Abstract

Cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) is a universal second messenger that plays a crucial role in diverse biological functions, ranging from transcription to neuronal plasticity, and from development to learning and memory. In the nervous system, cAMP integrates inputs from many neuromodulators across a wide range of timescales — from seconds to hours — to modulate neuronal excitability and plasticity in brain circuits during different animal behavioral states. cAMP signaling events are both cell-specific and subcellularly compartmentalized. The same stimulus may result in different, sometimes opposite, cAMP dynamics in different cells or subcellular compartments. Additionally, the activity of protein kinase A (PKA), a major cAMP effector, is also spatiotemporally regulated. For these reasons, many laboratories have made great strides toward visualizing the intracellular dynamics of cAMP and PKA. To date, more than 80 genetically encoded sensors, including original and improved variants, have been published. It is starting to become possible to visualize cAMP and PKA signaling events in vivo, which is required to study behaviorally relevant cAMP/PKA signaling mechanisms. Despite significant progress, further developments are needed to enhance the signal-to-noise ratio and practical utility of these sensors. This review summarizes the recent advances and challenges in genetically encoded cAMP and PKA sensors with an emphasis on in vivo imaging in the brain during behavior.

Keywords: Genetically encoded cAMP sensors, protein kinase A (PKA) sensors, Epac-based cAMP sensor, in vivo imaging, neuromodulation, subcellular signaling

Introduction

Cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) is a universal second messenger found in nearly every organism, from prokaryotes to humans (Berman et al., 2005). In mammals, cAMP regulates a plethora of molecular processes including transcription, translation, metabolism, and protein trafficking (Daniel et al., 1998; Dunn and Feller, 2008). At the cellular level within neurons, cAMP regulates development, synaptic transmission, and plasticity (Fernandes et al., 2015; Gelinas et al., 2008; Inan et al., 2006; Iwasato et al., 2008; Lee et al., 2015). At the organismic levels, cAMP regulates learning, memory, and social behaviors (Bourtchouladze et al., 2006; Silva and Murphy, 1999; Srivastava et al., 2012; Yang et al., 2012), and is associated with a range of neurodevelopmental and psychiatric disorders (Kelley et al., 2008; Nestler et al., 2002). Components of the cAMP pathway, such as adenylyl cyclases and phosphodiesterases, which synthesize and degrade cAMP, respectively (Conti and Beavo, 2007; Hanoune and Defer, 2001), are important targets for therapeutic drug development (Baillie et al., 2019; Pierre et al., 2009; Raker et al., 2016).

In the brain, different biological states, such as arousal, reward, stress, and locomotion, are associated with the releases of different neuromodulators that dynamically repurpose the brain circuit (Greengard, 2001). Nearly every major neuromodulator converges onto the cAMP pathway through its respective G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) (Beavo and Brunton, 2002; Greengard, 2001). Three out of the four major classes of G proteins converge onto the cAMP pathway with differential effects. Gs interacts with and activates adenylyl cyclases, Gi inhibits adenylyl cyclases, and Gq increases cAMP concentrations indirectly via parallel PKC- and calcium-dependent pathways (Chen et al., 2017; Hanoune and Defer, 2001). Downstream, cAMP functions through four classes of effectors: the cAMP-dependent kinase (i.e., protein kinase A, or PKA), exchange proteins activated by cAMP (Epac), cAMP gated or regulated channels, and Popeye domain containing (POPDC) proteins (Biel, 2009; Bos, 2003; De Rooij et al., 1998; Kawasaki et al., 1998; Schindler and Brand, 2016). These effectors in turn regulate a myriad of downstream targets to control diverse cellular functions. Among these effectors, PKA is the first described cAMP effector, and it mediates the majority of cAMP functions studied to date (Francis and Corbin, 1994; Johnson et al., 2001).

To achieve specificity despite the upstream convergence and downstream divergence, cAMP signaling is tightly controlled both spatially and temporally. The same neuromodulator can cause cell type-specific regulation of cAMP governed by different receptor subtypes. A well-documented example occurs in the striatum, where dopamine increases intracellular cAMP concentrations in Gs-coupled D1 dopamine receptor-expressing striatal projection neurons (D1-SPNs); in contrast, dopamine suppresses cAMP in D2 dopamine receptor-expressing SPNs (D2-SPNs) via the G, protein (Surmeier et al., 2007; Tritsch and Sabatini, 2012). Within an individual cell, cAMP dynamics and signaling are compartmentalized (Buxton and Brunton, 1983; Scott and Pawson, 2009; Zhang et al., 2021b), such that the exact cAMP concentrations and dynamics are different across different subcellular compartments. PKA is also spatially regulated across subcellular compartments via its anchoring proteins (Wong and Scott, 2004; Zhang et al., 2021b). Therefore, an in-depth understanding of the mechanisms associated with cAMP and PKA signaling requires imaging of their activities with sufficiently high spatiotemporal resolution. When combined with appropriate pharmacology, cAMP/PKA imaging may also be used to monitor upstream neuromodulator activities (Labouesse and Patriarchi, 2021; Sabatini and Tian, 2020), analogous to the use of calcium imaging as a readout for neuronal electrical activity. Because animal behavioral states are difficult to recapitulate in vitro, such imaging is ideally carried out in vivo. Within this review, “in vivo” is defined as in living animals.

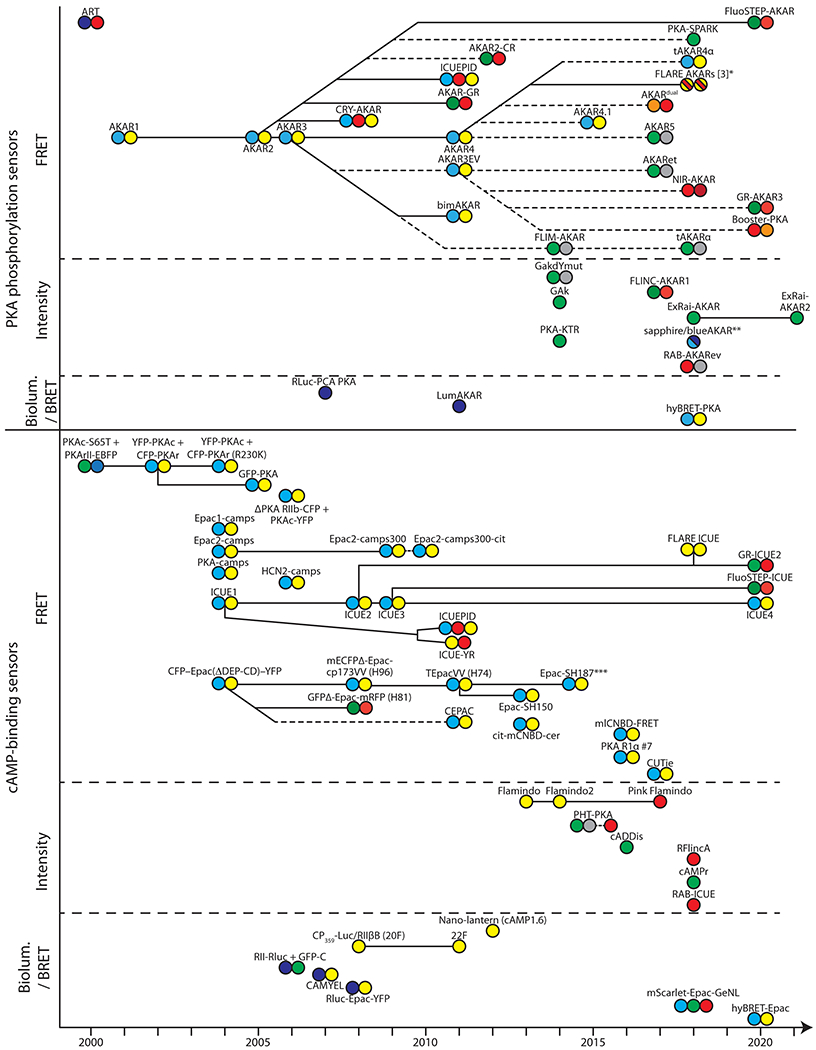

Imaging cAMP and PKA requires two intertwined components: the sensor and the appropriate measurement modality. Most cAMP/PKA sensors are genetically encoded because of the ease of delivery, the advantage of being able to target genetically-defined cell types, and the compatibility with longitudinal imaging. To date, more than 80 different sensors for cAMP or PKA have been developed (Figure 1). The majority are fluorescent sensors, using either Forster resonance energy transfer (FRET; Tsien et al., 1993; Yasuda, 2006) or the environmental sensitivity of circularly-permutated fluorescent proteins (cp-FPs) (Barnett et al., 2017; Nakai et al., 2001) to generate imaging signals. Sensors utilizing other mechanisms, including dimerization-dependent FPs (Alford et al., 2012b, 2012a), FP translocations, and bioluminescence-based readouts (Lohse et al., 2012; Yeh and Ai, 2019) have also been generated. Understanding and choosing these sensors can be a daunting task for many researchers. Below, we summarize the sensors developed to date based on the chronological order of the prototype sensor of each class, and discuss the primary approaches used to image these sensors. We further discuss our views on the sensor properties important for both end users and developers, as well as the recent applications of these sensors in the brain in vivo.

Figure 1. Historical view of genetically encoded cAMP and PKA biosensors.

The diagram represents the development and family lineage (solid and dashed lines, for developments by the same and independent groups, respectively) of cAMP binding and PKA phosphorylation sensors, as indicated. Sensor groups are further divided based on the mechanism for signal generation (i.e., FRET, intensity, BRET, or bioluminescence). The FP(s) of each sensor are illustrated using colored circles representative of their qualitative emission color(s). FP variants with similar emissions (e.g., mCherry and mApple) are colored the same, and dark, “non-irradiating” FPs are represented by gray circles. Further specifications for FPs, sensor constructions, and performances are detailed in Tables 1 and 2. Unless noted, targeted variants of a specific sensor are not included. *Several color variants exist. The color combinations of three best performing FPs are shown as dashed colors within a single circle. **Two different color variants (shown as dashed colors) of the same design. ***Representative of a series of similar constructs varied by FPs. See Glossary for abbreviations and acronyms.

Due to the large number of abbreviations and acronyms, we will not spell them out in the text. Instead, please refer to the attached Acronyms and Abbreviations.

