ABSTRACT

When pathogens and their movement between people cannot be seen, we imagine them. That imagined menagerie—imaginerie—of infection then becomes associated with marginal others whose bodies and actions become popularly conflated with disease and its transmission. This essay explores how methods of imagining and managing the COVID‐19 pandemic in Australia echoed historical scripts for policing borders and containing the bodies of outsiders deemed threats to the national body.

Keywords: COVID‐19, infectious disease, containment, monsters, policing, proximity

“We just have to assume the monster is everywhere.” A headline in the August 2, 2020, Washington Post expressed the global pandemic imaginary: COVID‐19 as the invisible monster of modern society (Achenbach, Weiner, and Janes 2020). Similarly, a headline in the Australian on April 8, 2020, read “Coronavirus: Monster” (Stewart 2020). Fear of unknown sickness and death drives representations of infectious disease as an invisible monster. As people imagine its threat, they project their fears of a virus onto groups in society that they imagine are spreading it, people whose bodies or actions become the visible face of an invisible pathogen (Strong 2021, this issue). For individuals trying to understand contagion, invisible monstrosity gets mapped onto the quotidian lives of the Other. It's a tale as old as infectious disease: epidemics go hand in hand with outbreaks of xenophobia (Onoma 2020).

At an epidemiological scale, infectious disease strikes along predictable fault lines of age, race, class, and other forms of social privilege. But at an individual scale, infectious disease proves less predictable. With every breath of air and mouthful of food or water, each human takes in potentially pathogenic microbes— viruses, bacteria, protozoa, fungi, and prions—most of which science knows little about (Nathan Wolfe 2012). And if science knows little, the average human knows much less. The COVID‐19 pandemic has driven home an enduring fact about the human experience of infectious disease: most people will never know what biological pathogen caused an illness or exactly how they acquired it. Whether testing is based on exposure or symptoms, most of those tested do not have COVID‐19 (Wu and McGoogan 2020). Many pathogens cause similar symptoms. Meanwhile, those who do test positive for COVID‐19 manifest a gamut of symptoms and severity. Up to half are asymptomatic (Li et al. 2020). The mysteriousness of pathogens and contagion means that humans are constantly engaged in interpretive work to reconcile symptoms with their understandings of disease and transmission.

For anthropologists, the value of thinking about diseases as monsters lies in the way it marries individual imaginations and cultural texts. Monsters, after all, are “meaning machines” (Musharbash and Presterudstuen 2020, 1) that tell stories about our own fears—and the sometimes monstrous ways we seek to conquer them. As Thomas Strong (2021, this issue) notes, “blame seems instinctual in the face of contagion”; our job as anthropologists is to break down the seeming obviousness of that blame.

In the COVID‐19 era, Australians have been caught up in the witch hunt (Douglas 1991) for those who socialize transgressively or cross borders with the virus, especially those deemed outsiders. But these are not sui generis individual imaginations; they are generated in national discourses and histories of power and transmitted through tabloid spectacle. Like New Zealand (described by Susanna Trnka [2021, this issue]), Australia is an island (fortress) nation surrounded by an ocean (moat), a nation with a long history of both policing incoming travelers for biological contaminants and constructing problems of “contaminants” already inside its borders—whether diseases, imported feral animals such as cane toads, or nonwhite immigrants (Hage 2000): a palimpsest of pollutants (Douglas 1966) at different scales. The country's distinctive spatial distance from the rest of the world shaped the policy framing of the pandemic as a contagion that was simultaneously external and, potentially, a threat within. The pandemic thus became a national problem of proximity, and narratives about COVID‐19 and public health policies for containing it resonate with histories of policing borders and deploying state power to contain racial and social others. This includes the military containment of refugees and the exclusion of HIV‐positive foreigners.

The conflation of biological contagion and national security threats in Australia has been promulgated through a public theater of military‐police enforcement of COVID‐19 quarantine laws. Yet at the same time, vivid political imaginations of contagious otherness are twinned with a striking lack of imagination about the conditions of life and virus transmission among those who differ from Australia's predominantly white, privileged, male politicians. Australia's imaginerie (portmanteau: imaginary + menagerie) of contagion reveals a nationally distinctive ethics of proximity and otherness, wedded to spectacles of state power.

