motif | GATAGGA | − 198 to − 192 | part of a light-responsive element |

| GC-motif | CCCCCG | − 1107 to − 1102 | enhancer-like element involved in anoxic specific inducibility |

| GCC-box | CCGCCGTC | − 376 to − 369 | ethylene-responsive element |

| GCN4_motif | TGAGTCA | − 821 to − 815 | cis-regulatory element involved in endosperm expression |

| GT1-motif | GGTTAA | − 507 to − 502 | light-responsive element |

| HSE | AGAANNTTCT | − 2869 to − 2861 | HSF element |

| LAMP-element | CTTTATCA | − 2467 to − 2460 | part of a light-responsive element |

| LTR | CCGAAA | − 792 to − 787 | cis-acting element involved in low-temperature responsiveness |

| MBS | CAACTG | − 3091 to − 3086 | MYB binding site involved in drought-inducibility |

| Myb | CAACTG | − 470 to − 465 | Myb motif |

| MYC | CATGTG | − 2540 to − 2539 | MYC element |

| P-box | CCTTTTG | − 3005 to − 2999 | gibberellin-responsive element |

| Sp1 | GGGCGG | − 1673 to − 1668 | light-responsive element |

| TATA-box | TATA | −30 to −27 | core promoter element around − 30 of transcription start |

| TCA-element | CCATCTTTTT | − 1896 to − 1887 | cis-acting element involved in salicylic acid responsiveness |

| TCCC-motif | TCTCCCT | − 1116 to − 1110 | part of a light-responsive element |

| TGA-element | AACGAC | − 1818 to − 1813 | auxin-responsive element |

| TGACG-motif | TGACG | −1587 to −1583 | cis-acting regulatory element involved in the MeJA-responsiveness |

| W box | TTGACC | − 2561 to − 2556 | WRKY motif |

GUS activity assay

To verify whether the promoter of LhMYBSPLATTER could impact the expression of the LhMYBSPLATTER gene, we constructed proLhMYBSPLATTER::GUS recombination plasmid to infect the disc of lily tepals. The promoter activity can be directly reflected by GUS staining. As shown in Fig. 1c, GUS staining results showed that the LhMYBSPLATTER promoter could activate gene expression of LhMYBSPLATTER in lily tepals.

Construction of a cDNA library

The Asiatic hybrid lily ‘Tiny Padhye’ upper tepals and bases of tepals from the S2 stage were collected for total RNA extraction. The quality of the total RNA samples is shown in Fig. S1, showing the bands corresponding to the intact 28S and 18S rRNA. The total RNAs had an A260/A280 ratio of 2.06–2.10 and a concentration of 480–556 ng/μL, which fulfilled the conditions for constructing a cDNA library.

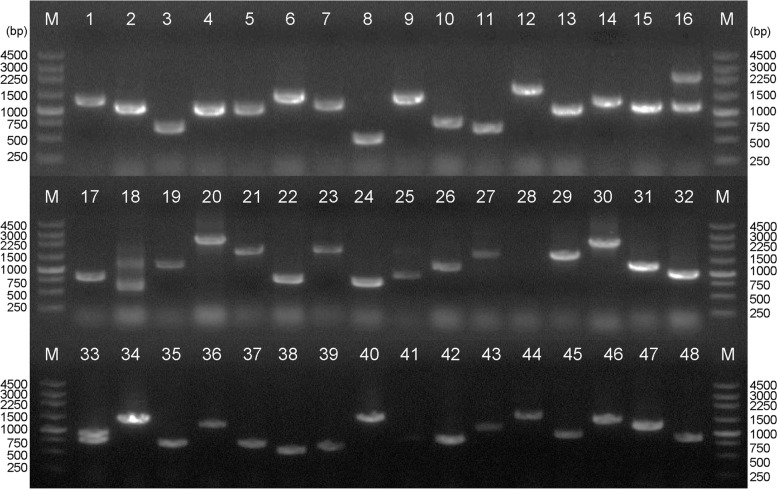

Agarose gel electrophoresis showed that the cDNA library was successfully constructed, and the primary library volume was above 1.6 × 106 CFU, with a recombination efficiency of more than 98%. The homogenization results verified that the redundancy rate was 1% by sequencing 96 single positive clones (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of positive, healthy colonies sequencing to quantify the cDNA library from randomly selected 48 colonies

Construction of bait-reporter strains and determining AbA concentration

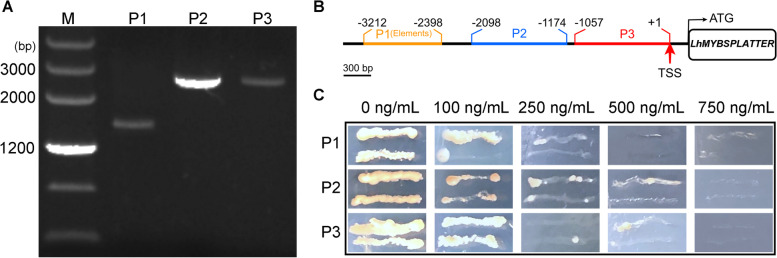

As shown in Fig. 3a, the colony PCR results were consistent with the expected size of PCR products (1.35 kb plus the inserted fragment), identifying correct integration into yeast cells.

