Abstract

Aspergillus species are the most frequent cause of invasive mold infections in immunocompromised patients. Although over 180 species are found within the genus, 3 species, Aspergillus flavus, A. fumigatus, and A. terreus, account for most cases of invasive aspergillosis (IA), with A. nidulans, A. niger, and A. ustus being rare causes of IA. The ability to distinguish between the various clinically relevant Aspergillus species may have diagnostic value, as certain species are associated with higher mortality and increased virulence and vary in their resistance to antifungal therapy. A method to identify Aspergillus at the species level and differentiate it from other true pathogenic and opportunistic molds was developed using the 18S and 28S rRNA genes for primer binding sites. The contiguous internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region, ITS 1–5.8S–ITS 2, from referenced strains and clinical isolates of aspergilli and other fungi were amplified, sequenced, and compared with non-reference strain sequences in GenBank. ITS amplicons from Aspergillus species ranged in size from 565 to 613 bp. Comparison of reference strains and GenBank sequences demonstrated that both ITS 1 and ITS 2 regions were needed for accurate identification of Aspergillus at the species level. Intraspecies variation among clinical isolates and reference strains was minimal. Sixteen other pathogenic molds demonstrated less than 89% similarity with Aspergillus ITS 1 and 2 sequences. A blind study of 11 clinical isolates was performed, and each was correctly identified. Clinical application of this approach may allow for earlier diagnosis and selection of effective antifungal agents for patients with IA.

Aspergillus species are associated with allergic bronchopulmonary disease, mycotic keratitis, otomycosis, nasal sinusitis, and invasive infection. The most severe disease caused by aspergilli occurs in immunocompromised patients, with invasive pulmonary infection followed by rapid dissemination. The frequency of invasive mold infections has increased in recent years due to the increasing number of patients receiving aggressive chemotherapy regimens and immunosuppressive agents (2). The nonspecific symptoms and the lack of rapid diagnostic assays to detect these infections have been major problems in treating patients with invasive disease, particularly those with invasive aspergillosis (IA). Early recognition of invasive fungal infection and treatment with appropriate antifungal therapy are key to reducing the mortality associated with disseminated disease (25). The mortality rate for bone marrow transplant patients with pulmonary IA is greater than 70% (5, 15). Due to the typically long time required for identification of a mold using standard culture procedures, most patients with suspected disease are treated empirically with amphotericin B (AmB). Resistance to AmB as well as itraconazole has been reported for some Aspergillus species although the number of isolates studied in each case was limited (14, 16).

Unfortunately, the identification of aspergilli based on morphological methods requires adequate growth for evaluation of colony characteristics and microscopic features. A culture time of 5 days or more is generally required for identification of anamorphic forms of Aspergillus. There are more than 180 species in the Aspergillus genus, although 3, Aspergillus flavus, A. fumigatus, and A. terreus account for the vast majority of IA infections. A. nidulans, A. niger, and A. ustus are rarely encountered as causes of invasive disease (18).

Various molecular approaches have been used for the detection of Aspergillus from environmental and clinical samples (3, 6, 27). Targets for the genus level detection of Aspergillus have included the 18S rRNA gene, mitochondrial DNA, the intergenic spacer region, and the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) regions. The ITS regions are located between the 18S and 28S rRNA genes and offer distinct advantages over other molecular targets including increased sensitivity due to the existence of approximately 100 copies per genome. The rRNA gene for 5.8S RNA separates the two ITS regions. The sequence variation of ITS regions has led to their use in phylogenetic studies of many different organisms (9, 26). Most recently, Turenne et al. have proposed the use of ITS amplicons of different lengths for identification of Aspergillus species by capillary electrophoresis (CE) (23).

The goal of this study was to compare the ITS 1 and 2 nucleotide sequences of clinically important Aspergillus species and determine whether sufficient variability existed for identification to the species level. The majority of GenBank ITS sequences available prior to this study were either incomplete or were generated from nonreferenced isolates. Therefore, the ITS sequences of referenced pathogenic Aspergillus species and other opportunistic fungi were determined. A standardized method was developed for identification, and the ability of this approach to identify pathogenic Aspergillus strains was evaluated in a blind clinical study.

(This work was presented at the 99th General Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology, Chicago, Ill., May 1999.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cultures for analysis.

Referenced cultures of Aspergillus species obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) included A. flavus ATCC 16883, A. fumigatus ATCC 36607, A. nidulans ATCC 10074, A. niger ATCC 16888, and A. terreus ATCC 16792. A. ustus UAMH 9479 was obtained from the University of Alberta Microfungus Collection and Herbarium. Isolates of Aspergillus species from cases of IA were obtained from patient samples catalogued at the University of Nebraska Medical Center (UNMC) and inventoried in the Invasive Molds Infection (IMI) database. Morphological identification of clinical isolates to the species level was accomplished using established procedures including microscopic and macroscopic characteristics. Additional fungal species selected for sequence comparison with Aspergillus reference strains are listed in Table 4.

