Abstract

Background

Inadvertent perioperative hypothermia is a phenomenon that can occur as a result of the suppression of the central mechanisms of temperature regulation due to anaesthesia, and of prolonged exposure of large surfaces of skin to cold temperatures in operating rooms. Inadvertent perioperative hypothermia has been associated with clinical complications such as surgical site infection and wound‐healing delay, increased bleeding or cardiovascular events. One of the most frequently used techniques to prevent inadvertent perioperative hypothermia is active body surface warming systems (ABSW), which generate heat mechanically (heating of air, water or gels) that is transferred to the patient via skin contact.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of pre‐ or intraoperative active body surface warming systems (ABSW), or both, to prevent perioperative complications from unintended hypothermia during surgery in adults.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; Issue 9, 2015); MEDLINE (PubMed) (1964 to October 2015), EMBASE (Ovid) (1980 to October 2015), and CINAHL (Ovid) (1982 to October 2015).

Selection criteria

We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that compared an ABSW system aimed at maintaining normothermia perioperatively against a control or against any other ABSW system. Eligible studies also had to include relevant clinical outcomes other than measuring temperature alone.

Data collection and analysis

Several authors, by pairs, screened references and determined eligibility, extracted data, and assessed risks of bias. We resolved disagreements by discussion and consensus, with the collaboration of a third author.

Main results

We included 67 trials with 5438 participants that comprised 79 comparisons. Forty‐five RCTs compared ABSW versus control, whereas 18 compared two different types of ABSW, and 10 compared two different techniques to administer the same type of ABSW. Forced‐air warming (FAW) was by far the most studied intervention.

Trials varied widely regarding whether the interventions were applied alone or in combination with other active (based on a different mechanism of heat transfer) and/or passive methods of maintaining normothermia. The type of participants and surgical interventions, as well as anaesthesia management, co‐interventions and the timing of outcome measurement, also varied widely. The risk of bias of included studies was largely unclear due to limitations in the reports. Most studies were open‐label, due to the nature of the intervention and the fact that temperature was usually the principal outcome. Nevertheless, given that outcome measurement could have been conducted in a blinded manner, we rated the risk of detection and performance bias as high.

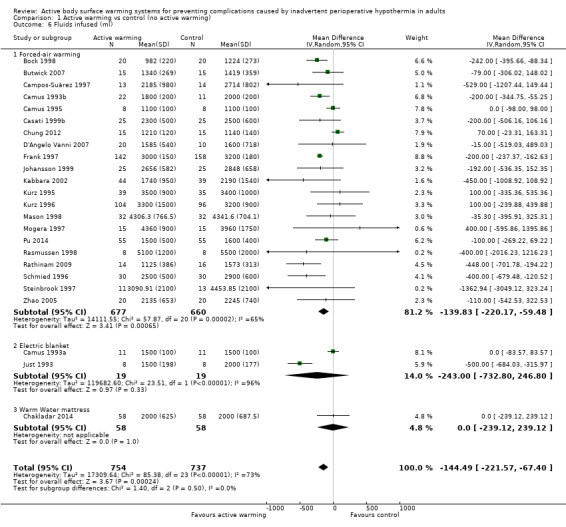

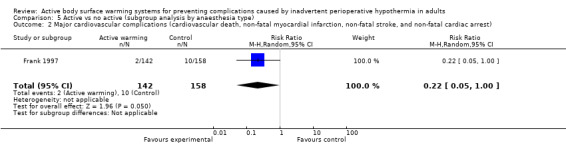

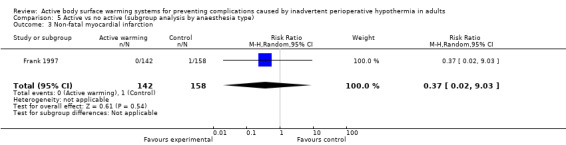

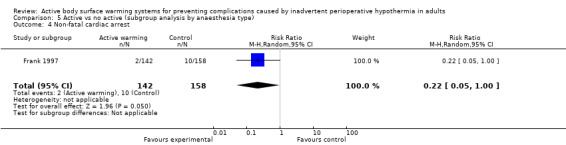

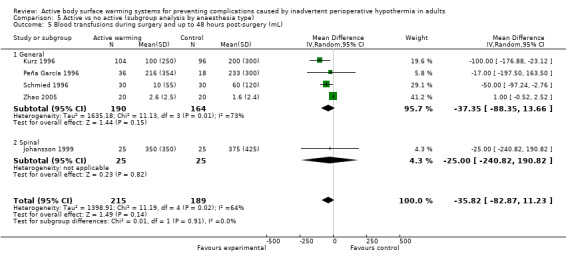

The comparison of ABSW versus control showed a reduction in the rate of surgical site infection (risk ratio (RR) 0.36, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.20 to 0.66; 3 RCTs, 589 participants, low‐quality evidence). Only one study at low risk of bias observed a beneficial effect with forced‐air warming on major cardiovascular complications (RR 0.22, 95% CI 0.05 to 1.00; 1 RCT with 12 events, 300 participants, low‐quality evidence) in people at high cardiovascular risk. We found no beneficial effect for mortality. ABSW also reduced blood loss during surgery but the magnitude of this effect seems to be irrelevant (MD ‐46.17 mL, 95% CI ‐82.74 to ‐9.59; I² = 78%; 20 studies, 1372 participants). The same conclusion applies to total fluids infused during surgery (MD ‐144.49 mL, 95% CI ‐221.57 to ‐67.40; I² = 73%; 24 studies, 1491 participants). These effects did not translate into a significant reduction in the number of participants being transfused or the average amount of blood transfused. ABSW was associated with a reduction in shivering (RR 0.39, 95% CI 0.28 to 0.54; 29 studies, 1922 participants) and in thermal comfort (standardized mean difference (SMD) 0.76, 95% CI 0.29 to 1.24; I² = 77%, 4 trials, 364 participants).

For the comparison between different types of ABSW system or modes of administration of a particular type of ABSW, we found no evidence for the superiority of any system in terms of clinical outcomes, except for extending systemic warming to the preoperative period in participants undergoing major abdominal surgery (one study at low risk of bias).

There were limited data on adverse effects (the most relevant being thermal burns). While some trials included a narrative report mentioning that no adverse effects were observed, the majority made no reference to it. Nothing so far suggests that ABSW involves a significant risk to patients.

Authors' conclusions

Forced‐air warming seems to have a beneficial effect in terms of a lower rate of surgical site infection and complications, at least in those undergoing abdominal surgery, compared to not applying any active warming system. It also has a beneficial effect on major cardiovascular complications in people with substantial cardiovascular disease, although the evidence is limited to one study. It also improves patient's comfort, although we found high heterogeneity among trials. While the effect on blood loss is statistically significant, this difference does not translate to a significant reduction in transfusions. Again, we noted high heterogeneity among trials for this outcome. The clinical relevance of blood loss reduction is therefore questionable. The evidence for other types of ABSW is scant, although there is some evidence of a beneficial effect in the same direction on chills/shivering with electric or resistive‐based heating systems. Some evidence suggests that extending systemic warming to the preoperative period could be more beneficial than limiting it only to during surgery. Nothing suggests that ABSW systems pose a significant risk to patients.

The difficulty in observing a clinically‐relevant beneficial effect with ABSW in outcomes other than temperature may be explained by the fact that many studies applied concomitant procedures that are routinely in place as co‐interventions to prevent hypothermia, whether passive or active warming systems based in other physiological mechanisms (e.g. irrigation fluid or gas warming), as well as a stricter control of temperature in the context of the study compared with usual practice. These may have had a beneficial effect on the participants in the control group, leading to an underestimation of the net benefit of ABSW.

Plain language summary

Body warming of people undergoing surgery to avoid complications and increase comfort after surgery

Review question

We reviewed the effects of warming the body by transferring heat through the skin surface to prevent complications caused by unintended low body temperature (hypothermia) in adults undergoing surgery.

Background

Sedatives and anaesthesia interfere with temperature regulatory responses and so can cause unplanned hypothermia during surgery and immediately after surgery. Long periods of exposure of large surfaces of skin to cold temperatures in operating rooms can also contribute to this effect. Hypothermia can make the recovery process more uncomfortable for the patients, as they often wake with chills and shivering, an involuntary response to cold to increase the production of body heat. Hypothermia may also be related to undesirable events such as infections and complications of the wound, complications of the heart and circulation, increased bleeding and a greater need for blood transfusions.

To avoid this unintended hypothermia, several different types of active warming systems are used to transfer heat to the body of the patient through the skin, either immediately before or during surgery, or both.

Study characteristics

The review includes 67 randomized controlled trials (5438 people). The trials included patients of all ages and both genders undergoing all types of surgery. The evidence was from studies available to October 2015. Forty‐five trials compared a warming system to a control intervention, 18 compared different types of warming systems, and 10 compared different modalities of the same warming system. Forced‐air warming was the most studied system.

Key results

Active warming had some beneficial clinical effects on the patient. It reduced the risk of a major complication of heart and circulation in one trial in people with substantial disease of that system, but the evidence remains inconclusive. Active warming reduced the rate of infection and complications of surgical wounds.. This effect was shown in two quite large trials in people undergoing abdominal surgery; forced‐air warming was applied exclusively before the operation in one study, while in the other it was applied during the operation. Patients receiving active warming systems had about one‐third the risk of postsurgical chills or shivering compared to those receiving control treatment (29 trials, 1922 people). Thermal comfort was increased for the patient compared with the control intervention (10 trials involving 700 people). On the other hand, warming made little or no difference to the risk of death, blood loss or the need for a blood transfusion. We found no differences in the number of non‐fatal heart attacks, in anxiety or in pain, compared with people in the control groups.

The trials in the review did not allow us to identify which warming system was better. However, there was an indication from one trial at low risk of bias that results were better when systemic warming was extended to the period before the operation in people undergoing major abdominal surgery. We could only get limited information from the study reports regarding adverse effects. In some cases the trials reported that there had been no adverse effects.

Quality of the evidence

The quality of the evidence was low for surgical site infections and complications of the heart and circulation. This is because very few trials with few events reported on these outcomes, although they were at low risk of bias. Patients differed in the types of surgery, with different complexities and duration, the type of anaesthesia, patient age, the severity of the condition and other illnesses. The trials did not last long, which made it difficult to detect clinical effects. These outcomes are also strongly influenced by other management components during the operation that we did not evaluate in this review. While some studies applied a single intervention, others used two or more interventions in combination, and/or included other methods of passive warming. The control group did not always consist of a 'pure control' without active heating, and sometimes patients also received another intervention as part of usual care. All these reasons may explain the diversity that we observed for some outcomes among the studies. The temperature of the control group may also have been more strictly controlled, as there is now widespread awareness of the risk of hypothermia.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Active body surface warming systems compared to control for preventing inadvertent perioperative hypothermia in adults.

| Active body surface warming systems compared to control for preventing inadvertent perioperative hypothermia in adults | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults undergoing surgery Settings: Inpatients Intervention: Active body surface warming systems (ABSW) Comparison: Control (no active warming) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Active warming systems | |||||

| Infection and complications of the surgical wound | 157 per 1000 | 57 per 1000 (31 to 104) | RR 0.36 (0.20 to 0.66) | 589 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | |

| Major cardiovascular complications (cardiovascular death, non‐fatal myocardial infarction, non‐fatal stroke, and non‐fatal cardiac arrest) | 63 per 1000 | 14 per 1000 (3 to 63) | RR 0.22 (0.05 to 1) | 300 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | |

| All‐cause mortality | 16 per 1000 | 16 per 1000 (4 to 63) | RR 1.01 (0.26 to 4) | 500 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | |

| Participants transfused | 291 per 1000 | 259 per 1000 (163 to 413) | RR 0.79 (0.50 to 1.23) | 621 (8 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ moderate2 | |

| Chills/shivering | 212 per 1000 | 83 per 1000 (59 to 115) |

RR 0,39 (0,28 to 0,54) |

1922 (29 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ high3 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1The number of events is low. 2Although some of the included studies had a high risk of bias (Johansson 1999 had a high risk of detection bias due to inadequate blinding of the participants and physicians, and Kabbara 2002 had a high risk of selection bias), we estimate that it is unlikely that further studies show a beneficial effect on this outcome although the precise effect estimate may change to some extent depending on clinical circumstances. 3Although four out of 29 of the included studies (Camus 1993b; Fallis 2006; Ng 2003; Wongprasartsuk 1998) had a high risk of bias, our overall confidence in the effect estimate remains high. A sensitivity analysis excluding those trials (data not shown) did not change the estimate and the sample size remains above 250 events.

