Abstract

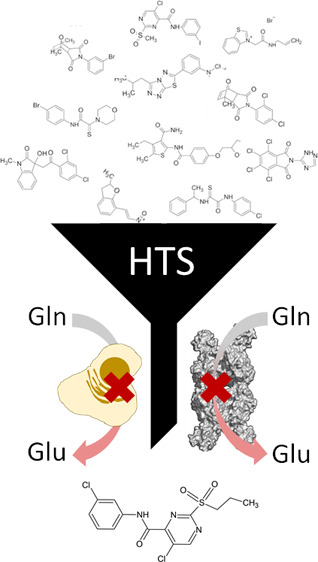

The glutaminase (GLS) enzyme hydrolyzes glutamine into glutamate, an important anaplerotic source for the tricarboxylic acid cycle in rapidly growing cancer cells under the Warburg effect. Glutamine-derived α-ketoglutarate is also an important cofactor of chromatin-modifying enzymes, and through epigenetic changes, it keeps cancer cells in an undifferentiated state. Moreover, glutamate is an important neurotransmitter, and deregulated glutaminase activity in the nervous system underlies several neurological disorders. Given the proven importance of glutaminase for critical diseases, we describe the development of a new coupled enzyme-based fluorescent glutaminase activity assay formatted for 384-well plates for high-throughput screening (HTS) of glutaminase inhibitors. We applied the new methodology to screen a ∼30,000-compound library to search for GLS inhibitors. The HTS assay identified 11 glutaminase inhibitors as hits that were characterized by in silico, biochemical, and glutaminase-based cellular assays. A structure–activity relationship study on the most promising hit (C9) allowed the discovery of a derivative, C9.22, with enhanced in vitro and cellular glutaminase-inhibiting activity. In summary, we discovered a new glutaminase inhibitor with an innovative structural scaffold and described the molecular determinants of its activity.

Keywords: triple-negative breast cancer, glutaminase, cell metabolism, high-throughput screening, enzyme inhibitors

Introduction

Metabolic reprogramming followed by increased glucose and glutamine consumption is a hallmark of cancer1 born from the necessity of tumor cells to maintain high energy rates and biomass production. Metabolic reprogramming also affects the processes of migration and invasion.2

GLS is involved in the hydrolytic deamination of glutamine to glutamate and ammonium, which is a limiting step in the glutamine catabolism process.3 While GLS is under the control of several oncogenes, the paralog GLS2 is controlled by the tumor suppressor p53 in gliomas and hepatocarcinomas; in breast cancer, however, GLS2 was shown to be a tumor-promoting protein.4 Glutamine is an important anaplerotic source in the tricarboxylic acid cycle for many types of tumors.5−7 Glutamine catabolism affects tumor cell proliferation,8,9 redox balance,5,10 the biosynthesis of other nonessential amino acids,11 and, importantly, the maintenance of cancer stem cells;12 thus, it is highly linked to tumor recurrence.13

The GLS gene generates two isoforms by alternative splicing: glutaminase C (GAC) and kidney-type glutaminase (KGA).14 GAC is the most catalytically active isoform and forms long polymers in the presence of the activator inorganic phosphate.15 GLS inhibition has been explored as a therapeutic approach for different types of tumors,16−18 including a subtype of breast cancer called triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC).19

TNBCs, which are characterized as ER–/PR–/HER2– tumors,20 do not respond to hormonal, monoclonal, or tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapies targeted against the progesterone and estrogen receptors or Her2 (or its downstream signaling pathway). TNBCs show a worse prognosis, higher recurrence rate, and greater aggressiveness than other breast cancer subtypes.21,22 Recent studies have shown a relationship between TNBCs and increased glutamine metabolism through GLS.23−27

Some progress has been made in identifying potent and selective inhibitors of GLS. Although a conventional GLS inhibitor known as 6-diazo-5-oxo-l-norleucine (DON)28 has been extensively utilized as a tool to study the physiological roles of GLS, its inherent chemical reactivity coupled with its lack of selectivity and poor potency has hampered its use in establishing the therapeutic benefit of selective GLS inhibition.29 The renewed interest in GLS as a therapeutic target in recent years has prompted efforts to identify new glutaminase inhibitors. Dibenzophenanthridines (derived from a molecule called 968) are being explored as a new class of GLS inhibitors for the treatment of cancer.30,31 Another compound known as bis-2-[5-(phenylacetamido)-1,3,4-thiadiazol-2-yl]ethyl sulfide or BPTES represents a different class of GLS inhibitors and was discovered from a library of bis-thiadiazoles, but the corresponding details were not precisely described.16 Unlike DON, BPTES does not contain any reactive chemical groups or show structural similarity to glutamine or glutamate (hence, it does not bind other enzymes that metabolize glutamine), thereby minimizing toxicological risk. BPTES, however, is highly hydrophobic, and a more soluble truncated version was proposed as an alternative inhibitor with enhanced physicochemical properties.32 In another BPTES-based series, a variety of modified phenylacetyl groups were incorporated into the 5-amino group of the two thiadiazole rings in an attempt to improve binding affinity to the allosteric binding site of GLS.33 CB-839, the most advanced BPTES analog, was described, and its efficacy in TNBC was shown.19 CB-839 is currently in phase I–II clinical trials for several solid and hematopoietic tumors (including TNBC). Another compound, called IPN60090, has also recently entered phase I clinical trials.34

Both BPTES and CB-839 have as a key structural feature: the presence of a lipophilic connecting chain (diethylthio in BPTES and n-butyl in CB-839) between two heterocyclic aromatic moieties. Such chains contribute to both the high lipophilicity and the increased number of rotatable bonds (NRBs) of these compounds. In a new set of BPTES derivatives, decreased NRB, improved ligand efficiency, and lipophilic efficiency were obtained.35,36 Finally, a series of tellurodibenzoic acids as mimics of diphenylarsenic acid (DPAA) were discovered as new GLS inhibitors; however, these compounds may react with cysteine and lysine residues.37 A novel class of thiazolidine-2,4-dione-derived glutaminase inhibitors selective for GLS over GLS2 was also reported.38

Other inhibitors, such as ebselen,39 zaprinast,40 and physapubescin,41 have also been described. Among these compounds, DON, 968, the tellurodibenzoic acids, ebselen, and zaprinast show limitations such as off-target activity, the inability to inhibit activated GLS (968), and reactivity, which might preclude them from becoming successful drugs. BPTES has been extensively studied and modified, and its best analog, CB-839, might already have been discovered.

In this study, we developed a new 384-well format fluorescence-based assay for GLS activity (using the GAC isoform as a target) and conducted an HTS campaign using a diverse collection of ∼30,000 small molecules (DiverSet library, Chembridge) to discover new glutaminase inhibitors. We demonstrate that the fluorescence assay format robustly supports an HTS approach for screening large chemical libraries. Furthermore, we demonstrate that the in vitro enzymatic inhibition of GAC with the best hit, called C9, was recapitulated in cancer cells (TNBC) since it inhibited glutamine uptake and growth dependent on GLS expression. In light of that, we performed a SAR analysis on C9 derivatives and discovered new GLS inhibitors with improved in vitro and in cell inhibition properties. Our findings have confirmed GLS as an anti-TNBC target, provided a method for further investigation of the target and its translation to cancer treatment, and revealed new GLS inhibitors as lead candidates for treating TNBC.

Results and Discussion

Fluorescence-Based Assay Development

We had previously standardized a streamlined glutaminase activity assay in which the glutaminase reaction product, glutamate, is transformed into α-ketoglutarate through the enzyme glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH). In this assay, GDH reduces nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) into NADH, a 340 nm light-absorbing compound.42 However, as it is common for small molecules to absorb light in this range of the spectrum, we decided to add a reaction step in which resazurin is converted to the fluorescent compound resorufin by the enzyme diaphorase using the NADH molecule produced in the previous step (Figure 1A). Resorufin emits fluorescence at 590 nm when excited at 570 nm and is produced in stoichiometric proportion to glutamate.

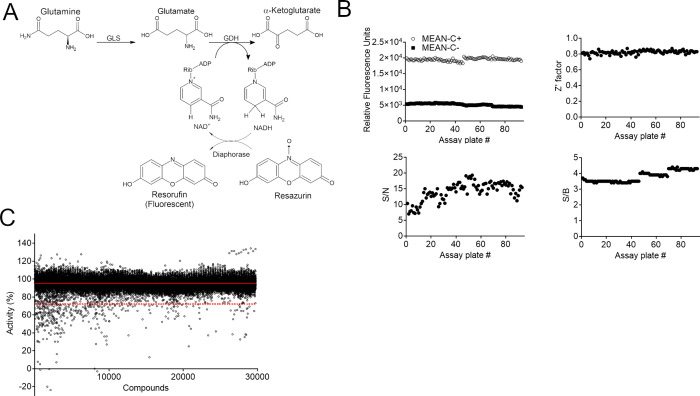

Figure 1.

The HTS campaign was performed with a three-enzyme-based fluorescent assay. (A) Scheme of the three-enzyme-based reaction. GLS converts glutamine in glutamate, which is further converted to α-ketoglutarate by GDH. GDH generates NADH from NAD+, which is used by diaphorase to convert resazurin in resorufin, a fluorescent compound. (B) HTS statistical parameters. Above: relative fluorescent unit values of the positive (1% DMSO) and negative controls (reaction without GAC) (on the left) and the Z′ factor obtained for each plate. Below: signal-to-noise (S/N) and signal-to-background (S/B) values for each plate. (C) HTS campaign showing the calculated percentage of GLS activity on each well. The solid red line indicates average % of activity, and the dashed red line indicates 3 standard deviation (SD) of the average, the established hit limit.

Using the diaphorase-coupled assay, we first confirmed that GAC followed the expected Michaelis–Menten kinetics (Figure S1A). In addition, the kinetic parameters obtained are in agreement with those published for the streamlined GAC-GDH-coupled assay, indicating that the coupled reaction did not impact the enzyme kinetic properties.42 Then, to confirm the directionality and proportionality of the reaction, the enzyme concentration was varied, and initial velocity (V0) was measured. The V0 was proportional to the GAC concentration at all glutamine concentrations tested (∼0.5 to 60 mM), demonstrating that the products generated were under GAC control and that the assay had been correctly standardized (Figure S1B). Finally, the IC50 value of BPTES for GAC was determined using the GAC–GDH–diaphorase-coupled fluorescence assay and compared to that obtained with the GAC–GDH-coupled 340 nm absorbance assay. The calculated IC50 values were consistent (70 and 66 nM for the GAC–GDH–diaphorase and GAC–GDH assays, respectively; Figure S1C) and in agreement with reported values obtained with a different assay.16,19,32

High-Throughput Screening Assay Standardization

Many small organic molecules form submicrometric aggregates at concentrations in the micromolar range in aqueous solution.43 These aggregates have the unusual property of nonspecifically inhibiting their target enzymes, leading to false positive hits in biochemical assays.43−46 This aggregate-based inhibition can be rapidly reversed by the addition of a nonionic detergent, such as Triton X-100, thereby enabling the rapid recovery of enzymatic activity.43 The assay was prepared in the presence and absence of 0.01% Triton, which had no effect on the readouts. A complete overlap of the curves in the presence and absence of the detergent was observed (Figure S1D). Therefore, the screening campaign was performed in the presence of 0.01% Triton to prevent the identification of nonspecific inhibitors as hits. Additionally, kinetic tests were performed in the presence and absence of 2% DMSO. The data indicated that DMSO at 2% did not interfere with the enzyme activity (Figure S1E). Finally, we compared the addition of BPTES to the removal of GAC, leaving only residual GDH activity, as positive controls. We verified that the course of both reactions was comparable. Therefore, we used the GAC-free reaction as the maximum inhibition control for HTS (Figure S1F).

