SUMMARY

About half of the world’s population and 80% of the world’s biodiversity can be found in the tropics. Many diseases are specific to the tropics, with at least 41 diseases caused by endemic bacteria, viruses, parasites, and fungi. Such diseases are of increasing concern, as the geographic range of tropical diseases is expanding due to climate change, urbanization, change in agricultural practices, deforestation, and loss of biodiversity. While traditional medicines have been used for centuries in the treatment of tropical diseases, the active natural compounds within these medicines remain largely unknown. In this review, we describe infectious diseases specific to the tropics, including their causative pathogens, modes of transmission, recent major outbreaks, and geographic locations. We further review current treatments for these tropical diseases, carefully consider the biodiscovery potential of the tropical biome, and discuss a range of technologies being used for drug development from natural resources. We provide a list of natural products with antimicrobial activity, detailing the source organisms and their effectiveness as treatment. We discuss how technological advancements, such as next-generation sequencing, are driving high-throughput natural product screening pipelines to identify compounds with therapeutic properties. This review demonstrates the impact natural products from the vast tropical biome have in the treatment of tropical infectious diseases and how high-throughput technical capacity will accelerate this discovery process.

KEYWORDS: drug development, infectious disease, microbiology, natural products, tropics

INTRODUCTION

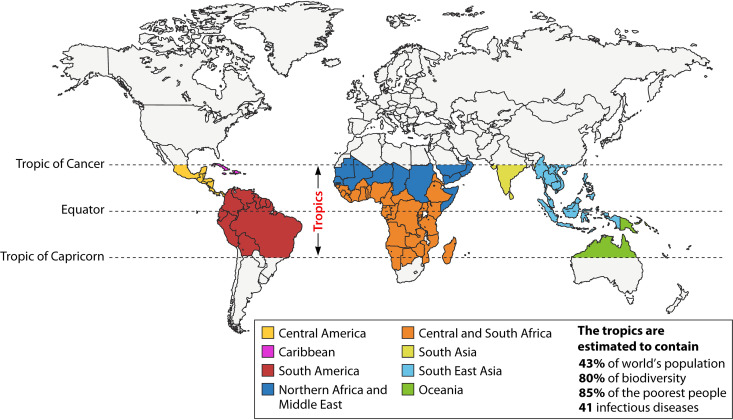

The tropics occupy a large area of the Earth’s landmass from the Tropic of Cancer to the Tropic of Capricorn (Fig. 1). Tropical diseases are caused by a wide variety of pathogens, including bacteria, viruses, parasites, and fungi, that spread through various modes of transmission. The WHO defines 41 different tropical diseases, of which 21 are classified as neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) (Table 1). Traditional medicines have been used for centuries for the treatment of tropical diseases (1). Products of plants such as Cinchona and Artemisia are effectively used even today for the treatment of malaria (2). Plants are a promising source of traditional medicines, as many plants are safe with few side effects even when taken orally for prolonged periods. The long history of screening plant species by humans over millennia has led to deep-rooted knowledge of many plants that are beneficial when used correctly. Plants are also affordable and generally do not require cold-chain storage (3). The WHO has established its Traditional Medicine Strategy, which has guidelines for the assessment of herbal medicines (4). However, the active compounds of many such medicines have not been identified. Despite the encouraging identification of the neuropathic pain drug ω-conotoxin from the marine snail Conus magus in 1999 (5), the majority of plant and animal products have not yet been systematically investigated.

FIG 1.

World map showing tropical regions. The geographical area between the Tropic of Cancer and the Tropic of Capricorn defines the tropics and occupies a large area of the Earth’s landmass and oceans. The tropics span 5 continents and are home to 43% of the world’s population, 80% of the biodiversity, 85% of the poorest people, and 41 infectious diseases. (Adapted from reference 243 with permission of the publisher.)

TABLE 1.

Tropical infectious diseases

| Organism type | Disease | NTDa | Pathogen(s) | Transmission | Location(s) of ongoing/recent major outbreaksb | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterium | Buruli ulcer (Bairnsdale ulcer, Daintree ulcer) | * | Mycobacterium ulcerans | Unclear (evidence for cutaneous contamination from infected aquatic insects, Naucoris spp. and Dyplonychus spp., and bite of infected mosquitoes) | NA | 27 |

| Cholera | Vibrio cholerae | Ingestion of contaminated food/water | 2018: Algeria, Niger, Zimbabwe 2017: DRC, Kenya, Mozambique, Somalia, Zambia 2016: Yemen 2015: DRC, Iraq, Tanzania |

15 | ||

| Leprosy (Hansen's disease) | * | Mycobacterium leprae | Unclear (evidence for contamination through skin-to-skin contact with an infected individual and inhalation of contaminated droplets) | NA | 26 | |

| Melioidosis | Burkholderia pseudomallei | Ingestion, inhalation of contaminated dust/water Contact with contaminated soil |

NA | 244 | ||

| Mycetoma (actinomycetoma) | * | Streptomyces somaliensis, Nocardia brasiliensis, Nocardia otitidiscaviarum, Actinomadura madurae, Actinomadura pelletieri, Pleurostomophora ochracea | Contact of epithelia with contaminated soil or water | NA | 245 | |

| Trachoma | * | Chlamydia trachomatis | Direct or indirect (shared towels and clothes, flies) contact with eye or nose discharge of an infected individual | NA | 246 | |

| Tuberculosis | Mycobacterium tuberculosis | Inhalation of contaminated droplets | NA | 12 | ||

| Yaws | * | Treponema pallidum pertenue | Skin-to-skin contact with an infected individual | 2019: Ghana 2017: Cameroon |

NA | |

| African trypanosomiasis (African sleeping sickness) | * | Trypanosoma brucei gambiense, Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense | Bite of an infected tsetse fly (Glossina spp.) | NA | 22 | |

| American trypanosomiasis (Chagas disease) | * | Trypanosoma cruzi | Bite of infected triatomine bug (Triatoma spp., Rhodnius spp.) Ingestion of contaminated food In utero transmission |

NA | 19 | |

| Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) | * | Dracunculus medinensis | Ingestion of water contaminated with infected copepods | 2020: Ethiopia 2019: Angola, Cameroon, Chad 2018: Angola, Chad, RSS 2017: Chad, Ethiopia 2016: Chad, Ethiopia, RSS 2015: Chad, Ethiopia, Mali, RSS |

NA | |

| Echinococcosis | * | Echinococcus granulosus, E. multilocularis, E. vogeli, E. oligarthrus | Ingestion of contaminated food/water/soil | NA | 16 | |

| Parasite | Foodborne trematodiases | * | Liver flukes (Clonorchis sinensis, Fasciola gigantica, F. hepatica, Opisthorchis felineus, O. viverrini) Lung flukes (Paragonimus spp.) Intestinal flukes (Echinostoma spp., Fasciolopsis buski) |

Ingestion of contaminated food | NA | 247 |

| Leishmaniasis | * | Leishmania spp. | Bite of an infected sand fly (Phlebotomus spp., Lutzomyia spp.) | 2019: Kenya 2018: Libya 2017: Kenya |

248 | |

| Lymphatic filariasis | * | Wuchereria bancrofti, Brugia malayi, B. timori | Bite of an infected female mosquito (Anopheles spp.) | NA | NA | |

| Malaria | Plasmodium falciparum, P. vivax, P. ovale, P. knowlesi, P. malariae | Bite of an infected mosquito (Anopheles spp., Culex spp., Aedes spp., Mansonia spp.) | 2020: Vanuatu, Zimbabwe 2019: Burundi (249), Sudan 2018: Brazil 2017: Cape Verde, Costa Rica |

20 | ||

| Onchocerciasis | * | Onchocerca volvulus | Bite of an infected black fly (Simulium spp.) | NA | NA | |

| Scabies | * | Sarcoptes scabiei var. hominis | Skin-to-skin contact with an infected individual | NA | 13 | |

| Schistosomiasis | * | Schistosoma mansoni, S. japonicum, S. mekongi, S. guineensis, S. haematobium | Contact with contaminated water | NA | 250 | |

| Soil-transmitted helminth (STH) infections | * | Ancylostoma duodenale, Necator americanus, Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura | Contact with contaminated soil | NA | NA | |

| Strongyloidiasis | Strongyloides stercoralis | Contact with contaminated soil | NA | 251 | ||

| Taeniasis, cysticercosis | * | Taenia solium, T. saginita, T. asiatica | Ingestion of raw or undercooked infected beef or pork meat | NA | 252 | |

| Virus | Chikungunya | * | Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) | Bite of an infected female mosquito (Aedes spp.) | 2019: DRC 2018: Sudan 2017: Italy, Kenya, France 2016: Argentina, Kenya 2015: Senegal |

21 |

| Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever | Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus (CCHFV) | Bite of an infected tick (Hyalomma spp.) Contact with body fluids/tissues of infected livestock Contact with body fluids of an infected individual |

2020: Mali | 17 | ||

| Dengue | * | Dengue virus (DENV) | Bite of an infected female mosquito (Aedes aegypti) | 2020: Chile, Costa Rica, Indonesia, Peru, Singapore 2019: Afghanistan, Bangladesh (253), French Polynesia (254), Jamaica, Mayotte, Pakistan, Sudan 2018: Réunion Island 2017: Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Sri Lanka, Sudan 2016: Uruguay 2015: Egypt |