Background

Description of the condition

Regulation of temperature

In healthy individuals, the mean body temperature varies between 36.1ºC and 37.4ºC. Maintaining body temperature means maintaining a balance between production and loss of heat. Heat is generated continuously as a product of the body’s metabolism. Regulation of temperature is done through a feedback mechanism in the central nervous system. The hypothalamus acts as a 'biological thermostat', noting temperature changes and initiating thermal regulation aimed at increasing or decreasing overall body temperature.

During rest (anaesthesia would be an extreme case of rest), the greatest amount of heat comes from the metabolic activity of the brain and the other major organs. All heat generated by metabolism is dissipated to the environment (mainly through the skin) in order to maintain a stable thermal condition.

The effects of anaesthesia on thermal regulation

In clinical doses, both sedatives and anaesthesia inhibit thermal regulatory responses (primarily vasoconstriction). The physiological thermal regulating mechanisms are not shut off but the thermal thresholds through which the usual responses start are altered. In this way, general anaesthesia produces vasodilatation by depressing vasoconstrictor responses. Since the thermal regulation mechanisms are inhibited, the central compartment goes through a progressive loss of heat, which is transmitted to the peripheral compartment. The speed of this transfer as well as the amount of heat lost depends on the difference in temperature between the two compartments. Vasodilatation in the peripheral compartment brings about the loss of heat to the environment, which as a consequence helps to cool down the central compartment. This process of caloric transfer is known as redistribution.

The combination of reduced heat production and surgical, anaesthetic and environmental factors that increase heat loss can cause hypothermia in the patient. Intraoperative hypothermia is defined as a central body temperature below 36ºC.

At the beginning of general anaesthesia, the overall body temperature does not change, since the temperature loss in the central compartment is picked up by the peripheral compartment. By the second hour of anaesthesia the heat loss in the central compartment is slower, and in this phase the loss of body heat to the environment is more important. Overall temperature decreases when more heat is lost than is generated. The people who are most susceptible to heat loss are the elderly, patients at higher anaesthetic risk (American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) grade 3 to 4), cachectics, burn victims, people with hypothyroidism, and those affected by corticoadrenal insufficiency.

Perioperative hypothermia complications

Hypothermia may increase morbidity as a result of altering various systems and functions within the organism.

Cardiac complications are the principal cause of morbidity during the postoperative phase. Prolonged ischaemia is usually associated with cellular damage, and for this reason it is important to prevent factors that can lead to this complication, such as decreased body temperature. Hypothermia stimulates and amplifies adrenergic responses with the release of noradrenaline, which results in peripheral vasoconstriction and hypertension (Sessler 1991; Sessler 2001) and increases the chances of myocardial ischaemia.

Some studies have shown that intraoperative hypothermia, accompanied by vasoconstriction, constitutes an independent factor that slows wound healing and increases the incidence of surgical site infection (Kurz 1996; Melling 2001).

Even moderate hypothermia (35ºC) can alter physiologic coagulation mechanisms by affecting platelet function and modifying enzymatic reactions. Decreased platelet activity produces an increase in bleeding and greater need for transfusion (Rajagopalan 2008). Moderate hypothermia can also reduce the metabolic rate, manifesting as a prolonged effect of certain drugs used during anaesthesia and some uncertainty about their effects. This is particularly significant in elderly people (Heier 1991; Heier 2006; Leslie 1995).

Patients often comment on shivering upon awakening from anaesthesia, identifying this as one of the most uncomfortable immediate postoperative experiences. Shivering is a response to cold and is the result of involuntary muscular activity, the purpose of which is to increase metabolic heat (Sessler 2001).

Due to the above reasons, inadvertent non‐therapeutic hypothermia is considered an adverse effect of general and regional anaesthesia (Bush 1995; Putzu 2007; Sessler 1991). The monitoring of body temperature is essential for maintaining normothermia during surgery and for timely detection of the appearance of unintended hypothermia. As a result, the monitoring of body temperature is included as one of the items in the surgical safety checklist of the World Health Organization guidelines (WHO 2015). This checklist is intended to reduce the rate of major surgical complications.

Description of the intervention

The goal of preserving a patient's body temperature during anaesthesia and surgery is to minimize heat loss by reducing radiation and convection from the skin, evaporation from exposed surgical areas, and cooling caused by the introduction of cold intravenous fluids. Interventions used to maintain body temperature can be classified as follows:

i) Interventions that decrease loss of heat through redistribution (i.e. preoperative pharmacologic vasodilatation and prewarming the skin prior to anaesthesia).

ii) Passive warming systems aimed at reducing heat loss and thus preventing hypothermia, including interventions at above environmental temperatures; passive isolation by covering the exposed body surface; and a closed or semi‐closed anaesthesia circuit with low flows.

iii) Active warming systems aimed at transferring heat to the patient. The effectiveness of these systems depends on various factors such as the design of the device, the type of heat transfer, placement of the system over the patient and, most importantly, the total body area covered in the heat exchange. The following systems are used for active warming: infrared lights, electric blankets, mattresses or blankets with warm‐water circulation, forced‐air warming or convective air‐warming transfer, warming of intravenous and irrigation fluids, warming and humidifying of anaesthetic air, and carbon dioxide (CO₂) warming in laparoscopic surgery.

How the intervention might work

For the purposes of this review, we have focused only on those active warming systems that transfer heat through the skin (active body surface warming systems (ABSW)) using a mechanical system. We expect that keeping body temperature from falling under certain levels should prevent perioperative vasoconstriction, leading to less catecholamine release, and hypertension.

Maintaining temperature through a mechanical heat transference (air‐based or water‐based) system should prevent perioperative complications more efficiently that just passively preventing a person's loss of heat, as happens with thermal isolation. Adequately‐warmed people should also maintain their platelet activity, preventing them from excessive bleeding and the need for transfusions.

Why it is important to do this review

The clinical effectiveness of the different types of warming devices that can be used has been assessed in a very extensive guideline commissioned by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence in the UK (NICE 2008). The report concludes that there is sufficient evidence of clinical effectiveness and cost effectiveness for recommendations to be made on the use of forced‐air warming (the most widely investigated ABSW) to prevent and treat perioperative hypothermia. Nevertheless, most of the data come from intermediate outcomes such as temperature. The report's search is only current until the year 2007, when much research, especially with new systems, has been published since that date. Given this, our review evaluates the efficacy and safety of these ABSW systems focusing exclusively on relevant clinical outcomes other than temperature.

Other Cochrane reviews have provided evidence for the efficacy and safety of passive methods such as thermal insulation (Alderson 2014) and non‐cutaneous active systems, such as warmed gases or intravenous fluids (Birch 2011; Campbell 2015). Other reviews have also addressed pharmacological interventions to prevent specific complications derived from hypothermia, such as shivering (Lewis 2015).

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of pre‐ or intraoperative active body surface warming systems (ABSW), or both, to prevent perioperative complications from unintended hypothermia during surgery in adults.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We include only randomized controlled trials (RCTs) assessing the efficacy and safety of pre‐ and/or intraoperative active body surface warming systems to prevent complications due to heat loss and hypothermia during surgery.

We have excluded RCTs where the aim was to treat rather than prevent unintended hypothermia. This topic is covered in a separate review (Warttig 2014). We have also excluded trials of rewarming in induced hypothermia.

We have included RCTs where the intervention was applied preoperatively, intraoperatively, or preoperatively and intraoperatively. We exclude RCTs where the intervention was applied exclusively in the postoperative phase, as this usually corresponds to surgery with intentional hypothermia.

We define the:

Preoperative phase, as the hour before induction of anaesthesia (when the patient is prepared for surgery on the ward or in the emergency department)

Intraoperative phase, as total anaesthesia time

We have excluded RCTs comparing an ABSW system to another active warming system not covered in this review (i.e. warming of intravenous or irrigation fluids, etc.) except when the latter intervention was applied as a co‐intervention simultaneously in both study groups; in this case, we classified the trial as a comparison between ABSW versus control.

Types of participants

We only included adults undergoing a scheduled surgery (including ambulatory surgery), except surgery using intended hypothermia (such as off‐pump surgery and certain neurosurgical interventions).

Types of interventions

The protocol for the review (Urrútia 2011) originally intended to cover all active warming systems to prevent unintended hypothermia. Subsequently, we limited the focus of the review to ABSW systems, and have amended the review accordingly (See Differences between protocol and review).

For the purposes of this review, we include the following ABSW systems: electric blankets, electric heated mattresses and pads, warm‐water circulation systems (mattresses, blankets or garments), other conductive warming systems (such as resistive conductive polymer blankets and mattresses) and forced‐air warming systems. All these systems have in common that the transfer of heat to the recipient is achieved by skin contact.

We have not considered other active warming systems based on distinct mechanisms (such as fluid warming, infrared lights, anaesthetic air warming and warm CO₂ in laparoscopic surgery) in this review, as they are covered in separate reviews (Birch 2011; Campbell 2015).

The comparisons of interest in this review are:

ABSW versus control (generally involving a passive warming system, warmed cotton blankets or thermal insulation) (ABSW versus CTRL)

ABSW versus any other ABSW (alone or in combination with other active warming systems) (ABSW1 versus ABSW2)

Different modalities of an intervention with a particular ABSW (ABSWa versus ABSWb)

To define the comparisons of interest, we have not taken into account the co‐interventions (which could consist of passive or other types of active warming systems) that were applied to all participants (both study groups). Rather, we have considered only those interventions that were randomly assigned to each study group.

Types of outcome measures

Eligible studies had to include relevant clinical outcomes other than measuring temperature or other physiologic parameters alone.

Primary outcomes

Surgical site infection and complications (wound healing and dehiscence)

Major cardiovascular complications (cardiovascular death, non‐fatal myocardial infarction, non‐fatal stroke and non‐fatal cardiac arrest)

All‐cause mortality

Secondary outcomes

Transfusions (number of participants transfused; blood product usage)

Blood loss

Intraoperative intravenous (IV) fluids infused

Other cardiovascular complications (bradycardia, hypotension, arrhythmias)

Participant‐reported outcomes (anxiety, thermal comfort, thermal sensation, pain)

Shivering (number of participants)

Pressure sores and ulcers

Adverse effects (including thermal burns)

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following electronic databases: Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (the Cochrane Library, Issue 9, 2015); MEDLINE (PubMed) (1964 to October 2015), EMBASE (Ovid) (1980 to October 2015), CINAHL (Ovid) (1982 to October 2015). All the searches were designed and executed by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator of the Cochrane Anaesthesia Review Group (CARG) in three consecutive phases (up to August 2009, up to April 2011 and up to October 2013) and thereafter by the information specialist at the Iberoamerican Cochrane Center (up to October 2015). Our search strategies can be found in the Appendices (CENTRAL Appendix 1; MEDLINE Appendix 2; EMBASE Appendix 3; CINAHL Appendix 4).

Our search strategy used free text and controlled language (MeSH terms) for those terms and descriptors concerning interventions (warming systems) and indications (surgery, hypothermia), and methodologic filters for an exhaustive identification of the selected studies (clinical trials). We did not apply restrictions regarding publication status or by sample size.