TABLE 4.

Nucleotide base differences in ITS 1–5.8S–ITS 2 between A. fumigatus and other medically important fungal genera

| Species and accession no. | No. of nucleotide base differences in:

|

% Similaritya | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITS 1 | ITS 2 | ITS 1–5.8S–ITS 2 | ||

| Ajellomyces capsulatus | ||||

| AF038353 | 93 | 45 | 143 | 76.6 |

| AF156892b | 86 | 59 | 150 | 76.7 |

| Ajellomyces dermatitidis | ||||

| AF038355 | 93 | 66 | 163 | 74.1 |

| Candida albicans | ||||

| AF217609b | 108 | 98 | 221 | 65.0 |

| L28817 | 97 | 98 | 211 | 64.8 |

| Cladophialophora bantiana | ||||

| AF131079b | 82 | 111 | 202 | 68.1 |

| Cryptococcus neoformans | ||||

| AF162916b | 99 | 123 | 237 | 59.1 |

| L14067 | 53 | 126 | 193 | 59.4 |

| Cylindrocarpon lichenicola | ||||

| AF133845b | 102 | 79 | 185 | 69.2 |

| Fusarium oxysporum | ||||

| AF132799 | 85 | 91 | 180 | 62.3 |

| Fusarium solanii | ||||

| U38558 | 100 | 92 | 202 | 66.7 |

| Fusarium spp. | ||||

| IMI 183 | 99 | 89 | 197 | 67.0 |

| Gymnascella hyalinospora | ||||

| AF129854b | 87 | 57 | 149 | 76.3 |

| Penicillium capsulatum | ||||

| AF033429 | 44 | 23 | 70 | 88.0 |

| Penicillium glabrum | ||||

| AF033407 | 39 | 22 | 62 | 89.6 |

| Penicillium marnefeii | ||||

| ATCC 18224c | 60 | 57 | 124 | 79.1 |

| L37406 | 57 | 54 | 116 | 79.5 |

| Phialophora verrucosa | ||||

| AF050281 | 78 | 104 | 196 | 67.5 |

| Pseudallescheria boydii | ||||

| AF022486 | 106 | 131 | 248 | 55.6 |

| AF181558b | 109 | 132 | 252 | 55.4 |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | ||||

| Z95929 | 144 | 146 | 302 | 50.2 |

Compared to A. fumigatus ATCC 36607.

Sequence deposited into GenBank as part of this study.

Reference strain sequenced but not deposited into GenBank.

Culture preparation and DNA extraction.

Extraction of DNA from fungi was performed following the needle inoculation of 50 ml of Sabouraud dextrose (SAB) broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) with conidia from a 7-day culture in SAB agar and incubation for 72 h at 30°C. The hyphae were recovered on a 0.45-μm-pore-size filter and washed with sterile saline. Aliquots of the fungal hyphae were stored frozen at −70°C until use. Prior to lysis, the hyphae were thawed and suspended in 400 μl of DNA extraction buffer (1 mM EDTA [pH 8.0], 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.6], 100 mM NaCl, 2% Triton X-100) as described by Van Burik et al. (24). Microcentrifuge tubes (1.5 ml) containing hyphae and buffer were sonicated in a water bath (Branson; model 2210) for 15 min, followed by heating at 100°C for 5 min. Following lysis, DNA was purified using the QIAmp blood kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, Calif.) and protocols for crude cell lysates supplied by the manufacturer. Following extraction, the purified DNA was stored at 4°C until tested.

Primers.

Two oligonucleotide fungal primers described by White et al. were used for amplification (26). The ITS region primers (ITS 1, 5′-TCC GTA GGT GAA CCT GCG G- 3′; ITS 4, 5′-TCC TCC GCT TAT TGA TAT G-3′) make use of conserved regions of the 18S (ITS 1) and the 28S (ITS 4) rRNA genes to amplify the intervening 5.8S gene and the ITS 1 and ITS 2 noncoding regions. Primers were synthesized by the UNMC, Eppley Molecular Biology Core Laboratory.

PCR amplification.

