Abstract

High-grade (HG) gastroenteropancreatic (GEP) neuroendocrine neoplasms (NEN) are rare but have a very poor prognosis and represent a severely understudied class of tumours. Molecular data for HG GEP-NEN are limited, and treatment strategies for the carcinoma subgroup (HG GEP-NEC) are extrapolated from small-cell lung cancer (SCLC). After pathological re-evaluation, we analysed DNA from tumours and matched blood samples from 181 HG GEP-NEN patients; 152 neuroendocrine carcinomas (NEC) and 29 neuroendocrine tumours (NET G3). Based on the sequencing of 360 cancer-related genes, we assessed mutations and copy number alterations (CNA). For NEC, frequently mutated genes were TP53 (64%), APC (28%), KRAS (22%) and BRAF (20%). RB1 was only mutated in 14%, but CNAs affecting RB1 were seen in 34%. Other frequent copy number losses were ARID1A (35%), ESR1 (25%) and ATM (31%). Frequent amplifications/gains were found in MYC (51%) and KDM5A (45%). While these molecular features had limited similarities with SCLC, we found potentially targetable alterations in 66% of the NEC samples. Mutations and CNA varied according to primary tumour site with BRAF mutations mainly seen in colon (49%), and FBXW7 mutations mainly seen in rectal cancers (25%). Eight out of 152 (5.3%) NEC were microsatellite instable (MSI). NET G3 had frequent mutations in MEN1 (21%), ATRX (17%), DAXX, SETD2 and TP53 (each 14%). We show molecular differences in HG GEP-NEN, related to morphological differentiation and site of origin. Limited similarities to SCLC and a high fraction of targetable alterations indicate a high potential for better-personalized treatments.

Keywords: neuroendocrine neoplasms, neuroendocrine carcinoma, high-grade, gastroenteropancreatic, genetic alterations, molecular markers

Introduction

High-grade (HG) gastroenteropancreatic (GEP) neuroendocrine neoplasms (NEN) are defined by the presence of neuroendocrine phenotype and a high proliferation rate (Ki-67 > 20%). The HG NEN entity consists of well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumours (NET G3) and poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC) (WHO 2019). GEP-NEC have a particularly unfavourable prognosis, with median overall survival <1 year in advanced, treated cases and only 1 month if untreated (Sorbye et al. 2013, Yamaguchi et al. 2014, Heetfeld et al. 2015, Walter et al. 2017). Currently, the molecular mechanisms behind this aggressive phenotype remain unknown.

Among the HG NEN patients, those with GEP-NET G3 have better survival compared to NEC, but an inferior response to platinum/etoposide-based chemotherapy (Heetfeld et al. 2015). The treatment strategy (platinum/etoposide chemotherapy) for adjuvant and metastatic GEP-NEC has been extrapolated from small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) (Strosberg et al. 2010, Garcia-Carbonero et al. 2016), based on clinical, morphological and immunohistochemical similarities. However, previous studies have revealed clinical differences between SCLC and GEP-NEC, questioning this approach (Brennan et al. 2010, Dasari et al. 2018).

Regarding potential biomarkers, the benefit of platinum-based treatment for pancreatic NEN G3 has been reported to depend on KRAS mutations and loss of RB1 (Hijioka et al. 2017) and studies on NEC have associated microsatellite instability (MSI) with improved prognosis (La Rosa et al. 2012, Sahnane et al. 2015). However, molecular markers for classification, treatment selection and prognosis for HG GEP-NEN are generally lacking. Some molecular features of GEP-NEC with primary sites in the colon, rectum and pancreas have similarities to their adenocarcinoma counterparts of the same organs (Takizawa et al. 2015, Konukiewitz et al. 2018). This could indicate a shared genetic origin, but so far this has not been taken into account in the choice of medical treatment.

The 2019 WHO classification of digestive tumours state that NEC frequently have mutations in TP53 and RB1, whereas pancreatic NET G3 retain the mutation profile of other well-differentiated NET (WHO 2019). More detailed assessments report TP53, KRAS, BRAF and PIK3CA/PTEN as the most frequently mutated genes in GEP-NEC, but studies and number of cases are limited (Vijayvergia et al. 2016, Busico et al. 2020). MEN1, DAXX and ATRX are the most frequently mutated genes in pancreatic G1-G2 NET (Ki-67 < 20%) (Jiao et al. 2011), and similar alterations are reported in pancreatic NET G3 (Yachida et al. 2012, Tang et al. 2016a, Konukiewitz et al. 2018). Mutations in NET G3 outside of the pancreas seem to be rare (Busico et al. 2020). These findings indicate that NET G3 and NEC belong to two different types of malignancies, also on the molecular level, and that molecular characteristics may be used to differentiate and classify NEC from NET G3 in cases where morphology is not sufficient (Tang et al. 2016a,b).

In this study, after pathological re-evaluation, we performed massive parallel sequencing of a panel of 360 cancer-related genes across a large set of GEP-NEC (n = 152) and NET G3 samples (n = 29), all with matched normal tissue (blood). We provide an overview of the molecular landscape in high-grade GEP-NEN and thereby pave the way for a better understanding of the molecular mechanisms and genetic origin of these tumours as well as why these cancers are so aggressive. Importantly, we reveal a high fraction of targetable alterations in HG GEP-NEN patients, pointing to novel treatment strategies applying tailored therapies.

Materials and methods

Study design

The goal of this study was to perform an extensive molecular characterization of HG GEP-NEN and thereby to provide a basis for improved diagnostic accuracy, prognosis estimation and development of possible new treatment strategies. For this purpose, we applied massive parallel sequencing (NGS) with subsequent assessments of genetic alterations, in a large biobank of HG GEP-NEN samples.

Patients and samples

The samples were from patients diagnosed with HG GEP-NEN during 2013–2017 that had been prospectively included in a Nordic registry. Inclusion criteria were histopathologically confirmed high-grade neuroendocrine neoplasm (Ki-67 > 20%) with gastroenteropancreatic primary or unknown primary site (CUP) with predominantly gastrointestinal metastases (defined by radiological CT scans). Clinical information, tumour tissue and a whole blood sample for normal tissue analyses were collected for each case. Thus, 181 cases were finally included for the present analyses (see Supplementary Methods for details, see section on supplementary materials given at the end of this article). Histological sections (HE, CgA, synaptophysin, Ki-67) were collected, digitalized and subjected to a centralized pathological re-evaluation (A P) for validation of HG NEN diagnosis, WHO 2019 classification, cell-type and Ki-67 recount. Thereafter, an additional blinded pathology review was done by three pathologists (A P, A C and I M B L) for all cases (n = 68) meeting the following criteria: NET G3 or non-small cell NEC with a Ki-67 ≤ 55% or uncertain morphology (n = 9), since these are the cases where pathology assessment separating NET G3 from NEC is important. Difficult cases were finally discussed during a virtual consensus meeting. Among the 181 cases, 152 were classified as NEC and 29 as NET G3, reflecting an expected distribution between NEC and NET G3.

Tissue collection and isolation of DNA

For tumour samples, tissue cores from areas with high tumour cell content were collected, and DNA was isolated using ultrasonication and subsequent column-based binding and elution (Supplementary Methods). Genomic DNA from normal tissue (blood) was isolated using QIAamp DNA MiniKit (Qiagen). MSI status was determined using the Promega MSI analysis system (Version1.2, Promega).

Library preparation and sequencing

Subsequent to DNA quality controls (Supplementary Methods), targeted massive parallel sequencing was performed on DNA from FFPE tumour tissue and from matched normal peripheral blood DNA. Illumina libraries were prepared applying Kapa Hyper Prep kit (Kapa Biosystem) and Agilent SureSelect XT-kit (Agilent). Targeted enrichment was performed using RNA baits (SureSelect, Agilent), targeted against an in-house panel of 360 cancer-related genes (Yates et al. 2015). Libraries were sequenced on a MiSeq instrument (Illumina) to an average depth of 131× (range, 75×–254×) for the tumours and 165× (range, 50×-272×) for normal blood.