To screen the results of this search, we did not use a specific software to manage the references, but did this manually (using Word files), except for the last update where we used Endnote.

Searching other resources

In addition:

We performed a search for other reviews and health technology assessment reports about this topic, and a manual review of all the bibliographic references in all these reviews and reports;

We screened all the reference lists of the RCTs identified during the review process.

We did not apply any language restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Several authors (GU, HP, EM) and collaborators (SC, BN and EP) in pairs, independently reviewed the results of the bibliographic searches to select the articles to be included in the review. We only included those studies that fulfilled all the eligibility criteria of the review.

The pairs of authors initially reviewed titles and abstracts and obtained the full text if more detailed information was required to determine if the trial met the inclusion criteria. Each of these authors documented the reasons for trial exclusion when appropriate (see Appendix 5 for a copy of the Study Selection Form). We resolved disagreements by discussion and consensus between authors, with the collaboration of a third author among the specialists (JC, PP and LM).

Where there was insufficient published information in order to make a decision about inclusion, GU contacted the first author of the relevant trial.

Data extraction and management

Several authors, in pairs (MR, GU, EM, HP, PA) extracted data independently from the selected trials using a standardized data extraction form. A copy of this form is in Appendix 6. We resolved disagreements by discussion and consensus between authors, with the collaboration of a third author from among the specialists (JC, PP and LM).

These authors entered the retrieved data from manuscripts into Review Manager 5 (Revman 2014). Where necessary, we contacted the authors of the original publications to obtain additional data about the design of the study and results.

We extracted the following data from each study:

General information, such as title, first author, contact address, publication source, publication year, country.

Methodological characteristics and study design.

Clinical and demographic characteristics of study participants.

Description of the intervention and the control. We collected information about the type of surgery, duration, surgical team experience, and prophylactic antibiotic administration, when available.

Outcomes measures as noted above.

Results for each study group.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two pairs of authors (MR, GU, EM, HP) independently assessed risks of bias for each study, using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We resolved disagreements by discussion or by involving a third assessor among the specialists (JC, PP, and LM).

We considered a trial as having a low risk of bias if we assessed all of the following criteria as adequate, and as having a high risk of bias if we assessed one or more of the following criteria as inadequate:

Sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias). We have described for each included study the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups. We have assessed the methods as: adequate (any truly random process, e.g. random‐number table, computer random‐number generator); inadequate (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth, hospital or clinic record number); or unclear.

Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias). We have described for each included study the method used to conceal the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to determine whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of or during recruitment, or changed after assignment. We have assessed the methods as: adequate (e.g. telephone or central randomization, consecutively‐numbered sealed opaque envelopes); inadequate (open random allocation, unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation, date of birth); unclear.

Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias). We have described for each included study all the methods used, if any, to blind participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We have also provided information on whether the intended blinding was effective. Where blinding was not possible, we have appraised whether the lack of blinding was likely to have introduced bias.

Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias). We have described for each included study all the methods used, if any, to blind outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We have also provided information on whether the intended blinding was effective. Where blinding was not possible, we have assessed whether the lack of blinding was likely to have introduced bias.

Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias through withdrawals, dropouts, protocol deviations). We have described for each included study and for each outcome the completeness of data, including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We have stated whether attrition and exclusions were reported, the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomized participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information was reported or could be supplied by the trial authors, we have re‐included missing data in the analyses. We have considered intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis as adequate if all dropouts or withdrawals were accounted for, and as inadequate if the number of dropouts or withdrawals was not stated, or if the reason for any dropouts or withdrawals was not stated.

Selective reporting. We have reported for each included study which outcomes of interest declared in the Methods section were later unreported in the Results section. When we did not have access to the protocol or the register of the trial, selective reporting was labelled as "unclear". .

Other sources of bias. We have described for each included study any important concerns we have about other possible sources of bias. We have assessed whether each study was free of other problems that could put it at risk of bias as: low risk, high risk or unclear.

With reference to (1) to (7) above, we have assessed the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we consider it likely to have impacted on the findings.

We have also assessed the quality of the evidence, per outcome and overall, using the GRADE system (Guyatt 2008). We include a 'Summary of findings' table (SoF), with some of the most relevant outcomes. This table does not include adverse effects (safety), due to the absence of data in the studies.

Measures of treatment effect

We have analysed the results of the trials using Review Manager 5, following the recommendations given by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

We have measured treatment effect by risk ratios for dichotomous variables, and by mean differences or standardised mean differences for continuous variables. We used 95% confidence intervals (CIs) to indicate the precision of the estimates.

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis was always the participant, as all RCTs included in the review had a parallel design.

Dealing with missing data

Given the low proportion of missing data and their even distribution across groups, we conducted all analysis with the available data in the trials, without imputations for missing values.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Before obtaining pooled estimates of global and specific effects for each type of intervention, we have carried out a statistical heterogeneity analysis assessing the value of the I² statistic, thereby estimating the percentage of total variance across studies that is due to heterogeneity rather than to chance (Higgins 2002). We have considered a value greater than 30% as indicating statistically significant heterogeneity. When heterogeneity was present, we attempted to explore it by considering the clinical features and design of the trials.

Assessment of reporting biases

Due to the sparse number of studies assessing the same outcomes, we did not use statistical techniques to assess publication bias. For selective reporting bias, we recorded the number of studies that reported results of each outcome specified by the authors in the Methods section of the study report.

Data synthesis

We have estimated the effect of the ABSW systems through meta‐analyses, using the random‐effects model applied to the intervention effect indicators (risk ratio and mean difference), using Review Manager 5 software. We conducted all main analyses on an 'available case' basis, analysing data as presented in the individual reports.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We conducted subgroup analyses for the comparison ABSW versus control for all outcomes. We applied a test for subgroup differences based on the I² value. We have analysed the following subgroups:

Type of anaesthesia (general or combined anaesthesia versus exclusively regional anaesthesia).

Timing of application of the intervention (preoperatively, intraoperatively, or both preoperatively and intraoperatively).

We did not run the other planned subgroup analyses, based on type of surgery and use of premedications.

Sensitivity analysis

We had planned several sensitivity analyses to investigate potential sources of heterogeneity:

According to the risk of bias (including only trials at low risk of bias).

According to the statistical model, using a fixed‐effect model.

Including only studies where duration of surgery was longer than 120 minutes, as a surrogate for higher surgery risk.

According to imputation method to derive an intention‐to‐treat analysis, using a 'best case/worst case' imputation of missing data. Given the low proportion of missing data and their distribution, we changed the main analyses to a per protocol analysis, which rendered the sensitivity analyses by method of imputation irrelevant.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

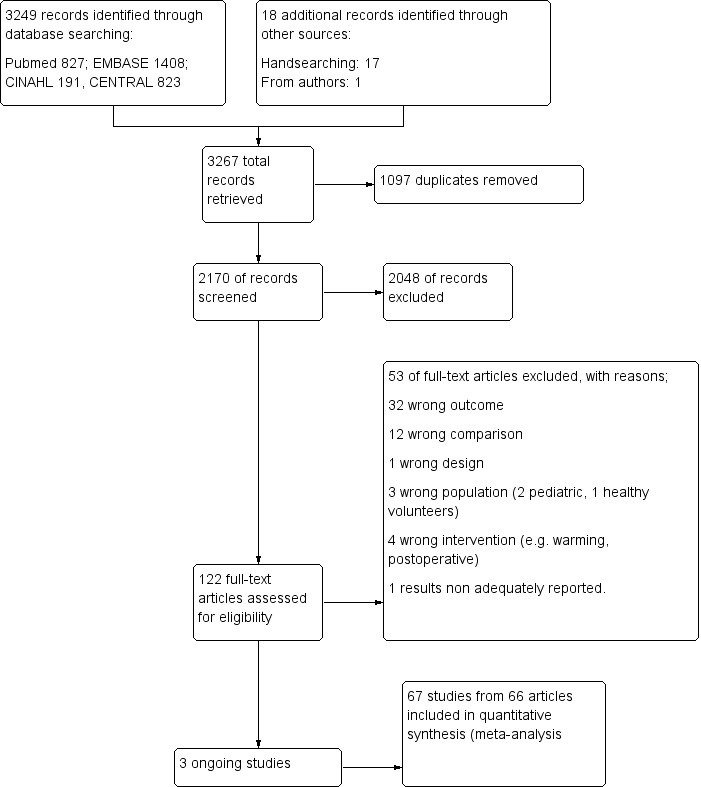

The searches retrieved 2170 unique references (records) that were carefully screened. We used the most comprehensive guideline available on this topic (NICE 2008) as an aid not only in the identification of studies but to decide on their eligibility. We required the full text for all potentially relevant studies published after the date of search of the guideline, and for others where some doubts persisted. We assessed 111 full‐text articles for eligibility, and selected 66 articles covering 67 RCTs (one paper reported two different RTCs conducted simultaneously by the same team) for inclusion (see Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

We included 67 RCTs (one article includes two RCTs: Camus 1993a; Camus 1993b) with 5438 participants, comprising 79 comparisons of interest:

Forty‐five RCTs (47 comparisons after merging 11 interventions arms into five, and four control arms into two) correspond to comparison type 1 (ABSW versus control) (Bennett 1994; Benson 2012; Bock 1998; Butwick 2007; Campos‐Suárez 1997; Camus 1993a; Camus 1993b; Camus 1995; Camus 1997; Casati 1999b; Chakladar 2014; Chung 2012; D'Angelo Vanni 2007; Fallis 2006; Fossum 2001; Frank 1997; Horn 2002; Horn 2012; Johansson 1999; Just 1993; Kabbara 2002; Kiessling 2006; Krenzinschek 1995; Kurz 1995; Kurz 1996; Leeth 2010; Lindwall 1998; Mason 1998; Melling 2001; Mogera 1997; Ng 2003; O'Brien 2010; Paris 2014; Peña García 1996; Persson 2001; Pu 2014; Rasmussen 1998; Rathinam 2009; Schmied 1996; Scott 2001; Steinbrook 1997; Wongprasartsuk 1998; Yamakage 1995; Yildirim 2012; Zhao 2005). Two studies comprised 3 branches, providing 2 comparisons type 1 (ABSW vs control) in a single trial (Melling 2001; Rasmussen 1998). The most studied warming system was by large forced‐air warming (FAW) in 38 RCTs, followed by electric blankets in three. The rest (one study each) were: resistive warming mattress, water garment, warmed foam pad, warming pad, heated circulating water system, and radiant heating. For the intervention used as a control, there was wide variability among studies, with some RCTs where participants did not receive any kind of active warming ('pure controls'), and many others where they could receive either warmed cotton blankets, thermal insulation, and/or warming of intravenous and irrigation fluids and blood (which are active warming systems not covered by this review). Finally, in one study (Bock 1998), participants in the control group received an ABSW during the intraoperative period as a co‐intervention (an intervention that was used systematically in all study participants). A few studies used a sham ABSW procedure (Butwick 2007; Chung 2012; Kurz 1996), while all the rest were open‐label.

Eighteen RCTs (22 comparisons) corresponded to comparison type 2 (ABSW versus another type of ABSW) (Calcaterra 2009; Elmore 1998; Hasegawa 2012 (three comparisons); Hofer 2005 (three comparisons); Janicki 2001; Kim 2014; Lee 2004; Leung 2007; Matsukawa 1994; Melling 2001; Moysés 2014; Ng 2006; Pagnocca 2009; Suraseranivongse 2009; Tanaka 2013; Torrie 2005; Vassiliades 2003; Zangrillo 2006). As for the specific comparisons made in these studies, nine compared FAW versus a circulating water‐based system (mattress, wraps, garments and pads), four compared FAW versus radiant heating, three compared FAW versus resistive heating, two compared FAW versus electric heating pads, one compared FAW with thermally‐conductive foam pads. Two trials compared a circulating‐water‐based system versus carbon‐fibre resistive heating and one compared thermal blankets versus thermal mattress.