Optical cAMP sensors and their brief history

Sensors based on the dissociation of the PKA catalytic and regulatory subunits

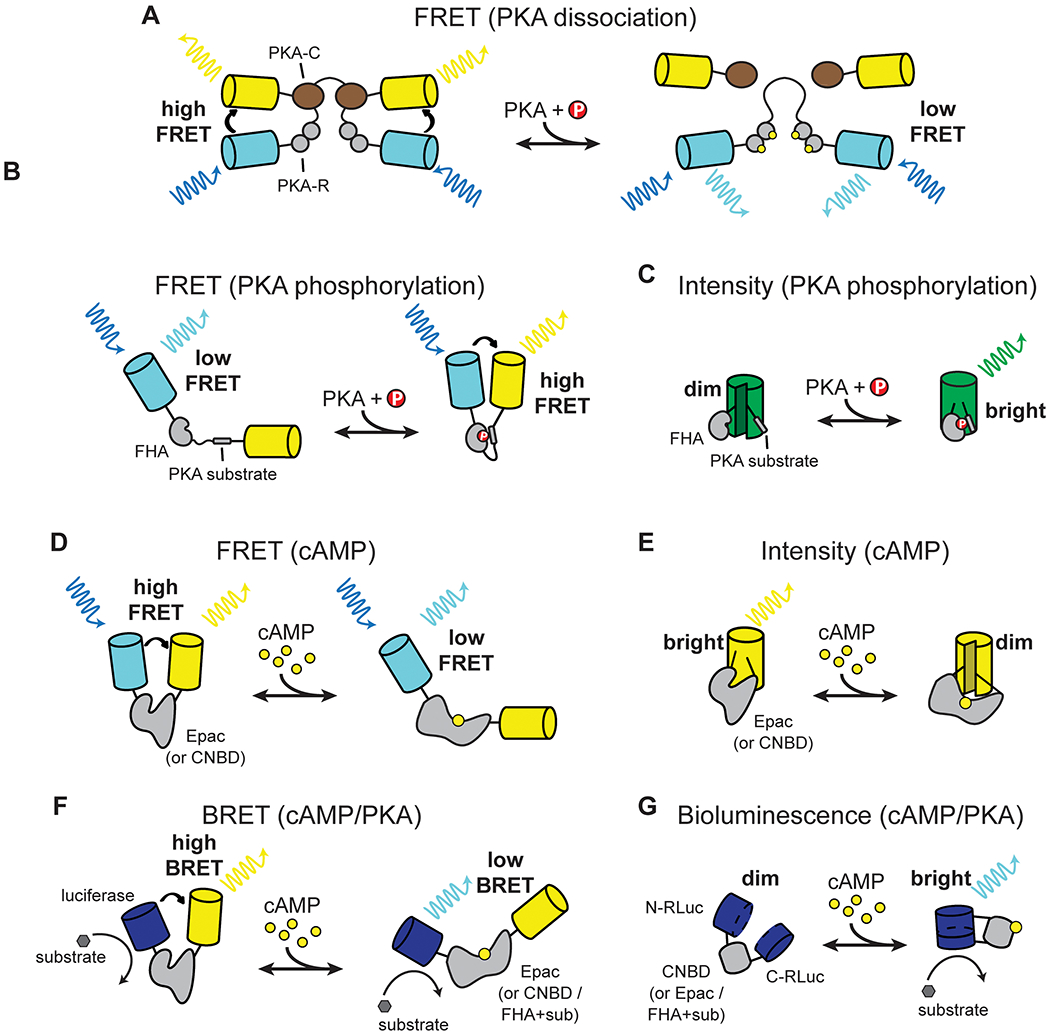

The first cAMP sensor for live cell imaging – although not genetically encoded – was developed in 1991, which to our knowledge was also the first FRET reporter (Adams et al., 1991). FRET is an energy-transferring interaction between a donor fluorophore and an acceptor fluorophore (Figure 2A; for reviews of FRET, see Piston and Kremers, 2007; Tsien et al., 1993; Yasuda, 2006). FRET efficiency is sensitive to the distance (<10 nm) and angle between the fluorophores, and can thereby be used to report changes in protein-protein interaction or protein conformation. This sensor, called FlCRhR, utilizes the fact that the catalytic and regulatory subunits of the PKA holoenzyme (PKA-C and PKA-R, respectively) dissociate from each other in the presence of cAMP (Francis and Corbin, 1994; Taylor et al., 1990). Recombinant PKA-C and PKA-R were tagged with the organic dyes fluorescein and rhodamine, respectively, and were microinjected into living cells (Adams et al., 1991). Increased cAMP concentrations resulted in decreased FRET. The first genetically encoded cAMP sensor was also based on a similar mechanism, except that genetically encoded FPs (specifically, EBFP and EGFP) were used (Figures 1 and 2A, and Table 1) (Zaccolo et al., 2000). The FP pair was later switched to ECFP and EYFP for increased brightness and FRET efficiency, and the linker was optimized (Lissandron et al., 2005; Mongillo et al., 2004; Zaccolo and Pozzan, 2002).

Figure 2. Schematic mechanisms of cAMP and PKA sensors in each category.

Please note that the sizes between different components within a sensor are not proportional. There may also be sensors within each category that are of different colors or that exhibit opposite directions of responses.

Table 1. cAMP sensors and their properties.

Some numbers are estimated from figures and are preceded by “~”. Abbreviations: Aden.: adenosine; DR: dynamic range; F: forskolin; I: IBMX; Iso: isoproterenol; CMs: cardiomyocytes; 293 and 293T: HEK 293 and HEK 293T cells, respectively; l-vLNs: large ventrolateral neurons; LT: fluorescence lifetime; stria.: striatal; Rol.: rolipram; MBs: mushroom bodies.

| Name | Publication | Mode | Corr. Authors | Sensing mechanism | FPs | DR % (Cell, agonist)1 | Kd (μM)2 cAMP / cGMP | Other uses (DR % / Kd [μM])1 | In neuron /in vivo1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PKAc-S65T + PKArII-EBFP | Zaccolo et al., 2000 | FRET | Pozzan | PKARII-PKAc | GFP(S65T)-EBFP | ~50% (CHO, F+dbcAMP) | - / - | - | - |

| YFP-PKAc + CFP-PKAr | Zaccolo & Pozzan, 2002 | FRET | Zaccolo | RII+CII | CFP-YFP | 17% (CMs, F+I) | - / - | ~11% (CMs, IBMX) / ~0.3 μM, cAMP )3 | ~10 (dissoc. ret. neuron, F+I)4,5 |

| CFP-Epac(ΔDEP-CD)-YFP | Ponsioen et al., 2004 | FRET | Bos & Jalink | Epac1 (ΔDEP-CD) | CFP-YFP | ~45% (A431, F) | 14 / - | - | - |

| Epac1-camps13 | Nikolaev et al., 2004 | FRET | Lohse | CNBD (Epac1) | CFP-YFP | 24% (HEK-β1R, Iso) | 2.35 / - | ~32% (CHO, F+I)6 | ~37%7, ~4%8 or ~5%9 (cultured neurons, Iso, Iso+Rol, or F); ~10% (cultured slices, F+I)10; ~35%11 - ~40%12 (fly l-vLNs, F) |

| Epac2-camps13 | Nikolaev et al., 2004 | FRET | Lohse | CNBD-B (Epac2) | CFP-YFP | 17% (HEK-β1R, Iso); 35% (CHOA2B, Aden.) | 0.92 / 10.6 | 0.82 μM (protein, cAMP)14 | - |

| PKA-camps | Nikolaev et al., 2004 | FRET | Lohse | CNBD-B (PKA-RIIβ) | CFP-YFP | 15% (HEK-β1R, Iso) | 1.88 / - | - | - |

| ICUE1 | DiPilato et al., 2004 | FRET | Zhang | Epac1 | ECFP-Citrine | 19.6% (293, F) | - / - | - | - |

| YFP-PKAc + CFP-PKAr(R230K) | Mongillo et al., 2004 | FRET | Zaccolo | RII+CII | CFP-YFP | ~9% (CMs, I) | 31.3 / - | - | - |

| GFP-PKA | Lissandron et al., 2005 | FRET | Zaccolo | RII+CII | CFP-YFP | ~18% or 12% (ΔLT/LT0), (CHO, F+I) | - | - | ~6% (in vivo fly MBs, F+I)15 |

| PKA-ΔRIIb-CFP + PKA-Cα-YFP | Dyachok et al., 2006 | FRET | Tengholm | ΔRIIb + Cα | CFP-YFP | 200% (INS-1 β-cell, glucose+GLP-1) | - / - | - | - |

| HCN2-camps13 | Nikolaev et al., 2006 | FRET | Lohse & Engelhardt | CNBD (HCN2) | CFP-YFP | ~20% (CMs, I)(transgenic mouse) | 5.9 / - | - | - |

| R2-Rluc + GFP-C | Prinz et al., 2006 | BRET | Prinz | RIIa + Cα | GFP-RLuc | ~90%(COS-7, F+I) | 1 (Rp-8-Br-cAMP) / - | - | - |

| CAMYEL | Jiang et al., 2007 | BRET | Jiang & Sternweis | Epac1 (ΔDEP-CD) | Citrinecp229-RLuc | ~60% (RAW-264.7, 8-Br cAMP) | 8.8 / - | - | - |

| GFPΔ-Epac-mRFP (H81) | van der Krogt et al., 2008 | FRET | Jalink | Epac1 (ΔDEP-CD) | GFPΔ-mRFP | 29%4 (293, F+I) | - / - | - | - |

| mECFPΔ-Epac-cp173VV (H96) | van der Krogt et al., 2008 | FRET | Jalink | Epac1 (ΔDEP-CD) | CFP-cp173mVenus | 36%4 (293, F+I) | - / - | 56%4 (293, F+I)16 | - |

| ICUE2 | Violin et al., 2008 | FRET | Elston, Zhang, & Lefkowitz | Epac1 (148-881) | ECFP-Citrine | 61% (293, F) | 12.5 / - | - | ~35% (Dissoc. ret. neuron, F+I)4,5 |

| Rluc-EPAC-YFP | Barak et al.,2008 | BRET | Caron | Epac1 (149-881) | RLuc-Citrine | ~11% (293, β-PEA+I) | - / - | - | - |

| CP359-Luc/RIIbB (20F) | Fan et al., 2008 | Biolum. | Wood | RIIβ-B | Cp359-Luc | ~2500% (293, F) | 0.5 / ~100- | 70x / 0.3 (protein, cAMP) 20x (293, F+I)17 | - |

| Epac2-camps300 | Norris et al., 2009 | FRET | Nikolaev & Jaffe | CNBD-B (Epac2) | CFP-YFP | ~32% (mouse oocytes, cAMP) | 0.32 / 14 | - | ~5% (cultured neurons, F)9; ~10% (cultured slices, F+I)18 |

| ICUE3 | DiPilato & Zhang, 2009 | FRET | Zhang | Epac1 (148-881) | ECFP-cpVenus | 102% (293, F) | - / - | 75.1% (293T, F+I)19; ~;60% (293T, F)20,21 | - |

| Epac2-camps300-cit | Castro et al., 2010 | FRET | Vincent | CNBD-B (Epac2) | CFP-Citrine | - | - / - | - | ~12% (cultured slices, F+I)18 |

| 22F | Binkowski et al., 2011 | Biolum. | Binkowski | RIIβ-B | cp359-Luc | ~80000% (293, F+I) | 9 / - | - | - |

| CEPAC | Salonikidis et al., 2011 | FRET | Salonikidis | Epac1 (ΔDEP-CD) | mCerulean-mCitrine | ~15% (N1E, F) | 23.6 / - | - | - |

| TEpacvv (H74)13 | Klarenbeek et al., 2011 | FRET | Jalink | Epac1 (ΔDEP-CD) | mTurquoiseΔ-cp173Venus-Venus | 82.2% or 30% (ΔLT/LT0) (293, F+I) | - / - | - | ~50%/3 μM (cultured stria. neurons)22 |

