Notes

Editorial note

There is a more recent Cochrane review on this topic: https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD013669.pub2

Abstract

Background

Self‐harm (SH; intentional self‐poisoning or self‐injury) is common, often repeated, and strongly associated with suicide. This is an update of a broader Cochrane review on psychosocial and pharmacological treatments for deliberate SH, first published in 1998 and previously updated in 1999. We have now divided the review into three separate reviews. This review is focused on pharmacological interventions in adults who self harm.

Objectives

To identify all randomised controlled trials of pharmacological agents or natural products for SH in adults, and to conduct meta‐analyses (where possible) to compare the effects of specific treatments with comparison types of treatment (e.g., placebo/alternative pharmacological treatment) for SH patients.

Search methods

For this update the Cochrane Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Review Group (CCDAN) Trials Search Co‐ordinator searched the CCDAN Specialised Register (September 2014). Additional searches of MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, and CENTRAL were conducted to October 2013.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials comparing pharmacological treatments or natural products with placebo/alternative pharmacological treatment in individuals with a recent (within six months) episode of SH resulting in presentation to clinical services.

Data collection and analysis

We independently selected trials, extracted data, and appraised trial quality. For binary outcomes, we calculated odds ratios (ORs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs). For continuous outcomes we calculated the mean difference (MD) and 95% CI. Meta‐analysis was only possible for one intervention (i.e. newer generation antidepressants) on repetition of SH at last follow‐up. For this analysis, we pooled data using a random‐effects model. The overall quality of evidence for the primary outcome was appraised for each intervention using the GRADE approach.

Main results

We included seven trials with a total of 546 patients. The largest trial included 167 participants. We found no significant treatment effect on repetition of SH for newer generation antidepressants (n = 243; k = 3; OR 0.76, 95% CI 0.42 to 1.36; GRADE: low quality of evidence), low‐dose fluphenazine (n = 53; k = 1; OR 1.51, 95% CI 0.50 to 4.58; GRADE: very low quality of evidence), mood stabilisers (n = 167; k = 1; OR 0.99, 95% CI 0.33 to 2.95; GRADE: low quality of evidence), or natural products (n = 49; k = 1; OR 1.33, 95% CI 0.38 to 4.62; GRADE: low quality of evidence). A significant reduction in SH repetition was found in a single trial of the antipsychotic flupenthixol (n = 30; k = 1; OR 0.09, 95% CI 0.02 to 0.50), although the quality of evidence for this trial, according to the GRADE criteria, was very low. No data on adverse effects, other than the planned outcomes relating to suicidal behaviour, were reported.

Authors' conclusions

Given the low or very low quality of the available evidence, and the small number of trials identified, it is not possible to make firm conclusions regarding pharmacological interventions in SH patients. More and larger trials of pharmacotherapy are required. In view of an indication of positive benefit for flupenthixol in an early small trial of low quality, these might include evaluation of newer atypical antipsychotics. Further work should include evaluation of adverse effects of pharmacological agents. Other research could include evaluation of combined pharmacotherapy and psychological treatment.

Keywords: Adult, Female, Humans, Male, Anticonvulsants, Anticonvulsants/therapeutic use, Antidepressive Agents, Antidepressive Agents/therapeutic use, Antipsychotic Agents, Antipsychotic Agents/therapeutic use, Fluphenazine, Fluphenazine/therapeutic use, Lithium Compounds, Lithium Compounds/therapeutic use, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Recurrence, Self-Injurious Behavior, Self-Injurious Behavior/drug therapy

Plain language summary

Drugs and natural products for self‐harm in adults

We have reviewed the international literature regarding pharmacological (drug) and natural product (dietary supplementation) treatment trials in this field. A total of seven trials meeting our inclusion criteria were identified. There is little evidence of beneficial effects of either pharmacological or natural product treatments. However, few trials have been conducted and those that have are small, meaning that possible beneficial effects of some therapies cannot be ruled out.

Why is this review important?

Self‐harm (SH), which includes intentional self‐poisoning/overdose and self‐injury, is a major problem in many countries and is strongly linked to suicide. It is therefore important that effective treatments for SH patients are developed. Whilst there has been an increase in the use of psychosocial interventions for SH in adults (which is the focus of a separate review), drug treatments are frequently used in clinical practice. It is therefore important to assess the evidence for their effectiveness.

Who will be interested in this review?

Clinicians working with patients who engage in SH, patients themselves, and their relatives.

What questions does this review aim to answer?

This review is an update of a previous Cochrane review from 1999 which found little evidence of beneficial effects of drug treatments on repetition of SH apart from for flupenthixol. This update aims to further evaluate the evidence for effectiveness of drugs and natural products for patients with SH with a broader range of outcomes.

Which studies were included in the review?

To be included in the review, studies had to be randomised controlled trials of drug treatments for adults who had recently engaged in SH.

What does the evidence from the review tell us?

There is currently no clear evidence for the effectiveness of antidepressants, antipsychotics, mood stabilisers, or natural products in preventing repetition of SH.

What should happen next?

We recommend further trials of drugs for SH patients, possibly in combination with psychological treatment.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Newer generation antidepressants versus placebo.

| Newer generation antidepressants (nomifensine, mianserin, paroxetine) compared to placebo for adults who engage in SH. | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults who engage in SH Settings: outpatient Intervention: NGAs (nomifensine, mianserin, paroxetine) Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo | NGAs | |||||

| Repetition of SH at last follow‐up | Study population | OR 0.76 (0.42 to 1.36) | 243 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | Quality was downgraded owing to serious risk of bias. Quality was further downgraded owing to serious imprecision. | |

| 375 per 1000 | 313 per 1000 (201 to 449) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g., the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; NGA: newer generation antidepressant; OR: odds ratio; SH: self‐harm. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Risk of bias was rated as SERIOUS as blinding of participants and blinding of outcome assessors was unclear leading to possible performance bias and detection bias. 2 Imprecision was rated as SERIOUS as the overall sample size for each trial is small.

Summary of findings 2. Antipsychotics versus placebo or another comparator drug/dose.

| Antipsychotics (flupenthixol, fluphenazine) compared to placebo or another comparator drug/dose for adults who engage in SH. | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults who engage in SH Settings: outpatient Intervention: antipsychotics (flupenthixol, fluphenazine) Comparison: placebo or another comparator drug/dose | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo or another comparator drug/dose | Antipsychotics | |||||

|

Repetition of SH at six months (flupenthixol vs. placebo) |

Study population | OR 0.09 (0.02 to 0.50) | 30 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | Quality of evidence was downgraded as this was a single, small trial (N = 37) in which random sequence generation, allocation concealment, and personnel blinding were rated as at unclear risk of bias. Quality was further downgraded owing to serious imprecision. | |

| 750 per 1000 | 213 per 1000 (57 to 600) | |||||

|

Repetition of SH at six months (low dose fluphenazine vs. ultra low dose fluphenazine) |

Study population | OR 1.51 (0.50 to 4.58) | 53 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | Quality of evidence was downgraded as this was a single, small trial (N = 53). Quality was further downgraded owing to serious imprecision. | |

| 346 per 1000 | 444 per 1000 (209 to 708) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g., the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; SH: self‐harm. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Risk of bias was rated as VERY SERIOUS as no details of allocation concealment or personnel blinding were provided leading to possible selection, performance, and detection bias. 2 Imprecision was rated as SERIOUS as the forest plot indicates the trial was associated with a wide confidence interval.