The detection of resorufin fluorescence has been negatively correlated with resazurin concentration.47,48 Resazurin has a maximum absorption wavelength (600 nm) close to the resorufin excitation and emission wavelengths, so high concentrations of the substrate can generate a background fluorescence intensity that impacts the signal-to-noise ratio.48−50 Among the tested conditions, 20 μM resazurin was the concentration that provided both the highest fluorescence signal (RFU) and the best signal-to-noise ratio (Figure S1G). It is important to mention that, under this condition, all substrate was converted to the product. The linear relationship across the range of detection confirmed the reaction proportionality (Figure S1H).

The substrate concentration was fixed at a value close to the Km value for GAC. At this concentration, both competitive and uncompetitive inhibitors could be identified without favoring one inhibition mode over the other. By contrast, noncompetitive inhibitors can bind both the free enzyme and the enzyme–substrate complex with equal or different affinities. In these cases, the observed inhibition is independent of substrate concentration.51,52 Given these optimized parameters, after 3 h of reaction, a Z-prime (Z′) factor of 0.8 and signal/background and signal/noise values of 4.5 and 23.2, respectively, were obtained. These quality measure parameters were reproduced on consecutive days (Figure S1I).

Primary HTS

The primary HTS consisted of 29,681 compounds from the DiverSet kit (Chembridge), screened at a final concentration of 20 μM in the diaphorase-coupled biochemical assay, with a single compound per well. The primary screen was run in three assay iterations of 31 assay plates/run. Each screening plate contained 32 replicates of the positive inhibition control (2% DMSO without GAC) and 32 replicates of the negative inhibition control (2% DMSO with GAC). To monitor assay performance, mean and standard deviation (SD) values from control and assayed wells were used to quantify the signal-to-background (S/B) and signal-to-noise (S/N) ratios and Z and Z′ for each screening plate. The distributions of the RFU for the positive and negative controls, S/B, S/N, and Z′ scores across all plates are shown in Figure 1B.

The average Z′ was 0.8 ± 0.1, and the average S/B and S/N were 3.6 ± 0.3 and 14.1 ± 3.0, respectively, confirming the robustness of the high-throughput assay. Raw screening data (Table S1) for library compounds were normalized relative to the mean of negative control wells (set as 100% activity) and positive control wells (set as 0% activity or 100% inhibition). The average percentage of activity (μ) obtained by HTS was 95%, while the standard deviation (SD) was 7%. The continuous and dashed red lines in Figure 1C represent the mean and cutoff (or hit limit) of ∼3 SD, respectively. Thus, all compounds that decreased enzymatic activity below 70.2% were considered hits. In this case, 320 hits were found, which corresponded to 1.1% of the total compounds.

Cherry Picking, Retesting, and Orthogonal Validation

Three hundred and twenty cherry-picked HTS hits were retested in triplicate (in 384-well plates) at 20 μM using the primary HTS assay format. The Pearson correlation coefficients for plate 1 to plate 2 and plate 1 to plate 3 were 0.92 in both cases, and that for plate 2 to plate 3 was 0.98 (Figure S2A). The average difference in % activity between plates 2 and 3 was 22 ± 16, and for 306 compounds (out of 320), the difference was smaller than 50% of the activity.

To ensure that the hits were inhibiting GAC and not GDH and/or diaphorase, an orthogonal assay without GAC but with GDH and diaphorase in the presence of glutamate was designed. Compounds that simultaneously (i) inhibited the GDH–diaphorase reaction less than 25% (1 standard deviation, red dotted line; Figure 2A) and (ii) presented a % of inhibition in HTS (retest average) minus the % of inhibition of GDH smaller than 20% were selected. The combined cutoff top-listed 100 compounds. In this way, selection of the most potent compounds (19.4 to 105.8% GAC inhibition) was ensured, and molecules that greatly inhibited GAC even though they slightly affected the GDH–diaphorase system were not lost (Table S2). Importantly, 67 out of those 100 hits did not inhibit the coupled GDH–diaphorase reaction (Table S2).

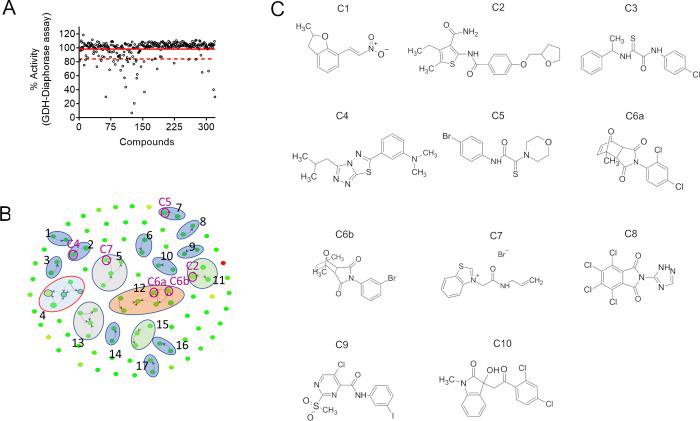

Figure 2.

Orthogonal assay used to eliminate false positives, clusterization of the final hit list, and the 11 further-evaluated compounds. (A) Orthogonal assay (GDH coupled to diaphorase assay) showing the calculated percentage of activity of each well. The solid red line indicates the average % of activity, and the dashed red line indicates 1 standard deviation (SD) of the average. Compounds that inhibited the GDH–diaphorase assay below this limit were considered false positives. (B) Chemical clusterization of the 100 HTS hits. (C) Chemical drawing of the 11 compounds selected for resupplying.

Clusterization and In Silico Analysis

We analyzed the top 100 compounds based on their chemical similarity (using a cutoff of 70% similarity) and found 17 chemical clusters (Figure 2B and Table S1). The clusters contained 2 (G1–G3, G6–G10, G14, and G16–G17), 3 (G11 and G15), 4 (G5 and G13), 5 (G4), and 7 (G12) molecules, for a total of 48 GAC inhibitors. The selected scaffolds included 2-naphthol (G1 and G6), [1,2,4]triazolo[3,4-b][1,3,4]thiadiazole (G2), [1,3]dioxolo[4,5-g]quinolin-6(5H)-one (G4), benzothiazole (G5), 2-thioxoacetamide (G7), dihydrobenzimidazol-2-one (G8), dihydro-2H-indol-2-one (G12), and 6,7,8,9-tetrahydrothieno[2,3-c]isoquinoline (G15), among other derivatives (Table S2).

We then chose a set of 11 compounds based on their potency, little to no inhibition (≤2.4%) of the orthogonal assay, and their availability for resupplying from Chembridge (herein referred to as C1–C6a/b and C7–C11) (Figure 2C). The selected compounds are representatives of some of the clusters, as well as nonclustered compounds. C1–C6a/b and C7–C10 were evaluated for their chemical similarity to 968, BPTES, and CB-839. The Tanimoto index (Table 1), as implemented by Open Babel (path-based FP2), showed an overall low similarity between the 11 molecules and the known inhibitors. Since CB-839 was developed based on BPTES, it exhibited a Tanimoto index of 0.48. A second analytical method (the FragFp index as implemented by Datawarrior53) confirmed the absence of similarity between 968, BPTES, and CB-839 with the 11 selected compounds.

Table 1. Tanimoto Index and FragFp of Similarity of the 11 Resupplied Compounds with 968, BPTES, and CB-839.

| Tanimoto

index |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| path-based

FP2 |

FragP |

||||

| cpd | 968 | BPTES | CB-839 | neighbor similarity FragFp 80% | neighbor |

| C1 | 0.14 | 0.17 | 0.17 | ||

| C2 | 0.22 | 0.21 | 0.29 | ||

| C3 | 0.20 | 0.16 | 0.20 | ||

| C4 | 0.17 | 0.24 | 0.24 | ||

| C5 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.16 | ||

| C6a | 0.27 | 0.13 | 0.21 | 0.91 | C6b |

| C6b | 0.29 | 0.13 | 0.20 | 0.91 | C6a |

| C7 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.15 | ||

| C8 | 0.18 | 0.23 | 0.22 | ||

| C9 | 0.17 | 0.14 | 0.19 | ||

| C10 | 0.28 | 0.20 | 0.27 | ||

| 968 | 1.00 | 0.14 | 0.21 | ||

| BPTES | 0.14 | 1.00 | 0.48 | ||

| CB-839 | 0.21 | 0.48 | 1.00 | ||

Next, the physicochemical profiles and drug likenesses of the molecules were evaluated. They all follow Lipinski’s rules and have good to moderate drug-like characteristics (Tables S3 and S4). Specifically, they all have a clogP smaller than 5, molecular mass less than 500 Da, and a maximum of 2 donors and 5 hydrogen acceptors (Figure S2B). In addition, they all have polar superficial areas (PSAs) smaller than 100 Å2 and fewer than 10 freely rotating bonds, which indicate potential good oral availability characteristics (Figure S2B).

Concentration–Response Biochemical Inhibition

C1–C6a/b and C7–C11 from freshly solubilized dry powders were evaluated in biochemical activity concentration–response studies to confirm the activity of the HTS hits.

Concentration–response assays were performed with the GDH-coupled assay (without diaphorase), and NADH absorbance readings were followed using either GAC or its isoform KGA. The compounds showed IC50 values that ranged from 1 to 85 μM. Six compounds showed inhibitory activity in the low micromolar range (C2–C5, C8, and C10), two compounds exhibited low double-digit micromolar activity (C1 and C7), and one compound (C9) showed high double-digit IC50 value. Two compounds (C6a and C6b) showed low solubility at high concentration (>50 μM) that did not allow the precise assessment of the IC50 values (Figure S3 and Table 2). The assessed IC50 values against GAC and KGA were consistent and agreed with each other (Table 2). The only exception was C9 that showed a 4-fold shift in the IC50s.

