Abstract

Ca2+ is a highly versatile intracellular signal that regulates many biological processes such as cell death and proliferation. Broad Ca2+-signaling machinery is used to assemble signaling systems with a precise spatial and temporal resolution to achieve this versatility. Ca2+-signaling components can be organized in different regions of the cell and local increases in Ca2+ within the nucleus can regulate different cellular functions from the increases in cytosolic Ca2+. However, the mechanisms and pathways that promote localized increases in Ca2+ levels in the nucleus are still under investigation. This review presents evidence that the nucleus has its own Ca2+ stores and signaling machinery, which modulate processes such as cell proliferation and tumor growth. We focus on what is known about the functions of nuclear Phospholipase C (PLC) in the generation of nuclear Ca2+ transients that are involved in cell proliferation.

Keywords: nucleus, calcium, phospholipase C (PLC), proliferation, cell signaling

Introduction

Ca2+ is a second messenger capable of regulating a plethora of cellular functions such as senescence, cell death and proliferation (de Miranda et al., 2019; Kunrath-Lima et al., 2018; Ueasilamongkol et al., 2020). To achieve this versatility, the spatial and temporal modes of Ca2+ signals may determine their specificity (Berridge, 2007). Ca2+ signals patterns can vary in different regions of the cell and increases in Ca2+ in the nucleus have specific biological outcomes from the effects of increases in cytosolic Ca2+ (Hardingham et al., 1997; Rodrigues et al., 2007). Nevertheless, the mechanisms and pathways that promote localized increases in Ca2+ levels within the nucleus still have many open questions. This review put forth current evidence that the nucleus has its own Ca2+ stores and signaling machinery, which modulate cell proliferation and tumor growth. We focus on how PLCs are involved in generating InsP3 (inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate)-mediated nuclear Ca2+ signals involved in cell proliferation.

The Nucleoplasmic Reticulum (NR)

The nuclear envelope (NE) is a structure comprising two phospholipid bilayers [the outer nuclear membrane (ONM), inner nuclear membrane (INM)] and intermembrane space (IMS). Only the INM or both nuclear membranes can reach deep within the nucleoplasm (Malhas et al., 2011). The ONM is contiguous with the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (Subramanian and Meyer, 1997). Because the IMS of the NE is continuous with the ER lumen, the nuclear Ca2 store could be regarded as part of the ER Ca2 store; this intranuclear network is referred to as the nucleoplasmic reticulum (NR) (Echevarria et al., 2003; Gomes et al., 2006; Malhas et al., 2011).

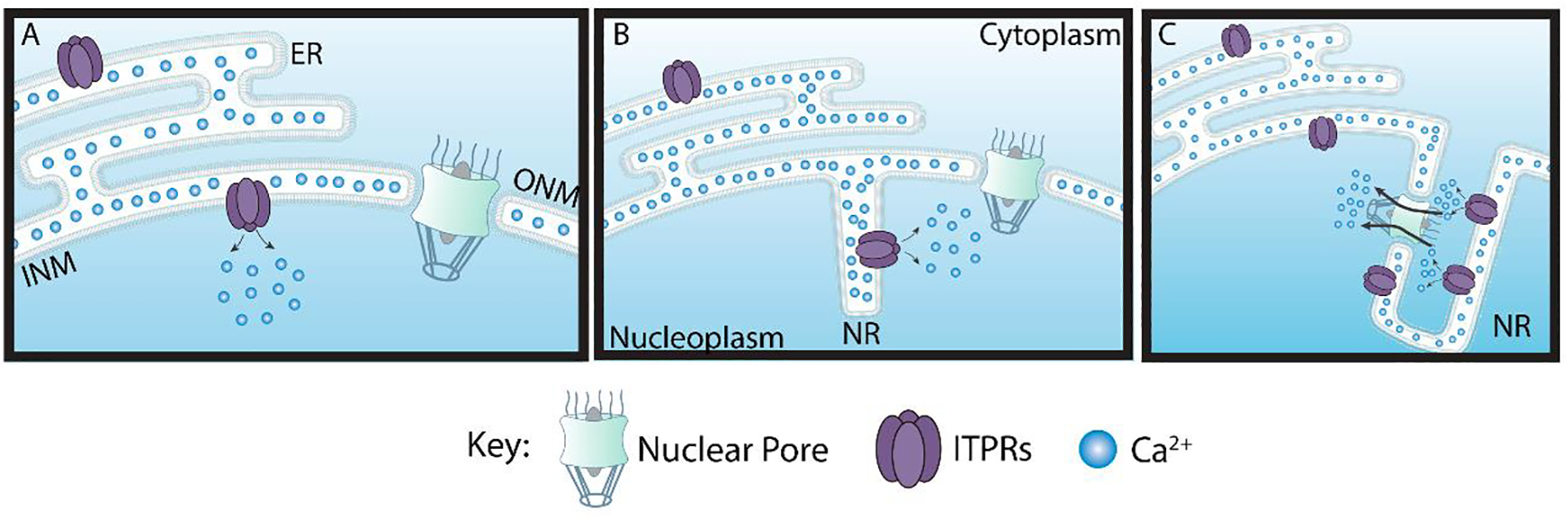

The NE invaginations have been observed in a wide range of cell types since the 1960s (Bourgeois et al., 1979). It was proposed that the NR invaginations fall into two main classes (Malhas et al., 2011). Type I invaginations are those where only the INM invaginates into the nucleoplasm (Figure 1B). Whereas type II involves the invagination of both the ONM and INM (Figure 1C). These invaginations are known to have the nuclear lamina, nuclear pore complex (NPC) and seemingly ended at nucleoli (Bourgeois et al., 1979; Malhas et al., 2011; Schoen et al., 2017). The NR is found under normal cellular conditions (M. Fricker et al., 1997; Mark Fricker et al., 1997; Langevin et al., 2010; Storch et al., 2007) and in pathological states (Bussolati et al., 2007; Malhas and Vaux, 2014). Although such structures have been observed in several cell types, they might not be universal (Figure 1A) (Bezin et al., 2008).

Figure 1. Schematic representations of types of membrane invagination of the Nucleoplasmic reticulum.

