Abstract

Objectives:

To describe the design and implementation of an injury surveillance system for youth mountain bike racing in the United States, and to report preliminary first-year results.

Design:

Descriptive sports injury epidemiology study

Methods:

After two and a half years of development and extensive beta-testing, an electronic injury surveillance system went live in January, 2018. An automated email is sent to a Designated Reporter on each team, with links to the injury reporting form. Data collected include demographic information, injured body part, injury diagnosis, trail conditions and other factors associated with injury occurrence.

Results:

837 unique injuries were reported in 554 injury events among 18,576 student-athletes. The overall injury event proportion was 3.0%. The most common injury among student-athletes was concussion/possible concussion (22.2%), followed by injuries to the wrist and hand (19.0%). Among 8,738 coaches, there were 134 unique injuries reported that occurred in 68 injury events, resulting in an overall injury event proportion of 0.8%. The shoulder (38.2%) was the most commonly injured body part among coaches. Injuries among coaches tended to more frequently result in fractures, dislocations and hospital admission compared with injuries among student-athletes. Among student-athletes, female riders sustained lower limb injuries more than male riders (34.0% vs. 20.7%, p < 0.001).

Conclusions:

A nationwide injury surveillance system for youth mountain bike racing was successfully implemented in the United States. Overall injury event proportions were relatively low, but many injury events resulted in concussions/possible concussions, fractures, dislocations and 4 weeks or longer of time loss from riding.

Keywords: sports, epidemiology, methods, injury, injury prevention

Introduction

Mountain biking is a relatively new sport that has increased in popularity in many parts of the world.1–4 Alongside the growth in recreational mountain biking, there has been an increase in adult, and later youth, mountain bike racing. In 2009, the National Interscholastic Cycling Association (NICA) was formed as the oversight body for middle and high school mountain bike racing in the United States. As the oversight body for youth mountain bike racing in the United States, NICA is responsible for the administration of all competitive and non-competitive cross-country mountain biking activities, including implementation of rules, league certification, athlete registration, coach registration and development and training camps. In ten years, NICA has grown from one small league to 26 leagues across the country. By 2018, there were over 18,000 student-athletes participating in NICA sanctioned mountain biking in the United States.

Mountain biking is not without risk.1, 5 Athletes use bicycles with shock absorbers and wide, knobby tires to negotiate trails in mountain environments that are often narrow and have natural obstacles, such as rocks and tree roots. Aiming to protect participants, NICA partnered with sports epidemiology researchers to design, test and implement a prospective, longitudinal injury surveillance system (ISS) to better characterize injuries seen in youth mountain bike racing and investigate injury prevention strategies. This paper describes the design and methodology of the NICA Injury Surveillance System (NICA ISS) and also presents preliminary data from the 2018 inaugural year of the project. To the authors’ knowledge, this is the largest mountain biking ISS in existence. Additionally, this is the first ISS that we are aware of that tracks injuries in coaches, who ride with the student-athletes during practice rides but not races.

Injury surveillance systems have become an important component of sports medicine research over the past 20 years.6, 7 An ISS serves multiple purposes, including to improve the understanding of injuries and illnesses that affect athletes. Another purpose of an ISS is to inform researchers and sports administrators as they design, implement and test data-driven prevention strategies. Such systems have been put into place by various sports organization, including the International Olympic Committee, the International Paralympic Committee and others at the international, regional and local levels.6

Methods

Recognizing the dramatic growth in the sport, as well as the above-mentioned benefits, NICA partnered with researchers and began discussions in 2015 regarding implementation of a comprehensive, nationwide ISS. Over the ensuing two and a half years, the NICA ISS was designed and extensively tested, before going live for the 2018 season. To optimize the effectiveness of the ISS, the research team had several goals for the electronic injury tracking system as listed in Table 1. An electronic/online/web-based sports injury surveillance system has been used extensively in recent years, with the advantages and challenges well documented.8–11

Table 1.