Table 2. One-Dose % of Glutaminase Activity Inhibition in the GAC–GDH–Diaphorase and GDH–Diaphorase Fluorescent Assays and the IC50 and Reversibility Calculated with the GAC-GDH Absorbance Assay of the 11 Hit Compounds.

| fluorescent

assay |

absorbance

assay |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cpd | Chembridge ID # | % inhibition GAC–GDH–diaph. | % inhib. GDH–diaph. | IC50 (μM) GAC [95% CI] | IC50 (μM) KGA [95% CI] | reversibility (% recovered activity) |

| C1 | 7992402 | 73 | 1 | 11 [10–12] | 11 [8–14] | 1 |

| C2 | 9155049 | 73 | 2 | 3 [2–4] | 4 [3–4] | 22 |

| C3 | 7956101 | 69 | –10 | 2 [2–3] | 3 [3–4] | 44 |

| C4 | 9125354 | 69 | –1 | 3 [2–3] | 4 [3–4] | 29 |

| C5 | 7952342 | 68 | –8 | 1 [0.9–1.2] | 1.8 [1.6–2.1] | 33 |

| C6a | 6744277 | 60 | –7 | >50 | >50 | 66 |

| C6b | 5603967 | 57 | –3 | >50 | >50 | 56 |

| C7 | 5354303 | 60 | –4 | 43 [37–48] | ∼26 | 99 |

| C8 | 7962214 | 58 | –5 | 6 [5.6–6.3] | 2.6 [2.4–2.7] | 78 |

| C9 | 9007737 | 50 | –7 | 85 [73–99] | 18 [13–25] | 79 |

| C10 | 7951061 | 48 | –3 | 3 [2–5] | 13 [11–15] | 95 |

| BPTES | 0.08 [0.05–0.10] | 0.18 [0.16–0.20] | ||||

Cell-Based Glutaminase Inhibition Assay

TNBCs exhibit high glutaminase expression and low glutamine synthetase expression.54 This expression pattern is associated with high glutamine consumption and exogenous glutamine-dependent growth. Indeed, TNBCs are more sensitive to glutaminase inhibition than the non-TNBC subtypes.19

We used the MDA-MB-231 TNBC cell line as a model to evaluate the concentration response of the 11 compounds and their effects on cell proliferation, with BPTES as a positive control. Moreover, the inhibitory effect of the compounds was evaluated in a non-TNBC cell line, SKBR3 cells. As a nontumor cell control, we used MCF-10A cells and immortalized human mammary epithelial cells (HMECs). MCF-10A is a nontumorigenic epithelial lineage derived from human fibrocystic breast tissue with no signs of terminal differentiation or senescence that has been spontaneously immortalized in culture (no defined mechanism).55 The MCF-10A lineage has a close diploid karyotype and is dependent on exogenous growth factors for proliferation.55 HMECs were immortalized in our laboratory (iHMECs) following transduction with a viral vector for expression of the telomere reverse transcriptase catalytic subunit (TERT).

While iHMECs and SKBR3 cells had low growth rates (data not shown for iHMECs), MDA-MB-231 and MCF-10A cells had comparable growth rates when maintained in their respective culture media (with MCF-10A cells growing slightly faster than MDA-MB-231 cells) (Figure S4A). In addition to their proliferation at compatible rates, both cell types also had comparable sensitivities to glutamine withdrawal (Figure S4A). As expected, SKBR3 cells did not depend on glutamine for growth. Western blot analysis of these cell lines showed that iHMECs and MCF-10A and MDA-MB-231 cells had comparable levels of GAC, while SKBR3 cells had the lowest GAC level (Figure S4B). As expected, the concentration–response assay showed that MDA-MB-231 cells are more sensitive to glutaminase inhibition with BPTES than iHMECs, MCF-10A cells, and SKBR3 cells (IC50 values of 1.4, >50, 12, and 26 μM, respectively) (Figure S4C).

The IC50 values of the 11 compounds in the four cell lines were then determined (Table 3, Figure 3A, and Figure S5). C1 was the most effective in inhibiting the cell proliferation of MDA-MB-231 and SKBR3 tumor cells (IC50 of 1.8 and 2.5 μM, respectively) and also equally inhibited MCF-10A cells (IC50 of 1.8 μM) (Figure 3A and Table 3). Curiously, while the compound at the highest tested concentrations induced cell death in MDA-MB-231 and SKBR3 cells (as suggested by the decreased growth relative to the DMSO control at concentrations of 16–125 μM), the effect was only cytostatic at the same concentrations in MCF-10A cells. The IC50 value in iHMECs was ∼5-fold greater than the value measured in MDA-MB 231 cells.

Table 3. The 11 Compounds’ IC50 over Cell Proliferation of MDA-MB-231, iHMEC, MCF10A, and SKBR3.

| MCF10-A |

iHMEC |

MDA-MB-231 |

SKBR-3 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cpd | IC50 (μM) [95% CI] | R2 | IC50 (μM) [95% CI] | R2 | IC50 (μM) [95% CI] | R2 | IC50 (μM) [95% CI] | R2 |

| C1 | 1.8 [1.7–2.0] | 0.99 | 11 [very wide] | 0.98 | 1.8 [1.7–1.9] | 0.99 | 2.5 [2.2–2.9] | 0.99 |

| C2 | 15 [12–19] | 0.94 | 21 [15–30] | 0.96 | 61 [56–66] | 0.96 | 62 [56–68] | 0.96 |

| C3 | 62 [60–64] | 0.98 | 4.1 [2.7–6.4] | 0.96 | 62 [60–64] | 0.98 | 65 [62–69] | 0.98 |

| C4 | 56 [38–92] | 0.97 | 27 [21–36] | 0.98 | 59 [57–60] | 0.98 | 47 [45–50] | 0.99 |

| C5 | 40 [38–42] | 0.98 | 57 [14–211] | 0.97 | 42 [41–43] | 0.99 | 63 [59–67] | 0.99 |

| C6a | 100 [92–110] | 0.99 | 62 [44–87] | 0.98 | 38 [36–39] | 0.99 | 52 [50–54] | 0.99 |

| C6b | 21 [19–24] | 0.98 | 58 [49–69] | 0.99 | 63 [61–64] | 0.99 | 43 [42–45] | 0.99 |

| C7 | 203 [143–286] | 0.96 | 15 [6–35] | 0.95 | 100 [94–106] | 0.99 | 259 [106–633] | 0.92 |

| C8 | 88 [80–96] | 0.97 | 9 [5–16] | 0.98 | 104 [96–112] | 0.99 | 116 [102–132] | 0.91 |

| C9 | 7 [6–9] | 0.99 | >100 | 7.9 [7.6–8.1] | 0.99 | 9.8 [9.4–10.1] | 0.99 | |

| C10 | 10 [8–13] | 0.97 | 9 [8–10] | 0.99 | 11.7 [11.3–12.1] | 0.99 | 22 [21–23] | 0.99 |

| BPTES | 12 [11–13] | 0.97 | >100 | 1.4 [1.2–1.0] | 0.99 | 26 [17–40] | 0.87 | |

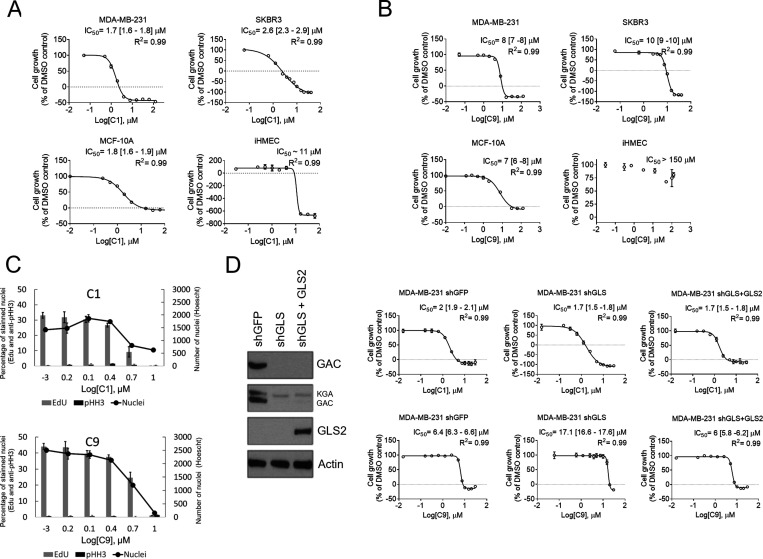

Figure 3.

C1 and C9 effect on tumor and nontumor breast epithelial cell line growth. Growth dose–response assay of C1 (A) and C9 (B) over MDA-MB-231, a TNBC cell line; SKBR3, a non-TNBC cell line; the nontumorigenic MCF-10A cell line; and the hTert-immortalized iHMEC and over MDA-MB-231 shGFP, shGLS, and shGLS expressing GLS2 ectopically subcell lines (D). The value ″0″ was determined based on the number of seeded cells. Doses below the dashed line indicate the concentrations that lead to cell death (the final number of counted cells is smaller than the initial number of cells). IC50 [95% confidence interval] and R2 of the adjusted sigmoidal curve are displayed. (C) Relative number of cells that incorporated EdU and were fluorescently labeled with anti-phosphorylated Ser 25 Histone H3 (anti-pHH3) of MDA-MB-231 treated with C1 (above) or C9 (below). The number of Hoescht-stained nuclei is also displayed. (D, left) Western blot showing GLS knockdown and GLS2 ectopic expression. Graphics in A–D: each bar represents the mean ± SD of n = 4 replicates.

The second most potent compound in the cells was C9. The IC50 values of C9 in MDA-MB-231 and SKBR3 cells were 7.9 and 9.8 μM, respectively. The IC50 value in MCF-10A cells was comparable to that in the cancer cell lines (10 μM); again, as verified for C1, the effect in this cell line was cytostatic for the highest tested concentrations (31–125 μM, Figure 3B). To better understand the inhibitory effects of C1 and C9 on the MDA-MB-231 cells, cell cycle analysis was performed. Cells in the synthesis (S) and mitosis (M) phases were detected by the incorporation of 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) and immunolabeling with anti-phosphorylated histone H3 serine 28 (pHH356), respectively. Increasing concentrations of both C1 and C9 led to a reduction in the percentage of Edu-labeled nuclei; at 10 μM C1 or C9, either no nuclei or 6.5% of nuclei were labeled with Edu, respectively, confirming the cytostatic action of these compounds (Figure 3C). The pHH3 response was not concentration-dependent, and there was no indication of growth arrest at the mitosis phase (Figure 3C).

Since C1 and C9 were the two most potent inhibitors of MDA-MB-231 cell growth, we assessed their on-target action by comparing the IC50 values in a control subcell line (expression of a shRNA for a green fluorescent protein gene, GFP, herein called shGFP) and a subcell line in which GLS had been knocked down with a shRNA (shGLS). A third subcell line was tested, in which shGLS cells ectopically expressed the GLS2 isoenzyme (isoform GAB). Knocking down GLS affected cell growth as already shown (data not shown and ref (4)). BPTES showed an IC50 value in shGLS cells higher than that obtained in shGFP cells (6.5 and 1 μM, respectively); ectopic GLS2 expression maintained the IC50 value at a level (4.9 μM) comparable to the shGLS subcell line since GLS2 is not inhibited by BPTES (Figure S4D). C1 showed similar IC50 values in all three cell variants (between 1.7 and 2 μM), but the control shGFP cells were more sensitive to C9 than the shGLS cells (6.4 and 17.1 μM, respectively) (Figure 3D). When ectopic GLS2 was added to GLS-knockdown cells, the IC50 value of C9 was comparable to that in the control (6 μM) (Figure 3D).

