Abstract

Identification of medically relevant yeasts can be time-consuming and inaccurate with current methods. We evaluated PCR-based detection of sequence polymorphisms in the internal transcribed spacer 2 (ITS2) region of the rRNA genes as a means of fungal identification. Clinical isolates (401), reference strains (6), and type strains (27), representing 34 species of yeasts were examined. The length of PCR-amplified ITS2 region DNA was determined with single-base precision in less than 30 min by using automated capillary electrophoresis. Unique, species-specific PCR products ranging from 237 to 429 bp were obtained from 92% of the clinical isolates. The remaining 8%, divided into groups with ITS2 regions which differed by ≤2 bp in mean length, all contained species-specific DNA sequences easily distinguishable by restriction enzyme analysis. These data, and the specificity of length polymorphisms for identifying yeasts, were confirmed by DNA sequence analysis of the ITS2 region from 93 isolates. Phenotypic and ITS2-based identification was concordant for 427 of 434 yeast isolates examined using sequence identity of ≥99%. Seven clinical isolates contained ITS2 sequences that did not agree with their phenotypic identification, and ITS2-based phylogenetic analyses indicate the possibility of new or clinically unusual species in the Rhodotorula and Candida genera. This work establishes an initial database, validated with over 400 clinical isolates, of ITS2 length and sequence polymorphisms for 34 species of yeasts. We conclude that size and restriction analysis of PCR-amplified ITS2 region DNA is a rapid and reliable method to identify clinically significant yeasts, including potentially new or emerging pathogenic species.

Opportunistic fungal infections have increased dramatically in recent years, often as a result of advanced medical treatments (22, 33). Aggressive chemotherapy compromises patient immunity against fungal infections, and broad application of antifungal agents has been associated with the emergence of resistant strains (7). Coupled with the risk of nosocomial fungal infection (32), the rapid and accurate identification of etiological agents and resistant strains is crucial in medical centers caring for large groups of susceptible patients.

At least 150 fungal species have been identified as human pathogens and have been isolated from virtually all body sites (6). Identification of this increasing diversity of pathogens by conventional methods is often difficult and sometimes inconclusive (25). Morphological features and reproductive structures useful for identifying isolated fungi may take days to weeks to develop in culture, and evaluation of these characteristics requires expertise in mycology. Most fungal infections are caused by yeasts (21). Two commercial methods used to identify yeasts, the API and VITEK systems, require 2 to 3 days before biochemical reactions can be interpreted (5). In addition, their databases are limited (2, 24).

Molecular techniques utilizing amplification of target DNA provide alternative methods for diagnosis and identification (13). PCR-based detection of fungal DNA sequences can be rapid, sensitive, and specific (17). Coding regions of the 18S, 5.8S, and 28S nuclear rRNA genes evolve slowly, are relatively conserved among fungi, and provide a molecular basis of establishing phylogenetic relationships (31). Between coding regions are the internal transcribed spacer 1 and 2 regions (ITS1 and ITS2, respectively) which evolve more rapidly and may therefore vary among different species within a genus. Thus, PCR amplification may facilitate the identification of ITS region DNA sequences with sufficient polymorphism to be useful for identifying fungal species.

In this study, ITS2 sequence polymorphisms are evaluated for their specificity in identifying 34 species of pathogenic yeasts. Using universal primers complementary to the coding regions of the fungal rRNA genes, we amplified the ITS2 region from 27 type strains and over 400 clinical isolates. When determined with single-base-pair precision, the PCR product length alone identified 92% of the clinical isolates. Sequence analyses of ITS2 DNA from 93 isolates confirmed the specificity of this identification method, and phenotypic and ITS2-based identifications were concordant for >98% of the yeasts examined. Our data indicate ITS2 sequence polymorphisms are useful for identifying medically important yeasts and may facilitate taxonomic and phylogenetic classification of potentially new pathogenic species.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast isolates.

Four hundred and one clinical isolates (Table 1), collected from 30 October 1998 to 17 February 1999, six reference strains (Table 2) from the mycology laboratory at the University of Washington Medical Center, 22 type strains from the American Type Culture Collection, and five type strains from the Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures (Table 2) were included in this study. Eleven isolates of Candida dubliniensis were a gift from W. R. Kirkpatrick, University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio, Tex. (11). These 434 isolates represent 34 different species of pathogenic yeasts. Isolates were identified by either API 20C AUX strip or VITEK automated systems and by formation of true hyphae, pseudohyphae, blastoconidia, or chlamydoconidia on cornmeal-Tween 80 agar (10). Morphological evaluation of pseudohyphae was also used in distinguishing Candida species (14). The identities of 23 type strains were confirmed morphologically and biochemically (except Endomyces fibuliger, Pichia farinosa, Trichosporon cutaneum, and Trichosporon jirovecii which are not in either the API 20C or VITEK databases).

TABLE 1.

ITS2 region PCR products from clinical isolates

| Speciesa (no. of isolates) | Clinical isolates

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Product lengthb (mean bp) | SDc (bp) | Range (product length in bp)

|

||

| Minimum | Maximum | |||

| Yarrowia lipolytica (2) | 236.66 | 236.48 | 236.62 | |

| Candida lusitaniae (17) | 251.14 | 0.15 | 250.98 | 251.68 |

| Candida intermedia (1) | 255.10 | NAi | NA | |

| UWFP-348 (1)d | 269.57 | NA | NA | |

| Pichia ohmeri (1) | 269.98 | NA | NA | |

| Candida lambica (1) | 302.18 | NA | NA | |

| Candida parapsilosis (68) | 309.93 | 0.28 | 309.47 | 311.01 |

| Candida tropicalis (35) | 327.42 | 0.86 | 325.74 | 328.25 |

| Candida albicans (94) | 339.34e | 0.24 | 338.95 | 340.00 |

| Candida dubliniensis (14)f | 342.33e | 0.70 | 340.51 | 342.87 |

| Candida krusei (18) | 344.61 | 0.26 | 343.96 | 344.98 |

| Trichosporon mucoides (2)g | 349.30 | NA | NA | |

| Trichosporon inkin (1) | 353.27 | NA | NA | |

| Trichosporon asahii (2) | 355.87 | 355.75 | 355.98 | |

| UWFP-345 (1)d | 364.78 | NA | NA | |

| Cryptococcus neoformans (5) | 370.76 | 0.38 | 370.32 | 371.2 |

| Candida zeylanoides (2) | 371.65 | 371.31 | 371.99 | |

| Hansenula anomala (3) | 372.58 | 372.32 | 372.91 | |

| Candida guilliermondii (11) | 374.61 | 0.33 | 374.20 | 375.09 |

| Endomyces fibuliger (2) | 374.98 | 374.95 | 375.00 | |

| Candida famata (3) | 376.21 | 376.18 | 376.25 | |

| Pichia farinosa (2) | 379.18 | 379.16 | 379.19 | |

| Rhodotorula spp. (3)h | 400.38 | 400.00 | 400.64 | |

| Rhodotorula rubra (4) | 400.46 | 0.19 | 400.19 | 400.63 |

| Cryptococcus albidus (3) | 403.63 | 403.45 | 403.75 | |

| Candida glabrata (94) | 413.51 | 0.37 | 411.88 | 414.19 |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae (6) | 416.35 | 0.82 | 415.23 | 417.17 |

| Candida kefyr (4) | 427.88 | 0.26 | 427.65 | 428.23 |

| Cryptococcus uniguttulatus (1) | 428.73 | NA | NA | |

Identification of species by biochemical and morphological assessment. Number of isolates collected is indicated in parenthesis.

