ABSTRACT

A variety of dermatological lesions have been described in COVID-19, although the prevalence and pathogenic relationship remain unclear particularly for chilblain-like lesions. Dermatological examination was performed in a prospective cohort of consecutive patients seen at the service for SARS-CoV-2 infection. Out of 417 patients with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection [median age 29.5 years (range 15–65); 62.5% males], dermatological lesions were detected in 7 (1.7%). Three patients had acral lesions; their age (range) was 15–29 years; all had a negative nasopharyngeal swab and developed IgG and/or IgM-specific antibodies; all presented none or mild symptoms. A fourth patient remained negative at repeated testing; mother, father and sister had a documented mild COVID-19. Non-acral lesions were observed in four older patients, with severe COVID-19. Chilblain-like lesions may be the sole manifestation of SARS-CoV-2 infection; their presence in asymptomatic school children and adolescents should be considered a potential signal of familial or community spread of the virus.

KEYWORDS: SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, acral lesions, chilblain-like lesions, cutaneous lesions

The coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 causes a broad spectrum disease (COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019), which involves primarily the respiratory tract [1]. However, there is increasing evidence that many extrapulmorary manifestations may occur, due to either dissemination of the virus or immunopathological mechanisms [2,3]. Endothelial cell damage has been proposed to play a key role in the pathogenesis of multi-organ involvement [4].

Controversial data are reported in literature about dermatological manifestations in Covid-19. Zhang et al. [5] described for the first time the clinical characteristics of seven patients with critical COVID-19 pneumonia and ischemia of fingers/toes whose presentation included cyanosis, skin bullae and dry gangrene. Acro-ischemia in this report appeared as a potential marker of severe disease and poor prognosis. Subsequently, several other cutaneous manifestations have been described showing different clinical patterns, notably varicella-like, papulo-vesicular, morbilliform rash, chilblain-like (or pernio), purpuric/petechial, livedoid and urticarial, associated to different stages of COVID-19 [1,6]. The overall prevalence is controversial, ranging from 0.2% to 20.4%, possibly influenced by study sample selection [7,8]. Age, stage of disease and other factors probably influenced the development of skin lesions.

Here, we report dermatological characteristics and significant pictures observed in a series of patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection, with prevalence of chilblain-like lesions in young subjects.

Patients and methods

From February to May 2020, 418 consecutive subjects accessed the service for CoV-2 infection: all underwent nasopharyngeal swab for SARS-CoV-2 RNA (RT PCR) and anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG/IgM test (MAGLUMI 2019-nCoV IgM/IgG CLIA); 417 had confirmed infection. A dermatological examination was performed in each patient, with consultant dermatologist.

The study was conducted according to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Dermatological lesions were present in 7 (1.7%) confirmed cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection out of the 417 subjects; the median age of the entire cohort was 29.5 years (range 15–65); 62.5% were males. The majority of the patients had an asymptomatic to moderate COVID-19. The main characteristics of the patients with skin lesions are summarized in Table 1. The Table includes an additional case (Case 3) of acral lesions, with negative SARS-CoV-2 infection markers, which is discussed below.

Table 1.

Main characteristics of the patients with skin lesions

| Case n. | M/F | Age (years) | Pneumonia | Days from the onset of COVID symptoms | Positive NPh * swab | COVID therapy | Site of cutaneous lesions | Days to resolution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | f | 29 | No | 3 | No | No | Acral lesions associated to erythema-oedema and pain, on toes and fingers | 14 |

| 2 | m | 19 | No | 13 | No | No | Red-purple pinpricks and cyanotic lesions of toes | 7 |

| 3** | m | 15 | No | No symptoms | No | No | Plantar surface painful papules; Erythemato-cyanotic bullous lesions of toes | >14 |

| 4 | m | 18 | No | 21 | No | No | Chilblain-like lesions of the toes Histology available | 14 |

| 5 | f | 52 | Yes | 7 | Yes | Remdesivir | Erythematous rash on the whole body | 3 |

| 6 | m | 59 | Yes | 8 | Yes | Hydroxychloroquine plus azithromycin | Multiple purpuric and erythematous lesions on the trunk and legs | 7 |

| 7 | m | 65 | Yes | 3 | Yes | Hydroxychloroquine plus azithromycin | Purpuric confluent rash in the area of calf muscle | 3 |

| 8 | f | 30 | No | 4 | Yes | No | Erythematous papular-pustular rash on the trunk | 7 |

*NPh = nasopharyngeal.