Goals for electronic injury tracking system.

|

With these goals in mind, the research team consulted with numerous stakeholders, including student-athletes, coaches, parents, race officials and sports epidemiology experts during the construction of the system. After a preliminary version of the ISS was beta-tested in two leagues in 2017, extensive optimizations were performed ahead of the inaugural 2018 data collection year. Participation in the ISS is mandatory for all NICA teams. In 2018, there were 24 NICA leagues across the country.

The injury reporting system was built in REDCap (https://www.project-redcap.org), a highly secure academic research platform that offers excellent flexibility, functionality and ability to store and retrieve large volumes of data. Each week, the system automatically generates an email to a Designated Reporter on each NICA team. The Designated Reporter is an official with each team, often a head coach, who has volunteered to receive the weekly emails and enter data into REDCap, after consulting with the rider and his or her parents as indicated. The Designated Reporter may or may not have medical training. The NICA ISS does not collect identifying information about the Designated Reporters. The Designated Reporters enter data directly into REDCap. If there were no injuries on that team in the prior week, the Designated Reporter chooses an option indicating “No Injuries this Week.” If an injury occurred during the prior week, the Designated Reported chooses the student-athlete’s name in the roster list at the bottom of the email and is automatically directed to the injury report form where the rider’s demographic information is pre-populated (Appendix A). The injury report form is user friendly and takes approximately five minutes to complete. A separate injury form is completed for each injury event. The Designated Reporter completes the injury report form after obtaining additional details about the injury event and about the specific injuries from the injured rider, their parents or guardians as appropriate and witness to the injury event. The Designated Reporter can report more than one specific injury for each injury event. The system is constructed such that the Designated Reporter can return to the injury form at a later time to enter additional information as it is obtained, such as time lost due the injury.

The Designated Reporter is also asked to complete a weekly, one-minute exposure survey designed to identify the number of riders participating in each individual practice ride and race over the past week (Appendix A). Designated Reporters were provided detailed instructions on completing the exposure report and injury form. NICA mandated participation for all teams. NICA only sanctions cross-country mountain biking, not other disciplines such as downhill or enduro racing.

Injury Definition:

An injury event is defined as any physical event that occurs during a NICA-sanctioned practice, race, or other training session that results in physical harm to the participant significant enough to:

Warrant referral to a medical provider

OR

2) Lose time from training or competition beyond the day of injury

OR

3) Miss school or work

An injury event may result in more than one unique injury. The following categories of data pertaining to injury are collected: rider demographics, competition division, trail characteristics at crash location, weather, other factors felt to contribute to the incident (e.g., technical nature of trail, rider inexperience), body part injured, diagnosis category, time loss due to injury.

De-identified composite data are exported from REDCap in various formats, including CSV and major statistical packages, for analysis. Data can be summarized using descriptive statistics. Further, inferential statistics can be used to conduct significance testing. Examples of such analysis include testing injury rates, injury characteristics, and time loss by sex, class/grade, and league. NICA student-athletes are in grades 8-12. Time loss is defined as the number of days that a student-athlete or coach is unable to ride their mountain bike during either practice rides or races. If proportions are to be compared, a χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test will be used. An independent t-test can be used to compare quantitative variables (e.g., time loss) by group (e.g., sex). Multivariate analysis, such as multiple regression analysis and mixed-effects models, can be used to examine outcome variables of interest while using a unique ID assigned to each injured athlete as an identifier and accounting for the effects of other variables. In order to test data validity, the research team and NICA officials will compare 5 specific injury-related factors from the database for 50 injured student-athletes and presence/absence of injury for 50 student-athletes for whom no injury was reported. All injury data are retained regardless of team compliance rate. League directors may request their own leagues data, but may not request injury data from other leagues. NICA and the research team produce an Annual Report for composite, nationwide data at the end of each season. The Annual Report is posted on the NICA web site.

In this paper, we mainly report descriptive statistics for injury-related variables, separately for student-athletes and coaches. Specifically, in this first year of data collection, compliance with reporting student-athlete exposure was insufficient to calculate incidence rates. Compliance was challenging to estimate due to variations in league-specific training calendars and coaching/student-athlete overlap between teams (some coaches overseeing multiple teams and some student-athletes participating on more than one team). The percentage of compliant teams was calculated by dividing the total number of submitted exposure reports by the total number of possible exposure reports (number of teams multiplied by number of weeks practicing). This was estimated to be around 55%. Therefore, injury events are reported here as an injury event proportion which is analogous epidemiologic incidence proportion12 and (injury) incidence proportion used in literature.13 This study was approved by the University Institutional Review Board (IRB_00087405).