Data processing and bioinformatics analysis

Raw sequence data were aligned to the human reference genome (Build-UCSC hg19) using BWA (Li & Durbin 2009). Somatic substitutions and insertions/deletions were detected using CaVEMan and Pindel, respectively (Raine et al. 2015, Jones et al. 2016). Somatic mutations were validated by manual inspection in Integrative Genomics Viewer and the COSMIC database. Mutations were restricted to those affecting protein-coding regions. In order to provide a complete overview of the mutations in the 360 genes in GEP-NEN, the data set was not restricted to driver mutations. Allele-specific copy number analysis and estimation of purity and ploidy were performed using FACETS (Shen & Seshan 2016). GISTIC 2.0 (Mermel et al. 2011) was used to identify frequent amplifications and deletions. Targetable molecular alterations were identified based on a predefined list and, in addition, by application of the OncoKB database (Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Table 1). A prediction model for the classification of tumours into the categories LC-NEC or NET G3 was built, based on mutational status of nine genes (APC, ATRX, BRAF, DAXX, KRAS, MEN1, MYO5B, SMAD2 and TP53). Classification was performed using C5.0 decision tree algorithm implemented in R package C50 (v0.1.2; Supplementary files 1, 2 and 3) (https://www.rulequest.com/).

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using R software (v3.5.1). Differences in mutation frequency between groups were assessed by odds ratio estimates with 95% CIs and by Fischer's exact test. Overall survival was assessed from the date of diagnosis to the date of death or last follow-up. Survival curves were drawn by the Kaplan–Meier method, and differences within groups were assessed by log-rank tests. P -values are given as two-sided, and P -values < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

From the Nordic GEP Registry biobank (see Supplementary Methods), samples with macroscopically sufficient tumour tissue to perform NGS (n = 279) were identified. Cases lacking normal tissue (n = 56), lacking slides for re-evaluation (n = 2) or reassessed as NET G2 (n = 1), adenocarcinoma (n = 14), mixed neuroendocrine neoplasms (MiNEN; n = 23) or ambiguous neuroendocrine morphology concerning differentiation (n = 11) were excluded, resulting in a preliminary sample set of n = 172. In the second, blinded, pathological review of 68 cases (59 out of the 172 cases with an initial NET/NEC separation and 9 out of the 11 uncertain), based on consensus between the three pathologists, four cases were reclassified (2 NEC cases were re-classified to NET G3 and 2 NET G3 were reclassified to NEC). In addition, five cases were re-classified from large cell to small cell, and two cases were re-classified from small cell to large cell. All nine cases with initial uncertain morphology were now re-classified as NET G3 or NEC. Thus, 181 patients were included for analyses. Among these were 152 neuroendocrine carcinomas (NEC) and 29 neuroendocrine tumours (NET G3), reflecting an expected distribution between NEC and NET G3.

A majority (67.4%) of samples were collected by biopsy, while the remaining specimens were collected by resection. Eighty per cent were stage IV, while 20% were stages I–III. The most frequent sites of primary tumour were the colon, rectum, esophagus, gastric and pancreas. Out of 25 cases with unknown primary, 22 had liver metastases and 5 of these had additional lung metastases, 8 bone metastases and no cases of brain metastasis. The three cases without liver metastases had only intra-abdominal lymph node metastases. Details of the basic patient characteristics are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

| Characteristic | Subgroup | Total NEN (n = 181, %) | NEC (n = 152, %) | NETG3 (n = 29, %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| <50 | 13 (7) | 9 (5.9) | 4 (13.8) | |

| 50–59 | 20 (11.6) | 18 (11.8) | 2 (6.9) | |

| 60–69 | 64 (35.4) | 55 (36.2) | 9 (31) | |

| 70+ | 84 (46.4) | 70 (46.1) | 14 (48.3) | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 109 (60.2) | 94 (61.8) | 15 (51.7) | |

| Female | 72 (39.8) | 58 (38.2) | 14 (48.3) | |

| Site | ||||

| Right colon | 38 (21) | 36 (23.7) | 2 (6.9) | |

| Rectum | 37 (20.4) | 36 (23.7) | 1 (3.4) | |

| Esophagus | 19 (10.5) | 18 (11.8) | 1 (3.4) | |

| Gastric | 17 (9.4) | 16 (10.5) | 1 (3.4) | |

| Unknown | 25 (13.8) | 19 (12.5) | 6 (20.7) | |

| Pancreas | 25 (13.8) | 13 (8.6) | 12 (41.4) | |

| Left colon | 10 (5.5) | 9 (5.9) | 1 (3.4) | |

| Gallbladder/duct | 3 (1.7) | 3 (2) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Other | 3 (1.7) | 2 (1.3) | 1 (3.4) | |

| Small bowel | 4 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (13.8) | |

| Cell type | ||||

| Large cell | 87 (57.2) | |||

| Small cell | 65 (42.8) | |||

| Ki-67 | ||||

| 21–55% | 36 (19.9) | 13 (8.6) | 23 (79.3) | |

| >55% | 132 (72.9) | 130 (85.5) | 2 (6.9) | |

| >20% (exact value not specified) | 13 (7.2) | 9 (5.9) | 4 (13.8) | |

| Surgery of primary tumour | ||||

| Resected (prior to sampling) | 59 (32.6) | 50 (32.9) | 9 (31) | |

| Not resected | 122 (67.4) | 102 (67.1) | 20 (69) | |

| Disease | ||||

| Non-metastatic (stage I–III) | 36 (19.9) | 31 (20.4) | 5 (17.2) | |

| Metastatic (stage IV) | 145 (80.1) | 121 (79.6) | 24 (82.8) | |

| Smoking habit | ||||

| Smoker | 37 (20.4) | 33 (21.7) | 4 (13.8) | |

| Ex-smoker | 54 (29.8) | 45 (29.6) | 9 (31) | |

| Non-smoker | 73 (40.3) | 60 (39.5) | 13 (44.8) | |

| Unknown | 17 (9.4) | 14 (9.2) | 3 (10.3) |

Molecular landscape of GEP-NEC

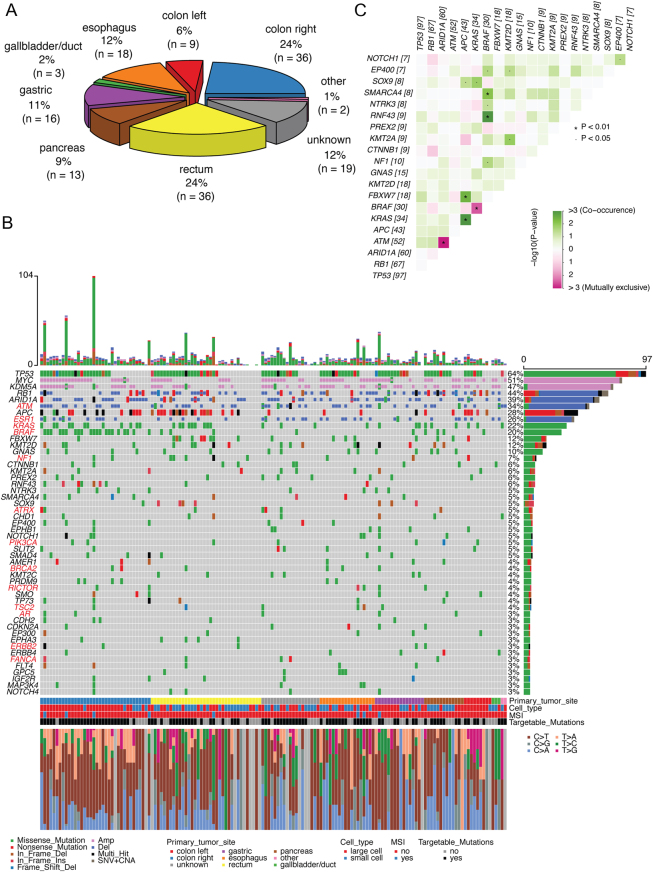

The 152 cases of GEP-NEC included different primary tumour sites (Fig. 1A). Assessing somatic point mutations and small insertions/deletions (indels), the most frequently mutated genes were TP53 (64%), APC (28%), KRAS (22%), BRAF (20%) and RB1 (14%) (Fig. 1B). We found a rather narrow range of other genes (KMT2D, FBXW7, GNAS, ARID1A, NF1 and CTNNB1) harbouring mutations in 6–12% of the patients and a long tail of cancer genes with mutations in <6%.

