Abstract

Esophageal cancer (EC) is one of the most common cancers with high morbidity and mortality rates. EC includes two histological subtypes, namely esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) and esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC). ESCC primarily occurs in East Asia, whereas EAC occurs in Western countries. The currently available treatment strategies for EC include surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, molecular targeted therapy, and combinations thereof. However, the prognosis remains poor, and the overall five-year survival rate is very low. Therefore, achieving the goal of effective treatment remains challenging. In this review, we discuss the latest developments in chemotherapy and molecular targeted therapy for EC, and comprehensively analyze the application prospects and existing problems of immunotherapy. Collectively, this review aims to provide a better understanding of the currently available drugs through in-depth analysis, promote the development of new therapeutic agents, and eventually improve the treatment outcomes of patients with EC.

KEY WORDS: Drug combination, Esophageal adenocarcinoma, Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, Immune therapy, Molecular targeted therapy

Graphical abstract

Esophageal cancer (EC) is one of the most common cancers worldwide. This review summarizes the latest developments in chemotherapy, molecular targeted therapy, and immunotherapy for EC.

1. Introduction

Esophageal cancer (EC) is the eighth most common cancer and the sixth most common cause of cancer-related mortality and the five-year overall survival rate is relatively low. Based on pathological characteristics, EC is typically categorized as esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) and esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC)1,2. The characteristics and causes of EC may vary based on region or ethnicity. For example, in China, ESCC is the main EC subtype with a high incidence, but it is not significantly related to smoking. In contrast, in South America, smoking and drinking are the major risk factors for ESCC1,3,4. Compared to ESCC, EAC is relatively common in Western countries. Patients with EAC exhibit similar features to those of liver cancer, lung cancer, and pancreatic cancer; the five-year overall survival rate for EAC is only 16%, and the median survival time is less than one year5,6. EAC is usually associated with obesity and gastroesophageal reflux disease7. Additionally, Barrett's esophagus is a recognized risk factor and the first step in the progression of EAC. Gastroesophageal reflux leads to the development of BE, which can be tracked through histological and genetic changes8.

The progression of ESCC typically includes the following stages: simple epithelial hyperplasia, dysplasia, pre-invasive cancer, invasive cancer, and metastatic cancer9. Recent studies on ESCC treatment have shown that multiple molecular targets, including cAMP-responsive element binding protein, gremlin1, latent transforming growth factor β binding protein 1, ETS2, and regulator of cullin-1, are essential for the occurrence and development of ESCC; thus, these may be used as therapeutic targets10, 11, 12, 13, 14. In addition, calcium signaling pathway plays an important role in ESCC, and ORAI1-mediated calcium signaling may be the most promising target for treating EC15,16. The use of natural quinones and flavonoids isolated from medicinal plants have demonstrated promising results in preclinical and clinical studies on ESCC; however, extensive evaluation of their clinical application is still in progress17, 18, 19.

The efficacy of radiotherapy on ESCC is not high owing to the overexpression of tribbles pseudokinase 3 and its interaction with TAZ (transcriptional coactivator with PDZ-binding motif), which hinders β-transducin repeat-containing protein-mediated TAZ ubiquitination and degradation20. Although chemotherapy and surgical resection have contributed to significant progress in ESCC treatment, ESCC remains prone to relapse, metastasis, and development of resistance after treatment, resulting in a poor prognosis. The development of chemotherapy resistance is a multifactorial process. Many studies have demonstrated that apoptosis, autophagy disorder, enhanced DNA repair, epithelial–mesenchymal transition, inactivation of drug metabolism enzymes, and changes in the expression or activity of membrane transporters are closely related to the development of drug resistance21.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) also play a vital role in EC-associated multidrug resistance (MDR), thereby affecting the efficacy of EC treatment22. MiRNAs regulate gene expression at the post-transcriptional level in various cellular processes, serving as tumor suppressors or oncogenes. For example, miR-135a inhibits the SMO/HH axis and plays an inhibitory role in EC cell migration and invasion. Similarly, the long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) KLF3-AS1 inhibits ESCC cell migration and invasion by impairing miR-185-5p-mediated downregulation of KLF323,24.

ESCC is characterized by a high mutation rate in TP53, which plays a critical role in the DNA damage response and is regulated by checkpoint kinase 1 (CHK1). Therefore, treatment strategies based on CHK1 inhibitor combinations may be very promising25. In recent years, various molecular targeted therapies for ESCC have emerged, including the application of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) or fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) inhibitors. However, drug resistance persists26, suggesting an urgent need for development of new treatment options.

For most patients with EC, the current treatment is chemotherapy, which causes a series of dose-limiting toxicities27. Targeted therapies have achieved unprecedented development in the treatment of various cancers; however, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network of the United States has only recommended trastuzumab (targeting human epidermal growth factor receptor 2, HER2) and ramucirumab [a vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 (VEGFR-2) inhibitor] for treatment of patients with EC28. Immunotherapy, which includes the application of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs)/immunomodulators, therapeutic vaccines, monoclonal antibodies, and adoptive cellular immunotherapy, is a new method in the treatment of EC29,30. Importantly, ICIs were proven effective in treating melanoma and non-small cell lung cancer, and have shown promising results in advanced ESCC treatment31. Although there are many treatment options for EC, effective treatment remains limited.

In this review, we summarize the latest advances in chemotherapy drugs, molecular targeted drugs, and immunotherapy drugs, and provide new insights for the development of more effective agents to treat patients with EC.

2. Chemotherapy drugs for EC

As the first-line treatment for EC, chemotherapy has the advantages of inhibiting tumor growth and preventing distant metastasis. The most widely available chemotherapy drugs for EC include cisplatin (DDP), 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), and doxorubicin (Dox), which are discussed below.

2.1. DDP and 5-FU

Clinically, DDP-based chemotherapy is the common first-line treatment for EC, and the initial response is usually obtained in patients with recurrence and metastasis after surgery. In particular, the combination chemotherapy comprising DDP and 5-FU has been introduced globally as an ESCC treatment plan32,33. Multiple combined drug treatment regimens are shown in Table 134, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43 and Table 2.

Table 1.

Commonly used chemotherapy drugs and their combined treatment options.

| Treatment regimen | Cancer type | Mechanism | Status | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cisplatin-based combination therapy | ||||

| AP water extract, cisplatin, and 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) | ESCC | AP water extract reduces the side effects caused by chemotherapy drugs and inhibits metastasis-related factors such as MMP2, MMP9, TM4SF3, and CXCR4. | In vitro and animal studies | 34 |

| 5-FU and cisplatin | ESCC | HER2-positive, not sensitive to 5-FU/cisplatin. | In vitro and animal studies | 35 |

| VE-822 and cisplatin | ESCC | In ESCC cells, especially those with ataxia-telangiectasia mutation, VE-822 enhances the sensitivity of tumor cells to cisplatin. | In vitro and animal studies | 36 |

| Tiplaxtinin and cisplatin | ESCC | The combination of tiplaxtinin and cisplatin promotes apoptosis, increases the accumulation of reactive oxygen species, and reduces tumor growth. | In vitro and animal studies | 37 |

| 5-FU-based combination therapy | ||||

| β-Carotene and 5-FU | ESCC | Combined use of β-carotene and 5-FU induces apoptosis, down-regulates BCL-2 and PCNA, and up-regulates BAX and caspase-3. Effectively reduces the protein levels of CaV-1, p-AKT, p-NF-κB, p-mTOR, and p-P70S6K in ECA109 cells. | In vitro and animal studies | 38 |

| CA3 and 5-FU | EAC | CA3 inhibits the YAP/TEAD transcription process. Combined treatment reduces YAP1, SOX9, and Ki67 expression in mouse models. | In vitro and animal studies | 39 |

| BAY1143572 and 5-FU | EAC | Combination treatment reduces MCL-1 expression. | In vitro and animal studies | 40 |

| Hesperetin and 5-FU | ESCC | Combination treatment effectively induces cell apoptosis, down-regulates BCL-2, and up-regulates BAX, cleaved caspase-3, and cleaved caspase-9. | In vitro and animal studies | 41 |

| Puerarin and 5-FU | ESCC | Combined use significantly inhibits cell proliferation and induces apoptosis. | In vitro and animal studies | 42 |

| ABT-263 and 5-FU | ESCC | Combination treatment synergistically promotes apoptosis and inhibits the expression of stemness genes. | In vitro and animal studies | 43 |

Table 2.