Results

Student-Athlete Injuries

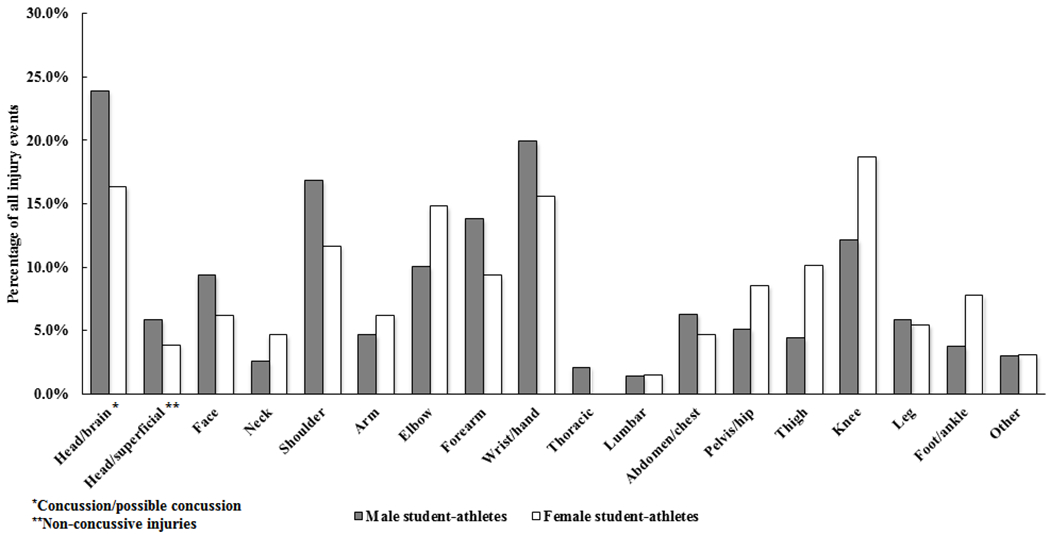

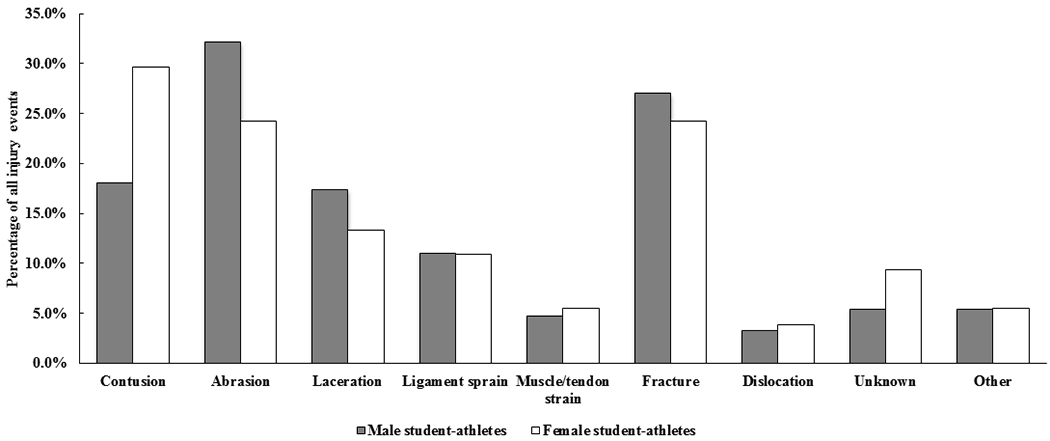

During the 2018 inaugural year, the NICA ISS recorded 554 injury events in 18,576 student-athletes (14,819 or 79.8% males and 3,757 or 20.2% females), resulting in an injury event proportion of 2.98%. There was an average of 1.5 injured body parts per injury event (837 unique injuries in 554 injury events). Figures 1 and 2 summarize injured body parts and injury types in student-athletes. The most commonly injured body parts were head/brain (concussion/possible concussion, 22.2%), wrist/hand (19.0%), and shoulder (15.7%). Contusions and abrasions accounted for 51.1% of all non-concussion injuries. Fractures and dislocations accounted for 29.8% of all non-concussion injuries.