Fig. 3.

Construction of bait-yeast strains and minimum concentrations of AbA for inhibiting self-activation. A Agarose gel for reconstructing bait-reporter strains; M: Marker; P1: LhMYBSPLATTER-P1(elements); P2: LhMYBSPLATTER-P2; P3: LhMYBSPLATTER-P3. B Schematic diagram of LhMYBSPLATTER promoter fragments. C The minimum inhibitory concentration of AbA

To exclude yeast transcription factors for target sequence recognition, we measured minimum concentrations of AbA for inhibiting self-activation. As shown in Fig. 3b-c, basal expression of pAbAi-LhMYBSPLATTER-P1(elements), pAbAi-LhMYBSPLATTER-P2 and pAbAi-LhMYBSPLATTER-P3 bait strains were 250 ng/mL, 500 ng/mL, and 500 ng/mL, respectively.

Screening of a yeast one-hybrid library

pAbAi-LhMYBSPLATTER-P1(elements), pAbAi-LhMYBSPLATTER-P2, and pAbAi-LhMYBSPLATTER-P3 yeast cell suspensions obtained on SD/−Leu plates were diluted to 1/100, and 124, 77, and 20 clones, respectively. The number of screened clones were 1.9 × 106, 1.2 × 106, and 0.3 × 106, respectively.

Extraction of the prey plasmids and confirming positive interactions

The positive colonies of pAbAi-LhMYBSPLATTER-P1(elements), pAbAi-LhMYBSPLATTER-P2 and pAbAi-LhMYBSPLATTER-P3 were selected from the SD/−Leu plates, 149, 140, and 141 clones, respectively, and grow on SD/−Leu brown media to extract the prey plasmids. Then, the extracted plasmids were transferred with prey strains to the SD/−Leu medium containing the appropriate concentration of AbA, and the pGADT7 plasmid was used as a negative control. The positive plasmids of the growing yeast strains were identified that regulate the expression of the LhMYBSPLATTER gene by interacting with cis-elements in the LhMYBSPLATTER promoter. Finally, the confirmed sequences of lily were compared by Blastx (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi), including Zinc finger, ERF, GRP, and MYB predicted proteins, which originate from Elaeis guineensis, Phoenix dactylifera, and Musa acuminata (Table 2).

Table 2.

Screening results of LhMYBSPLATTER promotor transcriptional factors

| Position | Accession number | Biological annotation | Species |

|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | AEU17861.1 | heat shock transcription factor | Lilium longiflorum |

| P1 | XP_012476945.1 | basic transcription factor 3 | Gossypium raimondii |

| P1 | ASV46333.1 | MYB4 | Lilium regale |

| P1 | XP_010913061.1 | zinc finger CCCH domain-containing protein ZFN-like isoform X2 | Elaeis guineensis |

| P2 | XP_008810485.1 | auxin-responsive protein IAA6-like isoform X1 | Phoenix dactylifera |

| P2 | XP_009412068.1 | ethylene-responsive transcription factor 4 | Musa acuminata |

| P2 | XP_009387936.1 | ethylene-responsive transcription factor ERF071-like | Musa acuminata |

| P2 | XP_030477126.1 | gibberellin-regulated protein 6 | Syzygium oleosum |

| P3 | XP_010905671.1 | two-component response regulator ARR1 | Elaeis guineensis |

| P3 | XP_008804592.1 | ethylene-responsive transcription factor WIN1-like | Phoenix dactylifera |

| P3 | XP_010913767.1 | ethylene-responsive transcription factor ERF061 | Elaeis guineensis |

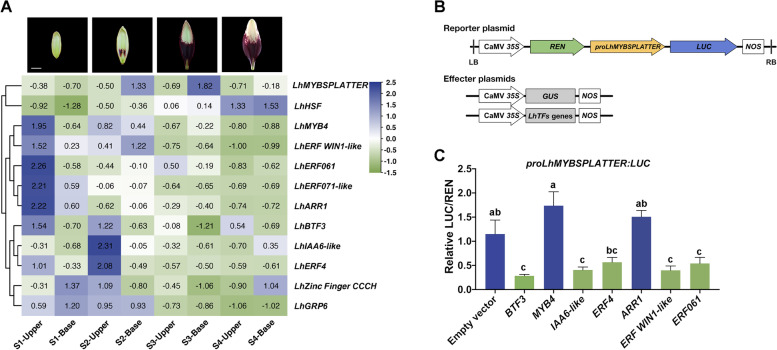

Expression analysis of candidate TFs of LhMYBSPLATTER

To verify the interaction between the expression levels of candidate TFs and LhMYBSPLATTER, we analyzed the expression of candidate TFs genes in ‘Tiny Padhye’ tepals by qRT-PCR. We found that expression levels of most genes tested were significantly different in the upper and basal tepals (Fig. 4a). These results suggest that the genes (MYB4, ERF WIN1-like, ERF061, ERF071-like, ARR1, BTF3, IAA6-like, and ERF4) may be involved in the suppression of LhMYBSPLATTER-mediated anthocyanin biosynthesis regulation in lily. However, we found the expression of HSF, ZF CCCH and GRP6 genes were no significant differences in the upper and basal tepals, which indicated that the difference in anthocyanin contents caused by LhMYBSPLATTER expression level was not significantly co-related to HSF, ZF CCCH and GRP6 genes.