Figure 1.

(A) Distribution of primary tumour site for the included cases of neuroendocrine carcinomas (NECs) cohort. (B) Oncoplot showing the top 50 most frequently altered genes (rows) among 152 NEC patients (columns). Upper panel shows the mutational burden per sample. Percentages on the right represent mutations frequency per gene. Genes with potentially targetable alterations are highlighted in red font (additional targetable mutations were observed among genes less frequently altered. The plot shows both potentially targetable and non-targetable alterations for these genes; for example, deletions of ESR1 and non-V600E mutations of BRAF are not considered as targetable). The panel under the oncoplot area is composed of four single row heatmaps showing in order, from top to bottom, primary tumour site, cell type, MSI status and presence of one or more potentially targetable mutation. Stacked barplot (at the bottom) shows the fraction of nucleotide changes in each sample. 'Multi_hit' indicates that more than one mutation occurs in the same gene, in the same patient. (C) Co-occurrence and mutual exclusiveness of mutations in NEC patients. Co-occurring mutations are indicated by green squares and mutually exclusive mutations between gene pairs in purple. The color intensity is proportionate to the –log10 (P -value). P -values were determined using Fisher’s exact test.

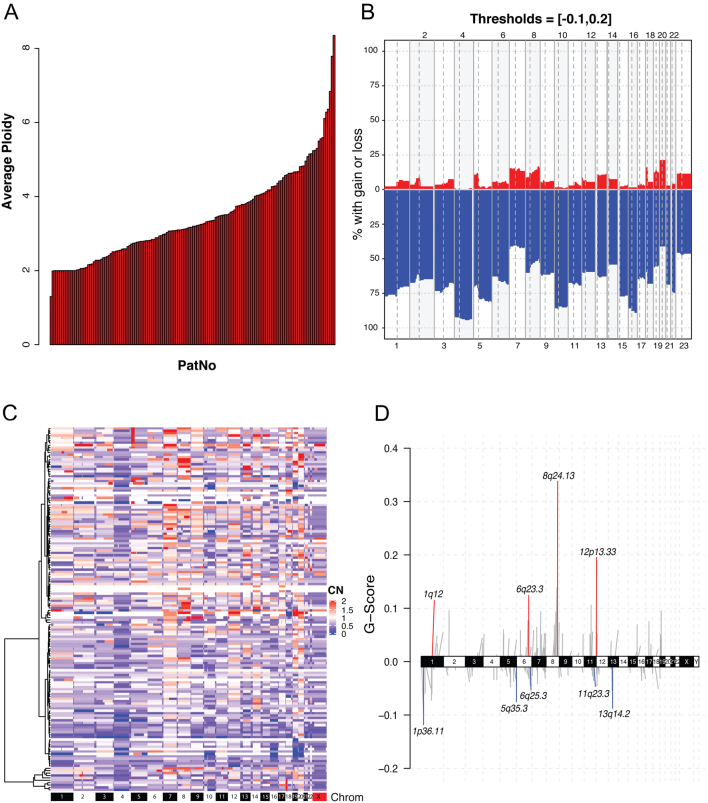

The average ploidy in the analysed NECs was 3.44, indicating that a large fraction had undergone whole-genome duplication (WGD; Fig. 2A). The vast majority of copy number alterations (CNA) were deletions/copy number losses, presumably events occurring after WGD (Fig. 2B, C and D). The most frequently deleted chromosomal regions were 1p36.11 containing ARID1A (35%), 6q25.3 containing ESR1 (25%), 11q23.3 containing ATM (31%) and 13q14.2 containing RB1 (34%). The most frequently gained/amplified regions were 8q24.13 containing MYC (51%) and 12p13.33 containing KDM5A (45%) (Fig. 1B).

Figure 2.

(A) Stacked barplot illustrating the average ploidy in each of the NEC samples. (B) Frequency of copy number aberrations in the NEC cohort (n = 152). Y-axis indicates the fraction of patients with copy number losses (blue) and gains (red) across the genome. Chromosome numbers are indicated on the x-axis. Chromosomes and chromosome arms are separated by vertical lines. (C) Heatmap representing the copy number alterations for each segment, relative to average genome ploidy for each sample. Unsupervised hierarchical clustering of patients on the y-axis and chromosomes on the x-axis. (D) Significant copy-number gains (red) and losses (blue) identified by two-sided hypothesis testing using GISTIC2.0, corrected for multiple hypothesis testing. Significant regions (chromosome locus and focal copy number changes) for known cancer-associated genes are labeled.

We found a high co-occurrence of mutations in APC and KRAS (P = 4.3 × 10−8; Fig. 1C). APC mutations also co-occurred with FBXW7 mutations (P = 3.6 × 10−3). BRAF mutations co-occurred with both mutations in RNF43 and SMARCA4 (P = 1.7 × 10−4 and 8 × 10−3), while being mutually exclusive to KRAS mutations (P = 3.2 × 10−3). ATM deletions were mutually exclusive to ARID1A deletions (P = 8.9 × 10−4). Several known pathways were affected by alterations in >20% of the cohort, including DNA damage response, Wnt/beta-catenin, RAS GTPase, ERK signalling, receptor tyrosine kinase upstream of RAS and Notch signalling (Supplementary Fig. 1). Regarding proliferation phenotype, despite the small number of NEC with Ki-67 21–55% (n = 13) compared to NEC with Ki-67 > 55% (n = 130), CNA in MYC was the only significant difference (enrichment) seen in NEC with Ki-67 21–55% (P = 0.018; Supplementary Fig. 2). CNA in ARID1A and mutations in FBXW7 were significantly enriched among non-smokers as compared to smokers (P < 0.05; Supplementary Fig. 3).

On average, the number of mutations within the targeted gene panel was 7.7 (range, 0–104), corresponding to a tumour mutation burden (TMB) of 5.1 per MB (range, 0–69; Supplementary Table 2).

Importantly, we assessed the fraction of NEC samples harbouring molecular alterations that could potentially be targetable, based on a predefined list of SNVs and CNAs (see Methods; Supplementary Table 1). Among the 152 samples, we found 101 (66%) with one or more alterations that could be targeted by available drugs. The majority of these alterations were related to defects in DNA repair, making tumours potentially sensitive to PARP inhibition, but frequent targetable alterations were also seen in BRAF, MTOR signalling as well as several other genes (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 1). In addition to the analysis of potentially targetable mutations, we performed a highly stringent assessment of those alterations listed as established biomarkers in the OncoKB database. Even in this restricted analysis, as many as 22% of the tumours harboured one or more targetable alterations.

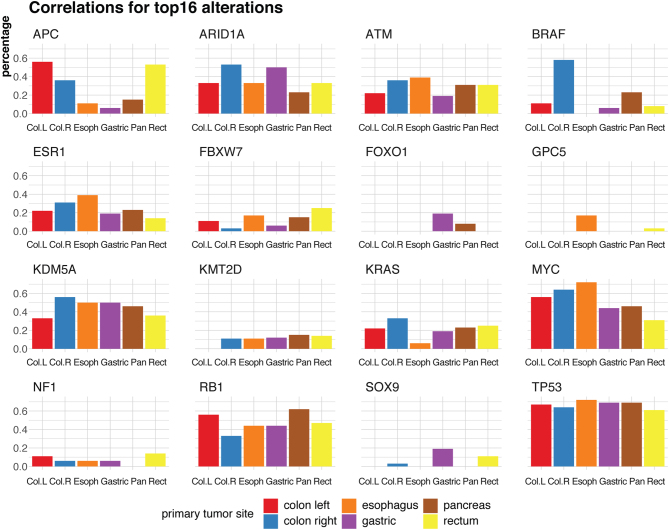

Specific molecular features of GEP-NEC according to primary tumour site

The frequency of genetic alterations varied according to primary NEC tumour site (Fig. 3). In colonic primaries (n = 45), mutations were frequent in TP53 (64%), BRAF (49%), APC (40%) and KRAS (31%) (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 4A). Regarding CNA, we found loss of ARID1A (42%), RB1 (24%), ATM (33%) and ESR1 (27%), while amplification was found for KDM5A (49%) and MYC (62%). BRAF was mutually exclusive to KRAS and APC mutations (P = 6.8 × 10−6 and 4.6 × 10−6, respectively), while the two latter were significantly co-occurring (P = 1.4 × 10−6; Supplementary Fig. 4B).

