Abstract

Selenium, a trace element fundamental to human health, is incorporated as the amino acid selenocysteine (Sec) into more than 25 proteins, referred to as selenoproteins. Human mutations in SECISBP2, SEPSECS and TRU-TCA1-1, three genes essential in the selenocysteine incorporation pathway, affect the expression of most if not all selenoproteins. Systemic selenoprotein deficiency results in a complex, multifactorial disorder, reflecting loss of selenoprotein function in specific tissues and/or long-term impaired selenoenzyme-mediated defence against oxidative and endoplasmic reticulum stress. SEPSECS mutations are associated with a predominantly neurological phenotype with progressive cerebello-cerebral atrophy. Selenoprotein deficiency due to SECISBP2 and TRU-TCA1-1 defects are characterized by abnormal circulating thyroid hormones due to lack of Sec-containing deiodinases, low serum selenium levels (low SELENOP, GPX3), with additional features (myopathy due to low SELENON; photosensitivity, hearing loss, increased adipose mass and function due to reduced antioxidant and endoplasmic reticulum stress defence) in SECISBP2 cases. Antioxidant therapy ameliorates oxidative damage in cells and tissues of patients, but its longer term benefits remain undefined. Ongoing surveillance of patients enables ascertainment of additional phenotypes which may provide further insights into the role of selenoproteins in human biological processes.

Keywords: selenoprotein deficiency, SECISBP2, Sec-tRNA[Ser]Sec, SEPSECS, selenium

1. Introduction

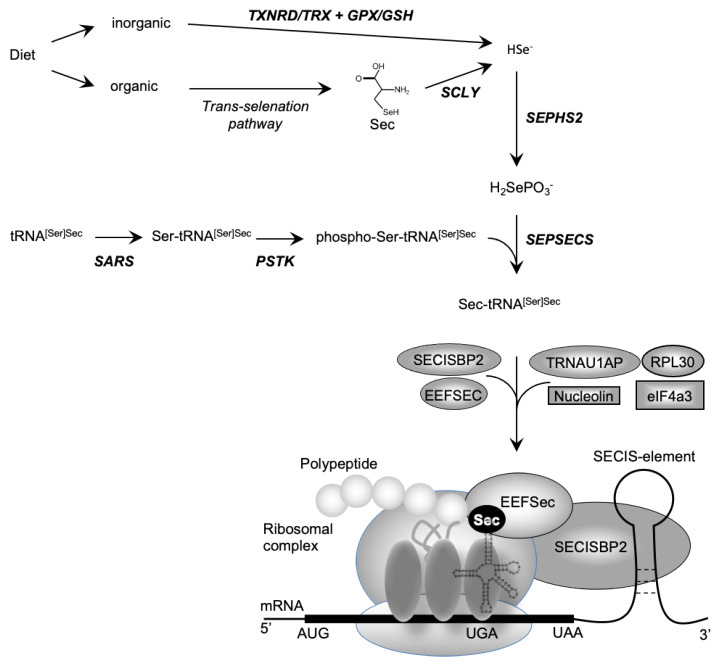

Dietary selenium (Se) is absorbed as inorganic Se (e.g., selenate; selenite) or organic Se (e.g., Se-methionine; selenocysteine) and metabolized to hydrogen selenide (H2Se) before incorporation into the amino acid selenocysteine (Sec) [1]. Selenocysteine is different from other amino acids in that, uniquely, it is synthesized on its own tRNA, (Sec-tRNA[Ser]Sec; encoded by TRU-TCA1-1), via a well described pathway including O-phosphoserine-tRNA:selenocysteine tRNA synthase (SEPSECS) (Figure 1) [2,3]. Selenocysteine is incorporated into selenoproteins, at the position of a UGA codon in the mRNA, which ordinarily encodes a termination codon that dictates the cessation of protein synthesis. Unique Sec-insertion machinery, involving a cis-acting SEleniumCysteine Insertion Sequence (SECIS) stem-loop structure located in the 3′-UTR of all selenoprotein mRNAs and the UGA codon, interacting with trans-acting factors (SECIS binding protein 2 (SECISBP2), Sec-tRNA specific eukaryotic elongation factor (EEFSEC) and Sec-tRNA[Ser]Sec) (Figure 1), recodes UGA as a codon mediating Sec incorporation rather than termination of protein translation [3,4,5].

Figure 1.

Biosynthesis of selenocysteine (Sec) and selenoproteins. Dietary sources of selenium exist in inorganic form (e.g., selenate, selenite) and organic form (e.g., Sec, SeMet). Inorganic selenium is reduced to selenide by TXNRD/TRX or GPX/GSH systems and organic selenium is metabolized to Sec, used by SCLY to generate selenide. De novo Sec synthesis takes place on its own tRNA (tRNA[Ser]Sec), which undergoes maturation through sequential modifications (SARS-mediated addition of Ser, PSTK-mediated phosphorylation of Ser), with acceptance of a selenophosphate (generated from selenide by SEPHS2) catalysed by SEPSECS as final step. Expression of selenoproteins requires recoding of an UGA codon as the amino acid Sec instead of a premature stop. The incorporation of Sec is mediated by a multiprotein complex containing SECISBP2, bound to the SECIS element situated in the 3′-untranslated region of selenoproteins, the Sec elongation factor EEFSEC, together with Sec-tRNA[Ser]Sec at the ribosomal acceptor site. The other factors (e.g., ribosomal protein L30, eukaryotic initiation factor eIF4a3, nucleolin) have regulatory roles.

At least 25 human selenoproteins are described and recognized functions include maintenance of redox potential, regulating redox sensitive biochemical pathways, protection of genetic material, proteins and membranes from oxidative damage, metabolism of thyroid hormones, regulation of gene expression and control of protein folding (Table 1) [3,6]. The importance of selenoproteins is illustrated by the embryonic lethal phenotype of Trsp (mouse Sec-tRNA[Ser]Sec) and Secisbp2 knockout mice [7,8]. It is well known that dietary Se intake affects systemic Se-status and selenoprotein expression, but not all selenoproteins are affected to the same extent. Thus, expression of housekeeping selenoproteins (e.g., TXNRD1, TXNRD3, GPX4) is less affected by low circulating Se-levels compared to stress-related selenoproteins (e.g., GPX1, GPX3, SELENOW). Such differential preservation of selenoprotein expression is attributed to the existence of a “hierarchy of selenoprotein synthesis”, whose underlying molecular basis is unclear [3,9]. With this knowledge, it is no surprise that mutations in key components of the Sec-insertion pathway (SEPSECS, SECISBP2, TRU-TCA1-1) result in generalized deficiency of selenoproteins associated with a complex, multisystem phenotypes. Here, we describe the clinical consequences of mutations in these three human genes and suggest possible links with loss-of-function of known selenoproteins.