Ten RCTs (12 comparisons) corresponded to comparison type 3 (same ABSW: two different ways of administration) (Andrzejowski 2008; Camus 1993b; Casati 1999a; D'Angelo Vanni 2007; Horn 2012; Peña García 1996; Perl 2014; Winkler 2000; Wong 2007; Yamakage 1995).

Most of the included studies reported only one comparison (two‐arm RCTs), but 14 trials reported two or more comparisons in the same article (Bennett 1994; Camus 1993b; Chung 2012; D'Angelo Vanni 2007; Hasegawa 2012; Hofer 2005; Horn 2012; Melling 2001; Ng 2003; Paris 2014; Peña García 1996; Perl 2014; Rasmussen 1998; Yamakage 1995). Of these, we excluded five comparisons and merged others for practical reasons. One study (Negishi 2003), was included as a secondary reference of another trial (Hasegawa 2012), since it was a preliminary report of the completed trial. Therefore, its data were not included in the analysis, since it included the same participants.

The sample size in each study ranged from 14 (Yamakage 1995) to 416 (Melling 2001). Thirty‐three (49%) studies included 50 participants or fewer, 21 (31%) between 51 and 100, and 13 (20%) had more than 100. The average sample size was 81 participants per study. The mean age of the participants ranged from 30 (Fallis 2006) to 73 years (Torrie 2005).

By operating time

Seven studies exclusively considered the preoperative period (prewarming) when the intervention was applied and assessed (Camus 1995; Chung 2012; Fossum 2001; Horn 2012; Just 1993; Leeth 2010; Melling 2001), and nine reported having used warming systems during both pre‐ and intraoperative periods of surgery (Andrzejowski 2008; Benson 2012; Bock 1998; D'Angelo Vanni 2007; Horn 2002; Perl 2014; Rathinam 2009; Wong 2007; Wongprasartsuk 1998). The remaining 51 studies reported having used warming systems during the intraoperative period of surgery, starting after the induction of anaesthesia.

By anaesthesia type

In 41 trials the participants were operated on under general anaesthesia, under spinal/epidural anaesthesia in 16 trials, under regional anaesthesia in one, and in eight trials the participants received different types of anaesthesia (Frank 1997; Hasegawa 2012; Krenzinschek 1995; Lee 2004; Lindwall 1998; Scott 2001; Steinbrook 1997; Tanaka 2013). In one trial it was unclear what type of anaesthesia was administered (Melling 2001).

By duration of the surgical intervention

In 38 trials the surgery had a mean duration of 120 minutes or longer (Andrzejowski 2008; Bennett 1994; Bock 1998; Campos‐Suárez 1997; Camus 1993a; Camus 1993b; Camus 1995; Camus 1997; Elmore 1998; Frank 1997; Hasegawa 2012; Hofer 2005; Janicki 2001; Just 1993; Kabbara 2002; Kiessling 2006; Kim 2014; Kurz 1995; Kurz 1996; Lee 2004; Leung 2007; Lindwall 1998; Mason 1998; Matsukawa 1994; Mogera 1997; Moysés 2014; Pagnocca 2009; Peña García 1996; Pu 2014; Rasmussen 1998; Rathinam 2009; Suraseranivongse 2009; Tanaka 2013; Vassiliades 2003; Wong 2007; Wongprasartsuk 1998; Zangrillo 2006; Zhao 2005). In 23 RCTs, it was less than 120 minutes on average (Benson 2012;Casati 1999a; Casati 1999b; Chakladar 2014; Chung 2012;D'Angelo Vanni 2007; Fallis 2006; Fossum 2001; Horn 2002;Horn 2012; Johansson 1999; Melling 2001;Ng 2003; Ng 2006; O'Brien 2010; Paris 2014;Perl 2014; Persson 2001; Schmied 1996; Scott 2001; Torrie 2005;Winkler 2000; Yildirim 2012). In six studies, duration of surgery was not reported (Calcaterra 2009; Krenzinschek 1995; Leeth 2010; Steinbrook 1997; Yamakage 1995; Butwick 2007).

There was a wide range of types of surgeries across the studies, including open abdominal surgery in 23 studies, laparoscopic abdominal surgery in two, caesarean section in six, total hip arthroplasty in seven, other types of orthopaedic surgery in six, off‐pump coronary artery by‐pass in five, thoracic surgery in two, transurethral resection of the prostate in one, and neurosurgery in one. Thirteen studies reported a mixture of gynaecological, orthopaedic, laparoscopic, breast, head‐neck, plastic, vascular and/or general surgical procedures.

Regarding the American Society of Anaesthesiologists (ASA) physical status classification, 19 studies included participants with ASA I to II status, while 24 studies reported having included participants with ASA I to III status. Two studies included only ASA III status participants (Campos‐Suárez 1997; Hofer 2005) and four studies included participants with ASA I to IV status. Eighteen studies did not state the ASA status of the participants.

Concerning the geographical setting of the included studies, 30 were conducted in Europe, 18 in North America (USA and Canada), 13 in Asia, two in Australia, and three in South America (Brazil). The vast majority were single‐centre trials, and six were multicentre (only two were international).

Fourty‐for trials included all participants in the analyses, either because they had no missing data or because they conducted an ITT analysis. Of the 23 trials with missing data, the proportion of lost participants was higher than 10% in five (Elmore 1998; Frank 1997; Kiessling 2006; Leeth 2010; Scott 2001).

For further details see Characteristics of included studies.

Excluded studies

We excluded 53 studies, mainly because of the lack of data on the outcomes of interest for the review (most of them reported exclusively on temperature, which is the most studied outcome in this context), or because they addressed a comparison not covered by this review in 12 studies. We excluded other studies for a variety of reasons (pediatric population, healthy volunteers, wrong interventions such as rewarming, or wrong design). For further details see Characteristics of excluded studies.

Studies awaiting classification

Three studies are awaiting classification (Kaudasch 1996; Leben 1997; Xu 2004). For further details see Characteristics of studies awaiting classification.

Risk of bias in included studies

The main limitation of the majority of the studies is the small sample size, which limits the likelihood of detecting any difference in the clinical outcomes considered in this review, as almost all of the trials were designed with temperature as the principal outcome. Some of the outcomes considered in this review (blood loss, transfusion or intravenous fluid requirements) were recorded not as an outcome but as descriptive information in the baseline characteristics of the study population.

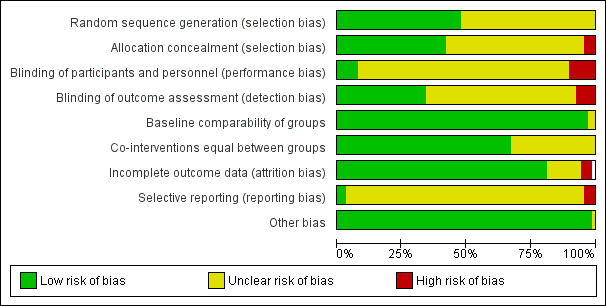

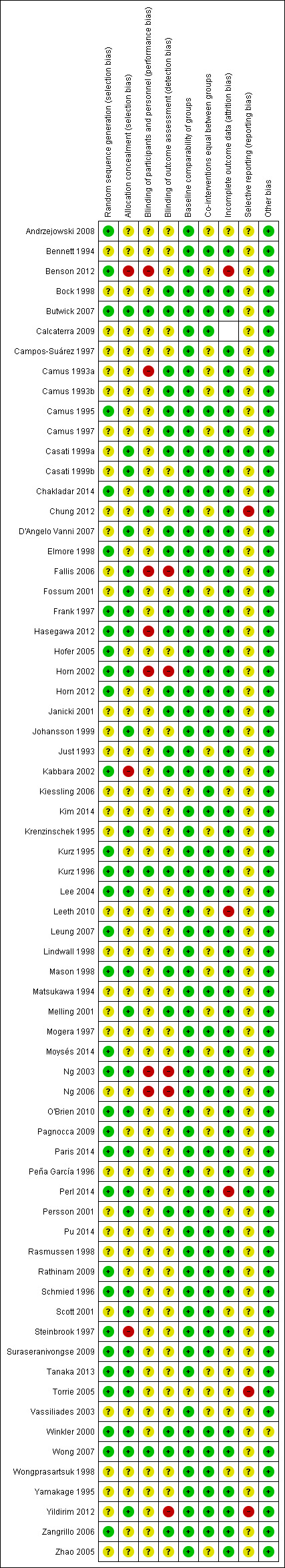

We summarize the risk of bias in the 'Risk of bias' graph (Figure 2) and the 'Risk of bias' summary (Figure 3). The reasons for classification of the risk of bias are provided in the tables Characteristics of included studies.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

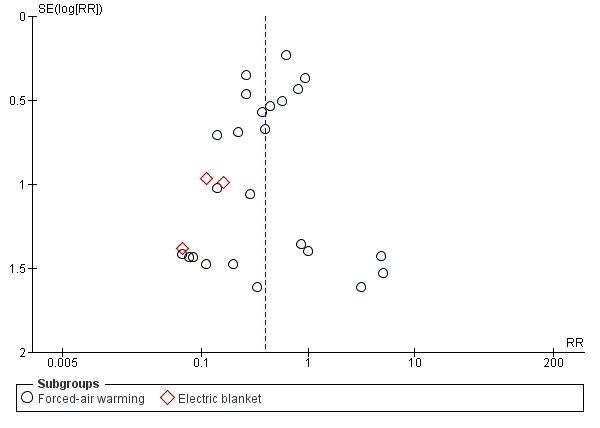

The included studies had a low risk of bias for baseline comparability (we found no obvious differences among study groups based on the information provided in the table of participants' characteristics), attrition bias (as expected, due to the study setting and the short duration of follow‐up, the number of losses and dropouts was irrelevant) and co‐interventions common to both groups (although this is very difficult to assess in detail, given the concurrence of numerous interventions, not necessarily reported, which could potentially affect the results). We rated the risk of bias as low to unclear for random sequence generation and for allocation concealment due to lack of details, selective reporting, and blinding of participants and personnel. We judged it as unclear to high for blinding of outcome assessment, as most of the studies had an open design (no measures were implemented to guarantee an objective assessment of outcomes) or it was not mentioned at all in the publications. Finally, for most of the comparisons there were not enough studies to assess publication bias. For the comparison and the outcome with most studies (chills/shivering) we did not detect publication bias (Figure 4).

4.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Active warming systems vs control (no active warming), outcome: 1.12 Chills/shivering.

Allocation

Twenty‐three RCTs reported the mechanism for generating the sequence of random assignment to the interventions (computer‐based in the majority of cases, but also 'drawing lots' in two studies, 'flipping a coin' in one, and rolling a modified dice in one), while the other 44 did not provide further details (there was only a mention about randomization in the title or the text of the article).

Twenty‐nine RCTs provided details on allocation concealment, the majority having used the sealed opaque envelopes system to administer the assignments (although not all of the publications specified that it was opaque sequentially‐numbered and sealed envelopes). In four trials there was no concealment at all, while the remaining 34 RCTs did not provide details on this procedure.

Blinding

Blinding could not be implemented due to the nature of the interventions, except for the four trials that used a sham intervention in the control group (Butwick 2007; Chung 2012; Kurz 1996; Wong 2007). Consequently, most of the trials had an open‐label design, although in the majority there was no mention of this domain. We assume these trials had an open‐label design, as temperature was the principal outcome and it was measured in a variety of ways that probably were not subject to bias. However, in 24 studies an evaluation was conducted by a blinded assessor of at least one outcome of interest. Again, it should be noted that the level of details provided to ensure the effectiveness of blinding is very low in most of the studies.