PCR product sizes determined by capillary electrophoresis as described in Materials and Methods.

Standard deviation is calculated for species with four or more strains.

Also see Table 4.

PCR product sizes of C. albicans and C. dubliniensis were statistically different (P < 0.001 by t test).

Ten strains obtained from the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio.

UWFP-366 and -367, also see Table 4.

UWFP-370, -373, and -380, also see Table 4.

NA, nonapplicable.

TABLE 2.

Length and sequence polymorphisms of ITS2 region DNA from clinical strains and type strains

| Species | Straina | PCR product lengthb (bp) | Sequenced PCR productc (bp) | % Identity with type strains | GenBank accession no. | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Candida albicans | ATCC 14053 | 339.12 | |||||

| Candida dubliniensis | UWFP-92, -104 | 342.65 | 343 | AF218993 | TSi | ||

| CBS 7987 | NTj | 156d | 100 | U96719 | 3 | ||

| Candida famata | CBS1795T | 376.59 | 381 | AF218984 | TS | ||

| UWFP-351, -352 | 376.19 | 381 | 100 | AF218984 | TS | ||

| ATCC 62894 | NT | 194e | 78.4 | U70500 | 15 | ||

| Candida freyschussii | ATCC 18737T | 347.27 | 351 | AF218965 | TS | ||

| Candida glabrata | ATCC 2001T | 413.16 | 417 | AF218966 | TS | ||

| UWFP-108, -109, -115, -186, -189, -190 | 413.63 | 419 | 99 | AF218994 | TS | ||

| UWFP-116, -118, -119, -122, -123 | 98.8 | AF219008 | TS | ||||

| UWFP-192 | 99.3 | AF218995 | TS | ||||

| ATCC 200989 | 412.47 | ||||||

| Y-65 | NT | 230 | 97.8 | U70498 | 15 | ||

| Candida guilliermondii | ATCC 6260T | 375.50 | 379 | AF218967 | TS | ||

| UWFP-195 | 375.09 | 379 | 99.7 | AF218996 | TS | ||

| Taxon: 4929 | NT | 379 | 95.5 | L47110 | |||

| Candida intermedia | ATCC 14439T | 255.75 | 258 | AF218968 | TS | ||

| UWFP-347 | 255.10 | 258 | 100 | AF218968 | TS | ||

| Candida kefyr | UWFP-208, -209 | 427.94 | 432 | AF218997 | TS | ||

| Taxon: 4911 | NT | 431f | 98.4 | L47107 | |||

| Candida krusei | UWFP-210, -211 | 344.55 | 347 | TS | |||

| Taxon: 4909 | NT | 347f | 100 | L47113 | |||

| Candida lambica | ATCC 24750T | 303.49 | 307 | AF218969 | TS | ||

| UWFP-346 | 302.18 | 307 | 99 | AF218998 | TS | ||

| ATCC 24750 | NT | 121e | 99.2 | U70505 | 15 | ||

| Candida lusitaniae | ATCC 34449T | 251.60 | 255 | AF218970 | TS | ||

| UWFP-227 | 251.20 | 255 | 100 | AF218970 | TS | ||

| ATCC 34449 | NT | 255 | 98 | AF009215 | TS | ||

| Candida pelliculosa | CBS605T | 372.91 | 375 | AF218991 | TS | ||

| Candida rugosa | ATCC 10571T | 270.99 | 274 | AF218971 | TS | ||

| ATCC 10571 | NT | 89e | 97.8 | U70506 | 15 | ||

| Candida tropicalis | ATCC 750T | 328.27 | 328 | AF218992 | TS | ||

| UWFP-321, -333 | 325.80 | 326 | 99.4 | AF219000 | TS | ||

| UWFP-327, -331 | 327.18 | 327 | 99.7 | AF219001 | TS | ||

| UWFP-313, -316 | 328.21 | 328 | 100 | AF218992 | TS | ||

| Taxon: 5482 | NT | 326 | 97 | L47112 | |||

| Candida utilis | ATCC 22023T | 362.34 | 364 | AF218990 | TS | ||

| Candida zeylanoides | ATCC 7351T | 372.07 | 374 | AF218976 | TS | ||

| UWFP-349 | 371.99 | 374 | 100 | AF218976 | TS | ||

| ATCC 7351 | NT | 187e | 97.3 | U70507 | 15 | ||

| Cryptococcus albidus | ATCC 10666T | 403.67 | 407 | AF218972 | TS | ||

| UWFP-357, -359 | 403.60 | 98 | AF219002 | TS | |||

| ATCC 34140 | 403.75 | ||||||

| Cryptococcus humicolus | ATCC 14438T | 353.17 | 355 | AF218973 | TS | ||

| ATCC 9949 | 352.94 | 355 | 99.2 | AF218999 | TS | ||

| Cryptococcus laurentii | ATCC 18803T | 362.33 | 364 | AF218974 | TS | ||

| Cryptococcus neoformans | ATCC 32045T | 370.95 | 374 | AF218975 | TS | ||

| UWFP-360, -361 | 370.64 | 374 | 99 | AF219003 | TS | ||

| ATCC 24067 | NT | 375 | 99.5 | L14068 | 4 | ||

| Cryptococcus uniguttulatus | CBS1730T | 428.90 | 432 | AF218985 | TS | ||

| UWFP-364 | 428.73 | 432 | 100 | AF218985 | TS | ||

| Endomyces fibuliger | CBS329.83T | 374.86 | 378 | AF218988 | TS | ||

| UWFP-397, -398 | 374.98 | 378 | 100 | AF218988 | TS | ||

| ATCC 36213 | 375.53 | 378 | 100 | AF218988 | TS | ||

| 8014 | NT | 318e | 100 | U10409 | TS | ||

| Hansenula anomala | UWFP-396 | 372.52 | 375 | AF218991 | TS | ||

| ATCC 8168 | NT | 188d | 100 | U96720 | 3 | ||

| Pichia farinosa | CBS-185T | 379.45 | 382 | AF218989 | TS | ||

| UWFP-389, -390 | 379.18 | 382 | 100 | AF218989 | TS | ||

| Pichia ohmeri | ATCC 46053T | 268.84 | 271 | AF218977 | TS | ||

| UWFP-388 | 269.98 | 272 | 99.6 | AF219004 | TS | ||

| ATCC 20216 | NT | 196e | 91.8 | AF022721 | TS | ||

| Rhodotorula glutinis | ATCC 37265T | 390.93 | 395 | AF218986 | TS | ||

| Rhodotorula rubra | ATCC 32763T | 400.00 | 404 | AF218978 | TS | ||

| UWFP-371, -372, -374 | 400.55 | 404 | 100 | AF218978 | TS | ||

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | UWFP-387 | 415.23 | 419 | 97g | AF219005 | TS | |