Table 1.

Human selenoproteins.

| Selenoprotein | Function | Expression Subcellular Localization |

|---|---|---|

| GPX1 glutathione peroxidase 1 |

Oxidoreductase | most tissues cytoplasmic |

| GPX2 glutathione peroxidase 2 |

Oxidoreductase | limited number of tissues Nucleus and cytoplasmic |

| GPX3 glutathione peroxidase 3 |

Oxidoreductase | most tissues secreted |

| GPX4 glutathione peroxidase 4 |

Oxidoreductase | most tissues Nucleus and mitochondria |

| GPX6 glutathione peroxidase 6 |

Oxidoreductase | testis, epididymis, olfactory system predicted secreted |

| TXNRD1 thioredoxin reductase 1 |

Oxidoreductase | Ubiquitous Nucleus and cytoplasmic |

| TXNRD2 Thioredoxin reductase 2 |

Oxidoreductase | Ubiquitous cytoplasmic and mitochondria |

| TXNRD3 Thioredoxin reductase 3 |

Oxidoreductase | most tissues, high in testis Intracellular |

| DIO1 Iodothyronine deiodinase 1 |

Thyroid hormone metabolism | kidney, liver, thyroid gland Intracellular membrane-associated |

| DIO2 Iodothyronine deiodinase 2 |

Thyroid hormone metabolism | central nervous system, pituitary Intracellular membrane-associated |

| DIO3 Iodothyronine deiodinase 3 |

Thyroid hormone metabolism | several tissues Intracellular membrane-associated |

| MSRB1 methionine sulfoxide reductase B1 |

Met sulfoxide reduction | Ubiquitous Nucleus and cytoplasmic |

| SELENOF Selenoprotein F |

Protein folding control | Ubiquitous endoplasmic reticulum |

| SELENOH Selenoprotein H |

Unknown oxidoreductase | Ubiquitous Nucleus |

| SELENOI Selenoprotein I |

Phospholipid biosynthesis | Ubiquitous transmembrane |

| SELENOK Selenoprotein K |

Protein folding control | Ubiquitous ER, plasma membrane |

| SELENOM Selenoprotein M |

Unknown | Ubiquitous Nuclear and perinuclear |

| SELENON Selenoprotein N |

Redox-calcium homeostasis | Ubiquitous endoplasmic reticulum |

| SELENOO Selenoprotein O |

Protein AMPylation activity | Ubiquitous mitochondria |

| SELENOP Selenoprotein P |

Transport/oxidoreductase | most tissues secreted, cytoplasmic |

| SELENOS Selenoprotein S |

Protein folding control | Ubiquitous endoplasmic reticulum |

| SELENOT Selenoprotein T |

Unknown oxidoreductase | Ubiquitous endoplasmic reticulum |

| SELENOV Selenoprotein V |

Unknown | thyroid, parathyroid, testis, brain Intracellular |

| SELENOW Selenoprotein W |

Oxidoreductase | Ubiquitous Intracellular |

| SEPHS2 Selenophosphate synthetase 2 |

Selenophosphate synthesis | Ubiquitous, high in liver and kidney Intracellular |

2. SECISBP2 Mutations

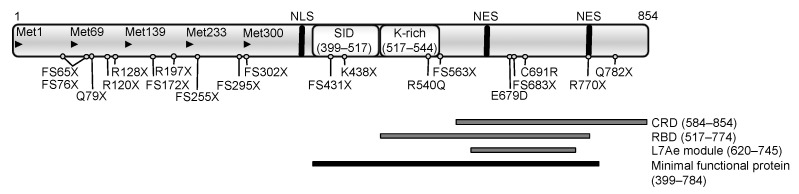

SECISBP2 is an essential and limiting factor for biosynthesis of selenoproteins [4,10] and functions as a scaffold, recruiting ribosomes, EEFSEC, and Sec-tRNA[Ser]Sec to the UGA codon by binding to SECIS-elements in selenoprotein mRNAs, generating a dynamic ribosome-Sec-incorporation complex (Figure 1). The first 400 amino (N-)terminal residues of SECISBP2 have no clear function; in contrast the carboxy (C-)terminal region (amino acids 399–784) is both necessary and sufficient for Sec-incorporation (Sec incorporation domain: SID) and binding to the SECIS element (RNA-binding domain: RBD) in vitro (Figure 2). The RBD, contains a L7Ae-type RNA interaction module and a lysine-rich domain, mediating specific recognition of ‘‘stem-loop’’ structures adopted by SECIS elements and other regulatory RNA motifs [11,12,13]. The C-terminal region also contains motifs (nuclear localization signal; nuclear export signal) involved in cellular localization of SECISBP2 and a cysteine rich domain (Figure 2) [14]. In the N-terminal region, alternative splicing events and ATG start codons have been described, generating different SECISBP2 isoforms [14], but all containing the essential C-terminal region. These events, together with regulatory domains in the C-terminal region, are thought to control SECISBP2-dependent Sec incorporation and the hierarchy of selenoprotein expression in vivo.

Figure 2.

Functional domains of human SECISBP2 with the position of mutations described hitherto. Arrowheads denote the location of ATG codons; NLS: nuclear localisation signal (380–390); NES: nuclear export signals (634–657 and 756–770); SID: Sec incorporation domain; CRD: cysteine rich domain; RBD: minimal RNA-binding domain with the Lysine-rich domain (K-rich) and the L7Ae RNA-binding module; the black bar denotes the minimal protein region required for full functional activity in vitro.

Homozygous or compound heterozygous mutations in SECISBP2 have been described in individuals from 11 families from diverse ethnic backgrounds [15] (Table 2, Figure 2); hitherto no phenotypes have been described in heterozygous individuals. Most SECISBP2 mutations identified to date result in premature stops in the N-terminal region upstream of an alternative start codon (Met 300), permitting synthesis of the shorter, C-terminal, minimal functional domain of SECISBP2 (Figure 2) [14,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23]. Conversely, stop mutations (e.g., R770X, Q782X) [18,23], distal to the minimal functional domain might generate C-terminally truncated proteins with residual but altered function. In one patient with an intronic mutation (IVS8ds + 29G > A) leading to a stop in the SID-domain, correct mRNA splicing was only reduced by 50% [16], a mechanism preserving some SECISBP2 synthesis that may operate in other splice site mutation contexts.

Table 2.