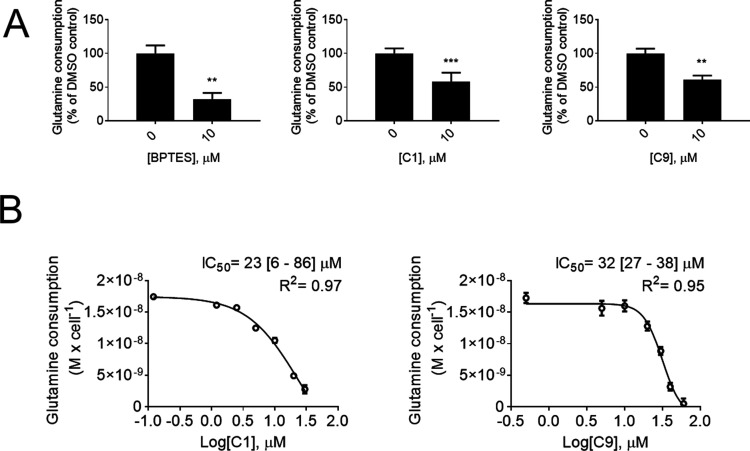

C1 and C9 Decreased Glutamine Uptake

Next, we evaluated whether C1 and C9 would affect the glutamine consumption action of MDA-MB-231 cells. Cells were treated with each compound at 10 μM (BPTES was used as a positive control) for 24 h. C1 and C9 reduced MDA-MB-231 cell glutamine consumption by 39 and 40%, respectively (BPTES decreased glutamine consumption by 76%) (Figure 4A). In parallel, we also used an enzymatic assay to determine the IC50 values for C1 and C9 over glutamine consumption after 6 h of compound incubation (Figure 4B). The values obtained for C1 and C9 were 23 and 32 μM, respectively.

Figure 4.

C1 and C9 effect on MDA-MB-231 glutamine consumption. C1 and C9 decrease MDA-MB-231 cells’ glutamine consumption as measured by BioProfile Basic 4 (A) and by using an enzymatic assay (B). Graphics in A and B: each bar represents the mean ± SD of n = 4 replicates. On A, unpaired t test with Welch’s correction was applied; **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Structure–Activity Relationship Studies of C9 and Its Analogs

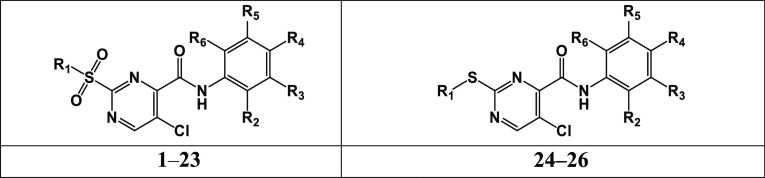

Since C9 is a reversible inhibitor (while C1 is irreversible, Table 2) and showed enhanced on-target activity in cells compared to C1, a diverse series of 25 pyrimidine analogs of C9 were purchased (Chembridge) to investigate the SAR of the 2-sulfonyl-2-thiopyrimidine derivates as a new glutaminase inhibitor. The analogs bear a diverse variety of aryl substituents at the 4-carboxamide group and at the 2-position of the pyrimidine core (Table 4).

Table 4. Structure–Activity Relationships of the 2-Sulfonylpyrimidine/2-Thiopyrimidine Derivatives.

| Chembridge ID# | Cpd | R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | R5 | R6 | IC50 (μM) [95% CI] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9007737 | C9 | Me | H | I | H | H | H | 118 [92–162] |

| 9002388 | C9.1 | Me | H | H | H | H | H | 300 [204–543] |

| 7992875 | C9.2 | Me | Me | H | H | H | H | 81 [58–1009] |

| 7993471 | C9.3 | Me | Cl | H | H | H | H | 53 [45–63] |

| 7997746 | C9.4 | Me | H | Me | H | H | H | 78 [64–99] |

| 9000796 | C9.5 | Me | H | Cl | H | H | H | 45 [37–55] |

| 9331527 | C9.6 | Me | H | CF3 | H | H | H | 67 [52–91] |

| 9002023 | C9.7 | Me | H | H | OCHF2 | H | H | 34 [28–42] |

| 7999377 | C9.8 | Me | H | H | OMe | H | H | 54 [45–66] |

| 7998346 | C9.9 | Me | Me | H | H | Me | H | 102 [89–119] |

| 7994681 | C9.10 | Me | H | Me | Me | H | H | 70 [67–99] |

| 9001867 | C9.11 | Me | Me | H | H | H | Me | 186 [149–164] |

| 7992530 | C9.12 | Me | Cl | H | Cl | H | H | 19 [14–24] |

| 9002556 | C9.13 | Me | 2-naphthyl | 37 [22–34] | ||||

| 7995713 | C9.14 | Et | H | H | H | H | H | 133 [1122–147] |

| 9001771 | C9.15 | Et | F | H | H | H | H | 65 [54−83] |

| 9008307 | C9.16 | Et | H | Me | H | H | H | 79 [67−96] |

| 9005591 | C9.17 | Et | H | Cl | H | H | H | 35 [28−43] |

| 9004507 | C9.18 | Et | H | H | Me | H | H | 36 [28−46] |

| 7997031 | C9.19 | Et | H | H | Et | H | H | 24 [21−29] |

| 7997789 | C9.20 | Et | H | H | I | H | H | 23 [12−41] |

| 7994081 | C9.21 | Pr | H | Me | H | H | H | 59 [50−71] |

| 9005204 | C9.22 | Pr | H | Cl | H | H | H | 20 [17−24] |

| 7987235 | C9.23 | Me | H | I | H | H | H | 40 [25−47] |

| 9033235 | C9.24 | Me | H | Me | H | Me | H | 36 [21−56] |

| 9007737 | C9.25 | Et | H | NO2 | H | H | H | 29 [26−33] |

The aryl substituent of the 2-sulfonylpyrimidine scaffold was initially investigated to determine the structural features required for glutaminase inhibition (compounds C9.1–C9.25, Table 4 and Figure S6). The new batch of C9 showed an IC50 value of 118 μM. The unsubstituted aryl derivative (C9.1) was a poor glutaminase inhibitor (IC50 = 300 μM), while monoaryl-substituted compounds at the 2-, 3-, and 4-positions showed enhanced potency relative to that of C9. Chlorine-substituted derivatives at the 2- and 3-positions (C9.3 and C9.5, IC50 of 53 and 45 μM, respectively) were slightly more potent than the methyl-substituted analogs (C9.2 and C9.4, IC50 of 81 and 78 μM, respectively). However, the presence of a stronger electron-withdrawing group, such as CF3 at the 2-position (C9.6, IC50 of 67 μM), barely improved the inhibitory potency compared with the methyl-substituted analog (C9.4, IC50 of 78 μM). Compounds C9.7 (OCHF2, IC50 = 34 μM) and C9.8 (OCH3, IC50 = 54 μM) were among the most potent monoaryl-substituted derivatives and ∼ 4- and 2-fold more potent than the hit C9. These results indicated that compounds with both electron-withdrawing and electron-donating groups on the aryl moiety were tolerated.

Next, we investigated the impact of di-substitutions on the aryl moiety on the inhibitory activity. Compounds C9.9 (2,5-dimethyl, IC50 = 102 μM) and C9.10 (3,4-dimethyl, IC50 = 80 μM) showed similar or slightly increased potency relative to that of C9, respectively, whereas compound C9.11 (2,6-dimethyl, IC50 = 186 μM) was 1.5-fold less potent than C9. In contrast, compounds C9.12 (2,4-dichloro, IC50 = 19 μM) and C9.13 (2-naphthyl, IC50 = 37 μM) were the most potent compounds in this series, with a 6- and 4-fold potency improvement relative to the hit (Table 4). This result emphasized that electron-withdrawing groups or bulky aryl substituents were important to the inhibitory activity.

To investigate the effect of the 2-sulfonyl group on potency, alkyl derivatives, including ethyl and propyl substituents, were assessed (compounds C9.14–C9.22). In general, the alkyl substituents were tolerated and favorably contributed to the inhibitory activity of this series. For instance, compound C9.14 (IC50 = 37 μM), a 2-ethylsulfonyl derivative, showed increased inhibitory activity compared with that of C9.1 (IC50 = 300 μM), a 2-methylsulfonyl derivative. The same trend was observed for the homologous 2-alkylsulfonyl derivative compounds C9.5 (Me-, IC50 = 45 μM), C9.17 (Et-, IC50 = 35 μM), and C9.22 (Pr-, IC50 = 20 μM), which showed potency enhancement as a function of increasing number of carbon atoms at the 2-sulfonyl group. Finally, to verify the importance of the 2-sulfonyl group on the inhibitory activity, three 2-thiopyrimidine derivatives were tested (compounds C9.23–C9.25, Table 4). Replacement of 2-alkylsulfonyl with the 2-alkylthio group, as in C9 (IC50 = 118 μM) vs C9.23 (IC50 = 40 μM) and C9.9 (IC50 = 102 μM) vs C9.24 (IC50 = 36 μM), led to a 3-fold improvement in potency. Moreover, extension of the 2-alkyl chain and the presence of an electron-withdrawing group, as in C9.25 (IC50 = 29 μM), were favorable for inhibitory activity. Therefore, SAR analyses of these pyrimidine derivatives demonstrated that the nature of the substituents on the 4-aryl carboxamide substituent and the length of the 2-alkylsulfonyl/2-alkylthio chain play pivotal roles in glutaminase inhibition.

C9 Analog Isozymes and Cell Line-Based Selectivity

The top six C9 analogs most potent as glutaminase inhibitors, namely, C9.12, C9.19, C9.20, C9.22, C9.24, and C9.25 (IC50’s ranging from 19 to 36 μM), were selected for inhibitory activity evaluation against the paralog GLS2 to verify the anti-glutaminase selectivity profile of the series. CB-839, a known selective GLS inhibitor, was used as a control. Indeed, CB-839 showed a selectivity index higher than 5.882-fold for GAC (IC50 values of 34 nM for GAC and higher than 200 μM for GLS2, respectively) (Table 5 and Figure S7). All representative C9 analogs showed IC50’s greater than 200 μM against GLS2, except for C9.25 (IC50 GLS2 = 106 μM). Since the differences in GAC IC50s among the C9 analogs were not statistically significant (given the CI of 95%), all tested compounds were considered selective toward GAC with selectivity indexes varying from >1.7 to >10.5 (Table 5).