Figure 1.

Summary of injured body parts in student-athletes.

Figure 2.

Summary of injury types in student-athletes.

Injured student-athletes were unable to complete their practice ride or race 70.2% of the time. 6.5% of injured student-athletes were evacuated from the crash site by ambulance and 0.4% were evacuated by helicopter. 44.4% of all injury events resulted in an emergency room visit, but only 2.7% of injuries resulted in hospital admission. 36.4% of injury events resulted in time loss from riding of less than one week, whereas 28.8% resulted in time loss of at least 4 weeks.

Injury events occurred during a team practice on mountain bike trails 54.5% of the time and during a race 31.8% of the time. 48.2% of injury events occurred while riding downhill, 31.9% occurred on flat terrain, and 8.7% occurred while riding uphill. 77.1% of injury events occurred on a trail that the student-athlete was familiar with. Other common factors reported to be associated with injury events included inexperience of the student-athlete (21.3%), technical nature of the trail (19.1%), and negotiating a turn (16.8%).

There was no significant difference in overall injury proportions between females and males (3.4% vs. 2.9%, p = 0.087), though there was tendency of a higher injury rate among females. Injury patterns in student-athletes differed by sex; 34.0% of injuries in females were to the lower limb while 20.7% of injuries in males were to the lower limb (p < 0.001).

Coaches Injuries

Among 8,738 coaches, 68 injury events were reported for an injury event proportion of 0.78%. There was an average of 2.0 injured body parts per injury event (134 unique injuries in 68 injury events). The most commonly injured body parts were shoulder (38.2%), followed by head/brain (concussion/possible concussion, 17.6%). Contusions and abrasions accounted for 53.0% of all non-concussion injuries in coaches. Fractures and dislocations resulted in 39.8% of all non-concussion injuries.

Injured coaches were evacuated from the crash site by ambulance 11.8% of the time and by helicopter 5.9% of the time. 58.8% of all injury events to coaches resulted in an emergency room visit, and 13.2% of all coach injuries resulted in hospital admission. 27.5% of injury events resulted in time loss of less than one week and 43.1% resulted in time loss of at least 4 weeks. 60.3% of injury events occurred on downhill sections of trail, 23.5% occurred on flat sections and 10.3% occurred on uphill sections. Other common factors reported to be associated with injuries included negotiating a turn (27.9%) and technical nature of the trail (26.5%).

Similar to the student-athletes, there was no significant difference in overall injury proportions between female and male coaches (p = 0.624). The coaches’ injury event proportion was significantly lower than for student-athletes (0.8% vs. 3.0%, p < 0.001).

Discussion

The development and implementation of the NICA ISS was made possible by a number of factors, including the accelerating work of sports epidemiologists over the past 25 years, technological advances that allow for large scale data collection from nearly all locations, and a strong desire to protect the health of the riders. Just as the sport of mountain biking is not without risk, the development and implementation of this type of project is not without pitfalls. Nonetheless, a very efficient, nationwide ISS was successfully implemented with minimal technical issues. Extensive consultations with experts in sports epidemiology, comprehensive beta-testing of the system, and training of the Designated Reporters and others resulted in the acquisition of informative data regarding injuries.