The PCR assay was performed with 5 μl of test sample in a total reaction volume of 50 μl consisting of PCR buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.4], 50 mM KCl; 0.1 mM (each) dATP, dGTP, dCTP, and dTTP; 1.5 mM MgCl2; 0.3 μM (each) primer; and 1.5 U of PlatinumTaq high-fidelity DNA polymerase (Gibco BRL, Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, Md.). Forty cycles of amplification were performed in a Stratagene Robocycler model 96 thermocycler after initial denaturation of DNA at 95°C for 4.5 min. Each cycle consisted of a denaturation step at 95°C for 30 s, an annealing step at 50°C for 30 s, and an extension step at 72°C for 1 min, with a final extension at 72°C for 3 min following the last cycle. After amplification, the products were stored at 4°C until used.

Cloning of PCR products.

Amplicons were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis, purified, and ligated into the pCR 2.1 plasmid vector using the Original TA cloning kit (Invitrogen, San Diego, Calif.). Competent INVαF′ One Shot cells were transformed using standard protocols. Colonies were isolated and purified with a Qiagen miniprep spin kit according to the manufacturer's protocols. An aliquot of purified plasmid was digested with EcoRI endonuclease (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.) and screened by agarose gel electrophoresis for a 300-bp doublet, indicating the presence of the EcoRI cleavage site GAATTC within the 5.8S sequence. Selected plasmids were submitted to the Eppley Molecular Biology Core Laboratory for automated dye termination sequencing.

DNA sequencing.

DNA sequencing was performed at the Eppley Molecular Biology Core Laboratory on a Perkin-Elmer/ABI model 373 DNA sequencer with protocols supplied by the manufacturer. For the sequencing of cloned fragments, both strands of the plasmid containing the fungal insert were sequenced with universal M13 forward and reverse sequencing primers. For direct sequencing of noncloned amplicons, PCR products were directly sequenced using the ITS 1 and ITS 4 PCR primers. The resultant nucleotide sequences were aligned with the MacVector sequence analysis software, version 6.5 (Oxford Molecular Group, Inc., Campbell, Calif.), alignment application.

Sequence analysis.

Sequence comparisons of referenced strains and clinical isolates listed in Fig. 1 and Table 3 were made using MacVector, version 6.5, software (Oxford Molecular Group, Inc.) and the Clustal W alignment algorithm. Intraspecies sequence similarity and variation for isolates listed in Table 2 were determined by the MacVector software and were visually confirmed using pairwise nucleotide alignments. Sequences from referenced isolates were aligned to complete or partial ITS sequences available in GenBank after submission of sequence data from this study. Comparison of sequences from referenced isolates, clinical isolates, and GenBank sequences was performed using a nongapped, advanced BLAST search (1). The similarities of the sequences were determined with the expectation frequency minimized to 0.0001. Sequences were not filtered for low complexity.

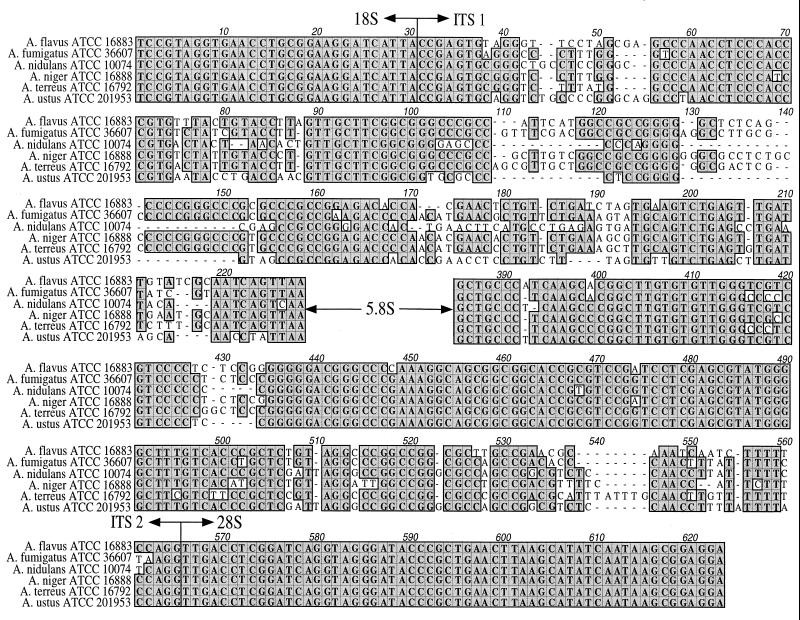

FIG. 1.

Nucleotide sequence alignment of A. flavus (ATCC 16883), A. fumigatus (ATCC 36607), A. nidulans (ATCC 10074), A. niger (ATCC 16888), A. terreus (ATCC 16792), and A. ustus (ATCC 201953). The alignment consists of the 3′ end of the 18S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) gene (which contains the ITS 1 primer site), the complete ITS 1 region, the complete ITS 2 region, and the 5′ end of the 28S rDNA gene (which contains the ITS 4 primer site). The highly conserved 5.8S rDNA gene sequence has been omitted.