Table 5. GAC versus GLS2 Selectivity of the Best 2-Sulfonylpyrimidine/2-Thiopyrimidine Derivatives.

| IC50 (μM) [95% CI] |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| cpd | GAC | GLS2 | enzymatic selectivity ratio (IC50 GLS2/IC50 GAC) |

| C9 | 118 [92–162] | >200 | >1.7 |

| C9.12 | 19 [14–24] | >200 | >10.5 |

| C9.19 | 24 [21–29] | >200 | >8.3 |

| C9.20 | 23 [12–41] | >200 | >8.7 |

| C9.22 | 20 [17–24] | >200 | >10 |

| C9.24 | 36 [21–56] | >200 | >5.5 |

| C9.25 | 29 [26–33] | 106 [45–892] | 3.7 |

| CB-839 | 0.034 [0.030–0.039] | >200 | >5882 |

We then measured the selectivity of these analogs toward the more GLS inhibition-sensitive cell line MDA-MB-231 compared to the less sensitive cell line SKBR3. The CB-839 inhibitory potency in MDA-MB-231 cells was 38 nM, while in SKBR3, it was greater than 1 μM (the highest concentration tested) and the cell selectivity ratio was greater than 26-fold (Table 6 and Figure S8). With the new resupply, the IC50 values of C9 against MDA-MB-231 and SKBR3 cells were greater than those initially measured (Table 3); importantly, selectivity was maintained (Table 6). The C9.19 and C9.22 analogs were the most potent compounds in MDA-MB-231 cells (IC50’s of 6 and 4 μM, respectively). All tested analogs were slightly more selective toward MDA-MB-231 cells (cell selectivity ranging from 1.4-fold to ∼3.1-fold), except for C9.20 (cell selectivity = 1) (Table 6). Overall, we concluded that C9.22 is the most promising analog for further investigation given its GAC potency, GAC/GLS2 selectivity, and potency and selectivity toward the GLS-sensitive tumor breast cell line MDA-MB-231.

Table 6. MDA-MB-231 versus SKBR3 Selectivity of the Best 2-Sulfonylpyrimidine/2-Thiopyrimidine Derivatives.

| IC50 (μM) [95% CI] |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| cpd | MDA-MB-231 | SKBR3 | cell selectivity ratio (IC50 SKBR3/IC50 MDA-MB-231) |

| C9 | 48 [43–53] | ∼69 | ∼1.4 |

| C9.12 | 17 [15–19] | 23 [22–26] | 1.4 |

| C9.19 | 6 [6–7] | ∼13 | ∼2.2 |

| C9.20 | ∼28 | ∼29 | ∼1.0 |

| C9.22 | 4.2 [4.0–4.4] | ∼13 | ∼3.1 |

| C9.24 | 105 [73–172] | >200 | >1.9 |

| C9.25 | 180 [73–??] | >400 | >2.2 |

| CB-839 | 0.038 [0.031–0.048] | >1 | >26 |

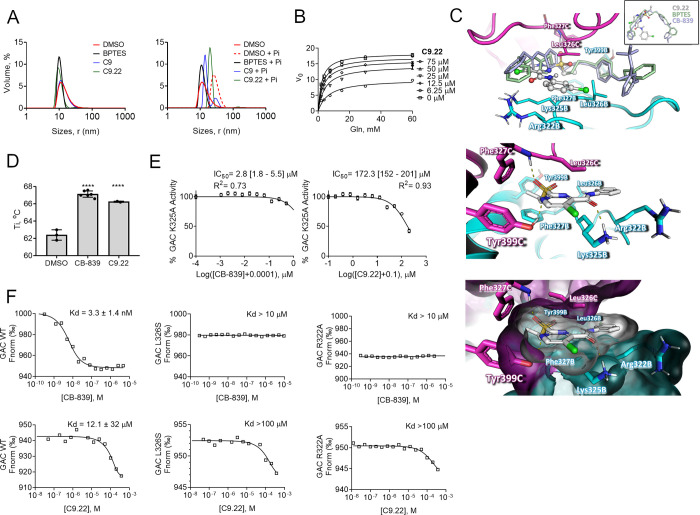

Mechanism of Inhibition and Predicted Binding Mode

We first aimed to verify whether the compound C9.22 would affect GAC activity through a nonspecific aggregation effect. Protein was incubated with the solvent DMSO or the positive control BPTES, C9, or C9.22 at a high concentration (100 μM) for 24 h. After that, we analyzed their dynamic light scattering behavior. We tested two conditions: one condition was a buffered 500 mM NaCl solution, known to generate a 5–6 nm hydrodynamic radius (Rh), with a tetrameric protein,4 and the second condition was 150 mM NaCl and 20 mM Pi, which leads the tetramers to a highly activated polydisperse polymeric arrangement.4 BPTES was shown to disassemble these polymers back to inactive tetramers.4 Interestingly, in 500 mM NaCl, BPTES, C9, and C9.22 maintained the protein in a tetrameric state; BPTES, but not the other compounds, decreased the polydispersity (Figure 5A, on the left). In a 150 mM NaCl and 20 mM Pi solution, as expected, Rh increase up to ∼13 nm. BPTES incubation brought the peak back to 5.4 nm, indicating the tetrameric state, and decreased polydispersity. Curiously, C9 and C9.22 led the protein to adopt an intermediate state between polymers and tetramers (Table 7 and Figure 5A, on the right).

Figure 5.

C9.22 is a noncompetitive inhibitor. (A) Dynamic light scattering assay of the BPTES, C9, and C9.22 compounds incubated for 24 h with purified GAC reveals that the compounds do not aggregate the protein in the solution, keeping GAC at a tetrameric state (on the left). The addition of phosphate to the solution drives protein oligomerization to highly active polymers, a phenomenon that is blocked by BPTES (72); C9 and C9.22 incubation led protein to an intermediate state between the polymers and tetramers (on the right). (B) GAC was incubated with increasing concentrations of C9.22; the nonlinear fitting mixed model of inhibition was applied. (C, above) Superposition of the GAC-C9.22 docking model (performed with PDB ID 4JKT shown as a cartoon) on the crystallographic structure of GAC and BPTES (PDB ID 4JKT, light green, only BPTES is shown) and CB-839 (PDB ID 5HL1, light blue, only CB-839 is shown). Insert: BPTES (light green), CB839 (light blue), and C9.22 (gray, ball-and-stick model) superposed crystallographic coordinates. The GAC structure is indicated as cartoon (middle) and surface (below) models. Key residues involved in inhibitor stabilization are indicated as stick models (subunits B and C are indicated as cyan and magenta, respectively). (D) NanoDSF reveals that both CB-839 and C9.22 increase GAC Ti compared to only DMSO. (E) IC50’s of both CB-839 and C9.22 increase when the K325 residue is mutated to an alanine. (F) Thermophoresis shows that up to 10 μM of CB-839 does not bind GAC L326S and R322A mutants (above). CB-839 calculated Kd was 3.3 nM, but this value is an approximation since the protein was assayed at 80 nM. Both L326S and R322A mutations also decrease C9.22 binding affinity (below). Graphs on A display one representative curve out of three replicates. Graph on B: each point represents the mean ± SD of n = 3 replicates. Graph on C: bars represent the mean ± SD; one-way ANOVA was applied, ****p < 0.0001.

Table 7. Rh Measured by Dynamic Light Scattering of Samples Incubated with Control and the Tested Compounds.

| solution | cpd | size peak (nm)a | volume (%) | polydispersity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 500 mM NaCl | – | 3.9 ± 1.7 | 100 | 44 |

| DMSO | 5.6 ± 3.1 | 100 | 58 | |

| C9 | 5.6 ± 2.8 | 100 | 55 | |

| C9.22 | 4.7 ± 1 | 96 | 111 | |

| BPTES | 4.9 ± 0.8 | 100 | 17 | |

| 150 mM NaCl +20 mM Pi | – | 11.7 ± 4.6 | 100 | 35 |

| DMSO | 12.9 ± 3.8 | 100 | 27 | |

| C9 | 7.4 ± 0.9 | 77 | 19 | |

| C9.22 | 9.8 ± 1.2 | 97 | 12 | |

| BPTES | 5.4 ± 1.1 | 100 | 20 |

The reported values are mode ± standard deviation of one technical replicate representative of three replicates.

We then assessed C9.22 mechanism of inhibition on GAC. In this assay, C9.22 concentrations were fixed at 6.25, 12.5, 25, and 75 μM (1/4-, 1/2-, 1-, and 3-fold the IC50 value) and the GAC inhibition was evaluated in the presence of increasing concentrations of the substrate (Figure 5B). The analysis of the initial velocity (V0) as a function of substrate concentration at increasing concentrations of C9.22 indicated that this compound affected the kinetic constants to lower the apparent value of Vmax and to increase the apparent value of Km (Figure 5B). This is a signature of noncompetitive inhibition in which the inhibitor binds to both the free (E) and the enzyme-substrate complex (ES) forms of the enzyme. In the case of C9.22, the assessed inhibition constants were Ki = 17 ± 5 μM and αKi = 85 ± 59 μM. These findings suggest that C9.22 is a noncompetitive GAC inhibitor with a greater affinity for the free form of the enzyme.57

Since the mechanism of inhibition determined for C9.22 suggested that the binding site lay in a pocket other than the substrate’s binding pocket, we modeled C9.22 in the allosteric BPTES binding site,15 which is exactly the same as for the CB-83958 (Figure 5C, above). The proposed binding mode suggested that the inhibitor established attractive polar and hydrophobic contacts with the GAC binding site residues. In this conformation, the O atom of the sulfonyl group, the N atom of the pyrimidine moiety, and the O atom of the amide group of the inhibitor are in a favorable position to accept the hydrogen bond from the Phe327C (NH group of the amide main chain), Tyr399C (OH group of the phenolic side chain), and Lys325B (NH group of the primary amine side chain) residues, respectively (Figure 5C, middle). Moreover, hydrophobic interactions played important roles in the stabilization of the complex (Figure 5C, bellow). For instance, the propyl substituent of C9.22 is in close contact with the hydrophobic side chains of Phe327B, Phe327C, and Tyr399B; in addition, the 3-Cl-phenyl substituents make attractive van der Waals interactions with the acyclic alkyl groups of Lys325B and Arg322B and the side chains of the symmetric Leu326B and Leu326C (Figure 5C, below). To confirm the C9.22 binding mode, we used two GAC mutants (K325A and R322A) previously generated in our laboratory15 and generated a new one, L326S. First, we used nanoDSF to calculate the Ti inflection temperature of the unfolding transition in the 350 nm/330 nm ratio signal of the GAC WT in the presence of CB-839, C9.22, or the solvent DMSO (control). Both CB-839 and C9.22 increased the Ti of the protein compared to the control, indicating that the compounds bind and stabilize the protein (Figure 5D). Next, since the K325A mutant does not decrease the GAC activity15 (differently from L326S and R322A; data not shown and ref (15), respectively), we calculated the IC50 values of CB-839 and C9.22 over the GAC K325A. As expected, in both cases, the mutation led to an increase in the IC50 values from 5 nM (Figure S6 and Table 4) to 2.8 μM for CB-839 (Figure 5E, left) and from 20 μM (Figure S6 and Table 4) to 172.3 μM (Figure 5E, right), showing that this residue is important for the binding of both compounds. Finally, we used thermophoresis to calculate the dissociation constant (Kd) of CB-839 and C9.22 to the WT protein and the effect of the L326S and R322A mutations on the binding affinity of these compounds. The calculated Kd value for CB-839 was 3.3 ± 1.4 nM; both L326S and R322A mutations abrogated CB-839 binding to GAC (maximum tested concentration was 10 μM) (Figure 5F). The determined Kd value for C9.22 was 12.1 μM for the WT GAC, whereas the Kd values for both the L326S and R322A mutants were greater than 100 μM, thereby confirming that these two residues are crucial for C9.22 binding to GAC (Figure 5F).