Summary of findings 3. Mood stabilisers versus placebo.

| Mood stabilisers (lithium) compared to placebo for adults who engage in SH. | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults who engage in SH Settings: outpatients Intervention: mood stabilisers (lithium) Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo | Mood stabilisers | |||||

| Repetition of SH at 12 months | Study population | OR 0.99 (0.33 to 2.95) | 167 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | Quality of evidence was downgraded as this was a single trial and there was evidence of a significant imbalance between the treatment and control groups at baseline. | |

| 84 per 1000 | 84 per 1000 (29 to 214) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g., the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; SH: self‐harm. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Risk of bias was rated as VERY SERIOUS as no details of allocation concealment or personnel blinding were provided leading to possible selection, performance, and detection bias. 2 The trial was further downgraded as there was substantial imbalance between the intervention and control groups in terms of the proportion of participants with a history of multiple suicide attempts, scores on the Suicide Intent Scale for the index attempt, and the proportion of participants diagnosed with any personality disorder suggesting the presence of possible confounding.

Summary of findings 4. Natural products versus placebo.

| Natural products (omega‐3 fatty acid supplementation) compared to placebo for adults who engage in SH. | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults who engage in SH Settings: outpatients Intervention: natural products (omega‐3 fatty acid supplementation) Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo | Natural products | |||||

| Repetition of SH during 12 week treatment phase | Study population | OR 1.33 (0.38 to 4.62) | 49 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | Quality of evidence was downgraded owing to possible performance and detection bias and serious imprecision. | |

| 259 per 1000 | 318 per 1000 (117 to 618) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g., the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; SH: self‐harm. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Risk of bias was rated as SERIOUS as no details on outcome assessor blinding were provided leading to possible performance and detection bias. 2 Imprecision was also rated as SERIOUS owing to the wide confidence interval associated with the estimate of treatment effect.

Background

Description of the condition

The term ‘self‐harm’ is used to describe all intentional acts of self‐poisoning (e.g., overdoses) or self‐injury (e.g., self‐cutting), irrespective of degree of suicidal intent or other types of motivation (Hawton 2003a). Thus it includes acts intended to result in death (‘attempted suicide’), those without suicidal intent (e.g., to communicate distress, to temporarily reduce unpleasant feelings), and those with mixed motivation (Hjelmeland 2002; Scoliers 2009). The term ‘parasuicide’ was introduced by Kreitman 1969 to include the same range of behaviour. However, ‘parasuicide’ has been used in the United States of America (USA) to refer specifically to acts of self‐harm without suicidal intent (Linehan 1991), and the term has largely fallen into disuse in the United Kingdom (UK) and other countries. In the fifth version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM‐5; American Psychiatric Association 2013), two types of self‐harming behaviour are included as conditions for further study, namely "Non‐Suicidal Self Injury" (NSSI) and "Suicidal Behavior Disorder" (SBD). Many researchers and clinicians, however, believe this to be an artificial and somewhat misleading categorisation (Kapur 2013). We have therefore used the approach favoured in the UK and some other countries where all intentional self‐harm is conceptualised in a single category, namely self‐harm (SH). Within this category, suicidal intent is regarded as a dimensional rather than a categorical concept. For readers more familiar with the NSSI and SBD distinction, SH can be regarded as an umbrella term for these two behaviours (although it should be noted that neither NSSI nor SBD include non‐fatal self‐poisoning).

SH has been a growing problem in most countries over the past 40 years. In the UK it is estimated that there are now more than 200, 000 related presentations to general hospitals per year (Hawton 2007). In addition, SH often occurs in the community and does not result in presentation to hospital or other clinical services (Borges 2011). SH consumes considerable hospital resources in both high income countries (Gibbs 2004; Claassen 2006; Schmidtke 1996; Schmidtke 2004) and low to middle income countries (Fleischmann 2005; Kinyanda 2005; Parkar 2006). Methods of SH vary, however, between high income and low to middle income countries. In high income countries, self‐poisoning frequently involves overdoses of analgesics and psychotropic drugs (Hawton 2003a; Värnik 2004; Gjelsvik 2012). In low to middle income countries, pesticides are often consumed, particularly in rural areas (Eddleston 2000; Gunnell 2003). Self‐cutting and other forms of self‐mutilation are probably the most common forms of non‐fatal self‐injury in both high and low to middle income countries. However, fatal self‐injury in high income countries most commonly involves hanging and firearms (World Health Organization 2014), whereas in some low to middle income countries, self‐immolation is not uncommon (Ahmadi 2007).

In most countries, SH (unlike suicide) occurs more commonly in females than males. However, the gender difference decreases over the life cycle (Hawton 2008), and in some countries the difference between the genders may have decreased in recent years (Perry 2012). SH predominantly occurs in young people, with 60‐70% of individuals in many studies being aged under 35 years. In females, rates tend to be particularly high among 15‐24 year olds, whereas in males the highest rates are usually among those in their late 20s and early 30s. SH is less common in older people, but then tends to be associated with high suicidal intent (Hawton 2008), with consequent greater risk of suicide (Murphy 2012).

Many people who engage in SH are facing acute life problems, often in the context of longer‐term difficulties (Hawton 2003b). Common problems include disrupted relationships, employment issues, financial and housing trouble, and social isolation. In older people, physical health problems, bereavement, and threatened loss of independence become increasingly important. Alcohol abuse and, to a lesser extent, drug misuse are often present. There may be a history of physical and/or sexual abuse and other adverse experiences.

Both psychological and biological factors appear to increase vulnerability to SH. Many patients who present to hospital following SH have psychiatric disorders, especially depression, anxiety and substance misuse (Hawton 2013); these disorders frequently occur in combination with a personality disorder (Haw 2001). Biological factors include disturbances in the serotonergic and stress‐response systems (van Heeringen 2014).

SH is often repeated, with 15‐25% of individuals who present to hospital with SH returning to the same hospital following a repeat episode within a year (Owens 2002; Carroll 2014). Studies from Asia suggest a lower risk of repetition (Carroll 2014), although there may be other repeat episodes that result in presentation to another hospital, or do not result in hospital presentation at all. Repetition is more common in individuals who have a history of previous SH, personality disorder, psychiatric treatment, and alcohol or drug misuse (Larkin 2014).

The risk of death by suicide within one year amongst people who present to hospital with SH varies across studies from nearly 1% to over 3% (Owens 2002; Carroll 2014). This variation reflects the characteristics of the SH population and the background national suicide rate. In the UK, during the first year after an SH episode the risk is 50–100 times that of the general population (Hawton 1988; Hawton 2003b; Cooper 2005). Of people who die by suicide, over half will have a history of SH (Foster 1997) and at least 15% will have presented to hospital with SH in the preceding year (Gairin 2003). A history of SH is the strongest risk factor for suicide across a range of psychiatric disorders (Sakinofsky 2000), and repetition of SH further increases the risk of suicide (Zahl 2004).

Description of the intervention

Given the high prevalence of depression in patients who engage in SH, antidepressants are often used in treatment in the same dose range as is generally used to treat depression. However, owing to the increased risk of overdose in this population, including the likelihood that patients who engage in self‐poisoning may use their own medication, antidepressants associated with lower case fatality indices (e.g., selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs); Hawton 2010) will generally be preferred.

In patients with a history of repetition of SH, especially those with a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder (BPD), treatment with antipsychotics may be used, although there is little evidence for their efficacy in reducing suicidal behaviour (Stoffers 2010).

Attention has also focused on the potential efficacy of mood stabilisers for this population, including both antiepileptic medications and lithium, given the high prevalence of recurrent mood disorders in people who engage in SH. There is currently little evidence that antiepileptics reduce risk of suicidal behaviour; however, there is accumulating evidence that lithium has specific antisuicidal effects, including reducing both the risk of SH and suicide in patients with affective disorders (Cipriani 2013a).

The high prevalence of anxiety disorders in this population (Hawton 2013) also suggests that other pharmacological agents, such as benzodiazepines and other sedatives, might be expected to have an important role in treatment. However, benzodiazepines may increase the risk of repetition of SH (Verkes 2000). Therefore it is usually recommended that benzodiazepines are used very cautiously, if at all, in people at risk of SH (Verkes 2000).