With regard to blinding, our 'Risk of bias' assessment depends on the nature of the outcome (although most of them were subjective outcomes) and the type of comparison we were appraising. For instance, for comparison type 1, where an ABSW system was compared with a control, we rated the lack of evidence about a blinded outcome assessment as being at high risk of bias. On the other hand, for comparison types 2 and 3 where different active interventions were being compared between them, we have rated it as being at unclear risk.

Incomplete outcome data

Given the nature of the studies conducted in surgical participants and with a very short follow‐up period (hours or at most a few days), the reported losses and dropouts were irrelevant. Although in some cases neither this information nor the basis for the analysis of the results (intention‐to‐treat versus valid cases, or the assumption for the missing values) were clearly reported, this is unlikely to be a major problem for this review.

Selective reporting

We found no evidence of selective reporting in most of the trials. It should be noted that temperature was the primary outcome in most studies, while clinical outcomes were all evaluated as secondary, and in many trials were not prespecified as outcomes.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Comparison type 1: Active warming versus control

Primary outcome 1: Surgical site infection and complications (wound healing and dehiscence)

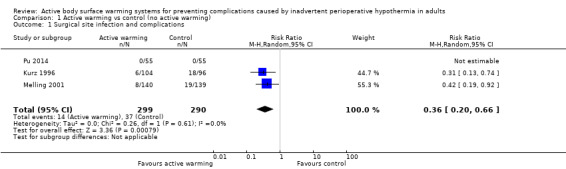

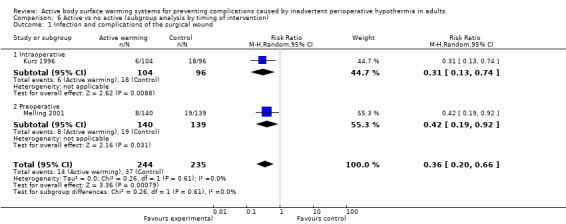

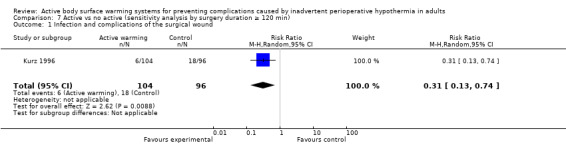

Three trials (Kurz 1996; Melling 2001; Pu 2014) including 589 participants showed a significant benefit of forced‐air warming (FAW) over control in the incidence of surgical site infection and complications (risk ratio (RR) 0.36, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.20 to 0.66; P = 0.0008; I² = 0%) (Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Active warming vs control (no active warming), Outcome 1 Surgical site infection and complications.

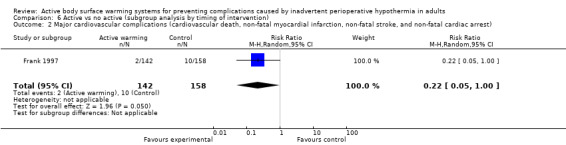

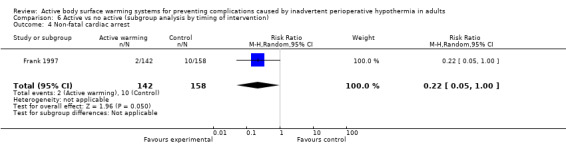

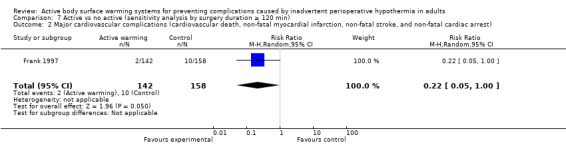

Primary outcome 2: Major cardiovascular complications (cardiovascular death, non‐fatal myocardial infarction, non‐fatal stroke and non‐fatal cardiac arrest)

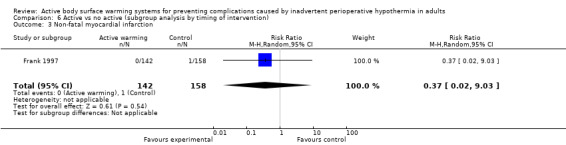

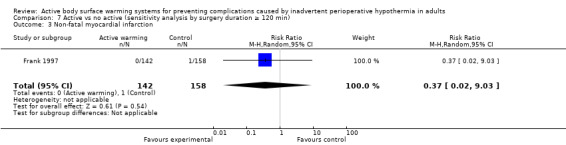

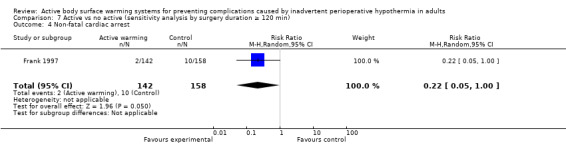

A single trial (Frank 1997) assessed major cardiovascular complications (labelled in the trial as 'morbid cardiac events') and compared FAW to control in participants with documented coronary artery disease or at high risk for coronary disease. The trial reported a statistically significant reduction in perioperative morbid cardiac events (defined as cardiac arrest, myocardial infarction, or unstable angina/ischaemia occurring in the first 24 hours postoperatively) with ABSW (reported P value < 0.02). Nevertheless, our own analysis showed a marginally non‐significant reduction in risk of major cardiovascular complications in the active warming group (12 events; RR 0.22, 95% CI 0.05 to 1.00; 1 study, 300 participants) (Table 2). There was no evidence of an effect of active warming on non‐fatal myocardial infarction (one event, RR 0.37, 95% CI 0.02 to 9.03; P = 0.54). The trial showed a marginally non‐significant reduction in risk of non‐fatal cardiac arrest in the active warming group (nine events; RR 0.22, 95% CI 0.05 to 1.00; P = 0.05).

1. Data and analyses for outcomes with only one RCT: comparison 1.

| Outcome or Subgroup | Study | Intervention | Control | Effect estimate (95% CI) | ||

| n | N | n | N | |||

| Forced‐air warming (FAW) versus control (no ABSW) | ||||||

| Morbid cardiac events (includes cardiac arrest, myocardial infarction, or unstable angina/ischaemia occurring in the first 24 hours postoperatively) | Frank 1997 | 2 | 142 | 10 | 158 | RR = 0.22 (0.05 to 1.00) |

| Electrocardiographic cardiac events (includes myocardial ischaemia or ventricular tachycardia occurring either intraoperatively or 24 hours postoperatively) | Frank 1997 | 22 | 142 | 38 | 158 | RR = 0.64 (0.40 to 1.03) |

| Postoperative morbid cardiac and electrocardiographic events | Frank 1997 | 11 | 142 | 33 | 158 | RR = 0.37 (0.19 to 0.71) |

| Pressure sores and ulcers | Scott 2001 | 9 | 161 | 17 | 163 | RR = 0.54 (0.25 to 1.17) |

RR: risk ratio; CI: confidence interval;

This trial also found that in the intra‐ and 24‐hours postoperative period, the control group had a greater incidence of electrocardiograph (ECG) events (myocardial ischaemia or ventricular tachycardia) (60 events, 300 participants; RR 0.64, 95% CI 0.40 to 1.03) (Table 2). According to the trial, the difference was statistically significant only for postoperatively ECG events, with a lower rate with FAW (32 events; reported P value < 0.02).

ABSW also reduced the combination of postoperative ECG or morbid cardiac events (44 events, 300 participants; RR 0.37, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.71; P = 0.003) (Table 2).

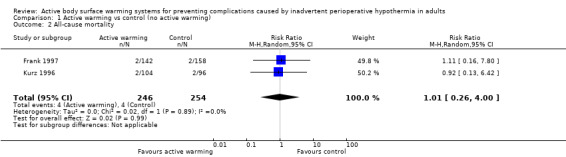

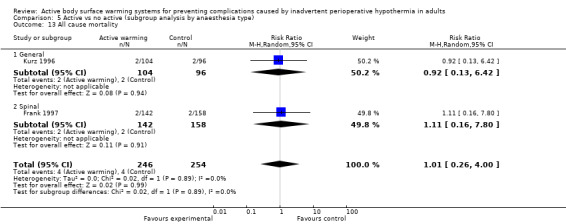

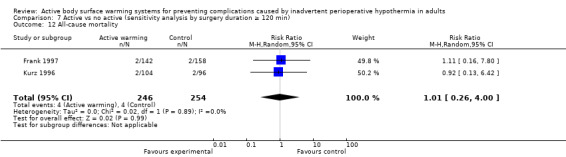

Primary outcome 3: All‐cause mortality

Two trials (Frank 1997; Kurz 1996) (500 participants) assessed this outcome and found no significant differences between FAW and control (eight events; RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.26 to 4.00; P = 0.99). In Frank 1997 the four events observed (two in each group) occurred on the fifth hospital day or beyond, and only one was reported to be related to an ischaemic cardiac event. Results were homogeneous between the trials (I² = 0%) (Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Active warming vs control (no active warming), Outcome 2 All‐cause mortality.

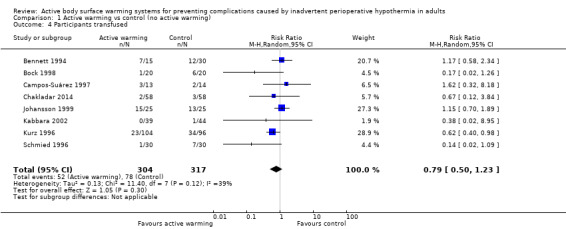

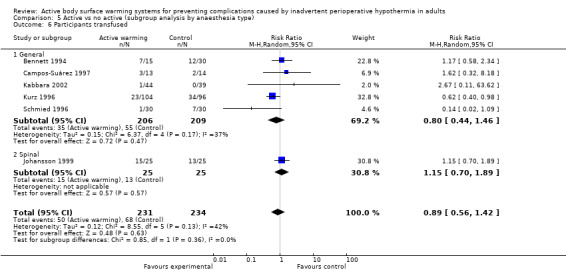

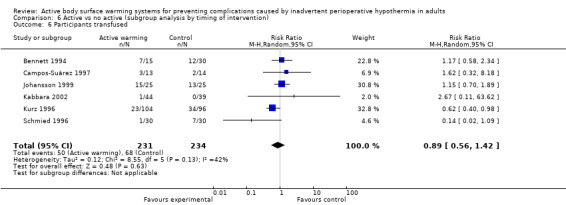

Secondary outcome 1: Transfusions (number of participants transfused; blood product usage)

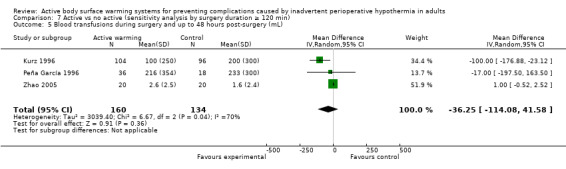

Eight trials (Bennett 1994; Frank 1997; Johansson 1999; Kurz 1996; Mogera 1997; Peña García 1996; Schmied 1996; Zhao 2005) with 779 participants assessed the amount of blood products (mainly red blood cells) transfused during surgery, showing a consistent reduction in the amount of blood transfused between FAW and control groups (mean difference (MD) ‐54.58, 95% CI ‐92.57 to ‐16.58; P = 0.005; I² = 0%) (Analysis 1.3).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Active warming vs control (no active warming), Outcome 3 Blood transfusions during surgery and up to 48 hours post‐surgery (ml).

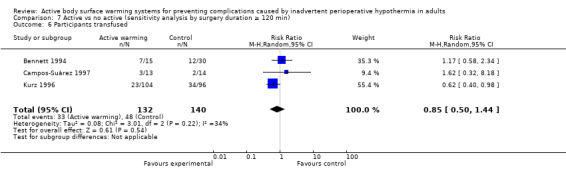

Eight trials (Bennett 1994; Bock 1998; Campos‐Suárez 1997; Chakladar 2014; Johansson 1999, Kabbara 2002; Kurz 1996; Schmied 1996) (621 participants) assessed the number of participants that received intraoperative transfusions, showing no differences between FAW and control (RR 0.79, 95% CI 0.50 to 1.23; I² = 39%) (Analysis 1.4).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Active warming vs control (no active warming), Outcome 4 Participants transfused.