Evaluation of representative clinical trials of cisplatin-based combination therapy.

| Treatment regimen | Cancer type | Clinical phase | Result | Clinical trials.gov identifier |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cisplatin+radiation therapy | ||||

| Pemetrexed, cisplatin, and radiation therapy | Esophageal or gastroesophageal junction cancer | I | Not provided | NCT00701857 |

| PPX with cisplatin, and radiation therapy | EC | II | 12 of 37 patients (32%) had complete pathological remission | NCT00522795 |

| Cisplatin+radiation therapy+surgery | ||||

| Cisplatin, irinotecan, celecoxib, radiation therapy, and surgery | EC | II | Not provided | NCT00137852 |

| Irinotecan, cisplatin, radiation therapy, plus surgery | EC | II/III | Not provided | NCT00160875 |

| Fluorouracil, cisplatin, cetuximab, radiation therapy, plus surgery | EC | I/II | Not provided | NCT00544362 |

| Cisplatin, 5-FU, radiation therapy, and surgery | EC | III | Not provided | NCT00003118 |

| Cisplatin+antibody | ||||

| Epirubicin, cisplatin, capecitabine+matuzumab | EC, Gastric cancer | II | PFS was 4.8 months | NCT00215644 |

| Paclitaxel, cisplatin, cetuximab, and radiation therapy | EC | III | Overall survival (24-month rate reported) was 44.9% | NCT00655876 |

| 5-FU/cisplatin, radiation therapy plus cetuximab | EC | II | 2-year survival rate was 71% | NCT01787006 |

| Cetuximab, cisplatin, and irinotecan | EC, Gastric cancer | II | 1 of 16 patients (6%) had a partial response | NCT00397904 |

| Docetaxel, cisplatin, 5-FU, bevacizumab, leucovorin | EC, Stomach cancer | II | 6-month PFS was 79% | NCT00390416 |

| Docetaxel, cisplatin, irinotecan, and bevacizumab | EC, Stomach cancer | II | 10-month PFS was 40% | NCT00394433 |

| Cisplatin+other drugs | ||||

| G17DT immunogen, cisplatin, 5-FU | EC, Gastric cancer | III | Not provided | NCT00020787 |

| Paclitaxel and cisplatin | ESCC | II | Not provided | NCT02133612 |

| Docetaxel, cisplatin, leucovorin, and 5-FU | Esophageal, Gastroesophageal, Gastric cancer | II | 2-year survival rate was 9.5% | NCT01715233 |

| S1 combined with cisplatin | ESCC | II | Not provided | NCT01854749 |

In ESCC cell lines, the efficacy of DDP is related to the regulation of certain genes. DDP treatment enhances the expression of E2F1, which directly binds to the miR-26b promoter, resulting in miR-26b upregulation. However, once the E2F1/miR-26b pathway is disrupted, the sensitivity of ESCC cells to DDP decreases44. In contrast, ESCC sensitivity to DDP is enhanced through induction of Ca2+-mediated apoptosis and inhibition of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT pathway45,46. In addition, inhibition of B lymphoma Mo-MLV insertion region 1 homolog and melanoma nuclear protein 18 can also increase the sensitivity of EC cells to DDP by suppressing c-MYC47. The emergence of resistance to DDP treatment may be attributed to the influence of multidrug resistance (MDR)48.

5-FU is used as the first-line treatment for patients with ESCC. However, as its dose increases, toxicity, drug resistance, and other side effects also increase; therefore, single-drug chemotherapy with 5-FU is no longer suitable for treating ESCC. In order to improve the therapeutic efficacy of 5-FU and reduce its adverse reactions, a variety of 5-FU-based drug combinations are currently used (Table 1). In particular, as miRNAs have regulatory activities in many cellular processes, including cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, and drug resistance. For example, miR-29c interacts with the 3′UTR of F-box only protein 31, inhibits its expression, and activates the downstream P38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway in ESCC, which can overcome 5-FU chemoresistance in vitro and in vivo49. Furthermore, emerging evidence suggests that miRNAs are dysregulated in EC. MiR-221 knockdown in 5-FU-resistant cells can reduce cell proliferation, increase cell apoptosis, restore chemosensitivity, and inactivate the WNT/β-catenin pathway through changes in dickkopf 2 expression50.

Certain lncRNAs, containing at least 200 nucleotides, play crucial roles in regulating the formation and progression of EC. For example, silencing BDH2 or lncRNA TP73-AS1 increases the sensitivity of EC cells to 5-FU and DDP51. Moreover, lncRNA LINC00261 can increase the sensitivity of EC cells to 5-FU-based chemotherapy by regulating the methylation of dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase52. The efficacy of 5-FU in EC is associated with the expression of certain genes or proteins. For example, as the expression level of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E (eIF4E) in EC tissues is relatively high, its inhibition will affect the growth and survival of EC cells, thereby enhancing the efficacy of 5-FU53.

2.2. Dox and other chemotherapy drugs

Dox is a widely used antitumor drug that produces reactive oxygen species (ROS), causing DNA damage and destroying the double-layer membrane structure54. To improve the efficacy of Dox in EC treatment, various delivery systems have been developed. Jin et al.55 encapsulated polypyrrole and Dox in the core of hollow TaOx nanoparticles and incorporated the near-infrared fluorescent dye NIRDye800 in the shell. The obtained nanoparticles may have great potential for the treatment of EC; however, the tumor-targeting mechanism and long-term biocompatibility need to be further explored in large animal models. Zhang et al.56 developed a new type of hollow carbon sphere with high drug-loading capacity, low cytotoxicity, and good immunocompatibility. Owing to the prolonged circulation period and enhanced permeability and retention, Dox was efficiently delivered to the tumor site and showed a significant inhibitory effect on tumor growth in esophageal xenograft cancer models. Dai et al.57 reported that PCL-Plannick micelles markedly increase the absorption and accumulation of Dox in EC cells. In addition, a significant synergistic therapeutic effect was observed when combined with miR-34a. Notably, Dox can also cause adverse reactions during EC treatment. However, Tajaldini et al.54 found that the combination of natural product orange peel extract and naringin decreased the side effects of Dox in EC stem cell-derived xenograft mouse models.

Paclitaxel-based radiochemotherapy is another treatment for advanced EC. The combination of heavy carbon ion beam irradiation and docetaxel posess a synergistic effect on EC, thereby representing a promising treatment option for locally advanced ESCC58. Docetaxel toxicity and the development of drug resistance limit the extensive clinical application of this agent; resistance is attributed to overexpression of the P-gp efflux pump and resistance to apoptosis59. In paclitaxel-resistant EC109 cells (EC109/Taxol cells), jesridonin (JD) has an anti-MDR effect, through upregulating P53, cleaved-caspase-9, and cleaved-caspase-3 and downregulating procaspase-3 and procaspase-9. JD activates the mitochondrial-mediated intrinsic apoptosis pathway, thereby inducing EC109/Taxol cell apoptosis and effectively suppressing the growth of tumor xenografts with no obvious toxicity59. Thus, combination therapy is likely to overcome drug toxicity and resistance during ESCC treatment. For example, a combination of lapatinib and paclitaxel can significantly reduce the activation of phosphorylated EGFR and HER2 as well as the downstream molecules MAPK and AKT, thereby suppressing cell growth, inhibiting migration and invasion, and increasing cell apoptosis60. However, paclitaxel requires emulsification with a solvent to allow intravenous administration, which may cause hypersensitivity reactions in patients. Nano-albumin-bound paclitaxel (NAB-paclitaxel) is a water-soluble nanoparticle formulation that can partially neutralize the hydrophobicity of paclitaxel. During ESCC treatment, NAB-paclitaxel can increase the expression of mitotic spindle-associated phosphorylation, reduce the expression of proliferation-related molecules, and enhance cell apoptosis; thus, it exhibits stronger antitumor activity compared with the current standard chemotherapy drugs61.

Camptothecin is another promising antitumor drug. During the treatment of ESCC, gimatecan, a new form of oral camptothecin, inhibits the expression and bioactivity of topoisomerase I, induces DNA damage and S-phase arrest and causes apoptosis62.

3. Molecular targeted therapy

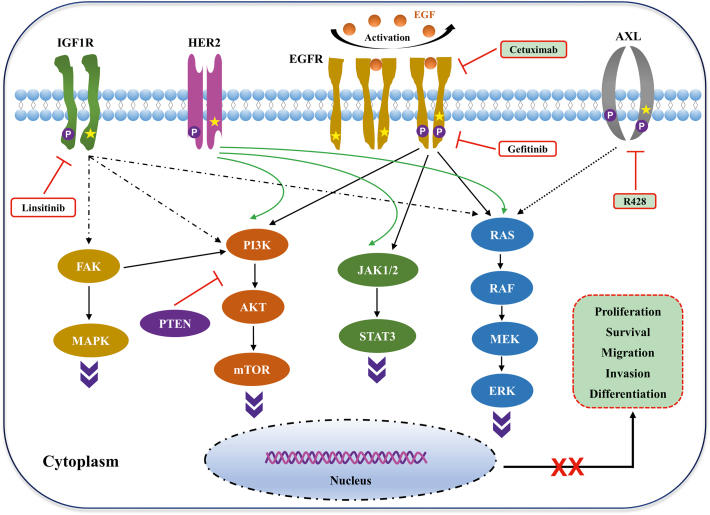

Clinical trials of molecular targeted therapy for EC are mainly based on targeting EGFR, HER2, and VEGF (Table 3). Fig. 1 shows a schematic diagram of molecular targeted therapy for EC. The progress of EC molecular targeted therapy is discussed in this section.

Table 3.