| UWFP-382, -384, -385 | 416.18 | 420 | 97g | AF219006 | TS | ||

| UWFP-383, -386 | 417.17 | 421 | 97g | AF219007 | TS | ||

| IFO10217 | NT | 421 | D89886 | 19 | |||

| Sporobolomyces salmonicolor | ATCC 36400T | 400.19 | 401 | AF218979 | TS | ||

| Trichosporon asahiih | UWFP-391, -392 | 355.87 | 358 | AF245218 | TS | ||

| M9474 | NT | 358 | 99.4 | AB018014 | 26 | ||

| Trichosporon cutaneum | ATCC 28592T | 350.00 | 353 | AF218980 | TS | ||

| CBS2466 | NT | 296e | 100 | AB018020 | 27 | ||

| Trichosporon inkin | ATCC 18020T | 353.32 | 358 | AF218981 | TS | ||

| UWFP-399 | 353.27 | 358 | 100 | AF218981 | TS | ||

| CBS5585 | NT | 301e | 100 | AB018024 | 27 | ||

| Trichosporon jirovecii | ATCC 34499T | 349.89 | 352 | AF218982 | TS | ||

| CBS6864 | NT | 295e | 100 | AB018025 | 27 | ||

| Yarrowia lipolytica | ATCC 18942T | 236.93 | 240 | AF218983 | TS | ||

| UWFP-400, -401 | 236.66 | 240 | 100 | AF218983 | TS | ||

| ATCC 9773 | 236.88 | 240 | 100 | AF218983 | TS |

UWFP, University of Washington Fungal Project; ATCC, American Type Culture Collection; CBS, Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures; IFO, Institute of Fermentation; ATCC type strains are labeled with superscript T.

PCR product length determined with capillary electrophoresis as described in Materials and Methods.

Exact number of nucleotides determined by direct sequencing of the PCR products.

Partial sequence compared to ITS2 region DNA sequences from clinical strains in this study.

Partial sequence compared to ITS2 region DNA sequences from type strains in this study.

Sequence compared to ITS2 region DNA sequences from clinical strains in this study.

ITS2 region DNA sequence compared with D89886.

T. asahii identified as such by the API 20C and as T. beigelii by the VITEK system.

TS, this study.

NT, not tested.

Yeasts were subcultured onto Sabouraud dextrose agar plates (BBL-Emmon's Mod, Cockeysville, Md.) and were incubated at 30°C for 2 days, and DNA was extracted by using a modified heat extraction method (17). Briefly, 2-day-old yeast colonies in 100 μl of lysis buffer (100 mM Tris, 30 mM EDTA, 0.5% [wt/vol] sodium dodecyl sulfate, pH 7.5) were vortexed briefly and incubated at 100°C for 15 min. One hundred microliters of 2.5 M potassium acetate was added, and the suspension was incubated on ice for 1 h and centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 5 min. The supernatant was transferred to a new tube, an equal volume of isopropanol was added, and the suspension was centrifuged for 5 min. The supernatant was then decanted, 500 μl of 100% ethanol was added, and the suspension was centrifuged for 20 min. The supernatant was decanted, and the extracted DNA was dried in a Speed Vac, resuspended in 100 μl of sterile pharmacy water (Sterile Water for Irrigation; USP-Baxter, Deerfield, Ill.), and stored at −20°C.

PCR and DNA sequencing.

ITS2 region DNA was PCR amplified from a 1:50 dilution of template DNA in 1× PCR buffer containing 3 mM MgCl2, 0.04 U of AmpliTaq DNA Polymerase (Perkin-Elmer Corporation, Foster City, Calif.) per μl, 200 μM of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (Pharmacia Biotech), 900 μM primer ITS3 (5′-GCATCGATGAAGAACGCAGC-3′) (GIBCO BRL, Grand Island, N.Y.), and 300 μM primer ITS4 (5′-TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3′) (16) in sterile pharmacy water. The ITS4 primer was labeled with fluorescent dye, NED (Perkin Elmer), FAM, or HEX (SYNTHEGEN, Houston, Tex.). The DNA Thermal Cycler (model 9700; PE Applied Biosystems) was set to the following parameters: 95°C for 6 min, followed by 25 cycles at 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s, followed by one extension at 72°C for 10 min.

To determine the size of fluorescently labelled PCR products, two parts PCR product and one part of GS-500 ROX size standard (Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems, Warrington, England) were added to deionized formamide (AMRESCO, Solon, Ohio), denatured at 95°C for 3 min, placed on ice for at least 2 min, and injected into a 47-cm by 50-μm capillary column containing the high-performance polymer 4 in the ABI 310 genetic analyzer, an automated fluorescence capillary electrophoresis system (PE Applied Biosystems) utilizing denaturing conditions. Electrophoresis parameters were set on the instrument at 5-s injection time, 15 kV injection voltage, 15 kV electrophoresis voltage, and a constant temperature of 60°C. The average electrophoresis time was 30 min to ensure detection of product sizes below 500 bp, and PCR product lengths were determined by using the ABI310 GeneScan software (PE Applied Biosystems).

To sequence ITS2 region PCR products, unlabeled ITS3 and ITS4 primers were used to sequence both the forward and reverse strands, respectively, and each sequence (listed in Table 2) was repeated at least in duplicate. PCR products were filtered by using a Microcon column (YM-100; Amicon, Inc., Beverly, Mass.) and were resuspended in approximately 85 μl of sterile pharmacy water. Cycle sequencing was performed with the Ready-Reaction mix (ABI PRISM BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction Kit; PE Applied Biosystems) according to manufacturer's instructions on a PE thermocycler, Model 9700, by using the preprogrammed BigDye cycling parameters on the instrument. Each sequencing product was concentrated to dryness using a Speed Vac after removing excess DyeDeoxyR terminators with CENTRI-SEP columns (Princeton Separations, Adelphia, N.J.). Each sequencing product was resuspended in 20 μl of the template suppression reagent (PE Applied Biosystems) and was incubated at room temperature for approximately 10 min, heated at 95°C for 2 to 5 min, and placed on ice for 3 min. Using a 47-cm by 50-μm capillary containing the high-performance polymer 6, each sample could be sequenced in 1 h on the ABI PRISM 310 Genetic Analyzer.