18 | |

| Ebola hemorrhagic fever | Ebola virus (EBOV) | Contact with an infected animal (e.g., fruit bat or nonhuman primate) Contact with body fluids of an EBOV-infected individual or dead body Contact with contaminated objects (e.g., clothes, bedding, needles, and medical equipment) Sexual transmission from semen of men who have recovered from EBOV infection |

2020: DRC 2019: Uganda 2018: DRC 2017: DRC 2013–2016: West Africac |

14 | ||

| Japanese encephalitis | Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) | Bites of an infected mosquito (Aedes spp., Anopheles spp., Culex spp., Mansonia spp.) | NA | 255 | ||

| Lassa fever | Lassa virus | Contact with urine or feces of Mastomys natalensis rats (handling rats, eating contaminated food, touching contaminated household items, transepithelial contamination) Contact with body fluids of an infected individual |

2020: Nigeria 2019: Nigeria 2018: Nigeria 2017: Nigeria 2016: Benin, Nigeria |

NA | ||

| Marburg hemorrhagic fever | Marburg virus (MARV) | Contact with an infected fruit bat (Rousettus aegyptiacus) Contact with body fluids of an infected individual |

2017: Uganda | 256 | ||

| Rabies | * | Rabies virus | Transcutaneous contamination with saliva of infected animals (e.g., bats, dogs) | 2016: Bhutan (257) | 258 | |

| Rift Valley fever | Rift Valley fever virus (RVFV) | Bite of an infected mosquito (Anopheles spp., Culex spp., Aedes spp., Mansonia spp.) Contact with body fluids/tissues of infected livestock |

2018: Kenya, Mayotte 2016: Niger 2015: Mauritania (259) |

260 | ||

| Tick-borne encephalitis | Tick-borne encephalitis virus (TBEV) | Bite of an infected tick (Ixodidae spp.) Ingestion of raw milk from infected goats/sheep/cows |

NA | 261 | ||

| West Nile fever | West Nile virus (WNV) | Bites of an infected mosquito (Culex spp.) Contact with body fluids/tissues of infected animals In utero transmission |

NA | 262 | ||

| Yellow fever | Yellow fever virus (YFV) | Bite of an infected female mosquito (Aedes spp., Haemogogus spp.) | 2020: Ethiopia, Uganda 2019: Mali 2018: Ethiopia, RSS 2017: Brazil, Nigeria 2016: Angola, Brazil, DRC, Uganda |

263 | ||

| Zika | Zika virus (ZIKV) | Bite of an infected female mosquito (Aedes spp.) In utero transmission Contact with genital fluids of an infected individual |

2015: Region of the Americas and othersd | 23 | ||

| Fungus | Chromoblastomycosis | * | Phialophora verrucosa, Fonsecaea pedrosoi, F. compacta, Cladophialophora carrionii, Rhinocladiella aquaspersa | Unclear (evidence for transcutaneous contamination) | NA | 264 |

| Lobomycosis (lacaziosis) | Lacazia loboi | Unclear (evidence for transcutaneous contamination) | NA | 25 | ||

| Paracoccidioidomycosis | Paracoccidioides brasiliensis | Inhalation of spores | 2015: Brazil (35) | 265 | ||

| Mycetoma (eumycetoma) | * | Madurella mycetomatis, Curvularia lunata, Falciformispora senegalensis, Falciformispora thompkinsii, Trematosphaeria grisea, Exophiala jeanselmei, Medicopsis romeroi, Acremonium spp., Fusarium spp., Neotestudina rosatii, Aspergillus nidulans, A. flavus, Microsporum ferrugineum, M. audouinii, M. langeronii, Scedosporium apiospermum, S. boydii | Contact of epithelia with contaminated soil or water | NA | 245 | |

| Rhinosporidiosis | Rhinosporidium seeberi | Unclear (evidence for transepithelial contamination following contact with stagnant water) | NA | 24 | ||

| Sporotrichosis | Sporothrix schenckii | Transcutaneous inoculation from contaminated plant matter and infected cats Inhalation or ingestion of spores |

NA | 266 | ||

| Talaromycosis (penicilliosis marneffei) | Talaromyces marneffei | Transcutaneous inoculation from contaminated plant matter Inhalation or ingestion of spores |

NA | 267 |

NTD, neglected tropical disease (indicated by asterisk).

Recent and ongoing major outbreaks reported at https://www.cdc.gov, https://www.afro.who.int (WHO Regional Office for Africa), https://www.emro.who.int (WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean), https://www.paho.org (WHO Regional Office for the Americas), and https://www.who.int, unless otherwise stated, over the last 5 years. The date indicates the start of the outbreak. DRC, Democratic Republic of the Congo; RSS, Republic of South Sudan; NA, not applicable.

West Africa includes Guinea, Liberia, Mali, Nigeria, Senegal, and Sierra Leone.

Region of the Americas and others includes Bolivia, Brazil, Cape Verde, Caribbean Islands (Aruba, Barbados, Bonaire, Cuba, Curaçao, Dominica, Dominican Republic, Grenadines, Guadeloupe, Haiti, Jamaica, Martinique Island, Puerto Rico, Saint Lucia, Saint Martin, Saint Vincent, Trinidad and Tobago, U.S. Virgin Islands), Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, El Salvador, French Guiana, Guatemala, Guyana, Honduras, Maldives, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Suriname, Venezuela, and Vietnam.

Natural products often possess a high degree of bioavailability in comparison to their synthetic counterparts (6). Therefore, it is surprising that not more natural product-based drug candidates have been identified. It is important to reflect upon this, given the recent technical advances used for the screening of natural products. Typically, it takes about 10 years and US$300 million to US$500 million in research and development (R&D) expenditure for a new product to be released into the market (7). Therefore, many pharmaceutical companies are unenthusiastic about developing drugs for tropical diseases that are primarily targeted to emerging economies of low- and middle-income countries. However, recent technological advances have made the process time efficient and cost-effective, providing an unprecedented opportunity for researchers and pharmaceutical companies to identify novel bioactive leads for commercialization (6, 8). About 50% of known plant species are thought to originate in the tropics, and one-third of those used in R&D are found in rainforests; therefore, an important opportunity also awaits developing economies of the tropics. With increasing pressure from climate change and deforestation on biodiversity, it is important for developing nations to consider both the protection of intellectual property rights of traditional knowledge holders and the overall conservation and sustainable use of medicinal plants (6). Pragmatic ways that provide access to modern health care while incorporating these considerations are urgently needed.

In this review, we describe tropical infectious diseases, the pathogens causing them, their modes of transmission, recent major outbreaks, and their geographic locations. We further detail current preventative and therapeutic treatments for tropical diseases, including any commercially licensed vaccines and promising vaccine candidates under investigation. We discuss a range of new technologies that are used for natural product discovery and drug development from natural resources focusing on high-throughput screens (HTS) and omics technologies. Finally, we discuss both approved natural products and molecules used to treat tropical diseases and additional natural products possessing antimicrobial activity with treatment potential. We hope our review will revitalize interest in natural products and drug discovery and encourage more researchers and companies to utilize recent technological advancements made.

INFECTIOUS DISEASES OF THE TROPICS

The WHO defines tropical diseases as all diseases that occur solely or principally in the tropics (Fig. 1) (9). However, this umbrella term often also includes any infectious disease that occurs in hot and humid climate. Tropical diseases are an enormous public health burden, with an estimated 1 billion people affected by at least one tropical disease, representing a significant impact on the health of people living in the tropical and subtropical regions of the world (10) (Fig. 1). Tropical diseases, including neglected tropical diseases (NTDs), are caused by a wide variety of pathogens, including bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites (Table 1). NTDs receive less attention from the scientific community and stakeholders of the developed countries than other tropical diseases (11). To address this shortcoming, multiple local and global nonprofit organizations such as Mission to Save the Helpless (MITOSATH, Nigeria) and the Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative (DNDi, Switzerland) have been established to improve the health and enhance the quality of life of people affected by NTDs. The tropical diseases encompassed by these definitions are changing, with the WHO recently updating their NTD portfolio to include mycetoma, chromoblastomycosis, and scabies (69th World Health Assembly, 2016; 10th Meeting of the Strategic and Technical Advisory Group for Neglected Tropical Diseases, 2017).

Tropical diseases spread through various modes of transmission (Table 1). They can be transmitted via direct or indirect contact with infected individuals through bodily fluids or surfaces (e.g., yaws, scabies, Ebola), as well as by the inhalation of contaminated airborne droplets (e.g., tuberculosis [TB]) (12–14). Transmission may also occur by ingesting contaminated food and/or water (e.g., cholera and echinococcosis) in unsanitary environments, which persist in many tropical and subtropical countries today (15, 16). Many viral and parasitic tropical diseases are vector-borne, with transmission occurring through the bite of infected vectors, including hemipterans (Chagas disease), flies (e.g., African trypanosomiasis, leishmaniasis, onchocerciasis), mosquitoes (e.g., lymphatic filariasis, malaria, chikungunya, and dengue) and ticks (Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever) (17–22), among others. In utero transmission has also been reported for tropical diseases such as Zika virus and Chagas disease (19, 23). While the transmission mode is known for most tropical diseases, it remains unknown for Buruli ulcer and leprosy (both listed in the WHO NTD portfolio) as well as for some fungal infections, including chromoblastomycosis, lobomycosis, and rhinosporidiosis (24–27).