There is also interest in the use of natural products (e.g., dietary supplementation of omega‐3 fatty acids) to treat a variety of mental disorders, including suicidal behaviour, but there is little convincing evidence of their efficacy at present (Ross 2007).

How the intervention might work

Antidepressants

Antidepressants in general would be expected to improve mood in individuals with depression and, hence, decrease thoughts and acts of SH. Antidepressant medications can be divided into tricyclics and newer generation antidepressants (e.g., SSRIs). Tricyclic antidepressants primarily inhibit both serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake, whereas SSRIs specifically target synaptic serotonergic reuptake (Feighner 1999). Given the link between serotonin activity, impulsivity, and suicidal behaviour (van Heeringen 2014), both tricyclic and SSRI antidepressants may be associated with a serotonin‐mediated reduction in impulsivity and enhanced emotion regulation which might possibly reduce the likelihood that an individual will engage in SH.

Antipsychotics

One risk factor for SH, including repetition of the behaviour, may be heightened arousal, especially in relation to stressful life events. Rationale for the use of antipsychotics is that by reducing this arousal, the urge to engage in SH may be reduced. Lower doses might be used to obtain this effect than are used in the treatment of psychotic disorders (Battaglia 1999).

Mood stabilisers (including antiepileptics)

Mood stabilisers have specific benefits for patients with bipolar disorder or unipolar depression, especially in terms of preventing recurrence of episodes of mood disorder (Geddes 2004; Cipriani 2013b). It might therefore be anticipated that these drugs would have benefits in terms of reducing the risk of suicidal behaviour, although currently such an effect has only been shown for lithium (Cipriani 2013a). Lithium may reduce the risk of suicidal behaviour via a serotonin‐mediated reduction in impulsivity and aggression. It is also possible that the long‐term clinical monitoring that all patients prescribed lithium treatment must undergo might contribute to a reduction in SH (Cipriani 2013a).

Other pharmacological agents

Benzodiazepines might be anticipated to reduce suicidal behaviour through their specific effects on anxiety (Tyrer 2012). However, because of their GABAminergic effects, benzodiazepines may also increase aggression and disinhibition (Albrecht 2014), which may increase the risk of suicidal behaviour. Other pharmacological agents, particularly the N‐Methyl‐D‐aspartate receptor antagonist ketamine, may also have beneficial effects on suicidal ideation in patients with major depression. However, it is presently unclear whether ketamine has a specific antisuicidal effect, or rather, whether its effectiveness is due to a reduction in general depressive symptomatology (Fond 2014).

Natural products

The main focus with regard to natural products and suicidal behaviour has been on dietary supplementation of omega‐3 fatty acids (fish oils; Tanskanen 2001). Omega‐3 fatty acids have been implicated in the neural network shown to correlate with the lethality of recent suicidal behaviour (Mann 2013). Blood plasma polyunsaturated fatty acid levels have also been implicated in the serotonin‐mediated link between low cholesterol and suicidal behaviour, suggesting that low omega‐3 fatty acid levels may have a negative impact on serotonin function (Sublette 2006). Omega‐3 supplementation, in contrast, might stimulate serotonin activity, thereby reducing the likelihood that an individual will engage in impulsive behaviours, such as SH (Brunner 2002).

Why it is important to do this review

SH is a major social and healthcare problem. It represents significant morbidity, is often repeated, and has strong links to suicide. It also leads to substantial healthcare costs (Sinclair 2011). Many countries now have suicide prevention strategies (World Health Organization 2014), all of which include a focus on improved management of patients presenting with SH because of their greatly elevated suicide risk, and also because of their high levels of psychopathology and distress. The National Suicide Prevention Strategy for England (Department of Health 2012) and the USA's National Strategy for Suicide Prevention (Office of the Surgeon General (US) 2012), for example, highlight SH patients as a key high risk group to be given special attention. In recent years there has also been considerable focus on improving the standards of general hospital care for SH patients. In 1994 the Royal College of Psychiatrists published consensus guidelines for such services (Royal College of Psychiatrists 1994), and in 2004 produced revised guidelines (Royal College of Psychiatrists 2004). While these guidelines focus particularly on organisation of services and assessment of patients, there is clearly a need for effective treatments for SH patients; these may include pharmacological as well as psychosocial interventions. In 2004 the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE; NCCMH 2004) produced a guideline on SH which focused on its short‐term physical and psychological management. More recently, NICE produced a second guide with an aim towards longer‐term management (NICE 2011), using some interim data from the present review as the evidence base on therapeutic interventions. A similar guideline was produced in Australia and New Zealand (Boyce 2003). We had previously conducted a systematic review of treatment interventions for SH patients, in terms of reducing repetition of SH, which highlighted the paucity of evidence for effective treatments, at least in terms of this outcome (Hawton 1998; Hawton 1999); the first NICE guideline essentially reinforced this conclusion (NCCMH 2004). Using interim data from the present review, the second NICE guideline concluded that there was evidence showing clinical benefit of brief psychological interventions in reducing repetition of SH, compared with routine care (NICE 2011). However, there was no evidence of similar beneficial effects for pharmacological treatments.

We have now fully updated our original review in order to provide contemporary evidence to guide clinical policy and practice. We have also divided the review into three reviews: the present review which focuses on pharmacological interventions for adults, a second review on psychosocial interventions for adults, and the third on interventions for children and adolescents. In the earlier review we focused on repetition of SH and suicide as the main outcomes. In this update, we have now also included data on treatment adherence, depression, hopelessness, suicidal ideation, and problem‐solving.

Objectives

To identify all randomised controlled trials (RCTs) on pharmacological agents or natural products for SH in adults, and to conduct meta‐analyses (where possible) to compare the effects of specific treatments with comparison types of treatment (e.g., placebo or alternative pharmacological treatment) for SH patients.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials, including cluster randomised and cross‐over trials, of specific pharmacological agents or natural products versus placebo or any other pharmacological comparisons in the treatment of adult SH patients.

Types of participants

Participant characteristics

Participants were adult males and females (age 18 and over) of all ethnicities. We also included trials where there were a small minority (<15%) of adolescent participants. However, we undertook sensitivity analyses to assess the effect of inclusion of such trials.

Diagnosis

Participants who had engaged in any type of non‐fatal intentional self‐poisoning or self‐injury in the six months prior to trial entry resulting in presentation to clinical services were included. There were no restrictions on the frequency with which patients engaged in SH; thus, for example, we included trials where participants had frequently repeated SH (e.g., those with self‐harming behaviour as part of borderline personality disorder).

We defined SH as any non‐fatal intentional act of self‐poisoning or self‐injury, irrespective of degree of suicidal intent or other types of motivation. Thus it includes acts intended to result in death ("attempted suicide"), those without suicidal intent (e.g., to communicate distress, to temporarily reduce unpleasant feelings), and those with mixed motivation. Self‐poisoning includes both overdoses of medicinal drugs and ingestion of substances not intended for consumption (e.g., pesticides). Self‐injury includes acts such as self‐cutting, self‐mutilation, attempted hanging, and jumping in front of moving vehicles. We only included trials where participants presented to clinical services as a result of SH.

Co‐morbidities

There were no restrictions in terms of whether or not patients had psychiatric disorders, or the nature of those disorders, with the exception of intellectual disability, where any SH behaviour is likely to be repetitive (e.g., head banging) as the purpose of this behaviour is usually different from that involved in SH. The reader is instead referred to a recent Cochrane review of pharmacological interventions for self‐injury in this population (Rana 2013).

Setting

Interventions delivered in inpatient or outpatient settings were eligible for inclusion, as were trials from any country.

Subset data

We did not include trials in which only some participants had engaged in SH or trials of people with psychiatric disorders in which SH was an outcome variable but was not an inclusion criterion for entry into the trial.