Sequence similarity and phylogenetic analyses.

Sequences were assembled and edited with the Sequencher program (version 3.1). Multiple sequence alignment was performed by using CLUSTAL_X (28) with a gap opening penalty value of 20 and the default gap extension penalty value of 6.66. The multiple alignment output from CLUSTAL_X was imported and manually edited with the Java alignment editor, Jalview (version 1.3b) (M. Clamp, European Bioinformatics Institute [http://circinus.ebi.ac.uk:6543/jalview/]). Pairwise sequence comparisons were expressed as the percentage of the total number of nucleotide differences divided by the total number of positions. Phylogenetic analysis was performed by using the phylogeny inference package, PHYLIP (version 3.573) (J. Felsenstein, Department of Genetics, University of Washington, Seattle [http://evolution.genetics.washington.edu/phylip.html]), with three treeing algorithms: neighbor-joining, Fitch-Margoliash, and maximum likelihood (18). Pneumocystis carinii was used as the outgroup. The branching orders of the Fitch-Margoliash and the neighbor-joining dendrograms were evaluated with 1,000 bootstrap analyses using the SEQBOOT program in PHYLIP.

RESULTS

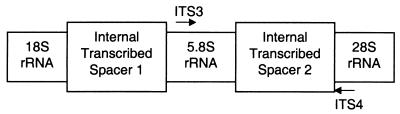

Approximately 128 bp of the 5.8S rRNA gene, the entire ITS2 region, and approximately 59 bp of the 28S rRNA gene can be amplified from fungal template DNA by using one primer pair (Fig. 1) (15, 16). The PCR products amplified from 17 yeast species (including nine from the same genus) appeared as single bands from 200 to 500 bp on a 1% agarose gel (data not shown). This suggested that related species could be distinguished by length polymorphisms in their ITS2 region DNA. To test this hypothesis, we utilized fluorescence capillary electrophoresis to more precisely measure the length of ITS2 region PCR products amplified from a large number of yeasts: 401 clinical isolates, 6 reference strains, and 27 type strains representing 34 species of yeasts.

FIG. 1.

ITSs are noncoding regions flanked by the structural rRNA genes. Approximate binding sites of the ITS3 and ITS4 PCR primers are shown by arrows.

ITS2 length polymorphisms.

ITS2 region PCR products from clinical isolates ranged in size from 237 bp (Yarrowia lipolytica) to 429 bp (Cryptococcus uniguttulatus, Table 1). Product lengths were measured for 434 yeasts and for multiple isolates in at least two separate PCRs: Candida albicans (n = 46), Candida glabrata (n = 36), Candida tropicalis (n = 27), Candida parapsilosis (n = 23), Candida krusei (n = 15), Candida lusitaniae (n = 15), C. dubliniensis (n = 13), Candida famata (n = 3), Saccharomyces cerevisiae (n = 3), Candida zeylanoides (n = 2), Rhodotorula rubra (n = 2), and one isolate each of C. lambica, Candida intermedia, Cryptococcus neoformans, Cryptococcus humicolus, C. uniguttulatus, Pichia ohmeri, Pichia farinosa, Trichosporon asahi, Y. lipolytica, E. fibuliger, and Trichosporon inkin. Between-run standard deviations of the mean PCR product length from 14 isolates of C. albicans were 0.07, 0.17, and 0.31 bp in a series of separate PCRs. Standard deviations for 11 species with ≥4 isolates ranged from 0.15 to 0.38 bp (Table 1). Interstrain variation (see below) contributed to higher standard deviations observed for products from C. dubliniensis (0.70 bp), C. tropicalis (0.86 bp), and S. cerevisiae (0.82 bp). Thus, the length of PCR products can be determined with single-base precision by using capillary electrophoresis.

Ninety-two percent of the clinical isolates (368 of 401 strains), comprising 17 species, produced distinct and species-specific ITS2 PCR products which differed in mean length by ≥2 bases (Table 1). Eleven isolates were correctly reidentified because their ITS2 PCR product length did not agree with their initial designation: new identities were confirmed by biochemical and morphological phenotypes. Four of these misidentifications failed to distinguish C. dubliniensis from C. albicans (data not shown); these closely related organisms were reliably identified by ITS2 region PCR product length alone (Table 1). Confirming these data, the PCR product lengths from clinical isolates correlated well with those from their respective type strains (Table 2) and differed by only 0.05 to 0.85 bp, except for Candida lambica (1.31 bp) and P. ohmeri (1.14 bp).

Seventeen species and one unknown clinical isolate, UWFP-348, could be divided into eight groups with ≤2-base difference in the mean length of their ITS2 region PCR products (Tables 1 and 2): T. cutaneum and T. jirovecii; C. famata, Candida guilliermondii, and E. fibuliger; T. inkin and C. humicolus; R. rubra and Sporobolomyces salmonicolor; Hansenula anomala, C. zeylanoides, and C. neoformans; Candida utilis and Cryptococcus laurentii; C. uniguttulatus and Candida kefyr; and P. ohmeri and UWFP-348.

ITS2 sequence polymorphisms.

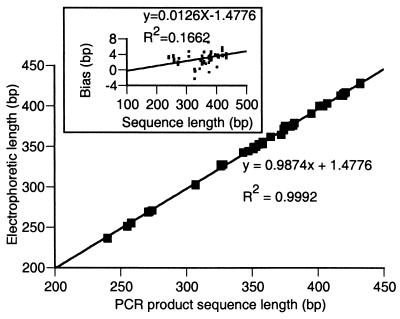

The DNA sequences of ITS2 region PCR products from 66 clinical strains and 27 type strains were analyzed to confirm the specificity of length polymorphisms for identifying yeasts and to resolve our other findings: three species displayed mean product lengths with standard deviations ≥0.5 bases, and eight groups of species produced products differing in mean length by ≤2 bases. To reduce the possibility of errors, sequence was obtained directly from both strands of the PCR products, and each strain was either sequenced twice or confirmed by two or more strains with the same sequence (Table 2). The length of the PCR product determined by capillary electrophoresis showed excellent correlation (R2 = 0.9992) with the actual number of nucleotides enumerated by direct sequencing (Fig. 2). The single-base precision of this method (see above) allowed us to determine that the PCR fragment sizes determined by GeneScan were slightly shorter than the actual sizes determined by sequencing, with a small proportional bias (Fig. 2, inset). Although similar discrepancies have been observed by others using capillary electrophoresis (9), our data demonstrate both the precision and accuracy of this technique for determining length polymorphisms among PCR products.

