Abstract

The presence of maternally derived antibodies can interfere with the development of an active antibody response to antigen. Infection of seven passively immunized young calves with a virulent strain of bovine herpesvirus type 1 (BHV-1) was performed to determine whether they could become seronegative after the disappearance of maternal antibodies while latently infected with BHV-1. Four uninfected calves were controls. All calves were monitored serologically for 13 to 18 months. In addition, the development of a cell-mediated immune response was assessed by an in vitro antigen-specific gamma interferon (IFN-γ) production assay. All calves had positive IFN-γ responses as early as 7 days until at least 10 weeks after infection. However, no antibody rise was observed after infection in the three calves with the highest titers of maternal antibodies. One of the three became seronegative by virus neutralization test at 7 months of age like the control animals. This calf presented negative IFN-γ results at the same time and was classified seronegative by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay at around 10 months of age. This calf was latently infected, as proven by virus reexcretion after dexamethasone treatment at the end of the experiment. In conclusion, this study demonstrated that BHV-1-seronegative latent carriers can be obtained experimentally. In addition, the IFN-γ assay was able to discriminate calves possessing only passively acquired antibodies from those latently infected by BHV-1, but it could not detect seronegative latent carriers. The failure to easily detect such animals presents an epidemiological threat for the control of BHV-1 infection.

Bovine herpesvirus type 1 (BHV-1), a member of the Alphaherpesvirinae subfamily, is an important pathogen of cattle that is distributed worldwide. It is responsible for respiratory (infectious bovine rhinotracheitis [IBR]) and genital (infectious pustular vulvovaginitis [IPV]) diseases (18, 41, 45, 54). Like the other alphaherpesviruses, BHV-1 can establish a latent state in ganglionic neurons after infection (1). BHV-1 can be reactivated and reexcreted by means of several stimuli, including transport, parturition, and treatment with glucocorticoids (33, 54). Latency allows the virus to persist, and the introduction of a latently infected carrier into a noninfected herd is the best way to spread the disease (32). Because of latency, controlling this viral infection is difficult to achieve. BHV-1 can also be transmitted through semen from latently infected bulls (4, 16, 48); therefore, artificial insemination (AI) centers of the European Union must be BHV-1 free in order to avoid BHV-1 dissemination within the cattle industry.

Latently infected animals are usually identified by the detection of BHV-1-specific antibodies in their serum. Only serologically negative bulls are allowed to enter selection centers or AI stations (6). In IBR control programs, animals are also serologically tested before entering a BHV-1-free herd. However, especially before entering selection centers, young calves are first tested serologically at the farm of origin at an age when they may still have maternally derived antibodies to BHV-1. In countries with a high seroprevalence to BHV-1, the high seroprevalence could limit the genetic pool of AI stations. On the other hand, retaining seropositive calves and waiting for the decay of maternal antibodies to an undetectable level may be a risk to spread the infection. Indeed, the presence of passively acquired anti-BHV-1 antibodies can inhibit the development of an active antibody response to BHV-1 infection (6, 25). Furthermore, it was suggested that infection in the presence of passive immunity could produce seronegative latent carriers after the disappearance of maternal antibodies (25). Because seronegative latent carriers cannot be serologically detected, the existence of such animals may constitute an epidemiological threat for AI centers, as well as seronegative herds and IBR-free regions or countries.

It is thus essential to determine the epidemiological circumstances which can produce seronegative latent carriers. It is also imperative to develop other diagnostic tests that can detect such latently infected animals. To date, there is no serological test available to distinguish between passively immunized and infected calves. The detection of a cell-mediated immune response could constitute an alternative test. However, there is little information regarding the development of a cell-mediated immune response under passive immunity. Indeed, it has been postulated that priming of memory cells does occur following BHV-1 vaccination while maternal antibodies are present (7, 11, 28), and it was shown by a delayed hypersensitivity test (DHT or skin test) that calves infected under maternal immunity can develop a cell-mediated immune response (6). A practical alternative to DHT could be the development of an in vitro antigen-specific gamma interferon (IFN-γ) production assay. This assay has been successfully used as a diagnostic method for bovine tuberculosis (53) and brucellosis (51), and preliminary studies showed its potential use for BHV-1 (14, 15).

The aim of this study was to determine whether seronegative latent carriers could be produced by infecting young calves protected by maternal immunity with a virulent BHV-1 strain. In addition, the development of a cell-mediated immune response in these calves was assessed by an in vitro specific IFN-γ assay. This assay was also evaluated for its ability to discriminate seropositive calves possessing only maternally acquired antibodies from those latently infected by BHV-1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Virus.

The BHV-1 subtype 1 (BHV-1.1) Iowa strain, characterized as highly virulent (19), was used for experimental infection. This BHV-1 strain was propagated on Madin-Darby bovine kidney (MDBK) cells (ATCC CCL 22) in minimum essential medium (MEM) containing 2% of both penicillin and streptomycin (PS).

Animals.

Eleven calves from two BHV-1-free dairy farms were used. The serological status of these farms had been confirmed through regular serological screening over the past 3 years. All dams were seronegative for BHV-1 when they were tested 4 weeks after calving, and the entire herd was BHV-1 free 1 year later. Calves were removed from their mothers at birth, and they all received 3 liters of a single pool of colostrum containing anti-BHV-1 antibodies within the first 12 h after birth (colostrum bank in Marloie, Belgium). They were transported to the experimental unit at 1 week of age and placed in separate isolation boxes (in facilities with procedures approved for the in vivo use of class 2 zoopathogens). Calves were kept in a nursery isolation facility until 21 weeks postinoculation (PI), and thereafter they were individually moved to an another isolation facility for older animals. All calves were strictly isolated from each other during the course of the study. Moreover, precautions were taken to avoid spread of virus between calves. All persons entering the isolation facilities changed clothes beforehand. Wellington boots, hand gloves, and caps were changed before entering the boxes (each box contained one calf). During infectious periods, after infection and dexamethasone treatment, (single-use) clothes were also changed before handling each calf. Calves were fed a commercial milk substitute until 12 weeks PI and thereafter were fed only hay and concentrates.

Experimental design.

The study was conducted in three phases. In the first (infection) phase, the 11 passively immunized calves were divided in two groups. Four calves (group A) were used as controls to monitor the normal decay of passively derived antibodies, and seven calves (group B) were inoculated intranasally with a total dose of 106 PFU of BHV-1 Iowa strain each (1 ml per nostril). On the day of inoculation (day 0 or week 0), calves were between 11 and 41 days old (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Data on the experimental animals used in this study

| Calf | Serum neutralizing antibody titera at:

|

Age (wk) at inoculation | Length (wk PI) of the monitoring period | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 dayb | Inoculationc | |||

| Group A (control) | ||||

| c1 | 108 | –d | – | 53 |

| c2 | 38 | – | – | 53 |

| c3 | 123 | – | – | 53 |

| c4 | 140 | – | – | 53 |

| Group B (inoculated) | ||||

| i1 | 108 | 45 | 6 | 84 |

| i2 | 161 | 64 | 4 | 57 |

| i3 | 111 | 70 | 2.5 | 57 |

| i4 | 128 | 91 | 2 | 57 |

| i5 | 256 | 166 | 2 | 84 |

| i6 | 166 | 136 | 1.5 | 57 |

| i7 | 152 | 128 | 1.5 | 57 |

BHV-1-neutralizing antibody titers. Results are expressed as ED50 and calculated by the Spearman-Kärber method.