(A) There are cells without invaginations of the nuclear membranes. (B) Other cells can have type I invaginations where the inner nuclear membrane (INM) invaginates into the nucleoplasm or (C) type II invaginations that involve both the INM and outer nuclear membranes (ONM) invaginations into the nucleoplasm. ITPRs can be found either in the INM or on ONM. Nucleoplasmic Reticulum (NR)

Nuclear calcium release

The archetypal ER Ca2+ store is mobilized by inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (InsP3), agonist for InsP3 Receptors (ITPRs), or cADPR. The intracellular Ca2+-releasing messenger cADPR is an endogenous activator for Ryanodine Receptor (RyRs) (Lee et al., 1989). RyRs and ITPRs are expressed on NE and regulate nuclear Ca2+ signaling. For example, Ryanodine evoked a rise in the nucleoplasmic Ca2+ concentration in isolated mouse liver nuclei, suggesting the presence of RyRs at the nuclear membranes (Gerasimenko et al., 1995). Later, the localization of RyRs was observed using immunogold labeling on both NE membranes of starfish (Astropcten auranciacus) and oocytes (Santella and Kyozuka, 1997). The RyRs were seen via immunofluorescence in nuclei isolated from a mouse osteoblastic cell line MC3T3.E1 (Adebanjo et al., 1999), NE of chick embryonic ventricular cardiomyocytes (Abrenica and Gilchrist, 2000) and on intranuclear extensions of the NR of skeletal muscle-derived cell line C2C12 (Marius et al., 2006). It was suggested that nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NAADP) could release Ca2+ from the NE and generate nucleoplasmic Ca2+ signals via RyRs (Gerasimenko et al., 2003).

To date, the most well-studied mechanism for nuclear Ca2+ release is via the activation of ITPRs. The genomes of vertebrates encode three isoforms of ITPRs (Prole and Taylor, 2016). These receptors were observed in the NE since its first demonstration within a cell by immunocytochemistry (Ross et al., 1989). All ITPRs isoforms were localized throughout the nucleoplasm and in both NE membranes, in different cells (Echevarria et al., 2003; Huh and Yoo, 2003; Yoo et al., 2005). This review will focus on the mechanism of InsP3-mediated nuclear calcium signals that mediate cell proliferation.

Nuclear Ca2+ uptake

The Sarco/Endoplasmic Reticulum Calcium ATPases (SERCA) are responsible for pumping Ca2+ from the cytosol into the lumen of the ER (Vandecaetsbeek et al., 2011). In 1982, Kulikova et al. identified a nuclear Ca2+ ATPase (NCA)(Kulikova et al., 1982). Two Ca2+ ATPases were identified in chromaffin cells: a 140 kDa protein restricted to a region close to the nucleus and a 100 kDa protein diffusely distributed throughout the cells (Burgoyne et al., 1989). They indicated that the effects of InsP3 resulted in a highly localized rise in cytosolic calcium concentration initiated in a region close to the nucleus. Later, it was demonstrated that rat liver nuclei have a high capacity to uptake Ca2+, and InsP3 can release part of Ca2+ accumulated by the nuclei (Nicotera et al., 1990). Immunoblot and proteolysis analysis suggested that SERCA and NCA from rat liver are similar or identical (Lanini et al., 1992). The NCA from rat liver was identified on ONM (Humbert et al., 1996; Rogue et al., 1998). A polyclonal antibody raised against SERCA type 2b recognized a 105 kDa protein band in isolated rat liver nuclear samples (Rogue et al., 1998). NCA activity was stimulated by cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) phosphorylation (Rogue et al., 1998).

A second pathway proposed for restoring the nuclear calcium pool is mediated by inositol 1,3,4,5-tetrakisphosphate (InsP4). InsP3 can be converted to InsP4 by a family of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate 3-kinase (Choi et al., 1990). InsP4 binding sites were identified on the INM and ONM, but the ONM has a higher affinity to InsP4 (Koppler et al., 1993). InsP4−mediated nuclear calcium uptake becomes operative above 1 μM free calcium concentration in the uptake medium (Humbert et al., 1996). A 74 kDa protein was proposed as an inositol 1,3,4,5-tetrakisphosphate receptor (Köppler et al., 1996). However, this protein is still to be found and characterized.

The NE expresses an electrogenic Na+/Ca2+ Exchanger (NCX) (Secondo et al., 2020). NCX plays an important function in Ca2+ homeostasis by coupling the efflux/influx of Ca2+ ions to the influx/efflux of Na+. There are three isoforms of NCX (Philipson and Nicoll, 2000). The NCX isoform 1 is found on the INM (nuNCX1), allowing Ca2+ flow from nucleoplasm into the NE lumen (Secondo et al., 2020). Na+/K+ ATPases located at the INM maintain the Na+ gradient for the proper function of the exchanger (Garner, 2002). The GM1 ganglioside localized at INM modulates NCX activity (Wu et al., 2005; Xie et al., 2002). It thus remains an open question how GM1/NCX complex correlates its function with other receptors, channels, exchangers and how this complex contributes to the dynamics of nuclear Ca2+ homeostasis.

InsP3-mediated nuclear Ca2+ signaling

Molecules necessary for InsP3-mediated Ca2+ signaling are found within the nucleus. For example, the NE membrane contains phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinase (PIPK) (Cocco et al., 1987; Smith and Wells, 1983), which synthesizes inositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2). Interestingly, some reports suggest that PIPK and PIP2 are associated with nuclear membrane structures, including invaginations of the nuclear envelope and found in subnuclear speckle domains (Boronenkov et al., 1998; Osborne et al., 2001; Tabellini, 2003). The nucleus also contains lipids not associated with the nuclear membranes, which can be found in the nucleoplasm (Martelli et al., 2004).

PLC is the enzyme that hydrolyzes PIP2 to generate InsP3 and diacylglycerol (DAG) following their activation. In mammals, the PLC family is composed of 13 isozymes divided into six subfamilies: PLCβ (1, 2, 3 and 4), PLCγ (1 and 2), PLCδ (1, 3 and 4), PLCε, PLCη (1 and 2) and PLCζ, based on the activation regulatory mechanism and structure (Nakamura and Fukami, 2017). Some PLC isoforms like PLCβ1 (Cocco et al., 1999; Manzoli et al., 1997; Martelli et al., 1992), PLCγ1 (Bertagnolo et al., 1995; Ferguson et al., 2007), PLCδ1 (Yagisawa, 2006) and PLCδ4 (de Miranda et al., 2019; Kunrath-Lima et al., 2018) have been reported to localize in the nucleus. This review will highlight the main findings of how nuclear PLC regulates cell proliferation.