Fig. 4.

Genes expression analysis and detecting LUC/REN activity to verify candidate transcription factors co-transformation to activate the LhMYBSPLATTER promoter. A Variation of candidate genes expression in Y1H screen library. The value indicated the temporal and spatial expression of candidate genes treated with log2. B Schematic diagram of vectors used for the dual-luciferase assay. C Dual-luciferase assay showing relative LhMYBSPLATTER activation to the transcription factor genes obtained by screening library. Each experiment was triplicated, and the results were analyzed as average value ± SD

LUC reporter assay

We performed LUC reporter assays to determine how several potential TF genes regulate the activity levels of proLhMYBSPLATTER. As shown in Fig. 4b-c, BTF3, IAA6-like, ERF4, ERF WIN1-like, ERF061 negative regulated proLhMYBSPLATTER, but MYB4 and ARR1 barely affected the activity level of proLhMYBSPLATTER. Thus, BTF3, IAA6-like, ERF4, ERF WIN1-like, ERF061 was found to mainly suppress proLhMYBSPLATTER to negative regulate anthocyanin accumulation in lily.

Discussion

The yeast one-hybrid system is commonly recognized as a useful technique for detecting new DNA-protein interactions with regulation pathways and is widely used in functional genomics studies [37, 38]. In general, the vital standards for constructing a high-quality yeast-one hybrid library include the purity, integrity and concentration of mRNA. The recombination efficiency, transformation efficiency, and library capacity, including the integral expression information, must contain at least 1 × 106 CFU [35, 39]. In this study, the three indexes of the yeast library of Lilium were 98%, 400–2000 bp and 1.6 × 106 CFU/mL of cDNA insert, respectively, which fulfilled the requirements for further library screening.

By screening a high-quality library of interactions between target prey proteins and bait plasmid links in regulatory networks enables fast and effective identification in higher organisms [31, 35, 40, 41]. In this study, we successfully constructed a high-quality cDNA library of LhMYBSPLATTER gene promoter that can be used for yeast one-hybrid assays, providing strong evidences that unknown proteins with functional identification of regulating anthocyanin biosynthesis in Asiatic hybrid lily. Therefore, the present study screened several potential TF genes, including various stresses and growth hormones, such as ARR1 (MW719046), HSF (MW719048), ERF WIN1-like (MW719031), IAA6-like (MW719034), and ERF4 (MW719035).

Among them, BTF3, IAA6-like, ERF4, ERF WIN1-like, ERF061, and ERF071-like may bind to the LhMYBSPLATTER promoter and have an inhibitory regulation to LhMYBSPLATTER. IAA6-like were identified from LhMYBSPLATTER-P2, which encoded an AUX/IAA protein containing an N terminal DNA binding domain [42]. Auxin signaling, which is crucial for normal plant growth and development, including those related to flavonoid and anthocyanin metabolism, mainly depends on ARF-Aux/IAA interactions [21, 25]. In apple, the study proved that adding NAA alone suppressed anthocyanin synthesis even at low concentrations, and the higher concentration of NAA, the more severe inhibition of anthocyanin biosynthesis [21, 25, 43]. Moreover, treating strawberry fruits with exogenous auxin can delay fruit ripening by down-regulating the expression of genes related to anthocyanin synthesis [44], which was similar to the modulation we hypothesized here. In this study, a target protein homologous to an anthocyanin-related protein in lily was screened out based on the LhMYBSPLATTER promoter as the bait vector, with negatively correlated expression with LhMYBSPLATTER. Therefore, we speculated that ARF might be involved in the transcriptional regulation of the LhMYBSPLATTER promoter in anthocyanin biosynthesis. Additionally, ERF TFs, a large family of TFs that feature the conserved AP2/ERF domain, play key roles in plant growth, development and various stress, including modulating anthocyanin biosynthesis [24, 45]. Recent studies have reported that MdERF was found to interact with proMdMYB9, proMdMYB1 and proMdMYB11 to promote anthocyanin and proanthocyanidin biosynthesis in apple [22, 24]. However, ethylene inhibited anthocyanin biosynthesis in red Chinese pear fruits [23]. Notably, we hypothesized that ERFs screened from the cDNA library may be involved in suppressing anthocyanin biosynthesis, which might contrast with previous studies. Therefore, the regulation mechanism of the anthocyanin biosynthesis by hormone-mediated response factors varies significantly among different species.

In addition, there are several light-responsive elements in the LhMYBSPLATTER promoter sequence. However, light-related TFs, such as ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL5 (HY5) [46] and WRKY family [13] proteins, have not been identified by the yeast-one hybrid library. Moreover, we found that shading the unstained bud did not affect the difference of anthocyanin in the upper and basal tepals. Therefore, we speculated that light might not be the key external factor in the differential expression of anthocyanins between the upper and bases of tepals in lily.