Analyzing such “spectacles” constitutes a critical component of fieldwork during a pandemic. In 2020, Australians accessed news more than usual, driven by isolation and worry about COVID‐19 (Park et al. 2020). As Trnka (2021, this issue) has shown with her analysis of the production of media spectacles of outrage (when she describes a journalist's documentation of police confronting a surfer violating a Kiwi lockdown law), anthropologists must attend to pandemic media coverage, how it intertwines with state policy, the narratives being crafted, and how people engage those narratives in their everyday lives.

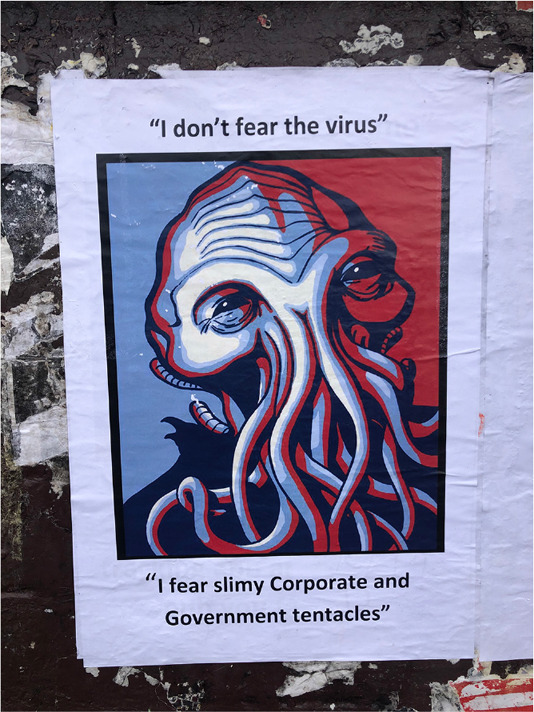

Figure 1.

Paste‐up sign photographed in Sydney on June 2, 2020, in the wake of a government proposal that all residents install a tracking app on their phones for contact tracing and notification. Photo by Saffaa Hassanein. Poster artist anonymous.

PROXIMITY AND PLEASURE IN OUTDOOR SPACES

One of the earliest spectacles of fear of infectious otherness that exemplified the pandemic imaginerie in Australia occurred in Sydney. Its iconic tourist destination Bondi Beach has served as the backdrop of several popular television shows such as Bondi Rescue, in which glamorously fit and almost exclusively white lifeguards are filmed saving brown tourists and immigrants from drowning. A cluster of infections in a Bondi hostel in late March 2020 led to the neighborhood's identification as a “hotspot” of COVID‐19 transmission. Although the infection cluster was connected to hotels serving international backpacking tourists, tabloid coverage ran photographs of late‐summer beachgoers, foreshortened to make the beach appear closely crowded. Public outrage over these spectacles of proximity and hedonism soon led to the state closing Bondi and other beaches.

Figure 2.

A sign on a northern Sydney beach announcing that the beach was closed for social and leisure activities such as picnicking and “sunbaking,” but that sand exercise and swimming were permitted. Photo by David Inglis.

The beach closures and other lockdown laws limiting the use of outdoor spaces had little to do with actual proximity or objective transmission risk—after all, newspapers were full of stories of police fining individuals sitting alone in parks, and transmission in Bondi had been traced to hotels, not beaches. On closer examination, we see that portrayals of contagion and danger revolved around imaginations of contact between locals and tourists. Bondi Beach closed one day after Australia had shut its borders to international tourists on March 2, 2020—a closure that left many travelers still in Australia. Not long after, one news article reported that police wanted citizens to report anyone congregating too closely, “particularly [those] drinking in the park or backpackers who are international travellers” (Natalie Wolfe 2020).

Australia's lockdown law enforcement in outdoor spaces was also grounded in a failure to imagine the living conditions of the non‐middle class. For example, in April 2020 a man was fined A$1,000 (US$775) for eating a kebab on a park bench in Newcastle. News broadcasters and social media posters repeatedly quipped, “Hope the sandwich was worth it!” suggesting this public meal was an indulgence. Such representations evidence an inability to imagine a life in which one might not have a home in which to consume lunch (cf. Kochhar 2020).

Then there was the case of two Indigenous rugby players, Latrell Mitchell and Josh Addo‐Carr, who posted images on social media of themselves camping with friends in April 2020. This led to shaming in the media and threats of police investigation for breaking lockdown laws that prohibited being outdoors in groups larger than two. Subsequent public statements from the football players carefully balanced apology with references to Aboriginal traditions of transmitting cultural knowledge in the bush. At a time when Prime Minister Scott Morrison insisted that schools and workplaces remain open, arguing that these indoor gatherings were necessary to learning and the national economy, Indigenous people were shamed for gathering outdoors.