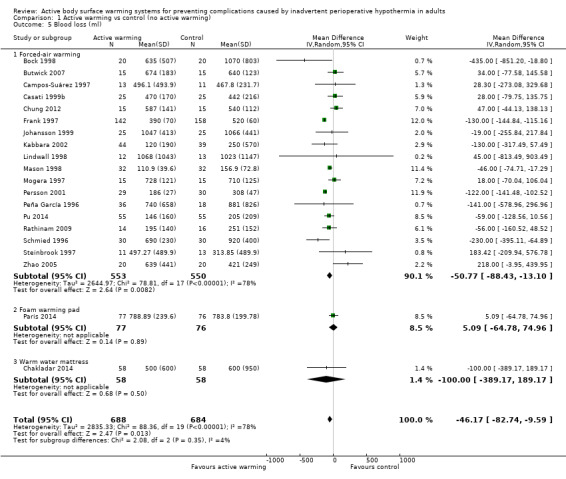

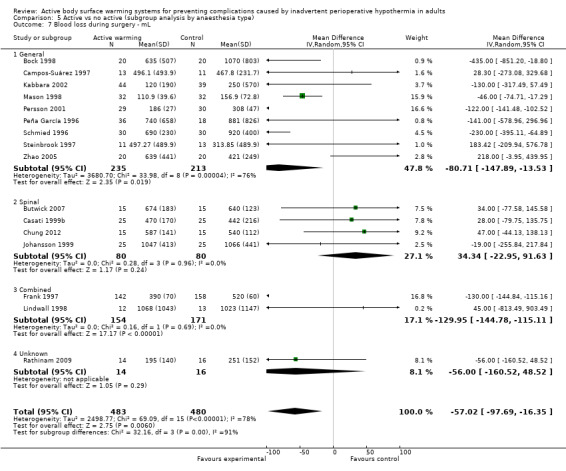

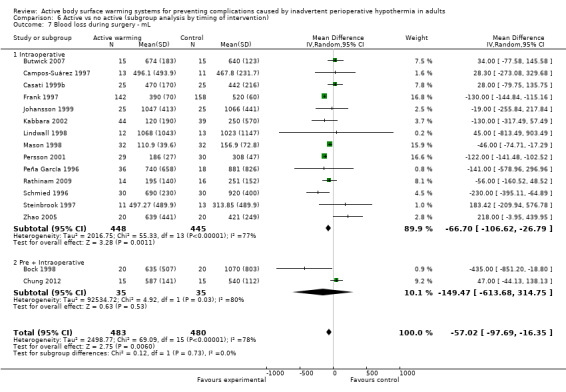

Secondary outcome 2: Blood loss (ml)

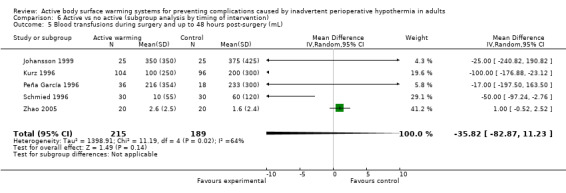

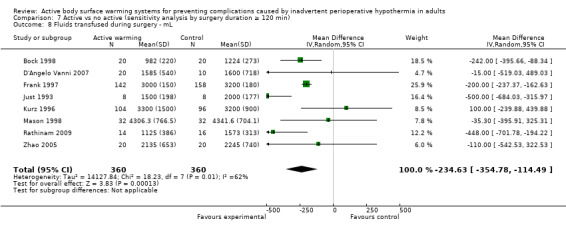

The amount of blood loss during surgery was assessed in 22 trials. Eighteen of these trials (Bock 1998; Butwick 2007; Campos‐Suárez 1997; Casati 1999b; Chung 2012; Frank 1997; Johansson 1999; Kabbara 2002; Lindwall 1998; Mason 1998; Mogera 1997; Persson 2001; Peña García 1996; Pu 2014; Rathinam 2009; Schmied 1996; Steinbrook 1997; Zhao 2005) (1103 participants) assessed the effect of FAW, showing a reduction in the blood lost in the FAW group compared to the control group, of little clinical relevance (MD ‐50.77, 95% CI ‐88.43 to ‐13.10; P = 0.008). There was high heterogeneity among studies (I² = 78%) (Analysis 1.5).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Active warming vs control (no active warming), Outcome 5 Blood loss (ml).

An additional study with FAW (Horn 2012) concluded that intraoperative blood loss was comparable between groups (no raw data provided).

Three other studies compared different ABSWs with a control: one study with 100 participants used circulating warmed‐water pads (plus warmed IV fluids) (Kiessling 2006) (results only in graph with no raw data available), one study with 153 participants used foam warming pads (Paris 2014), and one study with 116 participants used a warm‐water mattress (Chakladar 2014). None of these studies found a statistically significant difference between groups.

The pooled analysis of all 20 RCTs (1372 participants) for which raw data were available showed a reduction in blood loss in the ABSW group compared to the control group, of little clinical relevance (MD ‐46.17, 95% CI ‐82.74 to ‐9.59; P = 0.000) (Analysis 1.5).

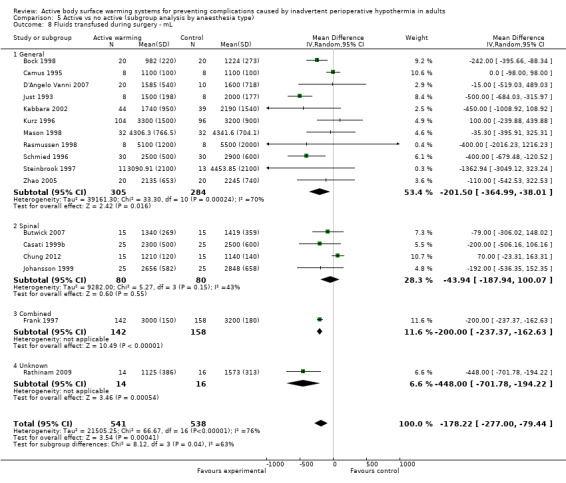

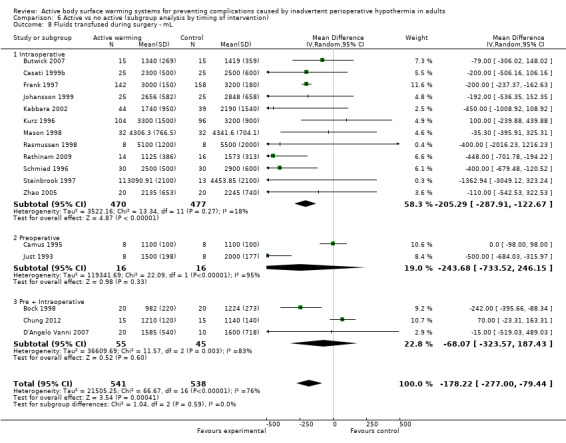

Secondary outcome 3: Intraoperative fluids infused (ml)

The amount of fluids (crystalloids or colloids or both) infused during surgery was assessed in 24 trials (Bock 1998; Butwick 2007; Campos‐Suárez 1997; Camus 1993a; Camus 1993b; Camus 1995; Casati 1999b; Chakladar 2014; Chung 2012; D'Angelo Vanni 2007; Frank 1997; Johansson 1999; Just 1993; Kabbara 2002; Kurz 1995; Kurz 1996; Mason 1998; Mogera 1997; Pu 2014; Rasmussen 1998; Rathinam 2009; Schmied 1996; Steinbrook 1997; Zhao 2005) (1491 participants), that showed a significant reduction in fluid transfusion for the intervention group compared to the control group (MD ‐144.49, 95% CI ‐221.57 to ‐67.40; P = 0.00001; I² = 73%) (Analysis 1.6).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Active warming vs control (no active warming), Outcome 6 Fluids infused (ml).

Twenty‐one of these trials assessed the effect of FAW versus control (1337 participants), showing a similar reduction in the fluids infused in the FAW group (MD ‐139.83, 95% CI ‐220.17 to ‐59.48; P value = 0.0001; I² = 65%). Two additional studies with FAW (Camus 1997; Horn 2012) concluded that intraoperative fluids administered were comparable between groups (no raw data provided).

The two studies that compared an electric blanket to a control (Camus 1993a; Just 1993) with 19 participants in each arm, showed a no reduction in the fluids infused with active warming (MD ‐243.00, 95% CI ‐772.80 to 246.80).

Secondary outcome 4: Other cardiovascular complications (bradycardia, hypotension, arrhythmias)

No studies reported this outcome.

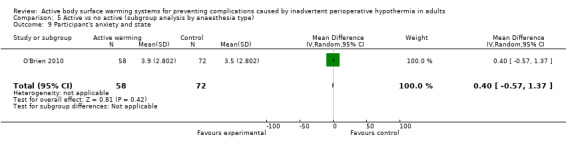

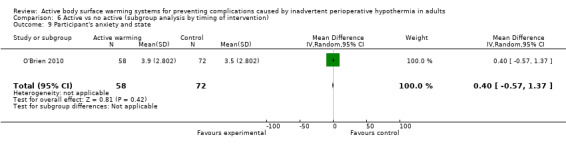

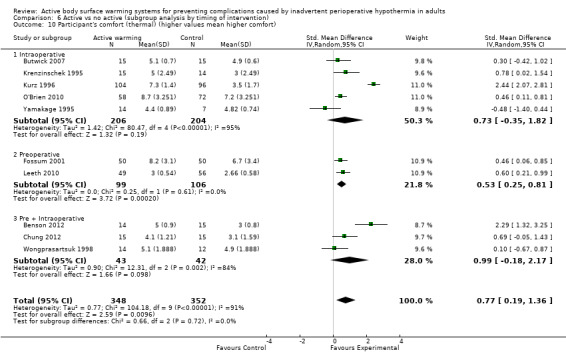

Secondary outcome 5: Participant‐reported outcomes (anxiety, thermal comfort, pain)

The degree of participant anxiety was assessed in one trial (O'Brien 2010) (130 participants) through a visual analogue scale (VAS), that did not show differences between FAW and control (MD 0.40, 95% CI ‐0.57 to 1.37; P = 0.42).

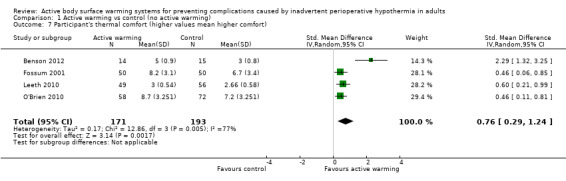

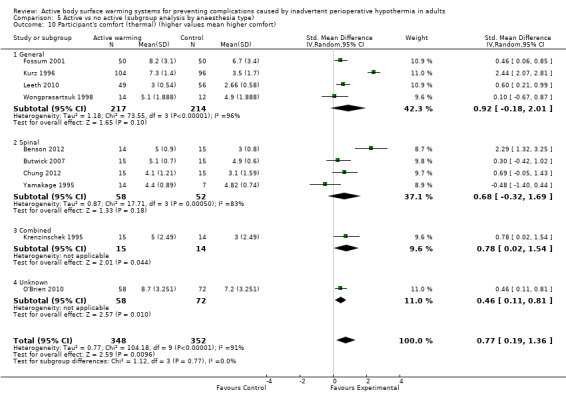

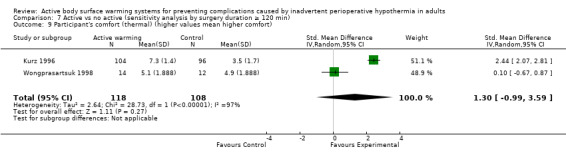

Thermal comfort was assessed in 10 trials (700 participants), all of them comparing FAW with a control. Four RCTs (364 participants) used a Likert scale where higher values meant a higher degree of satisfaction (Benson 2012; Fossum 2001; Leeth 2010; O'Brien 2010). The pooled analysis found a higher satisfaction with FAW compared with control (standardized mean difference (SMD) 0.76; 95% IC 0.29 to 1.24; P = 0.005), although there was high heterogeneity (I² = 77%) (Analysis 1.7).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Active warming vs control (no active warming), Outcome 7 Participant's thermal comfort (higher values mean higher comfort).