Many tropical diseases have recently been or are currently responsible for major outbreaks (e.g., dracunculiasis, leishmaniasis, malaria, chikungunya, dengue, Ebola, yellow fever, and paracoccidioidomycosis) (Table 1). Although most of these outbreaks occur within the tropics, some have occurred in countries with more temperate climates. For example, France and Italy have reported outbreaks of autochthonous chikungunya in 2015 and 2016, respectively (28, 29). Similarly, locally acquired cases of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever were reported in Spain in 2016 and 2018 (30). More recently, in 2019, France reported its first locally acquired case of Zika virus, which is also believed to be the first case recorded in Europe (31). While the number of total cases in each instance was relatively small (8 chikungunya cases in France, 436 chikungunya cases in Italy, 2 Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever cases in Spain, and 3 Zika cases in France), it illustrated the potential for such diseases in temperate climates. Such outbreaks outside the tropics highlight the potential risk for tropical diseases to spread globally; of particular concern are some of the vector-borne tropical diseases for which the competent vectors, including mosquitos, ticks, tsetse flies, and triatome bugs, are widely distributed around the world (28–32). Further, climate change, urbanization, change in agricultural practices, deforestation, and loss of biodiversity have all been implicated in increasing the potential spread of tropical diseases (33–36).

Immunization and treatment options differ widely across tropical diseases (Table 2). Currently, commercially licensed vaccines are available for only 8 of the 41 tropical diseases (cholera, TB, dengue, Ebola, Japanese encephalitis, rabies, tick-borne encephalitis, and yellow fever) (37–43), with licensing differing between countries. Many vaccine candidates are under investigation (Table 2) both for tropical diseases without any available licensed vaccine and for diseases with a current vaccine, such as TB. Indeed, the only available TB vaccine, bacillus Calmette-Guérin (Mycobacterium bovis BCG), provides partial protection in children but diminishes over time and is insufficient against pulmonary TB in adults (44). Although curative and/or symptomatic treatments are available for most tropical diseases, their practical efficacy remains challenged by a variety of technical, economic, and biological limitations (Table 2). With the exception of the WHO/UNICEF oral rehydration solution developed to treat cholera, the treatment of tropical diseases often relies on drugs that require strict storage conditions (45, 46). A cold chain is often unreliable or nonexistent for the tropical and subtropical regions, compromising the stability and treatment efficacy of the drugs. Additionally, the treatment of many tropical diseases may be negatively impacted by a lack of qualified health workers in the local community. For example, early intravenous injection is crucial in the treatment of many diseases (Table 2). Furthermore, access to treatment can also be impeded by the relatively high costs associated with effective drugs. For onchocerciasis and lymphatic filariasis, this economic hurdle has been overcome by the creation of the Mectizan (ivermectin) donation program (47). Finally, the global rise in antibiotic, antiparasitic, and antifungal resistance also represents a major threat to the successful treatment and management of tropical diseases (48). Unfortunately, for some tropical diseases such as dracunculiasis, lobomycosis, and rhinosporidiosis, there is currently no treatment or vaccine available, and physical extraction of the pathogens or surgical excision remains the only available option (Table 2). New treatment options are urgently needed, with discoveries from natural product platforms showing potential for the treatment and management of many tropical diseases.

TABLE 2.

Tropical infectious diseases: current treatments and vaccinesa

| Organism type | Disease | Current treatment(s) | Commercially licensed vaccine(s)b | Vaccine candidates under investigation [reference(s)] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterium | Buruli ulcer (Bairnsdale ulcer, Daintree ulcer) | Antibiotics: rifampin, clarithromycin, streptomycin Symptomatic treatment: wound care, lymphedema management, skin grafting, physiotherapy (27) Disadvantages: Older patients may suffer from hearing loss, dizziness, and imbalance. |

NA | e.g., MUL_3720 and Hsp18-based vaccines (268–271) |

| Cholera | Moderate dehydration: oral administration of WHO/UNICEF oral rehydration solution Severe dehydration: intravenous administration of rehydration fluids plus antibiotic treatment Symptomatic treatment: zinc therapy for children <5 years (45, 46) Disadvantages: Antibiotics can cause nausea and vomiting and should not be given to patients with only some or no diarrhea. |

Two types of licensed Vibrio cholera vaccines are commercially available: inactivated (Shanchol [Shantha Biotec]; Euvichol-Plus [Eubiologics]; Dukoral [SBL Vaccines]) and live attenuated (VaxChora [Emergent Biosolutions]) (37). | e.g., Dukoal, Shanechol, MORC-Vax (272) | |

| Leprosy (Hansen's disease) | Paucibacillary leprosy—antibiotics: rifampin, dapsone Multibacillary leprosy—antibiotics: rifampin, clofazimine, dapsone (273) Disadvantages: Antibiotics have to be taken for longer duration with follow up every 6 months for 10 years. Multidrug therapy does not provide cure in all cases of leprosy. |

NA | e.g., Th1-biasing adjuvant formulation; glucopyranosyl lipid adjuvant in stable emulsion (GLA-SE, LepVax) (274–276) | |

| Melioidosis | Acute phase (10–14 days)—antibiotics: intravenous administration of ceftazidime or meropenem Elimination phase (3–6 months)—antibiotics: oral administration of SMX-THT or amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (277, 278) Disadvantages: Single-drug antibiotic therapy is only partially effective. Combined antibiotic therapy must be used for extended periods. SMX-THT resistance reported in Thai isolates. |

NA | e.g., purN mutant (ΔpurN) (279, 280) | |

| Mycetoma (actinomycetoma) | Antibiotics: amikacin, rifampin, SMX-THT, amoxicillin-clavulanate, imipenem, gentamicin, doxycycline (245) Disadvantages: Less effective and with many side effects, and the patients should be followed closely to assess them clinically and biochemically. |

NA | e.g., epitope-based vaccine FFKEHGVPL (281, 282) | |

| Trachoma | Antibiotics: azithromycin, doxycycline, erythromycin, levoflaxin, ofloxacin Symptomatic treatment: surgery (246, 283) Disadvantages: It can take decades to evaluate the desired primary end point of trachoma treatment after the start of the intervention. Trials suggest merely a lowering of the risk, not a cure. |

NA | e.g., subunit Chlamydia vaccine (C. muridarum recombinant MOMP [rMOMP], native trimeric conformation [nMOMP]) (284, 285) | |

| Tuberculosis | Antibiotic treatment of M. tuberculosis infection varies depending on infection form (i.e., active or latent infection), antibiotic resistance (i.e., drug-resistant or multidrug-resistant infection), infected individuals (e.g., pregnant women, children), and coinfection status (e.g., HIV infection). Isoniazid, rifampin, rifapentine, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol are some of the main antibiotics currently used (12) Disadvantages: Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) is resistant to both isoniazid (INH) and rifampin (RFP). These antibiotics have many side effects, including gastrointestinal disturbance, psychiatric disorder, arthralgia, dermatological effects, ototoxicity, nephrotoxicity, peripheral neuropathy, hypothyroidism, and epileptic seizures. |

The BCG vaccine (live attenuated Mycobacterium bovis strain) is the only commercially licensed TB vaccine. | e.g., protein-subunit vaccine M72/AS01E, live attenuated VPM1002, MTBVAC (12, 44, 286, 287) | |

| Yaws | Antibiotic: azithromycin Alternative antibiotics: benzathine penicillin, doxycycline (288) Disadvantages: Painful during deep i.m. injection of antibiotics, allergy to penicillin, structural and logistic problems related to treatment. |

NA | Single-dose azithromycin for the treatment of yaws. (NIH, U.S. National Library of Medicine, ClinicalTrials.gov.) | |

| Parasite | African trypanosomiasis (African sleeping sickness) |

T. brucei gambiense—antiparasitics: pentamidine, eflornithine, NECT, melarsoprol, fexinidazole T. brucei rhodesiense—antiparasitics: suramin, melarsoprol (289) Disadvantages: Very toxic, prevalence in impoverished regions of Africa places economic constraints, small number of expensive drugs with limited efficacy and serious side effects and which are difficult to administer. |

NA | e.g., invariant surface glycoproteins (ISGs), conserved variant surface glycoprotein (VSG) (290, 291) |

| American trypanosomiasis (Chagas disease) | Antiparasitics: benznidazole, nifurtimox (292) Disadvantages: Significant side effects, efficacy decreases with length of the infection; treatment success difficult to measure; can take years before patients become seronegative (average, 16 years). |

NA | e.g., recombinant proteins (Tc24, TSA-1 with Th1 adjuvant) (293, 294) | |

| Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) | No commercially licensed antiparasitic drug to treat Dracunculus medinensis infection Physical extraction |

NA | NA | |

| Echinococcosis | Antiparasitics: mebendazole, albendazole, praziquantel Symptomatic treatment: surgery or PAIR (percutaneous aspiration, injection of chemicals, and reaspiration) (295) Disadvantages: Gold standard methods to determine efficacy of medical treatment, biological status, effective dose not available. No standardized diagnostic and monitoring methods for long-term follow-up. Treatment outcomes improve when surgery is combined with drugs; timing of chemotherapy pre/postsurgery unclear. |