In short, certain forms of proximity and socialization were deemed virtuous or necessary, while others peripheral to dominant norms were banned. Just as Strong (2021, this issue) and Trnka (2021, this issue) describe for Ireland and New Zealand, respectively, the Australian pandemic response reflects the privileging of particular intimacies (middle class, monogamous, heterosexual, nuclear households) over others.

It is not merely an irony of developing epidemiological knowledge that we now know that cases of outdoor COVID‐19 transmission are rare, making Australia's lockdown prohibitions against outdoor gatherings absurd. As these examples illustrate, fining people for being outdoors was not about proximity, even as it was defended in the name of virtuous social distancing. These laws and their enforcement reflected not public health logic but rather a spectacle of the police containment of otherness.

FORCIBLE CONTAINMENT AND BORDER POLICING

In juxtaposition to Susan Levine and Lenore Manderson's (2021, this issue) description of how the South African state's insufficient COVID‐19 intervention was tied to existing structures of privilege, in Australia, the pandemic response has included some strikingly theatrical state interventions that reinforced existing structures of privilege. Perhaps the most vivid spectacle of containment and otherness in 2020 was the July quarantine of public housing apartment towers in Melbourne. After the identification of some COVID‐19 cases in these high‐rise buildings, the state government forcibly quarantined the inhabitants of all nine towers without prior warning. Residents were banned from leaving for five days. Police surrounded the towers with the same police tape used to cordon off crime scenes. This was despite the fact that some of the towers had no diagnosed cases of COVID‐19 at the time (Fowler and Booker 2020).

The government's chief health officer justified the action by likening the towers—where poor people, refugees, ethnic minorities, recent immigrants, and people with disabilities are overrepresented—to “vertical cruise ships.” He referred to the ships whose primarily white passengers had previously been allowed to disembark in Sydney, leading to many of Australia's early COVID‐19 cases (NSW Government 2020). Yet, belying the claim that the towers lockdown was a race‐blind strategy to avoid past errors, Melbourne academics pointed out that while police forcibly contained the public housing towers, similarly sized infection clusters in wealthy Melbourne suburbs were not locked down (Kelly, Shaw, and Porter 2020).

Australia's loudest racist politician, Pauline Hanson, ranted that the tower residents were “drug addicts” from “non‐English speaking backgrounds” (Zhou and Simons 2020), giving voice to the racist belief in otherness as the visible face of invisible contagion and in containment as deserved. The press photographed tower residents staring out with hands pressed to windows, rendering a pathological menagerie of otherness, with majority Australia staring back at imprisoned people through the media's camera lenses.

Just as Carolyn M. Rouse (2021, this issue) juxtaposes white resistance to pandemic restrictions with Black vulnerability to COVID‐19 to illustrate how racial privilege works in the United States, so too has the Australian targeting and containment of ethnic and national others in COVID‐19 restrictions reflected particular national histories of privilege, containment, and exclusion. The country has a long history of forcibly turning back asylum‐seekers on boats (with sometimes devastating loss of life) and imprisoning them extraterritorially on Manus Island and Nauru for years while their refugee claims are processed (Boochani 2018). Australia's immigration laws explicitly discriminate against HIV and TB‐positive people, requiring HIV tests and lung X‐rays with long‐term visa applications and denying visas to most who test positive (Brotherton 2016; Hegarty 2020). Pandemic management is coterminous with assertions of territorial and national integrity, and containment policies reflect long pedigrees of Australian discourse on the threats of foreign bodies and “invisible enemies” (Caduff 2020, 21).

In Australia, several states have staged a theater of military‐police enforcement of quarantine. For example, in April 2020 New South Wales police circulated images to news media showing teams of police officers and soldiers knocking on doors to ensure that recently arrived travelers were in isolation. In August, the state of Victoria did the same in Melbourne. Why were soldiers deployed to visit homes of unarmed residents? This spectacle of excess force in support of the government's isolation laws theatrically converted the ephemeral danger of the potentiality of unseen pathogens into a physical danger that must be met by an armed military‐police state. Such spectacles make state power, and its expansion in a moment of public health emergency, visible to the populace. They also offer a pleasure to those viewing the spectacle (Foucault 1977): the satisfaction (or perhaps relief) of being able to see a threat as concrete and containable.