The function of nuclear PLC in cell proliferation

The first report about the possible involvement of nuclear PLC activation on cell proliferation came from the observation that Swiss 3T3 fibroblasts treated with insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) induced PIP2 hydrolysis, with a concomitant increase in nuclear DAG levels and the translocation of protein kinase C (PKC) to the nucleus (Divecha et al., 1991). Later, it was demonstrated that PLCβ1 knockdown abolished the mitogenic response of Swiss 3T3 cells to IGF-I, indicating a role of this enzyme in cell proliferation (Manzoli et al., 1997). PLCβ1 exists as two distinguishable polypeptides of 150 kDa (PLCβ1a) and 140 kDa (PLCβ1b), which differ only in a short region of their carboxyl-terminus (Bahk et al., 1994). The nuclear localization signal of this enzyme is determined by a cluster of lysine residues (between positions 1055 and 1072), common to both isoforms (Kim et al., 1996). PLCβ1a localizes in nuclei and plasma membrane, and PLCβ1b exists almost entirely in the nucleus (Bahk et al., 1998). Indeed, the role of PLCβ1 in cell proliferation was confirmed by the finding that PLCβ1 overexpression of both isoforms is sufficient to elevate the expression of cyclin D3 and cyclin-dependent kinase 4 (cdk4). This complex phosphorylates the retinoblastoma protein (pRb), a well-known tumor suppressor. This tumor suppressor activity represses genes activated by the E2F family of transcription factors, thus enhancing cell cycle G1/S progression (Faenza et al., 2000). The mechanism of IGF-1-dependent stimulation of the nuclear PLCβ1 in Swiss 3T3 cells is via nuclear translocation of the extracellular regulated kinase (ERK) 1/2 that phosphorylates PLCβ1 at serine 982 (Xu et al., 2001). PIP2 was seen to increase dramatically as synchronized murine erythroleukemia (MEL) cells entered S-phase. This did not coincide with any significant changes in the nuclear mass levels of this lipid, suggesting that the rate of turnover of this molecule was increased. However, a large increase in nuclear phosphatidylinositol 5-phosphate (PI5P) mass was observed when MEL cells were in G1 phase (Clarke et al., 2001). A subsequent study demonstrated two waves of nuclear PLCβ1b activity in serum-stimulated HL-60 cells were detected during the progression through the G1 phase of the cell cycle. This enzyme activity was found to be equally important for the progression into the S phase (Lukinovic-Skudar et al., 2007). An early report observed an increase of nuclear DAG levels followed by nuclear PKC translocation in regenerating rat liver with close parallel with DNA synthesis and initiating mitosis (Banfic et al., 1993). In HL-60 cells, a nuclear increase of DAG levels was coincident with the G2/M phase transition. This increase in DAG levels was sufficient for PKCβII-mediated phosphorylation of Lamin B (Sun et al., 1997). In turn, Lamin B phosphorylation and depolymerization can cause nuclear envelope breakdown, one critical event for mitosis progression (Güttinger et al., 2009). A few reports linked the PLCβ1 activity with the G2/M phase of the cell cycle. A study in HL-60 showed two peaks of nuclear PLCβ1b activities, one that occurs in the late G1 phase and another at the G2/M (Lukinoviƈ-Škudar et al., 2005). In MEL cells, PLCβ1b regulates Lamin B1 phosphorylation via PKCα activation in the nucleus and G2/M progression (Fiume et al., 2009). Cumulatively, these results point to PLCβ1 as an important player in driving cells to the G1/S and G2/M phases of the cell cycle. PLCβ1 is not only important for cell proliferation. Its dysregulation contributes to other cellular processes and diseases, including cancer. For example, deletion of PLCβ1 gene is present in myelodysplastic syndrome patients that rapidly evolved to acute myeloid leukemia (Lo Vasco et al., 2004) and treatment of C2C12 myoblast with insulin induces a dramatic rise of both PLCβ1 isoforms that leads to myoblast differentiation (Faenza et al., 2003).

PLCγ1 was also described inside the nucleus (Bertagnolo et al., 1995; Ferguson et al., 2007; Marmiroli et al., 1994; Mazzoni et al., 1992; Santi et al., 1994; Ye et al., 2002). Activated PLCγ1 induced nuclear phosphatidylinositol (PI) hydrolysis and DAG generation (Klein et al., 2004; Malviya and Klein, 2006). PLCγ1 nuclear translocation was observed after the nerve growth factor (NGF) stimulus. Interestingly, the authors presented evidence that the SH3 domain is required for PLCγ1 to function as a nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) for the nuclear phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase enhancer (PIKE). This mechanism allows PIKE to activate nuclear phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase (PI3K) to stimulate cell proliferation (Ye et al., 2002). It was demonstrated that nuclear extract of mouse liver, obtained after in vivo intraperitoneal epidermal growth factor (EGF) injection, presented two PLCγ1 bands by immunoblot: one band at 150 KDa and the other at 120 KDa. This 120 KDa protein was identified as PLCγ1 devoid of 243 amino acids at the N-terminal end. PLCγ1 was found interacting with phosphorylated epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), PIKE and PI3K, in response to the EGF signal to the nucleus in vivo. Another report showed that EGF stimulus decreased PLCγ1 expression at the plasma membrane and increased its levels within the nucleus after p120-catenin (p120) knockdown (Li et al., 2020). It is well-known that p120 stabilizes the E-cadherin/catenin complex and plays an important function in cell-cell adhesion. Decreased expression of p120 correlates with the occurrence, development, and prognosis of several types of cancers, such as cancers of the bladder, breast, esophagus and prostate.

Notwithstanding, the PLCδ1 is generally found on the cytoplasm of quiescent cells (Okada et al., 2005). However, the PLCδ1 has nuclear exclusion signal (NES) and nuclear localization signal (NLS) that contribute to the nucleus/cytoplasm shunt (Yagisawa et al., 2006). It was performed mutations on regions of the C-terminal (X domain) of this PLC that showed the presence of K432 and K434 necessary but not sufficient for the nuclear transport (Okada et al., 2002). PLCδ1, PLCδ3, but not in PLCδ4, has this canonical leucine-rich NES sequence in their EF-hand motifs (Yagisawa, 2006). Okada and coworkers (2005) presented evidence that nuclear import of PLCδ1 is induced by increased cytoplasmic calcium concentration through a direct calcium interaction with importin β1 (Okada et al., 2005). The authors suggested that glutamate stimulation of hippocampal neurons induces PLCδ1 nuclear localization and decreased nuclear area. Hypoxic stress and massive calcium influx cause a similar phenotype and might be associated with cell stress and death (Okada et al., 2010). Also, nuclear PLCδ1 has been associated with a role in cell cycle progression. Stalling and colleagues identified the accumulation of PLCδ1 in the nucleus during the G1-S phase in a fibroblast cell line, with increased expression of cyclin E (Stallings et al., 2008, 2005). The authors suggest that the increase in cellular calcium concentration and nuclear PIP2 augmentation are sufficient to induce the PLC translocation. This increased cellular calcium concentration could stimulate PLCδ1 inducing PIP2 hydrolyzes, InsP3 formation, and nuclear calcium increase.