24 h after colostrum uptake.

Intranasal inoculation with BHV-1 virulent Iowa strain.

–, not inoculated.

In the second (monitoring) phase of the study, control and inoculated calves were monitored for 53 and 57 weeks, respectively, except for two inoculated calves (calves i1 and i5) which were kept for 6 months longer (84 weeks), because they possessed relatively low BHV-1 antibody titers at 57 weeks PI.

In the third (reactivation) phase, at the end of the observation period, all calves were treated with dexamethasone (Fortecortine; Bayer) at 0.1 mg/kg of body weight intravenously for 3 to 5 consecutive days in order to demonstrate latent BHV-1 infection by virus reactivation and reexcretion. Control calves received dexamethasone treatment for 5 consecutive days (33) to confirm their BHV-1-free status.

Animal care and experimental procedures were performed in accordance with the Belgian law (A.R. 14/11/93) implementing the European council directive number 86/609/ECC of 24 November 1986.

Clinical observation.

Following viral inoculation and after experimental reactivation, clinical observations and rectal temperatures were recorded daily for 21 days. Between these two phases, animals were observed daily and all events were recorded in a farm book.

Sampling procedure.

Blood samples from each animal were taken 1 day after colostrum uptake, on the day of inoculation, and then weekly by jugular venipuncture to monitor the antibody level. Sera obtained after centrifugation were stored at −20°C until analyzed. Blood samples were also collected in sodium-heparin tubes for in vitro BHV-1 IFN-γ-specific production assays, weekly until 6 weeks PI, at 8 and 10 weeks PI, and then periodically (every 4 to 6 weeks) until the end of the observation period. Heparinized blood samples were treated in the laboratory within 6 h for whole-blood antigenic stimulation.

Nasal secretions were collected by nasal swabbing and stored in 1 ml of MEM with 2% PS. Swabs were weighed before and after sampling. Within 2 h of sampling, the swabs were mixed to disperse aggregated mucus and then frozen at −70°C until used. Nasal swabs were taken daily from each animal for 15 days to monitor virus excretion after inoculation and virus reexcretion after the first day of dexamethasone treatment. Between these two periods, nasal swabs were taken twice a week to detect any virus reexcretion, which can occur after putative spontaneous viral reactivation.

Serological tests.

The presence of BHV-1 antibodies in serum was detected by virus neutralization (VN) test and by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

(i) VN test.

A 24-h VN test was performed by the method of Bitsch (5) modified for the microtitration system. Before testing, serum samples were heated at 56°C for 30 min. Serial twofold dilutions of serum in MEM with 2% PS were mixed with an equal volume of culture medium containing BHV-1 Iowa strain. The final titer of the virus was approximately 125 50% tissue culture infective doses (TCID50) per 50 μl of mixture. After a 24-h incubation at 37°C in a CO2 incubator, each serum sample and virus mixture was added to four wells (50 μl per well) of MDBK cells cultured in microtiter plates. Plates were examined daily for cytopathic effects, and cells were fixed and stained with a hydro-alcoholic solution of crystal violet after a 5-day incubation period. The BHV-1 neutralizing titers were calculated as the initial dilution of serum which would neutralize the cytopathic effect in 50% of the wells (50% effective dose [ED50]), calculated by the Spearman-Kärber method (44). Geometric mean titers (GMT) were calculated for comparison between groups.

(ii) ELISA.

The presence of antibody against BHV-1 in serum was also monitored by a commercially available ELISA (SERELISA IBR/IPV antibody Bi Indirect; Synbiotics). The antibody level for a given serum sample was expressed as the difference in the optical density (ΔOD) obtained with positive and control antigens. All samples were tested on the same day with the same batch, except for the last blood samples of calves i1 and i5 (from 78 to 88 weeks PI) which were analyzed with another batch.

(iii) Serological reference tests.

Samples with negative results were also tested at the Veterinary and Agrochemical Research center (VAR center, Brussels, Belgium) by the reference serological tests in use in Belgium, namely, a blocking ELISA with BHV-1-specific polyclonal antibodies and a 24-h VN test. These tests were evaluated in two European comparative studies (23, 34) and are in use to test bulls in selection and AI centers.

In vitro BHV-1-specific IFN-γ assay. (i) Whole-blood antigenic stimulation.

In vitro stimulation of heparinized blood samples was performed by the method of Godfroid et al. (14, 15). Each blood sample was tested under four different conditions: three negative controls (phosphate-buffered saline [PBS], cell culture medium, and control cell antigen), and one condition with an heat-inactivated BHV-1 antigen. The cultures were incubated for 18 to 24 h at 37°C in a CO2 incubator. Supernatants were then harvested and stored at −20°C until they were assayed for bovine IFN-γ content by ELISA.

(ii) Anti-bovine interferon MAbs.

The monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) 5D10 and 6C3 were used for the IFN-γ ELISA (52). These MAbs are currently available in a commercial kit (IFN-γ Bovine EASIA; BIOSOURCE Europe S.A.).

(iii) ELISA procedure.

The procedure used to measure the IFN-γ levels in plasma harvested from stimulated whole blood was based on the method of Weynants et al. (52). Microtiter plates (certified MaxiSorb [Nunc]) were coated overnight at 37°C with 150 μl per well of a PBS solution containing 3% bovine serum albumin and 0.1% (vol/vol) Tween 80. After each incubation step, plates were washed five times with NaCl (0.9% [wt/vol]) containing 0.01% (vol/vol) Tween 80. Fifty microliters of each plasma sample was added to the wells and incubated for 1 h at room temperature (RT). Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-bovine IFN-γ MAb 6C3 was then added for 1 h at RT. Peroxidase activity was revealed by adding 100 μl of tetramethylbenzidine chromogen substrate solution for 30 min at RT. The color development was stopped by adding 25 μl of 2 N H2SO4 per well, and absorbance was read at 450 and 630 nm in a microplate reader (MIOS; Merck).

The results were expressed as stimulation indices (SI) using the following formula: OD of culture with BHV-1 antigen divided by OD of culture with control cells antigen. A culture was considered to produce a significant level of IFN-γ when the SI was equal to or greater than the mean plus 3 standard deviations (SD) of the SI obtained for control animals.

Virus isolation and titration.

The presence of BHV-1 in nasal swabs was detected and titrated by plaque assay on MDBK cells cultured in 24- and 96-well microtiter plates by the method of Lemaire et al. (26). The virus titer was expressed in PFU/100 mg of nasal secretions.

DNA isolation and restriction endonuclease analysis.

The identity of inoculated and reexcreted virus after its reactivation was examined by DNA restriction endonuclease analysis with HindIII and PstI enzymes on the viruses isolated from the seven inoculated calves 7 days after dexamethasone treatment. DNA isolation and restriction endonuclease analysis were performed by the method of Lemaire et al. (26).

Statistical evaluation.

The Student t test was performed when comparison between groups was needed.

RESULTS

Clinical monitoring.

After inoculation, three of seven infected calves (calves i2, i3, and i7) showed a slight fever (39.5 to 40°C) on day 5 PI. Slight nasal discharge and slight apathy were observed in two of these calves (i3 and i7). Lesions in the nasal mucosa were observed in almost all the calves between days 3 to 10 PI. They were less abundant in calves i6 and i7 and were not found in calf i5 which failed to exhibit any clinical symptoms.