Human SECISBP2 mutations.

| Age in Years (Gender) | Mutation | Protein Change | Alleles Affected |

Ethnicity | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 26 (M 1); 19 (M); 19 (F 2) | c.1619 G > A | R540Q | homozygous | Saudi Arabian |

[16] |

| 25 (M) | c.1312 A > T c.IVS8ds + 29 G > A |

K438 * fs431 * |

compound heterozygous |

Irish | [16] |

| 19 (M) | c.382 C > T | R128 * | homozygous | Ghanaian | [17] |

| 18 (F) | c.358 C > T c.2308 C > T |

R120 * R770 * |

compound heterozygous |

Brazilian | [18] |

| 44 (M) | c.668delT c.IVS7 -155, T > A |

F223fs255 * fs295 * + fs302 * |

compound heterozygous |

British | [19] |

| 13 (M) | c. 2017 T > C 1–5 intronic SNP’s |

C691R fs65 * + fs76 * |

compound heterozygous |

British | [19] |

| 15 (M) | c.1529_1541dup CCAGCGCCCCACT c.235 C > T |

M515fs563 * Q79 * |

compound heterozygous |

Japanese | [20] |

| 10 (M) | c.800_801insA | K267Kfs * 2 | homozygous | Turkish | [21] |

| 3.5 (M) | c.283delT c.589 C > T |

T95Ifs31 * R197 * |

compound heterozygous |

N/A 3 | [22] |

| 11 (F) | c.2344 C > T c.2045–2048 delAACA |

Q782 * K682fs683 * |

compound heterozygous |

Turkish | [23] |

| 5 (F) | c.589 C > T c.2108 G > T or C |

R197 * E679D |

compound heterozygous |

Argentinian | [23] |

1 M: Male; 2 F: Female; 3 N/A: Not available.

Only three missense SECISBP2 mutations, situated in the RBD (R540Q, E679D and C691R) are described. The R540Q mutation, in the lysine-rich domain, fails to bind a specific subset of SECIS-elements in vitro and a mouse model revealed an abnormal pattern of Secisbp2 and selenoprotein expression in tissues [16,24,25]. The E679D and C691R mutations are situated in the L7Ae RNA-binding module and part of the CRD. C691R mutant SECISBP2 undergoes enhanced proteasomal degradation, with loss of RNA-binding [19,25]. The E679D mutation has not been investigated but is predicted to be deleterious (PolyPhen-2 algorithm score of 0.998), possibly affecting RNA-binding [23].

Complete knockout of Secisbp2 in mice is embryonic lethal [8], suggesting some functional protein, or an alternative rescue mechanism, is present in humans with SECISBP2 mutations. Studies suggest that most combinations of SECISBP2 mutations in patients hitherto are hypomorphic, with at least one allele directing synthesis of protein at either reduced levels or that is partially functional (Table 2). Because it is rate limiting for Sec incorporation, decreased SECISBP2 function will affect most if not all selenoprotein synthesis, as confirmed by available selenoprotein expression data in the patients [16,19].

Hitherto, only a small number of patients are described, from different ethnic and geographical backgrounds, often with compound heterozygous mutations and with limited information of their phenotypes. Some clinical phenotypes are attributable to deficiencies of particular selenoproteins in specific tissues whilst other features have a complex, multifactorial, basis possible linked to unbalanced antioxidant defence or protein folding pathways or loss of selenoproteins of unknown function. Increased cellular oxidative stress, readily measurable in most cells and tissues from patients, results in cumulative membrane and DNA damage. A common biochemical signature in all patients consists of low circulating selenium (reflecting low plasma SELENOP and GPX3) and abnormal thyroid hormone levels due to diminished activity of deiodinases resulting in raised FT4, normal to low FT3, raised reverse T3 and normal or high TSH concentrations [15,16,19]. Most cases were diagnosed in childhood with growth retardation (e.g., failure to thrive, short stature, delayed bone age) and developmental delay (e.g., delayed speech, intellectual- and motor coordination deficits) as common features, due not only to abnormal thyroid hormone metabolism [26,27] but also effects of specific selenoproteins deficiency in tissues (e.g., neuronal [8] or skeletal [28]). Fatigue and muscle weakness is a recognized feature in several patients and is attributable at least in part to a progressive muscular dystrophy affecting axial and proximal limb muscles, and very similar to the phenotype of myopathy due to selenoprotein N-deficiency [29]. Mild, bilateral, high-frequency sensorineural hearing loss is observed in some patients and is possibly due to ROS-mediated damage in the auditory system [30,31] as it is progressive in nature, worsening in older patients. An adult male patient was azoospermic, with marked deficiency of testis-expressed selenoproteins (GPX4, TXNRD3, SELENOV) [32,33,34,35,36]. Several other recorded phenotypes (increased whole body, subcutaneous fat mass, increased systemic insulin sensitivity, cutaneous photosensitivity) probably have a multifactorial basis which includes loss of antioxidant and endoplasmic reticulum stress defence. Studies of mouse models and in humans provide a substantial body of evidence to suggest a link between selenoproteins and most of these phenotypes [19,37,38,39,40,41].

Clinical management of these patients is mostly limited to correcting abnormal thyroid hormone metabolism with liothyronine supplementation if necessary. No specific therapies exist for other phenotypes (e.g., myopathy), but their progressive nature can require supportive intervention (e.g., nocturnal assisted ventilation for respiratory muscle weakness, aid for hearing loss). Oral selenium supplementation did raise total serum Se levels in some SECISBP2-deficient patients, but without clinical [17,18,21] or biochemical (circulating GPX’s, SELENOP, thyroid hormone metabolism) effect [42]. Antioxidant (alpha tocopherol) treatment was beneficial in one patient, reducing circulating levels of products of lipid peroxidation with reversal of these changes after treatment withdrawal [40]. These observations suggest that treatment with antioxidants is a rational therapeutic approach, but the longterm consequences in this multisystem disorder are unpredictable.