NA | e.g., epitope-based vaccine (A5YTY7, A0A068WVL6) (296) | |

| Foodborne trematodiases | Antiparasitics: pranziquantel, triclabendazole, nitazoxanide Disadvantages: Few drugs are available, and therefore potential for emerging drug resistance is high. Reliable tests to detect parasites are not available; potential for misdiagnosis and incorrect treatment is high. |

NA | e.g., recombinant Ov-TSP-2 and −3, C. sinensis CsTP 22.3 kDa (297, 298) | |

| Leishmaniasis | Antiparasitics: sodium stibogluconate, pentavalent antimonials, amphotericin B, paromomycin, miltefosine Disadvantages: 60% of patients unresponsive, drug resistance common, combination therapy required, intramuscular or intravenous injections per day for 20–28 days lead to toxicity, drug efficacy compromised due to parenteral route of administration. |

NA | e.g., ChAd63-KH (299, 300) | |

| Lymphatic filariasis | Antiparasitics: diethylcarbamazine, ivermectin, albendazole, doxycycline Disadvantages: Temporarily clear microfilariae but not adult worms; where filariasis coexists with Loa loa, neurologic decline and encephalopathy are causes for concern. |

NA | e.g., thioredoxin peroxidase (TPX), collagen 4 (Col4) (301–303) | |

| Malaria | Antiparasitic treatment of Plasmodium species infection varies depending on two main factors: severity status (i.e., uncomplicated, severe, cerebral) and parasite species. Atovaquone and proguanil, artemether and lumefantrine, quinine sulfate and doxycycline, mefloquine, chloroquine phosphate, primaquine phosphate, and hydroxychloroquine are some of the main antiparasitics currently used (304). Disadvantages: Rampant drug resistance, questionable safety of antimalarials, side effects such as headache, dyspepsia, diarrhea, etc. Limited data are available on their efficacy in treatment of drug-resistant and non-falciparum strains. Difficult to achieve required drug concentration in infants. |

N/A | e.g., PfSPZ vaccine, chimpanzee adenovirus serotype 63 (ChAd63) (305) | |

| Onchocerciasis (river blindness) | Antiparasitics: ivermectin, moxidectin (306) Disadvantages: Questions remain if drugs can eliminate disease in areas of very high endemicity and loiasis coendemicity, due to severe reactions in people with Loa loa microfilaremia. Drug-resistant parasites are emerging following many years of treatment. Safe dose in children not determined. |

NA | e.g., recombinant proteins—Ov-103 and Ov-RAL-2 (307) | |

| Scabies | Antiparasitics: ivermectin, permethrin, crotamiton (13) Disadvantages: Neurotoxicity has been reported in children with widespread skin damage. Potential for emergence of drug resistance. Harmful effects on health and environment. Reinfection and recrudescence are common. |

NA | e.g., recombinant Sarcoptes scabiei chitinase-like protein 5 (rSsCLP5-based) vaccine (308, 309) | |

| Schistosomiasis | Antiparasitic: praziquantel (250) Disadvantages: Treatment does not prevent transmission or reinfection in areas of endemicity, as it is ineffective against juvenile parasites; prevalence will decrease only if more than 70% of the community participates; growing concerns regarding resistance, chemical residues, and cost. |

NA | e.g., recombinant Sh28GST/Alhydrogel (310–313) | |

| STH infections | Antiparasitic: albendazole or mebendazole Disadvantages: Increasing drug resistance, treatment often followed by rapid reinfection. |

NA | e.g., rAc-MTP-1, rAc-16 (314, 315) | |

| Strongyloidiasis | Antiparasitic: ivermectin Disadvantages: Development of drug resistance as parasite remains in the body for a long time, lack of standardization of antihelmintic treatment, toxicity, no test to detect cure currently available. |

NA | e.g., DNA immunization (Sseat-6 gene), Ss-IR (S. stercoralis immune-reactive antigen), srHSP60 (316) | |

| Taeniasis, cysticercosis | Taeniasis antiparasitics: praziquantel, niclosamide Cysticercosis antiparasitics: praziquantel, albendazole Symptomatic treatment: corticosteroids, antiepileptic drugs (neurocysticercosis), surgical extraction (depending on localization of the cysts) (317) Disadvantages: Death of the parasite between the 2nd and 5th day of treatment triggers neurological symptoms and, rarely, can be fatal. Side effects of praziquantel include malaise, headache, dizziness, nausea, fever, bloody diarrhea, etc. Side effects of albendazole include hepatotoxicity, alopecia, headache, nausea, urticaria. |

NA | e.g., recombinant vaccines (TSOL18 and TSOL45) (318, 319) | |

| Virus | Chikungunya | No commercially licensed antiviral drug to treat CHIKV infection Symptomatic treatment: rest, prevention of dehydration, administration of pain relief drugs (acetaminophen or paracetamol) to reduce fever and relieve some symptoms. Aspirin and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can be administered once DENV infection is ruled out (21). Disadvantages: Long-term pain management required for some with recurring joint pain in 20% of patients after 1 year. |

NA | e.g., live attenuated vaccine (TSI-GSD-218), live recombinant vaccine (MV-CHIKV), virus-like-particle vaccine (VRC-CHKVLP059-00-VP) (320, 321) |

| Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever | No commercially licensed antiviral drug to treat CCHFV infection Symptomatic treatment: intravenous fluids and electrolyte supplementation, oxygen therapy, coinfection treatment (17) Disadvantages: Requires high-level isolation facilities with proper biocontainment procedures. |

NA | e.g., CCHFV Bulgarian vaccine, CCHFV DNA vaccine (322, 323) | |

| Dengue | No commercially licensed antiviral drug to treat DENV infection Mild infection: treatment of symptoms with pain relief drugs (acetaminophen or paracetamol) to reduce fever and relieve some symptoms Severe infection: supportive hospital therapy (18) Disadvantages: For cases progressing to dengue hemorrhagic fever, patient requires hospitalization and extensive monitoring (recommended 4-h checks) during onset of critical phase. Vaccine requires strict cold-chain storage. |

A licensed live attenuated recombinant DENV vaccine is commercially available: CYD-TDV, Dengvaxia, Sanofi Pasteur (38). | e.g., tetravalent dengue vaccine (CYD-TDV), Sanofi Pasteur’s Dengvaxia (38, 324) | |

| Ebola hemorrhagic fever | No commercially licensed antiviral drug to treat EBOV infection Symptomatic treatment: intravenous fluids and electrolyte supplementation, oxygen therapy, antiemetic drug treatment, antidiarrheal drug treatment, coinfection treatment (14) Disadvantages: Requires high-level isolation facilities with proper biocontainment procedures. Vaccine requires strict cold-chain storage. |

A live attenuated recombinant licensed EBOV vaccine is commercially available: rVSV-ZEBOV, Ervebo, Merck. | e.g., inactivated EBOVΔVP3, Ad5.EBOV GP + Ad5.EBOV NP, Ad5.EBOVGPΔTM + Ad5.EBOV (325, 326) | |

| Japanese encephalitis | No commercially licensed antiviral drug to treat JEV infection Symptomatic infection: supportive hospital therapy, including neurological observation, intravenous fluids and electrolyte supplementation, administration of pain relief drugs to reduce fever and relieve some symptoms, rest (255) Disadvantages: Confirmation of suspected severe cases requires CT/MRI scans, spinal fluid extraction. Inactivated vaccines require 2 doses, and others require cold-chain storage. |

Three types of JEV vaccines are commercially licensed: inactivated (Ixiaro, Valneva Austria GmbH; JE-VAX, Sanofi Pasteur), live attenuated (CD.JEVAX, CDIBP), and recombinant (IMOJEV, Sanofi Pasteur) (39). | NA | |

| Lassa fever | No commercially licensed antiviral drug to treat Lassa virus infection Symptomatic treatment: intravenous fluids and electrolyte supplementation, oxygen therapy, coinfection treatment Disadvantages: Hospitalization required in severe cases. Ribavirin used for treatment in early stages, but it is not available in many regions and is suspected to be toxic and teratogenic. |

NA | e.g., ChAdOx1-Lassa-GP (327) | |

| Marburg hemorrhagic fever | No commercially licensed antiviral drug to treat MARV infection Symptomatic treatment: intravenous fluids and electrolyte supplementation, oxygen therapy, coinfection treatment (256) Disadvantages: Severity of disease require hospitalization in intensive care for all affected. |

NA | e.g., inactivated MARV, VRO-MARV GP, VRO-MARV NP (325, 328, 329) | |

| Rabies | Postexposure prophylaxis (before symptom onset): extensive wound washing, immediate vaccination, and administration of rabies immunoglobulin (if classified as severe exposure) (258) Disadvantages: Vaccine is effective after exposure but not after development of symptoms. Virtually always fatal after symptoms develop. |

A licensed inactivated rabies virus vaccine is commercially available: Rabipur/Rabipor/Rabavert, GSK; Imovax Rabies, Sanofi Pasteur (40, 41). | NA | |

| Rift Valley fever | No commercially licensed antiviral drug to treat RVFV infection Mild and short-duration infection: no specific treatment required, pain relief drugs can be used to reduce fever and relieve some symptoms Severe infections: supportive hospital therapy Disadvantages: Hospitalization required in severe cases, but treatment is generally limited to supportive care. |