Evaluation of representative clinical trials of molecular targeted therapy for esophageal cancer.

| Treatment regimen | Cancer type | Clinical phase | Result | Clinical trials.gov identifier |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EGFR-targeted | ||||

| Icotinib | Adenocarcinoma of the gastroesophageal junction, EC | II | Completed | NCT01855854 |

| SCT200 | ESCC | I/II | Recruiting | NCT03817567 |

| Cetuximab | EC | II | Completed | NCT00096031 |

| Cetuximab, ECF, IC, FOLFOX | EC | II | Completed | NCT00381706 |

| Cetuximab, paclitaxel, carboplatin | EC, GC | II | Completed | NCT00439608 |

| Cetuximab plus radiation | Locally advanced thoracic middle-lower segment ESCC | II | Recruiting | NCT02123381 |

| HER2-targeted | ||||

| Pertuzumab, trastuzumab | EC | I/II | Completed | NCT02120911 |

| Pembrolizumab, trastuzumab, and chemotherapy | EC, GC | II | Recruiting | NCT02954536 |

| mFOLFOX6+trastuzumab+avelumab | GC and EAC | II | Recruiting | NCT03783936 |

| VEGF-targeted | ||||

| Bevacizumab | EC | I | Recruiting | NCT02072720 |

| Bevacizumab-IRDye800CW, Molecular fluorescence endoscopy platform | EC | I | Recruiting | NCT03558724 |

| Regorafenib, paclitaxel | Esophagogastric carcinoma | I/II | Completed | NCT02406170 |

| SHR-1210, apatinib plus radiation | ESCC | Not applicable | Recruiting | NCT03671265 |

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of molecular targeted therapy for esophageal cancer. Frequent genetic alterations in key signaling pathways in esophageal cancer, involving insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF1R), receptor tyrosine-protein kinase ERBB-2 (HER2), epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), and tyrosine-protein kinase receptor UFO (AXL). Drugs, such as linsitinib, cetuximab, and R428, or other agents can specifically inhibit the components of the IGF1R-, EGFR-, and AXL-associated pathways. Regulation of these signaling pathways affects the proliferation, survival, migration, invasion, and differentiation of tumor cells, thereby inhibiting tumor growth.

3.1. Drugs targeting EGFR

EGFR (also known as ERBB1), a member of the ERBB receptor tyrosine kinase family, is a transmembrane protein receptor that contains an extracellular ligand binding domain, a transmembrane domain, and an intracellular kinase domain63. Once activation of EGFR by its ligand (EGF), the extracellular domain dimerizes. Then, the intracellular domain dimerizes and subsequently promotes the activity of the intracellular kinase domain through self-phosphorylation, which in turn activates downstream molecules, thereby regulating cell proliferation, differentiation, and invasion. EGFR is overexpressed in most esophageal cancers and the overexpression of EGFR is more common in ESCC than in EAC64,65. Drugs targeting EGFR can be divided into two categories: 1) monoclonal antibodies, such as cetuximab and nimotuzumab, which specifically target the extracellular domain to block ligand binding and activation; and 2) small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), such as gefitinib and afatinib, which act on the intracellular domain.

3.1.1. Anti-EGFR monoclonal antibodies

3.1.1.1. Cetuximab

Cetuximab, which has high affinity for EGFR, competitively blocks ligand binding, inhibits tyrosine kinases and blocks intracellular signal transduction, thereby suppressing cell proliferation and angiogenesis, promoting cell apoptosis and enhancing antibody-dependent cytotoxicity66,67. In ESCC with EGFR amplification or overexpression, cetuximab exhibits remarkable therapeutic effects68. Accordingly, in order to improve the therapeutic efficacy of cetuximab, various drug combinations based on cetuximab are currently used (Table 469, 70, 71, 72, 73).

Table 4.

Cetuximab-based drug combination for esophageal cancer treatment.

| Treatment regimen | Cancer type | Mechanism | Status | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pingyangmycin and cetuximab | ESCC | Combined use, down-regulation of EGFR | In vitro and animal studies | 69 |

| Cisplatin and cetuximab | ESCC | Inhibition of EGFR signaling pathway | In vitro and animal studies | 70 |

| Cetuximab-IRDye700DX and trastuzumab-IRDye700DX | EAC | TKI-induced up-regulation of growth receptor. The combined targeting of EGFR and HER2 enhances the activity of NIR-tPDT | In vitro study | 71 |

| Cetuximab and trastuzumab | ESCC | Inhibition of AKT phosphorylation | In vitro and animal studies | 72 |

| Cetuximab and NVP-BGJ398 | ESCC | The synergistic antitumor effect is due to the inhibition of AKT phosphorylation | In vitro and animal studies | 73 |

In mesenchymal-like ESCC cells, EGFR signal transduction cannot be blocked, resulting in resistance to EGFR inhibitors. However, in epithelial ESCC cells, EGFR inhibitors promote differentiation, in which cetuximab exerts an antitumor effect74. Thus, although EGFR inhibitors have advantages in ESCC treatment, further exploration of their mechanism of action is critical.

3.1.1.2. Other anti-EGFR antibodies

Nimotuzumab is a humanized anti-EGFR monoclonal antibody that binds to the extracellular domain of EGFR and inhibits EGF binding75. Nimotuzumab can increase the radiosensitivity of ESCC cells and enhance the radiation response of KYSE30 cells in vitro, potentially through upregulation of insulin-like growth factor binding protein 3 through an EGFR-dependent pathway76. Sym004 is a 1:1 mixture of two chimeric IgG1 anti-EGFR monoclonal antibodies, mAb 992 and mAb 102477. ESCC cell line carrying EGFR amplification is more sensitive to Sym004, and its growth inhibitory effect is greater than that of cetuximab or panitumumab78. To improve the efficacy of EGFR-targeted antibodies in EC, a new antibody (denoted as PAN) was prepared. The PAN variable domain was fused to pseudomonas exotoxin A (PE38), forming the immunotoxin Ptoxin (PT). PT can inhibit the phosphorylation of EGFR and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK1/2), induce ROS accumulation by inhibiting the nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2/kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 regulator (NRF2/KEAP1) antioxidant pathway, and induce the regression of KYSE-450 tumor transplantation in nude mice79.

With the rapid development of biotechnology, antibody-based drug delivery systems, such as antibody–drug conjugate composed of antibody, linker, and small-molecule cytotoxic agent, are also used to treat EC. In this case, the specifically targeted antibody is connected to the cytotoxic drug through a linker. Hu et al.80 prepared an EGFR-targeted antibody drug conjugate (LR004-VC-MMAE), which exerted highly potent antitumor efficacy in an EC xenograft model.

3.1.2. Small molecule TKIs

Small molecule TKIs competitively bind to TKI phosphorylation sites in the intracellular domain of EGFR, blocking its interaction with ATP and inhibiting tyrosine phosphorylation and downstream signal transduction. Gefitinib is a selective and reversible EGFR-TKI that can block ATP binding to the activation site of EGFR-TK and prevent the transmission of downstream signals from the receptor, thereby exerting anti-apoptotic effects. However, EGFR mutations may change the sensitivity of ESCC cells to gefitinib. Knockdown of lncRNA prostate androgen-regulated transcript 1 (PART1) can effectively increase gefitinib-induced cell death, whereas elevated PART1 promotes the expression of BCL-2 in ESCC cells by competitively binding miR-129, thereby stimulating the development of gefitinib resistance81. However, inhibiting galectin-3 can enhance the sensitivity of TE-8 cells to gefitinib82. Significantly, Xu et al.83 reported that gefitinib caused adverse reactions, including diarrhea and vomiting.

Unlike other TKIs (such as gefitinib), afatinib (BIBW2992) is an irreversible inhibitor of the ERBB family and possesses antitumor activity. It can effectively inhibit cell proliferation by arresting G0/G1 phase and inducing ESCC cell apoptosis84,85. In particular, ESCC cells harboring EGFR or HER4 mutations are more suitable for targeted therapy with afatinib86.

Lincitinib is a selective and orally bioavailable insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor inhibitor. In ESCC cells, lincitinib can inhibit downstream AKT/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) and ERK signal transduction, while activating the phosphorylation of nuclear factor (NF)-κB P65. In addition, combined treatment with NF-κB transcriptional activity inhibitor JSH-23 can overcome ESCC resistance87. CI-1033 is a pan-erbB TKI that irreversibly inhibits the signal transduction of EGFR family members88. In ESCC cells co-expressing EGFR and HER2, CI-1033 can effectively inhibit cell growth and phosphorylation of MAPK and AKT89. Lapatinib is a reversible TKI targeting EGFR and HER2 tyrosine kinases that can effectively inhibit receptor phosphorylation and the activation of downstream signaling pathways (such as ERK1/2 and AKT)90. The combination of lapatinib and 5-FU for ESCC treatment can significantly reduce the phosphorylation of EGFR and HER2, thereby generating a synergistic antitumor effect91. Foretinib is a small-molecule kinase inhibitor that prevents hepatocyte growth factor (HGF)-induced c-MET phosphorylation. The combination of lapatinib and foretinib can be used as a treatment option for HER2-positive and MET-overexpressing EAC92.