Until the dexamethasone treatment at the end of the observation period, three events occurred which could be considered putative reactivation stimuli: a surgical operation on calf i5 at 10 weeks PI for an umbilical hernia; weaning at 12 weeks PI; and individual transport (over a distance of 25 m) at 21 weeks PI from the nursery isolation facility to another isolation facility for older animals, after which an anterior lameness was observed in calf i7. Control calves remained in good health during the whole observation period.

At the end of the observation period, all calves were subjected to a 3- or 5-day dexamethasone treatment. Profuse nasal discharge and lesions in the nasal mucosa were recorded in all inoculated calves between days 5 to 15 after the first dexamethasone injection. Severe and abundant lesions in the nasal mucosa were observed in all inoculated calves except calf i7. An increase in rectal temperature was recorded for a short period (days 5 through 9) in all inoculated calves, and two calves (i2 and i6) experienced very high rectal temperatures (>40°C).

Serological monitoring.

All 11 calves had passively acquired antibodies to BHV-1 24 h after colostrum feeding (Table 1). The VN antibody GMT were 91 and 148 ED50 in control and inoculated calves, respectively, which were not significantly different. Control calf c2 initially had a low VN titer.

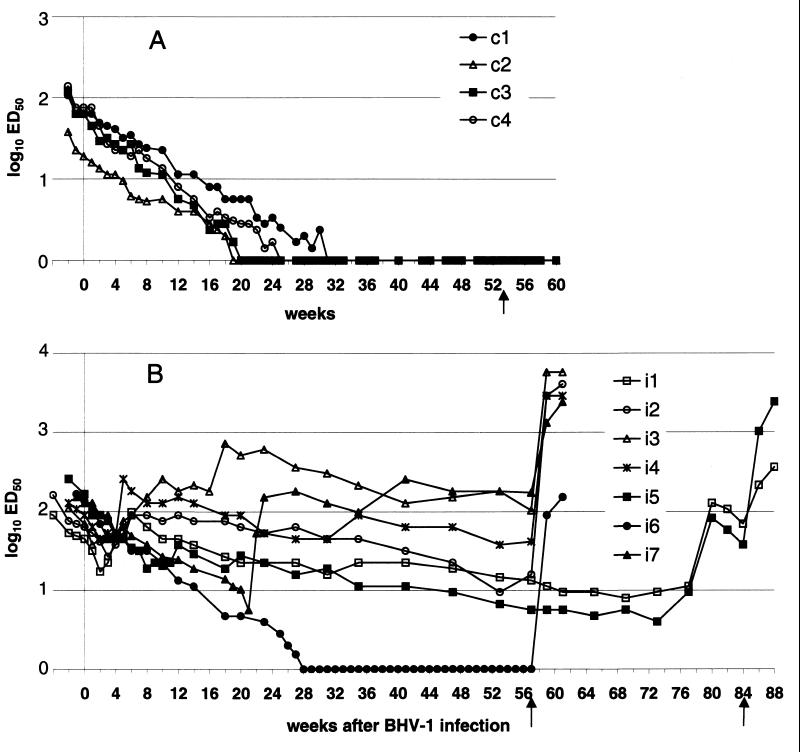

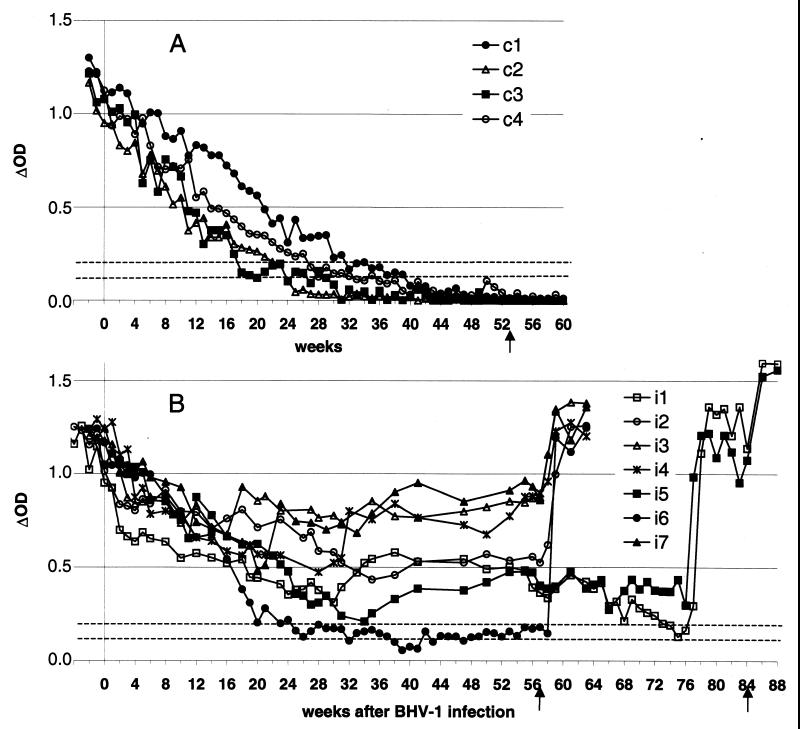

In the four control calves, the VN antibody titers decreased progressively and reached undetectable levels between 5 and 8 months of age (Fig. 1A and Table 2). By ELISA, on the other hand, they became seronegative to BHV-1 5 to 11 weeks later, between 6 and 10 months of age (Fig. 2A and Table 2). All control calves remained seronegative by VN test and ELISA after dexamethasone treatment (Fig. 1A and 2A).

FIG. 1.

Kinetics of BHV-1-neutralizing antibody levels in passively immunized calves obtained with the 24-h VN test. The results for four control calves (A) and seven BHV-1-infected calves (B) are shown. Titers are expressed as log ED50 calculated by the Spearman-Kärber method. The arrows indicate the dexamethasone treatments.

TABLE 2.

Age when maternally immunized calves became seronegative to BHV-1 and BHV-1-neutralizing antibody half-lives

| Calf | Age (wk)

|

Antibody half-life (days) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| VN | ELISA | ||

| Control | |||

| c1 | 33 | 43 | 38 |

| c2 | 21 | 26 | 36 |

| c3 | 22 | 32 | 26 |

| c4 | 27 | 38 | 30 |

| Inoculateda | |||

| i5 | –b | – | 24c |

| i6 | 29.5 | 39.5 | 31 |

| i7 | – | – | 37c |

The three inoculated calves (subgroup 2) which did not show any antibody response to BHV-1 following the infection under passive immunity.

–, never became seronegative against BHV-1.

For calves i5 and i7, the antibody half-lives were calculated with the data obtained up to 11 and 21 weeks after infection (13 and 22.5 weeks of age), respectively.

FIG. 2.

Kinetics of anti-BHV-1 antibody levels in passively immunized calves obtained by the commercially available ELISA. The results for four control calves (A) and seven BHV-1-infected calves (B) are shown. The results are expressed as ΔOD (difference in optical density between positive and control antigens). The broken horizontal lines indicate the cutoff values, with the upper line representing the positive limit and the lower line representing the negative limit (in between the two lines, results are inconclusive). The arrows indicate the dexamethasone treatments.

On the day of inoculation, inoculated calves could be separated into two subgroups on the basis of their VN maternal antibody levels: subgroup 1 (calves i1, i2, i3, and i4) with lower VN titers and subgroup 2 (calves i5, i6, and i7) with higher VN titers (Table 1). The VN antibody GMT for subgroup 1 was 65 ED50 compared to that of subgroup 2, which was significantly higher at 142 ED50 (P < 0.05).