| ICUE-YR | Ni et al., 2011 | FRET | Levchenko & Zhang | Epac1 (148-881) | RFP-YFP | ~50% (293, F) | - / - | - | - |

| ICUEPID | Ni et al., 2011 | FRET | Levchenko & Zhang | FHA1-PKA Sub& Epac1 (148-881) | CFP-RFP-YFP | ~25% (293, F)25 | - / - | - | - |

| Nano-lantern cAMP1.6 | Saito et al., 2012 | Biolum. | Tsuda & Umetsu | Epac1 (170-327) | VenusΔC10-RLuc8(split) | ~130% (D. discoideum cells, cAMP) | 1.6 / - | - | - |

| cit-mCNBD-cer | Krähling et al., 2013 | FRET | Wachten | CNBD (mCRIS) | mCerulean-mCitrine | ~5% (CHO, 8-Br-cAMP) | - / - | - | - |

| Flamindo | Kitaguchi et al., 2013 | Intensity | Kitaguchi & Miyawaki | Epac1 (157-316) | Citrine | 55% (COS7, 8-Br-cAMP) | 3.6 / 29.9 | 2.1/22 (cAMP/GMP)24 | - |

| Epac-SH150 | Polito et al., 2013 | FRET | Castro | Epac1 (ΔDEP-CD) | mTurquoise2-cp174Cirtine | - | - | - | ~60% (cultured MSNs, F+I); ~60% (cultured MSNs, F+I)25; 0.68/0.39 (D1/D2 cultured MSNs), NPEC-DA)25 |

| Flamindo2 | Odaka et al., 2014 | Intensity | Kitaguchi | Epac1 (199-358) | Citrine | 70% (COS7, F) | 3.2 / 22 | ~60% (HeLa, F+I)26; 3.2 μM (protein, cAMP)10 | ~55% (in vivo, mouse astrocytes, F+I)27 |

| Epac-SH187 (see footnote 28) | Klarenbeek et al., 2015 | FRET | Jalink | Epac1 (ΔDEP-CD) | mTurquoise2Δtdcp173Ven | ~164% or 62% (ΔLT/LT0) (293T, F+I) | - / - | - | - |

| PHT-PKA | Ding et al., 2015 | Ratio | Campbell | PKAc-PKAr | ddRFP-ddGFP | ~200% (HeLa, Iso) | - / - | - | - |

| cADDis-green | Tewson et al., 2016 | Intensity | Quinn | Epac2 | GFP | ~35% (293T, ?) | ~50 / - | ~60% (293T, F)29 ~60% (ES, F)11 | - |

| mICNBD-FRET13 | Mukherjee, et al., 2016 | FRET | Kaupp& Wachten | CNBD (MlotiK1) | Citrine-Cerulean | 47%(293, NKH477+IBMX) | 0.035-0.10330 / ~504 | - | - |

| RIalpha #7 | Ohta et al., 2016 | FRET | Horikawa | RIα, CNB-B (245-381) | cp173Venus-ECFP | 38% (purified protein, cAMP) | 0.0372 / - | - | - |

| CUTie | Surdo et al., 2017 | FRET | Zaccolo | RIIα, CNB-B | CFP-YFP | 23% (CHO, F+I) | 7.431(CHO ) / - | - | - |

| Pink Flamindo32 | Harada et al., 2017 | Intensity | Tsuboi & Kitaguchi | Epac1 CNBD (205-353) | mApple | ~125% (HeLa, F+I) | 7.2 / 94 | ~250% (293T, F)34 | ~55%,(astrocytes, F+I)27; —80% (in vivo, mouse ctx astrocytes, DREADD)34 |

| mScarlet-Epac-GeNL | French et al., 2018 | FRET/BRET | Tantama | Epac1 (148-881) | mScarlet-GeNL | 80%/80% (purified protein, cAMP); ~44%/~29% (293, F) (FRET/BRET) | 2.5 (FRET) / -; 19.8 (BRET) / - | - | - |

| RAB-ICUE | Mehta et al., 2018 | Intensity | Mehta, Huganir & Zhang, | Epac1 (149-881) | ddRFP-ddRFP | 20.6% (293T, F+I) | - / - | - | - |

| R-FlincA37 | Ohta et al., 2018 | Intensity | Horikawa | RIα CNBDs (93-381) | cp146mApple | ~600% (293T, F); ~850% (cAMP)2 | 0.3 / - | - | - |

| cAMPr | Hackley et al., 2018 | Intensity | Blau | PKAc-PKAr (CNB-A,91-244) | cpGFP | ~55% (ES, F) | - / - | - | ~40/100% (soma/axons, fly brain, carbachol)11 |

| FLARE ICUE | Ross et al., 2018 | FRET | Rizzo & Zhang | Epac1 | Venus-cp172Venus | ~1.5% (293T,F+I) | - / - | - | - |

| hyBRET-Epac | Watabe et al., 2020 | FRET/ BRET | Terai | Epac1 | mTurquoise-GL-YPet | - | ~10 (F) or ~0.1 (Iso) (HeLa) | - | - |

| GR-ICUE2 | Mo et al., 2020 | FRET | Zhang | Epac1 (148-881) | EGFP-stagRFP | 60.5% (293T, F+I) | - / - | - | - |

| FluoSTEP-ICUE | Zhang et al., 2020 | FRET | Zhang | Epac1 (149-881) | GFP1-10-mRuby2 | 8.4% (293-RIα, F) | - | - | - |

| ICUE4 | Zhang et al., 2020 | FRET | Zhang | Epac1 (149-881) | ECFP-cpVenus | ~80% (293T, F) | ~5 (F, 293T) | - | - |

For DR, ΔF/F0 for intensity sensors, ΔR/R0 for FRET sensors, and ΔLum/Lum0 for bioluminescence sensors, unless noted otherwise.

Purified protein, unless noted otherwise.

ΔR (baseline not available)

(Calebiro et al., 2009); Cells isolated from mouse line. Only neuronal data shown here.

Sensor has been made into a transgenic mouse line

Ratio of YFP/RFP

Part of a larger series of reporters. See (Klarenbeek et al., 2015).

(Tewson et al., 2018); H293T cells expressing D2 or M2 receptor

Purified protein - digitonin permeabilized 293 cells

Loaded into cell via patch pipette

Needs to grow at 32°C for maximal brightness

Needs to grow at 32°C

Two variants of this class of sensors that used non-FRET mechanisms were also developed (Ding et al., 2015; Dyachok et al., 2006). The first variant uses membrane-anchored PKA-R-CFP and non-anchored PKA-C-YFP. Binding of cAMP leads to the dissociation of the PKA-C/PKA-R complex and loss of PKA-C-YFP from the membrane, which can be imaged using TIRF microscopy (Steyer and Almers, 2001). The second variant utilizes dimerization-dependent FPs (Alford et al., 2012b, 2012a). A non-fluorescent dimerization donor FP fused to PKA-R enhances the brightness of a dimerization-dependent RFP fused to PKA-C at rest (Ding et al., 2015). cAMP dissociates PKA-C and PKA-R, resulting in decreased RFP fluorescence. The donor FP then complement another dimerization-dependent GFP to increase its fluorescence. Elevated cAMP levels therefore increase the green-to-red ratio.

The advantage of this class of sensors is that the dissociation of PKA-C and PKA-R represents an extreme case of conformational change, making it relatively easy to achieve large FRET signals without needing extensive optimization when compared to single polypeptide FRET sensors. They naturally detect cAMP at concentrations relevant to PKA function. However, functional PKA is overexpressed, which may result in side effects, especially for in vivo applications that require prolonged expression. The overexpressed sensor subunits may also bind to endogenous PKA subunits, which are thought to be expressed at micromolar concentrations (Francis and Corbin, 1994), reducing the possible signal. It is also challenging to achieve consistent or stoichiometric co-expression of multiple proteins, especially in vivo. In addition, local concentration differences between PKA-C and PKA-R can occur. For example, in neurons, PKA-R is excluded from dendritic spines, whereas PKA-C can enter dendritic spines when it is activated and liberated from PKA-R (Tillo et al., 2017; Zhong et al., 2009). Even if activated PKA-C-ECFP is evenly distributed between dendrites and spines (i.e., uniform activity), the apparent activity measurement will be different between these neuronal subcellular locations because PKA-R-EYFP is not present in spines.

Multi-fluorophore PKA activity sensors

A second class of sensors was designed to detect the phosphorylation event by the cAMP effector PKA. In the first example, the KID domain of the cAMP response element binding protein (CREB), which undergoes a PKA phosphorylation-dependent conformational change, is sandwiched between a blue FP and a green FP (Nagai et al., 2000). PKA phosphorylation of the sensor decreases the FRET between the two FPs. A second, more widely used design, called AKAR, was developed in 2001 (Zhang et al., 2001). AKAR consists of a peptidyl PKA substrate linked to a phospho-peptide binding domain, which is sandwiched between ECFP and Citrine (a yellow FP) (Figure 2B). PKA phosphorylation of the substrate peptide results in its binding to the phospho-peptide binding domain, which switches the sensor from an “open” state to a “closed” state and results in an increase in FRET. This design has been widely adapted for the development of sensors for other kinases.

For AKAR, over 20 improved or analogous variants have been developed by many laboratories, including making the sensor reversible (Zhang et al., 2005), expanding the color palette, and increasing its dynamic range (Figure 1 and Table 2) (Allen and Zhang, 2008, 2006; Demeautis et al., 2017; Herbst et al., 2011; Komatsu et al., 2011; Lam et al., 2012; Mo et al., 2020; Ni et al., 2011; Shcherbakova et al., 2018; Tao et al., 2015; Watabe et al., 2020). Improvement approaches include: using FP pairs with increased FRET efficiency; using cp-FPs to optimize relative FP orientation; optimizing the linkers between different domains within the sensor; and using FPs that are brighter, better folded, or of different colors. AKAR has also been adapted for fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM) measurements (Chen et al., 2014; Demeautis et al., 2017; Tang and Yasuda, 2017; Tillo et al., 2017), which has advantages for in tissue and in vivo imaging experiments (see further discussion in Imaging modalities). AKAR sensitivities can be tuned by subcellular targeting to sites of enriched PKA activity (Ma et al., 2018). The sensors AKAR3EV and Booster-PKA have been used to generate transgenic mice (Kamioka et al., 2012; Watabe et al., 2020). In addition, several non-FRET sensors based on the same phosphorylation sensing mechanisms have also been developed. These alternative signal-generating mechanisms include dimerization-dependent intensity change (Mehta et al., 2018), anisotropy (Ross et al., 2018) and change in fluorescence blinking properties (Mo et al., 2017), with the latter being used for localization based super-resolution imaging (Sigal et al., 2018; Zhong, 2015). These alternative imaging modalities, however, are yet to be demonstrated for in vivo use.

Table 2. PKA sensors and their properties.