Regarding the PLCδ4, it was showed that this PLC is majorly nuclear and responsible for regulating the transition between the G1 and S phase of the cell cycle (Liu et al., 1996). The authors presented high proliferation tissues with increased PLCδ4 mRNA when compared to resting cells. PLCδ4 knockout animals showed a delay at the S phase in regenerating liver cells, suggesting that this PLC controls the timing of DNA synthesis (Yagisawa et al., 2006). Fukami and colleagues presented evidence that growth factors such as IGF-1 and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) could increase the expression of nuclear PLCδ4 and induce a calcium spike (Fukami et al., 2000). Later, it was demonstrated that knockdown of PLCδ4 in adipose-derived mesenchymal stromal cell-induced cell cycle arrest with accumulation on G1 phase and cell senescence increased mRNA for p16INK4A and p21Cip1 (Kunrath-Lima et al., 2018). It was shown that EGF-induced nuclear signaling is mediated by nuclear PLCδ4 (de Miranda et al., 2019). When InsP3 buffer directed to the nucleus was used, a reduction of nuclear calcium release after EGF stimulation. PLCδ4 knockdown decreased nuclear PIP2 hydrolysis, InsP3 accumulation, nuclear calcium increase, and diminished nuclear PKC activity in a liver cell line. Confirming Kunhath-Lima’s findings, when PLCδ4 was silenced, cell proliferation was reduced, with no decrease in cell viability. To understand the molecular role of PLCδ4 in proliferation interference, the authors analyzed the expression of cell cycle-dependent cyclins. They observed diminished expression of cyclin A and cyclin B1 (G2/M stimulator), which explains the arrest between the G1 and S phases. Likewise, when nuclear InsP3 buffer was used, a similar reduction in the cyclin A and B1 was observed. In brief, these results confirm the importance of nuclear PLC activation in cell proliferation.

Conclusions

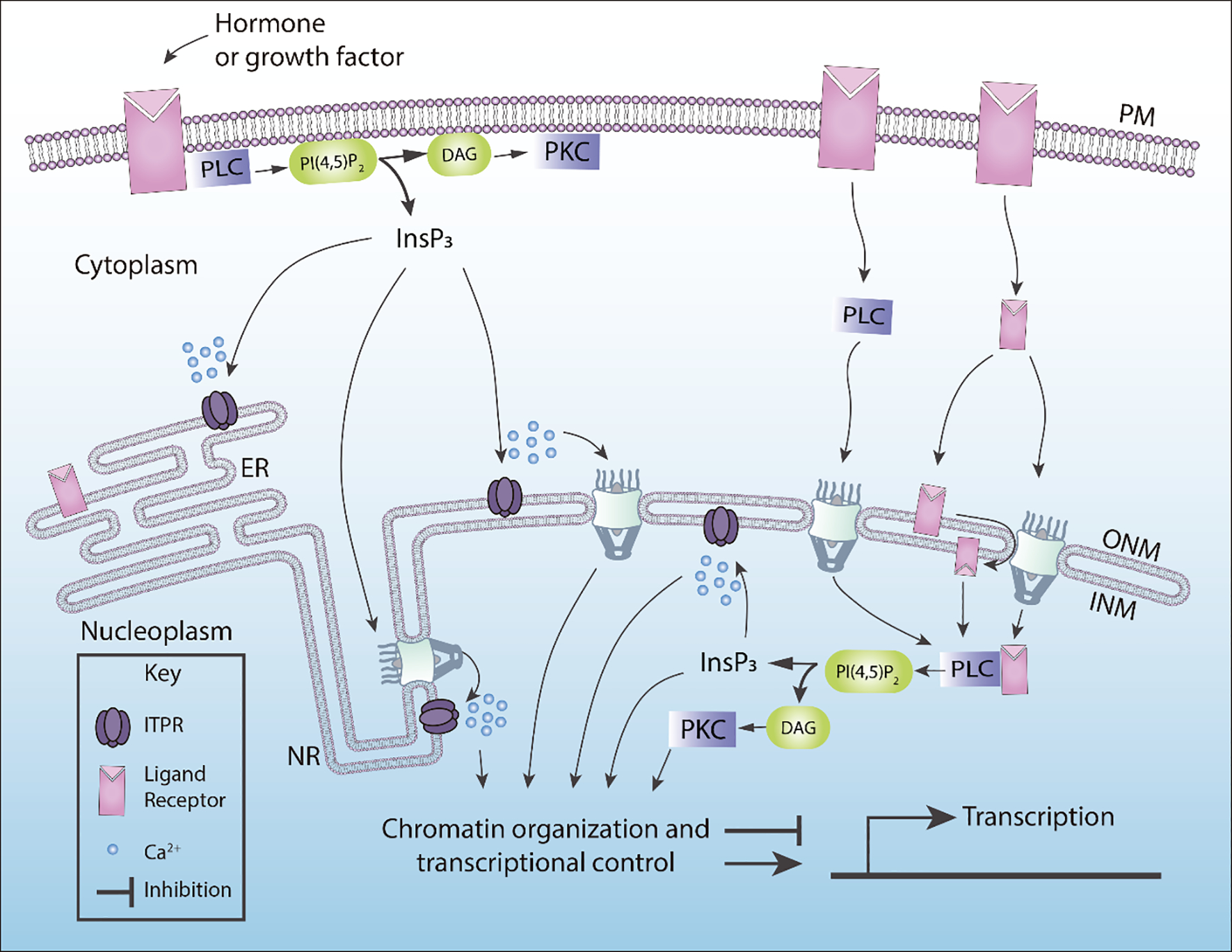

Active PLCs can translocate from the cytoplasm to the nucleus or can be activated directly within the nucleus (Figure 2). The growth factor receptors play an important role in the activation of nuclear PLCs. The mechanism by which growth factors stimulate this reaction involves the tyrosine phosphorylation-dependent activation. There are few possible ways to trigger nuclear PLCs. For example, IGF-1 receptors induced nuclear translocation of ERK that phosphorylate nuclear PLCβ1 (Xu et al., 2001). New evidence suggested that phosphorylated receptors such as hepatocyte growth factor receptor, insulin receptor and epidermal growth factor receptor can translocate from cytoplasm to the nucleus to activate InsP3 mediated calcium signals (de Miranda et al., 2019; Gomes et al., 2008; Rodrigues et al., 2008). Exactly how receptors tyrosine kinases traffic to the nucleus to stimulate specific PLCs isoforms is still under investigation.