3. TRU-TCA1-1 Mutations

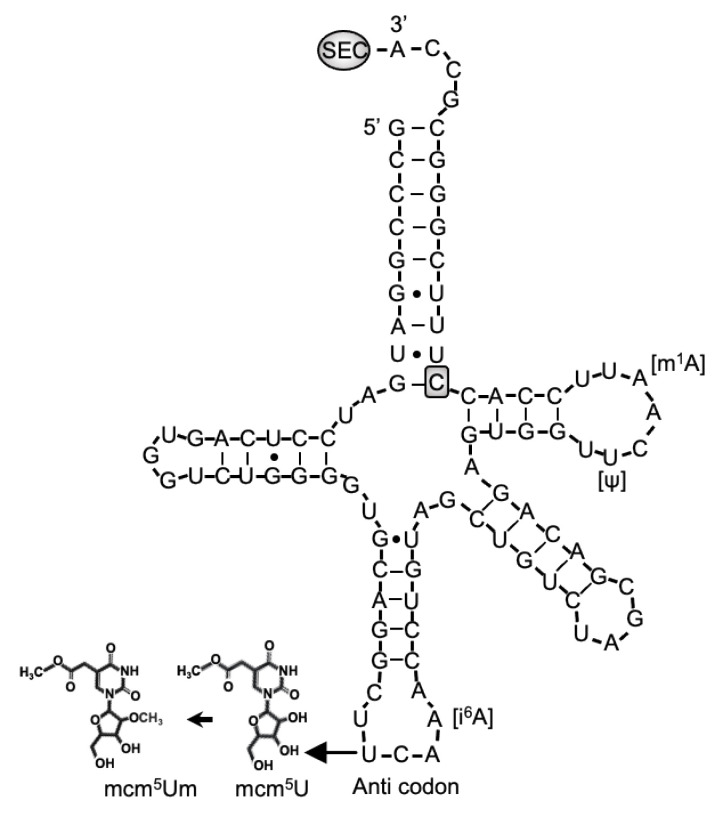

Selenocysteine is different from other amino acids in that it is synthesized uniquely on its own tRNA, encoded by TRU-TCA1-1, via a well described pathway including SEPSECS (Figure 1) [2,3]. Two major isoforms of the mature Sec-tRNA[Ser]Sec have been identified, containing either 5-methoxycarbonyl-methyluridine (mcm5U) or its methylated form 5-methoxycarbonylmethyl-2′-O-methyluridine (mcm5Um) at position 34, with the level of methylation being dependent on selenium status (Figure 3). The methylation state of uridine 34, located in the anticodon loop, is thought to contribute to stabilization of the codon–anticodon interaction and to play a role in mediating the hierarchy of selenoprotein expression. Thus, expression of essential, cellular housekeeping selenoproteins (e.g., TXNRDs, GPX4) is dependent on the mcm5U isoform, whilst synthesis of cellular, stress-related selenoproteins (e.g., GPX1, GPX3) synthesis require the mcm5Um isoform [43,44].

Figure 3.

Sec-tRNA[Ser]Sec showing the position of human mutation. The primary structure of human Sec-tRNA[Ser]Sec is shown in a cloverleaf model, with the location of C65G mutation and posttranscriptional modification at positions U34 (mcm5U or mcm5Um, in the anticodon), A37 (i6A), U55 (⍦) and A58 (m1A).

The first patient with a homozygous nucleotide change at position 65 (C > G) in TRU-TCA1-1 (Figure 3) [45], presented with a similar clinical and biochemical phenotype (fatigue and muscle weakness, raised FT4, normal T3, raised rT3 and TSH, low plasma selenium concentrations) to that seen in patients with SECISBP2 deficiency. However, the pattern of selenoprotein expression in his cells differed, with preservation housekeeping selenoproteins (e.g., TXNRDs, GPX4), but not stress-related selenoproteins (e.g., GPX1, GPX3) in cells from the TRU-TCA1-1 mutation patient. This pattern is similar to the differential preservation of selenoprotein synthesis described in murine Sec-tRNA[Ser]Sec mutant models [3,44]. Recently, a second, unrelated patient with the same, homozygous TRU-TCA1-1 mutation (C65G) with raised FT4 and low plasma GPX3 levels has been described [46].

The mechanism for such differential selenoprotein expression is unresolved, but a possible explanation is the observation that the TRU-TCA1-1 C65G mutation results in lower total Sec-tRNA[Ser]Sec expression in patients cells, with disproportionately greater diminution in Sec-tRNA[Ser]Sec mcm5Um levels. This suggest that the low Sec-tRNA[Ser]Sec levels in the proband are still sufficient for normal synthesis of housekeeping selenoproteins, whereas diminution of Sec-tRNA[Ser]Sec mcm5Um levels accounts for reduced synthesis of stress-related selenoproteins.

Clinical management of the patient is limited to alleviating clinical symptoms. However, with the knowledge that changing systemic selenium status can alter the relative proportions of the Sec-RNA[Ser]Sec isoforms [44,47,48], selenium supplementation of this patient, aiming to restore specific selenoprotein deficiencies, may be a rational therapeutic approach.

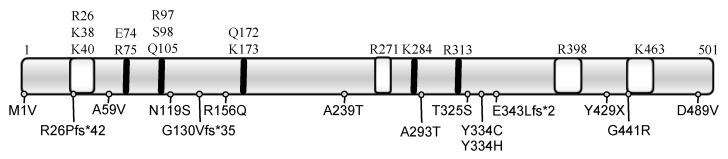

4. SEPSECS Mutations

The human SEPSECS protein was first characterized as an autoantigen (soluble liver antigen/liver pancreas, SLA) in autoimmune hepatitis [49]. The observation that it was present in a ribonucleoprotein complex with Sec-tRNA[Ser]Sec, led to its identification as the enzyme that catalyzes the final step of Sec formation by converting O-phosphoserine-tRNA[Ser]Sec into Sec-tRNA[Ser]Sec using selenophosphate as substrate donor [50,51] (Figure 1).

Homozygous and compound heterozygous mutations in SEPSECS have been identified in 20 patients (Table 3, Figure 4). The availability of the crystal structures of the archaeal and murine SEPSECS apo-enzymes as well as human wild type and mutant SECSEPS (A239T, Y334C, T325S and Y429X) complexed with Sec-tRNA[Ser]Sec provides functional information [52,53,54,55]. The four premature stop mutants are predicted to be insoluble and inactive, as documented for the Y429X mutant. Mutants at Tyrosine 334 are predicted to fold like wild type SEPSECS and retain binding to Sec-tRNA[Ser]Sec, but with reduced enzyme activity. The A239T mutant failed to form stable tetramers, possible as result of a steric clash destabilizing the enzyme’s core, rendering it inactive [55]. The other mutants for which no structure is available have been analyzed in silico and are predicted to be deleterious to varying degrees [15].

Table 3.