3.2. Drugs targeting HER2

HER-2/neu is involved in multiple cellular processes, such as cell proliferation, apoptosis, migration, and angiogenesis. Studies have shown that HER-2/neu is overexpressed in EAC93. Trastuzumab is a recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody that targets the extracellular domain of HER2, and is currently one of the standard treatments for advanced EC94,95. An in vivo study showed that after three weeks of trastuzumab treatment, tumor weight, volume, microvessel density, and the number of lung and lymphatic metastases decreased96. In another in situ model of metastatic EC, HER2-targeted therapy markedly suppressed primary tumor growth and reduced lymph node metastasis97. However, trastuzumab use resulted in drug resistance in the HER-2 IHC2+/PIK3CA mutation model of EC98. In EAC, t-DARPP (DARPP-32 and its cancer-specific truncated variant) mediated the trastuzumab resistance99. In addition, the transforming growth factor (TGF)-β signaling pathway was activated in EAC cells that developed resistance to trastuzumab and pertuzumab. Therefore, the antitumor effect of trastuzumab and pertuzumab may be improved by using drugs that block the TGF-β signaling pathway100.

3.3. Drugs targeting VEGF

VEGF plays an important role in inducing the proliferation of vascular endothelial cells and the formation of new blood vessels. During tumorigenesis, new blood vessels are formed to provide oxygen and nutrients to the proliferating tumor cells and to promote cell migration. Targeting key molecules involved in angiogenesis has great potential in the treatment of locally advanced ESCC101. For instance, as the upregulation of VEGF-C is related to the development of EC, VEGF-C targeting has attracted the attention of many researchers102,103. VEGF-A also plays a key role in the development of EC; miR-126 and the VEGF-A 3′-UTR naturally complement each other, resulting in downregulation of VEGF-A in EC cells and eventually inhibiting the growth of EC104.

Many drugs are currently used to inhibit pro-angiogenic factors. For example, the monoclonal antibody bevacizumab binds to VEGF-A to prevent its interaction with VEGF receptors. Intratumoral injection of MAP4-siRNA and bevacizumab significantly inhibits the growth of ESCC cell-derived tumors in nude mice105,106. In addition, all-trans retinoic acid is used to inhibit the proliferation and migration of EC cells, which may be related to its inhibition of tumor angiogenesis involving VEGF107. During ESCC treatment, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT-3) inhibitor (static) downregulates the expression of VEGF and can also be used as an adjuvant for radiation therapy108.

3.4. Drugs targeting other molecules

During tumor development, the overexpression of tyrosine kinase receptor AXL plays a role in epithelial–mesenchymal transition109. AXL is also overexpressed in EAC, where it upregulates c-MYC by activating the AKT/β-catenin signaling pathway and further promotes epirubicin resistance. Suppression of c-MYC expression restores epirubicin sensitivity in AXL-dependent drug-resistant cells. Furthermore, the combination of AXL inhibitor R428 and epirubicin synergistically inhibited cell proliferation and tumor growth110. Mesenchymal–epithelial transition factor (c-MET) is a transmembrane receptor tyrosine kinase that can be activated by HGF and participates in the process of tumorigenesis, including cell growth, apoptosis, and angiogenesis111. In ESCC cell lines and tissues, several molecules related to the HGF/MET signaling pathway, such as MET, cyclin D1, and CDK4, are abnormally expressed112. AXL/c-MET selective inhibitors, R428 and carbotinib, inhibited the growth of ESCC cells and corresponding xenograft tumors113. Both mTOR, a member of the PI3K protein kinase family, and the serine/threonine protein kinase polo-like kinase 1 (PLK1), a member of the polo-like kinase family, are potential therapeutic targets. In ESCC cells, siRNA or PLK1 inhibitors can decrease mTOR activity. In particular, the combination of rapamycin and the PLK1 inhibitor BI 2536 shows stronger antitumor effects through synergistic blockade of the mTOR complex (mTORC1/mTORC2) cascade and activating S6 and 4E-BP1114. Another study demonstrated that targeting mTORC2 alone exhibited a strong inhibitory effect on EC cell growth115. In addition, metformin (a drug commonly used to treat type 2 diabetes) was also found to inhibit the PI3K/AKT/mTOR/PKM2 signaling pathway. In the ECA109 xenograft model, metformin significantly inhibited tumor growth. Therefore, the application of classic drugs that are used to treat specific diseases in EC treatment may be a new strategy116. CD147 is also highly expressed in EC tissues117. In vitro and in vivo studies have shown that the anti-CD147 antibody, matuzumab, can inhibit EC progression by activating effector cells and blocking the function of CD147118.

4. Immunotherapy

Generally, antigen-presenting cells, particularly dendritic cells, can recognize and phagocytize antigen-induced inflammation on the surface of tumor cells and present the resulting antigens to T or B lymphocytes to produce an adaptive response. However, tumor cells have developed a variety of strategies to escape immune attack119. Currently, the main immunotherapy options for EC are ICIs and tumor vaccines.

4.1. ICIs

In recent years, cancer immunotherapy has developed rapidly. Accordingly, it has been actively explored for EC treatment. As shown in Fig. 2, in particular, ICI-based therapy is a hot spot of current cancer research, mainly involving cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4), programmed death receptor 1 (PD-1), and programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1)120,121. The ongoing clinical trials of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors for the treatment of EC are shown in Table 5. In the tumor microenvironment, PD-L1 expressed by tumor cells binds to PD-1 expressed by tumor-infiltrating T lymphocytes, allowing tumor cells to escape immune attack and induce T-cell apoptosis122, 123, 124. PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor monotherapy for EC exhibited good antitumor activity and safety. Commonly used drugs include pembrolizumab, nivolumab, toripalimab, and camrelizumab122. Once the interaction between PD-1 and PD-L1 is blocked, the immune killing ability of T cells can be restored125. In addition, the dual blockade of PD-1/PD-L1 and TGF-β signaling pathways can synergistically restore the function of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells and enhance antitumor activity in vitro and in vivo126. In ESCC, the expression of PD-L1 is related to zinc finger E-box binding homeobox 1 (ZEB1) and epithelial–mesenchymal transition. The synergy of immune escape and epithelial–mesenchymal transition promotes the malignant development of tumors. Therefore, the ZEB1/PD-L1 signaling pathway is a promising therapeutic target for the treatment of ESCC127. Considering that a small molecule inhibitor of c-MYC, 10058-F4, can effectively regulate the expression of PD-L1, the expression level of c-MYC is closely related to that of PD-L1 in ESCC cell lines. Therefore, the combination of c-MYC inhibitors and PD-L-based immunotherapy may be a novel strategy for treating ESCC128.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of immunotherapy for esophageal cancer. Dendritic cells (DCs), macrophages, natural killer (NK) cells, T cells, and B cells are all involved in immunotherapy against esophageal cancer. DCs are antigen-presenting cells that upon activation by exogenous or endogenous factors, participate in the immune responses mediated by CD4+ T or CD8+ T cells. The SIRPa–CD47 interaction is very critical between macrophages and tumor cells. Drugs, such as antibodies, that specifically disrupt this interaction can suppress the growth of tumor cells. T cells or NK cells are modified to generate chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells or engineered NK cells, respectively, that can specifically kill tumor cells. After recruitment or activation, immune cells can play multifunctional roles in inducing tumor-cell apoptosis and death, thereby inhibiting tumor growth.

Table 5.

Evaluation of representative clinical trials of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors.

| Treatment regimen | Cancer type | Clinical phase | Status | Clinical trials.gov identifier |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teripalimab | EC | II | Recruiting | NCT04177875 |

| SHR-1210, apatinib plus radiation | EC | Not applicable | Recruiting | NCT03671265 |

| SHR-1210, radiation | Esophageal neoplasms, esophageal diseases, ESCC | II | Completed | NCT03187314 |

| SHR-1210, placebo, paclitaxel, cisplatin | EC | III | Recruiting | NCT03691090 |

| Toripalimab and chemoradiotherapy | EC | II | Recruiting | NCT04005170 |

| Sintilimab plus chemoradiation before surgery | ESCC | I | Recruiting | NCT03940001 |

| Sintilimab in combination with liposome paclitaxel, cisplatin and S-1 | ESCC | I/II | Recruiting | NCT03946969 |

| Camrelizumab, paclitaxel, cisplatin | ESCC | II | Recruiting | NCT04225364 |

| Pembrolizumab+chemoradiation | ESCC | II | Recruiting | NCT04435197 |

| HLX10, placebo | ESCC | III | Recruiting | NCT03958890 |

| Atezolizumab and chemoradiation | EC | II | Completed | NCT03087864 |

| Durvalumab and chemoradiation before surgery | Gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma, EAC | II | Recruiting | NCT02962063 |

| Durvalumab, tremelimumab | EAC | II | Recruiting | NCT04159974 |

| SHR-1316 and chemotherapy | ESCC | II | Recruiting | NCT03732508 |

| Camrelizumab | EC | II | Recruiting | NCT04286958 |

CTLA-4 (CD152) is another immune checkpoint molecule that is homologous to the T-cell costimulatory protein CD28; both molecules bind to B7-1 (CD80) and B7-2 (CD86)129. The expression level of CTLA-4 is significantly upregulated in EC130, and studies have been conducted to test the efficacy of treatments with CTLA-4 inhibitor alone or in combination with chemotherapy drugs131. However, drug resistance remains a major challenge for effective treatment. Since anti-CD47 therapy can enhance antitumor inflammation and T-cell recruitment in a dendritic cell-dependent manner, the combination of CD47-, PD-1-, and CLTA-4-targeted agents exhibits powerful therapeutic effects132. It should be noted that the use of ICIs may cause some adverse reactions, such as a decrease in the number of lymphocytes and systemic rash133. Collectively, these findings indicate that the development of ICI drugs may provide new avenues for EC treatment.