Expression analysis showed that MYB4 and ARR1 were significantly highly expressed in the upper tepal at S1 stage, so we hypothesized that they might have an inhibitory effect on the regulation of anthocyanin biosynthesis. However, the dual-luciferase assay found that they might be involved in the positive regulation of the anthocyanin biosynthesis pathway. Therefore, we speculated that there may be feedback regulation in lily, further verified by functional studies.

Among the candidate TFs for LhMYBSPLATTER promoter screened by the yeast-one hybridization, positive regulators of which expression dramatically upregulate in the basal tepals at S1 and S2 stages are somewhat regrettably not included. We speculated that it might be due to the expression of LhMYBSPLATTER gene began to differ significantly in the upper and basal tepals during S2 stage when a cDNA library was constructed. However, the tepals had already accumulated anthocyanin during S2 stage, leading to the failure to screen positive TFs that regulate LhMYBSPLATTER gene, but a large number of TFs were screened to inhibit anthocyanin accumulation in the upper tepals.

In addition, upstream of the start codon, LhMYBSPLATTER sequence from − 357 to − 11 and from − 163 to 1 showed high similarity to LhMYB12-Lollypop (DDBJ database, LC612729) and LhMYB19S-Lollypop (DDBJ database, LC612730) sequences, respectively. The similar region was longer between LhMYBSPLATTER and LhMYB12-Lollypop than between LhMYBSPLATTER and LhMYB19S-Lollypop. Interestingly, the coding region and 5′ terminal sequence of LhMYBSPLATTER derived from ‘Tiny Padhye’ is completely consistent with that of LhMYBSPLATTER-Latvia (NCBI database, AB827442.1) that is not allele gene with LhMYB12-Lollypop [7]. Thus, an ancestral sequence of LhMYBSPLATTER, LhMYB12-Lollypop and LhMYB19S-Lollypop were likely mutated in their promoter region, giving rise to functional difference for anthocyanin pigmentation [47].

Conclusions

In conclusion, the identified TFs from LhMYBSPLATTER promoter and screened high-quality cDNA library may help get a deep insight into the regulatory pathway of anthocyanin in lily. Our results are the first to identify them in tepals, and may provide theoretical support and possible research directions for identifying the regulatory associations between potential TFs and LhMYBSPLATTER gene promoter. Further studies are still needed to verify their functions as anthocyanin regulators.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

The Asiatic hybrid lily Tango Series cultivar ‘Tiny Padhye’ were obtained commercially from Zhejiang Licai garden company limited (Zhejiang, China) and were grown in a greenhouse at the Institute of Vegetables and Flowers, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Beijing, China). Flowers were divided into four stages (S1-S4) [8]. The flowers of inner tepals were collected at S2 stage, in which 20 tepals as one biological sample and three biological replicates for each tissue, and upper tepals and bases of inner tepals were collected separately and then frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at − 80 °C until further use. The Oriental hybrid lily cv. ‘Sorbonne’ were used for GUS staining.

Cloning of LhMYBSPLATTER promoter

Genomic DNA was isolated from ‘Tiny Padhye’ upper tepals and bases of tepals (S1-S4) using Hi-DNAsecure Plant Kit (polysaccharide & polyphenolic-rich) (TIANGEN, Beijing, China), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The promoter of LhMYBSPLATTER was amplified using Genome Walking Kit (Clontech, Dalian, China) by SP1-SP3 primers (Table S1). The motif of the promoter was analyzed by online software of PlantCARE (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/) and PlantPAN 2.0 (http://plantpan2.itps.ncku.edu.tw).

Construction of the β-glucuronidase (GUS) expression vector

The promoter region of LhMYBSPLATTER was ligated to the pBI121 vector with a GUS tag, generating constructs proLhMYBSPLATTER::GUS plasmid using homologous recombination. The empty pBI121-GUS vector served as a positive control. The constructed vector and empty vector were introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain EHA105, and the A. tumefaciens strain was infiltrated into the disc of tepals of the Oriental hybrid lily cv. ‘Sorbonne’ with a higher anthocyanin accumulation [48]. The primers used to amplify the promoter of LhMYBSPLATTER with linker are listed in Table S1.

Creating a yeast one-hybrid cDNA library

Total RNA was extracted from ‘Tiny Padhye’ upper tepals and bases of S2 stage tepals using an RNAprep Pure Plant Kit (polysaccharide & polyphenolic-rich) (TIANGEN, Beijing, China), quickly frozen in liquid nitrogen and then stored at − 80 °C until further use. A cDNA library of ‘Tiny Padhye’ was synthesized and mixed using SMART cDNA Library Construction Kit and Advantage II PCR Kit (Clontech, CA, USA). The cDNA was normalized using Trimmer Direct cDNA Normalization Kit, purified by TaKaRa MiniBEST DNA Fragment Purification Kit (Takara, CA, USA), and enriched using a CHROMA SPIN-1000-TE (Clontech, CA, USA). After enriched, cDNA was ligated into the pGADT7-SfiI vector using DNA ligation Kit, and then a normalized cDNA library of ‘Tiny Padhye’ was obtained by purification.