Figure 3.

Barplots indicating mutation frequency for the top 16 frequently altered genes in NEC patients, stratified for the six primary tumour sites (left colon, right colon, esophagus, gastric, pancreas, rectum). Y-axis shows the frequency (in percentage) of the alteration for each site.

In rectal primaries (n = 36), we found mutations in TP53 (61%), APC (53%), FBXW7 (25%) and KRAS (25%) (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 5A). Gene alterations in the range of 8–14% were limited to KMT2D, NF1, EPHA3, SOX9 and BRAF. Regarding CNA, we found loss of RB1 (39%), ARID1A (25%), ATM (28%) and ESR1 (14%), while amplifications were seen for KDM5A (33%) and MYC (31%). Mutations of APC and KRAS both co-occurred with TP53 mutations (P = 5 × 10−3 and P = 6 × 10−3; Supplementary Fig. 5B). Thus, the frequency of alterations in different genes was fairly similar comparing colonic and rectal origin, with the exception of BRAF mutations, which were significantly more frequent in colonic NEC (P = 8.0 × 10−5; Fig. 3).

Among the remaining tumours, the most frequently altered genes in gastric NEC (n = 16) were TP53 (69%), ARID1A (50%), RB1 (44%) and KDM5A (50%). Among genes that were not frequently mutated in other primary sites, three patients had FOXO1 mutations (19%) and three SOX9 mutations (19%). In oesophageal NEC (n = 18) TP53 was mutated in 72%, and MYC amplified in 72%. Nine of 13 pancreatic NEC had TP53 mutations (69%), 8 had RB1 mutations and/or deletions (62%). BRAF and KRAS were each mutated in three patients (23%; Supplementary Figs 6, 7 and 8). Thus, we found some primary tumour site-specific molecular differences. BRAF mutations were most common in colorectal primaries compared to other sites (P = 2.9 × 10−8).

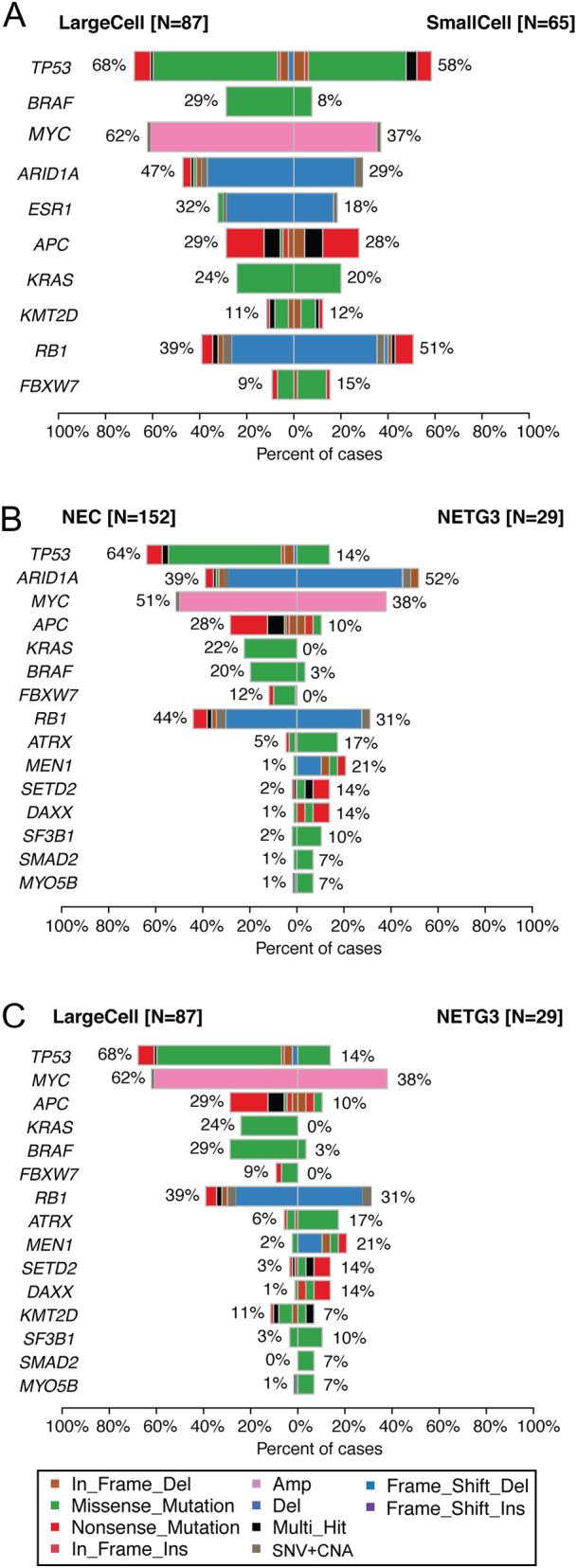

Large cell and small cell GEP-NEC

Comparing large cell (LC)-NEC to small cell (SC)-NEC, we found alterations in BRAF, MYC and ARID1A to be significantly enriched among LC-NEC (Fig. 4A and Supplementary Figs 9, 10, 11). Mutations in the MAP3K1 gene were somewhat enriched in SC-NEC.

Figure 4.

Co-bar plots illustrating the differences in mutation frequencies for the most frequently mutated genes, between (A) large cell NEC (n = 87) vs small cell NEC (n = 65), (B) NEC (n = 152) vs NET G3 (n = 29) and (C) large cell NEC (n = 87) vs NET G3 (n = 29).

GEP NET G3

Among 29 NET G3, we found ARID1A copy number loss in 14 cases (48%) (Supplementary Fig. 12). Other frequently altered genes were ATM (n = 14; 48%), ESR1 (n = 11; 38%), KDM5A (15; 52%), MYC (11; 38%), RB1 (9; 31%), MEN1 (6; 21%) and ATRX (5; 17%). In the subset of pancreatic NET G3 (n = 12), we found mutations in MEN1 (n = 4), TP53 (n = 3), DAXX (n = 3) and ATRX (n = 3; Supplementary Fig. 12).

On average, the number of mutations in NET G3 was 6.9 (range, 0–89), corresponding to a tumour mutation burden (TMB) of 4.6 per MB (range, 0–59; Supplementary Table 2).

Out of the 29 NET G3 samples, we found 21 (72%) to harbour one or more potentially targetable alterations (Supplementary Table 1).

Molecular differences between NEC and NET G3

We observed a numerical, but nonsignificant, difference in the number of genetic alterations among NEC as compared to NET G3 (average: 9.9 vs 9.4, P > 0.05; Supplementary Table 2). However, we found alterations in several genes to be significantly skewed between the two groups (Fig. 4B and Supplementary Fig. 13). Mutations in TP53 and KRAS were significantly enriched among NEC (P = 7.0 × 10−7 and 0.003). Mutations in APC, BRAF and FBXW7 were also enriched in NEC, although not statistically significant. Alterations in MEN1, DAXX, SETD2 and ATRX were significantly enriched in NET G3. Given that SC carcinoma per definition is NEC, the subgroups important to distinguish are LC-NEC from NET G3. We therefore restricted our analyses to genes differentially altered between the two latter groups. Alterations in TP53, BRAF, MYC and KRAS were significantly enriched among LC-NEC (Fig. 4C and Supplementary Fig. 14). MEN1 and DAXX mutations were significantly enriched in NET G3.

Testing whether molecular alterations of LC-NEC could be a classifier to distinguish them from NET G3, we found 72/87 LC-NEC having mutations in APC, TP53, KRAS or BRAF as compared to 6/29 NET G3 (P = 2.3 × 10−9). This crude four-gene classifier yields 92.3% sensitivity, 60.5% specificity and a positive predictive value of 82.8% for distinguishing LC-NEC from NET G3. We also applied a more refined approach, including genes enriched for mutations either in LC-NEC or NET G3 and built a prediction model based on decision tree classification (https://www.rulequest.com/). Although the model must be interpreted with caution since no validation sample set was available, applying the mutation distribution of the nine genes (APC, TP53, KRAS, BRAF, ATRX, DAXX, MEN1, MYOB5B andSMAD2), we generated a classifier yielding 86.8% sensitivity, 88.9% specificity and a positive predictive value of 96.0% (Supplementary files 1, 2 and 3).