Some numbers are estimated from figures and are preceded by “~” Abbreviations: DR: dynamic range; F: forskolin; I: IBMX; Iso: isoproterenol; 293 and 293T: HEK 293 and HEK 293T cells, respectively; LT: fluorescence lifetime; Rol: rolipram; MBs: mushroom bodies.

| Name | Publication | Mode | Corr. Authors | Sensing Mechanism | FPs | DR % (Cell, agonist)1 | Stim. EC50 (μM)1 | Other uses (DR % / Kd [μM])1 | In neuron / in vivo1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ART | Nagai et al., 2000 | FRET | Hagiwara. | Kemptide | RGFP-BGFP | ~20% (COS-7, dbcAMP) | - | - | - |

| AKAR1 | Zhang et al.,2001 | FRET | Tsien | 14–3-3τ (1)-PKA sub | CFP-YFP | ~40% (HeLa, Iso) | - | - | - |

| AKAR27 | Zhang et al., 2005 | FRET | Tsien | FHA1-PKA Sub | ECFP-Citrine | ~25% (293, Iso) | - | 17.5% (293, Iso)2 ~9.9% (293, F)3 | ~12% (cultured slice, F)4 ~20% (cultured neuron, F)5 ~18% (fly MBs, F+I)6 |

| AKAR3 | Allen & Zhang, 2006 | FRET | Zhang | FHA1-PKA Sub | ECFP-cp172Venus | 34.7% (293, Iso) | - | ~35% (293, Iso)8;~10% (HeLa, dbcAMP10;~0.2 ns (ΔLT, 293, F)9 | ~40% (cultured neurons, F)110.15 (cultured D1-MSNs, NPEC-DA)12 |

| RLuc-PCA PKA | Stefan et al., 2007 | Biolum. | Michnick | PKAr-PKAc | Rluc(split) | ~80% (293T, F+I) | - | - | - |

| CRY-AKAR | Allen & Zhang, 2008 | FRET | Zhang | FHA1-PKA Sub | Cerulean-mCherry-mVenus | 54% (HeLa, F)13 | - | - | - |

| AKAR-GR | Ni et al., 2011 | FRET | Levchenko & Zhang | FHA1-PKA Sub | EGFP-mCherry | ~25% (293, F) | - | - | - |

| ICUEPID | Ni et al., 2011 | FRET | Levchenko & Zhang | FHA1-PKA Sub & Epac1 | CFP-RFP-YFP | ~30% (293, F)13 | - | - | - |

| AKAR4 | Depry et al., 2011 | FRET | Zhang | FHA1-PKA Sub | Cerulean-cpVenus | ~58% (293, Iso) | - | 47%/~50 μM14, 51%15, or ~20%10 (HeLa, F, F+I or dbcAMP); | ~30% (ΔLT/LT0, cultured slices, F+I)16 |

| AKAR3EV7 | Komatsu et al., 2011 | FRET | Aoki | FHA1-EV-PKA Sub | Ypet-ECFP | ~60% (HeLa, dbcAMP) | - | ~23%17, 83.5%14, 78%15 (HeLa, F+I) 55%18 or ~20%18 (ΔLT/LT0) (HeLa, F) | ~20% or ~1.25% (in vivo, D1-SPNs, Sp-8-Br-cAMPS or foot shock)19,20; ~25% (cultured slices, F)22 |

| bimAKAR | Herbst et al., 2011 | FRET | Zhang | FHA1-PKA Sub | Ypet-Cerulean | 53.5% (293T, F) | - | - | - |

| LumAKAR | Herbst et al., 2011 | Biolum. | Zhang | FHA1-PKA Sub | RluC8(split)-mCherry | ~600% (293T, F) | - | - | - |

| AKAR2-CR | Lam et al., 2012 | FRET | Lin | FHA1-PKA Sub | Clover-mRuby2 | ~21.5% (293, F) | - | 8.1% (HEK, F+I)23 | - |

| FLIM-AKAR | Chen et al., 2014 | FLIM-FRET | Sabatini | FHA1-PKA Sub | meGFPΔ-cpsREACH | ~9% (ΔLT/LT0, 293, F) | - | - | 0.3524 ns (ΔLT), or ~16-17%9,16(ΔLT/LT0, cultured slices, F+I) ~0.16 or ~0.03 ns (ΔLT, in vivomouseD1-SPN, SKF81297 or reward)25 |

| PKA-KTR | Regot et al., 2014 | Transloc. | Regot & Covert | bNLS|NES | mClover | ~20% (3T3,C/N, F) | - | - | - |

| GakdYmut | Bonnot et al., 2014 | FLIM-FRET | Lambolez | FHA1-PKA Sub | GFP-darkYFP | 9% (ΔLT/LT0, BHK, F) | - | - | ~74% (cultured rat neurons, F)26~0.05% (ΔLT/LT0), (in vivo, mouse ctx dendr., photostim)22 |

| Gak | Bonnot et al., 2014 | Intensity | Lambolez | FHA1-PKA Sub | GFP | 10% (ΔLT/LT0, BHK, F) | - | - | ~47% (cultured rat neurons, F)26 |

| AKAR4.1 | Tao et al., 2015 | FRET | Day | FHA1-PKA Sub | mTurquoise-cpVenus | ~40% (293, F) | - | - | ~135% (in vivo, mouse liver, glucagon)27 |

| AKAR^dual | Demeautis et al., 2017 | FLIM | Riquet & Tramier | FHA1-PKA Sub | SsmOrange-mKate2 | ~0.06 ns, (ΔLT, HeLa , F/EGF) | - | - | - |

| AKAR5 | Tillo et al., 2017 | FLIM-FRET | Zhong | FHA1-PKA Sub | EGFP-sREACH | 0.2 ns (ΔLT, 293, F+I) | - | - | ~10% (ΔLT/LT0, cultured slices, F+I)16 |

| AKARet | Tang & Yasuda, 2017 | FLIM-FRET | Yasuda | FHA1-EV-PKA Sub | EGFP-sREAChet | ~0.23 ns (ΔLT, HeLa, F+I) | - | - | ~0.2 ns17 (ΔLT) or ~6%16 (ΔLT/LT0), cultured slices, F+I |

| ExRai-AKAR | Mehta et al., 2018 | Excit. Ratio. | Meht, Huganir & Zhang, | FHA1-PKA Sub | cpGFP | 144% (HeLa, F+I) | ~10-25, F 130% | (HeLa, F+I)12 | ~1514, ~40%15 (cultured neuron, F) |

| FLINC-AKAR1 | Mo et al., 2017 | FLINC | Zhang | FHA1-EV-PKA Sub | Dronpa-TagRFP-T | ~32% (norm. pcSOFI, HeLa, F+I) | - | - | - |

| NIR AKAR | Shcherbakova et al., 2018 | FRET | Verkhusha & Hodgson | FHA1-EV-PKA Sub | miRFP670-miRFP720 | ~5% (HeLa, 1 mM dbcAMP) | - | - | - |

| PKA-SPARK | Zhang et al., 2018 | Intensity | Shu | FHA1-PKA Sub | EGFP | - | - | - | - |

| sapphireAKAR | Mehta et al., 2018 | Intensity | Mehta, Huganir & Zhang, | FHA1-PKA Sub | cp-T-Sapphire | 19.5% (HeLa, F+I) | - | - | - |

| blueAKAR | Mehta et al., 2018 | Intensity | Mehta, Huganir & Zhang, | FHA1-PKA Sub | cpBFP | 16.2% (HeLa, F+I) | - | - | - |

| RAB-AKARev | Mehta et al., 2018 | Intensity | Mehta, Huganir & Zhang, | FHA1-PKA Sub | ddRFP-ddRFP | 17.2% (HeLa, F+I) | - | - | - |

| VcpV FLARE AKAR | Ross et al., 2018 | FRET | Rizzo & Zhang | FHA1-PKA Sub | Venus-cp172Venus | ~3% (293T, F+I) | - | - | - |

| VV FLARE AKAR | Ross et al., 2018 | FRET | Rizzo & Zhang | FHA1-PKA Sub | mVenus-mVenus | ~2% (293T, F+I) | - | - | - |

| mCh-mCh FLARE AKAR | Ross et al., 2018 | FRET | Rizzo & Zhang | FHA1-PKA Sub | mCherry-mCherry | ~1% (293T, F+I) | - | - | ~3% (in vivo mouse muscle, Iso)28 |

| hyBRET-PKA | Komatsu et al., 2018 | FRET/BRET | Matsuda | FHA1-EV-PKA Sub | mTurquoise-GL-YPet | ~60% (1mM dbcAMP + coelenterazine, HeLa) | - | - | - |

| tAKAR4α | Ma et al., 2018 | FRET | Mao & Zhong | FHA1-PKA Sub | EGFPΔ-cpsREACH | ~50% (cultured slices, F) | - | - | ~50% (cultured slices, F+I)16 |

| tAKARα | Ma et al., 2018 | FLIM-FRET | Mao & Zhong | FHA1-PKA Sub | EGFPΔ-cpsREACH | ~26% (ΔLT/LT0, cultured slices, F+I) | 17 nM,NE | - | ~26% (ΔLT/LT0, cultured slices, F+I)16~10% (ΔLT/LT0in vivo mouse motor ctx., locomotion)16 |

| Booster-PKA7 | Watabe et al., 2020 | FRET | Terai | FHA1-Booster-PKA Sub | mKate2-mKOκ | ~28% (ΔLT/LT0, HeLa, F); ~79% (HeLa, F) | ~1 μM, F; ~10 nM, Iso | - | ~40% (in vivo) mouse ear/intestine, ip/iv dbcAMP)18 |

| GR-AKAR3 | Mo et al., 2020 | FRET | Zhang | FHA1-EV-PKA Sub | EGFP-stagRFP | 44.6% (293T, F+I) or ~8% (ΔLT/LT0, 293T, F+I) | - | - | - |

| FluoSTEP-AKAR | Zhang et al., 2020 | FRET | Zhang | FHA1-PKA Sub | GFP1-10-mRuby2 | 8.6% (293-RIα, F) | - | - | - |

| ExRai-AKAR2 | Zhang et al., 2021 | Excit. Ratio. | Huganir, Mehta, & Zhang | FHA1-PKA Sub | cpGFP | 869% (HeLa, F+I) | ~10-25, F | - | 246% (cultured neurons, F)15; 3% in vivo mouse vis. ctx., locomotion15 |

For DR, ΔF/F0 for intensity sensors, ΔR/R0 for FRET sensors, and ΔLum/Lum0 for bioluminescence sensors, unless noted otherwise.

Sensor has been made into a transgenic mouse line

Ratio of RFP/CFP

While sensor development is still on-going, AKARs have been employed in many experiments, both in vitro (Castro et al., 2014; Sample et al., 2014; Yapo et al., 2017) and in vivo (see In vivo applications). One advantage of AKARs is that they are not expected to carry out endogenous functions, so their expression is likely benign, unless the expression levels become so high that they begin to saturate the enzymatic activity of PKA (Km ~30 μM for substrates; Adams et al., 1995). However, AKARs detect PKA phosphorylation events, which are one step downstream of cAMP and may potentially be also regulated by changes in phosphatase activities (Svenningsson et al., 2004). PKA has its own spatiotemporal regulations in addition to cAMP. Also, not all cAMP functions occur via PKA. Therefore, despite the success of AKARs, direct sensors for cAMP are still needed.