As Gracie Mae Bradley (2020) wrote in the Guardian, the police enforcement of COVID‐19 laws—which the Australian government assured us would be used with “discretion”—necessarily raises the specter of how discretionary enforcement always falls along racial lines. A number of analysts have drawn our attention to the novel forms of biopower and governmentality that pandemics engender (Lynteris and Poleykett 2018; European Journal of Psychoanalysis 2020; Manderson 2020; Rouse 2020; Trnka 2020). Government authorities are using COVID‐19 to introduce new forms of surveillance and control over our intimate lives, and its lockdown laws discipline us into particular dominant forms of sociality, namely, a retreat to the middle‐class heterosexual nuclear family (Lewis 2020; Strong 2021, this issue). Yet as the pandemic response in Australia has fashioned an ethics of proximity defined by borders, containment, and the forcible exclusion of otherness, it has drawn on not‐at‐all‐novel discourses on monstrousness, hidden threats, and foreign bodies. Imaginations of invisible pathogens recapitulate well‐trodden narratives about the relationship between biological and social contagion, public policy, and a military‐police complex.

NOTES

Acknowledgments This research was supported by the Social Science Research Council's Rapid‐Response Grants on COVID‐19 and the Social Sciences and by the Australian Research Council Special Research Initiative for Australian Society, History and Culture. Thanks to Samuel Brennan, Susan Levine, Lenore Manderson, Carolyn Rouse, Thomas Strong, and Susanna Trnka for feedback on earlier versions of this essay.

REFERENCES

- Achenbach, Joel , Weiner Rachel, and Janes Chelsea 2020. “Coronavirus Threat Rises across U.S.: ‘We just have to assume the monster is everywhere.‘” Washington Post, August 1. https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/coronavirus-threat-rises-across-us-we-just-have-to-assume-the-monster-is-everywhere/2020/08/01/cdb505e0-d1d8-11ea-8c55-61e7fa5e82ab_story.html.

- Boochani, Behrouz 2018. No Friend but the Mountain: Writing from Manus Prison. Translated by Tofighian Omid. Sydney: Picador. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, Gracie Mae 2020. “Can People of Colour Trust the UK Covid‐19 Laws with the Police's Track Record?” Guardian (UK), March 31. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/mar/31/people-colour-covid-19-laws-police-track-record.

- Brotherton, Alan 2016. “‘The circumstances in which they come’: Refiguring the Boundaries of HIV in Australia.” Australian Humanities Review 60:44–61. http://australianhumanitiesreview.org/2016/11/29/the-circumstances-in-which-they-come-refiguring-the-boundaries-of-hiv-in-australia/. [Google Scholar]

- Caduff, Carlo 2020. “What Went Wrong: Corona and the World after the Full Stop.” Medical Anthropology Quarterly 34, no. 4:467–87. 10.1111/maq.12599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, Mary 1966. Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, Mary 1991. “Witchcraft and Leprosy: Two Strategies of Exclusion.” Man 26, no. 4:723–36. 10.2307/2803778. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- European Journal of Psychoanalysis , ed. 2020. “Coronavirus and Philosophers.” European Journal of Psychoanalysis. http://www.journal-psychoanalysis.eu/coronavirus-and-philosophers/.

- Foucault, Michel 1977. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Translated by Sheridan Alan. New York: Pantheon Books. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler, Michael , and Booker Chloe 2020. “Anger at Hard Lockdown for Towers without Confirmed Virus Cases.” Age, July 5. https://www.theage.com.au/national/victoria/covid-public-housing-wrap-20200705-p5596z.html.

- Hage, Ghassan 2000. White Nation: Fantasies of White Supremacy in a Multicultural Society. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hegarty, Benjamin 2020. “A Place Apart.” Somatosphere (blog), July 15. http://somatosphere.net/2020/a-place-apart.html/.

- Kelly, David , Shaw Kate, and Porter Libby 2020. “Melbourne Tower Lockdowns Unfairly Target Already Vulnerable Public Housing Residents.” The Conversation, July 6, 2020. https://theconversation.com/melbourne-tower-lockdowns-unfairly-target-already-vulnerable-public-housing-residents-142041.

- Kochhar, Rijul 2020. “Disability and Dismantling: Four Reflections in a Time of COVID‐19.” Anthropology Now 12, no. 1:73–75. 10.1080/19428200.2020.1761213. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Levine, Susan , and Manderson Lenore 2021. “Proxemics, COVID‐19, and the Ethics of Care in South Africa.” Cultural Anthropology 36, no. 3:391–99. 10.14506/ca36.3.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, Sophie 2020. “The Virus and the Home.” Bully Bloggers, April 1. https://bullybloggers.wordpress.com/2020/04/01/the-virus-vs-the-home-what-does-the-pandemic-reveal-about-the-private-nuclear-household-by-sophie-lewis-for-bunkerbloggers-originally-published-on-patreon-reblogged-by-permission-of-the-author/.