4.2. Tumor vaccines

Tumor vaccines utilize tumor cells or tumor antigens to induce specific cellular immunity and humoral immune responses, which can enhance the host's anticancer responses and thereby inhibiting tumor growth, metastasis and recurrence. For example, certain epitope peptides derived from tumor-associated antigens expressed in EC can be used to develop vaccines to extend patient survival period. Upregulated genes in lung cancer 10 (URLC10) is an antitumor antigen that is highly expressed in ESCC. URLC10-177 can be used to induce a specific immune response to treat ESCC. Vaccination with a therapeutic URLC10-177 peptide vaccine is expected to prolong survival period in patients with advanced EC134. The use of a vaccine composed of three peptides, namely TTK protein kinase (TTK), lymphocyte antigen 6 complex locus K (LY6K), and IGF-II mRNA binding protein 3, the median survival period of ESCC patients was 6.6 months. The vaccine produced positive clinical responses in 10 patients, exhibiting its safety and good immunogenicity. A multicenter, nonrandomized phase II clinical trial of the vaccine showed that the progression-free survival (PFS) is significantly better, and another randomized phase II clinical study is underway135,136. In addition, when combined with CpG-7909, the specific peptides LY6K-177 and TTK-567, derived from squamous cell carcinoma, successfully triggered antigen-specific CD8+ T cell responses in patients with advanced ESCC, enhanced innate immunity, increased interferon-α and related chemokines, and activated natural killer cells137.

After subcutaneously transplanting EC9706 cells into humanized mice, administration of human umbilical vein endothelial cell vaccine for five consecutive weeks suppressed tumor growth by inhibiting angiogenesis, reducing angiogenesis-related antigen expression, and increasing angiogenesis-related antibody levels138. Dendritic cells, as the main antigen-presenting cells, can present heat-shock proteins (HSPs) to improve antigen loading efficiency and activate cytotoxic lymphocyte reaction. Dendritic cell vaccination can induce specific immune responses and Th1 cytokine secretion. The survival period of patients with EC who were treated with a combination of HSP-loaded dendritic cell vaccine and radiotherapy was better than that of patients who received radiotherapy alone139. Thus, treatment with dendritic cell-based vaccine is an effective method. For example, a vaccine loaded with chimeric epitopes of highly immunogenic antigen can induce cytotoxicity and may be a potential therapeutic option for patients with ESCC140. Cholesterol amylopectin (CHP) is a new type of antigen delivery system for vaccines. New York esophageal squamous cell carcinoma 1 (NY-ESO-1) antigen is specifically expressed in tumor tissue and is a promising molecular target for cancer treatment. A clinical trial has confirmed the safety and immunogenicity of the CHP-NY-ESO-1 vaccine, which induces an effective immune response at a dose of 200 μg141.

Patients with ESCC usually experience local recurrence following chemotherapy and radiotherapy. In a study where a peptide vaccine composed of five peptides was used for immunotherapy, all patients showed at least one peptide-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocyte reaction during the vaccination process. After the eighth vaccination, six patients exhibited a complete response, and four of them continued to receive the vaccine, experiencing 2.0, 2.9, 4.5, and 4.6 years of long-term sustained complete response142. Cancer peptide vaccines (CPVs) can enhance the immune response of the host to tumor-specific antigens. In addition, the impact of CPVs on the tumor microenvironment has been the focus of cancer research in recent years. For example, administration of CPV S-588410 (comprising five human leukocyte antigens overexpressed in EC) induced tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and PD-L1 expression in the tumor microenvironment. S-588410 may also stimulate cytotoxic T cell responses against tumor cells expressing the corresponding antigen143.

4.3. Other immunotherapy strategies

A multicenter, phase II, proof-of-concept study was conducted to evaluate the efficacy and safety of atezolizumab in patients with locally advanced ESCC after receiving chemotherapy. The combination of atezolizumab and chemotherapy synergistically increased the complete response rate144. After chemotherapy, the expression level of PD-L1 was significantly induced in ESCC cell lines, along with simultaneous activation of EGFR and ERK. After treatment, EGFR inhibitor (erlotinib) and MAPK/MEK inhibitor (AZD6244) were used to prevent chemotherapy-induced upregulation of PD-L1. Therefore, the combination of chemotherapy and anti-PD-L1 immunotherapy may be a promising strategy for ESCC treatment. However, other studies reported that patients with advanced ESCC who received anti-PD-1 antibody (camrelizumab) treatment followed by irinotecan-based chemotherapy, had a median PFS of 3.18 months and a median overall survival of only 6.23 months. These results indicated that there is no significant difference in response between patients treated with the combination therapy and those not treated with antibodies145.

In recent years, cell-based adoptive immunotherapy has attracted widespread attention, especially chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy. For example, a second-generation EphA2.CAR was constructed and transduced into T cells to produce EphA2.CAR-T cells, which exhibited a dose-dependent cytotoxicity superior to that of normal T cells. In addition, compared with normal T cells, the expression levels of tumor necrosis factor-α and interferon-γ in EphA2.CAR-T cells were significantly increased146. NY-ESO-1, an immunogenic cancer-testis antigen, induces a strong immune response in patients with cancer and can be used as a target for immunotherapy147. Overall, these findings demonstrate that immunotherapy is an effective and encouraging treatment strategy for patients with EC.

5. Conclusions and future perspectives

EC is a highly heterogeneous tumor; its origin, molecular characteristics, and unique tumor microenvironment affect clinical treatment results. At present, chemotherapy is the standard treatment for advanced and metastatic EC, but adverse reactions and drug resistance often occur. Therefore, there is an urgent need to further optimize the treatment regimen.

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) play an important role in tumorigenesis, drug resistance, recurrence, and metastasis, and are considered to be a challenge for effective treatment. Therefore, CSC-targeted therapy may be a promising strategy to improve clinical outcomes. Moreover, the combination of CSC-targeted therapy and immunotherapy to treat patients with EC is expected to show major advantages. Among molecular targeted therapies, use of antibodies against EGFR or VEGF ligands and oral TKIs have generated encouraging results; however, only HER2-and VEGFR-targeted therapies are currently approved for the treatment of metastatic EC. The latest advances in next-generation sequencing technology provide a comprehensive prediction of genetic changes in EC, which may lead to therapeutic breakthroughs. In addition, further research should focus on evaluating the combinations of multi-target drugs and new cytotoxic agents for better therapeutic effects.

Although ICIs show potential in the treatment of different types of cancer, individual patient responses greatly vary. Even among patients who meet the treatment criteria, only a small percentage of cases benefit from PD-1/PD-L1-based therapy. Therefore, the discovery of more precise biomarkers to select patients who may benefit from a long-lasting response to immunotherapy is crucial. However, biomarkers used for targeted therapy and prognostic evaluation of EC are limited. Future research should also focus on optimizing diagnostic analysis techniques and identifying predictive biomarkers to ensure that patients with EC benefit from immunotherapy. The continued development of miRNAs as biomarkers or therapeutic targets represents a new field of EC therapy. Analyzing the expression profile of miRNAs involved in EC development helps us better understand the disease pathogenesis. PD-L1 and PD-L2 participate in PD-1 receptor-mediated processes and induce PD-1-related signal transduction and T-cell failure. As PD-L2 exhibits a higher affinity than PD-L1, the development of PD-L2-based ICIs has become increasingly important.

According to the immune landscape in the tumor microenvironment, peptide vaccines, adoptive T cell therapy and ICIs can be used for EC treatment. Combining different ICIs or immunotherapy drugs with certain conventional treatment methods may maximize the therapeutic benefits. Notably, radiotherapy and chemotherapy may accelerate DNA mutation and the formation of new antigen molecules. Therefore, when combining immunotherapy with these conventional treatments, it is necessary to further determine the dose/intensity and duration of chemotherapy or radiation therapy.