FIG. 2.

ITS2 region PCR product length as determined by capillary electrophoresis versus actual PCR product length as determined by direct sequencing. Eighty-nine independent length determinations plotted against actual length reveals a small underestimate of actual PCR product size by capillary electrophoresis, with a small proportional bias (inset, actual length minus length determined by electrophoresis versus actual sequence length).

ITS2 region DNA from clinical strains of C. famata, C. intermedia, C. lusitaniae, C. zeylanoides, C. uniguttulatus, E. fibuliger, P. farinosa, R. rubra, T. inkin, and Y. lipolytica had 100% sequence similarity compared with their type strains. Similarity between the type and clinical strains of C. guilliermondii, P. ohmeri, C. tropicalis, C. humicolus, C. lambica, and C. neoformans exceeded 99% (Table 2). H. anomala and Candida pelliculosa had identical sequences since they are the teleomorphic (sexual) and anamorphic (asexual) forms of the same organism (30). Thus, ITS2 region sequence similarity exceeded 99% among members of a single species (Table 2), except for C. glabrata (98.8 to 99.3%) and Cryptococcus albidus (98.0%).

The exception among C. glabrata resulted from a 417-base product from the type strain which differed from clinical strains at up to five nucleotide positions. In contrast, the three sequences found among 12 clinical strains were 419 bp (Table 2) and 99.5 to 99.8% similar to each other (data not shown). Six clinical isolates of S. cerevisiae displayed products of 421, 420, or 419 bp with 99.3 to 99.8% similarity to each other, versus 97% similarity to a published ITS2 sequence from S. cerevisiae (Table 2). Similarly, two clinical isolates of C. albidus were identical but 98% similar to their type strain (Table 2). Together with length variation observed among six clinical strains of C. tropicalis (Table 2), these data indicate ≥99% similarity in ITS2 region DNA exists among recent clinical isolates of the same species and that intraspecific polymorphism occurs in this region for some species.

Seventeen species and one isolate, UWFP-348, could be divided into eight groups with ITS2 region PCR products ≤2 bases apart in mean length (Table 3). Products in each group contained species-specific ITS2 region DNA: sequence similarities ranged from 65.1 to 97.7%, and products were easily distinguished from each other by unique restriction patterns after digestion with AseI, BanI, EcoRI, HincII, or StyI (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Species-specific ITS2 region PCR products with similar lengths can be distinguished by unique restriction patterns

| Speciesa | PCR product sizeb (bp) | No. of nucleotides from sequencec (bp) | Sequence similarity (%)f | Restriction fragments (bp)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AseI | BanI | EcoRI | HincII | StyI | ||||

| UWFP-348 | 269.57 | 271 | 65.1 | 271 | ||||

| P. ohmeri | 269.98 | 272 | 191/81 | |||||

| T. jiroveciiT | 349.89 | 352 | 97.7 | 352 | ||||

| T. cutaneumT | 350.00 | 353 | 249/104 | |||||

| C. humicolusT | 353.17 | 355 | 85.8 | 355 | ||||

| T. inkin | 353.27 | 358 | 249/109 | |||||

| C. laurentiiT | 362.33 | 364 | 67.6 | 48/316 | 364 | |||

| C. utilisT | 362.34 | 364 | 364 | 177/187 | ||||

| C. neoformans | 370.76 | 374 | 70.3d | 48/326 | 374 | |||

| C. zeylanoides | 371.65 | 374 | 82.7d | 374 | 260/114 | |||

| H. anomalad (C. pelliculosaT) | 372.58 | 375 | 375 | 177/198 | ||||

| E. fibuliger | 375.16 | 378 | 73.9e | 315/63 | 378 | |||

| C. guilliermondii | 374.61 | 379 | 91.8e | 379 | 227/152 | |||

| C. famata | 376.19 | 381 | 381 | 381 | ||||

| S. salmonicolorT | 400.19 | 401 | 83.4 | 48/79/274 | 401 | |||

| R. rubraT | 400.00 | 404 | 48/226/130 | 89/315 | ||||

| C. kefyr | 427.88 | 432 | 66.4 | 432 | 176/256 | 432 | ||

| C. uniguttulatus | 428.73 | 432 | 48/384 | 432 | 89/207/136 | |||

Superscript T indicates type strains.

From Table 2.

Sequence similarity between C. neoformans and C. zeylanoides was 70.3% and was 82.7% between C. zeylanoides and H. anomala. H. anomala and C. pelliculosa are the teleomorphic and anamorphic forms of the same organism, respectively.

Sequence similarity between E. fibuliger and C. guilliermondii was 73.9% and was 91.8% between C. guilliermondii and C. famata.

Sequence similarity with the species immediately following with similarly sized PCR products is indicated.

In total, 434 isolates were analyzed in this study, and 427 (98.4%) had concordant identification by phenotypic, biochemical, and ITS2-based methods. Forty-three species-specific ITS2 region DNA sequences were submitted to GenBank (Table 2).

Unusual isolates identified by ITS2 sequence polymorphisms.

Seven clinical isolates provided discrepant data for phenotypic and ITS2-based identification: the observed ITS2 region PCR product length was not the expected length predicted by the biochemical phenotype of each isolate (Table 4). Observed ITS2 region sequences also differed from expected, and their similarity ranged from 57.5 to 100%.

TABLE 4.

Unusual isolates identified by ITS2 region DNA sequence polymorphisms

| Unknown isolates | Identification by commercial systems

|

Expected PCR product mean length based on biochemical identificationb (bp)

|

Observed PCR product sizec (bp) | Sequence similarity (%) between unknown isolates and type strains predicted by biochemical phenotype(s)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| APIa | VITEK | API | VITEK | API | VITEK | ||

| UWFP-345 | C. utilis | Unidentifiable | 362.34 | 364.78 | 79.3 | ||

| C. pelliculosa | 372.91 | 82.9 | |||||

| UWFP-348 | C. rugosa | C. guilliermondii | 270.99 | 375.50 | 269.57 | 62.8 | 57.5 |

| UWFP-366d | C. humicolus | C. laurentii | 353.17 | 362.33 | 349.43 | 91.0 | 79.4 |

| T. mucoides | Not testede | 100 | |||||

| UWFP-367d | C. humicolus | C. humicolus | 353.17 | 353.17 | 349.30 | 91.0 | 91.0 |

| T. mucoidese | Not testede | 100 | |||||

| UWFP-370 | C. guilliermondii | R. glutinis | 375.50 | 390.93 | 400.00 | 67.6 | 91.1 |

| UWFP-373, -380 | C. guilliermondii | R. glutinis | 375.50 | 390.93 | 400.31 | 68.1 | 90.8 |

| C. famata | 376.59 | 66.3 | |||||

Isolates UWFP-366 and -367 biochemically resembled C. laurentii, C. humicolus, and Trichosporon mucoides (Table 4). Type strains of these yeasts displayed ITS2 region similarities of 79.4, 91, and 100%, respectively, when compared to UWFP-366 and -367. Our observations (Table 2) and the work of others (26) indicate conspecific strains generally have fewer than 1% nucleotide substitutions in ITS2 region DNA, and we conclude that UWFP-366 and -367 are probably isolates of T. mucoides. Also of interest, two clinical strains identified as Trichosporon beigelii by the VITEK system (Trichosporon asahii, Table 1) had identical ITS2 region sequences which were >99% similar to sequences of T. asahii, Trichosporon ovoides, and T. inkin (26). These isolates were identified by the API 20C system as T. asahii. However, note that T. ovoides is not part of the API 20C database.