Multi-fluorophore cAMP sensors

Two types of single polypeptide FRET sensors for direct detection of cAMP were developed in 2004 (DiPilato et al., 2004; Nikolaev et al., 2004; Ponsioen et al., 2004). The first type is based on another cAMP effector Epac (Bos, 2003; De Rooij et al., 1998), which undergoes a large conformational change when binding to cAMP (Rehmann et al., 2006; White et al., 2012). Donor and acceptor fluorophores are attached to the N and C termini, respectively, of either the full-length or a truncated form of Epac1, resulting in FRET changes upon cAMP binding (Figure 2D) (DiPilato et al., 2004; Ponsioen et al., 2004). Subsequent developments include increasing its cAMP sensitivity, removing the endogenous function of Epac1, employing brighter and better-folded FPs, optimizing the fluorophore orientation using cp-FPs, reducing ion sensitivity, and reducing the tendency to aggregate in cells (DiPilato and Zhang, 2009; Klarenbeek et al., 2015, 2011; Mo et al., 2020; Ni et al., 2011; Polito et al., 2013; Ross et al., 2018; Salonikidis et al., 2011; van der Krogt et al., 2008; Violin et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2020). This class of sensors achieves some of the largest FRET responses among cAMP sensors, thanks in part to the large cAMP-dependent conformational change of Epac. However, the sensitivity remains low (EC50 ~4 μM; Klarenbeek et al., 2015) compared to the presumed cAMP concentration range in cells (~1 μM; Castro et al., 2014; Francis and Corbin, 1994; Koschinski and Zaccolo, 2017; Mironov et al., 2009). These sensors are also sizable because they include the majority of the large Epac protein, making it difficult to be packaged into AAV (<= 4.6 kb including the promotor and polyadenylation signal) for easy in vivo delivery. To overcome this limitation, a transgenic mouse expressing the sensor TEPACVV was generated (Klarenbeek et al., 2011; Muntean et al., 2018a); however, improved sensors in this family have since been developed (Figure 1, Klarenbeek et al., 2015).

The second type of cAMP sensor in this class is similar to the first, except that only the cAMP binding domain from Epac1, Epac2, or PKA-R, is used (Figure 2D) (Nikolaev et al., 2004). Later efforts also used the cAMP binding domains of the HCN channel (Nikolaev et al., 2006), other PKA-R variants (Ohta et al., 2016), or bacterial proteins (cit-mCNBD-Cer and mICNBD-FRET) (Krähling et al., 2013; Mukherjee et al., 2016). Some of these sensors exhibit high cAMP sensitivity (~0.1 μM) (Table 1). A version in which the acceptor is inserted in the middle of the cAMP-binding domain from PKA-R was also developed (CUTie), which is less sensitive to the influence from adjacent sequences when the sensor is tagged to other proteins (Surdo et al., 2017). These sensors, in particular those based on Epac cAMP binding domains, have been furthered developed (Castro et al., 2010; Norris et al., 2009) and have been used in a number of in vitro studies in neurons (Table 1; see also Castro et al, 2014). Several of these sensors have been used to generate transgenic mice (Calebiro et al., 2009; Mukherjee et al., 2016; Nikolaev et al., 2006; Psichas et al., 2016; Sprenger et al., 2015). One potential limitation of these sensors is that the cAMP binding domains in PKA and HCN channels are an integral part of a larger protein. Isolating this domain may expose hydrophobic surfaces originally involved in intra-protein interactions, which may increase the chance of protein misfolding and aggregations, as evident in sizing column chromatography experiments (Mukherjee et al., 2016). However, their much smaller size and presumed lack of endogenous effects other than cAMP buffering poise them for future development.

Single fluorophore cAMP and PKA sensors

With the success of the single fluorophore GCaMP family of calcium sensors (Chen et al., 2013; Nakai et al., 2001), recent efforts have been made to develop analogous single fluorophore cAMP sensors. GCaMPs use a cp-FP that is environmentally sensitive. Binding of calcium/calmodulin to the M13 peptide in GCaMP results in conformational rearrangements that changes the pKa of the fluorophore and shift it from a neutral (low fluorescence) to an anionic form (high fluorescence) (Barnett et al., 2017). Similar ideas of coupling cAMP-dependent conformational changes to cp-FPs have resulted in several single fluorophore sensors, including two red-shifted variants (Figures 1 and 2E, and Table 1; Hackley et al., 2018; Harada et al., 2017; Kitaguchi et al., 2013; Odaka et al., 2014; Ohta et al., 2018; Tewson et al., 2016). The cAMP sensing mechanisms include the cAMP binding domain of Epac1 or PKA-RIα, the entire Epac2 protein, and the cAMP-dependent dissociation of PKA-C and PKA-R. Some of these sensors are reported to exhibit large dynamic ranges, although the largest ones of these, R-FlincA (ΔF/F0 ~6) and Pink Flamindo (ΔF/F0 ~2.5), best mature at temperatures below 37 °C (Harada et al., 2017; Ohta et al., 2018). Many of these sensors have yet to be extensively characterized. Similar to their FRET counterparts, certain sensors potentially contain exposed hydrophobic surfaces of cAMP binding domains. Nonetheless, some of these sensors have been used in neurons in vitro (Table 1), and, in one study, in astrocytes in vivo (Oe et al., 2020).

Analogous single fluorophore sensors for detecting PKA phosphorylation, as exemplified by ExRai-AKAR, have also been developed (Figure 2C) (Bonnot et al., 2014; Mehta et al., 2018), including an improved variant (EXRai-AKAR2) that achieves a large dynamic range (~10 fold using an excitation ratiometric readout; Zhang et al., 2021a). Similar to AKAR, ExRai-AKAR utilizes the binding of a phospho-peptide binding domain to a phosphorylated PKA substrate sequence, and couples this binding to cp-FPs. Several color variants are available, although with different dynamic ranges and properties. ExRai-AKAR2 has been demonstrated to work in vivo. However, the requirement of imaging using two excitation wavelengths to achieve its maximal dynamic range makes it challenging to carry out high-speed imaging in vivo. Nonetheless, with GCaMP as the leading example, the single fluorophore cAMP and PKA sensors have great potential given their smaller sizes compared to FRET-based sensors and their potential for having a large dynamic range.

Bioluminescence and BRET sensors

Although this review focuses on fluorescence sensors, there are also a number of bioluminescence and BRET (bioluminescence-resonance energy transfer) sensors for both cAMP and PKA (Barak et al., 2008; Binkowski et al., 2011; Fan et al., 2008; Herbst et al., 2011; Jiang et al., 2007; Prinz et al., 2006; Saito et al., 2012; Stefan et al., 2007). There are also hybrid sensors that can be used for either fluorescence or bioluminescence (French et al., 2019; Komatsu et al., 2018; Watabe et al., 2020). Bioluminescence sensors utilize cAMP binding or PKA phosphorylation to change the activity of a luciferase, which can emit photons when it hydrolyzes a substrate. These sensors are also included in Figure 1, and Tables 1 and 2. While they serve as an alternative to fluorescence imaging, bioluminescence remains dim (Saito et al., 2012), and it requires the application of substrates. They also cannot be focally excited, and are therefore incompatible with two-photon microscopy. Overall, although these sensors can generate useful signals in vivo (e.g., in tumor detection), their use in high contrast imaging remains difficult.

Other sensors

Other types of cAMP sensors have also been developed. A cAMP-gated non-selective cation channel was used to elicit cAMP-dependent calcium influx, which can then be detected using a calcium sensor (Rich et al., 2001b, 2001a). However, the channel may interfere with cell physiology by changing membrane voltage and intracellular calcium dynamics. It is also not easy to separate cAMP responses from endogenous calcium responses. Other approaches have been to convert PKA phosphorylation events into changes in FP localization, either from the nucleus to the cytosol, or from even distributions to aggregates (Regot et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2018). However, in neurons, it is not clear whether these sensors can respond to localized (i.e., compartmentalized) PKA activity, and whether the translocation or aggregation take additional time beyond cAMP/PKA kinetics.

Sensor targeting

Orthogonal to sensor development, many cAMP/PKA sensors have been tagged to specific proteins or subcellular targeting motifs. This allows the visualization of unique, compartmentalized cAMP and/or PKA patterns (e.g., Dodge-Kafka et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2001). Certain sensor variants, which are only functional when they properly bind to a peptide tag knocked-in to label an endogenous protein, have also been developed (Zhang et al., 2020). Sometimes, subcellular targeting to sites of enriched signaling activities can result in increased sensitivity and dynamic range of the sensor, thereby enhancing its practical use (Ma et al., 2018). Notably, the performance of certain sensors may also be decreased by tethering to proteins (Surdo et al., 2017). Due to the large combinatorial possibility of tagged sensors, we do not systematically include them in the Tables or further discuss in the review. However, sensor targeting offers an important approach to dissect the subcellular signaling mechanisms associated with cAMP/PKA and to tune sensor performance.

Imaging modalities

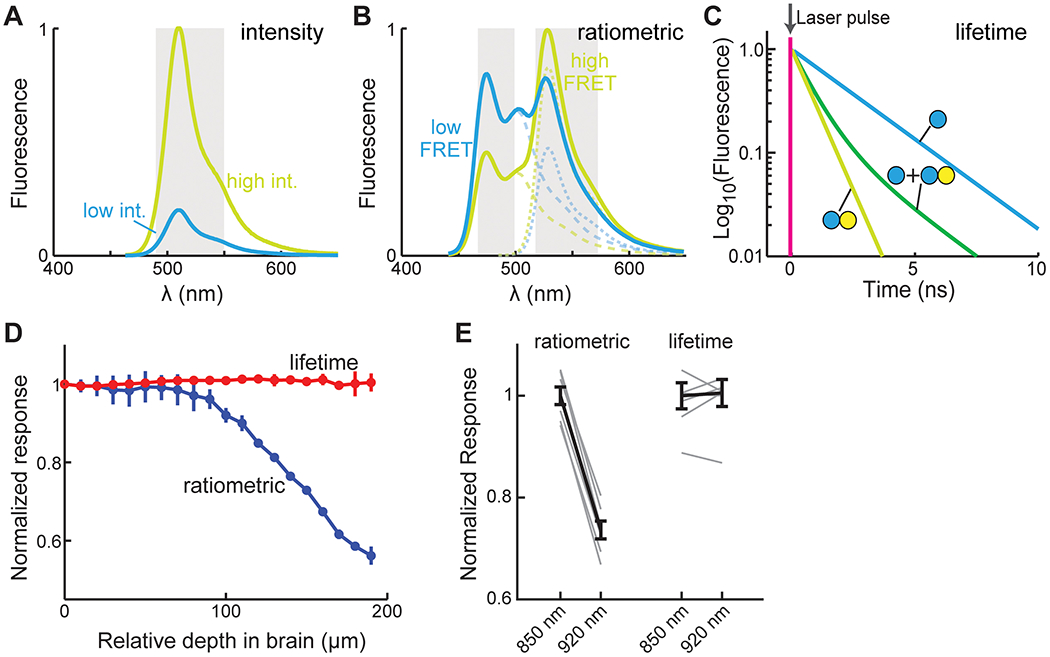

Regardless of the sensing mechanism, the aforementioned fluorescence sensors fall into two categories: single-or multi-fluorophore. Single fluorophore sensors are most typically measured by intensity changes (Figure 3A), although some can also be measured using excitation-ratiometric measurements or FLIM (Figure 3C; see below). Multi-fluorophore sensors are typically based on FRET and are measured by ratiometric imaging (Figure 3B) or FLIM (Figure 3C). As discussed earlier, some multi-fluorophore sensors utilize non-FRET mechanisms, such as intensity change, anisotropy, or fluorescence blinking. Below we will discuss the general features and the pros and cons of the three mainstream imaging modalities: intensity, ratiometric, and FLIM, in the context of in vivo imaging.