Microsatellite instability (MSI) in GEP-NEC

MSI was seen in 8/152 GEP-NEC (5.3%) and in only 1 of 29 NET G3 (3.4%). We found a slight MSI enrichment in colonic GEP-NEC: four colonic primaries displayed MSI (8.9% of colon cases) while two were oesophageal, one rectal and one gastric (Fig. 1B). In line with previous findings in colorectal adenocarcinoma (Aasebo et al. 2019), we found MSI to co-occur with BRAF mutations in colorectal NEC (4/4 MSI harboured BRAF mutation). Also, as expected, the eight tumours with MSI were the ones with the highest number of mutations among the NEC cases (Fig. 1B).

Prognosis

Overall survival (OS) for GEP-NEC patients was significantly worse than for NET G3 patients (11 vs 18 months; P = 0.049; Supplementary Fig. 15). Within the NEC group, patients with SC-NEC had a significantly worse OS than those with LC-NEC (9 vs 12 months; P = 0.025; Supplementary Fig. 15). Although trends for the prognostic value of key features such as MSI and TMB were observed, these did not reach statistical significance in the present data set. Neither did mutation status for any of the investigated single genes (in univariate analyses).

Discussion

Based on morphological similarities with small-cell lung cancer (SCLC), SCLC chemotherapy schedules are used both in the adjuvant and in metastatic setting for GEP-NEC. Thus, platinum/etoposide chemotherapy is the cornerstone in adjuvant and palliative treatment of GEP-NEC (Strosberg et al. 2010, Garcia-Carbonero et al. 2016, Pavel et al. 2020), although the benefit of adjuvant therapy for GEP-NEC has never been proven and as many as 1/3 of metastatic patients have immediate disease progression on such treatment, and in general, PFS and OS are short (Sorbye et al. 2013, Garcia-Carbonero et al. 2016, Sorbye et al. 2019). A confirmation of similar molecular patterns in GEP-NEC and SCLC would support the current treatment extrapolation. However, our data show that this is not the case. In SCLC, TP53 mutations are reported in 86–93% and RB1 mutations in 40–62% (Peifer et al. 2012, Dowlati et al. 2016, Miyoshi et al. 2017, Eskander et al. 2020) while biallelic inactivation of TP53 and RB1 (by any mechanism) is a universal finding for all SCLC (George et al. 2015). The 2019 WHO classification for digestive tumours state that GEP-NEC frequently have TP53 and RB1 mutations (WHO 2019). Until recently, only small series have reported TP53 and RB1 alterations in GEP-NEC, and reports are methodologically inconsistent as some studies report gene mutations, others genetic alterations in general and some altered protein levels by immunohistochemistry. TP53 mutations in GEP-NEC are found in 57–59% (Vijayvergia et al. 2016, Busico et al. 2020), in colorectal NEC in 50–84% (Shamir et al. 2019, Capdevila et al. 2020) and in 8/12 pancreatic NEC (Konukiewitz et al. 2018). We found TP53 mutations in 64% of GEP-NEC, 68% in large-cell and 58% in small-cell, which are substantially fewer than observed in SCLC. We found RB1 mutations in only 14% of cases, strikingly less than observed in both SCLC and LCLC. However, we did find a substantial fraction of cases with copy number loss of the RB1 locus, and as such, RB1 alterations were observed in 34% of our cases. These results could indicate a lower mutation frequency of both TP53 and RB1 in GEP-NEC than in SCLC/LCLC. It is important to note that some previous studies finding high frequencies of RB1 inactivation have based their 'mutation calling' on lacking pRb staining by IHC. Copy number losses or epigenetic silencing, in addition to mutations, are likely to have caused such a lack of protein expression in many cases. Overall, our results clearly indicate that RB1 mutations are relatively rare in GEP-NEC, whereas copy number losses are more frequent. We argue that this should be specified in future efforts to establish classification guidelines. Comparing our findings to LCLC, another major difference was STK11 and KEAP1 alterations. In LCLC, 33% STK11 and 29% KEAP1 mutations are observed (Rekhtman et al. 2016), whereas we found STK11 mutations in only two LC-NEC (2.3%) and KEAP1 mutations in three (3.4%). KRAS mutations have been reported in 4–22% of LCLC (Rekhtman et al. 2016, Miyoshi et al. 2017), whereas BRAF mutations are rare; 0–3% in LCLC (Miyoshi et al. 2017, George et al. 2018) and 1/110 SCLC-cases (George et al. 2015). We found KRAS and BRAF mutations in 22% and 20% of GEP-NEC, respectively.

Although we estimated tumour mutation burden from a targeted panel of 360 genes, such estimates have been shown to strongly reflect the burden detected in larger-scale sequencing (Chalmers et al. 2017). The limited mutation burden (median 5.1 per MB) we observed in GEP-NEC is in contrast to pulmonary NEC and may explain the limited benefit of checkpoint inhibitors.

Taken together, based on these molecular differences, we believe that one must be careful when basing treatment decisions for GEP-NEC on results from pulmonary NEC (SCLC/LCLC). We argue that other treatment strategies should be exploited in GEP-NEC. Strategies using adenocarcinoma schedules may be an option, but most importantly, our results show that as many as 66% of GEP-NEC cases have potentially targetable molecular alterations. This is above the pan-cancer average (57%), reported by Bailey et al. (2018). Although the analyses are not directly comparable, our data at least indicate that the fraction of targetable mutations is higher in GEP-NEC than most cancers. Considering the very limited results of first and second line chemotherapy for GEP-NEC (Sorbye et al. 2013, 2019, Garcia-Carbonero et al. 2016), the possibility to apply targeted therapy in GEP-NEC thus seems to be a major possibility to improve the very poor prognosis of these patients. Extrapolation from SCLC has also been a common practice for the treatment of all extrapulmonary neuroendocrine carcinomas, but a recent report shows major genetic differences between SCLC and neuroendocrine cervical carcinoma (HGNECC), further questioning such a general extrapolation (Eskander et al. 2020). The HGNECC genetics are also different compared to our GEP-NEC findings, illustrating that extrapulmonary NEC should not be assessed as a joint group but rather according to primary tumour site.

In contrast to the large molecular differences reported between SCLC and LCLC, we only found some differences between small cell and large cell GEP-NEC; especially more frequent BRAF mutations in colonic large-cell NEC were observed. How these results could affect the clinical practice of treating small-cell and large-cell GEP-NEC similarly (Strosberg et al. 2010, Garcia-Carbonero et al. 2016) needs to be studied further. In a previous study (Busico et al. 2020), molecular differences within NEC were found according to the proliferation rate. In our present data, we only found minor differences between tumour with high vs low Ki-67. In contrast to the many genetic differences seen between smokers and nonsmokers in lung cancer (Chapman et al. 2016, Smolle & Pichler 2019), only minor differences were found between these groups in our study illustrating that GEP-NEC is a specific entity.

In our study, molecular alterations varied in some aspects between the different primary tumour sites. TP53 mutations were quite similarly distributed in all primary sites. RB1 alterations were especially seen in pancreatic (62%) and left colonic (56%), and less in right colonic NEC. Prior studies have shown the loss of pRb protein expression in 67–80% of GEP-NEC (Li et al. 2008, Busico et al. 2020), 33–55% of pancreatic NEC (Hijioka et al. 2017, Konukiewitz et al. 2018) and 56% of colorectal (CR)-NEC (Takizawa et al. 2015). In our study, right-sided colon NEC was the only primary tumour site with a high number of BRAF V600E (70%) mutations. BRAF V600E mutations were reported in prior colorectal NEC/MINEN series in a frequency of 28–47% (Dizdar et al. 2019, Capdevila et al. 2020). The combination of a BRAF and EGFR inhibitor was recently approved for metastatic colorectal adenocarcinoma (Van Cutsem et al. 2019), and case reports have shown the benefit of such treatment in CR-NEC (Klempner et al. 2016). Our results also illustrate the possible importance of sidedness in CR-NEC, as shown for CR adenocarcinoma (Tejpar et al. 2017). We found KRAS mutations at all sites at an incidence of 19–33%, less among oesophageal primaries. This is partly in line with previous studies revealing KRAS mutations in gastric (6%), pancreatic (49%) and colonic (48%) NEC/MINEN (Sahnane et al. 2015, Hijioka et al. 2017, Capdevila et al. 2020). A recent study reported that EGFR blockade reverts resistance to KRAS G12C inhibition in colorectal adenocarcinoma (Amodio et al. 2020). However, we only found five KRAS G12C mutations in our study.