**Case 3 was negative at NPh swab and serology. See text for explanation.

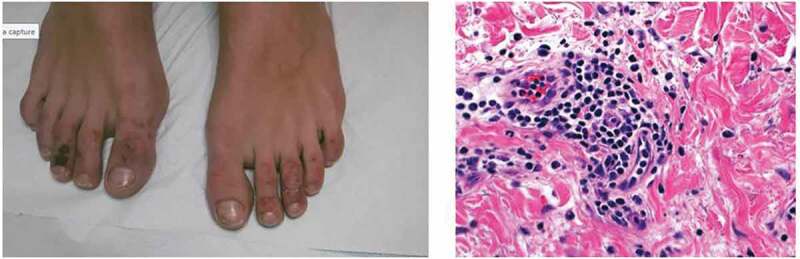

In all, four patients (Cases 1–4) had acral lesions (chilblain like); their age ranged from 15 to 29 years; all presented mild or no symptoms of COVID-19; none had pneumonia. Typical reddish-purple lesions were present on toes and in one patient on fingers also (Figure 1, left panel); the lesions were usually painful. The histological examination available for Case 4 showed the presence of lymphocitic vasculitis with microthrombotic pathological findings (Figure 1, right panel). The lesions resolved spontaneously within 2 weeks in three cases, while in one case (Case 3) had a longer biphasic course.

Figure 1.

(Case 4) Left panel: acral lesions characterized by ecchymotic lesions with a bruising appearance over the distal part of toes in a 18-year-old boy. Right panel: the histology showed a lymphocytic vasculitis with endothelial hyperplasia and lymphocytic infiltrate in the wall (hematoxilin-eosin 40x)

In the four patients, the nasopharyngeal swab for SARS-CoV-2 RNA was negative; in three of them, the anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies were detected. Of interest is Case 3, in whom the first symptoms had begun 3 weeks before our observation with painful red papules on the soles. The boy had no other symptoms whereas his pregnant mother, the father and the sister developed a flu-like syndrome with fever, dry cough and fatigue. The plantar surface papules and pain gradually resolved whereas typical erythemato-cyanotic lesions appeared on the toes. Nasopharyngeal swab for SARS-CoV-2 was positive in the mother and negative in all the other family members; all developed IgG anti-SARS-Cov-2 confirmed in two tests 4 weeks apart. The boy remained persistently negative for both nasopharyngeal swab and serological tests at the end of a 6-week follow-up.