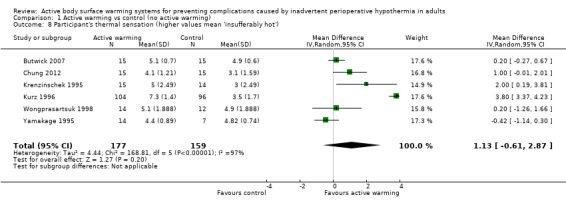

Six other studies (336 participants) used a verbal numerical scale where 0 mm was 'worst imaginable cold', 50 mm was 'thermoneutral', and 100 mm was 'insufferably hot' (Butwick 2007; Chung 2012; Krenzinschek 1995; Kurz 1996; Wongprasartsuk 1998; Yamakage 1995). The pooled analysis did not find differences in satisfaction between and control (MD 1,13 , 95% CI ‐0,61 to 2,87; P = 0.20), although there was extremely high heterogeneity (I² = 97%) (Analysis 1.8). Exclusion of the outlier trial (Kurz 1996) led to similar results, with moderate heterogeneity (MD 0,36, 95% CI ‐0,27 to 0,98; P= 0.26; I² = 56%).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Active warming vs control (no active warming), Outcome 8 Participant's thermal sensation (higher values mean 'insufferably hot').

Four additional studies (Fallis 2006; Horn 2002; Horn 2012; Kabbara 2002) reported that postoperative thermal comfort scores were no different between groups (no raw data were provided). Another study (Kurz 1995) reported that participants assigned to FAW reported significantly higher thermal comfort scores than those allocated to the control group (no raw data provided).

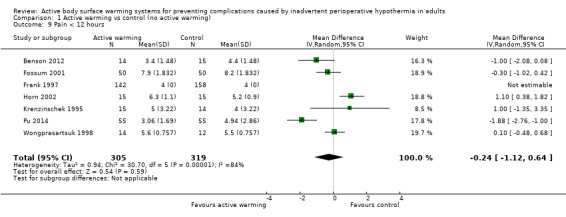

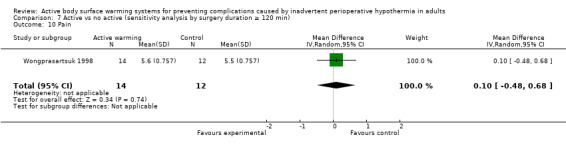

Pain was assessed in seven trials (Benson 2012; Fossum 2001; Frank 1997; Horn 2002; Krenzinschek 1995; Pu 2014; Wongprasartsuk 1998) (624 participants), all of them comparing FAW to control. There were no statistically significant differences between the two interventions (MD ‐0.24, 95% CI ‐1.12 to 0.64). The results were quite heterogeneous (I² = 84%) (Analysis 1.9). An additional trial (Fallis 2006) that assessed pain (no raw data provided) observed that there was a statistically significant up‐trend over time for pain scores in both groups, but that there was no significant difference over time between the two groups (P = 0.302). Two other studies (Kurz 1995; Kurz 1996) stated that "pain scores and the amount of opioid administered were virtually identical in the two groups at every postoperative measurement" (no raw data provided).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Active warming vs control (no active warming), Outcome 9 Pain < 12 hours.

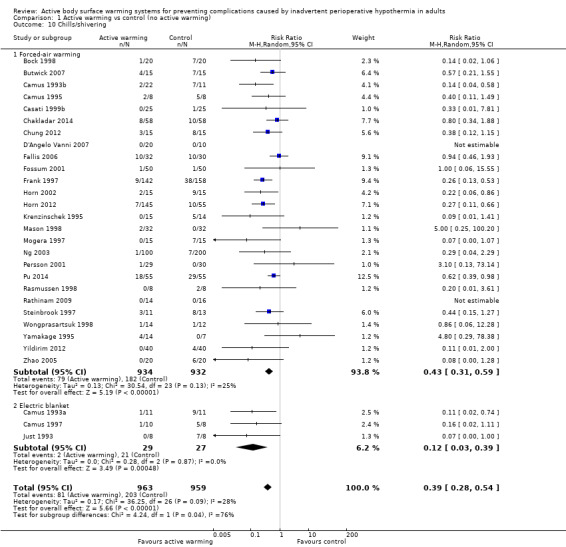

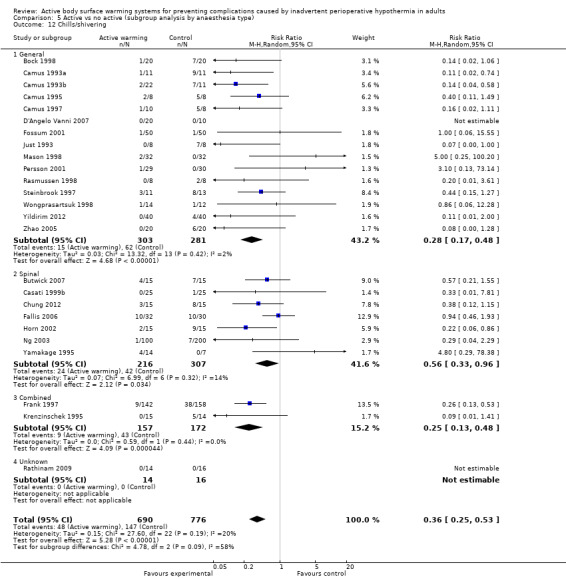

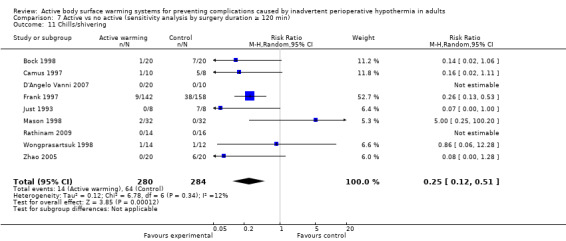

Secondary outcome 6: Shivering (number of participants)

There were 29 trials (Bock 1998; Butwick 2007; Camus 1993a; Camus 1993b; Camus 1995; Camus 1997; Casati 1999b; Chakladar 2014; Chung 2012; D'Angelo Vanni 2007; Fallis 2006; Fossum 2001; Frank 1997; Horn 2002; Horn 2012; Just 1993; Krenzinschek 1995; Mason 1998; Mogera 1997; Ng 2003; Persson 2001; Pu 2014; Rasmussen 1998; Rathinam 2009; Steinbrook 1997; Wongprasartsuk 1998; Yamakage 1995; Yildirim 2012; Zhao 2005) (1922 participants) assessing chills and shivering, that showed that participants receiving active warming systems had about one‐third the risk of chills/shivering compared to those receiving control treatment (RR 0.39, 95% CI 0.28 to 0.54; P < 0.00001; I² = 28%) (Analysis 1.10).

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Active warming vs control (no active warming), Outcome 10 Chills/shivering.

Most of the trials (26 trials, 1866 participants) used FAW as active warming, with similar results (RR 0.43, 95% CI 0.31 to 0.59; P < 0.00001; I² = 25%). An additional study (Kurz 1995) also found a favourable result with FAW (no raw data were provided).

Three trials (Camus 1993a; Camus 1997; Just 1993) (56 participants) used electric blankets, with even larger differences between groups (RR 0.12, 95% CI 0.03 to 0.39; P = 0.0005; I² = 0%).

Secondary outcome 7: Pressure sores and ulcers

Pressure ulcers were assessed in a single trial (Scott 2001) (324 participants) where the risk of pressure ulcers in the FAW group was half of that in the control group, albeit with no statistical significance (RR 0.54, 95% CI 0.25 to 1.17; P = 0.12) (Table 2).

Secondary outcome 8: Adverse effects (including thermal burns)

Three studies (Bennett 1994; Kabbara 2002; Mason 1998) stated narratively (no data presented) that there were no complications attributable to ABSW.

Other outcomes not included in the review

A variety of additional outcomes have been assessed in the studies included in the review (see table Characteristics of included studies). These include the percentage of participants who became hypothermic during the study, coagulation markers, haemoglobin level, heart rate and blood pressure, dose of analgesics, and postoperative recovery, among many others.

Comparison type 2: Active warming (1) versus active warming (2)

2.1 Forced‐air warming (FAW) versus electric heating (EHS) or resistive heating systems (RHS)

Primary outcome 1: Surgical site infection and complications (wound healing and dehiscence)

One trial with 59 participants comparing FAW versus carbon‐fibre resistive heating blankets (Hofer 2005) assessed the rate of surgical site infection (major sternal infection), and found no significant difference between FAW and EHS (two events; RR 1.03, 95% CI 0.07 to 15.77; P = 0.98) (Table 3).

2. Data and analyses for outcomes with only one RCT: comparison 2.

| Outcome or Subgroup | Study | Intervention | Control | Effect estimate (95% CI) | ||

| n or mean (SD) | N | n or mean (SD) | N | |||

| FAW/Convective air warming versus electric or resistive heating systems | ||||||

| Infection of surgical wound (major sternal infection) | Hofer 2005 | 1 | 29 | 1 | 30 | RR = 1.03 (0.07 to 15.77) |

| Blood products transfused (packed red blood cells) | Leung 2007 | 100 (276.7) | 30 | 50 (159.2) | 30 | MD = 50.00 (‐64.23 to 164.23) |

| Perioperative RBC transfusion (mL) | Hofer 2005 | 1,097 (874) | 29 | 986 (744) | 30 | MD = 111.00 (‐303.81 to 525.81) |

| Participants transfused (allogenic transfusion) | Hofer 2005 | 14 | 29 | 12 | 30 | RR = 1.29 (0.74 to 2.27) |

| Forced‐air warming (FAW) versus warm water circulation systems | ||||||

| Postoperative cardiac complications (defined as angina, myocardial infarction, cardiac arrest, unstable ventricular tachycardia, or congestive heart failure) | Elmore 1998 | 2 | 50 | 0 | 50 | RR = 5.00 (0.25 to 101.58) |

| All‐cause mortality | Elmore 1998 | 2 | 50 | 0 | 50 | RR = 5.00 (0.25 to 101.58) |

| Cardiac complications or death | Elmore 1998 | 4 | 50 | 0 | 50 | RR = 9.00 (0.50 to 162.89) |

| Thermal comfort (VAS scale) | Kim 2014 | 5 (0.5) | 23 | 4 (0.79) | 23 | MD = 1.00 (0.62 to 1.38) |

| Forced‐air warming (FAW) versus radiant heat | ||||||

| Participant's comfort (thermal sensation) | Lee 2004 | 49 (5) | 29 | 48 (14) | 30 | MD = 1.00 (‐4.33 to 6.33) |

| Resistive heating systems versus warm water circulation systems | ||||||

| Participants transfused (allogenic transfusion) | Hofer 2005 | 12 | 30 | 5 | 29 | RR = 2.32 (0.93 to 5.76) |

| Perioperative blood loss (mL) | Hofer 2005 | 2300.0 (788.0) | 30 | 1497.0 (497.0) | 29 | MD = 803.00 (467.99 to 1138.01) |

| Blood transfusions during surgery (mL) | Hofer 2005 | 1097.0 (874.0) | 30 | 431.0 (387.0) | 29 | MD = 666.00 (323 to 1001) |

| Thermal mattress vs thermal blanket (not specified) | ||||||

| Fluids infused | Moysés 2014 | 3023.7 (1160.5) | 19 | 2878.9 (1376.7) | 19 | MD = 144.80 (‐664.82 to 954.42) |

| Blood transfusions (mL) | Moysés 2014 | 589.9 (398.3) | 9 | 412.3 (157.0) | 8 | MD = 177.60 (‐104.44 to 459.64) |

RR: risk ratio; CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; RBC: red blood cell

Primary outcome 2: Major cardiovascular complications (cardiovascular death, non‐fatal myocardial infarction, non‐fatal stroke and non‐fatal cardiac arrest)

The included studies did not address these outcomes.