Types of interventions

Experimental interventions

These included:

Tricyclic antidepressants (TADs; e.g., amitriptyline);

Newer generation antidepressants (NGAs), including SSRIs (e.g., fluoxetine), serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs; e.g., venlafaxine), norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (NRIs; e.g., reboxetine), tetracyclic antidepressants (TAs; e.g., maprotiline), noradrenergic specific serotonergic antidepressants (NaSSAs; e.g., mirtazapine), serotonin antagonist or reuptake inhibitors (SARIs; e.g., trazodone), or reversible inhibitors of monoamine oxidase type A (RIMAs; e.g., moclobemide);

Any other antidepressants such as irreversible mono‐amine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs; e.g., bupropion);

Antipsychotics (e.g., olanzapine);

Mood stabilisers, including antiepileptics (e.g., sodium valporate) and lithium;

Other pharmacological agents (e.g., benzodiazepines, ketamine);

Natural products (e.g., omega‐3 essential fatty acid supplementation).

Comparator interventions

While treatment as usual (TAU), which usually refers to routine clinical service provision, is often used as a comparator in trials of psychosocial interventions, it is not generally used in pharmacological trials, where comparison with the specific effects of an active drug is being made. For the purposes of the current review, then, the comparator was placebo, which consisted of any pharmacologically inactive treatment such as sugar pills or injections with saline, or another comparator pharmacological intervention (e.g., another standard pharmacological agent, or reduced dose of the intervention agent).

Combination interventions

We also planned to include combination interventions where any pharmacological agent of any class as outlined above is combined with psychological therapy. However, as the focus of this review is the effectiveness of pharmacological agents for SH patients, we only included such trials if both the intervention and control groups received the same psychological therapy to ensure that any potential effect of the psychosocial therapy was balanced across both groups. The effectiveness of psychosocial therapy in adults is the subject of a separate review.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

The primary outcome measure in this review was the occurrence of repeated SH (defined above) over a maximum follow‐up period of two years. Repetition was identified through self‐report, collateral report, clinical records, or research monitoring systems. As we wished to incorporate the maximal amount of data from each trial, we included both self‐reported and hospital records of SH where available. We also assessed frequency of repetition of SH at final follow‐up.

Secondary outcomes

1. Treatment adherence

This was assessed using a range of measures of adherence, including pill counts, changes in blood measures, and the proportion of participants that both started and completed treatment.

2. Depression

This was assessed either continuously, as scores on psychometric measures of depression symptoms (for example total scores on Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck 1961) or scores on the depression sub‐scale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS; Zigmond 1983)), or dichotomously, as the proportion of patients reaching defined diagnostic criteria for depression.

3. Hopelessness

This was assessed by scores on psychometric measures of hopelessness, for example, total scores on the Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS; Beck 1974).

4. Suicidal ideation

This was assessed either continuously, as scores on psychometric measures of suicidal ideation (for example total scores on the Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation (BSS; Beck 1988)), or dichotomously, as the proportion of patients reaching a defined cut‐off for ideation.

5. Problem‐solving

This was assessed either continuously, as scores on a psychiatric measure of problem‐solving ability (for example total scores on the Problem Solving Inventory (PSI; Heppner 1988)), or dichotomously, as the proportion of patients with improved problems.

6. Suicide

This included both register‐recorded deaths and reports from collateral informants such as family members or neighbours.

Timing of outcome assessment

We reported outcomes for the following time periods:

During treatment.

At the conclusion of the treatment period.

Between zero and six months after the conclusion of the treatment period.

Between six and 12 months after the conclusion of the treatment period.

Between 12 and 24 months after the conclusion of the treatment period.

Hierarchy of outcome assessment

Where a trial measured the same outcome (e.g., depression) in two or more ways, we used the most common measure across trials in any meta‐analysis, but we also reported scores from the other measure in the text of the review.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

1. The Cochrane Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Review Group's Specialised Register (CCDANCTR) The Cochrane Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Group (CCDAN) maintains two clinical trials registers at their editorial base in Bristol, UK: a references register and a studies‐based register. The CCDANCTR‐References register contains over 37,500 reports of randomised controlled trials on depression, anxiety and neurosis. Approximately 60% of these references have been tagged to individual, coded trials. The coded trials are held in the CCDANCTR‐Studies register and records are linked between the two registers through the use of unique study ID tags. Coding of trials is based on the EU‐Psi coding manual. Please contact the CCDAN Trials Search Coordinator for further details.

Reports of trials for inclusion in the group's registers are collated from weekly generic searches of MEDLINE (1950 to date), EMBASE (1974 to date), and PsycINFO (1967 to date), as well as quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL).

The CCDANCTR (Studies and References) was searched on 2 September 2014 using terms for self‐harm (condition only), as outlined in Appendix 1.

No restrictions on date, language, or publication status were applied to the search.

2. Additional electronic database searches

Complementary searches of MEDLINE (1998 to 2013), EMBASE (1998 to 2013), PsycINFO (1998 to 2013), and CENTRAL (The Cochrane Library, 1998 to 2013) were conducted by Sarah Stockton, librarian at the University of Oxford, following the search strategy outlined in Appendix 2. Additionally, KW searched the Australian Suicide Prevention RCT Database (Christensen 2014). KW also conducted electronic searches of ClinicalTrials.gov and the ISRCTN registry using the keywords random* AND suicide attempt* OR self$harm* to identify relevant ongoing trials.

Both the original version of this review and an unpublished version also incorporated searches of SIGLE (1980 to March 2005) and SocioFile (1963‐July 2006).

Searching other resources

Hand searching

For the original version of this review, the authors hand searched ten specialty journals within the fields of psychology and psychiatry, including all English language suicidology journals, as outlined in Appendix 3. As these journals are now indexed in major electronic databases, hand searching was not repeated for this update.

Reference lists

The reference lists of all relevant papers known to the investigators were checked, as were the reference lists of major reviews which include a focus on interventions for SH patients (Baldessarini 2003; Baldessarini 2006; Beasley 1991; Brausch 2012; Burns 2000; Cipriani 2005; Cipriani 2013a; Comtois 2006; Crawford 2007a; Crawford 2007b; Daigle 2011; Daniel 2009; Dew 1987; Gould 2003; Gray 2001; Gunnell 1994; Hawton 1998; Hawton 1999; Hawton 2012; Hennen 2005; Hepp 2004; Hirsch 1982; Kapur 2010; Kliem 2010; Lester 1994; Links 2003; Lorillard 2011a; Lorillard 2011b; Luxton 2013; Mann 2005; McMain 2007; Milner 2015; Möller 1989; Möller, 1992; Montgomery 1995; Muehlenkamp 2006; Müller‐Oerlinghausen 2005; Nock 2007; Ougrin 2011; Ougrin 2015; Smith 2005; Stoffers 2010; Tarrier 2008; Tondo 1997; Tondo 2000; Tondo 2001; Townsend 2001; van der Sande 1997).

Correspondence

The authors of trials and other experts in the field of suicidal behaviour were consulted to find out if they were aware of any ongoing or unpublished RCTs concerning the use of pharmacological interventions for adult SH patients.

Data collection and analysis

For details of the data collection and analysis methods used in the original version of this review see Appendix 4.

Selection of studies

For this update of the review, all authors independently assessed the titles of trials identified by the systematic search for eligibility. A distinction was made between:

Eligible trials, in which any psychopharmacological treatment was compared with a control (e.g., placebo medication or comparator drug/dose).

General treatment trials (without any control treatment).

All trials identified as potentially eligible for inclusion then underwent a second screening. Pairs of review authors, working independently from one another, screened the full text of relevant trials to identify whether the trial met our inclusion criteria.

Disagreements were resolved following consultation with KH. Where disagreements could not be resolved from the information reported within the trial, or where it was unclear whether the trial satisfied our inclusion criteria, study authors were contacted to provide additional clarification.