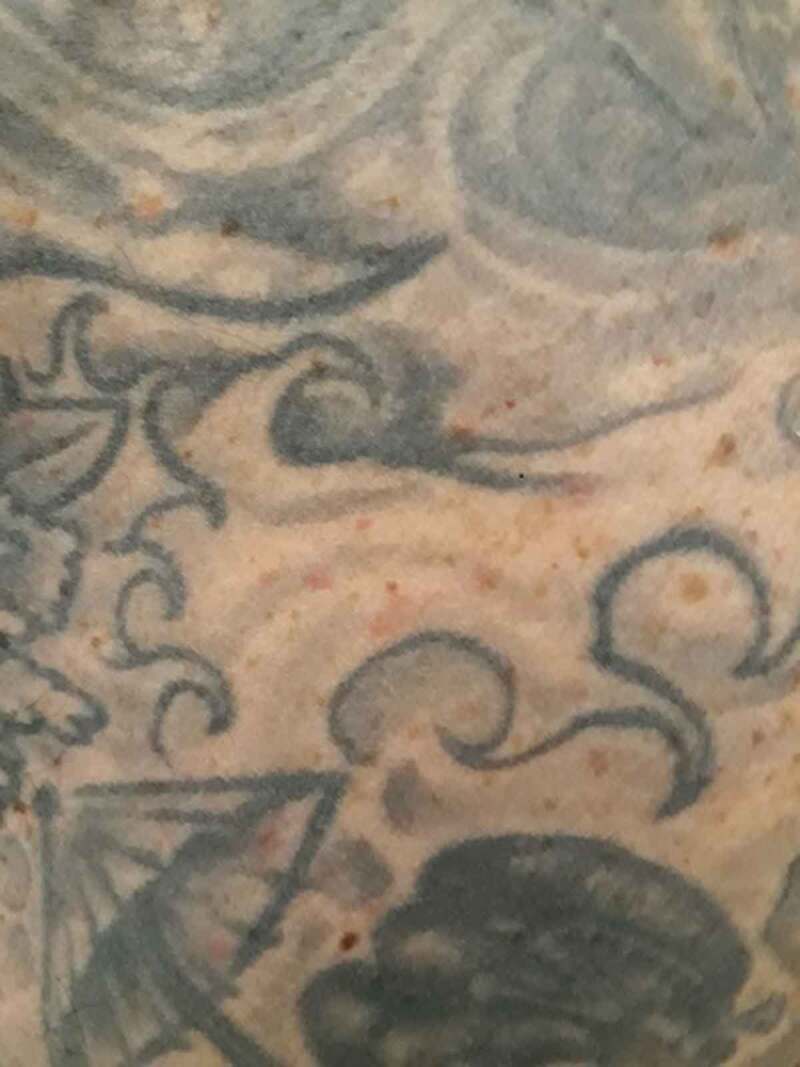

The four cases presenting non-acral lesions (Cases 5–8) were older (age range 30–65 years), all were symptomatic, of whom three with pneumonia. One patient (Case 8) presented an itchy erithematous papular and pustular rash on the trunk and arms, with onset at the same time of COVID-19 symptoms and resolution within 7 days (Figure 2). She was not receiving antiviral therapy. Of two patients with pneumonia, one presented an itchy erythematous rash on the whole body that was treated with low-dose steroids, without stopping antiviral therapy; the second patient, admitted in ICU, showed a purpuric confluent rash in the area of calf muscles (Figure 3), with an early onset and resolution within 3 days. Finally, a patient with extensive tattoing developed some days after symptoms multiple purpuric and erithematous skin lesions on the trunk and legs (Figure 4). A chest High Resolution CT scan showed interstitial pneumonia; after starting therapy with hydroxychloroquine plus azithromycin, the skin manifestations increased during the next 2 days and started to regress from the third day, until complete resolution on the fifth day, without stopping the therapy.

Figure 2.

(Case 8) Papular and pustular rash on the trunk in a 30-year-old woman

Figure 3.

(Case 7) Purpuric confluent rash in the area of the calf muscle in a 65-year-old man

Figure 4.

(Case 6) Multiple purpuric and erithematous lesions on the trunk in a 59-year-old man with extensine tattoing

All the patients with non-acral lesions had a positive nasopharyngeal swab; all cleared the virus and resolved COVID-19.

Discussion

Skin lesions were detected in 1.7% out of 417 patients with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection. In particular, the chilblain-like lesions in our as in other cases were present in young subjects and were characterized by microthrombotic pathological findings associated with an inflammatory vasculitis [9–11]. The association of chilblain-like lesions with SARS-CoV-2 infection remains uncertain; some studies attributed the lesions to the lifestyle changes during the lockdown measures since the SARS-CoV-2 RNA remained undetected on nasopharyngeal swabs and in biopsy samples and serological tests were negative in most cases [12–14]. Interestingly, chilblain-like lesions have been described in genetically induced overproduction of type I interferons, thus indirectly suggesting that a robust cellular mediated immunological reaction to SARS-CoV-2 might be the trigger for the lesion [15] while at the same time achieving a rapid control of the infection. Accordingly, in our four cases (Cases 1–4) the chilblain-like lesions were associated to an asymptomatic or mild disease, with negative nasopharyngeal swab in all and a positive serology for SARS-CoV-2 in three cases. In the fourth case (Case 3), which was not included in the prevalence calculation, specific antibodies were not demonstrated on repeated testing; however, the documented family SARS-CoV-2 spread strongly suggested a pathogenic relation with the virus as causative agent of the chilblain-like lesions observed in this patient. The age of the patients with chilblain-like lesions ranged from 15 to 29; Case 3 highlights that chilblain lesions may be the sole manifestation of SARS-CoV-2 infection and should be considered as a potential signal of familial or community spread of the virus.