Isolates UWFP-370, -373, and -380 biochemically resembled C. guillermondii, C. famata, and Rhodotorula glutinis (Table 4), and type strains of these yeasts displayed 66.3 to 91.1% sequence similarity with UWFP-370, -373, and -380. Although identity of these strains will require additional studies, their ITS2 region sequences most closely resembled those of R. rubra (99.5% similarity for UWFP-370 and 99.3% similarity for UWFP-373, and -380).

The remaining isolates, UWFP-345 and -348, displayed ≤83% ITS2 region sequence similarity with the type strains predicted from their respective biochemical phenotypes (Table 4). Previous observations indicate ITS2 similarities less than 95% correspond to nuclear DNA complementarity of less than 20% (26). Nuclear DNA complementarity among different species is less than 40%, varieties or subspecies display 40 to 80%, and members of a biological species generally exceed 80% (23). These isolates are therefore very likely to be species absent from the current ITS2 region databases (GenBank, EMBL, DDBJ, and Table 2).

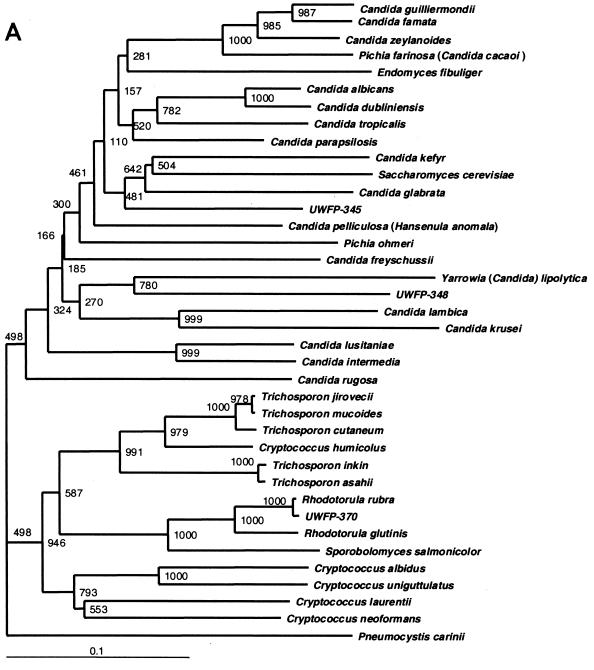

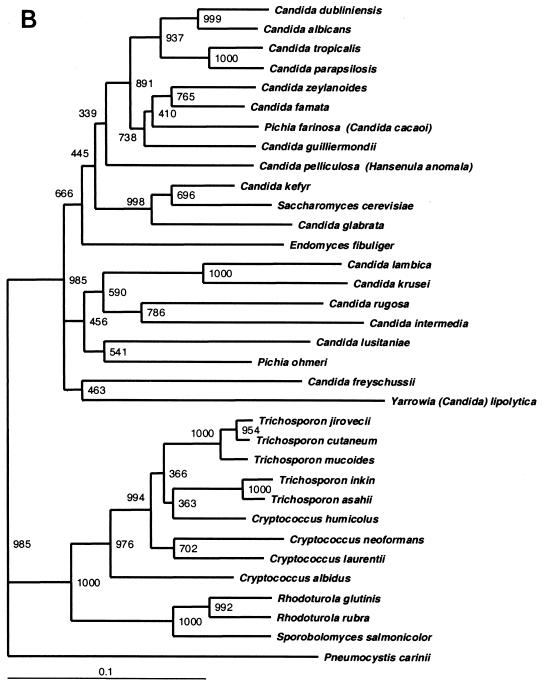

These data are supported by the phylogenetic trees constructed with ITS2 region sequences (Fig. 3A) by using different treeing algorithms. The global tree topology among the different treeing methods was very similar (data not shown) with species from each genus generally segregating into a distinct cluster; however, the local topology within the major clusters varied slightly. Moreover, the phylogenetic positions of the clinical strains which remained phenotypically unidentified could be inferred. UWFP-345 was most closely related to C. glabrata, C. kefyr, and S. cerevisiae with 73.6, 72.5, and 66% ITS2 region DNA similarity, respectively. UWFP-348 also clustered with other Candida spp. but displayed only 63.1% ITS2 region DNA similarity to Y. lipolytica. (Candida lipolytica). ITS2-based trees also supported the clustering of UWFP-370, -373, and -380 with Rhodotorula spp. (Fig. 3A). Similar phylogenetic relationships were observed in trees constructed with 26S rDNA sequences (Fig. 3B) and with the limited number of 18S rDNA sequences available for the species we examined (data not shown). However, ITS2 sequences provided better resolution of the genera Trichosporon and Cryptococcus.

FIG. 3.

(A) ITS2 sequence-based phylogenetic tree of clinical yeast isolates. Neighbor-joining dendrogram with 1,000 bootstraps was based on 463 aligned positions of complete ITS2 sequences and adjacent partial sequences of 5.8S and 28S rRNA genes from 38 yeast isolates, including 26 type strains. The P. carinii ITS2 sequence retrieved from GenBank (accession no. U07226) was used as the outgroup, and sequences of C. albicans and C. parapsilosis were previously published (GenBank accession no. L28817 and U10988, respectively). UWFP-373 and UWFP-380 have 100% identical sequence to UWFP-370. UWFP-373 and -380 were therefore not included in the tree. (B) 26S sequence-based phylogenetic tree showing the relationships of 34 yeast taxa. Neighbor-joining dendrogram was based on 557 aligned positions of the 5′ end of 26S rRNA gene. Sequences with the following accession numbers were retrieved from GenBank: C. albicans, no. U45776; C. dubliniensis, no. AB031020; C. famata, no. U94927; Candida freyschussii, no. AF017242; C. glabrata, no. U44808; C. guilliermondii, no. U45709; C. intermedia, no. U44809; C. kefyr, no. U94924; C. krusei, no. U76347; C. lambica, no. U75726; C. lusitania, no. U44817; C. parapsilosis, no. U45754; Candida rugosa, no. U45727; C. tropicalis, no. U45749; C. zelanoides, no. U45832; C. albidus, no. AF137605; C. humicolus, no. AF189854; C. laurentii, no. AF075469; C. neoformans, no. AF189845; E. fibuliger, no. U40089; H. anomala, no. U74592; P. farinosa, no. U45739; P. ohmeri, no. U45702; R. glutinis, no. AF070430; R. rubra, no. AF189961; S. cerevisiae, no. U44806; S. salmonicolor, no. AF189979; T. asahii, no. AF105393; T. cutaneum, no. AF075483; T. inkin, no. AF105396; T. jirovecii, no. AF105398; T. mucoides, no. AF075515; Y. lipolytica, no. U40080; and P. carinii, no. M86760 used for outgroup. Lower bars indicate the genetic distance. Numbers at each node indicate percent bootstrap values.