- Li, Ruiyun , Pei Sen, Chen Bin, Song Yimeng, Zhang Tao, Yang Wan, and Shaman Jeffrey 2020. “Substantial Undocumented Infection Facilitates the Rapid Dissemination of Novel Coronavirus (SARS‐CoV‐2).” Science 368, no. 6490:489–93. 10.1126/science.abb3221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynteris, Christos , and Poleykett Branwyn 2018. “The Anthropology of Epidemic Control: Technologies and Materialities.” Medical Anthropology 37, no. 6:433–41. 10.1080/01459740.2018.1484740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manderson, Lenore 2020. “The Percussive Effects of Pandemics and Disaster: Introduction.” Medical Anthropology 39, no. 5:365–66. 10.1080/01459740.2020.1770749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musharbash, Yasmine , and Presterudstuen Geir Henning 2020. “Introduction: Monsters and Change.” In Monster Anthropology: Ethnographic Explorations of Transforming Social Worlds through Monsters, edited by Musharbash Yasmine and Presterudstuen Geir Henning, 1–27. London: Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar]

- NSW (New South Wales) Government 2020. “Report of the Special Commission of the Inquiry into the Ruby Princess.” August 14. Sydney: State of NSW. https://www.dpc.nsw.gov.au/publications/special-commissions-of-inquiry/the-special-commission-of-inquiry-into-the-ruby-princess/.

- Onoma, Ato Kwamena 2020. “Epidemics, Xenophobia and Narratives of Propitiousness.” Medical Anthropology 39, no. 5:382–97. 10.1080/01459740.2020.1753047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park, Sora , Fisher Caroline, Lee Jee Young, and McGuinness Kieran 2020. “COVID‐19: Australian News and Misinformation.” Canberra, Australia: News and Media Research Centre. https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2020-07/apo-nid306728.pdf.

- Rouse, Carolyn M. 2020. “It's All Free Speech until Someone Dies in a Pandemic.” Anthropology Now 12, no. 1:66–72. 10.1080/19428200.2020.1761212. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rouse, Carolyn M. 2021. “Necropolitics versus Biopolitics: Spatialization, White Privilege, and Visibility during a Pandemic.” Cultural Anthropology 36, no. 3:360–67. 10.14506/ca36.3.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, Cameron 2020. “Coronavirus: ‘Monster’ Slashes New York, City of Death.” Australian, April 8. https://www.theaustralian.com.au/world/coronavirus-monster-slashes-new-york-city-of-death/news-story/5e067dbad492772195cea58fbaecdcde.

- Strong, Thomas 2021. “The End of Intimacy.” Cultural Anthropology 36, no. 3:381–90. 10.14506/ca36.3.05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trnka, Susanna 2020. “Rethinking States of Emergency.” Forum on COVID‐19 Pandemic, Social Anthropology 28, no. 2:367–68. 10.1111/1469-8676.12812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trnka, Susanna 2021. “Be Kind: Negotiating Ethical Proximities in Aotearoa/New Zealand during COVID‐19.” Cultural Anthropology 36, no. 3:368–80. 10.14506/ca36.3.04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe, Nathan 2012. The Viral Storm: The Dawn of a New Pandemic Age. New York: St. Martin's Griffin. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe, Natalie 2020. “Cops Encourage Dobbing to Stem Coronavirus Spread.” News.com.au, April 2. https://www.news.com.au/lifestyle/health/health-problems/coronavirus-australia-live-updates/live-coverage/173cd94e356f69733cb159d02cbfdbfb#43376.

- Wu, Zunyou , and McGoogan Jennifer M. 2020. “Characteristics of and Important Lessons from the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID‐19) Outbreak in China: Summary of a Report of 72,314 Cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention.” Journal of the American Medical Association 323, no. 13:1239–42. 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Naaman , and Simons Margaret 2020. “Today Show Dumps Pauline Hanson for ‘Divisive’ Remarks about Melbourne Public Housing Residents.” Guardian (UK), July 6. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2020/jul/06/today-show-dumps-pauline-hanson-for-divisive-remarks-about-melbourne-public-housing-residents.