TABLE 3.

Numbers of nucleotide differences in ITS 1–5.8S–ITS 2 within a single species

| Strain and accession no. | No. of nucleotide base differences in:

|

% Similarity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITS 1 | ITS 2 | ITS 1–5.8S–ITS 2 | ||

| A. flavus ATCC 16883 | ||||

| IMI 210 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 99.8 |

| AB008414 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 99.8 |

| AB008415 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 99.7 |

| AB008416 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100.0 |

| AF027863 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100.0 |

| AF078893 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 99.8 |

| AF078894 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100.0 |

| L76747 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 99.3 |

| A. fumigatus ATCC 36607 | ||||

| IMI 196 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 99.2 |

| AF078889 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 99.7 |

| AF078890 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 99.8 |

| AF078891 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 99.8 |

| AF078892 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 99.8 |

| A. nidulans ATCC 10074 | ||||

| IMI 231 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 99.3 |

| L76746a | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100.0 |

| U03521a | NAc | 2 | 2 | 99.6 |

| A. niger ATCC 16888 | ||||

| IMI 026 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100.0 |

| AF078895 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100.0 |

| AJ223852 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 99.2 |

| L76748 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100.0 |

| U65306 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100.0 |

| A. terreus ATCC 16792 | ||||

| IMI 203 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 99.3 |

| AF078896 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100.0 |

| AF078897 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100.0 |

| AJ001334 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100.0 |

| AJ001335 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100.0 |

| AJ001338 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100.0 |

| AJ001368 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 99.8 |

| L76774 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100.0 |

| U93684 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 99.5 |

| A. ustus UAMH 9479 | ||||

| IMI 192b | 0 | 1 | 1 | 99.8 |

Deposited into GenBank as E. nidulans.

Deposited into the ATCC as ATCC 201953.

NA, not available.

TABLE 2.

Matrix of ITS 1–5.8S–ITS 2 similarities for referenced Aspergillus species

| Strain | % Similarity with strain:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

A. flavus ATCC 16883 |

A. fumigatus ATCC 36607 |

A. nidulans ATCC 10074 |

A. niger ATCC 16888 |

A. terreus ATCC 16792 |

sa A. ustus ATCC 201953 |

|

| A. flavus ATCC 16883 | ||||||

| A. fumigatus ATCC 36607 | 87.6 | |||||

| A. nidulans ATCC 10074a | 81.5 | 84.3 | ||||

| A. niger ATCC 16888 | 89.6 | 91.7 | 84.0 | |||

| A. terreus ATCC 16792 | 87.0 | 91.1 | 83.0 | 90.6 | ||

| A. ustus ATCC 201953 | 82.7 | 80.7 | 91.4 | 80.5 | 79.3 | |

Accepted into GenBank as E. nidulans.

Clinical isolate identification study.

Eleven isolates of various Aspergillus species previously identified by the UNMC Mycology Laboratory were selected by one of us (P.I.) and inoculated onto SAB agar and incubated at 30°C for 24 h. There were three A. fumigatus isolates, two A. flavus isolates, one A. ustus isolate, two A. terreus isolates, two A. niger isolates, and one A. nidulans isolate. The plates were coded and presented for processing by a second person (T.H.). An approximately 2-mm2 section of the agar at the site of inoculation was taken for DNA extraction and amplification. The amplicons were purified using the Qiagen PCR purification kit and sequenced directly. Sequence analysis of Aspergillus specimens was performed using an advanced, nongapped BLAST search with expectation frequency set to 0.0001 and no filtering for low complexity. The search was performed following the deposition and acceptance of sequences from referenced isolates into GenBank. Species identification was determined from the highest bit score of the species listed from the BLAST search. The amount of time from submission of the culture plates to identification was determined.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The ITS 1–5.8S–ITS 2 gene complex sequences of referenced Aspergillus species not previously available within the National Center for Biotechnology Information GenBank or EMBL databases were submitted to GenBank. The assigned sequence accession numbers are as follows: A. flavus (ATCC 16883), AF138287; A. fumigatus (ATCC 36607), AF138288; A. niger (ATCC 16888), AF138904; A. terreus (ATCC 16792), AF138290; A. ustus (ATCC 201953), AF157507; A. nidulans (ATCC 10074) (accepted into GenBank as Emericella nidulans), AF138289. Sequences from other fungal species also deposited into GenBank are listed in Table 4.

RESULTS

Analysis of the ITS regions.