Figure 2. Summary of the pathways that regulate nuclear PLC activation.

Activated PLCs can translocate to the nucleus to generate InsP3, or receptors can translocate to the nucleus to trigger nuclear PLCs. Some of the putative pathways described in this figure are controversial. In particular, how receptors tyrosine kinases (RTK) can reach the nucleus. InsP3 Receptors (ITPRs) can be found in the ONM or INM. Nuclear InsP3 levels can be mediated via the diffusion through nuclear pore complexes, which in turn can activate nuclear ITPRs. Nucleoplasmic Reticulum (NR), Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER), outer nuclear membrane (ONM), inner nuclear membrane (INM).

In summary, we greatly expanded our understanding of the functional importance of nuclear PLC in the regulation of cell proliferation in the last 20 years. However, many biochemistry details are still not fully understood. For example, we know very little about the function of nuclear PLC in processes like chromatin organization and gene expression. It will be an exciting future challenge to identify the specific components that might interact with nuclear PLC in the context of chromatin organization under the calcium dynamics.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank FAPEMIG, CAPES, and CNPq for supporting this work.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abrenica B, Gilchrist JSC, 2000. Nucleoplasmic Ca2+loading is regulated by mobilization of perinuclear Ca2+. Cell Calcium 28, 127–136. 10.1054/ceca.2000.0137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adebanjo OA, Anandatheerthavarada HK, Koval AP, Moonga BS, Biswas G, Sun L, Sodam BR, Bevis PJR, Huang CL-H, Epstein S, Lai FA, Avadhani NG, Zaidi M, 1999. A new function for CD38/ADP-ribosyl cyclase in nuclear Ca2+ homeostasis. Nat. Cell Biol 1, 409–414. 10.1038/15640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahk YY, Lee YH, Lee TG, Seo J, Ryu SH, Suh PG, 1994. Two forms of phospholipase C-beta 1 generated by alternative splicing. J. Biol. Chem 269, 8240–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahk YY, Song H, Baek SH, Park BY, Kim H, Ryu SH, Suh P-GG, 1998. Localization of two forms of phospholipase C-β1, a and b, in C6Bu-1 cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Lipids Lipid Metab 1389, 76–80. 10.1016/S0005-2760(97)00128-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banfic H, Zizak M, Divecha N, Irvine RF, 1993. Nuclear diacylglycerol is increased during cell proliferation in vivo, Biochemical Journal. 10.1042/bj2900633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge MJ, 2007. Calcium signalling, a spatiotemporal phenomenon, in: New Comprehensive Biochemistry. pp. 485–502. 10.1016/S0167-7306(06)41019-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bertagnolo V, Mazzoni M, Ricci D, Carini C, Neri LM, Previati M, Capitani S, 1995. Identification of PI-PLC β1, γ1, and δ1 in rat liver: Subcellular distribution and relationship to inositol lipid nuclear signalling. Cell. Signal 7, 669–678. 10.1016/0898-6568(95)00036-O [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezin S, Fossier P, Cancela J-M, 2008. Nucleoplasmic reticulum is not essential in nuclear calcium signalling mediated by cyclic ADPribose in primary neurons. Pflügers Arch. - Eur. J. Physiol 456, 581–586. 10.1007/s00424-007-0435-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boronenkov IV, Loijens JC, Umeda M, Anderson RA, 1998. Phosphoinositide signaling pathways in nuclei are associated with nuclear speckles containing pre-mRNA processing factors. Mol. Biol. Cell 9, 3547–60. 10.1091/mbc.9.12.3547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgeois CA, Hemon D, Bouteille M, 1979. Structural relationship between the nucleolus and the nuclear envelope. J. Ultrastruct. Res 68, 328–340. 10.1016/S0022-5320(79)90165-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgoyne RD, Cheek TR, Morgan A, O’Sullivan AJ, Moreton RB, Berridge MJ, Mata AM, Colyer J, Lee AG, East JM, 1989. Distribution of two distinct Ca2+-ATPase-like proteins and their relationships to the agonist-sensitive calcium store in adrenal chromaff in cells. Nature 342, 72–74. 10.1038/342072a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussolati G, Marchiò C, Gaetano L, Lupo R, Sapino A, 2007. Pleomorphism of the nuclear envelope in breast cancer: a new approach to an old problem. J. Cell. Mol. Med 12, 209–218. 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2007.00176.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi K, Kim H, Lee S, Moon K, Sim S, Kim J, Chung H, Rhee S, 1990. Molecular cloning and expression of a complementary DNA for inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate 3-kinase. Science (80-.). 248, 64–66. 10.1126/science.2157285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke JH, Letcher AJ, D’santos CS, Halstead JR, Irvine RF, Divecha N, 2001. Inositol lipids are regulated during cell cycle progression in the nuclei of murine erythroleukaemia cells, Biochem. J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocco L, Gilmour RS, Ognibene A, Letcher AJ, Manzoli FA, Irvine RF, 1987. Synthesis of polyphosphoinositides in nuclei of Friend cells. Evidence for polyphosphoinositide metabolism inside the nucleus which changes with cell differentiation. Biochem. J 248, 765–70. 10.1042/bj2480765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocco L, Rubbini S, Manzoli L, Billi AM, Faenza I, Peruzzi D, Matteucci A, Artico M, Gilmour RS, Rhee SG, 1999. Inositides in the nucleus: presence and characterisation of the isozymes of phospholipase β family in NIH 3T3 cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 1438, 295–299. 10.1016/S1388-1981(99)00061-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Miranda MC, Rodrigues MA, De Angelis Campos AC, Faria JAQA, Kunrath-Lima M, Mignery GA, Schechtman D, Goes AM, Nathanson MH, Gomes DA, 2019. Epidermal growth factor (EGF) triggers nuclear calcium signaling through the intranuclear phospholipase Cδ−4 (PLCδ4). J. Biol. Chem 294, 16650–16662. 10.1074/jbc.RA118.006961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Divecha N, Banfic H, Farvine R, Banfić H, Irvine RF, 1991. The polyphosphoinositide cycle exists in the nuclei of Swiss 3T3 cells under the control of a receptor (for IGF-I) in the plasma membrane, and stimulation of the cycle increases nuclear diacylglycerol and apparently induces translocation of protein kinase. EMBO J. 10, 3207–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echevarria W, Leite MF, Guerra MT, Zipfel WR, Nathanson MH, 2003. Regulation of calcium signals in the nucleus by a nucleoplasmic reticulum. Nat Cell Biol 5, 440–446. 