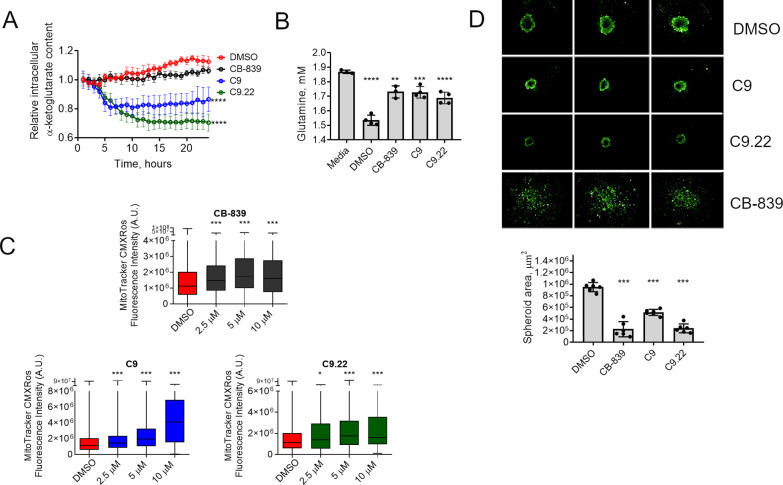

C9.22 Affects GLS Activity in Cells

Finally, we set out to evaluate the effect of C9.22 on glutaminase activity in cells. GLS inhibition in cells is known to decrease glutaminase-derived mitochondrial metabolites, such as 2-oxoglutarate, and increase mitochondrial oxidative stress.4 The evaluated compounds CB-839, C9, and C9.22 decreased intracellular 2-oxoglutarate in a time-dependent manner, showing that they were capable of affecting glutaminase-driven metabolic pathways within the cell (Figure 6A). Likewise, all compounds decreased glutamine consumption from the media (Figure 6B) and increased mitochondrial oxidative stress, as indicated by the increase in fluorescence intensity of the MitoTracker CMXRos probe as the compound concentration increased (Figure 6C). Finally, we verified that C9 and C9.22 decreased the 3D growth of MDA-MB-231 cells (as measured by the spheroid area) compared to the growth with the DMSO control (Figure 6D).

Figure 6.

C9.22 affects glutamine metabolism in cells. (A) An intracellular α-ketoglutarate fluorescent probe was used to determine the relative α-ketoglutarate content within MDA-MB-231 cells incubated with the compounds (or DMSO as negative control) for the indicated time; the signal was measured throughout the assay. (B) Glutamine levels in the media (Media) after incubation of the cells with DMSO, CB-839 (1 μM), C9 (50 μM), or C9.22 (50 μM) for 12 h. (C) Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species increase with GLS inhibition as determined by the increase in the fluorescence of the probe MitoTracker CMXRos. (D) MDA-MB-231 spheroids respond to 14 day treatment with C9 and C9.22 by a decrease in the spheroid area. Representative images of three replicates above (green, calcein fluorescence); spheroid area plot below. Graph on A represents the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of n = 3 biological replicates (each well containing 30–106 cells). Graph on B represents the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of n = 4 replicates. Graph on C represents data collected from 146–18,599 cells. Graph on D represents the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of n = 6 replicates. Statistical significance was assessed by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction tests on A, B, and D; on C, Kruskal–Wallis test was applied; n.s., nonsignificant; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001.

Discussion

Glutaminase is important for the highly proliferative behavior and aggressiveness of cancer cells and a promising target for different types of tumors. In recent years, it has been shown that TNBCs depend on glutamine for growth and survival. Glutaminase is also involved in the gain of invasive traces in other tumor types.7,58,59 Phase I and II clinical trials with the glutaminase inhibitor CB-839 for several solid tumors (including TNBCs) and hematological tumors are being conducted.

In the nervous system, GLS is responsible for the production of intracellular glutamate, a key excitatory neurotransmitter, as a crucial part of the glutamine–glutamate cycle. Moreover, accumulating evidence suggests that glutamate formed by upregulated GLS in activated macrophages and microglia plays a key pathogenic role in inflammatory neurological disorders. Therefore, small-molecule GLS inhibitors may offer therapeutic potential in devastating neurodegenerative diseases, such as HIV-1-associated dementia and multiple sclerosis.60,61

In this work, we developed a three enzyme-based fluorescent assay that was used to screen a diverse library of small molecules as glutaminase inhibitors. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first biochemical assay developed and validated for HTS of glutaminase inhibitors. The HTS assay presented an average Z factor value of 0.74 (Z > 0.5 for all plates) and an average Z′ factor of 0.8. The proximity between the Z and Z′ values indicates the robustness of the assay and the quality of the compound library.62

The average percent activity (μ) obtained in the HTS was 95%, while the standard deviation was 7%. All compounds that decreased enzymatic activity below ∼70% were considered hits. In this case, 320 hits were found, corresponding to ∼1.1% of the total compounds. The hits were than retested in triplicate. When the replicate data were compared, we obtained a high correlation between the data (>0.95). Orthogonal assays (without GAC) were performed to eliminate false positives. This procedure eliminated 27 compounds from the initial list, as they inhibited the GDH–diaphorase system above 24%. Finally, a list of the top 100 more potent compounds was defined. This set of selected hits includes compounds that showed a difference between the % inhibition for the GAC–GDH–diaphorase assay versus the GHD–diaphorase assay greater than ∼19%.

We identified 17 structural clusters (using a cutoff of 70% similarity) among 48 of the top 100 compounds. The selected scaffolds were very diverse, and interestingly, the HTS campaign identified substructures similar to those of known GAC inhibitors, such as ebselen39 (e.g., 1H-indole-2,3-dione in G10 and 1,3-dihydro-2H-indol-2-one in G12) and chelerythrine39 (e.g., 7,8-dihydro[1,3]dioxolo[4,5-g]quinolin-6(5H)-one in G4).39 This observation indicates the consistency and applicability of the standardized HTS method to discover GAC inhibitors.

From the final list of verified hits, we selected 11 compounds as representatives of the 17 clusters that were available for resupply. The criteria used for compound selection included (i) high efficiency (between ∼48 and ∼73% inhibition of GAC activity), (ii) low similarity to known glutaminase inhibitors, and (iii) attractive in silico drug-like and ADME.

Compounds C2, C3, C4, C5, C8, and C10 presented lower IC50 values for GAC-KGA; however, the cellular IC50’s assessed for the non-tumor cell lines iHMECs and MCF-10A cells were smaller than those measured for the cancer cell lines MDA-MB-231 and SKBR3 (with little difference between them, an indication of non-GAC-dependent toxicity). Compound C6a showed IC50 values for GAC and KGA >50 μM (Table 2) but an attractive effect in tumor cells, which makes it another interesting candidate for further development. By contrast, C7 and C6b showed low enzymatic inhibition and no selectivity in the cell lines.

C1 and C9 showed the lowest IC50 values for cell proliferation in the tumor cell lines. Moreover, they were selective for the tumor cells with IC50 values at least ∼10-fold greater than those observed in iHMECs. The IC50’s in MCF-10A cells were similar to the values assessed in the tumor cell lines, but their actions at higher concentrations were more cytostatic than cytotoxic in MCF-10A cells but not MDA-MB-231 or SKBR3 cells. In addition, these compounds inhibited ∼40% of the glutamine consumed by MDA-MB-231 cells. We verified that C9, unlike C1, targeted GAC in MDA-MB-231 cells since the IC50 value obtained in GLS-knockdown cells was greater than that obtained in control cells.

A diverse series of 25 pyrimidine analogs of C9 were investigated to develop the SAR guiding rational design for the next generation of 2-sulfonylpyrimidine derivatives as new GAC inhibitors. The C9 analogs were divided into two subclasses of 2-sulfonyl-2-thiopyrimidine derivates. The analogs bear a diverse variety of aryl substituents at the 4-carboxamide group and at the 2-position of the pyrimidine core, which allowed the identification of the main structural and physicochemical features underlying their glutaminase inhibitory activity. In general, the alkyl substituents at the 2-sulfonyl group (including ethyl and propyl substituents) were tolerated and favorably contributed to the inhibitory activity of the series.

Two compounds presenting ethyl-substituted derivatives at the 1- and 4-positions and propyl and chlorine substituents at the 1- and 3-positions, C9.19 and C9.22, respectively, were the most potent analogs (IC50’s of 24 and 20 μM, respectively) with an approximately 6-fold potency improvement relative to the hit. Moreover, the compounds showed considerable GAC/GLS2 selectivity (>8-fold) and attractive potency and selectivity toward the GLS-sensitive tumor breast cell line MDA-MB-231 (compared to SKBR3). Finally, we were able to confirm that C9.22 did not cause protein aggregation in vitro and slightly decreased the size of highly active polymers formed by GAC in the presence of phosphate. C9.22 is a noncompetitive GAC inhibitor with a greater affinity for the free form of the enzyme. Moreover, C9.22 is cytotoxic to MDA-MB-231 cells (Figure S9). Given these results, we modeled C9.22 in the BPTES/CB839 binding pocket, and by performing mutagenesis, activity assay, nanoDSF, and thermophoresis, we determined interactions important for the inhibitor/glutaminase contact. Altogether, our data show that C9.22 specifically inhibited GAC with a potential mechanism of inhibition akin to that of BPTES and CB-839. C9.22 decreased glutamine metabolism in cells and 3D cell growth, making it an interesting lead molecule worthy of further development.

Methods

Fluorescent Assay of GLS Activity

The primary HTS consisted of 29,681 compounds from the DiverSet kit (Chembridge) screened at a final concentration of 20 μM. For the HTS campaign, three mixtures were made: mix 1 (10× stock) containing 25 nM purified recombinant GAC enzyme (construct Δ1-127) (41), 50 mM Tris-acetate buffer (pH 8.6), 0.01% Triton X-100, 0.2 mM EDTA, 3 mM NAD+, and 28.5 U GDH/mL (Cattle Liver Extraction, Sigma Aldrich, USA); mix 2 (negative control) containing the mix 1 components without glutaminase; and mix 3 (1.14× stock) containing 5.68 mM K2HPO4, 2.12 mM glutamine, 22.72 μM resazurin, and 0.45 U/mL Diaphorase was prepared in a solution of 50 mM Tris-acetate (pH 8.6), 0.2 mM EDTA, and 0.01% Triton X-100. Since the campaign was conducted over 3 consecutive days, batches of the reagents were prepared and frozen; on the day of the assay, aliquots sufficient for the screen of that day were thawed, and the mixture was prepared. The glutaminase samples were centrifuged, and the concentration was reevaluated by detecting UV absorbance at 280 nm. Mix 3 was placed in the bird feeder container of the Cell::Explorer automated screening platform (PerkinElmer). Mix 1 and mix 2 were manually pipetted into a 384-well stock plate (motherboard) as follows: the first two (1st and 2nd) and the last two (23rd and 24th) columns were dedicated to receiving the positive (mix 1, maximum activity) and negative (mix 2, minimal activity) controls, which were intercalated. Columns 3 to 22 received mix 1. Within the platform, the Janus MDT-384 Automated Workstation (PerkinElmer) transferred 22.5 μL of mix 3 to the plate followed by 0.5 μL of the compounds at 1 mM (the plates were configured such that 100% DMSO was placed in columns 1, 2, 23, and 24 and the compounds were placed in the columns in between) followed by 2.5 μL of mix 1 + mix 2 organized in the 384-well motherboard plate. The robotic arm moved the plate to the EnVision Workstation version 1.12 (PerkinElmer) for reading (excitation at 570 nm and emission at 590 nm) after 3 h of incubation. The percent activity (% act.), Z, Z′, S/B (signal/background), and S/N (signal/noise) were determined as follows:

where RFUcomp is the measured relative fluorescence (in relative fluorescence units, RFU) of the wells to which a compound was added; μ and σ are the average and standard deviation of the measured RFU, respectively; and c– and c+ are negative (without glutaminase) and positive controls (DMSO), respectively.