Full completion of the injury report form was 100%, as all fields were required in order to submit the report. For the purposes of this study, exposure is defined as one student-athlete at one practice or race. No attempt was made to capture exposure data for coaches. Alternative ways to report exposure could include time riding, distance ridden, and vertical distance ridden. In order to acquire this information, riders would need GPS units, with GPS data synched to the NICA ISS. While this would make for more robust exposure information, and could include speed at time of crash, it is not yet technologically or financially feasible. Unfortunately, compliance with completing exposure reports was highly variable from team to team, and was insufficient to calculate injury incidence. The reason for this variability is under review. All Designated Reporters were provided with instructions on the importance of reporting exposure data, and this part of the ISS took less than one minute to complete each week once the Designate Reporter was familiar with it. Recognizing the importance of capturing exposure data,7, 12 additional efforts are underway to increase compliance with exposure reporting, referring to reporter compliance report available from another injury surveillance system.14

In contrast to exposure data, the quality of injury data is considered good, although formal data validation remains in the planning stages. All discrete entry fields of the injury report form are required, so there is no missing data in these fields. The Designated Reporters provided surprisingly informative accounts in the open-ended text entry fields. Formal analysis of the text entry fields is ongoing. The injury definition was aligned with similar systems,7, 15 and designed to exclude inconsequential injuries.

The existing literature on mountain biking injuries is modest but growing. Most reports primarily concern injuries in adult recreational riders.1, 5, 16–18 A small number of reports have focused on injuries in adult racers.19, 20 Some reports focused on disciplines other than NICA-sanctioned cross-country, such as downhill21 or injuries from terrain parks.22 Other reports have focused only on injuries that presented to emergency rooms.18, 23, 24 One review article focused on youth mountain bike injuries.25 To our knowledge, this is the first systematic, prospective study of injuries in the competitive youth mountain biking population.

The overall injury event proportion was relatively low for student-athletes (3.0%) and extremely low for coaches (0.8%). It is hard to directly compare these proportions with those of other youth sports as reporting methods are different, but they appear to be lower than injury proportions in youth basketball, soccer and American football.26 Concussion/possible concussion was the leading diagnosis in student-athletes. Discussions are underway to study factors leading to concussion and interventions to decrease concussion rates. Not surprisingly, upper limb injuries were more common than lower limb injuries in student-athletes, which is aligned with reports of mountain biking injuries in other populations.20, 24, 25, 27–29 Interestingly, injury patterns differ by sex in student-athletes, with females sustaining more lower limb injuries than males. Kronisch and colleagues30 also found differences in injury characteristics between males and females, but included downhill racing and adult data from 20 years ago. The evolution of the sport since then makes comparison to our data challenging. Differences in injury characteristics may reflect differences in the manner in which males and females fall. Video capture of injury events could elucidate these differences better, but presents practical challenges on mountain biking trails that cover many kilometers. One option for video capture of injury events is to identify sections of frequently used trails where crashes are common, and place video cameras at those location during practices or races. In contrast to the Kronisch study above, we found no significant difference in the overall injury event proportion between males and females, although there was a trend toward a higher injury event proportion in female student-athletes.

Many injuries were relatively minor, including abrasions and contusions, and less than one week of time loss. However, some injuries were more significant, including concussions/possible concussions, fractures and dislocations, and required four or more weeks of time loss. No catastrophic injuries such as death, spinal cord injury, or severe traumatic brain injury were reported. Efforts to prevent more severe injuries will be prioritized.

While the overall injury event proportion was lower for coaches than student-athletes, coaches appear to sustain more severe injuries. Coaches had more injuries per injury event (3.0% vs. 0.8% in student-athletes), more frequently required emergency evacuation from the crash site (58.8% vs. 44.4% in student-athletes), and were more likely to be admitted to a hospital (13.2% vs. 2.7% in student-athletes). The reasons for these findings are not yet known. NICA coaches are volunteer coaches whose experience level is varied. NICA has been implementing increasingly extensive efforts to train coaches on technique. A prospective study on the effect of coach training on injury occurrence in coaches and student-athletes is planned.

Several factors associated with injury occurrence and may inform future injury reduction interventions. More injuries occurred while riding downhill relative to riding on flat or uphill sections of trail. While it seems clear that improving riders’ downhill skills is important, close to half of all injuries occur on flat and uphill sections. Therefore, riders need to remain aware that injuries can occur on any trail incline. Rider inexperience and the technical nature of the trail was frequently reported to be associated with injury occurrence, emphasizing the need for additional training. The interactions between rider, bicycle, and trail have important implications for injury prevention,31 and warrant further study.