Data extraction and management

In the current update, data from included trials was extracted by KW and one of either TTS, EA, DG, PH, ET, or KvH using a standardised extraction form. Review authors extracted data independently of one another. Where there were any disagreements, these were resolved through consensus discussions with KH.

Data extracted from each eligible trial concerned participant demographics, details of the treatment and control interventions, and information on the outcome measures used to evaluate the efficacy of the intervention. Study authors were contacted to provide raw data for outcomes that were not reported in the full text of included trials.

Both dichotomous and continuous outcome data were extracted from eligible trials. As the use of non‐validated psychometric scales is associated with bias, we extracted continuous data only if the psychometric scale used to measure the outcome of interest had been previously published in a peer‐reviewed journal (Marshall 2000), and was not subjected to item, scoring, or other modification by the trial authors.

We planned the following main comparisons.

Tricyclic antidepressants versus placebo.

Tricyclic antidepressants versus another comparator drug/dose.

Newer generation antidepressants versus placebo.

Newer generation antidepressants versus another comparator drug/dose.

Any other antidepressants versus placebo.

Any other antidepressants versus another comparator drug/dose.

Antipsychotics versus placebo.

Antipsychotics versus another comparator drug/dose.

Mood stabilisers versus placebo.

Mood stabilisers versus another comparator drug/dose.

Other pharmacological agents versus placebo.

Other pharmacological agents versus another comparator drug/dose.

Natural products versus placebo.

Natural products versus another comparator drug/dose.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Given that highly biased trials are more likely to overestimate treatment effectiveness (Moher 1998), the quality of included trials was evaluated independently by KW and one of either TTS, EA, DG, PH, ET, or KvH using the criteria described in Higgins 2008a. This tool encourages consideration of the following domains:

Random sequence generation.

Allocation concealment.

Blinding of participants and personnel.

Blinding of outcome assessment.

Incomplete outcome data.

Selective outcome reporting.

Other bias.

Each study was judged as being at "low", "high", or "unclear" risk of each potential bias, and a supporting quotation from the trial report was incorporated to justify this judgment. Where inadequate details of the randomisation, blinding, or outcome assessment procedures were provided in the original report, we contacted authors to provide clarification. Disagreements were resolved following discussion with KH. Risk of bias for each included trial is reported in the text of the review.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous outcomes

We summarised dichotomous outcomes, such as the number of participants engaging in a repeat SH episode and the number of deaths by suicide, using summary odds ratios (OR) and the accompanying 95% confidence interval (CI), as OR is the most appropriate effect size statistic for summarising associations between two dichotomous groups (Fleiss 1994).

Continuous outcomes

For outcomes measured on a continuous scale, we used mean differences (MD) and accompanying 95% CI where the same outcome measure was employed. In future updates of this review, if different scales are used to assess a given outcome, we will use the standardised mean difference (SMD) and its accompanying 95% CI.

Trials were aggregated for the purposes of meta‐analysis only if treatments were sufficiently similar. For trials that could not be included in a meta‐analysis, we have instead provided narrative descriptions of the results.

Unit of analysis issues

Zelen design trials

Trials in this area are increasingly employing Zelen's method in which consent is obtained subsequent to randomisation and treatment allocation. This design may lead to bias if, for example, participants allocated to one particular arm of the trial disproportionally refuse to provide consent for participation or, alternatively, if participants only provide consent if they are allowed to cross‐over to the other treatment arm (Torgerson 2004). No trial included in this review used Zelen's design. Given the uncertainty of whether to use data for the primary outcome based on all those randomised to the trial, or only those who consent to participation, should a trial using Zelen's method be identified in future updates of this review we plan to extract data using both sources where possible. We also plan to conduct sensitivity analyses to investigate what impact, if any, the inclusion of these trials may have on the pooled estimate of treatment effectiveness.

Cluster randomised trials

Cluster randomisation, for example by clinician or general practice, can lead to overestimation of the significance of a treatment effect, resulting in an inflation of the nominal type I error rate, unless appropriate adjustment is made for the effects of clustering (Donner 2002; Kerry 1998). Although no trials identified by this review used cluster randomisation methods, should any future trials in this area use this design we will follow the guidance outlined in Higgins 2008b, section 16.3.4.

Cross‐over trials

A primary concern with cross‐over trials is the "carry‐over" effect in which the effect of the intervention treatment (e.g., pharmacological, physiological, or psychological) influences the participant's response to the subsequent control condition (Elbourne 2002). As a consequence, on entry to the second phase of the trial, participants may differ systematically from their initial state despite a wash‐out phase. This, in turn, may result in a concomitant underestimation of the effectiveness of the treatment intervention (Curtin 2002a; Curtin 2002b). Once again, no trials included in the current review used cross‐over methodology. However, should we identify any such trials in future updates, only data from the first phase of the trial, prior to cross‐over, will be extracted to protect against the carry‐over effect.

Studies with multiple treatment groups

One trial in the current review included multiple treatment groups (Hirsch 1982). As both intervention arms in this trial investigated the effectiveness of a newer generation antidepressant, we combined dichotomous data from these two arms and compared the combined data with data from the placebo arm. For outcomes reported on a continuous scale, we combined data using the formula given in Higgins 2008c, section 7.7.3.8.

Studies with adjusted effect sizes

None of the trials included in the current update provided adjusted effect sizes. In future updates of this review, however, where trials report both unadjusted and adjusted effect sizes, we will include only unadjusted effect sizes.

Dealing with missing data

We as review authors did not impute missing data as we considered that the bias that would be introduced by doing this would have outweighed any benefit (in terms of increased statistical power) that may have been gained by the inclusion of imputed data. However, where authors omitted standard deviations (SD) for continuous measures, these were estimated using the method described in Townsend 2001.

Dichotomous data

Although many authors conducted their own intention‐to‐treat analyses, none presented intention‐to‐treat analyses as defined by Higgins 2008b. Therefore, outcome analyses for both dichotomous and continuous data were based on all information available on trial participants. For dichotomous outcomes, we included data on only those participants whose results were known, using as the denominator the total number of participants with data for the particular outcome of interest at follow‐up, as recommended (Higgins 2008b).

Continuous data

For continuous outcomes, we have included data only on observed cases.

Missing data

Where data on outcomes of interest were incomplete or were excluded from the text of the trial, study authors were contacted in order to try to obtain further information.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Between‐study heterogeneity can be assessed using either the Chi2 or I2 statistics. In this review, however, we used only the I2 statistic to determine heterogeneity as this is considered to be more reliable (Higgins 2003). The I2 statistic indicates the percentage of between‐study variation due to chance (Higgins 2003), and can take any value from 0% to 100%. We used the following values to denote unimportant, moderate, substantial, and considerable heterogeneity, respectively: 0% to 40%, 30% to 60%, 50% to 90%, and 75% to 100% as per the guidance in the Cochrane Handbook (Deeks 2008). Where we found substantial levels of heterogeneity (i.e., ≥ 75%), reasons for this heterogeneity were explored. We also planned to investigate heterogeneity when the I2 statistic was lower than 75% where either the direction or magnitude of a trial effect size was clearly discrepant from that of other trials included in the meta‐analysis (see Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity section for further information on these analyses).

Assessment of reporting biases

Reporting bias occurs when the decision to publish a particular trial is influenced by the direction and significance of its results (Egger 1997). Research suggests, for example, that trials with statistically significant findings are more likely to be submitted for publication and to subsequently be accepted for publication (Hopewell 2009), leading to possible overestimation of the true treatment effect. To assess whether trials included in any meta‐analysis were affected by reporting bias, we entered their data into a funnel plot but only, as recommended, when a meta‐analysis included results from at least ten trials. Where evidence of any small‐study effects were identified, reasons for funnel plot asymmetry, including the presence of publication bias, were explored (Egger 1997).