Primary outcome 3: All‐cause mortality

The included studies did not provide data for this outcome.

Secondary outcome 1: Transfusions (number of participants transfused; blood product usage)

One trial (60 participants) comparing FAW versus electric heating pad (Leung 2007) assessed the amount of blood products transfused intraoperatively; it showed no statistically significant difference in units of blood transfusions during surgery between participants who received FAW and those who received EHS (MD 50.00, 95% CI ‐64.23 to 164.23; P = 0.39). Similarly, one trial with 59 participants (Hofer 2005) found no statistically significant difference in the volume (ml) of blood/plasma/platelet transfusions during surgery between participants who received FAW and those who received EHS (MD 111.00, 95% CI ‐303.81 to 525.81; P = 0.60) (Table 3).

For the number of participants receiving transfusions, the same study (Hofer 2005) found no statistically significant differences between those who received FAW and those who received EHS (RR 1.29, 95% CI 0.74 to 2.27; P = 0.37) (Table 3).

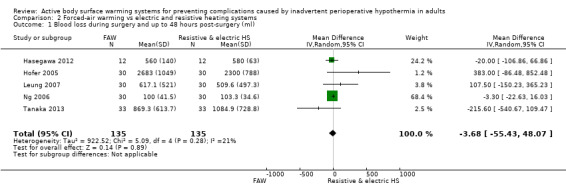

Secondary outcome 2: Blood loss (ml)

Five trials with 270 participants (Hasegawa 2012; Hofer 2005; Leung 2007; Ng 2006; Tanaka 2013) assessed the amount of blood lost during surgery, and found no statistically significant differences between FAW and electric or resistive heating systems (MD ‐3.68, 95% CI ‐55.43 to 48.07; P value = 0.28; I² = 21%) (Analysis 2.1).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Forced‐air warming vs electric and resistive heating systems, Outcome 1 Blood loss during surgery and up to 48 hours post‐surgery (ml).

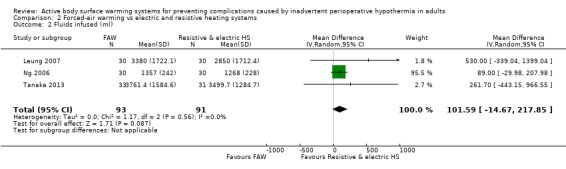

Secondary outcome 3: Intraoperative fluids infused (ml)

Three trials (184 participants) (Leung 2007; Ng 2006; Tanaka 2013) examined the amount of fluids transfused during surgery and found no statistically significant differences for participants who received FAW and those who received electric or resistive heating systems (MD 101.59, 95% CI ‐14.67 to 217.85; I² = 0%) (Analysis 2.2). An additional study (Hasegawa 2012) that reported intraoperative fluids infused as ml/kg/hr stated that this was similar between groups (no raw data).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Forced‐air warming vs electric and resistive heating systems, Outcome 2 Fluids infused (ml).

Secondary outcome 4: Other cardiovascular complications (bradycardia, hypotension, arrhythmias)

No studies reported on this outcome.

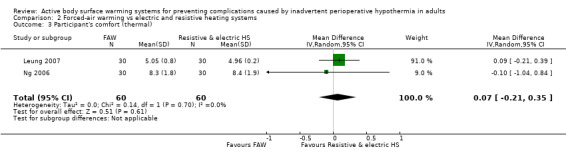

Secondary outcome 5: Participant‐reported outcomes (anxiety, thermal comfort, pain)

Thermal comfort was assessed in two studies (120 participants) (Leung 2007;Ng 2006) that showed no statistically significant difference in thermal comfort between FAW and electric or resistive heating systems (MD 0.07, 95% CI ‐0.21 to 0.35; P = 0.61; I² = 0%) (Analysis 2.3).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Forced‐air warming vs electric and resistive heating systems, Outcome 3 Participant's comfort (thermal).

No studies reported on anxiety or pain.

Secondary outcome 6: Shivering (number of participants)

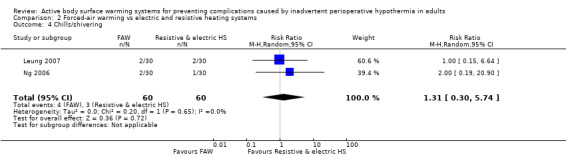

Two studies (120 participants) (Leung 2007; Ng 2006) examined the occurrence of chills/shivering. There was no statistically significant difference in this outcome measure for participants who received FAW and those who received electric or resistive heating systems (RR 1.31, 95% CI 0.30 to 5.74; I² = 0%) (Analysis 2.4).

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Forced‐air warming vs electric and resistive heating systems, Outcome 4 Chills/shivering.

Secondary outcome 7: Pressure sores and ulcers

The included studies did not provide data for this outcome.

Secondary outcome 8: Adverse effects (including thermal burns)

Only one study (Hasegawa 2012) stated that they detected no complications related to any of the warming methods.

2.2 Forced‐air warming (FAW) versus warm‐water circulation systems (WWCS)

Primary outcome 1: Surgical site infection and complications (wound healing and dehiscence)

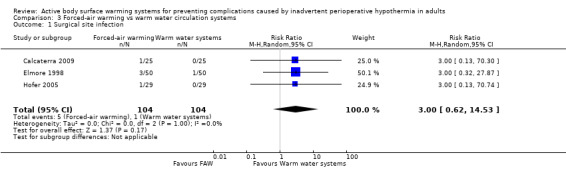

Three trials (208 participants) (Calcaterra 2009; Elmore 1998; Hofer 2005) assessed the rate of surgical site infection, and found no statistically significant difference between FAW and WWCS (RR 3.00, 95% CI 0.62 to 14.53; P = 0.17; I² = 0%) (Analysis 3.1).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Forced‐air warming vs warm water circulation systems, Outcome 1 Surgical site infection.

Primary outcome 2: Major cardiovascular complications (cardiovascular death, non‐fatal myocardial infarction, non‐fatal stroke and non‐fatal cardiac arrest)

A single study with 100 participants (Elmore 1998) assessed the occurrence of major cardiovascular complications (defined as postoperative angina, myocardial infarction, cardiac arrest, unstable ventricular tachycardia, or congestive heart failure). The event was observed in two participants who received FAW and none in those who received WWCS (RR 5.00, 95% CI 0.25 to 101.58; P = 0.29) (Table 3).

Primary outcome 3: All‐cause mortality

There was no statistically significant difference in all‐cause mortality between participants who received FAW and those who received WWCS in the one trial (100 participants) (Elmore 1998) reporting this outcome (two events; RR 5.00, 95% CI 0.25 to 101.58; P = 0.29) (Table 3).

The combination of both cardiovascular complications and death in Elmore 1998 also yielded to a statistically non‐significant result (RR 9.00, 95% CI 0.50 to 162.89; P = 0.14) (Table 3).

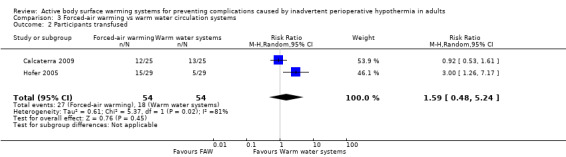

Secondary outcome 1: Transfusions (number of participants transfused; blood product usage)

Transfusions during surgery (N of participants) was assessed in two studies (108 participants) (Calcaterra 2009; Hofer 2005), and found no statistically significant differences between FAW and WWCS (RR 1.59, 95% CI 0.48 to 5.24; P = 0.45; I² = 81%), although one of the trials detected a difference in favour of WWCS (Hofer 2005).

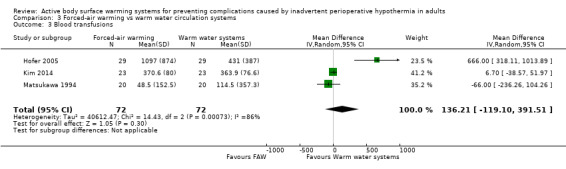

Three trials (Hofer 2005; Kim 2014; Matsukawa 1994) assessed blood transfusions during surgery (ml) in 144 participants, and found that similar volumes were transfused in the FAW and WWCS groups (MD 136.21, 95% CI ‐119.10 to 391.51; P = 0.30; I² = 86%) (Analysis 3.3).

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Forced‐air warming vs warm water circulation systems, Outcome 3 Blood transfusions.

Secondary outcome 2: Blood loss (ml)

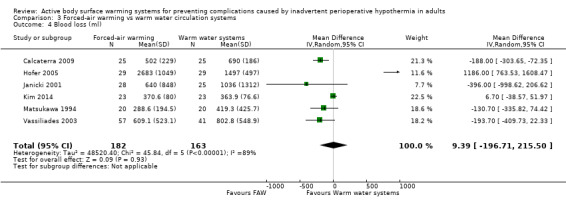

Six studies (299 participants) (Calcaterra 2009; Hofer 2005; Janicki 2001; Kim 2014; Matsukawa 1994; Vassiliades 2003) assessed blood loss during surgery, and found no statistically significant differences between FAW and WWCS (MD 38.08, 95% CI ‐298.39 to 374.54; P = 0.82). Heterogeneity was highly significant (I² = 90%) (Analysis 3.4).

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Forced‐air warming vs warm water circulation systems, Outcome 4 Blood loss (ml).

One study comparing intraoperative forced‐air warming mattress versus circulating‐water mattress (Suraseranivongse 2009) found no statistically significant differences between both groups (P value for the comparison between median values = 0.962).

Secondary outcome 3: Intraoperative fluids infused (ml)

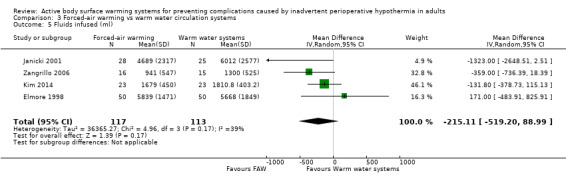

Four studies (230 participants) (Elmore 1998; Janicki 2001; Kim 2014; Zangrillo 2006) found that similar but higher volumes were transfused in the WWCS arm than in the FAW groups (MD ‐215.11, 95% CI ‐519.20 to 88.99; I² = 39%) (Analysis 3.5).

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Forced‐air warming vs warm water circulation systems, Outcome 5 Fluids infused (ml).

Secondary outcome 4: Other cardiovascular complications (bradycardia, hypotension, arrhythmias)

No studies reported on this outcome.

Secondary outcome 5: Participant‐reported outcomes (anxiety, thermal comfort, pain)

Only one study with 46 participants reported on thermal comfort (Kim 2014), and found a statistically significant improvement with FAW compared to WWCS (MD 1.00, 95% CI 0.62 to 1.38) (Table 3).

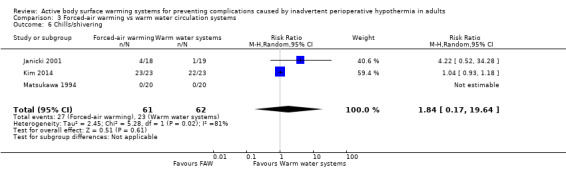

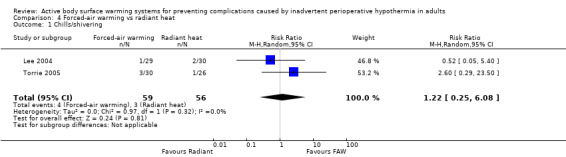

Secondary outcome 6: Shivering (number of participants)