Amplification of the ITS 1–5.8S–ITS 2 regions from the six clinically relevant Aspergillus strains generated PCR products ranging in size from 565 to 613 bp (Table 1). Sequencing was first performed on cloned amplicons and then repeated using direct sequencing of PCR products, with comparisons between results from both methods made. Although a Taq polymerase with proofreading capability was used in the generation of amplicons, an examination for potential variation in sequence due to random base changes introduced by the amplification process was made. Two clones from each reference strain for each species were sequenced. The sequence of cloned PCR products varied by no more than two nucleotides from the sequence of amplicons directly sequenced. Minimal differences in amplicon length between referenced and clinical strains of the same species were seen.

TABLE 1.

Aspergillus species PCR products

| Aspergillus sp. | Source | Size (bp)a |

|---|---|---|

| A. flavus | ATCC 16883 | 595 |

| A. flavus | Clinical isolate | 595 |

| A. fumigatus | ATCC 36607 | 596 |

| A. fumigatus | Clinical isolate | 598 |

| A. nidulans | ATCC 10074 | 565 |

| A. nidulans | Clinical isolate | 569 |

| A. niger | ATCC 16888 | 599 |

| A. niger | Clinical isolate | 599 |

| A. terreus | ATCC 16792 | 609 |

| A. terreus | Clinical isolate | 613 |

| A. ustus | UAMH 9479 | 570 |

| A. ustus | Clinical isolateb | 570 |

Includes the complete ITS 1–5.8S–ITS 2 regions and portions of the 18S (30 bp) and 28S (59 bp) rRNA genes.

Deposited into the ATCC as ATCC 201953.

Alignment of contiguous fungal sequences demonstrated that both single-nucleotide differences and short lengths of sequence diversity due to insertions or deletions existed in the ITS 1–5.8S–ITS 2 regions among the pathogenic Aspergillus species (Fig. 1). The ITS 1 region displayed more interspecies variation than the ITS 2 region, with approximately four separate variable regions. ITS 2 contained two variable regions ranging from 6 to 10 bp in length. A matrix analysis of the sequence similarity between ITS 1 and 2 sequences of the referenced Aspergillus species is depicted in Table 2. The greatest similarity among pathogenic species existed between A. fumigatus and A. niger, with 52 nucleotide base differences (91.7% similarity), whereas A. ustus and A. terreus showed the greatest diversity, with differences at 128 nucleotide positions (79.3% similarity). Aspergillus ITS sequences generated in our laboratory from ATCC strains were compared with all Aspergillus sequences available in GenBank following the deposition of sequences listed in Table 3. For A. flavus, A. fumigatus, and A. terreus, the interspecies sequence similarity with all Aspergillus GenBank sequences (referenced and nonreferenced) was found to be less than 99%. A sequence similarity of 99% between A. nidulans (accepted into GenBank as E. nidulans) and Emericella quadrilineata was observed. A sequence similarity of 99% was also found among species within the A. niger aggregate including A. phoenicis and A. tubigensis.

Sequence similarity of clinical isolates and reference strains of the same species.

The results of comparisons between clinical isolates and referenced strain sequences of the same Aspergillus species are shown in Table 3. The greatest intraspecies variation was seen among isolates of A. fumigatus and isolates of A. niger. For both species, five nucleotide base differences between the sequences of clinical isolates and that of the referenced strain existed. Considering the length of the ITS region amplified, the overall sequence similarity between the referenced Aspergillus strains and clinical isolates of the same species was greater than 99%.

Sequence comparisons with other true pathogenic and opportunistic fungi.

To evaluate the utility of ITS sequences for identification of true pathogenic and opportunistic fungi, the ITS 1–5.8S–ITS 2 region sequences of 12 different genera known to cause infection in humans were determined in our laboratory and compared to sequences from the six medically important aspergilli. The results obtained with A. fumigatus are shown in Table 4. Sequence similarities between A. fumigatus and the listed genera ranged from 50.2 to 89.6%, with Penicillium species showing the greatest sequence similarity. BLAST search comparisons between the other medically important Aspergillus species and all opportunistic fungi available in the GenBank database were also made (data not shown). The ITS 1 and 2 sequences of the referenced Aspergillus species differed from those of the other fungal genera by at least 1%, with one exception: A. niger ITS sequences had 99% sequence similarity with those of Arthrobotrys species and Gliocladium cibotii. As expected, the referenced A. niger sequence was listed first in the bit score rank listing. To further test the system, the sequences of clinical isolates of A. niger were compared using an ungapped BLAST search of the GenBank database. In each case, the clinical isolate was distinguished from Arthrobotrys species and G. cibotii on the basis of bit score.

Clinical validation of ITS sequence analysis.

To determine the utility of the ITS sequence for accurate identification of Aspergillus species, a blind comparison using 11 morphologically confirmed Aspergillus clinical isolates was made. Following incubation of the culture plate for 24 h at 30°C and direct sequencing of PCR amplicons, ITS sequences were used in an ungapped BLAST search of the GenBank database. Identification of the unknown sequences was made using the highest bit score of listed species. By this method, each of the coded specimens was identified correctly as to the Aspergillus species. All of the identifications were made in less than 48 h after receipt of the blind culture plate.