Construction of bait plasmids

The promoter sequence of LhMYBSPLATTER was divided into P1(elements), P2 and P3, and cloned into pAbAi vector digested with SacI and XhoI, respectively. The primers used to amplify the coding sequences and the promoter region are listed in Table S1. The LhMYBSPLATTER promoter products with linker were purified on 1% agarose gel and ligated into the linearized bait pAbAi vector using homologous recombination. The ligated products were transformed into E. coli DH5α competent cells and positive recombinant clones were screened using LB media containing ampicillin.

Transformation of linearized bait plasmids into yeast cells

The recombinant plasmids were digested with BstBI/BbsI, integrated into the yeast genome (Y1H Gold) using the PEG/LiAc method, and transferred onto solid agar synthetic defined (SD) medium -Ura and incubated for 2–3 days. The positive recombinant clones were identified by PCR using Matchmaker Insert Check PCR Mix 1 (Clontech, CA, USA). The empty pAbAi vector was identified as a positive control with a PCR product size of 1.4 kb. Then, the recombinant bait-reporter yeast strains were screened on SD/−Ura medium with optimal Aureobasidin A (AbA) concentration to suppress and selected onto each of the following media: SD/−Ura without AbA, SD/−Ura with 100 ng/mL AbA, SD/−Ura with 250 ng/mL AbA, SD/−Ura with 500 ng/mL AbA, SD/−Ura with 750 ng/mL AbA, and SD/−Ura with 1000 ng/mL AbA. The bait-reporter yeast strains were grown for 3 days at 28–30 °C, and the minimum AbA concentration that could completely inhibit strains was determined to use for further library screening.

Screening of a Y1H library

A cDNA library (5 μg) was transformed with bait reporter yeasts. Then yeast cell was resuspended in 0.9% NaCl (approximately 15 mL) and spread 100 μL of 1/10, 1/100 dilutions on each SD/−Leu with optimal AbA concentration for 3–5 days. Afterwards, the number of colonies were calculated using the following formula: Transformation efficiency = [CFU/mL on SD/−Leu] × [dilution factor] × [resuspension volume (15 mL)].

Confirming positive interactions and extracting the prey plasmids

Positive clones from plates of screening Y1H library were re-transferred into new SD/−Leu medium with same AbA concentration for 3–5 days incubation. To determine the positive interaction, single clones were re-streaked 2–3 times for incubation. Then genuine positive colonies used the Matchmaker Insert Check PCR Mix 2 (Clontech, CA, USA) to amplify prey library inserts. Analyze PCR products by electrophoresis on a 1.0% TBE agarose gel. The healthy generated single colonies were segregated in broth SD/−Leu media and prepared to extract the library plasmids from yeast, using TIANprep Yeast Plasmid DNA Kit (TIANGEN, Beijing, China), following the manufacturer instruction. The pGADT7-Recexpression vector (5 μL) was transformed into E. coli DH5α competent cells and screened using LB media containing ampicillin at 37 °C for 12 h. After culture, the plasmids from the LB medium were extracted by TIANpure Mini Plasmid Kit (TIANGEN, Beijing, China) for co-transformation and sequencing.

Quantitative real-time PCR analysis

Total RNA was isolated from ‘Tiny Padhye’ upper and basal tepals in four stages using an RNAprep Pure Plant Kit (polysaccharide & polyphenolic-rich) (TIANGEN, Beijing, China), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, the first-strand cDNA was synthesized using TransScript® II One-Step gDNA Removal and cDNA Synthesis SuperMix (TransGen Biotech, Beijing, China) and oligo(dT) primers. The qRT-PCR reactions were performed using Perfectstar™ Green qPCR SuperMix (TransGen Biotech, Beijing, China) and a Bio-Rad CFX96 system. The relative expression level of quantification was calculated based on the 2−∆∆Ct formula method [49]. LilyActin was used as an internal control [50]. The primers for RT-qPCR were synthesized by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China; Table S1).

Dual-luciferase transient expression assay

The promoter sequence of LhMYBSPLATTER was recombined into CP516-LUC plasmid as reporter and TFs obtained from the screening library were inserted into pCAMBIA3301 plasmid as an effector. The effector and LUC reporter for normalization were mixed and transformed into the tobacco leaves by Agrobacterium-mediated transient expression for transient transfection. After co-infected with 2–3 days in the normal grown condition at room temperature, the LUC and REN values were determined using a GloMax® 20/20 Luminometer (Promega, USA). A Dual-Luciferase Reporter Gene Assay Kit (Yeasen, Shanghai, China) was used to detect the LUC/REN activity. The relative LUC activity was measured from the ratio of LUC to REN values. Each experiment was triplicated and the results were analyzed as average value ± SD.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1. The list of primers used in this study.

Additional file 2: Figure S1. Total RNA extracted from flowers tepals at S2 stage. The line 1 indicated the upper tepals and the line 2 indicated basal tepals.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Xia Cui (Institute of Vegetables and Flowers, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences) for kindly offering CP516 vector.