After inoculation (first phase of the study), an increase in VN antibody level could be observed between 4 and 6 weeks PI in calves of the first subgroup only (Fig. 1B). By ELISA, a small increase in the antibody level was observed in only one of these calves (calf i2) from 5 to 9 weeks PI. However, in the other three calves (i1, i3, and i4) of this first subgroup, a slowdown in the decay curve of antibody levels could be observed in the same period (Fig. 2B and Table 3). The antibody levels of the second subgroup (calves i5, i6, and i7) decreased continuously in the same way as the control calves both by the VN test (Fig. 1) and by ELISA (Fig. 2).

TABLE 3.

Immune responses in passively immunized calves after BHV-1 infection and during a monitoring period of 57 to 84 weeks PI (calves i1 and i5)

| Calf | Eventc | Time (wk PI) when developmenta or increasesb of the immune response were observed by:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VN test | ELISA | IFN-γ assay | ||

| i1 | Inoculation | 4 | (5)d | 1 |

| Undetermined | (31–35) | 31–33 | NIe | |

| Undetermined | 77 | 77 | 77 | |

| i2 | Inoculation | 6 | 5–9 | 1 |

| Undetermined | –f | 35–38 | 31 | |

| i3 | Inoculation | 5 | (5–6) | 1 |

| “Weaning” | 16–18 | 17 | 18–23 | |

| i4 | Inoculation | 5 | (6–8) | 2 |

| Undetermined | 31–35 | 32 | ∼g | |

| i5 | Inoculation | – | – | 1 |

| “Operation” | 12 | 12 | ∼ | |

| Undetermined | – | 36 | ∼ | |

| Undetermined | 77 | 77 | 77 | |

| i6 | Inoculation | – | – | 1 |

| i7 | Inoculation | – | – | 1 |

| “Lameness” | 22 | 22 | 18–23 | |

| Undetermined | 35–38 | 35 | ∼ | |

After BHV-1 intranasal inoculation (first phase of the study).

During the monitoring period (second phase of the study).

In addition to the inoculation event, events which tentatively could be related with an increase in the immune response (shown in quotation marks) are also indicated.

Values are shown in parentheses when no clear increase but a slowdown in the decrease in antibody level was observed.

NI, noninterpretable SI.

–, no increase could be observed.

∼, no increase but positive result (SI > 2.0).

During the second phase of the study (observation period), the evolution of anti-BHV-1 antibody levels obtained by VN and ELISA were similar and are depicted in Fig. 1B and 2B, respectively. The antibody level declined very regularly in only one inoculated calf (calf i6). During the monitoring period, the other six inoculated calves showed one or more increases in their antibody levels and all increases observed by VN test were confirmed by ELISA (Table 3).

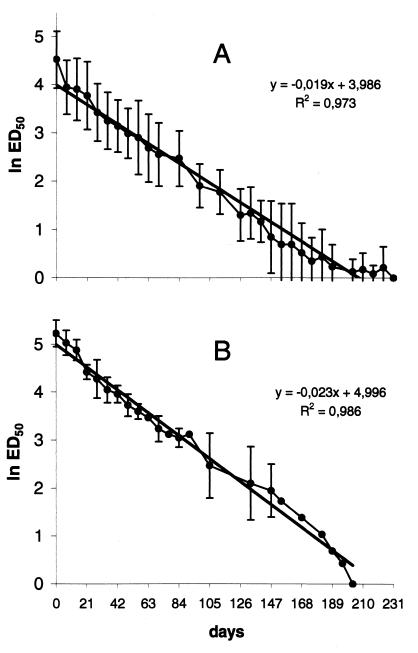

In control animals, the mean (±SD) half-life of colostrally conferred antibody titers to BHV-1, estimated by regression analysis, was 33 (±6) days (Table 2). In BHV-1-infected calves, the half-lives of VN antibody to BHV-1 were also calculated in subgroup 2, for calf i6 with all the serological data and for calves i5 and i7 with the data observed during their antibody decay up to PI weeks 11 and 21, respectively. The mean (±SD) half-life was 31 (±7) days (Table 2). There was no significant difference between these two groups (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Comparison of the decay of BHV-1-neutralizing antibodies in control calves (A) and in the experimentally infected calves i5, i6, and i7 (B). The values are geometric means ± SD. All serological data were used for calf i6, and data up to 11 and 21 weeks PI (13 and 22.5 weeks of age) were used for calves i5 and i7, respectively. Titers are expressed as 1n ED50 calculated by the Spearman-Kärber method.

One of the seven inoculated calves (calf i6) exhibited an undetectable VN antibody level at 7 months of age (28 weeks PI), like the control calves (Table 2). This calf remained negative by the VN test for 7 months until dexamethasone treatment (at week 57 PI). These negative results were confirmed with the reference VN test. The ELISA antibody level of calf i6 decreased at the same rate as that of the controls until 41 weeks PI but thereafter did not decline down to an undetectable level. However, this very low result in ΔOD was maintained until dexamethasone treatment. The ELISA results of calf i6 were classified as inconclusive from week 25 PI on and as negative on weeks 38, 39, 40, 41, and 43 PI (at about 10 months of age). Some inconclusive results were also obtained by ELISA for calf i1 from 74 to 76 weeks PI. With the blocking ELISA used as the reference test, calf i6 was seronegative from PI week 41 to 53.

Within 2 weeks after dexamethasone treatment (third phase of the study) performed either at 57 weeks PI for 5 calves (i2, i3, i4, i6, and i7) or at 84 weeks PI for two calves (i1 and i5), all calves presented a significant rise of antibodies by both serological tests. Calves i1 and i5 presented relatively low VN antibody titers (<16 ED50) at 57 weeks PI and therefore were monitored for a longer period.

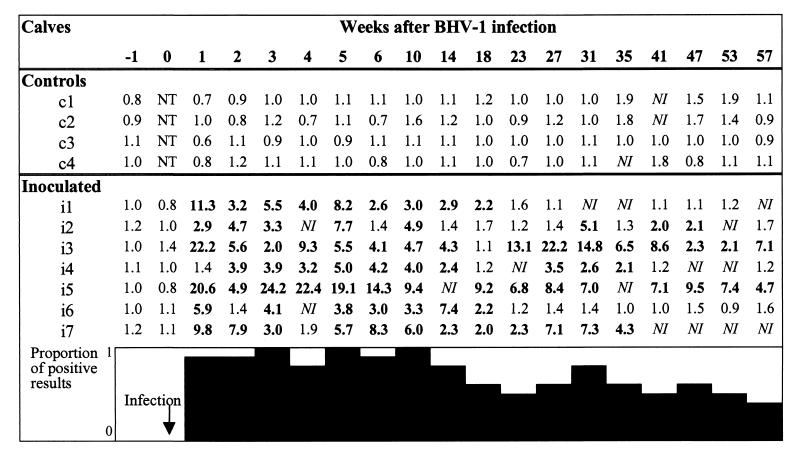

IFN-γ assay.

The results of the BHV-1-specific IFN-γ production assay are shown in Fig. 4. One week before inoculation and on the day of inoculation (week 0), all calves presented a SI close to 1. The cutoff value was calculated from the results obtained from the four control calves during the whole observation period (13 months); the mean (±SD) SI found was 1.1 (±0.3). On this basis, a SI was regarded as positive if it was equal or greater than 2.0 (mean plus 3 SD). Occasionally, the OD value in the three negative cultures were elevated (>0.4). This has also been reported by Godfroid et al. (15), and such samples were considered uninterpretable.