NA | e.g., TSI-GSD-200, TSI-GSD-223 (330) | |

| Tick-borne encephalitis | No commercially licensed antiviral drug to treat TBEV infection Symptomatic treatment to treat neurologic symptoms (261) Disadvantages: Severe cases require hospitalization, including tracheal intubation and respiratory support. Vaccines not widely available. |

A licensed inactivated TBEV vaccine is commercially available: Encepur, GSK; TICOVAC/FSME-IMMUN, Pfizer; EnceVir, NPO Microgen (42). | NA | |

| West Nile fever | No commercially licensed antiviral drug to treat WNV infection Mild infection: no specific treatment required, pain relief drugs can be used to reduce fever and relieve some symptoms Severe infection: supportive hospital therapy (262) Disadvantages: Hospitalization required in severe cases and can require CT/MRI scans, spinal fluid extraction. |

NA | e.g., Hydrovax-001, ChimaeriVax-WN02, rWN/DEN4Δ30 (331–334) | |

| Yellow fever | No commercially licensed antiviral drug to treat YFV infection Mild infection: rest, dehydration prevention by drinking, administration of pain relief drugs to reduce fever and relieve some symptoms Severe infection: supportive hospital therapy Disadvantages: Hospitalization required in severe cases; however, treatment is generally limited to supportive care. Vaccine requires cold-chain storage. |

A licensed live attenuated YFV vaccine is commercially available: YF17D, YF-VAX/Stamaril, Sanofi Pasteur (43) | NA | |

| Zika | No commercially licensed antiviral drug to treat ZIKV infection Mild infection: rest, dehydration prevention by drinking, treatment of symptoms with pain relief drugs (acetaminophen or paracetamol) to reduce fever and relieve some symptoms Severe infection: supportive hospital therapy Disadvantages: Hospitalization required in severe cases. Pregnant women require monthly monitoring for fetal growth. |

NA | e.g., DNA vaccines (VRC5283, VRC5288, GLS5700), mRNA vaccines (mRNA-1325, mRNA-1893) (335, 336) | |

| Fungus | Chromoblastomycosis | Antifungals: itraconazole, thiabendazole, posaconazole, voriconazole, terbinafine, flucytosine, fluconazole, ketoconazole, amphotericin B Symptomatic treatment: heat treatment, cryotherapy, surgery (264) Disadvantages: Amphotericin B targets cholesterol-containing membranes, leading to cellular toxicity in humans. Side effects are significant, and therefore amphotericin B is used only for critically ill patients with serious fungal infections. Side effects of common antifungals include headaches, diarrhea, rash, nausea, and muscle or joint pains. Surgery is not usually recommended, as it is thought to facilitate spread of disease. |

NA | DNA-hsp65 vaccine (337) |

| Lobomycosis (lacaziosis) | No commercially licensed antifungal drug to treat Lacazia loboi infection No standard treatment is available to date; surgical excision and successful treatment protocols have been reported (25, 338, 339) Disadvantages: Recurrence is common after surgery due to contaminated tools or incomplete removal due to difficulty in demarcating the lesion site. Treatment with common antifungals including amphotericin B has been found to be inadequate. |

NA | NA | |

| Mycetoma (eumycetoma) | Antifungals: ketoconazole, itraconazole, voriconazole, posaconazole, terbinafine Symptomatic treatment: surgery, amputation (245) Disadvantages: Long treatment course. Side effects of common antifungals include headaches, diarrhea, rash, nausea, and muscle or joint pains. Amputation causes significant loss of life quality. |

NA | e.g., peptides KYLQ, FEYARKHAF, FFKEHGVPL (282) | |

| Paracoccidioidomycosis | Antifungals: itraconazole, amphotericin B, SMX-THT Supportive hospital therapy for severe infection (265) Disadvantages: Hospitalization required in severe cases. Side effects of common antifungals include headaches, diarrhea, rash, nausea, and muscle or joint pains. |

NA | e.g., antigen gp43, peptide P10 (340–342) | |

| Rhinosporidiosis | Combination of surgical excision and supportive medical therapy (dapsone, amphotericin B) (24) Disadvantages: Recurrence is common after excision. Treatment with amphotericin B results in significant cellular toxicity (as described above). Disease can occasionally be resistant to dapsone and may require combination therapy with other drugs. |

NA | NA | |

| Sporotrichosis | Oral administration of saturated solution of potassium iodide Antifungals: amphotericin B, itraconazole, terbinafine (266) Disadvantages: Potassium iodide treatment typically effective for skin infection only. Side effects of common antifungals include headaches, diarrhea, rash, nausea, and muscle or joint pains. Treatment with amphotericin B results in significant cellular toxicity (as described above). |

NA | e.g., humanized antibody (MAbP6E7) (343) | |

| Talaromycosis (penicilliosis marneffei) | Antifungals: amphotericin B, itraconazole, voriconazole (267) Disadvantages: Side effects of antifungals include headaches, diarrhea, rash, nausea, and muscle or joint pains. Treatment with amphotericin B results in significant cellular toxicity (as described above). |

NA | NA |

BCG, bacillus Calmette-Guérin; CCHFV: Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus; CHIKV, chikungunya virus; DENV, dengue virus; EBOV, Ebola virus; JEV, Japanese encephalitis virus; MARV, Marburg virus; NECT, nifurtimox-eflornithine combination therapy; RVFV, Rift valley fever virus; SMX-THT, sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim (cotrimoxazole); STH, soil-transmitted helminth; TBEV, tick-borne encephalitis virus; WNV, West Nile virus; YFV, yellow fever virus; ZIKV, Zika virus; i.m., intramuscular; CT/MRI, computed tomography/magnetic resonance imaging; Th1, T helper 1; NA, not applicable.

Licensing may vary between countries.

NATURAL PRODUCTS AND BIODISCOVERY POTENTIAL OF THE TROPICAL BIOME

Broadly, natural products can be defined as any metabolites produced by living organisms that are largely obtained from plants, animals, and marine and microscopic organisms. Metabolites include primary and secondary metabolites. While primary metabolites such as proteins, carbohydrates, and fats are vital for the growth and development of a living organism, secondary metabolites such as alkaloids, terpenoids, and flavonoids are responsible for its survival and defense against competitors and intruders (49). These natural products are being exploited and manipulated by humans for developing novel drugs (see Drug Development from Natural Resources and Therapeutic Solutions for Infectious Diseases of the Tropics, below). With an estimated 300,000 to 500,000 plant species and ca. 2 million lower classes of organisms, these resources are considered the chemotherapeutic pool, which can be exploited for developing drugs (50).

It is estimated that 50% of known plant species originate in the tropics (Fig. 1), with 14,000 species identified from the Amazon region alone (51). Similarly, the tropical Far North Queensland region of Australia is rich in rainforest (covering 3.6 million ha) and reef biomes, and its Wet Tropics World Heritage Area alone is home to over 2,800 plant species, including 700 endemic species that occur nowhere else on Earth (52). Approximately one-third of the medicinal plants used in the research and development of pharmaceutical drugs are found in rainforests (47). However, only a limited number of tropical plants and animals have been considered for medical uses and therefore provide an unprecedented opportunity for researchers and pharmaceutical companies to identify novel bioactive leads for potential commercialization.

Within the plant kingdom, the focus of pharmaceutical research has been on flowering plants, whereas mangroves and nonflowering plants, such as mosses, ferns, hornworts, cycads, liverworts, and lycopods, remain barely studied for drug development to date and represent an untapped source of novel compounds. Similarly, tropical lichens, fungi, insects, snails, reptiles, spiders, scorpions, and amphibians are not well characterized and are worthy of pharmaceutical exploration.

DRUG DEVELOPMENT FROM NATURAL RESOURCES

Developing drugs from natural sources is a lengthy and tedious endeavor. The biodiscovery pathways include specimen identification and collection, extraction and isolation, identification, and bioactivity testing (53). The most common challenge faced by researchers in translating laboratory discoveries to commercial drugs is access to sufficiently large quantities of biological samples and lead compounds, which is considered a “valley of death.” This bottleneck could be overcome through strategic collaboration between chemists (with expertise in natural products and organic synthetic chemistry), biologists (with expertise in biological processes and sample collection), immunologists (with expertise in cell- and animal-based assays), and bioinformaticians (to develop discovery platforms using large-scale genome sequence mining and shotgun metagenomics) (54).