Abbreviations

- TFs

Transcription factors

- Y1H

Yeast one-hybrid

- BTF3

Basic transcription factor 3

- ERF

Ethylene response factor

- GRP

Gibberellin-regulated protein

- qRT-PCR

Real-time quantitative PCR

- HY5

ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL 5

Authors’ contributions

J.M., L.X. and P.Y. contributed to the conception of the experiment.; Y.C., M.B. and M.S. performed the experiments; Y.C., G.H., J.W. and Y.Y. revised the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31672196, 31801899, 31902043), the National Key R@D Program of China (2018YFD1000405, 2019YFD1001002). The funders had no role in study design, data analysis and interpretation, or preparation of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The sequence datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the NCBI repository, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/MW719044.1/, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/MW719048.1/, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/MW719030.1/, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/MW719038.1/, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/MW719043.1/, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/MW719034.1/, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/MW719035.1/, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/MW719037.1/, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/MW719039.1/, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/MW719046.1/, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/MW719031.1/, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/MW719032.1/. The data set supporting the results of this article are included in the article and Additional files.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Yuwei Cao, Email: caoyuwei1103@163.com.

Mengmeng Bi, Email: bimengmenga@163.com.

Panpan Yang, Email: yangpanpan@caas.cn.

Meng Song, Email: 15558111707@126.com.

Guoren He, Email: hgr0222@sina.com.

Jing Wang, Email: 1606042188@qq.com.

Yue Yang, Email: yangyuework@126.com.

Leifeng Xu, Email: xuleifeng@caas.cn.

Jun Ming, Email: mingjun@caas.cn.