FIG. 4.

Results of IFN-γ assay expressed as SI in passively immunized calves. SI was calculated as follows: OD of culture with BHV-1 antigen/OD of culture with cell control antigen. Positive results are indicated by results greater than 2.0 (in bold type). NT, not tested; NI, not interpretable. The lower box expresses the results after BHV-1 infection in seven passively immunized calves as a diagram.

All seven inoculated calves regularly showed positive SI from 1 or 2 weeks until at least 10 weeks PI. Calf i1 showed negative SI results from 23 to 73 PI weeks (data not shown); however, some noninterpretable results were observed on weeks 31, 35, and 57 (and 61) PI. Calf i6 also showed negative SI from 23 weeks PI until the end of the observation period (57 weeks PI). All negative results were confirmed. For approximately 1 year, although the number of positive results decreased in time, at least 50% of the calves inoculated with BHV-1 were positive by the IFN-γ assay.

Increases in SI could be observed in calf i2 from 31 weeks PI and in calves i3 and i7 between 18 and 23 weeks PI (Table 3 and Fig. 4). In the two calves (i1 and i5) which were kept 6 months longer, an increase in SI was also observed from 77 weeks PI when their antibody level increased (Table 3). All inoculated calves showed an increase in SI after dexamethasone treatment (data not shown).

Virus isolation and titration.

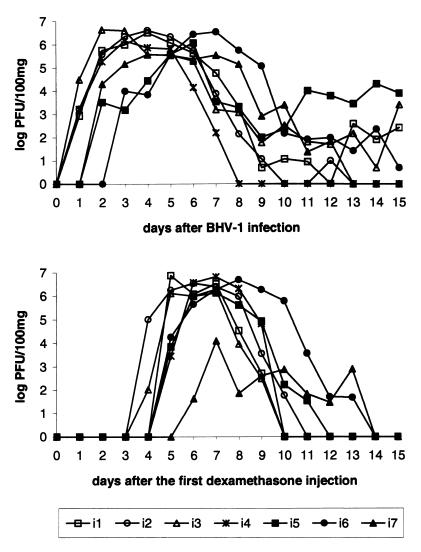

After inoculation, BHV-1 replicated in the nasal mucosa of all calves and was isolated from nasal swabs starting on days 1 to 3 (Fig. 5). The mean (±SD) peak virus titer was 105.8±0.3 PFU/100 mg of nasal secretions on day 5 PI. Calves excreted the virus for a mean (±SD) period of 12 (±3) days. BHV-1 could still be recovered from nasal secretions 15 days after infection in four of the seven calves (i1, i3, i5, and i6). No BHV-1 was isolated from nasal swabs taken from control calves.

FIG. 5.

Excretion and reexcretion of BHV-1 in nasal secretions of seven passively immunized calves after infection with the virulent Iowa strain of BHV-1 and after dexamethasone treatment for 3 days 57 weeks PI (calves i2, i3, i4, i6, and i7) or for 5 days (calves i1 and i5) 84 weeks PI. Titers are expressed as log PFU/100 mg of nasal secretions.

From 21 days PI to the time of dexamethasone treatment, no virus was isolated from nasal swabs taken twice a week from each calf.

After dexamethasone treatment, BHV-1 was isolated in the nasal swabs from all the inoculated calves for 5 to 9 days, starting on days 4 to 6 after the first injection of dexamethasone (Fig. 5). The mean (±SD) peak virus reexcretion titer was 106.1±0.9 PFU/100 mg of nasal secretions 7 days after the first dexamethasone injection. The mean (±SD) number of days of virus shedding was 6.7 (±1.5). All calves presented a similar virus reexcretion pattern, except for calf i7 which started later and shed less virus (peak virus reexcretion titer of 104.1 PFU/100 mg on day 7).

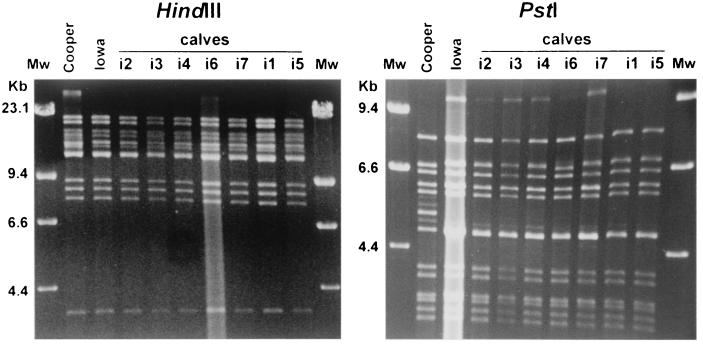

DNA restriction enzyme analysis.

Restriction endonuclease analysis was performed on DNA from viruses isolated 7 days after the first injection of dexamethasone. In comparison, restriction endonuclease analysis was also performed on the inoculated virus (BHV-1 strain Iowa) and the BHV-1.1 reference Cooper strain (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

Restriction endonuclease HindIII and PstI DNA profiles of nasal isolates from the seven experimentally infected calves 7 days after their first dexamethasone injection. DNA profiles of the BHV-1 Iowa challenge strain and the BHV1.1 reference Cooper strain are shown for comparison. The positions of molecular size standards (Mw) (in kilobases) are shown at the sides of the gels.

HindIII restriction endonuclease patterns of the seven DNA samples were similar to the DNA patterns of the inoculated Iowa strain and the BHV-1 reference Cooper strain. The DNA restriction PstI analysis showed that the fragment patterns of the isolates recovered from the seven inoculated calves after viral reactivation were similar to that of the inoculated Iowa strain but different from that of the BHV-1 reference Cooper strain.

DISCUSSION

The presence of passively acquired antibodies did not prevent virus replication and establishment of a latent infection, which is consistent with previous results (6, 25, 26). In addition, for the first time, this study demonstrated that BHV-1-seronegative latent carriers can be obtained experimentally and that passively immunized calves which did not show an antibody response after BHV-1 infection can develop a cell-mediated immune response as detected by the specific IFN-γ assay.

After infection with a virulent BHV-1 strain, passively immunized calves excreted large amounts of virus for a long period. Four of seven calves were still shedding the virus 15 days after inoculation, and this prolonged excretion did not correlate with the BHV-1 antibody titer present at the inoculation. Several researchers have described a prolonged virus shedding in the presence of maternal antibodies after infection with low doses of BHV-1 (26, 41) and pseudorabies virus (PrV) (47) in young calves and piglets, respectively. In the same way, passively administered neutralizing MAbs in calves did not decrease the duration of BHV-1 shedding (27). In addition, no reduction in viral titers was observed after infection with human herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) in passively immunized mice (30). In our study using the natural host, the presence of maternal antibodies in neonates also seemed not to reduce viral replication in the nasal mucosa. On the other hand, there was also no relationship between BHV-1 excretion and clinical symptoms. Calves appeared to be well protected by the presence of colostrally derived antibodies, whereas seronegative calves were severely ill when infected with the BHV-1 Iowa strain (19). Compared to subgroup 1, calves of subgroup 2 with the higher maternal antibody titers presented fewer lesions, if any, in the nasal mucosa. However, apart from a short delay at the beginning for subgroup 2, there was no difference in virus shedding between the two subgroups.