Figure 3. Measurements and comparisons of different imaging modalities.

(A) The changes in the emission spectrums of a hypothetical intensity-based sensor of both the low (cyan) and high intensity (yellow-green) states. Gray bars indicate the potential collection band. (B) The changes in the summed emission spectrums (thick solid lines) and the individual FP components (dash lines) of a hypothetical FRET-based sensor of both the low (cyan) and high FRET (yellowish green) states. The potential collection band for ratiometric imaging is indicated (gray). (C) The changes in the fluorescence lifetime of the donor fluorophore of a hypothetical FRET-based sensor of both no FRET (cyan) and FRET (yellow-green) states. Populations with mixed states (dashed line) can be fit to derive the relative percentages of molecules in each state (i.e., the binding ratio). (D) Two-photon ratiometric and FLIM measurements of a FRET based cAMP sensor (fluorophores being mTurquoise2 and mVenus) in the cortex of a mouse in vivo across different depths when the mouse was quiet. (E) Ratiometric and FLIM measurements of a FRET based cAMP sensor (same as in panel D) in HEK 293 cells using the indicated two-photon excitation wavelengths.

Intensity measurements

Single fluorophore sensors are typically detected within a single fluorescence band (Figure 3A), making it simple to measure and easy to multiplex with a different reporter of another color, such as a calcium sensor. Fully optimized single fluorophore sensors hold the promise to exhibit very large dynamics ranges. Furthermore, the use of a single FP makes these sensors small, facilitating their use, such as packaging into AAV or co-expression with additional sensors. One caveat is that the signal intensity is determined by both the activity and the concentration of the sensor. These two aspects are not easily separable in living cells, making it sometimes difficult to interpret results. During in vivo imaging, drifting in the field of view is nearly inevitable due to hemodynamics and animal movement. Although the fast, reversible jittering of image frames can be computationally corrected, cAMP and PKA signaling events occur on a relatively slow timescale (~ seconds to hours). Slow drifting, such as that in the focus over a long time, may be difficult to correct. In practice, intensity imaging in vivo has high requirements for sensor response range. For example, in vivo GCaMP imaging became widely applicable with the development of GCaMP6, which achieves a signal (ΔF/F0) of 0.25 for a single action potential and ~5 for large physiological stimuli (10 action potentials; Chen et al., 2013).

Ratiometric measurements.

FRET sensors are conventionally measured by the ratio between the emission fluorescence intensities of the donor and acceptor fluorophores (Figure 3B). This can be readily carried out using many types of microscopes, including in vivo two-photon microscopes. Ratiometric calculation cancels out the effect of the number of molecules, and is therefore less sensitive to sensor concentration variations and movement artifacts. Ratiometric imaging has been successfully applied in many experiments. However, ratiometric FRET signals are the integrated result of two different properties: the FRET efficiency between the fluorophore pair in each conformation state, and the relative proportion of molecules in each state. These two properties cannot be easily separated. In the context of in vivo imaging in brain tissues, ratiometric measurements are affected by wavelength-dependent light scattering (Figure 3D), making it difficult to compare sensor activity across cells in different tissue depths or under different imaging conditions. Ratiometric measurement is also sensitive to experimental parameters, such as the exact excitation wavelengths (e.g., Figure 3E) and collected emission bands. In addition, ratiometric measurements use two color channels, reducing the ease of multiplex imaging with additional reporters.

FLIM measurements

An emerging way to measure FRET is FLIM, which measures the fluorescence lifetime, i.e., the time (~ ns) elapsed from fluorophore excitation to fluorescence photon emission, of the donor fluorophore of a FRET pair (Figure 3C) (Yasuda, 2006; Yellen and Mongeon, 2015). The donor lifetime is decreased by FRET, and the relative ratio between different FRET states (called the “binding ratio”) can be determined by curve fitting with multiple components corresponding to the donor lifetime in each state (Figure 3C). Thus, the two intertwining parameters, FRET efficiency and binding ratios, can be separated. For ease of data interpretation, fluorophores with single exponential lifetime decays are better suited for FLIM.

In the context of in vivo imaging, FLIM provides the combined advantages of both intensity and ratiometric imaging. Fluorescence lifetime is independent of fluorophore concentrations, making FLIM measurements relatively insensitive to drifting. It only measures the donor fluorescence, and therefore is not sensitive to wavelength-dependent light scattering (Figure 3D) or microscope-specific parameters (Figure 3E). These properties enable easy comparison of sensor activity across cells and experiments. A dark acceptor (a fluorophore that can absorb, but with low quantum yield) can be used so that it frees up a color channel for multiplex imaging. However, FLIM-FRET sensors tend to have small signals. Theoretically, the best signal-to-noise ratio for determining the binding ratio (i.e., the percentage of donor fluorophores bound to acceptors) occurs at a FRET efficiency of ~60% (Yasuda, 2006), corresponding to a maximal 2.5-fold change even if the binding ratio changes from 100 to 0%, which is in fact unachievable because FPs do not mature to 100% (Murakoshi et al., 2008). Nevertheless, thanks to its advantages, two-photon FLIM (2pFLIM) has been successfully applied to imaging several AKAR sensors in vivo during animal behavior (see In vivo applications). Many cAMP and PKA sensors have been characterized or adapted for FLIM measurements (e.g., Klarenbeek et al., 2015, 2011; Mukherjee et al., 2016; van der Krogt et al., 2008). Notably, certain single fluorophore sensors, such as the calcium sensor RCaMP (Díaz-García et al., 2017) and the cAMP sensor GAk (Bonnot et al., 2014), also exhibit lifetime change, and can take advantage of FLIM measurements. FLIM is becoming increasingly available through commercial sources or adaptation of existing microscopes, and it can be as fast as any two-photon microscope (Colgan et al., 2018; Yellen and Mongeon, 2015). FLIM is becoming a useful modality for imaging cAMP and PKA sensors.

Other imaging modalities.

As described earlier, sensors based on anisotropy and molecule blinking have been developed (Mo et al., 2017; Ross et al., 2018). However, the response for the anisotropy sensors, which are measured by the loss of polarization of emission light (Yasuda, 2006), remains small. Although the molecular blinking sensors can be used in localization based super-resolution imaging in vitro (Sigal et al., 2018; Zhong, 2015), it is not clear whether they offer advantages in vivo where super-resolution imaging is difficult. Nevertheless, these sensors highlight the possibility of additional ways to sensing cAMP/PKA activity, and further developments may result in novel sensors for new research avenues.

No one size fits all

It is challenging to choose among the large number of cAMP and PKA sensors (Figure 1, and Tables 1 and 2) for one’s experiments. An ideal sensor would have a large dynamic range, high signal-to-noise responses to physiological activities, little interference with cellular functions, fast enough kinetics to follow endogenous signaling dynamics, high brightness to stand out of the background, high photostability to allow for repeated imaging, minimal photodamage to the cell post-excitation, and excitation/emission spectra that allow for easy multiplex imaging with other reporters. Such a sensor is not currently available, and this is likely to continue in the near future. Here, we discuss our views regarding several key properties that are important to consider when selecting or developing a sensor.

Considerations for choosing and developing cAMP/PKA sensors

Ultimately, an experimenter hopes to detect a signal with a sufficient signal-to-noise ratio with little interference to physiological function. To achieve a larger signal, much effort has focused on increasing a sensor’s dynamic range. However, sensitivity is also important for fully utilizing a finite dynamic range. Many current cAMP and PKA sensors exhibit much smaller responses to physiological stimuli in neurons compared to their maximal dynamic ranges (e.g., see Ma et al., 2018). Other sensors have an affinity that is likely too high for intracellular cAMP (e.g., Mukherjee et al., 2016; Ohta et al., 2016), although they may be used under certain circumstances. Sensor choices and future development efforts may benefit from an emphasis on obtaining the maximal response under physiologically relevant conditions.

It is worth noting that a large apparent dynamic range does not always translate to a high signal-to-noise ratio. For ratiometric measurements, the signal-to-noise ratio is determined by the noisier of the two FP measurements that give rise to the fluorescence ratios. In addition, for all measurements, the signal-to-noise ratio is affected by the collected photon counts. If there are two hypothetical intensity-based sensors with identical responses (e.g., the same ΔF/F0), but one is 10-fold dimmer, the dimmer sensor will achieve a lower signal-to-noise ratio under the same conditions. Photostability also affects the possible photon counts before the fluorophore is bleached. Since the exact brightness (i.e., extinction coefficient multiplied by quantum yield) and photostability of most cAMP and PKA sensors have not been determined, it is difficult to evaluate the achievable signal-to-noise ratio of these sensors. In addition, while most sensors are developed under single photon excitation, the response amplitude of a sensor may be different under two-photon excitation, which is necessary for high-contrast imaging in vivo.

For the above reasons, it remains difficult to evaluate sensors. Side-by-side comparisons of the signal-to-noise ratio per unit concentration of sensors using a physiologically-relevant stimulation in a realistic sample may facilitate both sensor selection and sensor development (e.g., see Mao et al., 2008 for comparing calcium sensors). However, this requires rigorous calibration experiments that are not trivial. Before such comparisons are available, a good practice would be to compare several promising sensors in the user’s hands. To facilitate the initial selection, we list in Tables 1 and 2 the reported dynamic ranges and affinities of sensors when they are available. Independent measurements are critical because sensors are often optimized based on particular experimental parameters in a developer’s lab, which may not translate to end users. Demonstrations in the challenging in vivo imaging conditions may also be useful indications. Therefore, we list additional uses beyond the original publication, as well as applications in neurons and in vivo in the Tables. Due to the enormous body of literature, our list cannot be exhaustive, but it is instead aimed at giving researchers an entry point.

Kinetics are also important to consider. The on- and off-rates are not determined for the majority of cAMP and PKA sensors. Although the kinetics of cAMP sensors can be determined using a fast flow device, doing so for PKA sensors is difficult because it is nearly impossible to recapitulate endogenous PKA and phosphatase concentrations in test tubes. In one example of a solution, the kinetics of the PKA sensor tAKARα in neurons was found to match that of slow afterhyperpolarization, an electrophysiological readout of neuromodulation-elicited PKA phosphorylation (Ma et al., 2018). Other potential factors to consider include protein maturation, aggregation, and photostability. We empirically found that the majority of RFPs exhibit either significant maturation issues (as reflected by unwanted green components), a high tendency to form aggregates, and/or photo-instability (see also Gross et al., 2000; Katayama et al., 2008). Red sensors are of great interest for multiplex imaging. However, the above issues of RFPs may potentially translate to the sensors. Users may need to experimentally evaluate on a sensor-to-sensor basis.