Human SEPSECS mutations.

| Age in Year (Gender) | Mutation | Protein Change |

Alleles Affected |

Ethnicity | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 (F 1); 7.5 (2) | c.1001 A > G | Y334C | homozygous | Jewish/Iraq | [56] |

| 4 (F); 2.5 (M) | c.715 G > A c.1001 A > G |

A239T Y334C |

compound heterozygous |

Iraqi/ Moroccan |

[56] |

| 7 (F); 4 (F); 2 (F) |

c.1466 A > T | D489V | homozygous | Jordan | [57] |

| 0 (M); 0 (F); 0 (F); 0 (F) | c.974 C > G c.1287 C > A |

T325S Y429X |

compound heterozygous |

Finnish | [58] |

| 14 (F) | c.1 A > G c.388 + 3 A > G |

M1V G130Vfs * 5 |

compound heterozygous |

N/A 3 | [59] |

| N/A | c.1027–1120del | E343Lfs * 2 | Homozygous | N/A 3 | [60] |

| 9 (M) | c.1001 A > C | Y334H | homozygous | Arabian | [61] |

| 10 (F) | c.77delG c.356 A > G |

R26Pfs * 42 N119S |

compound heterozygous |

Japanese | [62] |

| 21 (F) | c.356 A > G c.467 G > A |

N119S R156Q |

compound heterozygous |

Japanese | [62] |

| 1 (M) | c.176 C > T | A59V | Homozygous | N/A 3 | [63] |

| 23 (F) | c.1321 G > A | G441R | Homozygous | N/A 3 | [64] |

| 4 (F) | c.114 + 3 A > G | N/A 3 | Homozygous | Moroccan | [65] |

| N/A 1 | c.877 G > A | A293T | Homozygous | N/A 3 | [66] |

1 F: Female; 2 M: Male; 3 N/A: Not available.

Figure 4.

Functional domains of SEPSECS with the positions of the human mutations. Schematic of the human SEPSECS protein with key amino acids (above) that are part of the active domain (black bars) or interact with tRNA[ser]sec] (white shaded boxes) and mutations described hitherto below.

Patients with mutations in SEPSECS have profound intellectual disability, global developmental delay, spasticity, epilepsy, axonal neuropathy, optic atrophy and hypotonia with progressive microcephaly due to cortical and cerebellar atrophy [56,58,61,63]. The disorder is classified as autosomal recessive pontocerebellar hypoplasia type 2D (PCH2D, OMIM#613811), also referred to as progressive cerebellocerebral atrophy (PCCA) [56,67]. SEPSECS is required for generation of Sec-tRNA[Ser]Sec, which is essential for survival as demonstrated by the Trsp (mouse tRNA[Ser]Sec) knockout mouse model [44]. The Y334C-Sepsecs mouse model exhibits a phenotype similar to features described in patients [68]. However, there is some variation in impact of SEPSECS mutations and specific phenotypes, with three patients (homozygous for G441R; compound heterozygous for R26Pfs*42/N119S or N119S/R156Q), presenting with late-onset PCH2D and progressive but milder degree of CNS atrophy [62,64]. In silico analyses suggest that these mutations have a less deleterious effect on SEPSECS function [15], although environmental factors or patients’ genetic background modulating phenotype cannot be excluded.

The young age and severity of neurological problems in SEPSECS patients has precluded detailed investigation of selenoprotein expression and associated phenotypes. Studies of brain tissue from some patients showed decreased selenoprotein expression, correlating with increased cellular oxidative stress, but selenoprotein expression in other cell types (fibroblasts, muscle cells) was not significantly affected [58]. Serum selenium concentrations and thyroid status has been partially investigated in five patients, documenting either normal levels [61,65] or normal T4 but elevated TSH levels [58]. This suggests that the biochemical hallmarks of selenoprotein deficiency in SECISBP2 and TRU-TCA1-1 disorders (low circulating selenium and abnormal thyroid hormone levels) are not a significant feature in patients with SEPSECS mutations. Myopathic features with raised CK levels, abnormal mitochondria, cytoplasmic bodies and increased lipid accumulation in muscle are documented in one SEPSECS mutation case [61], with broad-based gait and postural instability suggesting muscle weakness in another patient [64]. These findings are similar to observations in selenoprotein N-deficient patients with SECISBP2 mutations [19]. Overall, limited studies to date suggest that SEPSECS patients exhibit phenotypes associated with selenoprotein deficiency, but that these features can be mutation and tissue dependent.

5. Conclusions

In humans, 25 genes, encoding different selenoproteins containing the amino acid selenocysteine (Sec), have been identified. In selenoprotein mRNAs the amino acid Sec is encoded by the triplet UGA which usually constitutes a stop codon, requiring its recoding by a complex, multiprotein mechanism. Failure of selenoprotein synthesis due to SECISBP2, TRU-TCA1-1 or SEPSECS defects, essential components of the selenoprotein biosynthesis pathway, results in complex disorders.

Individuals with SECISBP2 defects exhibit a multisystem phenotype including growth retardation, fatigue and muscle weakness, sensorineural hearing loss, increased whole body fat mass, azoospermia and cutaneous photosensitivity. Most patients were identified due to a characteristic biochemical signature with raised FT4, normal to low FT3, raised rT3 and normal/slightly high TSH and low plasma selenium levels. A similar biochemical phenotype and clinical features are described in one individual with a TRU-TCA1-1 mutation, although with relative preservation of essential housekeeping versus stress-related selenoprotein expression in his cells. Individuals with SEPSECS defects, essential for Sec-tRNA[Ser]Sec synthesis, present with a disorder characterized by cerebello-cerebral atrophy. Due to the young age and severe phenotype of patients, the effect of SEPSECS mutations on selenoprotein expression has not been studied in detail. In contrast, it is noteworthy that an early-onset central nervous system phenotype is not a feature in patients with SECISBP2 or TRU-TCA1-1 mutations.

As the function of many selenoproteins is unknown, or simultaneous deficiency of several selenoproteins exerts additive, synergistic or antagonistic effects culminating in complex dysregulation, linking disease phenotypes with altered expression of specific selenoproteins is challenging. Nevertheless, some causal links between specific selenoprotein deficiencies and phenotypes (e.g., abnormal thyroid function and deiodinase enzymes; low plasma Se and SELENOP, GPX3; azoospermia and SELENOV, GPX4, TXRND3; myopathy and SELENON) can be made. Other, progressive, phenotypes (e.g., photosensitivity, age-dependent hearing loss, neurodegeneration) may reflect absence of selenoenzymes mediating defence against oxidative and endoplasmic reticulum stress, resulting in cumulative tissue damage.

Triiodothyronine supplementation can correct abnormal thyroid hormone metabolism, with other medical intervention being mainly supportive. Selenium supplementation is of no proven benefit in SECISBP2 mutation patients, but needs evaluation in the TRU-TCA1-1 mutation case. Antioxidants, targeting the imbalance in oxidoredox and protein folding control pathways, could be beneficial in many selenoprotein deficient patients, but due to the complex interplay between different selenoproteins and their role in diverse biological processes, such treatment will require careful evaluation.