Moreover, health promotion strategies (such as nutrition awareness and early medical counselling) also need to be considered to improve the treatment outcome of EC patients. Considering the continuous innovation of biomedical materials and treatment technologies, more effective drugs for the treatment of EC may soon be available to improve therapeutic outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No.2016YFA0201504), the Drug Innovation Major Project (No. 2018ZX09711001-009-003, China) and CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (No. 2016-I2M-3-013, China).

Author contributions

Conceptualization, Xiujun Liu, Jian Xu and Yongsu Zhen; supervision, Yongsu Zhen, Xiujun Liu and Jian Xu; writing and revising, Shiming He and Jian Xu. All authors have agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Pharmaceutical Association and Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

Contributor Information

Jian Xu, Email: pine20120929@gmail.com.

Xiujun Liu, Email: Liuxiujun2000@imb.pumc.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Pennathur A., Gibson M.K., Jobe B.A., Luketich J.D. Oesophageal carcinoma. Lancet. 2013;381:400–412. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60643-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fatehi Hassanabad A., Chehade R., Breadner D., Raphael J. Esophageal carcinoma: towards targeted therapies. Cell Oncol (Dordr) 2020;43:195–209. doi: 10.1007/s13402-019-00488-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang L., Zhou Y., Cheng C., Cui H., Cheng L., Kong P., et al. Genomic analyses reveal mutational signatures and frequently altered genes in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Am J Hum Genet. 2015;96 doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.02.017. 597-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rustgi A.K., Ingelfinger J.R., El-Serag H.B. Esophageal carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2499–2509. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1314530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thrift A.P. Esophageal adenocarcinoma: the influence of medications used to treat comorbidities on cancer prognosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:2225–2232. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fujihara S., Morishita A., Ogawa K., Tadokoro T., Masaki T. The angiotensin II type 1 receptor antagonist telmisartan inhibits cell proliferation and tumor growth of esophageal adenocarcinoma via the AMPKα/mTOR pathway in vitro and in vivo. Oncotarget. 2016;8:8536–8549. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pohl H., Wrobel K., Bojarski C., Voderholzer W., Sonnenberg A., Rosch T., et al. Risk factors in the development of esophageal adenocarcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:200–207. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quante M., Graham T.A., Jansen M. Insights into the pathophysiology of esophageal adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:406–420. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu K., Zhao T., Wang J., Chen Y., Zhang R., Lan X., et al. Etiology, cancer stem cells and potential diagnostic biomarkers for esophageal cancer. Cancer Lett. 2019;458:21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2019.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen P., Li M., Hao Q., Zhao X., Hu T. Targeting the overexpressed CREB inhibits esophageal squamous cell carcinoma cell growth. Oncol Rep. 2018;39:1369–1377. doi: 10.3892/or.2017.6167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hong D., Liu T., Huang W., Liao Y., Wang L., Zhang Z., et al. Gremlin1 delivered by mesenchymal stromal cells promoted epithelial–mesenchymal transition in human esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2018;47:1785–1799. doi: 10.1159/000491060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cai R., Wang P., Zhao X., Lu X., Deng R., Wang X., et al. LTBP1 promotes esophageal squamous cell carcinoma progression through epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cancer-associated fibroblasts transformation. J Transl Med. 2020;18:139. doi: 10.1186/s12967-020-02310-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li Q.H., Yang L., Han K., Zhu L.Q., Zhang Y.T., Ma S.S., et al. Ets2 knockdown inhibits tumorigenesis in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in vivo and in vitro. Oncotarget. 2016;7:61458–61468. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang J.Y., Li S., Shang Z.Y., Lin S., Gao P., Zhang Y., et al. Targeting the overexpressed ROC1 induces G2 cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in esophageal cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2017;8:29125–29137. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhu H., Zhang H., Jin F., Fang M., Huang M., Yang C.S., et al. Elevated Orai1 expression mediates tumor-promoting intracellular Ca2+ oscillations in human esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2014;5:3455–3471. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cui C., Chang Y., Zhang X., Choi S., Tran H., Penmetsa K.V., et al. Targeting Orai1-mediated store-operated calcium entry by RP4010 for anti-tumor activity in esophagus squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2018;432:169–179. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2018.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cao Y.Y., Yu J., Liu T.T., Yang K.X., Yang L.Y., Chen Q., et al. Plumbagin inhibits the proliferation and survival of esophageal cancer cells by blocking STAT3-PLK1-AKT signaling. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:17. doi: 10.1038/s41419-017-0068-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang X., Zhu Y., Zhu L., Chen X., Xu Y., Zhao Y., et al. Eupatilin inhibits the proliferation of human esophageal cancer TE1 cells by targeting the AktGSK3beta and MAPK/ERK signaling cascades. Oncol Rep. 2018;39:2942–2950. doi: 10.3892/or.2018.6390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen P., Zhang J.Y., Sha B.B., Ma Y.E., Hu T., Ma Y.C., et al. Luteolin inhibits cell proliferation and induces cell apoptosis via down-regulation of mitochondrial membrane potential in esophageal carcinoma cells EC1 and KYSE450. Oncotarget. 2017;8:27471–27480. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou S., Liu S., Lin C., Li Y., Ye L., Wu X., et al. TRIB3 confers radiotherapy resistance in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma by stabilizing TAZ. Oncogene. 2020;39:3710–3725. doi: 10.1038/s41388-020-1245-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vrana D., Hlavac V., Brynychova V., Vaclavikova R., Neoral C., Vrba J., et al. ABC transporters and their role in the neoadjuvant treatment of esophageal cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:868. doi: 10.3390/ijms19030868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hemmatzadeh M., Mohammadi H., Karimi M., Musavishenas M.H., Baradaran B. Differential role of microRNAs in the pathogenesis and treatment of esophageal cancer. Biomed Pharmacother. 2016;82:509–519. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2016.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang C., Zheng X., Ye K., Sun Y., Lu Y., Fan Q., et al. miR-135a inhibits the invasion and migration of esophageal cancer stem cells through the hedgehog signaling pathway by targeting SMO. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2020;19:841–852. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2019.10.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 24.Liu J.Q., Deng M., Xue N.N., Li T.X., Guo Y.X., Gao L., et al. lncRNA KLF3-AS1 suppresses cell migration and invasion in ESCC by impairing miR-185-5p-targeted KLF3 inhibition. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2020;20:231–241. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2020.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ohashi S., Kikuchi O., Nakai Y., Ida T., Saito T., Kondo Y., et al. Synthetic lethality with trifluridine/tipiracil and checkpoint kinase 1 inhibitor for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Mol Cancer Ther. 2020;19:1363–1372. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-19-0918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xie X., Zu X., Liu F., Wang T., Wang X., Chen H., et al. Purpurogallin is a novel mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1/2 inhibitor that suppresses esophageal squamous cell carcinoma growth in vitro and in vivo. Mol Carcinog. 2019;58:1248–1259. doi: 10.1002/mc.23007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu H., Zhao J., Fu R., Zhu C., Fan D. The ginsenoside Rk3 exerts anti-esophageal cancer activity in vitro and in vivo by mediating apoptosis and autophagy through regulation of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. PLoS One. 2019;14 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0216759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Samson P., Lockhart A.C. Biologic therapy in esophageal and gastric malignancies: current therapies and future directions. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2017;8:418–429. doi: 10.21037/jgo.2016.11.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tanaka T., Nakamura J., Noshiro H. Promising immunotherapies for esophageal cancer. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2017;17:723–733. doi: 10.1080/14712598.2017.1315404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang Y., Zhang Y., Zhang L. Expression of cancer-testis antigens in esophageal cancer and their progress in immunotherapy. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2019;145:281–291. doi: 10.1007/s00432-019-02840-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kojima T., Doi T. Immunotherapy for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Curr Oncol Rep. 2017;19:33. doi: 10.1007/s11912-017-0590-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang J.N., Che Y., Yuan Z.Y., Lu Z.L., Li Y., Zhang Z.R., et al. Acetyl-macrocalin B suppresses tumor growth in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and exhibits synergistic anti-cancer effects with the Chk1/2 inhibitor AZD7762. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2019;365:71–83. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2019.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang C., Ma Q., Shi Y., Li X., Wang M., Wang J., et al. A novel 5-fluorouracil-resistant human esophageal squamous cell carcinoma cell line Eca-109/5-FU with significant drug resistance-related characteristics. Oncol Rep. 2017;37:2942–2954. doi: 10.3892/or.2017.5539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li L., Yue G.G.L., Lee J.K.M., Wong E.C.W., Fung K.P., Yu J., et al. The adjuvant value of Andrographis paniculata in metastatic esophageal cancer treatment—from preclinical perspectives. Sci Rep. 2017;7:854. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-00934-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang J., Jiang D., Li X., Lv J., Xie L., Zheng L., et al. Establishment and characterization of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma patient-derived xenograft mouse models for preclinical drug discovery. Lab Invest. 2014;94:917–926. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2014.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shi Q., Shen L.Y., Dong B., Fu H., Kang X.Z., Yang Y.B., et al. The identification of the ATR inhibitor VE-822 as a therapeutic strategy for enhancing cisplatin chemosensitivity in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2018;432:56–68. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2018.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Che Y., Wang J., Li Y., Lu Z., Huang J., Sun S., et al. Cisplatin-activated PAI-1 secretion in the cancer-associated fibroblasts with paracrine effects promoting esophageal squamous cell carcinoma progression and causing chemoresistance. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:759. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-0808-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang Y., Zhu X., Huang T., Chen L., Liu Y., Li Q., et al. beta-Carotene synergistically enhances the anti-tumor effect of 5-fluorouracil on esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in vivo and in vitro. Toxicol Lett. 2016;261:49–58. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2016.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Song S., Xie M., Scott A.W., Jin J., Ma L., Dong X., et al. A novel YAP1 inhibitor targets CSC-enriched radiation-resistant cells and exerts strong antitumor activity in esophageal adenocarcinoma. Mol Cancer Ther. 2018;17:443–454. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-17-0560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tong Z., Mejia A., Veeranki O., Verma A., Correa A.M., Dokey R., et al. Targeting CDK9 and MCL-1 by a new CDK9/p-TEFb inhibitor with and without 5-fluorouracil in esophageal adenocarcinoma. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2019;11 doi: 10.1177/1758835919864850. 1758835919864850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dong W. Hesperetin inhibits Eca-109 cell proliferation and invasion by suppressing the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway and synergistically enhances the anti-tumor effect of 5-fluorouracil on esophageal cancer in vitro and in vivo. RSC Adv. 2018;8:24434–24443. doi: 10.1039/c8ra00956b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang J.U.N., Yang Z.R., Guo X.F., Song J.I.A., Zhang J.X., Wang J., et al. Synergistic effects of puerarin combined with 5-fluorouracil on esophageal cancer. Mol Med Rep. 2014;10:2535–2541. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2014.2539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen Q.R., Song S.M., Wei S.Z., Liu B., Honjo S., Scott A., et al. ABT-263 induces apoptosis and synergizes with chemotherapy by targeting stemness pathways in esophageal cancer. Oncotarget. 2015;6:25883–25896. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang K., Zhang B., Bai Y., Dai L. E2F1 promotes cancer cell sensitivity to cisplatin by regulating the cellular DNA damage response through miR-26b in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J Cancer. 2020;11:301–310. doi: 10.7150/jca.33983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li Y., Zhu C.L., Nie C.J., Li J.C., Zeng T.T., Zhou J., et al. Investigation of tumor suppressing function of CACNA2D3 in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nie C., Qin X., Li X., Tian B., Zhao Y., Jin Y., et al. CACNA2D3 enhances the chemosensitivity of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma to cisplatin via inducing Ca2+-mediated apoptosis and suppressing PI3K/Akt pathways. Front Oncol. 2019;9:185. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.00185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang J., Ji H., Zhu Q., Yu X., Du J., Jiang Z. Co-inhibition of BMI1 and Mel18 enhances chemosensitivity of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in vitro and in vivo. Oncol Lett. 2019;17:5012–5022. doi: 10.3892/ol.2019.10160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huang X.P., Li X., Situ M.Y., Huang L.Y., Wang J.Y., He T.C., et al. Entinostat reverses cisplatin resistance in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma via down-regulation of multidrug resistance gene 1. Cancer Lett. 2018;414:294–300. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2017.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li B., Hong P., Zheng C.C., Dai W., Chen W.Y., Yang Q.S., et al. Identification of miR-29c and its target FBXO31 as a key regulatory mechanism in esophageal cancer chemoresistance: functional validation and clinical significance. Theranostics. 2019;9:1599–1613. doi: 10.7150/thno.30372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang Y., Zhao Y., Herbst A., Kalinski T., Qin J., Wang X., et al. miR-221 mediates chemoresistance of esophageal adenocarcinoma by direct targeting of DKK2 expression. Ann Surg. 2016;264:804–814. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zang W.Q., Wang T., Wang Y.Y., Chen X.N., Du Y.W., Sun Q.Q., et al. Knockdown of long non-coding RNA TP73-AS1 inhibits cell proliferation and induces apoptosis in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2016;7:19960–19974. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lin K., Jiang H., Zhuang S.S., Qin Y.S., Qiu G.D., She Y.Q., et al. Long noncoding RNA LINC00261 induces chemosensitization to 5-fluorouracil by mediating methylation-dependent repression of DPYD in human esophageal cancer. FASEB J. 2019;33:1972–1988. doi: 10.1096/fj.201800759R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kai J., Wang Y., Xiong F., Wang S. Genetic and pharmacological inhibition of eIF4E effectively targets esophageal cancer cells and augments 5-FU’s efficacy. J Thorac Dis. 2018;10:3983–3991. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2018.06.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tajaldini M., Samadi F., Khosravi A., Ghasemnejad A., Asadi J. Protective and anticancer effects of orange peel extract and naringin in doxorubicin treated esophageal cancer stem cell xenograft tumor mouse model. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;121:109594. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.109594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jin Y., Ma X., Zhang S., Meng H., Xu M., Yang X., et al. A tantalum oxide-based core/shell nanoparticle for triple-modality image-guided chemo-thermal synergetic therapy of esophageal carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2017;397:61–71. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2017.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang L., Yao M., Yan W., Liu X., Jiang B., Qian Z., et al. Delivery of a chemotherapeutic drug using novel hollow carbon spheres for esophageal cancer treatment. Int J Nanomed. 2017;12:6759–6769. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S142916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dai S., Ye Z., Wang F., Yan F., Wang L., Fang J., et al. Doxorubicin-loaded poly(ε-caprolactone)-pluronic micelle for targeted therapy of esophageal cancer. J Cell Biochem. 2018;119:9017–9027. doi: 10.1002/jcb.27159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kitabayashi H., Shimada H., Yamada S., Yasuda S., Kamata T., Ando K., et al. Synergistic growth suppression induced in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma cells by combined treatment with docetaxel and heavy carbon-ion beam irradiation. Oncol Rep. 2006;15:913–918. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang C., Guo L., Wang S., Wang J., Li Y., Dou Y., et al. Anti-proliferative effect of Jesridonin on paclitaxel-resistant EC109 human esophageal carcinoma cells. Int J Mol Med. 2017;39:645–653. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2017.2867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Guo X.F., Li S.S., Zhu X.F., Dou Q.H., Liu D. Lapatinib in combination with paclitaxel plays synergistic antitumor effects on esophageal squamous cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2018;82:383–394. doi: 10.1007/s00280-018-3627-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hassan M.S., Awasthi N., Li J., Williams F., Schwarz M.A., Schwarz R.E., et al. Superior therapeutic efficacy of nanoparticle albumin bound paclitaxel over cremophor-bound paclitaxel in experimental esophageal adenocarcinoma. Transl Oncol. 2018;11:426–435. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2018.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zou J., Li S., Chen Z., Lu Z., Gao J., Zou J., et al. A novel oral camptothecin analog, gimatecan, exhibits superior antitumor efficacy than irinotecan toward esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in vitro and in vivo. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:661. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-0700-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ciardiello F., Tortora G. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) as a target in cancer therapy: understanding the role of receptor expression and other molecular determinants that could influence the response to anti-EGFR drugs. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39:1348–1354. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(03)00235-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hanawa M., Suzuki S., Dobashi Y., Yamane T., Kono K., Enomoto N., et al. EGFR protein overexpression and gene amplification in squamous cell carcinomas of the esophagus. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:1173–1180. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kawaguchi Y., Kono K., Mimura K., Sugai H., Akaike H., Fujii H. Cetuximab induce antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity against EGFR-expressing esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2007;120:781–787. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vincenzi B., Schiavon G., Silletta M., Santini D., Tonini G. The biological properties of cetuximab. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;68:93–106. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Morelli M.P., Cascone T., Troiani T., Tuccillo C., Bianco R., Normanno N., et al. Anti-tumor activity of the combination of cetuximab, an anti-EGFR blocking monoclonal antibody and ZD6474, an inhibitor of VEGFR and EGFR tyrosine kinases. J Cell Physiol. 2006;208:344–353. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhu H., Wang C., Wang J., Chen D., Deng J., Deng J., et al. A subset of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma patient-derived xenografts respond to cetuximab, which is predicted by high EGFR expression and amplification. J Thorac Dis. 2018;10:5328–5338. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2018.09.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gong J.H., Liu X.J., Li Y., Zhen Y.S. Pingyangmycin downregulates the expression of EGFR and enhances the effects of cetuximab on esophageal cancer cells and the xenograft in athymic mice. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2012;69:1323–1332. doi: 10.1007/s00280-012-1827-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kwon J., Yoon H.J., Kim J.H., Lee T.S., Song I.H., Lee H.W., et al. Cetuximab inhibits cisplatin-induced activation of EGFR signaling in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2014;32:1188–1192. doi: 10.3892/or.2014.3302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hartmans E., Linssen M.D., Sikkens C., Levens A., Witjes M.J.H., van Dam G.M., et al. Tyrosine kinase inhibitor induced growth factor receptor upregulation enhances the efficacy of near-infrared targeted photodynamic therapy in esophageal adenocarcinoma cell lines. Oncotarget. 2017;8:29846–29856. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kubo N. Concurrent biological targeting therapy of squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus with cetuximab and trastuzumab. Oncol Rep. 2012;28:49–54. doi: 10.3892/or.2012.1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhang Y., Pan T.C., Zhong X.X., Cheng C. Resistance to cetuximab in EGFR-overexpressing esophageal squamous cell carcinoma xenografts due to FGFR2 amplification and overexpression. J Pharmacol Sci. 2014;126:77–83. doi: 10.1254/jphs.14150fp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yoshioka M., Ohashi S., Ida T., Nakai Y., Kikuchi O., Amanuma Y., et al. Distinct effects of EGFR inhibitors on epithelial- and mesenchymal-like esophageal squamous cell carcinoma cells. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2017;36:101. doi: 10.1186/s13046-017-0572-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Talavera A., Friemann R., Gómezpuerta S., Martinezfleites C., Garrido G., Rabasa A., et al. Nimotuzumab, an antitumor antibody that targets the epidermal growth factor receptor, blocks ligand binding while permitting the active receptor conformation. Cancer Res. 2009;69:5851–5859. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhao L., He L.R., Xi M.A., Cai M.Y., Shen J.X., Li Q.Q., et al. Nimotuzumab promotes radiosensitivity of EGFR-overexpression esophageal squamous cell carcinoma cells by upregulating IGFBP-3. J Transl Med. 2012;10:249. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-10-249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pedersen M.W., Jacobsen H.J., Koefoed K., Hey A., Pyke C., Haurum J.S., et al. Sym004: a novel synergistic anti-epidermal growth factor receptor antibody mixture with superior anticancer efficacy. Cancer Res. 2010;70:588–597. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fukuoka S., Kojima T., Koga Y., Yamauchi M., Komatsu M., Komatsuzaki R., et al. Preclinical efficacy of Sym004, novel anti-EGFR antibody mixture, in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma cell lines. Oncotarget. 2017;8:11020–11029. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yang Y., Tian Z., Ding Y., Li X., Zhang Z., Yang L., et al. EGFR-targeted immunotoxin exerts antitumor effects on esophageal cancers by increasing ROS accumulation and inducing apoptosis via inhibition of the Nrf2–Keap1 pathway. J Immunol Res. 2018;2018:1090287. doi: 10.1155/2018/1090287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hu X.Y., Wang R., Jin J., Liu X.J., Cui Al, Sun L.Q., et al. An EGFR-targeting antibody–drug conjugate LR004-VC-MMAE: potential in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and other malignancies. Mol Oncol. 2019;13:246–263. doi: 10.1002/1878-0261.12400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kang M., Ren M., Li Y., Fu Y., Deng M., Li C. Exosome-mediated transfer of lncRNA PART1 induces gefitinib resistance in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma via functioning as a competing endogenous RNA. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2018;37:171. doi: 10.1186/s13046-018-0845-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 82.Cui G., Cui M., Li Y., Liang Y., Li W., Guo H., et al. Galectin-3 knockdown increases gefitinib sensitivity to the inhibition of EGFR endocytosis in gefitinib-insensitive esophageal squamous cancer cells. Med Oncol. 2015;32:124. doi: 10.1007/s12032-015-0570-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Xu Y., Xie Z., Shi Y., Zhang M., Lu H. Gefitinib single drug in treatment of advanced esophageal cancer. J Cancer Res Ther. 2016;12 Suppl:C295–C297. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.200760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chi H.W., Ma B.B.Y., Hui C.W.C., Qian T., Chan A.T.C. Preclinical evaluation of afatinib (BIBW2992) in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) Am J Cancer Res. 2016;5:3588–3599. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Liu Z., Chen Z., Wang J., Zhang M., Li Z., Wang S., et al. Mouse avatar models of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma proved the potential for EGFR-TKI afatinib and uncovered Src family kinases involved in acquired resistance. J Hematol Oncol. 2018;11:109. doi: 10.1186/s13045-018-0651-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Nakamura Y., Togashi Y., Nakahara H., Tomida S., Banno E., Terashima M., et al. Afatinib against esophageal or head-and-neck squamous cell carcinoma: significance of activating oncogenic HER4 mutations in HNSCC. Mol Cancer Ther. 2016;15:1988–1997. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-15-0737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wu J., Chen K., Zhang F., Jin J., Zhang N., Li D., et al. Overcoming linsitinib intrinsic resistance through inhibition of nuclear factor-κB signaling in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Med. 2017;6:1353–1361. doi: 10.1002/cam4.1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Slichenmyer W.J., Elliott W.L., Fry D.W. CI-1033, a pan-erbB tyrosine kinase inhibitor. Semin Oncol. 2001;28:80–85. doi: 10.1016/s0093-7754(01)90285-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ako E., Yamashita Y., Ohira M., Yamazaki M., Hori T., Kubo N., et al. The pan-ErbB tyrosine kinase inhibitor CI-1033 inhibits human esophageal cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. Oncol Rep. 2007;17:887–893. doi: 10.3892/or.17.4.887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mimura K., Kono K., Maruyama T., Watanabe M., Izawa S., Shiba S., et al. Lapatinib inhibits receptor phosphorylation and cell growth and enhances antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity of EGFR- and HER2-overexpressing esophageal cancer cell lines. Int J Cancer. 2011;129:2408–2416. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hou W., Qin X., Zhu X., Fei M., Liu P., Liu L., et al. Lapatinib inhibits the growth of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and synergistically interacts with 5-fluorouracil in patient-derived xenograft models. Oncol Rep. 2013;30:707–714. doi: 10.3892/or.2013.2500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hassan M.S., Williams F., Awasthi N., Schwarz M.A., Schwarz R.E., Li J., et al. Combination effect of lapatinib with foretinib in HER2 and MET co-activated experimental esophageal adenocarcinoma. Sci Rep. 2019;9:17608. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-54129-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Reichelt U., Duesedau P., Tsourlakis M.C., Quaas A., Link B.C., Schurr P.G., et al. Frequent homogeneous HER-2 amplification in primary and metastatic adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. Mod Pathol. 2007;20:120–129. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sanchez-Vega F., Hechtman J.F., Castel P., Ku G.Y., Tuvy Y., Won H., et al. EGFR and MET amplifications determine response to HER2 inhibition in ERBB2-amplified esophagogastric cancer. Cancer Discov. 2019;9:199–209. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-18-0598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Chen H., Ye Q.Q., Lv J., Ye P., Sun Y., Fan S.Q., et al. Evaluation of trastuzumab anti-tumor efficacy and its correlation with HER-2 status in patient-derived gastric adenocarcinoma xenograft models. Pathol Oncol Res. 2015;21:947–955. doi: 10.1007/s12253-015-9909-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lange T., Nentwich M.F., Lüth M., Yekebas E., Schumacher U. Trastuzumab has anti-metastatic and anti-angiogenic activity in a spontaneous metastasis xenograft model of esophageal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2011;308:54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Gros S.J., Kurschat N., Dohrmann T., Reichelt U., Dancau A.M., Peldschus K., et al. Effective therapeutic targeting of the overexpressed HER-2 receptor in a highly metastatic orthotopic model of esophageal carcinoma. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9:2037–2045. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wu X., Zhang J., Zhen R., Lv J., Zheng L., Su X., et al. Trastuzumab anti-tumor efficacy in patient-derived esophageal squamous cell carcinoma xenograft (PDECX) mouse models. J Transl Med. 2012;10:180. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-10-180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hong J., Katsha A., Lu P., Shyr Y., Belkhiri A., El-Rifai W. Regulation of ERBB2 receptor by t-DARPP mediates trastuzumab resistance in human esophageal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 2012;72:4504–4514. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ebbing E.A., Steins A., Fessler E., Stathi P., Lesterhuis W.J., Krishnadath K.K., et al. Esophageal adenocarcinoma cells and xenograft tumors exposed to Erb-b2 receptor tyrosine kinase 2 and 3 inhibitors activate transforming growth factor beta signaling, which induces epithelial to mesenchymal transition. Gastroenterology. 2017;153:63–76 e14. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Chen Y., Wang D., Peng H., Chen X., Han X., Yu J., et al. Epigenetically upregulated oncoprotein PLCE1 drives esophageal carcinoma angiogenesis and proliferation via activating the PI-PLCε-NF-κB signaling pathway and VEGF-C/Bcl-2 expression. Mol Cancer. 2019;18:1. doi: 10.1186/s12943-018-0930-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Liu P., Zhou J., Zhu H., Xie L., Wang F., Liu B., et al. VEGF-C promotes the development of esophageal cancer via regulating CNTN-1 expression. Cytokine. 2011;55:8–17. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kitadai Y., Amioka T., Haruma K., Tanaka S., Yoshihara M., Sumii K., et al. Clinicopathological significance of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-C in human esophageal squamous cell carcinomas. Int J Cancer. 2001;93:662–666. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]