GAC fluorescent kinetic assays were performed in 384-well plates. Serial dilutions of glutamine were prepared by varying the concentration from 60 to 0.47 mM in a buffer consisting of Tris-acetate (pH 8.6), 0.01% Triton, and 0.2 mM EDTA. A 2.5× mixture was prepared in 50 mM Tris-acetate (pH 8.6), 0.01% Triton, 0.2 mM EDTA, 1 U/mL diaphorase, 12.5 mM K2HPO4, 50 μM resazurin, 0.75 mM NAD+, 7.16 U/mL GDH μM, and glutaminase at 3.12, 6.25, and 12.5 nM (final concentrations of 1.25, 2.5, and 5 nM, respectively). The reaction was triggered by the addition of 10 μL of this mixture to 15 μL of a glutamine solution. The first 20 readings were used to calculate the slope (initial velocity, V0) of the reaction.

Orthogonal GDH–Diaphorase Assay

A mixture was prepared with 50 mM Tris-acetate (pH 8.6), 0.01% Triton X-100, 0.2 mM EDTA, 0.341 mM NAD+, 0.36 U GDH/mL, 20 μM resazurin, and 0.45 U/mL diaphorase. A 10× glutamate solution consisting of 625 μM glutamate, 50 mM Tris acetate (pH 8.6), 0.01% Triton, and 0.2 mM EDTA was prepared. Using the Janus automated pipettor, we pipetted the components in the following sequence: (1) 22 μL of the mixture, (2) 0.5 μL of the hit compounds stocked in a 384-well plate at 1 mM, and (3) 2.5 μL of a 10× glutamate solution. The reaction was incubated for 2 h before reading. A positive control (maximum activity) was obtained with DMSO incubation, and a negative control (minimal activity) was obtained from a glutamate-free solution. The reversibility assay was performed as follows: a mixture consisting of 250 nM GAC, 285 U/mL GDH, and 30 mM NAD+ in 50 mM Tris-acetate (pH 8.6), 0.1% Triton X-100, and 0.2 mM EDTA was prepared. The compounds were then added at a concentration 10-fold higher than their IC50 value and incubated for 90 min, after which the reaction was diluted 10-fold in 50 mM Tris-acetate (pH 8.6) and 0.1% Triton X-100. A control for 100% activity was prepared by incubation with DMSO. Five microliters of the reaction was then added to 45 μL of 5.55 mM K2HPO4, 2.2 mM glutamine, 22.7 μM resazurin, and 0.45 U/mL diaphorase prepared in 50 mM Tris-acetate (pH 8.6), 0.2 mM EDTA, and 0.01% Triton X-100. The percentage of recovered activity was calculated as follows:

GLS–GDH Absorbance Assay

To determine the IC50 values of the compounds C1–C10 for GAC and KGA, serial dilutions of the compounds were preincubated with 2.5 nM purified enzymes (41) for 15 min in 50 mM Tris-acetate (pH 8.6), 0.2 mM EDTA, 3 mM NAD+, 2.5 U GDH, and 5 mM K2HPO4. The reaction was started with the addition of 2 mM glutamine. The absorbance values measured in a glutaminase-free reaction were subtracted from the absorbance values measured for the test assays. For the C9 analogs, the reaction was carried out in 50 mM Tris-acetate (pH 8.6), 0.2 mM EDTA, 2 mM NAD+, 0.6 U of GDH, 20 mM K2HPO4, 10 nM GAC, and 7.5 mM glutamine. For the GLS2 reaction, the reaction contained GLS2 at 5 nM and 3 U of GDH. Compounds were added in serial dilutions made in 1% DMSO (no preincubation was performed). Readings were performed on a PerkinElmer EnSpire 2300 multilabel plate reader at 340 nm. The percent activity was calculated based on the DMSO control reaction (100% activity). Adjustment of inhibitor dose–response curves was performed with the program GraphPad Prism v8.0 (GraphPad Software, USA) using the log(inhibitor) vs normalized response (variable slope) function.

Clusterization and In Silico Analysis

Clusterization was performed with Lounkine et al.63 Physicochemical parameters were calculated with the Percepta Platform (Advanced Chemistry Development, Inc., ACD/Labs). Druggability and toxicity were also evaluated with the Open Babel program.64

Cell Culture

MDA-MB-231 (ATCC HTB-26), MDA-MB-453 (ATCC HTB131), SKBR3 (ATCC HTB-30), and MCF-10A (ATCC CRL-10317) cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and maintained in an RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% antimicrobial agents (penicillin–streptomycin) at 37 °C under 5% CO2 in a humidified atmosphere. HMECs were obtained from Lonza and immortalized in our laboratory using a retroviral vector (pBABE-hygro-hTERT) containing the telomerase reverse transcriptase catalytic subunit (TERT) sequence, generating iHMECs. pBABE-hygro-hTERT was a gift from Bob Weinberg (Addgene plasmid #1773).65 iHMECs were grown in MEGM (mammary epithelial cell growth medium). MCFA-10A cells were cultured in DMEM F12 culture medium supplemented with 5% horse serum, 20 ng/mL epithelial growth factor (EGF), 0.1 μg/mL cholera toxin, 10 μg/mL bovine insulin, and 0.5 μg/mL hydrocortisone. All cell lines were cultivated for a maximum of 10 passages after thawing. Cells used in in vitro assays were viable (90–100%), as evaluated with trypan blue staining. shGFP, shGLS, and shGLS + GLS2 MDA-MB-231 subcell lines were previously described.4

Proliferation Assay

The cells were seeded at a density of 2000 or 3000 cells/mm2 in 96-well plates in the complete medium. For the glutamine deprivation assay, after 24 h, the medium was replaced with RPMI containing 0–2 mM glutamine and supplemented with 10% dialyzed FBS (Thermo Fisher). For the inhibition assays, the cells were incubated with the complete medium containing the vehicle (0.1% v/v of DMSO), serial dilutions of BPTES (Sigma Aldrich), CB-839 (Selleck Chemicals), and C1–C10 and C9 analogs (Chembridge) 24 h after seeding. The cells were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde and stained with 0.4 μg/mL DAPI after 48 or 72 h of treatment. The stained nuclei were quantified using the fluorescence microscope and plate reader Operetta (PerkinElmer) and the software Columbus (PerkinElmer). The cell number was normalized by the final number of untreated cells (DMSO control, 100% cell growth) and the number of seeded cells (0% cell growth) to graphically show the dose that may lead to cell death (when the number of measured cells after treatment is smaller than the number of seeded cells). Adjustment of inhibitor dose–response curves was performed with the program GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, USA) using the log(inhibitor) vs response (variable slope) function.

Fluorescent Cell Assays

After 48 h of treatment with compound C1 or C9, MDA-MB-231 cells were labeled with 30 μM EdU for 30 min followed by fixation with 3.7% paraformaldehyde in PBS at room temperature for 20 min. Cells were washed twice in 1× PBS and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in 1× PBS for 15 min at room temperature. EdU was then labeled with Alexa Fluor 488 (AF488) using the Click-iT EdU kit (Life Technologies) following the manufacturer’s instructions. After blocking for 30 min with 3% BSA in 1× PBS, the cells were incubated with 1:250 anti-pHH3 (S10) primary antibody (Cell Signaling Technologies, #9706) diluted in TBS at room temperature for 60 min. Cells were washed with 1× PBS and then incubated with 1:300 AF647-labeled secondary antibody (Thermo Fischer Scientific, A21247) and 1 μg/mL Hoechst 33342 in a Tris-borate solution at room temperature for 60 min. After washing twice with 0.05% Tween-20 in PBS, the cells were immersed in PBS. For the MitoTracker labeling, 3000 MDA-MB-231 cells were seeded in 96-well plates and allowed to adhere overnight. Cells were treated with the indicated compounds diluted in DMSO (final concentration of 0.05%) for 72 h. Following cell incubation with 100 nM of MitoTracker CMXRos (Life Technologies) for 40 min in the complete medium, cells were fixated with 4% PFA, briefly rinsed with PBS, and incubated with 300 nM DAPI for 10 min. To measure intracellular α-ketoglutarate levels, we used a biosensor based on the fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) technology PII-TC3-R9P.66 Briefly, MDA-MB-231 cells were transfected with the PII-TC3-R9P using polyethylenimine (PEI/DNA 3:1 ratio) for 6 h. Cells were incubated with fresh medium and allowed to recover for 18 h before treatment with 10 μM of the indicated compounds diluted in DMSO (final concentration of 0.05%) for 24 h. Cells were excited using the 425–450 nm filter, and emission was detected using the 460–500 nm (direct fluorescence, mCerulean) and 530–590 nm (FRET) filters. The fluorescence mean intensity of the cells was measured for each channel, and after background subtraction, the mean intensity of the acceptor (FRET) was divided by the mean intensity of the donor (mCerulean) and then normalized for the time 0. Cells were treated with increasing doses of C9.22 diluted in DMSO (final concentration of 0.05%) for 48 h. Cells were then incubated with 500 nM of MitoTracker Deep Red (Life technologies), 10 μg/mL propidium iodide, and 5 μg/mL Hoescht for 45 min in the complete medium at 37 °C, 5% CO2. Cells were evaluated with the fluorescence microscope and plate reader Operetta (PerkinElmer) and analyzed with the software Columbus or Harmony (PerkinElmer).

3D Cell Growth

Twelve thousand and five hundred MDA-MB-231 cells were used to form each spheroid using the 96-well Bioprinting kit (Greiner Bio-One) following the manufacturer’s instructions. For the spheroid formation, the plate containing the cells pretreated with NanoShuttle-PL was placed on top of the spheroid drive for 48 h in a 5% CO2 incubator followed by 24 h incubation without the spheroid drive. Cells were then treated with 20 μM of each compound in 0.1% DMSO (vehicle) for 14 days. Half the cell culture medium volume was changed every 4 days. To prevent cell loss, the plate was placed on the holding drive while replacing the cell culture medium with a fresh medium containing the compounds. Spheroids were incubated with 0.5 μg/mL propidium iodide (Sigma-Aldrich) and 2 μM Calcein AM (Cayman Chemical Company) for 20 min before image acquisition using the Operetta High Content Analysis System (Perkin-Elmer). Data were analyzed with the software Columbus (Perkin Elmer).