Strategies for Drug Development from Natural Resources

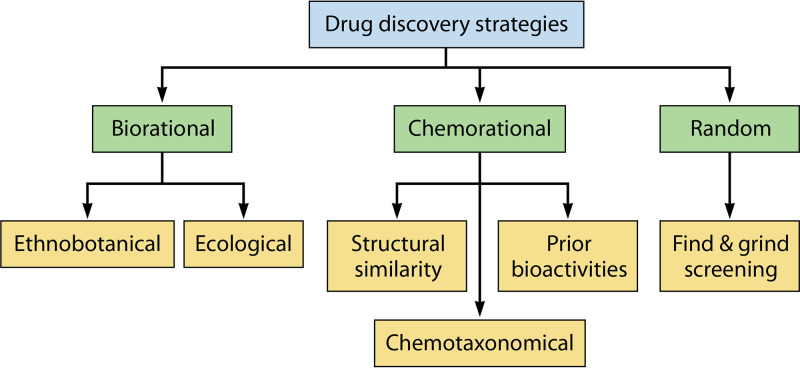

It is important to understand the existing techniques, technologies, expertise, and financial resources within the pharmaceutical field in order to devise an efficient drug discovery strategy (55). Several natural products containing compounds with activity against tropical disease-causing pathogens have been discovered. However, due to the high failure rate and the significant investment required to take a promising raw natural product forward, very few compounds have overcome the bottleneck toward becoming a new standard-of-care treatment for a tropical pathogen. Currently, the most common strategies used for discovering novel drugs from natural resources are (i) the random approach based on a “find and isolate” method, (ii) the biorational approach based on ecological and ethnobotanical methods, and (iii) the chemorational approach based on chemotaxonomical considerations (56) (Fig. 2). The last strategy uses information on plant-specific chemotypes, structural similarity, and reported bioactivities (57) to guide drug screening processes. Of these three strategies, the biorational approach, especially ethnobotany-guided screening, is the most efficient one. For example, 80% of 122 plant-derived drugs were discovered based on an ethnodirected biorational approach (58). This high hit rate of novel drugs or drug leads is mainly attributable to their extended clinical uses in traditional medicines.

FIG 2.

Strategies for searching for novel drugs from natural products. Common strategies for discovering novel drugs from natural resources include random, chemorational, and biorational approaches. The biorational approach relies on ethnobotanically focused screening and ecologically directed screening. The chemorational approach is directed by chemotaxonomical considerations. The random approach relies on high-throughput screening with no prior ethnopharmacological uses or chemotypical rationality.

Techniques for Drug Development from Natural Resources

A range of technologies spanning low to medium throughput has been available for decades, allowing the screening of viable pathogens responsible for tropical diseases. The bioassay screening protocols include in vitro, ex vivo, and in vivo models. For intracellular pathogens (e.g., Trypanosoma cruzi and Plasmodium spp.), cell-based screening methods adapted from conventional mammalian cell monitoring have been developed, such as the WST-1 assay (water-soluble tetrazolium) (59–61) or cell death monitoring with an array of fluorescent probes (62–65). While useful, these assays require careful consideration of the cell types used, as this choice can heavily influence the screening outcomes (66). For larger extracellular pathogens, particularly helminths, techniques are more challenging to develop. Nonetheless, a range of screening techniques have emerged over the past decade with various levels of scalability. These techniques include manual or automated video assessment (67), impedance motility monitoring (68, 69), enzymatic alamarBlue reduction (70), colorimetric (71), fluorescence (72, 73), and lactate or luminescent assays (74, 75).

Screening natural product libraries or raw products for their potential bioactive effect on pathogens can be a daunting task unless a high-throughput screen (HTS) can be developed for the target disease organism. Workflows that incorporate multiwell plates (e.g., 96 or 384 wells) can ideally be handled by robotics to allow for optimal HTS. Challenges arise when developing HTS for larger organisms, such as helminths. Often, the parasite life cycle stage that is key for treating clinical manifestation in humans is challenging to produce in sufficient quantities in the lab for adequate testing. Additionally, the physical size of the worm (millimeters to tens of centimeters long) can make large-scale handling (manual) of the parasite extremely difficult. Therefore, in many studies, the only feasible option for drug screening is to use analogues akin to the target macroscopic organism, such as easily available microscopic larval stages, or related microscopic model organisms, such as Caenorhabditis elegans (76, 77). While this allows simple HTS, the applicability to the desired target needs to be assessed appropriately. The limited applicability of these methods was recently highlighted in a study screening 1,280 compounds, in which neither the hookworm larva or C. elegans models demonstrated high fidelity as analogue models for detecting toxicity against the adult hookworm, the desired target that infects humans (78).

While the gold standard for evaluating antihelminth activity when screening drugs is visual phenotypic assessment of the parasite, the past decade has seen rapid advancement in adapting a range of HTS technologies (79). Some impedance-based methods based on either commercial cell monitoring products such as the xCELLigence system (ACEA Biosciences, Inc.) or custom “in-house” systems designed from the ground up for targeted purposes have been adapted and improved to allow antihelminth activity to be evaluated based on helminth mobility measurement (68, 80). While ultimately applicable to HTS, these methods so far have not been used for natural product screening beyond small research laboratory-based proof-of-principle studies, exploring 10 to 50 products at a time (81–84). Additionally, HTS of drugs against macroscopic disease-causing agents has been taking advantage of the development of advanced automated microscopy (85, 86). The automated imaging of a 12- to 384-well plate(s) allows, for a reasonably low cost, assessment of pathogen viability, and therefore the drug screening can be performed by a simple visualization of the pathogen mobility.

While many of these HTS techniques are commonly used in research laboratories worldwide, pathogens that require biocontainment higher than biosafety level 2 (BSL-2) (e.g., Mycobacterium tuberculosis, rabies, Rift Valley fever virus [RVFV], and West Nile virus [WNV] require BSL-3; Ebola virus [EBOV], Lassa virus, and Marburg virus [MARV] require BSL-4) can be uniquely challenging, especially in the tropics, where the proportion of low-income countries remains relatively high. Advances in modern robotics have made possible the incorporation of such technologies up to BSL-4 biocontainment capacities, allowing HTS of drugs for a range of deadly pathogens, including EBOV (87). However, capability will always be limited, and extensive safety restrictions limit full incorporation of HTS methods. One alternative to phenotypic screening that bypasses the parasite supply or safety limitations is virtual drug design based on protein sequences (88–91); while still a technically challenging and expensive method, it is slowly becoming more readily available with increasing computing power coupled with a decrease in the cost of sequencing technologies.

Omics Technologies for Drug Development from Natural Resources

As critical as the search strategies are, the success of drug discovery and development also relies heavily on the successful adaptation of advanced technologies to the discovery platforms. In many countries, increasingly affordable technological innovation in the areas of genomics, metagenomics, proteomics, and metabolomics have revolutionized the drug discovery programs (53). While genomics-, transcriptomics- and proteomics-based approaches have been extensively used to better understand the biology of parasitic helminths and facilitate development of diagnostics and therapeutics, metabolomics-based approaches have been largely overlooked. High-throughput technologies and software need to be integrated to enable big data generation, mining, and interpretation of the results.

Genomics and metagenomics.

Increasingly affordable sequencing technologies are changing how potential pharmaceutical drugs are being identified from natural products. While industrial investment in research programs aimed at discovering natural products suitable for pharmaceuticals has decreased in recent years (92), the use of next-generation sequencing technologies offers new screening pathways for targeted natural product discovery. Two sequencing applications in particular have the potential to revolutionize natural product discovery: large-scale genome sequence mining (93) and shotgun metagenomics (94). Large-scale genomic mining is a targeted approach, where the entire genome sequence from organisms of interest is interrogated in order to identify previously uncharacterized natural products. In contrast, shotgun metagenomics is an untargeted approach, where all sequences present in a community/environment are interrogated for novel natural products; however, with this approach, the organism of origin may not be known.

Many natural products have been discovered using genomics technologies. For example, genome mining of individual species led to the discovery of the novel polyphenolic polyketide antibiotic clostrubin from Clostridium beijerinckii, a strictly anaerobic bacterium (95), in addition to novel aminocoumarins from the uncommon actinomycete Catenulispora acidiphila DSM 44928 (96). To date, most sequence-based natural product discoveries have relied on individual genome sequences; however, the growth of high-quality, publicly available sequence data is enabling the simultaneous genome mining of thousands of species. For example, a recent study mined 10,000 actinomycetes in a search for novel phosphonic acids, an important class of natural products with known antimicrobial, antiviral, antimalarial, and herbicidal activities. This study identified a new archetypical pathway for phosphonate biosynthesis in addition to 11 previously undescribed phosphonic acid natural products (97). The authors propose their methodology as a generalizable framework suitable for the rapid discovery of other natural product classes in order to discover lead compounds suitable for the pharmaceutical industry (97).

Functional metagenomics are also being used as screening tools for natural product discovery at both the species level (e.g., Strepomyces [98]) and in complex environment samples (e.g., marine [99]). These methods are becoming increasingly popular for accessing bacterially encoded secondary metabolites, as it gives access to products from the majority of bacteria that are not readily culturable. Shotgun metagenomic sequencing has several advantages in that it is unbiased and requires no species-specific lab-based preparation, but most critically, it allows access to all the organisms’ collective genomes and thus provides a snapshot of the bioactive potential of entire bacterial populations in a single experiment. Additionally, the genetic information encoding the relevant biological activities are typically clustered on bacterial genomes, meaning that with limited starting material, it is possible to capture sequence describing the biological pathway of interest.