Data synthesis

For the purposes of meta‐analysis, we calculated the pooled OR and accompanying 95% CI using the random‐effects model as this is the most appropriate model for incorporating heterogeneity between trials (Deeks 2008, section 9.5.4). Specifically, for dichotomous data, the Mantel‐Haenszel method was used whilst the inverted variance method was used for continuous data. However, a fixed‐effect analysis was also undertaken to investigate the potential effect of method choice on the estimates of treatment effect. Any material differences in ORs between these two methods are reported descriptively in the text of the review. All analyses were undertaken in RevMan, version 5.3.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Subgroup analyses

In the original version of this review, we had planned to undertake subgroup analyses by repeater status and gender but found there were insufficient data. Consequently, in this update we only undertook a priori subgroup analyses by gender or repeater status where there were sufficient data to do so.

Investigation of heterogeneity

Although no meta‐analysis was associated with substantial levels of between‐study heterogeneity (i.e., I2 ≥75%) in this review, in future updates, should this be the case KH and KW would independently triple‐check the data to ensure it had been correctly entered. Assuming data have been entered correctly, we would then investigate the source of this heterogeneity by visually inspecting the forest plot and removing each trial which had a very different result to the general pattern of the others until homogeneity was restored as indicted by an I2 statistic <75%. We would report the results of this sensitivity analysis in the text of the review alongside hypotheses regarding the likely causes of the heterogeneity.

Sensitivity analysis

We undertook sensitivity analyses, where appropriate, as outlined below:

Where a trial or trials made use of Zelen's method of randomisation (see Unit of analysis issues section).

Where a trial or trials contributed substantial levels of between‐study heterogeneity (see Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity section).

Where a trial or trials included a mixture of both adolescent and adult participants.

Where a trial or trials specifically recruited individuals diagnosed with borderline personality disorder.

'Summary of findings' tables

A 'Summary of findings' table was prepared for the primary outcome measure, repetition of SH, following recommendations outlined in Schünemann 2008a, section 11.5. This table provides information concerning the overall quality of evidence from each included trial. The 'Summary of findings' table was prepared using GRADEpro software (GRADEpro). Quality of the evidence was assessed following recommendations in Schünemann 2008b, section 12.2.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

For this update, a total of 23,725 citations were found using the search strategy outlined in Appendix 1 and Appendix 2. A further 10 were identified through correspondence and discussion with researchers in the field; these trials were ongoing at the time of the systematic search. All but one have subsequently been published and a report on the remaining trial is currently in preparation. We were able to include data for this trial, however, by correspondence with and permission from study authors. In consultation with CCDAN, we have since divided the original review into three separate reviews: the present review which focuses on pharmacological interventions for adults, a second review on psychosocial interventions for adults, and the third on interventions for children and adolescents. As these 10 trials evaluated psychosocial rather than pharmacological interventions, they are included in the related two reviews.

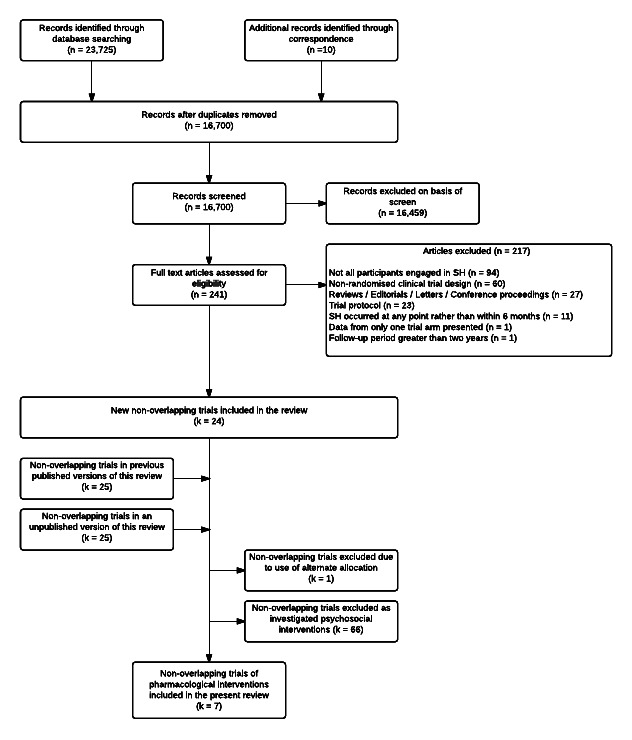

After deduplication, the initial number was reduced to 16,700. Of these, 16,459 were excluded after screening, whilst a further 217 were excluded after reviewing the full texts (Figure 1).

1.

Search flow diagram of included and excluded trials.

Included studies

In the previous versions of this review (Hawton 1998; Hawton 1999; NICE 2011), seven trials of pharmacological interventions for SH patients were included. The present update failed to locate any additional trials of pharmacological agents. The present review therefore includes seven non‐overlapping trials (Battaglia 1999; Hallahan 2007; Hirsch 1982; Lauterbach 2008; Montgomery 1979; Montgomery 1983; Verkes 1998). No further reports provided additional information on these trials.

Two of the trials have not been published (Montgomery 1979Hirsch 1982). Unpublished data were obtained from study authors for three of the trials (Battaglia 1999; Hallahan 2007; Verkes 1998.

Two ongoing trials of pharmacological interventions were also identified (see Characteristics of ongoing studies section for further information on these trials).

Design

Of the seven trials, all were described as randomised controlled trials. All employed a simple randomisation procedure based on individual allocation to the intervention and control groups.

Participants

The included trials comprised a total of 546 participants. All had engaged in at least one episode of SH in the six months prior to randomisation.

Participant characteristics

Of the five trials that recorded information on age, the average age of participants at randomisation was 35.3 years (SD 3.1). Two trials included a small number of adolescent participants (i.e., under 18 years of age) but the precise number was not recorded in either trial (Hallahan 2007; Hirsch 1982). Of the six trials that reported information on gender, the majority of participants were female (63.5%), reflecting the typical pattern for SH (Hawton 2008).

Diagnosis

A history of SH prior to the index episode (i.e., multiple episodes of SH) was a requirement for participation in five trials (Battaglia 1999; Hallahan 2007; Lauterbach 2008; Montgomery 1979; Montgomery 1983). In one trial, almost one‐third (30.0%) of participants had a history of multiple episodes (Verkes 1998) whilst in the remaining trial the proportion was not reported (Hirsch 1982). Only one trial included participants who had made a "suicide attempt" (i.e., with evidence of suicidal intent; Lauterbach 2008) whilst in two others, although only those who made a "suicide attempt" were eligible to participate, it is unclear whether all participants intended to die as a result (Battaglia 1999; Verkes 1998). The remaining trials did not provide any information on intent.

Information on the methods of SH for the index episode was not reported in five trials (Battaglia 1999; Hallahan 2007; Montgomery 1979; Montgomery 1983; Verkes 1998). In one trial, only those participants who had engaged in self‐poisoning with either over‐the‐counter or prescription drugs (i.e., not illicit substances or poison) were eligible to participate (Hirsch 1982), whilst in the remaining trial (Lauterbach 2008) a variety of methods were used, including: self‐poisoning (73.2%), self‐injury (14.4%), jumping from a height (2.5%), and attempted hanging, attempted shooting, or attempted drowning (5.0%). The methods used by the remaining 4.9% of participants in this trial were not reported.

Co‐morbidities

Information on current psychiatric diagnoses were reported in five trials (see Table 5). In these trials, the most common psychiatric diagnoses were for borderline personality disorder (k = 3, mean 78.4%) and other personality disorder (k = 3, mean 52.0%). One trial included a high proportion of participants diagnosed with major depression (76.0%; Lauterbach 2008).