DISCUSSION

The increasing frequency of invasive fungal infection and the high mortality associated with disseminated fungal disease have highlighted the need for rapid identification of infectious molds from clinical samples. The number of cases of IA found at autopsy has increased 14-fold since 1978 (8). Early recognition and treatment of patients with invasive fungal infection are crucial, as the progression of invasive disease from detection to death is typically less than 14 days (4, 25). The present work was based on the premise that identification of Aspergillus at the species level will have clinical importance in the future. Currently, physicians rely on clinical findings and administer AmB empirically to immunosuppressed patients with sign and symptoms consistent with a fungal infection. However, the resistance of certain Aspergillus species to antifungal agents complicates empiric treatment for invasive disease (4, 14, 16). The effectiveness of AmB varies significantly depending on the species of Aspergillus, with over 95% of A. terreus isolates reported as resistant (10, 17, 22). Susceptibility testing has revealed a wide range of AmB MICs, from 0.5 μg/ml for A. niger and A. fumigatus to 16 μg/ml for A. flavus and A. nidulans. Thus, rapid diagnosis and recognition of the species causing infection and treatment with the most active antifungal therapy may be important to reducing the mortality of immunosuppressed patients with IA.

The detection of Aspergillus DNA from blood, serum, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, and tissue has been accomplished by using the 18S rRNA gene as the target (6, 12, 24, 28). Einsele et al. detected Aspergillus DNA from blood approximately 4 days prior to the appearance of pulmonary infiltrates consistent with fungi by computed tomography scan in patients with presumed aspergillosis (6). While their report detailed the shortened time span to positive identification of Aspergillus from patient material, it was not possible to identify Aspergillus at the species level using the 18S rRNA gene (12). Additionally, the identification of aspergilli by PCR in some patient specimens, such as bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, does not always indicate invasive disease, and therefore the use of PCR for detection of fungi in specimens from potentially colonized sites may be limited.

The ITS regions have been used as targets for phylogenetic analysis because they generally display sequence variation between species, but only minor variation within strains of the same species (11, 13, 20, 21). Shin et al. have described a fluorescent DNA probe assay using the ITS 2 region for the identification of Candida species (19). Their approach was reliable for the detection of Candida, as 95.1% of Candida isolates tested were identified to the species level with 100% specificity. In addition, species level identification of six medically relevant Trichosporon isolates was achieved by using a highly variable 12-bp region within the ITS 1 and 2 regions (21). Gaskell et al. investigated sequence variation in ITS regions to distinguish Aspergillus from other allergenic molds (7). They found little variation between Aspergillus and Penicillium within the ITS 2 region but concluded that the ITS 1 region may be sufficient for identification. Although Penicillium capsulatum and Penicillium glabrum exhibited the highest sequence similarity to Aspergillus species in our study, the presence of a 10-bp sequence variation within the ITS 2 region allowed these species to be readily distinguished. We therefore concluded that both the ITS 1 and 2 regions were necessary for species level identification. A limited number of strains were available for some Aspergillus species, particularly A. ustus, which was not previously listed in the GenBank database. Although incomplete, the sequences of GenBank nonreferenced strains showed little difference from those of ATCC referenced strains.

Variation in ITS 2 amplicon size was used by Turenne et al. to identify clinically important fungi using CE for separation and identification (23). They tested 56 fungi and were able to identify 48 at the species level. Similar to our results, they found only a two-nucleotide base difference when comparing the lengths of A. flavus, A. niger, and Fusarium solani ITS amplicons. This suggested that amplicon lengths may not be sufficiently different to distinguish species. We also found A. niger and A. terreus amplicons to be similar in length. The resolution of CE is approximately two nucleotides for amplicons greater than 250 bases in length. It is not clear whether the technical limitations of CE make it a reliable method for species level identification of Aspergillus.

The comparison of ITS 1–5.8S–ITS 2 region sequences among referenced and clinical isolates of six Aspergillus species revealed several areas of sequence variation. The inclusion of the 5.8S rRNA gene sequence had minimal impact on the overall comparison since there is little interspecies variation in this region. In our study, the intraspecies variation among clinical and pathogenic referenced Aspergillus strains was less than 1%. This is consistent with the phylogenetic study by Sugita et al. of the Trichosporon species, where less than 1% of nucleotide bases were different among various strains of the same species (21).