Recently, a large study compared genetic differences between gastrointestinal and pancreatic NEN and between low-grade and high-grade GEP-NEN (Puccini et al. 2020). One hundred and thirty-five HG tumours showed mutations in TP53 (51%), KRAS (30%), RB1 (11%) and BRAF (5%). The authors concluded that RB1 and TP53 mutations are frequent in HG GEP-NEN. Compared to NET this is correct, however, their results confirm our result that RB1 mutations are much rarer in GEP-NEC compared to SCLC. In contrast to our study, this study neither included pathological re-evaluation regarding the separation of NET G3 from NEC nor filtered for germline variants. The low BRAF mutation frequency compared to our present data may be due to fewer colon NECs; however, primary sites were not specified. In our study, we found MSI in eight NEC cases (5.3%). In prior studies, the frequency of MSI in GEP-NEC/MINEN is reported to be 0–15% (La Rosa et al. 2012, Sahnane et al. 2015, Chapman et al. 2016, Puccini et al. 2020). MSI seems to be an agnostic tumour marker for the benefit of checkpoint inhibitors (Petrelli et al. 2020), and at least CR-NEC should be tested for MSI with the potential to guide treatment choice.

In our HG GEP-NEN cohort, we found a NET G3 incidence of 16%, in accordance with the 10–18% observed in prior studies (Heetfeld et al. 2015, Sorbye et al. 2019, Elvebakken et al. 2021). In NET G3, which is most frequently occurring in the pancreas (Coriat et al. 2016), most alterations were also seen in pancreatic primaries, including mutations in MEN1 (33%), ATRX (25%) and DAXX (25%; within the subgroup of pancreatic NET G3). This is roughly in line with a previous study of 20 pancreatic NET G3 where 3 ATRX and 7 DAXX mutations were found (Tang et al. 2016a). Although the number of cases is low, these results seem similar to pancreatic NET G1-G2 where relative frequencies of genetic alterations were reported as follows: MEN1 (24–44%), DAXX (11–25%) and (ATRX 16–33%) (Jiao et al. 2011, Chan et al. 2018, Puccini et al. 2020). We found fewer alterations in NET G3 compared to NEC. TP53 was mutated in 14% of the NET G3 cases and 31% had RB1 alterations, while no KRAS mutations were found. Notably, only one NET G3 sample was found to be MSI-positive. There are few other studies on molecular alterations in NET G3. In a study on 15 GEP-NET G3, absent pRB staining was seen in 9/15 cases (60%), whereas only 3 genomic alterations were found (in ATM, VHL and IDH1) (Busico et al. 2020). In a study of 21 pancreatic NET G3, neither abnormal pRb expression nor KRAS mutations were found (Hijioka et al. 2017). A third study reported 1 single TP53 mutation among 11 pancreatic NET G3 (Konukiewitz et al. 2018). These results strongly support that GEP-NEC and NET G3 are different diseases and that the clear separation of these entities is important. Treatment used for GEP-NEC should probably not be used for NET G3 patients without careful consideration. The molecular differences could in part explain why NET G3 patients have less response to platinum-based chemotherapy than NEC (Sorbye et al. 2019).

Separation of NET G3 from NEC based on morphology can be challenging. Some have suggested to use MEN1/ATRX/DAXX and RB1/TP53 to aid in separation of these entities (Tang et al. 2016a). The ESMO 2020 GEP-NEN guidelines suggest using RB1 mutations or RB1 loss to discriminate between NET G3 and NEC (Pavel et al. 2020). Our data highlight that testing for RB1 loss would perform better than RB1 mutations in such an approach. Applying molecular data, we assessed the main differences between NEC and NET G3. Given that SC tumours per definition are NEC, we considered the subgroups that are clinically important to distinguish to be LC-NEC from NET G3. Mutations in APC, TP53, KRAS and BRAF were enriched in LC-NEC as compared to NET G3, and the mutation status of these genes yielded a classifier with surprisingly high sensitivity, specificity and positive predictive value. Applying a more refined prediction model including nine genes, we found even better prediction scores. Notably, these models must be interpreted with caution, since we currently do not have an independent data set for validation analyses. However, these calculations indicate a possibility to apply molecular data for the classification of cases.

An important strength of our study is that scans (haematoxylin and eosin, synaptophysin, chromogranin-A and Ki-67-stain) of all NEN were centrally reevaluated histologically according to the most recent 2019 WHO classification. Furthermore, for all patients, we had available DNA from the blood, enabling proper filtering of genetic variants to identify true somatic alterations. In contrast to many prior studies, we excluded MiNEN, avoiding possible inclusion of the adenocarcinoma part in the DNA extraction. We did not include other extrapulmonary NEC and as such, ensured a relatively homogeneous sample of GEP-NEC.

Regarding limitations, our cohort includes the largest number of cases reported to date, but a large fraction of cases were colon (24%) and rectal (24%) primaries, resulting in other subgroups with limited representation. Thus, it may be that even larger sets of samples are needed to get the full overview of the mutational landscape of each individual subgroup. Further, it is important to note that the sample set may have a bias in terms of the patient population. About one-third of patients in the present sample set had undergone primary tumour surgery, a much debated, but possible prognostic factor (Sorbye et al. 2015). Further, although our panel of 360 genes cover the most relevant cancer genes, it is clear that a more comprehensive overview of the mutational landscape, including structural rearrangement etc., would have been obtained by whole-genome sequencing and such detailed analyses are warranted for future.

In summary, we performed a comprehensive assessment of the molecular tumour alterations in a large series of gastroenteropancreatic high-grade neuroendocrine neoplasms. We found a marked difference in the molecular profile compared to prior results in SCLC and LCLC, some differences comparing large-cell and small-cell GEP-NEC, a profile variation according to primary tumour site, a high fraction GEP-NEC with targetable mutations pointing to novel important therapeutic strategies and a possible molecular strategy to separate NEC from NET G3.

Supplementary Material

Declaration of interest

H E has received honoraria from Bayer. G O H has received grants or honoraria from Ipsen Amgen, BMS, MSD, Roche and Bayer. S K has received grants or honoraria from Astra-Zeneca, Pfizer, Pierre-Fabre, Novartis, Sobi, Amgen, Sanofi Aventis and Roche. H S has received research support from Novartis, Amgen, Ipsen and honoraria from Novartis, Ipsen, Pfizer, Keocyt, AstraZeneca, BMS, Roche, Amgen, Merck, Shire, Hutchinson and Celgene.

Funding

This work was supported by Novartis; Ipsen; the Liaison Committee between the Central Norway Regional Health Authority and the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU).

Ethics

The work protocol was approved by ethics committees in Norway, Sweden and Denmark (Supplementary Methods). All patients signed informed written consent.

Author contribution statement

H Sorbye and S Knappskog: shared last authorship.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Beryl Leirvaag and Dagfinn Ekse for technical assistance and Randi Eikeland for data managing. Parts of the work have been performed in the Mohn Cancer Research Laboratory.