Limitations

This study is not without limitations. One limitation is that data are not always entered by medical personnel, but rather by a Designated Reporter on each team who may or may not be medically trained. The Designated Reporter is typically a coach or parent who has volunteered to respond to the weekly emails. Unfortunately, it is not practical to obtain formal medical records or have a medically trained individual complete the injury report forms for all teams. A second important limitation is that teams did not provide adequate exposure data during the first full year of data collection to allow for calculation of injury incidence. NICA is making extensive efforts to increase compliance with exposure reporting from all teams. A third important limitation is that it cannot be assured that all injuries meeting the inclusion criteria are reported, potentially causing an underestimate in the total number of injuries. However, teams are mandated by NICA to report all qualifying injuries for the purposes of insurance reporting as well as for the ISS, and frequent reminders are provided to coaches, Designated Reporters, parents, and student-athletes about complying with this mandate. Another limitation is that data validation has not yet been completed, but is planned for the future. Finally, the NICA ISS focuses on acute traumatic injuries, which are by far the majority of injuries in this sport. The inclusion of overuse injuries and medical illness remains under consideration.

Conclusion

An effective, nationwide injury surveillance system for injuries sustained in youth mountain bike racing was successfully implemented in 2018 across the United States. To our knowledge, this is the largest mountain biking ISS in the world. This ISS also tracks injuries in coaches, who ride with the student-athletes during practices but not races. The first year of data collection provided early insights into injury characteristics in this sport; these preliminary data need to be confirmed through subsequent years of data collection. Overall, student-athlete injury proportions are lower than those seen in many high school sports. The injury proportion for coaches is extremely low. Many injuries are relatively mild, including abrasions and contusions. Some injuries are more significant, including concussions/possible concussions, fractures and dislocations, and result in trips to an emergency room and sometimes hospital admission. Injury characteristics differ between student-athletes and coaches. Although coaches had an overall very low injury proportion, coaches sustained more injuries per injury event, had a higher percentage of fractures and dislocations, required emergency evacuation more frequently, had a higher percentage of hospital admissions, and greater time loss due. Injury proportions were similar between males and females, but both female student-athletes and coaches sustained lower limb injuries more than males.

Further research is needed to confirm these preliminary findings and look for trends as the sport changes. We plan on conducting longitudinal injury epidemiology research in this athlete population. The first prospective, controlled injury prevention study is planned for the 2020 fall season.

Supplementary Material

Practical Implications.

A nationwide youth mountain biking injury tracking system was successfully implemented in the United States.

This injury tracking system will allow for a better understanding of injuries that occur in youth mountain biking.

Information obtained will allow experts to design, implement and test data-driven strategies to decrease injuries in youth mountain bike racing.

Acknowledgements

There was no financial assistance with this study. The authors would like to thank all of the NICA student-athletes, coaches, parents and race officials, with particular gratitude to the Designated Reporters.

References

- 1.Bush K, Meredith S, Demsey D. Acute hand and wrist injuries sustained during recreational mountain biking: a prospective study. Hand 2013; 8(4):397–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Outdoor Foundation. Outdoor participation report 2017. https://outdoorindustry.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/2017-Outdoor-Recreation-Participation-Report_FINAL.pdf. Accessed 2018 March 22.

- 3.National Bicycle Dealers Association. Industry overview 2015: 2015 - The NBDA Statpak. https://nbda.com/articles/industry-overview-2015-pg34.htm. Accessed 2019 November 27.