The last decade has seen an acceleration in the sequencing of microbial, fungal, and plant genomes, with tens of thousands of genomes now available in public archives, including GenBank and Ensembl. Despite the generation of this large volume of data, there exists a bottleneck in our ability to process and analyze these data in a meaningful way. In natural drug discovery, genome mining techniques have emerged as an approach to identify potential products of interest (100, 101), where secondary metabolites from biosynthetic gene clusters that encode novel bioactive metabolites are identified. In recent years, software to support genome mining have significantly matured for microbes and fungi. For example, AntiSMASH (antibiotics and secondary metabolite analysis shell) (102) uses computational methods to rapidly identify, annotate, and analyze secondary metabolite biosynthesis gene clusters identified in bacterial and fungal genomes. Many other software tools that exist are typically specific to either an organism group(s) or pathways. These include SMURF for fungal metabolites (103), BAGEL3 for prokaryotes (104), PRISM (Prediction Informatics for Secondary Metabolome) for microbial organisms (105), IMG/ABC for storing experimentally validated BCGs (106), and ASMPKS for predicting modular polyketide synthases (107). While progress has been made in regard to microbes and fungal genomes, tools available for plant-based drug discoveries are significantly lagging.

Proteomics.

Over the last few decades, numerous proteomic approaches have been developed and applied to facilitate the process of identifying protein and small molecule drug candidates. Typically, bioactivity or phenotype-based drug discovery involves the development and execution of bioassay screens to guide the isolation of the active fraction leading to the eventual identification of the active compounds (108, 109). Mass spectrometry, with its ability to identify small molecules and proteins through their fragment peptides, is an integral step in both proteomics and metabolomics (see “Metabolomics,” below) and has been used to characterize small molecules and natural products since the 1960s (110).

Recent improvements have been made in both the utility and sensitivity of mass spectrometers (111). An example of this progress is the recently released high-performance mass spectrometer Orbitrap Fusion Lumos Tribrid. With a resolution of up to 1,000,000 full width at half maximum (FWHM) values at m/z 200, this mass spectrometer combines Orbitrap, quadrupole, and linear ion trap technologies in one acquisition path, which allows it to acquire a more complex spectra at a higher rate (112, 113).

Other forms of chemistry or affinity-based fraction selection techniques range from simple solvent extractions (114) to molecular affinity, as mentioned above, as well as more complex techniques such as photoaffinity labeling, which allows potential drug compounds to be labeled with a photo cross-linker and a purification tag (109). Modern techniques taking advantage of newly discovered biochemical interactions between proteins and their ligands, such as the cellular thermal shift assay, have shown promise as drug discovery techniques. The cellular thermal shift assay is based on the rationale that protein stability can be altered by ligand binding (115), and it was recently demonstrated that studying the shift in the heat denaturation curves of the cellular proteomes after exposure to lead compounds can identify effective binding partners (116).

Novel extraction technologies have also been developed to address chemical and biological constraints and to improve overall extraction and downstream detection efficiency. These include high-intensity pulsed electric fields combined with semibionic extraction (117), highly sensitive supercritical fluid extraction (118), high-speed countercurrent chromatography (119), and sequential extractions combining multiple techniques to extract compounds with different properties from a single source (120).

Metabolomics.

Metabolomics uses multiple technologies, including high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), infrared spectroscopy (IR), gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS), liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS), and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) (53). Metabolomics platforms are increasingly being used for a variety of applications, including diagnosis of diseases, infections, host-parasite interaction, biomarker and drug lead discoveries, drug target identification, drug interaction, and personalized treatments (121). Metabolomics techniques are also emerging for the identification of the secreted metabolites by tropical canine parasites, such as hookworm, tapeworm, and roundworm (122, 123). There is a need to apply metabolomics to identify biomarker compounds for many other tropical parasites in order to understand the mechanisms responsible for their parasitism and host immune evasion.

THERAPEUTIC SOLUTIONS FOR INFECTIOUS DISEASES OF THE TROPICS

Approved Therapeutic Molecules Derived from Natural Products

Historically, natural products have been employed in the treatment of many diseases affecting humans. The Dictionary of Natural Products (https://www.routledge.com/go/the_dictionary_of_natural_products), an authoritative and comprehensive database on natural products, lists 270,000 chemical entities, some of which are considered vital components of many modern drugs (124). Newman and Cragg recently reported that 1,881 naturally derived drugs were discovered and approved as drug entities between 1981 and 2019 (125). It is also estimated that approximately half of all medications validated between 1981 and 2010 have been sourced from natural products (126). As an example, out of 15 antiparasitic compounds used between 1981 and 2014, 60% of these have their origins in natural products (127). However, the majority of them are either semisynthetic or mimics of the natural bioactive compounds, resulting in a significantly smaller percentage (5%) of natural products sourced directly from nature and used as therapeutic molecules (126). This section highlights the most commonly used approved pharmaceutical drugs sourced from natural products.

Tetracyclines.

Tetracyclines are a family of broad-spectrum antimicrobial agents that were discovered in the 1940s. They are still used for their antimicrobial activity against a range of microbes implicated in many diseases, including some tropical diseases like malaria, where it is used as primary treatment for mefloquine-resistant Plasmodium falciparum (128), as well as trachoma and yaws (129, 130). Chlortetracycline (initially called aureomycin due to its yellow color) and oxytetracycline (initially called terramycin, in reference to terra, Latin for earth) were the first of the tetracyclines isolated from Streptomyces aureofaciens and Streptomyces rimosus, respectively (131–133). Similar molecules of the same class were subsequently extracted from S. aureofaciens, S. rimosus, and Streptomyces viridofaciens (tetracycline and demeclocycline) or synthesized through modification of natural products (e.g., doxycycline, lymecycline, methacycline, minocycline, rolitetracycline) (131, 134). Tetracyclines are known to bind to the bacterial 30S ribosomal subunit to reversibly inhibit bacterial protein synthesis and blocking them from growing or replicating further, a mode of action called “bacteriostatic” (129). However, since the isolation of the first tetracycline-resistant bacterium, Shigella dysenteriae (135), multiple microbial species have been reported to have acquired resistance to the natural (first-generation and some second-generation) tetracyclines, leading to the introduction of newer (third-generation) synthetic tetracyclines (136–138).

Quinine.

Quinine is a basic alkaloid prepared from the bark of the Cinchona plant. The WHO recommends its use in combination with clindamycin in the management of uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria in pregnant women who are within their first trimester. In the first trimester of pregnancy, quinine is also recommended for treatment of chloroquine-resistant Plasmodium vivax malaria (139). Additionally, quinine administration has been recommended for severe malaria in adults and children if artesunate and artemether (see “Artemisin” below) are not available (139). The mechanism behind quinine’s antimalaria action is not fully understood. It was demonstrated that its antimalaria activity could be from the ability of its quinoline group to cap hemozoin, which is crystallized from heme, as the parasite digests hemoglobin in red blood cells (140). Heme is chemically destructive and causes cellular damage through various means, such as oxidative stress and cytoskeletal protein disruption (141). Quinoline capping of hemozoin crystals prevents the parasite from detoxifying heme into insoluble and inert heme, thereby allowing free heme to build up, poisoning the parasite (140). Lastly, it must be noted that quinine has considerable adverse effects, which can range from impairment of hearing, tinnitus, headaches, and nausea to vertigo, vomiting, and loss of vision (142). Despite this, quinine remains a viable alternative to many approved pharmaceutical drugs due to its low cost and the emergence of resistance to other common antimalarials.

Artemisinin.

The use of the Artemisia annua plant, also known as sweet wormwood, to treat intermittent fevers among other indications has been documented in the Chinese materia medica in the late 1960s (143). In the early 1970s, artemisinin, a sesquiterpene lactone, was identified as responsible for the antimalarial activity of A. annua (144). Although the use of nonpharmaceutical forms of A. annua is not recommended by the WHO, artemether, artesunate, and dihydroartemisinin, its more stable semisynthetic derivatives, are included in the artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) recommended for treating malaria (139, 144). Both artemether and artesunate are metabolized by the body into dihydroartemisinin, which has various toxic effects against the parasite, including alkylation and misfolding of proteins initiated by free radicals created from the cleavage of the endoperoxide bridge found within the dihydroartemisinin molecule (144–146). ACTs constitute first-line therapies for most indications of malaria, including severe malaria. Depending on the indication, these compounds are frequently used in combination with other long-acting synthetic antimalarials, such as lumefantrine or amodiaquine (139). This is because artemisinin-based compounds have a short half-life and the longer-lasting synthetic compounds can continue to provide antimalarial activity to prevent the rise of drug resistance after artemisinin reaches subtherapeutic concentrations in the body (147).

NATURAL PRODUCT DISCOVERIES FOR THE TREATMENT OF TROPICAL DISEASES

Increasingly, natural products are being examined for their suitability in the treatment of tropical diseases caused by bacteria, virus, parasites, and fungi. There are many studies highlighting the effectiveness of natural products in treating tropical diseases.

Bacteria

In a very comprehensive review of recipes used by traditional healers in Burundi, Ngezahayo and colleagues recently identified a list of 155 different plant species belonging to 51 families and 139 genera used to prepare treatments for microbial tropical diseases of bacterial origin (148). Similarly, based on local folklore, Gupta et al. have collected 35 different plant species from India with anecdotal evidence of antituberculosis activity (149). Upon further examination, the ethanol extracts of 11 of those plants showed clear antimycobacterial activity (Table 3). There is also evidence that many plants from the Ivory Coast, Ghana, and Benin used to treat Buruli ulcer contain active ingredients with in vitro and in vivo activity against Mycobacterium ulcerans (150–156) (Table 3). Additionally, a plant-based treatment using Capparis zeylanica has been associated with a reduction of the diarrhea in patients suffering from cholera (157) (Table 3). Several other studies have described plant-based treatments of cholera (148), leprosy (148, 158, 159), and yaws (148); however, these studies do not provide clear evidence of the implication of the natural products in the improvement of the symptoms. Traditionally, most of these plant-based treatments are applied either as a maceration, powder, or decoction, indicating that the active ingredients within some of these plants may have topical and/or oral antibacterial activity.