DISCUSSION

By examining 401 clinical isolates, 6 reference strains, and 27 type strains, we demonstrated that ITS2 region sequence polymorphisms can be used to identify 34 species of pathogenic yeasts. ITS2 region PCR product lengths were rapidly determined with single-base precision by using capillary electrophoresis and were sufficient to identify 92% of the clinical isolates in this study. The remaining isolates produced ITS2 region PCR products with similar mean lengths (≤2 bases apart) and were distinguished by restriction enzyme analysis. These species-specific ITS2 region polymorphisms were confirmed by sequence analysis of 93 isolates. Thus, of 434 isolates examined, 427 (>98%) had concordant identification by phenotypic and ITS2-based methods.

Our results confirm and extend the work of Turenne et al. (29), demonstrating ITS2 length polymorphisms among a collection of molds and yeasts. Their study examined 26 clinical isolates and a large number of reference strains, but they did not observe intraspecies variability when more than one strain was examined. In contrast, we found intraspecies variability and clinical isolates that were more similar to each other than they were to their respective type strains (Table 2). We also identified eight groups of species whose PCR product lengths were sufficiently similar that restriction analysis was required for specific identification (Table 3). These observations indicate that strain variability is an important consideration for applying this method in the clinical laboratory and underscores the importance of including clinical isolates when developing new diagnostic methods. For example, by examining a large number of strains, we confirmed that ITS2 region PCR product length alone can reliably distinguish C. albicans and C. dubliniensis (Table 1). Because these organisms produce germ tubes and share biochemical characteristics (1), C. dubliniensis is easily misidentified as C. albicans (20). Xylose assimilation distinguishes C. albicans (88 to 90% positive) and C. dubliniensis (0% positive), but is not 100% reliable (I. F. Salkin, W. R. Pruitt, A. A. Padhye, D. Sullivan, D. Coleman, and D. H. Pincus, Letter, J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:1467, 1998) and takes 2 to 3 days (5). Since C. dubliniensis is more likely than C. albicans to develop resistance to fluconazole, misidentification can impact the outcome of antifungal treatment (27).

Our results also agree with the examination of the ITS1 and ITS2 regions of Trichosporon spp. by Sugita et al. (26). They also found intraspecies or strain-specific sequence variability in the ITS2 region and, with rare exceptions, documented that different species contain ITS2 region DNA with less than 99% sequence similarity. Our results extend these observations to a broader population of clinically relevant yeasts, including members of the basidiomycetes (Cryptococcus, Rhodotorula, Sporobolomyces, and Trichosporon spp.) and ascomycetes (Table 2 and Fig. 3A).

The difficulty commercial systems have with identifying some yeast species (2, 5) was evident for seven isolates in our study (Table 4) and demonstrates the potential usefulness of sequence-based identifications. Two isolates likely to be T. mucoides were correctly suggested as one of two possible identifications by the API system and were incorrectly designated as Cryptococcus spp. by the VITEK; the genus of three probable Rhodotorula spp., closely related to R. rubra, was correctly suggested by the VITEK system but designated as Candida spp. by the API; and two isolates were either unidentifiable (VITEK) or incorrectly designated as Candida spp. (API and VITEK) (Table 4). Sequence analysis of these isolates confirmed that the ITS2 region length polymorphisms correctly resolved discrepant results between phenotypic and genotypic methods (Table 4), and phylogenetic trees constructed with the available ITS2 sequences provided additional support for the genotypic data (Fig. 3A).