The observer effect

The expression of sensors may interfere with neuronal functions. One possibility is buffering (for calcium sensor buffering, see McMahon and Jackson, 2018). FPs and sensors are likely expressed on the order of 1–10 μM (Cherkas et al., 2018) , whereas cAMP is thought to operate in a range of ~1 μM (Castro et al., 2014; Francis and Corbin, 1994; Koschinski and Zaccolo, 2017; Mironov et al., 2009). If the sensor has an affinity comparable to physiological cAMP concentrations, the majority of cAMP produced may be bound to the sensor, resulting in its removal from physiological functions, reduction of the signal amplitude, and extended durations of cAMP activity. However, there is likely a significant level of endogenous cAMP buffer that may mitigate the buffering effect (Bock et al., 2020). In this aspect, PKA sensors have an advantage as long as the sensor concentration does not outrun the maximal rate of the enzyme (Km ~ 30 μM) (Adams et al., 1995). One way to characterize the buffering effect is to examine whether the observed response is concentration dependent (Castro et al, 2014). Additionally, sensors may affect neuronal function in other ways. For example, as mentioned earlier, some sensors may have unintendedly exposed hydrophobic regions of cAMP binding domains that have potential for non-specific protein-protein interactions. It is important to experimentally characterize whether sensor expression may affect neuronal function and health.

A potential artifact can arise when signaling compartmentalization or diffusion is of interest, if the diffusion rates are mismatched between the sensor and endogenous cAMP or PKA. In calcium imaging, it is well documented that high affinity soluble calcium sensors can artificially increase the diffusion range of calcium (Sabatini et al., 2002). Typical cAMP sensors are free diffusing in cells, but recent evidence points to strong immobile intracellular cAMP buffers (Bock et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020), which limits the diffusion of cAMP. Additional diffusion barriers formed by phosphodiesterases can also constrain the diffusion of cAMP (Dodge-Kafka et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2020). Binding of cAMP to the sensor may allow it to escape from the sequestration by immobile buffers or from the degradation by phosphodiesterases, resulting in an apparent diffusion that is non-physiological.

Ground truth

It is often desired to convert the sensor signal to a direct biologically relevant parameter, such as cAMP concentration (Börner et al., 2011; Castro et al., 2014; Koschinski and Zaccolo, 2017; Mironov et al., 2009; Muntean et al., 2018a). However, this is not always straightforward. Since the signals of single fluorophore sensors depend on fluorophore concentration, they cannot be directly used to infer the cAMP concentration, unless both the dissociation constant and the signals at zero and maximal cAMP concentrations are known. This is often not possible in living cells or in vivo. A basal concentration of cAMP likely exists in most cells, and even the strongest pharmacological manipulation may not be able to elicit cAMP concentrations sufficient to saturate a sensor. Although ratiometric imaging can mitigate the confounding factor of sensor concentration, the experiment remains challenging. When two FPs, for example, ECFP and mVenus (YFP), are fused to each other and expressed in cells, the fluorescence ratio between the two fluorophores may vary significantly across cells (data not shown). This is possibly due to variations in the FP maturation efficiency resulting from subtle differences in intracellular environments (Murakoshi et al., 2008). In addition, the sensor signal has to be calibrated against cAMP concentrations in vitro (Börner et al., 2011; Koschinski and Zaccolo, 2019). Nevertheless, sensors may be potentially sensitive to differences between intracellular and test tube environments, including pH, ionic composition and concentration, and protein concentration. In particular, few studies have attempted to control protein concentration in test tube experiments. However, we found that immunopurification of a cAMP sensor resulted in a much-attenuated dynamic range (data not shown). Inclusion of 1 – 2% BSA in solution restores a large part of the dynamic range. Finally, the aforementioned buffering effect may alter the cAMP concentration compared to unperturbed cells. Overall, inferring the ground truth is of great importance, but it needs to be done carefully and with associated caveats in mind.

In vivo applications

Because of the importance of cAMP and PKA, much effort has also been devoted to the application of the cAMP/PKA sensors in biological contexts. In neuroscience, there have been numerous applications in vitro (e.g., see reviews in Castro et al., 2014; Gorshkov and Zhang, 2014). We therefore include a non-comprehensive list of some of the references in Tables 1 and 2 to provide readers an entry point into this work. At the same time, many integral functions of cAMP — neuromodulation, learning, memory, and psychiatric function — necessitate an understanding in the intact, behaving animal. Imaging in intact tissue, particularly in awake, behaving animals, imposes high demands on sensor brightness, dynamic range, and sensitivity, as well as on gene delivery, microscopy, and behavioral assays. Thanks to continuous development efforts, in vivo cAMP/PKA imaging has started to become a possibility in recent years. While further progress is still needed, this capability has great promise. Below, we summarize recent efforts in the field.

Multiple AKAR family PKA sensors have been used recently for imaging studies in the intact nervous system. As one of the most notable places of neuromodulatory PKA signaling, the striatum has been used as an early testing ground. The FRET-based sensor AKAR3EV was first used in combination with a fiber based microendoscope. PKA activity in the D1- and D2-SPNs was found to be modulated by cocaine administration or aversive electric shocks in the dorsal striatum (Goto et al., 2015), whereas aversive memory formation and retrieval were associated with, and possibly mediated by, PKA activity dynamics in the ventral striatum (Yamaguchi et al., 2015). FLIM-AKAR in combination with fluorescence lifetime photometry has also been used to measure dopamine-dependent PKA activity in mouse striatal SPNs during food-reward behaviors (Lee et al., 2020). A subcellularly-targeted, more sensitive version of FLIM-AKAR called tAKARα has been used to achieve the first cellular-resolution two-photon FLIM imaging in mouse cortical neurons (Jongbloets et al., 2019; Ma et al., 2018), in which PKA activities were found to be associated with animal wakefulness and locomotion in part mediated by the neuromodulator norepinephrine. The single fluorophore PKA sensor ExRai-AKAR2 has also been used to detect locomotion-induced activity in the visual cortex (Zhang et al., 2021a). Several other AKARs have been used in both neuronal and non-neuronal cell types in vivo that detected responses to optogenetic or pharmacological manipulations, showing their promise for future behavioral studies (Gervasi et al., 2010; Lissandron et al., 2007; Nomura et al., 2020; Ross et al., 2018; Tao et al., 2015; Watabe et al., 2020). Compared to PKA sensors, fewer studies have applied direct cAMP sensors in vivo. The red intensity cAMP sensor Pink Flamindo has been used recently to image noradrenergic signaling in response to aversive stimuli in mouse cortical astrocytes (Oe et al., 2020).

To date, no cAMP sensor has been used to image neuronal cAMP dynamics during behavior. PKA imaging in vivo also remains difficult and has been achieved in only a small number of laboratories. However, with continuous development of the cAMP sensors and associated microscopy, in vivo cAMP/PKA imaging is poised to become increasingly practical for broad applications in many laboratories.

Closing remarks

cAMP plays key roles in a plethora of neuronal functions. The spatiotemporal controls of cAMP activities demand imaging studies with matched spatiotemporal resolution. Towards this goal, many genetically encoded sensors for cAMP and its major effector PKA have been developed. Some have started to be applied in vivo. Nonetheless, challenges remain to further improve these sensors to achieve high signal-to-noise measurements under physiological conditions, especially for in vivo applications. With continuous developmental efforts, we look forward to a time when in vivo cAMP imaging becomes routinely carried out in a large number of laboratories similar to the way that calcium imaging is used today. In addition to sensors for imaging, the field can also benefit from further developments in optically controllable tools for manipulating the cAMP and PKA pathways, such as photoactivatable adenylyl cyclases and photoactivatable PKI (Sample et al., 2014; Yi et al., 2014). These tools, when optimized, may be used in combination with cAMP/PKA imaging to revolutionize our ability to address previously unattainable mechanistic questions regarding the neuromodulation underlying animal behavior and function.

Highlights.

Summary of genetically encoded sensors of cAMP and PKA to date.

Tabulation of the history, dynamic range, and sensitivity of each sensor.

Introduction of the major imaging modalities for usage of these sensors.

Discussion of the important parameters to consider for choosing a sensor.

Review of recent In vivo applications of these sensors.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Jin Zhang, Mr. Jinfan Zhang, and Ms. Julia Hardy at University of California San Diego, and Drs. Corette Wierenga and Bart Jongbloets at Utrecht University for critical comments. This work was supported by two NIH/BRAIN Initiative grant (R01NS104944 and RF1MH120119) to H.Z. and T.M., and an NIH/NINDS R01 (R01NS081071) to T.M.

Acronyms and Abbreviations

- 2p

Two-photon

- AAV

Adeno-associated virus

- AC

Adenylyl Cyclase

- AKAR

A kinase activity reporter

- AKAR-EV

AKAR with Eevee (enhanced visualization by evading extraFRET) linker

- ART

cAMP-responsive tracer

- BRET

Bioluminescence Resonance Energy Transfer

- cAMP

Cyclic Adenosine Monophosphate

- cAMPr

cAMP reporter

- CAMYEL

cAMP sensor using YFP-Epac-RLuc

- cit-mCNBD-Cer

cyclic nucleotide receptor involved in sperm function-based cAMP biosensor

- CNBD

Cyclic nucleotide binding domain

- CREB

cAMP Response Element Binding Protein

- CUTie

cAMP universal tag for imaging experiments

- ddFP

Dimerization-dependent FP

- DNBD

DNA binding domain

- DR

Dynamic Range

- EBFP/ECFP/EGFP/EYFP

Enhanced blue/cyan/green/yellow FP

- ExRai-AKAR

Excitation-ratiometric PKA activity reporter

- F/Fsk

Forskolin

- FHA domain

Forkhead-associated domain

- Flamindo

Fluorescent cAMP indicator

- FLARE

Fluorescence Anisotropy Reporters

- FlCRhR

Fluorescein-Catalytic-Rhodamine-Regulatory

- FLIM

Fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy

- FLINC

Fluorescence fluctuation increase by contact

- FP

Fluorescent Protein

- FRET

Fluorescence resonance energy transfer

- GAk

GFP-A-Kinase

- GCaMP

GFP-Calmodulin-M13 peptide

- GeNL

mNeonGreen-NanoLantern

- HCN

Hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated

- hyBRET

BRET-FRET hybrid biosensors

- I/IBMX

3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine

- ICUE

Indicator of cAMP using Epac

- Iso

Isoproterenol

- Kd

Dissociation constant

- mlCNBD-FRET

MlotiK1-CNBD FRET sensor

- NIR

Near-infrared

- pcSOFI

Photochromic stochastic optical fluctuation imaging

- PDE

Phosphodiesterase

- PHT-PKA

Paul Herschel Tewson PKA sensor

- pKa

The negative log of the acid dissociation constant (Ka)

- PKA

Protein Kinase A

- PKA Sub

PKA Substrate (LRRATLVD)

- PKA-KTR

PKA kinase translocation reporter

- PKA-R, PKA-C

PKA regulatory and catalytic subunits

- PKA-RI or RII

PKA-R

- PKI

Protein kinase inhibitor peptide

- POPDC

Popeye domain containing protein

- R-FlincA

Red fluorescent indicator for cAMP

- RCaMP2

RFP-Calmodulin-M13 peptide, 2nd generation

- RFP

Red Fluorescent Protein

- RGFP

Red-shifted green fluorescent protein

- RLuc

Renilla luciferase

- Rol

Rolipram

- sREACh

Super-REACH (Resonance Energy-Accepting Chromoprotein)