Gaskell et al. have previously shown that Alternaria, Penicillium, Cladosporium, and Aspergillus could be differentiated at the genus level on the basis of ITS sequence analysis (7). The question remained, however, whether ITS sequences could be used to identify any fungus that may be recovered clinically, including those that may be environmental contaminants. In our study, a BLAST search of all GenBank sequences was conducted using the six referenced Aspergillus species ITS sequences. Sequence similarities of less than 89.6% were seen when comparing the ITS region sequences of A. fumigatus to those of other genera, including opportunistic fungi and true pathogenic fungi listed in Table 4. This search also identified two species, A. nidulans and A. niger, that had sequence similarities of 99% with other opportunistic fungi.

A. nidulans (deposited in GenBank as E. nidulans) ITS sequences had 99% sequence similarity with those of E. quadrilineata. However, E. quadrilineata has not been reported as a cause of invasive disease in humans. A. niger ITS sequences were found to be similar to those of nonreferenced isolates of A. phoenicis, A. tubigensis, Arthrobotrys species, and G. cibotii. The A. niger aggregate includes two subgroups and at least 14 species, including A. phoenicis and A. tubigensis, that are morphologically indistinguishable. By contrast, Gliocladium and Arthrobotrys species have morphological features distinct from those of A. niger. Again, none of these species have been associated with invasive disease, and their medical importance is unknown (18). Additional studies to confirm the ITS sequences of referenced isolates of these infrequently encountered fungal species are in progress. Overall, the present results showed that ITS sequence analysis can be used to exclude fungal genera which may be considered in the differential diagnosis of a patient with invasive mycosis. However, the sequence similarity of 99% with some genera and species indicated that the BLAST bit score would be needed to identify clinical isolates of Aspergillus to the species level. A correct identification of clinical isolates of A. niger and A. nidulans was made using the highest bit score of listed species from the BLAST search. This demonstrated that ITS 1 and 2 sequence analysis can be used for recognition of many fungal genera, including those that do not typically cause invasive disease such as airborne allergenic fungi.

Our studies showed that it was not necessary to clone the PCR products to obtain an accurate reading of the sequence. The elimination of this step allowed for direct automated sequencing of PCR products and significantly reduced the amount of time involved in obtaining a result. The ability to sample small (approximately 2-mm2) portions of the culture contributed significantly to rapid identification. Colonies of this size generally cannot be used for morphological identification, and in most cases the specimen must be incubated for 5 days or longer. The ability to rapidly and accurately identify Aspergillus species from blind samples, with results available within 48 h, confirmed the value of this approach. Several issues may affect the time required to obtain a result, including the availability of a dedicated sequencer. The need to repeat the sequencing procedure due to gel compression or contamination may also delay the process. Although automated sequencing and analysis provided accurate discrimination of Aspergillus from other fungi, a probe-based DNA hybridization approach for other organisms has been described and may be more cost effective in the future (6, 19).