In general, the topology of a phylogenetic tree depends on the characteristics of DNA sequences and tree construction algorithms utilized (18). The global topology of trees constructed with ITS2, 26S, and 18S rDNA sequences displayed striking similarities (Fig. 3A and B). Our ITS2-based trees displayed generally good bootstrap support at terminal branches, distinguishing different species, and provided better distinction of the genera Cryptococcus and Trichosporon. Interestingly, we found that C. humicolus clustered with the Trichosporon clade in trees constructed with both ITS2 and 26S rDNA sequences as noted previously by others (8). However, the bootstrap support at the basal branches was stronger with 26S and 18S rDNA trees when compared to ITS2. The branching pattern of the more basal lineages within each cluster differed among ITS2, 26S, and 18S rRNA gene-based phylogenetic trees. These results were expected, as the bootstrap values at the basal branches within the major clusters were low with all three markers. This observation has also been made by others (26), and the most accurate phylogenetic relationships may be provided by the less rapidly evolving structural rRNA genes (12, 18). However, the ability to evaluate short ITS2 region amplicons with sufficient polymorphism to distinguish yeast species provides advantages as a diagnostic method. Analysis is rapid and amenable to automated methods as demonstrated here and by others (29), and the polymorphisms are sufficient that array-based hybridization schemes will be useful analytical tools in the future. Our data establish an initial database of ITS2 length and sequence polymorphisms for 34 species of yeasts that is validated with over 400 clinical isolates, and we anticipate that this will facilitate the rapid diagnosis of fungal infections directly from patient specimens.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bikandi J, Millan R S, Moragues M D, Cebas G, Clarke M, Coleman D C, Sullivan D J, Quindos G, Ponton J. Rapid identification of Candida dubliniensis by indirect immunofluorescence based on differential localization of antigens on C. dubliniensis blastospores and Candida albicans germ tubes. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2428–2433. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.9.2428-2433.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dooley D P, Beckius M L, Jeffrey B S. Misidentification of clinical yeast isolates by using the updated Vitek Yeast Biochemical Card. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2889–2892. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.12.2889-2892.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elie C M, Lott T J, Reiss E, Morrison C J. Rapid identification of Candida species with species-specific DNA probes. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:3260–3265. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.11.3260-3265.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fan M, Currie B P, Guttell B P, Ragan M A, Casadevall A. The 16S-like, 5.8S, and 23S-like rRNA's of the two varieties of Cryptococcus neoformans: sequence, secondary structure, phylogenetic analysis, and restriction fragment polymorphisms. J Med Vet Mycol. 1994;32:163–180. doi: 10.1080/02681219480000231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fenn J P, Segal H, Barland B, Denton D, Whisenant J, Chun H, Christofferson K, Hamilton L, Carroll K. Comparison of updated Vitek Yeast Biochemical Card and API 20C yeast identification systems. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1184–1187. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.5.1184-1187.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fromtling R A. Mycology. In: Murray P R, Baron E J, Pfaller M A, Tenover F C, Yolken R H, editors. Manual of clinical microbiology. 6th ed. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1995. pp. 697–855. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gleason T G, May A K, Caparelli D, Farr B M, Sawyer R G. Emerging evidence of selection of fluconazole-tolerant fungi in surgical intensive care units. Arch Surg. 1997;132:1197–1201. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1997.01430350047008. . (Discussion, 1202.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gueho E, Improvisi L, Christen R, de Hoog G S. Phylogenetic relationships of Cryptococcus neoformans and some related basidiomycetous yeasts determined from partial large subunit rRNA sequences. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1993;63:175–189. doi: 10.1007/BF00872392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hernandez S M, Morlock G P, Butler W R, Crawford J T, Cooksey R C. Identification of Mycobacterium species by PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism analyses using fluorescence capillary electrophoresis. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3688–3692. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.11.3688-3692.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kern M E, Blevins K S. Medical mycology: a self-instructional text. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Jean-François Vilain; 1997. pp. 146–152. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kirkpatrick W R, Revankar S G, McAtee R K, Lopez-Ribot J L, Fothergill A W, McCarthy D I, Sanche S E, Cantu R A, Rinaldi M G, Patterson T F. Detection of Candida dubliniensis in oropharyngeal samples from human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients in North America by primary CHROMagar candida screening and susceptibility testing of isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:3007–3012. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.10.3007-3012.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kurtzman C P, Robnett C J. Identification and phylogeny of ascomycetous yeasts from analysis of nuclear large subunit (26S) ribosomal DNA partial sequences. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1998;73:331–371. doi: 10.1023/a:1001761008817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kurtzman C P, Robnett C J. Identification of clinically important Ascomycetous yeasts based on nucleotide divergence in the 5′ end of the large-subunit (26S) ribosomal DNA gene. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1216–1223. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.5.1216-1223.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lodder J, editor. The yeasts: a taxonomic study. 2nd ed. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: North-Holland publishing company; 1970. pp. 917–1079. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lott T J, Burns B M, Zancope-Oliveira R, Elie C M, Reiss E. Sequence analysis of the internal transcribed spacer 2 (ITS2) from yeast species within the genus Candida. Curr Microbiol. 1998;36:63–69. doi: 10.1007/s002849900280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lott T J, Kuykendall R J, Reiss E. Nucleotide sequence analysis of the 5.8S rDNA and adjacent ITS2 region of Candida albicans and related species. Yeast. 1993;9:1199–1206. doi: 10.1002/yea.320091106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Makimura K, Murayama S Y, Yamaguchi H. Detection of a wide range of medically important fungi by the polymerase chain reaction. J Med Microbiol. 1994;40:358–364. doi: 10.1099/00222615-40-5-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morrison D A. Phylogenetic tree-building. Int J Parasitol. 1996;26:589–617. doi: 10.1016/0020-7519(96)00044-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oda Y, Yabuki M, Tonomura K, Fukunaga M. A phylogenetic analysis of Saccharomyces species by the sequence of 18S-28S rRNA spacer regions. Yeast. 1997;13:1243–1250. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199710)13:13<1243::AID-YEA173>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Odds F C, Van Nuffel L, Dams G. Prevalence of Candida dubliniensis isolates in a yeast stock collection. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2869–2873. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.10.2869-2873.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pfaller M, Wenzel R. Impact of the changing epidemiology of fungal infections in the 1990s. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1992;11:287–291. doi: 10.1007/BF01962067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pfaller M A, Messer S A, Houston A, Rangel-Frausto M S, Wiblin T, Blumberg H M, Edwards J E, Jarvis W, Martin M A, Neu H C, Saiman L, Patterson J E, Dibb J C, Roldan C M, Rinaldi M G, Wenzel R P. National epidemiology of mycoses survey: a multicenter study of strain variation and antifungal susceptibility among isolates of Candida species. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1998;31:289–296. doi: 10.1016/s0732-8893(97)00245-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Price C W, Fuson G B, Phaff H J. Genome comparison in yeast systematics: delimitation of species within the genera Schwanniomyces, Saccharomyces, Debaryomyces, and Pichia. Microbiol Rev. 1978;42:161–193. doi: 10.1128/mr.42.1.161-193.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramani R, Gromadzki S, Pincus D H, Salkin I F, Chaturvedi V. Efficacy of API 20C and ID 32C systems for identification of common and rare clinical yeast isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:3396–3398. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.11.3396-3398.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reiss E, Tanaka K, Bruker G, Chazalet V, Coleman D, Debeaupuis J P, Hanazawa R, Latge J P, Lortholary J, Makimura K, Morrison C J, Murayama S Y, Naoe S, Paris S, Sarfati J, Shibuya K, Sullivan D, Uchida K, Yamaguchi H. Molecular diagnosis and epidemiology of fungal infections. Med Mycol. 1998;36(Suppl. 1):249–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sugita T, Nishikawa A, Ikeda R, Shinoda T. Identification of medically relevant Trichosporon species based on sequences of internal transcribed spacer regions and construction of a database for Trichosporon identification. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1985–1993. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.6.1985-1993.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sullivan D, Coleman D. Candida dubliniensis: characteristics and identification. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:329–334. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.2.329-334.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thompson J D, Gibson T J, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins D G. The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4876–4882. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Turenne C Y, Sanche S E, Hoban D J, Karlowsky J A, Kabani A M. Rapid identification of fungi by using the ITS2 genetic region and an automated fluorescent capillary electrophoresis system. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1846–1851. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.6.1846-1851.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Warren N G, Hazen K C. Candida, Cryptococcus, and other yeasts of medical importance. In: Murray P R, Baron E J, Pfaller M A, Tenover F C, Yolken R H, editors. Manual of clinical microbiology. 7th ed. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1999. pp. 1191–1197. [Google Scholar]

- 31.White T J, Bruns T, Lee S, Taylor J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In: Innis M A, Gefland D H, Sninsky J J, White T J, editors. PCR protocols: a guide to methods and applications. New York, N.Y: Academic Press, Inc.; 1990. pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wright W L, Wenzel R P. Nosocomial Candida. Epidemiology, transmission, and prevention. Infect Dis Clin N Am. 1997;11:411–425. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5520(05)70363-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]