The patients with non-acral lesions were older than those with acral lesions, had a positive nasopharyngeal swab and had a more severe COVID-19. In general, skin lesions appeared early in the course of the disease and resolved in a short time; their resolution paralleled viral clearance and clinical improvement which is consistent with the hypothesis of a direct virus-induced damage. For example, the papulo-pustular exanthema (Case 8), which is considered an early onset COVID-19 skin manifestation, is characterized by an interface inflammatory infiltrate similar to that observed in a drug-induced exanthema [6]. Anyway, aspecific macular and urticarial rashes, as observed in Case 5, remain very difficult to distinguish from a drug-induced reaction on a clinical basis.

In conclusion, different dermatological manifestations during SARS-CoV-2 infection occurred during different virological phases and possibly immune control of the infection; in some instances could be related to drug adverse reactions. Interestingly, the finding of chilblain-like lesions in asymptomatic young persons during an epidemic period should raise the suspect of SARS-CoV-2 infection, even in the absence of a positive nasopharyngeal swab or specific serum antibodies.

Disclosure statement

The authors have no conflict of interests to declare

References

- [1].Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Elmas OF, Demirbas A, Ozyurt K, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19: a review of the published literature. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33(4):13696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Gupta A, Madhavan MV, Sehgal K, et al. Extrapulmonary manifestations of COVID-19. Nat Med. 2020;26:1017–1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Teuwen LA, Geldhof V, Pasut A, et al. COVID-19: the vasculature unleashed. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020. Jul;20(7):389–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Zhang Y, Cao W, Xiao M, et al. Clinical and coagulation characteristics in 7 patients with critical COVID-2019 pneumonia and acro-ischemia. Zhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. 2020;41:302–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Gianotti R, Recalcati S, Fantini F, et al. Histopathological study of a broad spectrum of skin dermatoses in patients affected or highly suspected of infection by COVID-19 in the Northern Part of Italy: analysis of the many faces of the viral-induced skin diseases in previous and new reported cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2020;42(8):564–570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, et al.; China Medical Treatment Expert Group for Covid-19 . Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1708–1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Recalcati S. Cutaneous manifestations in COVID-19: a first perspective. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(5):e212–e213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Cordoro KM, Reynolds SD, Wattier R, et al. Clustered cases of acral perniosis: clinical features, histopathology, and relationship to COVID-19. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37(3):419–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Colmenero I, Santonja C, Alonso-Riaño M, et al. SARS–CoV-2 endothelial infection causes COVID-19 chilblains: histopathological, immunohistochemical and ultraestructural study of 7 paediatric cases. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183(4):729–737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Kanitakis J, Lesort C, Danset M, et al. Chilblain-like acral lesions during the COVID-19 pandemic (“COVID TOES”): histologic, immunofluorescence and immunohistochemical study of 17 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(3):870–875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Herman A, Peeters C, Verroken A, et al. Evaluation of Chilblains as a manifestation of the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156(9):998–1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Roca-Ginés J, Torres-Navarro I, Sánchez-Arráez J, et al. Assessment of acute acral lesions in a case series of children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156(9):992–997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Le Cleach L, Dousset L, Assier H, et al. Most chilblains observed during the COVID-19 outbreak occur in patients who are negative for COVID-19 on PCR and serology testing. Br J Dermatol. 2020. July 6;183(5):866–874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Fiehn C. Familial Chilblain Lupus - what can we learn from Type I interferonopathies? Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2017;19(10):61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]