References

- 1.Winkel-Shirley B. It takes a garden. How work on diverse plant species has contributed to an understanding of flavonoid metabolism. Plant Physiol. 2001;127(4):1399–1404. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grotewold E. The genetics and biochemistry of floral pigments. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2006;57:761–780. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azuma A, Yakushiji H, Sato A. Postharvest light irradiation and appropriate temperature treatment increase anthocyanin accumulation in grape berry skin. Postharvest Biol Technol. 2019;147:89–99. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Long L, Liu J, Gao Y, Xu FC, Zhao JR, Li B, Gao W. Flavonoid accumulation in spontaneous cotton mutant results in red coloration and enhanced disease resistance. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2019;143:40–49. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2019.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamagishi M, Shimoyamada Y, Nakatsuka T, Masuda K. Two R2R3-MYB genes, homologs of Petunia AN2, regulate anthocyanin biosyntheses in flower tepals, tepal spots and leaves of Asiatic hybrid lily. Plant Cell Physiol. 2010;51(3):463–474. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcq011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamagishi M. How genes paint lily flowers: regulation of colouration and pigmentation patterning. Sci Hortic. 2013;163:27–36. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamagishi M. White with partially pink flower color in Lilium cernuum var. album is caused by transcriptional regulation of anthocyanin biosynthesis genes. Sci Hortic. 2020;260:108880. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu L, Yang P, Feng Y, Xu H, Cao Y, Tang Y, Yuan S, Liu X, Ming J. Spatiotemporal transcriptome analysis provides insights into bicolor tepal development in Lilium “tiny Padhye”. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:398. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cao Y, Xu L, Xu H, Yang P, He G, Tang Y, Qi X, Song M, Ming J. LhGST is an anthocyanin-related glutathione S-transferase gene in Asiatic hybrid lilies (Lilium spp.) Plant Cell Rep. 2020;40:85. doi: 10.1007/s00299-020-02615-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bai S, Tao R, Tang Y, Yin L, Ma Y, Ni J, Yan X, Yang Q, Wu Z, Zeng Y, et al. BBX16, a B-box protein, positively regulates light-induced anthocyanin accumulation by activating MYB10 in red pear. Plant Biotechnol J. 2019;17(10):1985–1997. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bai S, Tao R, Yin L, Ni J, Yang Q, Yan X, Yang F, Guo X, Li H, Teng Y. Two B-box proteins, PpBBX18 and PpBBX21, antagonistically regulate anthocyanin biosynthesis via competitive association with Pyrus pyrifolia ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL 5 in the peel of pear fruit. Plant J. 2019;100(6):1208–1223. doi: 10.1111/tpj.14510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fang H, Dong Y, Yue X, Hu J, Jiang S, Xu H, Wang Y, Su M, Zhang J, Zhang Z, et al. The B-box zinc finger protein MdBBX20 integrates anthocyanin accumulation in response to ultraviolet radiation and low temperature. Plant Cell Environ. 2019;42(7):2090–2104. doi: 10.1111/pce.13552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu J, Fang H, Wang J, Yue X, Su M, Mao Z, Zou Q, Jiang H, Guo Z, Yu L, et al. Ultraviolet B-induced MdWRKY72 expression promotes anthocyanin synthesis in apple. Plant Sci. 2020;292:110377. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2019.110377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morishita T, Kojima Y, Maruta T, Nishizawa-Yokoi A, Yabuta Y, Shigeoka S. Arabidopsis NAC transcription factor, ANAC078, regulates flavonoid biosynthesis under high-light. Plant Cell Physiol. 2009;50(12):2210–2222. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcp159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sun Q, Jiang S, Zhang T, Xu H, Fang H, Zhang J, Su M, Wang Y, Zhang Z, Wang N, et al. Apple NAC transcription factor MdNAC52 regulates biosynthesis of anthocyanin and proanthocyanidin through MdMYB9 and MdMYB11. Plant Sci. 2019;289:110286. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2019.110286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Das PK, Shin DH, Choi SB, Park YI. Sugar-hormone cross-talk in anthocyanin biosynthesis. Mol Cell. 2012;34(6):501–507. doi: 10.1007/s10059-012-0151-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.An XH, Tian Y, Chen KQ, Liu XJ, Liu DD, Xie XB, Cheng CG, Cong PH, Hao YJ. MdMYB9 and MdMYB11 are involved in the regulation of the JA-induced biosynthesis of anthocyanin and proanthocyanidin in apples. Plant Cell Physiol. 2015;56(4):650–662. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcu205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu XJ, An XH, Liu X, Hu DG, Wang XF, You CX, Hao YJ. MdSnRK1.1 interacts with MdJAZ18 to regulate sucrose-induced anthocyanin and proanthocyanidin accumulation in apple. J Exp Bot. 2017;68(11):2977–2990. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erx150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li WF, Mao J, Yang SJ, Guo ZG, Ma ZH, Dawuda MM, Zuo CW, Chu MY, Chen BH. Anthocyanin accumulation correlates with hormones in the fruit skin of ‘Red Delicious’ and its four generation bud sport mutants. BMC Plant Biol. 2018;18(1):363. doi: 10.1186/s12870-018-1595-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kang BG, Burg SP. Role of ethylene in phytochrome-induced anthocyanin synthesis. Planta. 1973;110(3):227–235. doi: 10.1007/BF00387635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ji X-H, Wang Y-T, Zhang R, Wu S-J, An M-M, Li M, Wang C-Z, Chen X-L, Zhang Y-M, Chen X-S. Effect of auxin, cytokinin and nitrogen on anthocyanin biosynthesis in callus cultures of red-fleshed apple (Malus sieversii f.niedzwetzkyana) Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult (PCTOC) 2014;120(1):325–337. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang J, Xu H, Wang N, Jiang S, Fang H, Zhang Z, Yang G, Wang Y, Su M, Xu L, et al. The ethylene response factor MdERF1B regulates anthocyanin and proanthocyanidin biosynthesis in apple. Plant Mol Biol. 2018;98(3):205–218. doi: 10.1007/s11103-018-0770-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ni J, Zhao Y, Tao R, Yin L, Gao L, Strid A, Qian M, Li J, Li Y, Shen J, et al. Ethylene mediates the branching of the jasmonate-induced flavonoid biosynthesis pathway by suppressing anthocyanin biosynthesis in red Chinese pear fruits. Plant Biotechnol J. 2019;18:1223. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.An JP, Zhang XW, Bi SQ, You CX, Wang XF, Hao YJ. The ERF transcription factor MdERF38 promotes drought stress-induced anthocyanin biosynthesis in apple. Plant J. 2020;101(3):573–589. doi: 10.1111/tpj.14555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang YC, Wang N, Xu HF, Jiang SH, Fang HC, Su MY, Zhang ZY, Zhang TL, Chen XS. Auxin regulates anthocyanin biosynthesis through the aux/IAA-ARF signaling pathway in apple. Hortic Res. 2018;5:59. doi: 10.1038/s41438-018-0068-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.An JP, Yao JF, Xu RR, You CX, Wang XF, Hao YJ. Apple bZIP transcription factor MdbZIP44 regulates abscisic acid-promoted anthocyanin accumulation. Plant Cell Environ. 2018;41(11):2678–2692. doi: 10.1111/pce.13393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ren YR, Zhao Q, Yang YY, Zhang TE, Wang XF, You CX, Hao YJ. The apple 14-3-3 protein MdGRF11 interacts with the BTB protein MdBT2 to regulate nitrate deficiency-induced anthocyanin accumulation. Hortic Res. 2021;8(1):22. doi: 10.1038/s41438-020-00457-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rubin G, Tohge T, Matsuda F, Saito K, Scheible WR. Members of the LBD family of transcription factors repress anthocyanin synthesis and affect additional nitrogen responses in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2009;21(11):3567–3584. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.067041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bush SM, Folta S, Lannigan DA. Use of the yeast one-hybrid system to screen for mutations in the ligand-binding domain of the estrogen receptor. Steroids. 1996;61(3):102–109. doi: 10.1016/0039-128x(95)00200-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lopato S, Bazanova N, Morran S, Milligan AS, Shirley N, Langridge P. Isolation of plant transcription factors using a modified yeast one-hybrid system. Plant Methods. 2006;2:3. doi: 10.1186/1746-4811-2-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mitsuda N, Ikeda M, Takada S, Takiguchi Y, Kondou Y, Yoshizumi T, Fujita M, Shinozaki K, Matsui M, Ohme-Takagi M. Efficient yeast one−/two-hybrid screening using a library composed only of transcription factors in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2010;51(12):2145–2151. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcq161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang P, Nolan TM, Yin Y, Bassham DC. Identification of transcription factors that regulate ATG8 expression and autophagy in Arabidopsis. Autophagy. 2020;16(1):123–139. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2019.1598753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Petzold HE, Rigoulot SB, Zhao C, Chanda B, Sheng X, Zhao M, Jia X, Dickerman AW, Beers EP, Brunner AM. Identification of new protein-protein and protein-DNA interactions linked with wood formation in Populus trichocarpa. Tree Physiol. 2018;38(3):362–377. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpx121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang H, Zhou Y, Zhang Y, Wang J, Shi H. Identification of transcription factors of nitrate reductase gene promoters and NRE2 cis-element through yeast one-hybrid screening in Nicotiana tabacum. BMC Plant Biol. 2019;19(1):145. doi: 10.1186/s12870-019-1724-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu Y, Zhou J, Liu Q, Li K, Zhou Y. Construction and characterization of a high-quality cDNA library of Cymbidium faberi suitable for yeast one- and two-hybrid assays. BMC Biotechnol. 2020;20(1):4. doi: 10.1186/s12896-020-0599-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yamagishi M, Toda S, Tasaki K. The novel allele of the LhMYB12 gene is involved in splatter-type spot formation on the flower tepals of Asiatic hybrid lilies (Lilium spp.) New Phytol. 2014;201(3):1009–1020. doi: 10.1111/nph.12572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sun Y, Li Y, Huang G, Wu Q, Wang L. Application of the yeast one-hybrid technique to plant functional genomics studies. Biotechnol Biotechnol Equip. 2017;31(6):1087–1092. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Luo Y, Vijaychander S, Stile J, Zhu L. Cloning and analysis of DNA-binding proteins by yeast one-hybrid and one-two-hybrid systems. Biotechniques. 1996;20(4):564–568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ohara O, Temple G. Directional cDNA library construction assisted by the in vitro recombination reaction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29(4):E22. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.4.e22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hens K, Feuz JD, Deplancke B. A high-throughput gateway-compatible yeast one-hybrid screen to detect protein-DNA interactions. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;786:335–355. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-292-2_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Breton G, Kay SA, Pruneda-Paz JL. Identification of Arabidopsis transcriptional regulators by yeast one-hybrid screens using a transcription factor ORFeome. Methods Mol Biol. 2016;1398:107–118. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-3356-3_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hardtke CS, Berleth T. The Arabidopsis gene MONOPTEROS encodes a transcription factor mediating embryo axis formation and vascular development. EMBO J. 1998;17(5):1405–1411. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.5.1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang CK, Han PL, Zhao YW, Ji XL, Yu JQ, You CX, Hu DG, Hao YJ. Auxin regulates anthocyanin biosynthesis through the auxin repressor protein MdIAA26. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2020;533(4):717–722. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.09.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen J, Mao L, Lu W, Ying T, Luo Z. Transcriptome profiling of postharvest strawberry fruit in response to exogenous auxin and abscisic acid. Planta. 2016;243(1):183–197. doi: 10.1007/s00425-015-2402-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mizoi J, Shinozaki K, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. AP2/ERF family transcription factors in plant abiotic stress responses. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1819(2):86–96. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stracke R, Favory JJ, Gruber H, Bartelniewoehner L, Bartels S, Binkert M, Funk M, Weisshaar B, Ulm R. The Arabidopsis bZIP transcription factor HY5 regulates expression of the PFG1/MYB12 gene in response to light and ultraviolet-B radiation. Plant Cell Environ. 2010;33(1):88–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2009.02061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yamagishi M. High promoter sequence variation in subgroup 6 members of R2R3-MYB genes is involved in different floral anthocyanin color patterns in Lilium spp. Mol Gen Genomics. 2021;296(4):1005–1015. doi: 10.1007/s00438-021-01799-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fatihah HNN, Moñino López D, van Arkel G, Schaart JG, Visser RGF, Krens FA. The ROSEA1 and DELILA transcription factors control anthocyanin biosynthesis in Nicotiana benthamiana and Lilium flowers. Sci Hortic. 2019;243:327–337. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xu L, Xu H, Cao Y, Yang P, Feng Y, Tang Y, Yuan S, Ming J. Validation of reference genes for quantitative real-time PCR during bicolor tepal development in Asiatic hybrid lilies (Lilium spp.) Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:669. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. The list of primers used in this study.

Additional file 2: Figure S1. Total RNA extracted from flowers tepals at S2 stage. The line 1 indicated the upper tepals and the line 2 indicated basal tepals.

Data Availability Statement

The sequence datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the NCBI repository, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/MW719044.1/, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/MW719048.1/, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/MW719030.1/, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/MW719038.1/, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/MW719043.1/, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/MW719034.1/, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/MW719035.1/, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/MW719037.1/, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/MW719039.1/, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/MW719046.1/, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/MW719031.1/, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/MW719032.1/. The data set supporting the results of this article are included in the article and Additional files.