Western Blotting

Cells were lysed in a 150 mM NaCl, 25 mM HEPES (pH 8.0), 1 mM EDTA, and 1% Triton X-100 solution; 50 mM β-glycerophosphate, 10 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 50 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM PMSF, 10 μM leupeptin, 1 μM pepstatin, 2 μg/mL aprotinin, and 2 mM dithiothreitol were then added to the cells. After one freeze–thaw cycle, the lysates were centrifuged at 10,600g for 10 min at 4 °C. After that, the samples were quantified by the Bradford method.67 Ten to fifty micrograms of cell lysate was separated on a 10% acrylamide SDS-PAGE gel, and the slope of the curve was used to measure glutaminase activity. Western blotting was performed as previously described.68 Antibodies against GLS (Rhea Biotech, IM-0322), vinculin (Abcam, #ab18058), and GLS2 (Abcam, #ab91073) were used. Anti-rabbit HRP-linked secondary antibody (Cell Signaling, #7074) was used at a 1:1000 dilution, while another antibody from Sigma (#A0545) was used at a 1:5000 dilution. The anti-mouse secondary antibody from Sigma (#A4416) was used at a 1:5000 dilution.

Glutamine Consumption

The measurements were performed either with the BioProfile Basic-4 analyzer equipment (NOVA) following the manufacturer’s instructions or by using an enzymatic assay and a previously published method69 with some modifications. Cells were seeded at a density of 937.5 cells/mm2 in 96-well plates in 50 μL of the RPMI complete medium and incubated for 12 h. Next, 10 μL of the medium was combined with 190 μL of a solution of 50 mM Tris-acetate (pH 8.6), 0.2 mM EDTA (pH 8.0), 2 mM NAD+, 50 mM K2HPO4, and 0.3 U of GDH; the absorbance was measured at 340 nm using an EnSpire plate reader (PerkinElmer). Then, 60 nM recombinant glutaminase C (purified as described in ref (42)) was added to the same reaction mixture to obtain the total amount of glutamine. The glutamate and glutamine concentrations were estimated based on the slope of a standard curve. Data were normalized by the number of cells, which was calculated as described above.

Dynamic Light Scattering

mGAC was purified as previously described.15 Gel filtration was performed with either 500 mM or 150 mM NaCl. Polymer assembly was induced by incubating freshly purified protein (in 150 mM NaCl buffer) with 20 mM phosphate. The protein was incubated for 24 h at 4 °C with each compound at 200 μM or 1% DMSO. Before measurement, all samples were microcentrifuged at maximum speed at 4 °C for 5 min. The sample was loaded into a quartz cuvette (ZMV1002, 1.25 mm light path, 105.231-QS, Hellma), and an SOP protocol was carried out on a Zetasizer μV (Malvern) after 120 s of primary equilibration at 10 °C. Measurements were performed in triplicate and analyzed using Zetasizer software.

NanoDSF

Thirty microliters of a solution containing 30 mM HEPES (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM TCEP, 20 mM KH2PO4, and 0.4 mg/mL GAC, combined with 1% DMSO, 10 μM of CB-839, or 200 μM of C9.22, was read with Tycho NT.6 applying a temperature gradient from 23 to 95 °C.

Thermophoresis

Twenty microliters of a solution containing 30 mM HEPES (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM TCEP, 20 mM KH2PO4, 0.5 mg/mL BSA, 0.05% Tween 20%, and 80 nM of GAC labeled with FITC as previously described70 was mixed with a serial dilution of CB-839 or C9.22. Solutions were read with a Monolith NT.115 Microscale Thermophoresis instrument using standard capillaries and 40% blue laser excitation.

Acknowledgments

We thank LNBio for access to core facilities as well as for financial support. We are very grateful to Dr. Alessandra Girasole for expert technical support.

Glossary

ABBREVIATIONS

- TNBC

triple-negative breast cancer

- PR

progesterone receptor

- ER

estrogen receptor

- GLS

glutaminase

- BPTES

bis-2-(5-phenylacetamido-1,3,4-thiadiazol-2-yl) ethyl sulfide

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsptsci.1c00226.

HTS assay optimization (Figure S1); more information about the HTS hits (Figure S2); C1–C10 dose–response curves on the glutaminase activity (Figure S3); glutamine-deprivation and BPTES effect on cells (Figure S4); C2–C8 and C10 dose–response curves on different cell lines (Figure S5); C9 analogues’ dose–response curves on the GAC enzyme activity (Figure S6); selected C9 analogues’ dose–response curves on the GLS2 enzyme activity (Figure S7); selected C9 analogues’ dose–response curves on the MDA-MB-231 and SKBR3 cell lines (Figure S8); dose–response curve of C9.22 on the MDA-MB-231 (Figure S9); Excel file with six spreadsheets containing raw and processed HTS data, provided as a separated file (Table S1); the final 100 compounds hit list (Table S2); drug-like properties calculated by the OpenBabel (Table S3); and in silico safety(Table S4) (PDF)

ADME and physicochemical profile of the 11 resupplied compounds (XLSX)

Author Contributions

∥ R.K.E.C., C.R., J.C.H.C., and L.P. contributed equally. The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

We thank São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) for fellowships to R.K.E.C. (#2016/09077-4) D.A. (#2014/17820-3), and C.F.R.A. (#2013/23510-4) and research grant to S.M.G.D. (#2014/15968-3, #2015/25832-4, and #2019/16351-3); CEPID grant (#2013/07600-3 to R.V.C.G.); and the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development–CNPq (grant 405330/2016-2 to R.V.C.G.).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Hanahan D.; Weinberg R. A. Hallmarks of Cancer: The Next Generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlova N. N.; Thompson C. B. The Emerging Hallmarks of Cancer Metabolism. Cell Metab. 2016, 23, 27–47. 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Márquez J.; López de la Oliva A. R.; Matés J. M.; Segura J. A.; Alonso F. J. Glutaminase: A Multifaceted Protein Not Only Involved in Generating Glutamate. Neurochem. Int. 2006, 48, 465–471. 10.1016/j.neuint.2005.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias M. M.; Adamoski D.; dos Reis L. M.; Ascenção C. F. R.; De Oliveira K. R. S.; Carolina A.; Mafra P.; da Silva Bastos C. A.; Quintero M.; Cassago C. D. G.; Ferreira I. M.; Fidelis C. H. V.; Rocco S. A.; Bajgelman M. C.; Stine Z.; Berindan-neagoe I.; Calin G. A.; Ambrosio A. L. B.; Dias S. M. G. GLS2 Is Protumorigenic in Breast Cancers. Oncogene 2020, 39, 690–702. 10.1038/s41388-019-1007-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmerman L. A.; Holton T.; Yuneva M.; Louie R. J.; Padró M.; Daemen A.; Hu M.; Chan D. A.; Ethier S. P.; van’t Veer L. J.; Polyak K.; McCormick F.; Gray J. W. Glutamine Sensitivity Analysis Identifies the xCT Antiporter as a Common Triple-Negative Breast Tumor Therapeutic Target. Cancer Cell 2013, 24, 450–465. 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Geldermalsen M.; Wang Q.; Nagarajah R.; Marshall A. D.; Thoeng A.; Gao D.; Ritchie W.; Feng Y.; Bailey C. G.; Deng N.; Harvey K.; Beith J. M.; Selinger C. I.; O’Toole S. A.; Rasko J. E. J.; Holst J. ASCT2/SLC1A5 Controls Glutamine Uptake and Tumour Growth in Triple-Negative Basal-like Breast Cancer. Oncogene 2016, 35, 3201–3208. 10.1038/onc.2015.381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L.; Moss T.; Mangala L. S.; Marini J.; Zhao H.; Wahlig S.; Armaiz-Pena G.; Jiang D.; Achreja A.; Win J.; Roopaimoole R.; Rodriguez-Aguayo C.; Mercado-Uribe I.; Lopez-Berestein G.; Liu J.; Tsukamoto T.; Sood A. K.; Ram P. T.; Nagrath D. Metabolic Shifts toward Glutamine Regulate Tumor Growth, Invasion and Bioenergetics in Ovarian Cancer. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2014, 10, 728. 10.1002/msb.20134892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seltzer M. J.; Bennett B. D.; Joshi A. D.; Gao P.; Thomas A. G.; Ferraris D. V.; Tsukamoto T.; Rojas C. J.; Slusher B. S.; Rabinowitz J. D.; Dang C. V.; Riggins G. J. Inhibition of Glutaminase Preferentially Slows Growth of Glioma Cells with Mutant IDH1. Cancer Res. 2010, 70, 8981–8987. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moncada S.; Higgs E. A.; Colombo S. L. Fulfilling the Metabolic Requirements for Cell Proliferation. Biochem. J. 2012, 446, 1–7. 10.1042/BJ20120427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Son J.; Lyssiotis C. A.; Ying H.; Wang X.; Hua S.; Ligorio M.; Perera R. M.; Ferrone C. R.; Mullarky E.; Shyh-Chang N.; Kang Y.; Fleming J. B.; Bardeesy N.; Asara J. M.; Haigis M. C.; DePinho R. A.; Cantley L. C.; Kimmelman A. C. Glutamine Supports Pancreatic Cancer Growth through a KRAS-Regulated Metabolic Pathway. Nature 2013, 496, 101–105. 10.1038/nature12040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang C. V. Glutaminolysis: Supplying Carbon or Nitrogen or Both for Cancer Cells?. Cell Cycle 2010, 9, 3884–3886. 10.4161/cc.9.19.13302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu J. M.; Lee S. H.; Seong J. K.; Han H. J. Glutamine Contributes to Maintenance of Mouse Embryonic Stem Cell Self-Renewal through PKC-Dependent Downregulation of HDAC1 and DNMT1/3a. Cell Cycle 2015, 14, 3292–3305. 10.1080/15384101.2015.1087620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H.-W.; Yu X.-J.; Wu W.-C.; Chen J.; Shi M.; Zheng L.; Xu J. GLUT1 and ASCT2 as Predictors for Prognosis of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0168907 10.1371/journal.pone.0168907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Gómez C.; Matés J. M.; Gómez-Fabre P. M.; del Castillo-Olivares A.; Alonso F. J.; Márquez J. Genomic Organization and Transcriptional Analysis of the Human L-Glutaminase Gene. Biochem. J. 2003, 370, 771–784. 10.1042/BJ20021445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira A. P. S.; Cassago A.; Gonçalves K. D. A.; Dias M. M.; Adamoski D.; Ascenção C. F. R.; Honorato R. V.; de Oliveira J. F.; Ferreira I. M.; Fornezari C.; Bettini J.; Oliveira P. S. L.; Paes Leme A. F.; Portugal R. V.; Ambrosio A. L. B.; Dias S. M. G. Active Glutaminase C Self-Assembles into a Supratetrameric Oligomer That Can Be Disrupted by an Allosteric Inhibitor. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 28009–28020. 10.1074/jbc.M113.501346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]