Author Contributions

E.S., writing—original draft preparation; K.C., writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Wellcome Trust Investigator Award, grant number 210755/Z/18/Z and the NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ferreira R., Sena-Evangelista K., de Azevedo E.P., Pinheiro F.I., Cobucci R.N., Pedrosa L. Selenium in Human Health and Gut Microflora: Bioavailability of Selenocompounds and Relationship With Diseases. Frontiers in nutrition. 2021;8:685317. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2021.685317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Turanov A.A., Xu X.M., Carlson B.A., Yoo M.H., Gladyshev V.N., Hatfield D.L. Biosynthesis of selenocysteine, the 21st amino acid in the genetic code, and a novel pathway for cysteine biosynthesis. Ad. Nutr. 2011;2:122–128. doi: 10.3945/an.110.000265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Labunskyy V.M., Hatfield D.L., Gladyshev V.N. Selenoproteins: Molecular pathways and physiological roles. Physiol. Rev. 2014;94:739–777. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00039.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Copeland P.R., Fletcher J.E., Carlson B.A., Hatfield D.L., Driscoll D.M. A novel RNA binding protein, SBP2, is required for the translation of mammalian selenoprotein mRNAs. EMBO J. 2000;19:306–314. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.2.306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin G.W., Harney J.W., Berry M.J. Selenocysteine incorporation in eukaryotes: Insights into mechanism and efficiency from sequence, structure, and spacing proximity studies of the type 1 deiodinase SECIS element. RNA. 1996;2:171–182. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zoidis E., Seremelis I., Kontopoulos N., Danezis G.P. Selenium-Dependent Antioxidant Enzymes: Actions and Properties of Selenoproteins. Antioxidants. 2018;7:66–91. doi: 10.3390/antiox7050066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bösl M.R., Takaku K., Oshima M., Nishimura S., Taketo M.M. Early embryonic lethality caused by targeted disruption of the mouse selenocysteine tRNA gene (Trsp) PNAS. 1997;94:5531–5534. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.11.5531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seeher S., Atassi T., Mahdi Y., Carlson B.A., Braun D., Wirth E.K., Klein M.O., Reix N., Miniard A.C., Schomburg L., et al. Secisbp2 is essential for embryonic development and enhances selenoprotein expression. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2014;21:835–849. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sunde R.A., Raines A.M. Selenium regulation of the selenoprotein and nonselenoprotein transcriptomes in rodents. Ad. Nutr. 2011;2:138–150. doi: 10.3945/an.110.000240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Copeland P.R., Driscoll D.M. Purification, redox sensitivity, and RNA binding properties of SECIS-binding protein 2, a protein involved in selenoprotein biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:25447–25454. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.36.25447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caban K., Kinzy S.A., Copeland P.R. The L7Ae RNA binding motif is a multifunctional domain required for the ribosome-dependent Sec incorporation activity of Sec insertion sequence binding protein 2. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007;27:6350–6360. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00632-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donovan J., Caban K., Ranaweera R., Gonzalez-Flores J.N., Copeland P.R. A novel protein domain induces high affinity selenocysteine insertion sequence binding and elongation factor recruitment. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:35129–35139. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806008200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takeuchi A., Schmitt D., Chapple C., Babaylova E., Karpova G., Guigo R., Krol A., Allmang C. A short motif in Drosophila SECIS Binding Protein 2 provides differential binding affinity to SECIS RNA hairpins. Nucleic acids res. 2009;37:2126–2141. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Papp L.V., Lu J., Holmgren A., Khanna K.K. From selenium to selenoproteins: Synthesis, identity, and their role in human health. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2007;9:775–806. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schoenmakers E., Chatterjee K. Human Disorders Affecting the Selenocysteine Incorporation Pathway Cause Systemic Selenoprotein Deficiency. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2020;33:481–497. doi: 10.1089/ars.2020.8097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dumitrescu A.M., Liao X.H., Abdullah M.S., Lado-Abeal J., Majed F.A., Moeller L.C., Boran G., Schomburg L., Weiss R.E., Refetoff S. Mutations in SECISBP2 result in abnormal thyroid hormone metabolism. Nat. Genet. 2005;37:1247–1252. doi: 10.1038/ng1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Di Cosmo C., McLellan N., Liao X.H., Khanna K.K., Weiss R.E., Papp L., Refetoff S. Clinical and molecular characterization of a novel selenocysteine insertion sequence-binding protein 2 (SBP2) gene mutation (R128X) J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009;94:4003–4009. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Azevedo M.F., Barra G.B., Naves L.A., Ribeiro Velasco L.F., Godoy Garcia Castro P., de Castro L.C., Amato A.A., Miniard A., Driscoll D., Schomburg L., et al. Selenoprotein-related disease in a young girl caused by nonsense mutations in the SBP2 gene. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010;95:4066–4071. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schoenmakers E., Agostini M., Mitchell C., Schoenmakers N., Papp L., Rajanayagam O., Padidela R., Ceron-Gutierrez L., Doffinger R., Prevosto C., et al. Mutations in the selenocysteine insertion sequence-binding protein 2 gene lead to a multisystem selenoprotein deficiency disorder in humans. J. Clin. Invest. 2010;120:4220–4235. doi: 10.1172/JCI43653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hamajima T., Mushimoto Y., Kobayashi H., Saito Y., Onigata K. Novel compound heterozygous mutations in the SBP2 gene: Characteristic clinical manifestations and the implications of GH and triiodothyronine in longitudinal bone growth and maturation. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2012;166:757–764. doi: 10.1530/EJE-11-0812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Çatli G., Fujisawa H., Kirbiyik Ö., Mimoto M.S., Gençpinar P., Özdemir T.R., Dündar B.N., Dumitrescu A.M. A Novel Homozygous Selenocysteine Insertion Sequence Binding Protein 2 (SECISBP2, SBP2) Gene Mutation in a Turkish Boy. Thyroid. 2018;28:1221–1223. doi: 10.1089/thy.2018.0015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Korwutthikulrangsri M., Raimondi C., Dumitrescu A.M. Novel Compound Heterozygous SBP2 Gene Mutations in a Boy with Developmental Delay and Failure to Thrive. 13th IWRTH; Doorn, The Netherlands: 2018. p. 22. Abstract Book. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fu J., Korwutthikulrangsri M., Gönç E.N., Sillers L., Liao X.H., Alikaşifoğlu A., Kandemir N., Menucci M.B., Burman K.D., Weiss R.E., et al. Clinical and Molecular Analysis in 2 Families With Novel Compound Heterozygous SBP2 (SECISBP2) Mutations. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020;105:e6–e11. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgz169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bubenik J.L., Driscoll D.M. Altered RNA binding activity underlies abnormal thyroid hormone metabolism linked to a mutation in selenocysteine insertion sequence-binding protein 2. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:34653–34662. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707059200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao W., Bohleber S., Schmidt H., Seeher S., Howard M.T., Braun D., Arndt S., Reuter U., Wende H., Birchmeier C., et al. Ribosome profiling of selenoproteins in vivo reveals consequences of pathogenic Secisbp2 missense mutations. J. Biol. Chem. 2019;294:14185–14200. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA119.009369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ng L., Goodyear R.J., Woods C.A., Schneider M.J., Diamond E., Richardson G.P., Kelley M.W., Germain D.L., Galton V.A., Forrest D. Hearing loss and retarded cochlear development in mice lacking type 2 iodothyronine deiodinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:3474–3479. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307402101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hernandez A., Martinez M.E., Fiering S., Galton V.A., St Germain D. Type 3 deiodinase is critical for the maturation and function of the thyroid axis. J. Clin. Invest. 2006;116:476–484. doi: 10.1172/JCI26240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Downey C.M., Horton C.R., Carlson B.A., Parsons T.E., Hatfield D.L., Hallgrímsson B., Jirik F.R. Osteo-chondroprogenitor-specific deletion of the selenocysteine tRNA gene, Trsp, leads to chondronecrosis and abnormal skeletal development: A putative model for Kashin-Beck disease. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000616. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Silwal A., Sarkozy A., Scoto M., Ridout D., Schmidt A., Laverty A., Henriques M., D’Argenzio L., Main M., Mein R., et al. Selenoprotein N-related myopathy: A retrospective natural history study to guide clinical trials. Ann. Clin. Transl. neurol. 2020;7:2288–2296. doi: 10.1002/acn3.51218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McFadden S.L., Ohlemiller K.K., Ding D., Shero M., Salvi R.J. The Influence of Superoxide Dismutase and Glutathione Peroxidase Deficiencies on Noise-Induced Hearing Loss in Mice. Noise health. 2001;3:49–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Riva C., Donadieu E., Magnan J., Lavieille J.P. Age-related hearing loss in CD/1 mice is associated to ROS formation and HIF target proteins up-regulation in the cochlea. Exp. Geront. 2007;42:327–336. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2006.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ursini F., Heim S., Kiess M., Maiorino M., Roveri A., Wissing J., Flohé L. Dual function of the selenoprotein PHGPx during sperm maturation. Science. 1999;285:1393–1396. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5432.1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Foresta C., Flohé L., Garolla A., Roveri A., Ursini F., Maiorino M. Male fertility is linked to the selenoprotein phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase. Biol. reprod. 2002;67:967–971. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.102.003822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kryukov G.V., Castellano S., Novoselov S.V., Lobanov A.V., Zehtab O., Guigó R., Gladyshev V.N. Characterization of mammalian selenoproteomes. Science. 2003;300:1439–1443. doi: 10.1126/science.1083516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Su D., Novoselov S.V., Sun Q.A., Moustafa M.E., Zhou Y., Oko R., Hatfield D.L., Gladyshev V.N. Mammalian selenoprotein thioredoxin-glutathione reductase. Roles in disulfide bond formation and sperm maturation. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:26491–26498. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503638200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schneider M., Förster H., Boersma A., Seiler A., Wehnes H., Sinowatz F., Neumüller C., Deutsch M.J., Walch A., Hrabé de Angelis M., et al. Mitochondrial glutathione peroxidase 4 disruption causes male infertility. FASEB J. 2009;23:3233–3242. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-132795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schweikert K., Gafner F., Dell’Acqua G. A bioactive complex to protect proteins from UV-induced oxidation in human epidermis. Int. J. Cosm. Sci. 2010;32:29–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2494.2009.00528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sengupta A., Lichti U.F., Carlson B.A., Ryscavage A.O., Gladyshev V.N., Yuspa S.H., Hatfield D.L. Selenoproteins are essential for proper keratinocyte function and skin development. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e12249. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Verma S., Hoffmann F.W., Kumar M., Huang Z., Roe K., Nguyen-Wu E., Hashimoto A.S., Hoffmann P.R. Selenoprotein K knockout mice exhibit deficient calcium flux in immune cells and impaired immune responses. J. Immunol. 2011;186:2127–2137. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saito Y., Shichiri M., Hamajima T., Ishida N., Mita Y., Nakao S., Hagihara Y., Yoshida Y., Takahashi K., Niki E., et al. Enhancement of lipid peroxidation and its amelioration by vitamin E in a subject with mutations in the SBP2 gene. Lipid Res. 2015;56:2172–2182. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M059105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liao C., Carlson B.A., Paulson R.F., Prabhu K.S. The intricate role of selenium and selenoproteins in erythropoiesis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2018;127:165–171. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.04.578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schomburg L., Dumitrescu A.M., Liao X.H., Bin-Abbas B., Hoeflich J., Köhrle J., Refetoff S. Selenium supplementation fails to correct the selenoprotein synthesis defect in subjects with SBP2 gene mutations. Thyroid. 2009;19:277–281. doi: 10.1089/thy.2008.0397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shetty S.P., Copeland P.R. Selenocysteine incorporation: A trump card in the game of mRNA decay. Biochimie. 2015;114:97–101. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2015.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carlson B.A., Yoo M.H., Tsuji P.A., Gladyshev V.N., Hatfield D.L. Mouse models targeting selenocysteine tRNA expression for elucidating the role of selenoproteins in health and development. Molecules. 2009;14:3509–3527. doi: 10.3390/molecules14093509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schoenmakers E., Carlson B., Agostini M., Moran C., Rajanayagam O., Bochukova E., Tobe R., Peat R., Gevers E., Muntoni F., et al. Mutation in human selenocysteine transfer RNA selectively disrupts selenoprotein synthesis. J. Clin. Invest. 2016;126:992–996. doi: 10.1172/JCI84747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Geslot A., Savagner F., Caron P. Inherited selenocysteine transfer RNA mutation: Clinical and hormonal evaluation of 2 patients. Eur. Thyroid, J. 2021;10:542–547. doi: 10.1159/000518275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hatfield D., Lee B.J., Hampton L., Diamond A.M. Selenium induces changes in the selenocysteine tRNA[Ser]Sec population in mammalian cells. Nucleic acids res. 1991;19:939–943. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.4.939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Diamond A.M., Choi I.S., Crain P.F., Hashizume T., Pomerantz S.C., Cruz R., Steer C.J., Hill K.E., Burk R.F., McCloskey J.A., et al. Dietary selenium affects methylation of the wobble nucleoside in the anticodon of selenocysteine tRNA([Ser]Sec) J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:14215–14223. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)85229-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kernebeck T., Lohse A.W., Grötzinger J. A bioinformatical approach suggests the function of the autoimmune hepatitis target antigen soluble liver antigen/liver pancreas. Hepatology. 2001;34:230–233. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.26632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Small-Howard A., Morozova N., Stoytcheva Z., Forry E.P., Mansell J.B., Harney J.W., Carlson B.A., Xu X.M., Hatfield D.L., Berry M.J. Supramolecular complexes mediate selenocysteine incorporation in vivo. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006;26:2337–2346. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.6.2337-2346.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xu X.M., Mix H., Carlson B.A., Grabowski P.J., Gladyshev V.N., Berry M.J., Hatfield D.L. Evidence for direct roles of two additional factors, SECp43 and soluble liver antigen, in the selenoprotein synthesis machinery. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:41568–41575. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506696200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Araiso Y., Palioura S., Ishitani R., Sherrer R.L., O’Donoghue P., Yuan J., Oshikane H., Domae N., Defranco J., Söll D., et al. Structural insights into RNA-dependent eukaryal and archaeal selenocysteine formation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:1187–1199. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ganichkin O.M., Xu X.M., Carlson B.A., Mix H., Hatfield D.L., Gladyshev V.N., Wahl M.C. Structure and catalytic mechanism of eukaryotic selenocysteine synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:5849–5865. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709342200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Palioura S., Sherrer R.L., Steitz T.A., Söll D., Simonovic M. The human SepSecS-tRNASec complex reveals the mechanism of selenocysteine formation. Science. 2009;325:321–325. doi: 10.1126/science.1173755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Puppala A.K., French R.L., Matthies D., Baxa U., Subramaniam S., Simonović M. Structural basis for early-onset neurological disorders caused by mutations in human selenocysteine synthase. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:32563. doi: 10.1038/srep32563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Agamy O., Ben Zeev B., Lev D., Marcus B., Fine D., Su D., Narkis G., Ofir R., Hoffmann C., Leshinsky-Silver E., et al. Mutations disrupting selenocysteine formation cause progressive cerebello-cerebral atrophy. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2010;87:538–544. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Makrythanasis P., Nelis M., Santoni F.A., Guipponi M., Vannier A., Béna F., Gimelli S., Stathaki E., Temtamy S., Mégarbané A., et al. Diagnostic exome sequencing to elucidate the genetic basis of likely recessive disorders in consanguineous families. Hum. Mutat. 2014;35:1203–1210. doi: 10.1002/humu.22617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Anttonen A.K., Hilander T., Linnankivi T., Isohanni P., French R.L., Liu Y., Simonović M., Söll D., Somer M., Muth-Pawlak D., et al. Selenoprotein biosynthesis defect causes progressive encephalopathy with elevated lactate. Neurology. 2015;85:306–315. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhu X., Petrovski S., Xie P., Ruzzo E.K., Lu Y.F., McSweeney K.M., Ben-Zeev B., Nissenkorn A., Anikster Y., Oz-Levi D., et al. Whole-exome sequencing in undiagnosed genetic diseases: Interpreting 119 trios. Genet. Med. 2015;17:774–781. doi: 10.1038/gim.2014.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Alazami A.M., Patel N., Shamseldin H.E., Anazi S., Al-Dosari M.S., Alzahrani F., Hijazi H., Alshammari M., Aldahmesh M.A., Salih M.A., et al. Accelerating novel candidate gene discovery in neurogenetic disorders via whole-exome sequencing of prescreened multiplex consanguineous families. Cell Rep. 2015;10:148–161. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pavlidou E., Salpietro V., Phadke R., Hargreaves I.P., Batten L., McElreavy K., Pitt M., Mankad K., Wilson C., Cutrupi M.C., et al. Pontocerebellar hypoplasia type 2D and optic nerve atrophy further expand the spectrum associated with selenoprotein biosynthesis deficiency. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 2016;20:483–488. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2015.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Iwama K., Sasaki M., Hirabayashi S., Ohba C., Iwabuchi E., Miyatake S., Nakashima M., Miyake N., Ito S., Saitsu H., et al. Milder progressive cerebellar atrophy caused by biallelic SEPSECS mutations. J. Hum. Genet. 2016;61:527–531. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2016.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Olson H.E., Kelly M., LaCoursiere C.M., Pinsky R., Tambunan D., Shain C., Ramgopal S., Takeoka M., Libenson M.H., Julich K., et al. Genetics and genotype-phenotype correlations in early onset epileptic encephalopathy with burst suppression. Ann. Neurol. 2017;81:419–429. doi: 10.1002/ana.24883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Van Dijk T., Vermeij J.D., van Koningsbruggen S., Lakeman P., Baas F., Poll-The B.T. A SEPSECS mutation in a 23-year-old woman with microcephaly and progressive cerebellar ataxia. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2018;41:897–898. doi: 10.1007/s10545-018-0151-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Arrudi-Moreno M., Fernández-Gómez A., Peña-Segura J.L. A new mutation in the SEPSECS gene related to pontocerebellar hypoplasia type 2D. Med. Clin. 2021;156:94–95. doi: 10.1016/j.medcli.2019.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nejabat M., Inaloo S., Sheshdeh A.T., Bahramjahan S., Sarvestani F.M., Katibeh P., Nemati H., Tabei S., Faghihi M.A. Genetic Testing in Various Neurodevelopmental Disorders Which Manifest as Cerebral Palsy: A Case Study From Iran. Frontiers in Pediatrics. 2021;9:734946. doi: 10.3389/fped.2021.734946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ben-Zeev B., Hoffman C., Lev D., Watemberg N., Malinger G., Brand N., Lerman-Sagie T. Progressive cerebellocerebral atrophy: A new syndrome with microcephaly, mental retardation, and spastic quadriplegia. J. Med. Genet. 2003;40:e96. doi: 10.1136/jmg.40.8.e96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fradejas-Villar N., Zhao W., Reuter U., Doengi M., Ingold I., Bohleber S., Conrad M., Schweizer U. Missense mutation in selenocysteine synthase causes cardio-respiratory failure and perinatal death in mice which can be compensated by selenium-independent GPX4. Redox Biol. 2021;48:102188. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2021.102188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.