- 4.Smith S Global mountain bike market 2017-2021. Elmhurst, IL: Technavio; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kronisch RL, Chow TK, Simon LM, et al. Acute injuries in off-road bicycle racing. Am J Sports Med 1996; 24(1):88–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ekegren CL, Gabbe BJ, Finch CF. Sports injury surveillance systems: a review of methods and data quality. Sports Med 2016; 46(1):49–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Finch CF. An overview of some definitional issues for sports injury surveillance. Sports Med 1997; 24(3):157–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dick R, Agel J, Marshall SW. National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance System commentaries: introduction and methods. J Athl Train 2007; 42(2):173–182. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kerr ZY, Dompier TP, Snook EM, et al. National collegiate athletic association injury surveillance system: review of methods for 2004–2005 through 2013–2014 data collection. J Athl Train 2014; 49(4):552–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kerr ZY, Comstock RD, Dompier TP, et al. The First Decade of Web-Based Sports Injury Surveillance (2004–2005 Through 2013–2014): Methods of the National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance Program and High School Reporting Information Online. J Athl Train 2018; 53(8):729–737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahmad CS, Dick RW, Snell E, et al. Major and Minor League Baseball Hamstring Injuries: Epidemiologic Findings From the Major League Baseball Injury Surveillance System. Am J Sports Med 2014; 42(6):1464–1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knowles SB, Marshall SW, Guskiewicz KM. Issues in estimating risks and rates in sports injury research. J Athl Train 2006; 41(2):207–215. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Willick SE, Webborn N, Emery C, et al. The epidemiology of injuries at the London 2012 Paralympic Games. Br J Sports Med 2013; 47(7):426–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Comstock RD, Yard EE, Knox CL, et al. Summary report: high school RIO (Reporting Information Online): internet-based surveillance of injuries sustained by US high school athletes. http://www.ucdenver.edu/academics/colleges/PublicHealth/research/ResearchProjects/piper/projects/RIO/Documents/2005-06.pdf. Accessed 2020 February 19.

- 15.Brant JA, Johnson B, Brou L, et al. Rates and patterns of lower extremity sports injuries in all gender-comparable US high school sports. Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine 2019; 7(10):DOI: 10.1177/2325967119873059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carmont MR. Mountain biking injuries: a review. Br Med Bull 2008; 85:101–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chow TK, Bracker MD, Patrick K. Acute injuries from mountain biking. West J Med 1993; 159(2):145–148. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roberts DJ, Ouellet JF, Sutherland FR, et al. Severe street and mountain bicycling injuries in adults: a comparison of the incidence, risk factors and injury patterns over 14 years. Can J Surg 2013; 56(3):E32–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chow TK, Kronisch RL. Mechanisms of injury in competitive off-road bicycling. Wilderness Environ Med 2002; 13(1):27–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kronisch RL, Pfeiffer RP. Mountain biking injuries: an update. Sports Med 2002; 32(8):523–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Becker J, Runer A, Neunhauserer D, et al. A prospective study of downhill mountain biking injuries. Br J Sports Med 2013; 47(7):458–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ashwell Z, McKay MP, Brubacher JR, et al. The epidemiology of mountain bike park injuries at the Whistler Bike Park, British Columbia (BC), Canada. Wilderness Environ Med 2012; 23(2):140–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim PT, Jangra D, Ritchie AH, et al. Mountain biking injuries requiring trauma center admission: a 10-year regional trauma system experience. J Trauma 2006; 60(2):312–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nelson NG, McKenzie LB. Mountain biking-related injuries treated in emergency departments in the United States, 1994–2007. Am J Sports Med 2011; 39(2):404–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aleman KB, Meyers MC. Mountain biking injuries in children and adolescents. Sports Med 2010; 40(1):77–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carter EA, Westerman BJ, Hunting KL. Risk of injury in basketball, football, and soccer players, ages 15 years and older, 2003–2007. J Athl Train 2011; 46(5):484–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rivara FP, Thompson DC, Thompson RS, et al. Injuries involving off-road cycling. J Fam Pract 1997; 44(5):481–485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ansari M, Nourian R, Khodaee M. Mountain biking injuries. Curr Sports Med Rep 2017; 16(6):404–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jeys LM, Cribb G, Toms AD, et al. Mountain biking injuries in rural England. Br J Sports Med 2001; 35(3):197–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kronisch RL, Pfeiffer RP, Chow TK, et al. Gender differences in acute mountain bike racing injuries. Clin J Sport Med 2002; 12(3):158–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barber J Using data to predict mountain bike trail conditions and improve trails. https://www.singletracks.com/blog/mtb-trails/using-data-to-predict-mountain-bike-trail-conditions-and-improve-trails/. Accessed 2018 March 16.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.