1. Major categories of psychiatric diagnoses in included studies.

| Reference | Psychiatric Diagnosis1 | |||||||||

| MDD n (%) |

Any Mood Disorder n (%) |

AD n (%) |

PTSD n (%) |

AUD n (%) |

DUD n (%) |

SUD n (%) |

Adjustment Disorder n (%) |

BPD n (%) |

PD n (%) |

|

| Battaglia 1999 | 33 (57.9) | 11 (19.0) | 33 (58.0) | 16 (28.0) | 8 (14.0) | 49 (85.0) | 2 | |||

| Hallahan 2007 | 35 (71.4) | 40 (81.6) | ||||||||

| Hirsch 19823 | ||||||||||

| Lauterbach 2008 | 127 (76.0) | 8 (4.8) | 12 (7.2) | 14 (8.4) | 32 (19.2) | 131 (42.7) | ||||

| Montgomery 19793 | ||||||||||

| Montgomery 1983 | 30 (78.9) | 12 (31.6) | ||||||||

| Verkes 1998 | 29 (31.9) | 4 (4.4) | 40 (43.9) | 19 (20.9) | ||||||

MDD: major depression disorder; AD: anxiety disorder; PTSD: post‐traumatic stress disorder; AUD: alcohol use disorder; DUD: drug use disorder; SUD: substance use disorder; BPD: borderline personality disorder; PD: any other personality disorder (not including borderline personality disorder).

1 All diagnoses represent current rather than lifetime diagnoses. Percentages for any one trial may be greater than 100% due to comorbidity.

2 As participants could be diagnosed with more than one psychiatric diagnosis, the absolute number of participants diagnosed with any other personality disorder in this trial is unclear.

3 No information on psychiatric diagnoses reported.

Details on comorbid diagnoses were reported in one trial (Lauterbach 2008). For this trial, the most common comorbidity was for any personality disorder (33.5%), followed by substance use disorder (8.4%), and any anxiety disorder (7.2%). In a second trial, 25.3% of the sample were diagnosed with more than one psychiatric disorder from the following: dysthymia, any anxiety disorder, any dissociative disorder, alcohol abuse, any adjustment disorder, and any depressive disorder (Verkes 1998). However, the proportion diagnosed with each comorbid condition was not provided.

Setting

Of the seven independent RCTs included in this review, three were from the UK (Hirsch 1982; Montgomery 1979; Montgomery 1983), and one was from each of the USA (Battaglia 1999), Germany (Lauterbach 2008), the Netherlands (Verkes 1998) and the Republic of Ireland (Hallahan 2007). Although all participants were identified following a hospital admission for SH, five trials did not clearly specify if treatment was delivered on an inpatient or outpatient basis. Two trials were described as being conducted in an outpatient setting (Lauterbach 2008; Verkes 1998).

Interventions

The trials included in this review investigated the effectiveness of various pharmacological agents:

Newer generation antidepressants (mianserin, nomifensine, paroxetine) versus placebo (Hirsch 1982; Montgomery 1983; Verkes 1998).

Antipsychotics vs. placebo (Montgomery 1979).

Antipsychotics vs. comparator drug/dose (Battaglia 1999).

Mood stabilisers (lithium) vs. placebo (Lauterbach 2008).

Natural products (omega‐3 essential fatty acid; n‐3EFA) vs. placebo (Hallahan 2007).

Outcomes

All trials reported information on the primary outcome, repetition of SH. In two trials this was based on self‐reported information (Battaglia 1999; Lauterbach 2008), and in two further trials on re‐presentation to hospital (Hallahan 2007; Hirsch 1982). For the remaining three trials the source of information for this outcome was unclear (Montgomery 1979; Montgomery 1983; Verkes 1998).

Treatment adherence was assessed using pill counts (Hallahan 2007; Verkes 1998). Depression was assessed using the BDI in two trials (Hallahan 2007; Verkes 1998) or the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS; Hamilton 1960) in two further trials (Hallahan 2007; Lauterbach 2008). Hopelessness was assessed using the BHS (Lauterbach 2008; Verkes 1998). Suicidal ideation was assessed using either the sub‐scale of the Overt Aggression Scale (Hallahan 2007) or the BSS (Lauterbach 2008). It was unclear how suicide was assessed in any of the included trials. No trial reported information on problem‐solving.

Excluded studies

A total of 217 articles were excluded from this update: 94 were excluded because not all patients engaged in SH; 60 used a non‐randomised clinical trial design; 27 were reviews, editorials, letters to the editor, or conference proceedings; 23 were trial protocols; 11 were excluded as SH could have occurred at any point rather than within six months of randomisation; and one each were excluded either because only data from one trial arm were presented (however, a related publication in which data for both the intervention and control arms were presented was eligible for inclusion), or because the data reported in the article were for a period beyond two years (however, articles reporting data for earlier follow‐up periods for this trial were eligible for inclusion).

Details on the reasons for exclusion of 12 trials clearly related to pharmacological interventions for suicidality can be found in the Characteristics of excluded studies section.

Ongoing studies

Two ongoing trials of pharmacological interventions, one of oral lithium (Liang 2014) and one of oral ketamine (Sharon 2014), were identified. Full details of these trials are provided in the Characteristics of ongoing studies section.

Studies awaiting classification

There were no potentially eligible trials which have not been incorporated into the review.

Risk of bias in included studies

Summaries of the overall risk of bias for the included trials are presented in Figure 2 and Figure 3. Risk of bias for each included trial is also considered within the text of the review.

2.

Risk of bias graph: Review authors' judgements for each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included trials.

3.

Risk of bias summary graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included trial.

Sequence generation

Of the seven independent trials, all used random allocation. The majority (k = 4; 57.1%) were rated as having an unclear risk of bias as no information on the method used to generate the random sequence was provided. Three trials were rated as being at low risk of bias: two used a computerised program to generate the random sequence (Hallahan 2007; Lauterbach 2008) whilst the third used alternate allocation of identical blister packs to randomly assign participants to the active or placebo groups (Verkes 1998).

Allocation concealment (selection bias)

Information on allocation concealment was not provided in the majority of trials, earning them a rating of unclear risk (k = 5; 71.4%). Two trials were rated as being at low risk of bias as the random sequence was generated by an offsite researcher (Verkes 1998) or a third party researcher working independently from the trial team (Hallahan 2007). For the latter trial, moreover, additional attempts were made to prevent participants from guessing to which treatment group they had been allocated by adding the taste of the experimental medication to the placebo (Hallahan 2007).

Blinding (performance bias and detection bias)

Blinding was assessed separately for participants, clinical personnel, and outcome assessors.

Blinding of participants

Blinding of participants was classified as resulting in a low risk of bias for all trials included in this review as participant blinding was maintained through the use of identical capsules or blister packs for both the active agent and placebo arms.

Blinding of personnel

The majority of trials in this review were rated as being at low risk (k = 4; 57.1%) as personnel blinding was maintained through the use of identical capsules or blister packs for both the active agent and placebo arms (Battaglia 1999; Hallahan 2007; Montgomery 1983; Verkes 1998). The remaining three trials were rated as at being at unclear risk of bias. For two, no information on personnel blinding was provided (Hirsch 1982; Montgomery 1979). For one trial, blinding could not be maintained in all cases due to the occurrence of serious suicidal behaviour or insufficient treatment adherence (Lauterbach 2008).

Blinding of outcome assessors

Four trials were rated as being at low risk of bias (Battaglia 1999; Lauterbach 2008; Montgomery 1979; Montgomery 1983) as outcome assessors were blind to treatment allocation. For the remaining three trials (Hallahan 2007; Hirsch 1982; Verkes 1998) no information on blinding of outcome assessors was provided. These three trials were therefore rated as being at unclear risk of bias for this item.

Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias)

Three trials reported conducting analyses on an intention‐to‐treat basis. Two did not report any further details on the method used to conduct intention‐to‐treat analyses (Lauterbach 2008; Verkes 1998) but as all participants were included in the analyses, these trials were nonetheless classified as being at low risk. One used the last observation carried forward method (Hallahan 2007), which we understand may introduce bias (Engles 2003), and so was classified as being at unclear risk of bias for this item. A further trial was rated as being at unclear risk of bias for this item as no details on incomplete outcome reporting were provided (Hirsch 1982). Three trials used per protocol analyses (Battaglia 1999; Montgomery 1979; Montgomery 1983). As there was a greater than 0% drop‐out rate for these three trials, all were rated as having high risk of bias for this item.

Selective reporting (reporting bias)

As the review authors did not have access to trial protocols for the trials included in this review, it is difficult to assess the degree to which selective outcome reporting could have occurred. Consequently the majority of trials were classified as being at unclear risk for this item (k = 5; 71.4%). For two trials, numerical data for non‐significant outcomes were not reported (Hirsch 1982; Verkes 1998).These trials were therefore rated as at being at high risk of bias for this item.

Other potential sources of bias

For one trial, significant imbalances between the active and placebo arms in terms of history of multiple "suicide attempts", personality disorder diagnosis, and scores on the Suicide Intent Scale for the index attempt were apparent (Lauterbach 2008). As in all cases this imbalance was suggestive of worse prognosis for the intervention group, this trial was rated as being at high risk of bias for this item. The remaining six trials were classified as having low risk of bias for this item as no additional sources of bias were apparent.

Few trials used systematic means to investigate whether participants were able to guess if they had been allocated to the active or placebo arm. Only one (Hallahan 2007) questioned participants at the conclusion of the trial, however, this information was not presented in the trial report.

The source of funding was not indicated in three trials (Hirsch 1982; Montgomery 1979; Montgomery 1983). In two, funding was jointly received from a pharmaceutical company and a government department (Lauterbach 2008; Verkes 1998), in a further trial funding was received from both government and university sources (Battaglia 1999), and for the remaining trial, funding was exclusively received from a university source (Hallahan 2007).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4

As only newer generation antidepressants were evaluated against placebo in more than one non‐overlapping trial, meta‐analyses were only undertaken for this intervention.

Although antipsychotics were also evaluated in more than one independent trial, one used placebo as the comparator (Montgomery 1979) whilst the second used the intervention antipsychotic in an ultra‐low dosage as the comparator (Battaglia 1999). We therefore think it is inappropriate to pool these trials and have therefore analysed them separately. All other drug classes, which were evaluated in only single trials, are reported in the text.

There were no trials of tricyclic antidepressants, other antidepressants (e.g., MAOIs), antiepileptics, nor of other pharmacological agents (e.g., benzodiazepines, ketamine).

Comparison 1: newer generation antidepressants versus placebo

Three trials evaluated the effectiveness of different newer generation antidepressants (NGAs) in patients admitted to general hospital facilities following either self‐poisoning or attempted suicide. The first compared 30‐60 mg mianserin or 75‐150 mg nomifensine against placebo (N = 114; Hirsch 1982), the second compared 30 mg mianserin against placebo (N = 58; Montgomery 1983), whilst the third compared 40 mg paroxetine per day plus weekly/fortnightly supportive psychotherapy to placebo and supportive psychotherapy (N = 91; Verkes 1998). We acknowledge that these antidepressants are from different drug classes (heterocyclic, SSRI, and NDRI respectively); however, we have combined results for these agents into one comparison in order to address the question of whether antidepressant treatment using NGAs might be of general benefit in this patient population. We have also sub‐grouped the individual drugs in a post hoc analysis.

Primary outcome

1.1 Repetition of SH

There was no evidence of a significant treatment effect for mianserin or nomifensine at 12 weeks (15/76 versus 6/38; OR 1.31, 95% CI 0.46 to 3.71; k = 1; N = 114; Hirsch 1982) or for mianserin at six months (8/17 versus 12/21; OR 0.67, 95% CI 0.18 to 2.41; k = 1; N = 38; Montgomery 1983). In the trial involving paroxetine with adjunct psychotherapy, furthermore, there was also no evidence of a significant treatment effect at 12 months (15/46 versus 21/45; 95% OR 0.55, 0.24 to 1.29; k = 1; N = 91; Verkes 1998).

A post hoc analysis was performed to assess repetition for all three trials at the last follow‐up (i.e., 12 weeks (Hirsch 1982), six months (Montgomery 1983), and 12 months ( Verkes 1998). Again, there was no evidence of a significant treatment effect between groups (Analysis 1.1; OR 0.76, 95% CI 0.42 to 1.36; k = 3; N = 243). The quality of evidence, assessed using the GRADE criteria, was low (see Table 1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Newer generation antidepressants versus placebo, Outcome 1: Repetition of SH at last follow‐up

To assess the efficacy of each NGA drug, the intervention arms in Hirsch 1982 were separated into nomifensine vs. placebo (n = 76) and mianserin vs. placebo (n = 76). There was no evidence of a significant difference between drugs (Analysis 1.2; test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 1.25; df = 2; p = 0.53; I² = 0%).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Newer generation antidepressants versus placebo, Outcome 2: Repetition of SH at last follow‐up (by NGA drug)

Secondary outcomes

1.2 Treatment adherence

Data on treatment adherence was reported in one trial (Verkes 1998), however no numerical data for treatment adherence were reported. Instead the trial authors state that "...analysis of capsule counts at each visit revealed no statistically significant differences between treatments" (p.545), and that "...levels of platelet serotonin were not substantially decreased at week two in five patients, indicating doubtful adherence, and showed a manifest increase following a previous definite decrease in four other patients—at week 8 (n = 2) and week 52 (n = 2)" (p.545).

1.3 Depression

Two trials reported outcome data for depression (Verkes 1998; Hirsch 1982). In Verkes 1998, however, no numerical data were reported. Instead the trial authors state there was "...no significant treatment effect..." for this outcome (p.545). Also, although mean scores on the HDRS were reported by Hirsch 1982, insufficient information was provided to enable calculation of accompanying SDs via imputation using the formula outlined by Townsend 2001.

1.4 Hopelessness

Information on hopelessness was reported in one trial (Verkes 1998). Once again, however, no numerical data were reported. Instead the trial authors state there was also "...no significant treatment effect..." for this outcome (p.545).

1.5 Suicidal ideation

No data available.

1.6 Problem‐solving

No data available.

1.7 Suicide

Numbers of suicides during follow‐up were available for two trials (Hirsch 1982; Verkes 1998). In the first, no participant died by suicide during the six month follow‐up period (Hirsch 1982). In the second, one suicide occurred in the control group by the 12 month follow‐up period; however, there was no evidence of a significant treatment effect for NGAs on suicide in this trial (0/46 versus 1/45; OR 0.32, 95% CI 0.01 to 8.04; k = 1; N = 91).

Comparison 2: antipsychotics versus placebo or other comparator drug/dose

The effectiveness of 'prophylactic' injections of the antipsychotic flupenthixol compared to placebo was investigated in one small trial of patients admitted to a general hospital following a "suicidal act" (N = 37; Montgomery 1979). A second trial investigated the effectiveness of low dose (12 mg) fluphenazine compared to ultra‐low dose (1.5 mg) fluphenazine in individuals admitted to an emergency psychiatric unit following a suicide attempt (N = 58; Battaglia 1999). The authors of this trial state that "[t]he 'ultra‐low' (1.5 mg) was chosen to represent the extreme low end of possible pharmacologic effect for fluphenazine treatment" (p.363). However, because the comparator in these two trials was different (i.e., placebo in Montgomery 1979 and ultra‐low dose fluphenazine in Battaglia 1999) we have not combined the results of these two trials in a meta‐analysis.

Primary outcome

2.1 Repetition of SH

A significant treatment effect for flupenthixol was found for repetition of SH in the six months following trial entry (3/14 vs. 12/16; OR 0.09, 95% CI 0.02 to 0.50; k = 1; N = 30), although the overall quality of evidence was very low (see Table 2).