10.1038/ncb980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faenza I, Bavelloni A, Fiume R, Lattanzi G, Maraldi NM, Gilmour RS, Martelli AM, Suh P-G, Billi AM, Cocco L, 2003. Up-regulation of nuclear PLCbeta1 in myogenic differentiation. J. Cell. Physiol 195, 446–52. 10.1002/jcp.10264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faenza I, Matteucci A, Manzoli L, Billi AM, Aluigi M, Peruzzi D, Vitale M, Castorina S, Suh P-G, Cocco L, 2000. A Role for Nuclear Phospholipase C 1 in Cell Cycle Control*. 10.1074/jbc.M004630200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson BJ, Dovey CL, Lilley K, Wyllie AH, Rich T, 2007. Nuclear phospholipase C gamma: Punctate distribution and association with the promyelocyte leukemia protein. J. Proteome Res. 6, 2027–2032. 10.1021/pr060684v [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiume R, Ramazzotti G, Teti G, Chiarini F, Faenza I, Mazzotti G, Billi AM, Cocco L, 2009. Involvement of nuclear PLCbeta1 in lamin B1 phosphorylation and G2/M cell cycle progression. FASEB J 23, 957–966. 10.1096/fj.08-121244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fricker Mark, Hollinshead M, White N, Vaux D, 1997. Interphase Nuclei of Many Mammalian Cell Types Contain Deep, Dynamic, Tubular Membrane-bound Invaginations of the Nuclear Envelope. J. Cell Biol 136, 531–544. 10.1083/jcb.136.3.531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fricker M, Hollinshead M, White N, Vaux D, 1997. The convoluted nucleus. Trends Cell Biol. 7, 181. 10.1016/S0962-8924(97)84084-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukami K, Takenaka K, Nagano K, Takenawa T, 2000. Growth factor-induced promoter activation of murine phospholipase C δ4 gene. Eur. J. Biochem 267, 28–36. 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.00943.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner MH, 2002. Na,K-ATPase in the nuclear envelope regulates Na+: K+ gradients in hepatocyte nuclei. J. Membr. Biol 187, 97–115. 10.1007/s00232-001-0155-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerasimenko JV, Maruyama Y, Yano K, Dolman NJ, Tepikin AV, Petersen OH, Gerasimenko OV, 2003. NAADP mobilizes Ca2+ from a thapsigargin-sensitive store in the nuclear envelope by activating ryanodine receptors. J. Cell Biol 163, 271–282. 10.1083/jcb.200306134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerasimenko OV, Gerasimenko JV, Tepikin AV, Petersen OH, 1995. ATP-dependent accumulation and inositol trisphosphate- or cyclic ADP-ribose-mediated release of Ca2+ from the nuclear envelope. Cell 80, 439–444. 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90494-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes D. a, Rodrigues MA, Leite MF, Gomez MV, Varnai P, Balla T, Bennett AM, Nathanson MH, 2008. c-Met must translocate to the nucleus to initiate calcium signals. J. Biol. Chem 283, 4344–51. 10.1074/jbc.M706550200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes DA, Leite MF, Bennett AM, Nathanson MH, 2006. Calcium signaling in the nucleus. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol 84, 325–32. 10.1139/y05-117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Güttinger S, Laurell E, Kutay U, 2009. Orchestrating nuclear envelope disassembly and reassembly during mitosis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 10, 178–191. 10.1038/nrm2641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardingham GE, Chawla S, Johnson CM, Bading H, 1997. Distinct functions of nuclear and cytoplasmic calcium in the control of gene expression. Nature 385, 260–265. 10.1038/385260a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huh YH, Yoo SH, 2003. Presence of the inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate receptor isoforms in the nucleoplasm. FEBS Lett. 555, 411–418. 10.1016/S0014-5793(03)01273-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humbert J-PP, Matte N, Artault J-CC, Köppler P, Malviya AN, Matter N, Artault J-CC, Kö P, Malviya AN, 1996. Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor is located to the inner nuclear membrane vindicating regulation of nuclear calcium signaling by inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate: Discrete distribution of inositol phosphate receptors to inner and outer nuclear membranes. J. Biol. Chem 271, 478–485. 10.1074/jbc.271.1.478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim CG, Park D, Rhee SG, 1996. The Role of Carboxyl-terminal Basic Amino Acids in G q α-dependent Activation, Particulate Association, and Nuclear Localization of Phospholipase C-β1. J. Biol. Chem 271, 21187–21192. 10.1074/jbc.271.35.21187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein C, Gensburger C, Freyermuth S, Nair BC, Labourdette G, Malviya AN, 2004. A 120 kDa nuclear phospholipase Cγ1 protein fragment is stimulated in vivo by EGF signal phosphorylating nuclear membrane EGFR. Biochemistry 43, 15873–15883. 10.1021/bi048604t [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koppler P, Matter N, Malviya AN, 1993. Evidence for stereospecific inositol 1,3,4,5-[3H]tetrakisphosphate binding sites on rat liver nuclei. Delineating inositol 1,3,4,5-tetrakisphosphate interaction in nuclear calcium signaling process. J. Biol. Chem 268, 26248–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köppler P, Mersel M, Humbert J-PP, Vignon J, Vincendon G, Malviya AN, 1996. High Affinity Inositol 1,3,4,5-Tetrakisphosphate Receptor from Rat Liver Nuclei: Purification, Characterization, and Amino-Terminal Sequence †. Biochemistry 35, 5481–5487. 10.1021/bi9522918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulikova OG, Savost’ianov GA, Beliavtseva LM, Razumovskaia NI, 1982. ATPase activity and ATP-dependent accumulation of Ca2+ in skeletal muscle nuclei. Effects of denervation and electric stimulation. Biokhimiya 47, 1216–1221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunrath-Lima M, de Miranda MC, Ferreira A. da F., Faraco CCF, de Melo MIA, Goes AM, Rodrigues MA, Faria JAQA, Gomes DA, 2018. Phospholipase C delta 4 (PLCδ4) is a nuclear protein involved in cell proliferation and senescence in mesenchymal stromal stem cells. Cell. Signal 49, 59–67. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2018.05.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langevin HM, Storch KN, Snapp RR, Bouffard NA, Badger GJ, Howe AK, Taatjes DJ, 2010. Tissue stretch induces nuclear remodeling in connective tissue fibroblasts. Histochem. Cell Biol 133, 405–415. 