The different levels of preexisting maternal antibodies in calves caused different antibody responses to BHV-1 infection. Four of the seven passively immunized calves (subgroup 1, with lower antibody titers) presented an increase in their antibody level from 4 to 6 weeks PI by the VN test. By ELISA, one of the four calves also presented an increase in the antibody level from 5 to 9 weeks PI, whereas in the three other calves only a slowdown in the antibody curve decay could be observed. As previously shown (26), the presence of high antibody levels in the ELISA used led to a plateau, which most likely made it difficult to show any further increase in antibody levels as observed by the quantitative VN test. The active antibody response to BHV-1 under passive immunity observed in the first subgroup was delayed since after primary infection, the production of antibody to BHV-1 begins 8 to 12 days PI (54). On the other hand, no antibody response could be observed with both serological tests after infection in the three calves which had higher BHV-1 VN antibody titers (subgroup 2) at the time of inoculation. These results are in accordance with those observed in previous studies with BHV-1 (6, 25) or bovine respiratory syncytial virus (21) infection in calves with maternal antibodies. The inhibition of specific antibody production after vaccination with BHV-1 and PrV in calves and piglets, respectively, with high quantities of maternally derived antibodies is also documented (7, 8, 28, 46, 49).

The mean antibody half-life in control calves was 33 days, much higher than the average of 20 days commonly described (7, 28). It could be explained by the higher sensitivity obtained by increasing the incubation period for the VN test from 1 or 2 h to 24 h. Another indication of higher sensitivity is that neutralizing antibodies were found for longer periods, until 5 to 8 months of age instead of 4 to 6 months (20, 28, 41). For the three inoculated calves of subgroup 2, the BHV-1 antibody level steadily declined at the same rate as in control calves with a similar mean antibody half-life of 31 days.

Nevertheless, all inoculated calves developed a cell-mediated immune response as detected by the specific IFN-γ assay as early as 7 to 14 days PI. In addition to the presence of passively acquired specific antibodies, the development of an active cell-mediated immune response may also have contributed to the clinical protection. As shown for bovine tuberculosis and brucellosis (51, 53), the in vitro IFN-γ assay would appear to be a rapid convenient alternative to the DHT which is performed in vivo and carries the risk of BHV-1 seroconversion in tested animals (43). This test appears to be a good complementary method to the serological diagnostic protocols. It was able to detect BHV-1-infected animals very early after infection. A positive response in the IFN-γ assay was also demonstrated in the absence of an antibody response when calves are infected under high levels of maternal antibodies. Furthermore, the duration of the positive IFN-γ response was determined, and it was shown that it lasted for at least 10 weeks PI. However, the detection of positive results appeared to decrease with time after infection. Rouse and Babiuk (36) described that in a lymphocyte proliferation assay, lymphocytes sensitized to BHV-1 appear early PI (5 days) but decline to low levels by day 19 PI. On the other hand, the SI as detected in lymphocyte proliferation assays in the presence of BHV-1 antigen is highly variable and negative and positive results for proliferation have been obtained for seropositive cattle by several researchers (9, 29, 37, 50). The T-cell-mediated protective immunity against peripheral reinfection is known to be antigen dependent (24). In this way it can be postulated that persistent cell-mediated immune response can be detected if there is an adequate and persistent antigenic stimulus. Reactivation with antigenic restimulation could in that manner explain the increases observed in SI during the second phase of the study (until dexamethasone treatment) in all calves, but one (calf i6).

During the second phase of the study, almost all calves (except calf i6) most likely experienced one or more spontaneous virus reactivation events as indicated by increases in SI correlated with antibody increases (Table 3). Irregular antibody increases were observed by both serological tests, and it was shown that all increases in antibody titers observed by the VN test were confirmed by ELISA and were also frequently confirmed either by increases in the in vitro BHV-1-specific IFN-γ production assay or by maintaining a positive SI result. In latently infected animals, antibody titers can fluctuate considerably with one or more peaks, suggesting anamnestic responses to viral reactivation (39). These antibody increases most likely allow a long persistence of BHV-1 antibodies (10). The increase of the specific immune response may be the only detectable consequence of viral reactivation (42) and could explain why no virus was isolated in nasal swabs taken twice a week in this study. Increases in antibody levels occurred following stress stimuli, like surgical operation, weaning, moving, and after two unknown events in the end and beginning of a summer period (around 32 and 77 weeks PI). One likely explanation in these cases is the warm temperature leading to higher serum corticosteroid concentrations (40).

There was no direct link between the presence or absence of an antibody response and latency. All inoculated calves became latently infected as proved by BHV-1 reexcretion after dexamethasone treatment at the end of the observation period (third phase of the study). Although clinical symptoms during virus reexcretion are usually mild or absent (41), typical signs of BHV-1 infection were observed, especially in animals with lower antibody levels (calves i2 and i6) at time of experimental reactivation, as previously observed with the virulent Iowa BHV-1 strain (25). The identity of the inoculated and reexcreted virus by each calf was confirmed by DNA restriction endonuclease analysis. No virus was isolated from control calves after dexamethasone treatment, confirming that no concurrent infection occurred during the experiment.

The existence of seronegative latent carriers was suspected in previous studies where some infected animals possessed only residual antibodies, if any (2, 3, 10, 13, 17, 31, 38, 39, 55). In this study, one calf (calf i6) of the three inoculated calves which did not show an antibody response to BHV-1 infection (subgroup 2) became seronegative by the VN test at 7 months of age like control animals. Calf i6 remained seronegative for 7 months, until dexamethasone treatment. These negative results were confirmed with the reference VN test in use at the VAR center. As already mentioned, this animal was latently infected and reexcreted the virus in large amounts after dexamethasone treatment. Although it developed an active cell-mediated immune response after infection, the IFN-γ assay results were negative from week 23 PI until dexamethasone treatment (week 57 PI). By ELISA, the antibody curve did not decline down to an undetectable level as for the control calves, but this calf was clearly classified seronegative on five different weeks at around 10 months of age (these results were confirmed from week 41 PI on with the reference blocking ELISA test). For control animals, the time when they became seronegative by ELISA was also delayed for about 2 months compared to the results of VN test. This confirms that the indirect ELISA used in this study is highly sensitive (12). Indeed, serological tests should be as sensitive as possible to detect low anti-BHV-1 antibody levels to minimize the risk of nondetection of BHV-1 latent carriers (22). However, improving the test sensitivity will affect the specificity by increasing the number of false-positive animals (44). Currently, there is no means to diagnose a latent infection other than the dexamethasone treatment (through concurrent serological and virological testing) (33), which is difficult to perform routinely. On the other hand, PCR examination of trigeminal ganglion can be applied only to a dead animal (35).