References

- Aasebo KØ, Dragomir A, Sundstrom M, Mezheyeuski A, Edqvist PH, Eide GE, Ponten F, Pfeiffer P, Glimelius B, Sorbye H.2019Consequences of a high incidence of microsatellite instability and BRAF-mutated tumors: a population-based cohort of metastatic colorectal cancer patients. Cancer Medicine 83623–3635. ( 10.1002/cam4.2205) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amodio V, Yaeger R, Arcella P, Cancelliere C, Lamba S, Lorenzato A, Arena S, Montone M, Mussolin B, Bian Yet al. 2020EGFR blockade reverts resistance to KRAS(G12C) inhibition in colorectal cancer. Cancer Discovery 101129–1139. ( 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-0187) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey MH, Tokheim C, Porta-Pardo E, Sengupta S, Bertrand D, Weerasinghe A, Colaprico A, Wendl MC, Kim J, Reardon Bet al. 2018Comprehensive characterization of cancer driver genes and mutations. Cell 1741034–1035. ( 10.1016/j.cell.2018.07.034) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan SM, Gregory DL, Stillie A, Herschtal A, Mac Manus M, Ball DL.2010Should extrapulmonary small cell cancer be managed like small cell lung cancer? Cancer 116888–895. ( 10.1002/cncr.24858) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busico A, Maisonneuve P, Prinzi N, Pusceddu S, Centonze G, Garzone G, Pellegrinelli A, Giacomelli L, Mangogna A, Paolino Cet al. 2020Gastroenteropancreatic high-grade neuroendocrine neoplasms: histology and molecular analysis, two sides of the same coin. Neuroendocrinology 110616–629. ( 10.1159/000503722) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capdevila J, Arques O, Hernandez Mora JR, Matito J, Caratu G, Mancuso FM, Landolfi S, Barriuso J, Jimenez-Fonseca P, Lopez Lopez Cet al. 2020Epigenetic EGFR gene repression confers sensitivity to therapeutic BRAFV600E blockade in colon neuroendocrine carcinomas. Clinical Cancer Research 26902–909. ( 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-1266) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers ZR, Connelly CF, Fabrizio D, Gay L, Ali SM, Ennis R, Schrock A, Campbell B, Shlien A, Chmielecki Jet al. 2017Analysis of 100,000 human cancer genomes reveals the landscape of tumor mutational burden. Genome Medicine 9 34. ( 10.1186/s13073-017-0424-2) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan CS, Laddha SV, Lewis PW, Koletsky MS, Robzyk K, Da Silva E, Torres PJ, Untch BR, Li J, Bose Pet al. 2018ATRX, DAXX or MEN1 mutant pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors are a distinct alpha-cell signature subgroup. Nature Communications 9 4158. ( 10.1038/s41467-018-06498-2) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman AM, Sun KY, Ruestow P, Cowan DM, Madl AK.2016Lung cancer mutation profile of EGFR, ALK, and KRAS: meta-analysis and comparison of never and ever smokers. Lung Cancer 102122–134. ( 10.1016/j.lungcan.2016.10.010) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coriat R, Walter T, Terris B, Couvelard A, Ruszniewski P.2016Gastroenteropancreatic well-differentiated grade 3 neuroendocrine tumors: review and position statement. Oncologist 211191–1199. ( 10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0476) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasari A, Mehta K, Byers LA, Sorbye H, Yao JC.2018Comparative study of lung and extrapulmonary poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas: a SEER database analysis of 162,983 cases. Cancer 124807–815. ( 10.1002/cncr.31124) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dizdar L, Werner TA, Drusenheimer JC, Mohlendick B, Raba K, Boeck I, Anlauf M, Schott M, Goring W, Esposito Iet al. 2019BRAF(V600E) mutation: a promising target in colorectal neuroendocrine carcinoma. International Journal of Cancer 1441379–1390. ( 10.1002/ijc.31828) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowlati A, Lipka MB, McColl K, Dabir S, Behtaj M, Kresak A, Miron A, Yang M, Sharma N, Fu Pet al. 2016Clinical correlation of extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer genomics. Annals of Oncology 27642–647. ( 10.1093/annonc/mdw005) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elvebakken H, Perren A, Scoazec JY, Tang LH, Federspiel B, Klimstra DS, Vestermark LW, Ali AS, Zlobec I, Myklebust TÅet al. 2021A consensus developed morphological re-evaluation of 196 high-grade gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms and its clinical correlations. Neuroendocrinology 111883–894. ( 10.1159/000511905) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eskander RN, Elvin J, Gay L, Ross JS, Miller VA, Kurzrock R.2020Unique genomic landscape of high-grade neuroendocrine cervical carcinoma: implications for rethinking current treatment paradigms. JCO Precision Oncology 4972–987. ( 10.1200/PO.19.00248) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Carbonero R, Sorbye H, Baudin E, Raymond E, Wiedenmann B, Niederle B, Sedlackova E, Toumpanakis C, Anlauf M, Cwikla JBet al. 2016Enets consensus guidelines for high-grade gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors and neuroendocrine carcinomas. Neuroendocrinology 103186–194. ( 10.1159/000443172) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George J, Lim JS, Jang SJ, Cun Y, Ozretic L, Kong G, Leenders F, Lu X, Fernandez-Cuesta L, Bosco Get al. 2015Comprehensive genomic profiles of small cell lung cancer. Nature 52447–53. ( 10.1038/nature14664) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George J, Walter V, Peifer M, Alexandrov LB, Seidel D, Leenders F, Maas L, Muller C, Dahmen I, Delhomme TMet al. 2018Integrative genomic profiling of large-cell neuroendocrine carcinomas reveals distinct subtypes of high-grade neuroendocrine lung tumors. Nature Communications 9 1048. ( 10.1038/s41467-018-03099-x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heetfeld M, Chougnet CN, Olsen IH, Rinke A, Borbath I, Crespo G, Barriuso J, Pavel M, O’Toole D, Walter Tet al. 2015Characteristics and treatment of patients with G3 gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms. Endocrine-Related Cancer 22657–664. ( 10.1530/ERC-15-0119) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hijioka S, Hosoda W, Matsuo K, Ueno M, Furukawa M, Yoshitomi H, Kobayashi N, Ikeda M, Ito T, Nakamori Set al. 2017Rb loss and KRAS mutation are predictors of the response to platinum-based chemotherapy in pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasm with grade 3: a Japanese multicenter pancreatic NEN-G3 study. Clinical Cancer Research 234625–4632. ( 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-3135) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao Y, Shi C, Edil BH, de Wilde RF, Klimstra DS, Maitra A, Schulick RD, Tang LH, Wolfgang CL, Choti MAet al. 2011DAXX/ATRX, MEN1, and mTOR pathway genes are frequently altered in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Science 3311199–1203. ( 10.1126/science.1200609) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones D, Raine KM, Davies H, Tarpey PS, Butler AP, Teague JW, Nik-Zainal S, Campbell PJ.2016cgpCaVEManWrapper: simple execution of CaVEMan in order to detect somatic single nucleotide variants in NGS data. Current Protocols in Bioinformatics 5615.10.1–15.10.18. ( 10.1002/cpbi.20) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klempner SJ, Gershenhorn B, Tran P, Lee TK, Erlander MG, Gowen K, Schrock AB, Morosini D, Ross JS, Miller VAet al. 2016BRAFV600E mutations in high-grade colorectal neuroendocrine tumors may predict responsiveness to BRAF-MEK combination therapy. Cancer Discovery 6594–600. ( 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-1192) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konukiewitz B, Jesinghaus M, Steiger K, Schlitter AM, Kasajima A, Sipos B, Zamboni G, Weichert W, Pfarr N, Klöppel G.2018Pancreatic neuroendocrine carcinomas reveal a closer relationship to ductal adenocarcinomas than to neuroendocrine tumors G3. Human Pathology 7770–79. ( 10.1016/j.humpath.2018.03.018) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Rosa S, Marando A, Furlan D, Sahnane N, Capella C.2012Colorectal poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas and mixed adenoneuroendocrine carcinomas: insights into the diagnostic immunophenotype, assessment of methylation profile, and search for prognostic markers. American Journal of Surgical Pathology 36601–611. ( 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318242e21c) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Durbin R.2009Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 251754–1760. ( 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li AF, Li AC, Tsay SH, Li WY, Liang WY, Chen JY.2008Alterations in the p16INK4a/cyclin D1/RB pathway in gastrointestinal tract endocrine tumors. American Journal of Clinical Pathology 130535–542. ( 10.1309/TLLVXK9HVA89CHPE) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mermel CH, Schumacher SE, Hill B, Meyerson ML, Beroukhim R, Getz G.2011GISTIC2.0 facilitates sensitive and confident localization of the targets of focal somatic copy-number alteration in human cancers. Genome Biology 12 R41. ( 10.1186/gb-2011-12-4-r41) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyoshi T, Umemura S, Matsumura