- TIRF

Total Internal Reflection Microscopy

- x-camps

x-cAMP sensor

- YPet

YFP for energy transfer

- ΔDEP-CD

Without DEP domain, catalytically dead

- ΔF/F0, ΔR/R0, ΔLT/LT0

Change in fluorescence, ratio, or lifetime, normalized to baseline

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Adams JA, McGlone ML, Gibson R, Taylor SS, 1995. Phosphorylation Modulates Catalytic Function and Regulation in the cAMP-Dependent Protein Kinase. Biochemistry 34. 10.1021/bi00008a007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams SR, Harootunian AT, Buechler YJ, Taylor SS, Tsien RY, 1991. Fluorescence ratio imaging of cyclic AMP in single cells. Nature 349, 694–697. 10.1038/349694a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alford SC, Abdelfattah AS, Ding Y, Campbell RE, 2012a. A fluorogenic red fluorescent protein heterodimer. Chem. Biol 19. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2012.01.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alford SC, Ding Y, Simmen T, Campbell RE, 2012b. Dimerization-dependent green and yellow fluorescent proteins. ACS Synth. Biol 1. 10.1021/sb300050j [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen MD, Zhang J, 2008. A tunable FRET circuit for engineering fluorescent biosensors. Angew. Chemie - Int. Ed 47, 500–502. 10.1002/anie.200703493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen MD, Zhang J, 2006. Subcellular dynamics of protein kinase A activity visualized by FRET-based reporters. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 348, 716–721. 10.1016/J.BBRC.2006.07.136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baillie GS, Tejeda GS, Kelly MP, 2019. Therapeutic targeting of 3’,5’-cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases: inhibition and beyond. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 10.1038/S41573-019-0033-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barak LS, Salahpour A, Zhang X, Masri B, Sotnikova TD, Ramsey AJ, Violin JD, Lefkowitz RJ, Caron MG, Gainetdinov RR, 2008. Pharmacological characterization of membrane-expressed human trace amine-associated receptor 1 (TAAR1) by a bioluminescence resonance energy transfer cAMP biosensor. Mol. Pharmacol 74, 585–594. 10.1124/mol.108.048884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett LM, Hughes TE, Drobizhev M, 2017. Deciphering the molecular mechanism responsible for GCaMP6m’s Ca2+-dependent change in fluorescence. PLoS One 12. 10.1371/journal.pone.0170934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beavo JA, Brunton LL, 2002. Cyclic nucleotide research — still expanding after half a century. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 3, 710–717. 10.1038/nrm911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman HM, Ten Eyck LF, Goodsell DS, Haste NM, Kornev A, Taylor SS, 2005. The cAMP binding domain: An ancient signaling module. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 102, 45–50. 10.1073/pnas.0408579102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biel M, 2009. Cyclic nucleotide-regulated cation channels. J. Biol. Chem 10.1074/jbc.R800075200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binkowski BF, Butler BL, Stecha PF, Eggers CT, Otto P, Zimmerman K, Vidugiris G, Wood MG, Encell LP, Fan F, Wood KV, 2011. A luminescent biosensor with increased dynamic range for intracellular cAMP. ACS Chem. Biol 6, 1193–1197. 10.1021/cb200248h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock A, Annibale P, Konrad C, Hannawacker A, Anton SE, Maiellaro I, Zabel U, Sivaramakrishnan S, Falcke M, Lohse MJ, 2020. Optical Mapping of cAMP Signaling at the Nanometer Scale. Cell 182. 10.1016/j.cell.2020.07.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnot A, Guiot E, Hepp R, Cavellini L, Tricoire L, Lambolez B, 2014. Single-fluorophore biosensors based on conformation-sensitive GFP variants. FASEB J. 28, 1375–1385. 10.1096/fj.13-240507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Börner S, Schwede F, Schlipp A, Berisha F, Calebiro D, Lohse MJ, Nikolaev VO, 2011. FRET measurements of intracellular cAMP concentrations and cAMP analog permeability in intact cells. Nat. Protoc 6. 10.1038/nprot.2010.198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bos JL, 2003. Epac: a new cAMP target and new avenues in cAMP research. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 4, 733–738. 10.1038/nrm1197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourtchouladze R, Patterson SL, Kelly MP, Kreibich A, Kandel ER, Abel T, 2006. Chronically increased Gsα signaling disrupts associative and spatial learning. Learn. Mem 13, 745–752. 10.1101/lm.354106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buxton ILO, Brunton LL, 1983. Compartments of cyclic AMP and protein kinase in mammalian cardiomyocytes. J. Biol. Chem 258, 10233–10239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calebiro D, Nikolaev VO, Gagliani MC, de Filippis T, Dees C, Tacchetti C, Persani L, Lohse MJ, 2009. Persistent cAMP-Signals Triggered by Internalized G-Protein-Coupled Receptors. PLoS Biol. 7, e1000172. 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro LRV, Brito M, Guiot E, Polito M, Korn CW, Hervé D, Girault JA, Paupardin-Tritsch D, Vincent P, 2013. Striatal neurones have a specific ability to respond to phasic dopamine release. J. Physiol 591. 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.252197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro LRV, Gervasi N, Guiot E, Cavellini L, Nikolaev VO, Paupardin-Tritsch D, Vincent P, 2010. Type 4 phosphodiesterase plays different integrating roles in different cellular domains in pyramidal cortical neurons. J. Neurosci 30, 6143–6151. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5851-09.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro LRV, Guiot E, Polito M, Paupardin-Tritsch D, Vincent P, 2014. Decoding spatial and temporal features of neuronal cAMP/PKA signaling with FRET biosensors. Biotechnol. J 10.1002/biot.201300202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen TW, Wardill TJ, Sun Y, Pulver SR, Renninger SL, Baohan A, Schreiter ER, Kerr RA, Orger MB, Jayaraman V, Looger LL, Svoboda K, Kim DS, 2013. Ultrasensitive fluorescent proteins for imaging neuronal activity. Nature 499. 10.1038/nature12354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Granger AJ, Tran T, Saulnier JL, Kirkwood A, Sabatini BL, 2017. Endogenous Gαq-Coupled Neuromodulator Receptors Activate Protein Kinase A. Neuron 96, 1070–1083.e5. 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.10.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Saulnier JL, Yellen G, Sabatini BL, 2014. A PKA activity sensor for quantitative analysis of endogenous GPCR signaling via 2-photon FRET-FLIM imaging. Front. Pharmacol 5, 56. 10.3389/fphar.2014.00056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherkas V, Grebenyuk S, Osypenko D, Dovgan AV, Grushevskyi EO, Yedutenko M, Sheremet Y, Dromaretsky A, Bozhenko A, Agashkov K, Kononenko NI, Belan P, 2018. Measurement of intracellular concentration of fluorescently-labeled targets in living cells. PLoS One 13. 10.1371/journal.pone.0194031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colgan LA, Hu M, Misler JA, Parra-Bueno P, Moran CM, Leitges M, Yasuda R, 2018. PKCα integrates spatiotemporally distinct Ca 2+ and autocrine BDNF signaling to facilitate synaptic plasticity. Nat. Neurosci 21. 10.1038/s41593-018-0184-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conti M, Beavo J, 2007. Biochemistry and physiology of cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases: Essential components in cyclic nucleotide signaling. Annu. Rev. Biochem 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.060305.150444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel PB, Walker WH, Habener JF, 1998. CYCLIC AMP SIGNALING AND GENE REGULATION. Annu. Rev. Nutr 18, 353–383. 10.1146/annurev.nutr.18.1.353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Rooij J, Zwartkruis FJT, Verheijen MHG, Cool RH, Nijman SMB, Wittinghofer A, Bos JL, 1998. Epac is a Rap1 guanine-nucleotide-exchange factor directly activated by cyclic AMP. Nature 396, 474–477. 10.1038/24884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demeautis C, Sipieter F, Roul J, Chapuis C, Padilla-Parra S, Riquet FB, Tramier M, 2017. Multiplexing PKA and ERK1&2 kinases FRET biosensors in living cells using single excitation wavelength dual colour FLIM. Sci. Rep 7, 1–14. 10.1038/srep41026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depry C, Allen MD, Zhang J, 2011. Visualization of PKA activity in plasma membrane microdomains. Mol. Biosyst 7, 52–58. 10.1039/c0mb00079e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-García CM, Mongeon R, Lahmann C, Koveal D, Zucker H, Yellen G, 2017. Neuronal Stimulation Triggers Neuronal Glycolysis and Not Lactate Uptake. Cell Metab. 26. 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.06.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Y, Li J, Enterina JR, Shen Y, Zhang I, Tewson PH, Mo GCH, Zhang J, Quinn AM, Hughes TE, Maysinger D, Alford SC, Zhang Y, Campbell RE, 2015. Ratiometric biosensors based on dimerization-dependent fluorescent protein exchange. Nat. Methods 12, 195–198. 10.1038/nmeth.3261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiPilato LM, Cheng X, Zhang J, 2004. Fluorescent indicators of cAMP and Epac activation reveal differential dynamics of cAMP signaling within discrete subcellular compartments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 101, 16513–8. 10.1073/pnas.0405973101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiPilato LM, Zhang J, 2009. The role of membrane microdomains in shaping β2-adrenergic receptor-mediated cAMP dynamics. Mol. Biosyst 5, 832. 10.1039/b823243a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge-Kafka KL, Soughayer J, Pare GC, Carlisle Michel JJ, Langeberg LK, Kapiloff MS, Scott JD, 2005. The protein kinase A anchoring protein mAKAP coordinates two integrated cAMP effector pathways. Nature 437. 10.1038/nature03966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn TA, Feller MB, 2008. Imaging second messenger dynamics in developing neural circuits. Dev. Neurobiol 10.1002/dneu.20619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn TA, Wang CT, Colicos MA, Zaccolo M, DiPilato LM, Zhang J, Tsien RY, Feller MB, 2006. Imaging of cAMP levels and protein kinase A activity reveals that retinal waves drive oscillations in second-messenger cascades. J. Neurosci 26, 12807–12815. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3238-06.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyachok O, Isakov Y, Sågetorp J, Tengholm A, 2006. Oscillations of cyclic AMP in hormone-stimulated insulin-secreting β-cells. Nature 439, 349–352. 10.1038/nature04410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan F, Binkowski BF, Butler BL, Stecha PF, Lewis MK, Wood KV, 2008. Novel Genetically Encoded Biosensors Using Firefly Luciferase. 10.1021/cb8000414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes HB, Riordan S, Nomura T, Remmers CL, Kraniotis S, Marshall JJ, Kukreja L, Vassar R, Contractor A, 2015. Epac2 mediates cAMP-dependent potentiation of neurotransmission in the hippocampus. J. Neurosci 35, 6544–6553. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0314-14.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis SH, Corbin JD, 1994. Structure and Function of Cyclic Nucleotide-Dependent Protein Kinases. Annu. Rev. Physiol 10.1146/annurev.ph.56.030194.001321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]