In conclusion, this study experimentally demonstrated the possibility of producing a VN antibody-negative latent carrier, even after infection with a highly virulent BHV-1 strain. In addition, this study demonstrated that the in vitro IFN-γ assay was able to discriminate calves possessing only maternally acquired antibodies from those latently infected with BHV-1. Whether seronegative latent carriers could be more easily obtained after infection with a less virulent strain and whether it could affect the results of IFN-γ assay must be now examined. Nevertheless, under the conditions described, the IFN-γ assay could not detect the seronegative latent carrier, even if it was infected with a virulent BHV-1 strain. The possible existence of seronegative latent carriers will always be a threat for cattle husbandry in BHV-1-free herds, selection stations, and AI centers. In the absence of a test able to easily diagnose those animals, maintaining the IBR-free status of selection stations and AI centers in countries where BHV-1 is prevalent will be possible only by the introduction of BHV-1-seronegative bulls originating from BHV-1-seronegative herds.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Jean-Pierre Georgin, Alex Brichaud, Laurence Nols, John Vilour, Frank Seret, and Sophie Hamande for excellent technical assistance and Jean d'Offay (Oklahoma State University) for critical reading of the manuscript. We also thank Guy Wellemans and Pierre Kerkhofs for the reference tests performed at the Veterinary and Agrochemical Research Center (Belgium). The BHV-1 Iowa strain was kindly provided by Jan T. Van Oirschot (Lelystad, The Netherlands).

This study was supported in part by the “Ministère des classes Moyennes et de l'Agriculture, Administration Recherche et Développement” and the “Fonds de la Recherche Scientifique et Médicale (F.R.S.M.).”