Y, Mimaki S, Tada S, Makinoshima H, Ishii G, Udagawa H, Matsumoto S, Yoh Ket al. 2017Genomic profiling of large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the lung. Clinical Cancer Research 23757–765. ( 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-0355) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavel M, Öberg K, Falconi M, Krenning E, Sundin A, Perren A, Berruti A.2020Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Annals of Oncology 31844–860. ( 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.03.304) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peifer M, Fernández-Cuesta L, Sos ML, George J, Seidel D, Kasper LH, Plenker D, Leenders F, Sun R, Zander Tet al. 2012Integrative genome analyses identify key somatic driver mutations of small-cell lung cancer. Nature Genetics 441104–1110. ( 10.1038/ng.2396) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrelli F, Ghidini M, Ghidini A, Tomasello G.2020Outcomes following immune checkpoint inhibitor treatment of patients with microsatellite instability-high cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncology 61068–1071. ( 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.1046) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puccini A, Poorman K, Salem ME, Soldato D, Seeber A, Goldberg RM, Shields AF, Xiu J, Battaglin F, Berger MDet al. 2020Comprehensive genomic profiling of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms (GEP-NENs). Clinical Cancer Research 265943–5951. ( 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-1804) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raine KM, Hinton J, Butler AP, Teague JW, Davies H, Tarpey P, Nik-Zainal S, Campbell PJ.2015cgpPindel: identifying somatically acquired insertion and deletion events from paired end sequencing. Current Protocols in Bioinformatics 5215.17.11–15.17.12. ( 10.1002/0471250953.bi1507s52) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rekhtman N, Pietanza MC, Hellmann MD, Naidoo J, Arora A, Won H, Halpenny DF, Wang H, Tian SK, Litvak AMet al. 2016Next-generation sequencing of pulmonary large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma reveals small cell carcinoma-like and non-small cell carcinoma-like subsets. Clinical Cancer Research 223618–3629. ( 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2946) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahnane N, Furlan D, Monti M, Romualdi C, Vanoli A, Vicari E, Solcia E, Capella C, Sessa F, La Rosa S.2015Microsatellite unstable gastrointestinal neuroendocrine carcinomas: a new clinicopathologic entity. Endocrine-Related Cancer 2235–45. ( 10.1530/ERC-14-0410) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamir ER, Devine WP, Pekmezci M, Umetsu SE, Krings G, Federman S, Cho SJ, Saunders TA, Jen KY, Bergsland Eet al. 2019Identification of high-risk human papillomavirus and Rb/E2F pathway genomic alterations in mutually exclusive subsets of colorectal neuroendocrine carcinoma. Modern Pathology 32290–305. ( 10.1038/s41379-018-0131-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen R, Seshan VE.2016FACETS: allele-specific copy number and clonal heterogeneity analysis tool for high-throughput DNA sequencing. Nucleic Acids Research 44 e131. ( 10.1093/nar/gkw520) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smolle E, Pichler M.2019Non-smoking-associated lung cancer: a distinct entity in terms of tumor biology, patient characteristics and impact of hereditary cancer predisposition. Cancers 11204. ( 10.3390/cancers11020204) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorbye H, Welin S, Langer SW, Vestermark LW, Holt N, Osterlund P, Dueland S, Hofsli E, Guren MG, Ohrling Ket al. 2013Predictive and prognostic factors for treatment and survival in 305 patients with advanced gastrointestinal neuroendocrine carcinoma (WHO G3): the Nordic NEC study. Annals of Oncology 24152–160. ( 10.1093/annonc/mds276) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorbye H, Dragomir A, Sundstrom M, Pfeiffer P, Thunberg U, Bergfors M, Aasebo K, Eide GE, Ponten F, Qvortrup Cet al. 2015High BRAF mutation frequency and marked survival differences in subgroups according to KRAS/BRAF mutation status and tumor tissue availability in a prospective population-based metastatic colorectal cancer cohort. PLoS ONE 10 e0131046. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0131046) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorbye H, Baudin E, Borbath I, Caplin M, Chen J, Cwikla JB, Frilling A, Grossman A, Kaltsas G, Scarpa Aet al. 2019Unmet needs in high-grade gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms (WHO G3). Neuroendocrinology 10854–62. ( 10.1159/000493318) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strosberg JR, Coppola D, Klimstra DS, Phan AT, Kulke MH, Wiseman GA, Kvols LK. & North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society (NANETS) 2010The NANETS consensus guidelines for the diagnosis and management of poorly differentiated (high-grade) extrapulmonary neuroendocrine carcinomas. Pancreas 39799–800. ( 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181ebb56f) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takizawa N, Ohishi Y, Hirahashi M, Takahashi S, Nakamura K, Tanaka M, Oki E, Takayanagi R, Oda Y.2015Molecular characteristics of colorectal neuroendocrine carcinoma; similarities with adenocarcinoma rather than neuroendocrine tumor. Human Pathology 461890–1900. ( 10.1016/j.humpath.2015.08.006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang LH, Basturk O, Sue JJ, Klimstra DS.2016aA practical approach to the classification of WHO Grade 3 (G3) well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumor (WD-NET) and poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma (PD-NEC) of the pancreas. American Journal of Surgical Pathology 401192–1202. ( 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000662) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang LH, Untch BR, Reidy DL, O’Reilly E, Dhall D, Jih L, Basturk O, Allen PJ, Klimstra DS.2016bWell-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors with a morphologically apparent high-grade component: a pathway distinct from poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas. Clinical Cancer Research 221011–1017. ( 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-0548) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tejpar S, Stintzing S, Ciardiello F, Tabernero J, Van Cutsem E, Beier F, Esser R, Lenz HJ, Heinemann V.2017Prognostic and predictive relevance of primary tumor location in patients with RAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer: retrospective analyses of the CRYSTAL and FIRE-3 trials. JAMA Oncology 3194–201. ( 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.3797) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Cutsem E, Huijberts S, Grothey A, Yaeger R, Cuyle PJ, Elez E, Fakih M, Montagut C, Peeters M, Yoshino Tet al. 2019Binimetinib, encorafenib, and cetuximab triplet therapy for patients with BRAF V600E-mutant metastatic colorectal cancer: safety lead-in results from the phase III Beacon colorectal cancer study. Journal of Clinical Oncology 371460–1469. ( 10.1200/JCO.18.02459) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijayvergia N, Boland PM, Handorf E, Gustafson KS, Gong Y, Cooper HS, Sheriff F, Astsaturov I, Cohen SJ, Engstrom PF.2016Molecular profiling of neuroendocrine malignancies to identify prognostic and therapeutic markers: a Fox Chase Cancer Center Pilot Study. British Journal of Cancer 115564–570. ( 10.1038/bjc.2016.229) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter T, Tougeron D, Baudin E, Le Malicot K, Lecomte T, Malka D, Hentic O, Manfredi S, Bonnet I, Guimbaud Ret al. 2017Poorly differentiated gastro-entero-pancreatic neuroendocrine carcinomas: are they really heterogeneous? Insights from the FFCD-GTE national cohort. European Journal of Cancer 79158–165. ( 10.1016/j.ejca.2017.04.009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO 2019WHO Classification of Digestive System Tumours, 5th ed.Lyon, France: IARC. [Google Scholar]

- Yachida S, Vakiani E, White CM, Zhong Y, Saunders T, Morgan R, de Wilde RF, Maitra A, Hicks J, Demarzo AMet al. 2012Small cell and large cell neuroendocrine carcinomas of the pancreas are genetically similar and distinct from well-differentiated pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. American Journal of Surgical Pathology 36173–184. ( 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182417d36) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi T, Machida N, Morizane C, Kasuga A, Takahashi H, Sudo K, Nishina T, Tobimatsu K, Ishido K, Furuse Jet al. 2014Multicenter retrospective analysis of systemic chemotherapy for advanced neuroendocrine carcinoma of the digestive system. Cancer Science 1051176–1181. ( 10.1111/cas.12473) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yates LR, Gerstung M, Knappskog S, Desmedt C, Gundem G, Van Loo P, Aas T, Alexandrov LB, Larsimont D, Davies Het al. 2015Subclonal diversification of primary breast cancer revealed by multiregion sequencing. Nature Medicine 21751–759. ( 10.1038/nm.3886) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a