TABLE 3.

Active compounds from natural products with activity against tropical disease-causing bacteriaa

| Disease | Description and pathogenesis | Geographical distribution | Product family/class | Extracts/natural product | Product source or origin | Extraction method | Efficacy/assessment model | Biological activity | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buruli ulcer (BU) | BU is caused by Mycobacterium ulcerans. Pathogenesis of BU relies on mycolactone, a polyketide-derived macrolide. Its mode of transmission remains poorly understood, but the current hypothesis is that the disease is transmitted from stagnant bodies of water or mosquitoes. | BU was first described in Australia but has been reported from 33 countries worldwide, including West Africa, Central and South America, and the Western Pacific. About 73% of the total global cases have been reported from Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, and Benin. | Naphthofurans | Rifampin | Amycolatopsis rifamycinica | Extracted from fermentation culture of the bacterium | Clinically used for treating BU | Oral administration of rifampin (10 mg/kg orally once daily) | 27, 344 |

| Benzene and substituted derivatives | Streptomycin | Streptomyces griseus | Extracted from fermentation culture of the bacterium | Clinically used for treating BU | Intramuscular injection, 15 mg/kg of body weight for 8 weeks | 345 | |||

| Alkaloids | Holadysamine | Holarrhena floribunda | 50 g of powder was macerated and extracted using 70% ethanol. | In vitro: well diffusion assays | Compound inhibited the growth of M. ulcerans at MIC of 50 μg/ml | 155 | |||

| Holophyllinol | Compound inhibited the growth of M. ulcerans at MIC of 125 μg/ml | ||||||||

| Holamine | |||||||||

| Holaphyllamine | |||||||||

| Crude extract | Moringa oleifera | Extracted with water | Children with skin lesions clinically suggestive of BU (2–15 years old) were given normal diet spiked with 330 ml of M. oleifera/child at each meal. | Children’s ulcers decreased from 72 mm to 48 mm on day 56 after administration of water extract of (330 ml) M. oleifera. | 154 | ||||

| Aglaonema commutatum | Leaves boiled in water for 5 min | 200 μg/ml of extract was prepared and diluted with medium (1st to 8th dilution); MIC was determined at final concentrations (25% [vol/vol] to 0.20% [vol/vol]) corresponding to 50 μg/ml to 0.4 μg/ml. |

In vitro activity with MIC of 40 μg/ml |

346 | |||||

| Aloe vera | Leaves macerated in water | ||||||||

| Alstonia boonei | |||||||||

| Capsicum annum | Fruit macerated in water | ||||||||

| Gratiola officinalis | Bark boiled in water for 20 min | In vitro activity with MIC of 1.56–25 μg/ml | |||||||

| Jatropha curcas | Leaves macerated in 70% ethanol | In vitro activity with MIC of 250 μg/ml | |||||||

| Spigelia anthelmia | Leaves and grains boiled in water for 5 min | In vitro activity with MIC of 6.25–25 μg/ml | |||||||

| Syzygium aromaticum | Seeds boiled in water for 20 min | In vitro activity with MIC of 25 μg/ml | |||||||

| Zea mays and Spigelia anthelmia | Grains and leaves boiled in water for 5 min | In vitro activity with MIC of 6.25–25 μg/ml | |||||||

| Zanthoxylum zanthoxyloides | Roots boiled in water for 20 min | In vitro activity with MIC of 12.5–25 μg/ml | |||||||

| Trachoma | Trachoma is a bacterial infection of the eyes and genitals, which is spread through flies or direct contact. The eye infection can lead to blindness. | Trachoma is widespread across Africa, Asia, and Central and South America, with the highest prevalence in Ethiopia and South Sudan. | Flavonoids | Baicalin | Scutellariae baicalensis | Purchased commercially, dissolved in DMSO | Female mice were infected with Chlamydia trachomatis, followed by 1 mM intravaginal rinse treatment. | Reduced bacterial counts by 78% after 5 days and 99.9% after 11 days | 178 |

| Flavonoids | Luteolin | Wide range of plants such as trees, herbs, and vegetables. Sourced from Extrasynthese, Genay, France | Purchased commercially, dissolved in DMSO | Chlamydia trachomatis bacterial challenge, followed by 2 mg/kg intraperitoneal injection treatment | Showed 25% and 37% fewer pathogen-positive mice at days 6 and 13, respectively | ||||

| Flavonoids | Catechin | Various vascular plants, sourced from tea leaves | Boiling in water | In vitro HL cells (human airway epithelium line) cultured with bacteria and treatments applied in culture medium | A 0.4-mg/ml concentration applied topically was completely inhibitory | ||||

| Polyphenols | Flavones, flavonols, coumarins, gallates | Various vascular plants | Purchased commercially, dissolved in DMSO | In vitro HL cells (human airway epithelium line) cultured with bacteria and treatments applied in culture medium | A 50 μM concentration was highly active (85%–100% inhibition) | ||||

| Tuberculosis | TB is a pulmonary disease that is initiated by the deposition of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, contained in aerosol droplets, onto lung alveolar surfaces. The progression of the disease can have several outcomes, determined largely by the response of the host immune system. | Most new cases of TB are in Asia and Africa. | Quinonoids | Plumbagin and crotonate plumbagin | Root of Plumbago indica Linn collected from Orissa, India | Multiple extraction methods | Broth microdilution assay Resazurin microplate assay (REMA) |

Inhibition of thymidylate synthase MIC of 0.25–16 μg/ml | 160 – 162 |

| Flavonoid | Kaempferol and its benzyl derivative | Leaf extract of Rhoeo spathacea, Pluchea indica from Indonesia | In silico modeling of molecular structures | AutoDock Vina, followed by 50-ns molecular dynamics simulation using YASARA | In silico inhibitor of the CYP121 M. tuberculosis enzyme | 163 | |||

| Naphthoquinones | Maritinone | Stem bark extract of Diospyros anisandra | Maceration and liquid-liquid fractionation | Cytotoxicity assay using Vero cells and peripheral blood mononuclear cells | Bacteriostatic activity MIC of 1.56–3.33 μg/ml | 164 | |||

| 3,3′-Biplumbagin | Bacteriostatic activity MIC of 1.56–3.33 μg/ml | ||||||||

| Iridoids-plumeride | Plumericin/isoplumericin | Stem bark of Plumeria bicolor | Extracted by methanol | Tetrazolium bromide assay | Bacteriostatic activity MIC of 1.5–2.1 μg/ml | 165 | |||

| Piperidines | Dipiperidine derivatives | Piper nigrum | Not applicable | Luciferase growth inhibition assay, in vivo M. tuberculosis induced weight loss in mouse and human trials | Disease reduction and bacterial growth inhibition | 170 | |||

| Bacteriostatic activity MIC in the range of 4.0–32.0 μg/ml | 171 – 174 | ||||||||

| Gallic acid-derivatives | 3-O-methyl-alkylgallates | Loranthus micranthus | Maceration | Bactericidal assay | Bacteriostatic activity MIC of 6.25 μM | 166 | |||

| Coumarin-type compound | Collinin | Zanthoxylum schinifolium found in Korea, China, and Japan | Extracted by methanol and isolated using HPLC | Microbial cell viability assay | Bacteriostatic activity MIC of 3.13–6.25 μg/ml in culture broth and 6.25–12.5 μg/ml inside cells | 167 | |||

| Acridone alkaloid | (i) Hydroxy-1, 3-dimethoxy-10-methyl-9-acridone, (ii) 1-hydroxy-3-methoxy-10-methyl-9-acridone, (iii) 3-hydroxy-1, 5, 6-trimethoxy-9-acridone |

Stem bark of Zanthoxylum leprieurii from Mpigi District, Uganda | Crude extract extracted with methanol column chromatography | Microplate alamarBlue assay | Bacteriostatic activity MIC of 5.1 μg/ml | 168 | |||

| Cucurbitacins | Ursolic acid | Ripe deseeded fruit of Citrullus colocynthis collected from Rajasthan, India | Extracted with petroleum ether, chloroform, methanol, and water | Maceration chromatography, bacterial viability assay | Bacteriostatic activity MIC of 50 μg/ml | 169 | |||

| Cucurbitacins | Cucurbitacin | Ripe deseeded fruit of Citrullus colocynthis collected from Rajasthan, India | Extracted with petroleum ether, chloroform, methanol, and water | Maceration chromatography, bacterial viability assay | Bacteriostatic activity MIC of 25 μg/ml | 169 | |||

| Sponge-derived bengamide | Bengamide B | Tedania sp. collected from East Diamond Islet, Queensland, Australia | Marine sponge extract, isolated using HPLC | Intracellular mycobacterial activity assay | Interference with methionine aminopeptidase activity MIC of 0.39–1.56 μg/ml | 175 | |||