REFERENCES

- 1.Ackermann M, Peterhans E, Wyler R. DNA of bovine herpesvirus type 1 in the trigeminal ganglia of latently infected calves. Am J Vet Res. 1982;43:36–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aguilar-Setién A, Pastoret P-P, Jetteur P, Burtonboy G, Schoenaers F. Excrétion du virus de la rhinotrachéite bovine (IBR, bovid herpesvirus 1) après injection de dexaméthasone, chez un bovin réagissant au test d'hypersensibilité retardée, mais dépourvu d'anticorps neutralisant ce virus. Ann Med Vet. 1979;123:93–101. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allan P J, Dennett D P, Johnson R H. Studies on the effects of infectious bovine rhinotracheitis virus on reproduction in heifers. Aust Vet J. 1975;51:370–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1975.tb15596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bitsch V. Infectious bovine rhinotracheitis virus infection in bulls, with special reference to preputial infection. Appl Microbiol. 1973;26:337–343. doi: 10.1128/am.26.3.337-343.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bitsch V. The P 37/24 modification of the infectious bovine rhinotracheitis virus-serum neutralization test. Acta Vet Scand. 1978;19:497–505. doi: 10.1186/BF03547589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradshaw B J, Edwards S. Antibody isotype responses to experimental infection with bovine herpesvirus 1 in calves with colostrally derived antibody. Vet Microbiol. 1996;53:143–151. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(96)01242-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brar J S, Johnson D W, Muscoplat C C, Shope R E J, Meiske J C. Maternal immunity to infectious bovine rhinotracheitis and bovine viral diarrhea viruses: duration and effect on vaccination in young calves. Am J Vet Res. 1978;39:241–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brockmeier S I, Lager K M, Mengeling W L. Successful pseudorabies vaccination in maternally immune piglets using recombinant vaccinia virus vaccines. Res Vet Sci. 1997;62:281–285. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5288(97)90205-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Denis M, Kaashoek M J, van Oirschot J T, Pastoret P-P, Thiry E. Quantitative assessment of specific CD4+ T lymphocyte proliferative response in bovine herpesvirus 1 immune cattle. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1994;42:275–286. doi: 10.1016/0165-2427(94)90073-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dennett D P, Barasa J O, Johnson R H. Infectious bovine rhinotracheitis virus: studies on the venereal carrier status in range cattle. Res Vet Sci. 1976;20:77–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ellis J A, Hassard L E, Cortese V S, Morley P S. Effects of perinatal vaccination on humoral and cellular immune responses in cows and young calves. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1996;208:393–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Filleton R, Crevat D, Thibault J-C. Proceedings of the 7th International Symposium of Veterinary Laboratory Diagnosticians. Buenos Aires, Argentina: World Association of Veterinary Laboratory Diagnosticians; 1994. Performance of a new diagnostic kit for the detection of antibodies against IBR/IPV in bovine serum; p. 170. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fuchs M, Hubert P, Detterer J, Rziha H-J. Detection of bovine herpesvirus type 1 in blood from naturally infected cattle by using a sensitive PCR that discriminates between wild-type virus and virus lacking glycoprotein E. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2498–2507. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.8.2498-2507.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Godfroid J, Wellemans G, Vanopdenbosch E, Letesson J-J. Infectious bovine rhinotracheitis (IBR) diagnosis based on an in vitro bovine herpesvirus-1 (BHV-1) antigen-specific IFN-γ production. In: Schwyzer M, Ackermann M, editors. Proceedings of the 3rd Congress of the European Society for Veterinary Virology. Immunobiology of viral infections. Lyon, France: European Society for Veterinary Virology, Fondation Marcel Mérieux; 1995. pp. 159–163. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Godfroid J, Czaplicki G, Kerkhofs P, Weynants V, Wellemans G, Thiry E, Letesson J-J. Assessment of the cell-mediated immunity in cattle infection after bovine herpesvirus 4 infection, using an in vitro antigen-specific interferon-gamma assay. Vet Microbiol. 1996;53:133–141. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(96)01241-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guerin G, Harlay T, Guérin B, Thibier M. Distribution of BHV1 in fractions of semen from a naturally infected bull. Theriogenology. 1993;40:997–1002. doi: 10.1016/0093-691x(93)90368-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huck R A, Millar P G, Woods D G. Experimental infection of maiden heifers by the vagina with infectious bovine rhinotracheitis-infectious pustular vulvo-vaginitis virus. An epidemiological study. J Comp Pathol. 1973;83:271–279. doi: 10.1016/0021-9975(73)90052-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones C. Alphaherpesvirus latency: its role in disease and survival of the virus in nature. Adv Virus Res. 1998;51:87–133. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3527(08)60784-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaashoek M J, Straver P H, Van Rooij E M, Quak J, van Oirschot J T. Virulence, immunogenicity and reactivation of seven bovine herpesvirus 1.1 strains: clinical and virological aspects. Vet Rec. 1996;139:416–421. doi: 10.1136/vr.139.17.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kahrs R F. Infectious bovine rhinotracheitis: a review and update. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1977;171:1055–1064. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kimman T G, Westenbrink F, Schreuder B E, Straver P J. Local and systemic antibody response to bovine respiratory syncytial virus infection and reinfection in calves with and without maternal antibodies. J Clin Microbiol. 1987;25:1097–1106. doi: 10.1128/jcm.25.6.1097-1106.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kramps J A, Magdalena J, Quak J, Weerdmeester K, Kaashoek M J, Maris-Veldhuis M A, Rijsewijk F A, Keil G, van Oirschot J T. A simple, specific, and highly sensitive blocking enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for detection of antibodies to bovine herpesvirus 1. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2175–2181. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.9.2175-2181.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kramps J A, Perrin B, Edwards S, van Oirschot J T. A European inter-laboratory trial to evaluate the reliability of serological diagnosis of bovine herpesvirus 1 infections. Vet Microbiol. 1996;53:153–161. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(96)01243-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kündig T M, Bachmann M F, Oehen S, Hoffmann U W, Simard J J L, Kalberer C P, Pircher H, Ohashi P S, Hengartner H, Zinkernagel R M. On the role of antigen in maintaining the cytotoxic T-cell memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:9716–9723. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lemaire M, Meyer G, Ernst E, Vanherreweghe V, Limbourg B, Pastoret P-P, Thiry E. Latent bovine herpesvirus 1 infection in calves protected by colostral immunity. Vet Rec. 1995;137:70–71. doi: 10.1136/vr.137.3.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lemaire M, Schynts F, Meyer G, Thiry E. Antibody response to glycoprotein E after bovine herpesvirus type 1 infection in passively immunised, glycoprotein E-negative calves. Vet Rec. 1999;144:172–176. doi: 10.1136/vr.144.7.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marshall R L, Letchworth G J. Passively administered neutralizing monoclonal antibodies do not protect calves against bovine herpesvirus 1 infection. Vaccine. 1988;6:343–348. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(88)90181-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Menanteau-Horta A M, Ames T R, Johnson D W, Meiske J C. Effect of maternal antibody upon vaccination with infectious bovine rhinotracheitis and bovine virus diarrhea vaccines. Can J Comp Med. 1985;49:10–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller-Edge M, Splitter G. Patterns of bovine T cell-mediated immune responses to bovine herpesvirus 1. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1986;13:301–319. doi: 10.1016/0165-2427(86)90024-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nagashunmugam T, Lubinski J, Wang L, Goldstein L T, Weeks B S, Sundaresan P, Kang E H, Dubin G, Friedman H M. In vivo immune evasion mediated by the herpes simplex virus type 1 immunoglobulin G Fc receptor. J Virol. 1998;72:5351–5359. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.7.5351-5359.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parsonson I M, Snowdon W A. The effect of natural and artificial breeding using bulls infected with, or semen contaminated with, infectious bovine rhinotracheitis virus. Aust Vet J. 1975;51:365–369. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1975.tb15595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pastoret P-P, Thiry E, Brochier B, Derboven G, Vindevogel H. The role of latency in the epizootiology of infectious bovine rhinotracheitis. In: Wittmann G, Gaskell R M, Rziha H-J, editors. Latent herpesvirus infections in veterinary medicine. Boston, Mass: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers; 1984. pp. 221–227. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pastoret P-P, Thiry E, Thomas R. Logical description of bovine herpesvirus type 1 latent infection. J Gen Virol. 1986;67:885–897. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-67-5-885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Perrin B, Bitsch V, Cordioli P, Edwards S, Eloit M, Guerin B, Lenihan P, Perrin M, Ronsholt L, van Oirschot J T. A European comparative study of serological methods for the diagnosis of infectious bovine rhinotracheitis. Rev Sci Technol. 1993;12:969–984. doi: 10.20506/rst.12.3.724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ros C, Belák S. Studies of genetic relationships between bovine, caprine, cervine, and rangiferine alphaherpesviruses and improved molecular methods for virus detection and identification. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1247–1253. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.5.1247-1253.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rouse B T, Babiuk L A. Host defense mechanisms against infectious bovine rhinotracheitis virus: in vitro stimulation of sensitized lymphocytes by virus antigen. Infect Immun. 1974;10:681–687. doi: 10.1128/iai.10.4.681-687.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rutten V P M G, Wentink G H, de Jong W A C, van Exsel A C A, Hensen E J. Determination of BHV-1 specific immune reactivity in naturally infected and vaccinated animals by lymphocyte proliferation assays. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1990;25:259–267. doi: 10.1016/0165-2427(90)90049-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Snowdon W A. Infectious bovine rhinotracheitis and infectious pustular vulvovaginitis in Australian cattle. Aust Vet J. 1964;40:277–288. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Snowdon W A. The IBR-IPV virus: reaction to infection and intermittent recovery of virus from experimentally infected cattle. Aust Vet J. 1965;41:135–142. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stott G H, Wiersma F, Menefee B E, Radwanski F R. Influence of environment on passive immunity in calves. J Dairy Sci. 1976;59:1306–1311. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(76)84360-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Straub O C. Infectious bovine rhinotracheitis. In: Dinter Z, Morein B, editors. Virus infections of ruminants. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier Science Publishers; 1990. pp. 71–108. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thiry E, Brochier B, Hanton G, Derboven G, Pastoret P-P. Réactivation du virus de la rhinotrachéite infectieuse bovine (bovine herpesvirus 1, BHV-1) non accompagnée de réexcrétion de particules infectieuses, après injection de dexaméthasone, chez des bovins préalablement soumis au test d'hypersensibilité retardée au BHV-1. Ann Med Vet. 1983;127:377–381. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thiry E, Wellemans G, Limbourg B, Broes A, Pastoret P-P. Effect of repeated intradermal injections of bovine herpesvirus type 1 antigen on seronegative cattle. Vet Rec. 1992;130:372–375. doi: 10.1136/vr.130.17.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thrusfield M. Serological epidemiology. In: Thrusfield M, editor. Veterinary epidemiology. London, United Kingdom: Butterworths; 1986. pp. 175–186. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tikoo S K, Campos M, Babiuk L A. Bovine herpesvirus 1 (BHV-1): biology, pathogenesis, and control. Adv Virus Res. 1995;45:191–223. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3527(08)60061-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Oirschot J T, De Leeuw P W. Intranasal vaccination of pigs against Aujeszky's disease. 4. Comparison with one or two doses of an inactivated vaccine in pigs with moderate maternal antibody titres. Vet Microbiol. 1985;10:401–408. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(85)90022-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.van Oirschot J T, Daus F, Kimman T G, van Zaane D. Antibody response to glycoprotein I in maternally immune pigs exposed to a mildly virulent strain of pseudorabies virus. Am J Vet Res. 1991;52:1788–1793. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.van Oirschot J T, Straver P J, van Lieshout J A, Quak J, Westenbrink F, van Exsel A C. A subclinical infection of bulls with bovine herpesvirus type 1 at an artificial insemination centre. Vet Rec. 1993;132:32–35. doi: 10.1136/vr.132.2.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weigel R M, Lehman J R, Herr L, Hahn E C. Field trial to evaluate immunogenicity of a glycoprotein I (gE)-deleted pseudorabies virus vaccine after its administration in the presence of maternal antibodies. Am J Vet Res. 1995;56:1155–1162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wentink G H, Rutten V P M G, van Exsel A C A, de Jong W A C, Vleugel H, Hensen E J. Failure of an in vitro lymphoproliferative assay specific for bovine herpes virus type 1 to detect immunised or latently infected animals. Vet Q. 1990;12:175–182. doi: 10.1080/01652176.1990.9694263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weynants V, Godfroid J, Limbourg B, Saegerman C, Letesson J-J. Specific bovine brucellosis diagnosis based on in vitro antigen-specific gamma interferon production. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:706–712. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.3.706-712.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weynants V, Walravens K, Didembourg C, Flanagan P, Godfroid J, Letesson J-J. Quantitative assessment by flow cytometry of T-lymphocytes producing antigen-specific gamma-interferon in Brucella immune cattle. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1998;66:309–320. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2427(98)00205-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wood P R, Corner L A, Plackett P. Development of a simple rapid in vitro cellular assay for bovine tuberculosis based on the production of gamma interferon. Res Vet Sci. 1990;49:46–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wyler R, Engels M, Schwyzer M. Infectious bovine rhinotracheitis/vulvovaginitis (BHV1) In: Wittmann G, editor. Herpesvirus diseases of cattle, horses and pigs. Boston, Mass: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1989. pp. 1–72. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zyambo G C, Dennett D P, Johnson R H. A passive haemagglutination test for the demonstration of antibody to infectious bovine rhinotracheitis-infectious pustular vulvovaginitis virus. 1. Standardisation of test components. Aust Vet J. 1973;49:409–412. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1973.tb06843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]