Identification of medically important Aspergillus species from short-term culture using nucleic acid sequence analysis of the ITS 1 and 2 regions in combination with a BLAST bit score is a reliable and efficient method that provides earlier identification than standard culture methods. The identification of rarely encountered opportunistic organisms following sequence analysis should prompt a review of the sequence data and correlation with clinical findings. Investigations are in progress to determine whether the method has utility for direct identification of fungi in tissue sections where histologic evidence of a fungus exists. Additional studies are needed to demonstrate whether identification of Aspergillus at the species level will improve patient outcome through the selection of more-effective antifungal therapy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Stefano Tarantolo for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported in part by a UNMC Dean's Research Award to S.H.H.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S F, Madden T L, Schaffer A A, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman D J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beck-Sague C, Jarvis W R. Secular trends in the epidemiology of nosocomial fungal infections in the United States, 1980–1990. National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance System. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:1247–1251. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.5.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bretagne S, Costa J M, Marmorat-Khuong A, Poron F, Cordonnier C, Vidaud M, Fleury-Feith J. Detection of Aspergillus species DNA in bronchoalveolar lavage samples by competitive PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1164–1168. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.5.1164-1168.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Denning D. Invasive aspergillosis. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:781–805. doi: 10.1086/513943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Denning D W. Therapeutic outcome in invasive aspergillosis. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;23:608–615. doi: 10.1093/clinids/23.3.608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Einsele H, Hebart H, Roller G, Loffler J, Rothenhofer I, Muller C A, Bowden R A, van Burik J, Engelhard D, Kanz L, Schumacher U. Detection and identification of fungal pathogens in blood by using molecular probes. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1353–1360. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.6.1353-1360.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaskell G J, Carter D A, Britton W J, Tovey E R, Benyon F H, Lovborg U. Analysis of the internal transcribed spacer regions of ribosomal DNA in common airborne allergenic fungi. Electrophoresis. 1997;18:1567–1569. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150180914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Groll A, Shah P, Mentzel C, Schneider M, Just-Neubling G. Trends in the postmortem epidemiology of invasive fungal infections at a university hospital. J Infect. 1996;33:23–32. doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(96)92700-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guarro J, Gene J, Stchigel A M. Developments in fungal taxonomy. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12:454–500. doi: 10.1128/cmr.12.3.454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iwen P, Rupp M, Langnas A, Reed E, Hinrichs S. Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis due to Aspergillus terreus: 12-year experience and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:1092–1097. doi: 10.1086/520297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee C H, Helweg-Larsen J, Tang X, Jin S, Li B, Bartlett M S, Lu J J, Lundgren B, Lundgren J D, Olsson M, Lucas S B, Roux P, Cargnel A, Atzori C, Matos O, Smith J W. Update on Pneumocystis carinii f. sp. hominis typing based on nucleotide sequence variations in internal transcribed spacer regions of rRNA genes. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:734–741. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.3.734-741.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Melchers W J, Verweij P E, van den Hurk P, van Belkum A, De Pauw B E, Hoogkamp-Korstanje J A, Meis J F. General primer-mediated PCR for detection of Aspergillus species. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1710–1717. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.7.1710-1717.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mitchell T G, White T J, Taylor J W. Comparison of 5.8S ribosomal DNA sequences among the basidiomycetous yeast genera Cystofilobasidium, Filobasidium and Filobasidiella. J Med Vet Mycol. 1992;30:207–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moore C B, Law D, Denning D W. In-vitro activity of the new triazole D0870 compared with amphotericin B and itraconazole against Aspergillus spp. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1993;32:831–836. doi: 10.1093/jac/32.6.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nucci M, Spector N, Bueno A P, Solza C, Perecmanis T, Bacha P C, Pulcheri W. Risk factors and attributable mortality associated with superinfections in neutropenic patients with cancer. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:575–579. doi: 10.1093/clind/24.4.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oakley K L, Moore C B, Denning D W. In vitro activity of SCH-56592 and comparison with activities of amphotericin B and itraconazole against Aspergillus spp. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1124–1126. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.5.1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rath P. Susceptibility of Aspergillus strains from culture collections to amphotericin B and itraconazole. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1998;41:567–570. doi: 10.1093/jac/41.5.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sampson R A. Current systematics of the genus Aspergillus. In: Powell K A, Renwick A, Peberdy J F, editors. The genus Aspergillus. From taxonomy and genetics to industrial application. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1994. pp. 261–276. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shin J H, Nolte F S, Holloway B P, Morrison C J. Rapid identification of up to three Candida species in a single reaction tube by a 5′ exonuclease assay using fluorescent DNA probes. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:165–170. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.1.165-170.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shin J H, Nolte F S, Morrison C J. Rapid identification of Candida species in blood cultures by a clinically useful PCR method. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1454–1459. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.6.1454-1459.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sugita T, Nishikawa A, Ikeda R, Shinoda T. Identification of medically relevant Trichosporon species based on sequences of internal transcribed spacer regions and construction of a database for Trichosporon identification. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1985–1993. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.6.1985-1993.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sutton D, Sanche S, Revankar S, Fothergill A, Rinaldi M. In vitro amphotericin B resistance in clinical isolates of Aspergillus terreus, with a head-to-head comparison to voriconazole. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2343–2345. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.7.2343-2345.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Turenne C Y, Sanche S E, Hoban D J, Karlowsky J A, Kabani A M. Rapid identification of fungi by using the ITS2 genetic region and an automated fluorescent capillary electrophoresis system. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1846–1851. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.6.1846-1851.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Burik J, Myerson D, Schreckhise R, Bowden R. Panfungal PCR assay for detection of fungal infection in human blood specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1169–1175. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.5.1169-1175.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.von Eiff M, Roos N, Schulten R, Hesse M, Zuhlsdorf M, van de Loo J. Pulmonary aspergillosis: early diagnosis improves survival. Respiration. 1995;62:341–347. doi: 10.1159/000196477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.White T, Burns T, Lee S, Taylor J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In: Innis M A, Gelfand D H, Sninsky J J, White T J, editors. PCR protocols. A guide to methods and applications. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press, Inc.; 1990. pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamakami Y, Hashimoto A, Tokimatsu I, Nasu M. PCR detection of DNA specific for Aspergillus species in serum of patients with invasive aspergillosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2464–2468. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.10.2464-2468.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamakami Y, Hashimoto A, Yamagata E, Kamberi P, Karashima R, Nagai H, Nasu M. Evaluation of PCR for detection of DNA specific for Aspergillus species in sera of patients with various forms of pulmonary aspergillosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:3619–3623. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.12.3619-3623.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]