10.1007/s00418-010-0680-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanini L, Bachs O, Carafoli E, 1992. The calcium pump of the liver nuclear membrane is identical to that of endoplasmic reticulum. J. Biol. Chem 267, 11548–11552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Ji S, Shrestha C, Jiang Y, Liao L, Xu F, Liu Z, Bikle DD, Xie Z, 2020. p120-catenin suppresses proliferation and tumor growth of oral squamous cell carcinoma via inhibiting nuclear phospholipase C-γ1 signaling. J. Cell. Physiol jcp.29744. 10.1002/jcp.29744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu N, Fukami K, Yu H, Takenawa T, 1996. A new phospholipase C delta 4 is induced at S-phase of the cell cycle and appears in the nucleus. J Biol Chem 271, 355–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo Vasco VR, Calabrese G, Manzoli L, Palka G, Spadano A, Morizio E, Guanciali-Franchi P, Fantasia D, Cocco L, 2004. Inositide-specific phospholipase c beta1 gene deletion in the progression of myelodysplastic syndrome to acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia 18, 1122–6. 10.1038/sj.leu.2403368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukinovic-Skudar V, Matkovic K, Banfic H, Visnjic D, 2007. Two waves of the nuclear phospholipase C activity in serum-stimulated HL-60 cells during G(1) phase of the cell cycle. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1771, 514–21. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2007.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukinoviƈ-Škudar V, Đonlagiƈ L, Banfíƈ H, Višnjiƈ D, 2005. Nuclear phospholipase C-β1b activation during G2/M and late G1 phase in nocodazole-synchronized HL-60 cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 1733, 148–156. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2004.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhas A, Goulbourne C, Vaux DJ, 2011. The nucleoplasmic reticulum: form and function. Trends Cell Biol. 21, 362–73. 10.1016/j.tcb.2011.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhas AN, Vaux DJ, 2014. Nuclear Envelope Invaginations and Cancer. pp. 523–535. 10.1007/978-1-4899-8032-8_24 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Malviya AN, Klein C, 2006. Mechanism regulating nuclear calcium signalingThis paper is one of a selection of papers published in this Special Issue, entitled The Nucleus: A Cell Within A Cell. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol 84, 403–422. 10.1139/y05-130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzoli L, Billi AM, Rubbini S, Bavelloni A, Faenza I, Gilmour RS, Rhee SG, Cocco L, 1997. Essential role for nuclear phospholipase C beta1 in insulin-like growth factor I-induced mitogenesis. Cancer Res 57, 2137–2139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marius P, Guerra MT, Nathanson MH, Ehrlich BE, Leite MF, 2006. Calcium release from ryanodine receptors in the nucleoplasmic reticulum. Cell Calcium 39, 65–73. 10.1016/j.ceca.2005.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmiroli S, Ognibenell A, Bavelloni A, Cinti C, Cocco L, Maraldi NM, 1994. Interleukin 1α stimulates nuclear phospholipase C in human osteosarcoma saOS-2 cells. J. Biol. Chem 269, 13–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martelli AM, Falà F, Faenza I, Billi AM, Cappellini A, Manzoli L, Cocco L, 2004. Metabolism and signaling activities of nuclear lipids. Cell. Mol. Life Sci 61, 1143–56. 10.1007/s00018-004-3414-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martelli AM, Gilmour RS, Bertagnolo V, Neri LM, Manzoli L, Cocco L, 1992. Nuclear localization and signalling activity of phosphoinositidase Cβ in Swiss 3T3 cells. Nature 358, 242–245. 10.1038/358242a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzoni M, Bertagnolo V, Neri LM, Carini C, Marchisio M, Milani D, Manzoli FA, Capitani S, 1992. Discrete subcellular localization of phosphoinositidase C β, γ and δ in PC12 rat pheochromocytoma cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 187, 114–120. 10.1016/S0006-291X(05)81466-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura Y, Fukami K, 2017. Regulation and physiological functions of mammalian phospholipase C. J. Biochem 161, mvw094. 10.1093/jb/mvw094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicotera P, Orrenius S, Nilsson T, Berggren PO, 1990. An inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-sensitive Ca2+ pool in liver nuclei. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 87, 6858–6862. 10.1073/pnas.87.17.6858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada M, Fujii M, Yamaga M, Sugimoto H, Sadano H, Osumi T, Kamata H, Hirata H, Yagisawa H, 2002. Carboxyl-terminal basic amino acids in the X domain are essential for the nuclear import of phospholipase C δ 1. Genes to Cells 7, 985–996. 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2002.00577.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada M, Ishimoto T, Naito Y, Hirata H, Yagisawa H, 2005. Phospholipase Cδ 1 associates with importin β1 and translocates into the nucleus in a Ca 2+-dependent manner. FEBS Lett. 579, 4949–4954. 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.07.082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada M, Taguchi K, Maekawa S, Fukami K, Yagisawa H, 2010. Calcium fluxes cause nuclear shrinkage and the translocation of phospholipase C-δ1 into the nucleus. Neurosci. Lett. 472, 188–193. 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.01.081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne SL, Thomas CL, Gschmeissner S, Schiavo G, 2001. Nuclear PtdIns(4,5)P2 assembles in a mitotically regulated particle involved in pre-mRNA splicing. J. Cell Sci 114, 2501–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philipson KD, Nicoll DA, 2000. Sodium-Calcium Exchange: A Molecular Perspective. Annu. Rev. Physiol 62, 111–133. 10.1146/annurev.physiol.62.1.111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prole DL, Taylor CW, 2016. Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors and their protein partners as signalling hubs. J. Physiol 594, 2849–2866. 10.1113/JP271139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues MA, Gomes DA, Andrade VA, Leite MF, Nathanson MH, 2008. Insulin induces calcium signals in the nucleus of rat hepatocytes. Hepatology. 10.1002/hep.22424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues MA, Gomes DA, Leite MF, Grant W, Zhang L, Lam W, Cheng Y-C, Bennett AM, Nathanson MH, 2007. Nucleoplasmic calcium is required for cell proliferation. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 17061–8. 10.1074/jbc.M700490200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogue PJ, Humbert J-P, Meyer A, Freyermuth S, Krady M-M, Malviya AN, 1998. cAMP-dependent protein kinase phosphorylates and activates nuclear Ca 2-ATPase, Biochemistry. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross CA, Meldolesi J, Milner TA, Satoh T, Supattapone S, Snyder H, S., 1989. Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor localized to endoplasmic reticulum in cerebellar Purkinje neurons. Nature 339, 468–470. 10.1038/339468a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santella L, Kyozuka K, 1997. Effects of 1-methyladenine on nuclear Ca2+ transients and meiosis resumption in starfish oocytes are mimicked by the nuclear injection of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate and cADP-ribose. Cell Calcium 22, 11–20. 10.1016/S0143-4160(97)90085-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santi P, Marmiroli S, Falcieri E, Bertagnolo V, Capitani S, 1994. Inositol lipid phosphorylation and breakdown in rat liver nuclei is affected by hydrocortisone blood levels. Cell Biochem. Funct 12, 201–207. 10.1002/cbf.290120308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoen I, Aires L, Ries J, Vogel V, 2017. Nanoscale invaginations of the nuclear envelope: Shedding new light on wormholes with elusive function. 10.1080/19491034.2017.1337621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Secondo A, Petrozziello T, Tedeschi V, Boscia F, Pannaccione A, Molinaro P, Annunziato L, 2020. Nuclear localization of NCX: Role in Ca2+ handling and pathophysiological implications. Cell Calcium 86, 102143. 10.1016/j.ceca.2019.102143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CD, Wells WW, 1983. Phosphorylation of rat liver nuclear envelopes. II. Characterization of in vitro lipid phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem 258, 9368–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stallings JD, Tall EG, Pentyala S, Rebecchi MJ, 2005. Nuclear Translocation of Phospholipase C-δ1 Is Linked to the Cell Cycle and Nuclear Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-Bisphosphate. J. Biol. Chem 280, 22060–22069. 10.1074/jbc.M413813200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stallings JD, Zeng YX, Narvaez F, Rebecchi MJ, 2008. Phospholipase C-δ1 Expression Is Linked to Proliferation, DNA Synthesis, and Cyclin E Levels. J. Biol. Chem 283, 13992–14001. 10.1074/jbc.M800752200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch KN, Taatjes DJ, Bouffard NA, Locknar S, Bishop NM, Langevin HM, 2007. Alpha smooth muscle actin distribution in cytoplasm and nuclear invaginations of connective tissue fibroblasts. Histochem. Cell Biol 127, 523–530. 10.1007/s00418-007-0275-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian K, Meyer T, 1997. Calcium-Induced Restructuring of Nuclear Envelope and Endoplasmic Reticulum Calcium Stores. Cell 89, 963–971. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80281-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun B, Murray NR, Fields AP, 1997. A role for nuclear phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C in the G2/M phase transition. J. Biol. Chem 272, 26313–26317. 10.1074/jbc.272.42.26313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabellini G, 2003. Diacylglycerol kinase-θ is localized in the speckle domains of the nucleus. Exp. Cell Res. 287, 143–154. 10.1016/S0014-4827(03)00115-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueasilamongkol P, Khamphaya T, Guerra MT, Rodrigues MA, Gomes DA, Kong Y, Wei W, Jain D, Trampert DC, Ananthanarayanan M, Banales JM, Roberts LR, Farshidfar F, Nathanson MH, Weerachayaphorn J, 2020. Type 3 Inositol 1,4,5-Trisphosphate Receptor Is Increased and Enhances Malignant Properties in Cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatology 71, 583–599. 10.1002/hep.30839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandecaetsbeek I, Vangheluwe P, Raeymaekers L, Wuytack F, Vanoevelen J, 2011. The Ca2+ Pumps of the Endoplasmic Reticulum and Golgi Apparatus. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol 3, 1–24. 10.1101/cshperspect.a004184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G, Lu ZH, Wang J, Wang Y, Xie X, Meyenhofer MF, Ledeen RW, 2005. Enhanced susceptibility to kainate-induced seizures, neuronal apoptosis, and death in mice lacking gangliotetraose gangliosides: Protection with LIGA 20, a membrane-permeant analog of GM1. J. Neurosci 25, 11014–11022. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3635-05.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie X, Wu G, Lu Z-H, Ledeen RW, 2002. Potentiation of a sodium-calcium exchanger in the nuclear envelope by nuclear GM1 ganglioside. J. Neurochem 81, 1185–1195. 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.00917.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu A, Suh P, Marmy-Conus N, Pearson RB, Seok OY, Cocco L, Stewart Gilmour AR, Gilmour RS, 2001. Phosphorylation of Nuclear Phospholipase C β1 by Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase Mediates the Mitogenic Action of Insulin-Like Growth Factor I. Mol. Cell. Biol 21, 2981–2990. 10.1128/MCB.21.9.2981-2990.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagisawa H, 2006. Nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of phospholipase C-delta1: a link to Ca2+. J. Cell. Biochem 97, 233–43. 10.1002/jcb.20677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagisawa H, Okada M, Naito Y, Sasaki K, Yamaga M, Fujii M, 2006. Coordinated intracellular translocation of phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C-δ with the cell cycle. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 1761, 522–534. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye K, Aghdasi B, Luo HR, Moriarity JL, Wu FY, Hong JJ, Joseph Hurt K, Sik Bae S, Suh PG, Snyder SH, 2002. Phospholipase Cγ1 is a physiological guanine nucleotide exchange factor for the nuclear GTPase PIKE. Nature 415, 541–544. 10.1038/415541a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo SH, Nam SW, Huh SK, Park SY, Huh YH, 2005. Presence of a nucleoplasmic complex composed of the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor/Ca2+ channel, chromogranin B, and phospholipids. Biochemistry 44, 9246–9254. 10.1021/bi047427t [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]